Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

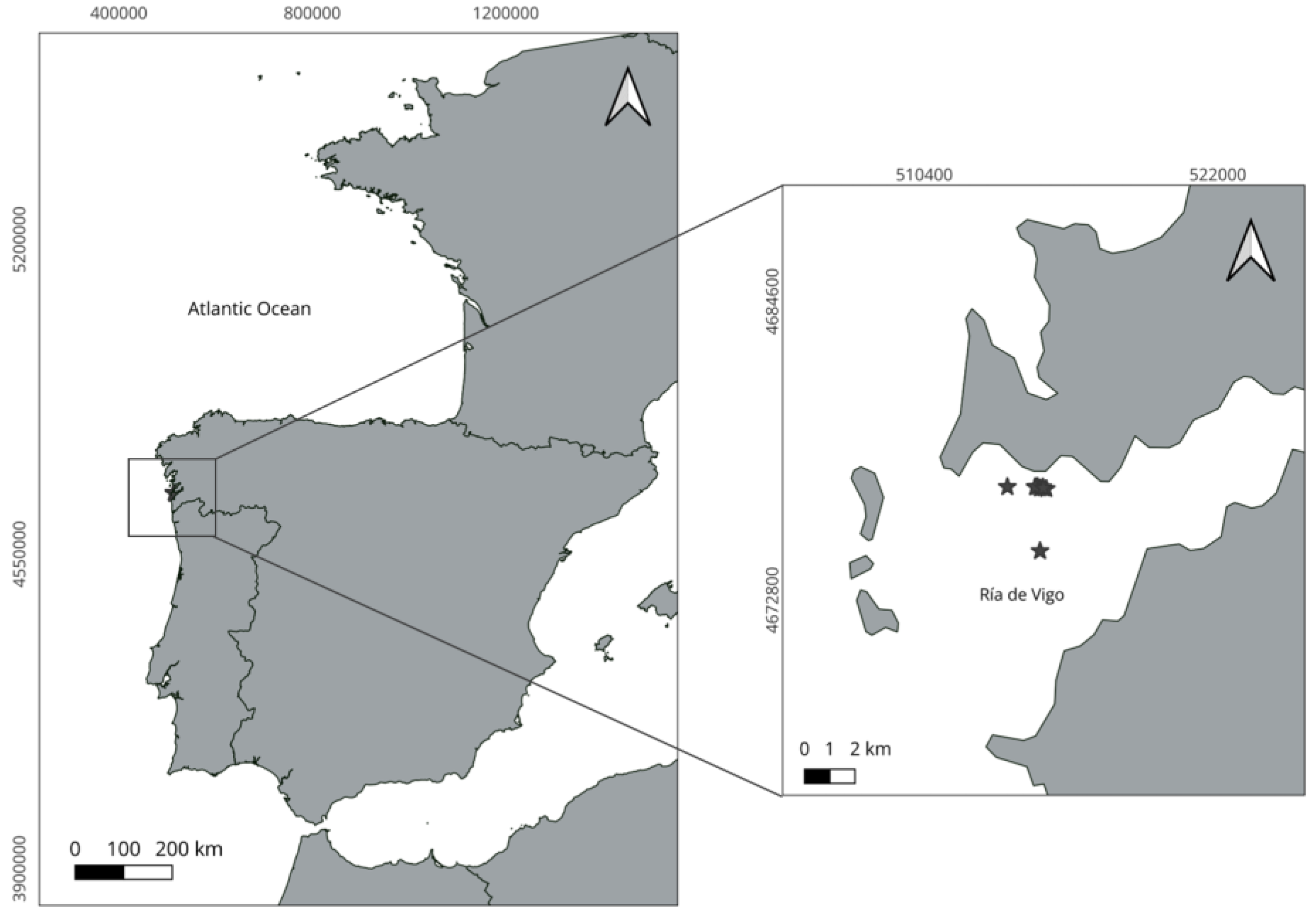

2.2. Experimental Study

2.2.1. Sampling Approach

2.2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

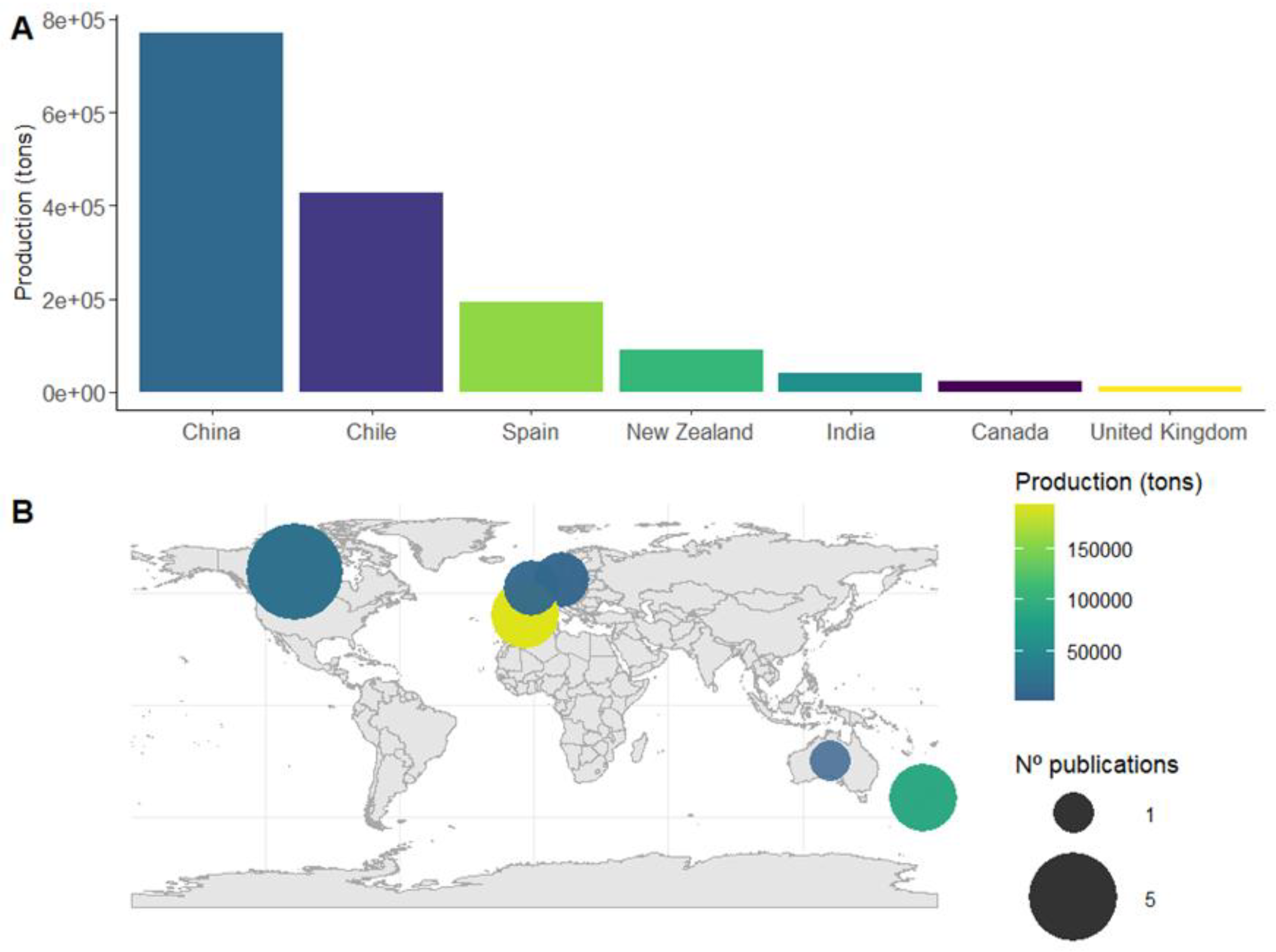

3.1. Production Rates and Scientific Effort

3.2. Ecological Benefits

3.3. Effects on Epibenthic Macroinvertebrates

| References | Ecological role/Implication | Response to mussel farm | Group/Specie |

|---|---|---|---|

| [12,37,39] | Predator of mussels; important prey of lobsters; enhances trophic links | Attraction to mussel fall-off; abundance up to 6 times within farm; diet shift toward mussel | Cancer, Pagurus, |

| C. irroratus | |||

| (rock crabs) | |||

| [40,41] | High value commercial species; uses anchor blocks and fall-off as habitat; diverse diet by higher prey availability | Mixed results: limited association in sandy offshore farms; sometimes higher abundances near structures; inter-stage competition | Homarus americanus (American lobster) |

| [26] | Key commercial species; Higher shelter fidelity and then behavioural shifts | Strong association with offshore farm structures; sheltering in anchor blocks and mussel-off | Homarus gammarus |

| (European lobster) | |||

| [13,42,43] | Keystone predator; causes economic losses in aquaculture; higher reproductive success and rapid growth | Major predator of mussels; classified as “pests” by producers | Asterias spp. |

| (sea star) | |||

| [24,44] | Predator; reproductive success boosted by mussel deposits | Abundance 25x higher within farms; enhanced growth and gonad production; interspecies competition | Coscinasterias muricata |

| (brittle star) | |||

| [16] | Detritivores; recycling organic matter | Attracted to organic deposits beneath farms | Holothuroidea (sea cucumber) |

| [16] | Grazers; influence benthic community composition | Recruitment on culture structures; individuals often fall to seabed | Echinoidea |

| (sea urchin) | |||

| [45] | Suspension feeder; increases local biodiversity | Dense beds under longlines due to pseudofaeces enrichment | Ophiocomia nigra (brittle star) |

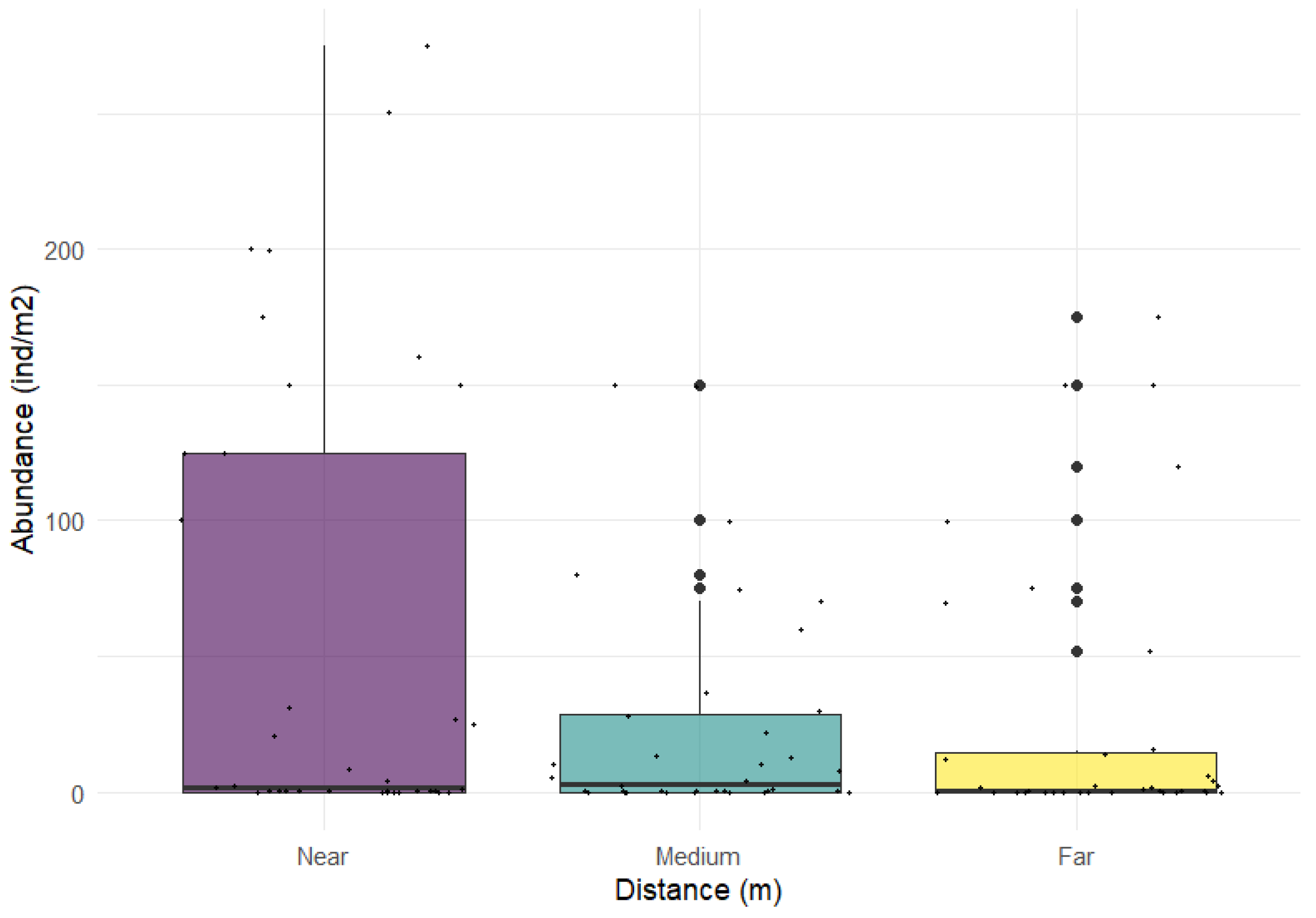

3.4. Experimental Study

4. Discussion

4.1. Balancing Ecological and Socio-Economic Benefits

4.2. Challenges and Spatial Planning Considerations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NW | Northwest |

| GLMM | Generalised Linear Mixed Model |

| EU | European Union |

References

- Rogers, A.D.; Aburto-Oropeza, O.; Appeltans, W.; Assis, J.; Ballance, L.T.; Cury, P.; Duarte, C.; Favoretto, F.; Kumagai, J.; Lovelock, C.; et al. Critical Habitats and Biodiversity: Inventory, Thresholds and Governance. In The Blue Compendium [Internet]; Lubchenco, J., Haugan, P.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 333–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, K.; Dempster, T.; Swearer, S.E.; Morris, R.L.; Barrett, L.T. Achieving conservation and restoration outcomes through ecologically beneficial aquaculture. Conserv. Biol. 2023, 38, e14065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theuerkauf, S.J.; Barrett, L.T.; Alleway, H.K.; Costa-Pierce, B.A.; Gelais, A.S.; Jones, R.C. Habitat value of bivalve shellfish and seaweed aquaculture for fish and invertebrates: Pathways, synthesis and next steps. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 14, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan R, Scholes R, Ash N, Condition M, Group T. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Current State and Trends: Findings of the Condition and Trends Working Group (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Series). 2005.

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024 [Internet]. FAO; 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 28]. Available from: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cd0683en.

- Wilding, T.A.; Nickell, T.D.; Solan, M. Changes in Benthos Associated with Mussel (Mytilus edulis L.) Farms on the West-Coast of Scotland. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e68313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C.; Archambault, P.; Olivier, F.; McKindsey, C.W. Influence of ‘bouchot’ mussel culture on the benthic environment in a dynamic intertidal system. Aquac. Environ. Interactions 2012, 2, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, J.; Fernandes, T.F.; Read, P.; Nickell, T.D.; Davies, I.M. Impacts of biodeposits from suspended mussel (Mytilus edulis L.) culture on the surrounding surficial sediments. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2001, 58, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartstein, N.D.; A Rowden, A. Effect of biodeposits from mussel culture on macroinvertebrate assemblages at sites of different hydrodynamic regime. Mar. Environ. Res. 2004, 57, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascorda-Cabre, L.; Hosegood, P.; Attrill, M.J.; Bridger, D.; Sheehan, E.V. Detecting sediment recovery below an offshore longline mussel farm: A macrobenthic Biological Trait Analysis (BTA). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 195, 115556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, A.; Archambault, P.; Clynick, B.; Richer, K.; McKindsey, C. Influence of mussel aquaculture on the distribution of vagile benthic macrofauna in îles de la Madeleine, eastern Canada. Aquac. Environ. Interactions 2015, 6, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sean, A.-S.; Drouin, A.; Archambault, P.; McKindsey, C.W. Influence of an Offshore Mussel Aquaculture Site on the Distribution of Epibenthic Macrofauna in Îles de la Madeleine, Eastern Canada. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’aMours, O.; Archambault, P.; McKindsey, C.; Johnson, L. Local enhancement of epibenthic macrofauna by aquaculture activities. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 371, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridger, D.; Attrill, M.J.; Davies, B.F.R.; Holmes, L.A.; Cartwright, A.; Rees, S.E.; Cabre, L.M.; Sheehan, E.V. The restoration potential of offshore mussel farming on degraded seabed habitat. Aquac. Fish Fish. 2022, 2, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleway, H.K.; Waters, T.J.; Brummett, R.; Cai, J.; Cao, L.; Cayten, M.R.; Costa-Pierce, B.A.; Dong, Y.; Hansen, S.C.B.; Liu, S.; et al. Global principles for restorative aquaculture to foster aquaculture practices that benefit the environment. Conserv. Sci. Pr. 2023, 5, e12982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaso Toca, I. Ecología de los equinodermos de la Ría de Arosa: N.o334. Boletín Instituto Español de Oceanografía [Internet]. 1982, 7, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiras, F.G.; Labarta, U.; Fernández Reiriz, M.J. Coastal upwelling, primary production and mussel growth in the Rías Baixas of Galicia. Hydrobiologia 2002, 484, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, ME, Kristensen, K, van Benthem, KJ, Magnusson, A, Berg, CW, Nielsen, A, et al. glmmTMB Balances Speed and Flexibility Among Packages for Zero-inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Modeling. The R Journal 2017, 9, 378–400.

- Kaspar, H.F.; Gillespie, P.A.; Boyer, I.C.; MacKenzie, A.L. Effects of mussel aquaculture on the nitrogen cycle and benthic communities in Kenepuru Sound, Marlborough Sounds, New Zealand. Mar. Biol. 1985, 85, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumway, S.; Davis, C.; Downey, R.; Karney, R.; Kraeuter, J.; Parsons, J.; et al. Guest Editorial Shellfish aquaculture — In praise of sustainable economies and environments. World Aquaculture 2012, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, J.M.; Bricker, S.B.; Tedesco, M.A.; Wikfors, G.H. A Role for Shellfish Aquaculture in Coastal Nitrogen Management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2519–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.J.; Scrimgeour, G.J.; Richards, L.A.; Locky, D. Multi-Spatial and Temporal Assessments of Impacts and Recovery of Epibenthic Species and Habitats Under Mussel Farms in the Marlborough Sounds, New Zealand. J. Shellfish. Res. 2024, 43, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, G.J.; Gust, N. Potential indirect effects of shellfish culture on the reproductive success of benthic predators. J. Appl. Ecol. 2003, 40, 1077–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabre, L.M.; Hosegood, P.; Attrill, M.J.; Bridger, D.; Sheehan, E.V. Offshore longline mussel farms: a review of oceanographic and ecological interactions to inform future research needs, policy and management. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 1864–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamp, T.; Pittman, S.J.; Holmes, L.A.; Rees, A.; Ciotti, B.J.; Thatcher, H.; Davies, P.; Hall, A.; Wells, G.; Olczak, A.; et al. Restorative function of offshore longline mussel farms with ecological benefits for commercial crustacean species. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 951, 174987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKindsey CW, Anderson MR, Courtenay S, Landry T, Skinner M. Effets off Shellfish Aquaculture on Fish Habitat. 2006.

- Powers, M.J.; Peterson, C.H.; Summerson, H.C.; Powers, S.P. Macroalgal growth on bivalve aquaculture netting enhances nursery habitat for mobile invertebrates and juvenile fishes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007, 339, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Pierce, B.A.; Bridger, C.J. The role of marine aquaculture facilities as habitats and ecosystems. Responsible Marine Aquaculture. 2002, 105–144. [Google Scholar]

- Marine Conservation Society. Good Fish Guide: Best Choice seafood [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.mcsuk.org/news/why-you-should-be-eating-more-uk-shellfish.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020: Sustainability in action. 2020.

- Callier, M.D.; McKindsey, C.W.; Desrosiers, G. Evaluation of indicators used to detect mussel farm influence on the benthos: Two case studies in the Magdalen Islands, Eastern Canada. Aquaculture 2008, 278, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clynick, B.; McKindsey, C.; Archambault, P. Distribution and productivity of fish and macroinvertebrates in mussel aquaculture sites in the Magdalen islands (Québec, Canada). Aquaculture 2008, 283, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; González-Gurriarán, E.; Penas, E. Influence of mussel rafts on spatial and seasonal abundance of crabs in the R a de Arousa, North-West Spain. Mar. Biol. 1982, 72, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond-Davis, N.C.; Mann, K.H.; Pottle, R.A. Some Estimates of Population Density and Feeding Habits of the Rock Crab, Cancer irroratus, in a Kelp Bed in Nova Scotia. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1982, 39, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolmer, P. The interactions between bed structure of Mytilus edulis L. and the predator Asterias rubens L. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1998, 228, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, K.; Lavoie, M.; Macgregor, K.; Simard, É.; Drouin, A.; Comeau, L.; McKindsey, C. Movement of American lobsters Homarus americanus and rock crabs Cancer irroratus around mussel farms in Malpeque Bay, Prince Edward Island, Canada. Aquac. Environ. Interactions 2023, 15, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.C.; Barbeau, M.A. Prey selection and the functional response of sea stars (Asterias vulgaris Verrill) and rock crabs (Cancer irroratus Say) preying on juvenile sea scallops (Placopecten magellanicus (Gmelin)) and blue mussels (Mytilus edulis Linnaeus). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2005, 327, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, J.; González-Gurriarán, E. Feeding ecology of the velvet swimming crab Necora puber in mussel raft areas of the Ría de Arousa (Galicia, NW Spain). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1995, 119, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, M.; Simard, É.; Drouin, A.; Archambault, P.; Comeau, L.; McKindsey, C. Movement of american lobster Homarus americanus associated with offshore mussel Mytilus edulis aquaculture. Aquac. Environ. Interactions 2022, 14, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardenne, F.; Forget, N.; McKindsey, C.W. Contribution of mussel fall-off from aquaculture to wild lobster Homarus americanus diets. Mar. Environ. Res. 2019, 149, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agüera, A.; Saurel, C.; Møller, L.F.; Fitridge, I.; Petersen, J.K. Bioenergetics of the common seastar Asterias rubens: a keystone predator and pest for European bivalve culture. Mar. Biol. 2021, 168, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaymer, C.F.; Himmelman, J.H.; E Johnson, L. Use of prey resources by the seastars Leptasterias polaris and Asterias vulgaris: a comparison between field observations and laboratory experiments. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2001, 262, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L.T.; Swearer, S.E.; Dempster, T. Native predator limits the capacity of an invasive seastar to exploit a food-rich habitat. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 162, 105152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaso Toca, I. Biología de los equinodermos de la ría de Arosa: N.o 270. Boletín Instituto Español de Oceanografía [Internet]. 1979, 5, 81–128. [Google Scholar]

- Agüera, A. The role of sea stars (Asterias rubens L.) predation in blue mussel (Mytilus edulis L.) seedbed stability. 2015.

- Pryor, M.L. Temporal and spatial distribution of larval and post-larval blue mussels (Mytilus edulis/Mytilus trossulus) and sea stars (Asterias vulgaris) within four Newfoundland mussel culture sites [Internet]. Memorial University of Newfoundland; 2004 [cited 2025 Aug 21]. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.

- Barrett, L.T.; Swearer, S.E.; Dempster, T. Impacts of marine and freshwater aquaculture on wildlife: a global meta-analysis. Rev. Aquac. 2018, 11, 1022–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivalve aquaculture and exotic species: A review of ecological considerations and management issues [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232686987_Bivalve_aquaculture_and_exotic_species_A_review_of_ecological_considerations_and_management_issues.

- Zanotto, F.; Wheatly, M. Calcium balance in crustaceans: nutritional aspects of physiological regulation. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2002, 133, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PDF) Niche segregation between American lobster Homarus amencanus and rock crab Cancer irroratus [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250214574_Niche_segregation_between_American_lobster_Homarus_amencanus_and_rock_crab_Cancer_irroratus. 250.

- Gendron, L.; Fradette, P.; Godbout, G. The importance of rock crab (Cancer irroratus) for growth, condition and ovary development of adult American lobster (Homarus americanus). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2001, 262, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahle, R.A.; Steneck, R.S. Habitat restrictions in early benthic life: experiments on habitat selection and in situ predation with the American lobster. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1992, 157, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, J.S. The Shelter-Related Behavior of the Losbter, Homarus Americanus. Ecology 1971, 52, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnofsky, E.B.; Atema, J.; Elgin, R.H. Field Observations of Social Behavior, Shelter Use, and Foraging in the Lobster, Homarus americanus. Biol. Bull. 1989, 176, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacoste, É.; Drouin, A.; Weise, A.; Archambault, P.; McKindsey, C. Low benthic impact of an offshore mussel farm in Îles-de-la-Madeleine, eastern Canada. Aquac. Environ. Interactions 2018, 10, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKindsey, C.W.; Archambault, P.; Callier, M.D.; Olivier, F. Influence of suspended and off-bottom mussel culture on the sea bottom and benthic habitats: a review. Can. J. Zoöl. 2011, 89, 622–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission. Quality Status Report (QRS) 2010 [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://oap.ospar.org/en/ospar-assessments/quality-status-reports/qsr-2023/other-assessments/aquaculture/.

- Sala, E.; Lubchenco, J.; Grorud-Colvert, K.; Novelli, C.; Roberts, C.; Sumaila, U.R. Assessing real progress towards effective ocean protection. Mar. Policy 2018, 91, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupan, M.; Fragkopoulou, E.; Claudet, J.; Erzini, K.; e Costa, B.H.; Gonçalves, E.J. Marine partially protected areas: drivers of ecological effectiveness. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2018, 16, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- e Costa, B.H.; Claudet, J.; Franco, G.; Erzini, K.; Caro, A.; Gonçalves, E.J. A regulation-based classification system for marine protected areas: A response to Dudley et al. [9]. Mar. Policy 2017, 77, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Jover, D.; Sanchez-Jerez, P.; Bayle-Sempere, J.T.; Valle, C.; Dempster, T. Seasonal patterns and diets of wild fish assemblages associated with Mediterranean coastal fish farms. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2008, 65, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, T.; Uglem, I.; Sanchez-Jerez, P.; Fernandez-Jover, D.; Bayle-Sempere, J.; Nilsen, R.; Bjørn, P. Coastal salmon farms attract large and persistent aggregations of wild fish: an ecosystem effect. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009, 385, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzman, J. Applying the ecosystem services concept to aquaculture: A review of approaches, definitions, and uses. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 35, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, M.-F.; Lacoste, É.; Weise, A.M.; McKindsey, C.W. Benthic responses to organic enrichment under a mussel (Mytilus edulis) farm. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1433365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ysebaert, T.; Hart, M.; Herman, P.M.J. Impacts of bottom and suspended cultures of mussels Mytilus spp. on the surrounding sedimentary environment and macrobenthic biodiversity. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2008, 63, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuta, D.D.; Froehlich, H.E.; Wilson, J.R. The changing role and definitions of aquaculture for environmental purposes. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 15, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burg, S.v.D.; Termeer, E.; Skirtun, M.; Poelman, M.; Veraart, J.; Selnes, T. Exploring mechanisms to pay for ecosystem services provided by mussels, oysters and seaweeds. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willot, P.-A.; Aubin, J.; Salles, J.-M.; Wilfart, A. Ecosystem service framework and typology for an ecosystem approach to aquaculture. Aquaculture 2019, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivier, B.; Dauvin, J.-C.; Navon, M.; Rusig, A.-M.; Mussio, I.; Orvain, F.; Boutouil, M.; Claquin, P. Marine artificial reefs, a meta-analysis of their design, objectives and effectiveness. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkol-Finkel, S.; Hadary, T.; Rella, A.; Shirazi, R.; Sella, I. Seascape architecture – incorporating ecological considerations in design of coastal and marine infrastructure. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 120, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhamer, O. Artificial Reef Effect in relation to Offshore Renewable Energy Conversion: State of the Art. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wu, J. The Role of Shellfish Aquaculture in Coastal Habitat Restoration. Int. J. Mar. Sci. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifico, A.M.; Brigolin, D.; Mulazzani, L.; Semeraro, M.; Malorgio, G. Managing marine aquaculture by assessing its contribution to ecosystem services provision: The case of Mediterranean mussel, Mytilus galloprovincialis. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimpel, A.; Stelzenmüller, V.; Töpsch, S.; Galparsoro, I.; Gubbins, M.; Miller, D.; Murillas, A.; Murray, A.G.; Pınarbaşı, K.; Roca, G.; et al. A GIS-based tool for an integrated assessment of spatial planning trade-offs with aquaculture. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 627, 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thatcher, H.; Stamp, T.; Wilcockson, D.; Moore, P.J.; Birchenough, S.; Lopez, L.L. Residency and habitat use of European lobster (Homarus gammarus) within an offshore wind farm. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2023, 80, 1410–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Land Use Coalition. Growing Better: Ten Critical Transitions to Transform Food and Land Use. 2019.

- Soto D, Aguilar-Manjarrez J, Hishamunda N. Building an ecosystem approach to aquaculture: FAO/Universitat de les Illes Balears expert workshop, 7-11 may 2007, Palma de Mallorca, Spain. Rome: FAO; 2008.

- Brugère, C.; Aguilar-Manjarrez, J.; Beveridge, M.C.M.; Soto, D. The ecosystem approach to aquaculture 10 years on – a critical review and consideration of its future role in blue growth. Rev. Aquac. 2018, 11, 493–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L, B. First Evidence of Spatial Relationships between Ecosystem Functioning and Services in the marine environment. J. Ecol. Nat. Resour. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| P value | Z value | Std. Error | Estimate | Fixed effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.436 | 0.779 | 1.633 | 1.272 | Near |

| 0.099 | -1.648 | 0.476 | -0.784 | Middle |

| 0.375 | -0.888 | 0.618 | -0.549 | Far |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).