1. Introduction

The Black Sea is recognized as the world's largest semi-enclosed inland sea due to its limited water exchange with other marine systems. This unique hydrographic configuration directly shapes its physical, chemical, and biological characteristics. Surface waters are dominated by freshwater inputs from rivers, leading to a significant decrease in salinity down to approximately 17‰. With increasing depth, more saline Mediterranean origin waters occupy the lower layers, resulting in the formation of a pronounced halocline [

1,

2].

This density stratification severely restricts vertical mixing between surface and bottom waters, rendering layers below 150–200 meters anoxic. Beneath this anoxic zone, hydrogen sulfide (H

₂S) accumulates, making the Black Sea one of the few marine systems in the world where deep-water layers do not support aerobic life [

3].

Such stratification directly influences phytoplankton productivity, zooplankton composition, and benthic life. Moreover, the influx of high nutrient loads particularly nitrogen and phosphorus through river discharge contributes to eutrophication, triggering algal blooms, oxygen depletion, and overall degradation of ecosystem health [

4]. These dynamics significantly shape the distribution and diversity of macrozoobenthic communities in the region.

With its rich biological diversity and ecological heterogeneity, the Black Sea holds both regional and global importance. Its benthic ecosystems play a critical role in maintaining ecological balance and sustaining biological productivity through diverse habitats and species richness [

5]. In both the mediolittoral and infralittoral zones of the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara,

Mytilus galloprovincialis forms dense beds on hard substrates [

3,

6,

7].

In the Black Sea,

M. galloprovincialis beds are predominantly found in shallow waters but can extend to depths of 30–50 meters, and occasionally even reach 80 meters in some areas [

8,

9]. These mussels are capable of colonizing a wide range of habitats, including coastal hardgrounds, rocky areas, artificial structures, and deep-sea muds. As filter feeders,

M. galloprovincialis consume phytoplankton, organic detritus, bacteria, and dissolved organic matter from the water column [

10,

11].

The productivity of natural

M. galloprovincialis populations can be limited by physiological stress, food scarcity, predation, and population density [

12,

13]. Macro-benthic organisms associated with mussel beds are generally categorized into ecological groups such as epibenthic fauna, epiphytic fauna, infauna, and free-living fauna [

14,

15]. The composition of these groups is influenced by environmental conditions and the accumulation of particulate organic matter within the mussel beds [

16].

In recent years, numerous scientific studies have focused on monitoring and conserving benthic invertebrates in the Black Sea. These efforts provide critical insights into ecosystem health and biodiversity conservation. Benthic invertebrates in the Black Sea are indispensable components in sustaining ecosystem balance and water quality; their protection is vital for ensuring the long-term ecological sustainability of the region [

17].

The Black Sea's water temperature, ranging from 7 to 25°C, and salinity levels between 17–20 ppt offer favorable conditions for mussel aquaculture [

18,

19]. Mussel farms in the region are predominantly designed as surface longline systems, driven by the expectation that high phytoplankton concentrations in surface waters would promote mussel growth.

Studies on macro-benthic invertebrates associated with

M. galloprovincialis have revealed amphipods as one of the dominant groups in these habitats [

20,

21]

. Amphipods utilize mussel beds for both shelter and feeding, thriving in these habitats that are rich in detritus and microorganisms. Species from the families Gammaridae and Caprellidae significantly contribute to the ecological richness of mussel beds. These symbiotic interactions enhance the biodiversity and structural complexity of mussel facies, thereby supporting ecosystem sustainability.

This study aims to investigate the biodiversity of macro-benthic invertebrates associated with M. galloprovincialis cultivated in offshore floating longline systems in the Black Sea and to examine their ecological functions in relation to water quality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Longline System

The “Mussel Aquaculture Research Facility” is located within the 1st Designated Aquaculture Zone between Demirciköy and Gerze, in the province of Sinop, Türkiye, and consists of a surface longline system (

Figure 1). The closest point of the project site to the shoreline is approximately 4,490 meters, with depths ranging between 35 and 42 meters.

The study was conducted between September 2023 and August 2024 in the offshore waters of Sinop in the Black Sea, at depths ranging from 25 to 27 meters (

Figure 1). This marine site was selected due to its relatively lower exposure to harsh weather conditions such as strong winds, currents, and high waves. The system was designed in accordance with local environmental conditions and consists of 12 submerged longline units, each 8 meters in length (

Figure 2).

2.2. Environmental Parameters

Water temperature and salinity were measured monthly between September 2023 and August 2024 using a YSI 6600 multi-parameter probe (

Figure 3). Measurements were taken in situ by immersing the probe directly from the sampling vessel, and the data were recorded immediately. All water parameter values obtained throughout the one-year sampling period were compiled in an Excel spreadsheet and prepared for subsequent analyses.

2.3. Mussel Sample Collection

In the longline system, rope seach 8 meters in length were suspended in the water column using buoys and weights. Samples were collected from 30 cm segments of each of the 12 ropes, which were identical in length, thickness, and material (

Figure 2). To increase taxonomic resolution and ensure statistical robustness for quantitative analysis, sampling was conducted monthly using three replicates per rope. After collection, materials were emptied into a container on board and transferred into 500–1000 ml plastic jars using a small scoop. Samples were fixed in 96% ethanol for preservation. The total number of individuals obtained from the replicates was averaged by dividing the sum by three to determine the mean individual abundance per sampling unit.

After being transported to the laboratory, mussel samples were washed using a dual-layer sieve system with mesh sizes of 2 mm and 0.5 mm. Organisms retained on the 0.5 mm sieve were included in the study, while smaller fractions were excluded. The retained samples were then sorted into taxonomic groups under a stereomicroscope with appropriate lighting, labeled accordingly, and preserved in 75% ethanol for species identification. Each specimen was identified to the lowest possible taxonomic level. Species lists and biodiversity index results were reported according to sampling stations.

For the identification of marine macrobenthic invertebrates, standard morphological keys and regional faunal references were utilized. For members of the class Polychaeta, identification followed [

22] and [

23]. For mollusks, the keys of [

24,

25] were used. For crustaceans, particularly Amphipoda and Decapoda, identification was based on the taxonomic works of [

26] and [

27]. Additionally, species confirmations and up-to-date taxonomic information were verified through digital databases such as the World Register of Marine Species [

28] and the Ocean Biodiversity Information System [

29].

2.4. Data Analysis

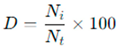

The dominance index for each identified taxon was calculated according to [

27] using the following formula:

Here,

D = Dominance percentage of species i,

Ni = Number of individuals belonging to species i,

Nt = otal number of macrobenthic invertebrate individuals

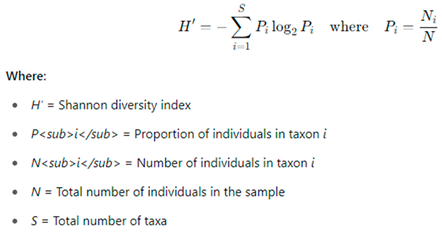

To characterize the monthly macroinvertebrate communities, diversity and evenness metrics were applied. These included the Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index (H') [

30], Pielou’s Evenness Index (J') [

31], and Simpson’s Diversity Index (1–D).

Shannon’s diversity index was calculated using the formula proposed by [

30]:

This index ranges from 0 to 5, although it rarely exceeds 1; values closer to 5 indicate higher taxonomic diversity.

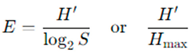

Pielou’s evenness index was calculated using the formula:

Here,

S =represents the number of taxa in the sample, while

H= refers to the Shannon diversity index value [

30]. This index ranges from 0 to 1, with values approaching 1 indicating that taxa are distributed relatively evenly throughout the community.

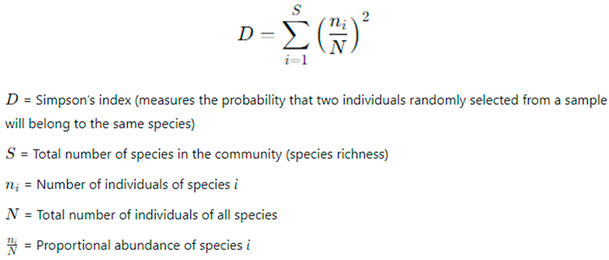

The most commonly used formula for Simpson’s Diversity Index is as follows:

According to the Simpson Index, values range between 0 and 1: 0 indicates no diversity (i.e., all individuals belong to a single species), while 1 represents maximum diversity (i.e., all species have an equal number of individuals).

Additionally, to examine the relationships between environmental parameters and species distribution, Redundancy Analysis (RDA) was employed.

Redundancy Analysis (RDA) was performed using the vegan package [

32] in R version 4.2.2 [

33].

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Parameters and Seasonal Variations

An overview of the water parameters measured over the course of one year is presented in

Figure 3:

Water Temperature (T): Water temperature exhibited a typical seasonal cycle, reaching its lowest value in winter (9.88°C in January) and peaking in summer (22.88°C in August). The lowest temperatures were observed in January–February, followed by a gradual increase beginning in May.

Salinity (S): Salinity fluctuated within a relatively narrow range throughout the year, reaching a minimum in autumn and a maximum at the end of summer. These fluctuations are likely influenced by environmental factors such as freshwater inputs and evaporation rates.

pH: The pH values remained within a slightly alkaline range (8.00–8.87). Increases during winter may be associated with lower temperatures and higher oxygen levels, while decreases observed in summer could be attributed to intensified biological activity and the decomposition of organic matter.

Dissolved Oxygen (DO): Dissolved oxygen levels peaked at 10.35 mg/L in February and declined to a minimum of 5.30 mg/L in July. This pattern corresponds with reduced oxygen solubility at higher temperatures and increased biological oxygen demand during the warmer months.

3.2. Macroinvertebrate Community

During the 12-month sampling period conducted along the mussel longline system in the Black Sea, a total of 99,719 individuals representing 20 macroinvertebrate taxa were recorded (

Table 1). The identified taxa encompassed a wide range of invertebrate groups, including Crustacea, Mollusca, Polychaeta, Cirripedia, Platyhelminthes, Cnidaria, and Nematoda, reflecting the ecological diversity and complexity of the benthic community associated with mussel aquaculture.

Monthly species distribution showed marked temporal variation, primarily driven by the overwhelming dominance of

Jassa marmorata, which accounted for approximately 71.36% of all individuals. This was followed by

Stenothoe monoculoides (27.80%) and

Nereis zonata (0.37%) (

Table 1). These dominant taxa are considered to play key roles in the trophic structure and habitat dynamics of mussel associated benthic environments.

According to the analysis of species abundance, the highest number of individuals was recorded in October, while the lowest was observed in July (

Figure 4).

Seasonal analysis of species abundance revealed that the highest number of individuals occurred during autumn, while the lowest was observed in summer. In contrast, species richness peaked in the summer season, during which a total of 15 taxa were identified (

Figure 4).

The RDA biplot illustrated the relationships between species and environmental variables (pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature, and salinity

Figure 5).

These findings are of considerable importance for understanding the influence of environmental variables on species distribution and habitat preferences.

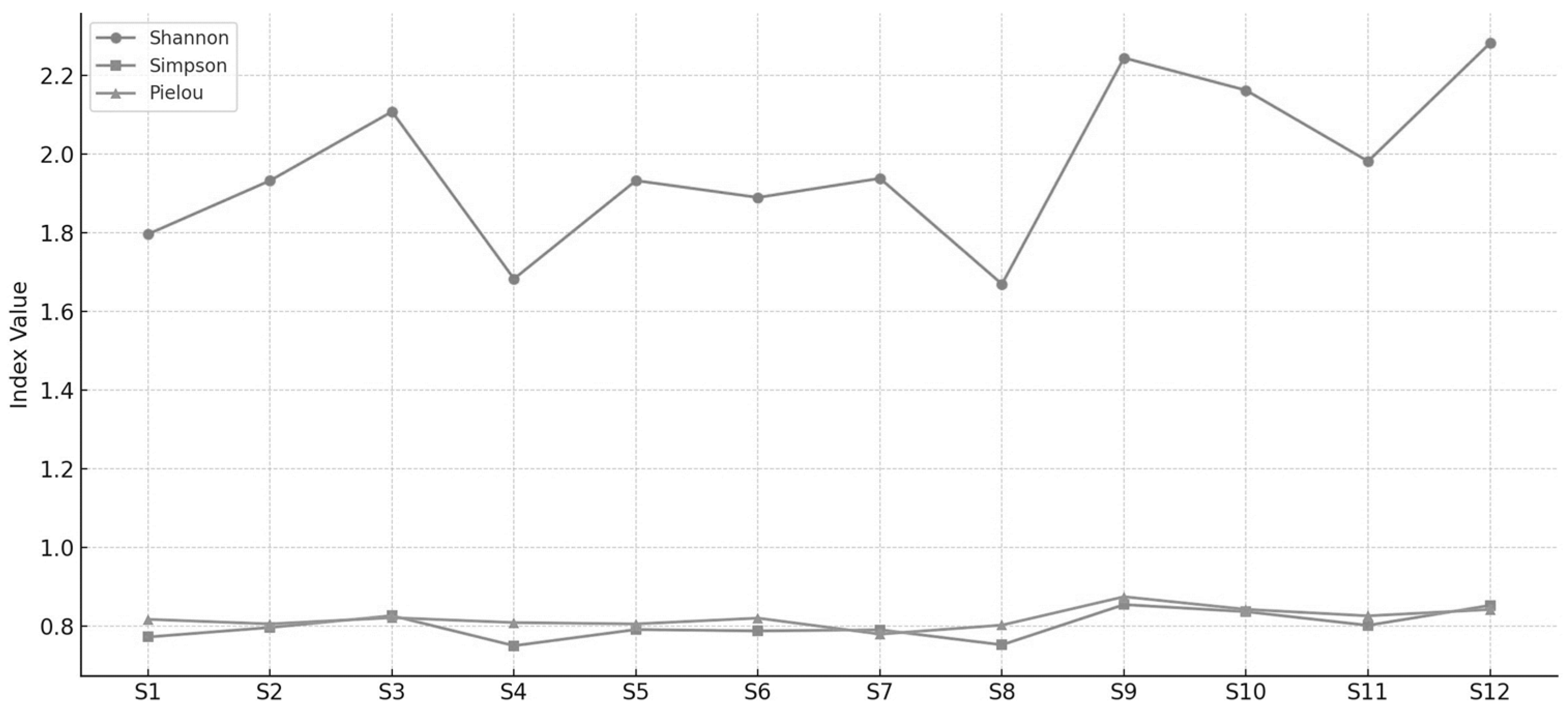

To evaluate the ecological diversity of the macrozoobenthic community structure, the Shannon–Wiener (H′), Simpson (1–D), and Pielou (J′) indices were calculated. The index values varied across the 12-month study period, revealing significant spatial variations in terms of both diversity and distribution patterns (

Figure 6).

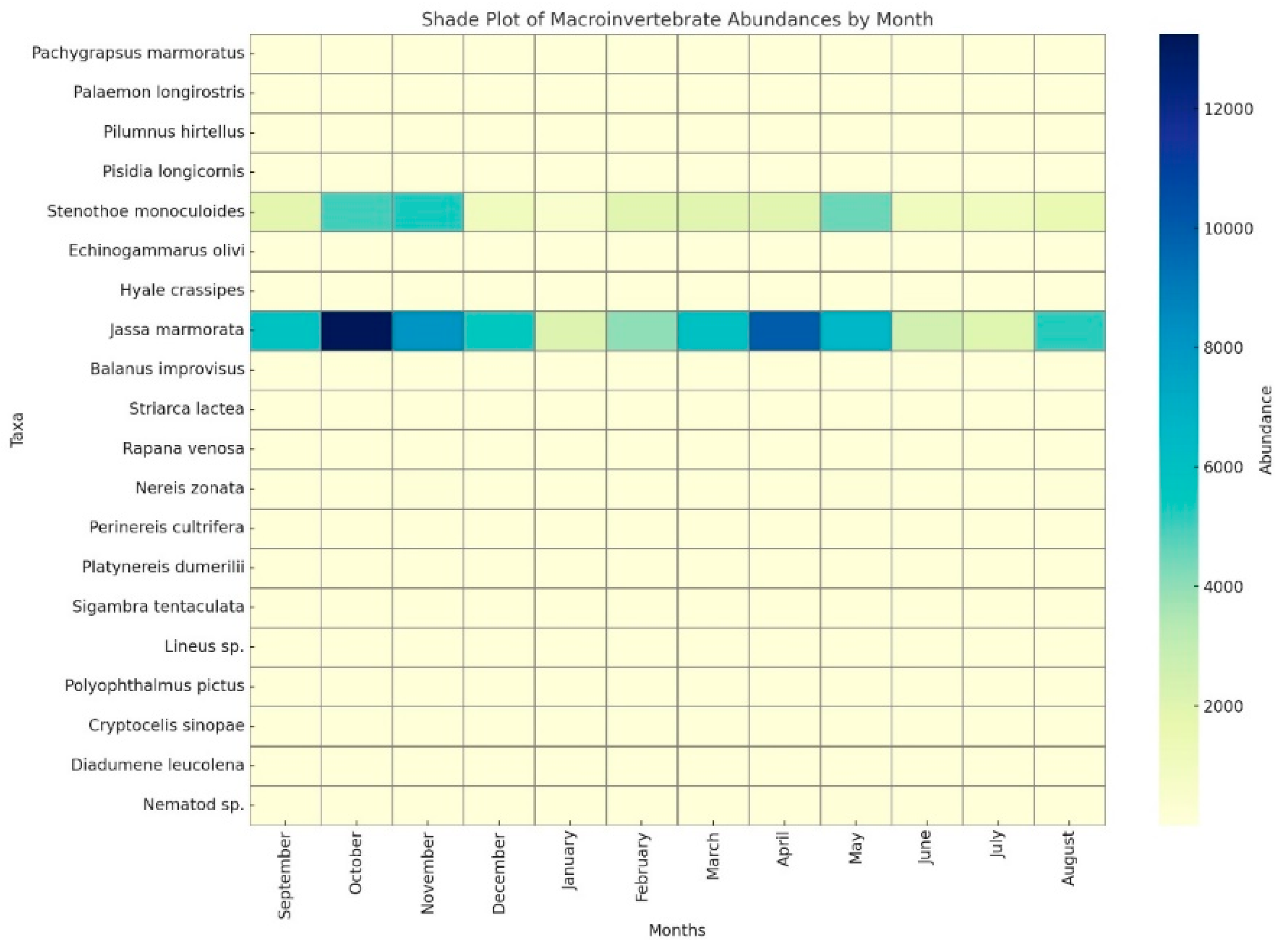

Color intensity represents the relative abundance of each taxon, as indicated in the legend. The Mean Density Variation Scale illustrates the individual densities of species across 12 different sampling periods (S1–S12), and is interpreted as follows (

Figure 7):

Dominant Species: J. marmorata (represented by the turquoise line) clearly stands out in the graphs, exhibiting consistently high densities throughout the entire sampling period. Peak values are generally observed during the early periods (e.g., S2–S4), followed by a slight decline in the mid-periods (S5–S8), and a subsequent recovery.

Second Dominant Species: S. monoculoides (red line) is the second most abundant species after J. marmorata. Its density is relatively stable, with fewer fluctuations throughout the year.

Seasonal and Temporal Fluctuations: Most species exhibited seasonal variations in abundance. Some taxa showed peak densities during specific periods (e.g., S3 and S9), while others remained at consistently low levels. Notably, increases in species richness and overall abundance were observed during the summer and autumn months (S8–S10).

Low-Abundance Species: Species such as B. improvisus, C. sinopae, and H. crassipes exhibited markedly lower densities compared to dominant taxa and showed brief peaks during certain periods (e.g., S4 or S9). Polychaetes such as N. zonata maintained relatively low but stable densities in selected periods.

These findings provide valuable insights into the temporal and seasonal density dynamics of macrofaunal species, highlighting their interactions with environmental factors and sampling conditions, and contributing to a better understanding of ecosystem variability.

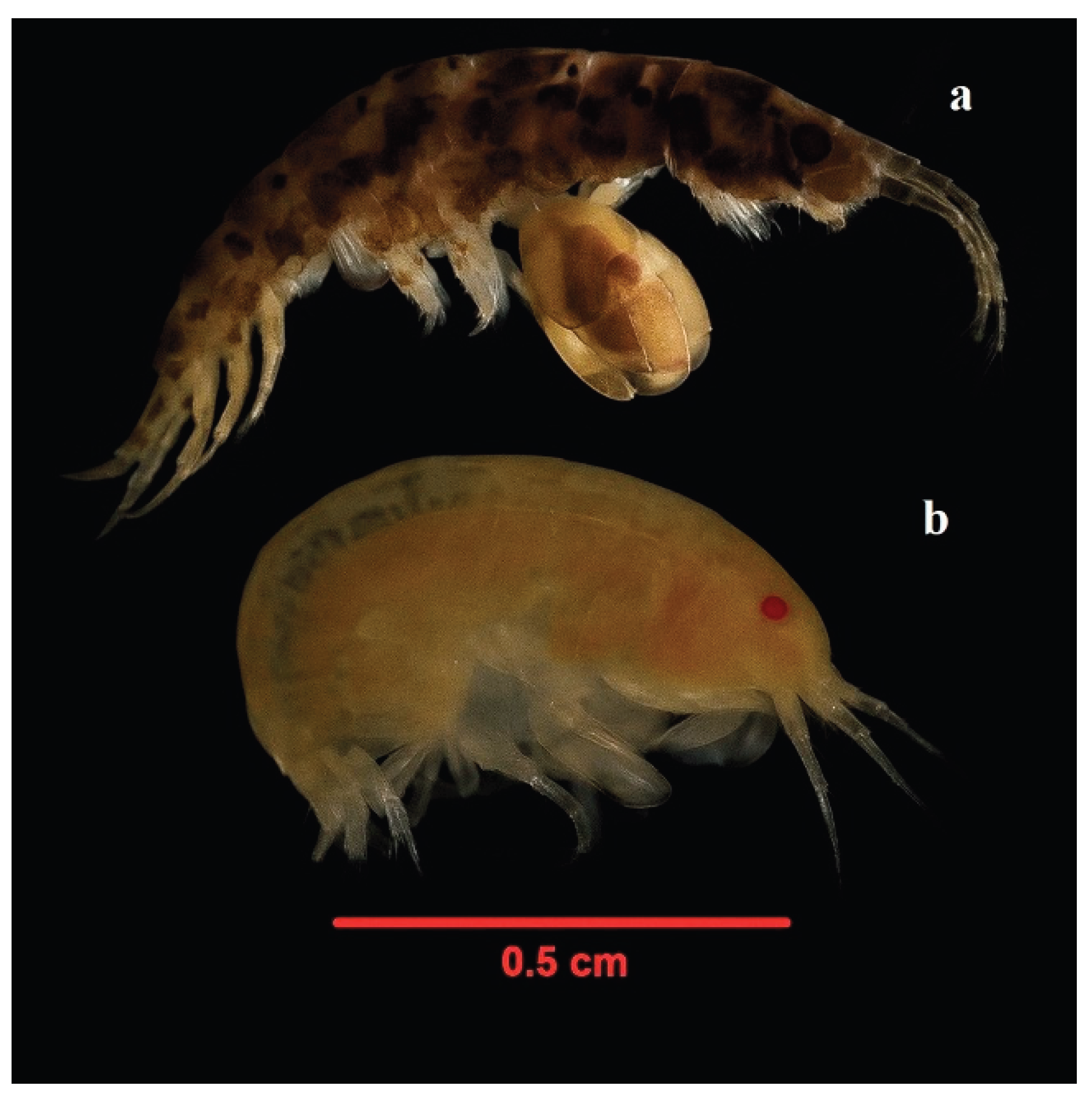

Among the macroinvertebrate species identified in this study, Jassa marmorata and Stenothoe monoculoides stood out as dominant taxa (

Figure 8). Together, these two species constituted the vast majority of total individuals, indicating their prominent role in structuring the macroinvertebrate community within the mussel aquaculture environment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings on Molluscan Fauna in the Black Sea and the Contribution of This Study

The Black Sea, as a semi-enclosed inland sea, harbors a permanent anoxic layer beginning at depths of 150–200 meters due to the presence of hydrogen sulfide (H

₂S), which limits the development of deep-sea benthic fauna [

3,

4]. Despite this constraint, the phylum Mollusca, particularly the classes Bivalvia and Gastropoda, holds a significant position within the macroinvertebrate communities of the region, ranking second in abundance after Arthropoda, and first in terms of species richness [

36,

37,

39].

However, research on molluscan species along the Turkish Black Sea coast remains limited and fragmented. Most of the existing literature is either outdated or focuses predominantly on the northern shores of the basin, including Russia, Romania, and Ukraine [

3,

39]. Studies conducted along the Turkish coastline are either based on historical data or lack contemporary ecological context [

7,

18,

37,

38,

39]

.

In this context, our study fills a critical gap by presenting updated data on molluscan fauna through systematic sampling conducted in offshore mussel aquaculture areas of the Black Sea. Notably, we identified key molluscan species such as Mytilus galloprovincialis, Bittium reticulatum, and Anadara inaequivalvis, which dominate these artificial habitats. Some of these, particularly Anadara inaequivalvis, exhibit invasive traits and may have significant implications for local benthic community dynamics.

Additionally, our study analyzed species-environment relationships using multivariate methods (e.g., RDA), revealing that dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, and substrate type are the primary drivers influencing molluscan distribution. These findings highlight the ecological sensitivity of mollusks, underscoring their potential as indicators of habitat quality and environmental change.

In conclusion, this study provides regionally specific, quantitative, and up-to-date insights into molluscan communities along the Turkish Black Sea coast. By evaluating both the ecological roles of mollusks and the impacts of aquaculture systems on their distribution, the study makes a valuable contribution to the scientific literature and offers a practical foundation for sustainable marine resource management.

4.2. Abundance and Dominance Patterns of Macroinvertebrates

This study provides significant insights into the ecological dynamics of macroinvertebrate communities associated with M. galloprovincialis cultivated in longline systems in the Black Sea. The findings emphasize the ecological roles of these organisms and highlight the contribution of artificial habitats to biodiversity.

The amphipod

J. marmorata (71.36%) emerged as the dominant species in mussel culture systems [

40,

41,

42]. Utilizing the structural complexity of mussel beds, this species evades predators and accesses food resources [

43]. Similarly, the presence of Stenothoe monoculoides underscores the importance of biogenic habitats for such species [

44].

While individual abundance peaked in autumn, species richness was highest during summer. The high autumnal abundance may be attributed to increased detritus and plankton accumulation, whereas stable environmental conditions in summer may have favored the proliferation of less dominant, opportunistic species [

45,

46]

.

Diversity index results serve as important indicators of habitat quality in the study area. When interpreted together, structural diversity indices such as Shannon–Wiener (H′), Simpson (1–D), and Pielou’s evenness index (J′) provide indirect but robust insights into habitat integrity, environmental stability, and levels of anthropogenic pressure.

High Shannon (2.11), Simpson (0.83), and Pielou (0.82) values recorded at Station S3 suggest high habitat quality, low anthropogenic stress, and ecological stability. This station exhibited both high species richness and even distribution of individuals across taxa, indicating favorable physicochemical conditions and diverse microhabitat structures.

Conversely, lower Shannon and Simpson values, along with reduced Pielou index scores at stations such as S1 and S4, indicate habitat degradation and/or increased environmental stress. These habitats may have been negatively affected by factors such as organic pollution, hypoxia, or habitat homogenization.

Comparing diversity indices among stations enables not only the evaluation of biological communities, but also the assessment of physicochemical environmental quality through the lens of bioindicators. In this context, macrozoobenthic communities are considered key biological quality elements within ecological quality classifications such as the EU Water Framework Directive [

47,

48]

.

4.3. Influence of Environmental Factors on Community Dynamics

As observed in this study, pH was identified as a key determinant of macroinvertebrate distribution and abundance among environmental parameters such as temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and pH [

49]

. While

J. marmorata demonstrated tolerance to environmental changes, species such as

P. marmoratus and

B. improvisus showed greater prevalence within specific oxygen and salinity ranges [

50]

.

RDA results revealed that macroinvertebrate species composition in the mussel longline system was significantly associated with environmental gradients. The analysis showed that a substantial proportion of the variance was explained by pH (41.0%) and salinity (34.5%), indicating that these two parameters were the primary drivers of species distribution within the study site.

Species such as Dialeu, Crysin, Palon, and Nerzon were positioned along higher pH and salinity gradients, suggesting their adaptation to such conditions. Conversely, Pacmar, Jasmar, and Rapven were associated with lower pH and oxygen levels, indicating tolerance to suboptimal or stressful environments. Species like Stemons and Pladum were oriented along the temperature axis, reflecting their sensitivity to seasonal temperature changes.

These findings demonstrate that mussel aquaculture systems should be considered not only for their production value but also as biodiversity hotspots responsive to environmental gradients. The results offer a strong foundation for understanding the bioindicator potential of macroinvertebrates and their responses to specific ecological niches.

4.4. Implications for Aquaculture Management

While mussel aquaculture creates artificial habitats that enhance local biodiversity, it also introduces challenges such as space and resource competition with species like

B. improvisus [

18]

. This issue becomes particularly prominent during larval settlement periods, potentially hindering mussel growth.

Therefore, larval collector deployment should be carefully timed. To prevent settlement by

Balanus larvae, which peak during July–August [

50], collectors should be deployed in May, and surface cleaning strategies should be implemented to reduce colonization.

5. Conclusions

Invertebrates inhabiting mussel beds utilize diverse food sources such as plankton, organic particles, and bacteria, contributing to ecosystem balance. Benthic invertebrates in the Black Sea play a critical role in ecosystem health and biodiversity conservation. Mussel beds represent structured habitats dominated by dense mussel populations that provide shelter and food for numerous invertebrate species. Amphipods, in particular, seek refuge among mussel shells and feed on organic matter. These symbiotic relationships enhance biodiversity and support energy flow within the ecosystem.

This study evaluated the ecological roles and biodiversity contributions of macroinvertebrates associated with Mytilus galloprovincialis cultivated in offshore longline systems in the Black Sea. Over the course of one year, Jassa marmorata was identified as the dominant species. Species richness peaked in summer, while individual abundance was highest in autumn.

The findings suggest that mussel aquaculture systems offer critical habitats that support local biodiversity in addition to economic production. However, challenges such as interspecies competition with Balanus improvisus may be mitigated through proper timing and depth management in farming practices.

Importantly, this study supports the hypothesis that offshore mussel longline systems function as artificial reef structures that enhance local benthic biodiversity and contribute to overall ecosystem resilience. High diversity index values and species-specific responses to environmental gradients indicate that such systems not only serve as productive aquaculture platforms but also as ecologically valuable habitats. Sustainable aquaculture practices, including habitat-sensitive timing and settlement control strategies, are therefore essential for maintaining both ecological integrity and economic viability in marine ecosystems.

Author Contributions

The theoretical framework and study design were developed by Eylem AYDEMİR ÇİL. All material preparation, data collection, analysis, manuscript drafting, and final approval were completed solely by the author.

Funding

No funding: grants, or financial support were received for the preparation of this article.

Ethical Statement

The author has read, understood, and complied with the ʺAuthors' Ethical Responsibilitiesʺ declaration.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses sincere gratitude to Sinop University Faculty of Fisheries and Prof. Dr. Meryem Yeşim Çelik for establishing the Mussel Research Facility, which made this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Murray, J.W.; Yakushev, E.V.; Neretin, L.N. Hydrography and chemistry of the Black Sea. Deep-Sea Research Part I. 1991.

- Özsoy, E.; Ünlüata, Ü. Oceanography of the Black Sea: a review of some recent results. Earth-Science Reviews 1997, 42, 231–272.

- Zaitsev, Y.P.; Mamaev, V. Marine biological diversity in the Black Sea: A study of change and decline. New York: United Nations Publications 1997.

- Mee, L.D. The Black Sea in crisis: a need for concerted international action. Ambio 1992, 21, 278–286. [Google Scholar]

- Karakaya, E.; Öztürk, M.; Yılmaz, A. Karadeniz’in biyoçeşitliliği ve ekolojik dengesi üzerine bir değerlendirme. Journal of Marine Biology and Ecology 2020, 12, 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Altuğ, G.; Aktan, Y.; Oral, M.; Topaloğlu, B.; Oğuz, A. Bacterial and nutrient properties of the Golden Horn Estuary and their relationships with zooplankton species. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2011, 11, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar, M.E.; Bakır, K.; Öztürk, B.; Doğan, A.; Açik, Ş.; Kırkım, F.; et al. Spatial distribution pattern of macroinvertebrates associated with the black mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis (Mollusca: Bivalvia) in the Sea of Marmara. Journal of Marine Systems 2020a, 211. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, L.; Bulatov, O. Mytilus galloprovincialis populations in the Black Sea. Hydrobiologia 1990, 187(1–2), 25–33. [CrossRef]

- Wijsman, J.W.M.; Smaal, A.C.; Herman, P.M.J. Modelling processes in the mussel Mytilus edulis L. population dynamics. Journal of Sea Research 1999, 41, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seed, R. The ecology of Mytilus edulis L. (Lamellibranchiata) on exposed rocky shores: I. Breeding and settlement. Oecologia 1969 3, 277–316. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.J.; Nickols, G. The influence of environmental conditions on growth and reproduction in Mytilus edulis L. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 1988, 122, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehn, R.K.; Bayne, B.L. Towards a physiological and genetical understanding of the energetics of the stress response. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 1989, 37(1–2), 157–171. [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, S.A.; Castilla, J.C. Resource partitioning between intertidal predators in rocky shores of central Chile. Oecologia 1990, 81, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellan-Santini, D. Contribution à l'étude écologique des amphipodes gammariens sur substrat rocheux en Méditerranée. Tethys 1969, 1, 751–758. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya, M. Faunal structures associated with intertidal and subtidal mussel beds. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2002, 173, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmann, S. Mussel beds: A unique habitat for intertidal fauna. Helgoländer Meeresuntersuchungen 1990, 44(3–4), 229–243. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, T.H.; Rosenberg, R. Macrobenthic succession in relation to organic enrichment and pollution of the marine environment. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review 1978, 16, 229–311. [Google Scholar]

- Karayücel, H.; Doğan, H.; Aydın, M. The potential for mussel aquaculture in the Black Sea: A preliminary assessment. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2002, 12, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Çelik, M.Y. Türkiye’de midye yetiştiriciliği: Potansiyel ve uygulamalar. Ege Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2006, 23, 387–394. [Google Scholar]

- Çınar, M.E.; Katağan, T.; Öztürk, B.; Egemen, Ö.; Ergen, Z.; Kocataş, A.; Önen, M. Karadeniz bentik makroomurgasızları. Turkish Journal of Marine Science 2020b 26, 165–182.

- Öztürk, B.; Bitlis, B.; Türkçü, N. Diversity of Mollusca along the coasts of Türkiye. Turkish Journal of Zoology 2024, 48, 531–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauchald, K. The polychaete worms: Definitions and keys to the orders, families and genera. Smithsonian Institution Press.1977.

- Çınar, M.E.; Ergen, Z.; Dağlı, E. Checklist and zoogeographic affinities of polychaetes from the coasts of Turkey. Zootürler 2006, 1168, 1–22.

- Poppe, G.T.; Goto, Y. European seashells. Verlag Christa Hemmen 1991.

- Öztürk, B.; Doğan, A.; Katağan, T.; Salman, A. Marine molluscs of the Turkish coasts: A checklist. Turkish Marine Research Foundation (TUDAV) 2014.

- Holthuis, L.B. FAO species catalogue Vol. 1: Shrimps and prawns of the world. FAO Fisheries Synopsis 1980, No. 125, Vol. 1.

- Ruffo, S. The Amphipoda of the Mediterranean. Mémoires de l’Institut Océanographique, Monaco, 1982–1989.

- WoRMS World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved from 2024, https://www.marinespecies.org/.

- O.B.I.S. Ocean Biodiversity Information System. Retrieved from 2024, https://obis.org/.

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. University of Illinois Press. 1949.

- Pielou, E.C. Ecological Diversity. Wiley-Interscience 1975.

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Wagner, H. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.5-7. 2020.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2022 https://www.R-project.org/.

- Zenkevitch, L. Biology of the Seas of U.S.S.R. George Allen and Unwin, London 1963.

- Bakan, G.; Büyükgüngör, H. The Black Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2000, 41: 24-43.

- Çulha, M. Türomical and ecological characteristics of Prosobranchia (Mollusca-Gastropoda) species distributed around Sinop, PhD dissertation, Ege University, İzmir, 2004 150 pp.

- Çulha, M.; Bat, L.; Çulha, S.T.; Çelik, M.Y. Benthic mollusk composition of some facies in the upper-infralittoral zone of the southern Black Sea, Turkey. Turkish Journal of Zoology 2010, 34, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, E.; Ünsal, M.; Bingel, F. Faunal community of softbottom molluscs along the Turkish Black Sea. Turk. J. Zool. 1993,17: 189-206.

- Anistratenko, V.V.; Anistratenko, O.Y. Fauna of Ukraine.Vestnik Zoologii 2001, 29: 1-240.

- Franz, D.R.; Mohamed, S.A. Short-term growth and survival of intertidal amphipods in the presence of mussels. Marine Biology 1989, 102, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, M.; Kocataş, A.; Katağan, T. Amphipod fauna of the Turkish central Black Sea region. Turkish Journal of Zoology 2001, 25, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sezgin, M.; Çil Aydemir, E. Crustacean fauna of a mussel cultivated raft system in the Black Sea. Arthropods 2013, 2, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Caine, E.A. Feeding mechanisms and ecology of Crustacea: Amphipoda and Caprellidea. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1983.

- Kamenskaya, O.E. Ecological characteristics of amphipods in the Black Sea. Hydrobiological Journal 1979, 15, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, R.W. The establishment and development of a marine epifaunal community. Ecological Monographs 1977, 47, 37–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoner, A.W. The role of feeding biology and competitor interactions in the dynamics of bivalve populations. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 1980, 45, 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja, Á.; Franco, J.; Pérez, V. A marine biotic index to establish the ecological quality of soft-bottom benthos within European estuarine and coastal environments. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2000, 40, 1100–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, H.; Kröncke, I. Seasonal variability of benthic indices: an approach to test the applicability of different indices for ecosystem quality assessment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2005, 50, 1490–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, C.A.; Miner, C.M.; Raimondi, P.T.; Gaines, S.D. Intertidal community structure and oceanographic patterns around Santa Cruz Island, California, USA. Marine Biology 2006, 149, 1177–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, Y.; Öztürk, B. Black Sea Biological Diversity: Turkey. Istanbul: Turkish Marine Research Foundation 2001.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).