Submitted:

15 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

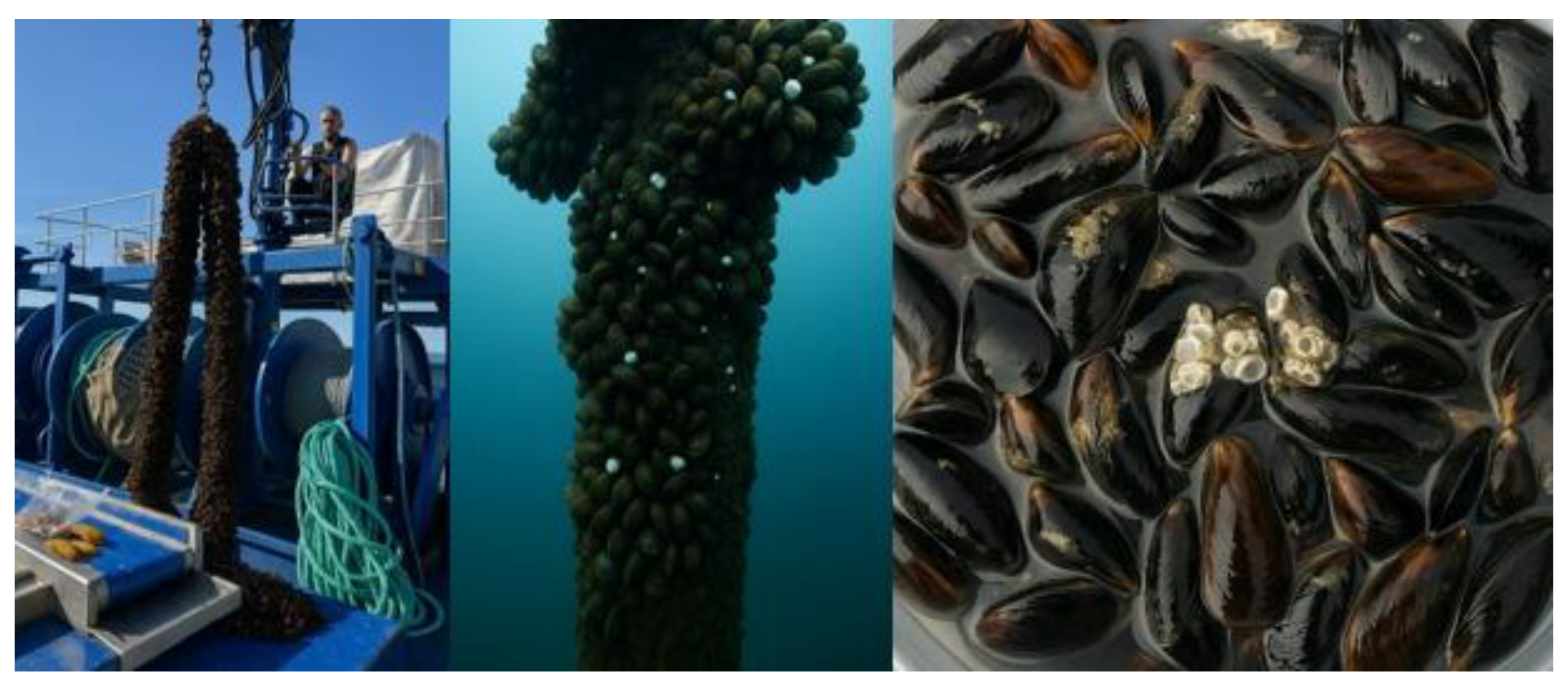

2.1. Longline System

2.2. Environmental Parameters

2.3. Mussel Sample Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

- H' = Shannon diversity index

- Pi = Proportion of individuals in taxon i

- Ni = Number of individuals in taxon i

- N = Total number of individuals in the sample

- S = Total number of taxa

3. Results

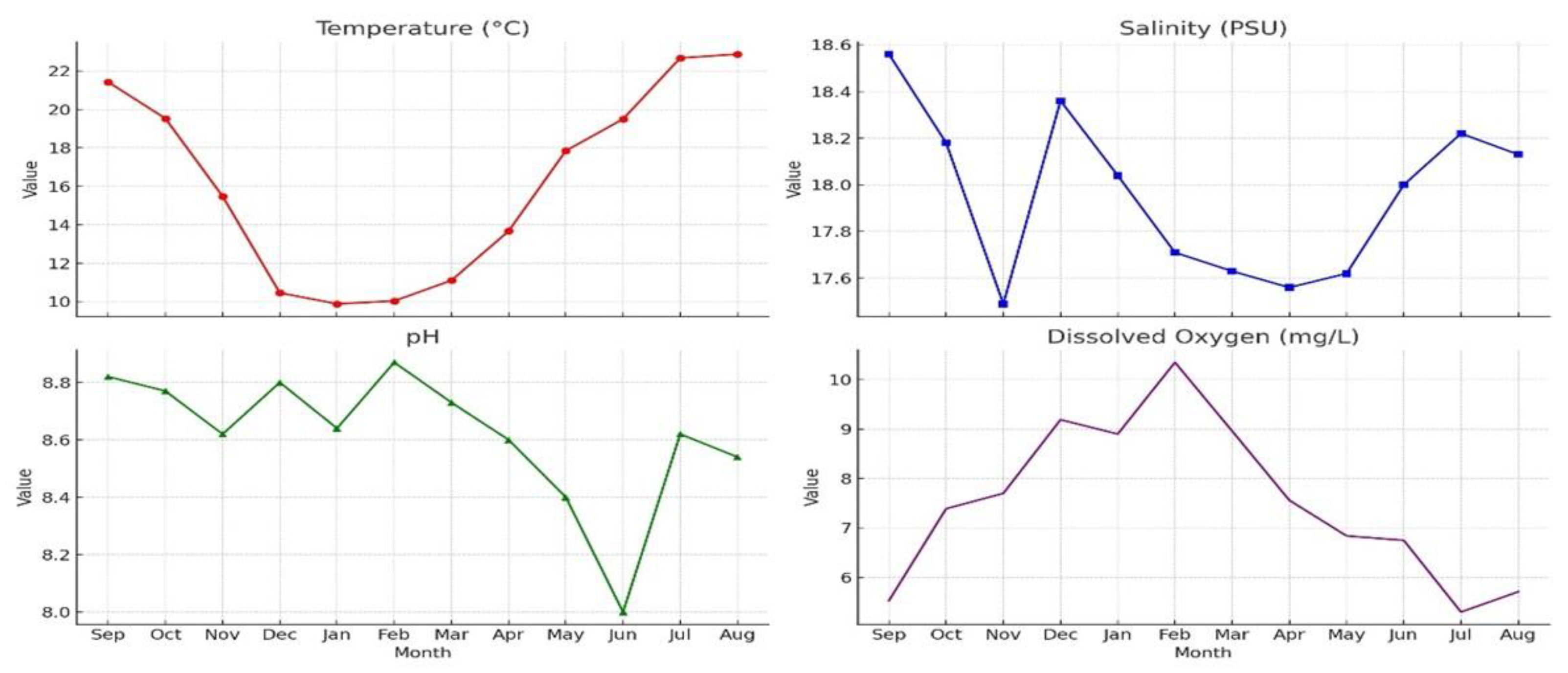

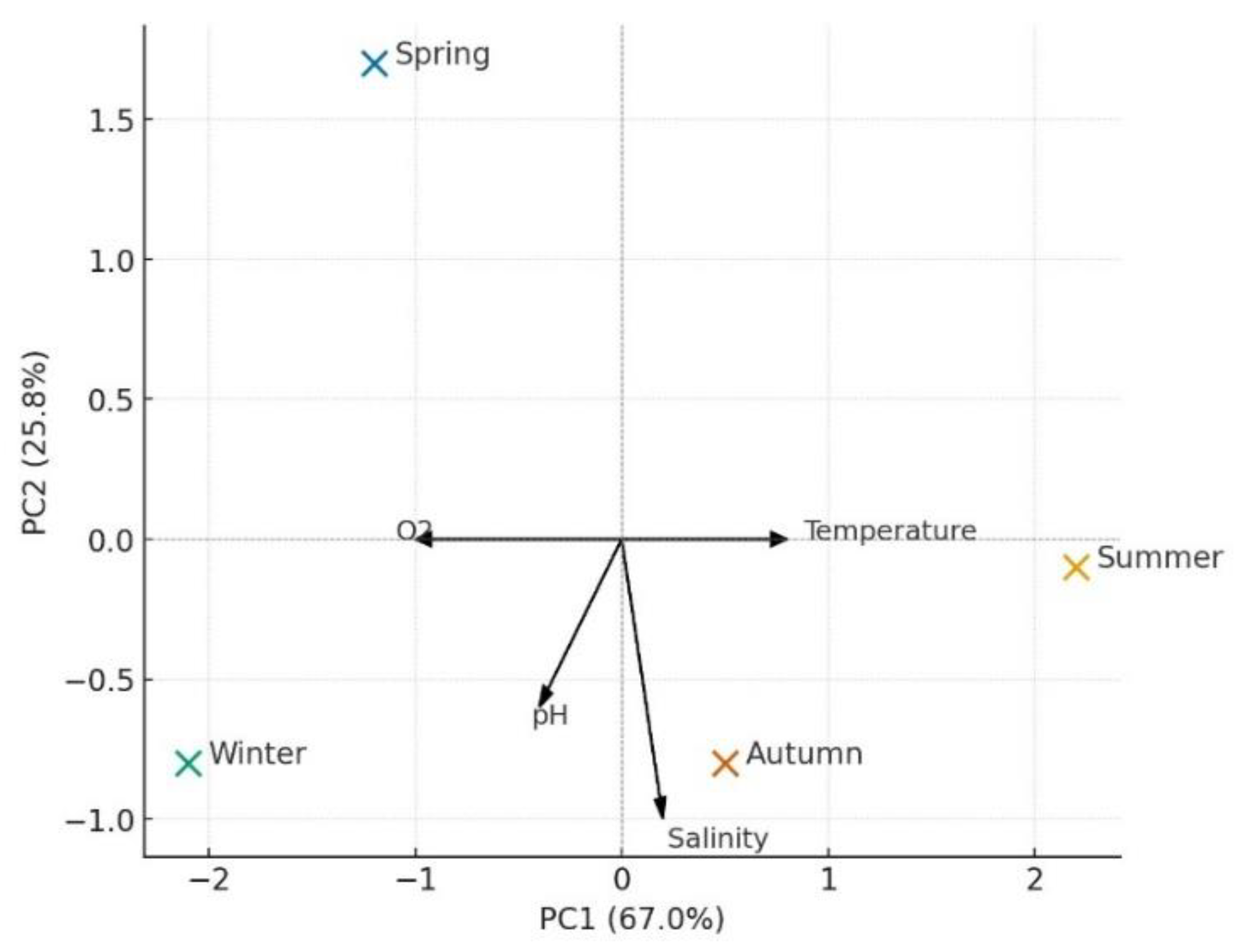

3.1. Physicochemical Parameters and Seasonal Variations

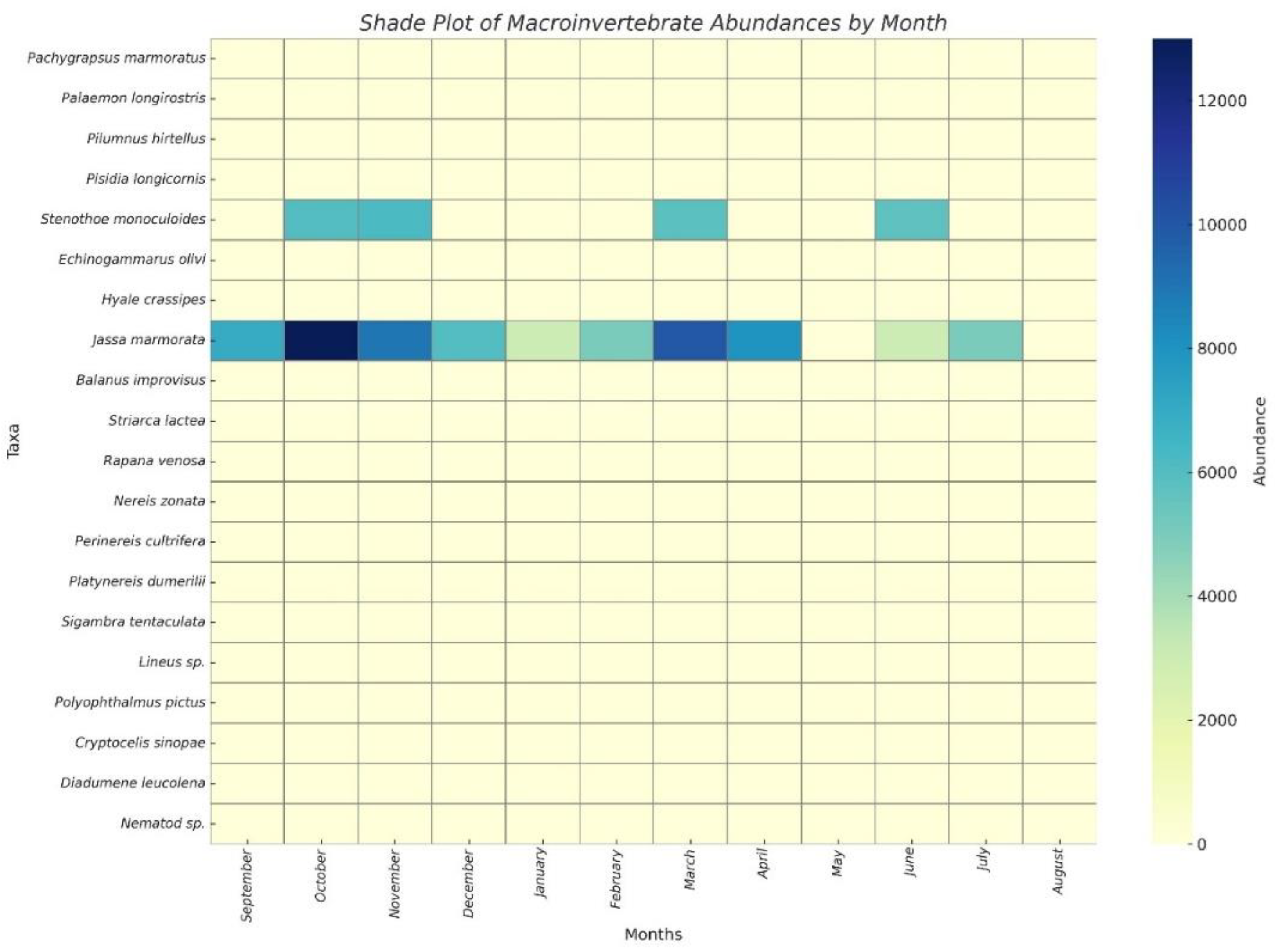

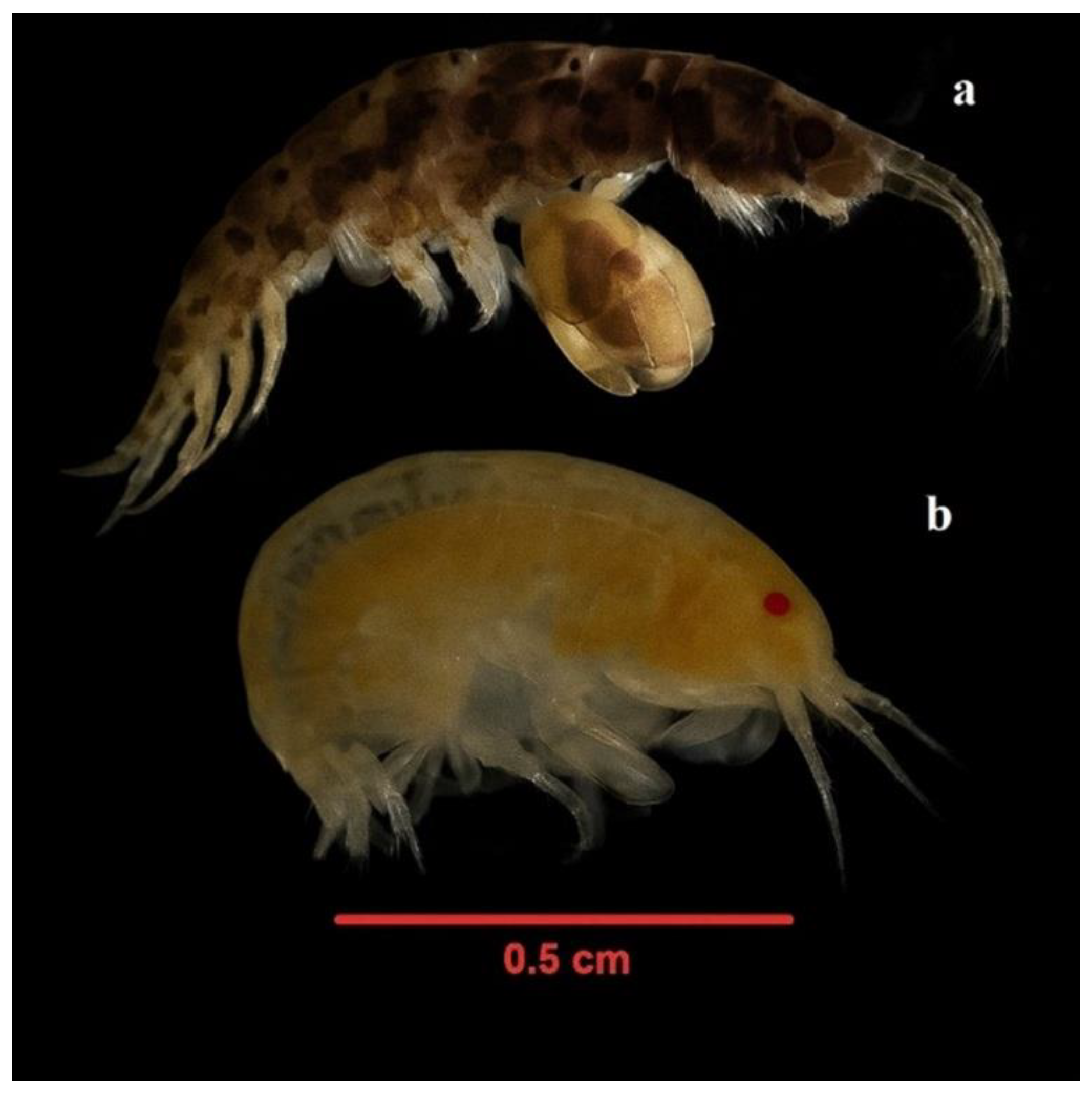

3.2. Macroinvertebrate Community

| Species | Mean Relative Abundance (%) | Ecological Role |

|---|---|---|

| Jassa marmorata | 71.36% | Opportunist, habitat-forming |

| Stenothoe monoculoides | 27.8% | Detritivore, inhabits sticky substrates |

| Nereis zonata | 0.37% | Omnivore, sediment bioturbator |

| Nematoda (general) | 0.12% | Microscopic, sensitive to organic matter |

| Hyale crassipes | 0.10% | Detritivore, shows seasonal abundance trend |

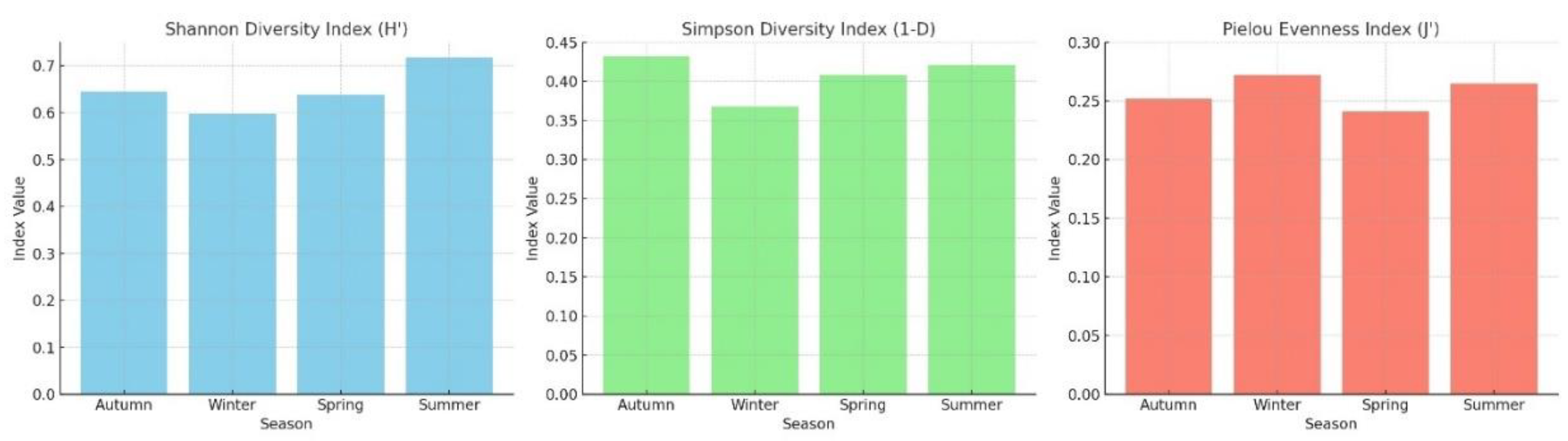

3.3. Species Distribution and Seasonal Variation

| September-2023 | October | November | December | January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August-2024 | SUM | %D | |||||||||||||||

| RDA * | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S 6 | S7 | S 8 | S9 | S10 | S11 | S12 | ||||||||||||||||

| CRUSTACEA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Decapoda | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pachygrapsus marmoratusPacmar | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0,0120 | ||||||||||||||

| Palaemon longirostris Pallon | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0,0040 | ||||||||||||||

| Pilumnus hirtellus Pilhir | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0,0221 | ||||||||||||||

| Pisidia longicornis Pislon | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 16 | 0,0160 | ||||||||||||||

| Amphipoda | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stenothoe monoculoides Stemon | 1900 | 5000 | 5290 | 1040 | 500 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 4520 | 1000 | 1006 | 1470 | 27726 | 27,8041 | ||||||||||||||

| Echinogammarus oliviEcholi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 13 | 0,0130 | ||||||||||||||

| Hyale crassipes Hyacra | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 30 | 2 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 102 | 0,1023 | ||||||||||||||

| Jassa marmorata Jasmar | 5800 | 13250 | 8160 | 5530 | 2100 | 4000 | 6000 | 10000 | 6600 | 2500 | 2024 | 5200 | 71164 | 71,3645 | ||||||||||||||

| CİRRİPEDİA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Balanus improvisus Balimp | 7 | 0 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 29 | 0,0291 | ||||||||||||||

| MOLLUSCA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Striarca lactea Strlac | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0,0040 | ||||||||||||||

| Rapana venosa Rapven | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0,0030 | ||||||||||||||

| ANNELIDAE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polychaetes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nereis zonata | Nerzon | 6 | 2 | 57 | 16 | 47 | 0 | 20 | 13 | 53 | 41 | 12 | 100 | 367 | 0,3680 | |||||||||||||

| Perinereis cultrifera | Percul | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0,0030 | |||||||||||||

| Platynereis dumerilii | Pladum | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0,0050 | |||||||||||||

| Sigambra tentaculata | Sigten | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 15 | 17 | 0,0170 | |||||||||||||

| Polyophthalmus pictus | Polpic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 0,0070 | |||||||||||||

| Nemertea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lineus sp. | Lineus | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0,0030 | |||||||||||||

| Platyhelminthes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cryptocelis sinopae | Crysin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 19 | 0,0191 | |||||||||||||

| CHİNİDARİA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anemone | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diadumene leucolena | Diaieu | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 45 | 14 | 3 | 78 | 0,0782 | |||||||||||||

| NEMATODA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nematod sp. | Nemato | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 68 | 0 | 0 | 42 | 125 | 0,1254 | |||||||||||||

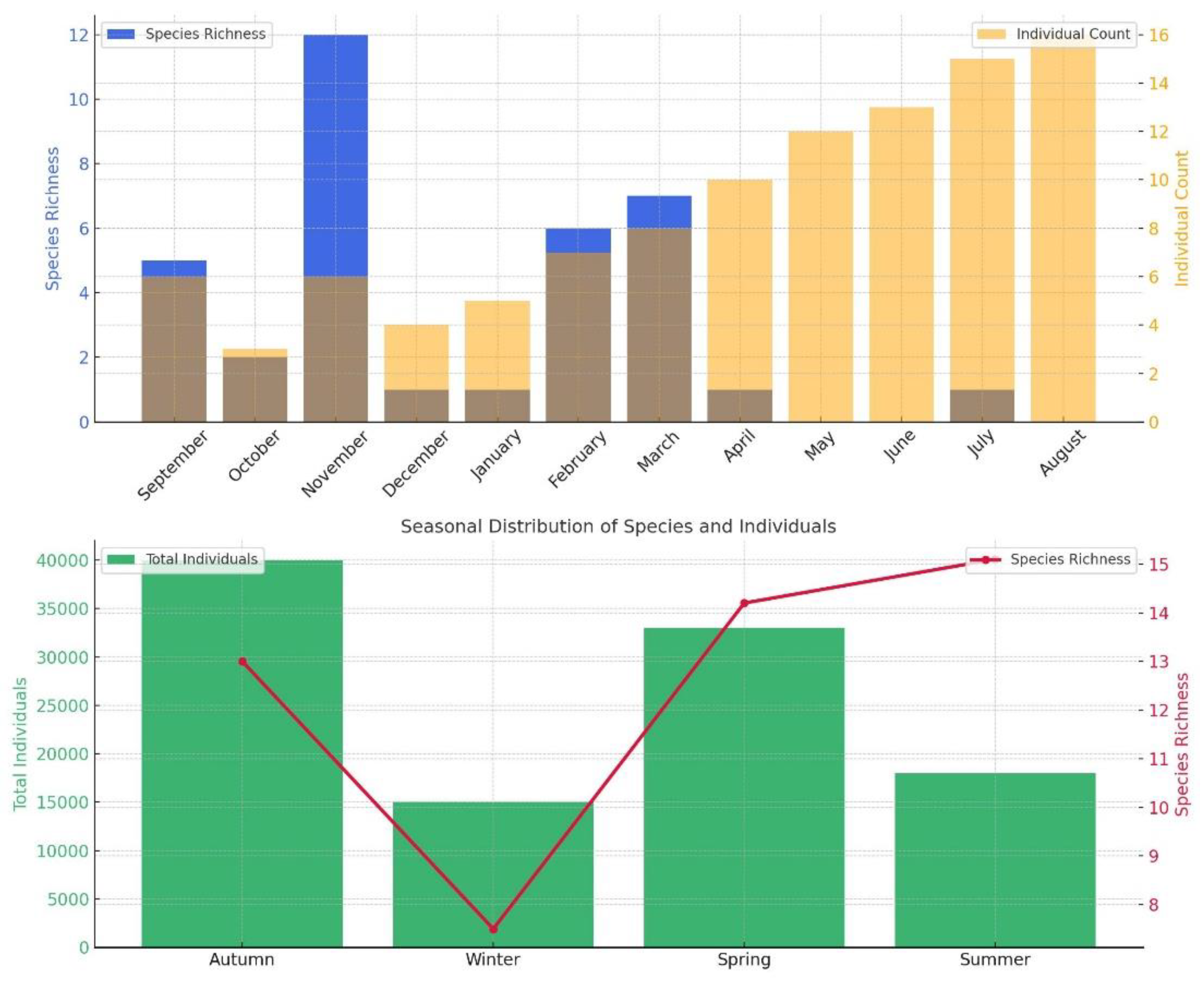

3.4. Abundance and Species Richness

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings on the Molluscan Fauna of the Black Sea and the Contribution of This Study

4.2. Abundance and Dominance Patterns of Macroinvertebrates

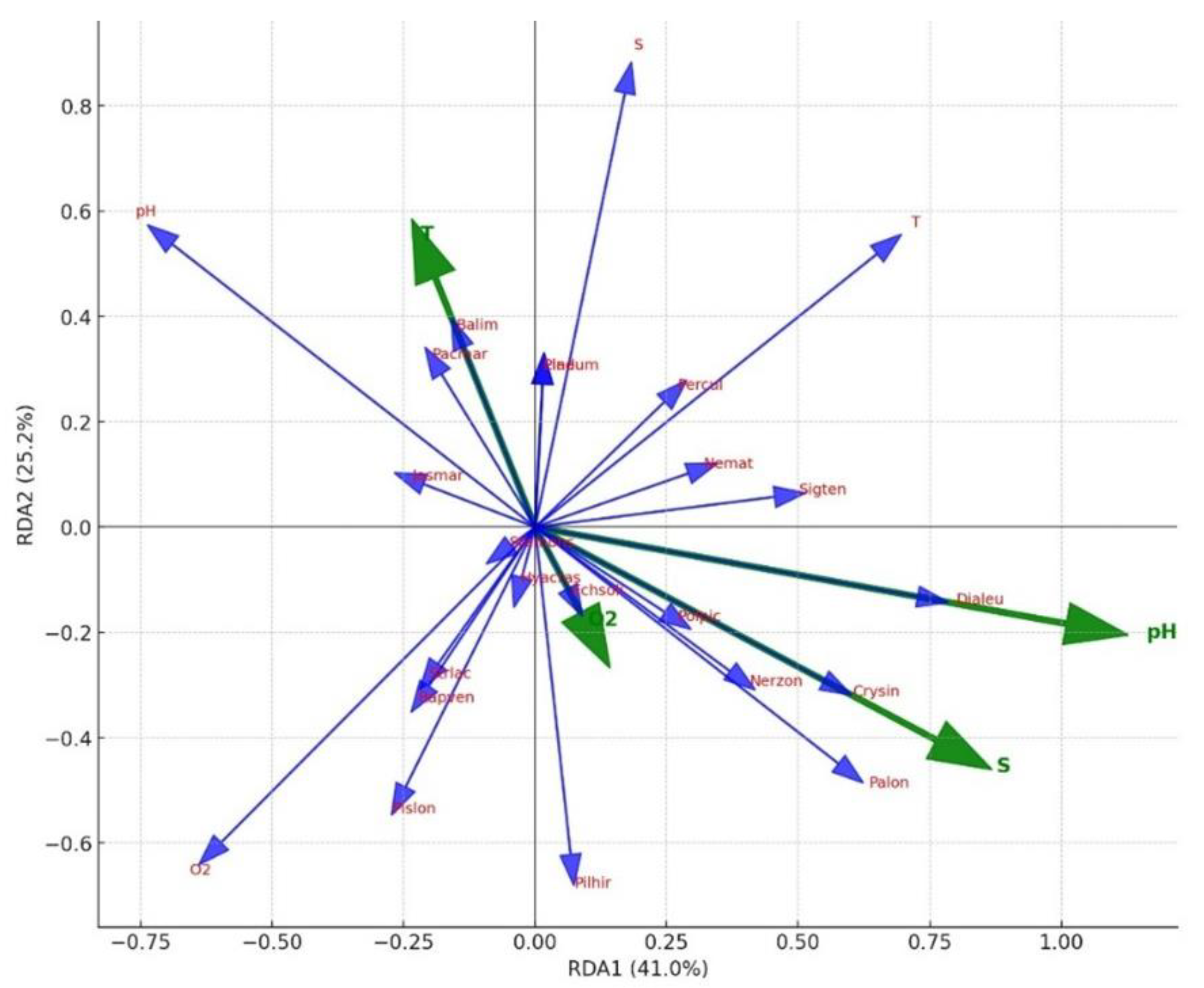

4.3. Environmental Drivers of Community Structure

4.4. Management Implications for Mussel Aquaculture

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray JW, Top Z, Özsoy E. Hydrographic properties and ventilation of the Black Sea. Deep Sea Research Part A: Oceanographic Research Papers 1991, 38, S663–S689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsoy E, Ünlüata Ü. Oceanography of the Black Sea: A review of some recent results. Earth-Science Reviews 1997, 42, 231–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev YP, Mamaev V. Marine biological diversity in the Black Sea: A study of change and decline. New York: United Nations Publications; 1997.

- Mee, LD. The Black Sea in crisis: A need for concerted international action. Ambio 1992, 21, 278–286. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov L, Bulatov O. Mytilus galloprovincialis populations in the Black Sea. Hydrobiologia 1990, 187, 25–33.

- Aydemir-Çil E, Birinci-Özdemir Z, Özdemir S. First find of the starfish Asterias rubens Linnaeus 1758 off the Anatolian coast of the Black Sea (Sinop). Marine Biological Journal 2023, 8, 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Birinci-Özdemir Z, Aydemir-Çil E, Özdemir S, Duyar HA. An important species for Black Sea biodiversity: Some population characteristics of invasive sea vase (Ciona intestinalis Linnaeus, 1767) distributed on the Sinop shores. Turkish Journal of Zoology 2024, 48, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuğ G, Aktan Y, Oral M, Topaloğlu B, Oğuz A. Bacterial and nutrient properties of the Golden Horn Estuary and their relationships with zooplankton species. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2011, 11, 309–316. [Google Scholar]

- Çınar ME, Bakır K, Öztürk B, Doğan A, Açik Ş, Kırkım F, et al. Spatial distribution pattern of macroinvertebrates associated with the black mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis (Mollusca: Bivalvia) in the Sea of Marmara. Journal of Marine Systems 2020, 211, 103402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callier MD, McKindsey CW, Desrosiers G. Multi-scale spatial variations in benthic sediment geochemistry and macrofaunal communities under a suspended mussel culture. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2007, 348, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabi G, Manoukian S, Spagnolo A. Impact of an open-sea suspended mussel culture on macrobenthic community (Western Adriatic Sea). Aquaculture 2009, 289, 54–63. [CrossRef]

- Borja A, Franco J, Pérez V. A marine biotic index to establish the ecological quality of soft-bottom benthos within European estuarine and coastal environments. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2000, 40, 1100–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss H, Kröncke I. Seasonal variability of benthic indices: An approach to test the applicability of different indices for ecosystem quality assessment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2005, 50, 1490–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross AH, Nisbet RM. Dynamic models of growth and reproduction of the mussel Mytilus edulis L. Functional Ecology 1990, 4, 777–787.

- Seed, R. The ecology of Mytilus edulis L. (Lamellibranchiata) on exposed rocky shores: I. Breeding and settlement. Oecologia 1969, 3, 277–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, RJ. The reproductive cycle and physiological ecology of the mussel Mytilus edulis in a subarctic, non-estuarine environment. Marine Biology 1984, 79, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehn RK, Bayne BL. Towards a physiological and genetical understanding of the energetics of the stress response. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 1989, 37, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete SA, Castilla JC. Predation by Norway rats in the intertidal zone of central Chile. Marine Ecology Progress Series 1993, 92, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellan-Santini, D. Contribution à l’étude des peuplement infralittoraux sur substrat rocheux (Etude qualitative et quantitative de la franch Superiere). Recherche Travaux Station Marine Endoume 1969, 63, 9–294. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya, M. Faunal structures associated with patches of mussels on East Asian coasts. Helgoland Marine Research 2002, 56, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmann, S. Mussel beds: A unique habitat for intertidal fauna. Helgoländer Meeresuntersuchungen 1990, 44, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayücel H, Doğan H, Aydın M. The potential for mussel aquaculture in the Black Sea: A preliminary assessment. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2002, 12, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Çelik, MY. Türkiye’de midye yetiştiriciliği: Potansiyel ve uygulamalar. Ege Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2006, 23, 387–394. [Google Scholar]

- Çınar ME, Katağan T, Öztürk B, Egemen Ö, Ergen Z, Kocataş A, et al. Karadeniz bentik makroomurgasızları. Turkish Journal of Marine Science 2020, 26, 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk B, Doğan A, Katağan T, Salman A. Marine molluscs of the Türkiye coasts: A checklist. Istanbul: Türkiye Marine Research Foundation (TUDAV), 2014.

- Robichaud L, Richard M, Gendron L, McKindsey CW, Archambault P. Influence of suspended mussel aquaculture and an associated invasive ascidian on benthic macroinvertebrate communities. Water 2022, 14, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauchald, K. The polychaete worms: Definitions and keys to the orders, families and genera. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press; 1977.

- Çınar ME, Ergen Z, Dağlı E. Checklist and zoogeographic affinities of polychaetes from the coasts of Türkiye. Zootaxa 2006, 1168, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Poppe GT, Goto Y. European seashells. Wiesbaden: Verlag Christa Hemmen; 1991.

- Holthuis, LB. FAO species catalogue Vol. 1: Shrimps and prawns of the world. FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 125, Vol. 1. Rome: FAO; 1980.

- Ruffo, S. The Amphipoda of the Mediterranean. Monaco: Mémoires de l’Institut Océanographique; 1982–1989.

- WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. 2024. Available from: https://www.marinespecies.org/.

- OBIS. Ocean Biodiversity Information System. 2024. Available from: https://obis.org/.

- Shannon CE, Weaver W. The mathematical theory of communication, University of Illinois Press: Urbana, 1948.

- Pielou, EC. Ecological diversity. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1975.

- Zenkevitch, L. Biology of the seas of the U.S.S.R. London: George Allen and Unwin; 1963.

- Bakan G, Büyükgüngör H. The Black Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2000, 41, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çulha, M. Türomical and ecological characteristics of Prosobranchia (Mollusca-Gastropoda) species distributed around Sinop. [PhD dissertation]. İzmir: Ege University; 2004. 150 p.

- Çulha M, Bat L, Çulha ST, Çelik MY. Benthic mollusk composition of some facies in the upper-infralittoral zone of the southern Black Sea, Türkiye. Turkish Journal of Zoology 2010, 34, 523–532. [Google Scholar]

- Anistratenko VV, Anistratenko OY. Fauna of Ukraine. Vestnik Zoologii 2001, 29, 1–240. [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu E, Betil Ergev M. Spatio-temporal distribution of soft-bottom epibenthic fauna on the Cilician shelf (Turkey), Mediterranean Sea. Revista de Biología Tropical 2008, 56, 1919–1946. [Google Scholar]

- Bat L, et al. Long-term changes and causes of biota assemblages in the southern Black Sea coasts. Marine Biology Research 2024, 20, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault P, Grant J, Brosseau C. Secondary productivity of fish and macroinvertebrates in mussel aquaculture sites. Secondary productivity of fish and macroinvertebrates in mussel aquaculture sites. ICES CM 2008, H, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Bat L, et al. Biological diversity of the Turkish Black Sea coast. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2011, 11, 683–692. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-García JM, Ruiz-Tabares A, Baeza-Rojano E, Cabezas MP, Díaz-Pavón JJ, Pacios I, et al. Trace metals in Caprella (Crustacea: Amphipoda). A new tool for monitoring pollution in coastal areas? Ecological Indicators 2010, 10, 734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin M, Çil Aydemir E. Crustacean fauna of a mussel cultivated raft system in the Black Sea. Arthropods 2013, 2, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Grintsov, VA. Taxonomic diversity of Amphipoda (Crustacea) from the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. Marine Biological Journal 2022, 7, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolyuchkina GA, et al. The role of abiotic environmental factors in the vertical distribution of macrozoobenthos at the northeastern Black Sea coast. Biology Bulletin 2020, 47, 1126–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar ME, Dağlı E, Katağan T. Seasonal changes in the soft-bottom polychaete assemblages in the Black Sea. Mediterranean Marine Science 2016, 17, 150–162. [Google Scholar]

- Karayücel İ, Karayücel S, Erdem M. Settlement and growth of the barnacle (Balanus improvisus) on ropes used in mussel cultivation. Turkish Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences 2002, 26, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsev Y, et al. The Black Sea. Exotic species in the Aegean, Marmara, Black, Azov and Caspian Seas. Istanbul: Turkish Marine Research Foundation; 2001. p. 73–138.

- Commito JA, Dankers N. Dynamics of spatial and temporal complexity in European and North American soft-bottom mussel beds. In: Reise K, editor. Ecological comparisons of sedimentary shores, 2001; 39–59.

- Norling P, Kautsky N. Patches of the mussel Mytilus sp. are islands of high biodiversity in subtidal sediment habitats in the Baltic Sea. Aquatic Biology 2008, 4, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amours O, Archambault P, McKindsey CW, Johnson LE. Local enhancement of epibenthic macrofauna by aquaculture activities. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2008, 371, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKindsey CW, Archambault P, Callier M, Olivier F. Influence of suspended and off-bottom mussel culture on the sea bottom and benthic habitats: A review. Canadian Journal of Zoology 2011, 89, 622–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumway SE, editor. Shellfish aquaculture and the environment, Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, 2011.

- Forrest BM, Keeley NB, Hopkins GA, Webb SC, Clement DM. Bivalve aquaculture in estuaries: Review and synthesis of oyster cultivation effects. Aquaculture 2009, 298, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser MJ, Laing I, Utting SD, Burnell GM. Environmental impacts of bivalve mariculture. Journal of Shellfish Research 1998, 17, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- McKindsey CW, Thetmeyer H, Landry T, Silvert W. Review of recent carrying capacity models for bivalve culture and recommendations for research and management. Aquaculture 2006, 261, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callier MD, McKindsey CW, Desrosiers G. Influence of suspended mussel lines on the biogeochemical fluxes in the benthic boundary layer. Marine Environmental Research 2013, 83, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford CM, Macleod CK, Mitchell IM. Effects of shellfish farming on the benthic environment. Aquaculture 2003, 224, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govorın, I A. The predatory marine gastropod Rapana venosa (Valenciennes, 1846) in Northwestern Black Sea: morphometric variations, imposex appearance and biphallia phenomenon. In: Molluscs. IntechOpen, 2018.

- Tıčına, V; Katavıć, I; Grubıšıć, L. Marine aquaculture impacts on marine biota in oligotrophic environments of the Mediterranean Sea–a review. Frontiers in marine science 2020, 7, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).