1. Introduction

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have emerged as a highly relevant tool in modern nanomedicine due to their unique properties, including high antimicrobial activity, cellular penetration, and versatility in diagnostic and therapeutic applications [

1,

2]. Despite these benefits, concerns about their safety and potential toxic effects have prompted extensive research to understand how physicochemical characteristics—such as size, shape, surface charge, and the reducing agent used during synthesis—influence their biocompatibility [

3,

4].

The synthesis of AgNPs is commonly achieved through chemical reduction methods, with diverse reducing agents, such as sodium borohydride (NaBH₄) and sodium citrate (Na₃C₆H₅O₇), which are the most used in industrial and laboratory settings. Sodium borohydride enables the rapid reduction of silver ions, resulting in small and well-defined nanoparticles. Sodium citrate serves as both a reducing and stabilizing agent, a technique commonly employed in the classic Turkevich method adapted for AgNPs synthesis [

5,

6]. These conventional methods are highly effective and reproducible, but often involve toxic or environmentally harmful chemicals, raising concerns about the biocompatibility and ecological impact of the resulting nanoparticles [

7,

8].

As an alternative, green synthesis approaches have emerged, utilizing natural, biocompatible reducing and capping agents such as plant extracts, polysaccharides, and simple sugars, as glucose (GLU). Glucose is particularly attractive due to its natural abundance, metabolic compatibility, and low cytotoxicity, making GLU-capped AgNPs promising candidates for biomedical applications. In contrast, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-capped AgNPs represent one of the most widely used formulations in oncological nanomedicine research owing to their excellent colloidal stability and well-established synthesis protocols [

8,

9]. Whereas, PVP is a synthetic, non-biodegradable polymer that can persist in biological systems. It has been shown to alter protein corona formation, cellular uptake, and inflammatory responses—factors that may compromise therapeutic efficacy or safety [

9,

10]. Therefore, directly comparing GLU-AgNPs with PVP-AgNPs allows us to evaluate whether a green, metabolizable capping agent can provide comparable or superior biocompatibility and anticancer activity while avoiding the potential drawbacks of synthetic stabilizers.

In medicine, AgNPs have been widely explored for diverse applications, including antimicrobial coatings, wound healing, imaging, and targeted drug delivery [

11]. Notably, their potential as anticancer agents has attracted significant research interest due to their ability to induce oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA damage, and apoptosis in cancer cells while sparing normal cells under controlled conditions [

5]. Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of AgNPs against various types of cancer, including leukemia cells [

10]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that AgNPs synthesized with multiple reducing agents can induce cytotoxicity, promote the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and induce apoptosis [

10,

12].

These findings suggest that AgNPs could serve as an adjuvant or alternative therapeutic agent in leukemia treatment, particularly by enhancing the selectivity and efficacy of conventional therapies while reducing systemic toxicity [

10]. Ongoing research aims to optimize their targeting capacity, biocompatibility, and delivery mechanisms to harness their full potential in oncology.

The selection of appropriate model cells is crucial for assessing nanoparticle toxicity in both pathological and physiological contexts. JURKAT cell line, derived from human T lymphocytes, is frequently used as a model for leukemia studies, while peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) represent primary immune cells crucial to immune responses [

12]. Given their morphological similarities and functional relevance, these cells provide a suitable system to evaluate whether the choice of reducing agents influences differential cytotoxic responses between malignant and non-malignant immune cells [

12].

Previous studies have demonstrated that differences in nanoparticle surface chemistry can strongly influence their cellular uptake and cytotoxicity profiles [

13]. Understanding how synthesis parameters, particularly the nature of the reducing agent, affect the physicochemical characteristics and toxicity of nanoparticles is essential for developing safer and more effective nanostructures [

11]. Therefore, this work provides a comparison of AgNPs synthesized with GLU and PVP to evaluate the effects on leukemic and healthy cells. The results could offer insights to guide future studies and the design of nanoparticles to enhance therapeutic efficacy while reducing potential risks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The reagents required for the synthesis of the nanoparticles were silver nitrate (HyCel, cat. no. 5138601N15), molecular grade glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 50-99-7), gelatin (LABESSA, cat. no. GR2085), and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) (Sigma-Aldrich).

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs)

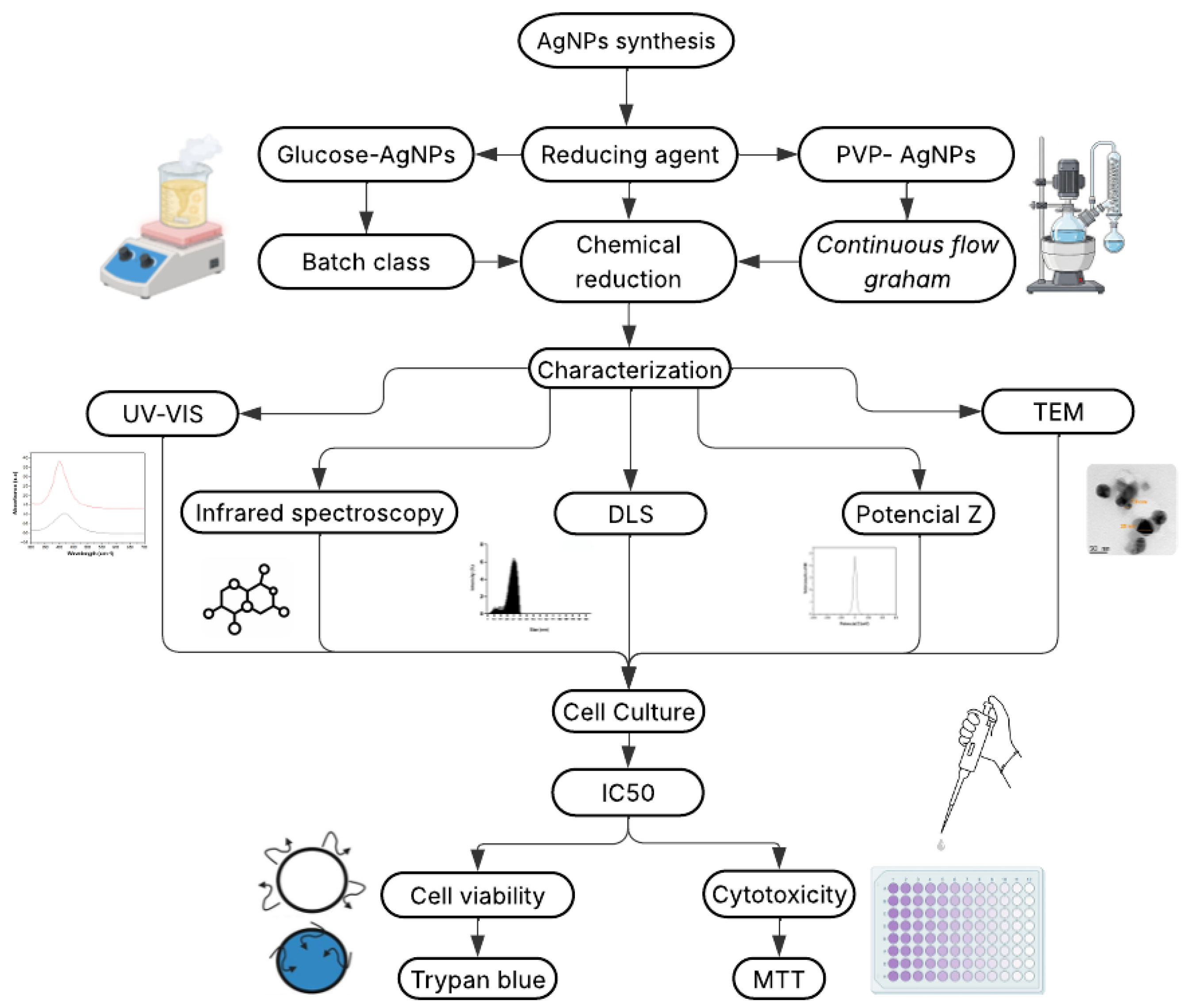

The AgNPs were synthesized using two different techniques, each employing a different reducing agent, under the same chemical method. The aim was to compare the influence of the synthesis route, particularly the type of reducing agent and the capping agent, on the physicochemical properties and biological activity of the resulting nanoparticles. An experimental schematic outlining the synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation workflow is included to illustrate the overall process (

Figure 1). The methods employed are described below.

2.2.1. GLU-AgNPs

The synthesis of AgNPs using GLU as a reducing agent (GLU-AgNPs) was performed using a previously reported chemical reduction method with slight variations [

28]. Initially, 100 mL of distilled water was heated to 85 °C, followed by the addition of 0.90 g of molecular-grade GLU and 0.36 g of gelatin as reducing agents. After achieving homogeneity, sodium hydroxide 0.1 M was added dropwise to reach a pH of 10. Subsequently, 10 mL of 0.1 M silver nitrate solution was added, and the mixture was stirred for 30 minutes at a stable temperature of 85 °C. After this time, the solution was allowed to cool to room temperature and stored in an amber bottle [

14].

2.2.2. PVP-AgNPs

The synthesis of PVP-AgNPs was prepared by the reflux method. A solution of 10 mL of 0.1 M silver nitrate in 100 ml of ethanol was prepared, and 1.00 g of PVP was added as a reducing and stabilizing agent, maintaining a silver nitrate to PVP weight ratio of 1:10. To obtain the PVP solution, ethanol and PVP were placed in a round-bottom flask and heated to 90 °C with slight stirring for 30 min. Afterwards, silver nitrate was added, and the mixture was stirred continuously for 7 h. The formation of PVP-AgNPs was visually confirmed by a color change in the solution, which turned amber due to the presence of AgNPs [

8].

2.2.3. Physicochemical and Morphological Characterization of AgNPs

The reduction of silver nitrate and the formation of AgNPs were monitored using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (

JASCO V-770 UV-VIS/NIR) from 200 to 800 nm. The spectra were recorded to identify the characteristic localized surface plasmon resonance peak of AgNPs. The synthesis conditions were optimized by preparing AgNPs at different concentrations of the reducing agent [

15].

The functional groups presented in GLU-AgNPs and PVP-AgNPs were identified using Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. FTIR spectra were recorded to analyze the chemical interactions and stabilizing agents involved in the synthesis process, with samples analyzed in suspension at room temperature [

20]. The FTIR spectra were collected at a resolution of 4 cm

−1 in transmission mode (4000–400 cm

−1) using a Bruker Alpha II spectrophotometer (Bruker Optics GmbH & Co. KG). The spectra were plotted using Origin Pro 2019 software.

The size and morphology of AgNPs were characterized by TEM (JEOL, JEM2011) at an accelerating voltage of 120 kV. A 5 μL suspension of AgNPs was spotted onto carbon-coated copper grids, followed by drying in a silica-based desiccator for 16 h. TEM images were acquired to confirm the shape, size, and distribution of AgNPs synthesized with GLU and PVP. Size distribution histograms were generated from TEM images using ImageJ software [

16].

Furthermore, dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements were performed to assess the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI) of AgNPs. The PDI is a dimensionless parameter that reflects the breadth of the particle size distribution, where values ≤0.1 indicate a highly monodisperse sample, 0.1–0.25 a moderately monodisperse system, and >0.3 a polydisperse population. These measurements, along with zeta potential and conductivity (determined using the same nanoparticle analyzer, Litesizer 500, at 173° and 25 °C), provided insights into the colloidal stability and physicochemical surface characteristics of the nanoparticles in suspension [

15,

17].

2.3. Cell Culture and Treatment Conditions

The JURKAT cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). JURKAT is an immortalized human T lymphocyte cell line derived from the peripheral blood of a 14-year-old male patient with acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. PBMCs were isolated from peripheral whole blood obtained from a healthy 19-year-old donor by density gradient centrifugation using Lymphoprep™ (Serumwerk Bernburg AG, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Blood was carefully layered over Lymphoprep™ at a 3:1 ratio (blood:Lymphoprep) and centrifuged at 1800 rpm for 30 min at room temperature without brake. The PBMC layer at the interface was collected and washed three times with PBS (300 × g, 5 min). Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion (>95%). JURKAT cells were maintained by passaging every 2–3 days [

18].

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Biosafety and Ethics Committees of the Centro Universitario de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad de Guadalajara (protocol CI-06422).

Cell cultures were maintained in RPMI-1640 (Thermo Fisher) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher) at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ and 95% humidity. Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 10⁴ cells/mL in 96-well plates and exposed to AgNPs at 6, 3, 1.5, 0.75, and 0.37 µg/mL for 24 h. Untreated cells and cells treated with etoposide served as negative and positive controls, respectively. All experiments were conducted in triplicate

2.7. Cell Viability Assay, IC50, and Selectivity Index

Cell viability in JURKAT cells was assessed using the trypan blue exclusion assay. Cells were treated with GLU-AgNPs and PVP-AgNPs at concentrations of 0.37, 1.5, 3, and 6 µg/mL and incubated for 24 h. After treatment, cells were stained with 0.4% trypan blue dye, and the percentage of viable cells was determined by counting the total number of cells and excluding those stained under an optical microscope using a Neubauer chamber [

19]. The same treatment and analysis were performed in PBMCs for comparative cytotoxicity assessment. The IC₅₀ values were determined from cell viability assays performed in triplicate. Dose–response curves were generated using four concentrations of AgNPs (0.37, 1.5, 3, and 6 µg/mL) after 24 h of incubation. Concentration values were log-transformed for curve fitting, and the resulting IC₅₀ values are reported in µg/mL. The selectivity index (SI) was calculated as the ratio between the IC₅₀ value obtained in normal PBMCs and the IC₅₀ value obtained in leukemic cells (SI = IC₅₀₍PBMC₎ / IC₅₀₍Leukemia₎). An SI value > 1 was considered indicative of selective cytotoxicity toward cancer cells.

2.8. Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of each AgNPs was evaluated using the MTT assay. AgNPs were added to the wells at concentrations of 0.75, 1.5, 3, and 6 µg/mL, and the cells were incubated for 24 hours. A MTT solution was prepared by dissolving 5 mg of MTT in 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 10 µL of this solution was added to each well. The plate was incubated for 4 h to allow the formation of formazan crystals. Subsequently, 100 µL of extraction buffer using sodium dodecyl sulfate (28312 Thermo Fisher ScientificTM Waltham, MA; USA) and dimethylformamide (227056 Sigma AldrichTM, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to dissolve the formazan crystals, and the plate was further incubated for 18 hours. Finally, absorbance was measured in a spectrophotometer at 570 nm (BioTek® 800™). Given that residual glucose in GLU-AgNPs samples can interfere with the absorbance reading, a background correction was performed at 490 nm for those samples.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Dose-response curves were generated, and the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) values were determined by nonlinear regression analysis using a four-parameter logistic (4PL) model (log[inhibitor] vs. response — variable slope) in GraphPad Prism software, with concentrations analyzed on a logarithmic scale to account for the wide range of tested values. Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Quantitative variables—including IC₅₀ values and the characterization data of AgNPs—were described as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between two groups were made using the unpaired Student’s t-test, while one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used for three or more groups. When data did not meet parametric assumptions, non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis) were applied. Qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages; comparisons were performed using the Chi-square (χ²) test or Fisher’s exact test when expected cell counts were < 5. All analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism v8 or R 2024.12.1+563, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed unless stated otherwise). Experiments were repeated in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles

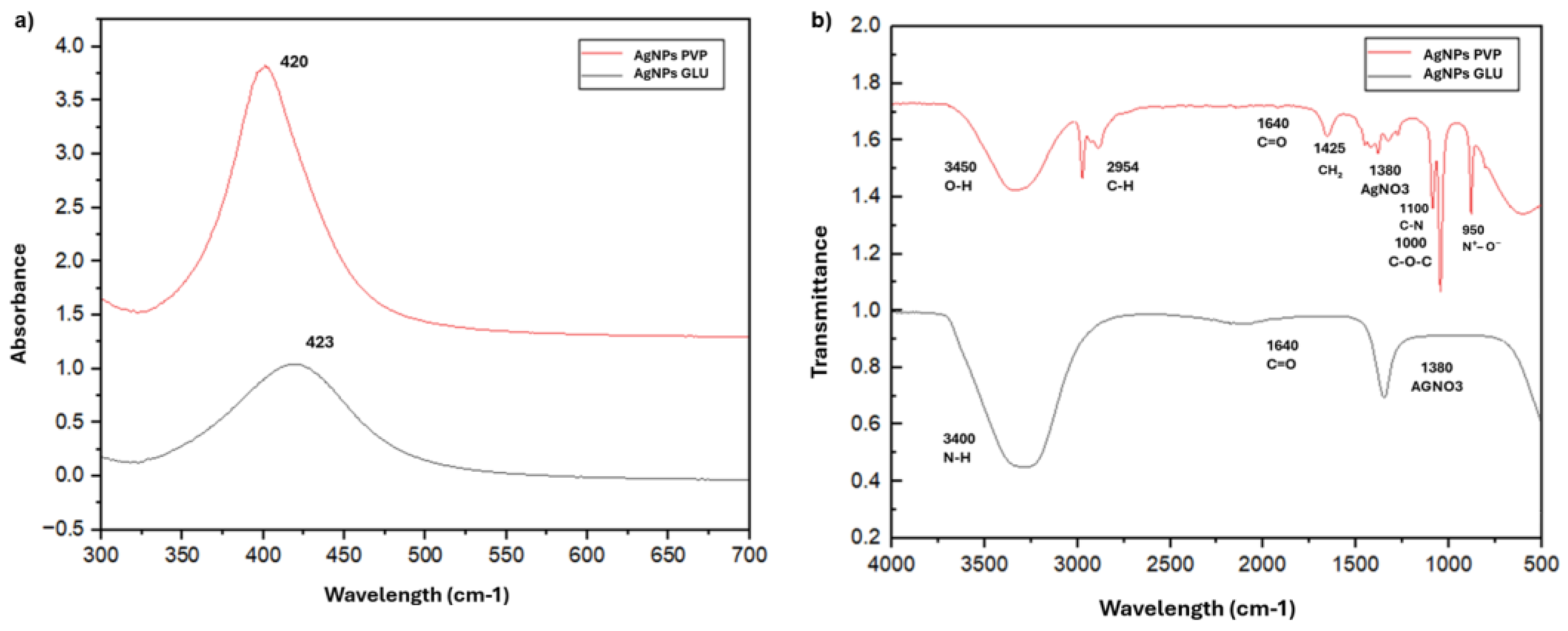

According to the UV-Vis absorption spectra (

Figure 2a), the synthesized AgNPs exhibited surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peaks at 423 nm for GLU-AgNPs and 420 nm for PVP-AgNPs, confirming their formation. The slightly higher absorbance intensity observed for PVP-AgNPs may reflect differences in particle concentration, size distribution, or aggregation state compared to GLU-AgNPs.

FTIR analysis (

Figure 2b) revealed distinct surface functional groups associated with each capping agent. Both NPs showed a band at ~1380 cm⁻¹, assigned to residual nitrate (NO₃⁻) from unreacted silver nitrate, rather than to AgNO₃ as a functional moiety. In GLU-AgNPs, characteristic bands were observed at 3417 cm⁻¹ (O–H stretching from hydroxyl groups of glucose and/or gelatin), 1640 cm⁻¹ (C=O stretching, possibly from carboxylate or amide I if gelatin is present), and 1050 cm⁻¹ (C–O stretching, typical of carbohydrates). These oxygen-rich groups likely contribute to nanoparticle stabilization through hydrogen bonding and steric effects. For PVP-AgNPs, the spectrum displayed bands at 3448 cm⁻¹ (O–H, adsorbed water), 2954 cm⁻¹ (C–H aliphatic), 1640 cm⁻¹ (C=O of pyrrolidone ring), 1425 cm⁻¹ (CH₂ bending / C–N), 1000 cm⁻¹ (C–O–C), along with additional features at 3050 cm⁻¹ (C=C–H, alkene) and 950 cm⁻¹ (N⁺–O⁻, amine oxide), consistent with PVP’s structure and partial oxidation during synthesis. These nitrogen- and oxygen-containing groups enhance colloidal stability via steric hindrance and surface coordination.

Regarding colloidal properties (

Table 1), PVP-AgNPs exhibited a hydrodynamic diameter of 30.0 ± 1.8 nm (PDI = 0.280), while GLU-AgNPs were smaller (22.4 ± 1.2 nm, PDI = 0.232). Zeta potential values were –10.01 ± 1.8 mV for PVP-AgNPs and –3.5 ± 1.2 mV for GLU-AgNPs, with conductivities of 0.163 mS/cm and 0.179 mS/cm, respectively.

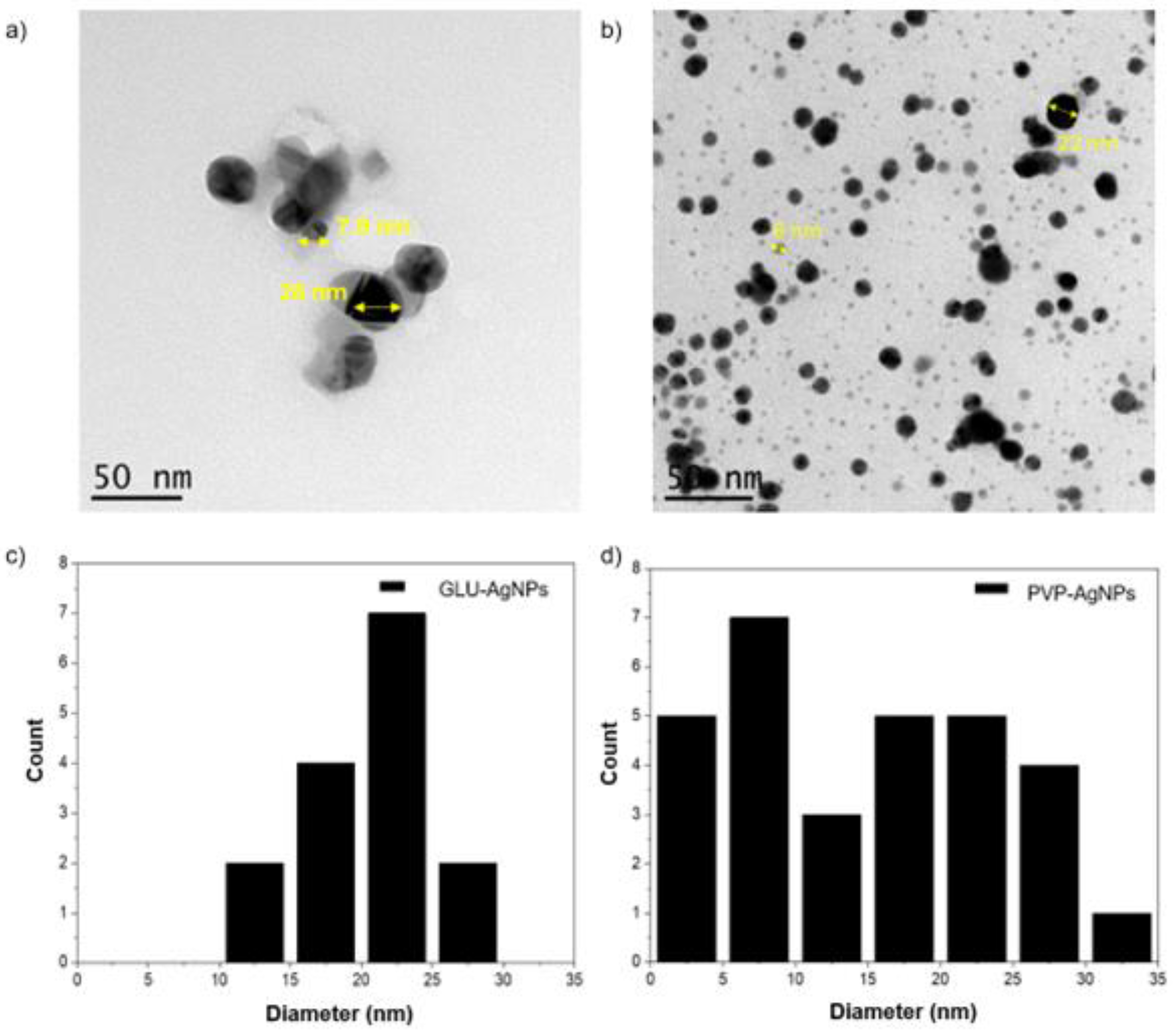

TEM analysis revealed some differences between the AgNPs (

Figure 3). For GLU-AgNPs, most particles were within the size of 7.9 - 28 nm, exhibiting slight irregularities in shape and rougher surfaces. Whereas, PVP-AgNPs displayed predominantly spherical structures with two distinct size populations, averaging 6 - 22 nm, respectively. These particles were well-dispersed with smooth surfaces and minimal aggregation, as evidenced by the TEM images. The size distribution histogram of PVP-AgNPs also showed two prominent peaks at 6 nm and 22 nm, reflecting the bimodal size distribution observed in the synthesis process.

3.2. Cell Viability and IC50

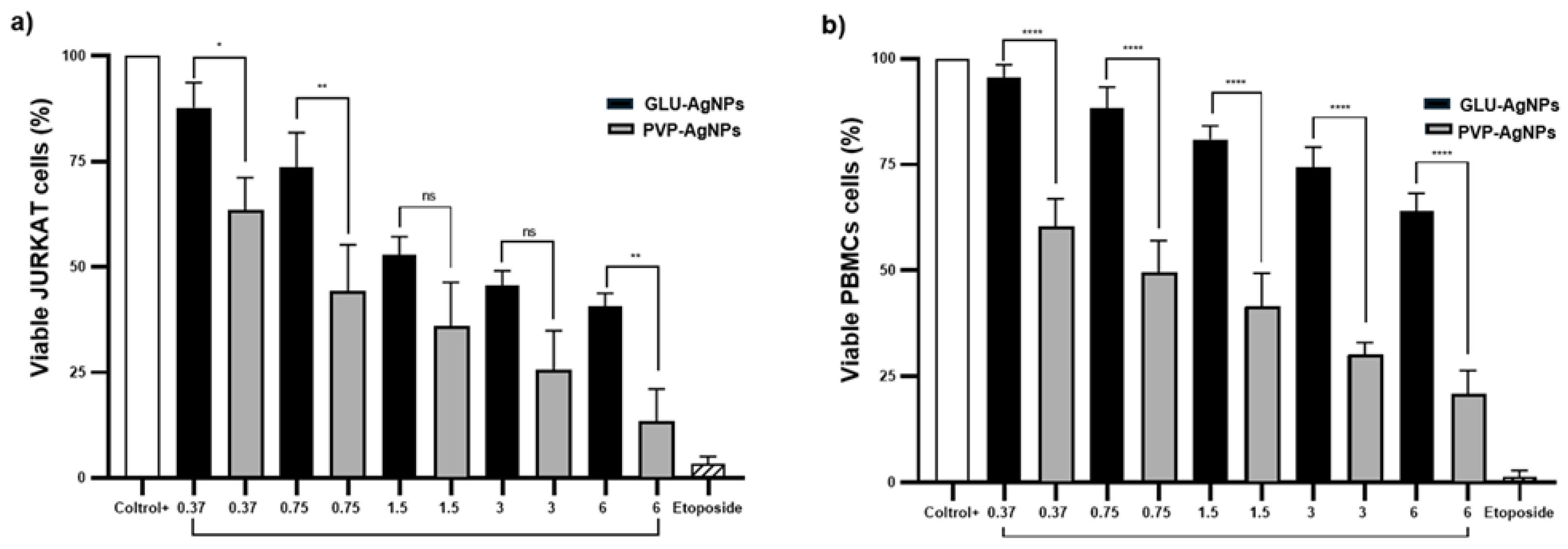

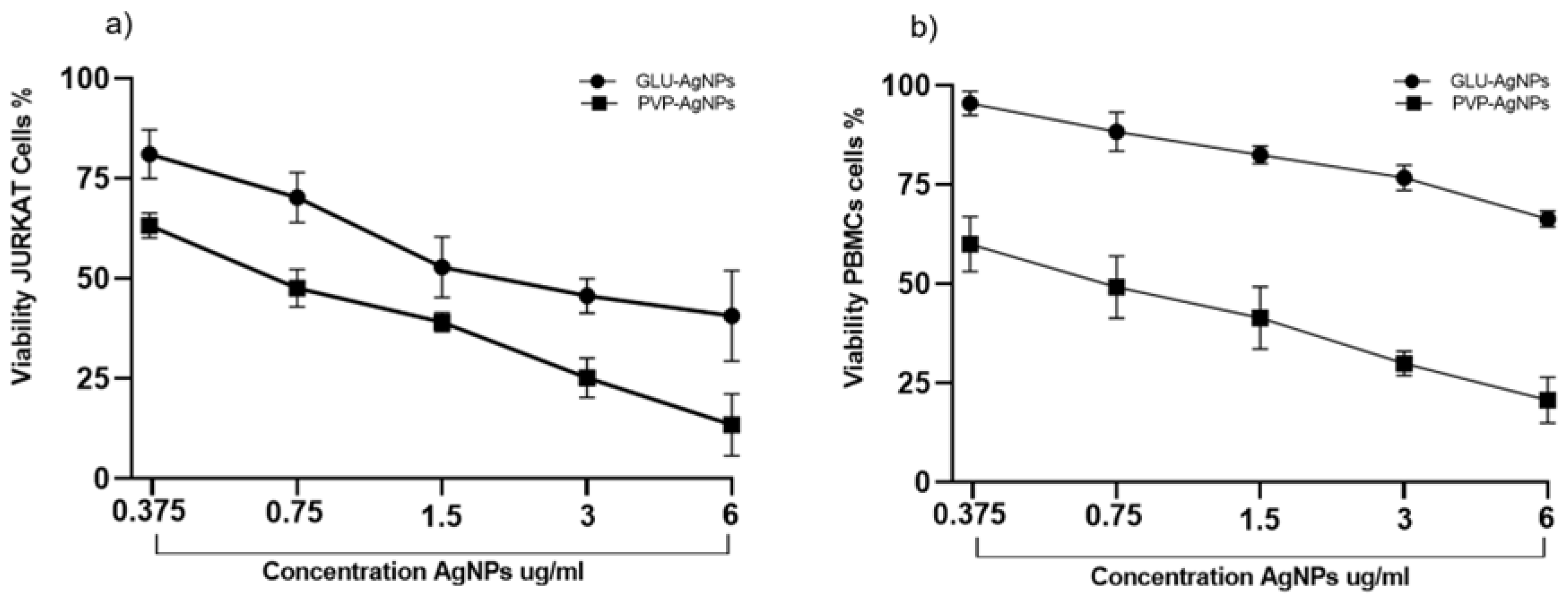

A dose-dependent decrease in cell viability was observed for both GLU-AgNPs and PVP-AgNPs in JURKAT cells and PBMCs (

Figure 4). In JURKAT cells, PVP-AgNPs induced a significantly sharper reduction in viability compared to GLU-AgNPs. Viability decreased from 85% at 0.37 µg/mL to 15% at 6 µg/mL for PVP-AgNPs, whereas GLU-AgNPs produced a more moderate decrease, from 90% to approximately 40% across the same concentration range (p < 0.001) (

Figure 4a).

In PBMCs, GLU-AgNPs preserved viability above 60% at 6 µg/mL, while PVP-AgNPs reduced viability to approximately 20% at the same concentration (p < 0.001) (

Figure 4b). These results indicate that GLU-AgNPs exert lower cytotoxicity toward healthy immune cells than PVP-AgNPs.

Dose–response curves were used to determine the IC₅₀ values for each nanoparticle (

Figure 5). In JURKAT cells, PVP-AgNPs showed a lower IC₅₀ (0.85 µg/mL) compared to GLU-AgNPs (2.83 µg/mL), indicating greater cytotoxic potency. In PBMCs, GLU-AgNPs exhibited an IC₅₀ of 6.9 µg/mL, whereas PVP-AgNPs demonstrated a substantially lower IC₅₀ (0.30 µg/mL), reflecting a higher toxicity toward healthy cells.

Selectivity was assessed using the Selectivity Index (SI), calculated as IC₅₀ in PBMCs divided by IC₅₀ in JURKAT cells (

Table 2). GLU-AgNPs yielded an SI of 2.44, indicating selective toxicity toward leukemic cells while sparing PBMCs. Conversely, PVP-AgNPs presented an SI of 0.36, demonstrating non-selective cytotoxicity, with greater toxicity toward healthy immune cells.

3.3. Cytotoxicity in JURKAT and PBMCs Stimulated with GLU-AgNPs and PVP-AgNPs

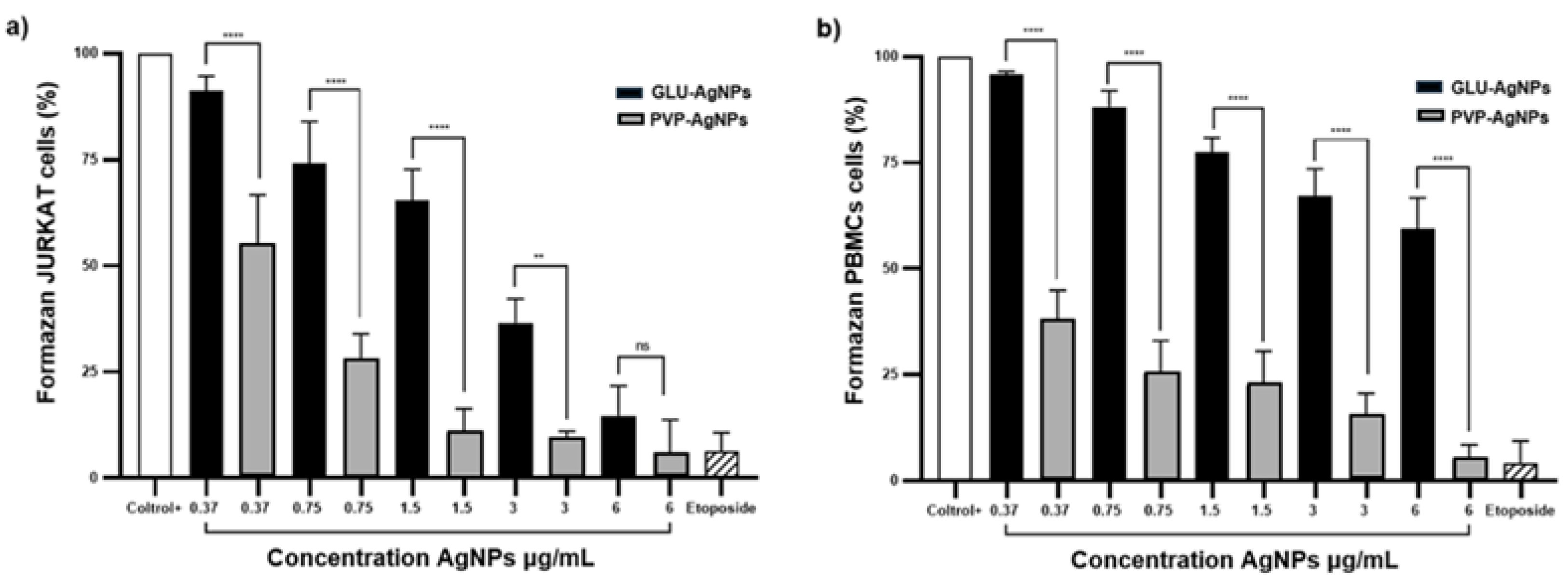

Cytotoxicity in JURKAT and PBMCs stimulated with GLU-AgNPs and PVP-AgNPs was dose-dependent, as evidenced by the metabolic activity evaluated through the MTT assay. In JURKAT cells (

Figure 6a), metabolic activity decreased from 91.1% to 14.7% when treated with concentrations ranging from 0.37 µg/mL to 6 µg/mL of GLU-AgNPs, indicating significant impairment of mitochondrial function in leukemic cells. This decrease aligns with the previously calculated IC₅₀ of 6.9 µg/mL, supporting that GLU-AgNPs require comparatively higher concentrations to induce a half-maximal cytotoxic effect on malignant cells, highlighting a moderated cytotoxic potency. In contrast, PBMCs (

Figure 6b) exhibited a milder response, with metabolic activity decreasing from 95.9% to 59.4% across the same concentration range. The IC₅₀ value in PBMCs remained above the highest tested concentration, suggesting lower sensitivity and indicating a degree of selectivity toward cancer cells. On the other hand, PVP-AgNPs displayed stronger and non-selective cytotoxicity. In JURKAT cells, viability dropped sharply from 54.9% to 6.0%, while in PBMCs, survival decreased from 38.2% to 5.0%. This corresponds with the lower IC₅₀ previously calculated for PVP-AgNPs (0.30 µg/mL), demonstrating high cytotoxic potency, but without selectivity, since similar toxicity was observed in both malignant and healthy cells.

4. Discussion

In recent years, the use of AgNPs as novel therapeutic and immunomodulatory agents has attracted considerable attention from the scientific community, particularly those synthesized using naturally occurring, biocompatible, and environmentally friendly reducing and capping agents. For instance, AgNPs synthesized using

Achillea millefolium extract showed selective cytotoxicity against lymphoblastic leukemia cells (MOLT-4) [

10]. In the context of leukemia, AgNPs have demonstrated promising results in inducing cell death in both myeloid (e.g., HL-60) and lymphoid (e.g., JURKAT) leukemia cell lines. For example, green-synthesized AgNPs from

Ziziphora tenuior extract were reported to trigger caspase-dependent apoptosis in HL-60 cells through the generation of ROS [

21].

In our study, AgNPs synthesized via chemical reduction with GLU as the reducing agent were successfully obtained under various experimental conditions. UV-Vis spectroscopy revealed LSPR peaks at 423 nm for GLU-AgNPs and 420 nm for PVP-AgNPs, both falling within the typical range for spherical silver nanoparticles (400–430 nm) [

7,

22,

23]. The slight red shift in GLU-AgNPs and their narrower absorption band—compared to the broader peak of PVP-AgNPs—suggests differences in particle size distribution, shape homogeneity, and surface capping. The broader SPR band of PVP-AgNPs indicates greater heterogeneity in size and morphology, which is consistent with the TEM analysis described below. This observation aligns with established principles in nanoplasmonics, where the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the SPR band is directly influenced by nanoparticle polydispersity and surface roughness [

21]. These findings are consistent with those of Aguilar-Méndez

et al. (2010), who reported LSPR peaks at 420–423 nm for AgNPs synthesized under similar conditions [

18].

In addition to optical properties, FTIR confirmed the presence of distinct functional groups associated with each capping agent, reinforcing the idea that the type of reducing and stabilizing molecules directly affects the surface chemistry of the nanoparticles. For GLU-AgNPs, characteristic absorption bands at 3417 cm⁻¹ (O–H and N–H stretching) and 1648 cm⁻¹ (C=O in amide I) indicated the successful interaction between GLU and the nanoparticle surface, suggesting a more biocompatible profile [

14]. For PVP-AgNPs, key peaks appeared at 1654 cm⁻¹ (C=O stretching in pyrrolidone group), 2954 cm⁻¹ (CH stretching), and 3448 cm⁻¹ (OH stretching), which are indicative of PVP stabilization on the nanoparticle surface [

7,

21].

Zeta potential analysis showed values of -2.5 mV for GLU-AgNPs and -10.01 mV for PVP-AgNPs, suggesting lower colloidal stability, although both types remain relatively stable in suspension [

21]. According to the colloidal stability theory and numerous experimental reports, values exceeding ± 30 mV are generally associated with enhanced colloidal stability; however, other factors such as particle size and the nature of capping agents may compensate for lower zeta potential values [

21]. In this context, the comparatively higher stability observed for GLU-reduced nanostructures, reflected by their lower PDI, can be attributed to the ability of gelatin to form a steric protective layer around the nanoparticle surface, preventing aggregation. DLS and TEM analyses confirmed that GLU-AgNPs exhibited predominantly spherical shapes and a relatively uniform morphology, with particle sizes ranging from 6 to 28 nm [

14]. These structural and colloidal characteristics are closely associated with their subsequent biological responses, as evidenced in the following cell viability assays [

7].

Regarding the effect of the reducing agent on cell viability, GLU-AgNPs induced a gradual decrease in cell viability, whereas PVP-AgNPs caused a more abrupt drop even at low concentrations, particularly in JURKAT cells. This finding supports the idea that the type of reducing agent, as well as the surface coating, directly influences nanoparticle–cell interactions [

7,

24].

These results confirm that PVP-AgNPs are significantly more cytotoxic and less selective than GLU-AgNPs.

This differential response is quantitatively captured by the selectivity index (SI), calculated as the ratio of IC₅₀ in PBMCs to IC₅₀ in JURKAT cells. GLU-AgNPs exhibited an SI of 2.439, indicating a >2-fold higher concentration is required to elicit toxicity in healthy cells—a profile consistent with a favorable therapeutic window [

7,

24]. In contrast, PVP-AgNPs yielded an SI of 0.361, confirming their inverted selectivity (greater toxicity toward normal cells than cancer cells) and limited suitability for targeted therapy [

13].

This selectivity likely stems from metabolic differences between malignant and normal immune cells. Leukemic cells, including JURKAT, exhibit heightened glucose uptake due to overexpression of glucose transporters (e.g., GLUT1) a hallmark of cancer metabolism—which may facilitate preferential internalization of GLU-AgNPs. In contrast, PBMCs, as quiescent primary cells, show lower metabolic activity and reduced endocytic capacity, limiting nanoparticle uptake and cytotoxicity. Conversely, the synthetic PVP corona may promote non-specific cellular interactions, leading to indiscriminate toxicity in both cell types [

25,

26].

Previous studies have shown that surface functionalization can be strategically used to design AgNPs with tunable therapeutic profiles either aggressive or biocompatible depending on the clinical context [

7,

27]. Our findings position GLU-AgNPs as a promising candidate for safer anticancer applications where immune cell preservation is critical.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the reducing agent used in the synthesis of AgNPs has a significant impact on their biological behavior. PVP-AgNPs are more cytotoxic and less selective, whereas GLU-AgNPs appear to have a safer profile, with fewer effects on healthy cells (PBMCs). While these characteristics might favor the use of GLU-AgNPs in clinical settings, further in vivo studies and investigations into cellular internalization mechanisms are needed to validate their safe and effective use. Moreover, it would be interesting to explore their long-term effects, combined with anti-leukemic drugs, or in three-dimensional models of lymphoid tissue [

24,

28].

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the reducing agent used during the synthesis of AgNPs significantly influences their physicochemical properties and interactions with leukemic and healthy cells. GLU-AgNPs exhibited higher colloidal stability and a less pronounced cytotoxic profile, resulting in higher cell viability and a favorable selectivity index (SI = 2.439) toward leukemic cells. Whereas PVP-AgNPs showed a slightly higher polydispersity (i.e., a bimodal size distribution profile) and a more negative zeta potential, which likely facilitated their cellular uptake, resulting in a stronger cytotoxic effect on leukemic cells and lower cell viability compared to GLU-AgNPs. These findings confirm that the chemical nature of the reducing agent and the capping layer formed during synthesis not only affect the physicochemical characteristics and colloidal behavior of AgNPs but also modulate the biological response of exposed cells.

Overall, this work underscores the importance of nanoparticle design as a strategic tool to tailor their biological performance. The choice of reducing agent emerges as a key factor in the development of oncological nanomedicine, although further in vivo studies and mechanistic investigations are needed to fully assess its implications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.M.S. and J.G.A.L.; methodology, J.G.A.L., B.C.S.R, A.T.C, E.E.P.G., M.S.R.; software, E.E.P.G. and M.S.R.; validation, A.C.M.S. and J.G.A.L, PESH, TGI.; formal analysis, J.G.A.L. and A.C.M.-S.; investigation, J.G.A.L., B.C.S.R., A.T.C, E.E.P.G., M.S.R.; resources, A.C.M.S.; data curation, J.G.A.L. and A.C.M.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.A.L. and A.C.M.S.; writing—review and editing, A.C.M.S., B.C.S.R., A.T, P.E.S.H, T.G.I.; visualization, J.G.A.L. and E.E.P.G.; supervision, A.C.M.S, P.E.S.H., TGI.; project administration, A.C.M.S.; funding acquisition, A.C.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the PRO-SNI 2022, PROINPEP 2023, and PIN 2022-III programs of the Centro Universitario de Ciencias de la Salud (CUCS), Universidad de Guadalajara, México. The PIN 2022-III grant was awarded to Andrea Carolina Machado Sulbaran. J.G.A.-L. received a doctoral scholarship from SECIHTI (Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación, México).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials .

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Childhood and Adolescent Cancer Research Institute (INICIA) (CUCS) and the Bioprocess Laboratory of the Renewable Energy Laboratory (CUTonalá) for providing reagents and technical support—special thanks to the healthy donor and his legal guardian for their voluntary participation. We also thank undergraduate student Álvaro Salazar Loera.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest for any of the authors and contributors. The funders did not participate in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, manuscript writing, or decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| AgNPs |

Silver Nanoparticles |

| GLU |

Glucose |

| PVP |

Polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| PBMCs |

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| SPR |

Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| FTIR |

Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| TEM |

Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| DLS |

Dynamic Light Scattering |

| MTT |

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| IC₅₀ |

Half-maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| SI |

Selectivity Index |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| CUCS |

Centro Universitario de Ciencias de la Salud |

| INICIA |

Instituto de Investigación en Cáncer en la Infancia y Adolescencia |

| IICB |

Instituto de Investigación en Ciencias Biomédicas |

References

- Ahamed M, Alsalhi MS, Siddiqui MKJ. Silver nanoparticle applications and human health. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411(23-24):1841–8.

- Ávalos A, Haza AI, Morales P. Nanopartículas de plata: Aplicaciones y riesgos tóxicos para la salud humana y el medio ambiente. Rev Complutense Cienc Veterinarias. 2013;7(2). [CrossRef]

- Choudhary A, Singh S, Ravichandiran V. Toxicity, preparation methods and applications of silver nanoparticles: An update. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2022;1–12. [CrossRef]

- Horie M, Kato H, Fujita K, Endoh S, Iwahashi H. In vitro evaluation of cellular response induced by manufactured nanoparticles. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;25(3):605–19. [CrossRef]

- J. Turkevich, P. C. Stevenson, and J. Hillier, “A study of the nucleation and growth processes in the synthesis of colloidal gold,” Discussions of the Faraday Society, vol. 11. 1951.

- Eom HJ, Choi J. p38 MAPK activation, DNA damage, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis as mechanisms of toxicity of silver nanoparticles in JURKAT T cells. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(21):8337–42. [CrossRef]

- Rónavári A, Bélteky P, Boka E, Zakupszky D, Igaz N, Szerencsés B, et al. Polyvinyl-pyrrolidone-coated silver nanoparticles—The colloidal, chemical, and biological consequences of steric stabilization under biorelevant conditions. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(16):8673. [CrossRef]

- Ibarra Hurtado JM, Virgen Ortiz A, Irebe A, Luna Velasco A. Control and stabilization of silver nanoparticles size using polyvinylpyrrolidone at room temperature. Digest J Nanomater Biostruct. 2014;9(2):493–501.

- Sulaiman GM, Mohammed WH, Marzoog TR, Al-Amiery AA, Kadhum AA, Mohamad AB. Green synthesis, antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects of silver nanoparticles using Eucalyptus chapmaniana leaves extract. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2013;3(1):58–63. [CrossRef]

- Karimi S, Mahdavi Shahri M. Medical and cytotoxicity effects of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Achillea millefolium extract on MOLT-4 lymphoblastic leukemia cell line. J Med Virol. 2021;93(6):3899–906. [CrossRef]

- Zhang RX, Wong HL, Xue HY, Eoh JY, Wu XY. Nanomedicine of synergistic drug combinations for cancer therapy – strategies and perspectives. J Control Release. 2016; 240:489–503. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Morales S, Hidalgo-Miranda A, Ramírez-Bello J. Leucemia linfoblástica aguda infantil: Una aproximación genómica. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2017;74(1):13–26. [CrossRef]

- Greulich, C., Diendorf, J., Geßmann, J., Simon, T., Habijan, T., Eggeler, G., Schildhauer, T., Epple, M., & Köller, M. (2011). Cell type-specific responses of peripheral blood mononuclear cells to silver nanoparticles. Acta Biomaterialia, 7(9), 3505-3514. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Méndez, M. A., Martín-Martínez, E. S., Ortega-Arroyo, L., Cobián-Portillo, G., & Sánchez-Espíndola, E. (2010). Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles: effect on phytopathogen Colletotrichum gloesporioides. Journal Of Nanoparticle Research, 13(6), 2525-2532. [CrossRef]

- Mettler-Toledo International Inc. Espectroscopia Ultravioleta-Visible: Conceptos Básicos [Internet]. 2022 Nov 10 [citado 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.mt.com/mx/es/home/applications/application_browse_laboratory_analytics/uv-vis-spectroscopy/uvvis-spectroscopy-explained.html.

- Jara N, Milán NS, Rahman A, Mouheb L, Boffito DC, Jeffryes C, Dahoumane SA. Photochemical synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles—A review. Molecules. 2021;26(15):4585. [CrossRef]

- Malvern. Zeta potential - An introduction in 30 minutes [Internet]. 2015 [citado 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.research.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/ZetaPotential-Introduction-in-30min-Malvern.pdf.

- Terwilliger T, Abdul-Hay M. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A comprehensive review and 2017 update. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7(6):e577. [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan S, Qasim M, Park C, Yoo H, Choi DY, Song H, et al. Cytotoxicity and Transcriptomic Analysis of Silver Nanoparticles in Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(11):3618. [CrossRef]

- L.A. Laime-Oviedo, Soncco-Ccahui, A.A., Peralta-Alarcon, G., Arenas-Chávez, C.A., Pineda-Tapia, J.L., Díaz-Rosado, J.C., Alvarez-Risco, A., Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S., Davies, N.M., and Yáñez, J., Optimization of Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Conjugated with Lepechinia meyenii (Salvia) Using Plackett-Burman Design and Response Surface Methodology—Preliminary Antibacterial Activity. Processes. 10 (2022) 1727. [CrossRef]

- García-Contreras R, Costa-Torres MC, Arenas-Arrocena MC, Rodríguez Torres MP. Manual para la enseñanza práctica del ensayo MTT para evaluar la citotoxicidad de nanopartículas. ResearchGate, 2019.

- Verma G, Mishra M. Development and optimization of UV-VIS spectroscopy, a review. Shri Guru Ram Rai Inst Technol Sci Dehradun UK. 2018;7(11):1170–80.

- García-Contreras R, Costa-Torres MC, Arenas-Arrocena MC, Rodríguez Torres MP. Manual para la enseñanza práctica del ensayo MTT para evaluar la citotoxicidad de nanopartículas. ResearchGate, 2019.

- Gurunathan S, Qasim M, Park C, Yoo H, Choi DY, Song H, et al. Cytotoxicity and transcriptomic analysis of silver nanoparticles in mouse embryonic fibroblast cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(11):3618. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. , Liu, Z., Shen, W., & Gurunathan, S. (2016). Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, Properties, Applications, and Therapeutic Approaches. International Journal Of Molecular Sciences, 17(9), 1534. [CrossRef]

- Nymark P, Catalán J, Suhonen S, Järventaus H, Birkedal RK, Clausen PA, et al. Genotoxicity of polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated silver nanoparticles in BEAS 2B cells. Toxicology. 2013;313(1):38–48. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H., Pujari, G., Sarma, A., Mishra, Y. K., Jin, M. K., Nirala, B. K., Gohil, N. K., Adelung, R., & Avasthi, D. K. (2013). Study Of In Vitro Toxicity Of Glucose Capped Gold nanoparticles In Malignant And Normal Cell Lines. Advanced Materials Letters, 4(12), 888-894. [CrossRef]

- Tatar AS, Nagy-Simon T, Tomuleasa C, Boca S, Astilean S. Nanomedicine approaches in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Control Release. 2016;238:123–38. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).