Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

12 November 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Test Samples

2.3. Test Method

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zenkert, D. An Introduction to Sandwich Structures, 2nd ed.; Dan Zenkert: Stockholm, Sweden, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, P.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pu, L. Wood-based sandwich panels: A review. Wood Res. 2021, 66, 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais-Moleman, A.L.; Sikkema, R.; Vis, M.; Reumerman, P.; Theurl, M.C.; Erb, K.-H. Assessing wood use efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions of wood product cascading in the European Union. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3942–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myllyviita, T.; Soimakallio, S.; Judl, J.; Seppälä, J. Wood substitution potential in greenhouse gas emission reduction Review on current state and application of displacement factors. For. Ecosyst. 2021, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smardzewski, J. Experimental and numerical analysis of wooden sandwich panels with an auxetic core and oval cells. Mater. Des. 2019, 183, 108159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakreb, N.; Bezzazi, B.; Pereira, H. Mechanical behavior of multilayered sandwich panels of wood veneer and a core of cork agglomerates. Mater. Des. (1980–2015) 2015, 65, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smardzewski, J.; Krzyz˙aniak, Ł.; Wojciechowski, K.W.; Pelin´ski, K.; Tretiakov, K.V.; Narojczyk, J.W. Bending performance and failure behavior of wooden sandwich panels with corrugated cores. Phys. Status Solidi B 2022, 259, 2200423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labans, E.; Kalnins, K. Experimental validation of the stiffness optimisation for plywood sandwich panels with rib-stiffened core. Wood Res. 2014, 59, 793–802. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, S.; Martins, J.; Magalhães, F.D.; Carvalho, L. Lightweight wood composites: Challenges, production and performance. In Lignocellulosic Composite Materials; Kalia, S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 293–322. ISBN 978-3-319-68696-7. [Google Scholar]

- Barbu, M.C.; Lüdtke, J.; Thömen, H.; Welling, J. Innovative production of wood-based lightweight panels. In Processing Technologies for the Forest and Biobased Products Industries; Barbu, M.C., Ed.; Salzburg University of Applied Sciences: Kuchl, Australia, 2010; pp. 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Cabo, J.L.; Majano-Majano, A.; San-Salvador Ageo, L.; Ávila-Nieto, M. Development of a novel façade sandwich panel with low-density wood fibres core and wood-based panels as faces. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2011, 69, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.M.; Shan, F.R.; Shang, J.B. Characteristic and prediction model of vertical density profile of fiberboard with fiberboard with “pretreatment-hot pressing” united technology. Wood Res. 2012, 57, 613–630. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Yan, N.; Deng, J.; Smith, G. Flexural creep behavior of sandwich panels containing kraft paper honeycomb core and wood composite skins. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 2011, 528, 5621–5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yan, N. Investigation of elastic moduli of kraft paper honeycomb core sandwich panels. Composites Part B 2012, 43, 2107–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labans, E.; Kalniņs, K. Experimental validation of the stiffness optimization for plywood sandwich panels with rib-stiffened core. Wood Res. 2014, 59, 793–802. [Google Scholar]

- Susainathan J, Eyma F, De Luycker E, Cantarel A, Castanié, B. Manufacturing and quasi-static bending behavior of wood-based sandwich structures. Compos. Struct. 2017, 182, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Hunt, J.F.; Gong, S.Q.; Cai, Z.Y. Simplified analytical model and balanced design approach for light-weight wood-based structural panel in bending. Compos. Struct. 2016, 136, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Hu, Y.; Wang, B. Compressive and bending behaviours of wood-based two-dimensional lattice truss core sandwich structures. Compos. Struct. 2015, 124, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, A.; Schwartz, J.; Boháček, Š.; Lübke, H.; Ihnát, V.; Pažitný, A. Reuse of old corrugated cardboard in constructional and thermal insulating boards. Wood Res. 2013, 58, 505–510. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken, A.; Sadeghian, P. Corrugated cardboard core sandwich beams with bio-based flax fiber composite skins. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 20, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadabadi, M. , Yadama, V. , Yao, L., Bhattacharyya, D., 2018: Low-velocity impact response of wood-strand sandwich panels and their components. Holzforschung 2018, 72, 681–689. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ramakrishnan, K.R.; Shankar, K. Experimental study of the medium velocity impact response of sandwich panels with different cores. Mater. Des. 2016, 99, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalsalm, S.O. Impact damage analysis of balsa wood sandwich composites Thesis USA: Wayne state university; 2013.

- Petit, S.; Bouvet, C.; Bergerot, A.; Barrau, J.J. Impact and compression after impact ex perimental study of a composite laminate with a cork thermal shield. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, 67, 3286–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Cho, S.H. An experimental study of low-velocity impact responses of sandwich panels for Korean low floor bus. Compos. Struct. 2008, 84, 228–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Shi, H.; Fang, H.; Liu, W.; Qi, Y.; Bai, Y. Fiber reinforced composites sandwich panels with web reinforced wood core for building floor applications. Composites, Part B 2018, 150, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgars, L.; Kaspars, Z.; Kaspars, K. Structural performance of wood based sandwich panels in four point bending. Procedia Engineering 2017, 172, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Fang, H.; Shi, H.; Liu, W.; Qi, Y.; Bai, Y. Bending performance of GFRP-wood sandwich beams with lattice-web reinforcement in flatwise and sidewise directions. Construct. Build. Mater. 2017, 156, 532–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiziroglu, S. Some properties of sandwich type composite panels manufactured from eastern redcedar. Composites Part B 2012, 43, 3288–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A. ; Zuccarello. B. Experimental and numerical evaluation of the mechanical behaviour of GFRP sandwich panels, Compos. Struct. 2007, 81, 575–586. [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Antwi, M.; de Castro, J.; Vassilopoulos, A.P.; Keller, T. Modeling of axial and shear stresses in multilayer sandwich beams with stiff core layers, Compos. Struct. 2014, 116, 453–460. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Lu, X.; N. ; Huang, X.J. Reinforcement of laminated veneer lumber with ramie fibre. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 332, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, T.; Rothe, J.; Castro, J.D.; Osei-Antwi, M. GFRP-balsa sandwich bridge deck concept, design and experimental validation. J. Compo.s Construct. 2014, 18, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Liu, W.; Fang, H.; Bai, Y.; Hui, D. Flexural responses and pseudo-ductile perfor mance of lattice-web reinforced GFRP-wood sandwich beams. Compos. B Eng. 2017, 108, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadir Y, Nagarajan P, Ameen, M. , et al. Flexural stiffness and strength enhancement of horizontally glued laminated wood beams with GFRP and CFRP composite sheets. Construct. Build. Mater. 2016, 112, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, A. D.; Bai, Y.; Ferdous, W. Flexural behaviour of GFRP-softwood sandwich panels for prefabricated building construction. 2023; 15. [Google Scholar]

- Szwajka, K.; Zielińska-Szwajka, J.; Trzepieciński, T.; Szewczyk, M. Experimental Study on Mechanical Performance of Single-Side Bonded Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Plywood for Wood-Based Structures. Mater. 2025, 18, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Hunt, J.F.; Gong, S.; Cai, Z. High strength wood-based sandwich panels reinforced with fiberglass and foam. BioResources 2014, 9, 1898–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smardzewski, J.; Kamisiński, T.; Dziurka, D. , Mirski, R.; Majewski, A.; Flach, A.; Pilch, A. Sound absorption of wood-based materials. Holzforschung, 2015, 69, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzola-Villegas, X. , Báez, C., Lakes, R., Stone, D.S., O’Dell, J., Shevchenko, P., Xiao, X.; De Carlo, F.; Jakes, J.E. Convolutional neural network for segmenting micro-x-ray computed tomography images of wood cellular structures. Appl. Sci.-Basel, 2023, 13, 8146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiman, M.V.; Stanciu, M.D.; Roșca, I.C.; Georgescu, S.V.; Năstac, S.M.; Câmpean, M. Influence of the grain orientation of wood upon its sound absorption properties. Mater. 2023, 16, 5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. (2014). Handbook of Acoustics. 2nd edition. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin.

- Cao, L.; Fu, Q.; Si, Y.; Ding, B.; Yu, J. Porous materials for sound absorption. Compos. Commun. 2018, 10, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Y.; Jeff, L.; Johni, C.; Gilsoo, C. Sound Absorption Coefficients of Micro-Fiber Fabrics by Reverberation Room Method. Textile Research Journal, 2007, 77, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkel, A. (1970). Wood Material Technology, Faculty of Forestry Publications. Publication No. 147, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey.

- Roziņš, R.; Brencis, R.; Spulle, U.; Spulle-Meiere, I. Sound Absorption Properties of the Patented Wood, Lightweight Stabilised Blockboard. Rural Sustainability Res. 2023, 50, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunok, M.; Ayan, S. . Determination of Sound Absorption Coefficient Values on The Laminated Panels. J. Polytec. 2012, 15, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Bertolini, M.; de Morais, C.A.G.; Christoforo, A.L.; Bertoli, S.R.; dos Santos, W.N.; Lahr, F.A.R. Acoustic absorption and thermal insulation of wood panels: Influence of porosity. BioResources, 2019, 14, 3746–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Pu, Z.; Haijun, F.; Yi, Z. Experiment study on sound properties of carbon fiber composite material. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 542, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, E.M.; Dettendorfer, A.; Kain, G.; Barbu, M.C.; Réh, R.; Krišťák, Ľ. Sound-absorption coefficient of bark-based insulation panels. Polym. 2020, 12, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özyurt, H. Sound Absorption Efficiency of Plywood-Carbon Fiber Composites: A New Frontier in Wood Material Science. BioResources, 2025, 20, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.S.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, H.J. Rice straw-wood particle composite for sound absorbing wooden construction materials. Bioresource Technology 2003, 86, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayan, S. 2012. Determination of acoustical properties of heat treated laminated wooden panels. PhD The sis. Gazi University. 179p.

- Kaya, A.İ.; Dalgar, T. Acoustic Properties of Natural Fibers in Terms of Sound Insulation. Journal of Mehmet Akif Ersoy University Institute of Science and Technology 2017, 8, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, V.; Di Bella, G.; Valenza, A. Glass–basalt/epoxy hybrid composites for marine applications. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 2091–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, A.R.; Jagtap, R.N. Surface morphology and mechanical properties of some unique natural fiber reinforced polymer composites-a review. J. Mater. Environ. Sci, 2015, 6, 902–917. [Google Scholar]

- TS EN 323/1: 1999; Wood based panels - determination of unit volume weight, TSE Standard, Ankara Türkiye, 1999.

- ASTM E1050-19 :2019; Standard Test Method for Impedance and Absorption of Acoustical Materials Using a Tube, Two Microphones and a Digital Frequency Analysis System, Ed.; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Özyurt, H.; Özdemir, F. Laminated wood composite design with improved acoustic properties. BioResources 2022, 17, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghofrani, M.; Ashori, A.; Rezvani, M.H.; Ghamsari, F.A. Acoustical properties of plywood/waste tire rubber composite panels. Measurement 2016, 94, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.; Bülbül, R.; Türk, M. Investigation of thermal and sound ınsulation properties of sapwood and heartwood of willow Tree. BioResources 2025, 20, 3224–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Material Name | Density (gr/cm3) |

Where used in the panel |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | OSB-2 Class | 0.630 | core layer |

| 2 | PPWD | 0.500 | face layer and bottom layer |

| 3 | BFRP | 2.800 | face layer betwen core layer, and bottom layer between layer |

| 4 | GFRP | 2.500 | face layer betwen core layer, and bottom layer between layer |

| 5 | Jute Fabric | 1.300 | face layer betwen core layer, and bottom layer between layer |

| Group | Code | Face Layer | FRP Types | Core Layer | Bottom Layer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | PP-B-O-B-PP | PP (PPWD) | B (BFRP) | O (OSB-2 class) | PP (PPWD) |

| B | PP-J-O-J-PP | PP (PPWD) | J (Jute Fabric) | O (OSB-2 class) | PP (PPWD) |

| C | PP-G-O-G-PP | PP (PPWD) | G (GFRP) | O (OSB-2 class) | PP (PPWD) |

| D | PP-O-PP | PP (PPWD) | - | O (OSB-2 class) | PP (PPWD) |

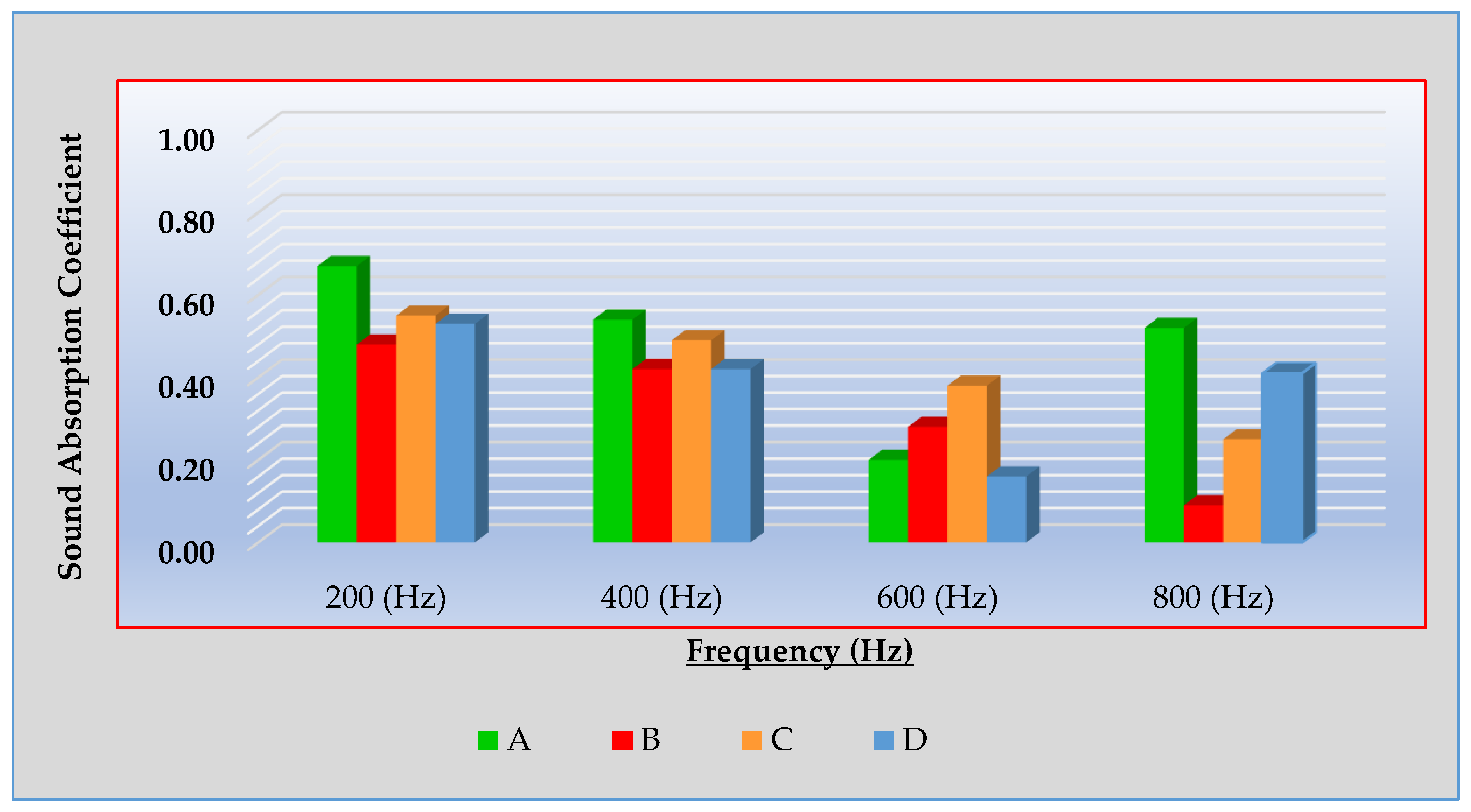

| Group | Frequency (Hz) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 (Hz) | 400 (Hz) | 600 (Hz) | 800 (Hz) | |

| A | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.20 | 0.52 |

| B | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.28 | 0.13 |

| C | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.33 |

| D | 0.53 | 0.42 | 0.16 | 0.41 |

| X | 0.56 | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.35 |

| S | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| X min | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.16 | 0.13 |

| X max | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.52 |

| (P ≤ 0.05) | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.0000* | 0.000* |

| Note: X: average value; S: the standard deviation; X min: minimum value; and X max: maximum value. | ||||

| Group | Frequency (Hz) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 1200 | 1400 | 1600 | |

| A | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.16 |

| B | 0.16 | 0.85 | 0.62 | 0.37 |

| C | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.51 | 0.07 |

| D | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.13 |

| X | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.18 |

| S | 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.12 |

| X min | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| X max | 0.44 | 0.85 | 0.62 | 0.37 |

| (P ≤ 0.05) | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.000* |

| Note: X: average value; S: the standard deviation; X min: minimum value; and X max: maximum value | ||||

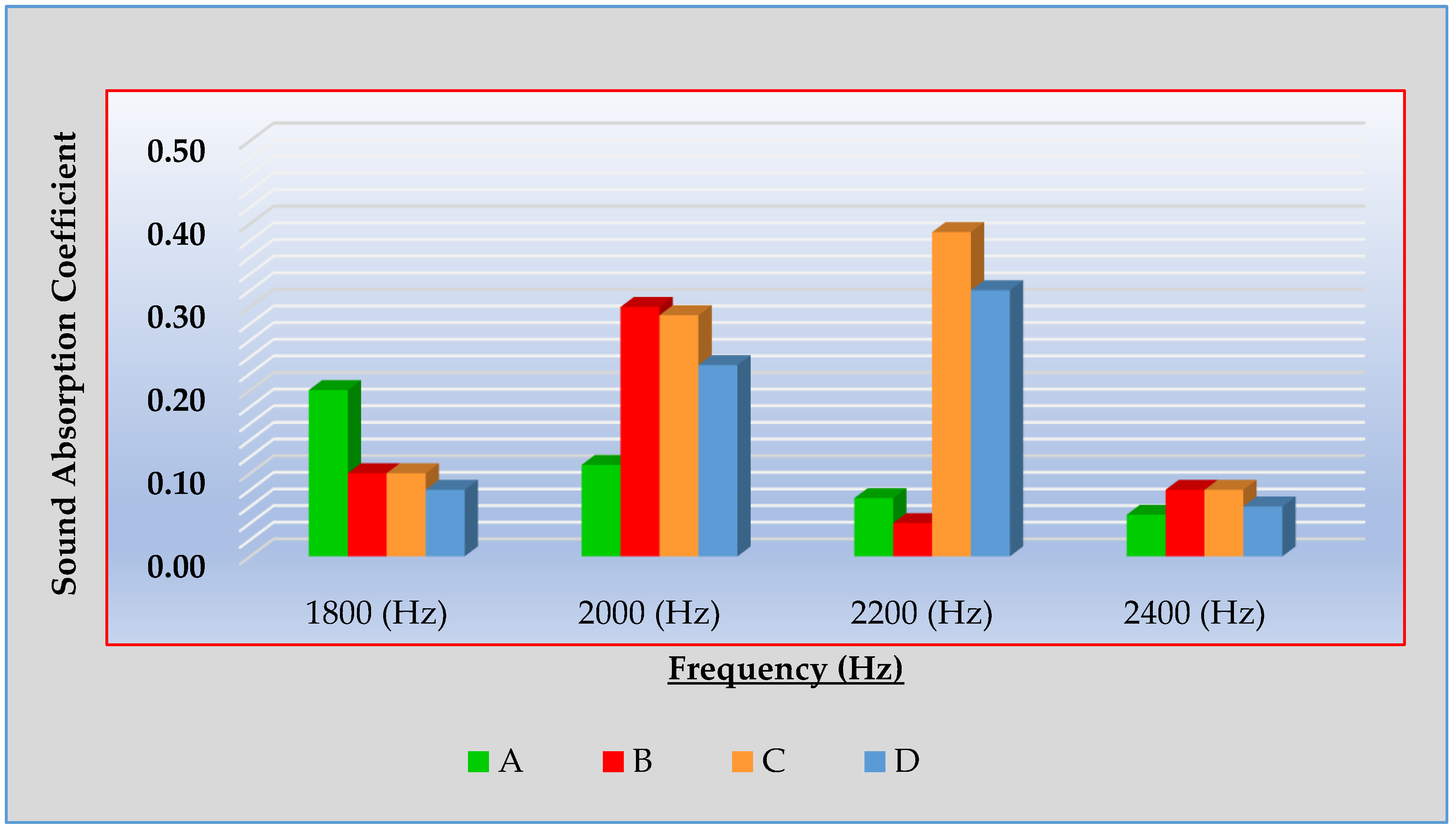

| Group | Frequency (Hz) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 2000 | 2200 | 2400 | |

| A | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| B | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.07 |

| C | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.32 | 0.08 |

| D | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| X | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.06 |

| S | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.18 |

| X min | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| X max | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.08 |

| (P ≤ 0.05) | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.000* |

| Note: X: average value; S: the standard deviation; X min: minimum value; and X max: maximum value | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).