1. Introduction

Environmental noise pollution is a significant and growing global challenge, with particularly severe consequences for urban and developing areas. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), noise pollution is one of the most pressing environmental risks, second only to air pollution, and it is responsible for a range of adverse health effects, including stress, sleep disturbances, cardiovascular diseases, and mental health issues [

1]. In cities and densely populated regions, where industrial activity, transportation, and other anthropogenic factors are prevalent, the detrimental effects of noise on human health are exacerbated. Recent research has confirmed the urgency of addressing noise as a critical environmental hazard, given its increasing impact on public health [

2]. The health implications of noise pollution are wide-ranging, and the need for effective noise control measures has never been more critical.

Long-term exposure to elevated noise levels has been associated with various cardiovascular disorders, including hypertension, heart attacks, and even premature mortality [

1]. Furthermore, noise pollution has a direct effect on cognitive development and performance in children and adults, impacting learning, memory, and overall productivity [

1]. Given the ubiquity of noise in modern life, finding sustainable solutions to mitigate its impact has become an essential part of urban planning and public health policies.

Traditional materials used for sound absorption, such as synthetic foams and mineral wool, have been effective in controlling noise, but they come with significant environmental and health drawbacks. These materials are typically derived from petrochemical-based sources, making them non-biodegradable and contributing to environmental degradation when disposed of at the end of their life cycle. The production of synthetic sound absorbers also generates substantial emissions and contributes to the depletion of natural resources, raising concerns about their sustainability. As a result, there is an increasing need for alternative, environmentally friendly sound-absorbing materials that can address both the acoustic and environmental challenges posed by traditional materials.

In recent years, there has been growing interest in the use of natural fiber-based composites as sustainable alternatives for sound absorption. Materials derived from agricultural waste, such as sugarcane bagasse, have shown promise in this regard. These materials offer the potential for comparable acoustic performance to conventional synthetic absorbers while being biodegradable and less harmful to the environment [

3,

4]. The use of agricultural by-products for the development of bio-based composites aligns with the global push toward sustainability and circular economy practices, wherein waste materials are reused to create valuable resources. Moreover, sugarcane bagasse, a widely available agricultural by-product, can replace synthetic materials in various applications, reducing dependence on finite resources and supporting sustainable development [

3].

The morphology of plant-based composites plays a crucial role in determining their acoustic performance. The porosity and alignment of fibers within the composite material are key factors that influence its ability to absorb sound [

5,

6]. Increased porosity allows sound waves to penetrate the material more easily, where they are then dissipated as heat through viscous interactions. Furthermore, optimizing fiber alignment can enhance the material’s ability to dissipate sound energy, improving its overall acoustic properties. Techniques such as additive manufacturing have enabled the precise control of fiber alignment and porosity, allowing for the creation of complex geometries that further enhance the acoustic performance of these materials [

7,

8]

Several fabrication techniques are commonly employed in the development of bio-composite acoustic panels. Hand lay-up and compression molding are two such methods that affect the performance of the material by influencing fiber distribution and matrix connectivity. Hand lay-up is a relatively simple and adaptable method that allows for uniform fiber distribution and effective resin impregnation [

9]. This technique has been shown to result in superior control over the material’s structure, ensuring that the desired acoustic properties are achieved. In contrast, compression molding, while more complex, typically yields stronger mechanical properties due to better fiber alignment and increased density [

10]. The choice of fabrication method is crucial in determining the acoustic properties of bio-composite panels, as uniform fiber distribution and proper resin impregnation are essential for optimizing sound absorption.

The geometric configuration of the material, including perforation size and panel shape, also plays a critical role in enhancing acoustic performance. Perforated panels have been found to improve sound absorption by allowing sound waves to enter the material more effectively and dissipate energy through air friction and viscous damping [

11]. The size and distribution of perforations in the panel affect its performance at different frequencies. For example, panels with small perforations are more effective at absorbing high-frequency sounds, while larger perforations are better suited for low-frequency noise. The arrangement of perforations within the panel can also influence its overall acoustic behavior, with certain patterns optimizing absorption across a broad range of frequencies.

This study aims to investigate the effect of partial perforations on the sound absorption characteristics of sugarcane bagasse-based composites. While the use of perforations in porous materials to enhance acoustic performance is well-established, the specific impact of perforation patterns on the properties of natural fiber composites, especially those derived from agricultural waste, remains underexplored [

12,

13]. By focusing on the microstructural complexities of sugarcane bagasse composites, this study seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of how varying perforation designs can optimize the acoustic performance of these sustainable materials.

In addition to improving the sound absorption performance, the reuse of agricultural waste, such as sugarcane bagasse, aligns with the principles of the circular economy. Agricultural waste, often discarded or burned, can be transformed into valuable materials that contribute to both environmental sustainability and economic development [

14,

15]. This approach not only reduces waste but also minimizes the environmental impact of traditional noise-control materials, thereby contributing to the broader goal of sustainable material development [

16].

The potential applications of bio-based sound absorbers in urban planning, construction, and noise mitigation are vast. The incorporation of natural fiber-based panels, such as those made from sugarcane bagasse, into building designs can help manage noise pollution, improve the quality of urban living, and contribute to energy efficiency [

4,

17]. These materials are not only effective in controlling noise but also provide economic benefits by reducing energy consumption through enhanced thermal insulation properties. Moreover, the adoption of sustainable acoustic materials supports public health by mitigating the negative effects of noise-related stress and annoyance [

18].

2. Materials and Methods

For this study, sugarcane bagasse, an abundant agricultural by-product from the sugar industry, was selected as the primary raw material for the sound-absorbing composite panels. The bagasse was sourced from Arasoe Sugarcane Plant, Bone, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Bagasse is rich in cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, which makes it a suitable candidate for use in bio-composites (

Figure 1). The fibers were first subjected to a chemical treatment to remove impurities and to improve fiber-matrix bonding. A 5% sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution was used for the alkali treatment, a well-established method for enhancing the surface properties of lignocellulosic fibers. NaOH treatment has been reported to increase fiber surface roughness and improve the interface between the fibers and the resin matrix [

19,

20]. Following treatment, the fibers were dried at ambient temperature for 8 hours to remove excess moisture before use in the composite preparation.

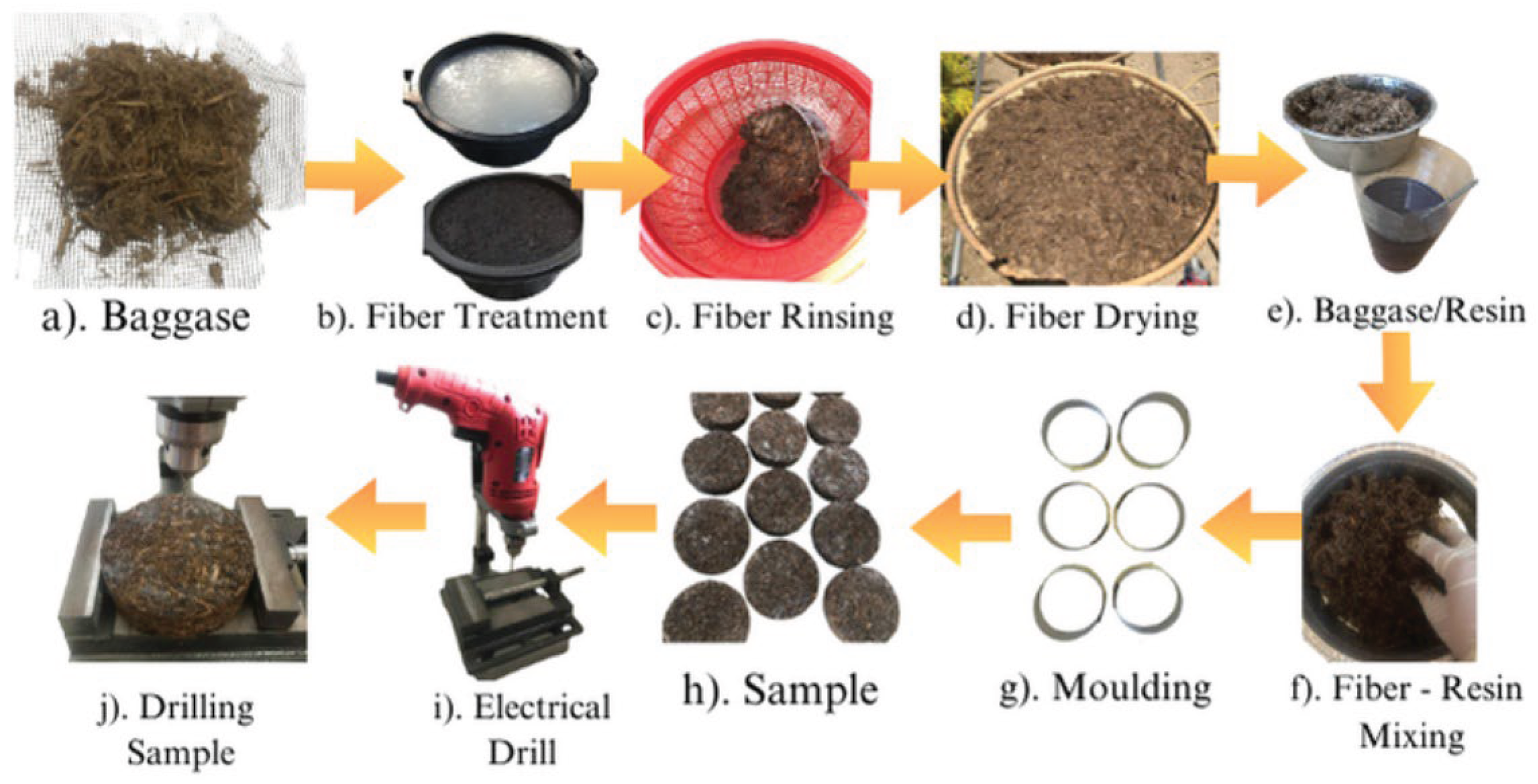

The composite panels were fabricated using the hand lay-up technique, a widely employed method for manufacturing bio-based composites due to its simplicity and versatility [

9]. In this study, the bagasse fibers were mixed with a polyester resin at a weight ratio of 60:40, which is considered optimal for balancing mechanical strength and acoustic performance in bio-composites [

10]. The polyester resin used was unsaturated, with a specific gravity of 1.215 g/cm

3, and a 1% catalyst was added to initiate the curing process.

The fibers and resin were thoroughly mixed to ensure uniform distribution of the fibers throughout the matrix. After mixing, the composite material was poured into cylindrical molds with a diameter of 100 mm and a thickness of 30 mm, which is the standard size for acoustic testing in impedance tubes [

21]. The molds were coated with a non-stick substance to facilitate the removal of the cured samples. The composites were then allowed to cure at room temperature for 24 hours, following which they were demolded and prepared for further processing (

Figure 2).

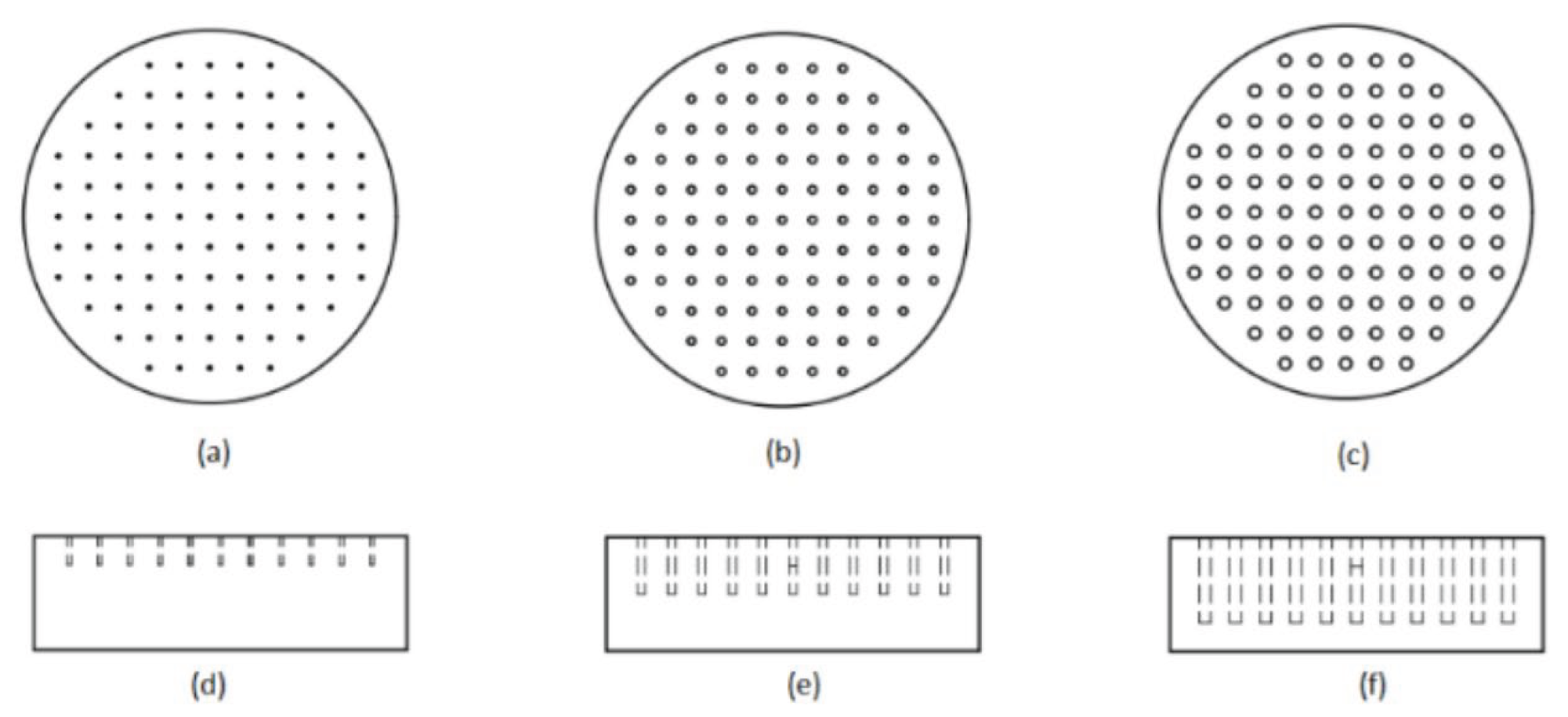

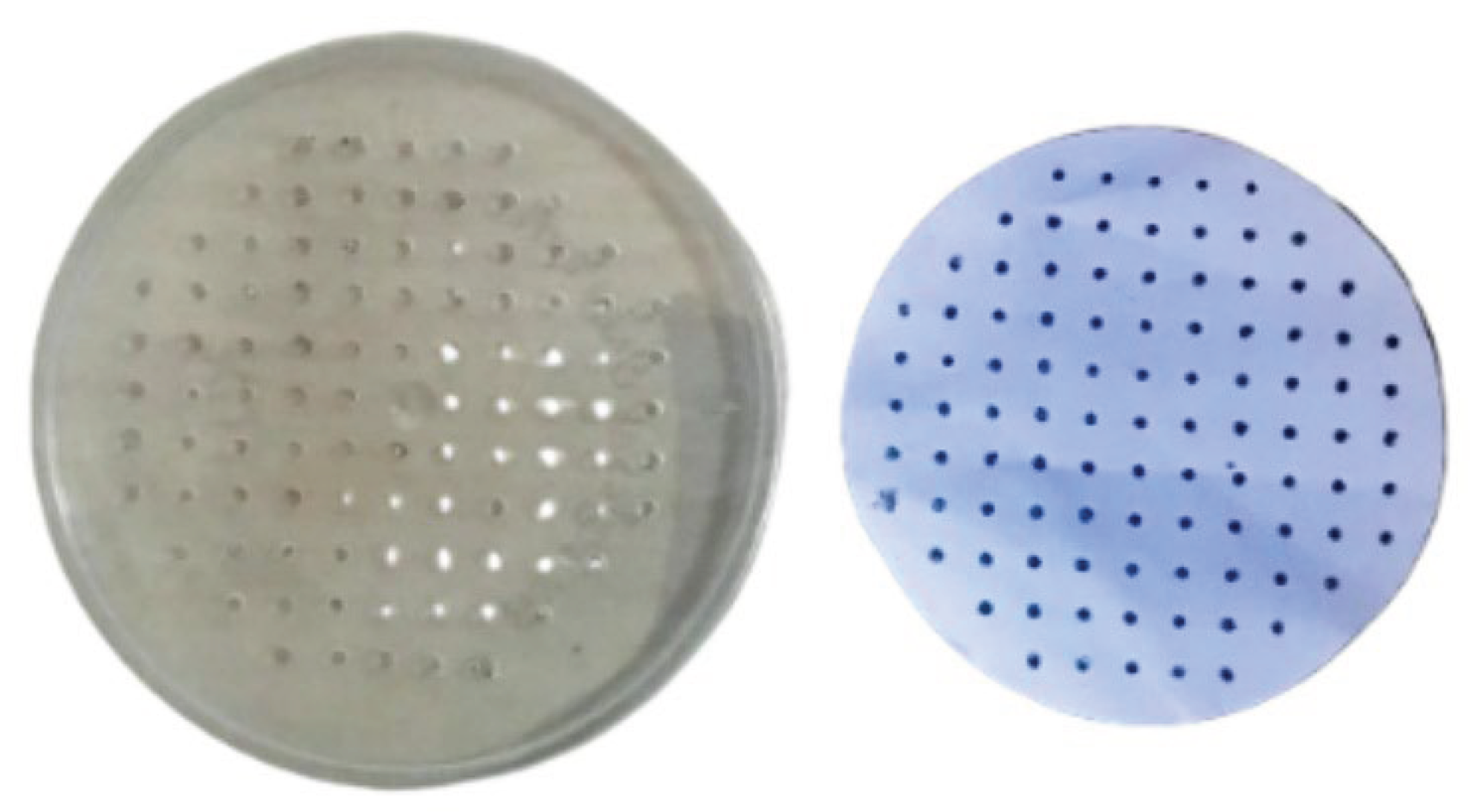

After curing, the composite panels were carefully removed from the molds. To enhance their acoustic performance, partial perforations were introduced to the panels using an electric drill. The perforation sizes were varied in this study, with diameters of 1 mm, 2 mm, and 3 mm, and depths set at 25%, 50%, and 75% of the panel thickness (

Figure 3). The perforation patterns (

Figure 4) were designed to disrupt the normal reflection of sound waves and enhance sound absorption by introducing additional paths for sound energy dissipation [

11,

22]. The perforations were made using a drill template to ensure consistent and precise hole placement across all samples. The final dimensions of the prepared samples were 100 mm in diameter and 30 mm in thickness, with the perforations evenly distributed across the surface. These samples were then subjected to acoustic testing (

Figure 5).

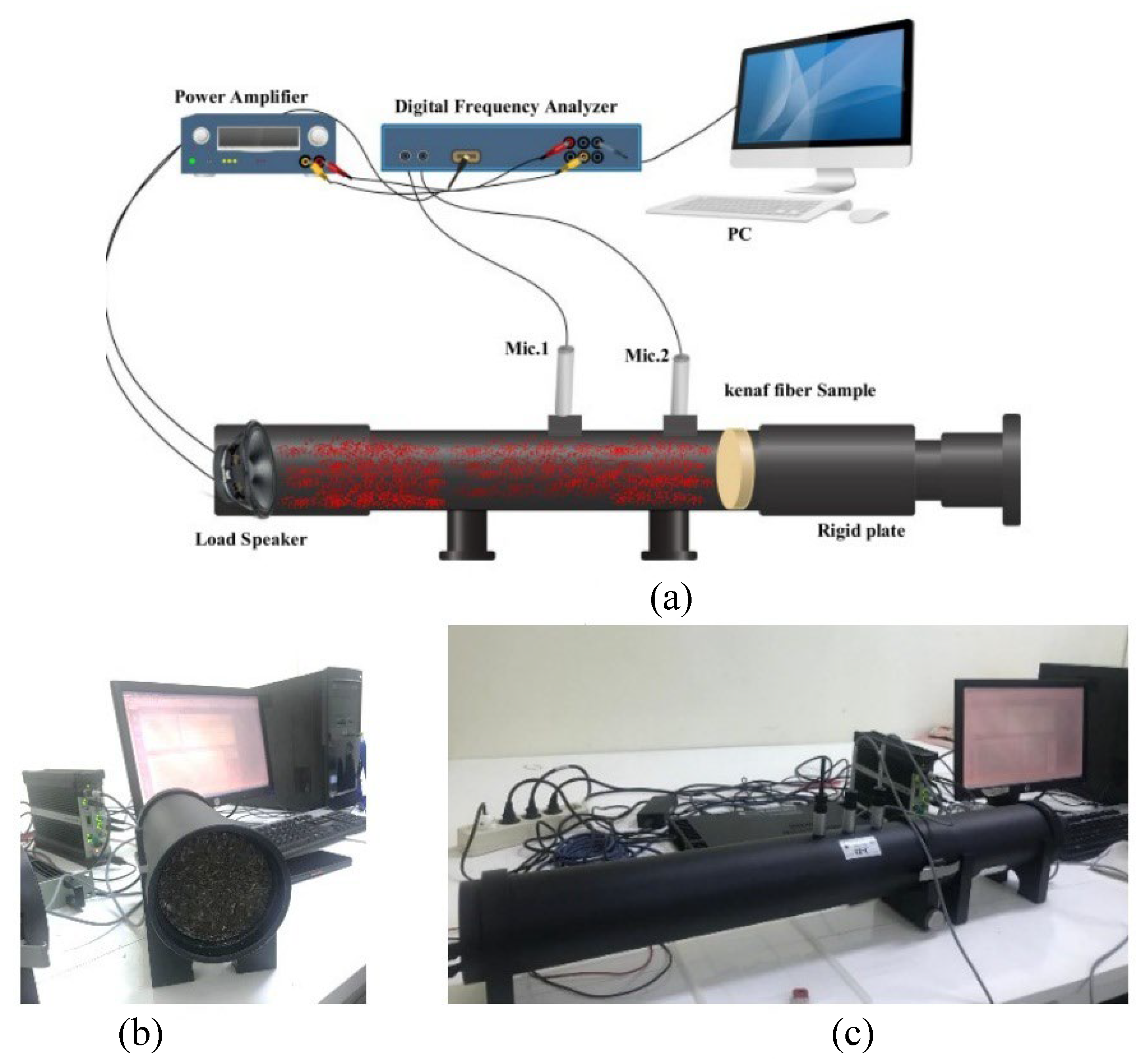

The sound absorption characteristics of the composite panels were measured using the two-microphone impedance tube method, as per ASTM E1050-98 standards [

23]. This method is widely used for evaluating the sound absorption coefficient (SAC) of small-sized materials and provides reliable results in the frequency range of 200 Hz to 1600 Hz [

24]. The impedance tube used in this study was a Brüel & Kjær 4206 type, equipped with two ¼-inch condenser microphones (type 4187), an amplifier (2716C), and the PULSE system for signal processing and data acquisition.

The SAC was determined by measuring the incident and reflected sound waves as they interacted with the material. The samples were positioned inside the impedance tube, and the sound waves were generated by a loudspeaker placed at one end of the tube (

Figure 6). The microphones recorded the sound pressure levels at two points, allowing the software to calculate the SAC at various frequencies. Each sample was tested three times to ensure the repeatability of the results.

The acoustic data were statistically analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate the significance of perforation diameter and depth on the SAC. This analysis was performed to determine if the main effects of perforation diameter and depth, as well as their interaction, significantly influenced the sound absorption performance. A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered for all statistical tests. The design was based on a 3x3 factorial arrangement, where three levels of perforation diameter (1 mm, 2 mm, 3 mm) and three levels of perforation depth (25%, 50%, 75%) were considered (

Table 1).

The ANOVA results were followed by post-hoc pairwise comparisons to further explore the differences between groups when significant effects were found. All statistical analyses were performed using standard statistical software, and the results were presented as mean values with standard deviations to show the variability across the samples.

3. Results

3.1. Sound Absorption Coefficient (SAC) of the Composite Samples

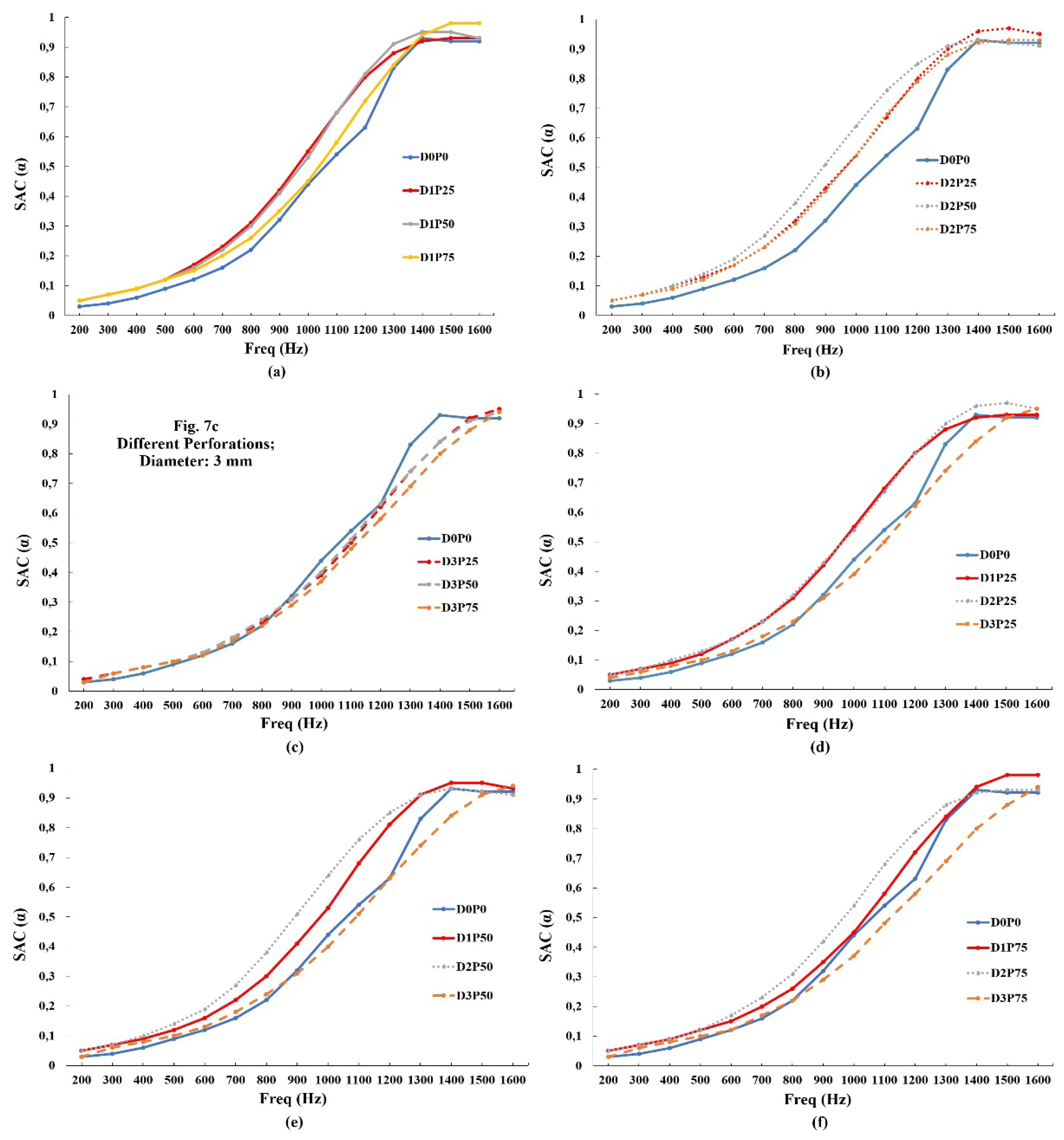

The SAC of the sugarcane bagasse-based composite panels was evaluated across the frequency range of 200 Hz to 1600 Hz. The results revealed that the SAC values of the composite panels varied significantly depending on the perforation diameter and depth. As shown in

Table 2, the SAC values for the untreated composite (Flat) ranged from 0.03 to 0.44 across the tested frequencies. In contrast, the perforated panels demonstrated a marked improvement in SAC, with values ranging from 0.05 to 0.98, depending on the perforation parameters.

In general, samples with a perforation diameter of 1 mm and a perforation depth of 75% achieved the highest SAC values, with a peak of 0.98 at frequencies between 1500 Hz and 1600 Hz (

Figure 7a). This indicates that small perforations (1 mm) with deep perforation (75%) significantly enhance the sound absorption performance, especially at high frequencies. Similar trends were observed for panels with 2 mm and 3 mm perforations, although the SAC values for the 3 mm perforations were lower, particularly at the lower frequencies (

Figure 7b,c).

3.2. Effect of Perforation Diameter on SAC

Figure 7a–f illustrates the relationship between perforation diameter and SAC across different depths of perforation. The results indicate that the perforation diameter plays a significant role in enhancing the acoustic performance of the composite panels. Panels with a perforation diameter of 1 mm exhibited the highest SAC, especially at mid to high frequencies (1000 Hz to 1600 Hz). As the perforation diameter increased to 2 mm and 3 mm, the SAC values decreased, particularly at lower frequencies (

Figure 7b,c).

These findings are consistent with previous studies which reported that smaller perforations lead to better sound absorption at higher frequencies due to enhanced interaction between sound waves and the material [

22,

25]. Moreover, the results suggest that an optimal perforation diameter of 1 mm maximizes the absorption of sound waves, particularly at mid-range frequencies, which is the most common range of environmental noise.

3.3. Effect of Perforation Depth on SAC

The depth of perforation also significantly influenced the SAC values. As shown in

Figure 7a–f, increasing the perforation depth from 25% to 75% enhanced the SAC across all perforation diameters. The 75% perforation depth yielded the highest SAC, particularly for 1 mm and 2 mm perforations. Panels with a perforation depth of 75% exhibited SAC values approaching 1.0 at frequencies between 1500 Hz and 1600 Hz, which indicates nearly perfect sound absorption at these frequencies (

Figure 7a).

In comparison, panels with a perforation depth of 25% demonstrated lower SAC values, particularly at lower frequencies (

Figure 7d). This observation supports findings from prior studies, which suggest that deeper perforations allow for better sound wave penetration into the material, thereby increasing the dissipation of sound energy through viscous damping and thermal conversion [

22,

26].

3.4. Comparison of SAC for Different Perforation Configurations

Table 2 summarizes the SAC values for different perforation configurations across the frequency spectrum. The highest overall SAC was observed in the composite panel with 1 mm perforations and a 75% perforation depth, followed by 2 mm perforations with a 75% perforation depth. The samples with 3 mm perforations generally displayed lower SAC values across all frequencies, indicating that larger perforations may reduce the material’s ability to absorb sound effectively, particularly at lower frequencies.

These results align with the literature, which suggests that perforation size and depth need to be optimized to balance the benefits of improved sound wave interaction and the structural integrity of the material. Excessively large perforations may disrupt the internal pore structure, reducing the overall effectiveness of the material in absorbing sound [

27,

28].

3.5. Frequency-Specific Performance

The SAC performance at various frequencies showed that the composite panels with small perforations (1 mm and 2 mm) excelled in the mid to high-frequency range (1000 Hz to 1600 Hz). For instance, panels with 1 mm perforations and 75% depth achieved peak SAC values of 0.98 at 1500 Hz and 1600 Hz (

Figure 7a). However, at low frequencies (200 Hz to 600 Hz), the SAC was lower, with values ranging from 0.03 to 0.1, indicating less effective absorption at lower frequencies (

Figure 7d).

This frequency-specific behavior is consistent with previous studies that have reported that natural fiber composites and perforated panels typically perform better at higher frequencies, where the sound wave interaction with the material is more effective (Shen et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2015). To enhance low-frequency absorption, modifications such as increasing panel thickness or adjusting pore structures have been suggested in the literature [

29,

30].

3.6. Interaction between perforation diameter and depth

Two-way ANOVA was performed to analyze the effect of perforation diameter and depth on the SAC. The results indicated that both perforation diameter (p < 0.01) and perforation depth (p < 0.05) had a statistically significant effect on the SAC. The interaction between perforation diameter and depth was found to be significant (p < 0.05), suggesting that the optimal acoustic performance is achieved when both parameters are considered together. Post-hoc comparisons further revealed that panels with 1 mm perforations and 75% depth significantly outperformed other configurations in terms of SAC at mid to high frequencies.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate a significant enhancement in the sound absorption coefficient (SAC) of the sugarcane bagasse-based composite panels with the introduction of partial perforations. The samples with perforations, particularly those with a 1 mm diameter and 75% perforation depth, exhibited SAC values reaching 0.98 at frequencies between 1500 Hz and 1600 Hz, which is indicative of near-perfect sound absorption (

Figure 7a). These findings support previous research, which has shown that perforated panels can improve sound absorption by providing additional pathways for sound energy dissipation through viscous damping and thermal conversion [

22,

26].

The optimal perforation depth of 75% was found to significantly improve SAC, especially at mid and high frequencies (1000 Hz–1600 Hz), consistent with studies that suggest deeper perforations allow for better sound wave penetration and energy dissipation within porous materials [

11,

21]. In comparison, the non-perforated (flat) samples demonstrated considerably lower SAC values, ranging from 0.03 to 0.44, which aligns with the general trend that non-perforated materials are less effective at absorbing sound compared to perforated counterparts [

28]. Therefore, the introduction of perforations, particularly with the optimal diameter and depth, clearly enhances the acoustic performance of bagasse-based composites, confirming the potential of partial perforation designs to optimize sound absorption.

The enhanced SAC observed in the perforated composites can be attributed to the mechanisms of absorption in porous materials, which involve viscous losses, thermal conduction, and inertial effects [

31]. When sound waves interact with the perforated surface, they generate a shear force between the air molecules and the fiber structure, leading to energy dissipation through friction and conversion of sound energy into heat. This phenomenon, known as viscous damping, is particularly effective at higher frequencies, where the sound wave’s shorter wavelength allows for more efficient interaction with the material [

30].

Moreover, the increased porosity from the perforations facilitates better air movement within the material, enhancing the efficiency of the viscous damping mechanism [

30]. The interaction between the sound waves and the porous network in the composite leads to greater attenuation of sound energy, thus improving the material’s ability to absorb sound. These findings are consistent with the literature, which highlights the crucial role of porosity, pore distribution, and fiber alignment in optimizing sound absorption performance [

5,

6].

The results of this study indicate that perforation diameter plays a significant role in the sound absorption properties of the composites. The 1 mm perforations consistently outperformed the 2 mm and 3 mm perforations in terms of SAC, especially at mid to high frequencies (

Figure 7a). This can be explained by the relationship between perforation size and pore interconnectivity. Smaller perforations, such as those with a diameter of 1 mm, enhance the interaction between sound waves and the material by increasing the connectivity of the internal pores, thus promoting greater energy dissipation [

22].

As the perforation diameter increased to 2 mm and 3 mm, the SAC decreased, particularly at lower frequencies, as the larger perforations reduced the effectiveness of sound wave penetration into the material. This observation is in line with studies that suggest perforations that are too large may reduce the material’s ability to trap sound waves, resulting in diminished acoustic performance [

27,

28]. Therefore, optimizing perforation size is crucial in achieving high SAC values, particularly at mid and high frequencies.

A key finding in this study is the frequency-specific performance of the sugarcane bagasse composites. As shown in the results, the composites performed well at mid to high frequencies, with peak SAC values of 0.98 at 1500 Hz and 1600 Hz for samples with 1 mm perforations and 75% depth (

Figure 7a). However, at lower frequencies (200 Hz–600 Hz), the SAC was significantly lower, ranging from 0.03 to 0.1. This is consistent with previous research, which has noted that natural fiber composites generally exhibit better sound absorption at higher frequencies due to their smaller pore structures and more efficient interaction with sound waves [

30,

32].

The reduced SAC at lower frequencies can be attributed to the longer wavelength of low-frequency sound waves, which are less likely to interact effectively with the smaller pores of the material. This is a common limitation observed in many bio-based composites, including those made from sugarcane bagasse [

29]. To enhance low-frequency absorption, modifications such as increasing panel thickness or optimizing pore structure have been suggested in the literature [

30,

33]. Future research may explore these modifications to further improve the acoustic performance of these materials.

Another significant observation from the results is the impact of perforation size on the effective surface area available for sound absorption. While larger perforations allow for greater airflow through the material, they may also reduce the internal pore connectivity, leading to lower SAC values. For example, the 3 mm perforations exhibited the lowest SAC values, particularly at lower frequencies, as the larger holes disrupted the material’s ability to trap and dissipate sound energy [

34,

35].

This observation supports the findings of previous studies, which have suggested that small to medium-sized perforations are more effective at improving sound absorption by enhancing energy loss mechanisms such as viscous damping and thermal conduction [

22,

28]. Excessively large perforations can lead to a loss of structural integrity, making the material less effective at absorbing sound, particularly at lower frequencies.

While this study provides valuable insights into the acoustic performance of sugarcane bagasse-based composites with partial perforations, there are several limitations that need to be addressed in future research. First, the study focused on a narrow frequency range (200 Hz–1600 Hz), which may not fully capture the material’s performance across a broader spectrum of sound frequencies. To improve the generalizability of the results, future studies should extend the frequency range to include lower frequencies, where significant sound absorption often occurs [

36]. Second, while perforation diameter and depth were found to significantly affect the SAC, other factors such as panel thickness, porosity ratio, and fiber orientation also influence the material’s acoustic performance. Further research should explore the combined effects of these factors and investigate the optimal configurations for enhancing sound absorption at both low and high frequencies.

Finally, the environmental and economic benefits of using sugarcane bagasse as a raw material for sound absorbers should be assessed through lifecycle analysis (LCA) to quantify the environmental impact of these materials compared to conventional synthetic sound absorbers. This will help validate their sustainability and feasibility for large-scale applications in noise control [

37,

38].

5. Conclusions

This study investigates the acoustic performance of sugarcane bagasse-based composite panels with partial perforations, focusing on the effects of perforation diameter and depth on sound absorption. The results clearly demonstrate that perforation significantly enhances the sound absorption coefficient (SAC) of these bio-composite panels, especially at mid and high frequencies. The composite panel with 1 mm perforations and a 75% perforation depth achieved the highest SAC, nearing 0.98 at 1500 Hz and 1600 Hz, showcasing the potential of optimizing perforation patterns to improve acoustic performance.

The analysis of perforation diameter revealed that smaller perforations (1 mm) provided better sound absorption than larger perforations (2 mm and 3 mm), particularly at higher frequencies. Additionally, the increased perforation depth was found to improve SAC, with deeper perforations allowing for more effective sound wave penetration into the material, leading to better energy dissipation.

However, the study also identified that perforations larger than 2 mm could reduce the material’s overall acoustic performance, particularly at lower frequencies. This highlights the importance of balancing perforation size to optimize both structural integrity and sound absorption performance.

While the results demonstrate strong potential for sugarcane bagasse-based composites as sound-absorbing materials, their performance was limited at low frequencies. Future research should explore modifications such as increasing panel thickness, optimizing pore structure, or incorporating hybrid materials to improve low-frequency sound absorption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ilham Bakri and Fatimah Sahra Musafir; Data curation, Fatimah Sahra Musafir and Rizki Nur Fadhilah; Formal analysis, Fatimah Sahra Musafir; Investigation, Fatimah Sahra Musafir; Methodology, Ilham Bakri, Fatimah Sahra Musafir and Asniawaty Kusno; Resources, Fatimah Sahra Musafir and Rizki Nur Fadhilah; Software, Asniawaty Kusno and Rizki Nur Fadhilah; Supervision, Ilham Bakri and Kifayah Amar; Validation, Ilham Bakri, Fatimah Sahra Musafir, Asniawaty Kusno and Rizki Nur Fadhilah; Visualization, Ilham Bakri and Fatimah Sahra Musafir; Writing—original draft, Ilham Bakri and Fatimah Sahra Musafir; Writing—review & editing, Ilham Bakri and Kifayah Amar.

Funding

This research received no external funding, while the APC was funded by Hasanuddin University.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all laboratory assistants and technicians in the Department of Industrial Engineering and the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Hasanuddin University, for their invaluable technical assistance during the data collection process. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) utilized ChatGPT o3 to aid in the preparation of the manuscript and scite.ai to maintain the integrity of the references used. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| NaOH |

Sodium hydroxide |

| ASTM |

American Society for Testing and Materials |

| SAC |

Sound absorption coefficient |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| mm |

millimeter |

| Hz |

Hertz |

References

- Rastegar, N.; Ershad-Langroudi, A.; Parsimehr, H.; Moradi, G. Sound-Absorbing Porous Materials: A Review on Polyurethane-Based Foams. Iranian Polymer Journal 2022, 31, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Chunchun; Li, uiqin; Gong, Jixian; Chen, Jiahao; Li, Zheng; Li, Qiujin; Cheng, Meilin; Li, Xin; Zhang, Jianfei The Review of Fiber-Based Sound-Absorbing Structures. Textile Research Journal 2022, 93, 434–449. [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, Santhanam; Senthil Kumar, Selvaraj; Solomon, Eshetu; Getahun, Gedamnesh; Admassu, Yohaness; Bogale, Meseret; Gedilu, Mekdes; Aduna, Alemu; Abedom, Fasika Sound Absorbing and Insulating Properties of Natural Fiber Hybrid Composites Using Sugarcane Bagasse and Bamboo Charcoal. J Eng Fiber Fabr 2021, 16, 15589250211044818. [CrossRef]

- Gboe, N.; Grubliauskas, R. Advancing Sustainable Acoustic Solution: Exploring the Sound Absorption Characteristics of Biodegradable Agricultural Wastes, Coconut Fiber, Groundnut Shell, and Sugarcane Fiber. In Proceedings of the CONECT. International Scientific Conference of Environmental and Climate Technologies; May 29 2024; Vol. 0; p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan, R. A Comparative Study on Acoustic Parameters of Porous Absorber of Polyamide, Polyester and Polyurethane. International Scientific Journal of Engineering and Management 2023, 02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclaire, P.; Umnova, O.; Dupont, T.; Panneton, R. Acoustical Properties of Air-Saturated Porous Material with Periodically Distributed Dead-End Poresa). J Acoust Soc Am 2015, 137, 1772–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschmitz, S.; Ring, T.P.; Watschke, H.; Langer, S.C.; Vietor, T. Design and Additive Manufacturing of Porous Sound Absorbers—A Machine-Learning Approach. Materials 2021, 14, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attenborough, K. Microstructures for Lowering the Quarter Wavelength Resonance Frequency of a Hard-Backed Rigid-Porous Layer. Applied Acoustics 2018, 130, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, K.; Bajpai, P.K. Performance Analysis of Hybrid Bio-Composites Developed through Different Processing Routes for Automobile Application. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science.

- Barman, P.; Dutta, P.P.; Bardalai, M.; Dutta, P.P. Experimental Investigation on Bamboo Fiber Reinforced Epoxy Polymer Composite Materials Developed through Two Different Techniques. Proc Inst Mech Eng C J Mech Eng Sci 2024, 238, 2185–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puguan, J.M.C.; Pornea, A.G.M.; Ruello, J.L.A.; Kim, H. Double-Porous PET Waste-Derived Nanofibrous Aerogel for Effective Broadband Acoustic Absorption and Transmission. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2022, 4, 2626–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, A.; Abdullah, Y.; Efendy, H.; Mohamad, W.M.F.W.; Salleh, N.L. Biomass from Paddy Waste Fibers as Sustainable Acoustic Material. Adv Acoust Vib 2013, 2013, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.; Jamshaid, H.; Mishra, R.; Khan, M.Q.; Petru, M.; Tichy, M.; Muller, M. Factors Affecting Acoustic Properties of Natural-Fiber-Based Materials and Composites: A Review. Textiles 2021, 1, 55–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nik Pa, N.N.A.; Wan Ibrahim, M.H.; Abdul Ghani, A.H.; Mohd Ali, A.Z.; Arshad, M.F. Compressive Strength of Construction Materials Containing Agricultural Crop Wastes: A Review. MATEC Web of Conferences 2017, 103, 01018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandala, R.; Hegde, G.; Kodali, D.; Kode, V.R. From Waste to Strength: Unveiling the Mechanical Properties of Peanut-Shell-Based Polymer Composites. Journal of Composites Science 2023, 7, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, S.; Thakker, D.S. Development of Sustainable Tableware from Waste 2023.

- Rubino, C.; Bonet Aracil, M.; Gisbert-Payá, J.; Liuzzi, S.; Stefanizzi, P.; Zamorano Cantó, M.; Martellotta, F. Composite Eco-Friendly Sound Absorbing Materials Made of Recycled Textile Waste and Biopolymers. Materials 2019, 12, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Su, H.; Yang, D.; Xu, J. Eco-Innovation: Corn Stover as the Biomaterial in Packaging Designs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suckley, S.; Deenuch, P.; Disjareon, N.; Phongtamrug, S. Effects of Alkali Treatment and Fiber Content on the Properties of Bagasse Fiber-Reinforced Epoxy Composites. Key Eng Mater 2017, 757, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.; Oanh, D.T.Y.; Van Ngo, T.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Nguyen, M.V.; Nguyen, T.H.; Bui, T.T.T.; Le, T.H.N.; Nguyen, M.H.; Nguyen, Q.T. Enhancing Epoxy Composite Materials through Lime-treated Sugarcane Bagasse and Glass Fiber Reinforcement: Morphological, Mechanical, and Flame-retardant Insights. Vietnam Journal of Chemistry 2025, 63, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetiyo, I.; Sarwono, J.; Sihar, I. Study on Inhomogeneous Perforation Thick Micro-Perforated Panel Sound Absorbers. Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Sciences 2016, 10, 2350–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, V.; Eh Noum, S.Y.; Sivanesan, S.; Putra, A.; Kassim, D.H.; Wong, Y.S.; Chin, K.C. Effect of Perforation Volume on Acoustic Absorption of the 3D Printed Micro-Perforated Panels Made of Polylactic Acid Reinforced with Wood Fibers. J Phys Conf Ser 2021, 2120, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E1050-98: Standard Test Method for Impedance and Absorption of Acoustical Materials Using a Tube, Two Microphones, and a Digital Frequency Analysis System. ASTM E1050-98.

- Jayamani, E.; Hamdan, S.; Suid, N.B. Experimental Determination of Sound Absorption Coefficients of Four Types of Malaysian Wood. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2013, 315, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puguan, J.M.C.; Agbayani, D.B.A.; Sadural, A.J. V.; Kim, H. Enhanced Low Frequency Sound Absorption of Bilayer Nanocomposite Acoustic Absorber Laminated with Microperforated Nanofiber Felt. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2023, 5, 8880–8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Peng, L.; Fu, F.; Liu, M.; Zhang, H. Experimental and Theoretical Analysis of Sound Absorption Properties of Finely Perforated Wooden Panels. Materials 2016, 9, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larner, D.J.; Davy, J.L. Predicting the Absorption of Perforated Panels Backed by Resistive Textiles. Noise Control Eng J 2016, 64, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, B.T.; Barburski, M.; Witczak, E.; Puszkarz, A.K. Enhancement of Low and Medium Frequency Sound Absorption Using Fabrics and Air Gaps. Textile Research Journal 2023, 93, 5112–5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Du, B.; Ma, J.; Xiong, H.; Qian, J.; Cai, M.; Shui, A. Enhanced Sound Absorption Properties of Ceramics with Graphene Oxide Composites. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 34242–34249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Luo, Y.; Ni, L.; Liang, M.; Zhou, S.; Zou, H. Improved Sound Absorption Performance of Melamine/Waterborne Polyurethane Composite Foams Using Cyclic Freeze–Thawing. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2024, 6, 3564–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, G.; Zhou, G.; Bai, G.; Hu, K.; Han, S. Formation of Interpenetrating-Phase Composites Based on the Combined Effects of Open-Cell PIF and Porous TPU Microstructures for Enhanced Mechanical and Acoustical Characteristics. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2023, 5, 8023–8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yan, X.; Zhang, H. Effects of Pore Structure on Sound Absorption of Kapok-Based Fiber Nonwoven Fabrics at Low Frequency. Textile Research Journal 2016, 86, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Quan, J.; Thai, B.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Lan, X.; Yu, X.; Zhai, W.; Yang, Y.; Khoo, B.C. Ultralight Biomass-Derived Carbon Fibre Aerogels for Electromagnetic and Acoustic Noise Mitigation. J Mater Chem A Mater 2022, 10, 22771–22780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. , Z.; Zulkarnain; Nor, M.J.M.; Abdullah, S. Perforated Plate Backing with Coconut Fiber as Sound Absorber for Low and Mid Range Frequencies. Key Eng Mater 2011, 462–463, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlesso, M.; Giacomelli, R.; Günther, S.; Koch, D.; Kroll, S.; Odenbach, S.; Rezwan, K. Near-Net-Shaped Porous Ceramics for Potential Sound Absorption Applications at High Temperatures. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2013, 96, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charyyev, S.; Artz, M.; Szalkowski, G.; Chang, C.; Stanforth, A.; Lin, L.; Zhang, R.; Wang, C. -K. C. Optimization of Hexagonal-pattern Minibeams for Spatially Fractionated Radiotherapy Using Proton Beam Scanning. Med Phys 2020, 47, 3485–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluseun Adejumo, I.; Adebukola Adebiyi, O. Agricultural Solid Wastes: Causes, Effects, and Effective Management. In Strategies of Sustainable Solid Waste Management; IntechOpen, 2021.

- Seetharaman, S.; Subramanian, J.; Singh, R.A.; Wong, W.L.E.; Nai, M.L.S.; Gupta, M. Mechanical Properties of Sustainable Metal Matrix Composites: A Review on the Role of Green Reinforcements and Processing Methods. Technologies (Basel) 2022, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).