1. Introduction

Over the course of operation of machines and equipment, lubrication conditions may change due to the impact of the working environment, e.g. by way of a change in instantaneous load or operating temperature. Changes in operating conditions may also be continuous in nature on account of the time-dependent degradation of oil properties. The effects of oil degradation may include: colour change, increased acid number, formation of deposits and lakes, increased content of solid particles (solid contaminants), water ingress into oil, viscosity change, etc. [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Lubrication of friction nodes in driven machines [

6,

7,

8,

9] with contaminated oil typically renders them non-operational prematurely. Impure oil usually contains particles such as mineral grains, metal swarf, or water. The aforementioned contaminants can damage machine components, especially their drive units, leading to progressive wear and even failure. Such components include gear wheels, bearings, and seals, in particular. As for abrasives containing very hard grains, damage occurs as a consequence of micro-scratching or micro-ridging. The effects of such wear processes will depend significantly on the size, type, and hardness of the oil contaminating particles. The adverse effect of hard mineral abrasives on the wear of machine components is well known and extensively described in the literature on the subject [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Contaminated oil can also deteriorate in terms of its capacity to lubricate parts properly, resulting in excessive friction, overheating, and reduced performance. In many industries, degradation processes caused by lubrication with contaminated oil are counteracted by filtering [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], and fresh oil is added or replaced, yet in many cases this is still insufficient.

The potential effects of the presence of solid contaminants in lubricating oil depend on momentary lubrication conditions at friction nodes [

1,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. The key parameter determining the lubrication conditions is relative oil film thickness λ, defined by the following relationship [

26,

27,

28]:

where:

hmin – the minimum lubricant film thickness,

Rq1,2 – the root mean square surface finish of contacting bodies respectively.

The λ parameter also determines the type of friction occurring between mating surfaces. Lubrication conditions, and so the friction type as well, can be determined based on the λ parameter [

21,

23,

26,

27,

29] given by formula (1). Within the range of λ=(0.1), boundary friction is to be expected. In the range of relative oil film thickness of λ=(1.3), mixed friction is the dominant type, while the lubrication conditions which develop within the range of λ=<3.10> are characterised by the formation of an oil film with a thickness exceeding that of surface irregularities. Above the relative oil film thickness value of λ>10, hydrodynamic fluid friction occurs. The fact that damage occurs on the surface depends on the relationship between the minimum oil film thickness and the size of the oil contaminating particles. According to Moon [

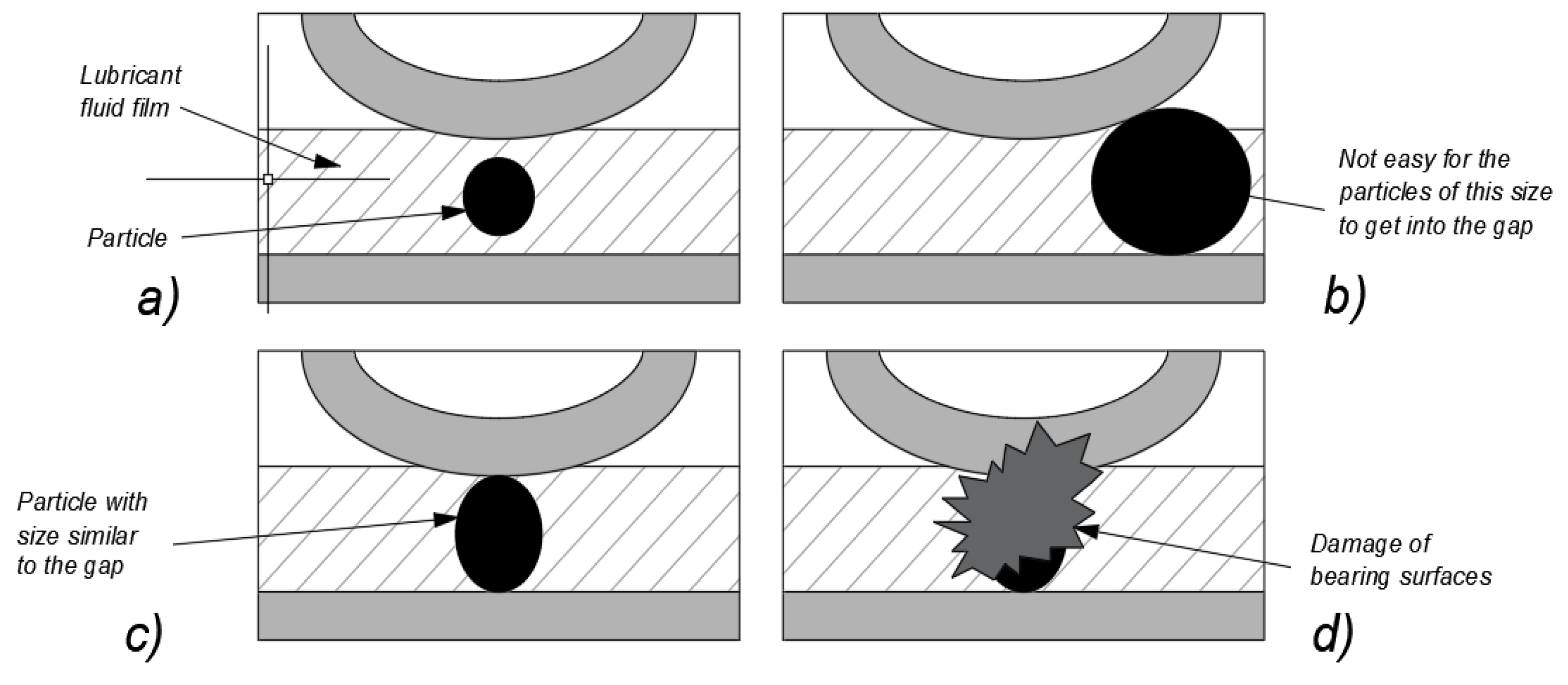

30], there are three cases (

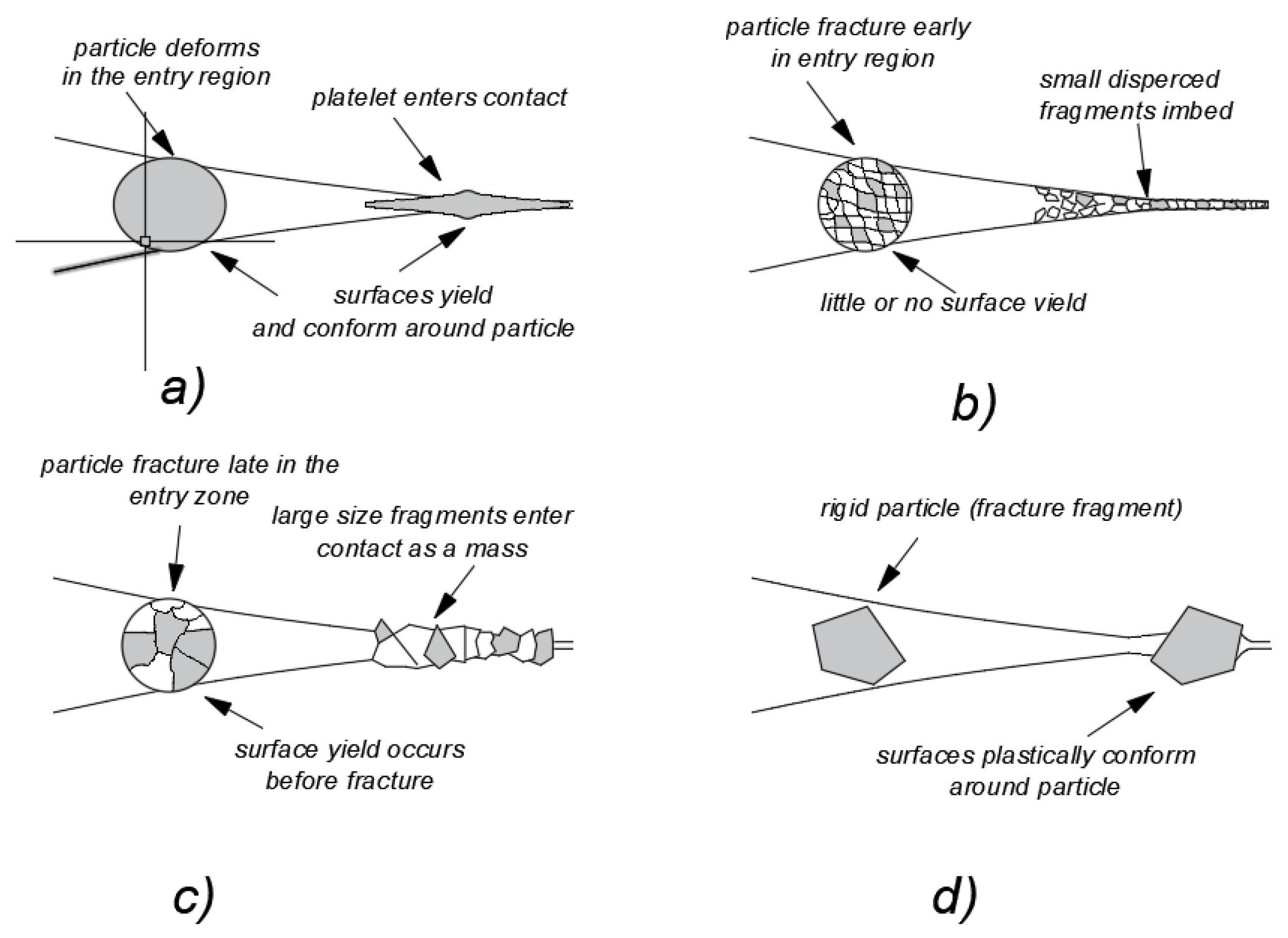

Figure 1) of such relationships:

- a)

the abrasive grain is smaller than the oil film thickness and passes through the mating area without contact,

- b)

the abrasive grain is larger than the oil film thickness and stops before the mating area,

- c)

the abrasive grain is comparable in size to the oil film thickness.

The third case corresponds to a situation where functional surfaces (e.g. bearing races or gear teeth) are subject to abrasive wear. Particles sized similarly to the oil film thickness can penetrate into the contact area where the film thickness is minimal. The load affecting a given surface is transferred to these particles, which become pressed against the mating surface and exert a cutting action. This causes surface degradation, dimensional changes, and the formation of wear products.

The research conducted by Watanabe et al. [

31] has confirmed the relationship between oil film thickness, particle size, and the rate of wear of mating surfaces. What the authors found was that the rate of wear depended largely on the film thickness to particle size ratio. The maximum wear rate was observed when this ratio equalled one, meaning that lesser wear occurred when particles were both larger and smaller than the oil film thickness.

Dwyer-Joyce et al. [

32,

33,

34] distinguish between four possible behaviour patterns displayed by the mineral particles which have already entered the mating zone between two functional surfaces:

- a)

plastic abrasive grains deform flat and flatten on mating surfaces,

- b)

abrasive grains consisting of fine mineral fractions become defragmented easily in the mating area (under conditions of lubrication, this may correspond to case a in

Figure 1),

- c)

abrasive grains consisting of large mineral fractions become slightly defragmented in the mating area (under conditions of lubrication, this may correspond to cases c and d in

Figure 1),

- d)

hard and homogeneous abrasive grains do not become defragmented in the mating area (under conditions of lubrication, this may partly correspond to case b in

Figure 1).

The characteristics of oil contaminating particles depend on the operating environment.

Table 1 contains information about the concentration, type, and size of the particles found in lubricating oil, determined by various researchers for different industries.

Figure 2.

Models of impact of mineral particles in the mating zone of functional surfaces; based on [

36].

Figure 2.

Models of impact of mineral particles in the mating zone of functional surfaces; based on [

36].

In the case of abrasives composed of soft rock grains, including coal, some other wear mechanisms may occur, including surface fatigue or delamination processes taking the form of shallow spalling [

40,

41,

42]. However, abrasive mixtures are often inhomogeneous and may contain materials of wear properties that differ significantly. One such material is hard coal, which is very often contaminated with mineral substances and may also contain interlayers of clastic rocks: sandstones, mudstones and argillaceous rocks. Immediately after extraction, hard coal should not be treated as a homogeneous component, but only as a mixture of various minerals and coal.

As mentioned in papers [

43,

44], the following was determined for non-lubricated friction nodes subject to wear in the presence of hard coal and carbonaceous claystone: the typical forms of damage due to wear mechanisms were micro-scratching and micro-fatigue; there was kaolinite and carbonaceous substance pressed into the scratches caused by surface spalling; metal particles and mineral grains could be partially neutralised by a layer of pressed-in claystone. Wieczorek et al. [

45] demonstrated surface damage caused by cutting with mineral fraction grains and flat surface spalling products for coal-mineral and mineral abrasives. Additionally, hard grains were observed to deposit in damaged surface areas, which was facilitated by the presence of carbonaceous fractions. On the other hand, for surfaces worn in the presence of carbonaceous grains alone, wear tests revealed undisturbed traces of the grinding process, suggesting the formation of unstable layers of pressed-in coal. Furthermore, the aforementioned paper introduces two models of wear in the presence of coal and coal-mineral abrasives occurring in a real-life tribological system, namely a scraper moving on the surface of a sliding plate. What has also been determined in that study is the potential impact of the presence of coal-based abrasives on the intensity of the wear process in the components of machinery transporting energy raw materials.

The impact of coal type (lithotype) on abrasive wear was analysed in study [

46]. In this respect, slight differences in wear values were found in the coal types subject to tests, and no impact of load on abrasive wear was observed. Following the tests, pressed-in coal grains were observed in the scratches resulting from grinding, and the pressed-in coal also formed layers on the surface of the samples. The resulting coal films exhibited protective and neutralising properties against the destructive action of steel particles.

Report [

47] concerning tests of oil-coal mixtures of variable non-carbon fraction content, grain size, and solid contaminant concentration reads that the most favourable wear, thermal, and friction properties were established for the pure oil lubrication variant (roller-block tester) and the lowest friction coefficient values (four-ball tester). The following has also been noted: an increase in the proportion of non-carbon fractions in solid lubricant contaminants, regardless of their particle size, significantly increased the wear of the test samples; as the size of the coal particles contained in the lubricating mixtures increased, the values of the parameters characterising friction and wear decreased; the presence of additional solid particles in the lubricating oil may, to a certain limited extent, improve resistance to scuffing.

In paper [

48], on the other hand, it has been demonstrated that gear transmissions for mining applications are operated under unfavourable boundary and mixed lubrication conditions, and the fraction of solid contaminants in their lubricating oil after 1 month comes to 0.4% at the least. Studies of the oil contaminants found in transmissions used in hard coal mines [

49] showed that the diameter of the contaminating particles ranged from 0 to 10 μm (an average particle size being approx. 2.5 μm) and that these particles were composed mainly of coal, SiO

2 and iron particles.

Ostrikov et al. [

50] observed in their study that the addition of carbon black significantly improved the lubricity of mineral oil, enhancing its properties, while it activated wear processes in oil without additives. The lubricity of pure oil with additives increased by more than 30% once it had been exposed to ultrasounds, which resulted from the activation of its dispersion medium. It was further noted that small amounts of engine fuel combustion products which penetrated oil increased the lubricity of oil enriched with additives, similarly to other carbon-based additives.

In paper [

51], on the other hand, Bölter argues that, as the content of carbon black increases in oil, the coefficient of friction decreases, while surface properties after the wearing-in process deteriorate as the content of carbon black grows. The surfaces of components operated in oils containing carbon black were found to show less damage, and their superficial layers displayed a lower content of anti-wear additives, which may suggest them being bonded by the particles of carbon black.

Pang et al. [

52] conducted research on the effects of contamination of solid mining transmission lubricants with coal and rock dust on the wear of steel. Pulverised coal and silica dust with a grain size of approx. 180 µm and 75 µm were used in the experiments. The finding of that study is that wear is considerably dependent on the type of contaminants and their combination, and a small amount of pulverised coal exerts a beneficial effect on account of its lubricating properties, while higher concentrations significantly increase wear. What this study has also demonstrated is the lower coefficients of friction established for oil contaminated with anthracite coal dust (COF=0.065) compared to oil contaminated with a mixture of coal and silica dust (COF=0.105). Another conclusion derived from that study is that the cyclic loads attributable to the presence of coal particles lead to dynamic changes in surface stresses in alloy steel, resulting in local stress concentrations which promote initiation of microcracks, and as the friction process progresses, these microcracks propagate, leading to the gradual detachment of material particles and the formation of wear products. The aforementioned study has also revealed that the presence of reactive elements, such as phosphorus (P) and sulphur (S), contained in coal-derived contaminants significantly intensifies surface degradation by accelerating oxidation processes.

In their respective papers, Tlotleng et al. [

53], Xia et al. [

54], Yarali et al. [

55], Shao et al. [

56], Shi et al. [

57], Terva, et al. [

58], Wang et al. [

59], Labaš et al. [

60], Ngoy et al. [

61], Wells et al. [

62,

63], as well as Petrica et al. [

64] have confirmed the major abrasive effect of hard coal, leading to considerable wear of mining tools and equipment.

On the other hand, based on the results obtained from a numerical model taking into account both the plastic deformation of particles and the forces generated by grease under pressure, as well as the distribution of the heat attributable to friction, including the values of flash temperature, as it is commonly referred to, Niklas [

65] has detected a significant effect of thermal load on the cracking and spalling in the superficial layer of surfaces lubricated with oil contaminated with soft particles. Thermal load is generated by way of the processes of forcing through and compression of mineral material grains over the course of elastohydrodynamic contact, leading to a considerable short-term local temperature increase due to friction (a phenomenon known as flash temperature).

According to the same author [

66], the peak flash temperature occurs in less than one millisecond, depending on the rolling and sliding velocity. This phenomenon is most powerful just before the particle enters the central contact zone, which determines the location where the maximum temperature is observed. The distribution of heat between the particle and counterfaces is directly dependent on their thermal properties. Typically, most of the heat is transferred to the surface to which the particle adheres. It has also been noticed that the larger and/or harder the particle, the smaller the temperature difference between the counterfaces. The main factor affecting flash temperature is the particle size, not its hardness. The difference in flash temperature between particles of 5 μm and 20 μm in size, made of the same material, can exceed 1,000°C (

Table 2).

Frictional heating generates thermal stresses which, in numerous cases, significantly exceed mechanical stresses [

67,

68]. This phenomenon raises the risk of surface damage, shifting the high-risk zone of plastic deformation closer to counterfaces. Unlike hard particles, which retain their shape, soft particles flatten, thus increasing the friction surface considerably. For this reason, and on account of the predominance of thermal stresses, soft particles can cause serious damage.

Unfortunately, in many cases, oil contamination cannot be avoided in lubricated friction nodes due to sealing system leaks, the use of vents, and the cyclical processes of heating and shrinking of machine bodies [

69]. This is a typical mining situation, encountered particularly in hard coal mines, which, despite the use of advanced materials and heat treatment technologies dedicated to this industry [

70,

71], leads to critical damage, which manifests itself as pitting or abrasive wear, and consequently to the decommissioning of the affected equipment.

The main objective of the studies discussed in this paper was to identify the quantitative and qualitative impact of mineral oil contaminants in the form of pulverised hard coal and carbonaceous claystone grains on the surface wear mechanisms in heat-treated 42CrMo-4 steel. The impact of the oil mixtures containing coal-mineral fractions, especially carbonaceous claystones, has not been explained sufficiently enough. A review of the literature on the subject has revealed that it provides no results of studies on the mechanisms of steel surface damage under conditions of lubrication with oil containing claystone and coal-based abrasives, which makes the subject addressed in the paper a novelty, given the state of the art.

2. Materials and Methods

Tests enabling quantitative and qualitative determination of wear of mating elements were conducted at an Amsler roller-type test rig [

72]. The test assembly consisted of two cylindrical rings contacting each other with their cylindrical surfaces, loaded with a constant radial force, and rotating in such a way as to cause counter-motion of the samples.

The wear tests at the roller test rig proceeded under the following conditions:

- −

friction type – rolling with slide,

- −

load – constant radial force of F = 490 N,

- −

sample contact area width – b = 10 mm,

- −

rotational speed – n1 = 200 min-1,

- −

sample circumferential speed – vp = 0.8 m·s-1,

- −

counter-sample circumferential speed – vpp = 0.92 m·s-1,

- −

counter-motion of samples.

The samples and counter-samples were made of the 42CrMo-4 steel (quenched and tempered at a low temperature of 160°C) with a surface hardness of 56 HRC (their chemical composition has been provided in

Table 3). After the heat treatment, this steel displayed a structure of tempered martensite.

Both the samples and counter-samples were of identical dimensions: outer diameter of ϕ40, hole diameter of ϕ16, and sample width of 10 mm. Mass loss measurements were performed after 5, 20, 50, and 80 minutes of co-operation of the rings tested. Before the wear test began and after each friction cycle, the mass of the sample (having been carefully cleaned and dried) was determined five times using an analytical balance characterised by a measurement accuracy of 0.1 mg. Student’s t-test was conducted to establish the measurement uncertainty for the samples.

Pure VG 220 mineral oil and 5 oil mixtures with 1% mass fraction of the coal and claystone particles examined (these minerals have been described in detail in

Section 3.1 of the paper) were used in the tests. The oil-coal and oil-claystone mixture variants taken into account have been listed in

Table 4.

Table 5 provides a compilation of the parameters characterising pure oil and, due to the very similar results obtained, the average viscosity values obtained for Variants 1÷5 of the mixtures examined. For purposes of the study, with reference to

Table 1 (Various group), it was assumed that the range of diameters of the mineral contaminant particles to be added to pure oil would be 0÷100 μm.

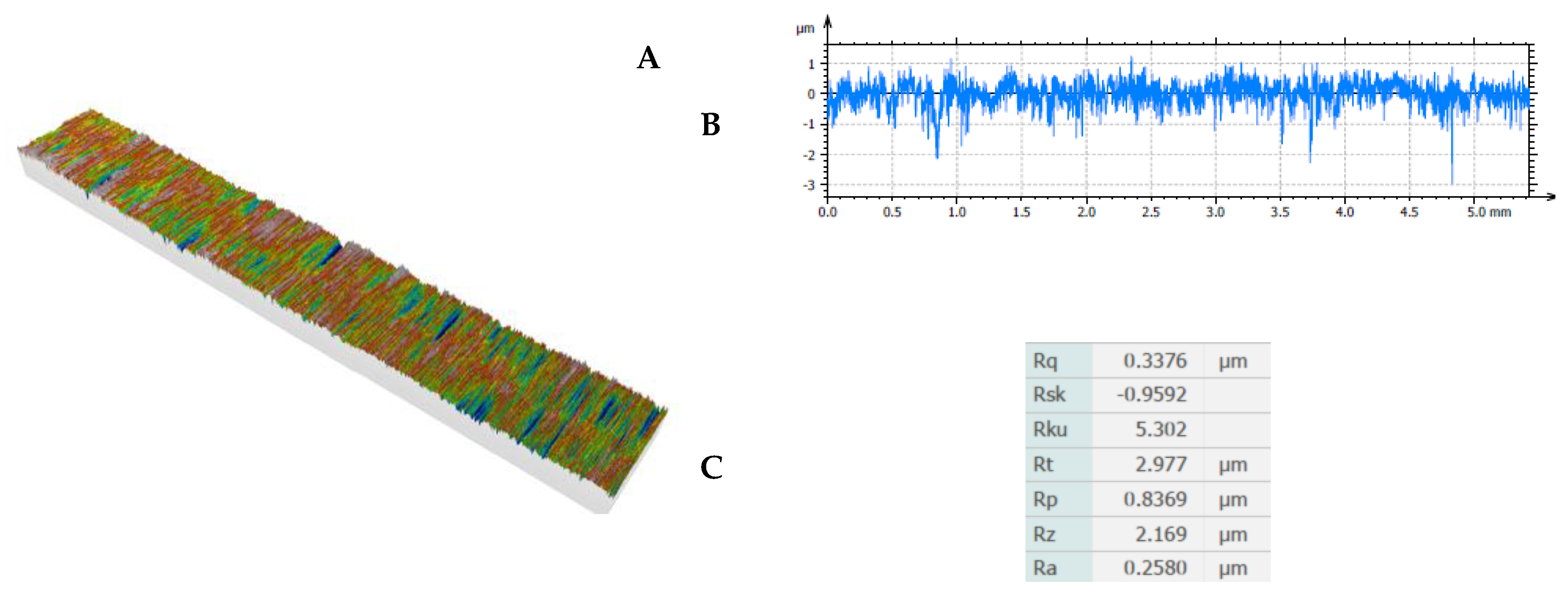

Additionally, in order to characterise the conditions of lubrication of the test samples, the following was determined:

- −

surface roughness (measurement results provided in

Figure 3);

- −

oil film thickness; the methodology employed to calculate the oil film thickness in the mating rings is described in ISO/TR 15144-1:2014 (E) [

73]; the calculation results obtained for the roller-roller combination have been provided in

Table 6;

- −

Hertzian surface pressures and the location of the maximum pressure point (calculation results compiled in

Table 7).

Based on the lubricating film thickness calculations, one can conclude that the ring-ring friction pair tested was subject to mixed friction conditions.

The chemical composition of the coal abrasives was determined by X-ray fluorescence (WD-XRF) using a Rigaku ZSX Primus II WD-XRF spectrometer (Rh lamp). The samples were dried, and then the relevant loss on ignition was determined at the temperature of 1,025°C. Roasted to obtain a constant mass, the samples were melted using an off-the-shelf mixture of lithium tetraborate, lithium metaborate, and lithium bromide (66.67%, 32.83%, and 0.5%, respectively) characterised by a flux purity suitable for XRF (from Spex). The spectrum was analysed qualitatively by identifying spectral lines and determining their possible coincidences. On such a basis, analytical lines were selected. Semi-quantitative analysis was performed using the SQX Calculation program (by the fundamental parameters method). The analysis was performed in the fluorine-uranium (F-U) range, and the contents of the elements thus determined were normalised to 100%.

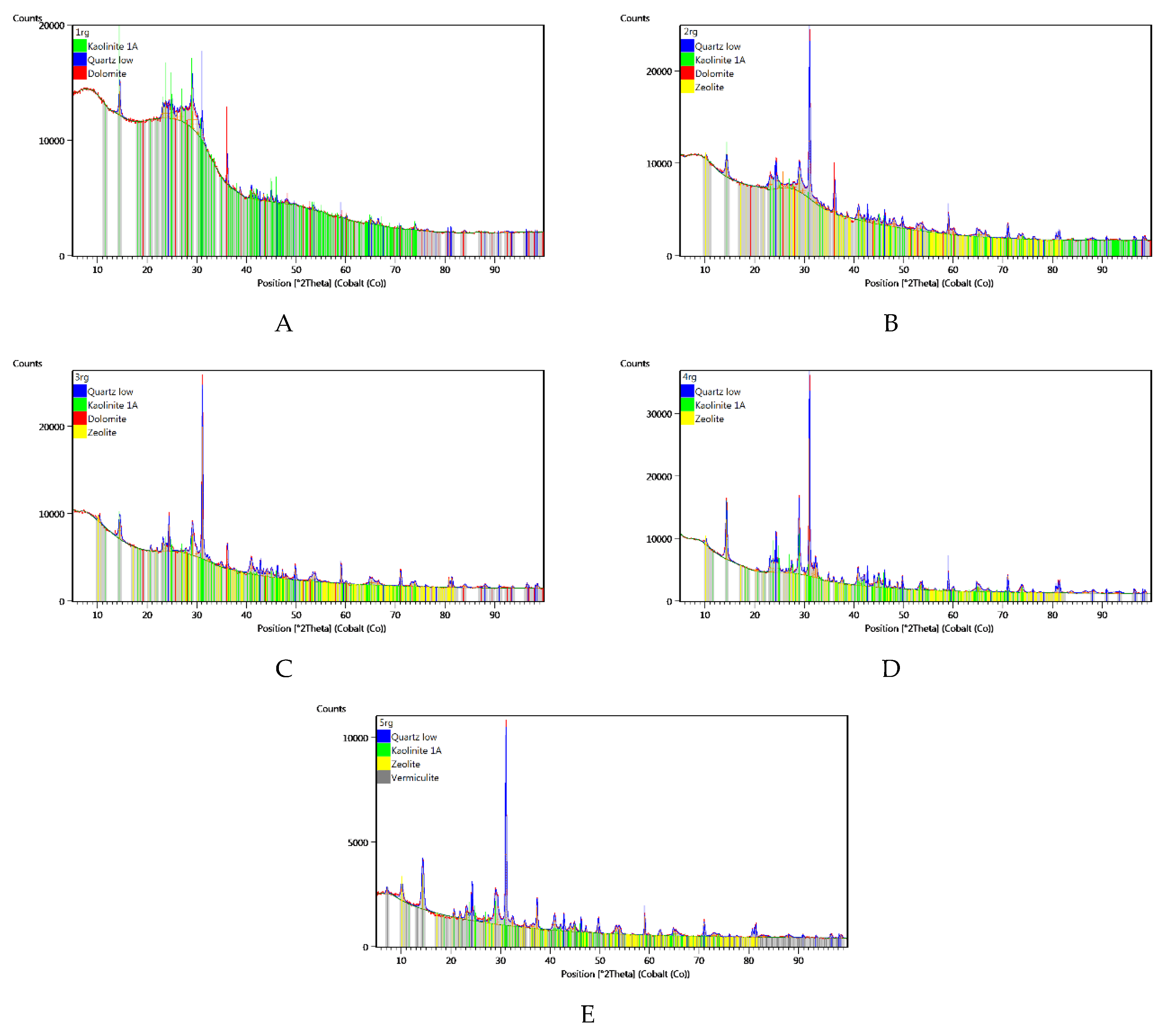

The phase composition of the coal abrasives was studied using a Panalytical X’Pert PRO MPD X-ray diffractometer featuring a cobalt anode X-ray tube (λKα = 0.179 nm) and a PIXcel 3D detector. The diffractograms were recorded in the Bragg-Brentano geometry with the angles ranging at 5–100o 2Theta with a step of 0.026o and a counting time of 80 seconds per step. Qualitative X-ray phase analysis was performed using the HighScore Plus (v. 3.0e) software and the PAN-ICSD dedicated database of inorganic crystal structures.

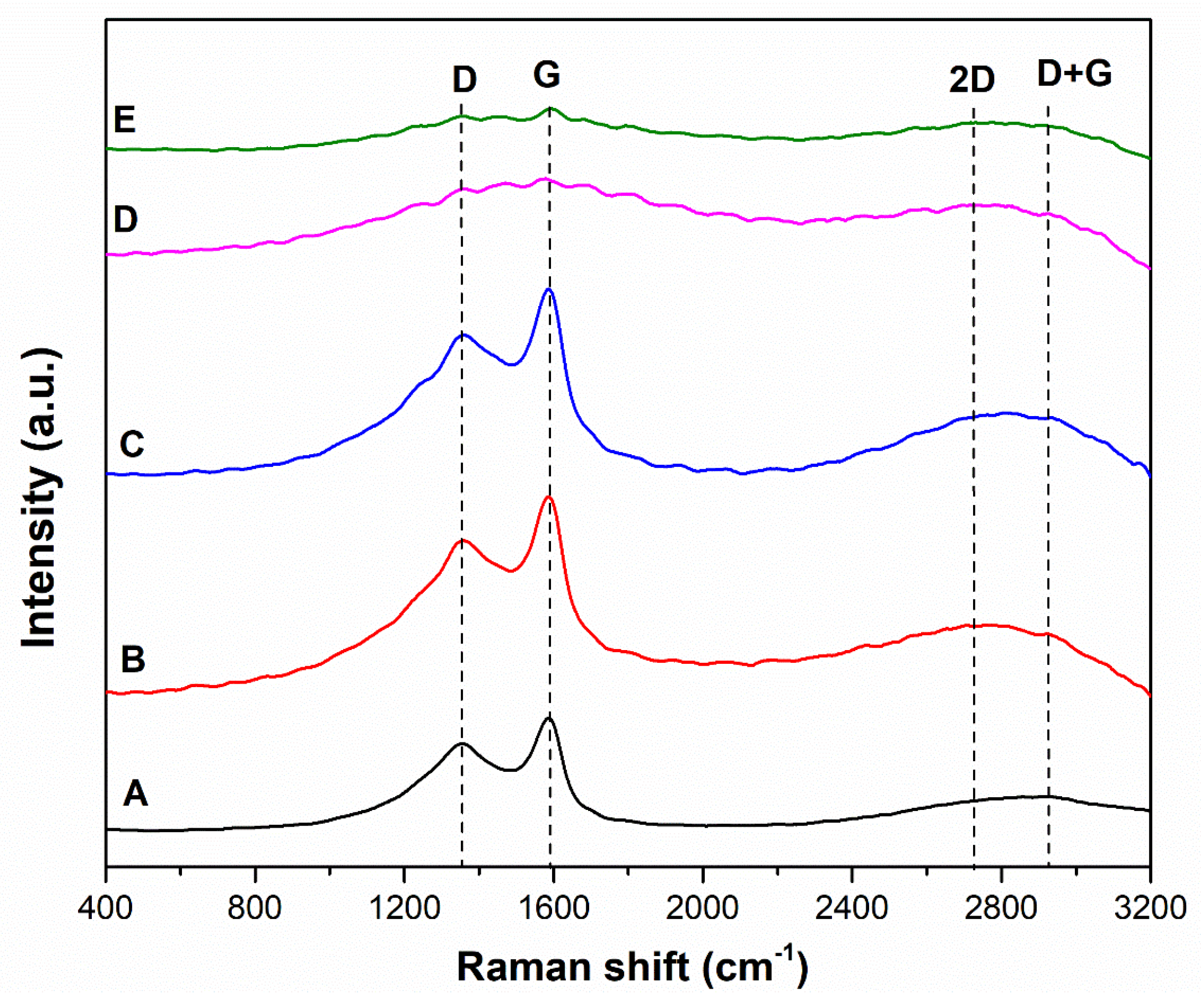

Spectroscopic analysis of the minerals tested was performed using an inVia Reflex Raman spectrometer from Renishaw featuring a Leica Research Grade confocal microscope capable of observing samples in reflected and transmitted light. Excitation was performed using a 50 mW ion-argon laser beam with a wavelength of λ = 514 nm. Sample measurements were recorded in a wide wave number range from 50 to 3,200 cm-1.

The surface of the samples was observed using an Axia ChemiSEM scanning electron microscope (SEM) enabling secondary electron (SE) detection at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV and a magnification range of 60÷1,000x. The chemical composition of the test material in the micro-areas was subject to a qualitative analysis by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. Prior to testing, the samples were coated with a thin film of gold to ensure electrical charge dissipation during the tests.

4. Discussion

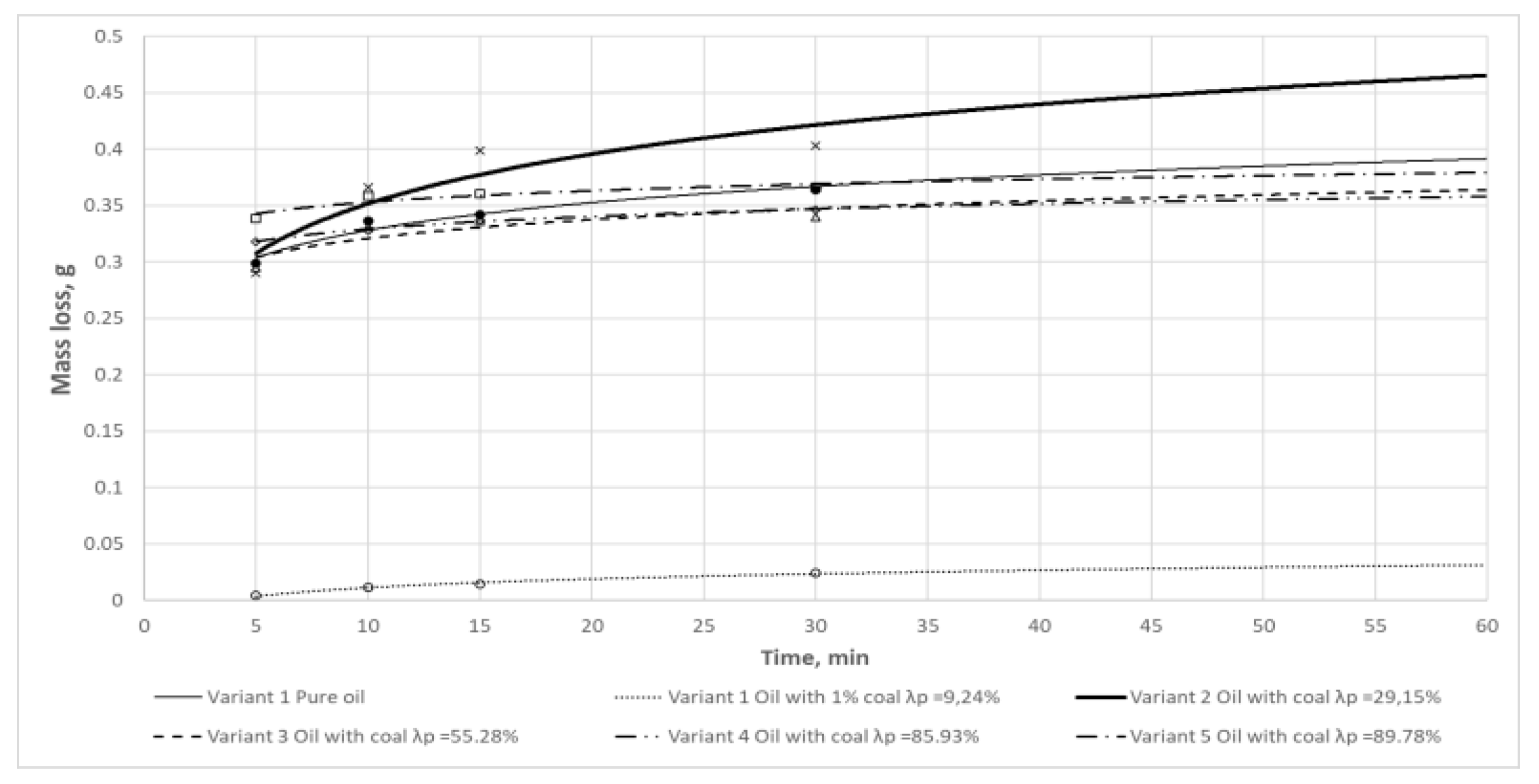

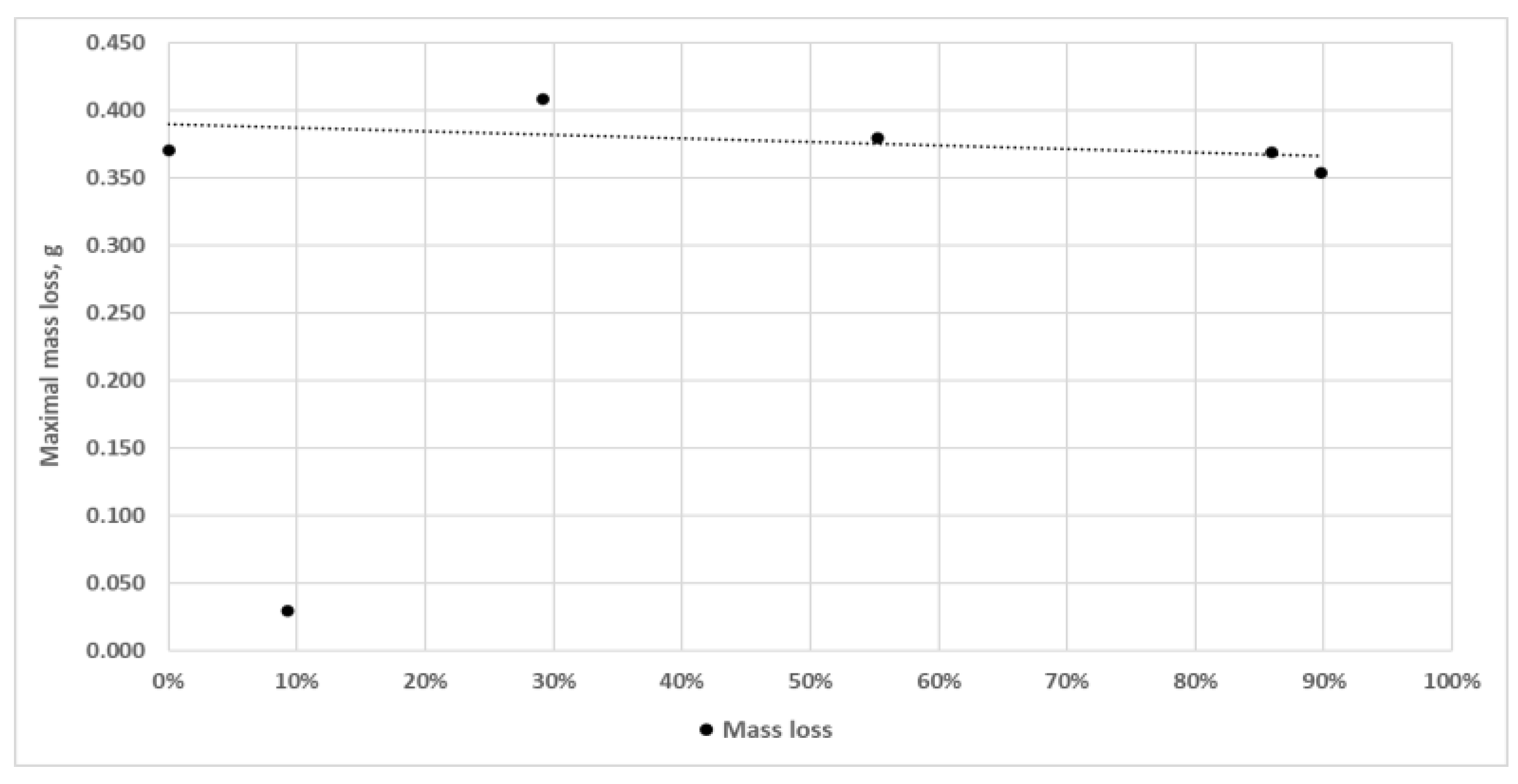

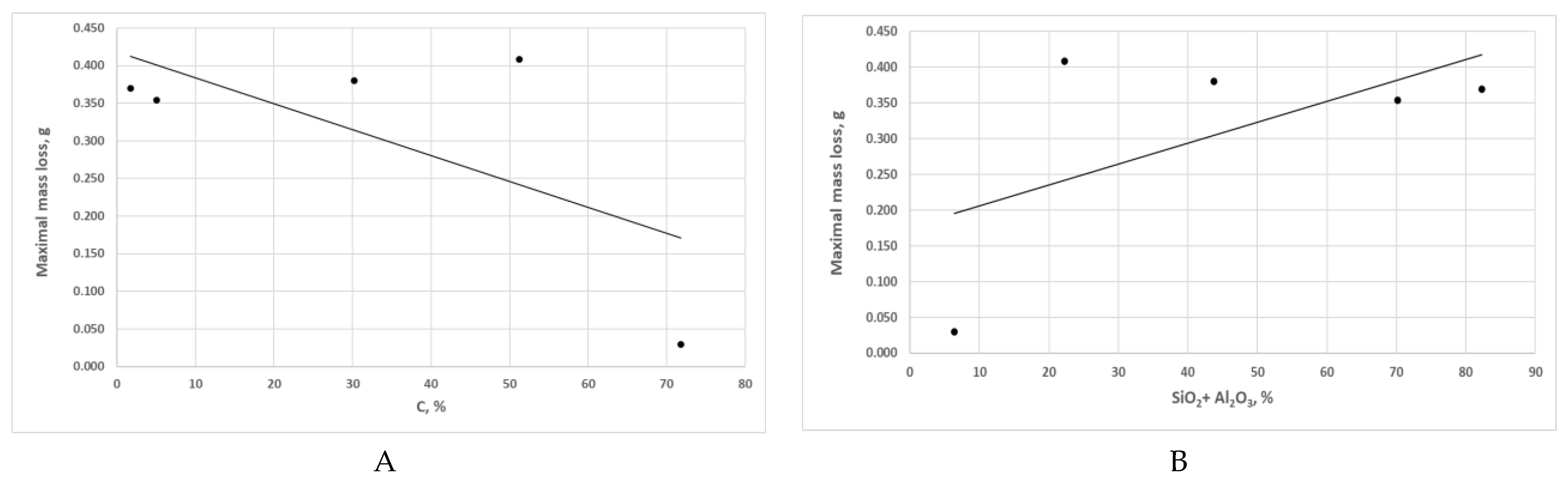

Having analysed

Figure 8, showing the maximum mass loss values in a function of the percentage share of non-combustible fractions λ

P in carbonaceous contaminants, one can notice that there is no explicit functional relationship between wear and the share of ash in coal (λ

P), while a clear local minimum of mass loss is observed for λ

P = 9.24%. It should be added that the differences in the mass loss determined for the other cases are insignificant.

As aforementioned, Variant 1 is characterised by a large variation in mass loss values compared to the other variants, i.e. Variants 0 and 2÷5. As

Table 8 implies, Variant 1 was characterised by the highest degree of carbonisation, the lowest content of hard mineral fractions, and a relatively high sulphur content. It is such a combination of properties that makes this abrasive material a low-abrasion type.

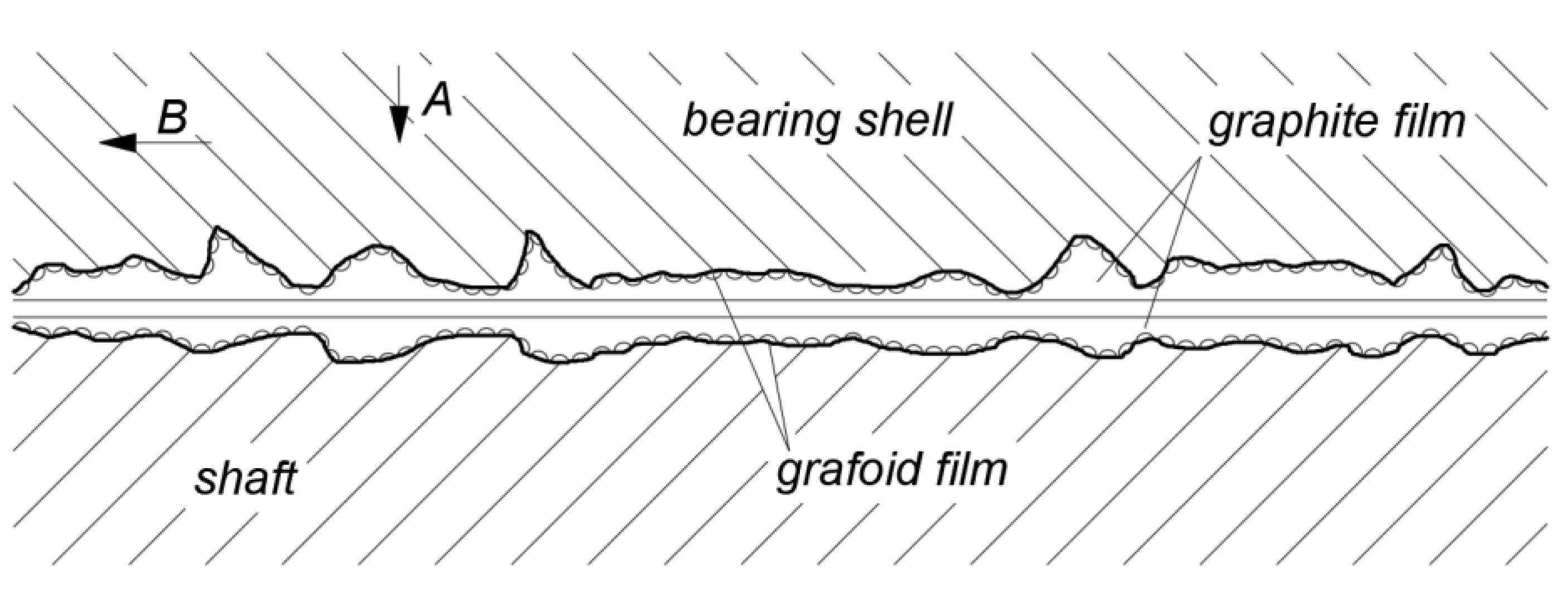

The minimal wear observed for Variant 1 can be explained primarily by its capacity (similar to graphite) to form carbonaceous films on the irregularities of mating surfaces under mixed friction conditions. It is also noteworthy that the Raman spectroscopy tests have revealed a distinct G-mode for this variant within the Raman shift range of 1,590, which is characteristic of ordered graphite structures.

Graphite is a soft material which displays good lubricating properties, significant cleavability, and high thermal resistance. Graphite of both natural and synthetic origin is used for lubrication purposes, their properties being similar. A characteristic property of graphite is its high chemical resistance. It also exhibits high thermal resistance, which makes it suitable for application at temperatures up to 550°C.

Another advantage of graphite, used as a wear-reducing agent, is its capacity to adsorb onto metallic surfaces [

11]. This property is attributable to the effect of both electrostatic forces and the van der Waals forces. Additionally, when graphite particles are introduced between mating surfaces, they mechanically fill surface irregularities. Consequently, a strongly adhering film with a thickness of 200÷1,000 μm, called graphoid, is formed on the mating surfaces, preventing dry friction of these surfaces. Graphoid films are physically bound to the friction surface by oxides. Under boundary or mixed friction conditions, graphite particles are additionally arranged along the oriented surface. The formation of graphoid on surfaces subject to friction reduces the wear of metallic parts and decreases frictional resistance. Graphoid prevents dry friction between mating surfaces.

Under conditions of insufficient lubrication, where direct contact between surface irregularities in mating elements is possible, the graphite particles contained in the liquid lubricant are physically adsorbed onto the metal surface, forming a sufficiently durable graphoid film. Further graphite particles are attracted to this film until the depressions in the irregularities have been filled and the surface smoothed. The reciprocal displacement of the surfaces takes place in the graphite layer along what is referred to as a “graphite mirror.” The resulting graphoid-graphite film (

Figure 20) is characterised by good adsorption properties, as a result of which the lubricant molecules are strongly attracted and form a sufficiently durable lubricating film, thus improving the operating conditions of the friction node. The graphoid film increases the lubricity of a given lubricant on account of its greater oil adsorption capacity compared to metals. It should also be added that, due to their low shear strength, the graphite films covering the irregularities of mating surfaces reduce the friction forces associated with the interaction of the peaks of these irregularities.

It is highly likely that, in the case of Variant 1, coal particles were also adsorbed onto the surface of the samples, having backfilled the irregularities of this surface. The adsorption of coal particles onto the surface of the samples is associated with its properties, specifically the ability of coal to become plastic when heated to a temperature of approx. 350÷500°C [

77,

78,

79]. In terms of colloid chemistry, the plastic state of coal constitutes a system composed of a dispersing medium and a dispersed medium. It has been proved that, once heated, hard coals decompose, first entering a softened state, then a plastic state [

80,

81], and then solidifying into a product with an altered structure, devoid of gaseous and liquid parts [

82,

83]. Over the course of the tests performed, as a result of friction processes, the abrasive material could be exposed to high temperatures. Its impact is insignificant on a macro scale, but on a micro scale, the temperature could locally reach a level that enabled the coal abrasive to soften, causing it to be pressed into the scratches formed by the effect of wear products, and leading to the formation of a film showing properties similar to the graphoid-graphite film described above.

The formation of a coat composed of pressed-in carbonaceous particles causes separation of the mating surfaces to a certain extent, preventing mutual contact between their vertices. The surface roughness reduction resulting from the formation of that coat has a positive effect on the lubrication conditions at the point of contact and may, therefore, be the reason for the mass loss reduction observed in the case of Variant 1. The improvement in lubrication conditions resulting from the formation of the carbonaceous layer most likely led to a reduction in the coefficient of friction (COF), which conforms with the results of the studies by Pang et al. [

52] and Bölter [

51].

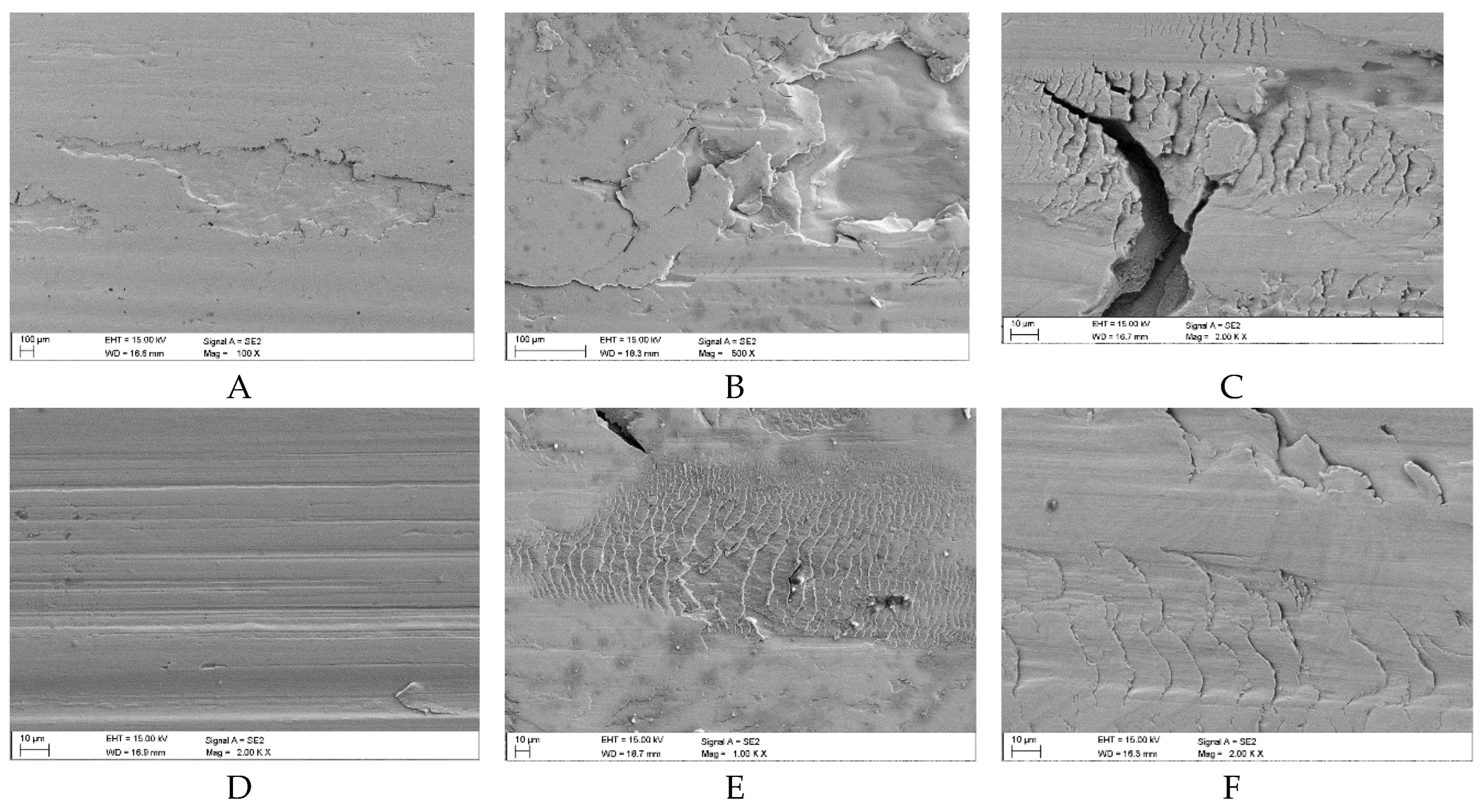

Over the course of the wear process taking place on the surface of the samples lubricated with oil containing coal abrasives with an ash content of λP = 29.15÷89.78%, similarly to Variant 1, films of pressed-in coal-mineral material were also most likely formed. The formation of these films is indicated by their residues visible in

Figure 14 C÷E,

Figure 15B and

Figure 16B. Some heterogeneous fragments of the coal-mineral film are particularly visible in

Figure 14D. The share of hard fractions in these abrasives could have caused these films to be unstable and unable to separate the mating surface irregularities under mixed friction conditions (cf.

Table 6). The share of non-carbonaceous fractions probably reduces the adsorption properties of coal particles, which they manifest on the surface of samples, hence the significantly reduced durability of the films in question. This resulted in the separation of fragments of the vertices of the surface irregularities and caused them to scratch the surfaces (as shown in

Figure 14A,

Figure 15A and

Figure 16A).

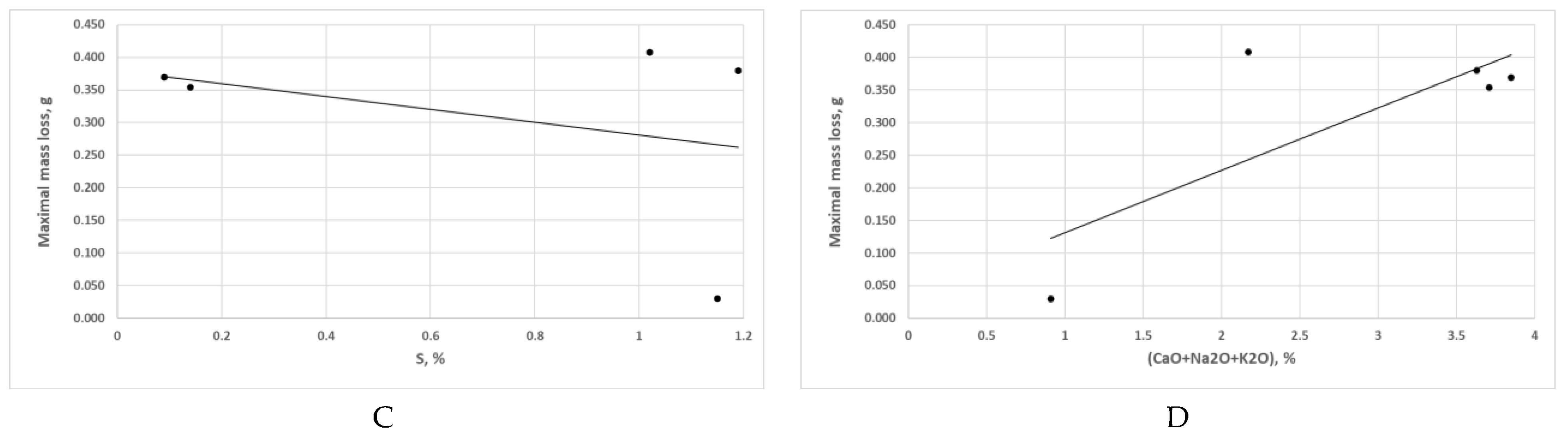

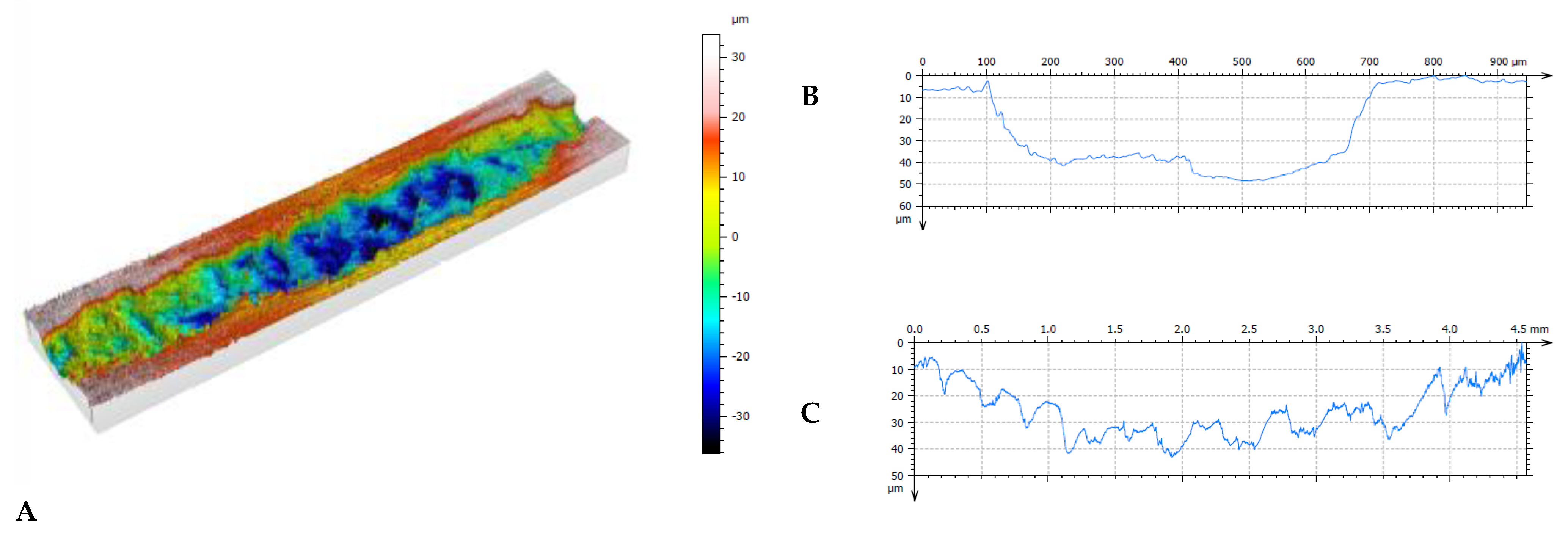

It should be noted at this point that the predominant form of surface defect in the 42CrMo-4 steel is spalling. In the case of Variant 1, the spalls were approx. 10 μm deep, while in the other cases, the spalling depths ranged at approx. 40÷50 μm, which was consistent with the location of the zone of the highest contact stresses (cf.

Table 7). As

Figure 7 implies, the greatest increase in mass loss and the associated formation of spalling were observed during the wearing-in of the samples. In this phase of the wear test, the strongest thermal effect resulting from the friction of surfaces, still of relatively high roughness at this stage, is typically observed.

The surface spalling observed after the wear tests of Variants 2÷5 was most likely caused by the combined effect of contact stresses and thermal stresses. The factors which substantiate the foregoing causes are the depth of the spalling which corresponds to the location of the maximum contact stresses and the presence of unbonded coal-mineral particles which, under mixed friction conditions, are pressed into the contact area, flattened, and heated to high temperatures due to friction. This leads to an increase in flash temperature [

65,

66] and local surface heating (cf.

Table 2) which, when combined with contact stresses, can cause rapid surface degradation by way of spalling. The heating of the surface during the tests was facilitated by the considerable mutual slipping, attributable to the counter-motion of the samples, triggered in the zone of contact between irregularities. This process may also have benefited from the bonding of the anti-wear (AW) additives contained in the lubricating oil by coal-mineral grains, as demonstrated by Pang et al. [

52].

As aforementioned, the depth of spalling determined for Variant 1 is significantly smaller (approx. four times) than that observed for Variants 2÷5. This difference can be explained by the formation of a layer of pure coal absorbed on the surface of the steel samples, most likely leading to an increase in the relative thickness of the oil film. It is most probable that an increase in the relative thickness of the said oil film reduces friction, thus lowering the flash temperature, and may increase the suppression of contact stress variability, which implies shallower crack propagation into the surface layer of the samples.

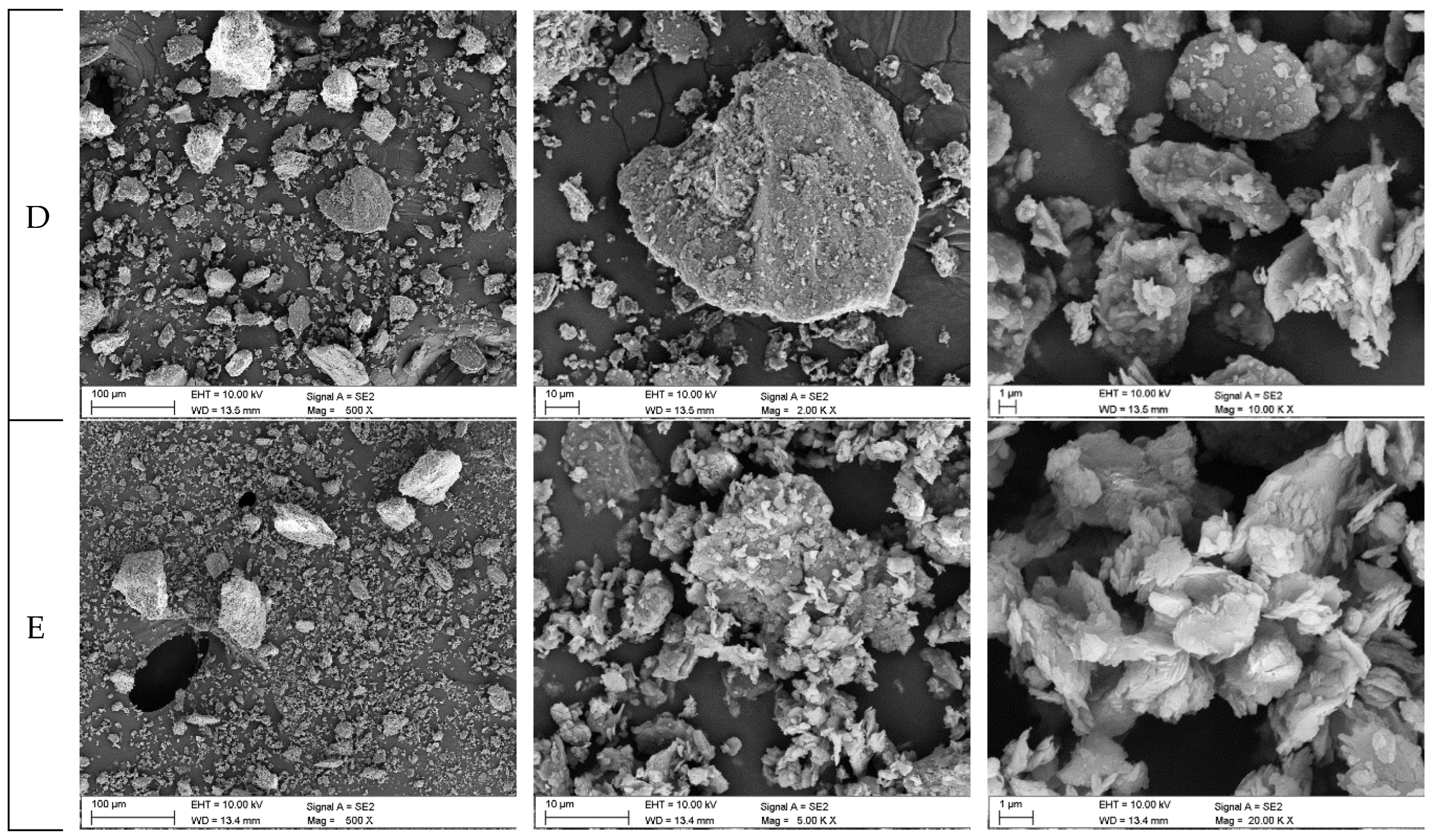

On the other hand, the declining wear observed when studying Variants 2÷5 as the ash content increased in coal was most likely due to the tendency of claystone grains to break down into smaller particles (cf.

Figure 6). According to Nikas [

67,

68], it is the size of the carbonaceous particle, rather than its hardness, that has a decisive effect on the flash temperature. Consequently, the susceptibility to disintegration of claystone particles may locally cause lower temperatures as the particles are being pressed through the contact area of the mating surfaces.

The surface spalling over the course of the lubrication with pure oil (Variant 0) was most likely also attributable to the combined effect of contact stresses and thermal stresses. It was only under the impact of mixed friction that contact occurred between the vertices of surface irregularities, which could deform plastically, heat up, and cause surface cracks under such conditions.

5. Conclusions

The following conclusions have been drawn with reference to the studies of the wear of the 42CrMo-4 steel lubricated with mineral oil containing carbonaceous and argillaceous contaminants under mixed friction conditions:

1. Analysis has revealed no clear functional correlation between the mass loss in the samples and the share of non-combustible fractions (λP) in the carbonaceous contaminants.

2. Variant 1, which stood out for the highest degree of carbonisation and low mineral fraction content, showed the lowest mass loss among all the variants examined. This is most likely attributable to the presence of carbonaceous particles with a structure similar to graphite, as confirmed by the Raman spectroscopy results.

3. In the case of Variant 1, the favourable tribological properties are most likely due to the formation of a thin carbonaceous film during the test, which improves lubrication conditions. This film is formed as a result of the adsorption of coal particles onto the metal surface as well as their pressing-in and plasticisation under the conditions of elevated temperature and contact stresses.

4. The carbonaceous film reduces the direct contact between irregularities and causes surface roughness to decline, which consequently leads to a reduction in surface wear and spalling depth.

5. The depth of surface spalling observed when studying Variant 1 was approx. 10 µm, which corresponded to ca. 25% of the depth of spalling established for the remaining variants (2÷5). The reduced susceptibility to surface spalling, as observed in that case, can be explained by the improved attenuating properties of the carbonaceous film formed as well as lower thermal and mechanical stresses, most likely resulting from the flash temperature reduction in the contact area.

6. In Variants 2÷5, despite the formation of the films of pressed-in coal-mineral material, the presence of hard fractions weakened their durability and tendency to become fragmented.

7. High local temperature and the size of coal particles (rather than their hardness) are critical for wear intensity. Smaller claystone particles, prone to disintegration, may have contributed to lower flash temperature and lower wear in some cases.

8. In the absence of coal-based additives, lubrication with pure oil did not prevent direct contact between surface irregularities, leading to their heating, plastic deformation, and crack initiation.

Figure 1.

Potential relationships between the minimum oil film thickness and the size of oil contaminating particles; based on [

30].

Figure 1.

Potential relationships between the minimum oil film thickness and the size of oil contaminating particles; based on [

30].

Figure 3.

Results of surface roughness measurements.

Figure 3.

Results of surface roughness measurements.

Figure 4.

XRD test results for the abrasives studied: A – coal with ash content of λp = 9.24%; B – coal with ash content of λp = 29.15%; C – coal with ash content of λp = 55.28%; D – claystone with ash content of λp = 89.78%; E – claystone with ash content of λp = 85.93%.

Figure 4.

XRD test results for the abrasives studied: A – coal with ash content of λp = 9.24%; B – coal with ash content of λp = 29.15%; C – coal with ash content of λp = 55.28%; D – claystone with ash content of λp = 89.78%; E – claystone with ash content of λp = 85.93%.

Figure 5.

Raman spectra of the abrasives studied: A – coal with ash content of λp = 9.24%; B – coal with ash content of λp = 29.15%; C – coal with ash content of λp = 55.28%; D – claystone with ash content of λp = 85,93%; E – claystone with ash content of λp = 89,78%.

Figure 5.

Raman spectra of the abrasives studied: A – coal with ash content of λp = 9.24%; B – coal with ash content of λp = 29.15%; C – coal with ash content of λp = 55.28%; D – claystone with ash content of λp = 85,93%; E – claystone with ash content of λp = 89,78%.

Figure 6.

Grains of the abrasives studied (SEM image): A – coal with ash content of λp = 9.24%; B – coal with ash content of λp = 29.15%; C – coal with ash content of λp = 55.28%; D – claystone with ash content of λp = 85.93%; E – claystone with ash content of λp = 89.78%.

Figure 6.

Grains of the abrasives studied (SEM image): A – coal with ash content of λp = 9.24%; B – coal with ash content of λp = 29.15%; C – coal with ash content of λp = 55.28%; D – claystone with ash content of λp = 85.93%; E – claystone with ash content of λp = 89.78%.

Figure 7.

Mass loss determined for samples lubricated with oils containing carbonaceous contaminants in a function of time.

Figure 7.

Mass loss determined for samples lubricated with oils containing carbonaceous contaminants in a function of time.

Figure 8.

Maximum mass loss values determined for the variants studied and the corresponding percentage share of non-combustible fraction λP in carbonaceous contaminants; the regression line takes into account the wear results obtained for Variants 0 and 2÷5.

Figure 8.

Maximum mass loss values determined for the variants studied and the corresponding percentage share of non-combustible fraction λP in carbonaceous contaminants; the regression line takes into account the wear results obtained for Variants 0 and 2÷5.

Figure 9.

Effect of the share of individual mineral fractions in the abrasives based on hard coal and carbonaceous claystone on the mass loss in test samples: A – carbonaceous fraction, B – hard mineral fraction, C – sulphur, D – alkali metal oxide fraction.

Figure 9.

Effect of the share of individual mineral fractions in the abrasives based on hard coal and carbonaceous claystone on the mass loss in test samples: A – carbonaceous fraction, B – hard mineral fraction, C – sulphur, D – alkali metal oxide fraction.

Figure 10.

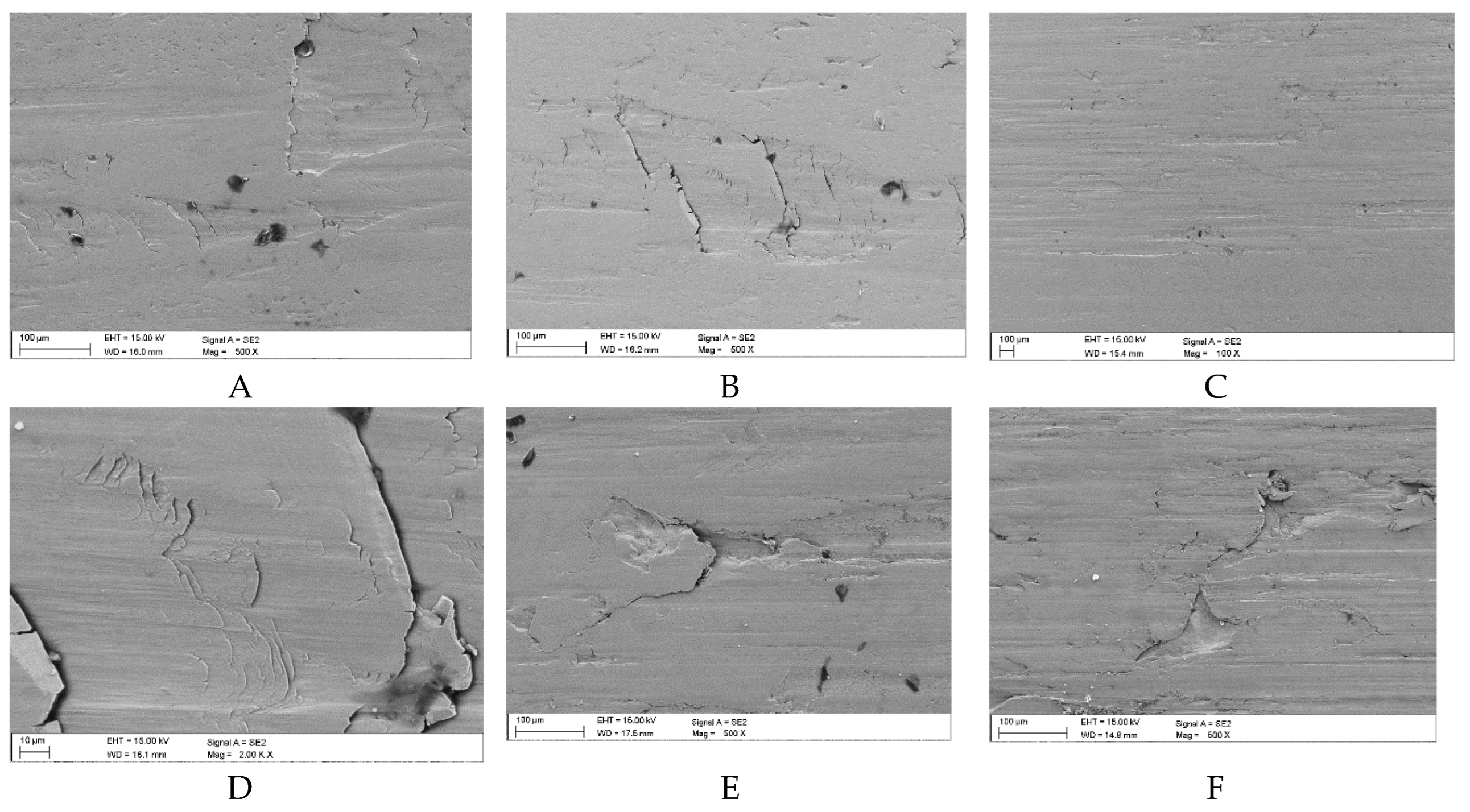

Images of the surface damage of the samples following wear tests in the presence of pure oil (Variant 0): A, B – surface spalling (delamination), C – surface cracking in the vicinity of pitting cracks, D – surface scratches, E, F – initial stages of pitting (SEM).

Figure 10.

Images of the surface damage of the samples following wear tests in the presence of pure oil (Variant 0): A, B – surface spalling (delamination), C – surface cracking in the vicinity of pitting cracks, D – surface scratches, E, F – initial stages of pitting (SEM).

Figure 11.

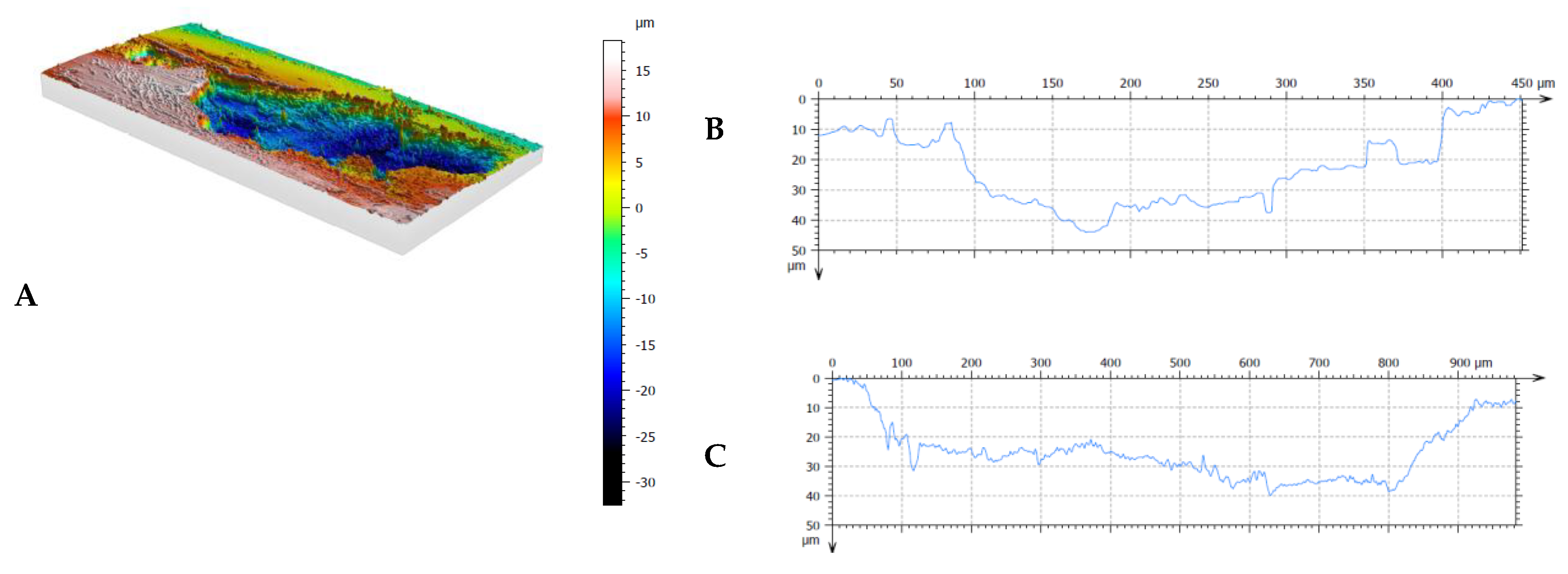

Results of profilometric tests of the surface of steel lubricated with pure oil (Variant 0) in the area of spalling: A – 3D image of spalling, B – cross-section of spalling area, C – longitudinal section of spalling area.

Figure 11.

Results of profilometric tests of the surface of steel lubricated with pure oil (Variant 0) in the area of spalling: A – 3D image of spalling, B – cross-section of spalling area, C – longitudinal section of spalling area.

Figure 12.

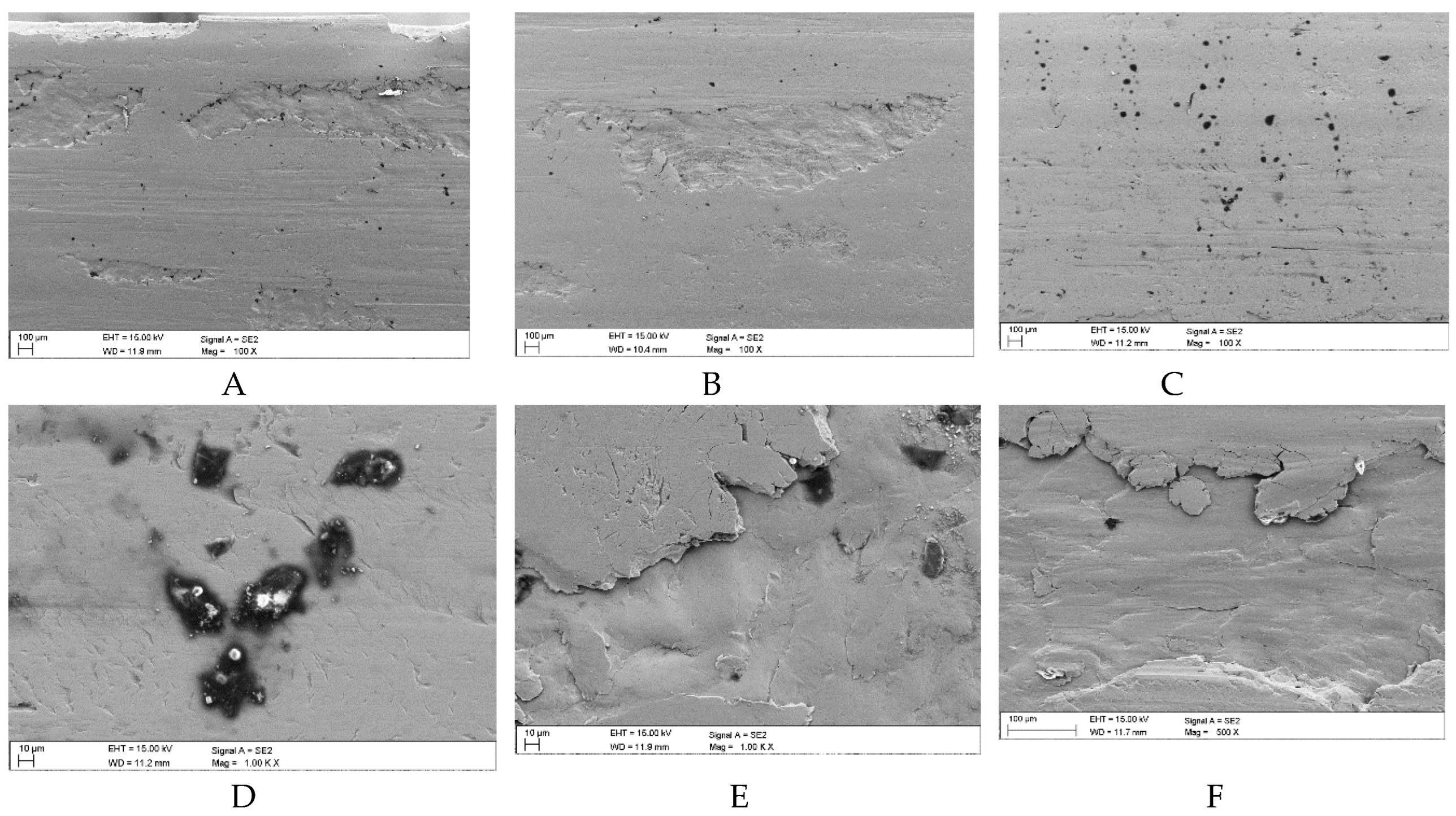

Sample surface defects following wear tests in the presence of a mixture of oil and coal with an ash content of λp = 9.24% (Variant 1): A, B – surface spalling (delamination) with visible fragments of flat coal grains, C – surface scratches with a small amount of coal grain, D – surface texturing typical of developing pits with a visible thin layer of coal, E – properly developed pitting phase with traces of coal particles, F – final pitting phase in the form of spalling (SEM).

Figure 12.

Sample surface defects following wear tests in the presence of a mixture of oil and coal with an ash content of λp = 9.24% (Variant 1): A, B – surface spalling (delamination) with visible fragments of flat coal grains, C – surface scratches with a small amount of coal grain, D – surface texturing typical of developing pits with a visible thin layer of coal, E – properly developed pitting phase with traces of coal particles, F – final pitting phase in the form of spalling (SEM).

Figure 13.

Results of profilometric tests of steel surface lubricated with oil contaminated with coal with an ash content of λp = 9.24% (Variant 1): A – 3D image of spalling, B – cross-section of the spalling area, C – longitudinal section of the spalling area.

Figure 13.

Results of profilometric tests of steel surface lubricated with oil contaminated with coal with an ash content of λp = 9.24% (Variant 1): A – 3D image of spalling, B – cross-section of the spalling area, C – longitudinal section of the spalling area.

Figure 14.

Sample surface defects following wear tests in the presence of a mixture of oil and coal with an ash content of λp = 29.15% (Variant 2): A, B – surface spalling (delamination) with visible fine coal grain fragments, C – surface scratches with numerous flat coal grains, D – fragments of superficial coal film, E, F – delamination edges with visible cracks and traces of coal particles (SEM).

Figure 14.

Sample surface defects following wear tests in the presence of a mixture of oil and coal with an ash content of λp = 29.15% (Variant 2): A, B – surface spalling (delamination) with visible fine coal grain fragments, C – surface scratches with numerous flat coal grains, D – fragments of superficial coal film, E, F – delamination edges with visible cracks and traces of coal particles (SEM).

Figure 15.

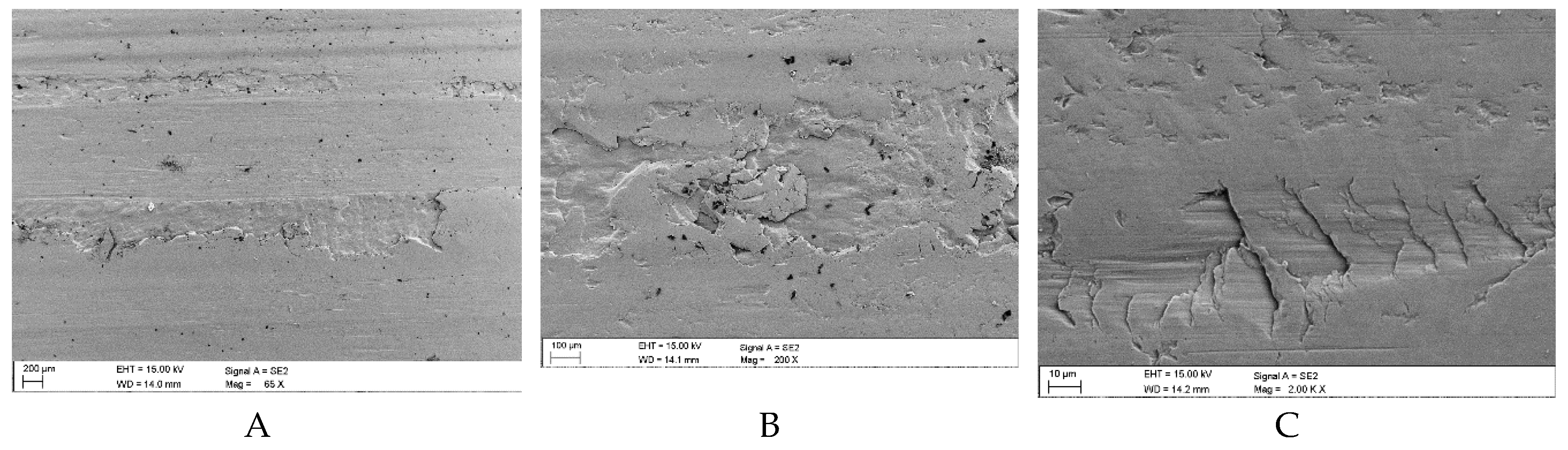

Sample surface defects following wear tests in the presence of a mixture of oil and coal with an ash content of λp = 55.28% (Variant 3): A, B – surface spalling (delamination) with visible small fragments of coal grains, C – initial and final phase of pitting with traces of surface scratches (SEM).

Figure 15.

Sample surface defects following wear tests in the presence of a mixture of oil and coal with an ash content of λp = 55.28% (Variant 3): A, B – surface spalling (delamination) with visible small fragments of coal grains, C – initial and final phase of pitting with traces of surface scratches (SEM).

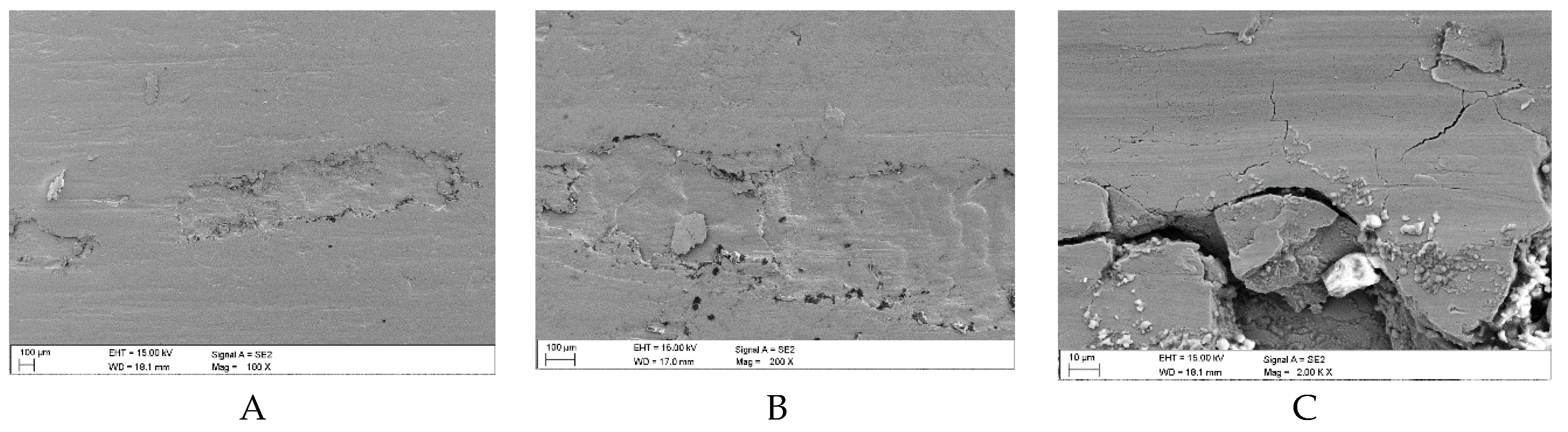

Figure 16.

Sample surface defects following wear tests in the presence of a mixture of oil and coal with an ash content of λp = 89.78% (Variant 5): A, B – surface spalling (delamination) with visible small fragments of claystone arranged the edge, C – surface crack against the background of shallow surface scratches (SEM).

Figure 16.

Sample surface defects following wear tests in the presence of a mixture of oil and coal with an ash content of λp = 89.78% (Variant 5): A, B – surface spalling (delamination) with visible small fragments of claystone arranged the edge, C – surface crack against the background of shallow surface scratches (SEM).

Figure 17.

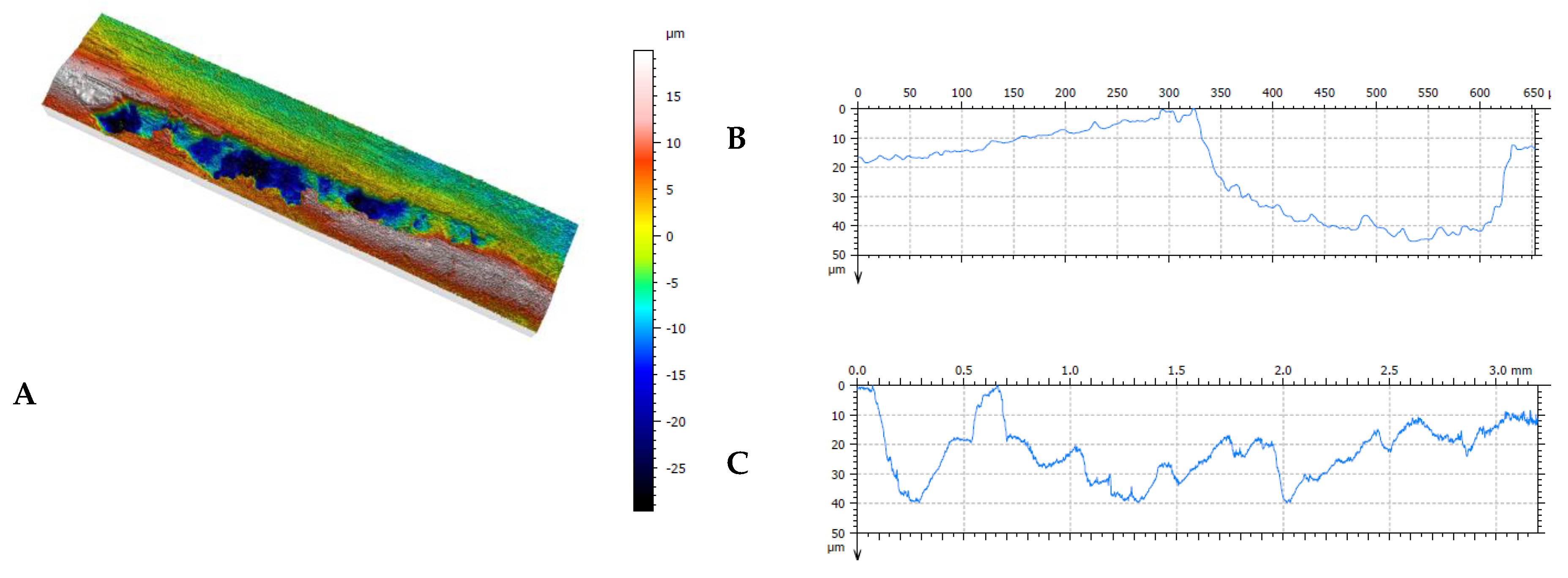

Results of profilometric tests of steel surface lubricated with oil contaminated with coal with an ash content of λp = 29.15% (Variant 2) in the spalling area: A – 3D image of spalling, B – cross-section of the spalling area, C – longitudinal section of the spalling area.

Figure 17.

Results of profilometric tests of steel surface lubricated with oil contaminated with coal with an ash content of λp = 29.15% (Variant 2) in the spalling area: A – 3D image of spalling, B – cross-section of the spalling area, C – longitudinal section of the spalling area.

Figure 18.

Results of profilometric tests of steel surface lubricated with oil contaminated with coal with an ash content of λp = 55.28% (Variant 3) in the spalling area: A – 3D image of spalling, B – cross-section of the spalling area, C – longitudinal section of the spalling area.

Figure 18.

Results of profilometric tests of steel surface lubricated with oil contaminated with coal with an ash content of λp = 55.28% (Variant 3) in the spalling area: A – 3D image of spalling, B – cross-section of the spalling area, C – longitudinal section of the spalling area.

Figure 19.

Results of profilometric tests of steel surface lubricated with oil contaminated with coal with an ash content of λp = 89.78% (Variant 5) in the spalling area: A – 3D image of spalling, B – cross-section of the spalling area, C – longitudinal section of the spalling area.

Figure 19.

Results of profilometric tests of steel surface lubricated with oil contaminated with coal with an ash content of λp = 89.78% (Variant 5) in the spalling area: A – 3D image of spalling, B – cross-section of the spalling area, C – longitudinal section of the spalling area.

Figure 20.

Schematic diagram of a friction node lubricated with oil with graphite additive.

Figure 20.

Schematic diagram of a friction node lubricated with oil with graphite additive.

Table 1.

Concentration, type, and size of particles in lubricating oil, retrieved from different operating environments; based on [

35].

Table 1.

Concentration, type, and size of particles in lubricating oil, retrieved from different operating environments; based on [

35].

| Oil Sampling Location |

Concentration, g/dm3

|

Grain Size

Range, 10-6 m |

Contamination Type |

Source |

| Paper mill |

0.4 |

0÷150 |

Cu, Si, Silicates |

[36] |

| Motor vehicle sump |

1÷2 |

0÷250 |

C, Fe |

[36] |

| Various bearing lubricants |

0.3÷1.5 |

0÷250 |

Fe, Al, Cu, Sn, SiC, sand |

[37] |

| Various |

|

0÷100 |

Al, Ag, Cr, Zn, Fe |

[38] |

| Motor vehicles |

0.3 |

0÷120 |

Al, Cu, Fe, Pb |

[38] |

| Aircraft gas turbines |

1÷2 |

0÷200 |

Fe, C, silicates |

[39] |

Table 2.

Theoretical maximum flash temperatures during ductile debris extrusion in a typical line, rolling-sliding, elastohydrodynamic contact. Counterface hardness is 800HV. (Adapted from the work of Nikas [

65,

66]).

Table 2.

Theoretical maximum flash temperatures during ductile debris extrusion in a typical line, rolling-sliding, elastohydrodynamic contact. Counterface hardness is 800HV. (Adapted from the work of Nikas [

65,

66]).

| Particle Diameter (µm) |

Particle Hardness (HV) |

Maximum Flash Temperature (°C) |

| Surface 1 |

Surface 2 |

| 5 |

100 |

93 |

17 |

| 5 |

200 |

185 |

34 |

| 5 |

400 |

350 |

68 |

| 10 |

100 |

211 |

103 |

| 10 |

200 |

415 |

182 |

| 10 |

400 |

760 |

318 |

| 20 |

100 |

1350 |

846 |

| 20 |

200 |

1560 |

962 |

| 20 |

400 |

1830 |

1120 |

Table 3.

Chemical composition of the 42CrMo-4 steel [mass%].

Table 3.

Chemical composition of the 42CrMo-4 steel [mass%].

| C |

Si |

Mn |

S |

P |

| 0.343 ± 0.012 |

0.54 ± 0.02 |

1.07 ± 0.03 |

0.014 ± 0.002 |

0.007± 0.001 |

| Cr |

Cu |

Ni |

Mo |

Al |

| 0.433 ± 0.01 |

0.0729 ± 0.004 |

0.418 ± 0.02 |

0.235 ± 0.01 |

0.0639 ± 0.004 |

Table 4.

List of lubricating oil mixtures as well as coal and coal-mineral contaminants examined.

Table 4.

List of lubricating oil mixtures as well as coal and coal-mineral contaminants examined.

| Variant no. |

Oil Tested |

Mass Fraction

of Abrasive, % |

Grain Diameter |

| 0 |

Class VG 220 mineral oil |

0 % |

|

| 1 |

1% |

0÷100 μm |

| 2 |

1% |

| 3 |

1% |

| 4 |

1% |

| 5 |

1% |

Table 5.

List of parameters characterising clean and contaminated lubricating oil.

Table 5.

List of parameters characterising clean and contaminated lubricating oil.

| Parameters |

Variant 0 |

Mean for Variant 1÷5 |

| Kinematic viscosity at 40°C |

189 mm2/s |

195.4 mm2/s |

| Kinematic viscosity at 100°C |

16.42 mm2/s |

16.6 mm2/s |

| Density at 15°C |

880 kg/m3

|

890 kg/m3

|

Table 6.

Results of calculations of minimum oil film thickness hmin and relative oil film thickness λ for the roller-roller combination.

Table 6.

Results of calculations of minimum oil film thickness hmin and relative oil film thickness λ for the roller-roller combination.

| Parameters |

Variant 0 |

Mean for Variant 1÷5 |

| Minimum oil film thickness hmin

|

0.212 μm |

0.218μm |

| Relative oil film thickness λ |

0.445 μm |

0.456 μm |

Table 7.

Results of calculations of Hertzian pressure and related parameters.

Table 7.

Results of calculations of Hertzian pressure and related parameters.

| Hertzian pressure |

-420.166 N/mm² |

| Half pressure width b |

0.074 mm |

| Maximum shear stress |

126.169 N/mm² |

| Distance at maximum shear stress |

0.058 mm |

Table 8.

Chemical analysis of test samples.

Table 8.

Chemical analysis of test samples.

| Component |

Variant no. |

| 1 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

|

| C, % |

71,8 ± 2,9 |

51,2 ± 2,1 |

30,2 ± 1,2 |

5,08 ± 0,51 |

1,75 ± 0,18 |

|

| S, % |

1,15 ± 0,17 |

1,02 ± 0,15 |

1,19 ± 0,18 |

0,14 ± 0,05 |

0,09 ± 0,04 |

|

| SiO2 , % |

3,72 ± 0,19 |

15,75 ± 0,79 |

31,16 ± 0,78 |

50,06 ± 1,25 |

57,42 ± 1,44 |

|

| Al2O3, % |

2,65 ± 0,13 |

6,50 ± 0,32 |

12,62 ± 0,63 |

20,13 ± 1,01 |

24,90 ± 1,24 |

|

| Fe2O3, % |

1,10 ± 0,11 |

1,90 ± 0,19 |

3,99 ± 0,20 |

8,87 ± 0,44 |

2,29 ± 0,11 |

|

| TiO2 , % |

0,10 ± 0,05 |

0,30 ± 0,15 |

0,55 ± 0,27 |

0,83 ± 0,42 |

0,58 ± 0,29 |

|

| MnO, % |

0,02 ± 0,01 |

0,03 ± 0,02 |

0,10 ± 0,05 |

0,22 ± 0,11 |

0,03 ± 0,01 |

|

| CaO, % |

0,57 ± 0,28 |

1,36 ± 0,14 |

1,69 ± 0,17 |

0,66 ± 0,33 |

0,13 ± 0,06 |

|

| MgO, % |

0,31 ± 0,15 |

0,94 ± 0,47 |

1,57 ± 0,16 |

1,94 ± 0,19 |

0,85 ± 0,42 |

|

| Na2O, % |

0,20 ± 0,10 |

0,08 ± 0,04 |

0,23 ± 0,11 |

0,26 ± 0,13 |

0,94 ± 0,47 |

|

| K2O, % |

0,14 ± 0,07 |

0,73 ± 0,36 |

1,71 ± 0,17 |

2,79 ± 0,14 |

2,78 ± 0,14 |

|

| P2O5, % |

0,10 ± 0,05 |

0,03 ± 0,02 |

0,13 ± 0,06 |

0,22 ± 0,11 |

0,07 ± 0,04 |

|

| Ash, % |

9,24%±0,51 |

29,15%±0,51 |

55,28%±0,51 |

85,93%±0,51 |

89,78%±0,51 |

|