1. Introduction

The special properties of grey cast iron with flake graphite (GJL) include exceptional resonance damping behavior and high thermal conductivity [

1]. These properties make GJL an excellent material for numerous automotive applications, such as gearboxes, crankcases, brake discs and valves. Brake discs produced from GJL offer an optimum combination of strength and thermal conductivity. This is essential in meeting the high demands for braking performance and durability in the automotive industry [

2]. However, cast iron's inherent brittleness poses a significant challenge, particularly in areas subject to thermal and mechanical stress. Additionally, the dust emissions generated by cast iron are a growing concern due to their potential health risks and negative impact on air quality. Combining the positive properties of GJL brake discs with a wear-resistant coating can significantly reduce dust emissions. One possible technology for applying these coatings is the Laser Metal Deposition (LMD) process [

3].

LMD is a coating manufacturing process where 3D parts are coated layer by layer by directly melting and depositing the material on the substrate [

4]. This technique can be further classified into Wire Laser Metal Deposition and Powder Laser Metal Deposition based on the type of material feedstock used [

5,

6]. LMD has gained significant attention in recent years in the field of metal processing due to its ability to customize material properties and its high geometric freedom which enables the fabrication of complex parts.

These properties make LMD an ideal process for increasing the performance and durability of GJL brake discs in high-stress applications. The coating process applies an extremely durable and wear resistant 316L stainless steel coating to the surface of the GJL brake disc. This improves both the mechanical and thermal behavior of the underlying GJL disc and significantly increases its corrosion resistance in corrosive environments [

7].

Previous studies have demonstrated the potential of LMD processes to produce high quality 316L stainless steel coatings with refined microstructures and improved mechanical properties. The microstructure of the coatings produced has been extensively characterized and the influence of the LMD process parameters on the results obtained has been studied in detail [

8]. In addition, dilatometric studies were carried out to better analyze the thermo-mechanical properties of the multilayer system under varying thermal loads.

The evaluation of grain size, texture appearance and crystal reorientation on exemplary brake discs was used to determine the material properties. These evaluations are used to make a reliable and safe statement about the performance of the brake disc in use.

It has been shown that the rapid cooling of the brake disc can influence the grain size of the layer produced with LMD. This is a critical parameter that significantly influences the mechanical properties of the material. Rapid cooling can lead to the formation of a finer microstructure, which significantly changes the strength and hardness of the material [

9].

A comprehensive analysis of the grain size both before and after the brake test can provide information on the effects of thermal and mechanical stresses on the microstructure. It has been shown that the influence of recrystallisation and grain growth processes, caused by the heat generated during the brake test, has a negative effect on the material properties of the brake discs [

10].

The effects of the LMD process parameters and the thermo-mechanical stress caused by the brake test can also influence the arrangement and structure of the material.

The preferential orientation of the grains in a polycrystalline material, also called texture, and the graphical representation of the crystallographic texture, also called pole Figure, can provide a clear explanation for the variation of the material properties. On the one hand, a strong texture can increase the anisotropic properties of the material, which means that the mechanical properties of the layered material become direction dependent [

11,

12].

Through a meticulous examination of the texture both before and after the brake test, it becomes possible to ascertain the extent to which the mechanical load and the resultant heat influence the grain orientation. Changes in texture could be indicative of plastic deformation or texture development due to thermal effects [

13,

14]. Changes in the pole Figures may indicate a reorientation of the grains or the formation of new texture components [

15].

Before the brake test, a comprehensive examination of the microstructure, texture, and pole Figures of the material is imperative to establish a baseline for the subsequent analysis and to validate the quality and homogeneity of the coating produced [

16]. After the brake test, it is essential to re-examine the properties to assess the effects of the mechanical load and heat generated on the material. These investigations can provide information on how the material character changes under real operating conditions. In particular, they can help to identify wear mechanisms, thermal effects and plastic deformation. This information is essential for optimizing LMD process parameters and improving the performance and life of the coatings produced. By combining the pre and post brake test results, valuable insights can be gained that will contribute to the development of more robust and efficient components [

17].

This study focuses on the microstructure and EBSD analysis of a two-layer 316L coating produced by LMD. EBSD is employed as the primary analytical method to obtain detailed information on grain orientation, grain boundary characteristics, and phase distribution [

18]. Previous research has shown that the microstructure and mechanical properties of 316L stainless steel can be significantly influenced by the LMD process parameters [

19]. Additionally, the presented study utilizes a brake shock corrosion test, which the durability and performance of brake components under conditions that simulate real-world exposure to corrosive environments and mechanical shock assesses. The aim of this work is to gain a deeper understanding of the microstructure-property relationships in 316L coatings and to evaluate the effects of LMD process parameters on the resulting microstructure before and after a brake shock corrosion test. By combining microstructural analysis and EBSD data should provide insights that can help optimize LMD processes and improve the material properties of 316L stainless steel [

20].

2. Materials and Methods

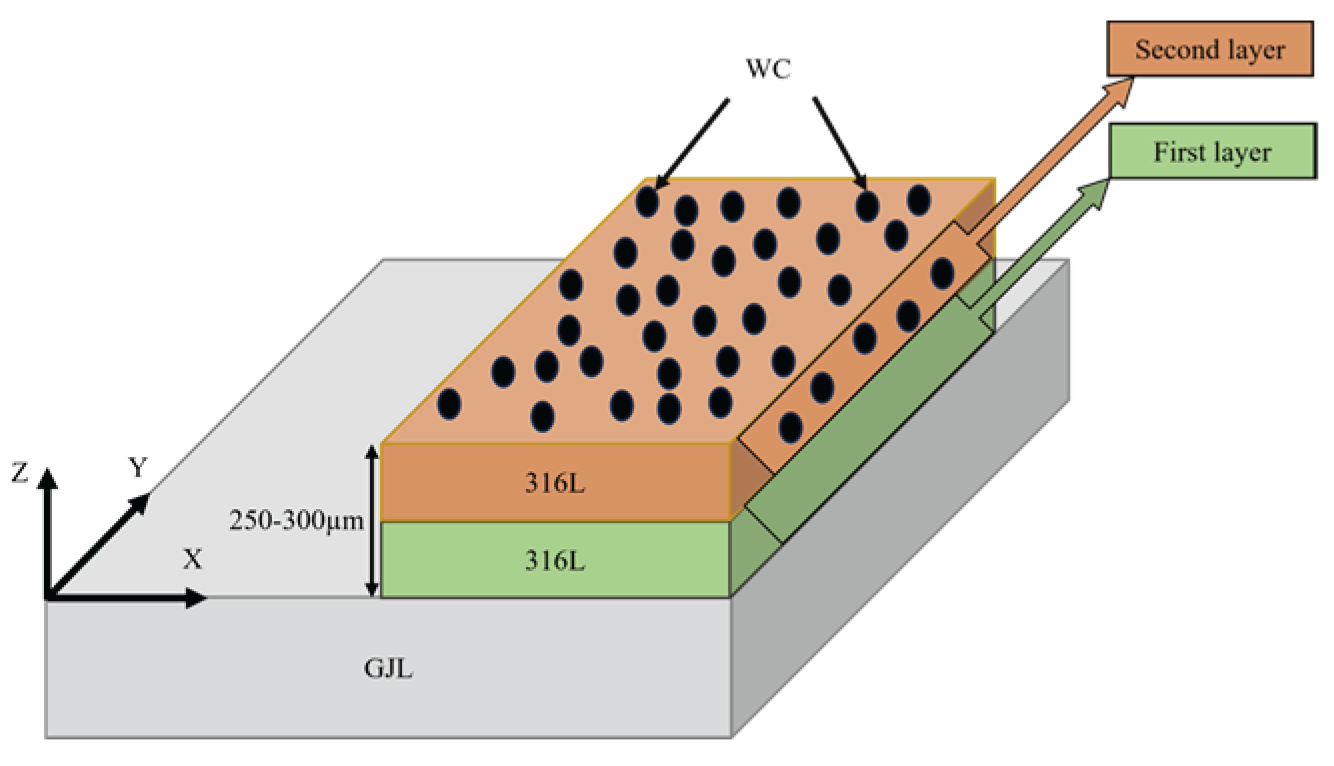

The objective of this study was to investigate the feasibility of laser cladding grey cast iron (GJL) 150 with distinct stainless steel alloy, namely 316L, in conjunction with WC particles. A multilayer cladding system was employed to produce the samples.

Figure 1 depicts a three-dimensional representation of the resulting coating system. The first layer was used to increase adhesion and to enhance the corrosion resistance of the surface. The second layer was specified to optimize the wear resistance. The 316L stainless steel powder, with a particle size distribution of 15-55 µm (max. 5 % oversize and undersize), was selected for its excellent corrosion resistance and mechanical properties. WC particles, with an average particle size of 5-30 µm, were incorporated to enhance the wear resistance of the coating.

In

Table 1 the chemical compositions of the used materials are shown. The chemical composition of the gas atomized powders used to coat the samples was provided by the supplier, Höganäs.

The LMD process was carried out using a high-power laser. The laser power was set to 20 kW. The samples were composed of 316L for the first layer and 316L with 25 to 30 wt. % WC hard particles in the second layer. The samples investigated are illustrated in

Table 2. One sample was subjected to a brake shock corrosion test in accordance with an automotive test specification. The test included 1200 brake cycles, a 20 h salt spray test to DIN EN ISO 9227 [

21], 16 h damp heat storage to DIN EN ISO 6270-2 [

22] and 20 h storage at room temperature (RT). The braking test was conducted to simulate the thermal and mechanical stresses experienced by the coatings in real-world applications. The test involved subjecting the coated samples to repeated braking cycles, with each cycle consisting of a rapid acceleration and deceleration phase. The temperature of the samples was monitored using thermocouples, and the maximum temperature reached during the test was 500 °C.

To evaluate the samples, they were separated, embedded, polished and etched to visualize the microstructure. The samples were prepared by mechanical polishing followed by vibratory polishing to achieve a high-quality surface finish. The samples were treated with a V2A etchant (50 % HCl, 10 % HNO3, and 40 % H2O) at 70 °C with an etching time of 30 s. Microstructural analysis was performed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM ZEISS EVO MA 15). The grain size and phase distribution were examined using Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD).

EBSD analysis was additionally used to obtain detailed information on grain orientation, grain boundary characteristics, and phase distribution. The EBSD data were collected using an SEM equipped with an EBSD detector Bruker and the samples tilted to 70° using 20 kV acceleration voltage. The resulting data were analyzed using “ESPRIT Analysis” software to generate orientation maps, grain boundary maps, and pole Figures. In order to test the phases identified in the coated GJL samples, the following phases were used as references: austenite, ferrite, sigma phase and tungsten carbide. The selection of these phases was made on the basis of their relevance to the microstructural and mechanical properties of the coated GJL samples. The careful examination of these phases is intended to investigate the behavior of the coating under real conditions and thus determine the effectiveness of the LMD process parameter.

Austenite was selected due to its face-centered cubic (FCC) phase, a structural form commonly observed in stainless steels, including the primary phase in 316L stainless steel. This phase is known for its ability to provide the requisite structural integrity and resistance to environmental factors. Ferrite was selected due to its possible phase transformation in the microstructure of the coating, as well as its influence on the mechanical properties and thermal behavior of the coating. The sigma phase is an intermetallic compound that can form in stainless steel, particularly under high-temperature conditions. The material is recognized for its brittleness and its detrimental effects on mechanical properties. The presence of sigma phase was investigated because it tends to form during the thermal cycling and mechanical stress encountered during brake tests, thereby impacting the coating's overall performance. The selection of CrFe was motivated by its propensity to form sigma phase during the laser metal deposition (LMD) process, a phenomenon that exerts a significant influence on the durability and performance of the coating. WC was selected due to its frequent application in conjunction with stainless steel coatings, with the objective of enhancing their performance under severe conditions, such as those encountered during brake tests.

3. Results and Discussions

To this end, investigations were carried out regarding the influence of the selected application parameters, including change in microstructure development and grain growth with the help of EBSD. Analyzing microstructural evolution and grain growth under service conditions including thermal and mechanical loads is crucial, as these changes directly impact the coating’s performance and longevity. EBSD observations on the cross-sectional surface indicate the presence of a microstructure gradient in the surface mechanical attrition treatment-affected region, consistent with the findings of a prior study [

23]. The results generated are shown and discussed in the following sections.

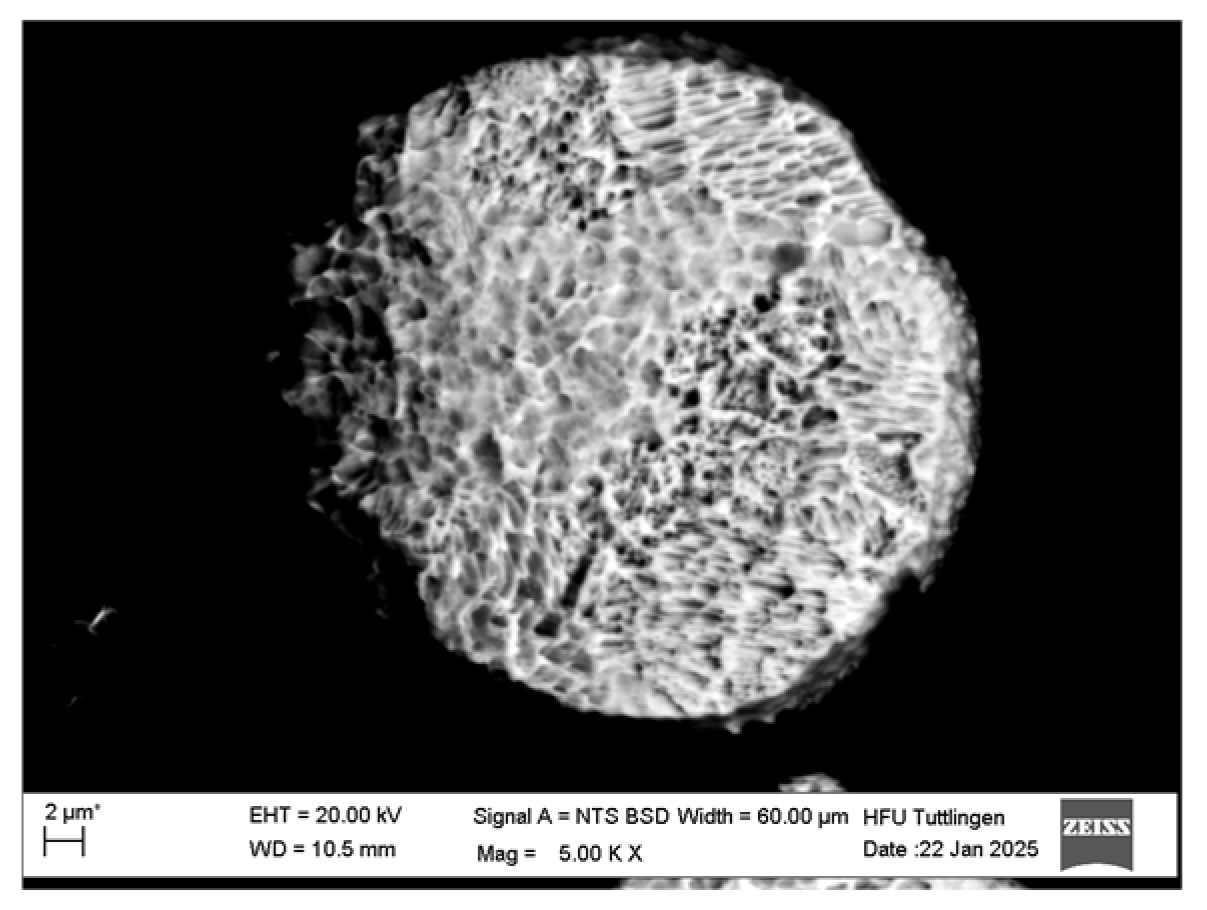

3.1. Microstructural Analysis of 316L Powder

The 316L powder was subjected to V2A etching in order to facilitate analysis of its microstructure using a scanning electron microscope (SEM).

Figure 2 shows a backscattered electron detector (BSD) image of an etched 316L powder particle. The increased visibility of the grain boundaries is indicative of well-defined grains that are distinctly separated from one another. The fine and uniform microstructure of 316L powder has the potential to enhance the strength and hardness of the coated material, which is advantageous for automotive applications.

The rapid heating and cooling cycles inherent to the LMD process engender residual stress within the material. These stresses are attributed to thermal gradients and the solidification process. These residual stresses have the potential to influence the mechanical properties of 316L stainless steel, potentially resulting in distortion, cracking, or a reduction in fatigue life [

24].

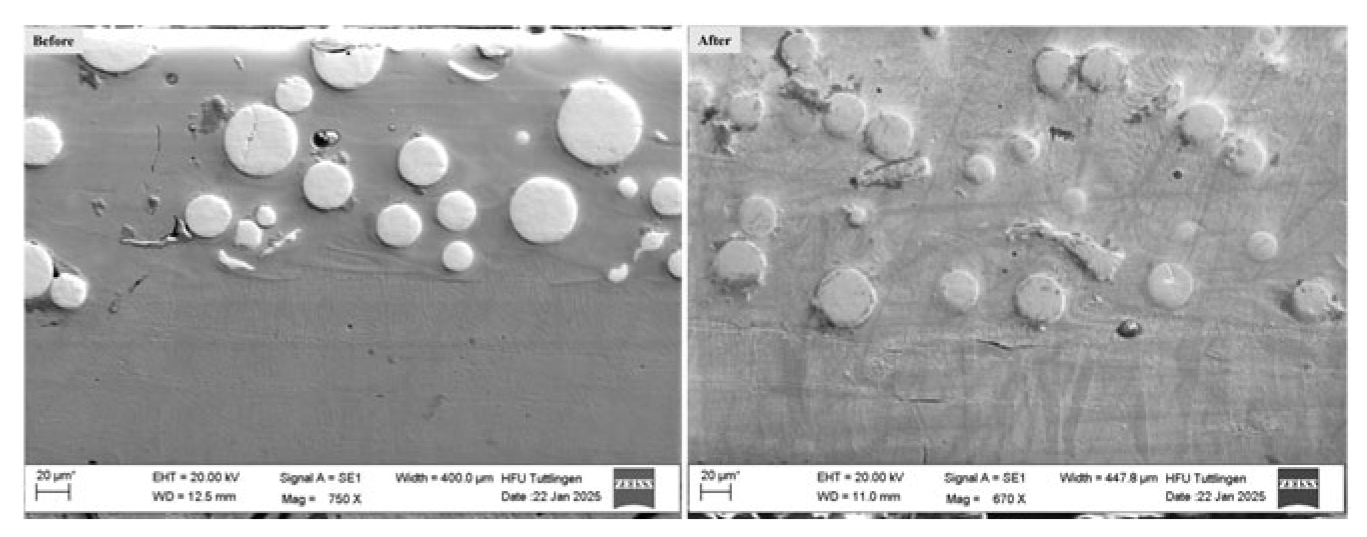

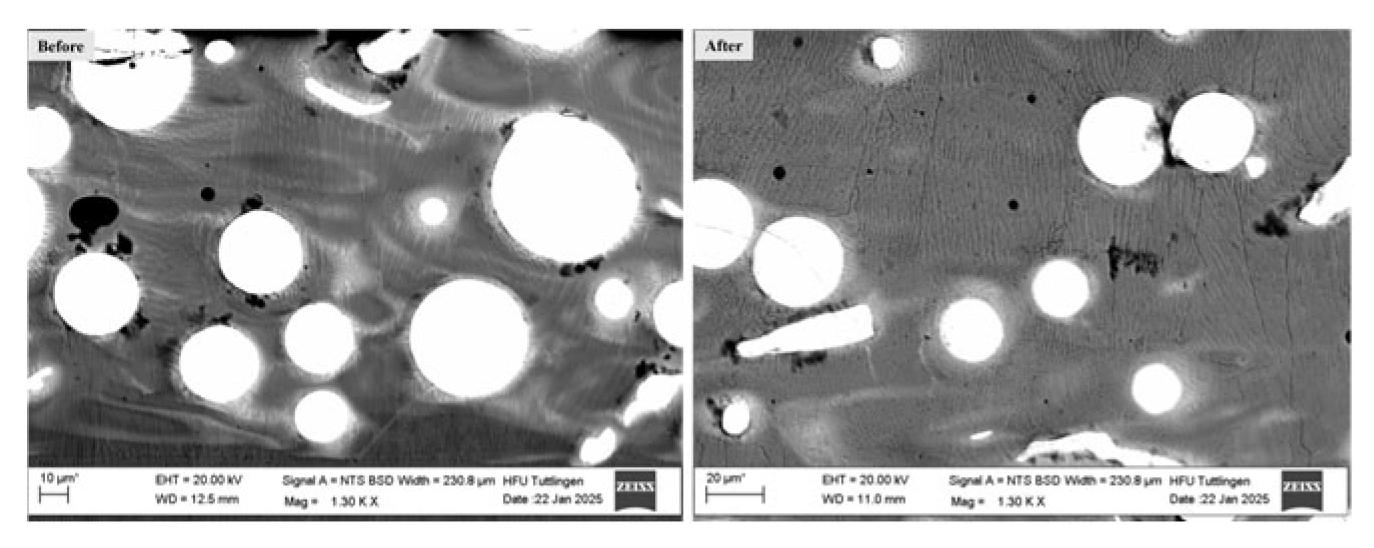

3.2. Microstructural Analysis of the First And second Layer Before and After the Brake Test

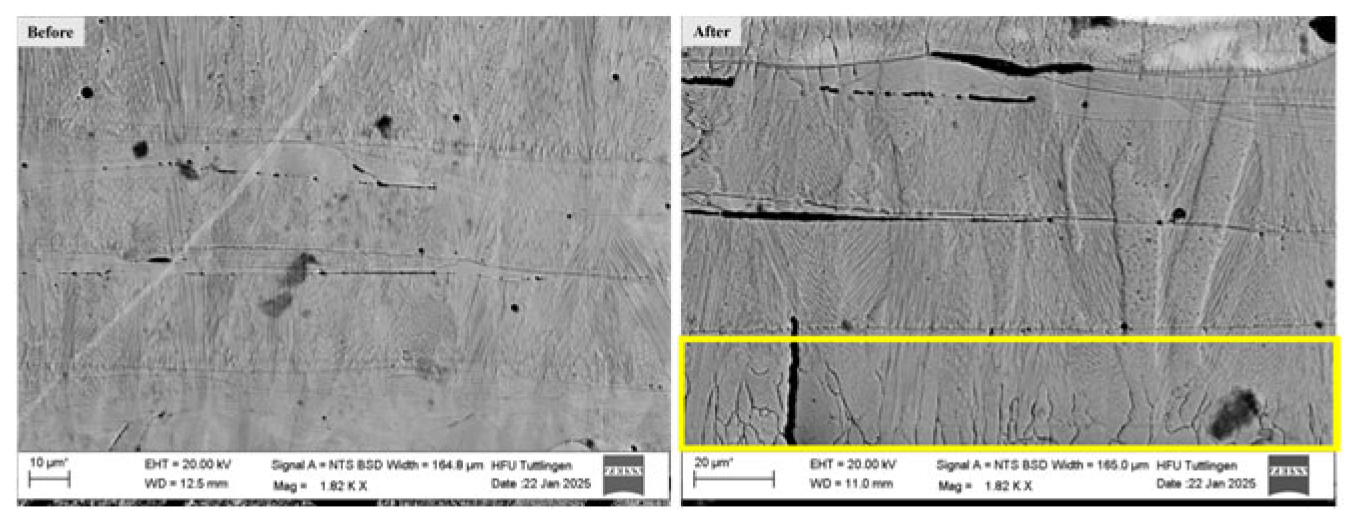

Firstly, the SEM images shown in

Figure 3 illustrate both coating layers before and after the brake test.

Figure 3 reveals a change in the microstructure of the coating matrix in both the first and second layer, indicating the effect of brake force and direction. To facilitate a more detailed analysis, each layer is shown and examined separately in the subsequent Figures before and after the brake test. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the evolution of grain misorientation in the initial layer during successive pulsed laser depositions is depicted. This evolution is followed by the outcome of the brake shock corrosion test, which is then analyzed.

The difference in the microstructure of the second layer after the brake test is shown in

Figure 4. The presence of WC hard particles within the coating's second layer, along with its matrix, is subject to the influence of the braking force. Thermo-mechanical stress is applied, and it is expected that this microstructure change can also be easily reconstructed on the grain size and orientation change of the grains. This stress is dependent on the braking force and the temperature generated during braking. In

Figure 4, the contrast is increased so that the matrix and its changes are more visible.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, the thermomechanical load resulting from braking has been transferred to the first coating layer. The alterations to the structural configuration can be observed in

Figure 5. As illustrated in the bottom right section of

Figure 5 in the yellow box, the phenomenon of split coating is evident, arising from the presence of mechanical stress and microcracks that emanate from the substrate.

In

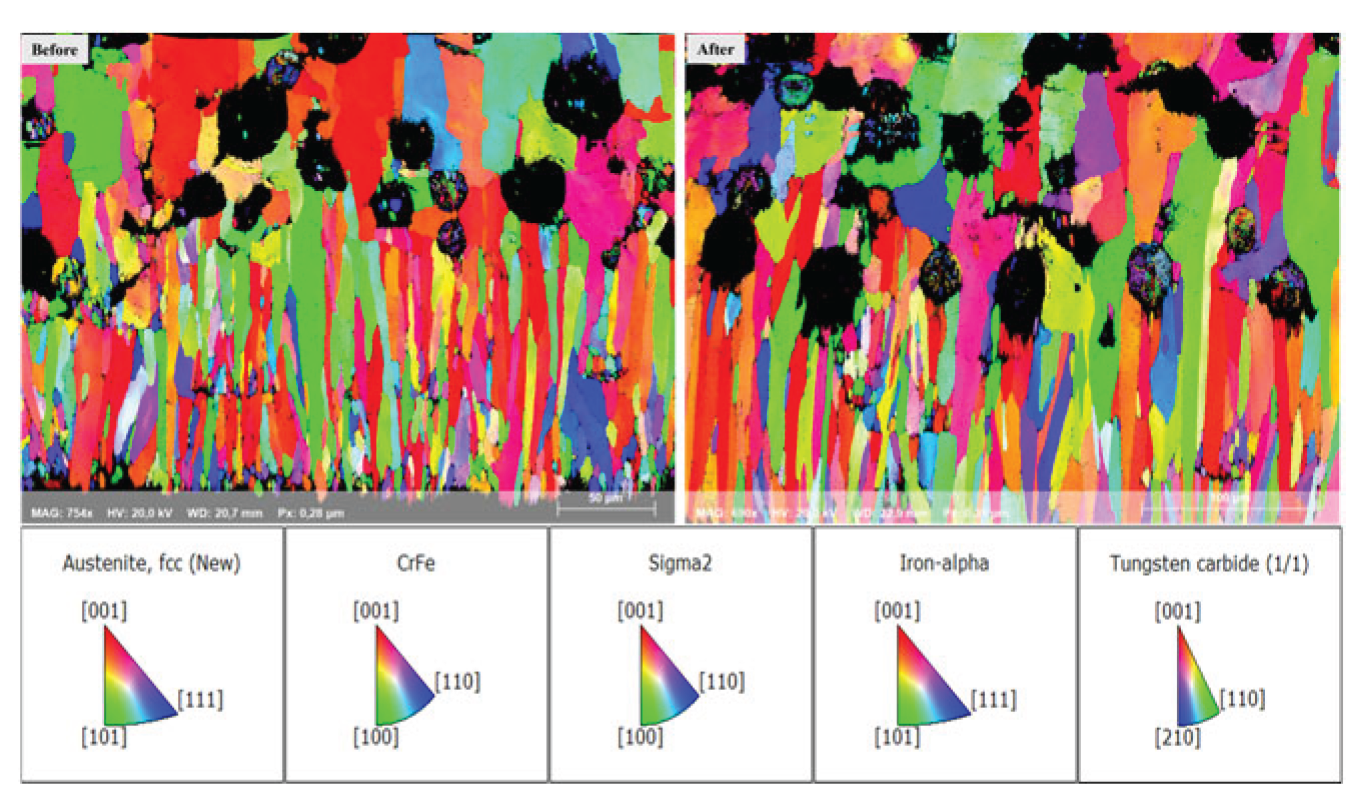

Figure 6, the results of the EBSD mappings of the two deposited coating layers are presented. A comparison of the two EBSD maps reveals an increase in the size of the grains. This observation is accompanied by a change in both layer grain size and texture. The increase in grain size and the evolution of textures suggests that the thermal and mechanical stresses during the brake test promote grain growth and reorientation. However, as illustrated in

Figure 6, the size of the 316L grain is increased after the LMD process compared to before the brake test. The microstructures exhibit significant variations in their appearance, contingent on the type of carbides that are incorporated. The enlargement of the microstructure of the second layer is most efficacious in the presence of added WC, exerting an influence on the grain size of the coating matrix [

23,

25].

The microstructure can also represent the as-treated state of the material, since at low temperature the microstructure is rather stable. Furthermore, the surface mechanical attrition treatment does not induce any austenitic phase transformation into martensite in this 316L alloy, as was previously observed in other studies [

23,

26]. In the study reported on by Zhang et al. [

27] the fabrication of a Ni-based superalloy coating was achieved through the process of pulsed laser deposition. The results of the study indicated that most of the grains exhibited an inclination in their growth orientation, with a predominant orientation of <001>. The arrangement of the grains within the coating gives rise to a distinct texture and generates anisotropy, exhibiting a modest angle misorientation of approximately 2°. This is attributable to the direction of the maximum temperature gradient experienced during the pulsed laser deposition process . The study by Wang et al. aims to ascertain the effect of processing parameters on the microstructure and mechanical properties of 304L stainless steel manufactured using the additive manufacturing process [

28]. A paucity of literature exists on the grain growth of coating material produced by LMD using different alloy powders in different application conditions.

Ensuring the uniform grain structure of the coating layer on brake discs is paramount to ensure optimal functionality during braking. This involves the formation of equiaxed grains, which is crucial for the even distribution of braking force within the coating. Consequently, it is imperative to maintain a pristine LMD process and to fabricate a brake disk with optimal properties and nearly zero defects in microstructure. Nevertheless, it is crucial to analyze in detail the effects of braking applications on the brake disc material during braking to enable the development of improved process optimization.

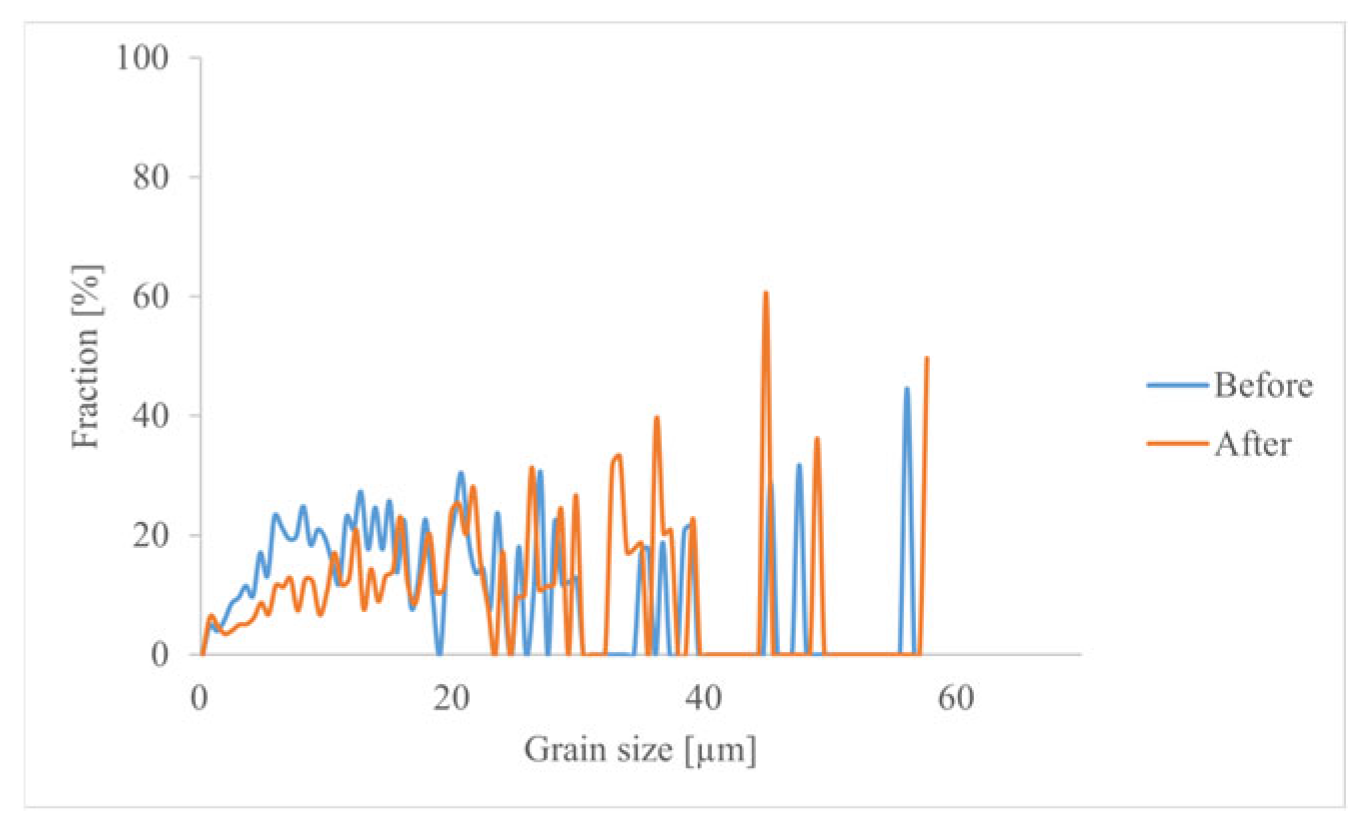

3.3. Evaluation of the Grain Size During the Brake Test

The present study was undertaken to evaluate the impact of braking on the microstructure of gray cast iron brake discs. For this purpose, the grain size of the discs was examined using EBSD before and after brake tests. The analysis of the grain size of the two coatings after the test demonstrated an increase during the braking test, as illustrated in the orange box in

Figure 7. The results of this study indicated like another study that the braking process influenced the grain size distribution [

29]. These alterations were then subjected to thorough analysis to ascertain the correlation between the brake conditions and the microstructural evolution of the gray cast iron [

8]. This analysis yielded valuable insights into the material's performance and durability under operational stresses.

After the braking test, an augmentation in grain size was observed, accompanied by the potential development of a new texture. This phenomenon can be attributed to the combined effects of thermal cycling and mechanical stress. This phenomenon could be indicative of recrystallization and grain growth, which, in turn, may result in alterations in strength and ductility. The literature confirms that thermal cycling and mechanical stress can significantly impact the microstructure of materials. For example, the study on wire-arc additive manufacturing shows that thermal cycling can lead to grain growth and changes in mechanical properties [

30]. Literature consistently indicates that recrystallization and grain growth can lead to alterations in mechanical properties. The study on AISI 316 stainless steel specifically notes that these processes can change the material's strength and ductility [

31].

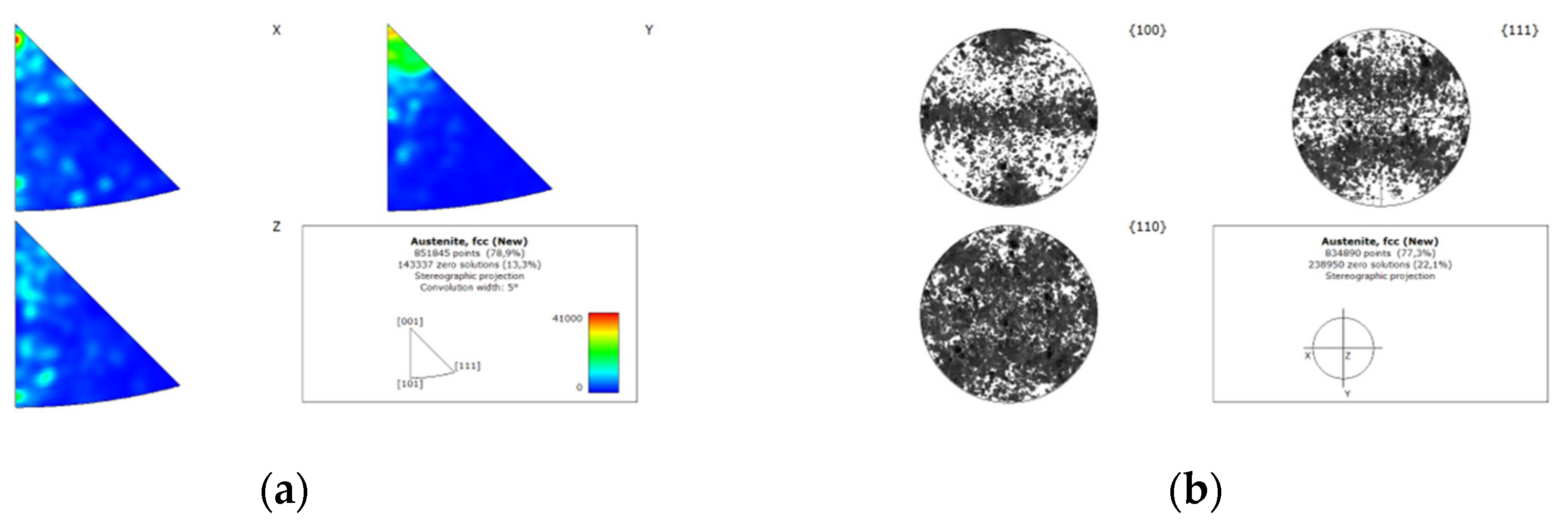

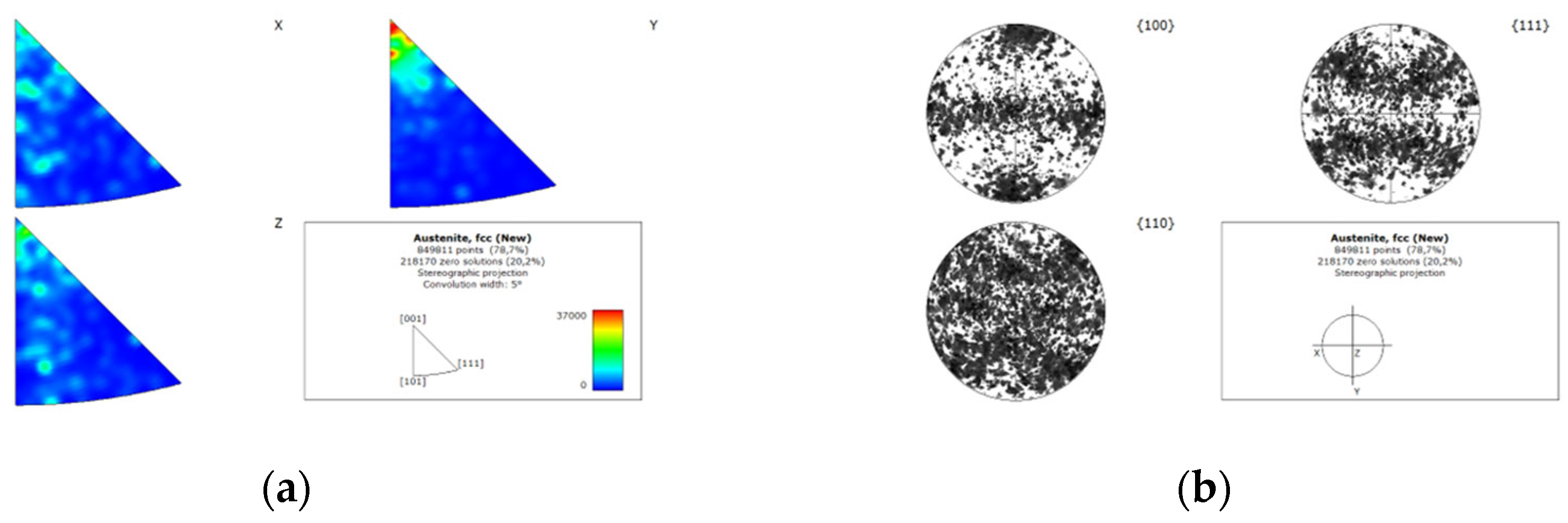

3.4. Pole Figures and Texture Analysis

For the rapid solidification process of pulsed laser deposition, the effects of concentration undercooling, curvature undercooling, thermal undercooling, and anisotropy of interfacial energy on the solidification can be ignored due to the high temperature gradient [

32]. Consequently, the dendritic growth orientation is determined by the direction of maximum temperature gradient, which is parallel to the laser deposition direction [

33]. The growth orientations of some grains deviate from {001}, indicating a relatively large angle between the direction of laser deposition and grain growth orientation of these grains [

29]. The austenite matrix of 316L stainless steel exhibits a face-centered cubic (fcc) crystal structure, with the primary slip system being {111} (<101>) and a preferential growth direction of {001} (<001>). This information is indispensable for understanding the grain growth and texture evolution in the samples under study [

34,

35].

It has been established that slip systems and growth direction exert an influence on the directional properties of material. This, in turn, affects the manner in which the material deforms and strengthens under stress. The {111} slip planes are the most densely packed planes in the fcc structure, allowing for easier dislocation movement, which contributes to the material's ductility and toughness [

36]. The preferential growth direction {001} (<001>) can lead to anisotropic properties, meaning the mechanical properties such as strength and ductility can vary depending on the direction of the applied force [

37].

This is a critical consideration for applications where directional properties are paramount. In the case of 316L alloy, the grain exhibits growth in the orientation of <001>, with the direction of maximum temperature gradient approximately perpendicular to the substrate surface. The growth orientations of certain dendrites in the bottom region of the coating are not perpendicular to the coating-substrate interface. The "bottom region of the coating" is defined as the part of the coating that is in closest proximity to the substrate, which is the underlying material or surface to which the coating is applied. This region is of particular significance because the interaction between the coating and the substrate can have a substantial impact on the overall properties and performance of the coating [

38]. Variations in grain orientation and dendrite growth in this area can affect the mechanical properties, such as strength and ductility, of the coating. This variation in orientation can be attributed to the non-perpendicular orientation of grains on the substrate surface [

39]. The orientation of grains can result in varying mechanical properties. For example, grains aligned with the {001} direction may exhibit higher strength and lower ductility compared to other orientations [

40]. It is imperative to comprehend anisotropic behavior for applications necessitating specific mechanical properties, such as in high-stress environments or components subjected to directional forces. This phenomenon can be elucidated by the effect of grain orientation on strength and ductility as well as corrosion resistance [

41]. The grain orientation can also affect the corrosion resistance of 316L stainless steel, with certain orientations providing better resistance in specific environments [

42]. The literature confirms that orientations such as {111} and {110} provide better corrosion resistance due to their atomic arrangement and surface energy characteristics [

43].

The transition from a texture resulting from the LMD process to a more pronounced texture after the brake test (in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) indicates that the grains have undergone a reorientation due to the applied stresses. This reorientation can influence the material's mechanical properties, potentially enhancing strength in specific directions while reducing it in others [

44]. The development of a preferred grain orientation (texture) can result in anisotropic properties, where the material's strength and ductility vary depending on the direction of the applied force [

45]. During the braking process, elevated temperatures and mechanical stresses can induce alterations in the microstructure of the coating, thereby affecting grain size and dendrite orientation. These alterations can influence the mechanical properties of the coating, potentially enhancing strength in specific directions while reducing it in others, leading to anisotropic properties where the material's strength and ductility vary depending on the direction of the applied force. This phenomenon is influenced by the thermal gradients during braking and solidification dynamics during the process [

27,

46].

By comparing the pole figures and IPFs before and after the brake test, it can be concluded that thermal and mechanical stress significantly influences the grain orientation and texture of the first layer. These observations are critical for comprehending the material's behavior under real-world conditions and enhancing the performance of the LMD process. By understanding and optimizing the factors that affect grain orientation and texture, the performance of the LMD process can be significantly improved, leading to higher quality and more reliable components [

34,

35].

As previously outlined in the publications [

3,

8], the interface relationship between the substrate and the first layer after the brake test poses a considerable challenge.

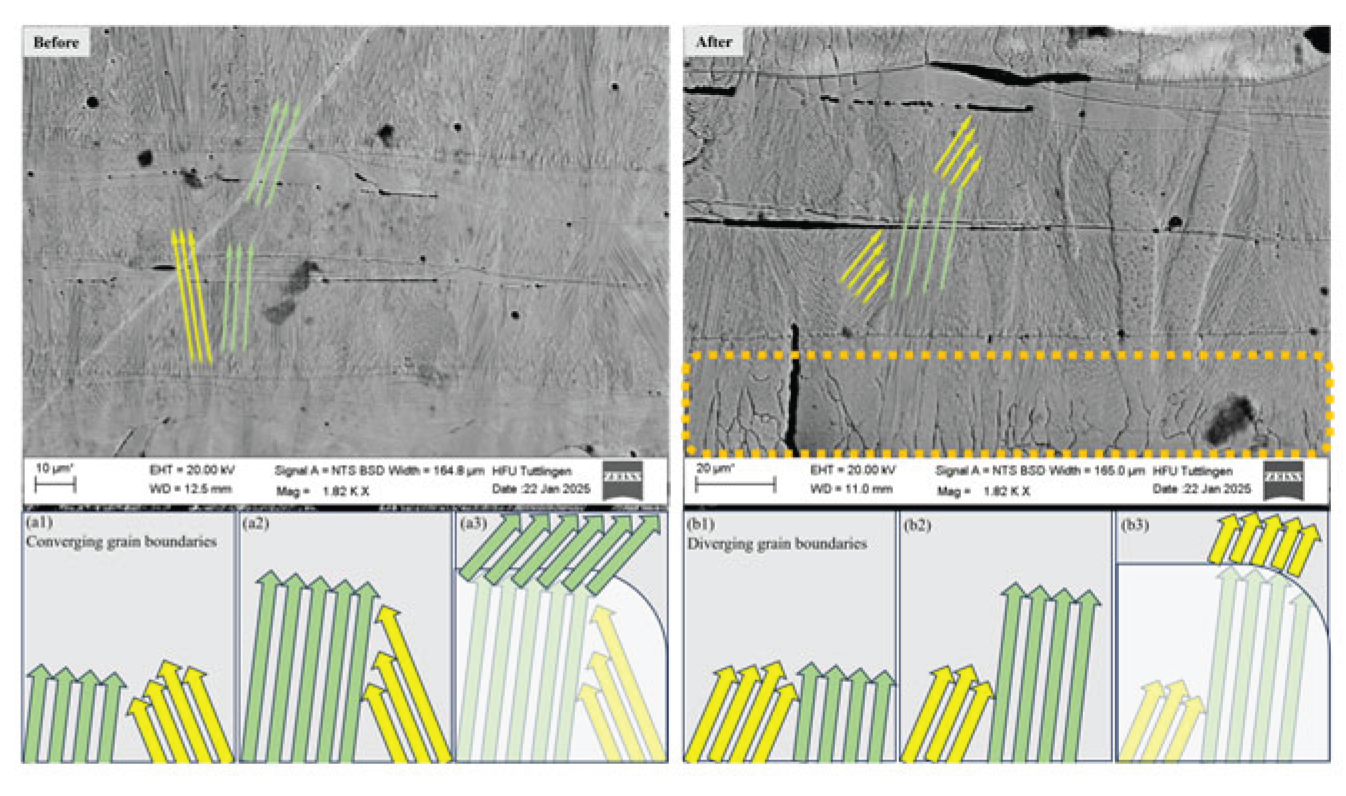

As demonstrated in

Figure 10 after the brake test in the yellow box, numerous microcracks emerge from the substrate direction, signifying a critical aspect that warrants investigation. This phenomenon suggests a potential modification of the grain boundary. A grain boundary where the growing dendrites of neighboring grains are inclined towards each other in the direction of growth (so-called converging GRAIN BOUNDARY) promotes the unfavorably oriented grain, while a grain boundary where the dendrites grow away from each other (so-called diverging GRAIN BOUNDARY) tends to cause unfavorably oriented grains to become overgrown [

47].

A comparable mechanism has been delineated in the publication Sun. It is imperative to undertake a comprehensive analysis of this mechanism both prior to and following the braking test [

48]. As illustrated in a modified form in

Figure 10, the arrangement of the converging and diverging GBs under the influence of mechanical and thermal stress during braking is shown in panels a1 to a3 (

Figure 10 left) before the braking test and panels b1 to b3 (

Figure 10 right) after the braking test.

The textured grain with the <001> orientation is observed to be predominant in the converging grain boundary under the influence of mechanical and thermal stress during the braking process (see

Figure 10a).Guo et al. have demonstrated through phase field simulations that this phenomenon occurs under specific conditions, namely when the misorientation angle (α), defined as the smallest angle between the fast-growing <001> directions of the two competing crystals, is sufficiently small [

49].

It is reasonable to hypothesize that the <101> textured grain will begin to overgrow its <001> counterpart. Overgrowth can develop obliquely and maintain orientation, presumably because there are more choices for the preferred crystallographic growth directions (see

Figure 8a and 9a). If the grains continue to grow adjacent to a converging grain boundary and toward a curved melt pool (

Figure 10 a3), they will have a greater number of growth directions to grow under similar orientations. However, the other grains will also have different orientations or will continue to grow due to the thermal stress. This illustration can also be seen in

Figure 10 b3.

4. Conclusions

This study highlights the novelty and significance of using a two-layer 316L stainless steel coating on gray cast iron (GJL) produced by LMD to understand the effect of the brake test on microstructure. The results demonstrate that thermal cycling and mechanical stress during braking tests significantly influence the microstructure, promoting grain growth and reorientation. These findings provide a deeper understanding of the material's behavior under real-world conditions, contributing to the development of more durable and reliable coatings for automotive and other industrial applications. Compared to previous studies, this work offers a comprehensive analysis of the microstructural changes induced by braking force and corrosive atmosphere, using advanced techniques such as SEM and EBSD. The study emphasizes the importance of understanding thermal effects and microstructural changes to optimize brake performance and ensure safety. These insights can contribute to the optimization of LMD processes and the enhancement of material properties of 316L stainless steel coatings, paving the way for future research and development in this field.

The initial microstructure of 316L powder, as observed through SEM, undergoes significant changes when etched with V2A pickling. The presence of fine grains contributes to the favorable mechanical properties of 316L powder. The uniform distribution of grains and clear visibility of grain boundaries indicate a homogeneous microstructure.

Before the brake test, the first layer exhibits a uniform grain structure with fine, equiaxed grains and well-defined grain boundaries. After the brake test, significant changes in the microstructure and grain orientation are observed. Thermal cycling and mechanical stress during the brake test promote grain growth and reorientation, resulting in an increase in grain size and the development of a new texture. Overall, the microstructural analysis reveals that the fine and uniform grains of 316L powder contribute to its favorable mechanical properties, which are further enhanced by the laser deposition process. However, the brake test induces significant microstructural changes, which can affect the material's strength and ductility [

50,

51]. This suggests that the microstructure of 316L stainless steel is sensitive to such conditions, impacting on its long-term stability and performance [

52].

The transition from a texture resulting from the LMD process to a more pronounced texture after the brake test indicates that the grains have undergone reorientation due to the applied stresses. This reorientation can influence the material's mechanical properties, potentially enhancing strength in specific directions while reducing it in others [

53,

54].

In the case of 316L alloy, grains exhibit growth in the orientation of <001>, with the direction of maximum temperature gradient approximately perpendicular to the substrate surface. Certain dendrites' growth orientations are not perpendicular to the coating-substrate interface in the bottom region, attributed to the non-perpendicular orientation of grains on the substrate surface [

53,

55,

56].

Stainless steel 316L is characterized by austenite phase with face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal lattice structure. No phase transformations of any kind occurred on this scale before or after the brake test [

57]. The austenite matrix of 316L stainless steel exhibits a face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal structure, with the primary slip system being {111} (<101>) and a preferential growth direction of {001} (<001>). This information is indispensable for understanding grain growth and texture evolution in the samples under study [

41].

The development of a preferred grain orientation (texture) after the brake test can result in anisotropic properties, where the material's strength and ductility vary depending on the direction of the applied force. This is critical for applications where directional properties are important, and it underscores the need for careful consideration of grain orientation in the design of coatings [

58].

The study highlights the importance of understanding how thermal cycling and mechanical stress influence the microstructure and properties of coatings. This knowledge is crucial for designing coatings that can withstand the harsh conditions encountered in real-world applications, such as automotive braking systems [

59,

60].

Author Contributions

This research article is written by several authors with the following contributions: Conceptualization, M.M.; Methodology, M.M.; Validation, M.M., A.C., H.P., and H.M.-J.; Formal analysis, M.M. and A.C.; Investigation, M.M. and A.C.; Resources, M.M., A.C., H.P., and H.M.-J.; Data curation, M.M. and A.C.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; Writing—review and editing, M.M., C.A., H.P., and H.M.-J.; Visualization, M.M., C.A.; Supervision, H.P. and H.M.-J.; Project administration, M.M., H.P., and H.M.-J.; Funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Future Perspectives

The study of the microstructure and mechanical properties of 316L stainless steel before and after the brake test provides valuable insights into the effects of thermal and mechanical stresses. Future research could focus on understanding the mechanisms of grain growth and reorientation to improve material properties. Advanced characterization techniques, such as in-situ SEM and synchrotron X‐ray diffraction, could be used to observe microstructural changes in real-time. Additionally, exploring the anisotropy of mechanical properties and controlling texture could lead to tailored materials for specific applications.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All required data in this article have only been published here and should be considered with respect to copyright.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Franke, S. Gießerei Lexikon; 13th ed.; Schiele & Schön, 2019.

- Weißbach, W.; Dahms, M.; Jaroschek, C. Werkstoffe Und Ihre Anwendungen; 2005. ISBN 978-3-658-19892-3.

- Masafi, M.; Palkowski, H.; Mozaffari-Jovein, H. Micro-Friction Mechanism Characterization of Particle-Reinforced Multilayer Systems of 316L and 430L Alloys on Grey Cast Iron. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 33, 6090–6101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Guo, X.; Kane, S.; Deng, Y.; Jung, Y.-G.; Lee, J.-H.; Zhang, J. Additive Manufacturing of Metallic Materials: A Review. J Mater Eng Perform 2018, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascari, A.; Lutey, A.H.A.; Liverani, E.; Fortunato, A. Laser Directed Energy Deposition of Bulk 316L Stainless Steel. Lasers in Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2020, 7, 426–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, J.; Ji, I.; Lee, S.H. Numerical and Experimental Investigations of Laser Metal Deposition (LMD) Using STS 316L. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badoniya, P.; Srivastava, M.; Jain, P.K.; Rathee, S. A State-of-the-Art Review on Metal Additive Manufacturing: Milestones, Trends, Challenges and Perspectives. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering 2024, 46, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masafi, M.; Palkowski, H.; Mozaffari-Jovein, H. Microstructural Properties of Particle-Reinforced Multilayer Systems of 316L and 430L Alloys on Gray Cast Iron. Coatings 2023, 13, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahani Khabushan, J.; Bazzaz Bonabi, S. Investigating of the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al-Based Composite Reinforced with Nano-Trioxide Tungsten via Accumulative Roll Bonding Process. Open J Met 2017, 07, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KCHAOU, M.; KUS, R.; SINGARAVELU, D.L.; HARAN, S.M. Design, Characterization, and Performance Analysis of Miscanthus Fiber Reinforced Composite for Brake Application. Journal of Engineering Research 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feo, M.L.; Torre, M.; Tratzi, P.; Battistelli, F.; Tomassetti, L.; Petracchini, F.; Guerriero, E.; Paolini, V. Laboratory and On-Road Testing for Brake Wear Particle Emissions: A Review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 100282–100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathissen, M.; Grochowicz, J.; Schmidt, C.; Vogt, R.; Farwick zum Hagen, F.H.; Grabiec, T.; Steven, H.; Grigoratos, T. A Novel Real-World Braking Cycle for Studying Brake Wear Particle Emissions. Wear 2018, 414–415, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNonno, O.; Saville, A.; Benzing, J.; Klemm-Toole, J.; Yu, Z. Solidification Behavior and Texture of 316L Austenitic Stainless Steel by Laser Wire Directed Energy Deposition. Mater Charact 2024, 211, 113916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzminova, Y.O.; Evlashin, S.A.; Belyakov, A.N. On the Texture and Strength of a 316L Steel Processed by Powder Bed Fusion. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2024, 913, 147026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R. Effects of Grain Size, Texture and Grain Growth Capacity Gradients on the Deformation Mechanisms and Mechanical Properties of Gradient Nanostructured Nickel. Acta Mech 2023, 234, 4147–4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lita, A.E.; Sanchez, J.E. Effects of Grain Growth on Dynamic Surface Scaling during the Deposition of Al Polycrystalline Thin Films. Phys Rev B 2000, 61, 7692–7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemani, M.; Nosko, O.; Metinoz, I.; Olofsson, U. A Study on Emission of Airborne Wear Particles from Car Brake Friction Pairs. SAE International Journal of Materials and Manufacturing 2015, 9, 015-01–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Ma, J.; Ji, H. EBSD Analysis of 316L Stainless Steel Weldment on Fusion Reactor Vacuum Vessel. Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals 2023, 76, 3379–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsujjoha, Md.; Agnew, S.R.; Fitz-Gerald, J.M.; Moore, W.R.; Newman, T.A. High Strength and Ductility of Additively Manufactured 316L Stainless Steel Explained. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 2018, 49, 3011–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, S.-Iong.; Gelman, Len.; Hukins, D.W.L.. World Congress on Engineering : WCE 2016 : 29 June - 1 July, 2016, Imperial College London, London, U.K.; Newswood Limited, 2016. ISBN 9789881404800.

- DIN EN ISO 9227:2017-07, Korrosionsprüfungen in Künstlichen Atmosphären_- Salzsprühnebelprüfungen (ISO_9227:2017); Deutsche Fassung EN_ISO_9227:2017 2017.

- DIN EN ISO 6270-2:2018-04, Beschichtungsstoffe_- Bestimmung Der Beständigkeit Gegen Feuchtigkeit_- Teil_2: Kondensation (Beanspruchung in Einer Klimakammer Mit Geheiztem Wasserbehälter) (ISO_6270-2:2017); Deutsche Fassung EN_ISO_6270-2:2018 2018.

- Sun, Z.; Retraint, D.; Baudin, T.; Helbert, A.L.; Brisset, F.; Chemkhi, M.; Zhou, J.; Kanouté, P. Experimental Study of Microstructure Changes Due to Low Cycle Fatigue of a Steel Nanocrystallised by Surface Mechanical Attrition Treatment (SMAT). Mater Charact 2017, 124, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.-J.; Wang, Z.-G.; Su, H.-H. Thermomechanical Fatigue of a 316L Austenittc Steel at Two Different Temperature Intervals. Scr Mater 1996, 35, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proust, G.; Retraint, D.; Chemkhi, M.; Roos, A.; Demangel, C. Electron Backscatter Diffraction and Transmission Kikuchi Diffraction Analysis of an Austenitic Stainless Steel Subjected to Surface Mechanical Attrition Treatment and Plasma Nitriding. Microscopy and Microanalysis 2015, 21, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proust, G.; Trimby, P.; Piazolo, S.; Retraint, D. Characterization of Ultra-Fine Grained and Nanocrystalline Materials Using Transmission Kikuchi Diffraction. Journal of Visualized Experiments 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Dai, J.; Huang, Z.; Meng, T. Grain Growth of Ni-Based Superalloy IN718 Coating Fabricated by Pulsed Laser Deposition. Opt Laser Technol 2016, 80, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Palmer, T.A.; Beese, A.M. Effect of Processing Parameters on Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Austenitic Stainless Steel 304L Made by Directed Energy Deposition Additive Manufacturing. Acta Mater 2016, 110, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.H.; Wu, C.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Sun, Z. Microstructure Evolution and EBSD Analysis of a Graded Steel Fabricated by Laser Additive Manufacturing. Vacuum 2017, 141, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasov, I.; Gordienko, A.; Kuznetsova, A.; Semenchuk, V. Effects of Heat Input and Thermal Cycling on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Steel Walls Built By Wire-Arc Additive Manufacturing. Metallography, Microstructure, and Analysis 2025, 14, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Schino, A.; Kenny, J.M.; Abbruzzese, G. Analysis of the Recrystallization and Grain Growth Processes in AISI 316 Stainless Steel. J Mater Sci 2002, 37, 5291–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, W.H.; Zhigilei, L. V Computational Study of Cooling Rates and Recrystallization Kinetics in Short Pulse Laser Quenching of Metal Targets. J Phys Conf Ser 2007, 59, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Yao, J.; Kovalenko, V. Dendritic Growth Transition During Laser Rapid Solidification of Nickel-Based Superalloy. JOM 2021, 73, 1538–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhang, K.; Wen, J. Influence of Temperature on Creep Behavior of Ag Particle Enhancement SnCu Based Composite Solder. Tsinghua Sci Technol 2007, 12, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokadem, S.; Bezençon, C.; Hauert, A.; Jacot, A.; Kurz, W. Laser Repair of Superalloy Single Crystals with Varying Substrate Orientations. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 2007, 38, 1500–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas Dorantes, C.A.; Czekanski, A. Compaction Effects on the Thermal Properties of Stainless Steel 316L Powders in 3D Printing Processes. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Bai, Y.; Tao, H.; Fu, Q.; Xiong, L.; Weng, J.; Wang, S.; Zhao, H.; Han, Y.; Ding, J. Anisotropic Optoelectronic Properties of MAPbI3 on (100), (112) and (001) Facets. J Electron Mater 2021, 50, 6881–6887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drory, M.D.; Hutchinson, J.W. Measurement of the Adhesion of a Brittle Film on a Ductile Substrate by Indentation; 1996.

- Mohanty, R.; Khan, A.R. CHALLENGES DURING SCALE-UP IN WURSTER COATING; 2020; Vol. 8.

- Thak Sang Byun Timothy G. Lach Mechanical Properties of 304L and 316L Austenitic Stainless Steels after Thermal Aging for 1500 Hours Cast Stainless Steel Aging (LW-16OR040215); 2016.

- Zhi, H.R.; Zhao, H.T.; Zhang, Y.F.; Dampilon, B. Microstructure and Crystallographic Texture of Direct Energy Deposition Printed 316L Stainless Steel. Dig J Nanomater Biostruct 2023, 18, 1293–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luecke, W.E.; Slotwinski, J.A. Mechanical Properties of Austenitic Stainless Steel Made by Additive Manufacturing. J Res Natl Inst Stand Technol 2014, 119, 398–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanbury, R.D.; Was, G.S. Effect of Grain Orientation on Irradiation Assisted Corrosion of 316L Stainless Steel in Simulated PWR Primary Water. In; 2019; pp. 2303–2312.

- Li, Q. Anisotropic Mechanical Properties of 2-D Materials. In Plastic Deformation in Materials [Working Title]; IntechOpen, 2021.

- Jacek J. Skrzypek, A.W.G. Mechanics of Anisotropic Materials; Skrzypek, J.J., Ganczarski, A.W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015. ISBN 978-3-319-17159-3.

- Jang, W.-L.; Wang, T.-S.; Lai, Y.-F.; Lin, K.-L.; Lai, Y.-S. The Performance and Fracture Mechanism of Solder Joints under Mechanical Reliability Test. Microelectronics Reliability 2012, 52, 1428–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Z.; Volek, A.; Green, N.R. Mechanism of Competitive Grain Growth in Directional Solidification of a Nickel-Base Superalloy. Acta Mater 2008, 56, 2631–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Tsai, S.-P.; Konijnenberg, P.; Wang, J.-Y.; Zaefferer, S. A Large-Volume 3D EBSD Study on Additively Manufactured 316L Stainless Steel. Scr Mater 2024, 238, 115723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Takaki, T.; Sakane, S.; Ohno, M.; Shibuta, Y.; Mohri, T. Overgrowth Behavior at Converging Grain Boundaries during Competitive Grain Growth: A Two-Dimensional Phase-Field Study. Int J Heat Mass Transf 2020, 160, 120196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastac, M.; Lucas, R.; Klein, A. MICROSTRUCTURE AND MECHANICAL PROPERTIES COMPARISON OF 316L PARTS PRODUCED BY DIFFERENT ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING PROCESSES.

- Radhamani, A. V.; Lau, H.C.; Ramakrishna, S. 316L Stainless Steel Microstructural, Mechanical, and Corrosion Behavior: A Comparison Between Spark Plasma Sintering, Laser Metal Deposition, and Cold Spray. J Mater Eng Perform 2021, 30, 3492–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonda, R.W.; Rowenhorst, D.J.; Feng, C.R.; Levinson, A.J.; Knipling, K.E.; Olig, S.; Ntiros, A.; Stiles, B.; Rayne, R. The Effects of Post-Processing in Additively Manufactured 316L Stainless Steels. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 2020, 51, 6560–6573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolzhenko, P.; Tikhonova, M.; Odnobokova, M.; Kaibyshev, R.; Belyakov, A. On Grain Boundary Engineering for a 316L Austenitic Stainless Steel. Metals (Basel) 2022, 12, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Jin, K.; Liu, X.; Qiao, X.; Yang, W. Tribological Performance of Textured 316L Stainless Steel Prepared by Selective Laser Melting. J Mater Eng Perform 2025, 34, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassine, N.; Chatti, S.; Kolsi, L. Tailoring Grain Structure Including Grain Size Distribution, Morphology, and Orientation via Building Parameters on 316L Parts Produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2024, 131, 4483–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Xia, S.; Bai, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L. The Recrystallization Nucleation Mechanism for a Low-Level Strained 316L Stainless Steel and Its Implication to Twin-Induced Grain Boundary Engineering. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 2024, 55, 4525–4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalepka, K.; Skoczeń, B.; Ciepielowska, M.; Schmidt, R.; Tabin, J.; Schmidt, E.; Zwolińska-Faryj, W.; Chulist, R. Phase Transformation in 316L Austenitic Steel Induced by Fracture at Cryogenic Temperatures: Experiment and Modelling. Materials 2020, 14, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.-P.; Tan, Z.-H.; Lv, J.-L.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Liu, D. Effect of Annealing and Strain Rate on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Austenitic Stainless Steel 316L Manufactured by Selective Laser Melting. Adv Manuf 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Jiang, F.; Deng, D.; Xin, T.; Sun, X.; Mousavian, R.T.; Peng, R.L.; Yang, Z.; Moverare, J. Cyclic Response of Additive Manufactured 316L Stainless Steel: The Role of Cell Structures. Scr Mater 2021, 205, 114190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkoohi, E.; Sievers, D.E.; Garmestani, H.; Liang, S.Y. Thermo-Mechanical Modeling of Thermal Stress in Metal Additive Manufacturing Considering Elastoplastic Hardening. CIRP J Manuf Sci Technol 2020, 28, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).