1. Introduction

Geothermal energy is a promising source of renewable and clean energy. However, the harsh conditions of geothermal environments pose significant challenges to the materials used in production equipment. In more recent years, drilling deeper geothermal wells considered to enhance the energy output up to 10 times higher than the conventional wells which then faced a variety of failures due to the higher temperature, lower pH, supercritical state of the geothermal fluid, higher corrosively, etc. [

1,

2]. These environments often contain high concentrations of solids, chloride ions, hydrogen sulphide (H

2S) and carbon dioxide (CO

2). Such conditions can be highly-corrosive to carbon and low-alloy steels, which are commonly used in geothermal wells [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Various mitigation strategies have been explored to overcome the failures due to the high corrosion susceptibility of carbon steel in such environment. Using corrosion-resistant alloys (CRAs) to mitigate corrosion is considered by several researchers [

7,

8,

9]. However, using CRAs are expensive and therefore using weld overlay/cladding is a more cost-effective alternative successfully applied in other energy industries. Inconel 625 and 316LSS are among the candidates known for good weldability and resistance to corrosion. Using CRA weld overlays offer better resistance to corrosion and erosion, whereas the backing steel provides appropriate mechanical properties such as high strength.

Laser cladding is an advanced technique for protecting underlying material using a deposition layer where a cladding material is deposited on a surface with a thermal energy supplied by laser beam [

10,

11,

12]. While wire-feed method is compatible with laser, most claddings use powder due to better versatility [

13,

14]. The overlay cladding is commonly used to enhance corrosion and tribological performance of the surface [

15,

16,

17].

The Extreme High-speed Laser Application (EHLA) process which is a state-of-the-art technology based on laser cladding can operate at ultra-high processing speeds. In EHLA, the laser focuses above the surface of the substrate which melts the metal powder mid-air. On reaching the substrate surface, the melted powder solidifies, and forms a metallurgically bonded coating [

18,

19]. The EHLA can achieve deposition rates of up to 200 m/min, with processing efficiencies approaching 500 cm

2/min [

20]. The high processing speed of this method allows large-scale fabrication to be carried out more economically, which is essential for its viability in the renewable energy sector.

While CRA overlays improve corrosion performance of the substrate material for geothermal applications, its effect on scale deposition rate and associated issues related to scaling is not very well understood. A range of factors influence the tendency for scale formation, including temperature as well as the presence and concentration of species such as silicon, calcium, carbonates, sulphates, and other heavy metal ions [

21]. The cladding material and surface roughness are some additional parameters that influence scaling in cladded surfaces.

This work examines the suitability of EHLA-produced corrosion-resistant alloy (CRA) overlays, namely Inconel 625 and 316 stainless steel, for service in high-silica geothermal environments. Particular attention is given to the role of surface condition (as-deposited versus polished) in governing corrosion behaviour and scaling tendencies under simulated geothermal exposure.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Manufacturing by EHLA

3.1.1. Inconel 625

The part manufactured to extract the coupons for the corrosion testing is shown in

Figure 1a. The disc diameter was 150mm and 10mm thick. Metallographic sections and corrosion coupons were extracted from this flat disc (i.e an example of the type of coupon used for the corrosion test is illustrated in orange in

Figure 1a, the coupons for the metallurgical examination were extracted transversal to this). The as-built cladding surface was analysed using a 3D microscopy and the roughness of the surface was Ra measured 5.7 μm.

3.1.2. EHLA 316L

As with Alloy 625, a 150 mm-diameter steel disc was used as the substrate for depositing the 316L EHLA cladding. The roughness of the as-built surface was Ra 7.3 μm. Note: For both 625 and 316L, the corrosion test coupons were carefully prepared to ensure that only the cladding surface was exposed, to avoid any influence of the steel base/substrate.

3.2. Microstructural Examinations

3.2.1. Inconel 625

The metallographic section extracted from the flat coupon was polished and etched appropriately. The revealed microstructure is shown in

Figure 2. The microstructure exhibits a primarily elongated columnar dendritic structure growing perpendicular to the interface with the average thickness of 442μm. The overlay exhibited a dense and uniform morphology, with no evidence of solidification cracking within the cladding material. However, some un-melted deposits were still present on the surface, indicating incomplete fusion in localized regions. High-magnification SEM imaging revealed distinct banding patterns consistent with elemental segregation, particularly of niobium and molybdenum, within the dendritic structure [

24].

3.2.2. 316 Stainless Steel

Figure 3 displays the revealed microstructure, which consists predominantly of elongated columnar dendrites aligned along the thickness of the cladding. The average measured thickness of the cladding layer is approximately 1240 μm. While the overlay appears generally dense, some linear and rounded features were observed. The linear indications are consistent with solidification cracks, whereas the rounded ones are likely due to porosity or non-metallic inclusions. SEM analysis of this sample showed a uniform microstructure with no signs of elemental segregation or significant amount of secondary phases.

3.3. Flow Rig Test

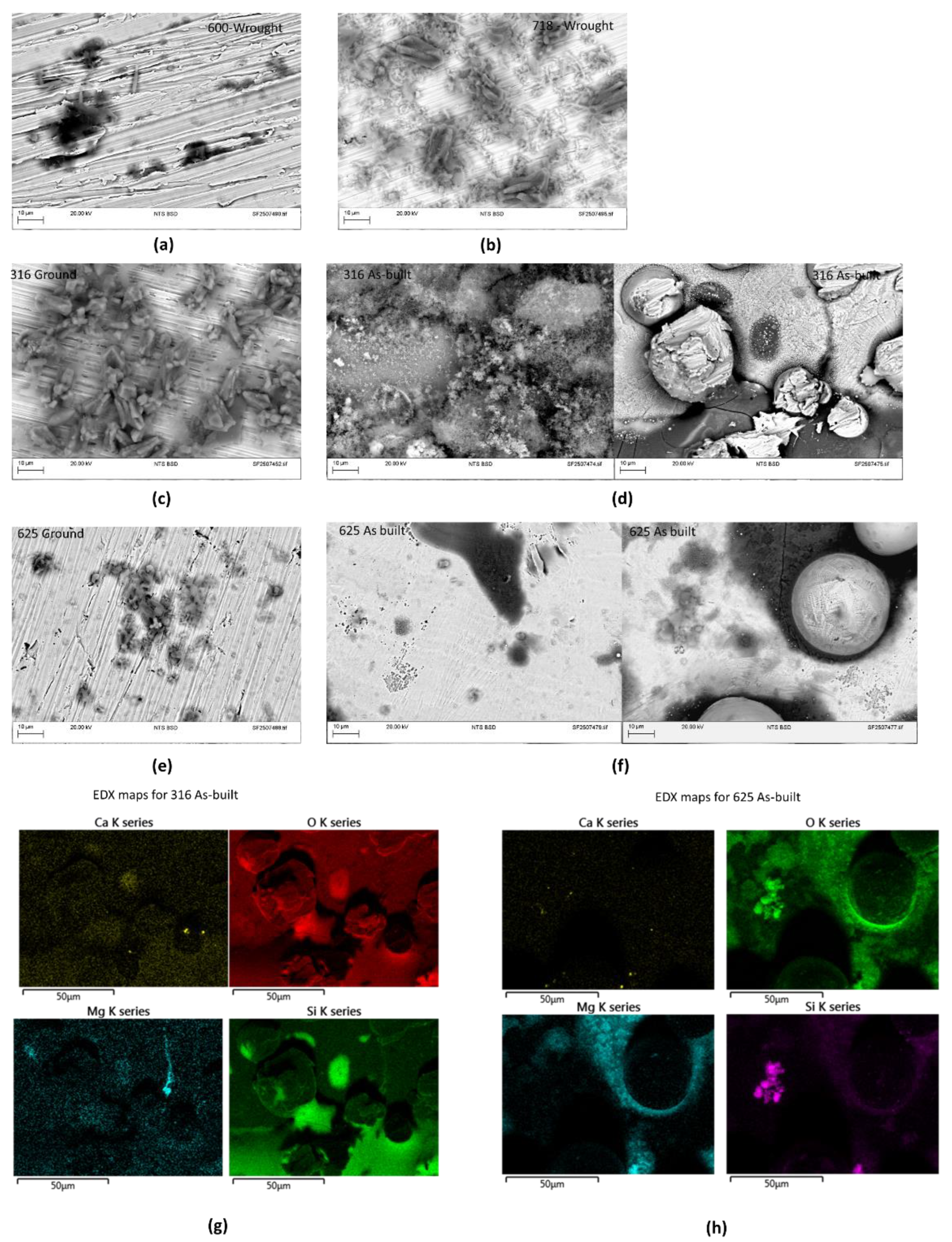

Figure 4 shows a comparison of the coupons before and after testing, while representative images of the SEM examination after testing are presented in

Figure 5. The surface of the coupons revealed varying degrees of surface alteration among the tested alloys. 316 as-built coupon showed a yellowish hue on the surface after testing with visible signs of surface degradation. SEM examination revealed extensive surface coverage by deposits, with the underlying metal exposed only in isolated areas. Remnants of the original powder particles were still present, and EDX spectra indicated silica, oxygen and magnesium scales (see

Figure 5g); notably, the dark region at the base of right-

Figure 5d corresponds to a silica-based scale.

The 316-ground coupon exhibited a noticeably darker appearance; however, the SEM image confirmed the absence of surface deterioration, with changes limited to scale formation. These scales were predominantly composed of silicon, oxygen, and magnesium, while other deposits rich in calcium and oxygen (with minor silicon content) were also observed.

Alloys 600 and 718 followed the same trend that was noticed in 625 ground sample, in particular, the EDX spectra of the scales of alloy 600 identified magnesium, silicon and oxygen as the principal elements. In 718, this type of scale was identified, but also with additional scales rich in calcium and oxygen. The coupon of alloy 625 (ground) was the one that displayed smaller amount of scaling.

For 625, the-as built sample showed no signs of surface degradation, although a significant layer of deposits was observed, primarily composed of magnesium and oxygen (this was the only sample that displayed significant amounts of this type of scale, see

Figure 5h). In ground condition, this alloy showed minimal surface change, with only a light layer of scale detected; EDX analysis identified magnesium, silicon, and oxygen as the principal elements in these scales, and no corrosion damage was evident.

The open circuit potential (OCP) measurements of the six tested materials 316 ground, 316 as-built, 625 ground, 625 as-built, 718, and 600 revealed a similar electrochemical shift during the early stages of exposure. Within the first 200 hours, all samples experienced a transition from more negative to more positive potentials, suggesting surface evolution likely linked to passive film formation or stabilization. Among these, the 316 as built specimen stands out due to the OCP values being consistently higher throughout the test, indicating that at least, from a thermodynamic point of view, the surface is more reactive. Meanwhile, the 316 ground sample, although displaying similar OCP values to the other materials, exhibited greater fluctuations in OCP, pointing to possible changes in the surface of the sample (i.e., local events of passive film breakdown and repassivation). The remaining alloys, 625 in both conditions, 718, and 600, showed relatively stable behavior after the initial 200 hours, with minor variations that suggest a steady electrochemical environment.

Figure 6.

Open circuit potential measurements versus the Ag/AgCl reference electrode for the six different coupons used during tests simulating the geothermal conditions.

Figure 6.

Open circuit potential measurements versus the Ag/AgCl reference electrode for the six different coupons used during tests simulating the geothermal conditions.

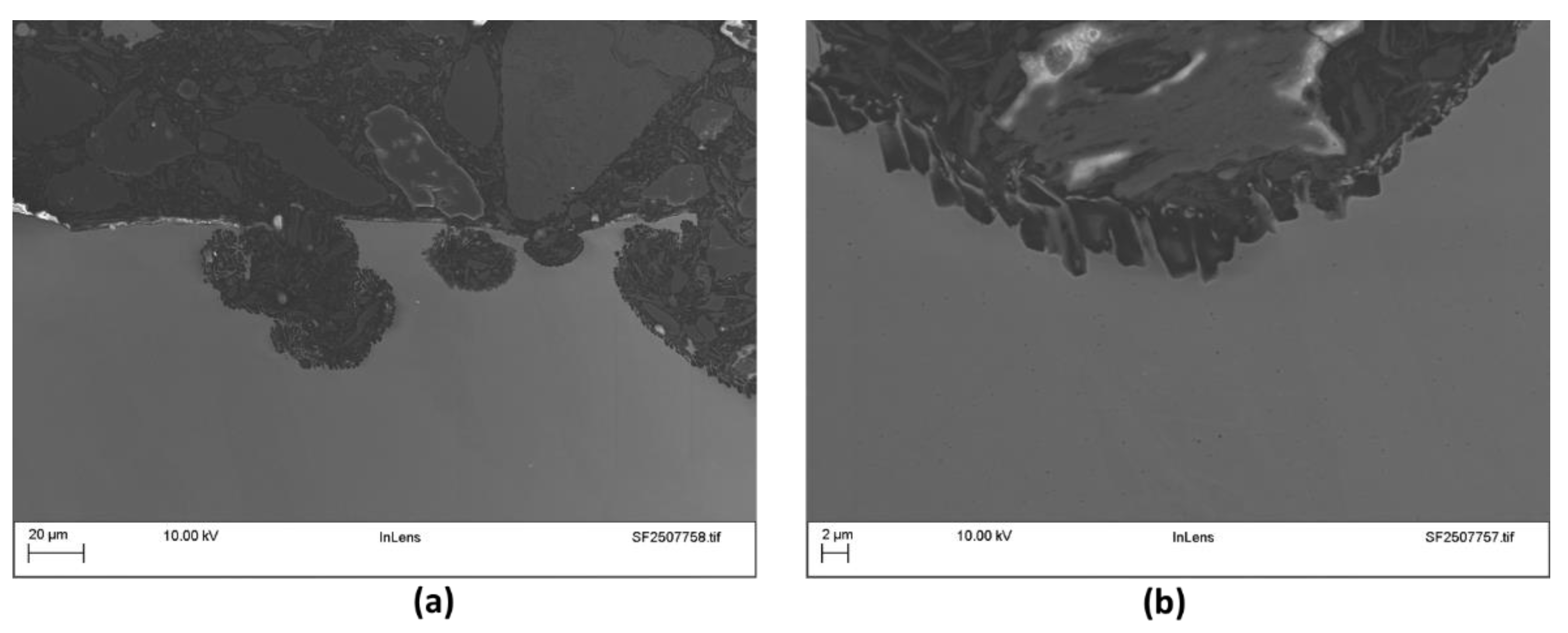

Figure 7 presents the cross-sectional view of the 316 as-built sample after testing. As expected for this alloy in a chloride-containing environment, the corrosion observed is localized, manifesting primarily as pitting.

Figure 7a highlights the development of secondary pits within existing surface pits, suggesting that despite the flow conditions during testing, localized concentration of aggressive species is occurring. This may occur due to the scales observed in the sample or due to un-melted surface particles that shield specific regions. At higher magnification (

Figure 7b), the pit bottom reveals a growth pattern that appears to follow the orientation of the dendritic microstructure. The pit propagation occurs in a toothed/serrated manner, indicating that the solidification structure of the as-built material influences the pitting growth.

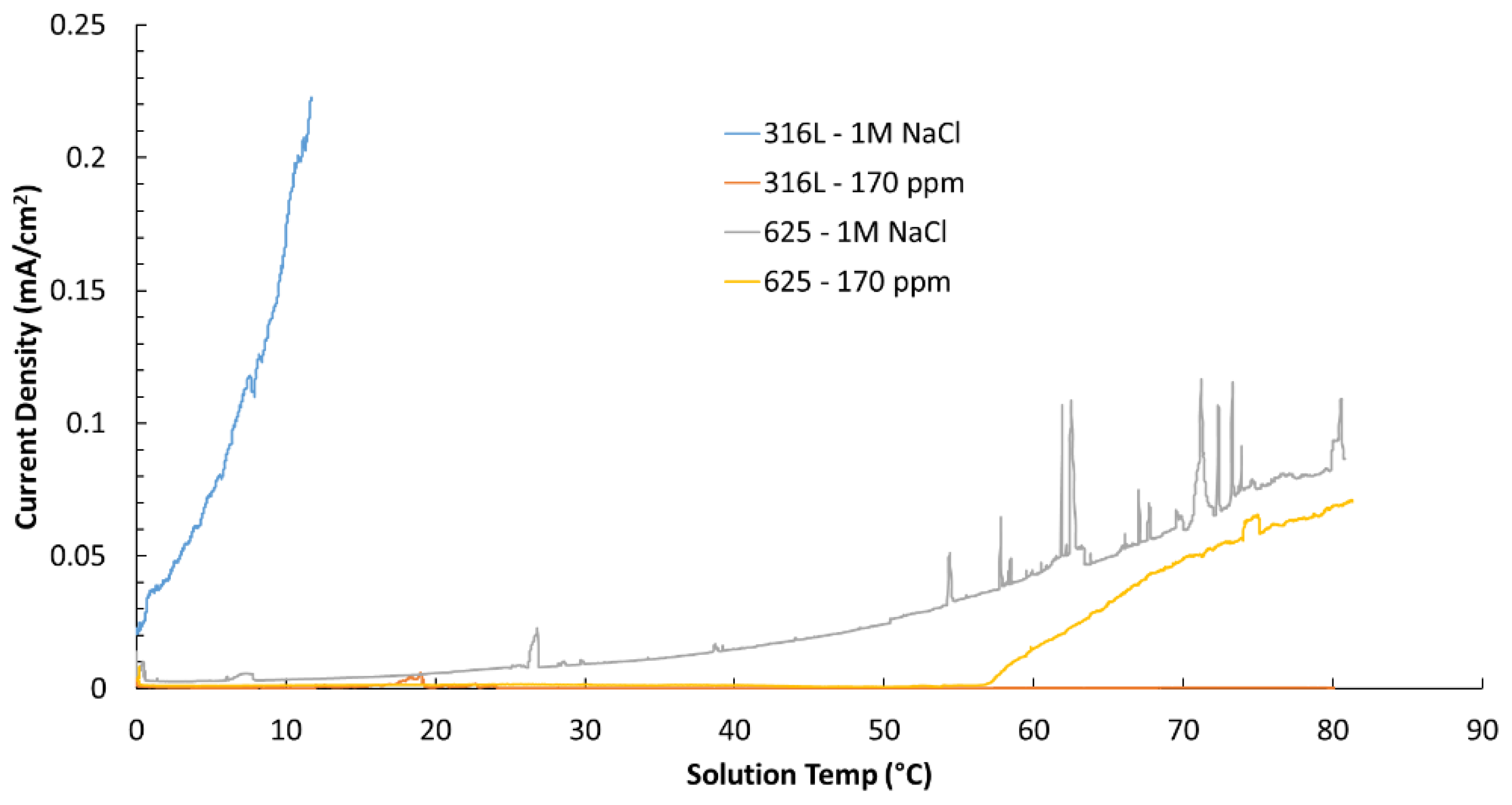

3.4. Critical Pitting Temperature

Table 2 shows a summary of the results of ASTM G150 tests. As expected, 625 displayed, in general, higher resistance to localized corrosion than 316, while, as expected again, the environment containing higher amount of chlorides proved to be more aggressive, compare the critical pitting temperature (CPT) of 316L in both environments. It was interesting to observe that the CPT of the EHLA 316L at the chloride concentration that could be identified in the geothermal well, the material was not susceptible to pitting corrosion up to a temperature of 80 °C (this was the temperature limit of the CPT testing rig), however different results were obtained in the tests simulating the geothermal conditions.

In addition to the G150 test results,

Figure 8 presents the current density versus time curves recorded during the tests. Although the 625 alloy successfully passed, the data reveal that the current generated during exposure to 170 ppm chloride concentration brine was higher than that observed for 316L. In absence of any other knowledge of the material, this is unexpected given the well-established superior corrosion resistance of alloy 625.

4. Discussion

First, it is important to highlight that the samples tested in their as-built condition exhibited higher surface roughness than the ground samples. This increased roughness results in a larger exposed surface area, which in turn leads to higher absolute current passing through the material during the corrosion tests. While this consideration might introduce some inconsistencies during the comparison of the results presented in this paper, it reflects a key advantage of additively manufactured (AM) parts- the potential to eliminate post-processing such as machining. This consideration is likely part of a broader discussion on the usage of AM parts. Nevertheless, this is the reason why, despite it could generate some inconsistencies during the comparison of the different results, the tests were performed in both conditions. The paper of Quok An teo et al. investigated the influence of different post-processing treatments in the surface finishes of AM 316L [

25], Clark et al. explore this influence directly in the corrosion performance of Laser beam powder bed fusion (LB-PBF) 316L, this research indicate that the influence of the surface finish is not given by the roughness of the part, rather, this is related to the surface chemistry [

26].

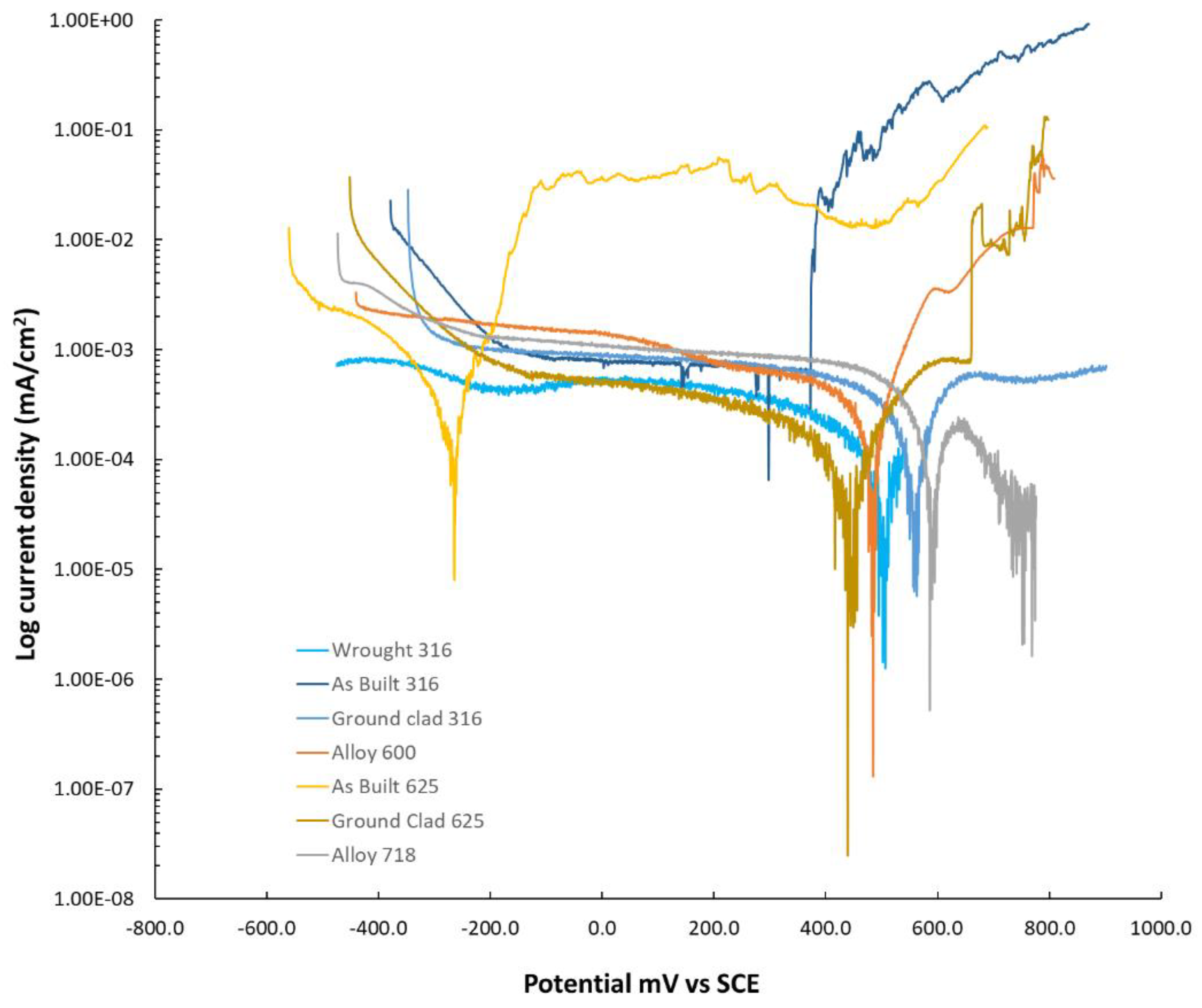

To facilitate understanding of the experimental findings, potentiodynamic sweeps were carried out in the geothermal brine. The results are shown in

Figure 9. Alloy 625 in the as-built condition exhibited the lowest OCP among the tested materials. This result is somewhat unexpected, as OCP typically reflects the thermodynamic tendency of a material to corrode. Among the alloys tested, 625 contains the least iron, which would suggest a higher OCP. However, the as-built 625 surface displayed several features detrimental to corrosion resistance, including high surface roughness, surface heterogeneities, and chemical segregation. These factors are likely to contribute to the unusually low OCP observed for this alloy. All the other alloys showed similar OCP values. In terms of I

corr, 316 as-built displayed the higher value, while all the alloy displayed relatively similar values. On the anodic side, ignoring as-built 625, it can be observed that 316L displayed the lower pitting potential, followed by alloy 600 and finally the ground 625. As expected, given the observation of the microstructure in 625, 718 displayed the lower current in the anodic site, and interestingly, we did not identify the pitting potential of 316 ground, suggesting that its pitting potential was higher than all the other alloys apart from 718. For 625 as-built, it would appear that the pitting potential is very low, however, a high current plateau can be observed.

If the results of the different tests are compared, no one-to-one correlation can be identified. For 316L as -built, the corrosion behavior in simulated geothermal brine at ~70 °C observed in this study confirms that this alloy is vulnerable to degradation under these conditions. The measured high i

corr, low pitting potential and the presence of localised pits/crevice attack detected by the post-exposure surface examination in the long-term tests indicate that the passive film of 316L is unstable in this environment. This finding is consistent with the established understanding that elevated temperatures (>55–60 °C) and high chloride concentrations promote passive film breakdown and accelerate localised corrosion processes in austenitic stainless steels. Microscopic examination revealed subsurface pits, nucleation of pits inside primary pits, and crevice-like attack under deposits/corrosion products, etc., which are characteristic of chloride-induced pitting corrosion. The initiation of pitting likely occurred due to localised de-passivation when chloride ions locally penetrated the thin chromium oxide film, establishing an anodic site. The measured OCP further supports this interpretation, showing a shift to more active potentials (or incursions). The potential presence of dissolved CO

2 in the simulated geothermal brine would further exacerbate this behavior, even without chlorides [

27]. This is supported by the results of the ASTM G150, which show that in a low chloride containing environment only current increase is observed It should ne noted that other factors might play a role as the flow. Also highlight the important of long term duration tests to assess materials corrosion performance. The synergistic interaction between chlorides and CO

2 at elevated temperature (~70C) creates an aggressive environment that possibly exceeds the materials’ resistance to corrosion in this condition [

28]. Likewise, the observations and measurements from 316 ground seem to be consistent, with high pitting potential and no pitting in the long duration tests. In the potentiodyamic tests, a conventionally manufactured 316L was tested, and show a similar behaviour, suggesting that the passive film of both alloys is very similar. Regarding the pit morphology found in 316L, although no chemistry segregation or secondary phases were identified, the structure at the bottom of the pits suggested that the pit growth is governed by the microstructure, Voisin et al. [

29] and Wang et al. [

30] studied the microstructure of laser powder bead fusion (LPBF) 316L in detail. They found that in this alloy, there is a cellular structure within the grains creating partitioning of the elements. This observation is compatible with the morphology of pit growth presented in this paper. No pit growth rate was established during this study, however, if this cellular structure leads to potentially higher corrosion rates To contrast this, Chao et al. [

34] found that in samples of 316L fabricated using selective laser melting (SLM), the pitting potential was higher in conventionally manufactured wrought 316L., then, it implicates that the qualification of AM material might require more detailed information that is generally used for wrought alloys. For example, the qualification of the materials might require macrographs, micrograph and advance microscopy imaging.

Regarding 625, despite no pitting or localized corrosion events being identified during the long terms tests, this indicated some corrosion related information such as the increase in current during the ASTM G150 or the poor behavior during the potentatidynamics scans. Differentiating them from their wrought counterpart. The differences can be rationalised by examining the unique microstructural characteristics imparted by the AM process. Unlike wrought material, which typically exhibits a more homogeneous, often equiaxed, and well-controlled microstructure, AM alloys are shaped by rapid solidification, localised melting, and layer-by-layer deposition, factors that promote microstructural heterogeneity, elemental segregation, and defect formation, all of which influence corrosion performance.

One of the primary contributors to this increased corrosion susceptibility is the non-homogeneous nature of deposit formation, as observed in

Figure 2d. For example, in previous long-duration tests in sulfuric acid have revealed shallow but distinct selective attack along melt pool borders, indicating that these features create local electrochemical inhomogeneities that accelerate localised corrosion processes in LPBF 625 [

31]. While wrought Alloy 625 generally forms equiaxed grains with more uniform chemistry, the layer-wise deposition in AM introduces melt pool boundaries and microsegregation that do not exist in conventionally processed material. Marchese et al. [

32] have found that within the microsegragation regions i.e., in the interdendritic regions, which are typically rich in elements such as niobium (Nb) and molybdenum (Mo), precipitates such as niobium carbides or gamma double prime are present. While no specific Mo-rich precipitates were identified During this research, it was found that the bands observed in

Figure 2d are rich in Niobium and molybdenum, no Cr enrichment was identified, it is well established that the precipitates deplete the adjacent gamma-Ni matrix of protective elements, reducing the resistance to localised corrosion. Porosity and other manufacturing defects further amplify this effect. Although laser-based methods typically achieve relatively low porosity, any residual voids, can serve as initiation points for corrosion attack. In contrast, wrought alloys typically exhibit no porosity, and precipitation of secondary phases typically occurs only after pro-longed exposure or poor heat treatment. This understanding, which enables effective control of sensitization in wrought alloys and has begun to be applied to conventional laser additive manufacturing (AM) processes [

33], still needs to be developed for EHLA-fabricated claddings.

In addition to the parameters discussed in this study, one critical aspect that was not characterized is the passive layer. The condition and integrity of the passive layer formed during EHLA (or in general for AM parts), compared to ground parts, remains unknown [

29]. A complete understanding of the corrosion behavior would benefit from further characterisation of the material’s composition, thickness, and electrochemical properties. Without this, the conclusions from the corrosion tests remain preliminary.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P., E.A.E. and D.M.; methodology, T.M., E.A.E. and D.M.; software, E.A.E. and D.M.; validation, E.A.E. and D.M.; formal analysis, E.A.E. and D.M; investigation, E.A.E., T.M. and D.M; resources, N.K., E.A.E. and S.P.; data curation, E.A.E. and D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M., E.A.E. and S.P.; writing—review and editing, D.M., N.K., E.A.E. and S.P.; visualization, D.M. and E.A.E.; supervision, N.K. and S.P.; project administration, N.K.; funding acquisition, N.K. and S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Photographs of the EHLA-deposited claddings, showing the steel substrate at the center and the outer ring of the samples: (a) 625 and (b) 316L.

Figure 1.

Photographs of the EHLA-deposited claddings, showing the steel substrate at the center and the outer ring of the samples: (a) 625 and (b) 316L.

Figure 2.

The cross-sectional micrographs of EHLA Alloy 625 coating: (a) and (b) are light optical images showing some macro-characteristics of the microstructure, (c) SEM image showing unfused deposits on the cladding surface and (d) high magnification backscatter SEM image showing the segregation features.

Figure 2.

The cross-sectional micrographs of EHLA Alloy 625 coating: (a) and (b) are light optical images showing some macro-characteristics of the microstructure, (c) SEM image showing unfused deposits on the cladding surface and (d) high magnification backscatter SEM image showing the segregation features.

Figure 3.

The cross-sectional micrographs of EHLA 316 stainless steel cladding: (a) and (b) are light optical images showing some characteristics of the microstructure, including some flaws.

Figure 3.

The cross-sectional micrographs of EHLA 316 stainless steel cladding: (a) and (b) are light optical images showing some characteristics of the microstructure, including some flaws.

Figure 4.

Visual assessment of the coupons before and after 30 days of testing. Remember, Inconel alloy 600 and 718 were used from wrought materials, therefore no as-built coupons exited.

Figure 4.

Visual assessment of the coupons before and after 30 days of testing. Remember, Inconel alloy 600 and 718 were used from wrought materials, therefore no as-built coupons exited.

Figure 5.

Representative images obtained from the SEM-EDX analysis of the surface of the samples after testing: (a) Inconel alloy 600, (b) 718, (c) 316 ground, (d) 316 as-built, (e) 625 ground, (f) 625 as-built, (g) EDX-maps of calcium, oxygen, magnesium and silica for 718 as built and (h) EDX-maps of calcium, oxygen, magnesium and silica for 625 as built.

Figure 5.

Representative images obtained from the SEM-EDX analysis of the surface of the samples after testing: (a) Inconel alloy 600, (b) 718, (c) 316 ground, (d) 316 as-built, (e) 625 ground, (f) 625 as-built, (g) EDX-maps of calcium, oxygen, magnesium and silica for 718 as built and (h) EDX-maps of calcium, oxygen, magnesium and silica for 625 as built.

Figure 7.

Cross-sectional micrographs of the stainless steel (316L) as-built coupons used in the flow-rig tests.

Figure 7.

Cross-sectional micrographs of the stainless steel (316L) as-built coupons used in the flow-rig tests.

Figure 8.

Current density versus temperature graph generated during the ASTM G150 tests.

Figure 8.

Current density versus temperature graph generated during the ASTM G150 tests.

Figure 9.

Potentiodynamic scans carried out in simulated geothermal brine at elevated temperature (70 °C).

Figure 9.

Potentiodynamic scans carried out in simulated geothermal brine at elevated temperature (70 °C).

Table 1.

Process parameters employed during cladding deposition for the specimens used in the corrosion tests.

Table 1.

Process parameters employed during cladding deposition for the specimens used in the corrosion tests.

| Material |

Spot Size

(mm) |

Laser Power

(kW) |

Speed

(m/min) |

Powder Feed rate

(g/min) |

Feeder

(RPM) |

Pitch % |

Pitch

(mm) |

| 625 |

3 |

2 |

10 |

15 |

1.1 |

80 |

0.4 |

| 316L |

3 |

2.5 |

10 |

25 |

4.6 |

70 |

0.48 |

Table 2.

Results of the ASTM G150 tests and modified G150 tests with lower chloride concentration.

Table 2.

Results of the ASTM G150 tests and modified G150 tests with lower chloride concentration.

| Material |

Environment |

CPT value |

| 316L |

1M NaCl |

7.7 °C |

| 316L |

170 ppm chloride |

>80 °C |

| 625 |

1M NaCl |

>80 °C |

| 625 |

170 ppm chloride |

>80 °C |