Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Kritik Der Reinen Erfahrung

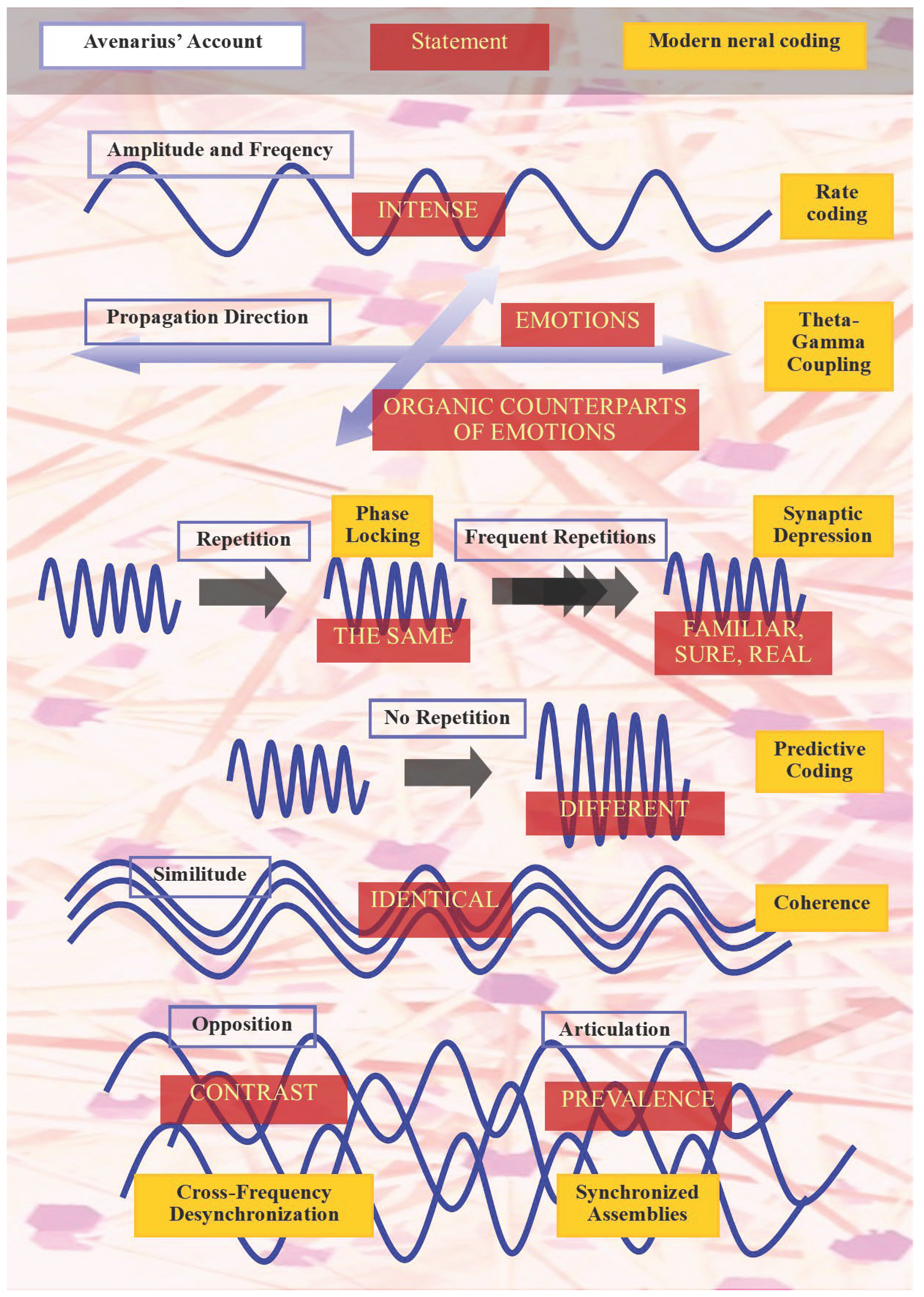

- In §§ [458–462], Avenarius analyzes how the form and magnitude of brain oscillations determine the qualities and intensities of sensory experience. The form of oscillation depends both on external conditions (stimuli) and on the specific preparation of the central system. By varying these conditions, different perceptual elements arise, such as light, sound, color, taste or odor. For instance, heating a filament produces “light,” vibrating a piano string generates “sound,” and applying cologne on the skin evokes a “burning” sensation. The magnitude of oscillation, in contrast, determines intensity: a stronger vibration produces a louder tone, brighter light or more vivid sensation. Avenarius concludes that perceptual quality depends on the form of oscillation, while intensity depends on its amplitude.

- In §§ [463–469], Avenarius examines how the relevance and direction of brain oscillations determine emotional life and bodily expression. An oscillation is considered more relevant when it is both large in magnitude and involves central subsystems with high physiological or experiential significance—shaped by individual predisposition and habitual practice. The resulting variations evoke affective responses, expressed as pleasure or displeasure. For example, a mother’s anxiety for a sick child, an artist’s frustration at a ruined color or a scientist’s excitement over a new discovery all reflect oscillations of different relevance and scope. Pleasure arises when oscillatory processes restore equilibrium between “work” and “nourishment,” while displeasure follows imbalance.

- In §§ [466–469], Avenarius introduces the notion of a value of indifference, the threshold where pleasure turns into displeasure, inspired by Wundt’s psychophysiology. He interprets emotional tone as a function of oscillatory direction: an increase in relevant oscillations produces displeasure, while a decrease generates pleasure. These rhythmic variations manifest physiologically through motor and visceral changes like muscle tension, breathing patterns, heart rate, sweating or warmth, each corresponding to specific oscillatory configurations. Thus, affective experience is not an added property of consciousness but an intrinsic modulation of oscillatory processes linking movement, sensation and emotion within a unified dynamic system.

- In §§ [471–477], Avenarius explores the dependence of transexcitation, describing how oscillations in one sensory or motor subsystem can propagate through others, producing complex experiential effects. Sensations such as dizziness, shock or loss of balance arise from sudden oscillatory transfers within the central system. He cites Billroth’s anecdote of a soprano singing off-key, which caused a sharp toothache, an example of co-affective dependence where an auditory stimulus triggers a physiological reaction elsewhere. Avenarius distinguishes between proper feelings (directly related to one’s own oscillatory processes) and improper feelings (arising from cross-system propagation). Through repeated excitation, oscillations can deviate from their habitual form, producing a qualitative sense of “otherness”. This character manifests when the individual perceives difference, such as moving to a new country, learning a foreign language or encountering unfamiliar art. In contrast, when oscillations revert to their previous pattern, an individual sense of restored sameness and identity is achieved, captured in expressions such as “it’s just the same.”. Avenarius summarizes these relationships by describing the polarity of experiential differentiation that links novelty, familiarity and emotional tone to dynamic oscillatory processes of the nervous system.

- In §§ [478–498] Avenarius examines how exercise shapes oscillatory dependence and introduces a family of characters that grade experience between novelty and sameness. He defines Idential as the intermediate value that varies with transexcitation. Exercise of oscillations gives rise to a character of Fidentiality, the felt familiarity of well-practiced patterns exemplified by Heimat, whose deprivation elicits homesickness. When a less exercised oscillation is imposed on the nervous system, the opposed character emerges as Unfamiliarity, seen in reactions to cadavers by novice students, to stage tricks or to erratic social behavior. Fidentiality decomposes into three specific characters: reality, security and familiarity. Their unity often appears in everyday compounds such as the known road, the trusted physician or native currency. Avenarius traces how practice modulates these values: when exercise decreases, they drift toward their negative counterparts such as insecurity and attenuation, passing through a point of indifference. He details cultural and temporal modulations in which the present feels maximally real, the distant or past less so and copies, images and dreams hold reduced existential weight; yet repeated engagement can raise their existential value. He then outlines how social practice establishes what counts as normal, while unusual biological or social cases appear strange and how repeated exposure converts the strange into the familiar.

- In §§ [499–502] Avenarius analyzes the dependence of the articulation of fluctuations. The nervous system shifts from relative uniformity of internal links toward finer differentiation, where gradual change raises internal articulation while abrupt change can weaken cohesion. Formal separation picks out from a continuous whole, the specific “new work” and the part currently in focus: the workbench becomes distinct from the room, the corrected letter from the line, the striking advertisement from the page. What becomes formally separated gains prevalence; what recedes becomes a dead value, later recoverable by memory or by pedagogical maneuvers that vary familiar conditions (pointing, rearranging, naming). Excessive separation yields over-separation (confusion, disorder). Avenarius stresses that prevalence is not intensity: a loud letterform can be intense yet not prevail over content, while content may prevail with moderate intensity. Prevalence arises from changes against previously constant conditions and can decline if change is too slow or too slight. Habituation converts earlier separations into dead values (the miller ceases to hear the mill; silence becomes the separated value). Conversely, confused complexes can become separated through practice (a bustling city becomes comprehensible; Wagner’s overture shifts from chaos to lucid structure). Avenarius then tackles the principle of opposition of fluctuations. Material contrasts heighten mutual distinctness: complementary colors differentiate each other, bright stands out from dark, loud from quiet, heavy from light; analogous oppositions structure affect (joy against pain, love against hate) and life-world judgments (home against foreign). Yet contrasts have limits. If gaps are too large or too abrupt, prevalence collapses into confusion, stupor or blinding. The graded management of transitions in teaching and communication therefore regulates articulation and preserves comprehension. He concludes that contrast depends on the opposition of fluctuations, which enhances material distinctness within certain limits, but beyond those limits breaks articulation down into confusion and loss of structure.

2. The Neural Code

- Rate coding mechanisms encode information in the average firing rate of neurons over time. In firing rate coding, the number of spikes per unit time represents stimulus intensity, with higher firing rates typically corresponding to stronger stimuli (Gallistel 2017; Tomar 2019; Zhu et al., 2025). Time-averaged rate coding smooths neural activity over a time window to reduce variability in spike timing, while Poisson rate coding treats spike generation as a probabilistic process, where the rate parameter itself carries the information (Satuvuori and Kreuz, 2018; Liu et al., 2021).

- Temporal coding mechanisms rely on the precise timing of spikes. In spike timing coding, the exact moment a spike occurs relative to an internal or external reference carries meaning, as in first-spike latency (Li et al., 2018; Beckert et al.; Chen et al., 2024). Phase coding represents information through the timing of spikes within an oscillatory cycle, such as theta-phase alignment in the hippocampus (Seenivasan and Narayanan, 2020; Pacheco Estefan et al., 2021). Temporal pattern coding uses specific sequences of spikes to convey information (Madar et al., 2019), while interspike interval coding relies on the time between spikes to represent stimulus properties (Oswald et al., 2007; Koyama and Kostal, 2014). Synchrony coding occurs when groups of neurons fire simultaneously to signal the presence or relevance of a stimulus (Person and Raman, 2012; Baker et al., 2015; Rezaei et al., 2023)

- Population coding mechanisms involve distributed activity across multiple neurons (Georgopoulos et al., 1986; Runyan et al., 2017; Downer et al., 2017; LeMessurier and Feldman, 2018; Levitan et al., 2019; Downer et al., 2021; Stringer et al., 2021). In distributed coding, information is represented collectively by many neurons rather than by single units. Sparse coding makes use of small subsets of neurons, creating efficient representations. Vector coding models population responses as vectors in high-dimensional space, while basis function coding describes neural responses as components capable of representing arbitrary inputs. Redundancy reduction coding distributes information in a way that minimizes overlap and enhances efficiency.

- Correlation-based coding emphasizes interactions among neurons (Hong et al., 2012; Fox and Stryker, 2017; Montijn et al., 2014; Azeredo da Silveira and Rieke, 2021; Dora, et al. 2021; Tschantz et al., 2023; Zeng et al., 2023; Millidge et al., 2024). Population synchrony refers to correlations in firing across neurons that shape how information is encoded. Noise correlation coding focuses on correlated variability in responses, while Hebbian coding describes learning through the strengthening of correlated activity, exemplified by spike-timing-dependent plasticity.

- Predictive and Bayesian coding mechanisms treat neural computation as probabilistic inference (Aitchison and Lengyel, 2017; Bonetti et al., 2021; Pezzulo et al., 2022; Caucheteux et al., 2023; Lange et al., 2023; Chao et al., 2024; Taniguchi 2024). In Bayesian coding, neural populations represent probability distribution over sensory or cognitive variables. Predictive coding proposes that the brain continuously generates expectations about incoming inputs and adjusts them through error signals. The free energy principle unifies these perspectives by suggesting that the brain reduces uncertainty through internal modeling of expected sensory states.

- Specialized coding mechanisms apply to sensory or motor systems. Place coding in the hippocampus represents spatial position, while grid coding in the entorhinal cortex maps locations in a hexagonal grid (Mallory and Giocomo, 2018; Herzog et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2024). Opponent coding describes systems that encode information through contrasting signals, as in color vision (Buchsbaum and Gottschalk, 1983; Derey et al., 2016; Rhodes et al., 2017; Hagihara and Lüthi, 2024). Rank order coding conveys information through the sequence in which neurons fire and time-to-first-spike coding uses the delay from stimulus onset to the first action potential as a signal (Bonilla et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023; Sakemi et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2024; Li et al., 2024).

- Hybrid coding schemes combine multiple strategies depending on function and context. Multiplexed coding integrates distinct mechanisms such as rate and phase coding to convey different aspects of information simultaneously (Baker et al., 2013; Hong et al., 2016; Ke et al., 2022; Hovhannisyan et al., 2023). Hierarchical coding organizes information processing in successive stages of increasing abstraction, as seen in the visual pathway from V1 to the inferotemporal cortex (Chen 2023; Gwilliams et al., 2025).

3. Parallels Between Avenarius’ Vital Trains and Modern Neural Codes

- In rate coding, the number of spikes or the oscillatory power within a frequency band represents stimulus intensity; higher firing rates or stronger gamma-band amplitudes correspond to stronger stimuli, echoing Avenarius’[455,459–475 “magnitude” ([461]).

- The form of oscillation corresponds to waveform structure and spectral composition underlying temporal and resonance-based models of information processing.

- Finally, the direction of oscillation could match with, e.g., frontal alpha asymmetry correlating with emotional polarity and theta–gamma coupling distinguishing between positive and negative valence.

- Predictive coding interprets repeated stimuli as generating attenuated neural responses (a reduction in prediction error) much like Avenarius’ description of oscillatory convergence toward equilibrium.

- In rate and temporal coding, repetition reduces firing variability and sharpens spike-timing precision, increasing signal efficiency.

- The free-energy principle formalizes this process mathematically, describing how cortical circuits minimize the divergence between predicted and actual input (Kullback–Leibler divergence), a direct computational analogue of Avenarius’ “restoration” phase.

- Moreover, the emergence of “identity” through synchronized oscillations corresponds to phase locking and coherence, i.e., neural phenomena now regarded as signatures of perceptual binding and conscious unity.

- This model of contrast through opposition corresponds closely to contemporary theories of selective attention based on oscillatory competition, in which attention depends on the dynamic regulation of synchrony and desynchrony among neural populations.

- According to the communication-through-coherence hypothesis, synchronized assemblies amplify relevant information, whereas desynchronized activity is suppressed. This may stand for a functional analogue of Avenarius’ crucial concept of “extraction of a prevalent part from the background.”

- Furthermore, anti-phase coupling and cross-frequency desynchronization provide mechanisms for sensory discrimination and attentional gating, reflecting Avenarius’ observation that oscillatory opposition sharpens contrast and enhances awareness.

- Modern neuroscience identifies comparable principles in population coding and vector coding, where distributed patterns of neuronal activity across large ensembles represent complex sensory or cognitive objects. Each concept may correspond to a stable attractor within the multidimensional state space of neural dynamics.

- The transition from repeated sensory oscillations to higher-level abstraction parallels the hierarchical organization of predictive models, in which recurrent associations generate more general predictive structures.

- Avenarius’ insight that generality results from the recurrence of identical oscillatory patterns seems to anticipate the Hebbian plasticity (“neurons that fire together wire together”) and Bayesian abstraction, in which probabilistic integration across repeated experiences yields conceptual knowledge.

- This cyclical pattern maps directly onto the predictive-coding loop of modern neuroscience that comprises top-down predictions, bottom-up error signals and feedback corrections able to minimize free energy.

- The “pain of uncertainty” and “pleasure of certainty” may correspond to the dopaminergic reward and error signals that modulate learning and behavioral adaptation.

- Furthermore, Avenarius’ assertion that the final equilibrium is independent of the number of intermediate steps ([857]) parallels recurrent neural network convergence, where dynamic systems settle into stable attractors regardless of the complexity of their transient paths.

- In modern terms, this account describes the brain’s tendency toward homeostatic regulation and efficient coding, where synaptic scaling maintains stable firing statistics and redundancy reduction optimizes informational efficiency.

- Similarly, plasticity mechanisms allow substitutional learning, ensuring that changing inputs still produce coherent representations.

- Avenarius’ search for universal oscillatory laws prefigures computational neuroscience’s emphasis on compression and generalization, principles that also underpin deep learning networks.

- This duality parallels the modern separation between dynamic neural activity and representational structure. In population and hybrid coding schemes, form may correspond to transient activity patterns, while content to stable network configurations. The dependence on individual history anticipates experience-dependent plasticity, whereby learning refines neural coding through long-term synaptic modification.

- Notably, Avenarius’ claim that imagined or hallucinatory experiences correspond to real oscillatory content ([961]) finds confirmation in modern neuroimaging studies showing that visual imagery activates cortical regions similar to those engaged during perception.

- This dynamic equilibrium corresponds to modern concepts of homeodynamic regulation, metastability and self-organized criticality in neural systems. Current models describe perception and cognition as trajectories through high-dimensional state spaces seeking temporary stability, i.e., energy minima, while maintaining flexibility for adaptation. This is effectively Avenarius’ “quiet, maximum-preservation state,” in which the organism sustains informational balance through rhythmic readjustment.

4. Towards Yet-Undiscovered Principles of Neural Coding

5. Conclusions: Lessons from the Past

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, Omar J. and Sydney S. Cash. “Finding Synchrony in the Desynchronized EEG: The History and Interpretation of Gamma Rhythms.” Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 7 (August 12, 2013): 58. [CrossRef]

- Aitchison, L., and M. Lengyel. “With or Without You: Predictive Coding and Bayesian Inference in the Brain.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 46 (October 2017): 219–227. [CrossRef]

- Avenarius, Richard. Kritik der reinen Erfahrung. 2 vols. Leipzig: Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann, 1888–1890.

- Azeredo da Silveira, R., and F. Rieke. “The Geometry of Information Coding in Correlated Neural Populations.” Annual Review of Neuroscience 44 (July 8, 2021): 403–424. [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. A., T. Kohashi, A. M. Lyons-Warren, X. Ma, and B. A. Carlson. “Multiplexed Temporal Coding of Electric Communication Signals in Mormyrid Fishes.” Journal of Experimental Biology 216, no. 13 (July 1, 2013): 2365–2379. [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. A., Huck, K. R., and Carlson, B. A. “Peripheral Sensory Coding through Oscillatory Synchrony in Weakly Electric Fish.” eLife 4 (August 4, 2015): e08163. [CrossRef]

- Beckert, M. V., Fischer, B. J., and Peña, J. L. “Effect of Stimulus-Dependent Spike Timing on Population Coding of Sound Location in the Owl’s Auditory Midbrain.” eNeuro 7, no. 2 (April 23, 2020): ENEURO.0244-19.2020. [CrossRef]

- Berger, Hans. “Über das Elektrenkephalogramm des Menschen.” Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 87 (1929): 527–570. [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, L., J. Gautrais, S. Thorpe, and T. Masquelier. “Analyzing Time-to-First-Spike Coding Schemes: A Theoretical Approach.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 16 (September 26, 2022): 971937. [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, L., S. E. P. Bruzzone, N. A. Sedghi, N. T. Haumann, T. Paunio, K. Kantojärvi, M. Kliuchko, P. Vuust, and E. Brattico. “Brain Predictive Coding Processes Are Associated to COMT Gene Val158Met Polymorphism.” NeuroImage 233 (June 2021): 117954. [CrossRef]

- Buchsbaum, G., and A. Gottschalk. “Trichromacy, Opponent Colours Coding and Optimum Colour Information Transmission in the Retina.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 220, no. 1218 (November 22, 1983): 89–113. [CrossRef]

- Caton, Richard. “The Electric Currents of the Brain.” British Medical Journal 2 (1875): 278. http://echo.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/MPIWG:4917F9YN.

- Caucheteux, C., A. Gramfort, and J. R. King. “Evidence of a Predictive Coding Hierarchy in the Human Brain Listening to Speech.” Nature Human Behaviour 7, no. 3 (March 2023): 430–441. [CrossRef]

- Chao, Z. C., M. Komatsu, M. Matsumoto, K. Iijima, K. Nakagaki, and N. Ichinohe. “Erroneous Predictive Coding across Brain Hierarchies in a Non-Human Primate Model of Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Communications Biology 7, no. 1 (July 12, 2024): 851. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. S. “Hierarchical Predictive Coding in Distributed Pain Circuits.” Frontiers in Neural Circuits 17 (March 3, 2023): 1073537. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Karilanova, S., Chaki, S., Wen, C., Wang, L., Winblad, B., Zhang, S. L., Özçelikkale, A., and Zhang, Z. B. “Spike Timing-Based Coding in Neuromimetic Tactile System Enables Dynamic Object Classification.” Science 384, no. 6696 (May 10, 2024): 660–665. [CrossRef]

- Coenen, Anton, Zayachkivska, Oksana. “Adolf Beck: A Pioneer in Electroencephalography in Between Richard Caton and Hans Berger.” Advances in Cognitive Psychology 9, no. 4 (December 31, 2013): 216–221. [CrossRef]

- Derey, K., G. Valente, B. de Gelder, and E. Formisano. “Opponent Coding of Sound Location (Azimuth) in Planum Temporale Is Robust to Sound-Level Variations.” Cerebral Cortex 26, no. 1 (January 2016): 450–464. [CrossRef]

- Dora, S., S. M. Bohte, and C. M. A. Pennartz. “Deep Gated Hebbian Predictive Coding Accounts for Emergence of Complex Neural Response Properties Along the Visual Cortical Hierarchy.” Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 15 (July 28, 2021): 666131. [CrossRef]

- Downer, J. D., Niwa, M., and Sutter, M. L. “Hierarchical Differences in Population Coding within Auditory Cortex.” Journal of Neurophysiology 118, no. 2 (August 1, 2017): 717–731. [CrossRef]

- Downer, J. D., Bigelow, J., Runfeldt, M. J., and Malone, B. J. “Temporally Precise Population Coding of Dynamic Sounds by Auditory Cortex.” Journal of Neurophysiology 126, no. 1 (July 1, 2021): 148–169. [CrossRef]

- Falcone, R., Weintraub, D. B., Setogawa, T., Wittig, J. H. Jr, Chen, G., and Richmond, B. J. “Temporal Coding of Reward Value in Monkey Ventral Striatal Tonically Active Neurons.” Journal of Neuroscience 39, no. 38 (September 18, 2019): 7539–7550. [CrossRef]

- Fox, K., and M. Stryker. “Integrating Hebbian and Homeostatic Plasticity: Introduction.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 372, no. 1715 (March 5, 2017): 20160413. [CrossRef]

- Friston, K., J. Kilner, and L. Harrison. “A Free Energy Principle for the Brain.” Journal of Physiology Paris 100, nos. 1–3 (July–September 2006): 70–87. [CrossRef]

- Geadah, V., Barello, G., Greenidge, D., Charles, A. S. and Pillow, J. W. “Sparse-Coding Variational Autoencoders.” Neural Computation 36, no. 12 (November 19, 2024): 2571–2601. [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulos, A. P., Schwartz, A. B., and Kettner, R. E. “Neuronal Population Coding of Movement Direction.” Science 233, no. 4771 (September 26, 1986): 1416–1419. [CrossRef]

- Gwilliams, L., A. Marantz, D. Poeppel, and J. R. King. “Hierarchical Dynamic Coding Coordinates Speech Comprehension in the Human Brain.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 122, no. 42 (October 21, 2025): e2422097122. [CrossRef]

- Hagihara, K. M., and A. Lüthi. “Bidirectional Valence Coding in Amygdala Intercalated Clusters: A Neural Substrate for the Opponent-Process Theory of Motivation.” Neuroscience Research 209 (December 2024): 28–33. [CrossRef]

- Hemmatian, B., L. R. Varshney, F. Pi, and A. K. Barbey. “The Utilitarian Brain: Moving beyond the Free Energy Principle.” Cortex 170 (January 2024): 69–79. [CrossRef]

- Herzog, L. E., L. M. Pascual, S. J. Scott, E. R. Mathieson, D. B. Katz, and S. P. Jadhav. “Interaction of Taste and Place Coding in the Hippocampus.” Journal of Neuroscience 39, no. 16 (April 17, 2019): 3057–3069. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S., M. Negrello, M. Junker, A. Smilgin, P. Thier, and E. De Schutter. “Multiplexed Coding by Cerebellar Purkinje Neurons.” eLife 5 (July 26, 2016): e13810. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S., S. Ratté, S. A. Prescott, and E. De Schutter. “Single Neuron Firing Properties Impact Correlation-Based Population Coding.” Journal of Neuroscience 32, no. 4 (January 25, 2012): 1413–1428. [CrossRef]

- Hovhannisyan, H., A. Rodríguez, E. Saus, M. Vaneechoutte, and T. Gabaldón. “Multiplexed Target Enrichment of Coding and Non-Coding Transcriptomes Enables Studying Candida spp. Infections from Human Derived Samples.” Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 13 (January 24, 2023): 1093178. [CrossRef]

- Huetz, C., Souffi, S., Adenis, V. and Edeline, J. M. “Neural Code: Another Breach in the Wall?” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 42 (November 28, 2019): e232. [CrossRef]

- Jazayeri, M. and Afraz, A. “Navigating the Neural Space in Search of the Neural Code.” Neuron 93, no. 5 (March 8, 2017): 1003–1014. [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, K. J. “How Environmental Movement Constraints Shape the Neural Code for Space.” Cognitive Processing 22, suppl. 1 (September 2021): 97–104. [CrossRef]

- Joiret, M., Leclercq, M., Lambrechts, G., Rapino, F., Close, P., Louppe, G. and Geris, L. “Cracking the Genetic Code with Neural Networks.” Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 6 (April 6, 2023): 1128153. [CrossRef]

- Ke, J. C., X. Chen, W. Tang, M. Z. Chen, L. Zhang, L. Wang, J. Y. Dai, J. Yang, J. W. Zhang, L. Wu, Q. Cheng, S. Jin, and T. J. Cui. “Space-Frequency-Polarization-Division Multiplexed Wireless Communication System Using Anisotropic Space-Time-Coding Digital Metasurface.” National Science Review 9, no. 11 (October 18, 2022): nwac225. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., A. Kahana, R. Yin, Y. Li, P. Stinis, G. E. Karniadakis, and P. Panda. “Rethinking Skip Connections in Spiking Neural Networks with Time-To-First-Spike Coding.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 18 (February 14, 2024): 1346805. [CrossRef]

- Koyama, S., and Kostal, L. “The Effect of Interspike Interval Statistics on the Information Gain under the Rate Coding Hypothesis.” Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering 11, no. 1 (February 2014): 63–80. [CrossRef]

- Lange, R. D., S. Shivkumar, A. Chattoraj, and R. M. Haefner. “Bayesian Encoding and Decoding as Distinct Perspectives on Neural Coding.” Nature Neuroscience 26, no. 12 (November 23, 2023): 2063–2072. [CrossRef]

- LeMessurier, A. M., and Feldman, D. E. “Plasticity of Population Coding in Primary Sensory Cortex.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 53 (December 2018): 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Levitan, D., Lin, J. Y., Wachutka, J., Mukherjee, N., Nelson, S. B., and Katz, D. B. “Single and Population Coding of Taste in the Gustatory Cortex of Awake Mice.” Journal of Neurophysiology 122, no. 4 (October 1, 2019): 1342–1356. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Xie, K., Kuang, H., Liu, J., Wang, D., Fox, G. E., Shi, Z., Chen, L., Zhao, F., Mao, Y., and Tsien, J. Z. “Neural Coding of Cell Assemblies via Spike-Timing Self-Information.” Cerebral Cortex 28, no. 7 (July 1, 2018): 2563–2576. [CrossRef]

- Li, F., D. Li, C. Wang, G. Liu, R. Wang, H. Ren, Y. Tang, Y. Wang, Y. Chen, K. Liang, Q. Huang, M. Sawan, M. Qiu, H. Wang, and B. Zhu. “An Artificial Visual Neuron with Multiplexed Rate and Time-to-First-Spike Coding.” Nature Communications 15, no. 1 (May 1, 2024): 3689. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., V. C. H. Leung, and P. L. Dragotti. “First-Spike Coding Promotes Accurate and Efficient Spiking Neural Networks for Discrete Events with Rich Temporal Structures.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 17 (October 2, 2023): 1266003. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Wang, Y., and Zhao, H. “Calculating Orthologous Protein-Coding Sequence Set Probability Using the Poisson Process.” Journal of Computational Biology 28, no. 10 (October 2021): 961–974. [CrossRef]

- Lu, W. “Bayesian Brain Computing and the Free-Energy Principle: An Interview with Karl Friston.” National Science Review 11, no. 5 (January 17, 2024): nwae025. [CrossRef]

- Madar, A. D., Ewell, L. A., and Jones, M. V. “Temporal Pattern Separation in Hippocampal Neurons Through Multiplexed Neural Codes.” PLoS Computational Biology 15, no. 4 (April 22, 2019): e1006932. [CrossRef]

- Mallory, C. S., and L. M. Giocomo. “Heterogeneity in Hippocampal Place Coding.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 49 (April 2018): 158–167. [CrossRef]

- Millidge, B., M. Tang, M. Osanlouy, N. S. Harper, and R. Bogacz. “Predictive Coding Networks for Temporal Prediction.” PLoS Computational Biology 20, no. 4 (April 1, 2024): e1011183. [CrossRef]

- Montijn, J. S., M. Vinck, and C. M. Pennartz. “Population Coding in Mouse Visual Cortex: Response Reliability and Dissociability of Stimulus Tuning and Noise Correlation.” Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 8 (June 2, 2014): 58. [CrossRef]

- Oswald, A. M., Doiron, B., and Maler, L. “Interval Coding. I. Burst Interspike Intervals as Indicators of Stimulus Intensity.” Journal of Neurophysiology 97, no. 4 (April 2007): 2731–2743. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco Estefan, D., Zucca, R., Arsiwalla, X., Principe, A., Zhang, H., Rocamora, R., Axmacher, N., and Verschure, P. F. M. J. “Volitional Learning Promotes Theta Phase Coding in the Human Hippocampus.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118, no. 10 (March 9, 2021): e2021238118. [CrossRef]

- Person, A. L., and Raman, I. M. “Synchrony and Neural Coding in Cerebellar Circuits.” Frontiers in Neural Circuits 6 (December 11, 2012): 97. [CrossRef]

- Pezzulo, G., T. Parr, and K. Friston. “The Evolution of Brain Architectures for Predictive Coding and Active Inference.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 377, no. 1844 (February 14, 2022): 20200531. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M. R., Saadati Fard, R., Popovic, M. R., Prescott, S. A., and Lankarany, M. “Synchrony-Division Neural Multiplexing: An Encoding Model.” Entropy 25, no. 4 (March 30, 2023): 589. [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, G., S. Pond, L. Jeffery, C. P. Benton, A. L. Skinner, and N. Burton. “Aftereffects Support Opponent Coding of Expression.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 43, no. 3 (March 2017): 619–628. [CrossRef]

- Runyan, C. A., Piasini, E., Panzeri, S., and Harvey, C. D. “Distinct Timescales of Population Coding across Cortex.” Nature 548, no. 7665 (August 3, 2017): 92–96. [CrossRef]

- Sakemi, Y., K. Yamamoto, T. Hosomi, and K. Aihara. “Sparse-Firing Regularization Methods for Spiking Neural Networks with Time-to-First-Spike Coding.” Scientific Reports 13, no. 1 (December 21, 2023): 22897. [CrossRef]

- Satuvuori, E., and Kreuz, T. “Which Spike Train Distance Is Most Suitable for Distinguishing Rate and Temporal Coding?” Journal of Neuroscience Methods 299 (April 1, 2018): 22–33. [CrossRef]

- Seenivasan, P., and Narayanan, R. “Efficient Phase Coding in Hippocampal Place Cells.” Physical Review Research 2, no. 3 (September 11, 2020): 033393. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., Bi, D., Hesse, J. K., Lanfranchi, F. F., Chen, S. and Tsao, D. Y. “Rapid, Concerted Switching of the Neural Code in Inferotemporal Cortex.” bioRxiv [Preprint] (December 13, 2023): 2023.12.06.570341. [CrossRef]

- Sokoloski, S., Aschner, A. and Coen-Cagli, R. “Modelling the Neural Code in Large Populations of Correlated Neurons.” eLife 10 (October 5, 2021): e64615. [CrossRef]

- Stringer, C., Michaelos, M., Tsyboulski, D., Lindo, S. E., and Pachitariu, M. “High-Precision Coding in Visual Cortex.” Cell 184, no. 10 (May 13, 2021): 2767–2778.e15. [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, T. “Collective Predictive Coding Hypothesis: Symbol Emergence as Decentralized Bayesian Inference.” Frontiers in Robotics and AI 11 (July 23, 2024): 1353870. [CrossRef]

- Tomar, R. “Review: Methods of Firing Rate Estimation.” Biosystems 183 (September 2019): 103980. [CrossRef]

- Tschantz, A., B. Millidge, A. K. Seth, and C. L. Buckley. “Hybrid Predictive Coding: Inferring, Fast and Slow.” PLoS Computational Biology 19, no. 8 (August 2, 2023): e1011280. [CrossRef]

- Vallortigara, G., and G. Vitiello. “Brain Asymmetry as Minimization of Free Energy: A Theoretical Model.” Royal Society Open Science 11, no. 7 (July 31, 2024): 240465. [CrossRef]

- Yuste, R. “Breaking the Neural Code of a Cnidarian: Learning Principles of Neuroscience from the ‘Vulgar’ Hydra.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 86 (June 2024): 102869. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C., S. Zhao, B. Chen, A. Zeng, and S. Li. “Feature-Correlation-Aware History-Preserving-Sparse-Coding Framework for Automatic Vertebra Recognition.” Computers in Biology and Medicine 160 (June 2023): 106977. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Q., V. Puliyadi, X. Chen, J. L. Lee, L. Y. Zhang, and J. J. Knierim. “Vector Coding and Place Coding in Hippocampus Share a Common Directional Signal.” Nature Communications 15, no. 1 (December 5, 2024): 10630. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H., He, F., Zolotavin, P., Patel, S., Tolias, A. S., Luan, L., and Xie, C. “Temporal Coding Carries More Stable Cortical Visual Representations Than Firing Rate Over Time.” Nature Communications 16, no. 1 (August 4, 2025): 7162. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).