1. Introduction

John von Neumann’s concept of the universal constructor introduced a foundational vision: that machines could not only construct other machines, but also reproduce and evolve — much like biological organisms do [

1]. This led to the development of cellular automata [

2], where discrete units evolve according to local update rules. Conway’s Game of Life is a well-known example, demonstrating emergent complexity including self-replication and even universal computation [

3,

4]. Cellular automata have since been applied to modeling a range of natural phenomena, including crystallization and biological pattern formation [

5,

6].

While powerful, classical automata are inherently deterministic: each cell is either “on” or “off,” and the system evolves in a fully predictable manner. Quantum systems, by contrast, are governed by probabilistic dynamics and superposition. In quantum mechanics, state evolution is unitary, but measurement outcomes are inherently uncertain. Only recently have experimental advances begun to realize self-replicating behaviors in quantum systems [

7], and the theoretical exploration of quantum self-replication remains in its infancy.

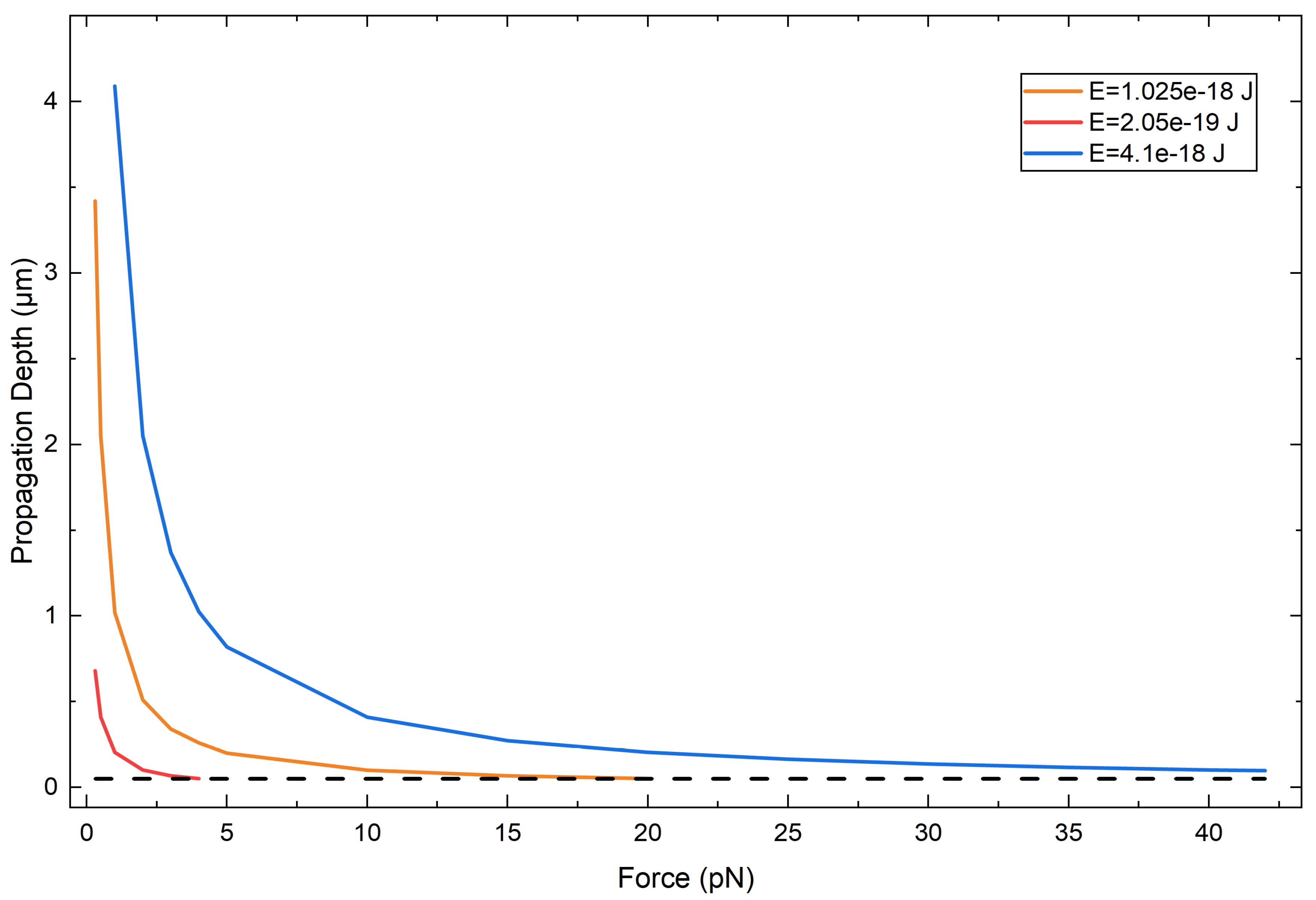

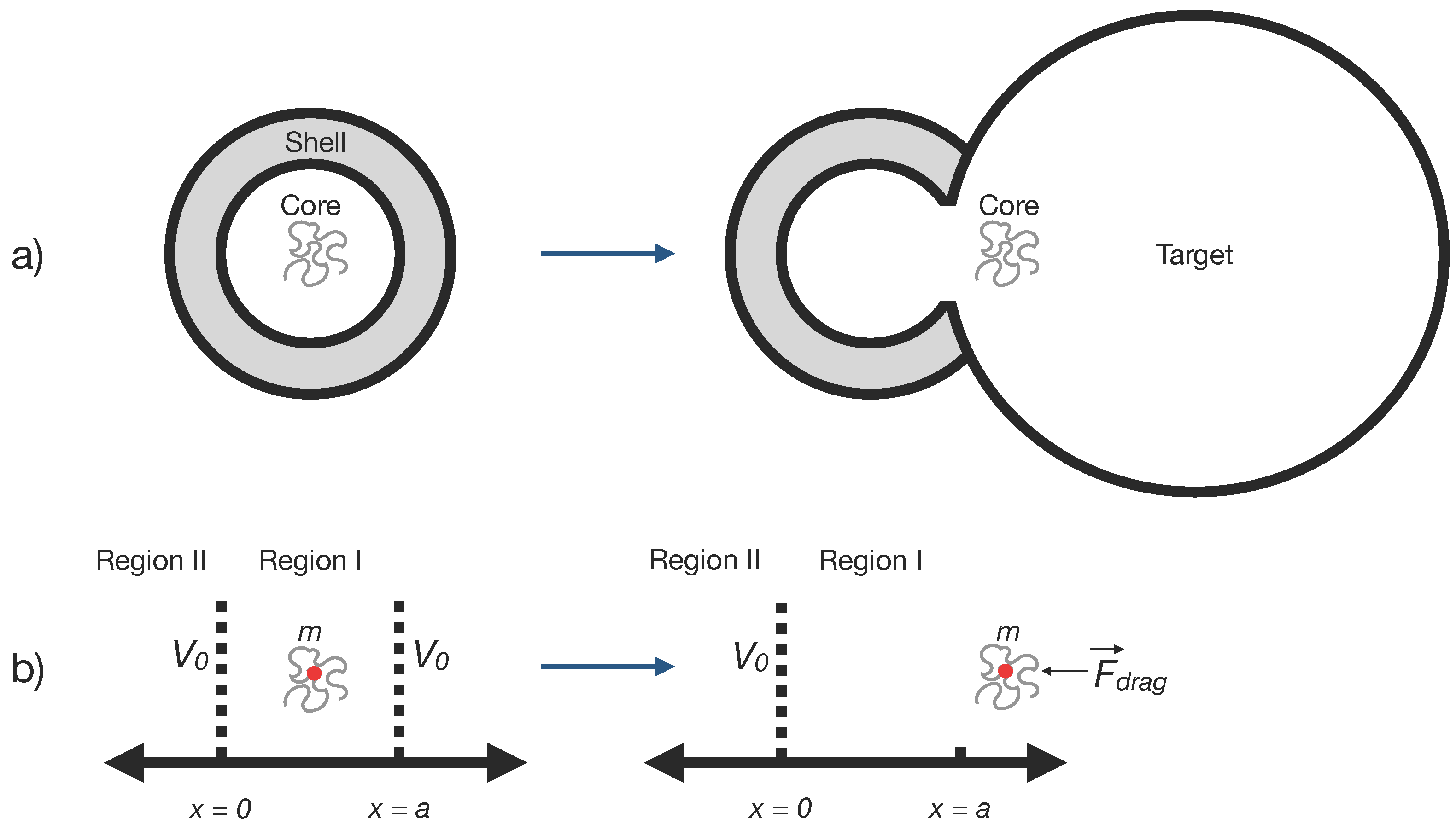

In this work, we develop a simplified quantum mechanical model of a reproducing system inspired by biological structures, particularly viruses. Our primary goal is not to provide a detailed mechanistic description of viral ejection, but to use this process as a natural example of confinement–release dynamics. We consider a core-shell particle confined in a finite potential well; at , the shell potential vanishes, allowing the ‘core’ wavepacket to propagate under the influence of an external force field representing environmental resistance. Using a split-operator method, we track the evolution of the wavepacket and compute replication intensity through a localized nonlinear interaction functional. The model exhibits clear scaling behavior: the propagation depth is set by the ratio of initial energy to resisting force, , with sharp suppression beyond this classical turning point. When the core reaches a designated target region, a field-theoretic interaction term triggers a replication event, modeled as the annihilation of the core and target followed by the creation of new core-shell systems. We model the process by numerically solving the time-dependent Schrödinger equation to quantify how propagation and overlap govern the replication probability.

Our model is biologically inspired: viruses inject their genomes (the core) from a capsid (the shell) into a host. The genome then travels within the host environment, potentially triggering replication. We adopt this terminology to convey intuition, but the model is broadly applicable to synthetic quantum systems capable of confinement, propagation, and interaction-triggered replication. Analogous processes of field-driven particle creation and amplification occur in several established areas of quantum physics. In high-energy theory, the Schwinger effect describes spontaneous electron–positron pair production from the quantum vacuum under a strong external field [

8,

9]. Likewise, the dynamical Casimir effect converts vacuum fluctuations into real photons when boundary conditions are rapidly modulated, as demonstrated experimentally in superconducting circuits [

10]. In engineered quantum simulators, coherent mode-splitting and population branching have been realized in optical lattices and superconducting platforms, such as the wave-packet branching through engineered conical intersections reported by Wang et al. [

11]. Related excitation-generation mechanisms also appear in analog gravity experiments, where effective spacetime curvature leads to Hawking-like emission in Bose–Einstein condensates [

12]. Across these diverse contexts, coherent particle creation arises through well-understood quantum field interactions that remain fully unitary.

Our model is solved numerically using a standard split-operator method for the time-dependent Schrödinger equation. A Gaussian wavepacket is released from the origin and evolves under the linear potential. The wavefunction exhibits characteristic Airy behavior, with the propagation depth determined by the classical turning point . We verify this behavior numerically and then introduce a nonlinear functional to represent a localized replication process. Finally, we reformulate the problem in the language of quantum field theory, where replication corresponds to a cubic interaction Hamiltonian. While the individual components of our analysis—Airy propagation under a linear potential and cubic interactions producing branching—are well-established, the novelty of this work lies in their synthesis into a unified, minimal model linking confinement, release, and replication-like branching. This provides a conceptual bridge between classical self-replication analogies and quantum field dynamics, rather than introducing new analytic results.

The paper is structured as follows: In Section I, we describe the free propagation of the quantum core following shell disintegration. Section II introduces the interaction Hamiltonian responsible for replication and presents the numerical simulation of this process. We conclude with discussion on physical interpretations, parameter scaling, and possible extensions of this minimal model toward more complex quantum replication frameworks.

3. Probability of Core Particle Reproduction

The single-particle Schrödinger equation provides a useful starting point for describing the propagation of the core after the shell breaks. However, once replication is allowed—that is, the creation of additional cores from an initial one—the single-particle formalism becomes insufficient because it assumes a fixed particle number. We note that in this work, the term replication refers strictly to the branching process; which corresponds to the annihilation of one excitation and creation of two others, analogous to parametric down-conversion or boson branching in standard field theory. It does not represent replication in an algorithmic or biological sense, nor does it imply information copying or self-replication of a quantum state. The purpose of this term is to introduce a minimal nonlinear channel that transforms single-particle amplitude into multi-particle probability density, serving as an analog of a “reproduction event” in a simplified physical system. To describe creation and annihilation events consistently, we adopt the framework of second quantization, or quantum field theory (QFT). In this approach, the wavefunction

is replaced by a field operator

, which can both create and destroy excitations of the core at position

x. The states of the system are then represented in Fock space, where the number of cores is not fixed but determined dynamically by the Hamiltonian. This transition allows replication to be modeled as an interaction term that converts one excitation into two, analogous to particle creation processes in nonlinear bosonic systems [

13,

14,

15,

16].

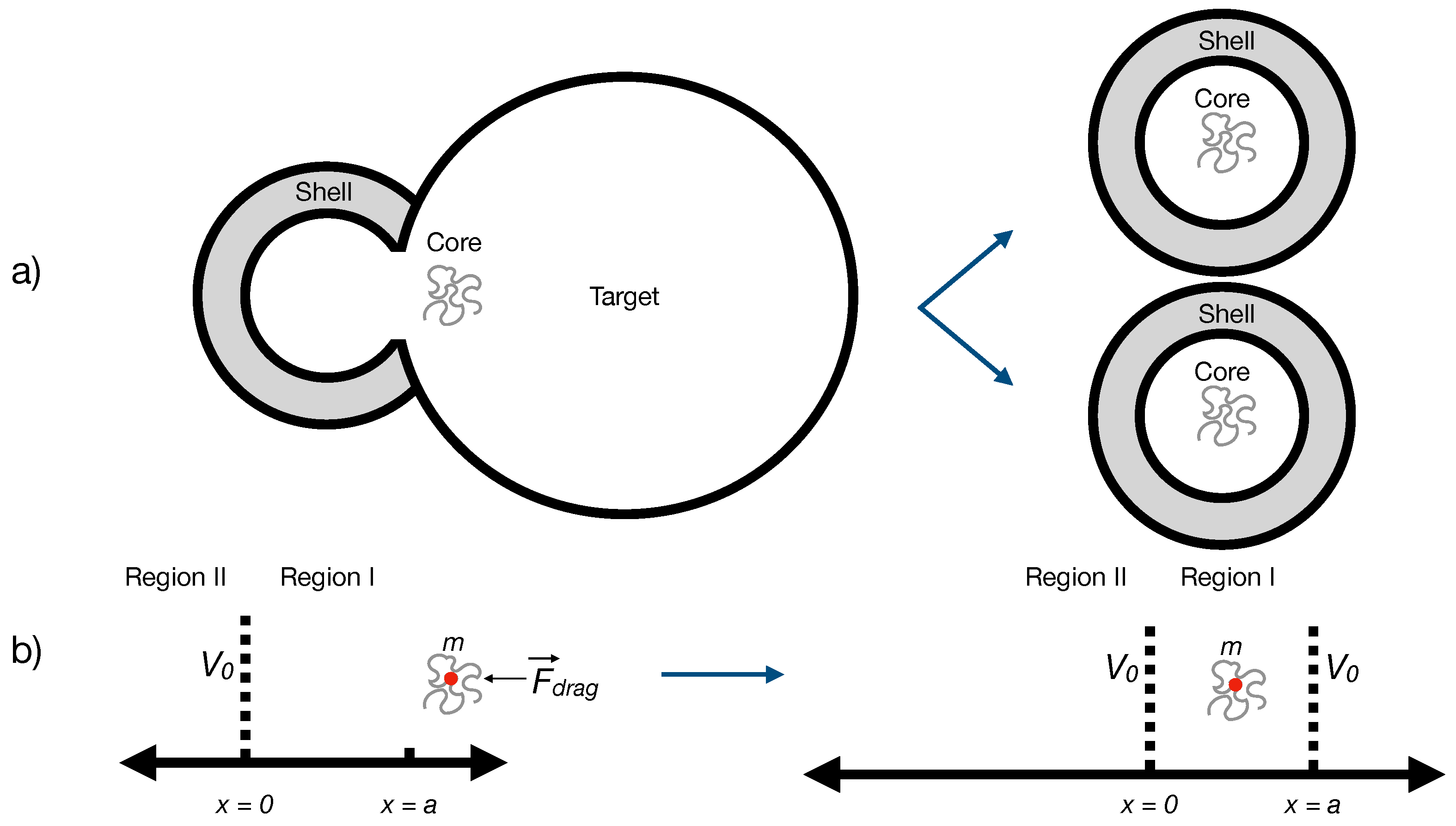

We describe the creation and destruction of the core particle using many-body quantum mechanics with creation and annihilation operators. When the core encounters a target (“cell”), both are annihilated to form two (or more) new particles identical to the core. This process is analogous to a virus infecting a cell: the virus and cell are transformed to yield multiple new viruses.

Fig. 3 shows a schematic of this step. For simplicity, we set length units of

and

.

Let be the creation operator for a core-shell particle (or simply ’core’) with energy E; that is, the state , where the vacuum (no genome) state is defined by (the vacuum is denoted by ), and is the annihilation operator, the adjoint of the creation operator. These operators satisfy the commutation relation , and mode normalization .

Given this background we want to construct the Hamiltonian for a free core that is drifting to the right under a retarding force

F due to the medium the core finds itself in. That is to say, at time

the shell collapses, revealing a core of size

a and mass

m, described by a wave function

, which then drifts to the right a distance

D at which point it encounters a cell. The Hamiltonian for this part of the process is given by

so that a one-particle wave packet

evolves consistently with the Schrödinger equation.

We introduce the bosonic field operator

This field and its conjugate obey the commutation relations

For the interacting Hamiltonian we take the cell to be located a distance

from where the shell broke and assume that the cell supplies energy

to the core to create two new cores, each of mass

m. Then the interacting Hamiltonian that annihilates the core to create two new cores with the help of the energy supplied by the cell is

where

is a coupling strength and

is a normalized finite-range kernel centered at zero, e.g.

The kernel ensures that replication occurs only when the core overlaps the localized interaction region.

This cubic term is the lowest-order local bosonic interaction capable of annihilating one excitation and creating two, thus representing the minimal form of a replication event.

Energy conservation is enforced through oscillatory time factors in the interaction-picture operator ; after coarse-graining, these contribute an effective constant that encodes daughter overlaps and energy-matching conditions. To obtain probabilities, one must also compute a matrix element such as , where is the two core-shell state and the original core-shell state propagated near the cell.

For

, we assume the core inside the shell can be represented by a Gaussian of "size"

a. After the shell breaks the core wave function evolves according to Equation

11 until it drifts close to a cell at position

. In the interaction picture, the leading-order amplitude to generate two daughter cores from an initial one-particle packet is

Which reduces to

where

is the amplitude of a single particle and

collects daughter-mode overlaps and energy-matching factors.

A practical expression is obtained by coarse-graining over long times and internal daughter states. Under a Markov approximation one finds a replication rate density

The probability that replication occurs during a single passage is obtained by integrating the rate over the passage time window,

The derivation leading to Eq. (20) assumes that variations of the interaction kernel occur on time scales much slower than the intrinsic oscillations of the wavefunction. Dimensional consistency is preserved by requiring , ensuring that the interaction term contributes an energy density to the Hamiltonian. The prefactors and were chosen for qualitative illustration rather than quantitative calibration. A full treatment would require solving the coupled field equations self-consistently, which lies beyond the present heuristic scope.

In principle, replication could be modeled as an interaction between two distinct fields — one representing the core and another representing a target structure or “environmental receptor.” However, in the minimal model considered here, the target is not treated as a dynamic degree of freedom but rather as a static background potential or localized interaction region. This approximation is justified when the target is much heavier, slower, or otherwise unaffected by the replication event, so that its quantum state can be effectively integrated out. Similar effective-field descriptions are widely used in reaction–diffusion and birth–death models, where the medium or catalyst is treated implicitly rather than as a separate dynamical entity [

15,

16].

Nondimensionalization: To make the dynamics more transparent, we rescale lengths and times using the natural Airy scales of a particle in a constant force. The characteristic length is

and the corresponding time scale is

We define dimensionless variables

The dimensionless Schrödinger equation for the free propagation becomes

with the turning point at .

In these units, the replication rate density simplifies to

where

is the dimensionless kernel and

is a dimensionless overlap constant. Thus, the problem is governed primarily by the ratios

(energy-to-force scale),

(potential offset), and

(interaction range). This reduction shows that replication probability depends only on a small set of dimensionless parameters, rather than the absolute values of

m,

F, and

E.

Validity and Limitations: Our formulation is deliberately minimal and therefore subject to several important limitations:

Perturbative validity. All results are derived at leading (Born) order in the coupling . This approximation is valid as long as the replication probability per passage satisfies . In this regime back-reaction and higher-order multiparticle processes can be neglected. For larger or repeated passages, one would require a full kinetic or master-equation treatment.

Finite interaction range. The replacement of a pointlike by a finite kernel regularizes the interaction and introduces the physically meaningful length scale . Predictions depend weakly on over a broad range, but a full microscopic model would be needed to determine it quantitatively.

Energy supply. Replication requires an external energy input, modeled here phenomenologically by the coupling constant and overlap factor (, k). The “cell” or reservoir that supplies this energy is not explicitly included in the Hamiltonian. In a more complete description, one would couple the core particle to an explicit bath or ancilla system.

No-cloning consistency. The daughters are created in a fixed, prepared internal state determined by the vertex. The process does not clone an arbitrary unknown quantum state and is therefore consistent with the quantum no-cloning theorem.

Dimensional reduction. The model treats only the one-dimensional center-of-mass motion of the core. Internal degrees of freedom, orientation, and environmental decoherence are neglected. Inclusion of these effects would modify quantitative outcomes but not the qualitative dependence on the control ratios , and .

Closed-system assumption. The present treatment assumes coherent Schrödinger evolution up to the replication event. In realistic biological or experimental systems, coupling to an environment would introduce decoherence and dissipation. A Lindblad or master-equation extension would be required to capture these effects.

Simulation Setup: The time-dependent Schrödinger equation was solved using the standard split-operator Fourier method with absorbing boundary conditions [

17]. The algorithm is unitary and well-suited for smooth potentials; details of the implementation are provided in Appendix A. The spatial domain was taken as

with

(dimensionless units), discretized on a uniform grid of

points. The time step was chosen as

, and wavefunction snapshots were stored every 20 time steps for subsequent post-processing. This ensures adequate resolution both in configuration and momentum space while keeping numerical dispersion and Trotter splitting errors negligible on the simulated time scales.

The initial state was a normalized Gaussian wavepacket,

with initial position , width , and central wavenumber . These parameters correspond to an initial kinetic energy and a classical turning point at , where F is the constant force associated with the linear potential. Unless stated otherwise, we used , , and to work in fully nondimensionalized units.

The potential was taken as

so that the wavepacket initially propagates in the positive x-direction and decelerates until reaching the turning point, reproducing the Airy-like behavior characteristic of a particle in a uniform field.

with

was used to model the localized interaction with a target placed at position

. For each stored time step, the integral

The intensity was calculated for a range of values and the intensity was plotted as a function of and the time to obtain heatmaps of replication intensity.

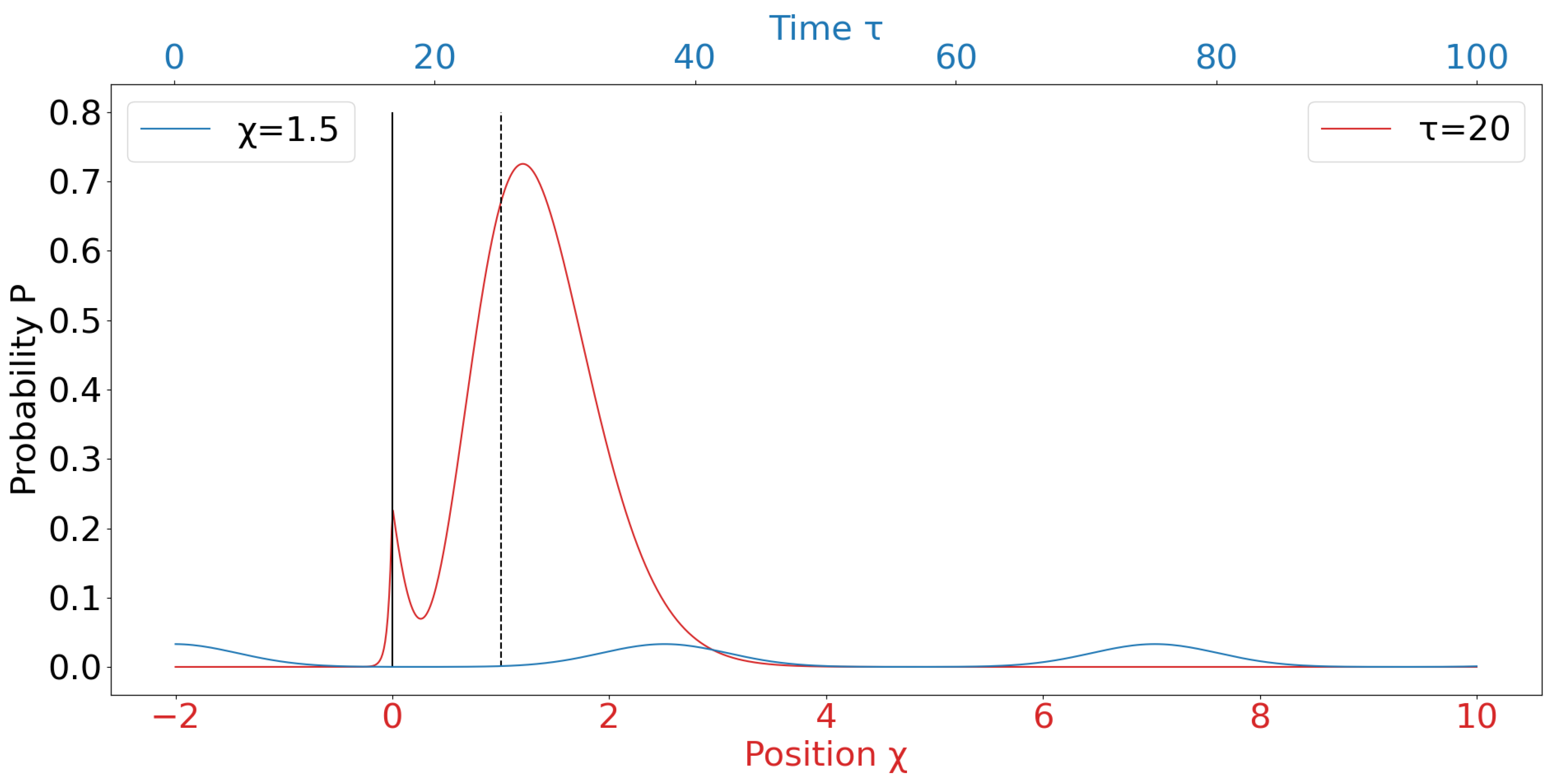

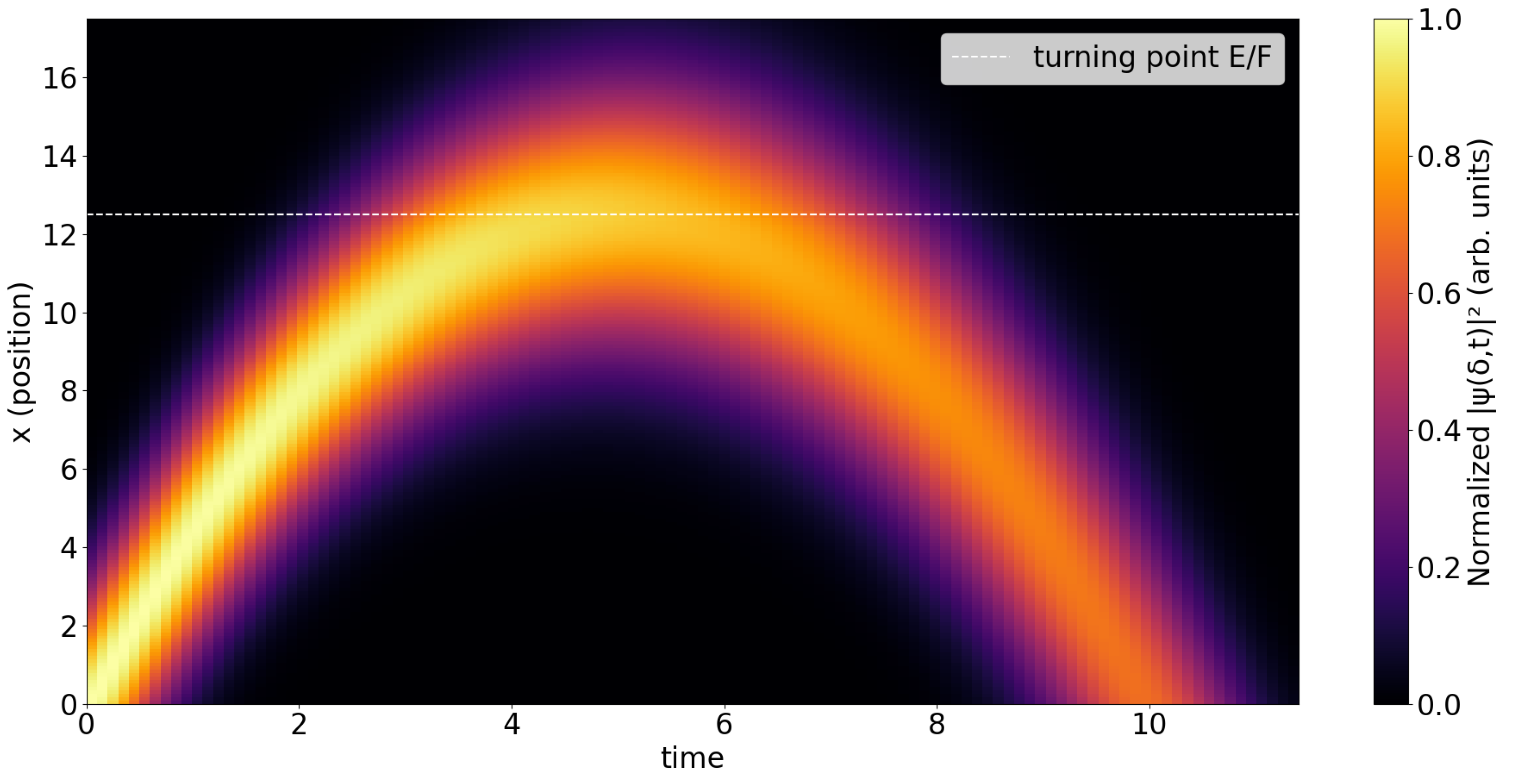

Fig. 4 shows the probability density heatmap,

which reveals the parabolic trajectory of the wavepacket’s center of mass under the linear potential. The diagonal structure (from initial position toward the turning point) corresponds to the classical propagation of the wavepacket, while the gradual spreading reflects dispersion. The bright parabolic structure corresponds to the classical propagation of the wavepacket under a linear potential. The arrival time at each x increases monotonically, as expected for ballistic motion with constant acceleration. The signal diminishes after the turning point, where the wavepacket is reflected.

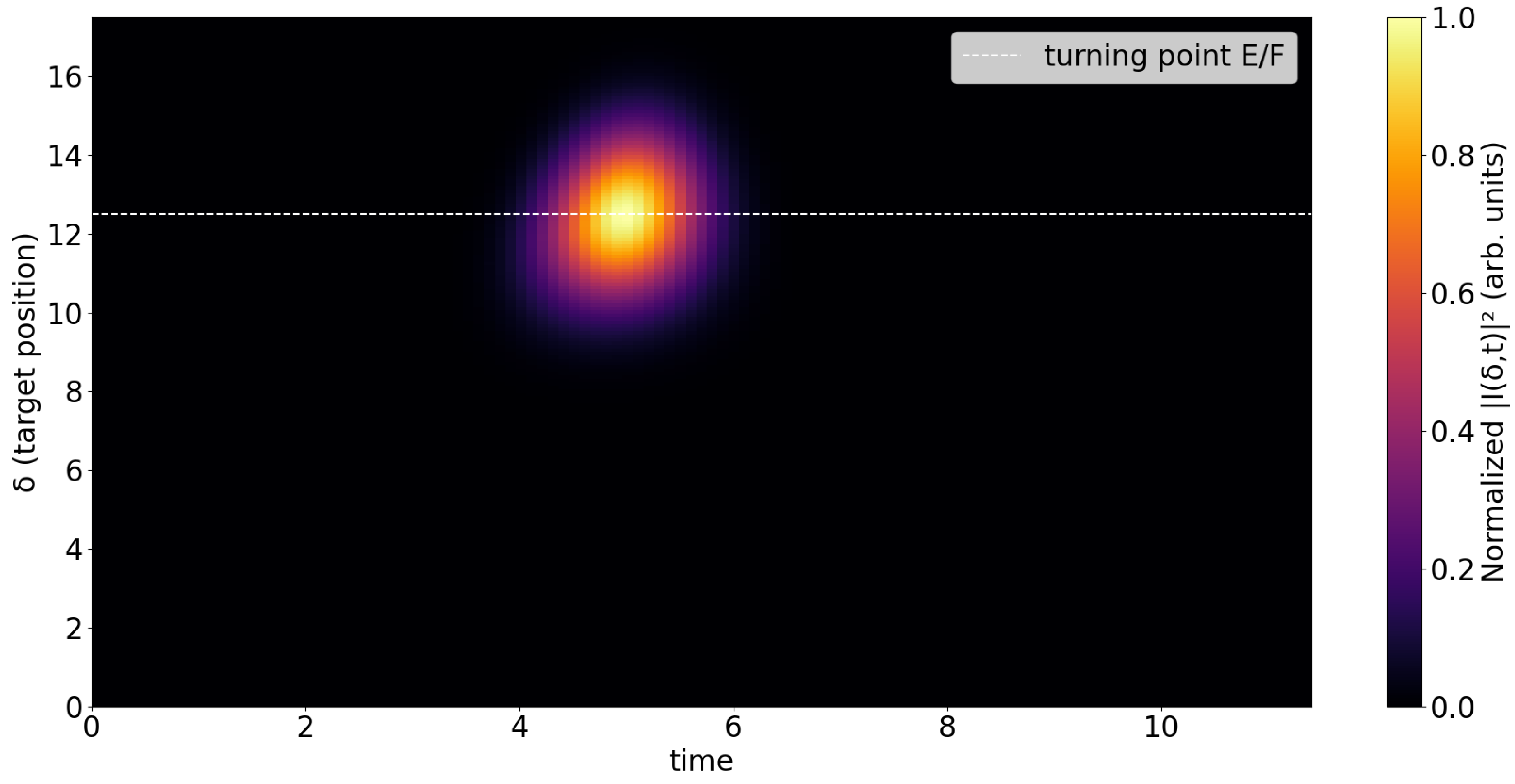

Fig. 5 shows the heatmap of

as a function of target position

and time t. Unlike the probability density, this quantity reflects nonlinear phase-sensitive interactions. The signal is localized around specific

and

t values, typically near the classical turning point, where the wavepacket overlaps maximally with the kernel and the cubic phase contributions interfere constructively. This figure highlights the regions where replication is most likely to occur, rather than the wavepacket’s full trajectory.

In both figures, the horizontal dashed line marks the expected turning point position . The probability density heatmap clearly tracks the propagation, while the replication intensity is concentrated near the turning region, consistent with the cubic dependence of on the local wavefunction amplitude.A systematic scan over the coupling and kernel width can be performed within the same framework and will be explored in future work. Preliminary checks show that the qualitative dynamics are robust to moderate variations of these parameters.