3.1. Entropy for Bell-States, Product States and Mixed States

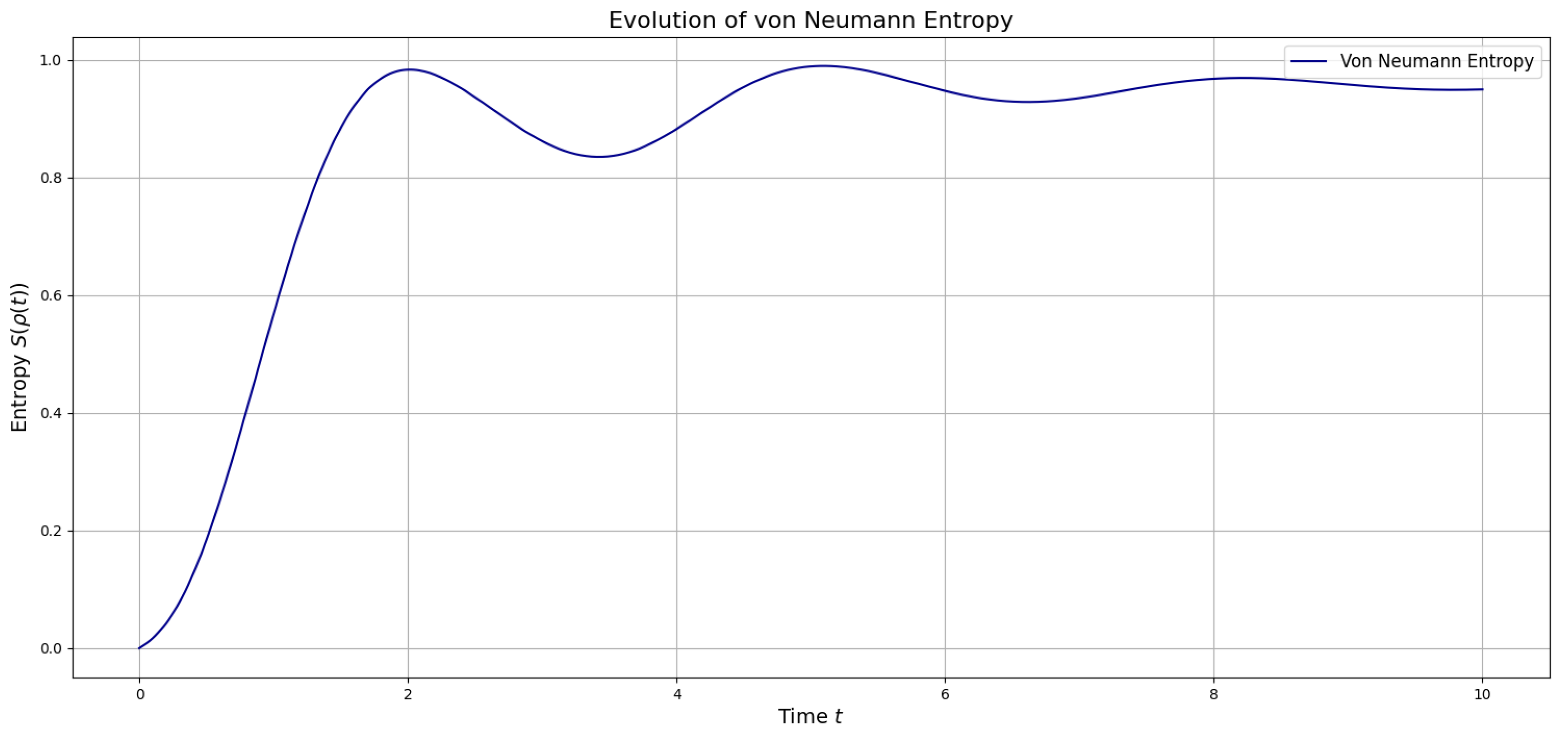

The numerical calculations allow us to calculate the most fundamental property of the system, defined by the von Neumann entropy

. The von Neumann entropy (also defined as quantum entropy) quantifies the uncertainty of a quantum state represented by the density operator

, defined as:

Following

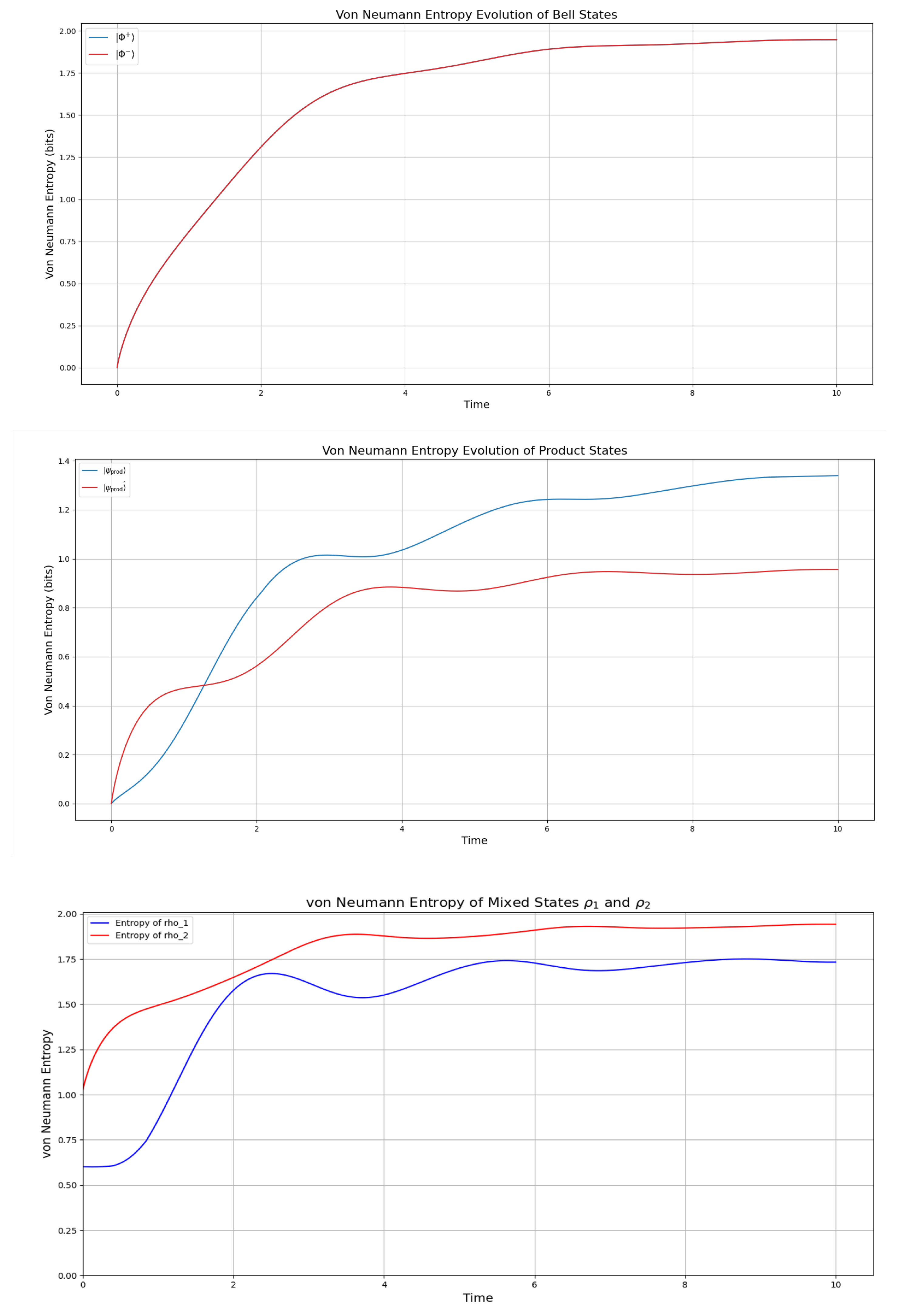

Figure 1, both Bell states

and

display initially an entropy of approximately zero, indicating that the system starts in a pure state. Over time, the entropy increases to about 1.85 bits, suggesting a process of mixing, likely due to decoherence. Notably, the identical evolution of these states implies that the dynamics are phase-insensitive, meaning that the system’s evolution does not depend on the specific phase relationship between the states. For the product states

and

, the initial entropy of the full system is also zero, but the reduced entropies are approximately 0.72 bits and 0.97 bits, respectively. As the system evolves, the entropy increases, reaching values of 1.3 bit and 0.8 bits. This growth in entropy suggests that entanglement is generated over time, transforming the initially separable states into partially entangled states. The differences in the entropy values indicate that the two product states undergo different degrees of entanglement formation, possibly due to variations in their initial superposition coefficients.

For the mixed states and , the initial reduced entropies are 1 bit and approximately 0.65 bits. The entropy of fluctuates between 0.75 and 1.75 bits before stabilizing at 1.6 bits, while reaches a peak of 1.9 bits and settling there. This suggests more complex dynamical behavior compared to the Bell and product states, possibly due to the probabilistic mixture of pure states in their initial configurations. The long-term stabilization of entropy values indicates that the system reaches a steady state, reflecting a balance between entanglement generation and dissipation effects. In overall, all simulations generate steady states with a maximal value of , it is however noteworthy that the interval represents a transition phase with decoherence and coherence which generate one-hump camel-like entropy behaviour, particularly of the product and mixed states. The Bell states display a lesser undulation in this interval, which however, is more pronounced in the entanglement entropy seen in next section.

Regarding the entropy plots (see

Figure 1), we observe a striking similarity to the spin-up electron fraction measured for a single phosphorus donor atom in silicon subjected to microwave radiation, as reported by Pla et al. [

23], however, with a considerable damping effect. Specifically, their results show Rabi oscillations of the spin-up fraction, which we find mirrored in the non-monotonic time evolution of the von Neumann entropy in our system for both product states (

,

) and mixed states (

,

). For the product states in

Figure 1, particularly

and

, we observe the entropy behavior as “camel-like” due to the characteristic rise, dip, and subsequent increase, resembling a double-humped structure in the entropy curves. Indeed, for the mixed states in

Figure 1, both

and

exhibit a rise-dip pattern, with

(blue curve) showing a more pronounced ‘camel-like” shape, 1.75 bits, while

(red curve) reaches a higher entropy of 1.85 (as the Bell states) bits with a subtler dip. This non-monotonic pattern in both cases can be attributed to coherent dynamics driven by noncommuting terms in the Hamiltonian which induce damped Rabi oscillations [

10,

22]. These oscillations cause the qubit’s state to evolve coherently, leading to a transient oscillatory profile in the entropy when traced over a subsystem; however, weak dissipation, as introduced by the dissipation term

, damps these oscillations after a single cycle, resulting in the observed “camel-like” shape before the entropy stabilizes at a steady value.

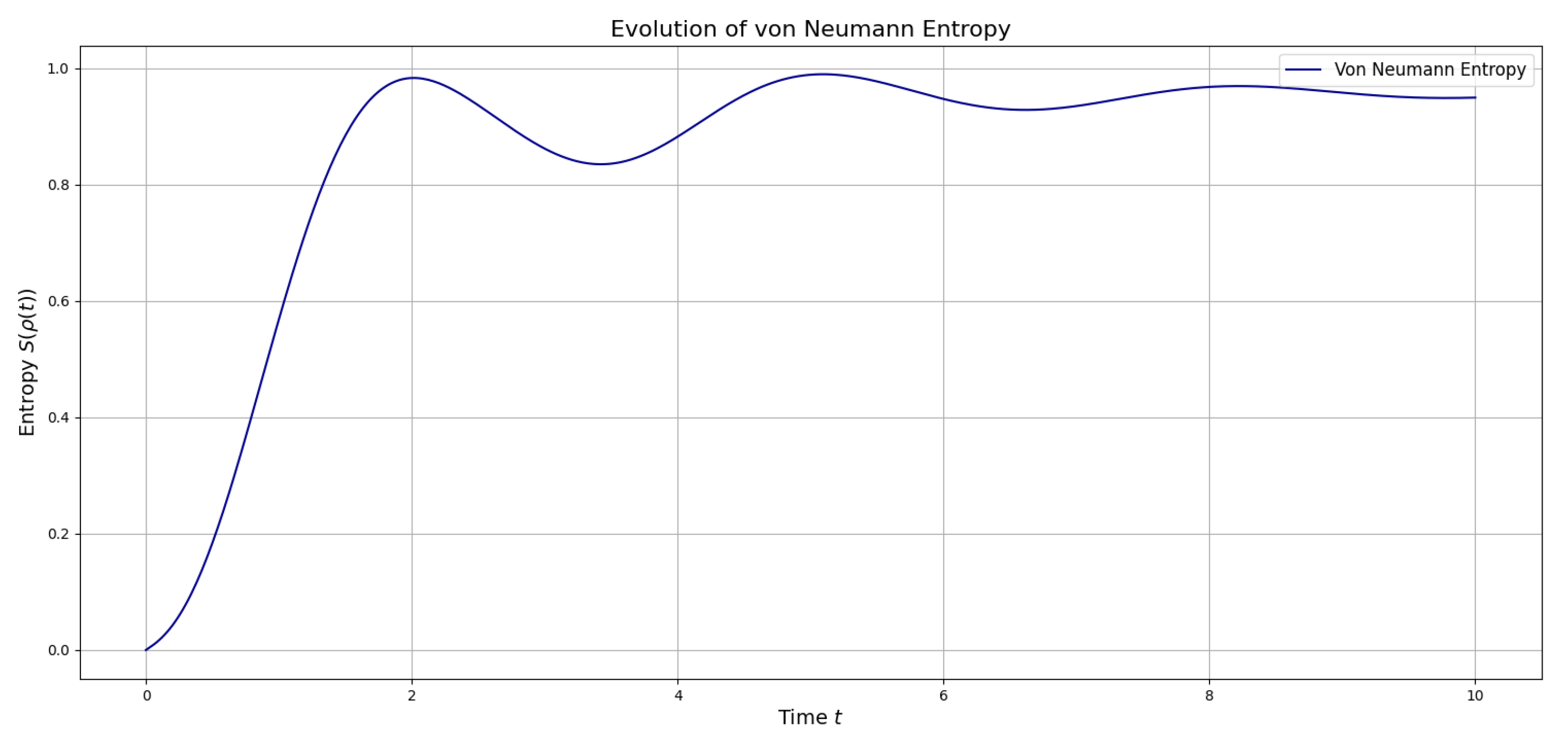

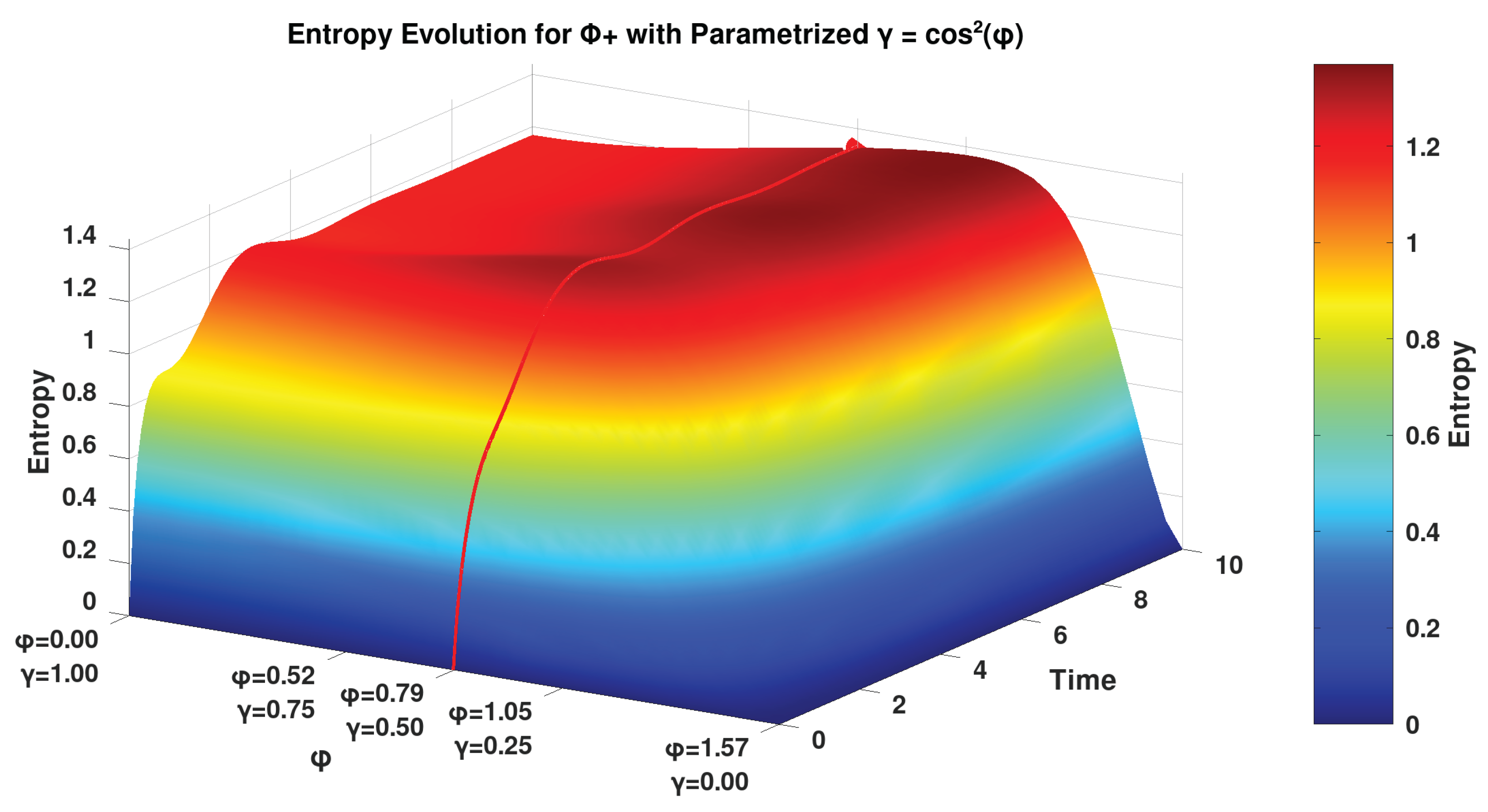

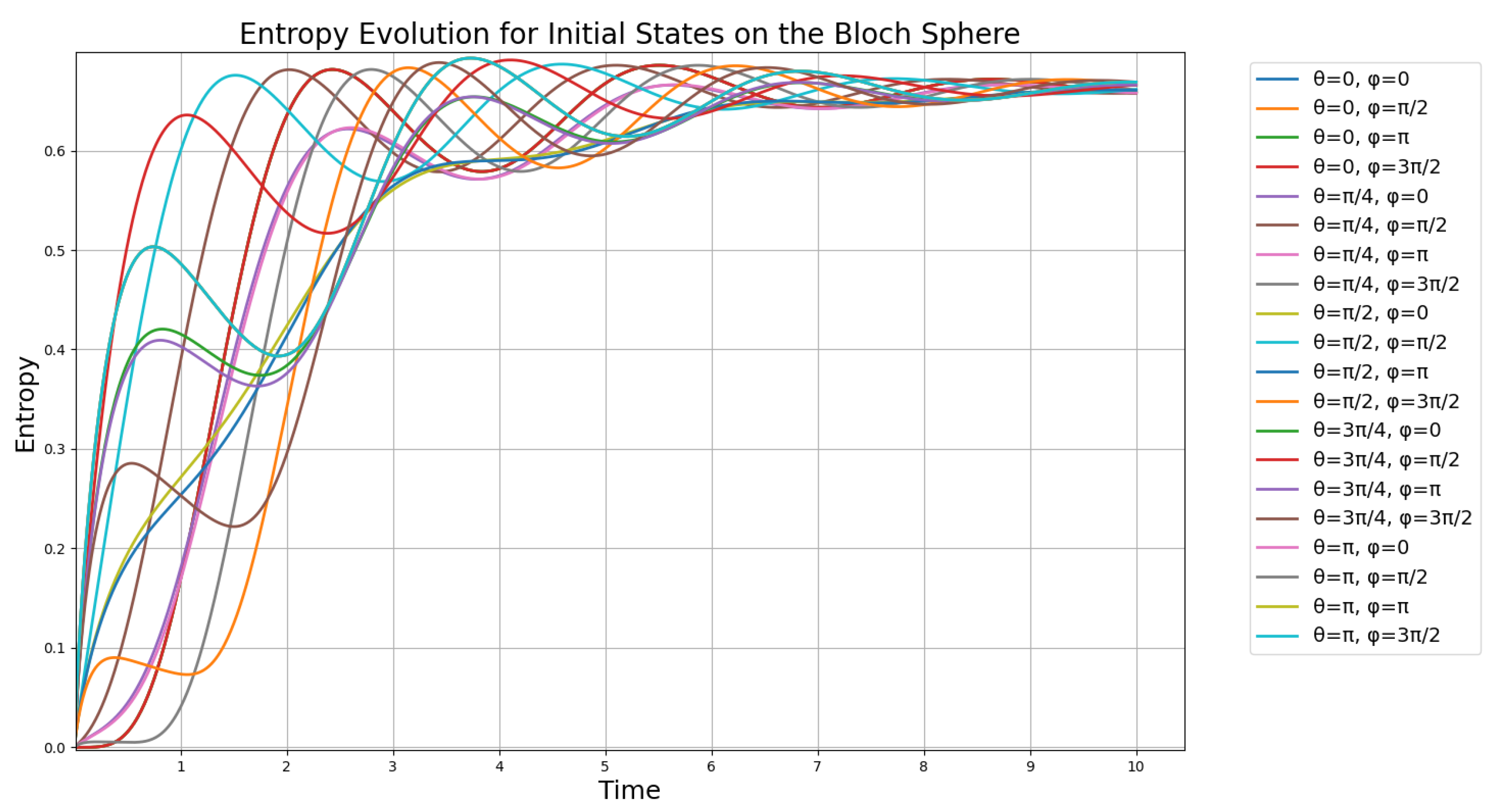

We add here an additional analysis of the evolution of the entropy for the Bell states using a parameterized coefficient of

. We parameterize

on the domain

. By this we obtain a map of the effect of the relaxation factor

on the unit interval, providing a smooth variation for the entropy evolution analysis, which is shown in

Figure 2.

We find an interesting result in the plot of the parameterized under the framework given in [

2] with relaxation factor

(

Figure 2), where the maximal number of undulations in the entropy (between 1 and 2 bits) occurs for

values approximately between

radians and

radians. The special behavior of the entropy observed in

Figure 2 is aligned with the damped Rabi oscillations detected for spin-fractions of single silicon atoms studied by Pla et al. [

23]. In this study, several different spin oscillations were observed after various input powers were applied to a single silicon atom device. The plots of these different spin-oscillations result as highly similar to the various plots represented in

Figure 2, indicating that the Khrennikov set-up of the GKSL equation may be suitable for the calculation of properties of such spin-fractions from single atom systems and entropy properties therein.

The Rabi-oscillations we observe in

Figure 2 signify intermittent entanglement degradation and revival, arising from the competition between the Hamiltonian’s coherent dynamics and the dissipative action of the

operator. Furthemore, the undulations in the entropy evolution for

under

are signatures of non-Markovian dynamics [

30], violating the Markovian monotonicity condition

where these oscillations lead to an increasing number of metastable entanglement revival via Liouvillian exceptional points [

31]. These points are degeneracies in quantum open systems (and classical systems as well) and have significant relevance to physics and optics [

31]. Such exceptional points define an entropy evolution where two or more eigenvalues coalesce [

32] and thus revoke that

-type Bell states could be optimally protected against external influence (i.e. decoherence channels) when

, making them promising for quantum devices to reduce noise and error.

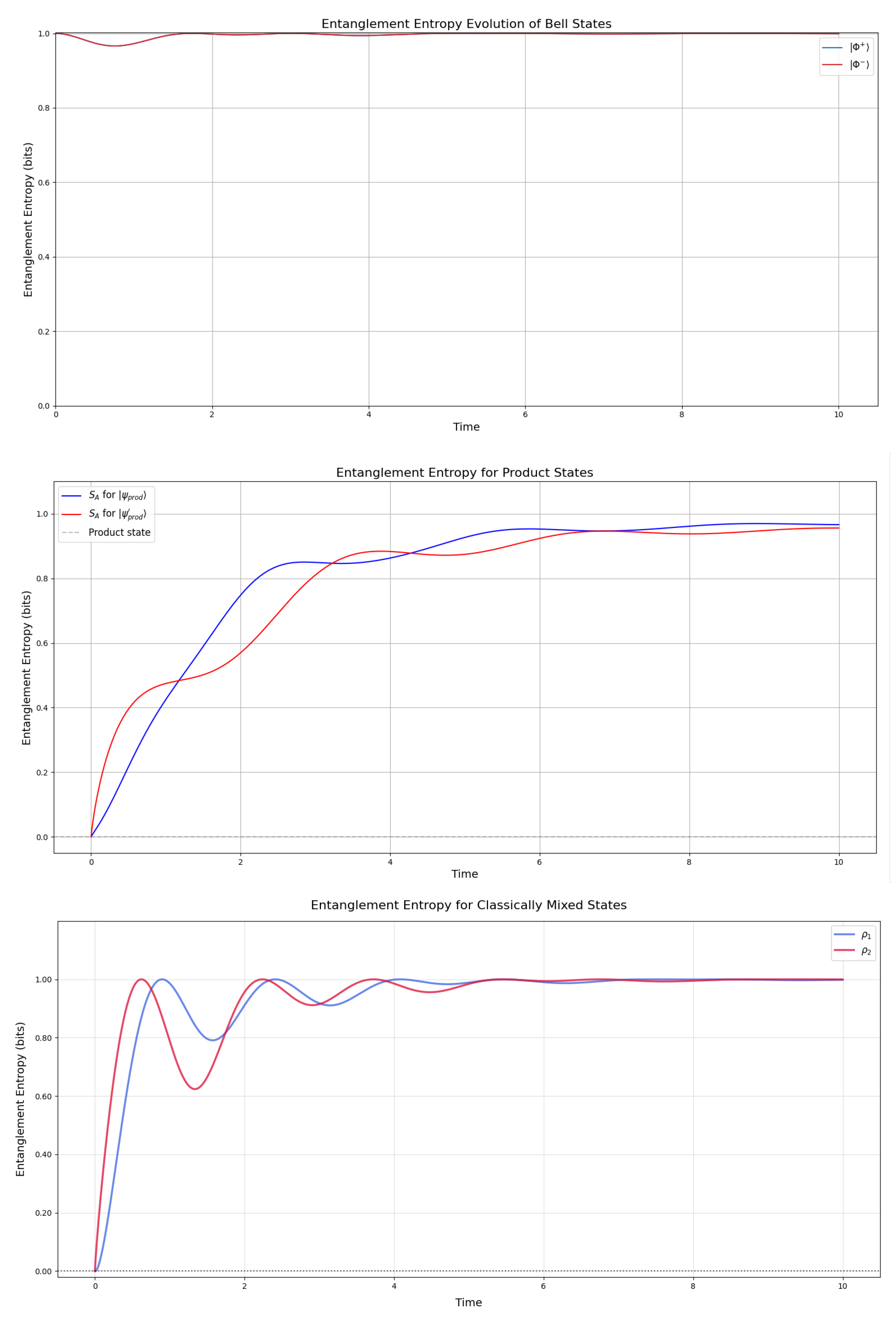

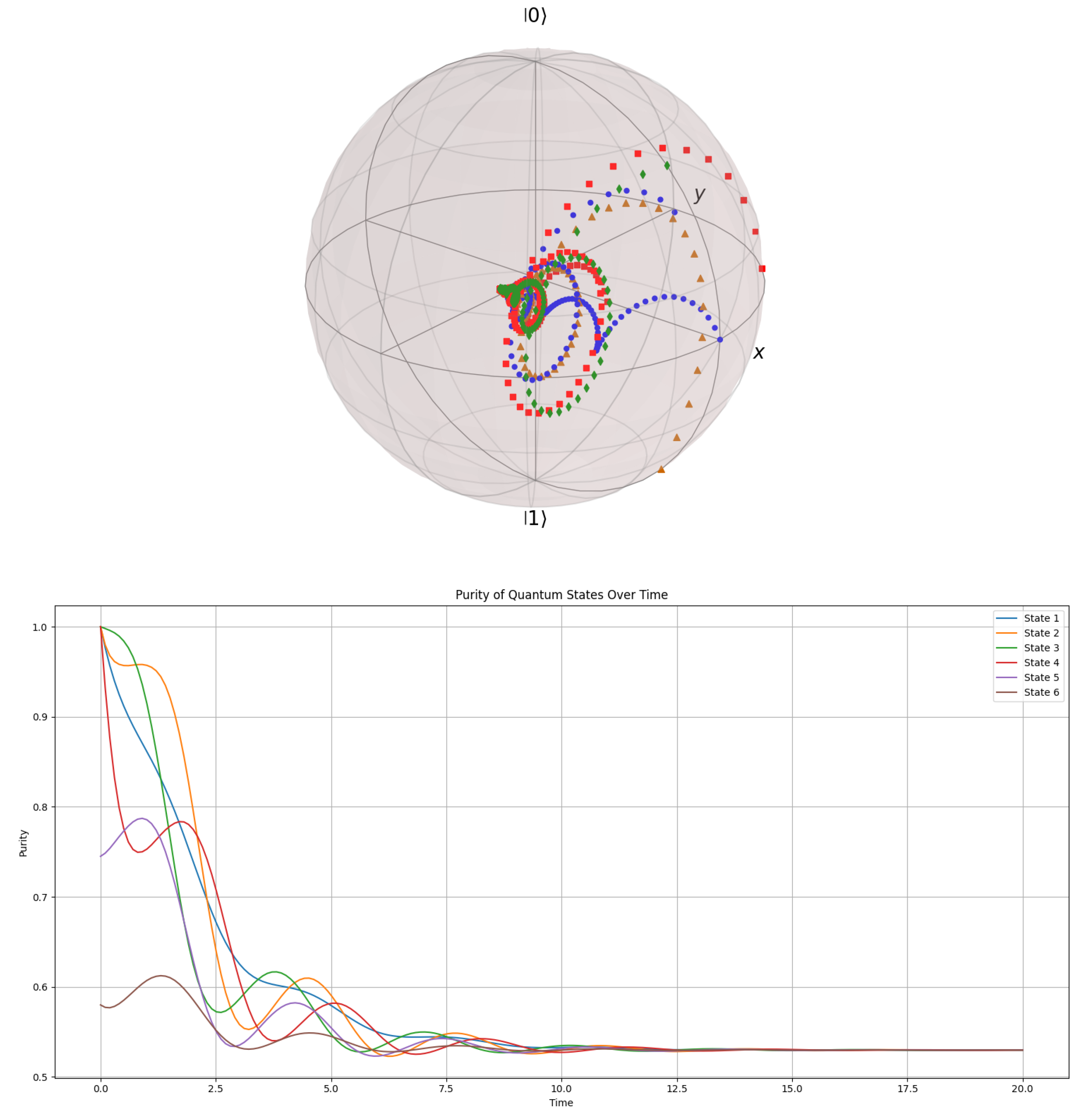

3.2. Entanglement Entropy

The entanglement entropy is defined by the von Neumann entropy of the reduced density matrix and is employed by being computed for one of the states, working as a key metric for understanding the coherence and mixedness of quantum states over time. Following the top plot in

Figure 3, we focus on the Bell states

and

, both initially maximally entangled with

(due to normalization, scaling to a maximum value of 1 for clarity). As time progresses, the entropy (represented by a single red curve, as both states evolve identically) dips slightly around

, reflecting the dissipative influence of the raising operator, which nudges the system toward the ground state

. However, the entropy stabilizes near 1, significantly above zero, indicating robust residual entanglement. This persistence suggests that the Hamiltonian

H, by facilitating transitions between

and

, effectively counteracts the disentangling effects of dissipation, preserving quantum correlations in the long-time limit.

For the product states

and

, the entanglement entropy dynamics reveal three distinct phases. Initially, both states show zero entanglement entropy (as expected for separable states), followed by a sharp increase to approximately 0.8-0.9 bits, indicating significant entanglement generation under the system’s dynamics. The subsequent plateau around 1 bits demonstrates stable entanglement preservation, with the states remaining highly (though not maximally) entangled. The close similarity between both curves suggests the dynamics affect different product states in qualitatively similar ways, while the slight difference in their steady-state values may reflect varying degrees of correlation in their initial configurations. The mixed states

and

(

Figure 3) exhibit more complex behavior, following a damped Rabi-oscillation mode, beginning with zero entanglement despite their mixed nature, which highlights their preparation using mixtures of product states. Both states rapidly develop entanglement, with both reaching maximal entanglement (1 bit) and also dipping like the Bell states in the interval

. This non-monotonic evolution suggests competing dynamics with initial entanglement generation through unitary evolution followed by partial disentanglement, due to decoherence or specific Hamiltonian terms. We pay particular attention to the interval

, which aligns with the definition of one-hump in 1 and study it further by the mutual information with regards to all states.

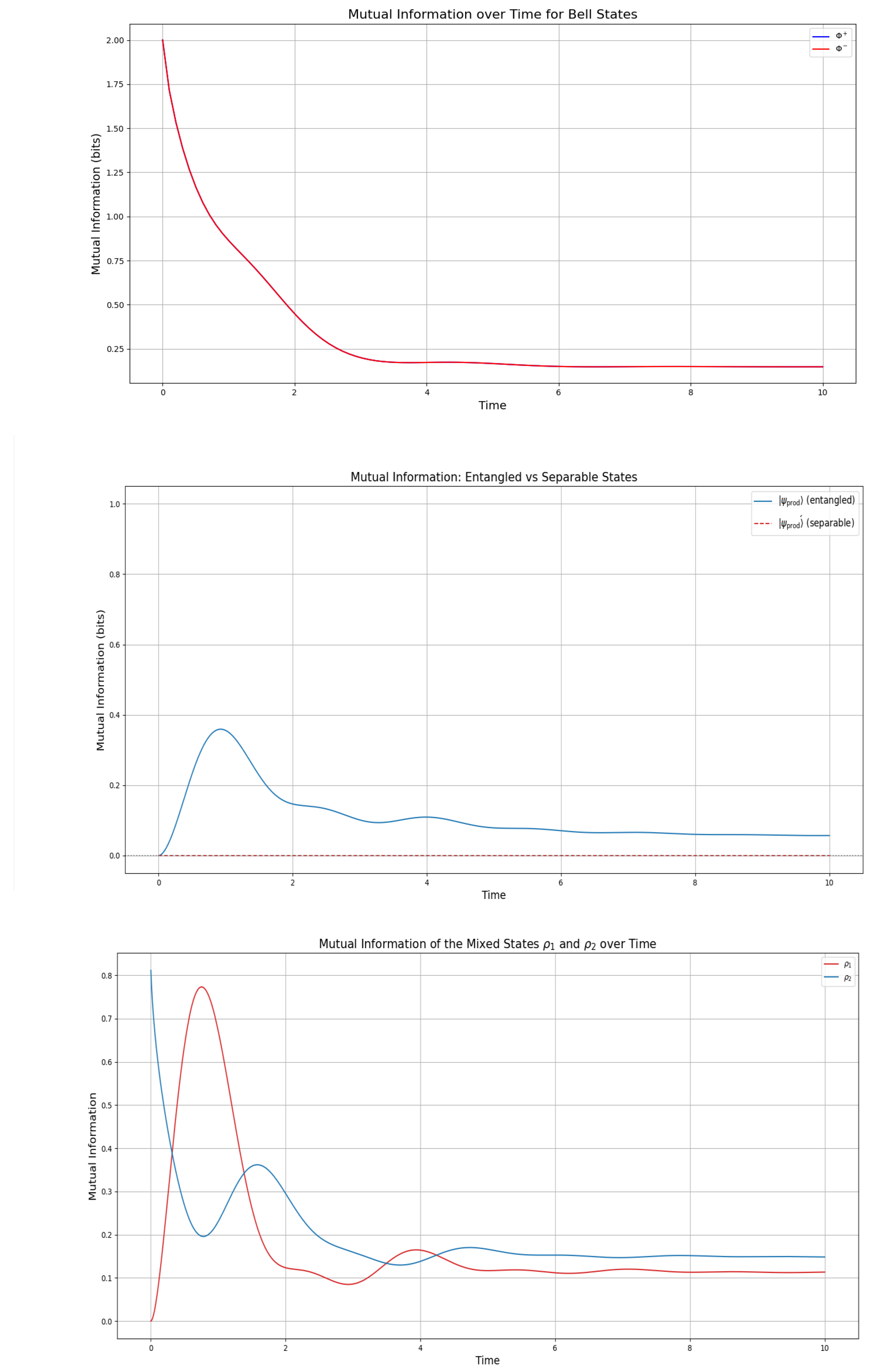

3.3. Mutual Information

We study the physical implications that the camel like framework [

2] has for the Bell-states, the product states and the mixed states with emphasis to definition 1. For this, we calculate the mutual information, which is a measure of the amount of information exchanged between the states during the Lindbladian evolution of the density matrices. In

Figure 4 we see in the top plot the mutual information evolution of the Bell states

(red) and

(blue). Initially, both state. Over time,

decreases monotonically to 0.15 bits by

, driven by decoherence from the Lindblad term with collapse operator

. Despite this, the entanglement entropy

bit (see

Figure 4) indicates persistent quantum entanglement, maintained by the Hamiltonian

. The dissipation drives the first qubit toward

, increasing

to 1.75 bits by

(data not shown due to graphical limitations), while the second qubit’s entropy decreases to

bits due to asymmetric dissipation. This yields

, though the plot shows a residual 0.1 bits, possibly due to incomplete decoherence. The decline in mutual information suggests that the GKSL framework induces classical-like information exchange, despite persistent quantum entanglement.

The middle plot in

Figure 4 compares product states where we have an initially entangled state

(blue) and a separable state

(red dashed). For

, the mutual information starts at 0 bits, peaks at 0.35 bits around

, and stabilizes at 0.08 bits, reflecting a decay of

bits. This behavior arises from the competition between entanglement generation by

and correlation loss to the environment at a rate

. In contrast,

remains at 0 bits, confirming the absence of quantum correlations throughout the evolution.

The bottom plot in

Figure 4 examines mixed states

(red) and

(blue). For

,

starts at 0 bits, peaks at 0.75 bits around

, and stabilizes at 0.1 bits. For

, it begins at 0.8 bits, dips to 0.2 bits, before increasing to 0.35 bits, and also stabilizes at 0.1 bits. Both mixed states exhibit a transition around

, with

showing a higher initial mutual information, suggesting stronger initial dependence between subsystems.

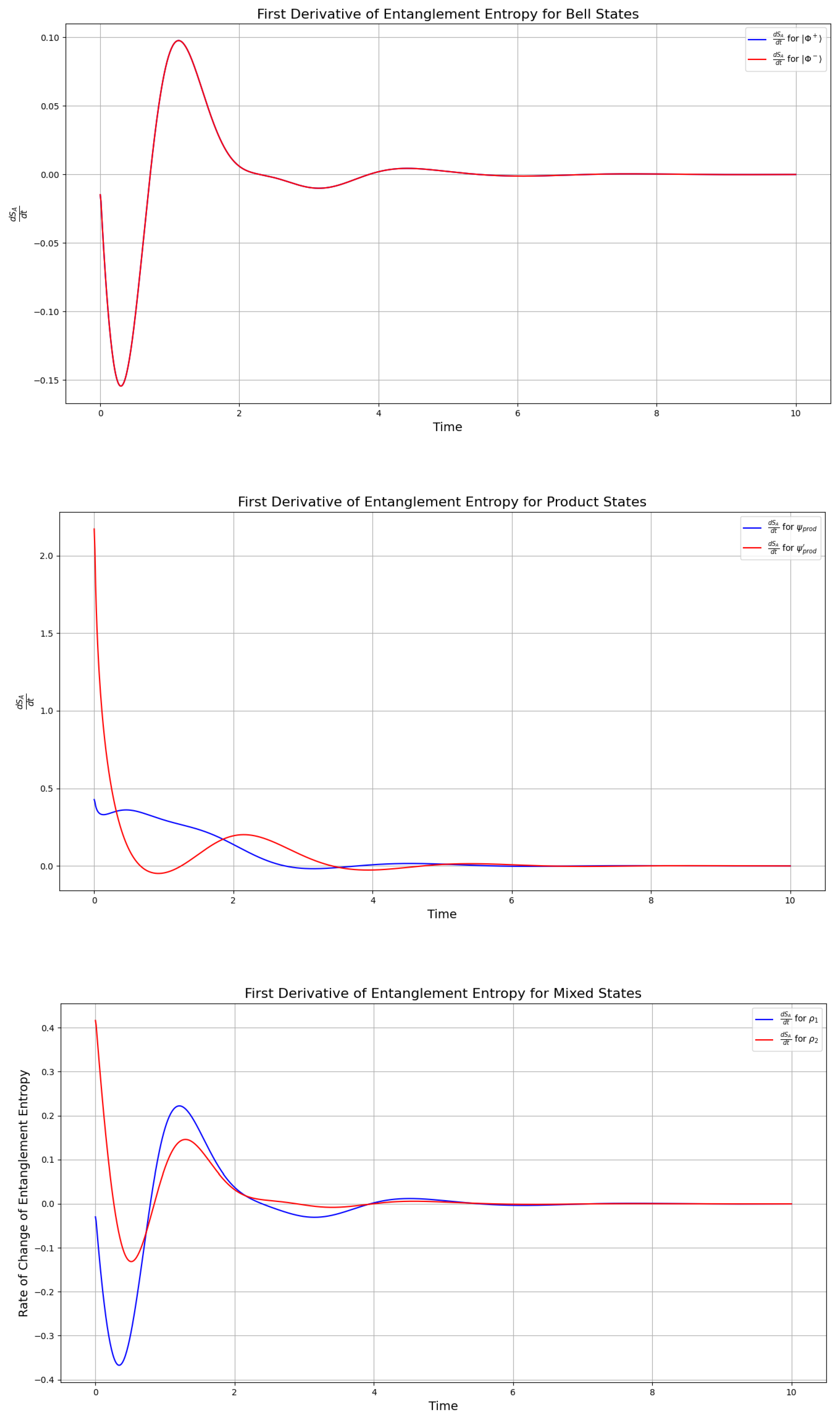

3.4. Rate of Information Exchange

The low steady-state mutual information across all states (0.1–0.25 bits) which we observed in

Figure 4 indicates that the Lindblad framework described in

Section 1.3 generally drives systems toward classical-like information exchange. However, comparing the transition period

in

Figure 4 with the entanglement entropy plots in

Figure 3, we identify a key transition state for

,

,

, and

, where the rate of change of entanglement entropy is maximized. This rate is given by

where

A represents the reduced state of

,

,

, or

. The maximal rate of information exchange is thus defined as

This period of maximal rate corresponds to the largest increase in entanglement entropy, contrasting with the overall decrease driven by dissipation. The plot of

is shown in

Figure 5 and highlights this transition, aligning with the mutual information peaks around

, which is a period contained in the one-hump interval defined in 1, and defined in definition 1. Thus, we observe that the transition state (

) from 1 corresponds to the maximum of the first derivative of the entanglement entropy for all states. This is particularly evident in the rate of change of the information exchange for the Bell states (

Figure 5), which exhibit only a minor “hump” in the entanglement entropy within the time interval

(see

Figure 3). This feature is reflected in

Figure 5 as an immediate maximum followed by a minimum in the rate of change of the entanglement entropy.

The maximum in the derivative highlights the period

as the interval of the most rapid rate of information exchange across all simulated systems. This observation suggests that the maximum of the rate of change of the entanglement entropy may serve as a key indicator for identifying whether the information exchange is transitioning toward classical or quantum-like behavior. Specifically, if the information exchange is developing towards classical, we expect the rate of change to decrease, while if it develops towards quantum-like, we anticipate a maximum in the rate of change of the entanglement entropy. This behavior is further contextualized by the mutual information, which decreases more slowly for the Bell states during this period, as shown in

Figure 5. A more pronounced effect is observed for the product states and mixed states in

Figure 5 (compare the y-axis values between the three plots), where the maxima in the rate of information exchange align with those in

Figure 4. Thus, calculating the rate of information exchange emerges as a critical method for predicting whether a system is transitioning from classical to quantum information exchange, or vice versa.

Notably, quantum correlations, such as those measured by quantum discord or CHSH parameters (discussed in the next sections), are often insufficient to determine whether a system is evolving toward classical or quantum information exchange. Instead, these correlations primarily indicate whether the system currently exhibits quantum-like or classical information exchange. In contrast, when the entanglement entropy can be resolved, its rate of change provides a robust prediction of the system’s evolution toward either quantum-like or classical information exchange.

In

Figure 5, we observe that the transition state (

) from definition 1 corresponds to the maximum of the first derivative of the entanglement entropy for all states. This is particularly evident in the Bell states, which exhibit a minor “hump” in the entanglement entropy within the time interval

(see

Figure 3). This feature is reflected in

Figure 5 as an immediate maximum followed by a minimum in the rate of change of the entanglement entropy. The maximum in the derivative highlights the period

as the interval of the most rapid rate of information exchange across all simulated systems. This observation suggests that the maximum of the rate of change of the entanglement entropy may serve as a key indicator for identifying whether the information exchange is transitioning toward classical or quantum-like behavior. Specifically, if the information exchange is classical, we expect the rate of change to decrease, whereas if it is quantum-like, we anticipate a maximum in the rate of change of the entanglement entropy. This behavior is further contextualized by mutual information, which decreases more slowly for the Bell states during this period, as shown in

Figure 4. A more pronounced effect is observed for the product states and mixed states in

Figure 4, where the maxima in the rate of information exchange align with those in

Figure 5. Thus, calculating the rate of information exchange emerges as a critical method to predict whether a system is transitioning from classical to quantum information exchange. Interestingly, these results are supported by recent studies [

33], which show that quantum-to-classical transitions are not derived from operator non-commutativity but from the dynamical properties of the systems in Hilbert space, as we consider here in our calculations.

Notably, quantum correlations, such as those measured by quantum discord or CHSH parameters (discussed in the next sections), are often insufficient to determine whether a system is evolving toward classical or quantum information exchange. Instead, these correlations primarily indicate whether the system currently exhibits quantum-like or classical information exchange. In contrast, when the entanglement entropy can be resolved, its rate of change provides a robust prediction of the system’s evolution toward either quantum-like or classical information exchange. The former is associated with phenomena such as superdense coding or quantum teleportation, while the latter corresponds to classical phenomena, such as electromagnetic effects on electrons or the Compton effect [

34].

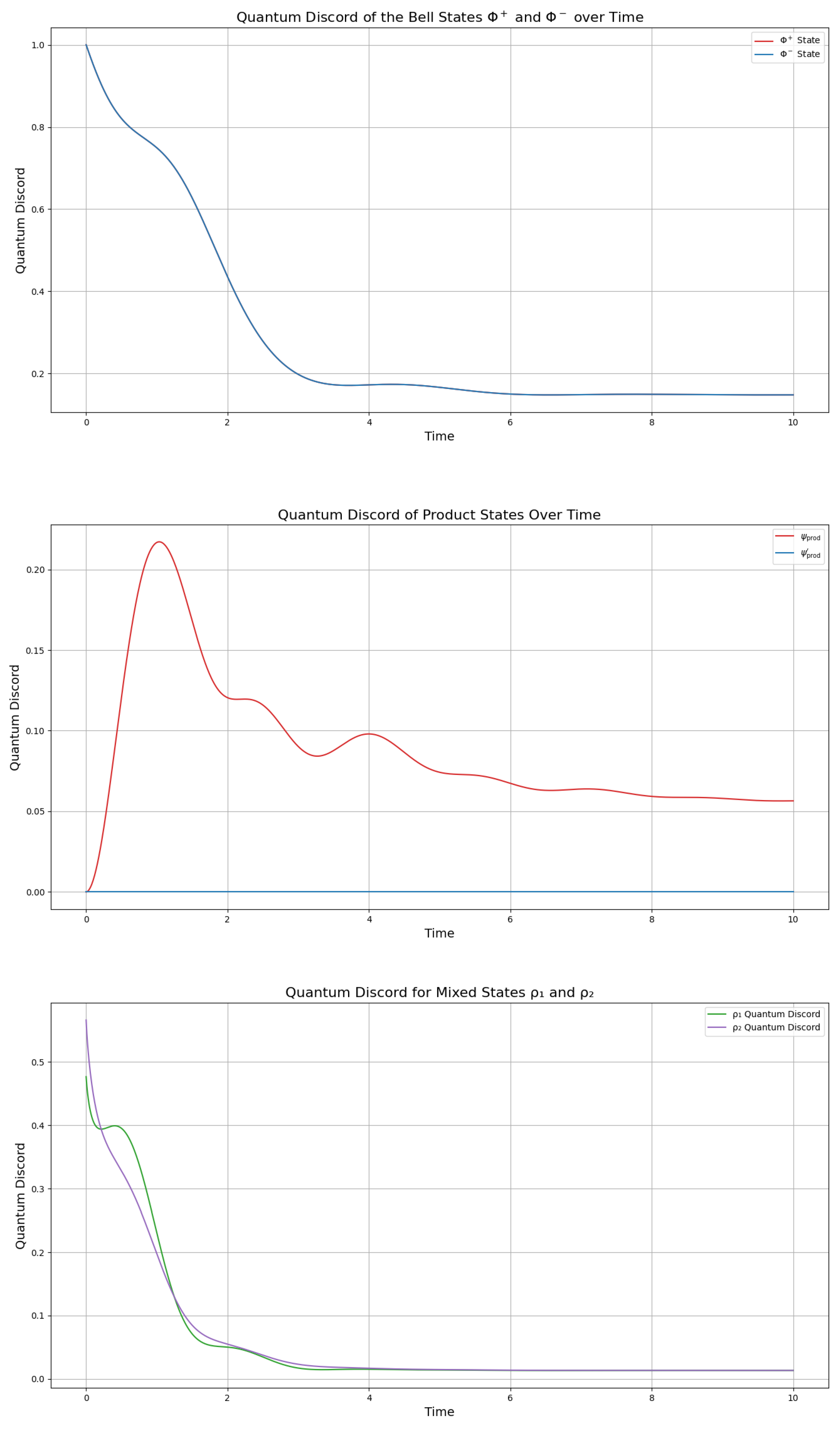

3.5. Quantum Discord

Quantum discord gives a measure on the level of “quantumness” of a system, hence to which degree the behaviour of the qubits is classical or quantistic. This is important to be determined, since the relationship between “quantumness” and quantum relations is not always as expected. For instance, a system can behave classically, but still be entangled, which indicates that quantum discord is an important property of systems, and can give better classifications of their behaviour in an open quantum system simulation. We calculate and plot the quantum discord of our model states, the Bell states, the product states in (

19), (

21) and the mixed states in (

23), (

24) by the Khrennikov-picture, using the Hamiltonians and dissipation operators given by (

16) (

Figure 6). In this figure, we see that we obtain a stabilization of the quantum discord of the Bell-states to a stable steady state after experiencing a small “hump” at the beginning of the simulation. This is in agreement with the evolution of the mutual information (

Figure 4). The fact that the Bell-states start from quantum discord of D=1 is correct as quantum discord measure non-classical correlations in mixed states, which Bell states initially are not. Clearly, the Bell-states lose coherence and their correlation turns into a classical correlation, to a higher extent, by attaining a steady state with a discord of D=0.1. It is noteworthy that the decrease in discord is showing a “hump” during the transition state period of

, as for the previous correlations and as defined by definition 1.

The quantum discord evolution in

Figure 6 reveals distinct dynamics for the entangled (

) and separable (

) states. The entangled state displays initial discord

bits, confirming non-classical correlations, which suddenly increases to

bits in the interval

and by

it stabilizes to 0.05 bits. In contrast, the separable state maintains

throughout, as expected for a classically correlated system. Notably, the non-zero steady-state discord for

implies persistent quantum correlations despite environmental interaction.

The mixed states,

and

behave similarly to the product states, however with a stronger synchronicity during the evolution. Their synchronous behaviour rests in their higher purity than the product states, however, their complete loss of quantum discord into the classical realm indicate that however pure, their combination generates classical relations for their substates (

Figure 6).

From

Figure 6 we see a further confirmation that the period

is the critical transition which delineates that the system is moving towards quantum-like information exchange by increasing the quantum discord for the product states and inducing a slower rate of negative change of the discord for the Bell state and the the mixed state

. Indeed, this is equally well-confirmed by the rate of change of the entanglement entropy of all the states, as an indicator of whether a system moves towards quantum-like information exchange or classical information exchange.

From

Figure 6 we see a further confirmation that the period

is the critical transition which delineates that the system is moving towards quantum-like information exchange (by increasing discord for the product states and experiencing a slower rate of negative change of the discord for the Bell state and the the mixed state

(

Figure 6). Indeed, this is equally well-confirmed by the rate of change of the entanglement entropy of all the states, as an indicator of whether a system moves towards quantum-like information exchange or classical information exchange.

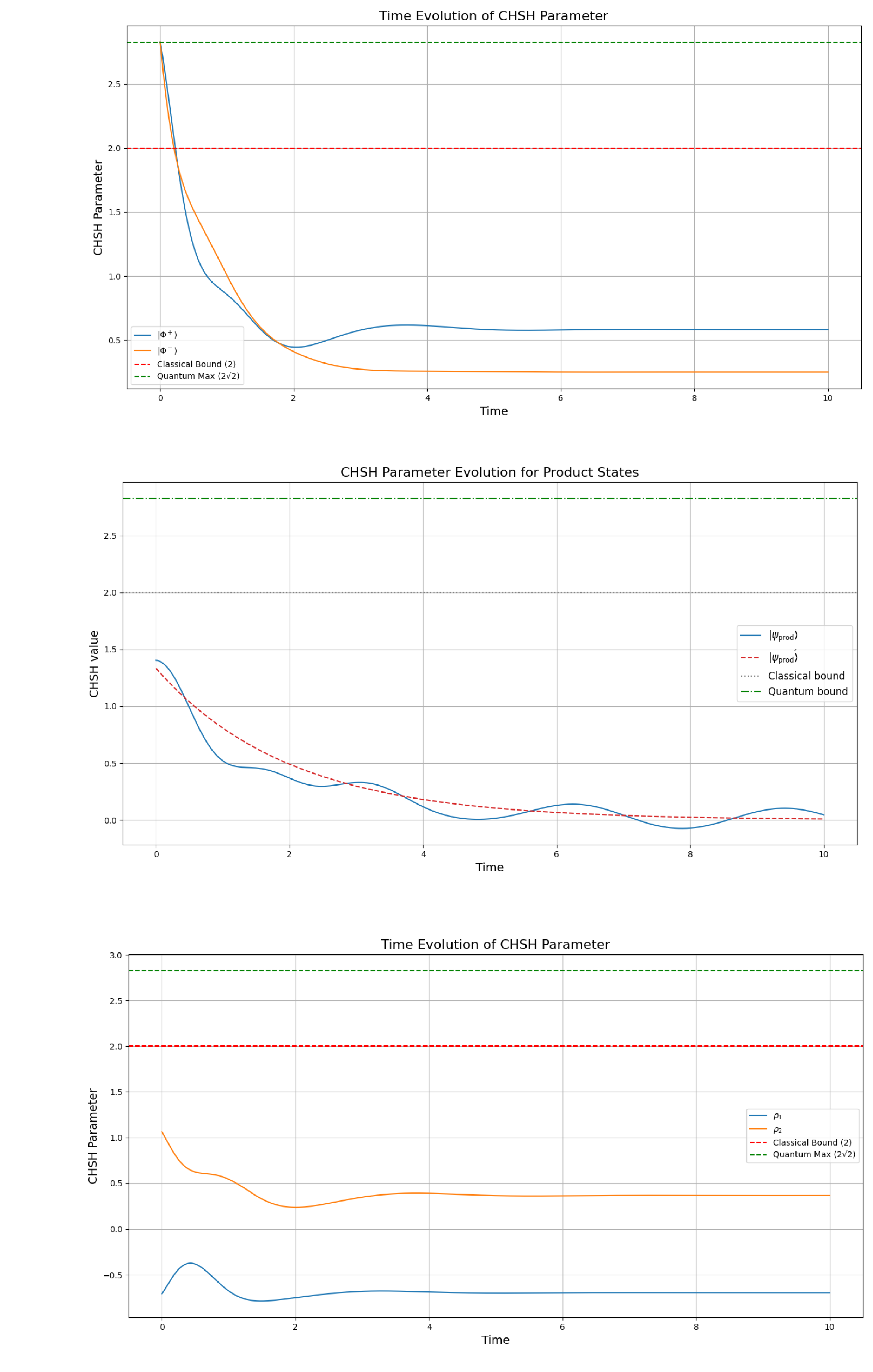

3.6. Bell-CHSH Parameter

For a proper quantum steering assessment, we evaluate the evolution of the CHSH parameter. Here we study the evolution of the parameter that allows for identifying the level of steering that occurs for the Bell states

,

, the product states in (

19) and the mixed states in (

23). We solve the Lindblad equation by the Runge-Kutta method of 4th order, under Lindblad dynamics governed by a Hamiltonian

and the collapse operator

and plot the evolution in

Figure 7.

The calculations show that the entangled Bell states

and

exhibit distinct behaviors in their CHSH parameter (

Figure 7). The CHSH parameter for both pure states starts at the quantum upper bound

which correctly reflects property of pure states by the CHSH parameter, which however decays rapidly within a few time steps, reflecting the loss of quantum coherence due to dissipation by the model dissipation operator and Hamiltonian. This describes that the presence of locally hidden variables, rapidly increases during the evolution of the GKSL equation with the given framework by [

2]. The critical transition state, referred to as the “camel-hump” in definition 1, demonstrates that surpassing the maximum leads to decoherence for the pure states

and

specifically within the interval

. This interval corresponds to the period

in

Figure 3, where the entanglement entropy rate,

, is significantly negative. Clearly, by the case of

in this interval leads to classical evolution and hence, as we see here for the CHSH parameter, a loss of coherence for pure states.

The evolution of the CHSH parameter under Lindblad dynamics for the product states

and

highlights the distinct behavior of these states under dissipation. For

, given by the initial CHSH parameter is

, indicating classical correlations with

. However, dissipation causes a rapid decrease in the CHSH parameter to approximately 0, reflecting a significant loss of coherence. This final value indicates that both product state retain weak correlations. When we consider the mixed states we find interesting results. For

, the mixed state defined as

with

which starts with a CHSH value of

, reflecting classical correlations between the subsystems under interaction with

. The CHSH parameter decreases to a minimum of 0.22 by time step 2, suggesting dissipation suppresses these correlations. It then increases and stabilizes at 0.4 in the steady state, indicating the state retains weak classical correlations, but the value remains below the quantum threshold of 2. For

, defined as

with

, the CHSH parameter starts at -0.5, which is unusual. This negative value suggests that classical correlations or interference between the components

and

dominate initially. Over time, the CHSH value increases to -0.34, then asymptotically settles at -0.6, indicating that

remains in a classical regime with no significant quantum steering potential in the steady state. The negative CHSH value for

suggests interference or classical correlations, rather than quantum coherence. As

is a mixture of

and

, the state lacks the necessary alignment for generating positive quantum correlations, leading to a negative value. Indeed, the CHSH components of

were calculated by the Python script as:

where

X and

Z are the respective Pauli matrices.

These values confirm that the simulation proceeded correctly. We can therefore affirm the negative values of , and add that the negative CHSH parameter indicates that the correlations in the state are anti-aligned with the measurement settings used in the CHSH inequality. This does not mean the state is unphysical or lacks entanglement; it simply means that the specific measurement settings used are not optimal for detecting the nonlocality of the state.

In overall, we can see that the Lindbladian evolution by the camel-like behaviour in [

2] gives no quantum steering between any steady states of the considered states, as their respective CHSH parameter fall below the classical threshold. A final word for the CHSH parameter is worth mentioning. The CHSH parameter cannot be used to predict whether the system evolves towards quantum-like or classical information exchange, as its evolution must violate the upper bound of 2 before the system has a direct quantum steering relationship between two states. The increase of a systems’ CHSH parameter over time does not warrant violation of the the upper classical bound, therefore, we cannot conclude whether the system is evolving towards a classical or quantum like information exchange by relying on the CHSH parameter. Such an evolution can only be predicted using the rate of the change of the entanglement entropy and assessed additionally by calculating the quantum discord. This is so, since the former highlights an evolution towards classicality (if

), and an evolution towards quantumness (if

), over a particular period of time

, where

J is the entire period of the evolution of the quantum system.

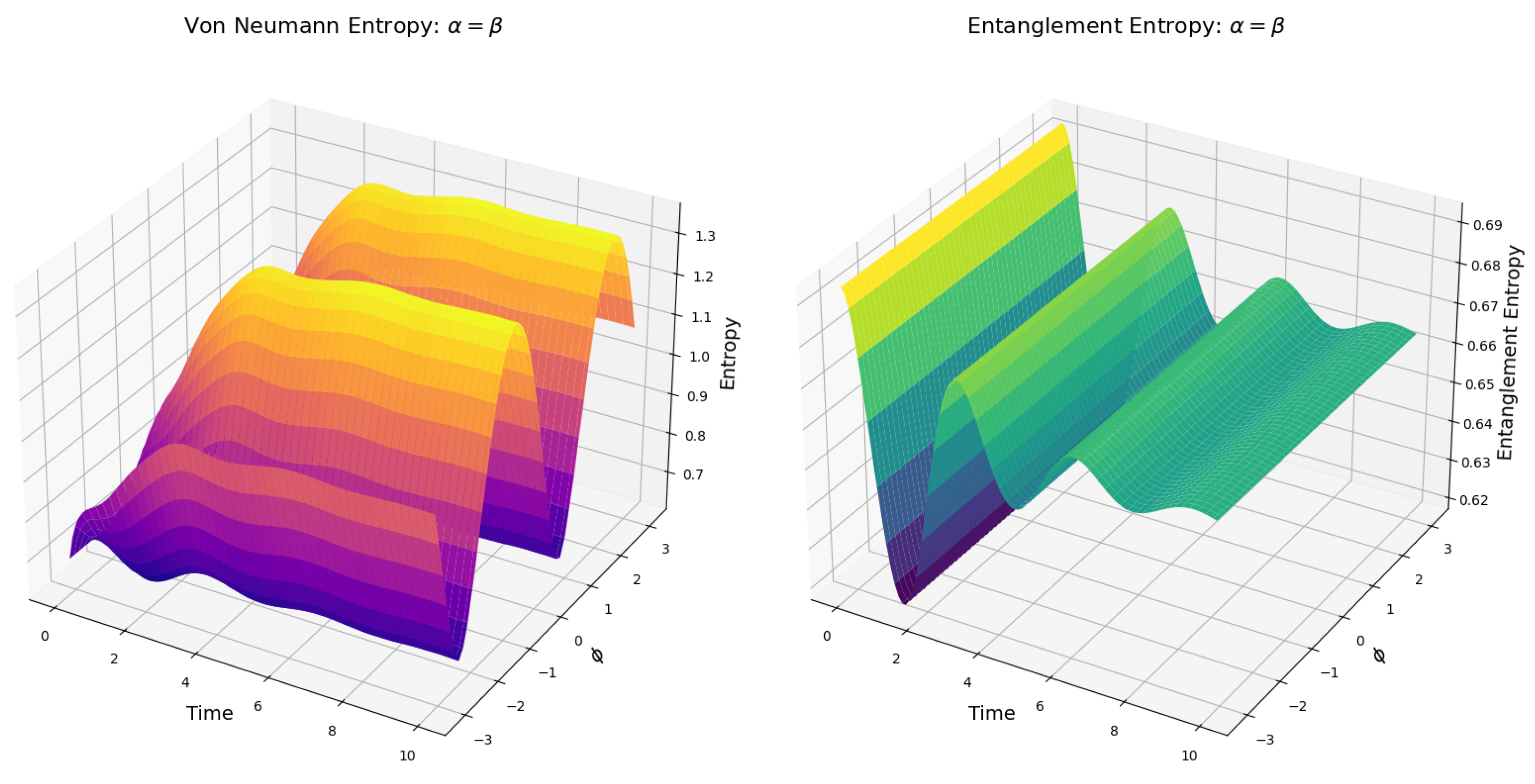

3.7. Entropy and Entanglement Entropy by Parametrized Coefficients of Mixed States

The goal of this final part of the analysis is to study the camel-hump-landscape defined by definition 1 for the entropy and entanglement entropy for mixed quantum states parameterized by

under Lindblad evolution. As shown in the method section, mixed states are constructed as convex combinations of pure states, where the coefficients

and

are defined by trigonometric functions of

(see Method section). The mixed state that is considered for this final calculation is defined as:

where the pure states

and

are given by:

So the convex combination of these two pure states forms the mixed state as:

These states evolve according to the Lindblad master equation, governed by the camel-like evolution Hamiltonian as given by [

2]. The von Neumann entropy,

, is calculated at each time step to quantify the uncertainty or mixedness of the state. By varying

, the dependence of steady-state entropy on the parameterization is analyzed, providing insight into how the structure of the coefficients influences the quantum system’s dynamics.

By

Figure 8 (left), we see that the entropy entropy dynamics observed in the simulations reveal a periodic behavior with a period of

determined by the trigonometric parametrization of the coefficients

and

using

and

. This periodicity, inherent to the symmetry of the parameterization, is reflected in the steady-state entropy values, which exhibit maxima at

and

, and minima at

and

, accordingly with the nature of

and

by the normalization condition

. These points correspond to configurations where the quantum system achieves the highest and lowest levels of mixedness, respectively (

Figure 8).

Figure 8 (left) shows that the periodic high-entropy states yield an increased uncertainty in the system, while the low-entropy states imply closer alignment to pure states (compare with

Figure 2). However, a key-insight is that the camel-like landscape gradually vanishes as the entropy grows by the periodic change of the value of

(

Figure 8, left). By considering definition 1, we see in

Figure 8 (left) that as the value of the coefficients evolves towards

and

as the transition state. This implies that the transition state is no longer a transition state followed by a relaxed steady-state, but a step towards a steady state of higher entropy than the transition state itself. By this we can conclude that the camel-like behaviour of the entropy given by [

2] given in

Figure 2 is sensitive to the parametrization of the coefficients of the quantum states.

Nevertheless, we find an equally interesting result in the evolution of the entanglement entropy (

Figure 8, left). The parametrization of the quantum state coefficients by

has no effect on the entropy of the reduced density matrices. This is expected, as entanglement entropy depends only on the structure of the total state and not on any direct interaction between

and

. As a result, the entanglement entropy for the mixed states follows the same transition-state-based landscape as when the coefficients are fixed (

Figure 3).

We can now construct the following theorem, relating the behaviour of the entropy in the entropy, entanglement entropy, mutual information, rate of entanglement entropy, the mutual information and the quantum discord in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 6,

Figure 8.

Theorem 1. (Classical versus non-classical evolution)

Let be the density matrix of a quantum system at time t, and let denote the entanglement entropy of a bipartite subsystem of the system, where and is the reduced density matrix of subsystem A. Let furthermore J be the entire period of the evolution of the states under a completely positive trace-preserving (CPTP) map, and let .

The system evolves under a completely positive trace-preserving (CPTP) map (i.e. the GKSL equation), which ensures the physicality of the evolution.

The entanglement entropy is differentiable with respect to time t.

If for all t in some interval I, the system’s information exchange evolves towards classical-like behavior in I. This implies a reduction in quantum correlations, such as entanglement, and a shift towards classical correlations, where the system behaves more classically.

If for all t in some interval I, the system’s information exchange evolves towards quantum-like behavior in I. This implies an increase in quantum correlations, such as entanglement, which enables non-classical phenomena like quantum teleportation.

The measured substate shifts the quantum discord toward 0 by adding classical contributions, while the unmeasured substate shifts it toward 1 if , and conversely if .

Proof. Since the system evolves under a CPTP map (completely positive trace-preserving map), the density matrix

evolves as

, where

is a CPTP map. This guarantees that

remains a valid density matrix. Furthermore, we base our proof on the universal relation:

The entanglement entropy

is defined as the von Neumann entropy of the reduced density matrix

:

By assumption, is differentiable, and we analyze the implications of and prove point 1. and 2.

Case 1: If for all t in some interval I, this implies that the entanglement entropy is decreasing over time. Since entanglement entropy measures quantum correlations, its decrease suggests that quantum information is being lost, likely due to decoherence. This results in a reduction of quantum correlations, leaving only classical correlations dominant, signifying classical-like behavior.

Case 2: If for all t in some interval I, then entanglement entropy is increasing. Since increasing entropy indicates an increase in quantum correlations, the system is evolving towards more non-classical correlations, including entanglement and quantum discord. This suggests that the system’s information exchange is dominated by quantum effects, signifying quantum-like behavior.

In order to prove point 3., we analyze explicitly the implications that the theorem has when we apply a measurement to either of the substates of the system, A or B, under the evolving CPTP-map.

We start with the definition of the quantum discord:

where

and (using an equivalent formulation)

Taking the time derivative (and assuming that the optimal measurement varies smoothly so that the derivative passes through the maximization) yields

We now consider two cases,

Variation in : In the definitions above, appears in both and and cancels exactly. Thus, variations in do not contribute to .

Variation in : In Eq. (

40), if we assume that the contributions from

and

are constant or negligible, then

Consequently,

If , then .

If , then .

Therefore, when performing a measurement on a bipartite system, the sign of directly contributes to the sign of the change of the quantum discord. We can interchange the roles of the substates A and B, such that A does not vanish but B does instead in the initial equation of the quantum discord. This would change the substate that is subjected to a measurement. Hence, the substate that is measured contributes to the change of the sign of the quantum discord towards 0 (by addition classical contributions to the system), while the substate that is not measured contributes to the change of the sign of the quantum discord towards 1, if , and conversely if . Hence, we have completed the proof which holds for a bipartite system in the absence and presence of a measurement.

□

Remarks:

The theorem assumes that entanglement entropy is a valid measure of quantum entanglement, which holds for pure and product states, by considering the results from this study. The theorem holds also for mixed states since the parametrization by of the coefficients of the subsystems does not affect the entanglement entropy landscape.

The theorem applies to bipartite systems. For multipartite systems, the behavior of entanglement entropy can be more complex, and additional considerations may be necessary.

The theorem assumes differentiable entanglement entropy, which may not hold in all cases (e.g., during quantum phase transitions or in open quantum systems with non-Markovian dynamics or under discrete Markovian quantum dynamics).

3.8. Analytical Approach to the GKSL Equation

As we have now introduced a set of methods for solving the GKSL equation analytically, and provided an example, we shall enter into the calculations for solving the GKSL equation under a specific framework, namely the Khrennikov framework. Analytical solutions of this open quantum system are important as these functions can provide crucial insights into how entropy scales in different dissipation regimes and as we obtain closed-form expressions for the entropy as a function of time, they enable us to study the entropy growth or decay [

17]. The solutions can thus reveal how the entropy behaves near or at equilibrium, particularly identifying the steady-state entropy and revealing its dependence on the system’s constraints [

35]. We can also derive the exact description of how entropy scales with time, by using the derived analytical solutions which can evolve according to exponential decay or power-law growth, depending on the nature of the dissipation [

30]. Furthermore, the analytical solutions can aid to facilitate the study of quantum-to-classical information exchange transitions, and one can identify how this can be caused by change in decoherence or quantum coherence affecting the system’s entropy [

36]. Indeed, the dissipation operators govern this role on the transition from classical-to-quantum or vice versa, and hence, the analytical solutions will prove valuable in concert with the structure of the dissipation operators to reveal this mechanism. This is essential in understanding the role of quantum effects, where entropy might increase at a different rate compared to classical systems, and has also with strong relevance to theorem 1.

3.8.1. Formulation of the Problem

We consider the evolution of a two-level quantum system (qubit) under the Gorini-Kossakowski-Sudarshan-Lindblad (GKSL) equation:

where:

is the density matrix of the system,

H is the Hamiltonian governing unitary evolution,

C is the Lindblad operator representing system-environment interaction, and

is a coupling constant controlling the strength of dissipation, which we calculated to

in the Spectral analysis section.

Following [

2], we apply:

in the spirit of the transition-entropy regime by Khrennikov [

2,

7,

12,

13,

15,

21], which we studied numerically in the first part of this thesis.

Structure of the Density Matrix

We assume a general initial density matrix of the form:

where all diagonal entries are real functions, while off-diagonal entries are complex conjugates of one another.

3.8.2. Derivation of the Evolution Equations

Substituting (

42) in (

41) we solve for each component:

Then we get the anti-commutator term:

combining all terms and we get:

3.8.3. Basis States and Initial Conditions

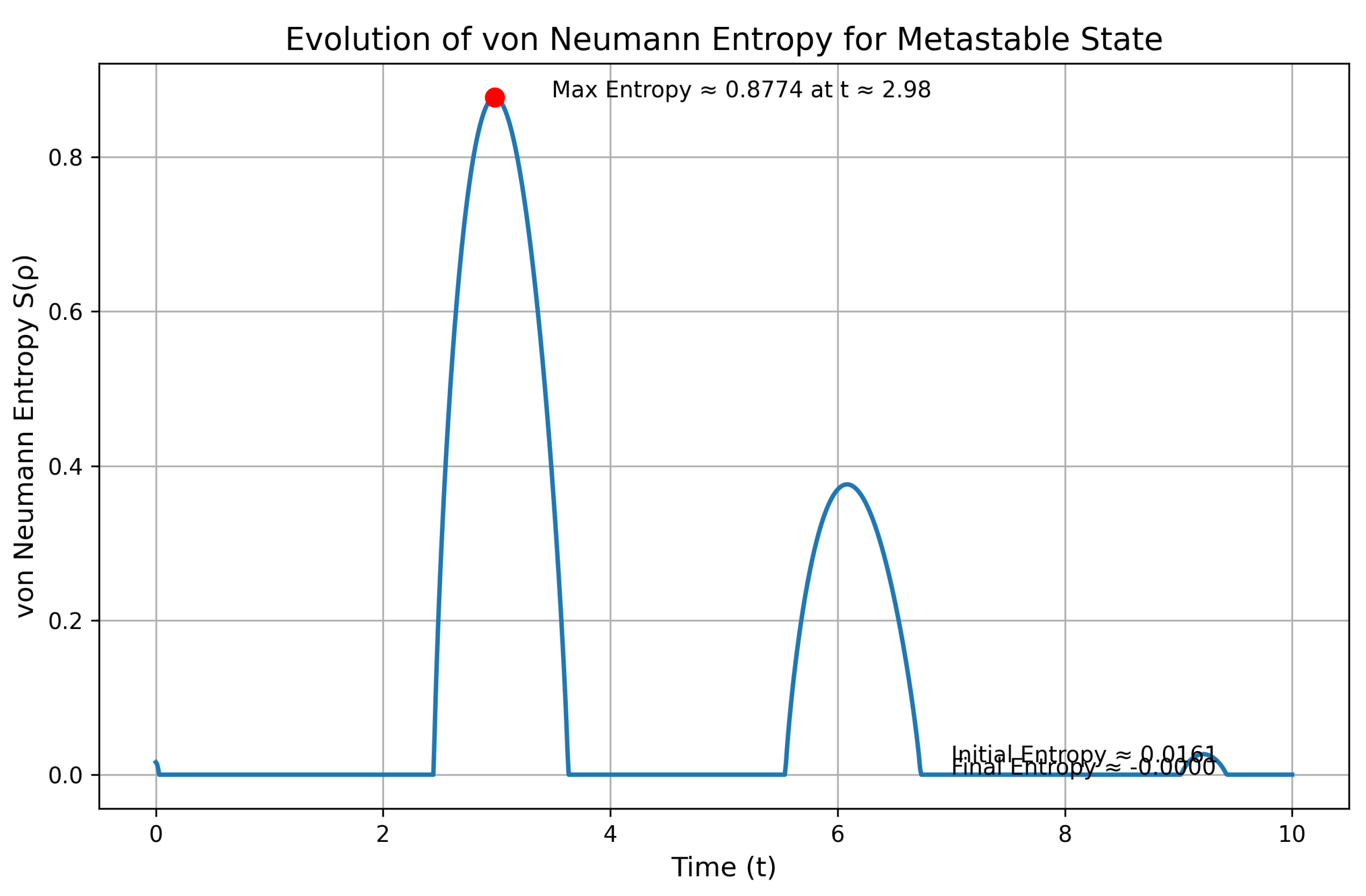

We now investigate the determination of optimal initial conditions for the analytical solution of the GKSL equation for . Guided by Definition 1, we seek initial conditions yielding 3-, 4-, or N-hump solutions in the entropy plots. Considering Definition 1, we first perform numerical calculations for a parametrized superposition of pure states, using one and then two parameters (corresponding to a single point and a curve on the Bloch sphere, respectively). These numerical results are then used to identify which parametrized states best reflect Definition 1 and to determine the relevant intervals for constructing appropriate models of N-hump camel-like entropy. Essentially, camel-like entropy represents a damped Rabi oscillation due to decoherence, eventually reaching a steady state. Based on this, we begin by identifying the initial conditions for the single-parameter states.

3.8.4. Initial Conditions from Parametrization on the Bloch Sphere

We now parametrize the pure states using two parameters, representing a curve on the Bloch sphere. To achieve this, we parametrize into the representation of the pure state superposition on the Bloch sphere.

which has the corresponding density matrix:

explicitly this gives the initial density matrix for the numerical calculation by:

We proceed to calculate numerical solutions of the GKSL equation (

41) with

and the operators defined in (

16). Using the Bloch sphere density matrix from (

52) we vary

and

and identify the suitable initial conditions by the resulting spectrum of numerical entropy solutions is shown in

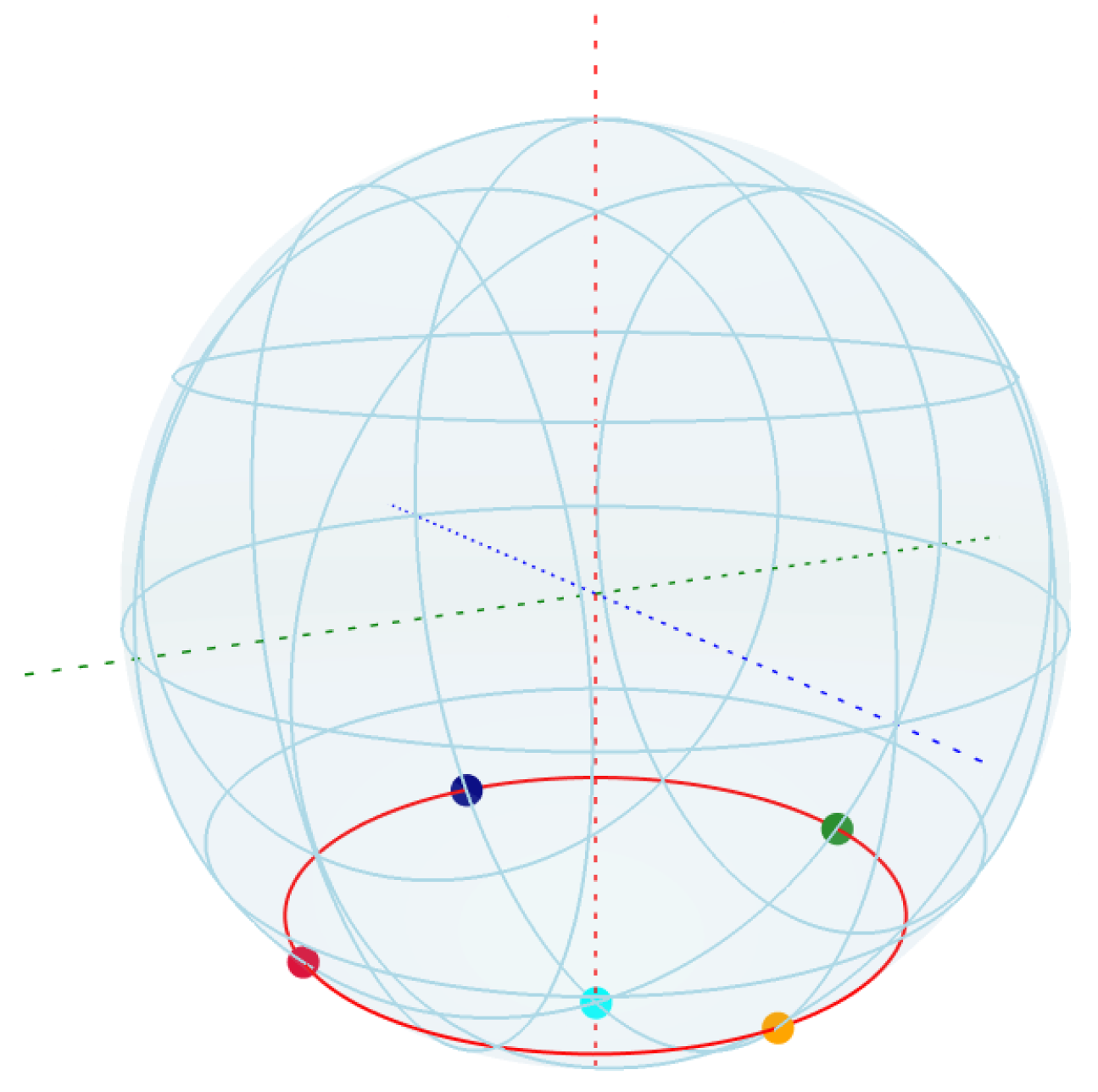

Figure 9 as overlaid plots.

From

Figure 9, we can see that six unstable states immediately decohere forming an important class of quantum states with importance for quantum coding purposes. We identify these on the left-most part of the plot and find that these states on the Bloch sphere form the set:

which gives the specific states:

which are states that are highly unstable towards decoherence and dephasing. We have a total of six of such states, where the last two in (

54) overlap on the South Pole. In order to find how these states appear on the Bloch sphere, we plot the Bloch sphere with these six states arranged as spherical coordinates (

Figure 10).

From the plot in

Figure 10, we find that the unstable states arise around the South pole of the Bloch sphere, in the well-defined third quarter-circle for

, at each quadrant intersection for the value of

. Notably, the four states on this quarter circle correspond to equal superpositions with distinct relative phases, aligned with the principal axes of the Bloch sphere. These geometrically significant points delineate a partition of the Bloch sphere where entropic instability becomes prominent, particularly through the emergence of rapid decoherence with no oscillatory components, which then decays oscillatory towards the steady state (see

Figure 9).

3.8.5. Behaviour of Decoherence-Sensitive States on the Bloch Sphere

The specific distribution of points in

in (

53) consists of four points at the three-quarter circle (

) and two that overlap completely at the South pole (

), and this set forms a

-symmetry around the

z-axis when viewed purely geometrically (

Figure 10). These points represent distinct quantum states:

(the second point at the South pole in (

53) is omitted for simplicity) at the South pole, and four states on the third quarter circle with amplitudes shown in (

54). The four states around the third quarter circle have the same superposition amplitudes but differ in their relative phases, aligned with the principal axes in the

x-

y plane of the Bloch sphere. The behaviour for each point is evaluated for the GKSL operators under the camel-like framework which we analyse one by one:

For the states on the three-quarter circle at

, we have superposition states with amplitudes

and

:

Notably, these states are characterized by the special property that produces a state proportional to with amplitude , while yields the component of the original state. This creates a specific balance between the unitary and dissipative dynamics that leads to maximal decoherence rates.

The states at

follow the same pattern but with different relative phases:

In each case, the action of the collapse operator C produces the same output , while preserves the relative phase. The specific angle appears to maximize the interplay between coherent evolution under H and decoherence under C, creating instability points where the quantum state cannot maintain coherence.

For the South pole state:

This state experiences maximal dissipation with , while the collapse operator C annihilates it. The dissipative term dominates completely, making this a strong decoherence point where the state is “trapped” by the dissipation, unable to evolve coherently under the combined dynamics.

A common feature of all five unstable states (or six, if including the final state in (

54), which we omit here for simplicity) is that they represent critical configurations where the delicate balance between unitary evolution and dissipation gives rise to either maximal decoherence rates or degenerate dynamics. These properties render them unsuitable as stable quantum states under this particular dissipative channel. A similar scenario arises in the spectral analysis of the governing operator, where the parameter

modulates the system’s oscillatory and exponential components. However, in the current context, the imbalance between unitary evolution and decoherence is especially pronounced for the rapidly decohering states in the set

.

This issue motivates a deeper investigation, specifically, an analysis of the evolution of quantum states on the Bloch sphere. We aim to study the transition from the unstable states in to the remaining states on the sphere. This evolution can be rigorously analyzed by constructing a Lyapunov function, derived from an analytic function whose zero set corresponds to the unstable quantum states on the Bloch sphere, with all other points lying in its complement. In the following section, we derive this analytic function, which characterizes the relevant sets of quantum states on the Bloch sphere.

3.9. Topological Analysis on the Bloch Sphere

The set

in (

53) can be classified topologically on the Bloch sphere

. We establish coordinates on this manifold using the standard spherical parameterization:

This allows us to combine topologically all stable solutions (which decohere slowly under the camel-like framework) as the complement

, forming a non-compact topological space homeomorphic to a 2-sphere with 5 punctures, where each puncture corresponds to one of the highly unstable states in

in (

53) (recall two of the six states are the same on the Bloch spheres’ South pole). The set

of unstable states in (

53) can be interpreted as the zero-set of a map

where

f vanishes precisely at these six specific points. We can express this map as:

where

captures the pole structure (with zeros at

), and

represents the angular dependence (with zeros at specific

values depending on

). Here we can form the function:

This function vanishes precisely at the eight points of set

in (

53). The component

captures the latitude dependence, vanishing at

, while

encodes the longitude constraints, vanishing at the south pole and at four specific longitudes

when

. The factor

in

ensures it vanishes at the south pole regardless of

. The reason we construct this function which vanishes for the unstable points selected from

Figure 9 is based on forming a topological analysis of where the stable states arise, which are states that satisfy a gradual decoherence and dephasing under the camel-like framework. These decoherence- instable states in the set (

53) are indeed still valid as solutions to the GKSL equation, however, as they decohere immediately, they form a special case of states that pose specific consequences for quantum computation purposes,a s we briefly mentioned above. Therefore, isolating these states on the sphere can give us a topologically intuitive view of how states develop stability and instability to decoherence effects by the dissipation operator in the GKSL equation.

Thus, the function (

70) characterizes the set

of the unstable states as the zero set where

, while (more) stable states correspond to points where

. We can use this framework on the Bloch sphere to start by performing a gradient flow analysis to study the evolution of states as they approach the highly unstable states in

on the Bloch sphere.

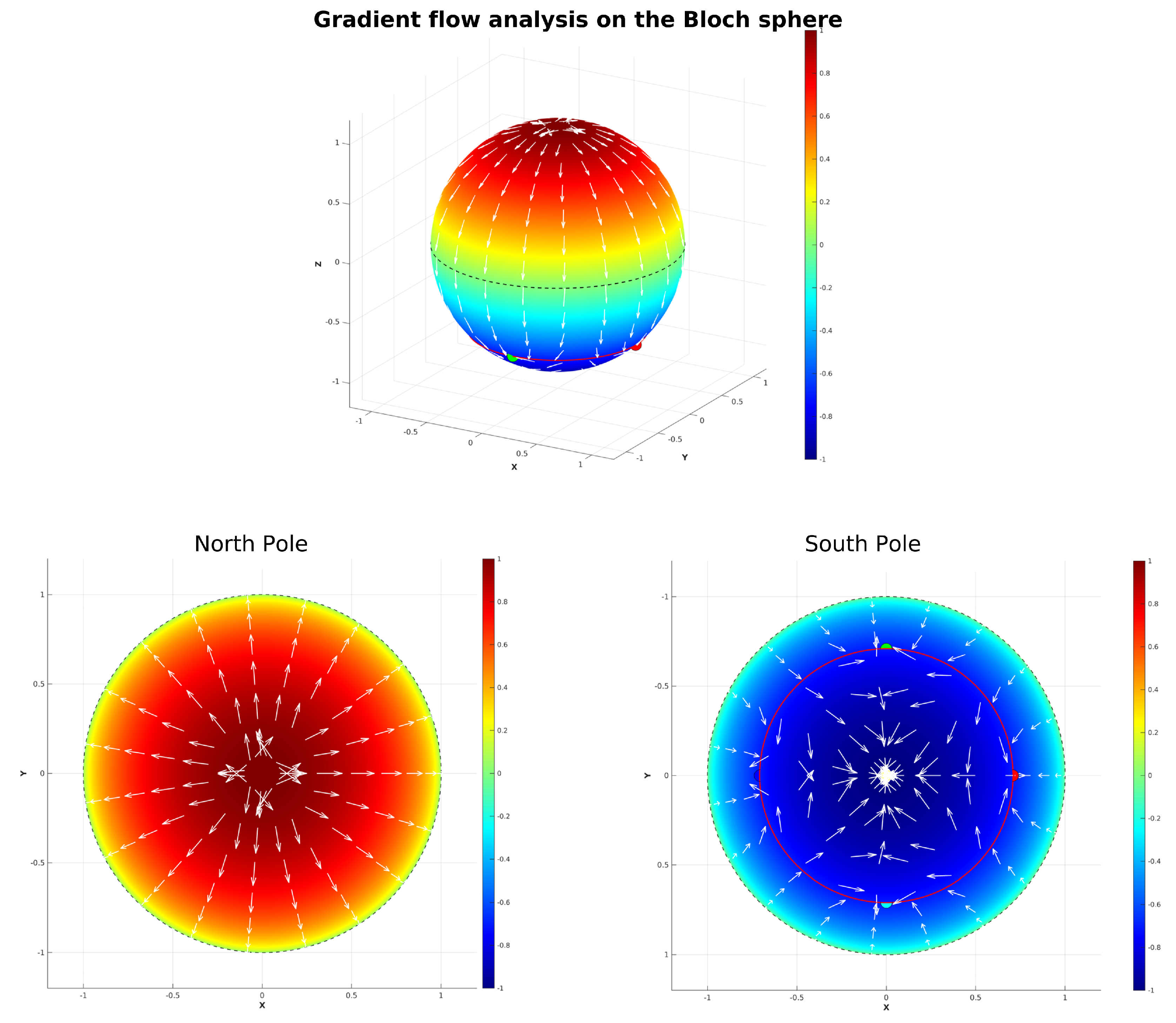

3.9.1. Gradient Flow Analysis on the Bloch Sphere

The function

where

are defined in (

70) is constructed as a scalar potential function (or a Lyapunov-like function) on the Bloch sphere,

, whose global minima are precisely the five unstable points in the set

in (

53). These minima occur at the four points on the three-quarter circle (

) with

, and at the south pole (

). By computing the negative gradient,

, we define a gradient dynamical system

The integral curves (trajectories or flow lines) of this vector field represent paths of steepest descent on the potential surface

h . Plotting these trajectories visualizes the basins of attraction for each of the five special points under this gradient flow. This analysis provides topological insights into the phase portrait of the original system by partitioning the Bloch sphere according to the influence of these unstable points and their effect on solving the system using the ODE45 method. By visualizing the trajectories that follow

on the Bloch sphere, we can identify the resulting in a gradient field structure where the set

of unstable points form a

symmetry in the

direction is preserved by the gradient flow due to the periodic structure of

. This partitioning reveals how the Bloch sphere is divided into the two distinct regions, Northern and Southern hemisphere, where quantum states in each region are attracted to their corresponding decoherence hotspot, either the South pole, or the four concentric points on the Braiding ring

(see

Figure 11).

The flow lines in

Figure 11 indicate that unstable points near

act as attractors for certain states descending from the North Pole. As shown in the figure, the gradient structure around the South Pole reveals a complex flow pattern towards the attractor at the South Pole. The deep red region near the North Pole, corresponding to the highest gradient values, shows that decoherence and dephasing drive states as a source toward the South Pole, while the gradient flow (white arrows) reveals this as the dominant evolution pathway. The gradient lines evolve globally away from the third quarter circle (

), exhibiting bidirectional flow, toward the South Pole (dominant pathway), and back toward the North-West and North-East near four specific points on the third quarter circle. This behavior, clearly visible in

Figure 11 (South pole image), reveals that the third quarter circle acts as a topological transition region, by the specific Lyapunov function. The gradients around both the South Pole and this quarter circle show bifurcating flows, creating what may be described as an open barrier that introduces disorder in the evolution of states.

These observations demonstrate a topological tendency of the solutions of the GKSL equation where the third quarter-circle at

acts as a transition region and the states can evolve both slightly Northward and due Southward. The system thus exhibits a topological transition containing unstable states and trajectories, with gradient-driven evolution creating complex flow patterns around these selected unstable points in (

53).

It is worth noting that these critical points simply emerge from the global shape of

h and do not affect the form of the gradient field itself. The ‘camel-like” geometry of the entropy thus arises solely from the interplay of the Hamiltonian and dissipative terms encoded in

h, rather than from any special, localized influence of the unstable points. This implies that the gradient flow trajectories around the unstable point is real also in a physical experiment, as long as we consider the points in

in (

53) as “special” or “different”, and hence are evaluated in

h by being outside the desired stability against decoherence of states under the camel-like framework.

Finally, we note that the trajectories on the Bloch sphere represent a multitude of different transitions between pure states under an entirely unitary evolution, as they remain on the surface of the Bloch sphere. In a physical case, this would be represented by a series of diffractometers for beamed photons which preserves the purity while changing their polarization. Conclusively, in this section, we have thus constructed a Lyapunov function based on five highly unstable quantum states under the camel-like framework by their entropy plot in

Figure 9, in order to design an trajectory path for the evolution of states under a completely unitary and real experiment in quantum information, so that we can predict the evolution of quantum states under the camel-like framework. It is also worth noting, that the North Pole represents the most stable point in terms of decoherence-resistance, and the South, represents the most unstable. By the gradient field we have designed here, the instability of states is thus not related to instability/stability towards decoherence, but stability and instability based on the gradient flow values that

attains on the Bloch sphere, which are useful for the mapping we have presented in

Figure 11.

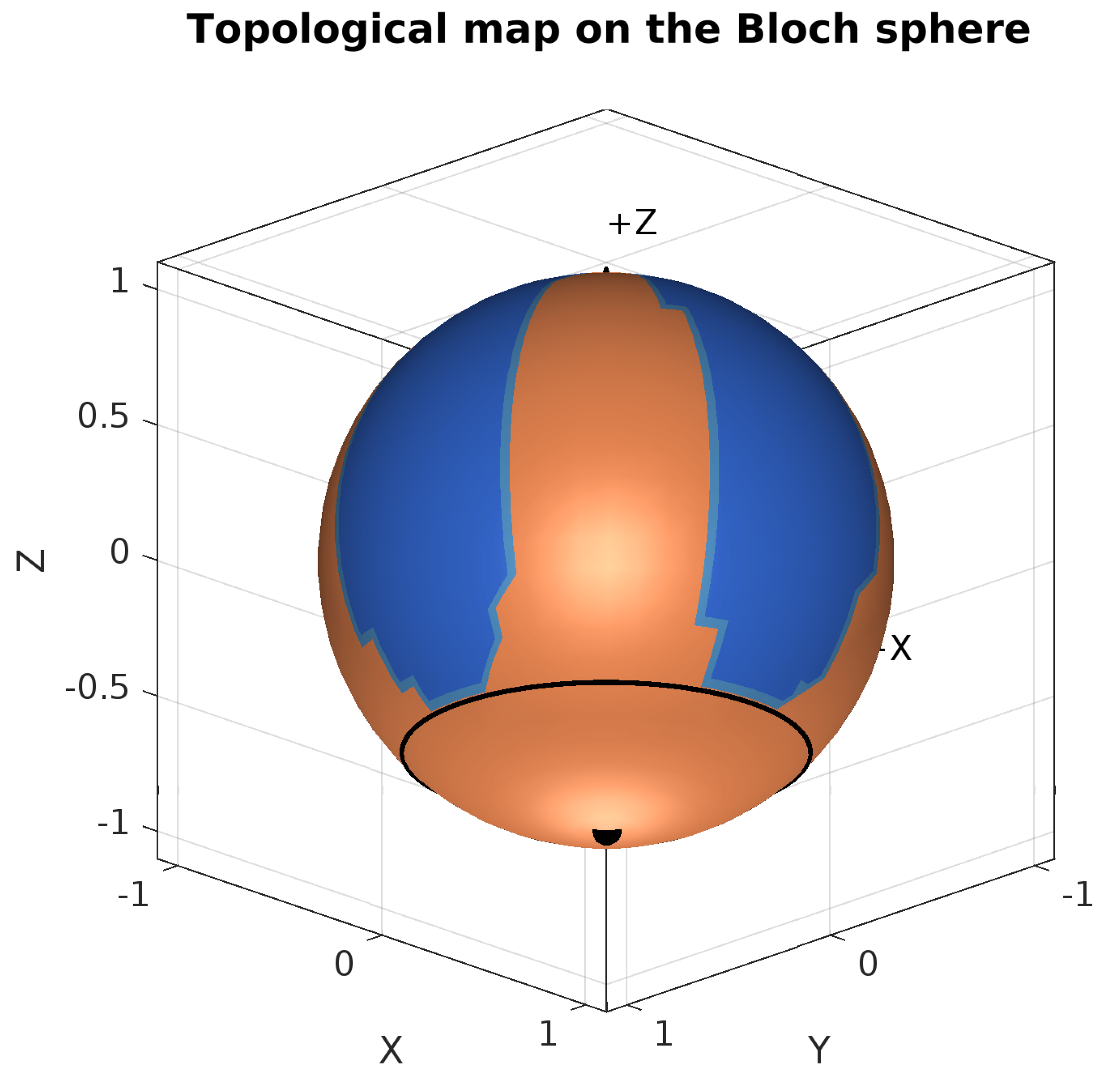

3.9.2. Topological Constraints on the Bloch Sphere

With the notion that the North pole acts as a source and the South pole’s as an attractor by considering the gradient field dynamics, we can form a basic basin map and analyze the evolution of the stability of the quantum states subdivided into topological basins. We develop this analysis from the quantum system’s fundamental functions given in (

70). The gradient flow dynamics are derived from the potential function

, with the evolution equations

which we derive from the Riemann flow on the

sphere [

37]. Following these dynamics, we classify the quantum state space into distinct basins:

The boundaries of each basin are defined as a manifold with boundary and can thus be viewed as compact topological sets on the Bloch sphere, which can be assigned well-defined closures and where any calculation will converge within the established boundaries. We can thus define these basins topologically as:

where

and

. Here,

represents the

-neighborhood around the point

, and

are distinct basins. The unstable points (in terms of decoherence) of the system given in (

53) are characterized by:

We plot the subdivision of basins on the Bloch sphere in

Figure 12 based on this Riemannian flow geometry, where the topological ridge sinks toward the third quarter circle on periodic longitudes where we have the Braiding ring, composed of unstable states. This gives two basins, displayed in red and blue, where field lines move towards the South Pole from the North pole, north of

.

In

Section 3.9.4 we shall discuss the physical implications of this topological manifold. Meanwhile, we form a theorem summarizing the results from topological analysis of the solutions of the GKSL equation under the camel-like framework.

Theorem 2 (Global Convergence on the Bloch Sphere).

Consider the gradient flow of the function on , where

Then:

The unstable points in terms of rapid decoherence consist of the critical points by the south pole , and four saddle points at . Also, the North pole is a critical point, however stable in terms of decoherence.

The south pole is a global attractor: for all initial conditions , the flow converges to .

Proof.

(1) Critical points satisfy . Since , we have . At : but , and , giving isolated critical points. At : both due to the factor . At : and when or , yielding four saddle points.

(2) Since

and

for all

, the south pole is the unique global minimum. Furthermore, along any trajectory of the gradient flow

, the function

h decreases:

This means that h always decreases (or stays constant) along trajectories, which can be seen in the gradient plot. Since the sphere is bounded and everywhere, h must approach some limiting value. The only points where trajectories can stop are where (the critical points). At the north pole and saddle points on the third quarter circle, small perturbations cause trajectories to move away (since h decreases from these points). However, at the south pole where (the minimum), trajectories cannot decrease h further, so they must stop. Therefore, all trajectories eventually reach the south pole, making it the global attractor. □

Remark 1. It is important to note that the notion of instability described by the gradient flow differs from the instability observed in the von Neumann entropy plots in Figure 9. The gradient flow instability arises from the rate at which the Lyapunov-like function changes over the Bloch sphere, whereas the decoherence-related instability of the states in the set is due to their susceptibility to the dissipation operator in the GKSL equation under the camel-like entropy framework, which we precisely observe in Figure 9. The gradient field of the Lyapunov function thus illustrates a descent from decoherence-stable states (North Pole) toward decoherence-sensitive ones (South Pole).

3.9.3. Evolution by Purity in the Bloch Ball

In this section, we investigate the evolution of pure states on the Bloch ball (where the entire space inside

is considered as a vector space of solutions), following the properties of the GKSL equation under the camel-like framework. The evolution starts from pure states (on the Bloch sphere -

) to mixed states in the center of the Bloch ball (a dense globular manifold). The evolution on the Bloch ball is tracked to simulate a pair of entangled particles that are passed through a series of diffractometers and electromagnetic fields, rearranging their polarity and reducing their state of purity into mixed state. Naturally, this process is entirely irreversible due to the uncertainty principle, and evolves from the Bloch surface to the center, following the paths allowed by the GKSL equation under a camel-like framework. These paths should not be confused with the gradient paths in the

manifold from

Figure 11, where the gradient field lines determine the evolution paths from pure metastable states to stable pure states (stability in the sense of being an admissible solution to the GKSL equation).

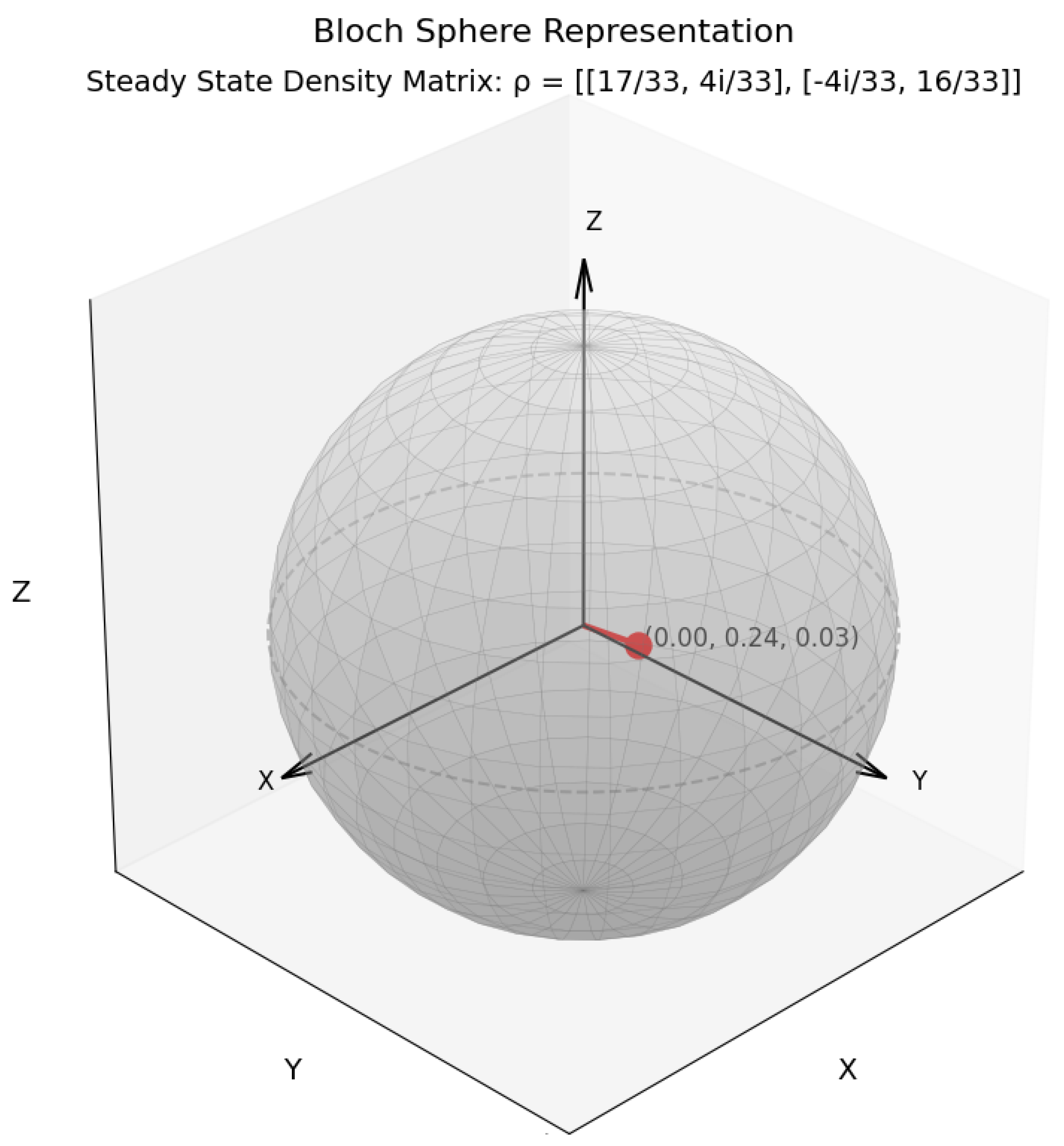

The universal steady state, the great attractor of all states under the GKSL equation in the camel-like framework, is computed in

Python and presented as the density matrix shown in

Figure 13.

3.9.4. Relevance for Physics

The Lyapunov function with four singularities on an unstable equilibrium circle represents a geometric quantum control framework that actively avoids the most decoherence-prone states on the Bloch sphere. These four points at

are fully admissible pure quantum states, but they exhibit the fastest decoherence rates in the system, making them the most fragile states to maintain coherence by the notion of stability of states in quantum information experiments [

38,

39]. By strategically placing singularities of

at these four maximally-decohering points, the gradient flow creates a control landscape that steers quantum trajectories away from these vulnerable regions, effectively implementing a decoherence-avoiding quantum control protocol [

40]. This approach differs from traditional geometric phase schemes by explicitly incorporating decoherence information into the Lyapunov function design, where the unstable manifold at

represents the locus of states with maximal environmental coupling [

41]. The resulting flow pattern, with its characteristic basin structure, ensures that quantum states rapidly escape the high-decoherence region and converge to the more stable states, thereby minimizing exposure to decoherence throughout the evolution [

38,

40]. This framework can be experimentally realized using polarization qubits passing through engineered diffractometers, where polarization-dependent diffraction losses implement the Lyapunov function

. Specifically, using a first diffractometer we create the

dependence through selective polarization, while a second holographic diffractometer implements

by creating null diffraction points (the unstable states we call “singularities”) at the four decoherence-prone states [

42,

43]. The measurement backaction from photons lost to higher diffraction orders drives the remaining zero-order photons along the gradient flow trajectories, effectively steering them away from the fragile states at

toward the decoherence-protected south pole [

44].