1. Introduction

Legumes play a crucial role in agricultural systems due to their ability to establish symbiotic associations with nitrogen-fixing bacteria, thereby reducing dependence on mineral fertilizers and enhancing soil fertility [

1,

2]. However, the efficiency of biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) varies considerably among species, genotypes, and edaphoclimatic conditions, which has prompted the development of microbial strategies to optimize this interaction [

3,

4].

Lima bean (

Phaseolus lunatus L.), a member of the Fabaceae family, is a legume of high nutritional value and broad adaptability to tropical environments [

5]. Despite this potential, its productivity in Brazil remains low, averaging 329 kg ha

-1 in 2024 [

6], often limited by poor nodulation efficiency and low nitrogen and organic matter availability in soils [

7,

8,

9]. Although

P. lunatus can establish symbiotic relationships with diazotrophic bacteria for BNF, this potential is frequently underexploited due to the absence of specific inoculants and the variability in nodular response among varieties [

10,

11,

12].

In this context, co-inoculation with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) has emerged as an effective approach to improve nodulation, nitrogen metabolism, nutrient uptake, and plant growth, while reducing the dependence on chemical fertilizers and enhancing soil quality [

13,

14,

15,

16]. The efficiency of PGPR is strongly influenced by the compatibility between plant genotype and microorganism, as well as by environmental conditions, leading to variable responses across varieties and cultivation sites [

13,

14].

Among the most studied PGPR,

Bradyrhizobium elkanii is widely recognized for its role in symbiotic nitrogen fixation, whereas

Azospirillum brasilense promotes root growth and nutrient uptake through the synthesis of phytohormones such as indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and abscisic acid (ABA), in addition to phosphate solubilization and siderophore production [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Studies in soybean, common bean, and cowpea have shown that co-inoculation with

Rhizobium and

Azospirillum species can produce synergistic effects, enhancing nodulation, biomass accumulation, and tolerance to abiotic stresses [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. These effects are often attributed to increased availability of assimilable nitrogen, greater root surface area, and modulation of biochemical processes associated with nutrient assimilation and energy metabolism [

26,

27,

28].

Despite the promising evidence in other legumes, the potential of co-inoculating these PGPR in P. lunatus remains poorly explored. Given the physiological and symbiotic particularities of this species, it is essential to understand how different inoculation strategies (single or combined) influence nodulation, nitrogen metabolism, nutrient uptake, and soil quality parameters. Assessing these factors together allows for the investigation of plant-soil feedback mechanisms and the potential of microbial practices to enhance physiological performance over the medium to long term.

From this perspective, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of single and combined inoculation with strains of Bradyrhizobium elkanii and Azospirillum brasilense on root nodulation, nitrogen metabolism, macronutrient uptake, and morphological traits in different lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus) varieties, as well as on soil fertility indicators after cultivation.

2. Results

2.1. Root Nodulation

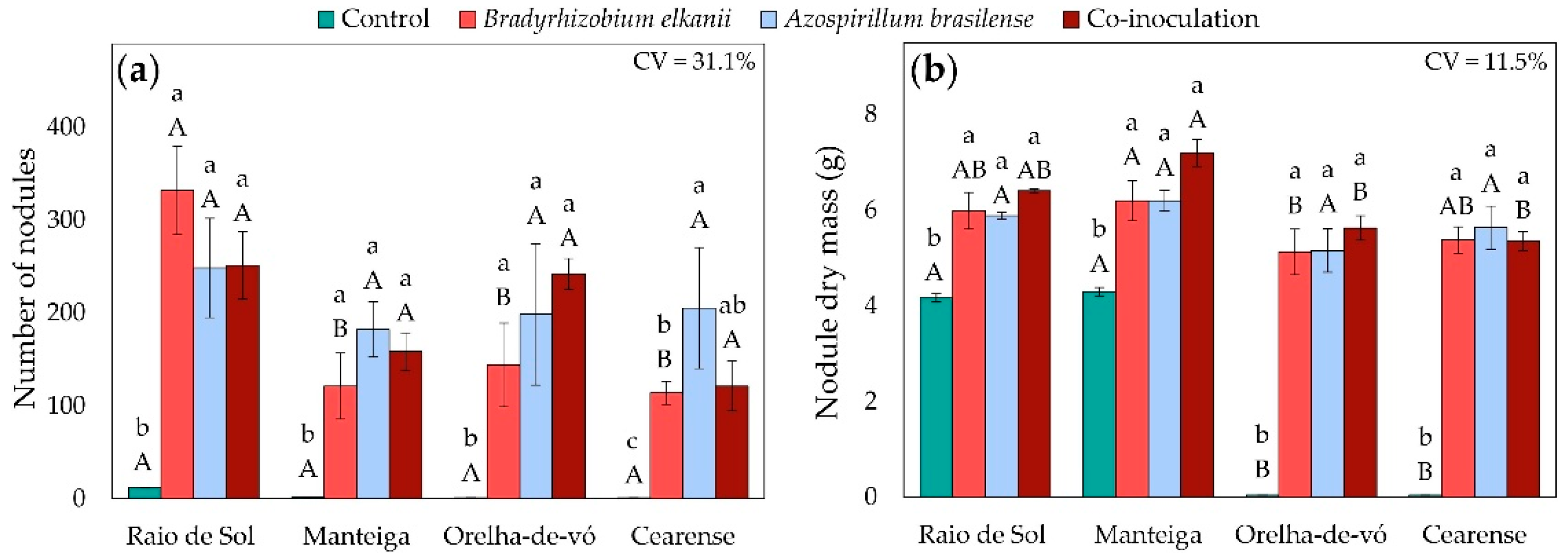

Four lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus) varieties, known in Brazil as ‘Raio de Sol’, ‘Manteiga’, ‘Orelha-de-vó’, and ‘Cearense’, were subjected to inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii (strain BR 2003) and Azospirillum brasilense (strain Ab-V5), their co-inoculation, and a non-inoculated nitrogen-fertilized control. Factorial ANOVA revealed significant effects of both variety and inoculation treatment on nodule number and nodule dry mass.

All inoculation treatments significantly increased both parameters compared with the non-inoculated control (

Figure 1). In the control, the mean numbers of nodules per plant were 12, 2, 1, and 1 for ‘Raio de Sol’, ‘Manteiga’, ‘Orelha-de-vó’, and ‘Cearense’, respectively (

Figure 1a). Inoculation with

B. elkanii,

A. brasilense, or their combination resulted in substantial increases in nodulation and nodule biomass across all varieties. The varieties ‘Raio de Sol’, ‘Manteiga’, and ‘Orelha-de-vó’ produced averages of 277, 154, and 195 nodules, respectively, with no significant differences among inoculation treatments. In ‘Cearense’, the mean number of nodules under all inoculated conditions was 147. Nodule dry mass followed the same trend, showing pronounced increases for all inoculated plants (

Figure 1b).

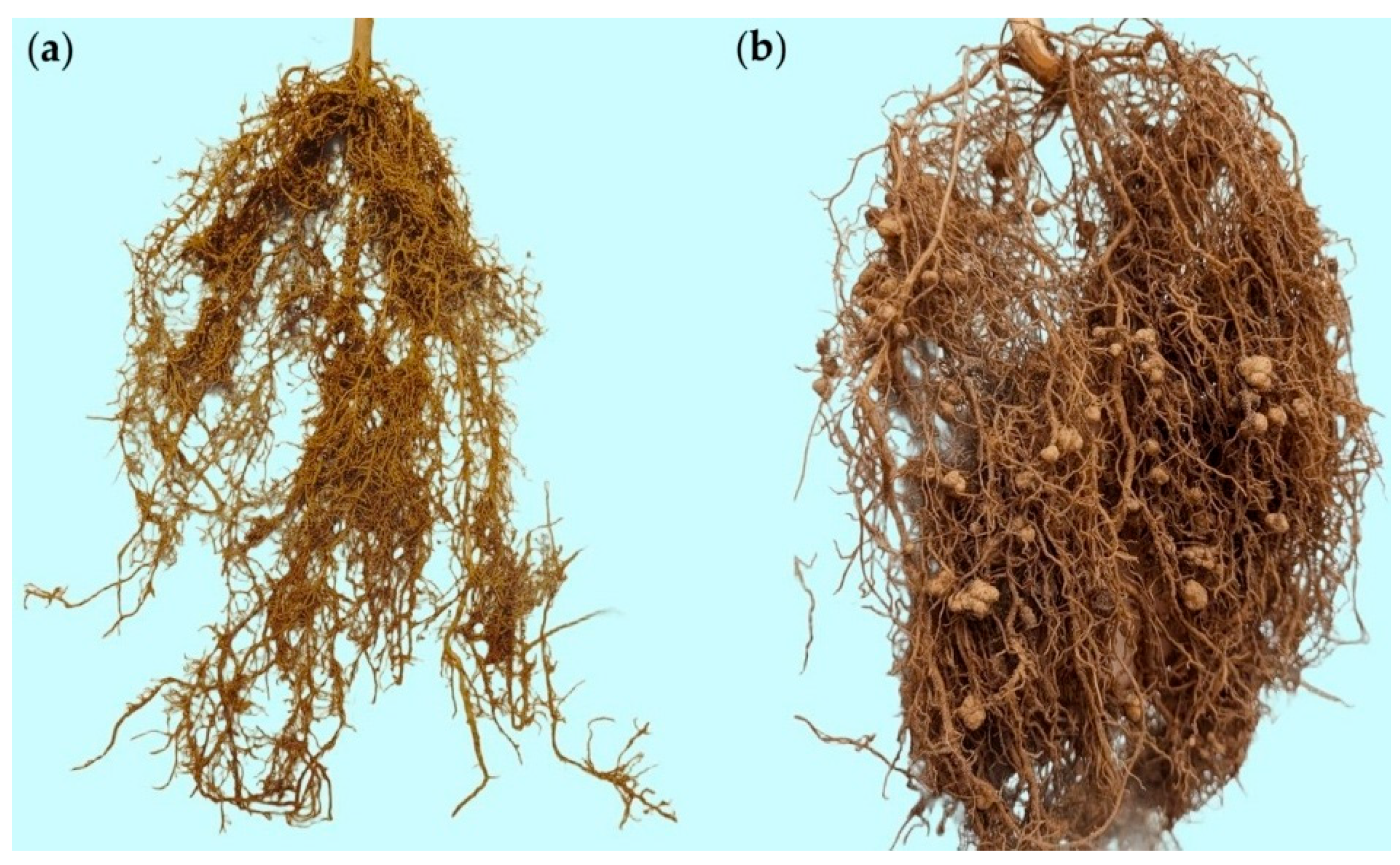

Representative root samples of the ‘Raio de Sol’ variety are shown in

Figure 2. Roots from the non-inoculated control (

Figure 2a) and those inoculated with

B. elkanii (

Figure 2b) illustrate the difference in nodulation intensity, confirming the quantitative results of

Figure 1a. Inoculated plants developed a markedly higher number of nodules, which were distributed along both primary and lateral roots, predominantly spherical, smooth-surfaced, and light brown externally. When sectioned, nodules exhibited a pink interior, indicative of active nitrogen fixation.

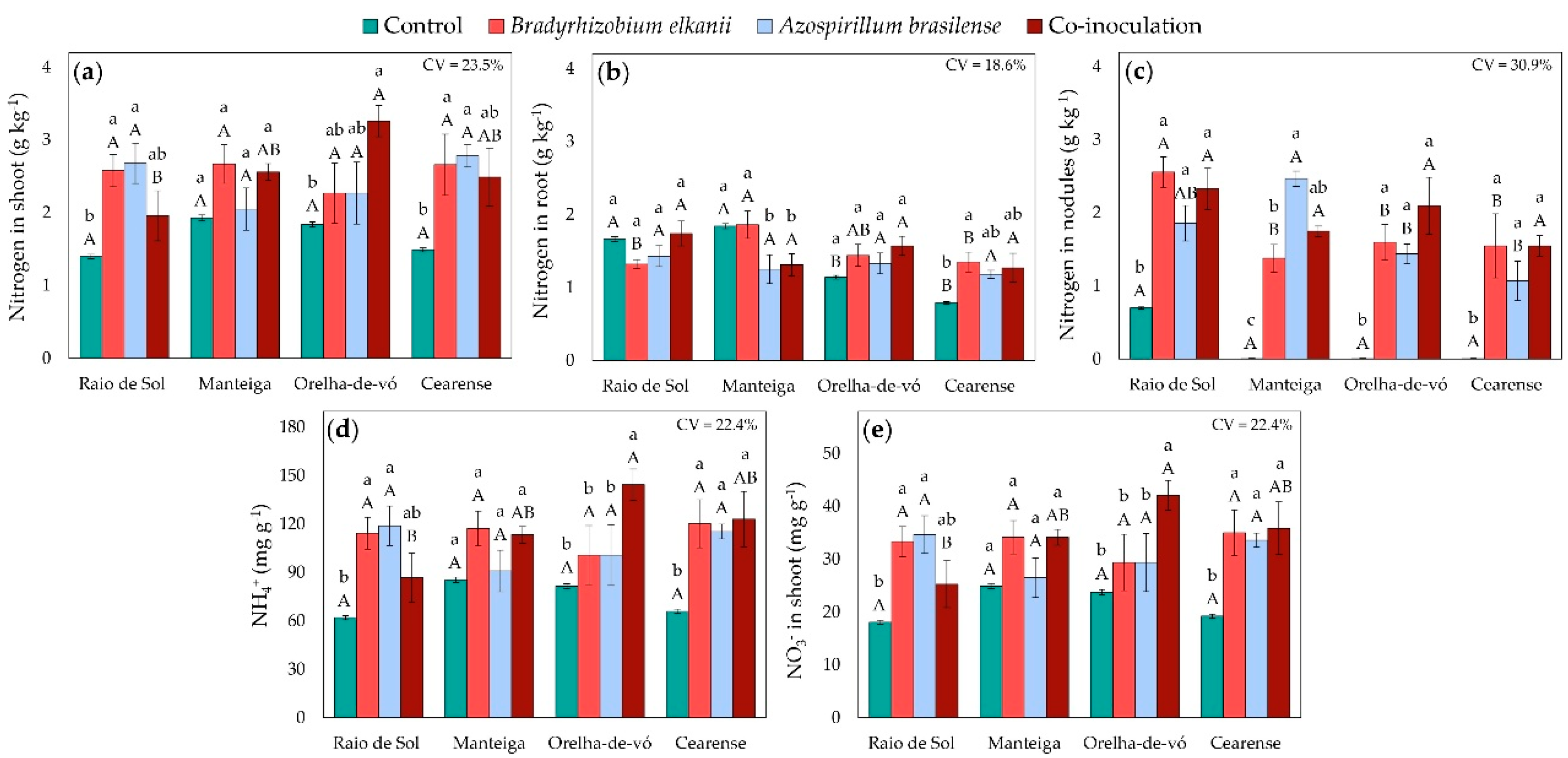

2.2. Nitrogen Accumulation in Different Plant Organs

Factorial ANOVA showed that the interaction between variety and inoculation treatment significantly affected nitrogen contents in shoots, roots, and nodules, as well as NH

4+ and NO

3- concentrations in shoots. In the ‘Raio de Sol’ variety, plants inoculated with

B. elkanii or

A. brasilense exhibited shoot nitrogen contents 84% and 91% higher than the control, respectively (

Figure 3a). Similarly, in ‘Cearense’, the same treatments increased shoot nitrogen contents by 79% and 87%. Co-inoculation significantly increased shoot nitrogen only in the ‘Orelha-de-vó’ variety, by 77% relative to the control, while none of the inoculation treatments affected shoot nitrogen in ‘Manteiga’.

In roots, nitrogen contents in ‘Raio de Sol’ and ‘Orelha-de-vó’ did not differ significantly among treatments (

Figure 3b). In ‘Cearense’,

B. elkanii inoculation increased root nitrogen content by 78% compared with the control, whereas other treatments showed no differences. In contrast, in ‘Manteiga’, root nitrogen contents under

A. brasilense inoculation alone and co-inoculation were 32% and 29% lower, respectively, than the control.

Nodule nitrogen contents were higher in all inoculated plants compared with the control (

Figure 3c). In ‘Raio de Sol’, the control treatment showed 0.7 g kg

-1, while in ‘Manteiga’, ‘Orelha-de-vó’, and ‘Cearense’ controls, no nodule nitrogen was detected. In ‘Raio de Sol’, all inoculated treatments increased nodule nitrogen by an average of 221%, reaching 2.25 g N kg

-1 dry weight. Across the inoculated treatments of ‘Raio de Sol’, ‘Orelha-de-vó’, and ‘Cearense’, nitrogen contents ranged from 1.07 to 2.56 g N kg

-1, with no significant differences among bacterial treatments.

Regarding inorganic nitrogen forms, only the ‘Manteiga’ variety showed no significant differences in shoot NH

4+ (

Figure 3d) and NO

3− (

Figure 3e) contents among treatments. In the other varieties, inoculation enhanced both variables, although the magnitude varied by genotype. In ‘Raio de Sol’,

A. brasilense and

B. elkanii individually promoted the highest NH

4+ and NO

3− levels, increasing them by 92% and 84% relative to the control. In ‘Orelha-de-vó’, co-inoculation produced the highest ammonium and nitrate concentrations, both increasing by 77%. In ‘Cearense’, all inoculated treatments enhanced NH

4+ and NO

3− contents by an average of 81% over the control.

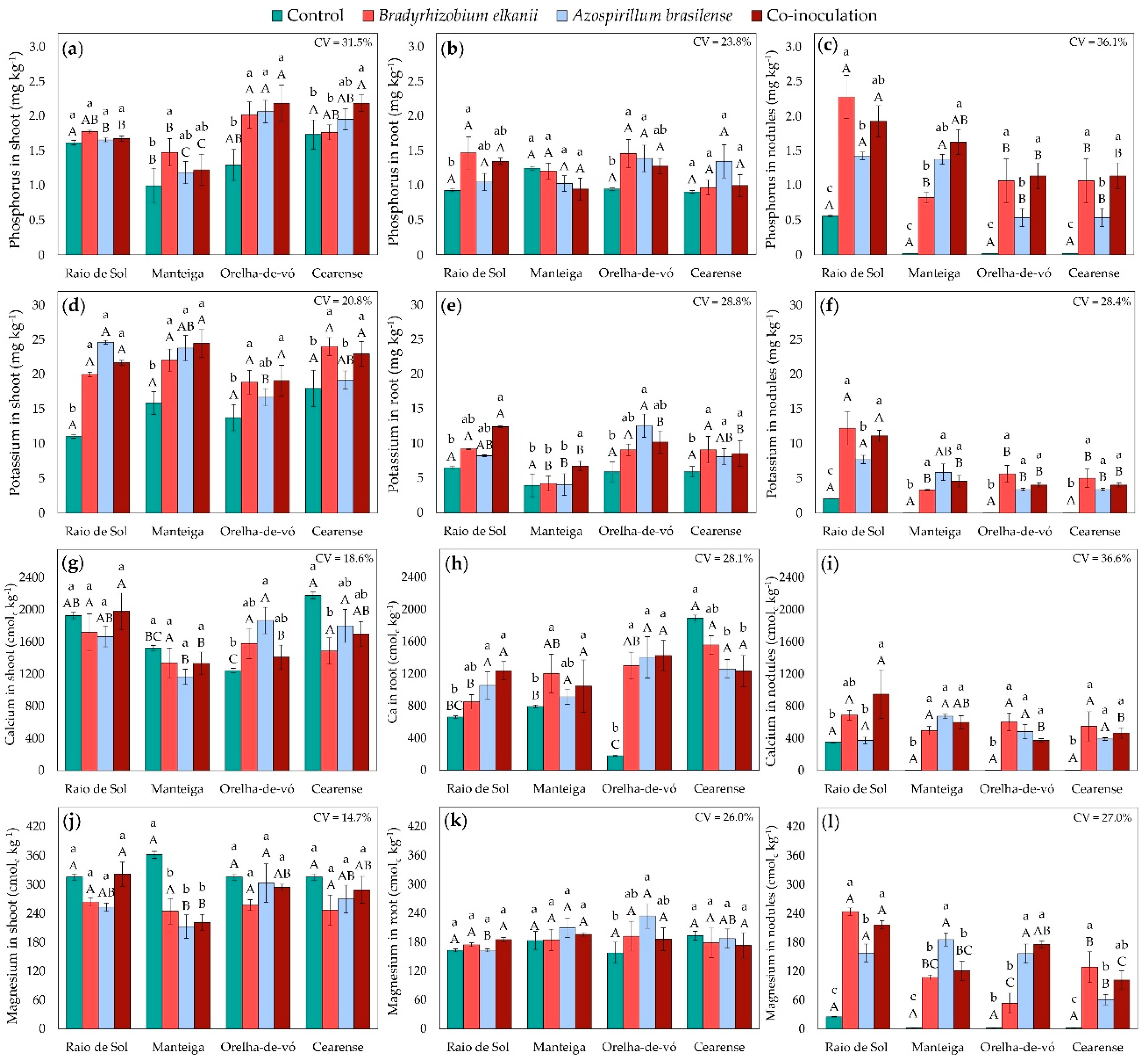

2.3. Nutrient Contents in Different Plant Organs

Macronutrient accumulation in lima bean plants was significantly influenced by inoculation treatments and varied among cultivars. Factorial ANOVA revealed significant effects of treatment on phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium concentrations in shoots, roots, and nodules.

Shoot phosphorus (

Figure 4a) responses varied among cultivars. In ‘Raio de Sol’, no significant differences were detected between inoculated and control plants. In ‘Manteiga’, inoculation with

B. elkanii increased shoot P by 48% relative to the control. All inoculation treatments enhanced shoot P in ‘Orelha-de-vó’ by an average of 61%, with no significant differences among treatments. In ‘Cearense’, only co-inoculation significantly increased shoot P, by 26% compared with the control. Root P (

Figure 4b) was significantly higher following

B. elkanii inoculation in ‘Raio de Sol’ and ‘Orelha-de-vó’, with increases of 58% and 54%, respectively. In ‘Orelha-de-vó’,

A. brasilense also increased root P by 46% compared with the control.

In ‘Manteiga’, ‘Orelha-de-vó’, and ‘Cearense’, the extremely low nodulation observed in non-inoculated controls (

Figure 1a) resulted in negligible P (

Figure 4c), K (

Figure 4f), Ca (

Figure 4i), and Mg (

Figure 4l) contents in nodules. In contrast, all inoculated plants exhibited marked increases in nodule macronutrient contents, with ‘Raio de Sol’ showing the highest overall values. In this variety, which also presented the greatest number of nodules among control plants, nodule P content increased from 0.56 mg kg

-1 in the control to 2.28 mg P kg

-1 dry mass following

B. elkanii inoculation, a 307% increase.

Shoot potassium (

Figure 4d) generally increased under inoculation. In ‘Raio de Sol’ and ‘Manteiga’, inoculation with

B. elkanii,

A. brasilense, or their combination produced similar shoot K concentrations, averaging 100% and 48% higher than the control, respectively. In ‘Orelha-de-vó’ and ‘Cearense’,

A. brasilense alone did not differ from the control, whereas

B. elkanii and co-inoculation increased shoot K by 38% and 31%, respectively. Root potassium (

Figure 4e) also rose significantly in co-inoculated plants, with increases of 90% in ‘Raio de Sol’ and 70% in ‘Manteiga’. In ‘Orelha-de-vó’,

A. brasilense increased root K by 112%, while in ‘Cearense’, all inoculated treatments showed similar root K levels, averaging 45% higher than the control.

Shoot calcium (

Figure 4g) exhibited cultivar-specific patterns. No significant differences were observed in ‘Raio de Sol’ or ‘Manteiga’. In ‘Orelha-de-vó’,

A. brasilense increased shoot Ca by 50%. In ‘Cearense’, shoot Ca contents were similar among control,

A. brasilense, and co-inoculated plants, whereas

B. elkanii reduced shoot Ca by 32% compared with the control. Root Ca (

Figure 4h) largely mirrored these trends. Treatments did not differ in ‘Raio de Sol’ or ‘Manteiga’. In ‘Orelha-de-vó’, all inoculations produced similar root Ca, increasing it by approximately 660% compared with the control. In ‘Cearense’, root Ca was highest in the control and statistically similar to

B. elkanii;

A. brasilense and co-inoculation produced lower, though still comparable, levels to the higher values observed in other cultivars.

Magnesium accumulation showed clear organ- and cultivar-specific trends. Foliar Mg (

Figure 4j) was not enhanced by inoculation in any cultivar and was 37% lower than the control in ‘Manteiga’. Root Mg (

Figure 4k) remained unaffected in ‘Raio de Sol’, ‘Manteiga’, and ‘Cearense’, but in ‘Orelha-de-vó’,

A. brasilense increased root Mg by 48%.

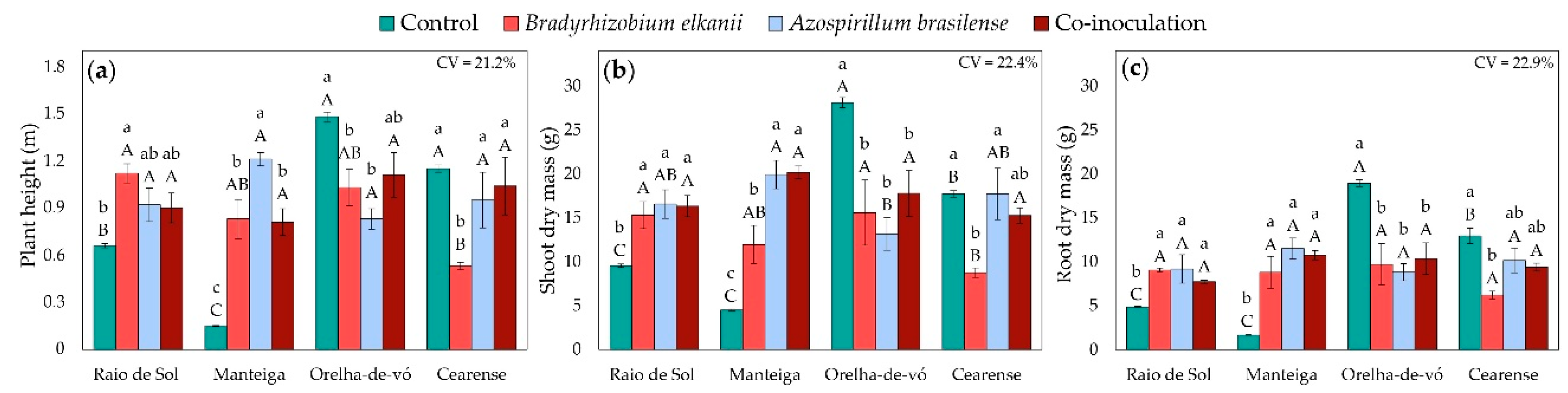

2.4. Plant Growth and Biomass Accumulation

Growth and biomass traits were significantly influenced by the interaction between lima bean varieties and inoculation treatments, as revealed by factorial ANOVA. In ‘Raio de Sol’, inoculation with

B. elkanii increased plant height by 70% compared with the control (

Figure 5a). The ‘Manteiga’ variety exhibited the most pronounced response, with

A. brasilense,

B. elkanii, and co-inoculation increasing plant height by 707%, 453%, and 440%, respectively. Conversely, ‘Orelha-de-vó’ displayed an opposite trend, with the control producing the tallest plants, although co-inoculated plants did not differ significantly from the control. In ‘Cearense’, plant height was similar among the control,

A. brasilense, and co-inoculated treatments, while

B. elkanii inoculation alone resulted in the lowest values.

Dry matter accumulation across organs followed the same general trend as plant height. In both ‘Raio de Sol’ and ‘Manteiga’, all inoculation treatments produced the highest shoot (

Figure 5b) and root (

Figure 5c) biomass. In ‘Raio de Sol’, the three inoculation treatments did not differ significantly from each other and increased shoot and root dry mass by 68% and 78%, respectively, compared with the control. In ‘Manteiga’,

B. elkanii,

A. brasilense, and co-inoculation increased shoot dry mass by 166%, 343%, and 348%, respectively, while root dry mass rose by an average of 527% across inoculated treatments.

In contrast, ‘Orelha-de-vó’ exhibited the highest shoot and root biomass in control plants, indicating a negative response to inoculation. In ‘Cearense’, the control, A. brasilense, and co-inoculated plants showed greater biomass accumulation in both organs, whereas B. elkanii alone produced the lowest shoot and root dry masses.

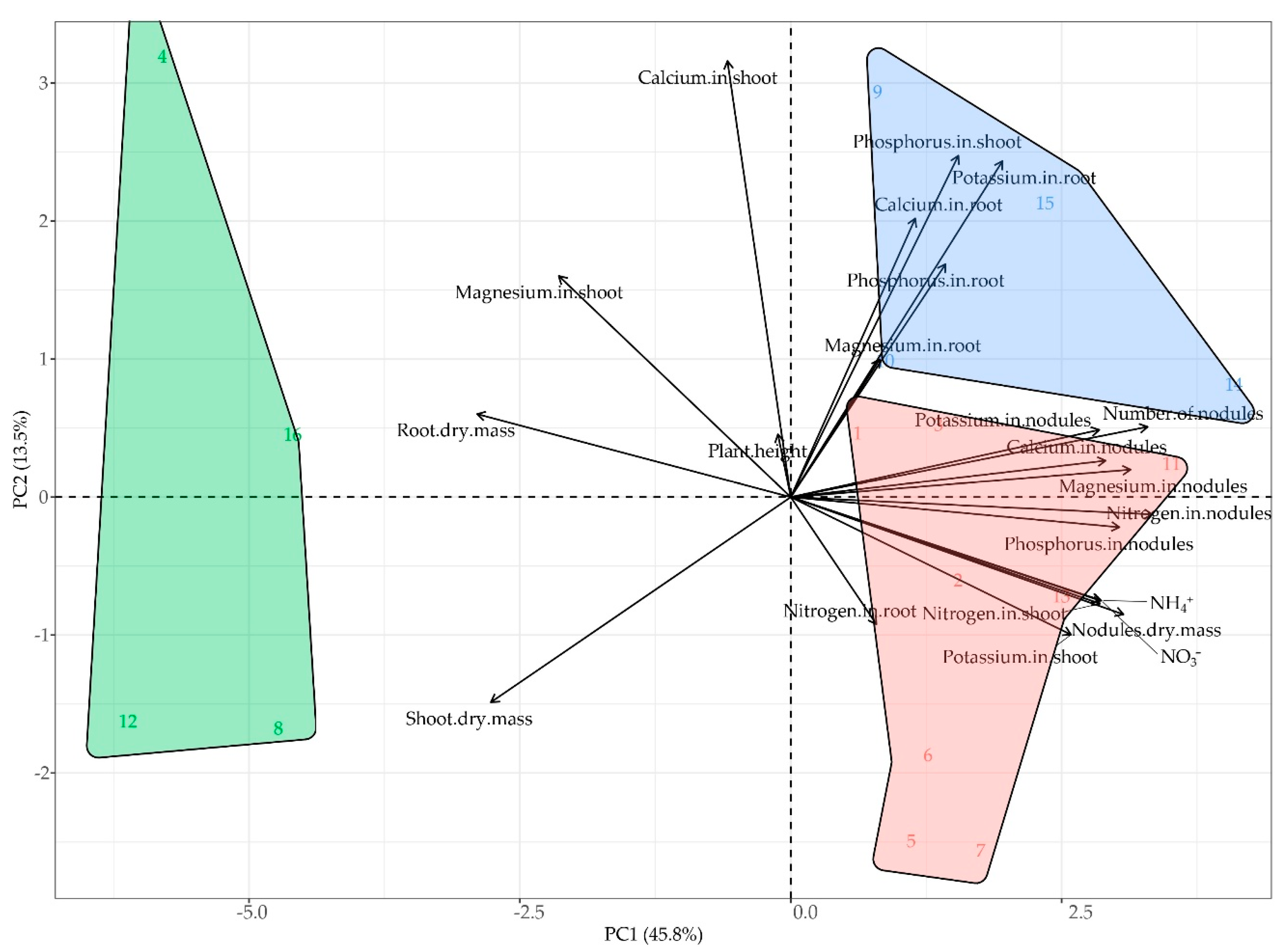

2.5. Principal Components Analysis (PCA) of Plant Traits

was conducted on the standardized dataset comprising variables related to nodulation, nutrient contents, and plant growth and biomass traits, with the objective of summarizing multivariate patterns among lima bean varieties and inoculation treatments. The first two components explained 45.8% (PC1) and 13.5% (PC2) of the total variance, cumulatively accounting for 59.3% (

Figure 6).

PC1 represented a gradient contrasting nutrient accumulation and nodule development with growth and biomass traits. Nodulation parameters and shoot nutrient contents projected toward the positive direction of PC1, while total shoot and root biomass loaded negatively. PC2 captured additional variation associated with calcium and phosphorus uptake in shoots and potassium accumulation in roots.

The ordination revealed treatment-related clustering. Uninoculated controls and nitrogen-fertilized plants from all four varieties were grouped in the biplot region associated with lower nodulation and reduced nutrient contents (green cluster). The blue cluster, concentrated in the upper quadrants, included ‘Orelha-de-vó’ inoculated with A. brasilense (single inoculation) and B. elkanii (single inoculation), as well as ‘Raio de Sol’ inoculated with B. elkanii or co-inoculated, showing enhanced phosphorus and calcium uptake in shoots. The red cluster, primarily located in the lower right quadrant, comprised ‘Cearense’ and ‘Manteiga’ under all inoculation treatments, ‘Orelha-de-vó’ under co-inoculation, and ‘Raio de Sol’ with A. brasilense, associated with greater nodulation, higher nutrient accumulation in nodules, and increased nitrogen and phosphorus assimilation.

Overall, the PCA clearly differentiated uninoculated treatments, characterized by lower nutritional profiles, from inoculated treatments, which segregated into two performance clusters. However, no consistent distinction was observed between single and co-inoculation treatments.

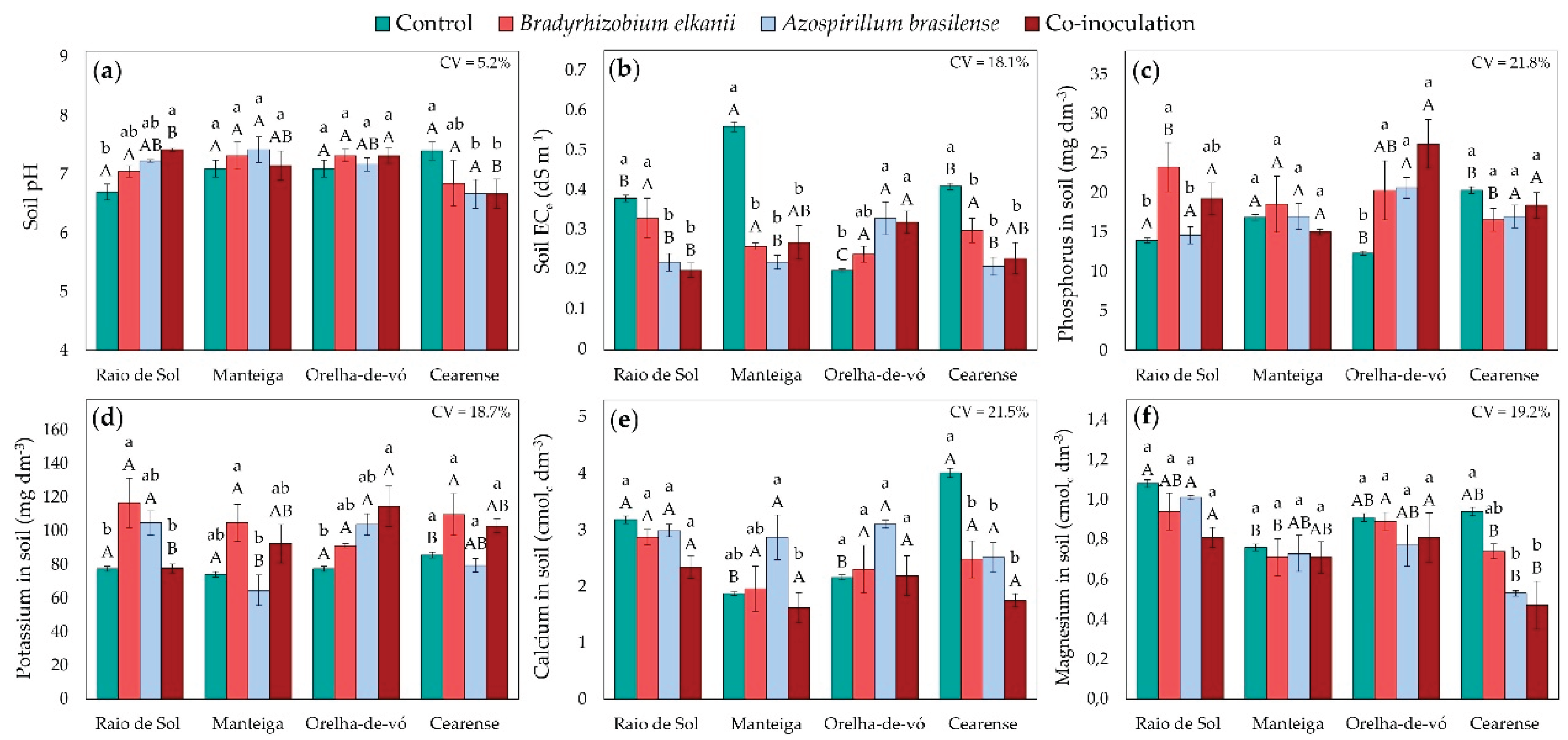

2.6. Soil Fertility Indicators

In addition to plant traits, soil fertility parameters were evaluated after the cultivation of lima bean varieties inoculated with B. elkanii, A. brasilense, their co-inoculation, and the non-inoculated control. Factorial ANOVA revealed significant treatment effects on soil pH, electrical conductivity of the saturated paste extract (ECe), and the concentrations of phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium.

In soils cultivated with the variety ‘Raio de Sol’, co-inoculation with

B. elkanii and

A. brasilense increased pH to 7.42 compared with 6.7 in the non-inoculated control (

Figure 7a). Conversely, in ‘Cearense’, inoculation with

A. brasilense and co-inoculation resulted in a mean pH of 6.7, while the control soil reached 7.4. No significant pH differences were detected among treatments for the remaining varieties.

For soils cultivated with ‘Raio de Sol’, ‘Manteiga’, and ‘Cearense’, the highest EC

e values were observed in the control, whereas single and combined inoculations markedly reduced EC

e (

Figure 7b). In ‘Raio de Sol’, inoculation with

A. brasilense and co-inoculation reduced EC

e by an average of 45%. In ‘Manteiga’, all inoculation treatments decreased EC

e by approximately 55%, and in ‘Cearense’ by about 40% relative to the control. In contrast, in ‘Orelha-de-vó’, higher EC

e values were recorded in soils from plants inoculated with

A. brasilense or co-inoculated.

In soils cultivated with ‘Raio de Sol’, inoculation with

B. elkanii increased phos-phorus concentration by 67% compared with the control (

Figure 7c). Similarly, in ‘Orelha-de-vó’, both single and combined inoculations raised soil P by an average of 81% relative to the control. For the other varieties, phosphorus (

Figure 7c) and potassium (

Figure 7d) concentrations did not differ significantly among treatments. Regarding potassium, inoculation effects were particularly notable: in ‘Raio de Sol’,

B. elkanii inoculation increased soil K by 50% relative to the control, and in ‘Orelha-de-vó’, co-inoculation enhanced soil K by 48%.

For soil calcium (

Figure 7e), no significant differences were detected between control and inoculated treatments in ‘Raio de Sol’ and ‘Orelha-de-vó’. In ‘Manteiga’, inoculation with

A. brasilense increased soil Ca by 53% compared with the control. Conversely, in ‘Cearense’, the control exhibited the highest soil Ca, with all inoculated treatments averaging 44% lower.

For soil magnesium (

Figure 7f), no significant differences were observed among treatments in ‘Raio de Sol’, ‘Manteiga’, and ‘Orelha-de-vó’. However, in ‘Cearense’, soil Mg was highest in the control and decreased by approximately 47% under

A. brasilense inoculation and co-inoculation.

3. Discussion

3.1. Nodulation and Nitrogen Metabolism

Overall, inoculation with

Bradyrhizobium elkanii and

Azospirillum brasilense strains, ei-ther individually or in combination, significantly enhanced nodulation and nitrogen accumulation in different compartments of

Phaseolus lunatus, with responses varying by genotype (

Figure 1 and

Figure 3). This pattern aligns with previous reports of improved nitrogen uptake and yield in legumes subjected to co-inoculation, particularly under conditions of limited mineral nitrogen availability [

21,

22,

29,

30].

While

B. elkanii directly forms root nodules,

A. brasilense acts mainly through indirect mechanisms, including phytohormone synthesis, modulation of root architecture, and alteration of nutrient availability, which can promote rhizobial infection and the formation of functional nodules [

20,

21,

22,

31]. These mechanisms partially explain the increases in nodule number and leaf N content observed under

A. brasilense inoculation, despite its limited direct contribution to BNF [

32].

Inoculation treatments induced distinct redistributions of nitrogen among nodules, roots, and shoots, following genotype-specific patterns. In the ‘Raio de Sol’ and ‘Cearense’ varieties, higher N concentrations in the shoot (

Figure 3a) were associated with increased nodule number (

Figure 1) and greater nodular N content (

Figure 3c), indicating enhanced N transfer to aerial tissues via active nodular metabolism. The concurrent elevation of N levels in nodules and shoots suggests efficient translocation of reduced N and its incorporation into foliar reserves [

33,

34,

35].

Root responses also varied among genotypes. In ‘Cearense’,

B. elkanii inoculation in-creased root N content (

Figure 3b), likely reflecting enhanced inorganic N uptake or retention [

36]. Conversely, in ‘Manteiga’,

A. brasilense and co-inoculation treatments reduced root N relative to the control, possibly due to greater N remobilization toward shoots or shifts in N partitioning, though this response remains poorly characterized in the literature.

The data on nodules reinforces the central role of inoculation in modulating nitrogen metabolism. In all inoculated varieties, nodular N content was significantly higher than in the control (

Figure 3c). Combined with the pink coloration observed in the nodules, this finding indicates elevated metabolic activity, reflecting increased leghemoglobin synthesis and nitrogenase activity that facilitate the export of reduced N to plant tissues [

37,

38]. The observed nodular and foliar N accumulation points to an improvement in both symbiotic fixation and systemic nitrogen assimilation.

The low nodular N content in ‘Raio de Sol’ and the absence of nodules in non-inoculated (mineral N control) plants (

Figure 3c) likely result from mineral nitrogen inhibition of nodule organogenesis and function, mediated by autoregulation pathways and nitrate-dependent signaling that suppress early nodulation stages [

33,

39,

40,

41]. This mechanism plausibly explains the differences between fertilized and inoculated plants.

The increases in foliar NH

4+ (

Figure 3d) and NO

3− (

Figure 3e) pools observed in inoculated treatments provide additional insight into nitrogen metabolism after uptake, suggesting enhanced symbiotic N input, greater root absorption, and/or altered assimilation dynamics [

29,

40,

41]. These results indicate that inoculation and co-inoculation affect both nitrogen acquisition and post-uptake processing, though distinguishing the relative contributions of BNF, assimilation, and redistribution would require isotopic or enzymatic approaches.

In summary, most inoculated plants exhibited concurrent increases in N content across nodules, roots, and leaves, demonstrating improved integration of nitrogen fix-ation, uptake, and redistribution. Elevated nodular N reflects intensified symbiotic ac-tivity, while higher root and foliar N denote efficient translocation of assimilated nitrogen to the shoots. Although confirmation via 15N tracing and enzymatic assays would refine this interpretation, the current evidence clearly supports the potential of inoculation to optimize nitrogen allocation in lima bean..

3.2. Plant Nutrition and Growth

Inoculation with

B. elkanii and

A. brasilense, individually or in combination, induced complex adjustments in the uptake and redistribution of mineral nutrients, reflected in variations in P, K, Ca, and Mg contents across

P. lunatus organs (

Figure 4). These effects were strongly genotype-dependent, indicating that host-microbe compatibility influences nutrient transport and metabolic regulation [

42,

43,

44].

The nutritional improvements were particularly evident in the increased P and K contents in shoots (Figures 4a and 4d) in specific varieties and inoculation combinations, suggesting enhanced nutrient mobilization and allocation to metabolically active tissues. The rise in P content aligns with the known roles of these bacteria in promoting phosphate solubilization and transport, either via organic acid production or by upregulating high-affinity phosphate transporters in roots [

45,

46,

47]. Such effects increase P availability for phosphorylation reactions, ATP synthesis, and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate regeneration, thereby supporting photosynthesis and vegetative growth [

48,

49,

50].

Similarly, increased K accumulation in shoots (

Figure 4d) reflects improved uptake and xylem translocation [

51]. Potassium plays a critical role in osmotic balance, cell expansion, and enzymatic activation during photosynthesis and protein synthesis [

52,

53], likely contributing to the enhanced vegetative performance observed in some varieties (

Figure 5). Microbial inoculation may have stimulated root development, expanding the soil contact surface, and enhanced microbial potassium solubilization, as reported in other crops [

54,

55,

56,

57]. Elevated P and K levels in roots under certain inoculation treatments (Figures 4b and 4e) further indicate improved ion absorption and retention capacity.

Changes in Ca and Mg contents further support the hypothesis of inoculant-induced nutritional modulation. In the ‘Orelha-de-vó’ variety, a 50% increase in shoot Ca under

A. brasilense inoculation suggests a genotype-dependent enhancement of Ca

2+ transport to aerial tissues. The 48% increase in root Mg in the same variety following

A. brasilense inoculation is particularly relevant, since magnesium acts as a cofactor for enzymes involved in nitrogen assimilation and photosynthesis; this increase may indicate improved integration of carbon-nitrogen metabolism mediated by microbial activity [

58,

59,

60].

In nodules, the substantial accumulation of macronutrients (Figures 4c, 4f, 4i, and 4l) confirms that inoculation not only enhances nodule formation (

Figure 1) but also increases the internal metabolic activity of these structures, as previously reported [

33,

61,

62]. Higher P content in nodules is crucial for ATP generation to sustain nitrogenase activity, whereas enrichment in K and Ca contributes to ionic homeostasis and structural stability of the nodules, both essential for symbiotic efficiency [

63,

64,

65].

These nutritional changes, coupled with the effects on nitrogen metabolism de-scribed in

Section 3.1, directly influenced plant growth and biomass accumulation (

Figure 5). The ‘Raio de Sol’ and ‘Manteiga’ varieties exhibited marked increases in plant height (

Figure 5a) and shoot (

Figure 5b) and root dry masses (

Figure 5c), reflecting improved nutrient acquisition and redistribution promoted by microbial activity. The positive association between N, P, and K contents and biomass reinforces the role of these macronutrients in regulating vegetative growth in the evaluated plants.

Conversely, the ‘Orelha-de-vó’ and ‘Cearense’ varieties displayed distinct and sometimes inverse responses, suggesting intrinsic differences in symbiotic compatibility and nutrient uptake. These variations indicate that inoculation efficiency depends on host genotype. In some genotypes, resource allocation may favor reproductive rather than vegetative development [

66,

67,

68], which could explain the observed patterns. Further studies including yield evaluation are necessary to verify these tendencies in lima bean.

Overall, the results demonstrate that inoculation with B. elkanii and A. brasilense significantly influences mineral nutrition in P. lunatus, enhancing macronutrient uptake and redistribution and promoting greater biomass accumulation. This response reflects the integration of increased root absorption, intensified nodular metabolism, and improved nutrient translocation within the plant.

3.3. Multivariate Analysis of Plant Traits (PCA)

The PCA (

Figure 6) integratively revealed that inoculation with

B. elkanii,

A. brasilense, and their co-inoculation promoted plant responses superior to those of non-inoculated controls, indicating greater efficiency in nutrient acquisition and redistribution. The close clustering of inoculated treatments in the biplot confirms the consistency of microbial effects identified in the univariate analyses (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), showing that all inoculation strategies improved plant nutritional performance. The projection of growth-related variables (plant height and shoot and root dry masses) on the negative side of PC1, opposite to the nutrient-related vectors, likely reflects differences in biomass allocation strategies, as discussed in

Section 3.2. This pattern suggests that enhanced nutrient-use efficiency does not necessarily translate into greater total biomass accumulation [

68,

69,

70], depending on each genotype’s physiological strategy.

The association of inoculated treatments with vectors representing mineral accumulation across plant organs reinforces that the microorganisms positively influenced nutrient assimilation, transport, and partitioning, enhancing the integration between nodular activity, root uptake, and translocation to aerial tissues [

29,

69,

70]. However, the proximity of co-inoculation treatments to single inoculations suggests that, although effective, the effects were not strictly additive. This indicates that

B. elkanii and

A. brasilense may act through overlapping mechanisms, limiting the expression of strong synergistic effects under the conditions tested.

In summary, the PCA corroborates that inoculation, either individual or combined, consistently improves mineral nutrition and growth in P. lunatus. The physiological outcomes of microbial interaction are modulated by the host’s genetic characteristics and inoculation type, highlighting the importance of considering genotype-microbe compatibility in bioinoculant design and the integrative role of the rhizosphere microbiota in optimizing nutrient assimilation and growth efficiency.

3.4. Changes in Soil Fertility Indicators

The baseline soil conditions provide essential context for interpreting the observed effects. Before cultivation, the soil exhibited a pH of 5.8, an ECe of 0.07 dS m-1, and a cation exchange capacity (CEC) of 5.04 cmolc dm-3, characterizing it as moderately acidic, low in salinity, and with limited cation exchange capacity. These properties indicate sensitivity to ionic fluctuations and microbial-induced changes throughout the experiment.

The increase in pH observed after cultivation was consistent across several treat-ments, with values rising from 5.8 to near or above 7.0 in certain cases (

Figure 7a). In the ‘Raio de Sol’ variety, co-inoculation elevated pH to 7.42, whereas in ‘Cearense’,

A. brasilense inoculation and co-inoculation produced mean pH values lower than those of the control. These results demonstrate genotype-specific and treatment-dependent shifts, consistent with evidence that rhizosphere microorganisms can modulate local H

+/OH

- balance by altering proton fluxes, organic acid secretion, and root exudation patterns, thereby influencing rhizosphere pH and ion uptake [

71,

72,

73].

The initially very low EC

e indicates that the increases observed in the soils of the control treatments across all varieties (

Figure 7b) were primarily attributable to salt inputs, likely associated with the irrigation water used during the experiment, which had an electrical conductivity (EC

w) of 0.45 dS m

-1. Despite the low EC

w, the irrigation water still contributed salts to the soil. In contrast, several inoculation treatments reduced soil EC

e relative to the control in the ‘Raio de Sol’, ‘Manteiga’, and ‘Cearense’ varieties. These reductions suggest that inoculation modulated the dynamics of soluble salts in the soil, promoting lower ionic accumulation and decreased electrical conductivity, even under initially very low salinity conditions, as reported in other studies [

74,

75,

76].

Soil P contents (

Figure 7c) exhibited distinct behaviors among treatments and va-rieties. In control soils, values remained close to the pre-cultivation level (15.13 mg dm

-3), whereas certain treatments increased P availability, particularly inoculation with

B. elkanii in the ‘Raio de Sol’ variety and all three inoculation forms in the ‘Orelha-de-vó’ variety. These increases indicate alterations in phosphorus availability within the soil-plant system associated with inoculation [

48], although the specific mechanisms cannot be determined without complementary data on mineralization, sorption, or enzymatic activity.

For soil potassium (

Figure 7d), the control showed a decrease relative to the initial value of 116.42 mg dm

-3, whereas specific inoculations promoted relative increases in available K. Increases were observed in ‘Raio de Sol’ with

B. elkanii and in ‘Orelha-de-vó’ with co-inoculation. These results suggest potential microbial mobilization or solubilization of K in the soil, consistent with reports that microorganisms can release K from poorly available minerals and increase the soluble potassium fraction in soil-plant systems [

77,

78].

Soil Ca contents (

Figure 7e) increased relative to the initial level (1.40 cmol

c dm

-3) in all treatments, including the control. However, responses to inoculation varied among varieties. The increases observed in ‘Manteiga’ and ‘Orelha-de-vó’ indicate a positive effect of specific inoculations on soil Ca availability, whereas the reductions in Ca (

Figure 7e) and Mg (

Figure 7f) recorded in ‘Cearense’ under inoculation suggest variety-specific changes in the dynamics of these ions. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these responses.

The contribution of irrigation water as a source of salts likely explains the increases in ECe, Ca, and Mg observed in the control. The low CEC and moderate organic matter content of the initial soil (10.66 g kg-1) may have amplified these ionic variations, given the limited buffering capacity of the system. Accordingly, the variations observed in P and K under inoculation can be interpreted in light of this baseline, which favors rapid adjustments in the soluble nutrient fraction.

Overall, microbial inoculation modified soil fertility indicators in a strain- and P. lunatus variety-dependent manner, starting from a moderately acidic soil with low salinity and limited buffering capacity. The integration of soil and plant variables revealed correlations between nutrient availability and plant nutritional parameters. Treatments that increased soil P and K availability generally coincided with higher nutrient contents in shoots, whereas reductions in ECe under inoculation occurred in treatments that also exhibited improved plant performance in certain varieties. These associations suggest that inoculants influenced nutrient dynamics within the soil-plant system, although the specific mechanisms cannot be fully elucidated with the current data.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Location and Experimental Conditions

The experiment was conducted in a greenhouse at the Center for Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Paraíba State University (UEPB), located in Lagoa Seca, Paraíba State, Brazil. Plants were cultivated in polyethylene pots containing 5.0 kg of medium-textured soil, which presented the following chemical characteristics prior to the experiment: pH = 5.8; ECe = 0.07 dS m-1; P, K+, and Na+ = 15.13, 116.42, and 0.13 mg dm-3, respectively; H+ + Al3+, Al3+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and CEC = 2.56, 0.15, 1.40, 0.65, and 5.04 cmolc dm-3; and organic matter = 10.66 g kg-1.

Soil was collected from a 0-20 cm depth, sieved to remove clods, roots, and other resi-dues, and placed in pots. Before sowing, soil moisture was adjusted to field capacity, and plants were irrigated manually on a daily basis using water from a reservoir (pH = 8.0, ECw = 0.45 dS m-1). The irrigation volume was adjusted daily according to plant water requirements, determined through a drainage lysimetry system.

4.2. Treatments and Plant Material

Four lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) varieties (‘Raio de Sol’, ‘Manteiga’, ‘Orelha-de-vó’, and ‘Cearense’) were evaluated under four cultivation conditions: non-inoculated control, inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense, and co-inoculation with B. elkanii and A. brasilense. The experiment followed a completely randomized design in a 4 × 4 factorial arrangement with four replicates, totaling 64 experimental units. Each experimental unit consisted of one plant.

In the control treatment, nitrogen fertilization was performed 10 days after sowing (DAS), following crop recommendations, with the application of 63.6 mg N kg

-1 of soil using ammonium sulfate as the nitrogen source, without inoculants. The seeds of the studied varieties are shown in

Figure 8, highlighting their distinguishing characteristics.

4.3. Preparation of Inoculants

The inoculants were prepared using the bacterial strains Bradyrhizobium elkanii BR 2003 and Azospirillum brasilense Ab-V5, both isolated and provided by the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa Agrobiologia, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Initially, the bacteria were cultured on YM agar plates (1% glucose, 2% agar, 0.5% peptone, 0.3% malt extract, and 0.3% yeast extract) for five days at 28 °C in a BOD-type growth chamber. Subsequently, the microorganisms were transferred to liquid Yeast Extract Malt (YEM) medium, with the same composition as the solid medium, and incubated at 28 °C under constant agitation (150 rpm) for seven days, until reaching the late exponential growth phase (1.0 × 109 CFU mL-1). The end of the growth phase was confirmed by a color change in the medium caused by bacterial metabolic activity. After preparation, the inoculants were ready for seed application.

4.4. Seed Disinfection, Inoculation, and Sowing

Before sowing, lima bean seeds were surface-sterilized by immersion in pure eth-anol for 30 seconds, followed by immersion in a 1% sodium hypochlorite solution for three minutes, and rinsed ten times with sterile distilled water. Inoculation consisted of applying 1 mL of inoculant per seed directly onto the seed surface using a micropipette, followed by covering with soil. Four seeds were sown per pot, and ten days after germination, thinning was performed to maintain one plant per pot.

4.5. Experimental Analyses

At 80 DAS, plants were evaluated for root nodule formation, nitrogen accumulation in different organs, macronutrient accumulation, growth, and biomass production. On the same day, soil samples were collected from each pot for chemical analysis.

4.5.1. Root Nodule Formation

Roots were carefully removed from the pots, washed, and nodules manually detached. Samples were dried in a forced-air oven at 65 °C until constant weight and weighed on a precision analytical balance to determine dry mass. The total number of root nodules and their dry mass were recorded.

4.5.2. Nitrogen Accumulation in Different Plant Organs

Nitrogen (N) accumulation in plant organs was determined using the Kjeldahl method, following Tedesco et al. [

79]. Plants were separated into shoots, roots, and nodules, dried at 65 °C until constant weight, and ground in a Wiley mill.

For distillation, 20 mL of the digested extract were transferred to a digestion tube connected to the distillation apparatus. In a 125 mL Erlenmeyer flask, 10 mL of boric acid solution containing indicator were added, and 10 mL of 13 N NaOH were placed in the distiller inlet cup. The distiller valve was opened gradually to mix the alkaline solution with the tube contents. Distillation was performed, and the released ammonia was absorbed in the boric acid solution until reaching approximately 50 mL. The absorbed ammonia was titrated with 0.07143 N HCl, and the endpoint was determined by a color change from green to dark pink.

Nitrogen content was calculated based on the volume of HCl consumed, determining N concentration in shoots, roots, and nodules. Additionally, ammonium (NH

4+) and nitrate (NO

3-) contents in shoots were determined according to Thomas et al. [

80] and Bremner et al. [

81].

4.5.3. Accumulation of Other Nutrients in Different Plant Organs

Phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium were determined in shoot, root, and nodules.

Phosphorus was analyzed according to Murphy and Riley [

82], potassium was measured by flame photometry [

83], and calcium and magnesium were quantified by atomic absorption spectrometry [

84].

4.5.4. Plant Growth and Biomass Accumulation

Plant growth was assessed by measuring the main stem length (plant height) from the collar to the apex using a millimeter-graduated measuring tape. Shoot and root dry masses were determined after drying in a forced-air oven at 65 °C until constant weight was achieved.

4.5.5. Soil Chemical Properties After Plant Cultivation

Soil pH, electrical conductivity of the saturated soil extract (EC

e), and the contents of P, K, Ca, and Mg were evaluated. The quantification of P, K, Ca, and Mg followed the procedures described in the

Manual of Chemical Analysis of Soils, Plants, and Fertilizers [

83].

Soil pH in water was determined according to Donagema et al. [

85], and the EC

e was measured following Silva [

83]. For this purpose, 10 g of soil were mixed with 25 mL of deionized water, stirred with a glass rod, and allowed to stabilize for 30 min. The suspension was then homogenized, after which pH was measured using a pH meter, and EC

e was determined with a bench-top conductivity meter.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Data normality was verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances was assessed with Bartlett’s test. When assumptions were satisfied, data were analyzed by factorial ANOVA (p ≤ 0.05). Mean comparisons were performed using Tukey’s HSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Principal component analysis (PCA) of plant-related variables was conducted in R version 4.5.0 using the FactoMineR package.

5. Conclusions

The results demonstrate that inoculation of Phaseolus lunatus with Bradyrhizobium elkanii (strain BR 2003) and Azospirillum brasilense (strain Ab-V5), either individually or in combination, significantly enhanced nodulation, nitrogen assimilation, and mineral nutrition, with genotype-dependent responses. The inoculation treatments improved symbiotic nitrogen fixation and promoted efficient nitrogen redistribution among plant organs, resulting in greater total nitrogen accumulation. Moreover, marked increases in other macronutrients were observed, particularly in the most responsive varieties, emphasizing the role of inoculation in enhancing nutrient-use efficiency.

Multivariate analysis clustered co-inoculation treatments together with single inoculations, indicating similar morphological and nutritional responses. The increased biomass and growth observed in the ‘Raio de Sol’ and ‘Manteiga’ varieties reinforce the potential of inoculation to stimulate vegetative development. Finally, the positive effects on soil chemical attributes after cultivation suggest additional benefits to residual fertility, indicating that inoculation contributes to improved soil quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K.G.d.C., J.F.d.B.N., E.F.d.M., and R.F.P.; methodology, G.K.G.d.C., J.A.d.S.d.S., J.F.d.B.N., C.d.S.S., S.L.B., M.G.M.S., E.F.d.M., R.S.M., R.L.d.O.C., V.V.L.d.A., W.E.P., and R.F.P.; validation, G.K.G.d.C., J.F.d.B.N., E.F.d.M., and R.F.P.; formal analysis, W.E.P. and R.F.P.; investigation, G.K.G.d.C., J.A.d.S.d.S., J.F.d.B.N., C.d.S.S., S.L.B., M.G.M.S., E.F.d.M., R.S.M., R.L.d.O.C., V.V.L.d.A., W.E.P., and R.F.P.; resources, J.F.d.B.N.; data curation, J.F.d.B.N.; writing—original draft preparation, G.K.G.d.C. and R.F.P.; writing—review and editing, J.A.d.S.d.S., J.F.d.B.N., C.d.S.S., S.L.B., M.G.M.S., E.F.d.M., R.S.M., R.L.d.O.C., V.V.L.d.A., and W.E.P.; visualization, R.F.P.; supervision, J.F.d.B.N. and R.F.P.; project administration, J.F.d.B.N.; funding acquisition, J.F.d.B.N. and E.F.d.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially funded by Paraíba State University (Grant #01/2025), Coordination of Superior Level Staff Improvement (CAPES, Finance Code 001), National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq/CT-Mineral/CT-Energ Nº 27/2022 - PD&I), and Paraíba State Research Foundation – FAPESQ (Grant #09/2023).

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available upon request from the authors. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Laboratory of Extension, Technology, and Chemistry Education (LETEQ) at the Paraíba State University (Campina Grande, Brazil) for providing access and support for the analyses. The authors also thank Dr. Jerri Édson Zilli (Embrapa Agrobiologia, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) for providing the bacterial strains used in the experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BNF |

Biological nitrogen fixation |

| PGPR |

Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria |

| IAA |

Indole-3-acetic acid |

| ABA |

Abscisic acid |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| CV |

Coefficient of variation |

| DAS |

Days after sowing |

| PCA |

Principal components analysis |

| ECe

|

Electrical conductivity of the soil saturated paste extract |

| ECw

|

Electrical conductivity of water |

| CEC |

Cation exchange capacity |

| UEPB |

Paraíba State University |

| YEM |

Yeast extract malt |

References

- Yanni, A.E.; Iakovidi, S.; Vasilikopoulou, E.; Karathanos, V.T. Legumes: A vehicle for transition to sustainability. Nutrients 2024, 16, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunas, B.; Richards, L.; Sergaki, C.; Burgess, J.; Pardal, A.J.; Hussain, R.M.F.; Richmond, B.L.; Baxter, L.; Roy, P.; Pakidi, A.; et al. Rhizobial nitrogen fixation efficiency shapes endosphere bacterial communities and Medicago truncatula host growth. Microbiome 2023, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jithesh, T.; James, E.K.; Iannetta, P.P.M.; Howard, B.; Dickin, E.; Monaghan, J.M. Recent progress and potential future directions to enhance biological nitrogen fixation in faba bean (Vicia faba L.). Plant Environ. Interact. 2024, 5, e10145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Han, T.; Liu, C.; Sun, P.; Liao, D.; Li, X. Deciphering the effects of genotype and climatic factors on the performance, active ingredients and rhizosphere soil properties of Salvia miltiorrhiza. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1110860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebo, J.A. A Review on the potential food application of lima beans (Phaseolus lunatus L.), an underutilized crop. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Municipal Agricultural Production Survey of 2024 (in portuguese). 2025. Available online: https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/pesquisa/pam/tabelas (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Costa, C.N.; Antunes, J.E.L.; de Almeida Lopes, A.C.; de Freitas, A.D.S.; Araújo, A.S.F. Inoculation of rhizobia increases lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus) yield in soils from Piauí and Ceará states, Brazil. Rev. Ceres 2020, 67, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa, J.G.C.; Sa, E.L.S.D.; Silva, F.A.D. Efficiency of rhizobia selection in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil using biological nitrogen fixation in Phaseolus lunatus. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 17, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulraheem, M.I.; Moshood, A.Y.; Li, L.; Taiwo, L.B.; Oyedele, A.O.; Ezaka, E.; Chen, H.; Farooque, A.A.; Raghavan, V.; Hu, J. Reactivating the potential of lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus) for enhancing soil quality and sustainable soil ecosystem stability. Agriculture 2024, 14, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, M.R.; Fernandes Júnior, P.I.; Gomes, D.F.; Rocha, M.M.; Araújo, A.S.F. Current knowledge and future prospects of lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus)-rhizobia symbiosis. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Agrar. UNCuyo 2019, 51, 280–288. [Google Scholar]

- Costa Neto, V.P.; Mendes, J.B.S. , Araújo, A.S.F.; Alcântara Neto, F.; Bonifacio, A.; Rodrigues, A.C. Symbiotic performance, nitrogen flux and growth of lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) varieties inoculated with different indigenous strains of rhizobia. Symbiosis 2017, 73, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.A.; Zilli, J.E.; Soares, B.L.; Barros, A.L.; Campo, R.J.; Hungria, M. Agroeconomic response of inoculated common bean as affected by nitrogen application along the growth cycle. Semina: Ciênc. Agrár. 2022, 43, 2531–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, Á.L.O.; Setubal, I.S.; Costa Neto, V.P.; Zilli, J.E.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Bonifacio, A. Synergism of Bradyrhizobium and Azospirillum baldaniorum improves growth and symbiotic performance in lima bean under salinity by positive modulations in leaf nitrogen compounds. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 180, 104603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.D.; Souza, A.J.; Nunes, A.L.P.; Rivadavea, W.R.; Zaro, G.C.; Silva, G.J. Expanding agricultural potential through biological nitrogen fixation: recent advances and diversity of diazotrophic bacteria. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2024, 18, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashan, Y.; de-Bashan, L.E. How the plant growth-promoting bacterium Azospirillum promotes plant growth—A critical assessment. Adv. Agron. 2010, 108, 77–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassán, F.; Coniglio, A.; López, G.; Molina, R.; Nievas, S.; Carlan, C.L.N.; Donadio, F.; Torres, D.; Rosas, S.; Pedrosa, F.O.; Ouza, E.; Zorita, M.D.; de-Bashan, L.; Mora, V. Everything you must know about Azospirillum and its impact on agriculture and beyond. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2020, 56, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, P.; Jin, F.; Li, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Shan, Z.; Yang, Z.; Chen, L.; Cao, D.; Hao, Q.; Guo, W.; Yang, H.; Chen, S.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, S.; Chen, H. High efficient broad-spectrum Bradyrhizobium elkanii Y63-1. Oil Crop Sci. 2023, 8, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.P.; Ratu, S.T.N.; Yasuda, M.; Teaumroong, N.; Okazaki, S. Identification of Bradyrhizobium elkanii USDA61 Type III effectors determining symbiosis with Vigna mungo. Genes 2020, 11, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.B.; Pieri, C.d.; Costa, L.J.S.; Luz, M.N.; Ganga, A.; Capra, G.F.; Passos, J.R.S.; Silva, M.R.; Guerrini, I.A. Inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii reduces nitrogen fertilization requirements for Pseudalbizzia niopoides, a multi-purpose neotropical legume tree. Nitrogen 2025, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, B.R.; Chattaraj, S.; Rath, S.; Pattnaik, M.M.; Mitra, D.; Thatoi, H. Unveiling the molecular mechanism of Azospirillum in plant growth promotion. Bacteria 2025, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.A.F.; Hungria, M.; Nogueira, M.A.; Araújo, R.S. Co-inoculation of Rhizobium tropici and Azospirillum brasilense in common beans grown under two irrigation depths. Rev. Ceres 2016, 63, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukami, J.; Cerezini, P.; Hungria, M. Co-inoculation of maize with Azospirillum brasilense and Rhizobium tropici as a strategy to mitigate salinity stress. Funct. Plant Biol. 2017, 45, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, M.; Nogueira, M.A.; Araújo, R.S. Co-inoculation of soybeans and common beans with rhizobia and azospirilla: Strategies to improve sustainability. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2013, 49, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, É.R.; Marinho, R.C.N.; Silva, J.S.; Teixeira, M.C.C.; Sousa, L.B.; Silva, A.F. Combined inoculation of rhizobia on the cowpea development in the soil of Cerrado. Rev. Ciênc. Agron. 2017, 48, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, G.C.; Silva, A.S.; Oliveira, J.P.; Moreira, F.M.S. Effects of associated co-inoculation of Bradyrhizobium japonicum with Azospirillum brasilense on soybean yield and growth. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 12, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeffa, D.M.; Perini, L.J.; Silva, M.B.; de Sousa, N.V.; Scapim, C.A.; Oliveira, A.L.M.; Amaral Júnior, A.T.D.; Gonçalves, L.S.A. Azospirillum brasilense promotes increases in growth and nitrogen use efficiency of maize genotypes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pii, Y.; Aldrighetti, A.; Valentinuzzi, F.; Mimmo, T.; Cesco, S. Azospirillum brasilense inoculation counter-acts the induction of nitrate uptake in maize plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 1313–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheteiwy, M.S.; Ali, D.F.I.; Xiong, Y.C.; Brestic, M.; Skalicky, M.; Hamoud, Y.A.; Ulhassan, Z.; Shagaleh, H.; AbdElgawad, H.; Farooq, M.; Sharma, H.; El-Sawah, A.M. Physiological and biochemical responses of soybean plants inoculated with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Bradyrhizobium under drought stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galindo, F.S.; Pagliari, P.H.; Silva, E.C.; Silva, V.M.; Fernandes, G.C.; Rodrigues, W.L.; Céu, E.G.O.; Lima, B.H.; Jalal, A.; Muraoka, T.; buzetti, S.; Lavres, J.; Teixeira Filho, M.C.M. Co-inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense and Bradyrhizobium sp. enhances nitrogen uptake and yield in field-grown cowpea and did not change N-fertilizer recovery. Plants 2022, 11, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, C.H.Q.; Cardoso, F.B.; Cândido, A.C.S.; Teodoro, P.E.; Alves, C.Z. Co-inoculation with Bradyrhizobium and Azospirillum increases yield and quality of soybean seeds. Agronomy J. 2018, 110, 2302–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrig, D.; Boiero, M.L.; Masciarelli, O.A.; Penna, C.; Ruiz, O.A.; Cassán, F.D.; Luna, M.V. Plant-growth-promoting compounds produced by two agronomically important strains of Azospirillum brasilense, and implications for inoculant formulation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 75, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fibach-Paldi, S.; Burdman, S.; Okon, Y. Key physiological properties contributing to rhizosphere adaptation and plant growth promotion abilities of Azospirillum brasilense. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012, 326, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xiao, C.; Liu, J.; Ren, G. Nutrient-dependent regulation of symbiotic nitrogen fixation in legumes. Hortic. Res. 2024, 12, uhae321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habinshuti, S.J.; Maseko, S.T.; Dakora, F.D. Inhibition of N₂ fixation by N fertilization of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants grown on fields of farmers in the Eastern Cape of South Africa, measured using ¹⁵N natural abundance and tissue ureide analysis. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 692933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; Sun, R.; Wang, Z.; et al. Legume rhizodeposition promotes nitrogen fixation by soil microbiota under crop diversification. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmat, Z.; Sohail, M.N.; Perrine-Walker, F.; Kaiser, B.N. Balancing nitrate acquisition strategies in symbiotic legumes. Planta 2023, 258, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min-Yao Jhu; Raphael Ledermann. Division of labor in the nodule: Plant GluTRs fuel heme biosynthesis for symbiosis. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koaf156. [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.G.; Chen, Q.S. Molecular mechanisms of nitrogen-fixing symbiosis in Fabaceae. Legume Genom. Genet. 2024, 15, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervent, M.; Lambert, I.; Tauzin, M.; Karouani, A.; Nigg, M.; Jardinaud, M.-F.; Severac, D.; Colella, S.; Martin-Magniette, M.-L.; Lepetit, M. Systemic control of nodule formation by plant nitrogen demand requires autoregulation-dependent and independent mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 7942–7956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, C.; Liu, H.; Lyu, X.; Xiao, F.; Zhao, S.; Ma, C.; Yan, C.; Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Gong, Z. Systemic regulation of nodule structure and assimilated carbon distribution by nitrate in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1101074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, F.; Lu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Fu, M.; Mysore, K.S.; Wen, J.; Gong, J.; Murray, J.D. Xie, F. The small peptide CEP1 and the NIN-like protein NLP1 regulate NRT2.1 to mediate root nodule formation across nitrate concentrations. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 776–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zancarini, A.; Le Signor, C.; Terrat, S.; Aubert, J.; Salon, C.; Munier-Jolain, N.; Mougel, C. Medicago truncatula genotype drives the plant nutritional strategy and its associated rhizosphere bacterial communities. New Phytol. 2025, 245, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, J.; Gerin, F.; Mini, A.; Richard, R.; Le Gouis, J.; Prigent-Combaret, C.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y. Symbiotic variations among wheat genotypes and detection of quantitative trait loci for molecular interaction with auxin-producing Azospirillum PGPR. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Perez-Limón, S.; Ramírez-Flores, M.R.; Barrales-Gamez, B.; Meraz-Mercado, M.A.; Ziegler, G.; Baxter, I.; Olalde-Portugal, V.; Sawers, R.J.H. Mycorrhizal status and host genotype interact to shape plant nutrition in field grown maize (Zea mays ssp. mays). Mycorrhiza 2023, 33, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.I.; Pereira, M.C.; Carvalho, A.M.X.; Buttrós, V.H.; Pasqual, M.; Dória, J. Phosphorus-solubilizing microorganisms: A key to sustainable agriculture. Agriculture 2023, 13, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Cai, B. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria: advances in their physiology, molecular mechanisms and microbial community effects. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xing, Y.; Li, Y.; Jia, J.; Ying, Y.; Shi, W. The role of phosphate-solubilizing microbial interactions in phosphorus activation and utilization in plant–soil systems: A review. Plants 2024, 13, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Siddique, A.B.; Shabala, S.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, C. Phosphorus plays key roles in regulating plants’ physiological responses to abiotic stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, P.M.; Herdean, A.; Adolfsson, L.; Beebo, A.; Nziengui, H.; Irigoyen, S.; Ünnep, R.; Zsiros, O.; Nagy, G.; Garab, G.; Aronsson, H.; Versaw, W.K.; Spetea, C. The Arabidopsis thylakoid transporter PHT4; 1 influences phosphate availability for ATP synthesis and plant growth. Plant J. 2015, 84, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Ye, X.; Song, Y.; Ren, T.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Cong, R.; Lu, Z.; Lu, J. Sufficient potassium improves inorganic phosphate-limited photosynthesis in Brassica napus by enhancing metabolic phosphorus fractions and Rubisco activity. Plant J. 2023, 113, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, M.; Tang, R.-J.; Tang, Y.; Tian, W.; Hou, C.; Zhao, F.; Lan, W.; Luan, S. Transport and homeostasis of potassium and phosphate: Limiting factors for sustainable crop production. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 3091–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Vishwakarma, K.; Hossen, M.S.; Kumar, V.; Shackira, A.M.; Puthur, J.T.; Abdi, G.; Sarraf, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Potassium in plants: Growth regulation, signaling, and environmental stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 172, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.A.; Kaniganti, S.; Kumari, P.H.; Reddy, P.S.; Suravajhala, P.; Suprasanna, P.; Kishor, P.B.K. Functional and biotechnological cues of potassium homeostasis for stress tolerance and plant development. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2024, 40, 3527–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S.K.; Srivastava, A.K.; Rajput, V.D.; Chauhan, P.K.; Bhojiya, A.A.; Jain, D.; Chaubey, G.; Dwivedi, P.; Sharma, B.; Minkina, T. Root exudates: Mechanistic insight of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for sustainable crop production. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 916488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liang, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Dhital, Y.P.; Zhao, T.; Wang, Z. Isolation and characterization of potassium-solubilizing rhizobacteria (KSR) promoting cotton growth in saline-sodic regions. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawaz, A.; Qamar, Z.U.; Marghoob, M.U.; Imtiaz, M.; Imran, A.; Mubeen, F. Contribution of potassium solubilizing bacteria in improved potassium assimilation and cytosolic K⁺/Na⁺ ratio in rice (Oryza sativa L.) under saline-sodic conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1196024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khani, A.G.; Enayatizamir, N.; Masir, M.N. Impact of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on different forms of soil potassium under wheat cultivation. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.T.; Qi, W.L.; Nie, M.M.; Xiao,Y.B.; Liao, H.; Chen, Z.C. Magnesium supports nitrogen uptake through regulating NRT2.1/2.2 in soybean. Plant Soil 2020, 457, 97–111. [CrossRef]

- Tränkner, M.; Tavakol, E.; Jákli, B. Functioning of potassium and magnesium in photosynthesis, photosynthate translocation and photoprotection. Physiol. Plant. 2018, 2018 Apr 18. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Zhang, B.; Bozdar, B.; Chachar, S.; Rai, M.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Hayat, F.; Chachar, Z.; Tu, P. The power of magnesium: Unlocking the potential for increased yield, quality, and stress tolerance of horticultural crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1285512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prell, J.; Poole, P. Metabolic changes of rhizobia in legume nodules. Trends Microbiol. 2006, 14, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindstrom, K.; Mousavi, S.A. Effectiveness of nitrogen fixation in rhizobia. Microb. Biotechnol. 2020, 13, 1314–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.G.; Chen, Q.S. Molecular mechanisms of nitrogen-fixing symbiosis in Fabaceae. Legume Genom. Genet. 2024, 15, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulieman, S.; Tran, L.S. Phosphorus homeostasis in legume nodules as an adaptive strategy to phosphorus deficiency. Plant Sci. 2015, 239, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zartdinova, R.; Nikitin, A. Calcium in the life cycle of legume root nodules. Indian J. Microbiol. 2023, 63, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenk, E.H.; Falster, D.S. Quantifying and understanding reproductive allocation schedules in plants. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 5521–5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.E.; Ewers, B.E.; Weinig, C. Genotypic variation in biomass allocation in response to field drought has a greater affect on yield than gas exchange or phenology. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Zhao, W.; Xing, M.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, Z.; You, J.; Ni, B.; Ni, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, J.; Chen, X. Resource allocation strategies among vegetative growth, sexual reproduction, asexual reproduction and defense during growing season of Aconitum kusnezoffii Reichb. Plant J. 2021, 105, 957–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepetit, M. , Brouquisse, R. Control of the rhizobium–legume symbiosis by the plant nitrogen demand is tightly integrated at the whole plant level and requires inter-organ systemic signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1114840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, D.X.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Xu, A. , Jiang, Y.L.; Chen, Z.C. Metal nutrition and transport in the process of symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thepbandit, W.; Athinuwat, D. Rhizosphere microorganisms supply availability of soil nutrients and induce plant defense. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Tang, C. The role of rhizosphere pH in regulating the rhizosphere priming effect and implications for the availability of soil-derived nitrogen to plants, Ann. Bot. 2018, 121, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wankhade, A.; Wilkinson, E.; Britt, D.W.; Kaundal, A. A review of plant–microbe interactions in the rhizosphere and the role of root exudates in microbiome engineering. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, S.; Cherif-Silini, H.; Chenari Bouket, A.; Silini, A.; Eshelli, M.; Luptakova, L.; Alenezi, F.N.; Belbahri, L. . Improvement of Medicago sativa crops productivity by the co-inoculation of Sinorhizobium meliloti-actinobacteria under salt stress. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 1344–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.; Daur, I.; Yasir, M.; Waqas, M.; Hirt, H. Synergistic practicing of rhizobacteria and silicon improve salt tolerance: implications from boosted oxidative metabolism, nutrient uptake, growth and grain yield in mung bean. Plants 2022, 11, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Gao, T.; Wang, X.; Chen, R.; Gao, H.; Liu, H. Co-inoculation of Bacillus subtilis and Bradyrhizobium liaoningense increased soybean yield and improved soil bacterial community composition in coastal saline-alkali land. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1677763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, N.; Singh, S.; Saxena, G.; Pradhan, N.; Koul, M.; Kharkwal, A. C.; Sayyed, R. A review on microbe-mineral transformations and their impact on plant growth. Front. Microbiol., 2025, 16, 1549022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, F.T.; Alori, E.T.; Adekiya; A.O.; Ayorinde, B.B.; Daramola, F.Y.; Osemwegie, O.O.; Babalola, O.O. The use of soil microbial potassium solubilizers in potassium nutrient availability in soil and its dynamics. Ann. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 45. [CrossRef]

- edesco, M.J.; Gianello, C.; Bissani, C.A.; Bohnem, H.; Volkweiss, S. Analysis of soil, plants and other materials; Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1995. (in portuguese).

- Thomas, R.L.; Sheard, R.W.; Moyer, J.R. Comparison of conventional and automated procedures for nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium analysis of plant material using a single digestion. Agron. J. 1967, 59, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M.; Keeney, D.R. Determination and isotope-ratio analysis of different forms of nitrogen in soils: 3. Exchangeable ammonium, nitrate, and nitrite by extraction-distillation methods. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1966, 30, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.C. Manual of chemical analyses of soils, plants, and fertilizers, 2nd ed.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2009. (in portuguese).

- Guimarães, G.A.; Bastos, J.B.; Lopes, E.C. Methods of physical, chemical, and instrumental analysis of soils; IPEAN: Belém, Brazil, 1970. (in portuguese).

- Donagema, G.K.; Campos, D.V.B.; Calderano, S.B.; Teixeira, W.G.; Viana, J.H.M. Manual of Soil Analysis Methods, 2nd ed.; Embrapa: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2011. (in portuguese).

Figure 1.

Number of nodules (a) and nodule dry mass (b) of four Phaseolus lunatus varieties subjected to the following treatments: control (fertilization with nitrogen), inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense, and co-inoculation (B. elkanii + A. brasilense). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among inoculation treatments within each variety, and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among varieties within each inoculation, according to Tukey’s HSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 4). CV: coefficient of variation.

Figure 1.

Number of nodules (a) and nodule dry mass (b) of four Phaseolus lunatus varieties subjected to the following treatments: control (fertilization with nitrogen), inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense, and co-inoculation (B. elkanii + A. brasilense). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among inoculation treatments within each variety, and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among varieties within each inoculation, according to Tukey’s HSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 4). CV: coefficient of variation.

Figure 2.

Representative photographs of Phaseolus lunatus (‘Raio de Sol’ variety) roots at 80 days after sowing (DAS) under non-inoculated control (a) and inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii (b).

Figure 2.

Representative photographs of Phaseolus lunatus (‘Raio de Sol’ variety) roots at 80 days after sowing (DAS) under non-inoculated control (a) and inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii (b).

Figure 3.

Nitrogen contents in shoots (a), roots (b), and nodules (c), and NH4+ (d) and NO3− (e) in shoots of four Phaseolus lunatus varieties subjected to the following treatments: control (fertilization with nitrogen), inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense, and co-inoculation (B. elkanii + A. brasilense). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among inoculation treatments within each variety, and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among varieties within each inoculation, according to Tukey’s HSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 4). CV: coefficient of variation.

Figure 3.

Nitrogen contents in shoots (a), roots (b), and nodules (c), and NH4+ (d) and NO3− (e) in shoots of four Phaseolus lunatus varieties subjected to the following treatments: control (fertilization with nitrogen), inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense, and co-inoculation (B. elkanii + A. brasilense). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among inoculation treatments within each variety, and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among varieties within each inoculation, according to Tukey’s HSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 4). CV: coefficient of variation.

Figure 4.

Phosphorus contents in shoots (a), roots (b), and nodules (c); potassium contents in shoots (d), roots (e), and nodules (f); calcium contents in shoots (g), roots (h), and nodules (i); and magnesium contents in shoots (j), roots (k), and nodules (l) of four Phaseolus lunatus varieties subjected to the following treatments: control (fertilization with nitrogen), inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense, and co-inoculation (B. elkanii + A. brasilense). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among inoculation treatments within each variety, and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among varieties within each inoculation, according to Tukey’s HSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 4). CV: coefficient of variation.

Figure 4.

Phosphorus contents in shoots (a), roots (b), and nodules (c); potassium contents in shoots (d), roots (e), and nodules (f); calcium contents in shoots (g), roots (h), and nodules (i); and magnesium contents in shoots (j), roots (k), and nodules (l) of four Phaseolus lunatus varieties subjected to the following treatments: control (fertilization with nitrogen), inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense, and co-inoculation (B. elkanii + A. brasilense). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among inoculation treatments within each variety, and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among varieties within each inoculation, according to Tukey’s HSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 4). CV: coefficient of variation.

Figure 5.

Plant height (a), shoot dry mass (b), and root dry mass (c) in four Phaseolus lunatus varieties subjected to the following treatments: control (fertilization with nitrogen), inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense, and co-inoculation (B. elkanii + A. brasilense). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among inoculation treatments within each variety, and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among varieties within each inoculation, according to Tukey’s HSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 4). CV: coefficient of variation.

Figure 5.

Plant height (a), shoot dry mass (b), and root dry mass (c) in four Phaseolus lunatus varieties subjected to the following treatments: control (fertilization with nitrogen), inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense, and co-inoculation (B. elkanii + A. brasilense). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among inoculation treatments within each variety, and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among varieties within each inoculation, according to Tukey’s HSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 4). CV: coefficient of variation.

Figure 6.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of nitrogen metabolism, nutritional, and growth variables in four Phaseolus lunatus varieties subjected to inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, Azospirillum brasilense, their co-inoculation, and a nitrogen-fertilized control. Colors represent distinct groups formed according to treatment responses (green = Group 1; blue = Group 2; red = Group 3). Treatment identification: green group – 4 (‘Cearense’, Control), 8 (‘Manteiga’, Control), 12 (‘Orelha-de-vó’, Control), and 16 (‘Raio de Sol’, Control); blue group – 9 (‘Orelha-de-vó’, A. brasilense), 10 (‘Orelha-de-vó’, B. elkanii), 14 (‘Raio de Sol’, B. elkanii), and 15 (‘Raio de Sol’, co-inoculation); red group – 1 (‘Cearense’, A. brasilense), 2 (‘Cearense’, B. elkanii), 3 (‘Cearense’, co-inoculation), 5 (‘Manteiga’, A. brasilense), 6 (‘Manteiga’, B. elkanii), 7 (‘Manteiga’, co-inoculation), 11 (‘Orelha-de-vó’, co-inoculation), and 13 (‘Raio de Sol’, A. brasilense).

Figure 6.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of nitrogen metabolism, nutritional, and growth variables in four Phaseolus lunatus varieties subjected to inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, Azospirillum brasilense, their co-inoculation, and a nitrogen-fertilized control. Colors represent distinct groups formed according to treatment responses (green = Group 1; blue = Group 2; red = Group 3). Treatment identification: green group – 4 (‘Cearense’, Control), 8 (‘Manteiga’, Control), 12 (‘Orelha-de-vó’, Control), and 16 (‘Raio de Sol’, Control); blue group – 9 (‘Orelha-de-vó’, A. brasilense), 10 (‘Orelha-de-vó’, B. elkanii), 14 (‘Raio de Sol’, B. elkanii), and 15 (‘Raio de Sol’, co-inoculation); red group – 1 (‘Cearense’, A. brasilense), 2 (‘Cearense’, B. elkanii), 3 (‘Cearense’, co-inoculation), 5 (‘Manteiga’, A. brasilense), 6 (‘Manteiga’, B. elkanii), 7 (‘Manteiga’, co-inoculation), 11 (‘Orelha-de-vó’, co-inoculation), and 13 (‘Raio de Sol’, A. brasilense).

Figure 7.

Soil pH (a), electrical conductivity of the saturated paste extract (ECe) (b), phosphorus (c), potassium (d), calcium (e), and magnesium (f) contents in soil after cultivation with four Phaseolus lunatus varieties subjected to the following treatments: control (fertilization with nitrogen), inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense, and co-inoculation (B. elkanii + A. brasilense). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among inoculation treatments within each variety, and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among varieties within each inoculation, according to Tukey’s HSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 4). CV: coefficient of variation.

Figure 7.

Soil pH (a), electrical conductivity of the saturated paste extract (ECe) (b), phosphorus (c), potassium (d), calcium (e), and magnesium (f) contents in soil after cultivation with four Phaseolus lunatus varieties subjected to the following treatments: control (fertilization with nitrogen), inoculation with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense, and co-inoculation (B. elkanii + A. brasilense). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among inoculation treatments within each variety, and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among varieties within each inoculation, according to Tukey’s HSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 4). CV: coefficient of variation.

Figure 8.

Seeds of the four lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus) varieties used in the experiment, showing distinguishing features: ‘Raio de Sol’ (a), ‘Manteiga’ (b), ‘Orelha-de-vó’ (c), and ‘Cearense’ (d).

Figure 8.

Seeds of the four lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus) varieties used in the experiment, showing distinguishing features: ‘Raio de Sol’ (a), ‘Manteiga’ (b), ‘Orelha-de-vó’ (c), and ‘Cearense’ (d).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).