Submitted:

22 October 2023

Posted:

23 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study area description

2.2. Origin and characterization of organic waste

2.3. Formulation of the organomineral fertilizer

2.4. Experimental design and treatments

2.5. Experimental unit and crop treatments

2.6. Development analysis

2.7. Analysis of yield and its components

2.8. Statistical analysis

3. Results and Discussion

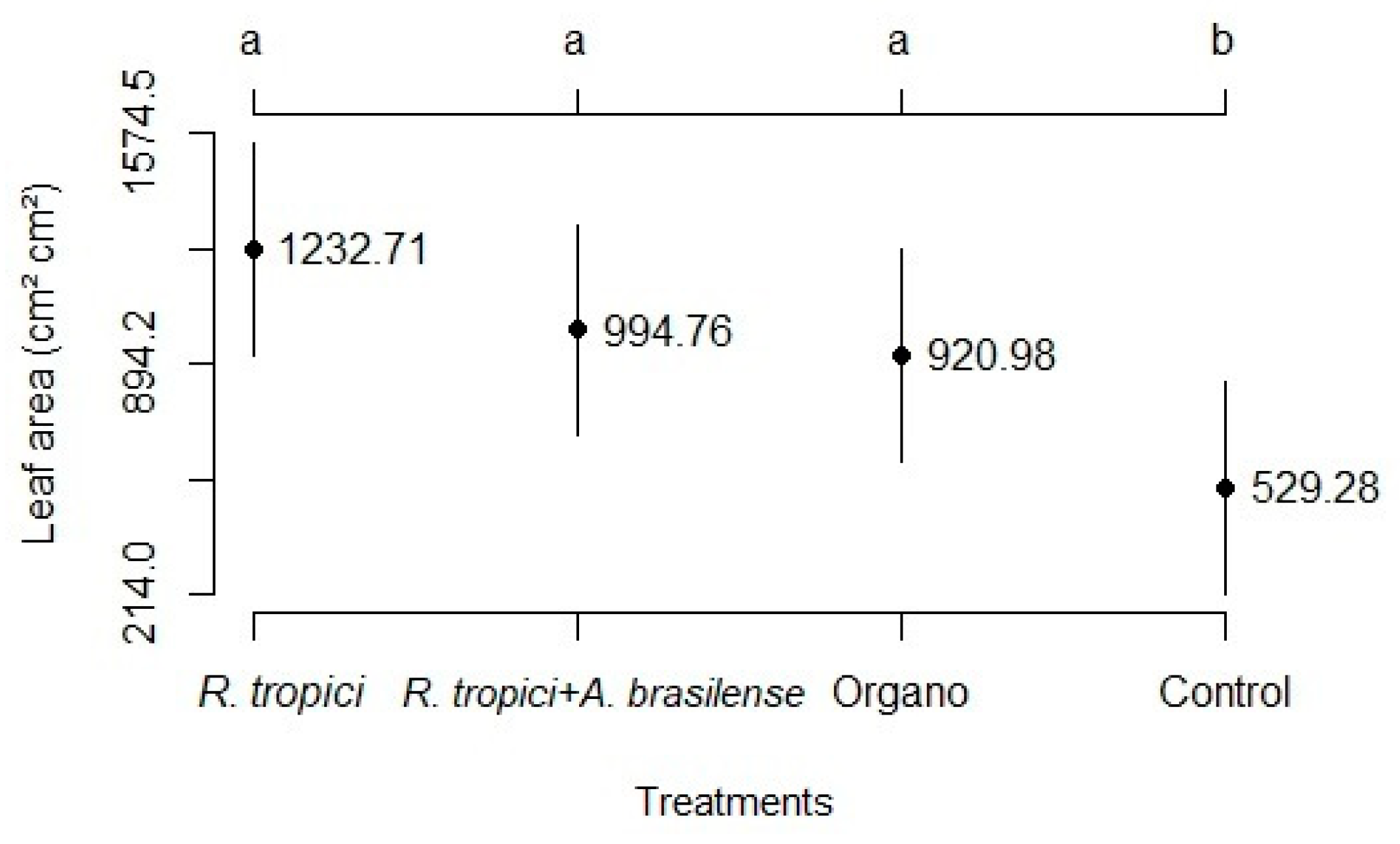

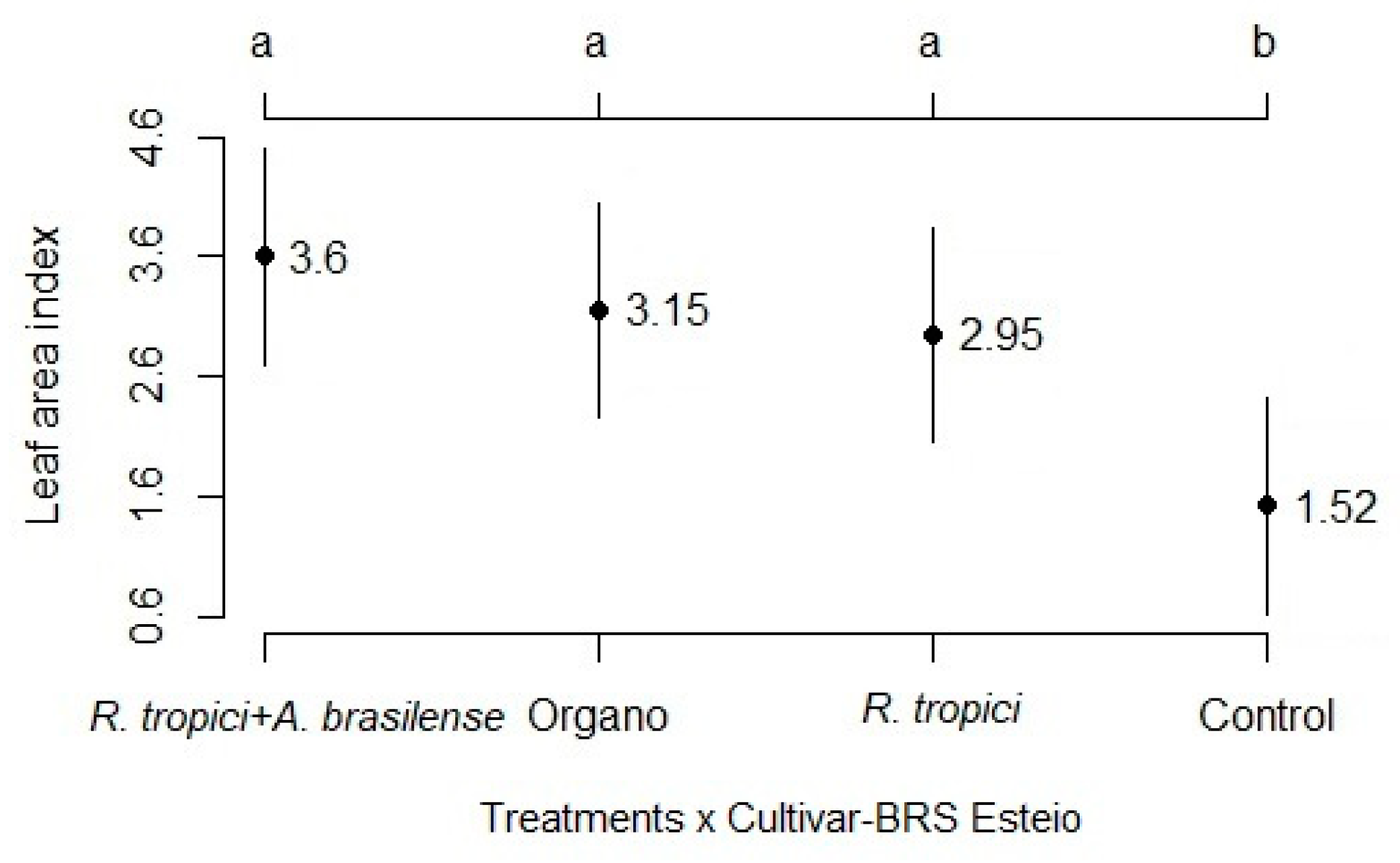

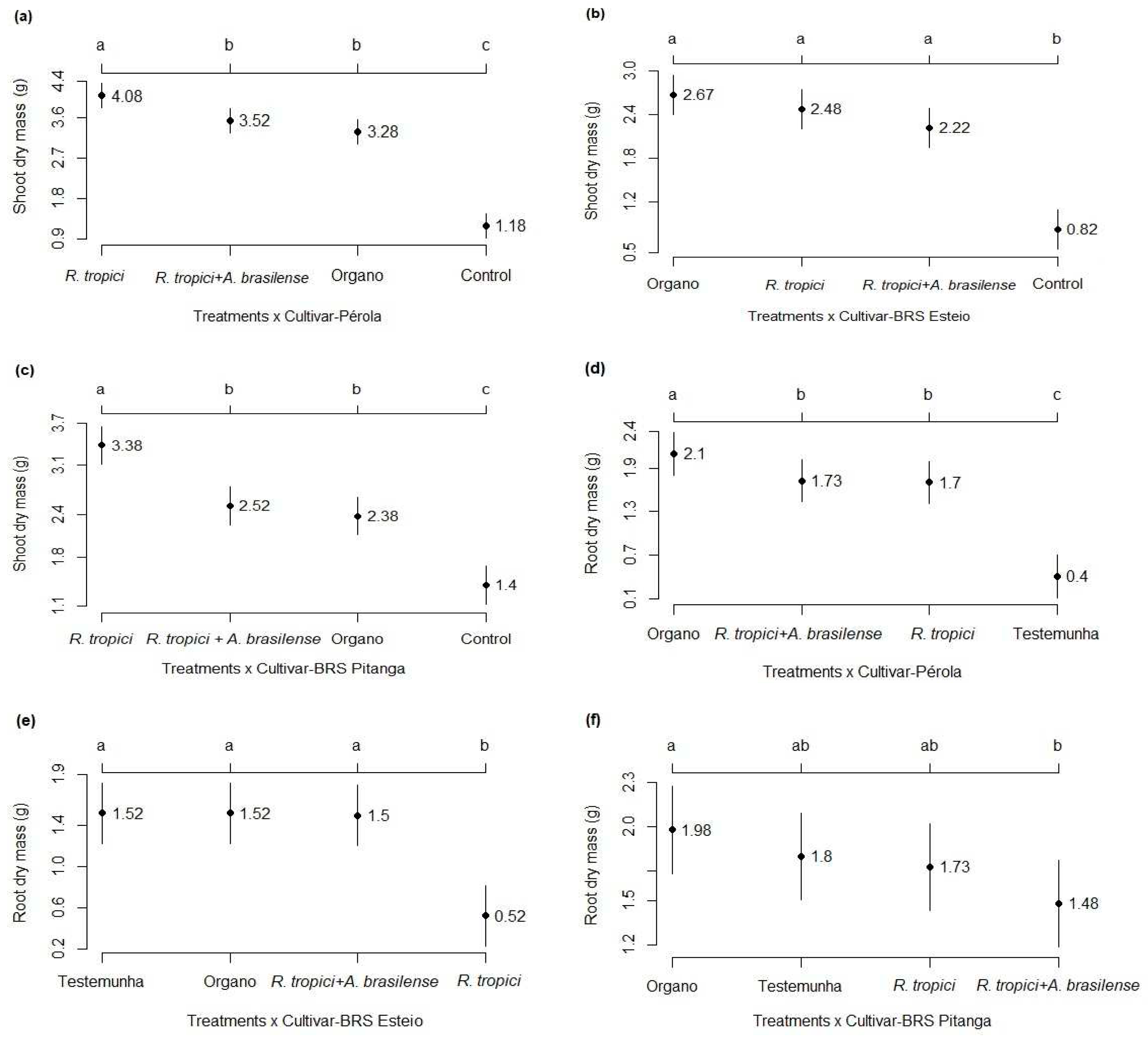

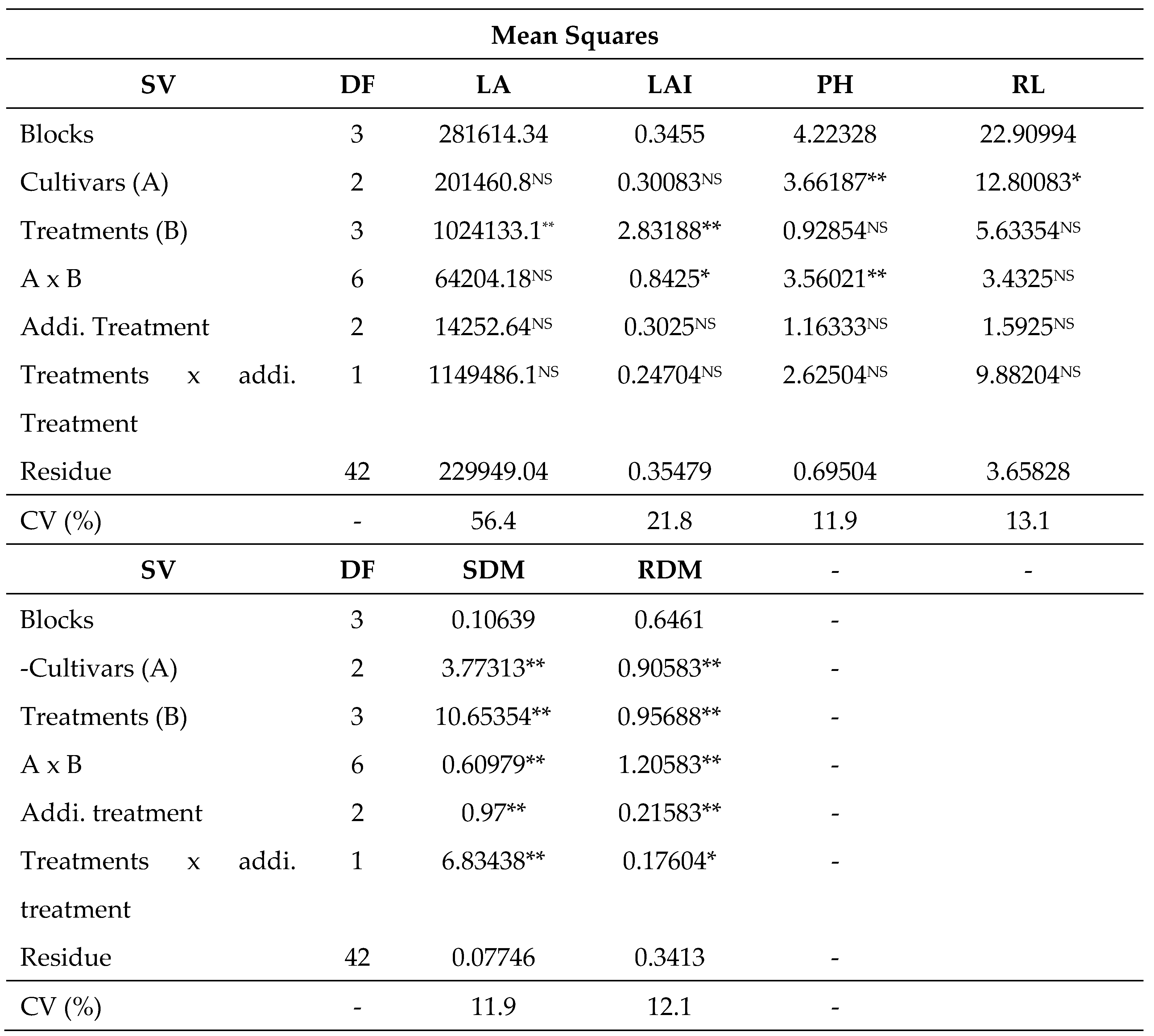

3.1. Development analysis

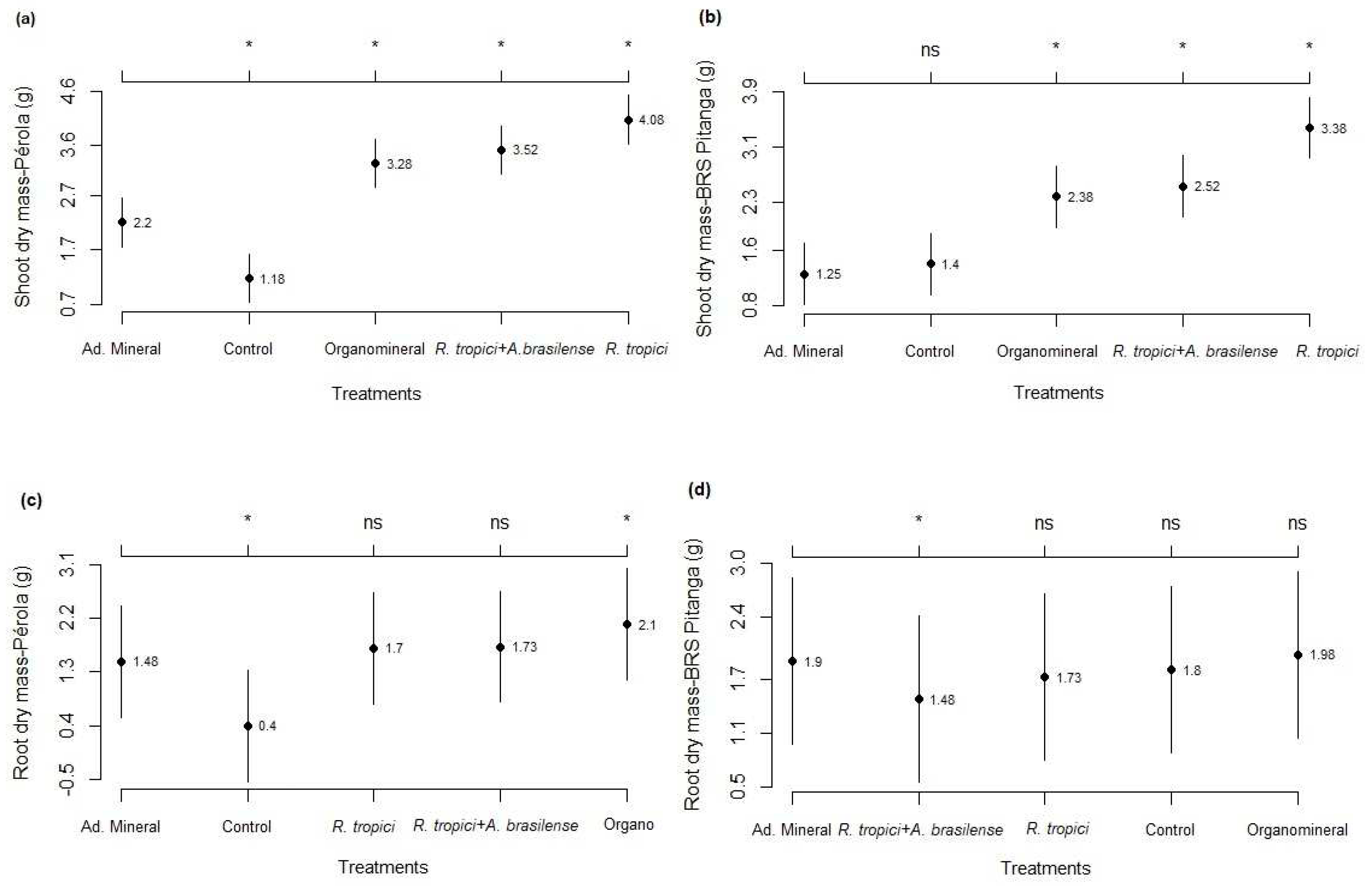

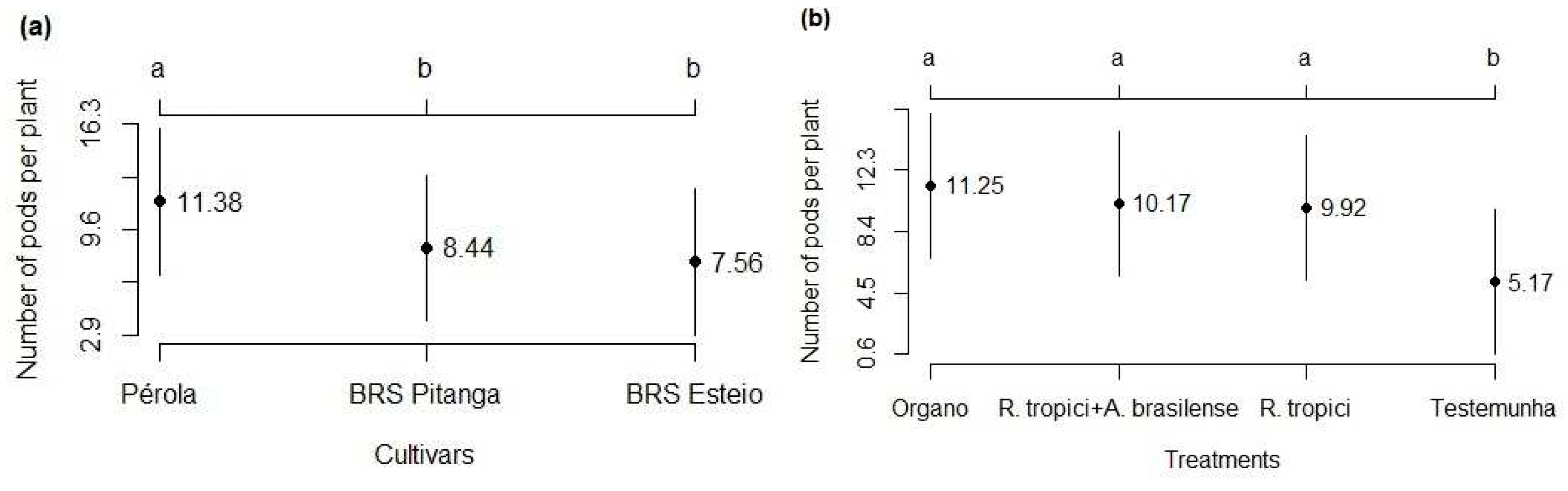

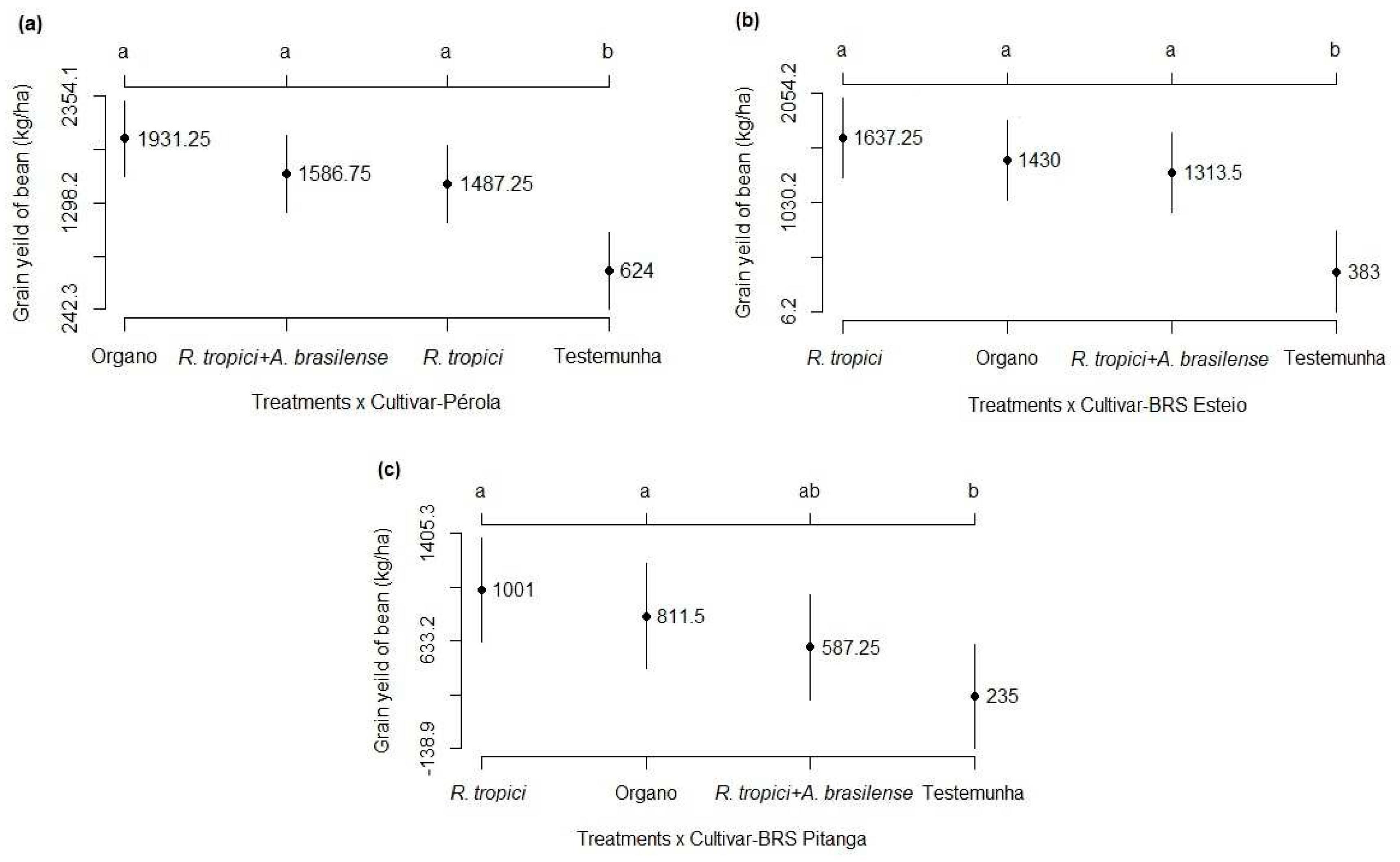

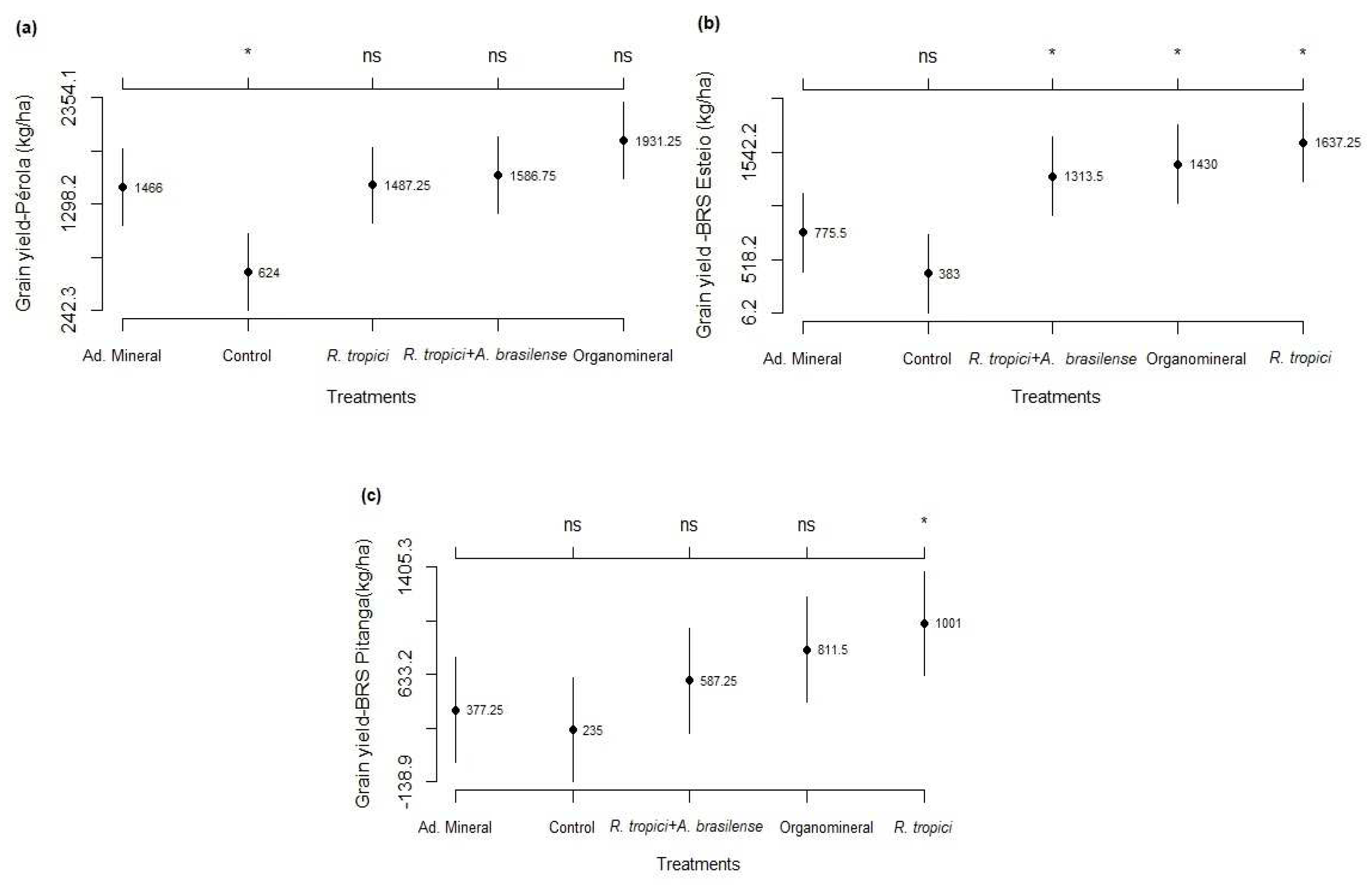

3.2. Components and grain yield

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Menegat, S.; Ledo, A.; Tirado, R. Greenhouse gas emissions from global production and use of nitrogen synthetic fertilisers in agriculture. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kominko, H.; Gorazda, k.; Wzorek, Z.; Wojtas, K. Sustainable management of sewage sludge for the production of organo-mineral fertilizers. Waste and biom. valor. 2018, 9, 1817–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumare, A.; Diedhiou, A.G.; Thuita, M.; Hafidi, M.; Ouhdouch, Y.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Kouisni, L. Exploiting biological nitrogen fixation: a route towards a sustainable agriculture. Plants 2020, 9, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullio, L.D.; Nakatani, A.S.; Gomes, D.F.; Ollero, F.J.; Megias, M.; Hungria, M. Revealingthe roles of y4wF andtidC genes in Rhizobiumtropici CIAT 899: biosynthesisofindole compoundsandimpactonsymbioticproperties. Arch. Micro. 2019, 201, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, M.; Vargas, M.A.T. Environmental factors affecting N2 fixation in grain legumes in the tropics, with an emphasis on Brazil. Field Crops Res. 2000, 65, 151–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, M.; Campo, R.J.; Mendes, I.C. A importância do processo de fixaçãobiológica do nitrogênio para a cultura da soja: componenteessencial para a competitividade do produtobrasileiro, 1st ed.; Embrapa Soja: Londrina, B rasil, 2007; pp. 9–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, W.S.; Teixeira, I.R.; Campos, T.S.; Silva, G.C.; Silva, M.B.; Moreira, S.G. Supplementaryreinoculation in top dressingof in common beancrop: effectsonnodulation, morphology, andgrain yield. Journal of Plant Nutrition 2021, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, F.; Ferreira, H.C. P.; Zuffo, A. M. Canco-inoculationofRhizobiumtropiciandAzospirillumbrasilensein crease common beannodulationandgrainyield? Semina Ciênc. Agrár 2019, 40, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.E.B.; Ferreira, E.P.B. Improving sustainability of common bean production systems by co-inoculating rhizobia and azospirilla. Agric. Ecos. and Environ. 2017, 237, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, A. R.; Rodrigues, R.A.F.; ARF, O.; Portugal, J.R.; Corsini, D.C.D.C. Co-inoculationofRhizobiumtropiciandAzospirillumbrasilense in common beansgrownundertwoirrigationdepths. Revista Ceres. 2016, 63, 198–207. [Google Scholar]

- Google Earth. Google Earth Pro. Accessed on: June 11, 2021. 11 June.

- Moraes, E.R. Aplicação de Fertilizanteorganomineral de lodo de esgoto e bioestimulantenacana-de-açúcar. 2017. 84p. Dissertation (Doctorate in Agronomy) – Federal University of Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, 2017.

- Borges, B.M.M.N.; et al. Methods of determination dry matter and macronutrient content in lettuce leaves. Revista Trópica 2011, 5, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel-Gomes, F. Curso de estatística experimental, 13rd ed.; Piracicaba: Nobel, 1990; 468p. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, L.P.; Oliveira, A.P.S.; de Brito Ferreira, E.P. Nodulation, contributionofbiological N2 fixation, andproductivityofthe common bean (PhaseolusvulgarisL.) inoculatedwithrhizobiasolates. Austr. J. Crop Science 2017, 11, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, P. Rhizospherebiology. In Marschner's mineral nutrition o fighterplants, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Australia, 2011; pp. 369–388. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, R.L.N.; Oliveira, L.B.; Magalhães, W.B.; Pimentel, C. Growthanyieldof common bean as affectedbyseedinoculationwithrhizobiumandnitrogenfertilization. Exper. Agric. 2016, 54, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.C.; Lima, L.C.; Camargo, R.; Lana, R.M.Q.; Lemes, E.M.; Cardoso, A.F. Effectsoforganomineralfertilizersformulatedwithbiosolidsandfiltercakeon common beanyieldcrop (Phaseolusvulgaris L.). Aust. J. Crop Science 2019, 13, 1566–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.A.L.; Neves, J.A. Componentes de produção e suascorrelaçõesemgenótipos de feijão-caupiemcultivo de sequeiro e irrigado. Revista Ciênc. Agro 2011, 42, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.A.; Karaköy, T.; Yeken, M.Z.; Habyarimana, E.; Hatipoğlu, R.; Çiftçi, V.; Nawaz, M.A.; Sönmez, F.; Shahid, M.Q.; Yang, S.H.; Chung, G.; Baloch, F.S. Phenotypic characterization of 183 Turkish common bean accessions for agronomic, trading, and consumer-preferred plant characteristics for breeding purposes. Agronomy 2020, 10, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero, V.O.; Carvalho, R.H.; Leite, A.B.C.; Santos, D.M.T.; Freitas, K.M.; Boddey, R.M.; Xavier, G.R.; Rumjanek, N.G.; Urquiaga, S. Bradyrhizobium strains from Brazilian tropical soils promote increases in nodulation, growth and nitrogen fixation in mung bean. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 175, 104461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIORI, A.K.; Gutuzzo, G.O.; Sanzovo, A.W.S.; Andrade, D.S.; Oliveira, A.L.M.; Rodrigues, E.P. Effects of Rhizobium tropiciazide-resistant mutants on growth, nitrogen nutrition and nodulation of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Rhizosphere 2021, 18, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.P.S.; Sousa, C.M.; Ferreira, E.P.D.B. Performance of inoculated common bean in response to different cover crops and desiccation times. Revista Caatinga 2017, 30, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SÁ, G.C.R.; Carvalho, C.L.M.; Hungria, M.A.; Nogueira, M.A.; Heinrichs, R.; Soares Filho, C.V. Biomass yield, nitrogen accumulation and nutritive value of Mavuno grass inoculated with plant growth-promoting bacteria. Commu. in Soil Sci. and Plant Analy. 2019, 50, 1931–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.P.; Silva, A.B.; Santi, A.; Magalhães, M.O.L.; Silva, G.B. Produção de mudas de alfaceemsubtrato sob doses de fertilizanteorganomineral. Enciclopédia Biosfera 2019, 16, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipini, L.D.; Pilatti, F.K.; Meyer, E.; Ventura, B.S.; Lourenzi, C.R.; Lovato, P.E. Application of Azospirillum on seeds and leaves, associated with Rhizobium inoculation, increases growth and yield of common bean. Arch. Microb. 2021, 203, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, J.E.B.; De Brito, E.P.F. Improving sustainability of common bean production systems by co-inoculating rhizobia and azospirilla. Agric. Ecos. Envir. 2017, 237, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MUMBACH, Gilmar L. et al. Agronomic efficiency of organomineral fertilizer in sequential grain crops in southern Brazil. Agronomy Journal 2020, 112, 3037–3049. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.K.F.; Cabral Filho, F.R.; Bastos, A.V.S.; Cunha, F.N.; Teixeira, M.B.; Silva, E.C.; Santos, E.A.; Vidal, V.M.; Morais, W.A.; Avila, R.G.; et al. Acúmulo de material seca e nutrients pelomilhocultivado sob doses de formulados NPK mineral e organomineral. Research Society and Development 2021, 10, e35010515126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, C.K.R.; Reis, J.N.; Brigante, G.P.; Silva, K.; Junior, F. Adubaçãonitrogenada, inoculação e coinoculaçãonacultura do feijoeiro-comum. Caderno de Ciências Agrárias Minas Gerais 2020, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- BETTIOL, J.V.T.; Filla, V.A.; Leal, F.T.; Coelho, A.P.; Meirelles, F.C.; Lemos, L.B. Sustainable production of common beans: inoculation, co-inoculation and mineral fertilization in early-cycle cultivars. Journal of Plant Nutrition 2020, 44, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schossler, J.H.; Meert, L.; Rizzardi, D.A.; Michaloviez, L. Componentes de Azospirillumbrasilense. Revista Scientia Agraria 2016, 17, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yadegari, M. Inoculationofbean (Phaseolusvulgaris) seedswithRizobiumphaseoliandplantgrowthpromotingrhizobacteria. Advan. in Envir. Biol. 2014, 8, 419–424. [Google Scholar]

- Chekanai, V.; Chikowo, R.; Vanlauwe, B. Response of common bean (Phaseolusvulgaris L.) tonitrogen, phosphorusandrhizobiainoculationacrossvariablesoils in Zimbabwe. Agric. Ecos.andEnvir 2018, 266, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, R.; Andrade, D.S.; Waureck, A.; Gomes, J.C. Nodulações e produtividades de grãos de feijoeirosdiante da adubaçãonitrogenadaou da inoculação com Rhizobium freirei. Rev.Bras. de Cien do Solo 2015, 39, 1661–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MORTINHO, E.S.; Jalal, A.; Oliveira, C.E.S.; Fernandes, G.C.; Pereira, N.C.M.; Rosa, P.A.L.; Nascimento, V.; de Sá, M.E.; Teixeira Filho, M.C.M. Co-inoculations with Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria in the Common Bean to increase efficiency of NPK fertilization. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumet, S.T.; Ayalew, T.; Roro, A.G.; Beshir, H.M. Intercropping and Rhizobium Inoculation Affected Microclimate and Performance of Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Varieties. Scientifica 2022, 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CONAB. Safrabrasileira de grãos. 2022. Available online: https://www.conab.gov.br/info-agro/safras/serie-historica-das-safras/itemlist/category/905-feijao (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Peres, L.A.C.; Terra, N.F.; Rezende, C.F.A. Produtividade do tomate industrial submetidoàadubaçãoorganomineralemcobertura. Braz. Jour. of Devel. 2020, 6, 10586–10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean Squares | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SV | DF | NPP | NGP | W100 | YIELD | |

| Blocks | 3 | 1.03889 | 2.53333 | 55.0666 | 62777 | |

| Cultivars (A) | 2 | 63.8125** | 0.8125NS | 85.5625** | 2374793.58** | |

| Treatments (B) | 3 | 87.5833** | 0.22222NS | 21.3611** | 2536109.13** | |

| A x B | 6 | 1.39583NS | 0.03472NS | 8.84028NS | 182579.44* | |

| Addi. Treatment | 2 | 12.25NS | 0.25NS | 36.0833** | 1213846.58** | |

| Treatments x Addi. treatment | 1 | 54.15NS | 0NS | 40.0166NS | 434435.51** | |

| Residue | 42 | 8.2508 | 0,27143 | 4.79286 | 56048.44 | |

| CV (%) | - | 33.2 | 17.3 | 7.6 | 22.6 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).