1.0. Introduction

Bambara nut (Vigna subterranean (L.) Verdc.) (BG) is a grossly under-utilised pulse seed-crop, believed to have originated from Africa (Nwanna et al. 2005; Kennedy et al. 2021). It is mostly believed that it originated from West Africa (sahelian region) from among the Bambara tribes-people very near to Timbuktu in Mali (Nwanna et al. 2005; Ibrahim and Ogunwusi (2016); Tan et al. 2020). It then migrated to numerous parts of Oceanian, Asian and South American countries (Baudoin and Mergeai (2001); Basile et al. 2021). It has been found to have many agronomical advantages including, a high nutrition value, drought tolerance, and ability to survive in soils that are considered intolerable (Ocran et al. 1998, Anchirinah et al. 2001; Azam- Ali et al. 2001; Khan et al. 2021). It mostly is regarded as a crop that is able to survive famine (Anchirinah et al. 2001; Azam- Ali et al. 2001, Ibrahim and Ogunwusi, (2016)), probably due to the association it forms with mycorrhiza.

Bambara groundnut by itself is a completely balanced food because it is fortified with Iron, contains 19% proteins such as lysines and methionines (Adu-Dapaah and Sangwan; (2004)), 63% carbohydrates and 6% oil and fatty acid (Minka and Bruneteau (2000); Okpuzor et al. 2010; Basile et al. 2021). Bambara groundnut has been found to be richer than groundnut in Nitrogen and essential amino acids such as isoleucines, leucines, valines, lysines, methtionine, threonine and phenylalanines (Ihekoronye and Ngoddy (1985); Ibrahim and Ogunwusi (2016);Tan et al. 2020).

Bambara groundnut is consumed in Nigeria and commonly called Okpa (Ibos), kwaruru (Hausa), epa roro (Yoruba) in Nigeria (Nwanna et al. 2005). It is used in cereal based confectionaries as composite flour, cake and bread making (Addo and Oyeleke (1986); Brough et al. 1993), used for the making milk drinks (Tanimu et al. 1990; Brough et al. 1993; Gwala et al. 2020), used directly in formation of cosmetics (Bamishaiye et al. 2011) and has also been used in the production of tempeh (Fadahunsi and Sanni (2010); Ibrahim and Ogunwusi (2016); Tan et al. 2020).

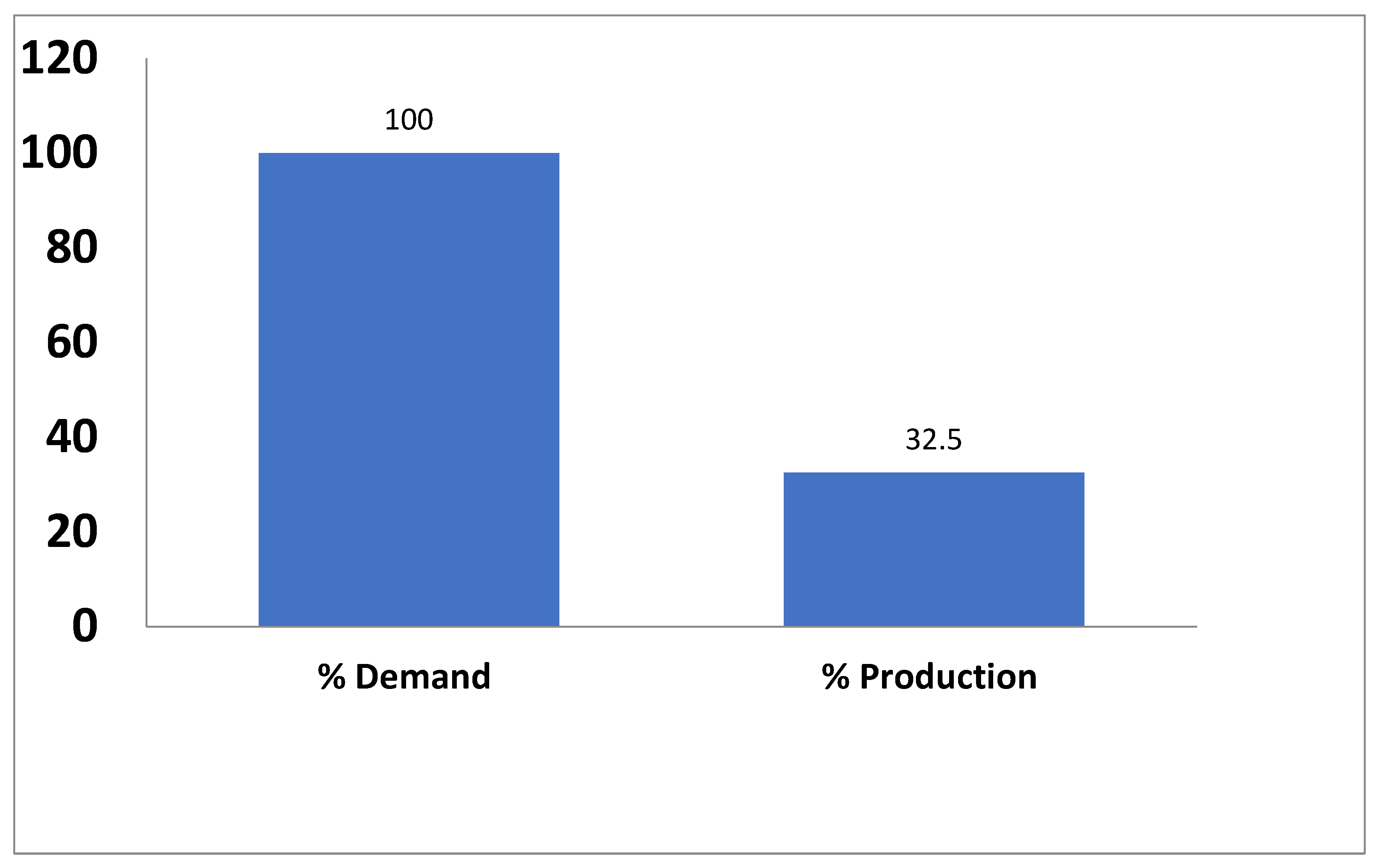

Inspite of the useful property-qualities of Bambara groundnut, its production is very minimal because research on the improvement and production of BG has not been previously looked into in-depth for numerous years, especially in Nigeria. It has therefore remained neglected, under-utilized and still does not have a well- developed market. The current production of Bambara groundnut in Nigeria is about 300,000 metric. A large but insufficient quantity of the beans is produced annually especially in Eastern and Northern parts of the country due to its relatively cheap production requirements (Jonathan et al. 2011). As earlier stated, this is still highly inadequate to meet the current demand(s) which is approximately about 800000 metric tonnes (Mshelia et al. 2011) (

Figure 1).

Sequence analysis has shown that Bambara groundnut is nodulated by several microorganisms that belong to both α and β Rhizobia spp. (Doku and Karikari (1971); Kanu and Dakora (2012); Fadimata et al. 2019). Also, Bradyrhizobium, Azorhizobium, Mesorhizobium and Ensifer which are members of α-proteobacteria have been listed as possible nodulators of Bambara groundnut (Sprent el al. 2010; Mohale et al. 2013; Fadimata et al. 2019).

Several bacteria under Rhizobia and closely related genera have been able to undergo symbiotic relationships with leguminous plants resulting in the formulation of nodules in which nitrogen fixation occurs. Nodules which are formed are results of the differentiating step that occurs in cellular processes stimulated by exchange of molecule signals which involves the expression of specified genes in each of the relating partner. When responding to plant flavonoid-compounds, the bacteria produce a family of lipo-chito-oligosaccharides molecules, called nodulations (Nod) factor, which in turn initiates nodule developments on root or stem of the legume (Denarie and Cullinore 1993; Schultze et al. 1994; Ajayi et al. 2020). Rhizobium nodulating (nod, nol, and noe) genes involved in producing Nod factors are located primarily on large plasmids, called symbiotic-plasmids or pSyms (Banfalvi et al. 1981; Rosenberg et al. 1981; Ajayi et al. 2020).

The gene(s) controlling infection, specificity and nodulation in a host specify the synthesis of Nod factors (NFs) that act as regulators of specified growth on legume-hosts (Fisher and Long (1992); De’narie and Cullimore (1993); Schultze et al. 1994; Spaink 1995; Ajayi et al. 2020). This process is called cross-inoculation and also explains why host specificity occurs in legumes. Nod Factors in every rhizobium species fall in the same chemical family; having tetrameric or pentameric chitin, at the non-reducing mono-N-acylated end. The backbones, consisting of a chitin oligomer, may be substituted differently at every end of the molecules, and these substitution(s) are the major differentiating-characteristic of every rhizobial species defining host-range (Roche et al. 1996; Ajayi et al. 2020).

Microbial inoculants are useful amendments in agriculture that utilize beneficial endophytes (microbes) that develop relationships which are symbiotic with the target crops (Timmusk et al. 2017) and are able to improve the plant health a common example of which are rhizobia spp. Improved efficiency of nitrogen fixation will increase yield of the Bambara groundnut but, there are no existing commercial inoculants for BG, hence, the need for research on promising effective Rhizobia strains for BG and to understand some of the genes responsible for nodulation in Bambara groundnut, their mechanism of regulation and their suitability, infectivity and effectivity as potential inoculant for Bambara groundnut. Moreover, in Nigeria, there is limited information on the diversity of rhizobia species that nodulate with bambara groundnut, hence the need to carry out this study. The data on distribution and genetic variation among the native rhizobia isolates would aid in selecting novel rhizobia strains that could be developed and used as bio-fertilizers in bambara groundnut production.

2.0. Methodology

2.1. Soil Collection

The soil samples (a total of 54) used for this experiment were collected from farm sites from ten local governments in each of three northern states in Nigeria including Kaduna, Kano, and Niger state. In Kano, soil samples were collected from Doguwa (6 soil samples were collected), Garko (3 soil samples were collected), Bunkure ( 3 soil samples were collected), Bichi, ( 3 soil samples were collected) and Tundun wada (2 soil samples were collected), Niger state, soil samples were collected) from Piakaro (6 soil samples were collected), Basso (6 soil samples were collected) and Shiroro (6 soil samples were collected), while in Kaduna state, soil samples were collected from Kajuru (6 soil samples were collected), Igabi (4 soil samples were collected), Soba (4 soil samples were collected), Zango kataf (3 soil samples were collected) and Lere (3 soil samples were collected). These were farm areas where legumes such as cowpea, ground nut, soybean, bambara etc., were previously planted.

2.2. Variety Selection

Five common varieties of BG (TVSu1248, TVSu631, TVSu644, TVSu49 and TVSu44) were planted on the field without inoculation and were screened for nodulation and plant biomass by sampling plants harvested at 8 weeks after planting (WAP) this was due to the longer germination time for bambara groundnut.

2.3. Isolation and Authentication

The soil samples collected (Soil (10 g) was weighed into 90ml of sterile diluent (0.1 g of K2HPO4 and 0.25 g of MgSO4.7H2O in 1 liter of distilled water) (Somasegaram and Hoben, 2012) and stirred in a horizontal shaker (HS 501 digital IKA-WERKE, GMbHα Co.KK ) for 25 mins to ensure that it was evenly mixed) were used to inoculate Bambara groundnut which was used to trap several species of Rhizobium in the soil that are symbiotic with Bambara groundnut under screen house conditions using four replicates. The strains were authenticated and the six most effective strains were selected for the field experiment.

2.4. Broth Preparation

Pure cultures of the strains were inoculated in yeast mannitol broth (Vincent 1970) sterilized at 121 °C for 15min at 1atm. The inoculated broth was incubated at 28 °C for 7-14 days (as some of them were slow growers) until a cfu/mL above 109 was attained (Woomer et al. 2011).

2.5. Field Preparation

A field with no previous history of inoculation was selected and was divided into four blocks and two varieties of Bambara and ten treatments were used in the field trial following a randomized complete block design (Fahime et al. 2012). Each block was 6 meters wide with a separating distance of 2 meters and had 40 ridges with 2 ridges for every variety in each treatment. The varieties used are TVSU1248, and TVSU 631, while the treatments used were BN28, BN7, BN5, BN50, BN1, BN44, USDA110 (Plants inoculated with Rhizobia (PIRs)), UREA 20 (+N20), UREA 60 (+N60), and un-inoculated Control (UNC). A minimum 20kg/ha P (Single Superphosphate) was applied to all treatments including the controls. Prior to crop establishment, soil evaluation was carried out to determine fertility of the soil (this was carried out at IITA Soil microbiology laboratory).

2.6. Percentage Nitrogen

After sampling, the shoot were weighed, stored in labelled paper bag and then dried in the oven at 68 ⁰C for two days or brown dry. The samples were weighed and then grinded to 1 mm using a grinder after which they were packed in small white envelops and transferred to the laboratory. They were then stored under dry conditions. Digested samples were used to determine the percentage nitrogen using the Kjeldahl, method, the readings were taken using a spectrophotometer (Labo Med. Inc. SPECTRO UV-VIS AUTO UV-2602) at 650 nm (Kjeldahl 1883).

2.7. Percentage Phosphorus

To determine the phosphorous content, the Murphy and Riley procedure was followed using spectrometry method with readings taken at 880nm using a spectrophotometer (Labo Med. Inc. SPECTRO UV-VIS AUTO UV-2602) (Murphy and Rilley (1962)). The valves obtained were converted to percentage values following the standard calculations.

2.8. Leaf Chlorophyll Reading

Plants were selected randomly among plots and chlorophyll was taken by used a SPAD meter to detect the amount of chlorophyll present in the leaf (three replicates) of the plant. Three leaves from two plants were selected randomly and the average was calculated to determine the chlorophyll for each replicate treatment (Uddling et al. 2007; Vollmann et al. 2011). The first reading was taken at four weeks after planting (WAP), a second reading was taken at 6 WAP (4th week in July, 2018). The third reading was taken at 8 WAP (2nd week in August, 2018).

2.9. Determination of Weight of Plant Seed

Pod were dried and weighed intermittently till constant weight was obtained in pod, the pods were then de-shelled by putting the pods in bags and manually beating them with a club to collect the seed which were then weighed to obtain the weight of the seeds (Somaseghen and Hoben (2012); Doloum et al. 2017).

2.10. Determination of the Amount of Nitrogen (N2) Fixed

The amount of nitrogen fixed was determined (using Uriede analysis) and compared with that of the control plants. Stems and stem segments of Bambara groundnut were harvested and leaves removed. The samples were placed in properly labelled bags and drying was done at 65–80 °C in an air oven for two days. The plant tissue was grounded and passed through a 60-mesh (1.0 mm) screen and then stored in a dry place until extraction. The optical density was read at 525 nm on a spectrophotometer (Labo Med. Inc. SPECTRO UV-VIS AUTO UV-2602) (Herridge and People (1990)).

2.11. Yield Performance of Bambara Groundnut Varieties

Plants were harvested at maturity, after which the seed pod were collected and weighed before drying after drying and after depodding the yield was determined by the number of pods produced, the size and number of the seeds compared with the control treatment. The yield per plot was calculated as yield per hectare (Somaseghen and Hoben (2012); Doloum et al. 2017).

2.12. Determined Seed Yield (Kg∙ha−1):

The yield of seeds obtained from plants was calculated in Kg/ha using the formula below:

where,

Y = dry weight of seeds in Kg/ha;

K = dry weight of seeds per unit of experimental area;

E.A = surface area for experiment (m2);

1 ha = 10,000 m2.

2.13. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

Pure cells of the six selected strains were collected in Eppendorf tubes and extracted using ZYMO fungal/ bacterial extraction kit using modified methods (Ajayi et al. 2022a). Also, because of the slimy and protein rich nature of rhizobia cells proteinase K was added to the lysis buffer to enhance the extraction process. The extracted DNA was used to carry out 16S rRNA PCR amplification using 27F: AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG, 1492R: TACGGTACCTTG TTACGACTT using the following conditions: 95˚c (5mins), 94˚c (30 secs), 58˚c (30 secs) 25 cycles, 72 ˚c (45secs), 72 ˚c (7mins), 10 ˚c (∞) (Ajayi et al. 2022b). The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and Jukes-Cantor model (Jukes and Cantor (1969)). Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA X (Kumar et al. 2018). Gene sequences were submitted to the NCBI gene bank (where accession numbers were assigned to them).

2.14. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 2.0 with two-way ANOVA at α 0.05. Our hypothesis was to show that Indigenous rhizobia strains have potential to improve and increase the yield of Bambara groundnut and nitrogen fixation (making nitrogen available for plant) when applied as inoculant.

3.0. Results

3.1. Bambara Groundnut Variety Selection

The Bambara groundnut varieties TVSU1248 (brown, variety1) and TVSU631 (black variety2) were selected for carrying out the experiment in the screen house and field based on their performance in the preliminary field test which was conducted to test their nodulation response and performance of some of the commonly used varieties (

Table 1,

Figure 2). They had an average shoot weight of 79.81 ±1.81 g and 63.15 ± 3.21 g, an average root weight of 20.53 ± 6.49 g and 15.36 ± 5.98 g and average nodule number of 14.17 ± 0 and 13 ± 2 respectively.

3.2. Trapping and Isolation of Rhizobia Strains

Of the 54 soil samples used for trapping experiment, nodules were recovered from Bambara plants inoculated with 32 of the soil from which different spp. of rhizobia were isolated, this further confirms the promiscuous nature of Bambara groundnut more strains were recovered from the soil in which cowpea were previously planted and least were recovered from fields where soybean were previously planted. This is probably attributed to the promiscuous nature of Cowpea which is also able to form symbiosis with several app. Of rhizobia, while soybean on the other hand forms symbiosis with only Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Fifty of the isolated strains showed ability to fix nitrogen after authentication while six showed best performance and were selected to be used for field experiments.

3.3. Broth Inoculant Concentration

The concentrations of bacteria in the broth cultures used as inoculant were BN1 (isolated from shiroro in Kano state) 16.9 x1010 cfu/mL, Bradhyrhizobium sp-BN5 (isolated from Doguwa in Kano state) 15.6x 1010 cfu/mL, Bradhyrhizobium vignea strain-BN7(isolated from Doguwa in Kano state) 9.00 x1010 cfu/mL, Bradhyrhizobium vignea strain-BN28 (isolated from Shiroro in Niger state) 0.85 x1010 cfu/mL, Bradhyrhizobium vignea strain-BN44 (isolated from Doguwa in Kano state) 12.2 x 1010 cfu/mL, Bradhyrhizobium strain-BN50 (isolated from Doguwa in Kano state) 3.95 x 1010 cfu/mL, USDA110 (USA) 7.56x 1010 cfu/mL. Kano and Niger were reservoirs of Bambara groundnut symbiotic strains particularly Shiroro and Doguwa.

3.4. Field Soil Analysis

The table below shows the results of soil analysis of the field being analyzed. The soil pH organic carbon, Nitrogen, bray P and percentage clay, silt and sand were determined as shown in

Table 2. The soil profile showed that the soil was suitable for planting Bambara, as it had good water retention, but had low P which was augmented for by adding P fertilizer at a minimum rate of 20kg/ha.The % organic carbon was also which could imply a reduced soil microbiome and nutrient retention in soil. The soil pH was slightly acidic but mostly suitable for the growth of the rhizobia inoculant. The soil also had a low percentage of %N.

3.5. Percentage Nitrogen Content in Bambara Groundnut Plants

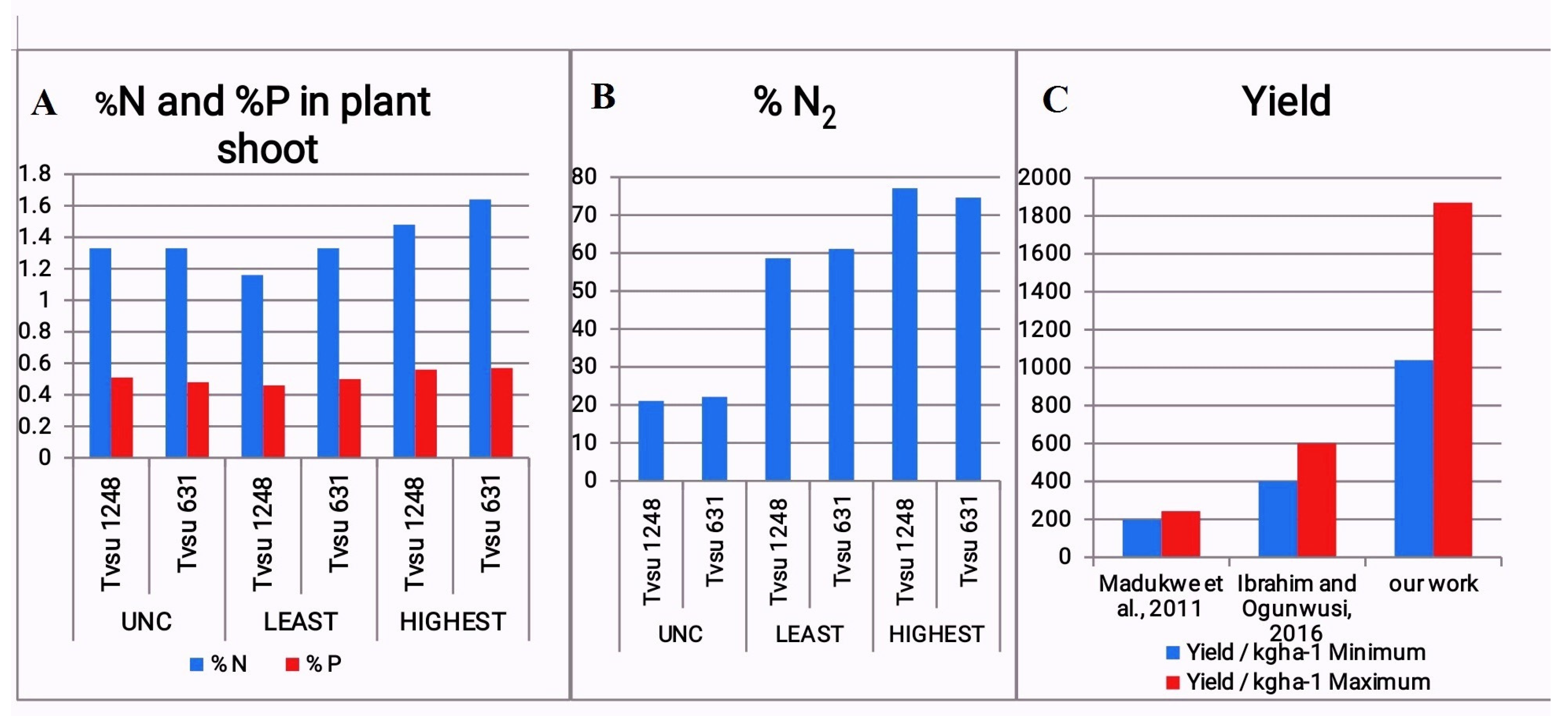

Variety2 (TVSU 631) had an improved absorption of nitrogen released through biological fixation nitrogen as seen by the higher nitrogen levels in the plant shoot. Plants inoculated with Rhizobia (PIRs) had a higher %N (1.37±0.05% -1.64±0.11%) than the un-inoculated control (UNC) (which had a value of 1.33±0.1 in both varieties) except for BN50 variety2 (1.28±0.05%), BN28 (1.26±0.08%) and plants inoculated with BN44 variety 1(TVSU 1248) which had the lowest % N uptake (1.16±0.11%). Variety2 had a higher % N in plant shoots, than variety1, showing that they had a higher uptake of N responded better to biological nitrogen fixation. The PIRs all had higher % N content than the +N60 (1.33±0.12% (V1), 1.33±0.16% (V2) and +N20 (1.33±0.05% (V1), 1.33±0.06% (V2)) treatments except for plants inoculated with BN44 for variety 1, BN50 variety1 and BN28 variety1. There was no significant difference between the % N of PIR and that of the UNC, +N20, +N60 plants for the TVSu 1248 variety while there was a significant difference between the values observed for the PIR and the UNC for the TVSu 631 variety. The strains were able to actively fix nitrogen biological, playing an important role in the fixation of nitrogen in the soil to make nitrogen available for Bambara plants (

Table 3,

Figure 3a).

3.6. Percentage Phosphorus Content in Bambara Groundnut Plants

Variety1 showed a better uptake of phosphorus than variety2. The PIRs had a higher %P than the UNC (0.51±0.02% and 0.48±0.02%) except for BN44 variety1, which had a lower %P than its counterpart un-inoculated control. Plants inoculated with BN28 (0.56±0.04%, 0.55±0.18%) and BN7 (0.57±0.01%) had the highest %P for both varieties while plants inoculated with BN44 (0.46±0.02% and 0.52±0.02%) had the lowest %P (

Table 3,

Figure 3a). Plants with +N20 had a higher P uptake than +N60. BN1 inoculated plants had the same amount of %P in their plant shoot in both varieties (0.53±0.017 % and 0.53±0.03%) USDA110 (0.52±0.015% and 0.51±0.03 %), +N20 (0.56±0.009% and 0.55±0.01%), +N60 (0.55±0.06% and 0.52±0.015%) (

Table 3) (20.86±2.58 g and 26.86±2.94 g), BN5 (32.30±2.35 g and 22.14±1.47 g), BN28 (23.12±1.69 g and 23.88±3.43 g), BN50 (32.30±2.35 g and 22.14±1.47 g) variety2 had higher %P than that of +N20 variety2. Others had lower % P, while none had a higher % P than the variety2 plants of +N60 and +N20. The variety type significantly influenced P uptake.

3.7. Leaf Chlorophyll Reading of Bambara Groundnut Plants

At the 4th WAP, the leaf chlorophyll content exhibited a comparable trend, with variety 1 displaying higher concentrations than variety 2. Additionally, PIRs and plants treated with urea had higher leaf chlorophyll concentration than the un-inoculated controls. The SPAD readings varied between 45 mg/L and 55 mg/L with +N20 having the highest value of 55.59±1.28 mg/L while BN7 the highest reading of 54.28±1.17 mg/L for variety 2. The +N60 recorded a lower readings in both varieties (50.78±0.74, 48.46±0.66 mg/L) than that of +N20 and all the PIRs except USDA110 and BN5 (50.53±1.38 mg/L and 49.74±1.47 mg/L respectively). All varieties had lower chlorophyll concentrations than the +N20 for variety1, for variety2 on the other hand, only BN7 (54.28±0.79 mg/L), BN28 (53.60±1.05 mg/L) had higher chlorophyll values than the +N20 (51.46±0.74 mg/L) variety2 while BN44 (51.43±1.58 mg/L) had similar values.

The leaf chlorophyll concentrations at second reading ranged from 48 mg/L to 55 mg/L which were higher in variety 1,with +N60 having the lowest concentrations. The Rhizobia inoculants could increase the chlorophyll concentration with little or no significant difference to +N20, while +N60 seemed to decrease the leaf chlorophyll concentrations which were very similar in both varieties. Plants inoculated with BN1 and BN28 seemed to have the highest leaf chlorophyll concentrations in both varieties. The leaf chlorophyll values in the 6th week increased slightly to between 48.59±0.35 mg/L and 50.29±1.16 mg/L (variety1 plants still maintained higher concentrations). The leaf chlorophyll concentrations of +N60 seemed to increase significantly, particularly for variety1. There was significant difference in leaf chlorophyll of PIRs compared with that of the control plants (

Table 3).

The chlorophyll values increased slightly at the 8th WAP and were between 48 mg/L and 56 mg/l. Variety1 still maintained higher concentrations showing that varieties responded differently regarding leaf chlorophyll concentrations, in response to inoculation.

3.8. Nitrogen Fixation of Bambara Groundnut Plants

The PIRs had higher %N

2 fixed in the plants than the UNC and +N60 in both varieties and PIRs had a higher amount of %N

2 fixed than Urea 20 for variety 2 but for variety 1, USDA110 had a lower fixed N

2 than +N20. This showed that the indigenous strains could fix nitrogen better than the already available commercial

Bradhyrhizobium japonicum stain (USDA 110). The amount of N

2 fixed ranged between 61.30± 6.13% - 74.63±3.17% among the rhizobial treatments. There was a significant difference in leaf chlorophyll of PIRs compared with that of the UNC plants (

Table 3,

Figure 3b).

3.9. Yield Kg/Ha of Bambara Groundnut Plants

Variety 1 plants had higher yields than Variety 2 plants except for the BN50 inoculated plants (1365.18±157.57 kg/ha (V1), 1442.10±105.88 kg/ha) (which was slightly different) and +N20 (725.03±164.32 kg/ha (V1), 1085.10±65.95 kg/ha) (where there was an enormous difference in yield). The yields of PIRs were higher than that of the UNC both in Variety 1 and Variety 2. BN5 inoculated plants had the highest yield for both Varieties (V1: 1869.85±273.68 kg/ha, V2: 139.60.10±159.89 kg/ha) and was closely followed by plants inoculated with BN50 (V1:1365.18±157.57 kg/ha, V2:1442.10±105.88 kg/ha) while the UNC had the least yield (V1: 935.66±177.80 kg/ha, V2: 673.10±250.00 kg/ha). All PIRs had better yields than +N20 (V1: 725.03±164.32 kg/ha, V2: 1085.10±65.95 kg/ha) for both varieties except for BN44 variety 2 (1039.60±30.42 kg/ha) which had a lower yield than variety 2 of +N20 treatment (1085.10±65.95 kg/ha). BN28, BN50 and BN5 had more yields for variety 1 than +N60 (V1: 1372.90±209.15 kg/ha, V2: 1157.40±241.81 kg/ha) while all the rhizobia treatments for Variety 2 had a higher yield than +N60 Variety 2 except BN7 (which was similar) and BN44 which was lower than +N60 Variety 2. PIRs increased the yield of Bambara g/nut (

Figure 4)from about 400 kg /ha-600 kg/ha (

Table 3,

Figure 3c).

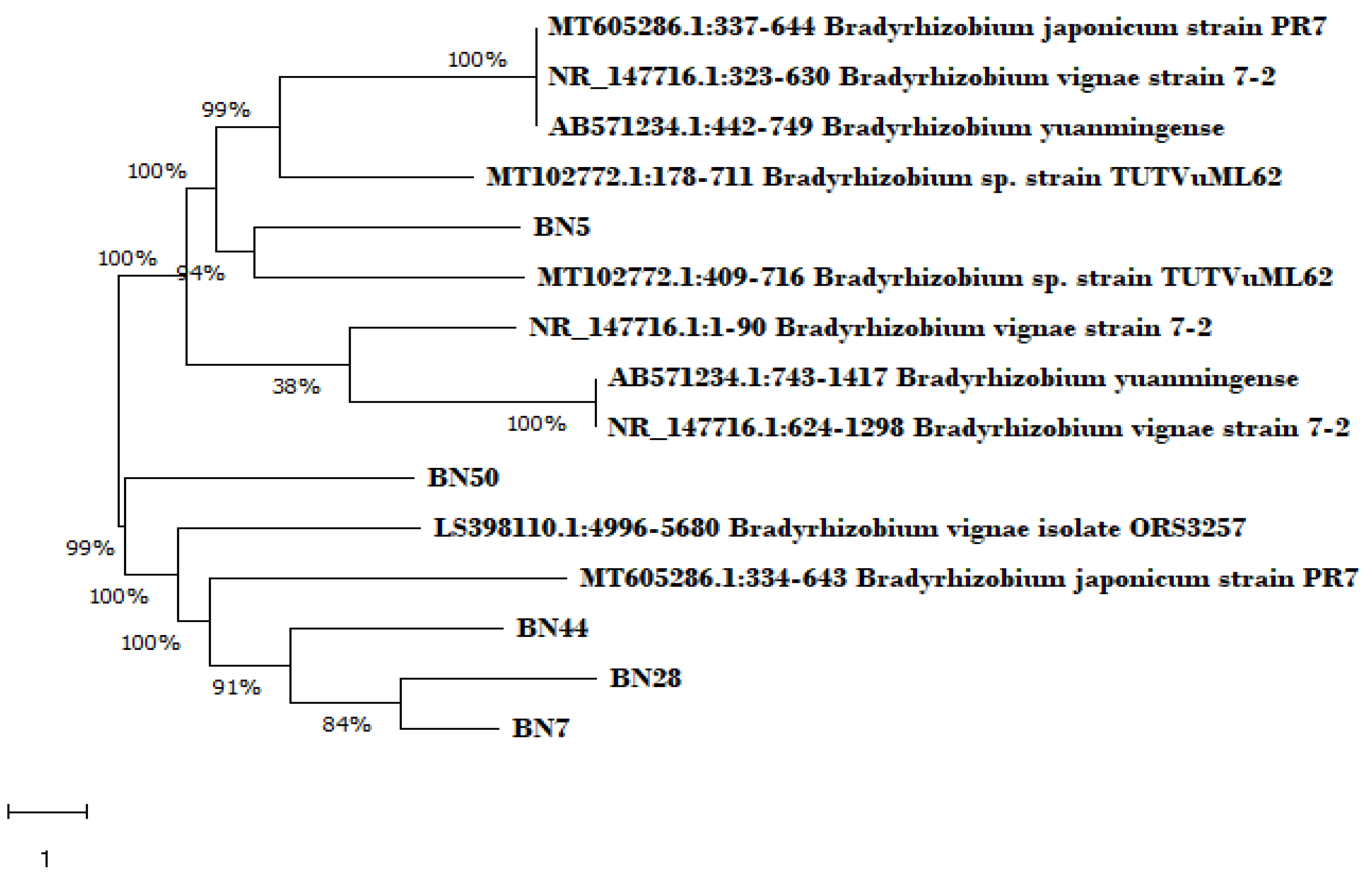

3.10. Blast Outcome of Sequenced Rhizobia Strains

The gene sequences obtained from sequencing were blasted using the NCBI website to determine identification of strains used and a phylogram was drawn to show the relationship between these strains and their level of closeness and relatedness. Most of the strains were identified as

Bradhyrhizobium strains of varying spp. but more closely related to

Bradhyrhizobium Vignea this is shown in the Phylogram (

Figure 5). The isolate BN5 was identified as

Bradhyrhizobium sp ORS 3257 with accession number LS398110.1, isolate BN7, BN28 and BN44 (but different sub species) were identified as

Bradhyrhizobium vignea strain 7-2, with accession number NR147716.1, isolate BN50 was identified as

Bradhyrhizobium strain DSM30131, while BN1 was unidentified. Provided are the links for the submitted sequences: 1. BN50 (PRJNA957835) Bradyrhizobium vignae strain: ORS325 (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA957835), 2. BN44 (PRJNA957847) Bradyrhizobium sp. strain TUTVuML62 (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA957847), 3. BN7 (PRJNA957848) Bradyrhizobium vignae (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA957848), 4. BN5 (PRJNA957842) Bradyrhizobium japonicum strain: PR7(

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA957842), 5. BN28 (PRJNA957843) Bradyrhizobium vignae strain (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA957843)

4.0. Discussion

The objective of this study was to recover/isolate Bambara groundnut symbiotic Rhizobia from soil samples collect by trapping them in the nodules of Bambara ground nut plants. These strains were then authenticated and tested for their efficiency and finally applied under field conditions as inoculant on two varieties. From our study, the soil samples (54) used for this experiment collected from farm sites at ten local governments in three northern states of Nigeria including Kaduna (North West), Kano (North West), and Niger state (North Central) were sites where legumes such as cowpea, groundnut, soybean, Bambara groundnut and so on were previously planted. These soils were a reservoir of Bambara groundnut symbiotic strains, allowing the trapping of numerous Rhizobia isolates, confirming the promiscuous nature of Bambara groundnut in nodulating with several Rhizobia spp. This correlates with the findings of Doku and Karikari (1971); Kanu and Dakora (2012) and Fadimata et al. (2019) where Bambara groundnut nodulated with diverse microorganisms that belong to both α and β Rhizobia spp. and the work of Sprent et al. (2010) and Mohale et al. (2013) who listed Bradyrhizobium, Azorhizobium, Mesorhizobium and Ensifer as possible nodulators of Bambara groundnut. However, Tamimi and Young, (2004) discovered that Rhizobium etilis was the most common type of bean nodulating Rhizobia in different soil samples collected from various places in Jordan and Laguerre et al. (1993); Herrera-Cervera et al. (1999) reported the presence of R. giardinii and R. gallicum to be associated with nodulation of P. vulgaris in France and Spain respectively. The study of Aserse et al. (2012) shows that all the soybean nodulating strains identified in soils of Ethiopia were phylogenetically different from the expected inoculant strains, B. japonicum USDA 136 and CC709.

The two varieties selected for the experiment TVSU1248 (brown, variety1) and TVSU631 (black variety 2) were based on results of a field test. The trapping experiment could sufficiently cause nodulation in the varieties when they were inoculated with solutions of the soil sample with large number of nodulation occurring in the plants in 32 out of the 54 soils collected. This was similar to the findings of Mishra et al. (2012) where trapping was used to recover 221 Rhizobia strains from 8 soil in Mimosa pudica, also that of Silva et al. (2012) and Jordana et al. (2017) where trapping was used to recover 308 Rhizobia strains respectively from soil using cowpea plants, and the work of Soumaya et al. (2019) where 54 soils were collected and only 15 showed nodulation in White lupin plant. This also confirmed that the soils contained a large number of Bambara groundnut symbiotic strains, and that trapping offered a suitable method for recovering of Rhizobia strains from legume cultivated soils and soils.

The Rhizobia strains isolated and purified on Congo red agar appeared as pinkish, whitish opaque colonies or colourless translucent mocoid growths and grew at 25°C for 3-7 days as shown in the work of Woomer et al. (2011); Somasegaram and Hoben (2012). It was also similar to the findings of Fadimata et al. (2019) where the number of days for the growth of the microsymbionts of Bambara groundnut was between 2-15 days with the slow-growers growing between 6-15 days. However, this observation differs from the work of Ankur et al. (2012) where Rhizobia was incubated at 35°C for 24 hours.

Of the 150 Rhizobia isolates obtained, after authentication using broth cultures of the isolates and inoculation of pre-germinated Bambara groundnut plant under sterile conditions, only about 70 strains showed nodulation on authentication. This was similar to the finding of Fadimata et al. (2019) who recovered 89 isolates from soil but only 45% showed nodulation in BG upon inoculation. Similar finding was also reported in the work of Eutropia and Patrick (2013) where inoculation of soybean caused nodulation and Yadav et al. (2017) where rhizobia inoculation of chickenpea in sterilized soil resulted in nodulation of the plant. We observed that germination occurred after 2 weeks in both varieties in pot and on the field indicating a slow germination rate. This was also reported by Linneman and Azam-Ali (1993); Swanevelder (1998) and Brink et al. (2006), as a matter of fact, unlike in groundnut and cowpea which normally germinate between three to five day according to Awosaike et al. (1990) and Ataur et al. (2006) respectively.

The concentration of the broth was higher than the required standard of 109 cfu/mL according to the work of Woomer et al. (2011); Somasegaram and Hoben (2012). It was also higher than the concentration of microsymbionts of Bambara groundnut used for inoculation in the work of Fadimata et al. (2019) which was between 107- 108 cfu/mL.

The purity of the DNA extract ranged from 1.73-1.89 while the various concentrations of the extracted DNA were Bradhyrhizobium strain-BN50 (72.9 ng/µl), BN5 (74 ng/µl), Bradhyrhizobium vignea strain-BN44 (70.4 ng/µl), Bradhyrhizobium vignea strain-BN28 (72.9 ng/µl) Bradhyrhizobium vignea strain-BN7 (80.2 ng/µl). The concentrations of the extracted DNA were higher than those extracted in the work of Fadimata et al. (2019) which were between 40- 50 ng/µl. this may be due to variation in the methods used for extraction of the DNA.

Variety2 (TVSU 631) took up more of the nitrogen released by biological nitrogen fixation as observed by the percentage nitrogen in the plant shoot. There was no significant difference between the %N of PIR and that of the UNC, +N20, +N60 plants for the TVSu 1248 variety, while there was a significant difference between the values obtained for the PIR and the UNC for the TVSu 631 variety. Strains showed the ability to actively fix nitrogen into the plants and that biological nitrogen fixation play an important role in the fixation of nitrogen and making nitrogen available for Bambara groundnut. The strains can improve Bambara productivity when used as inoculant and can be used as an alternative to fertilizer. This was similar to the findings of Ahmet et al. (1981) and Awosaike et al. (1990) where Rhizobia inoculation increased the yield of cowpea, Ataur et al. (2006) where inoculation increased the yield of groundnut. Also, Zhu et al. (2008) and Aliyu et al. (2013) seperately reported that inoculation was able to significantly increase Nitrogen uptake in soybean, groundnut but not in cowpea while Yakubu et al. (2010) made the same findings in Bambara groundnut where it varied significantly with cultivars.

The +N20 plants seemed to have a higher P uptake than +N60 plants. There was no steady pattern in the P uptake shown by the varieties used although variety1 showed better ability to take up phosphorus. The PIRs had a higher %P value than the UNC Bradhyrhizobium vignea strain-BN28 and Bradhyrhizobium vignea strain-BN7 had the highest %P values for both varieties while plants inoculated with Bradhyrhizobium vignea strain-BN44 had the lowest values. This differed from the findings of Mahmudul et al. (2021) who reported increased %phosphorus in plant shoot on application of N30P60 kg/ha of fertilizer in Bambara Groundnut cultivars.

The PIRs increased the yield of Bambara groundnut from about 400 kg/ha -600 kg/ha according to Ibrahim and Ogunwusi (2016) to about 1039.60±30.42 kg/ha- 1869±273.68 kg/ha giving similar conclusion to that of Egbe et al. (2009) and Egbe et al. (2013) where it was suggested that rhizobial inoculation should be considered for improving the yield of Bambara groundnut. Seed yield ranged from 1039.60±30.42 kg/ha - 1869±273.68 kg/ha which was higher than that obtained in the report of Madukwe et al. (2011) where the seed yield ranged between 197.2 kg/ha - 243.3 kg/ha showing that inoculation had a positive effect on their yield. While, according to Ellah and Singh (2008), application of Phosphorus had no significant effect on the kernel and shaft yield. This was similar to the findings of Awosaike et al. (1990) and Ahmet et al. (1981) where Rhizobia inoculation increased the yield of cowpea, Ataur et al. (2006) where inoculation increased the yield of groundnut. Aliyu et al. (2013) and Zhu et al. (2008) also reported that inoculation could significantly increase Nitrogen uptake in soybean, groundnut but not in cowpea while Jonah et al. (2012) noted that Bambara groundnut yield varied significantly with cultivars. Doloum et al. (2017) in their research carried out in Chad and Cameroon reported an increase in yield by 72.71% upon inoculation with rhizobia from groundnut. This work was able to record double increase in yield using its own symbiotic strain as inoculant. This also confirmed the study carried out by Mshelia et al. (2012) on the potential of BG in accessing food security in Nigeria. Therefore, it was suggested that research needs to be carried out to identify cultivars and highly effective indigenous rhizobia strains in our native habitat with the potential for increasing its yield. Also the work of Ibrahim and Ogunwusi (2016) suggested that the production of Bambara groundnut was inadequate to satisfy the demand of local farmers because of its low production and that research to increase its production needed to be carried out if its demand for industrial production processes is to be met. Affirming that Indigenous rhizobia strains are needed to boost Bambara groundnut production.

The chlorophyll readings at the 2nd week showed a similar pattern, with variety1 having higher values than variety2 and PIRs. Both Rhizobia and urea treatments had higher values than the un-inoculated controls. All varieties had lower leaf chlorophyll values than that of the +N20 for variety1. For variety2 on the other hand, only two treatments had higher chlorophyll values than the +N20 variety2. The PIRs increased the chlorophyll content catching up with +N20, while that of +N60 appeared to decrease. Here, their chlorophyll readings were very similar with slight variations in values. The leaf chlorophyll values in the fourth week increased slightly and the chlorophyll values of variety1 were still higher than variety2. There was a significant difference in leaf chlorophyll of PIRs compared with that of the +N control plants and UNC plants. Rhizobia inoculation had a significant effect on the chlorophyll values of the experimental plant leaves which is similar to the findings of Eutropia et al. (2013); where rhizobial inoculation has significant effect on the chlorophyll contents of soybean plants and Teixeira et al. (1999) in cowpea cultivars.

The PIRs had higher %N2 fixed in the plants than the UNC and +N60 in both varieties and PIRs had a higher amount of %N2 fixed than UREA20 for variety2 but for variety 1, USDA110 had a lower fixed %N2 than +N20. This showed that the indigenous strains were able to fix nitrogen better than the already available commercial Bradhyrhizobium japonicum stain (USDA 110). This collaborated with the findings of Ojo et al. (2017) and Dianda et al. (2014) where indigenous strains were shown to perform better than other stains when applied to cowpea and soybean respectively. Aliyu et al. (2013) also reported that inoculation was able to significantly increase biological nitrogen fixation in soybean, groundnut but not in cowpea. Bamishaiye et al. (2011) also reported that Bamabara groundnut was able to increase the nitrogen in soil. Yakubu et al.’s (2010) work showed that Rhizobia inoculation greatly increased the nitrogen fixed in cowpea, groundnut and Bambara groundnut.

Five of the six strains used were identified as Bradhyrhizobim spp. particularly Bradhyrhizobim vignea. Sprent et al. 2010; Mohale et al. 2013; Fadimata et al. (2019), made similar findings where Bradhyrhizobim spp. was listed as one of the nodulating species for Bambara groundnut. On the other hand, Tamimia and Young (2004) discovered that Rhizobium etilis is the most common type of bean nodulating Rhizobia from different soil samples collect from various places in Jordan and Laguerre et al. 1993 reported the presence of R. giardinii and R. gallicum to be associated with nodulation of Phaseolus vulgaris in France and Spain respectively. The study of Asersea et al. 2012 showed that all the soybean nodulating strains identified in soils of Ethiopia were phylogenetically different from the expected inoculant strains, B. japonicum USDA 136 and CC709. Also, several diversity studies of the population of rhizobia that can nodulate common bean in places where Phaseolus vulgaris is a natively grown plant a large genetic diversity of rhizobia has been obtained (Eardly et al. 1995; Martinez-Romero and Caballero-Mellado 1996)

This study was aimed at and was able to report the knowledge gap with the sole target of increasing the yield of BG using indigenous rhizobia strains trapped from soils collected from fields where legumes had been previously planted in some states in the northern part of Nigeria

5.0. Conclusion

Bambara groundnut responded to rhizobia inoculation especially the indigenous rhizobia strain in Nigerian soils resulting in increased yields (almost double in some strains) and % fixed nitrogen in the plants, improved the soil quality, and improved plant health showing that they were well adapted to the environmental factors and conditions and could therefore thrive comfortably in the soil to effectively and efficiently infect the plant root forming numerous nodules. Soils in Niger and Kano states proved to be reservoirs of effective Rhizobia strains particularly for Bambara groundnut symbiont.

It is vital to consider indigenous rhizobia when developing rhizobia inoculant for improving Bambara ground nut production. In conclusion Bambara groundnut can benefit immensely from indigenous rhizobia inoculant to improve its yield.

Recommendation

These Rhizobia strains, especially BN50, BN5 should be considered for large-scale production of inoculants for improving the yield of Bambara groundnut especially in Nigeria.

Funding

The research was funded by N2Africa Project (Putting nitrogen fixation to work for smallholder farmers in Africa) by IITA- funding (technical and financial support).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adu-Dapaah H. K. and Sangwan R. S. Improving Bambara groundnut productivity using gamma irradiation and in-vitro techniques. Afr J of Biotech 2004; 3: 260- 265. [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, O.O., Dianda M. and Fagade O.E. Evaluation of some Nodulation Genes found in Bambara Symbiotic Rhizobia Strains. Int J of Inn Sci and Res Tech 2020; 5:42-46.

- Ajayi O. O., Adekanmbi A., Dianda M. et al. a. Modified Methods for quick and safe extraction of DNA from common microbiological samples. EC Micro J 2022; 18: 13-20.

- Ajayi O. O., Adekanmbi A., Dianda M. et al. b. Simplified cocktail mix and PCR conditions for amplification of extracted DNA from common bacteria, fungi and algae isolates for Microbiological studies”. Int J Res and Inn in App Sci 2022, https://www.rsisinternational.org/journals/ijrias/DigitalLibrary/volume-7-issue-4/40-44.pdf.

- Anchirinah V. M., Yiridoe E. K. and Bennett-Lartey S. O. Enhancing sustainable production and genetic resource conservation of Bambara groundnut. A survey of indigenous agricultural knowledge system. Out on Agri 2001; 30: 281- 288. [CrossRef]

- Azam-Ali S. N., Sesay A., Karikari K. S., et al. Assessing the potential of an under-utilized crop- a case study using Bambara groundnut. Exp Agric 2001; 37: 433-472. [CrossRef]

- Bamishaiye O. M., Adegbola J. A. and Bamishaiye E. T. Bambara groundnut an under-utilized nut in Africa. Adv in Agri Biotech 2011; 1: 60- 72.

- Banfalvi Z., Sakanyan V., Koncz C., et al. Location of nodulation and nitrogen fixation genes on a high molecular weight plasmid of Rhizobium meliloti. Mol and Gen Gene 1981; 18: 318–325. [CrossRef]

- Basile B., Rumman K. and Oliver M. Under-utilised crops and rural livelihoods: Bambara groundnut in Tanzania. Oxf Deve Stud 2021; 49: 88-103. [CrossRef]

- Baudoin J. P. and Mergeai G.. Grain Leg-umes in Crop production in Tropical Africa, 2001, 313 –317.

- Brough S. H. Azam-Ali, S. N. and Taylor A. J. The potential of Bambara groundnut in vegetable milk production and basic protein functionality system. J of Food Chem 1993; 47: 227- 283. [CrossRef]

- Dénarié, J. and Cullimore J. Lipo-oligosaccharide nodulation factors: a minireview new class of signaling molecules mediating recognition and morphogenesis. Cell 1996; 74: 951–954. [CrossRef]

- Dianda M., Boukar O., Ibrahim H. et al. Indigenous Bradyrhizobium And Commercial Inoculants In Growth Of Soybean [Glycine Max (L.) Merr.] In Northern Nigeria. Proceedings of the 1st International conference on Drylands. 2014, 14-16.

- Doku E. V. and Karikari S. K. Bambara groundnut. Econ Bot 1971; 25: 225 - 262.

- Doloum G., Mbaiguinam M., Steve T. T. and Albert N. Influence of Cross Inoculation on Groundnut and Bambara Groundnut-Rhizobium Symbiosis: Contribution to Plant Growth and Yield in the Field at Sarh (Chad) and Ngaoundere (Cameroon). Ame J of P Sci 2017, http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajps.

- Fadimata Y. I. I, Sanjay K. J., Mustapha M. and Felix D. D. Symbiotic effectiveness and ecologically adaptive traits of native rhizobial symbionts of Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea L. Verdc.) in Africa andtheir relationship with phylogeny. Sci Rep nat res 2019. [CrossRef]

- Fadahunsi I. F. and Sanni A. I. Chemical and biochemical changes in Bambara nut (Voandzeia subterranea (L) Thours) during fermentation to ‘Tempeh’. Electronic Journal of Environmental, Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010; 9: 275-283.

- Fahime Shokrani, Alireza Pirzad, Mohammad Reza Zardoshti and Reza Darvishzadeh. Effect of irrigation disruption and biological nitrogen on growth and flower yield in Calendula officinalis L. African Journal of Biotechnology 2012, http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB.

- Fisher R. F. & Long S. R. Nature. 1992. 357: 655–660.

- Gwala, S., Kyomugasho C., Wainaina I., Rousseau S., Hendrickx M. and Grauwet T.. Ageing, dehulling and cooking of Bambara groundnuts: consequences for mineral retention and: in vitro bioaccessibility. Food Functions. 2020;11:2509–2521. [CrossRef]

- Herridge D. F. and Peoples M. B. Ureide Assay for Measuring Nitrogen Fixation by Nodulated Soybean Calibrated by 15N Methods. Plant Physiology 1990; 93: 495-503. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H. D. and Ogunwusi, A. A. Industrial potentials of Bambara nut. Journal of Poverty, Investment and Development 2016; 22:12-16.

- Ihekoronye, A.I. and Ngoddy, P.O.. Integrated.Food Science and Technology for the tropics.Macmillan Published London and Basingstoke,1985.

- Jukes, T.H. and Cantor C.R. Evolution of protein molecules. In Munro HN, editor, Mammalian Protein Metabolism, Academic Press, New York, 1969, 21-132.

- Jonathan S. G., Fadahunsi I. F. and Garuba E. O. Fermentation Studies During The Production Of ‘Iru’ From Bambara Nut (Voandzeia Subterranea L. Thours), An Indigenous Condiment From South-Western Nigeria. Electronic journal of environmental, Agricultural and food chemistry 2011; 10: 1829-1836.

- Kanu S. A. and Dakora F. D. Symbiotic nitrogen contribution and biodiversity of bacteria nodulating Psoralea species in the Cape Fynbos of South Africa.Soil. Biology and Biochemistry 2012; 54: 68–76. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A., Bright O. A., Joseph N. B., et al. Farmers’ perceptions, constraints and preferences for improved Bambara groundnut varieties in Ghana. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2021; 3:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Khan M. M. H., Rafii M. Y., Ramlee S. I., et al. Bambara Groundnut (Vigna subterranea L. Verdc): A Crop for the New Millennium, Its Genetic Diversity, and Improvements to Mitigate Future Food and Nutritional Challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13: 5530. [CrossRef]

- Kjeldahl, J. New method for the determination of nitrogen in organic substances, Zeitschrift fur analytische chemie 1883; 22: 366-383.

- Kumar, S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., et al. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018; 35:1547-1549. [CrossRef]

- Minka S. R. and Brunetean M. Partial chemical composition of Bambara pea (Vigna subterranean (L. verde). Food chemistry 2000; 68: 273-276. [CrossRef]

- Mohale C. K., Belane A. K. and Dakora F. D. Why is Bambara groundnut able to grow and fix N2 under contrasting soil conditions in different agroecologies? A presentation at the 3rd international scientific conference on neglected and underutilized species on 26th September, 2013 in Accra Ghana, 2013,13-16.

- Mshelia J. S., Sajo A. A. and Simon S.Y. The potentials of Bambara groundnut Voandzeia subterranean L. verde in achieving sustainable food security in Nigeria. Journal of science and multidisciplinary Research 2011; 4: 31- 35.

- Murphy, J. and Rilley J. P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural water. Analytical chemistry Acta 1962; 27:31-36. [CrossRef]

- Nwanna L. C., Enujiugha V. N., Oseni A. O. et al. Possible effect of fungal fermentation on Bambara groundnuts (Vigna subterranean (L. verde) as a feed stuff resource. Journal of Food Technology 2005; 3: 572- 575. [CrossRef]

- Ocran V. K., Delimini L. L., Asuboah R. A. and Asiedu E. A. Seed management manual for Ghana MOFA, Accra, Ghana, 1998, 1-15.

- Okpuzor J., Ogunugafor H.A., Okafor U. and Sofidiya M.O. Identification of protein types in Bambara nut seeds: perspective for dietary protein supply in developing countries. EXCL Journal 2010; 9: 17- 28.

- Onyango, B.O, Koech P. K, Anyango B, Nyunja R. A, Skilton R. A, Stomeo F. Morphological, genetic and symbiotic characterization of root nodule bacteria isolated from Bambara groundnuts (Vigna subterranea L. Verdc) from soils of Lake Victoria basin, western Kenya. J of App Bio and Biotech 2015; 3: 001-010.

- Roche, P., Fabienne M., Claire P., et al. The common nodABC genes of Rhizobium meliloti are host-range determinants. Proceedings.Natural Academy of Science USA 1996; 93: 15305–15310. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, C., Boistard P., Dénarié J., et al. Genes controlling early and late functions in symbiosis are located on a megaplasmid in Rhizobium meliloti. Molecolar and General Genetics 1981; 184: 326–333. [CrossRef]

- Schultze, M., Kondorosi E., Ratet P., Buiré M., Kondorosi A. Cell and molecular biologyn Rhizobium-plant interactions. International Reviews of Cytology 1994; 156: 1–74. [CrossRef]

- Spaink, H.P. Annual Reveiws of Phytopathology, 1995, 345–368.

- Sharpley, A.N. Assessing phosphorus bioavalability in agricultural soils and runoffs. Fertilizer Reviews 1993, 36, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasegaran, P. and H. J. Hoben Handbook for rhizobia: methods in legume-Rhizobium technology, Springer Science & Business Media, 2012, 1-504.

- Sprent J. I., Odee D. W and Dakora F. T. African legumes: A vital but under-utilized resource 2010; 61: 1257 – 1265.

- Tan X. L., Azam-Ali S., Ee V. G., et al. Bambara Groundnut: An Underutilized Leguminous Crop for Global Food Security and Nutrition. Frontiers in Nutrition 2020. [CrossRef]

- Tanimu B. S. A. and Aliyu LGnotypipic variability in bambara groundnut cultivers at Samaru In: proceeding of the 17th Annual Conference of the genetic society of Nigeria, 1990, 54- 56.

- Timmusk, S., Behers, L., Muthoni, J., Muraya, A., & Arronsson, A. C. Perspectives and challenges of microbial application for crop improvement. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017. [CrossRef]

- Uddling, J., Gelang-Alfredsson J., Piiki K., Pleijel H. Evaluating the relationship between leaf chlorophyll concentration and SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter readings. Photosynthesis Research. 2007; 91: 37-46. [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.M. A Manual for the Practical Study of Root Nodule Bacteria, Blackwell Scientific, Oxford,1970, 1-30.

- Vollmann, J., Walter H., Sato T. and Schweiger P. Digital image analysis and chlorophyll metering for phenotyping the effects of nodulation in soybean. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2011; 75: 190-195. [CrossRef]

- Woomer P. L., Karanja N. and Stanley M. A revised manual for rhizobium methods and standard protocols (www.n2africa.org), 2011, 1-45.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).