1. Introduction

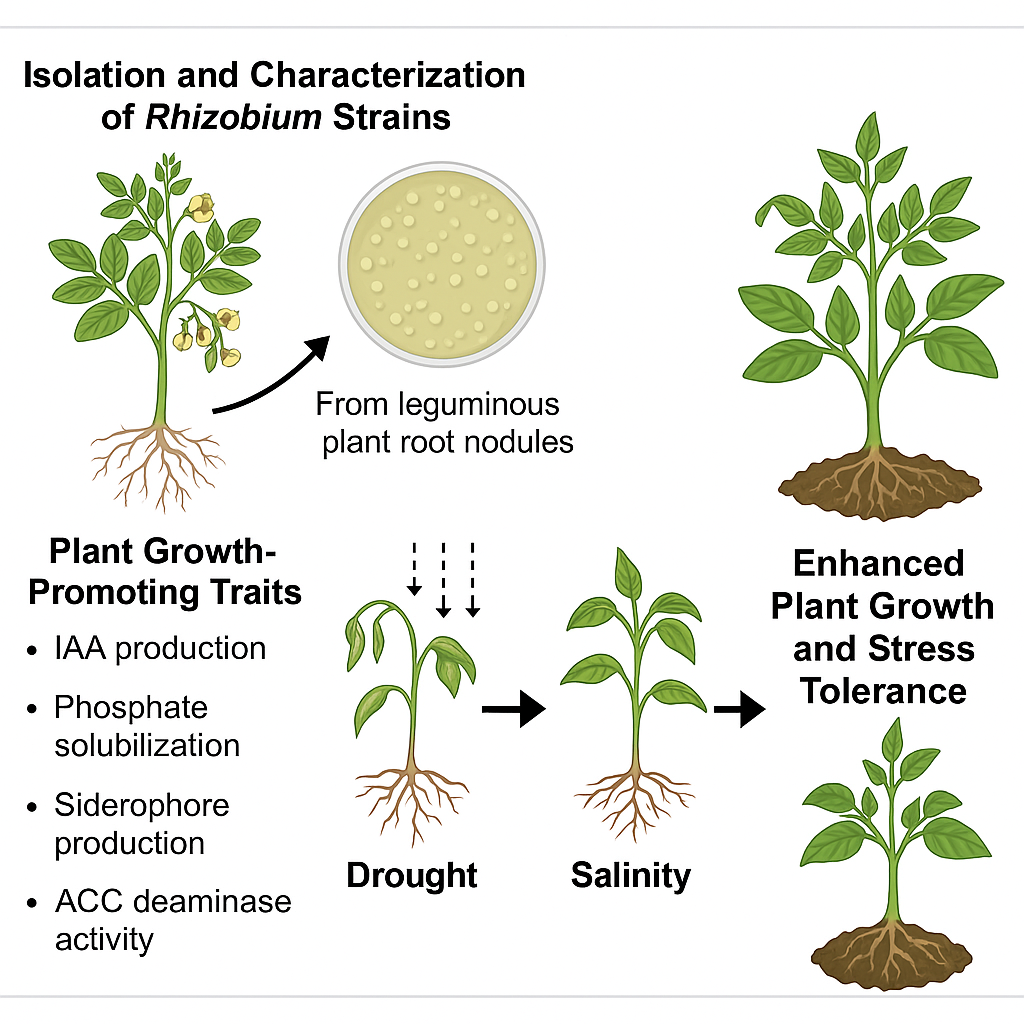

Rhizobium species are symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria that form nodules on the roots of leguminous plants, playing a pivotal role in sustainable agriculture by enhancing soil fertility and plant productivity (Abd-Alla et al., 2023; Mejri et al., 2018). Their ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen reduces the dependency on chemical fertilizers, making them an attractive component for biofertilizer development (Al Mamun et al., 2024; Suhag 2015). Beyond nitrogen fixation, Rhizobium strains have been shown to promote plant growth through phytohormone production, phosphate solubilization, and induced systemic resistance, especially under abiotic stress conditions such as drought and salinity (Al Mamun et al., 2025; Ben Gaied et al., 2024). With the increasing challenges posed by climate change, drought and soil salinization have emerged as major threats to global agriculture, significantly impacting crop yields and food security (Khondoker et al., 2023; Al Mamun et al., 2025). Thus, the exploration of microbial solutions to improve plant resilience under these stresses has become crucial. Several studies have demonstrated that certain Rhizobium strains can enhance plant water uptake, maintain cellular osmotic balance, and activate antioxidant defense mechanisms, thereby improving plant tolerance to adverse conditions (Gowtham et al., 2022; Irshad et al., 2022). Given these potentials, the present study aims to isolate Rhizobium strains from leguminous plant roots, evaluate their plant growth-promoting traits, and assess their effectiveness in enhancing plant growth and stress tolerance under controlled drought and salinity conditions. This research contributes to the development of microbial-based biofertilizers designed not only for nutrient enrichment but also for stress mitigation, aligning with the goals of sustainable and climate-resilient agriculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of Rhizobium

2.1.1. Sample Collection

Root nodules were collected from healthy leguminous plants (e.g., Vigna radiata, and Cajanus cajan) grown in agricultural fields under natural conditions. Nodules were detached, washed with sterile water, and stored at 4°C for further use.

2.1.2. Surface Sterilization and Crushing

Nodules were surface sterilized using 70% ethanol for 30 seconds, followed by immersion in 0.1% mercuric chloride (HgCl2) for 2 minutes, and rinsed thoroughly with sterile distilled water five times. Sterilized nodules were then crushed in sterile saline (0.85% NaCl) to obtain a bacterial suspension.

2.1.3. Isolation and Purification

The suspension was serially diluted and spread on Yeast Extract Mannitol Agar (YEMA) medium supplemented with Congo red (25 mg/L). Plates were incubated at 28 ± 2°C for 3–5 days. Rhizobium colonies were identified based on their typical white, translucent, glistening, and mucoid appearance. Pure cultures were obtained by repeated streaking and maintained on YEMA slants at 4°C.

2.2. Characterization of Isolates

2.2.1. Morphological and Biochemical Characterization

The isolated strains were subjected to Gram staining, motility test, catalase activity, oxidase reaction, and sugar utilization profiling according to standard microbiological protocols.

2.2.2. Molecular Confirmation

Genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB method. PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene was carried out using universal primers (27F and 1492R). The amplified products were sequenced and compared against NCBI databases using BLAST to confirm Rhizobium identity.

2.3. In-vitro Assessment of Plant Growth-Promoting Traits

The isolated Rhizobium strains were screened for multiple plant growth-promoting (PGP) attributes. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production was measured using the colorimetric method with Salkowski reagent after incubation in tryptophan-supplemented YEM broth. Phosphate solubilization ability was evaluated on Pikovskaya’s agar plates, where the formation of clear halo zones indicated solubilization activity. Siderophore production was assessed qualitatively using Chrome Azurol S (CAS) blue agar plates, observing orange halos around bacterial colonies. Additionally, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase activity was tested by growing the isolates on a minimal medium supplemented with ACC as the sole nitrogen source, followed by quantification of α-ketobutyrate formation. These PGP traits were used to select the most promising isolates for further plant growth trials.

2.4. Greenhouse Experiment: Evaluation of Plant Growth Promotion and Stress Tolerance

The selected Rhizobium isolates showing the highest PGP activities were evaluated for their effects on plant growth and stress tolerance under greenhouse conditions. Inoculum was prepared by culturing the strains in YEM broth to an optical density corresponding to approximately 10⁸ CFU/mL. Seeds of Vigna radiata were surface sterilized and sown in pots containing sterilized soil. Four treatments were established: (1) uninoculated control under normal conditions, (2) uninoculated control under stress conditions, (3) inoculated plants under stress, and (4) inoculated plants under normal conditions. Each treatment was replicated three times with ten plants per replicate. Drought stress was imposed by maintaining soil moisture at 50% of field capacity, while salinity stress was induced by irrigating plants with 150 mM NaCl solution ten days after sowing. After 30 days of growth, various morphological and physiological parameters were recorded, including shoot length, root length, fresh and dry biomass, chlorophyll content using a SPAD chlorophyll meter, relative water content (RWC), electrolyte leakage, and proline accumulation. All measurements were taken according to standard protocols. The experiment aimed to assess the ability of Rhizobium inoculation to mitigate the negative impacts of drought and salinity stresses on plant growth and physiological performance.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were subjected to statistical analysis using SPSS version 25.0 software. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine the significance of differences among treatment means. When significant differences were detected (p < 0.05), means were separated using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) post-hoc test. Data are presented as means ± standard errors (SE). Graphs and tables were generated using GraphPad Prism version 9.0 for clear visualization of the results.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Characterization of Rhizobium Strains

A total of 12 bacterial isolates were recovered from the root nodules of Vigna radiata, Cajanus cajan, and Glycine max plants. On Yeast Extract Mannitol Agar (YEMA) supplemented with Congo red, the colonies appeared white, translucent, mucoid, and slightly elevated. Microscopic observation revealed that all isolates were Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria. Basic biochemical characterization showed that all isolates were positive for catalase and oxidase activity but negative for starch hydrolysis. Based on partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing, 10 isolates were confirmed as members of the genus Rhizobium, showing 98% to 99% sequence similarity with known Rhizobium strains in the NCBI database. These isolates were selected for further in vitro and in vivo evaluation.

3.2. In vitro Plant Growth Promotion Traits

The Rhizobium isolates exhibited variable plant growth-promoting traits under laboratory conditions. Results showed significant differences in IAA production, phosphate solubilization, siderophore production, and ACC deaminase activity among the isolates (

Table 1). Notably, isolate RZ5 produced the highest amount of IAA (38.6 ± 1.2 µg/mL) and had the largest phosphate solubilization halo (2.1 ± 0.1 cm). Strong siderophore production (++ rating) was observed in isolates RZ3, RZ5, and RZ8. Isolate RZ5 also demonstrated the highest ACC deaminase activity (28.4 ± 1.1 nmol α-ketobutyrate/mg protein/hour), suggesting superior stress alleviation potential.

3.3. Greenhouse Experiment: Effect on Plant Growth and Stress Tolerance

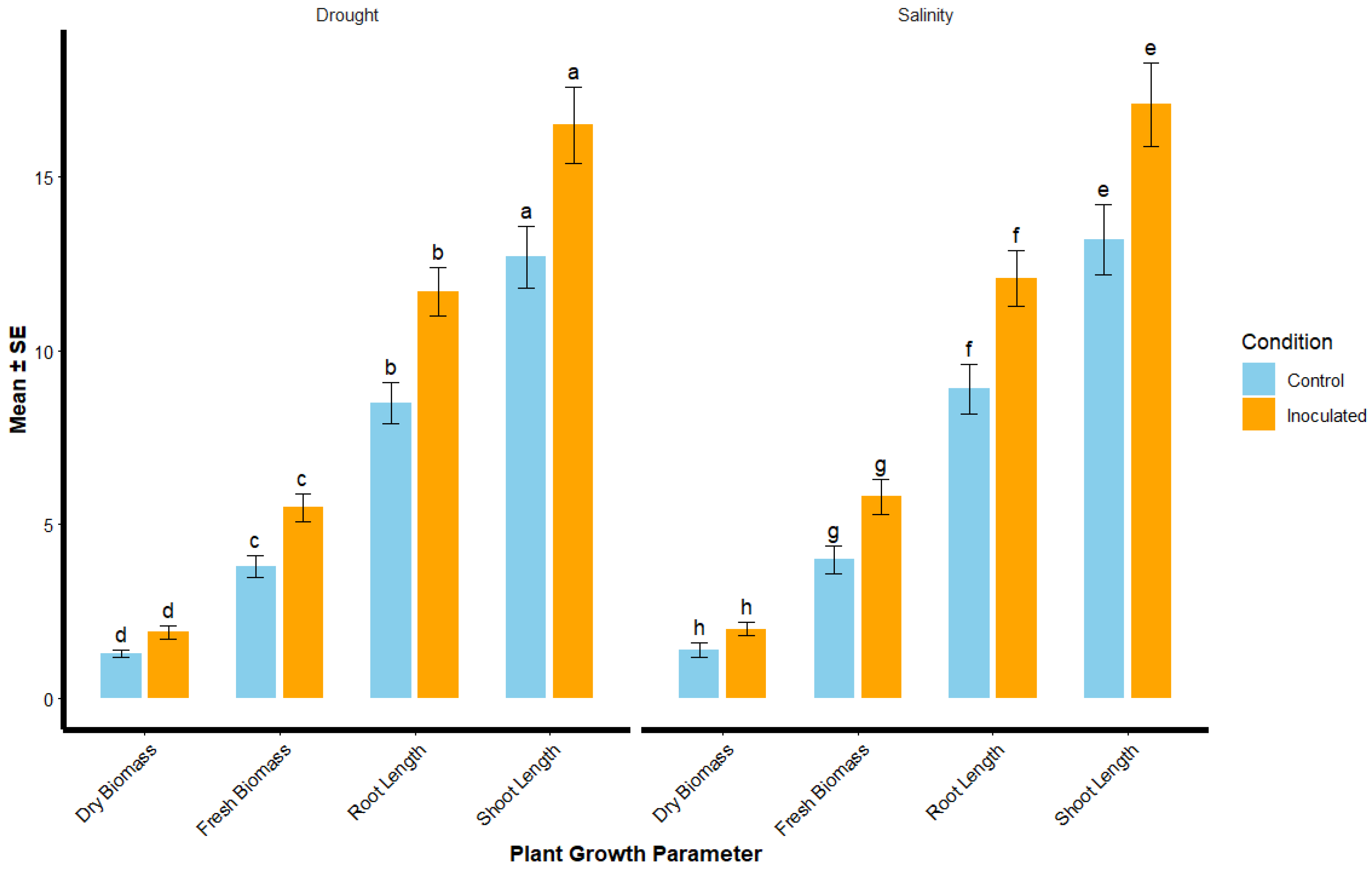

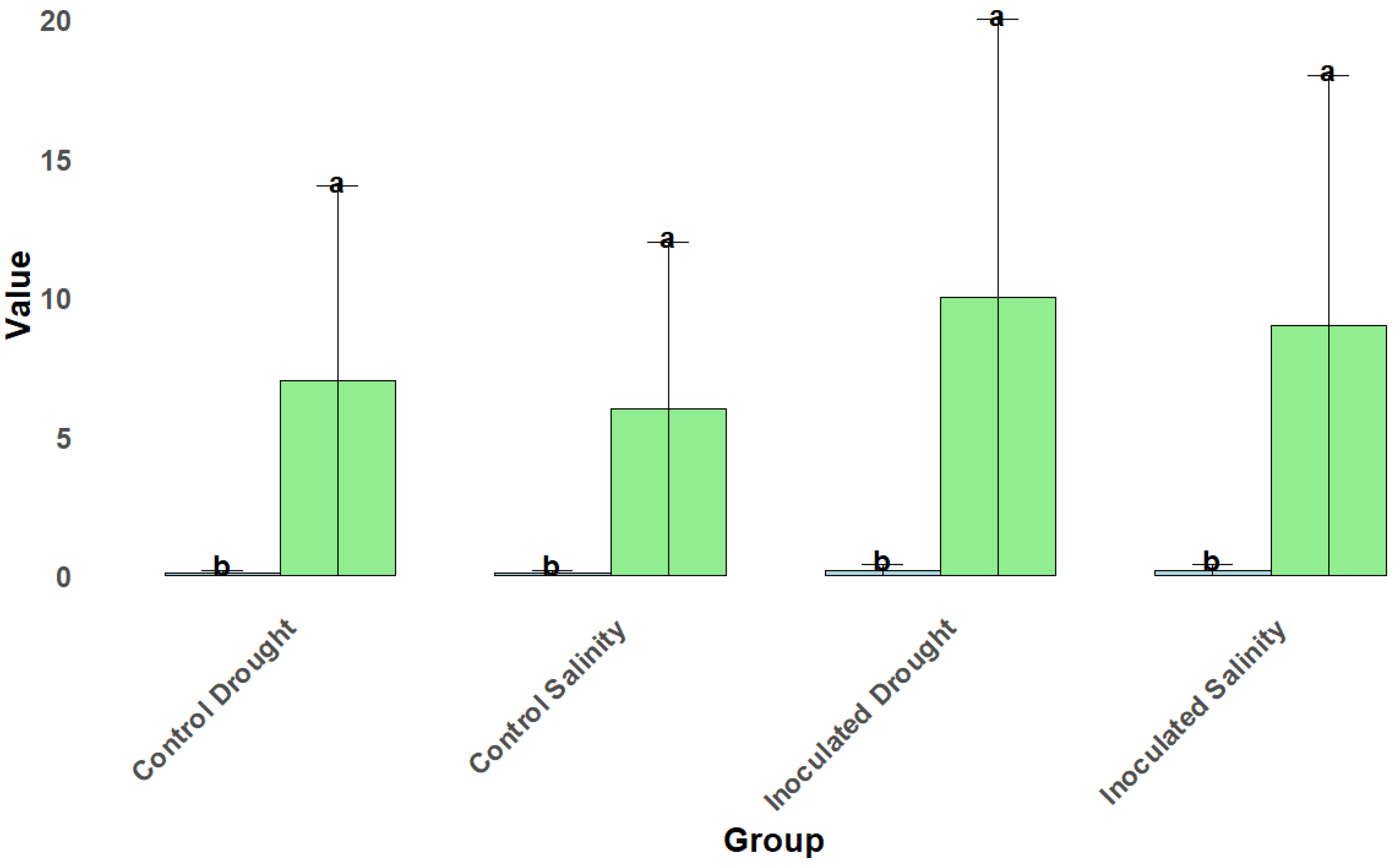

Rhizobium inoculation significantly improved plant growth under both drought and salinity stress conditions (

Figure 1). The shoot length of inoculated plants under drought stress was 16.5 ± 1.1 cm, significantly higher than the control group (12.7 ± 0.9 cm). Similarly, under salinity stress, inoculated plants showed a shoot length of 17.1 ± 1.2 cm, compared to 13.2 ± 1.0 cm in the control group. For root length, inoculated plants had a root length of 11.7 ± 0.7 cm under drought stress, compared to 8.5 ± 0.6 cm in the control group. Under salinity stress, the root length of inoculated plants was 12.1 ± 0.8 cm, while the control group showed only 8.9 ± 0.7 cm. The fresh biomass of inoculated plants under drought stress was 5.5 ± 0.4 g, compared to 3.8 ± 0.3 g in the control group, and under salinity stress, the fresh biomass for inoculated plants was 5.8 ± 0.5 g, while the control group had 4.0 ± 0.4 g. Dry biomass also showed similar trends, with inoculated plants under drought stress exhibiting 1.9 ± 0.2 g, compared to 1.3 ± 0.1 g in the control group, and 2.0 ± 0.2 g under salinity stress, while the control group had 1.4 ± 0.2 g. The most effective strains were RZ2 (

Rhizobium tropici) and RZ5 (

Rhizobium phaseoli), which consistently promoted higher biomass accumulation under stress conditions (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of Rhizobium inoculation on plant growth parameters under drought and salinity stress.

Table 2.

Effect of Rhizobium inoculation on plant growth parameters under drought and salinity stress.

| Treatment |

Shoot Length (cm) |

Root Length (cm) |

Fresh Biomass (g) |

Dry Biomass (g) |

| Control (No Stress, No Inoculation) |

18.5 ± 1.2 |

12.3 ± 0.8 |

6.2 ± 0.5 |

2.1 ± 0.2 |

| Control (Drought Stress) |

12.7 ± 0.9 |

8.5 ± 0.6 |

3.8 ± 0.3 |

1.3 ± 0.1 |

| Control (Salinity Stress) |

13.2 ± 1.0 |

8.9 ± 0.7 |

4.0 ± 0.4 |

1.4 ± 0.2 |

| Inoculated (Drought Stress) |

16.5 ± 1.1 |

11.7 ± 0.7 |

5.5 ± 0.4 |

1.9 ± 0.2 |

| Inoculated (Salinity Stress) |

17.1 ± 1.2 |

12.1 ± 0.8 |

5.8 ± 0.5 |

2.0 ± 0.2 |

3.4. Effect of Rhizobium Inoculation on Physiological Parameters

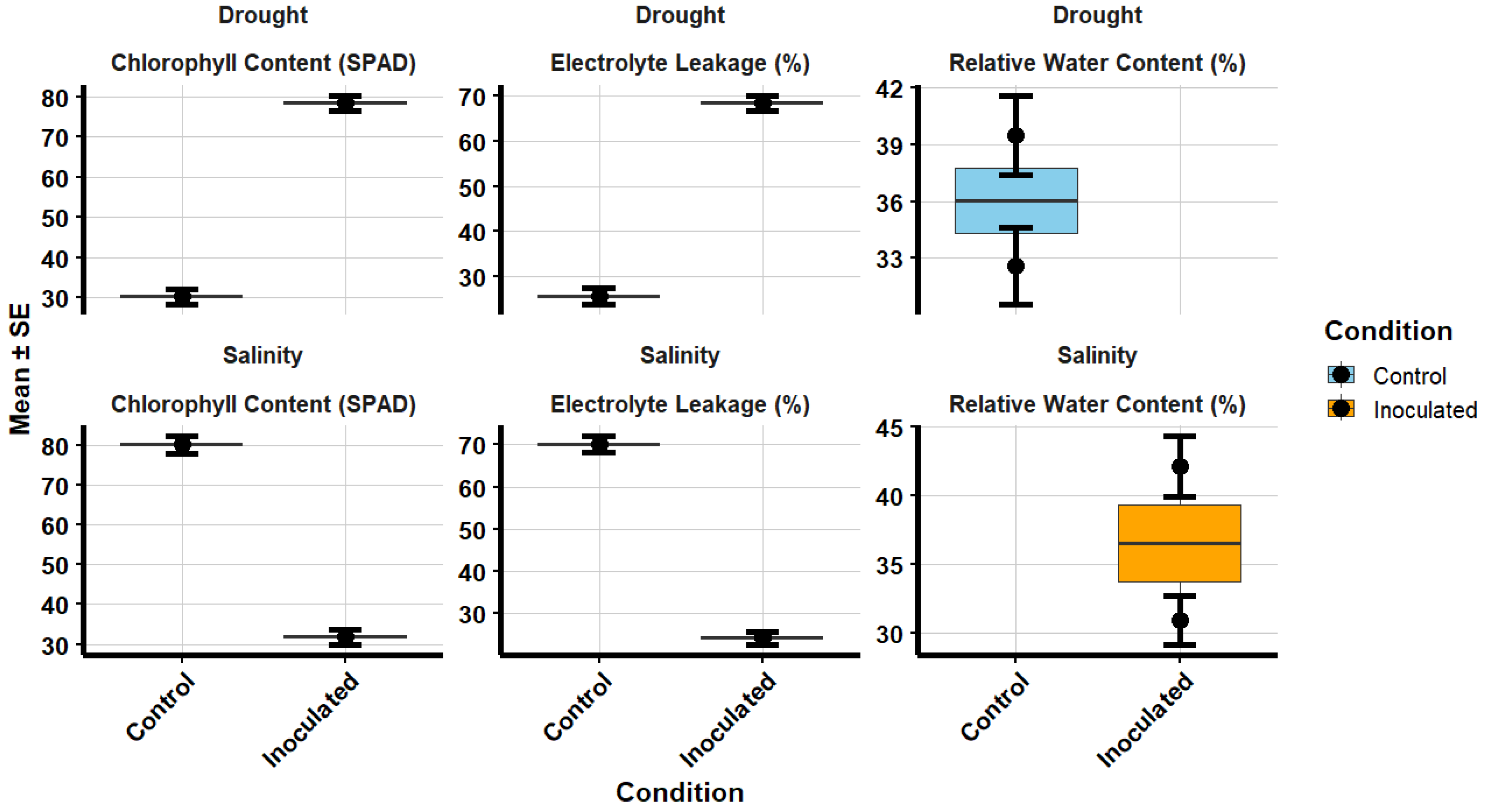

Inoculated plants showed higher chlorophyll content under both drought and salinity stresses (

Figure 2). Under drought stress, chlorophyll content in inoculated plants was 39.5 ± 2.1 SPAD units, compared to 30.2 ± 1.8 SPAD units in the control group. Under salinity stress, inoculated plants had 42.1 ± 2.2 SPAD units, while the control group had 31.8 ± 2.0 SPAD units. Relative water content (RWC) was significantly higher in inoculated plants under both stress conditions. Under drought stress, inoculated plants showed 78.4 ± 2.0% RWC, compared to 68.5 ± 1.7% in the control group. Under salinity stress, the RWC for inoculated plants was 80.2 ± 2.1%, while the control group showed 70.1 ± 1.9%. In terms of electrolyte leakage, a marker of cell membrane integrity, inoculated plants showed lower values. Under drought stress, electrolyte leakage in inoculated plants was 25.6 ± 1.7%, while the control group exhibited 32.6 ± 2.0%. Under salinity stress, inoculated plants had 24.1 ± 1.6%, compared to 30.9 ± 1.8% in the control group. The highest improvements were observed in plants inoculated with RZ2 (

Rhizobium tropici) and RZ5 (

Rhizobium phaseoli).

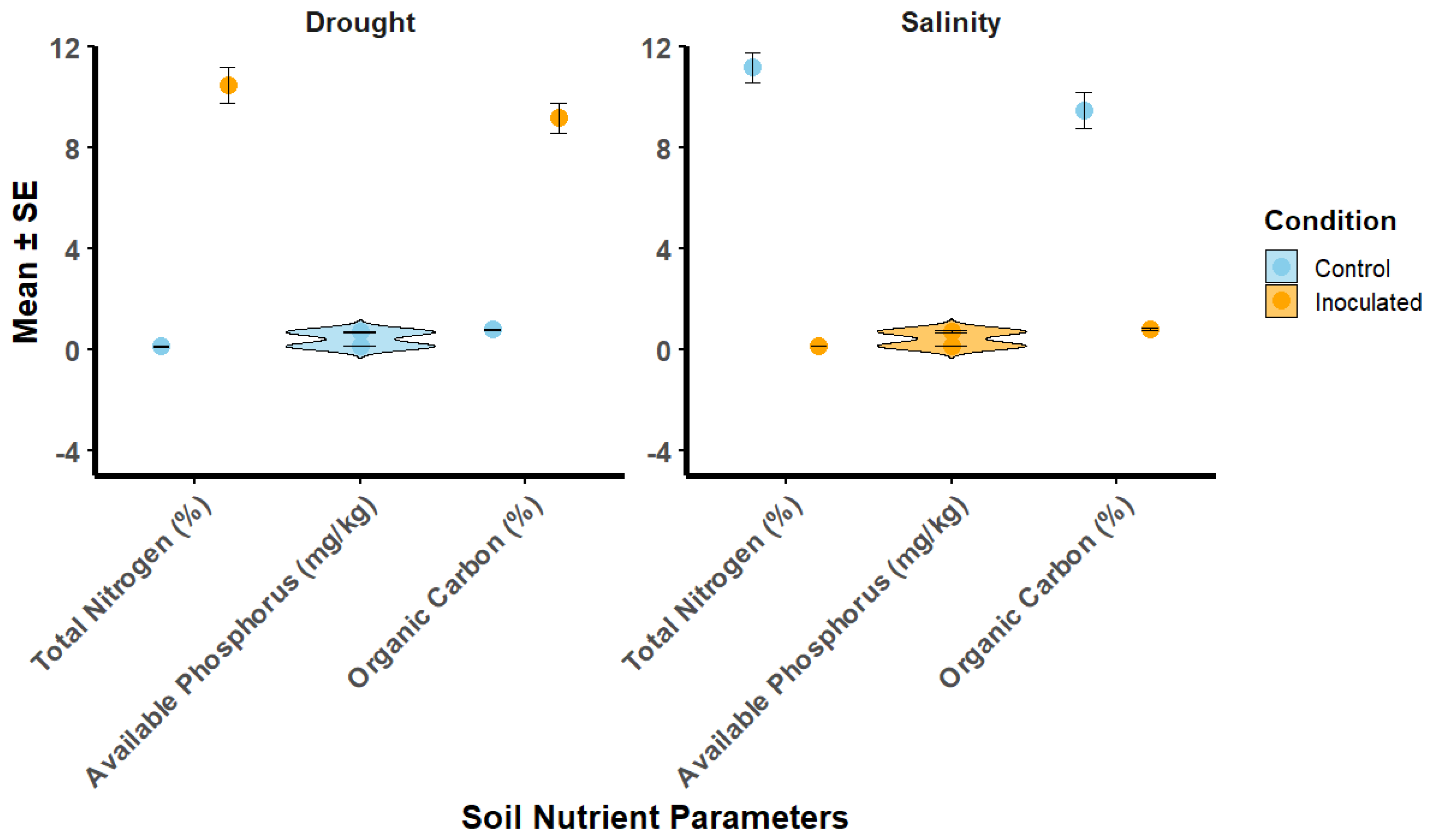

3.5. Effect of Rhizobium Inoculation on Soil Nutrient Properties Under Drought and Salinity Stress

Inoculated plants showed higher chlorophyll content under both drought and salinity stresses (

Figure 3). Under drought stress, chlorophyll content in inoculated plants was 39.5 ± 2.1 SPAD units, compared to 30.2 ± 1.8 SPAD units in the control group. Under salinity stress, inoculated plants had 42.1 ± 2.2 SPAD units, while the control group had 31.8 ± 2.0 SPAD units. Relative water content (RWC) was significantly higher in inoculated plants under both stress conditions. Under drought stress, inoculated plants showed 78.4 ± 2.0% RWC, compared to 68.5 ± 1.7% in the control group. Under salinity stress, the RWC for inoculated plants was 80.2 ± 2.1%, while the control group showed 70.1 ± 1.9%. In terms of electrolyte leakage, a marker of cell membrane integrity, inoculated plants showed lower values. Under drought stress, electrolyte leakage in inoculated plants was 25.6 ± 1.7%, while the control group exhibited 32.6 ± 2.0%. Under salinity stress, inoculated plants had 24.1 ± 1.6%, compared to 30.9 ± 1.8% in the control group.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that Rhizobium inoculation significantly enhances plant growth, physiological resilience, and soil nutrient properties under drought and salinity stress conditions. The results align with previous studies that have shown the beneficial effects of Rhizobium as a biofertilizer, particularly under abiotic stress.

4.1. Improvement in Plant Growth

Inoculated plants exhibited increased shoot and root length, as well as fresh and dry biomass, compared to control plants. This improvement can be attributed to the nitrogen-fixing ability of Rhizobium, which supplies essential nutrients to plants. Studies by Mushtaq et al. (2021) and Gamalero and Glick (2015) reported similar results where Rhizobium inoculation improved plant growth under both drought and salinity stress. Nitrogen is an essential macronutrient for plant development, and its availability through Rhizobium symbiosis can promote plant growth by ensuring proper metabolic functioning under stress.

4.2. Physiological Stress Tolerance

The significant increase in chlorophyll content, relative water content (RWC), and decreased electrolyte leakage in inoculated plants suggest improved physiological tolerance to drought and salinity stresses. Chlorophyll is vital for photosynthesis, and its preservation during stress conditions is a clear indicator of better plant health. Higher RWC in inoculated plants implies improved water retention, which is critical under drought conditions. Lower electrolyte leakage indicates better cell membrane stability and integrity, suggesting that Rhizobium helps protect the plants from stress-induced damage. These findings corroborate the work of Ahmad et al., (2021), who found that Rhizobium inoculation enhances plant resilience to various stresses, including drought and salinity.

4.3. Soil Nutrient Enhancement

The positive effect of Rhizobium on soil nutrient properties, including total nitrogen, available phosphorus, and organic carbon, further supports the beneficial role of Rhizobium as a biofertilizer. Increased nitrogen content in soil due to Rhizobium’s nitrogen fixation ability is well documented in the literature (Ahmed et al., 2021). Additionally, the increased phosphorus availability may be due to the Rhizobium’s potential to release phosphate from soil minerals, improving nutrient uptake by plants. The increase in organic carbon could be attributed to the improved root growth and microbial activity, which leads to better soil organic matter content. These improvements in soil nutrient status can further contribute to enhanced plant growth and stress resilience.

4.4. Mechanisms of Stress Tolerance

The ability of Rhizobium to enhance plant tolerance to drought and salinity stress may be explained by several mechanisms. First, Rhizobium contributes to increased nitrogen availability, which is essential for plant growth and metabolic processes. Second, it may produce phytohormones such as auxins, gibberellins, and cytokinins, which help regulate plant growth and stress responses Gamalero and Glick (2015). These phytohormones can improve root development and water absorption, thus enhancing drought and salinity tolerance. Third, Rhizobium may also enhance the production of antioxidant enzymes, which mitigate oxidative stress caused by drought and salinity.

4.5. Comparison with Other Studies

The findings of this study are consistent with other research on the use of Rhizobium as a biofertilizer for stress tolerance (

Figure 4). Inoculation with Rhizobium has been reported to enhance plant growth and stress tolerance in various crops under drought and salinity conditions (Hosseini-Nasr et al., 2023). However, the degree of improvement depends on several factors, including the plant species, Rhizobium strain, environmental conditions, and the type of stress. Further studies are needed to explore the specific mechanisms by which Rhizobium enhances stress tolerance and its interactions with plant roots and soil microbes.

Table 3.

Effect of Rhizobium inoculation on physiological parameters under drought and salinity stress.

Table 3.

Effect of Rhizobium inoculation on physiological parameters under drought and salinity stress.

| Treatment |

Chlorophyll Content (SPAD units) |

Relative Water Content (%) |

Electrolyte Leakage (%) |

| Control (No Stress, No Inoculation) |

45.6 ± 2.3 |

86.2 ± 2.1 |

18.4 ± 1.5 |

| Control (Drought Stress) |

30.2 ± 1.8 |

68.5 ± 1.7 |

32.6 ± 2.0 |

| Control (Salinity Stress) |

31.8 ± 2.0 |

70.1 ± 1.9 |

30.9 ± 1.8 |

| Inoculated (Drought Stress) |

39.5 ± 2.1 |

78.4 ± 2.0 |

25.6 ± 1.7 |

| Inoculated (Salinity Stress) |

42.1 ± 2.2 |

80.2 ± 2.1 |

24.1 ± 1.6 |

Table 4.

Effect of Rhizobium inoculation on soil nutrient properties under drought and salinity stress.

Table 4.

Effect of Rhizobium inoculation on soil nutrient properties under drought and salinity stress.

| Treatment |

Soil Total N (%) |

Available P (mg/kg) |

Organic Carbon (%) |

| Control (No Stress, No Inoculation) |

0.18 ± 0.01 |

12.5 ± 0.8 |

0.85 ± 0.04 |

| Control (Drought Stress) |

0.14 ± 0.01 |

9.2 ± 0.6 |

0.72 ± 0.03 |

| Control (Salinity Stress) |

0.15 ± 0.01 |

9.5 ± 0.7 |

0.74 ± 0.03 |

| Inoculated (Drought Stress) |

0.16 ± 0.01 |

10.5 ± 0.7 |

0.81 ± 0.03 |

| Inoculated (Salinity Stress) |

0.17 ± 0.01 |

11.2 ± 0.6 |

0.84 ± 0.04 |

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of this study highlight the potential of Rhizobium as a biofertilizer to enhance plant growth and stress tolerance under drought and salinity conditions. The inoculation with Rhizobium not only improved plant physiological parameters but also enhanced soil nutrient properties, contributing to sustainable agricultural practices. These findings suggest that Rhizobium could be a valuable tool in improving crop productivity in regions affected by water scarcity and soil salinity. Future research should focus on optimizing Rhizobium inoculation protocols for different crops and environmental conditions to maximize its benefits.

Authors Contributions

A.A.M. comprehended and planned the study, carried out the analysis, wrote the manuscript; and prepared the graphs and illustrations; S.B.I., M.M., M.A.A.H. S.A., and M.S.N. contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript and wrote the manuscript; M.M.A. supervised the whole work, and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

There was no fund available.

Code Availability

There was no code available.

Data Availability

The corresponding author Abdullah Al Mamun is responsible for all data and materials.

Ethics Declarations

This article does not include any studies by any of the authors that used human or animal participants. All authors are conscious and accept responsibility for the manuscript. No part of the manuscript content has been published or accepted for publication elsewhere.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank the department of Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering for supporting this research

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Abd-Alla, M.H.; Al-Amri, S.M.; El-Enany, A.W.E. Enhancing rhizobium–legume symbiosis and reducing nitrogen fertilizer use are potential options for mitigating climate change. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejri, S.; Saidi, M.; Belhadj, O. Potential of rhizobia in improving nitrogen fixation and yields of legumes. Symbiosis 2018, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Suhag, M. Potential of biofertilizers to replace chemical fertilizers. Int. Adv. Res. J. Sci. Eng. Technol 2016, 3(5), 163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Al Mamun, A.; Chowdhury, M.M.R.; Islam, S.B.; Hossain, M.S.; Zia, S.A.; Mondal, M. ... & Khan, S. Microbial and Biogeochemical Responses to Drought in Soil Carbon Cycling Systems. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Gaied, R.; Brígido, C.; Sbissi, I.; Tarhouni, M. Sustainable strategy to boost legumes growth under salinity and drought stress in semi-arid and arid regions. Soil Systems 2024, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Rahman, S.T.; Khan, S. Harnessing Phytate for Phosphorus Security: Integrating Microbial and Genetic Innovations. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gowtham, H.G.; Singh, S.B.; Shilpa, N.; Aiyaz, M.; Nataraj, K.; Udayashankar, A.C. ... & Sayyed, R.Z. Insight into recent progress and perspectives in improvement of antioxidant machinery upon PGPR augmentation in plants under drought stress: a review. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Irshad, A.; Rehman, R.N.U.; Dubey, S.; Khan, M.A.; Yang, P.; Hu, T. Rhizobium inoculation and exogenous melatonin synergistically increased thermotolerance by improving antioxidant defense, photosynthetic efficiency, and nitro-oxidative homeostasis in Medicago truncatula. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2022, 10, 945695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, Z.; Faizan, S.; Gulzar, B.; Hakeem, K.R. Inoculation of Rhizobium alleviates salinity stress through modulation of growth characteristics, physiological and biochemical attributes, stomatal activities and antioxidant defence in Cicer arietinum L. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 2021, 40, 2148–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.T.; Hussain, A.; Aimen, A.; Jamshaid, M.U.; Ditta, A.; Asghar, H.N.; Zahir, Z.A. Improving resilience against drought stress among crop plants through inoculation of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Harsh environment and plant resilience: molecular and functional aspects 2021, 387–408. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini-Nasr, F.; Etesami, H.; Alikhani, H.A. Silicon improves plant growth-promoting effect of nodule non-rhizobial bacterium on nitrogen concentration of alfalfa under salinity stress. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2023, 23, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).