1. Introduction

The utilization of artificial intelligence (AI) has become a dominant trend across all sectors of science and industry, revolutionizing how information is processed, data are analyzed, and decisions are made. In the domain of scientific research, AI significantly accelerates technological advancement by offering tools for automating laboratory workflows, creating advanced simulations of complex systems, and efficiently processing and analyzing vast datasets [

1]. Particularly rapid progress has been observed in Large Language Models (LLMs) such as the GPT and T5 families, which—through their capacity to understand, generate, and process natural language—are redefining the boundaries of human–machine interaction and opening new avenues for innovative applications.

In the context of autonomous and swarm navigation systems, traditional approaches often rely on predefined algorithms and limited environmental perception, which can lead to suboptimal decision-making in complex or unpredictable scenarios. The key challenge lies in creating systems capable of open-world exploration and context-aware reasoning, where decisions are driven by high-level cognition rather than direct sensory readings alone [

2,

3].

Autonomous navigation has historically depended on modular pipelines that couple engineered perception with rule-based planning and control. Recent advances in multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) suggest an alternative paradigm in which a single foundation model integrates visual perception and linguistic reasoning to synthesize action proposals. This study examines that paradigm through the development of a vision-guided mobile robot, demonstrating how such models can be deployed effectively under real-time and computational constraints.

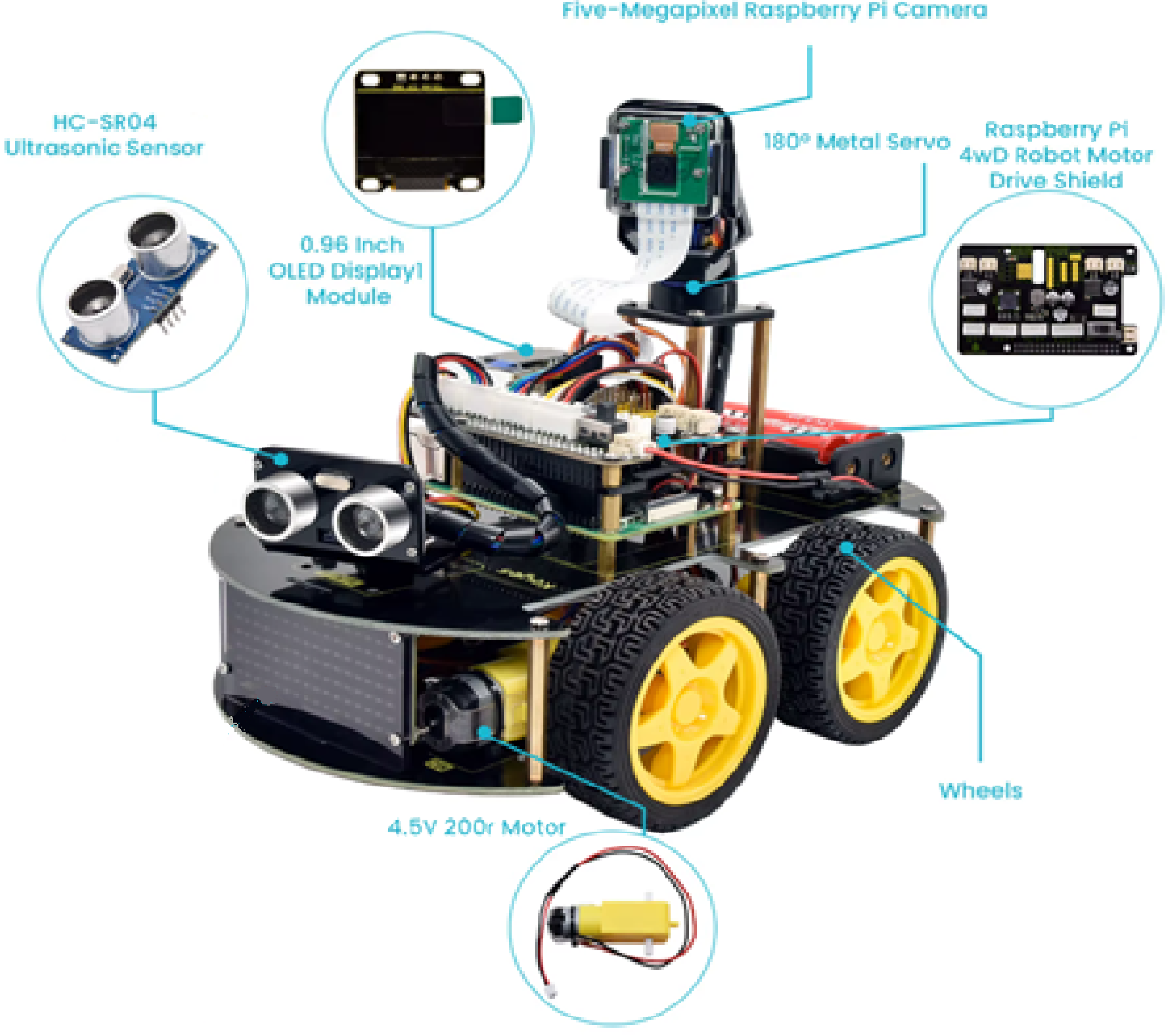

Our prototype system comprises a Raspberry Pi–based robot equipped with a front-facing camera and distance sensor, connected to a host workstation running a customized instance of LLaVA-7B (Large Language and Vision Assistant) via the Ollama runtime. The LLM functions as a central cognitive unit, processing each captured image and sensor reading to generate (i) a concise situational description and (ii) a structured JSON command defining motion, speed, turn angle, and duration. The Raspberry Pi performs data acquisition and motor actuation, while the host executes inference. Communication between these modules employs a hybrid architecture: REST API for telemetry transmission (Robot → Server) and persistent TCP sockets for real-time control (Server → Robot), balancing throughput, determinism, and implementation simplicity.

Rather than relying on resource-intensive fine-tuning, we apply advanced prompt engineering with a strengthened system prompt and strict output validation, complemented by a semantic safety layer on the robot that clamps or rejects unsafe commands. This design ensures both interpretability and operational safety when interacting with nondeterministic generative models.

The objectives of this research are threefold: (1) to evaluate whether a compact multimodal LLM can consistently translate real-world visual and sensor input into semantically valid control directives; (2) to analyze the engineering trade-offs of a client–server architecture for real-time robotic control loops; and (3) to establish safety principles and practical guardrails for LLM-driven decision systems in embodied robotics. Moreover, this framework provides the foundation for future swarm navigation systems, in which multiple AI-driven agents coordinate through shared multimodal understanding and distributed reasoning [

4].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Overview

We evaluate a client–server architecture that employs a multimodal Large Language Model (LLM) as a cognitive controller for a vision-guided mobile robot. The edge unit is a Raspberry Pi 4 that acquires images and range data and actuates motors with local safety supervision, while the main server runs a customized instance of LLaVA–7B via the Ollama runtime. For each perception cycle the model returns a one-sentence scene description and a structured JSON command which is validated and executed on-board. REST API (Robot → Server) is used for telemetry, whereas a persistent TCP socket (Server → Robot) is used for low-latency control.

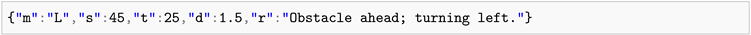

2.2. Robot Hardware Setup (Raspberry Pi 4)

The platform is built on a 4WD chassis with differential drive. The main on-board controller is a Raspberry Pi 4 Model B (4 GB RAM). Key modules:

Five-megapixel Raspberry Pi Camera on a 180∘ metal servo (active viewpoint control).

HC-SR04 ultrasonic sensor (proximity and emergency stop).

4WD motor driver shield for PWM speed/steering, four V 200 rpm DC motors.

0.96 in OLED display and 8×16 LED matrix (diagnostics/status).

Dual 18650 battery pack with DC–DC regulation (separate rails for logic and motors).

Table 1.

Hardware specifications of the experimental robot.

Table 1.

Hardware specifications of the experimental robot.

| Component |

Model / Module |

Purpose |

| On-board computer |

Raspberry Pi 4 Model B (4 GB) |

Handles edge-level control, sensor data acquisition, local safety supervision, and communication with the main LLaVA inference server. |

| Camera |

RPi 5 MP with

180∘ servo mount |

Provides real-time visual input and adjustable viewpoint for scene exploration. |

| Range sensor |

HC-SR04 ultrasonic sensor |

Measures obstacle distance and triggers safety stop when the threshold is below

m. |

| Drive system |

4WD motor driver shield + 4× DC

V

200

rpm motors |

Controls differential steering and speed using PWM signals. |

| Displays |

0.96 in OLED + 8×16 LED matrix |

Displays connection mode, debug data, and system status feedback. |

| Power supply |

2×18650 Li-Ion cells + DC–DC regulators |

Provides stabilized and isolated voltage for logic and motor subsystems. |

2.3. Software Environment and Model Configuration

The reasoning engine is a customized LLaVA–7B (llava-custom) executed with ollama run on the server. No full fine-tuning was performed; instead, we used prompt engineering and context control to ensure consistent outputs.

Type: multimodal (image + text).

Output: one sentence (scene description) + JSON command.

Typical options: temperature 0.2, top-p 0.9, context 4096.

Baselines tested: Llama3 (text-only); larger LLaVA/Llama3 variants (replaced due to memory/latency).

Two other models were tested for comparison:

Llama3 (text-only baseline) – provided contextual reasoning but lacked vision input.

LLaVA and Llama3 full-size variants – offered improved reasoning but were discarded due to excessive memory usage and latency.

Given the satisfactory zero-shot performance of LLaVA-7B, no explicit fine-tuning (FT) was performed. Instead, prompt engineering (PE) and context management were applied to ensure consistent reasoning and deterministic JSON output.

2.4. Prompt Engineering

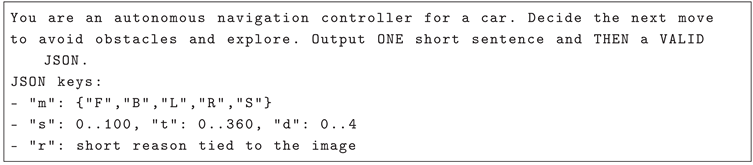

The model is instructed to act as an autonomous navigator. A shortened system prompt is shown below; the user prompt is composed dynamically with the latest image, range measurement and previous command/history.

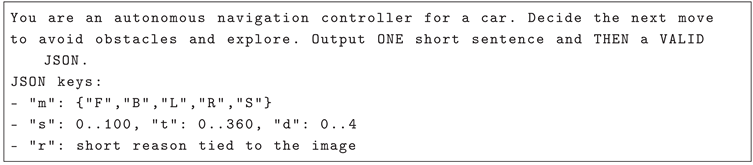

Listing 1: System prompt (excerpt) and required JSON keys.

Communication Protocol

Robot → Server (REST, port 5053).

Telemetry with image and context is posted as multipart/form-data. The server replies with a validated decision.

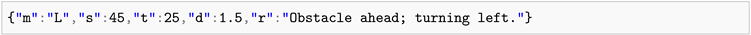

Listing 2: Example decision JSON returned by the server.

Server → Robot (TCP socket).

A persistent connection streams control/messages (e.g., DirForward, DirStop, CamLeft, TakePhoto) with optional history and prompt hints. Robot returns ACKs. Heartbeats monitor liveness.

2.5. Safety and Validation

Every model output is schema-validated; the on-board semantic guard clamps , , , and rejects unknown . Range thresholds enforce immediate Stop when .

2.6. Experimental Procedure and Metrics

Trials were conducted in a controlled indoor arena. Each loop: capture (image, range) → transmit → infer (LLaVA) → validate → actuate → log. We record: (i) end-to-end latency, (ii) JSON validity rate, (iii) safety events (collisions/near-misses), and (iv) qualitative reasoning consistency (alignment of “r” with the scene).

Figure 1.

Experimental platform: Raspberry Pi 4–based 4WD robot with camera on a 180∘ servo, HC-SR04 range sensor, motor driver shield, OLED and LED displays.

Figure 1.

Experimental platform: Raspberry Pi 4–based 4WD robot with camera on a 180∘ servo, HC-SR04 range sensor, motor driver shield, OLED and LED displays.

Figure 2.

System architecture: REST (Robot→Server) for telemetry and TCP socket (Server→Robot) for real-time control. LLaVA–7B (Ollama) returns sentence+JSON ; outputs are validated and clamped on-board.

Figure 2.

System architecture: REST (Robot→Server) for telemetry and TCP socket (Server→Robot) for real-time control. LLaVA–7B (Ollama) returns sentence+JSON ; outputs are validated and clamped on-board.

3. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Procedure

The primary objective of the experimental campaign was to evaluate the effectiveness of Large Language Models (LLMs)—particularly multimodal variants—in controlling autonomous navigation of a mobile robot based on real-time visual and sensor inputs. The experiment compared several model configurations within an identical robotic environment, assessing their ability to interpret camera imagery, recognize environmental elements, and generate appropriate movement commands under latency and safety constraints.

3.1. Tested Models

Three model configurations were evaluated under identical conditions:

LLaVA:7B (llava-custom) — multimodal vision-language model deployed via the Ollama runtime, capable of processing both text and image inputs [

5,

6].

LLaVA (standard 7B) — reference model with baseline prompt and system configuration [

7] .

Llama3 (text-only) — baseline for reasoning quality without visual input [

8,

9].

Each model was prompted to act as a navigation controller and to produce output in the form of one descriptive sentence followed by a valid JSON object encoding motion parameters:

where

denotes direction (Forward, Backward, Left, Right, Stop),

s represents speed (%),

t is the turn angle (°),

d denotes duration (s), and

r provides a textual justification of the decision.

Experimental Procedure

Each experimental trial followed an identical closed-loop sequence illustrated below:

Image acquisition: The Raspberry Pi 4 captured a frame from the front camera and the current distance from the ultrasonic sensor.

Feature extraction: Lightweight edge-detection and object-localization routines identified elements such as walls, openings, or obstacles. The detected features (e.g., “obstacle front-left”) were encoded as text tokens and included in the model prompt.

Inference via LLM: The chosen model (LLaVA or Llama3) received the symbolic description and, where applicable, the raw image. It generated a scene description and a JSON-formatted command defining motion parameters.

Command validation and execution: The Raspberry Pi validated the JSON output against a schema and clamped values (, , ). Safe commands were then executed.

Safety override: The ultrasonic distance sensor acted as a final safety layer; if the measured distance dropped below m, an emergency “Stop” command was triggered.

Logging and feedback: Each step—image, JSON command, reasoning text, and execution result—was logged for quantitative and qualitative analysis.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

For each tested model, we measured:

Inference latency (ms) — time between image capture and command execution.

JSON validity rate (%) — share of syntactically correct control outputs.

Decision coherence (%) — proportion of textual reasonings consistent with visual context.

Collision avoidance rate (%) — fraction of cycles completed without triggering the safety override.

Motion smoothness (%) — ratio of planned to corrective (stop/reverse) actions.

3.3. Experimental Environment

All experiments were conducted in a real-world lecture hall environment rather than a controlled laboratory arena. The test area measured approximately 6x4 m and contained naturally occurring obstacles such as tables, chairs, backpacks, and groups of students present in the room. This dynamic and semi-structured setting was chosen to evaluate the robot’s ability to navigate among everyday objects and people, reflecting realistic challenges for autonomous exploration.

The robot’s primary objective during trials was environmental exploration: to move continuously through the space, avoid collisions, and dynamically select paths between obstacles while maintaining safe distances from humans and static objects. Lighting and acoustic conditions were typical of an active classroom, with ambient noise and variable visual backgrounds. Each model completed ten autonomous navigation cycles per trial. Human involvement was limited to initialization and observation, without manual correction of the robot’s trajectory.

3.4. Ethical and Safety Considerations

Because the experiments were conducted in a space occupied by students, specific safety and ethical measures were implemented to ensure that the study adhered to responsible research practices. All participants present in the lecture hall were informed about the nature and purpose of the experiment, and their presence was voluntary. The mobile robot operated at a low maximum speed of m/s, well below any threshold that could cause harm, and its movement was continuously monitored by the supervising researcher.

A dedicated safety layer was active at all times: the ultrasonic distance sensor triggered an immediate Stop command whenever an object or person was detected within 25 cm of the robot’s front. In addition, the onboard controller maintained a “dead-man” mechanism capable of halting all motion upon communication loss or abnormal command detection.

No direct human–robot contact occurred during the trials, and the environment remained open for normal classroom activity. These precautions ensured the ethical and physical safety of all participants while maintaining the ecological validity of the experiment in a real social context.

3.5. Results Summary

Table 2 summarizes the quantitative outcomes of the experimental evaluation. The

LLaVA:7B-custom model achieved the highest JSON validity and reasoning coherence while maintaining safe operation in all runs. The

text-only Llama3 baseline demonstrated acceptable reasoning but required frequent safety interventions due to its lack of visual grounding.

Preliminary Observations

The results confirm that multimodal reasoning significantly improves spatial awareness and action consistency. The customized LLaVA model maintained a low-latency control loop (<200 ms) and produced structured, semantically grounded commands. The text-only baseline, lacking visual context, tended to issue overconfident or contextually inconsistent decisions, often prevented from collisions only by the local safety guard. These findings validate the proposed client–server architecture and highlight the feasibility of deploying multimodal LLMs for real-time robotic navigation.

4. Results and Discussion

The experimental results confirm that employing Large Language Models (LLMs) and multimodal Vision-Language Models (VLMs) as cognitive controllers for mobile robots is a viable and effective approach to autonomous navigation. Across all test scenarios, the LLaVA:7B-custom model consistently produced coherent, valid, and contextually grounded control commands, enabling the robot to move autonomously and safely within the lecture hall environment.

4.1. Performance and Decision Quality

Deploying the LLM on the main server, rather than directly on the embedded device, proved crucial for achieving real-time performance. The client–server architecture allowed the Raspberry Pi 4 to focus on rapid data acquisition—capturing images and sensor readings at up to several frames per second—while the computationally intensive reasoning was executed on the host workstation running Ollama with the LLaVA model. This design reduced the average control latency below 200 ms, which is sufficient for smooth motion and responsive obstacle avoidance.

The robot was able to interpret complex classroom scenes containing tables, chairs, backpacks, and moving students. The multimodal model reliably identified navigable spaces and generated sequential motion plans rather than isolated commands. In multiple runs, the model issued multi-step navigation strategies such as: “move forward for two seconds, then turn right to avoid the desk”, demonstrating a level of situational awareness uncommon in traditional rule-based control systems.

4.2. Advantages of Multimodal Reasoning

The results highlight that multimodal perception—combining visual input and textual context—greatly enhances navigation robustness. The model was not limited to reactive obstacle avoidance; instead, it displayed exploratory behavior, planning short sequences of actions and adapting to dynamic changes in the environment. This ability aligns with the broader objective of enabling autonomous exploration rather than simple ad-hoc command execution.

The reasoning outputs (r field in JSON) provided transparent explanations of each decision, improving interpretability and offering a valuable diagnostic tool. This property is essential for future development of explainable and human-interactive robotic systems.

4.3. Safety and Reliability

The integrated distance sensor safeguard proved effective throughout all trials. Even when the model generated a potentially unsafe motion command, the on-board safety layer immediately stopped the robot upon detecting an obstacle closer than 25 cm. This mechanism ensured physical safety without interrupting the cognitive control loop.

Notably, the combination of local sensor-based protection and server-side cognitive reasoning established a hierarchical control scheme that balances intelligence and determinism. The LLM handled high-level perception and reasoning, while the edge controller enforced deterministic low-level safety constraints.

4.4. Implications and Future Directions

These findings demonstrate that hybrid systems integrating LLM-based cognition with lightweight embedded execution can serve as a foundation for next-generation autonomous and swarm robotics. The proposed architecture supports distributed exploration, where multiple edge robots could share visual context and collaboratively plan actions under the guidance of a centralized or shared language model.

Ongoing research focuses on extending this concept by deploying a compact LLM module directly on the Raspberry Pi, enabling more advanced two-way communication with the main inference server. The embedded model will not only receive and execute commands but will also participate in a lightweight “dialogue” with the server-level LLM during route selection and decision negotiation. This conversational layer aims to introduce partial autonomy at the edge while maintaining global coordination and consistency across multiple agents.

Preliminary tests indicate that such an approach—where several mobile robots collectively discuss and agree upon exploration paths—reduces the total number of communication iterations and increases efficiency in solving more complex navigation tasks. This architecture represents an important step toward scalable, cooperative swarm systems in which each robot contributes local intelligence while the server orchestrates high-level planning and shared understanding.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that Large Language Models (LLMs), and in particular multimodal variants such as LLaVA:7B, can effectively serve as cognitive controllers for autonomous mobile robots. The results confirmed that the proposed client–server architecture, in which the LLM is hosted on a high-performance server and the Raspberry Pi 4 acts as a local sensing and actuation unit, enables real-time reasoning and safe navigation in dynamic environments. The separation of perception and cognition between edge and server layers proved to be a key design factor, combining fast data collection with complex language-driven decision-making. The hybrid system allowed the robot not only to execute commands but also to plan multi-step actions, explore unknown spaces, and provide interpretable textual reasoning for each decision. The inclusion of local safety mechanisms—such as distance sensors and command validation—ensured reliable and collision-free operation even in environments with human participants.

The outcomes highlight the potential of integrating LLM-based reasoning with lightweight robotic platforms as a foundation for future embodied intelligence and swarm systems. Current research is expanding this concept by embedding a smaller local LLM on the Raspberry Pi to enable interactive “dialogue” with the main model during route negotiation. Preliminary tests indicate that such distributed reasoning and cooperative decision-making significantly reduce communication overhead and enhance the scalability of multi-robot exploration.

In conclusion, the successful application of multimodal LLMs for real-time robot control marks an important step toward more autonomous, explainable, and cognitively capable robotic systems. The presented architecture provides a flexible framework for future developments in swarm intelligence, human–robot collaboration, and AI-driven spatial reasoning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D. Ewald; methodology, D. Ewald; software, F. Rogowski, M. Suśniak, P. Bartkowiak and P. Blumensztajn; validation, D. Ewald, F. Rogowski and M. Suśniak; formal analysis, D. Ewald; investigation, F. Rogowski, M. Suśniak, P. Bartkowiak and P. Blumensztajn; resources, D. Ewald; data curation, F. Rogowski and M. Suśniak; writing—original draft preparation, D. Ewald and F. Rogowski; writing—review and editing, D. Ewald; visualization, M. Suśniak and P. Blumensztajn; supervision, D. Ewald; project administration, D. Ewald; funding acquisition, D. Ewald. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Naveed, Humza, et al A comprehensive overview of large language models. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 16.5 (2025): 1-72.

- Han, S.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Duan, J. A Review of Large Language Models: Fundamental Architectures, Key Technological Evolutions, Interdisciplinary Technologies Integration, Optimization and Compression Techniques, Applications, and Challenges. Electronics 2024, 13, 5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Dhruv, Błażej Osiński, and Sergey Levine. "Lm-nav: Robotic navigation with large pre-trained models of language, vision, and action." Conference on robot learning. PMLR, 2023.

- Ping, Yuqi, et al. "Multimodal Large Language Models-Enabled UAV Swarm: Towards Efficient and Intelligent Autonomous Aerial Systems." arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.12710 (2025).

- llava-hf/llava-1.5-7b-hf Model Card. Hugging Face. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.co/llava-hf/llava-1.5-7b-hf.

- LLaVA: Large Language and Vision Assistant. Ollama Library. [Online]. Available: https://ollama.com/library/llava:7b.

- llava-hf/llava-1.5-7b-hf Model Card. Hugging Face. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.co/llava-hf/llava-1.5-7b-hf. (Model info. LLaVA-1.5 7B).

- Toubron, Hugo, et al. Llama 3: The next generation of Llama foundation models. Meta AI, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ai.meta.com/blog/llama-3/.

- Meta-Llama-3-8B-Instruct Model Card. Hugging Face. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/Meta-Llama-3-8B-Instruct.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of evaluated models.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of evaluated models.

| Model |

Latency [ms] |

Valid JSON [%] |

Coherence [%] |

Safety Events [%] |

Smoothness [%] |

| LLaVA:7B (custom) |

185 ± 12 |

96.2 |

94.5 |

0.0 |

91.8 |

| LLaVA (standard) |

240 ± 18 |

88.7 |

82.1 |

4.5 |

83.4 |

| Llama3 (text-only) |

155 ± 9 |

100.0 |

61.3 |

21.5 |

67.8 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).