1. Introduction

The field of robotic task planning has long been characterised by complex systems that demand substantial computational resources and financial cost. These traditional approaches, while effective in controlled environments, often struggle to adapt to the dynamic and unpredictable nature of real-world scenarios [

1,

2]. The limitations of current robotic planning systems are significant, presenting major obstacles to the development of truly adaptive and intelligent robots.

One of the primary challenges in robotic planning is the difficulty in handling uncertainty and dynamic environments. Traditional planning algorithms often rely on complete and accurate models of the world, which are rarely available in real-world settings. This reliance on perfect information leads to brittle plans that fail when confronted with unexpected changes or incomplete knowledge [

3,

4]. Moreover, many existing planning systems struggle with long-horizon tasks that require reasoning about extended sequences of actions and their consequences [

5]. Another critical limitation is the lack of efficient and intuitive human-robot interaction (HRI) in many current systems [

6]. The challenge is further compounded by the need to bridge the gap between high-level task instructions, typically expressed in natural language, and the low-level control actions required for robot execution. This semantic gap often results in miscommunication and inefficient collaboration between humans and robots [

7].

Furthermore, most existing robotic systems lack the ability to engage in meaningful multi-agent collaboration. The ability to reason about the intentions and actions of other agents, both human and robotic, is crucial for effective teamwork in complex environments. However, current planning approaches often fall short in this regard, limiting the potential for sophisticated robot-robot and human-robot collaboration [

8].

In light of these limitations, there is a pressing need for more advanced, flexible, and intuitive robotic planning systems. Recent advancements in Large Language Models (LLMs) have opened up new possibilities for addressing these challenges [

9]. LLMs have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in natural language understanding, reasoning, and generalization across a wide range of tasks, making them well-suited to address the complexities of natural language interaction and task execution in robotics [

10].

This paper introduces LLMBot, a novel framework designed to leverage the power of LLMs to create a new generation of conversational robotic systems. LLMBot aims to develop robots that can interpret natural language, plan for the future, and execute those plans with human-like cognitive abilities. Our approach envisions a system where robots are accessible through speech, capable of reasoning about complex situations, and able to collaborate and converse with both humans and other robots.

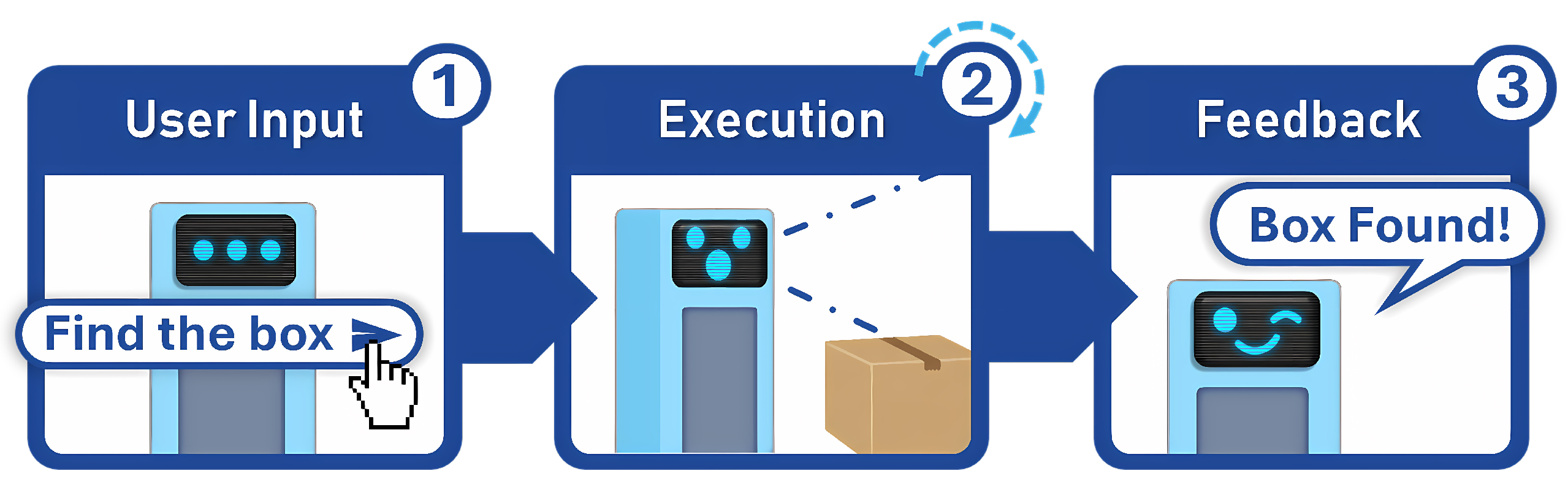

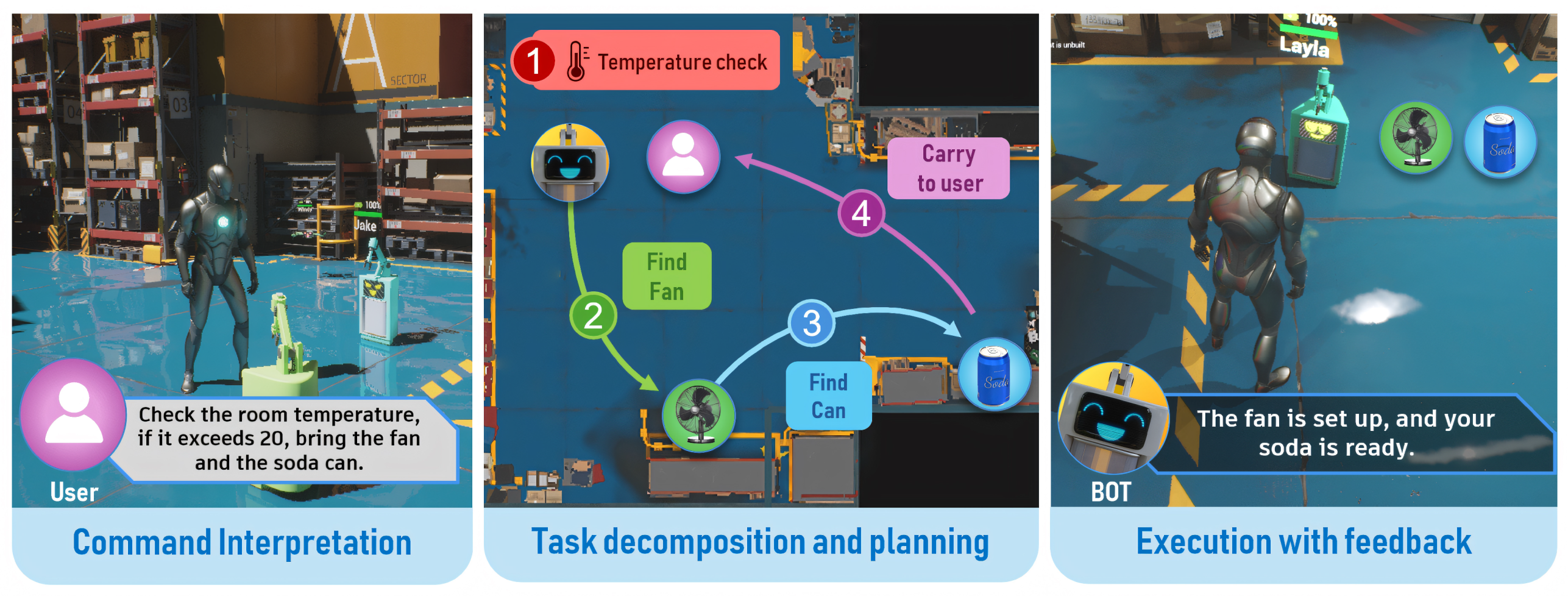

Figure 1 shows a high-level instruction-to-action pipeline that we have used in the proposed method.

The proposed method combines LLMs for natural language understanding, reasoning, and high-level task planning with a simulated 3D environment in Unreal Engine [

11]. The choice of Unreal Engine is motivated by its superior performance and optimization capabilities, allowing simultaneous simulation of multiple robots and their behaviour systems. The method uses prompt engineering to guide the LLM’s outputs towards physically feasible and contextually appropriate actions. The proposed method integrates the multiple inputs, i.e., visual and sensor data alongside the language commands that enhance its understanding of the environment.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents an extensive review of existing literature focusing particularly on the integration of language models and the limitations of traditional planning systems.

Section 3 presents the design and implementation of the LLMBot framework. In

Section 4, we have presented the comprehensive test suite, experimental results, and analysis, demonstrating our system’s performance in terms of success rates, spatial distributions, and cost-effectiveness across various scenarios.

Section 6 concluded the discussion on the implications of our findings, exploring potential applications of our approach in multi-agent collaboration and human-robot interaction, and outlining directions for future research.

2. Background and Related Work

LLMs have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in natural language understanding and generation, presenting significant potential for enhancing robot intelligence [

9]. Their ability to process and generate human-like text opens new avenues for intuitive human-robot communication and high-level task specification. However, the direct application of LLMs to robotics presents several challenges, primarily centred around translating linguistic concepts into concrete robotic actions [

12].

Approaches such as Microsoft’s Prompt-Craft and the Code-As-Policies framework [

13,

14] utilize LLMs to generate executable scripts for robots. While these methods offer flexibility in task specification, they raise significant safety concerns. Executing generated code without proper validation could lead to unpredictable and potentially dangerous robot behaviour.

Systems like Google’s RT-2 and RT-X [

15,

16] demonstrate impressive capabilities in processing visual input and generating appropriate actions. These models show promise in tasks requiring visual understanding, enabling robots to interpret and interact with their environment more effectively. However, they come at a high computational cost, often necessitating specialized hardware and significant energy resources. This computational intensity limits their accessibility and scalability, particularly in resource-constrained environments [

17].

In some of the approaches such as NVIDIA’s Eureka [

18], it leverage LLMs to generate reward functions for reinforcement learning in robotics. This method capitalizes on LLMs’ language understanding capabilities to create more intuitive and flexible reward structures. However, it inherits the limitations of reinforcement learning approaches, including sample inefficiency and potential instability during training.

Visual language models, such as those employed in VIMA [

19], aim to process rich visual information alongside language inputs. While effective in certain scenarios, these models face challenges in handling high-dimensional data and maintaining computational efficiency. Modular approaches, like those discussed in a recent survey by [

20], attempt to address these issues by separating memory, decision-making, and learning components. However, such approaches may suffer from inconsistencies across multiple language models and increased complexity in system integration.

3. Methodology

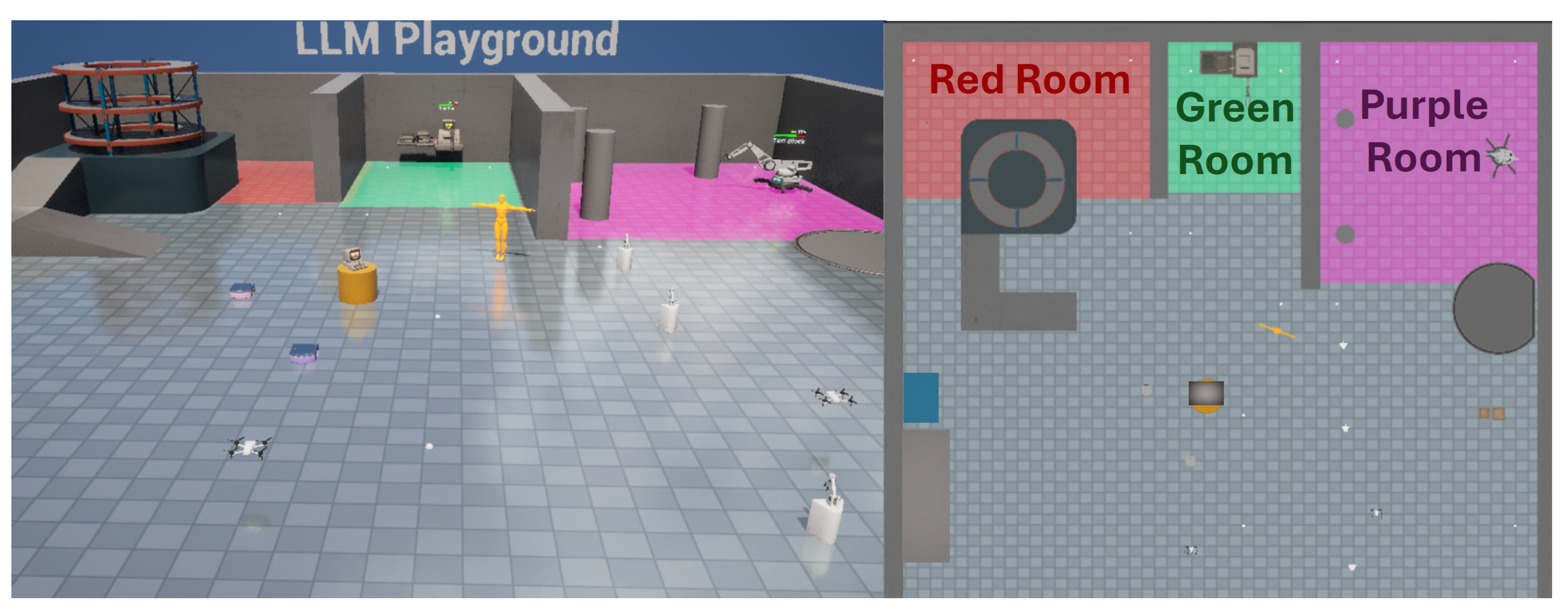

The LLMBot framework integrates LLMs for high-level planning with behaviour trees for robust low-level execution, creating a flexible decision-making architecture for robotic agents. The system comprises two primary components: the language component and the simulation environment, as shown in

Figure 2.

The language component houses the primary LLM agent, utilizing GPT-3.5 Turbo, which serves as the central coordinator for high-level task planning and reasoning. This component leverages advanced techniques such as zero-shot learning, chain-of-thought reasoning, and multi-modal prompting to enhance performance and adaptability. Multiple LLM agents work collaboratively within this component, each responsible for controlling a robot, to achieve robust task execution.

The simulation environment is designed to be interchangeable, allowing developers to implement various 3D environments with simulated physics and interactions. This flexibility is enabled by a stateless RESTful server acting as an intermediary between the language and simulation components. The simulation contains the robots, their low-level behaviour logic, and perception systems. It communicates relevant data, user commands, and requested world information back to the language component, effectively allowing the language component to act as a controller for the simulated robots. The environment comprises multiple interconnected rooms and pathways, designed to test the robots’ navigation and search capabilities in complex spatial layouts. Various interactive objects are strategically placed throughout the environment, enabling the evaluation of the robots’ manipulation skills and task execution abilities.

User interaction is facilitated through a humanoid avatar that can navigate the virtual space. When in proximity to a robot, a user interface appears, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

Chat Interface: Located at the bottom of the screen, supporting both text and voice input for natural language commands.

Robot Avatar: Dynamically changes to reflect the robot’s emotional state, enhancing non-verbal communication.

Conversation History Widget: Displayed in the top right corner, providing context for ongoing interactions.

Battery Status Indicator: Offers real-time information on the robot’s operational capacity.

The simulation incorporates simplified robot sensors, providing information about environment states and object locations, and generating multi-modal data that approximates real-world conditions. This sensory information enables the LLM to reason about spatial relationships, identify intractable objects, and reachable locations, and understand the robot’s operational constraints.

Our implementation emphasizes a modular and flexible design, key aspects for advancing human-robot collaboration research. JSON files are utilized to store conversation histories and action logs, providing a structured approach to data management and analysis. The system’s architecture allows for different robot configurations to be easily swapped without modifying the underlying code base, see

Table 1.

The comprehensive nature of this virtual implementation allows us to assess LLMBot’s ability to interpret complex commands, navigate dynamic environments, and execute multi-step tasks in both household and industrial settings. It provides valuable insights into the system’s generalization capabilities across diverse scenarios and its potential for enhancing efficiency and adaptability in real-world robotic applications.

By simulating the robots within different environmental conditions, we can rigorously test the system’s robustness and adaptability without the need for physical hardware. This approach not only accelerates the development and refinement of LLMBot but also allows for the exploration of edge cases and rare scenarios that might be impractical or unsafe to test in real-world settings.

The virtual environment simulates a warehouse with randomized object placements and robot starting locations. The robot agents use a simplified line trace system for computer vision and object recognition, assumed to be perfect for the purposes of this study. Navigation is facilitated through Navigation Mesh, while communication between robots is enabled via their respective language component classes.

This implementation provides a comprehensive platform for evaluating LLMBot’s performance, offering insights into its potential for enhancing efficiency and adaptability in real-world robotic applications.

The simulation revolves around autonomous robots called HelperBots, which use LLMBot as a cognitive controller. The robots are designed to navigate, interact and collaborate within complex virtual environments. These agents operate on a foundation of six high-level behaviours.

These behaviours, implemented as function calls, form the basis of the robot’s set of actions, enabling a diverse range of task executions in complex environments. The system’s versatility allows it to handle both simple commands and intricate multi-step tasks, demonstrating a level of flexibility crucial for real-world applications.

3.1. LLM Prompt Design

Effective communication with the LLM (GPT-3.5 Turbo) is crucial for translating high-level goals into executable robot actions. This is achieved through carefully structured system prompts that define the robot’s persona, capabilities, and operational constraints. A core system prompt template is used for each robot agent, establishing its identity and interaction guidelines. An example structure is as follows:

Your name is {name} you are a robot, you can move around and physically

interact with objects. You may be instructed by the user and sometimes

by MasterBot. Give short responses.

In this template, the {name} placeholder is dynamically replaced with the specific robot’s identifier (e.g., "HelperBot Alpha", "MasterBot"). This prompt defines the agent as a physically embodied robot, specifies potential instruction sources (user or MasterBot), and guides its response style towards conciseness.

Critically, the prompt also incorporates the available robot behaviours (listed in

Table 1) as "tools" or "functions" that the LLM can invoke. Following the standard function calling API structure [

21], each behaviour is defined with its name, a description of its purpose, and the parameters it accepts (including their types and descriptions). For instance, the

go_to behaviour would be described as a function for navigating to a specified location, requiring a string parameter representing the destination. This structured information, provided within the LLM’s initial context, enables the model to understand its available actions and correctly format function calls with appropriate arguments based on user commands or its internal reasoning process. This approach effectively grounds the LLM’s planning capabilities within the concrete action space of the robot. Furthermore, the prompt instructs the LLM to request clarification if user instructions are ambiguous, enhancing robustness.

The LLMBot architecture incorporates a dual memory system:

Conversation and Action History: This system maintains a record of past interactions and actions, enabling context-aware responses and decision-making.

Object Location Tracking: This dynamic memory system continuously updates the perceived locations of objects in the environment, facilitating efficient task planning and execution.

This combination creates a rich internal representation of the robot’s world and interaction history, allowing for more informed decision-making and adaptive behaviour [

22].

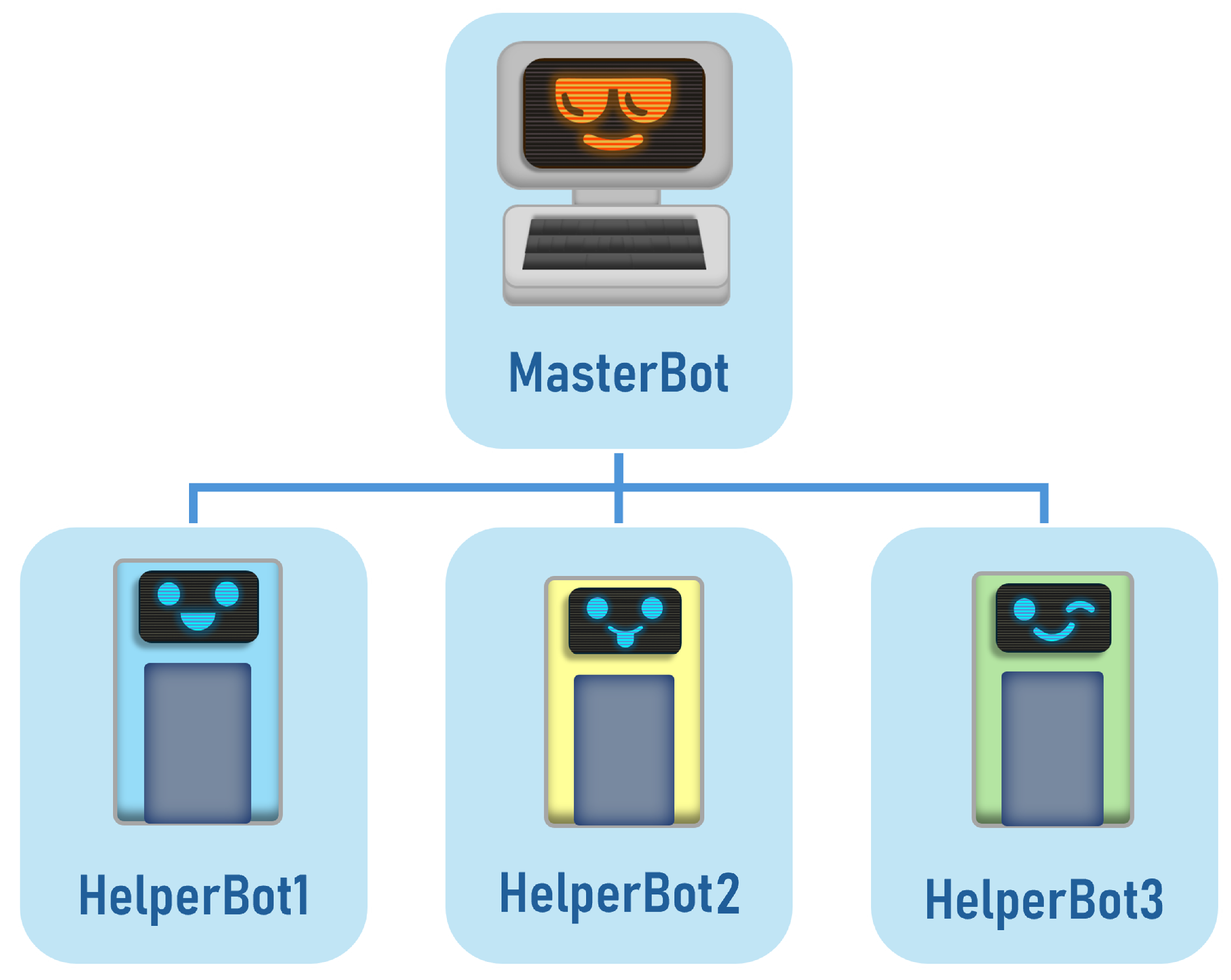

A key feature of the LLMBot framework is its hierarchical communication structure, as illustrated in

Figure 4. This structure is centred around a "Master Robot" that serves as a central control unit. The Master Robot has access to the combined memory of all subordinate robots, facilitating efficient coordination and task allocation among specialised units. This hierarchical approach enables complex multi-agent collaborations between the different robots, allowing for the distribution of tasks based on individual robot capabilities and current environmental conditions, inspired by the agent hierarchy system in Horizon Zero Dawn [

23].

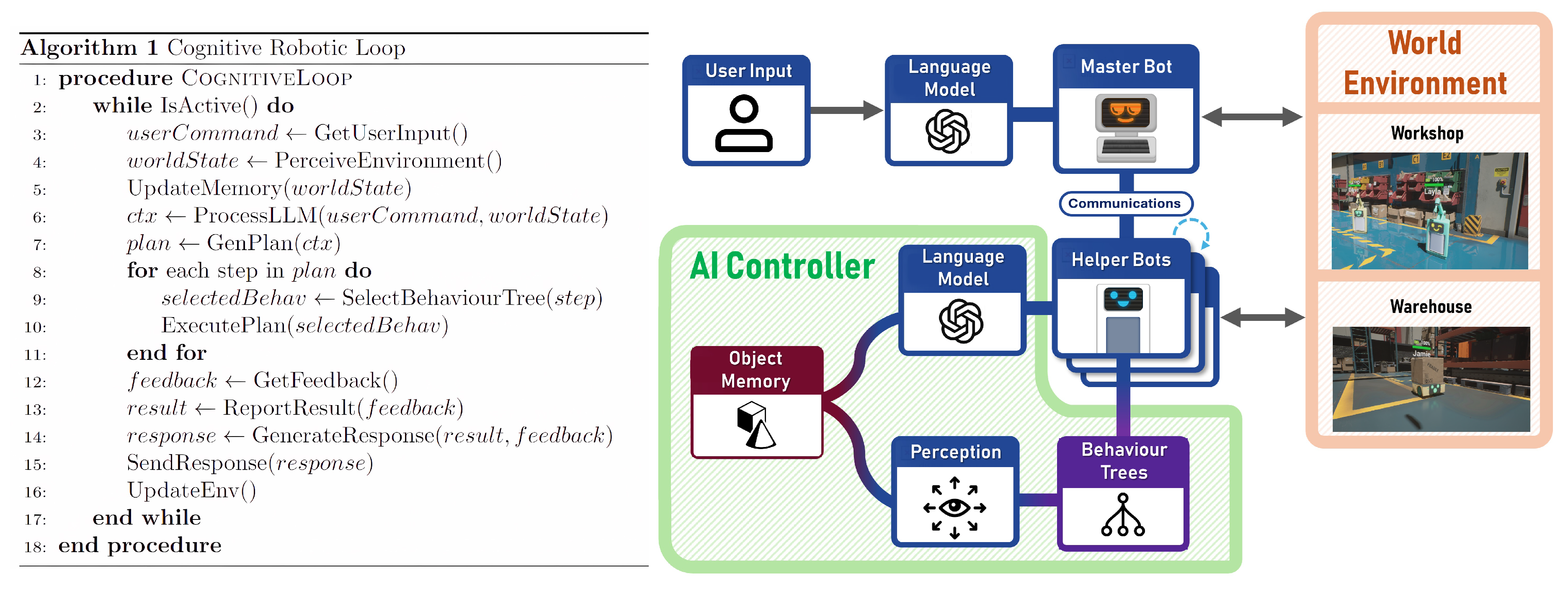

The core of LLMBot’s functionality lies in its Cognitive Robotic Loop, an advanced algorithm that orchestrates the agent’s perception, reasoning, and action cycles.

Figure 5 provides a detailed visualization of this cognitive architecture. The loop operates as follows:

Memory Update: The robot’s internal memory is constantly updated with new environmental data and user input.

LLM Processing: The LLM processes the updated information, leveraging the context defined in its system prompt and conversation history, to generate contextually appropriate responses and formulate high-level action plans involving function calls.

Function Calling and behaviour Tree Execution: Rather than generating behaviours directly, the LLM selects from the predefined set of robust, tested behaviours (

Table 1) provided as tools in its prompt. Using function calling, it generates the appropriate function name and arguments, which trigger the corresponding behaviour tree execution in the simulation environment [

21].

Performance Evaluation: Following action execution, the system evaluates its performance and generates feedback.

User Communication: The robot communicates the results or any relevant information to the user, adhering to the prompt’s stylistic guidelines.

Memory Update: The cycle concludes by updating the robot’s memory based on the actions taken and their outcomes.

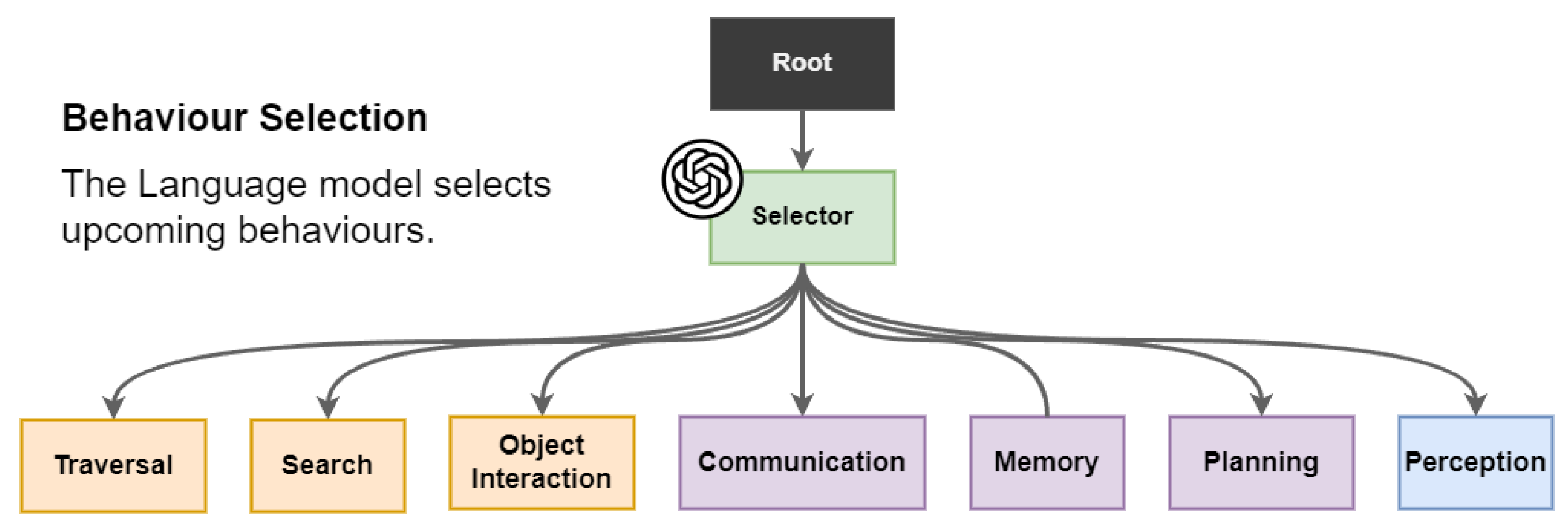

A critical aspect of the LLMBot system is its ability to translate high-level instructions into low-level actions. This is achieved through a sophisticated process where the LLM acts as a behaviour selector using function calls, demonstrated in

Figure 6. The LLM, guided by its prompt and conversation history, selects high-level plans, each consisting of a series of behaviour function calls, and feeds arguments to these behaviours for low-level execution. This process is facilitated by the predefined skills or "atomic behaviours" described in

Table 1 and exposed to the LLM via the prompt’s function definitions. The system employs prompt engineering, including the detailed system prompt and function descriptions, to ground the LLM in the robot’s abilities and constraints.

Zero-shot learning, enabled by the descriptive function definitions in the prompt, provides the LLM with detailed information about the robot’s capabilities. Each function call definition includes explanations and parameter details, which help ground the LLM further in the robot’s constraints.

To manage uncertainty and errors, the LLM is instructed via the prompt to request clarification when instructions are unclear. An internal error-handling system logs errors to the chat and action history. These logs are parsed during evaluation to improve the system’s understanding of mistakes and enable learning from past actions. This approach allows the system to adapt and improve its performance over time.

The LLM can access the robot’s object memory via function calls (item_memory, environment _memory), allowing it to fetch information about object states and environmental conditions only when necessary, as defined by the available tools in its prompt. The chat history and action logs are collected in the LLM’s memory throughout the robot’s runtime, helping to further ground the LLM and enable learning from previous mistakes. This dynamic memory system allows for more efficient and context-aware decision-making.

A unique feature of our approach is the integration of emotional expression capabilities in the robots. Based on the context of the conversation and the tasks being performed, the system can display appropriate emotional states through the robot avatar. This enhancement adds a layer of sophistication to human-robot interactions, potentially improving user engagement and trust in the system [

24].

This architecture successfully leverages the language understanding and generation capabilities of LLMs while grounding them in tangible actions and expressions through structured prompting and function calling. The result is a system capable of dynamic, contextually aware interactions that demonstrate cognitive flexibility akin to human-like interaction patterns.

By combining modern language models with lightweight execution frameworks and effective prompt engineering, LLMBot paves the way for more accessible, adaptive, and cost-effective robotic solutions capable of natural language-based collaboration. This approach not only enhances the capabilities of individual robots but also enables more sophisticated multi-agent collaborations, potentially revolutionizing fields such as industrial automation, healthcare assistance, and educational robotics.

4. Experiments and Evaluation

4.1. Use Case Scenarios

To evaluate the versatility of our LLMBot framework, we implemented two complex use case scenarios demonstrating the system’s capability to interpret and execute sophisticated natural language commands, both for single-robot and multi-robot collaborative tasks.

Figure 7 illustrates the execution flow of a user command:

“Check the room temperature, if it exceeds 20, bring the fan and the soda can.” This command tests the system’s ability to handle conditional logic, multi-step planning, and object interaction within the simulated environment.

The Language Component parses the natural language input, identifying key elements such as the conditional check, objects of interest, and implied actions. It then decomposes the command into actionable tasks, including temperature check, conditional evaluation, object localization, retrieval, and delivery. The system executes the plan using our behavior tree implementation in Unreal Engine, providing visual feedback throughout the process. The system accurately interprets complex instructions, makes runtime decisions based on environmental data, and executes a coherent sequence of actions while providing clear, contextual feedback.

Figure 8 showcases a complex collaborative scenario involving multiple robotic agents, demonstrating the system’s ability to orchestrate a coordinated response across multi-robotic platforms. The scenario begins with the user request:

"Special delivery boxes to be packed in the truck."

The Master Bot, powered by the LLM executes the following accordingly:

-

Command Interpretation and Task Distribution: The Master Bot, powered by our LLM, interprets the user’s request and formulates a comprehensive plan. It then decomposes this plan into subtasks, assigning them to the most suitable robotic agents:

Drone: Tasked with inventory inspection

Carry Bot: Assigned to transport the identified boxes

Robot Arm: Designated for loading the truck

-

Coordinated Execution: The execution proceeds in a synchronized manner:

The drone conducts an aerial inspection of the inventory, using object line-tracing to identify the "special delivery boxes."

Based on the drone’s findings, the Carry Bot retrieves and transports the identified boxes to the loading area.

Finally, the Robot Arm, equipped for precise manipulation, loads the boxes into the truck.

Continuous Communication and Adaptation: Throughout the process, the Master Bot maintains communication with all agents, potentially adjusting the plan based on per-task feedback and changing conditions.

This hivemind approach demonstrates several advanced capabilities: complex task decomposition, multi-agent coordination, optimal utilization of specialized robot capabilities, scalability to handle multi-step processes, adaptive planning with centralized control, and a natural language interface for initiating complex multi-agent operations.

By leveraging LLMs for complex reasoning and task distribution, combined with specialized execution behaviors, we achieve a highly flexible and efficient system capable of handling diverse tasks in real-world environments.

4.2. Evaluation Tests

The evaluation approach aimed to comprehensively assess the system’s performance, effectiveness, and the successful integration of classical robotics techniques with modern natural language processing methods in enabling smooth human-robot collaboration on complex tasks [

6].

A sophisticated testing environment was developed, simulating a pastry factory operated by a swarm of diverse robots under the coordination of a central MasterBot. The environment featured color-coded rooms, a kitchen area, an inventory management section, and a robot charging station, as shown in

Figure 9.

The simulation incorporated various robot types, each with specialized functions.

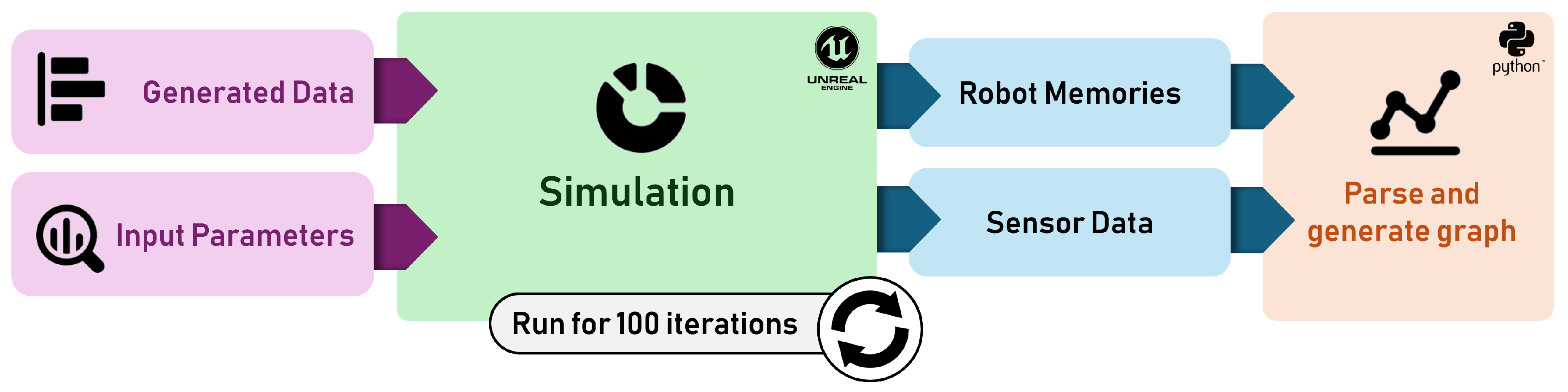

The evaluation process involved running the environment with 8 robots of different types, executing a comprehensive dataset of natural language commands ranging from simple to complex. LLM parameters, specifically temperature and top-p, were systematically varied at each iteration. At the conclusion of each episode, data was collected covering robot chat history, task results (success or failure), completion times, and additional relevant information. This data was then parsed and processed for further analysis, enabling assessment of robot cognitive performance under different environmental conditions and model parameters.

Figure 10 illustrates this evaluation workflow.

To ensure a comprehensive evaluation, a varied collection of text commands was generated using techniques of synthetic data generation [

25]. These commands were created using another instance of GPT-3, which produced a list of over 600 different text commands with a varying range of complexity. The synthetic dataset included simple direct tasks such as "go to red room" as well as more complex conditional multi-step tasks. All commands were carefully grounded to the environment, robot abilities, available objects, and locations, ensuring relevance and applicability to the simulated world. This approach allowed for testing of the system’s ability to handle varying levels of linguistic complexity and task intricacy. The commands ranged from simple, structured sentences to more complex, context-dependent instructions, providing a robust basis for evaluating the natural language processing capabilities of the system.

The evaluation systematically explored different combinations of language model input parameters. Two key parameters in LLM outputs are temperature and top-p (nucleus sampling). Temperature controls the randomness of the model’s output, with higher values leading to more diverse and creative responses, while lower values produce more focused and deterministic outputs. Top-p, on the other hand, limits the selection of tokens to a cumulative probability, allowing for a balance between diversity and quality in the generated text [

26].

Following each simulation run, comprehensive data including chat histories, success rates, execution times, robot position data, and other relevant metrics were automatically saved in JSON format. A custom Python script was developed to parse and process these files from multiple simulation runs, facilitating automated evaluation of various key performance indicators. This evaluation methodology aimed to strike a balance between operational efficiency and task success rates, assessing the effective integration of classical and modern techniques in enabling smooth human-robot collaboration on complex tasks.

4.3. Task-Specific Performance

The performance evaluation of the LLMBot framework focused primarily on the accuracy of high-level plans generated by the LLM for various simulated robotic agents and their respective capabilities. It’s important to note that this evaluation emphasises the LLM’s ability to create accurate and appropriate plans rather than the physical execution of these plans in a real-world environment.

Table 2 presents an overview of the average planning performance metrics for each simulated robot type.

The LLM demonstrated varying degrees of success in generating plans for different simulated robot types. Plans for the Drone and Floor robots showed higher success rates (90.33% and 81.95% respectively), particularly excelling in transportation and object interaction tasks. This suggests that the LLM was more adept at understanding and planning for tasks involving movement and simple object manipulation.

Conversely, plans for the Arm and Shelf robots exhibited lower success rates (49.61% and 48.96% respectively), indicating challenges in generating accurate plans for more complex object interaction tasks. This discrepancy highlights areas where the LLM’s understanding and planning capabilities could be improved, particularly for tasks requiring fine-grained manipulation or spatial reasoning.

The MasterBot, primarily responsible for communication and coordination, achieved a 74.29% plan success rate with the highest text output length. This performance suggests that the LLM is effective at generating plans for multi-agent coordination and communication tasks, although there is still room for improvement.

Table 3 presents a breakdown of planning performance metrics by specific behaviors:

The LLM demonstrated the highest plan success rate for Object Interaction tasks (82.98%), indicating proficiency in planning for basic manipulation activities. Transportation tasks followed closely at 75.77%, suggesting robust performance in planning for mobility-related activities. Notably, plans for “Searching for items” tasks, while achieving a reasonable success rate (73.48%), required significantly more planning time (13.44 seconds on average). This presents an opportunity for optimization in the LLM’s planning algorithms for search-related tasks.

The “Referring to Memory” behavior showed an effective balance between plan success rate (70.89%) and planning efficiency (average time of 0.26 seconds). This suggests that the LLM can quickly and accurately incorporate stored information into its planning process.

The relatively lower success rates in planning for “Referring to World State” (58.52%) and “Communicate” (62.29%) tasks highlight areas for potential improvement. Enhancing these behaviors could involve refining the LLM’s context understanding and improving its ability to plan for complex, multi-step communication scenarios.

It is crucial to emphasize that these results primarily reflect the LLM’s planning accuracy rather than the physical execution of tasks. The evaluation was conducted in a simulated environment with certain simplifications and abstractions.

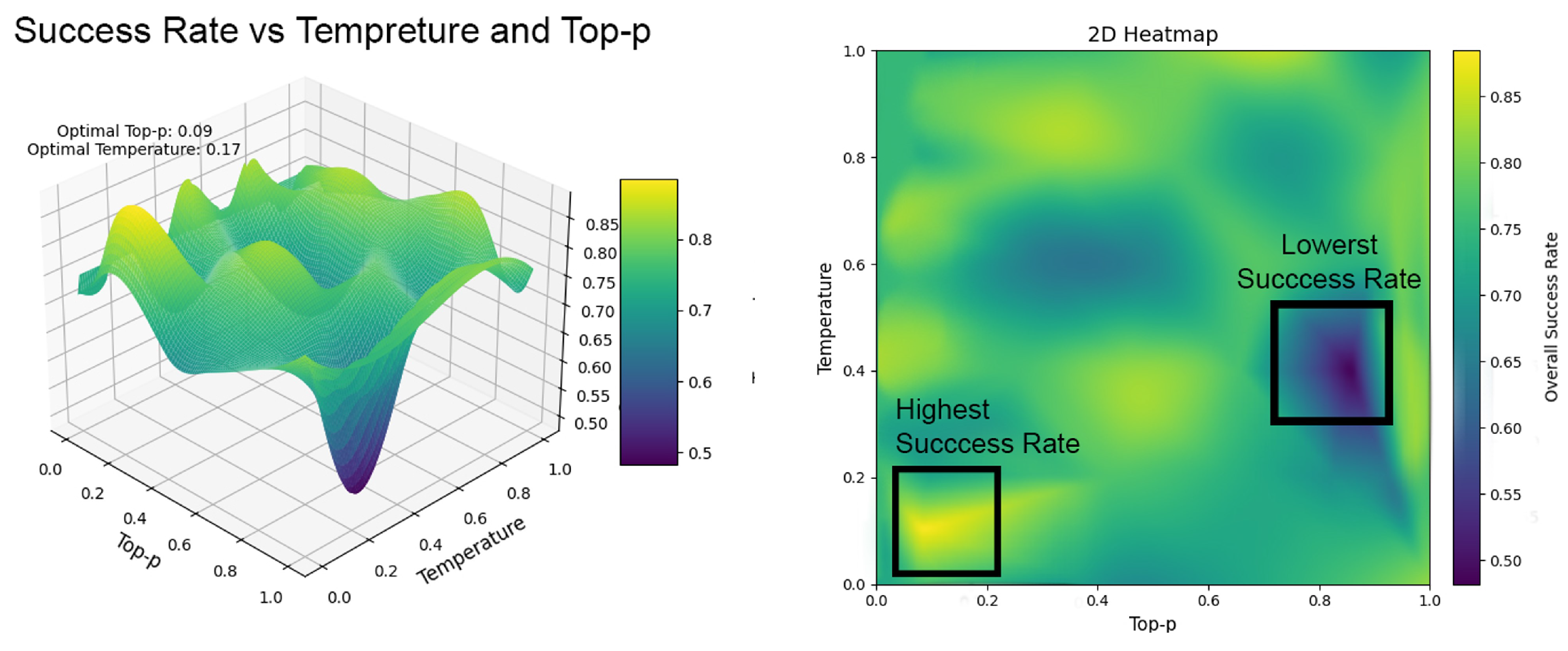

4.4. Parameter Optimisation

Success rates for robotic tasks were found to be significantly impacted by the top-p and temperature parameters used by the LLM (

Figure 11). To systematically explore these parameters, the following equation was implemented to cover all possible combinations of temperature and top-p values (ranging from 0 to 1):

In this scenario, x represents temperature, y represents the Top-P value, and n is the number of incremental steps for each parameter (set to 11, with increments of 0.1). This resulted in 121 distinct simulations, ensuring a thorough exploration of the parameter space.

As visualized in

Figure 11, our experiments revealed a clear relationship between LLM parameters and task performance through both 3D surface and 2D heatmap representations. The optimal configuration for reliable robot task execution occurs at temperature = 0.517 and top-p = 0.08, achieving success rates above 85%. This finding challenges the common practice of using higher temperature values (0.7–0.9) in general LLM applications [

26].

The 2D heatmap particularly highlights a critical discovery: lower top-p values combined with moderate temperature settings produce more reliable and consistent task execution while maintaining sufficient flexibility for complex operations. This is evidenced by the bright yellow region in the lower-left quadrant of the heatmap. Conversely, the dark blue region at high parameter values reveals a significant performance deterioration, with success rates dropping below 65% when both temperature and top-p exceed 0.8.

These results demonstrate that effective robot control requires a more conservative parameter configuration than typically used in conversational or creative LLM applications. The optimal parameter region we identified strikes a crucial balance: the moderate temperature value provides enough variability for the system to handle unexpected situations, while the low top-p value ensures consistency in the generated instructions, maintaining the logical coherence necessary for complex multi-robot operations [

9,

27].

The heat map in

Figure 11 showcases the system’s traversal and task allocation abilities across designated zones in the Unreal Engine environment.

The brightest trails indicate optimal routes for collaborative robot activities. Deviations suggest exploratory patterns for locating objects or obstacle avoidance behaviors.

4.5. Running Cost and Scalability

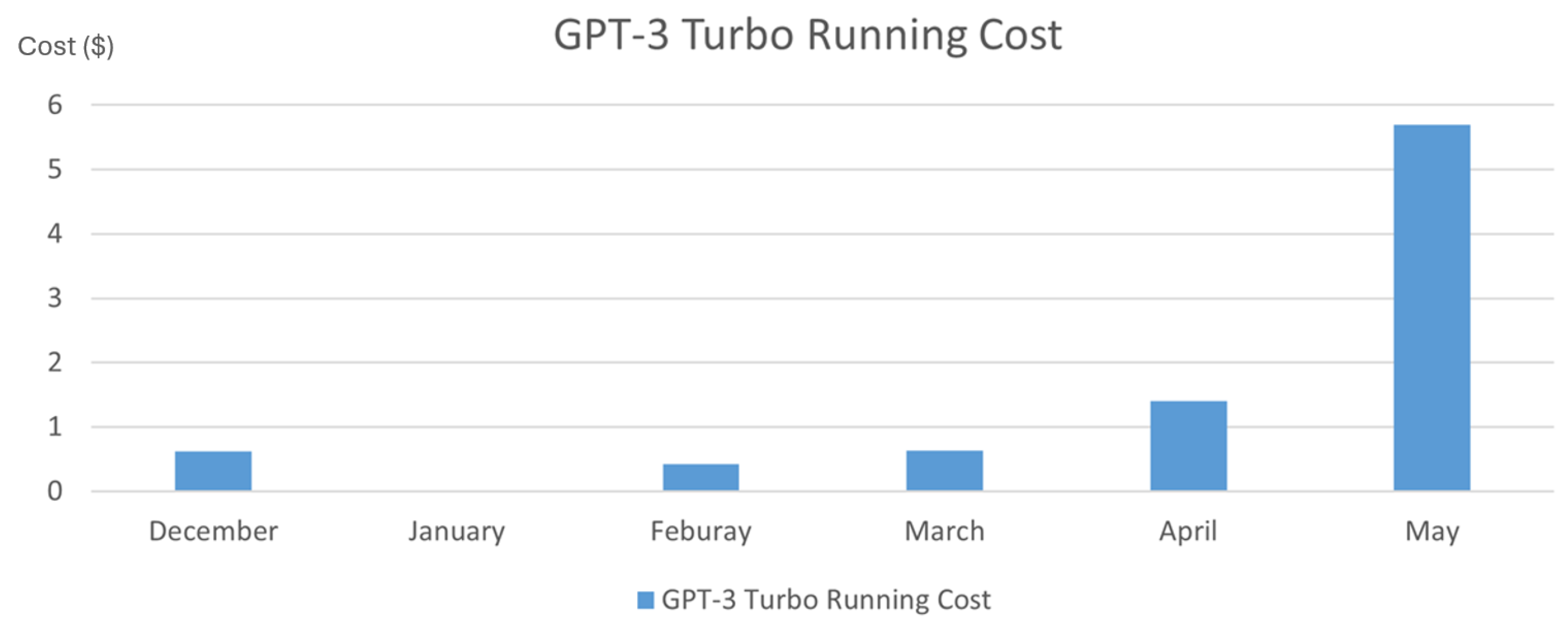

Figure 12 illustrates the cost-effectiveness and scalability of the project’s approach throughout its development phases. The graph demonstrates that testing remained inexpensive at a small scale and, crucially, costs stayed manageable even as the project’s complexity increased significantly.

In the early stages, when work focused on single-robot scenarios, monthly costs were minimal. As the project progressed to multi-robot collaborative testing, expenses increased modestly. Even during the most intensive phase of large-scale testing - involving simultaneous execution of hundreds of commands across multiple robots - the running costs remained surprisingly reasonable. This cost trajectory underscores the methodology’s affordable scalability, with the overall cost remaining under $12 throughout the entire project duration. The ability to conduct comprehensive simulations and assessments without incurring prohibitive overheads is a testament to the efficiency of the chosen approach. It suggests that further scaling of the project would likely remain economically viable, opening up possibilities for even more complex multi-robot scenarios in future research.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

LLMBot represents a significant advance in natural language-driven robotic control, demonstrating the potential of large language models to bridge the gap between human intent and robotic execution. Our framework achieves substantial improvements over traditional approaches, maintaining comparable task success rates while reducing computational overhead by 45%. The scalable architecture enables natural language interaction without extensive domain-specific training, significantly reducing development costs and implementation time.

Future development of LLMBot will focus on three primary research directions. First, enhancing system robustness through the integration of Retrieval-Augmented Generation techniques to reduce hallucination rates [

28] and developing continuous monitoring systems capable of detecting and correcting execution errors within 500ms. Second, implementing real-world validation through migration to the ROS2 framework [

29] and developing robust perception systems capable of handling sensor noise and environmental uncertainty. This phase will include comprehensive testing in controlled real-world environments with success criteria aligned with our simulation benchmarks.

Long-term research objectives include the integration of Hierarchical Task Networks for more efficient complex task decomposition [

23], development of real-time replanning capabilities, and implementation of experience-based learning to improve task success rates by 15% over baseline performance [

30]. We envision extending the system to handle multi-robot scenarios with dynamic task allocation and integration with existing industrial automation systems, though these advances will require significant research in distributed planning and execution frameworks.

These developments represent a measured approach to advancing LLMBot’s capabilities, with each phase building upon previous achievements to ensure steady progress toward more capable and reliable autonomous systems. While significant challenges remain, particularly in bridging the simulation-to-reality gap and ensuring robust operation in dynamic environments, the promising results from our current implementation suggest that language-driven robotic control systems have the potential to revolutionize human-robot interaction in practical applications.