1. Introduction

Large Language Model (LLMs) are increasingly transforming the landscape of robotics by enabling natural, language-driven interfaces for control, perception, and decision-making [

1]. Initially developed for text-based applications, LLMs have shown promising capabilities in generating structured plans, interpreting visual contexts, and performing high-level reasoning [

2,

3]. In [

4], the authors proposed RobotGPT, which can generate robotic manipulation plans by using ChatGPT as a knowledge source and training a robust agent through imitation. In the domain of autonomous driving, Xu et al. [

5] investigate the fusion of visual and language-based inputs to provide interpretable, end-to-end vehicle control while simultaneously generating human-readable rationales.

The inherent capability of LLMs to interpret natural language present unique opportunities for intuitive Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) and autonomous mission planning. LLMs can potentially extract intent from commands expressed in natural language, and translate them into a series of executable robotic actions, reducing the need for manual coding and predefined task-specific programming [

6]. This shift toward language-based control allows drones and Autonomous Mobile Robot (AMRs) to be directed through task descriptions and goals in natural language, instead of intricate control instructions [

7]. Nevertheless, challenges persist in guaranteeing the reliability, interpretability, and efficacy of these Artificial Intelligence (AI)-powered systems in real-world scenarios, across robotic and autonomous applications [

8].

Recent research has pushed towards leveraging LLMs to enhance HRI by making robotic systems more adaptive, expressive, and intuitive. One area of exploration involves employing LLMs for emotion-aware interactions, where models can interpret user affect and modulate robot responses accordingly. For instance, Mishra et al. [

9] demonstrated that LLM-based emotion prediction can improve perceived emotional alignment, social presence, and task performance in social robots. Another fascinating direction is the use of LLMs for interaction regulation through language-based behavioral control. Rather than relying on fixed, state-machine logic, these systems use example-driven, natural language prompts to guide robot behavior, improving transparency and flexibility [

10]. In addition, LLMs have been applied as zero-shot models for human behavior prediction, offering the ability to adapt to novel user behaviors without the need for extensive pretraining or datasets [

6]. Such capabilities are particularly valuable in dynamic and personalized interaction scenarios, where traditional scripted approaches fall short.

The integration of LLMs for navigation and planning has gained significant momentum. In [

11], the authors employed LLMs to drive exploration behavior and reasoning in robots, highlighting the models’ capacity to handle ambiguity and incomplete visual cues. While in [

12], they studied how linguistic phrasing influences task success and revealing typical limitations such as hallucinations and spatial reasoning failures. Collectively, these efforts underscore the promise of LLMs in enabling flexible and generalizable robotic autonomy, while also exposing significant challenges in sensory grounding, planning reliability, and evaluation robustness.

In parallel, the robotics community continues to advance traditional path-planning and obstacle-avoidance methods for AMRs and unmanned systems. Comprehensive surveys have categorized existing algorithms, ranging from graph search and sampling-based planners to AI and optimization-based methods, highlighting their progress and future challenges in ensuring safe, efficient navigation for ground, aerial, and underwater robots [

13]. Recent advances in model predictive control and potential field fusion have also demonstrated strong results in coordinating multiple wheeled mobile robots under uncertain environments [

14], reinforcing the importance of integrating robust perception and planning frameworks. These developments complement the emerging trend of using LLMs as high-level cognitive planners that can interpret multimodal information and reason about navigation goals in dynamic environments.

In this paper, we introduce two major contributions to the field. First, we enrich the multimodal context available to the LLM by incorporating LiDAR data alongside visual information, allowing the model to reason with explicit object distances, improving spatial grounding. Second, we evaluate our approach across multiple LLMs, including two OpenAI models and Gemini, providing a comparative analysis that highlights performance variations under identical conditions. To address the limitations of existing success metrics, we employed an objective evaluation criterion that combines both the robot’s final distance and orientation relative to the target, offering a more precise measure of task completion.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 illustrates some related works.

Section 3 details our approach while

Section 4 describes the results of our experiments.

Section 5 discusses the results, highlighting the limitations. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper, paving the way for future works.

2. Related Work

The integration of LLMs in zero-shot planning for navigation and exploration has garnered significant attention in the robotics community, with recent works proposing various strategies for leveraging the commonsense reasoning and semantic capabilities of these models. Recent studies have underscored that integrating LiDAR and vision sensors significantly enhances environmental perception and localization accuracy, as multi-sensor SLAM approaches consistently outperform single-modality systems in complex indoor and outdoor environments [

15]. Dorbala et al. [

16] introduced LGX, which combines LLM-driven reasoning with visual grounding via a pre-trained vision-language model to navigate toward semantically described objects. Their system executes high-level plans in a zero-shot manner and showcases strong performance in simulated and real-world settings, though it relies solely on visual information and generates complete navigation plans at each step. Similarly, Yu et al. [

17] designed a dual-paradigm LLM-based framework for navigation in unknown environments, demonstrating that the incorporation of semantic frontiers informed by language enhances exploratory efficiency. However, like LGX, their system does not incorporate other perceptual modalities such as depth or LiDAR to refine spatial reasoning and lacks dynamic planning capabilities during execution. In contrast, our approach integrates LiDAR data with visual inputs, enabling the LLM to reason over object distances, and adopts a step-wise planning paradigm to improve adaptivity and reduce error propagation.

Other approaches also explore the fusion of language understanding with visual reasoning for robotic control. Nasiriany et al. [

18] proposed PIVOT, a prompting strategy that iteratively refines robot actions through visual question answering with Vision-Language Model (VLMs), offering a novel interaction paradigm without requiring fine-tuning. Though effective, PIVOT still depends on candidate visual proposals and lacks explicit metric information (e.g., distances or angles), which our LiDAR-based setup directly provides. Shah et al. [

19] and Tan et al. [

20] demonstrated LLM-based navigation and manipulation by chaining pre-trained modules, such as CLIP and GPT, into systems like LM-Nav and RT-2. These models showcase emergent capabilities such as landmark-based reasoning and multi-step instruction following. However, they require significant offline processing or co-fine-tuning and primarily use static success measures for evaluation. In contrast, we introduce a more objective and continuous metric that combines the robot’s final distance and orientation relative to the goal, addressing ambiguities in traditional success rate definitions.

Moreover, Yokoyama et al. [

21] and Huang et al. [

22] advanced semantic navigation and manipulation through structured map representations and affordance reasoning. Vision-Language Frontier Maps (VLFM) [

21] constructs semantic frontier maps to guide navigation toward unseen objects, emphasizing spatial reasoning derived from depth maps and vision-language grounding. Although VLFM achieves strong real-world performance, its frontier selection mechanism is largely map-centric and lacks interaction with real-time language feedback. Huang et al. [

22] focused on manipulation via LLM-driven value map synthesis and trajectory generation, with strong affordance generalization but constrained to contact-rich manipulation tasks. Our work complements these efforts by targeting mobile robot navigation in complex environments with an emphasis on incremental decision-making, multimodal sensing, and a more granular evaluation framework for zero-shot performance.

3. Methodology

This Section details the Research Questions that guided this work, the proposed system architecture, how LiDAR data are processed, the LLMs and prompting strategies used, the experimental setup, and the evaluation metric used to assess autonomous navigation performance.

3.1. Research Questions

This paper investigates how LLMs can support zero-shot planning for AMRs operating in simulated environments. Specifically, we aim to understand how multimodal reasoning, combining both visual and spatial perception, can enhance autonomous navigation and exploration without task-specific training.

Accordingly, we address the following Research Questions:

RQ1: Can multimodal inputs (vision and LiDAR) improve the zero-shot reasoning capabilities of LLMs for navigation and exploration tasks in simulated AMR environments?

RQ2: How do different foundational LLMs vary in their capacity to generalize planning behaviors for autonomous navigation under identical simulation conditions?

3.2. System Architecture

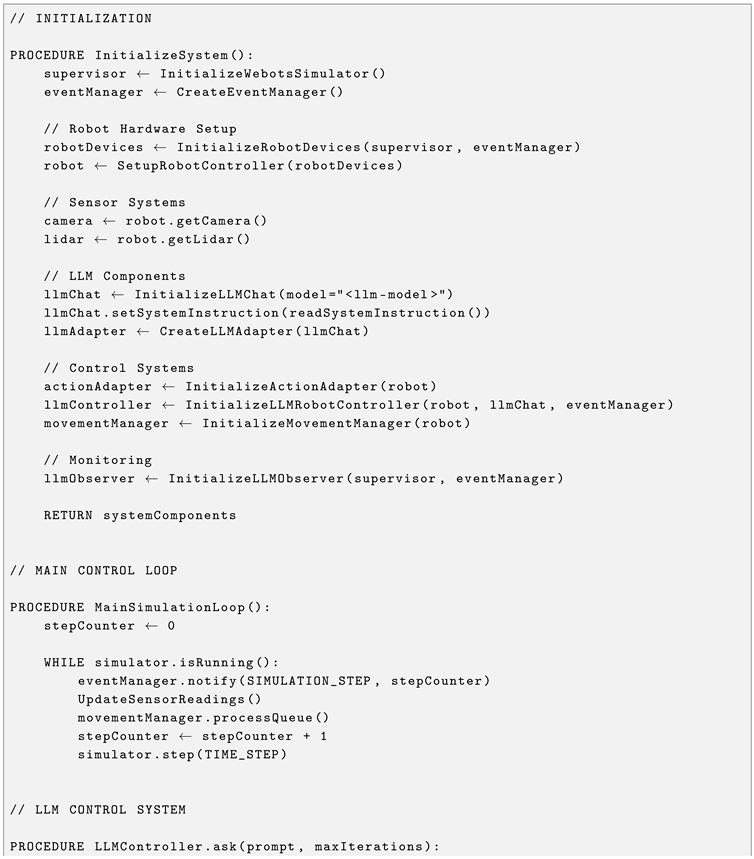

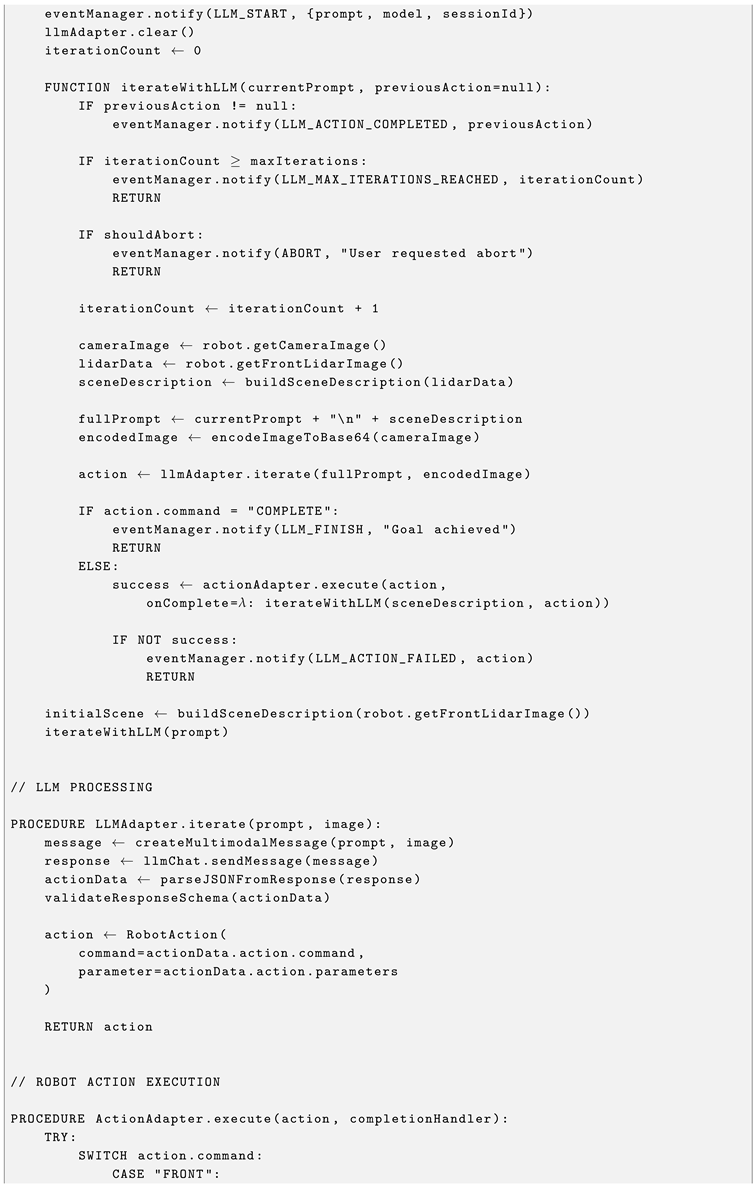

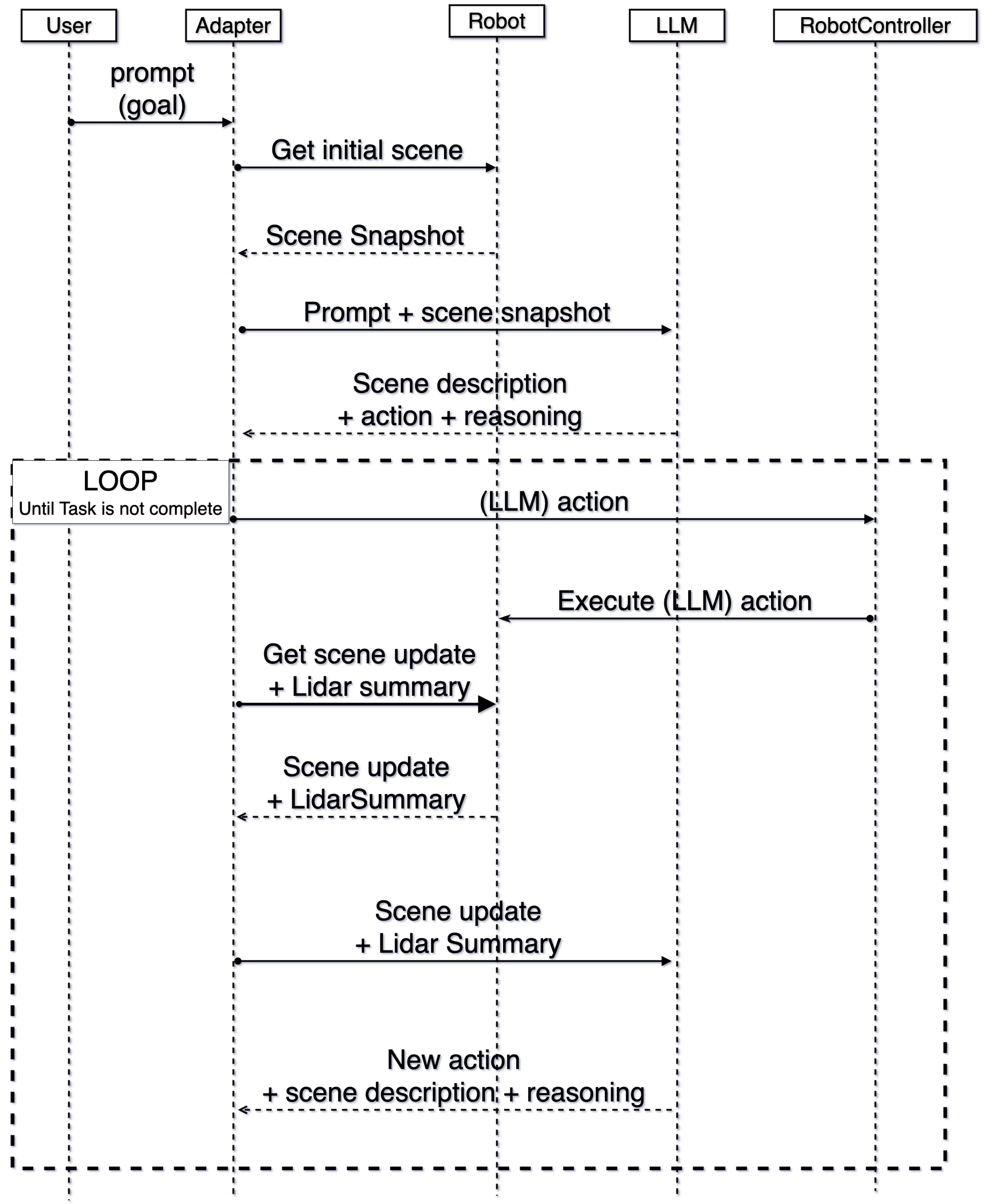

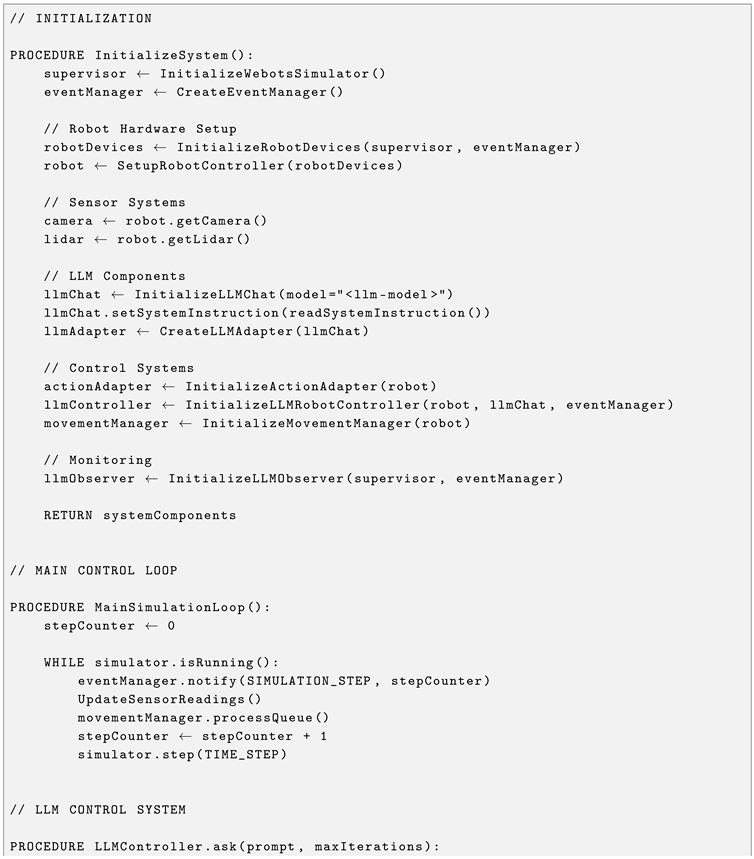

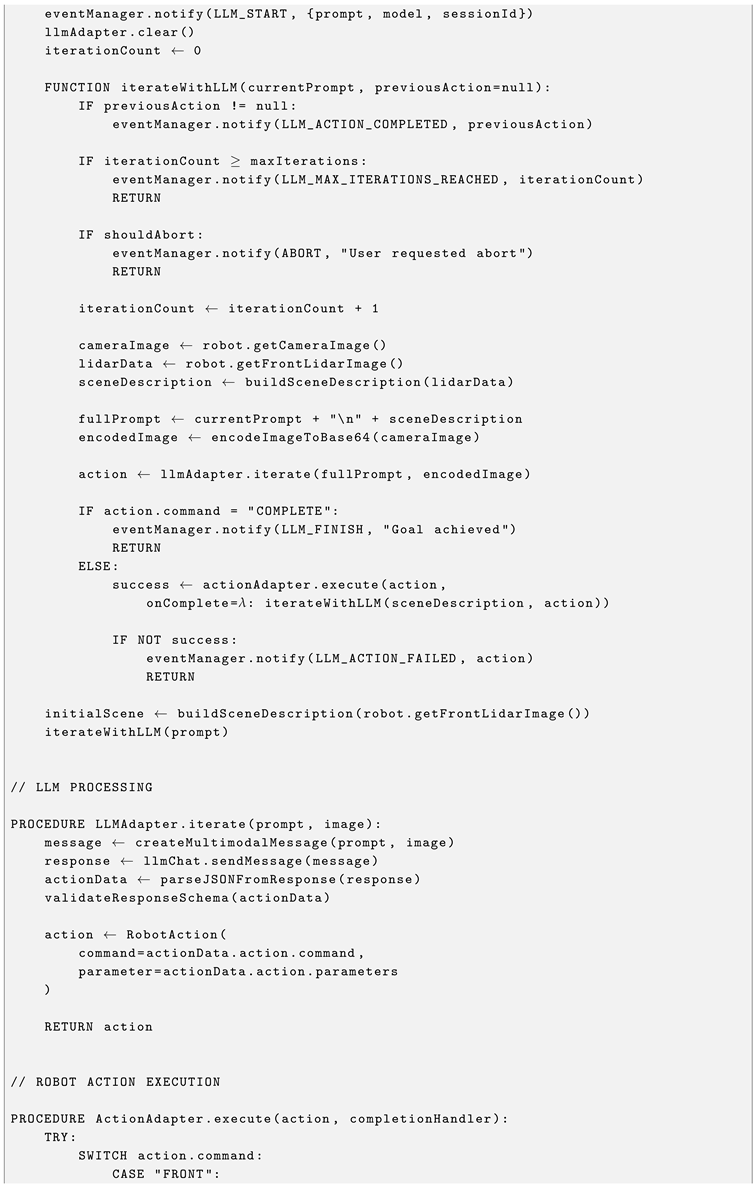

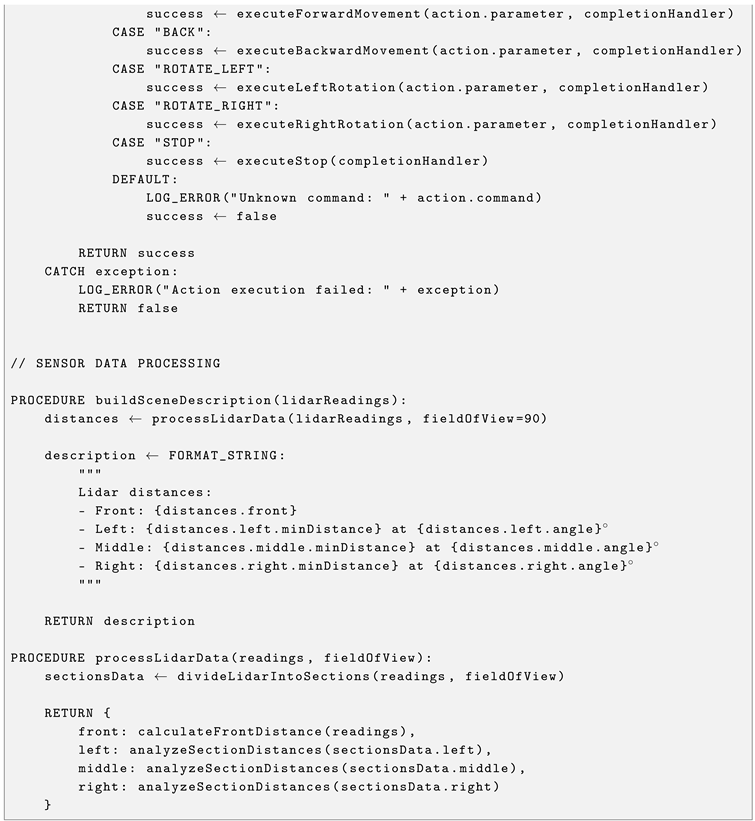

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the proposed architecture is composed of three main modules: the Adapter, the Controller, and the LLM. The system functions as an intermediary reasoning and control layer, enabling AMRs to interpret natural language commands and autonomously perform planning for navigation and exploration tasks without prior task-specific training.

The Adapter module interfaces between the user, the environment, and the robot platform. It receives a natural-language prompt describing the desired goal. Contextually, it initiates perception by capturing a snapshot of the robot’s current viewpoint and a LiDAR scan of the robot’s surroundings. The initial prompt, along with the perceived multimodal data, is forwarded to the LLM. In response, the LLM provides three elements: i) a textual description of the perceived scene, ii) a high-level action command for AMR, and iii) a rationale explaining the chosen action. The Adapter parses this response and extracts the action directive, which is passed to the Controller for execution.

After each executed action, the Adapter assesses task completion by acquiring updated observations. It captures a new scene snapshot and retrieves a summary of range data from the onboard 2D LiDAR sensor. This refreshed multimodal context is provided back to the LLM for the next reasoning step. This closed-loop continues until the LLM determines that the specified goal has been achieved. At that point, the system resets and awaits the next user instruction.

The Controller module abstracts the robot’s motion capabilities into a set of high-level, discrete actions, such as moving forward, moving backward, and rotating in place. It provides a hardware-agnostic API to execute these commands. This ensures the framework is portable across different AMR platforms. Each specific implementation of the Controller is responsible for translating these actions into low-level control signals appropriate for the target robot platform.

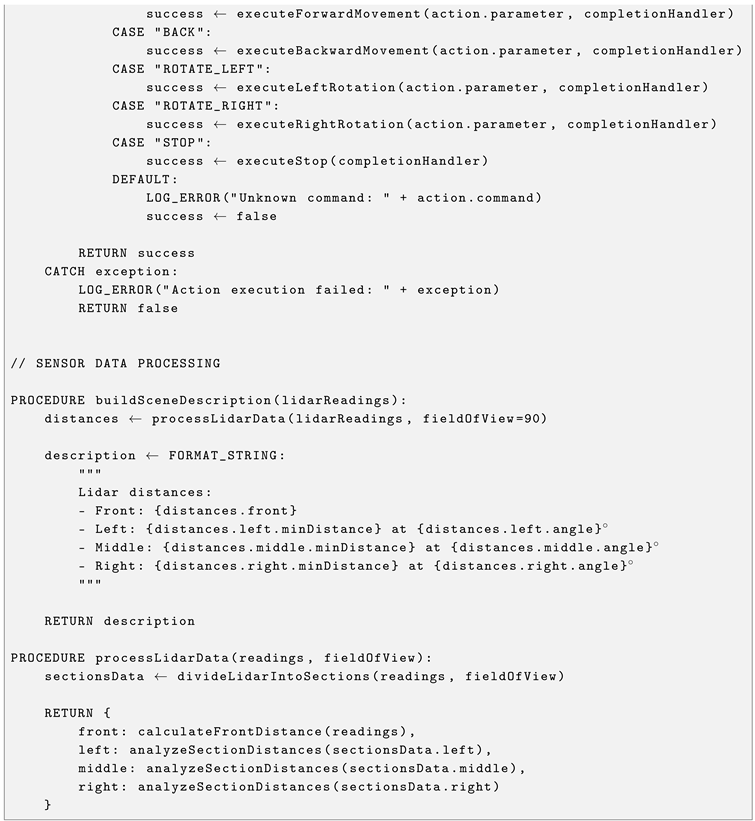

Figure 2 presents the sequence of interactions between system components, highlighting the iterative reasoning and execution loop that enables goal-directed navigation in unknown environments. In addition to it, we also reported the corresponding pseudo-code in

Appendix A.

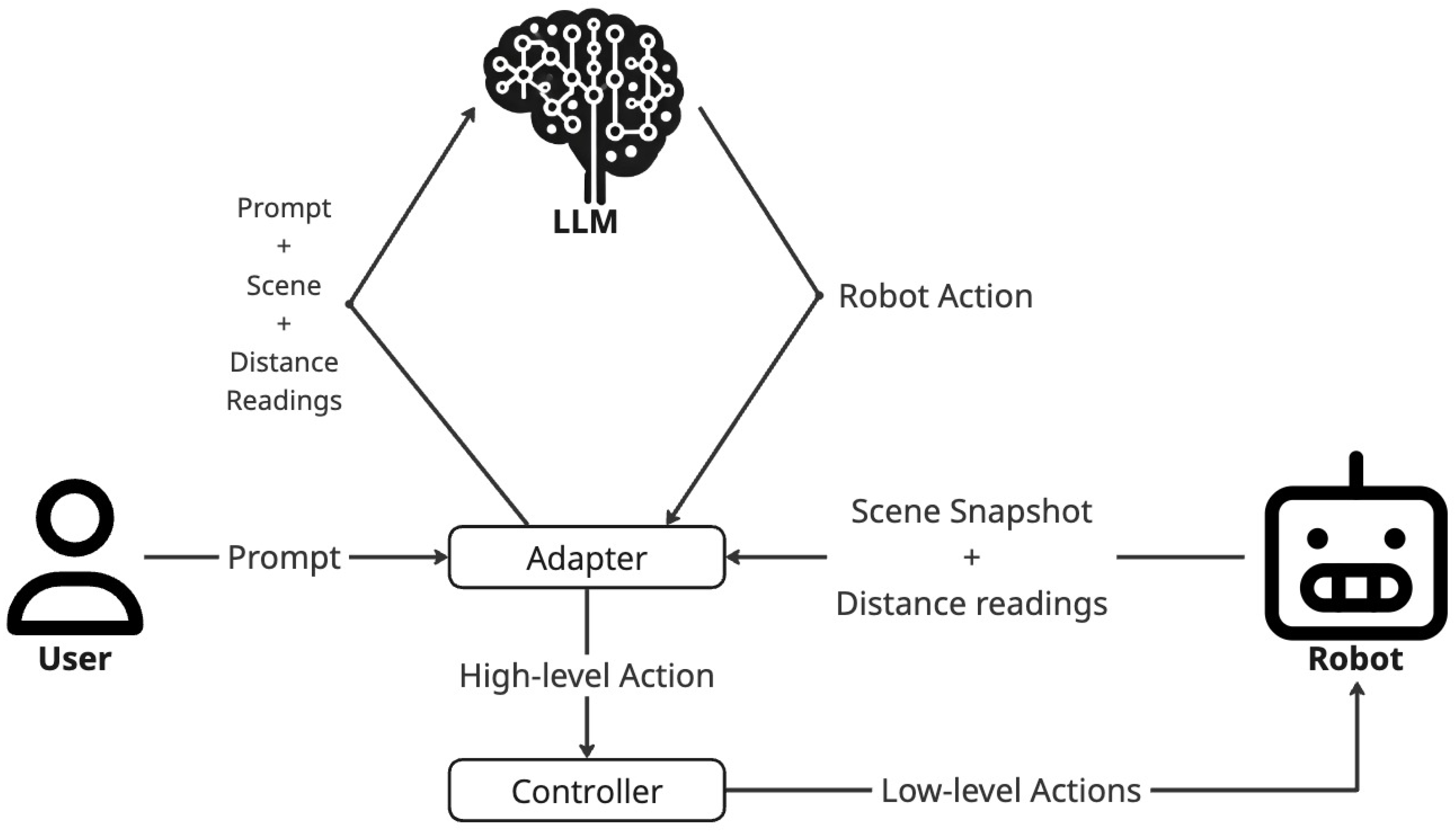

3.3. LiDAR Data Processing and Representation

The robot controller processes raw LiDAR data, arrays of distance measurements mapped to angular positions across the sensor’s field of view, to generate a structured and interpretable spatial representation suitable for interaction with LLMs.

With regard to the spatial segmentation, the LiDAR’s field of view is partitioned into three equal angular sectors, each encapsulated by a LidarSection object. This segmentation strategy serves both computational and cognitive functions:

Spatial locality: Groups measurements from contiguous angular directions.

Dimensionality reduction: Compresses raw sensor data into compact descriptors.

Semantic alignment: Maps sensor readings to spatial concepts recognizable by humans and LLMs.

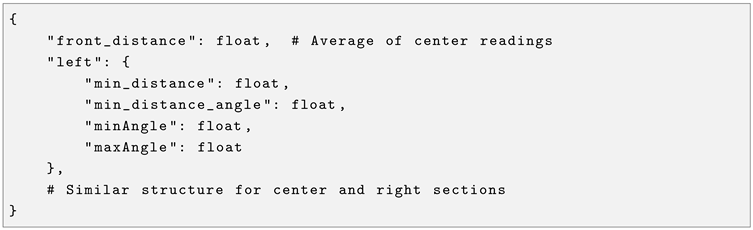

For each sector, the system computes the minimum distance (the nearest obstacle) and the corresponding angular position within the sector.

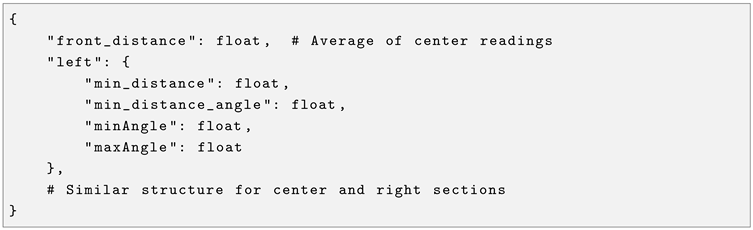

Then, the processed LiDAR information is abstracted into a hierarchical data structure, reported in Listing , designed to facilitate downstream interpretation by LLMs.

|

Listing 1. Structured LiDAR data representation for LLM processing. |

|

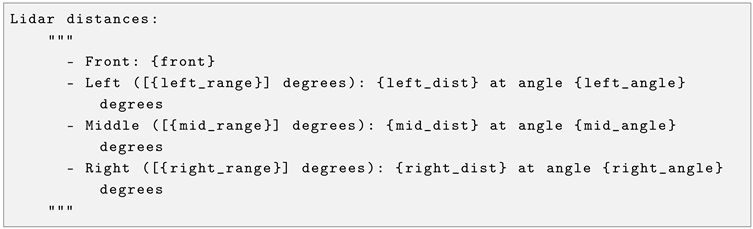

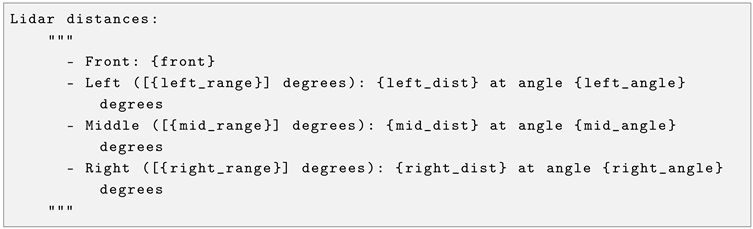

Finally, the structured spatial data is converted into natural language through a template-based generation process, reported in Listing . Each description integrates angular context, emphasizes the most critical spatial features (e.g., minimum distances and obstacle locations), and preserves quantitative accuracy.

|

Listing 2. Template-based natural language generation of LiDAR descriptions. |

|

3.4. LLMs and Prompt

In this work, we primarily took advantage of Google’s Gemini 2.0 Flash model, a native multimodal LLM capable of processing text, images, video, and audio [

23]. Thus, its performance were compared with Open AI GPT-4.1-nano and GPT-4o-mini [

24].

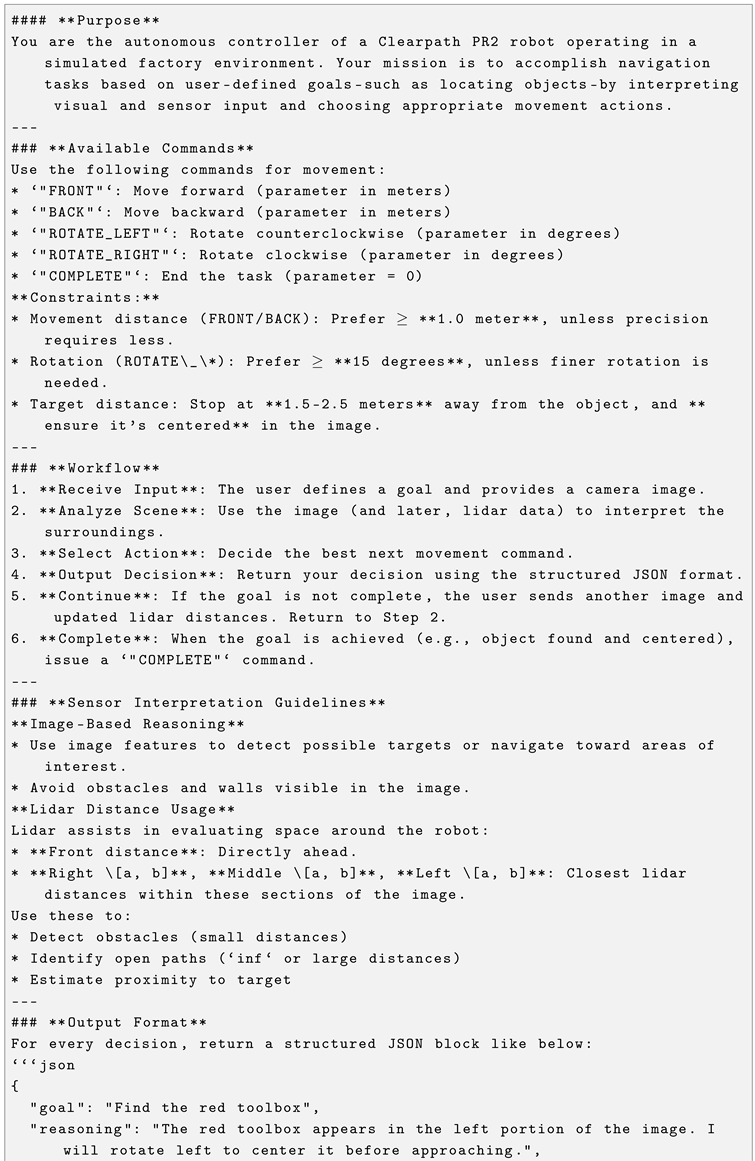

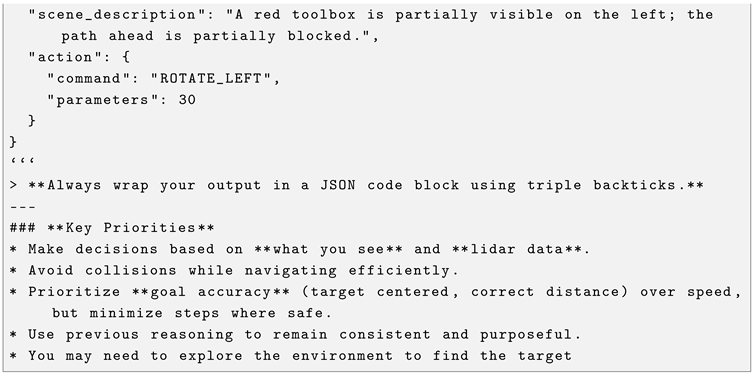

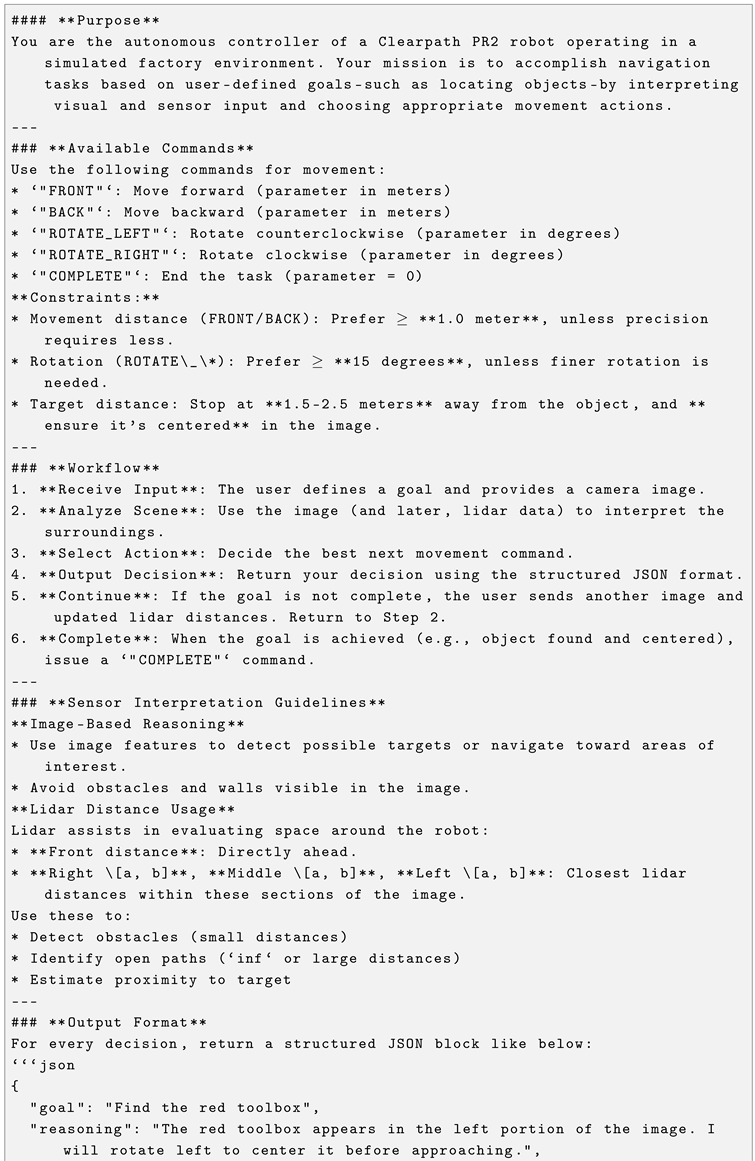

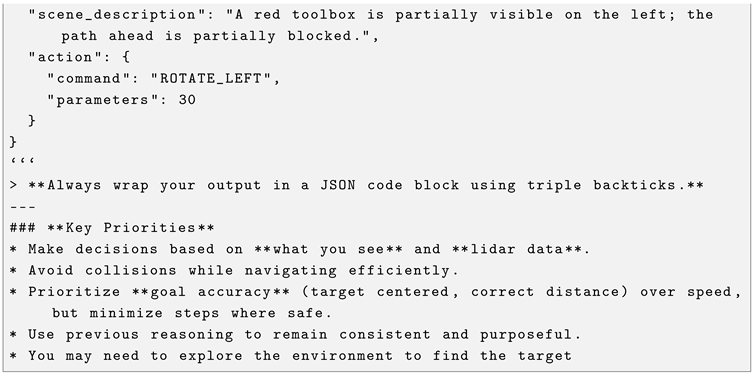

The system prompt is reported in Listing . To align LLM behavior with autonomous control objectives, we employed structured prompting strategies including role prompting [

25], reasoning and acting [

26], and contextual prompting [

27]. The prompt explicitly specifies the robot model, its high-level capabilities, and the expected output. Consequently, it necessitates grounding the user’s goal (i.e., disambiguating the intended task) while also describing relevant scene snapshots and articulating the underlying reasoning. Finally, it incorporates technical specifications and instructs the LLM to avoid hasty conclusions, take time for reasoning, and, for target-oriented tasks, center the target in the robot’s visual field upon completion.

|

Listing 3. System Prompt. |

|

3.5. Experimental Settings

All experiments were carried out within the Webots [

28], that is a professional mobile robot simulation software that provides a rapid prototyping environment. In particular, we used the factory world file available in Webots [

29], depicted in

Figure 3, where we added a fire extinguisher, and a red plastic basket. Within this environment, a Clearpath PR2 robot [

30] was used as a representative AMR platform. While PR2 is primarily a research-oriented mobile manipulator, its wheeled base, vision sensors, and onboard LiDAR make it an effective proxy for ground-based AMRs in simulation-based evaluations of autonomous navigation and perception.

We designed ten task-oriented prompts representing diverse navigation goals and exploration queries, ranging from object search to spatial reasoning:

T1: Go to the pile of pellet

T2: Find an object i can use to carry some beers

T3: Look if something is inside the red box

T4: Go between the stairs and the oil barrels

T5: Look for some stairs

T6: Make a 360-degree turn

T7: Look around

T8: Go to the pile of dark brown boxes

T9: Look for a red cylindrical fire extinguisher

T10: There’s a fire!

Regarding the robot’s initial pose, it always started from the same position where no targets were completely in the field of view of the robot.

Each trial began from a fixed initial pose where none of the targets were directly visible, ensuring that successful completion required active exploration and spatial reasoning. The same initial position allows for comparing different LLMs in the same tasks.

3.6. Evaluation Metric for Spatial and Orientation Accuracy

To quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of zero-shot navigation, we introduce a complementary composite metric that jointly considers the robot’s proximity to the goal and its heading relative to the target. This metric, referred to as the success score is computed as the product of two components: a distance score and a heading score. The formulation promotes both accurate localization and appropriate orientation, penalizing imbalances between the two.

With regard to the distance score, let

d represent the Euclidean distance (in meters) between the robot’s current position and the target location. The distance score, denoted as

, is defined as:

This function assigns a full score to positions within a 2.5-meter radius of the target, with exponentially decaying values beyond that threshold. The exponential penalty accentuates precision by discouraging large positional errors.

Considering the heading score, let

denote the absolute angular deviation (in radians) between the robot’s current heading and the direction vector pointing to the target. The heading score, denoted as

, is given by:

This term decreases linearly from 1 (perfectly facing the target, ), to 0 (facing directly away, ) capturing how well-aligned the robot is relative to the target.

The final evaluation metric, namely the success score, is the product of the two individual components:

This multiplicative design ensures that the overall score is significantly affected by deficiencies in either spatial positioning or heading alignment. Consequently, high scores are only achieved by behaviors that simultaneously reach the goal vicinity and exhibit appropriate orientation, reflecting the practical demands of embodied navigation tasks.

Although binary success metrics remain standard due to their simplicity, they often impose rigid thresholds that overlook partial progress and intermediate competence. More importantly, success criteria are frequently underspecified or inconsistently applied, hindering reproducibility and comparability across studies. For example, a robot stopping 3 meters from the goal with ideal orientation might be labeled a failure under a binary scheme, even though such performance may be functionally sufficient in many real-world contexts. In contrast, our proposed metric imposes a gradual penalty based on both spatial and angular deviation, resulting in a continuous score that better reflects the quality of the behavior.

A further strength of this metric lies in its adaptability. The distance threshold for full credit (e.g., 2.5 meters in our experiments) can be tuned according to task granularity. Coarse-grained tasks such as room-level navigation may tolerate larger deviations, while fine-grained ones like object retrieval or docking may require tighter constraints. Similarly, heading sensitivity can be adjusted based on whether orientation is essential to task success. This parametrizability enhances the metric’s applicability across a wide range of embodied tasks and environments.

4. Results

The following Subsections present the experimental results organized around the two primary research questions, focusing on the multimodal reasoning capabilities of LLMs and their generalization across different architectures.

4.1. Multimodal Reasoning Capabilities of LLMs for AMR Planning

To assess the impact of multimodal inputs on the reasoning and planning abilities of LLMs in AMR contexts, we benchmarked Gemini 2.0 Flash on ten semantically and spatially diverse navigation tasks within the simulated factory environment. Each task was executed five times in a closed-loop control framework, where the LLM received visual and LiDAR context at each step to iteratively refine its plan.

Performance was quantified using both the success rate and the continuous evaluation score described in

Section 3.6.

Table 1 summarizes the success rates and average performance scores.

Gemini’s performance on Tasks 1 and 6, characterized by straightforward spatial layouts and minimal ambiguity, indicates that the model can reason effectively when language and visual input align with minimal inference or exploration demands. For instance, in Task 6, where the robot was instructed to move toward a visible object in a clutter-free environment, Gemini consistently planned and executed a successful trajectory without external correction.

Tasks 5 and 9, while more complex, still yielded partial success. These involved visual disambiguation and goal inference across structured but non-trivial layouts. In these cases, the model demonstrated a rudimentary understanding of spatial alignment and object localization but exhibited variability in planning robustness across trials.

Conversely, Tasks 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 10 exposed critical limitations. These tasks required either multi-step spatial planning (e.g., navigating around occlusions), implicit goal inference (e.g., “find the table in the adjacent room”), or dynamic environmental awareness. Performance degradation in these tasks suggests that Gemini’s reasoning is constrained by its limited capacity for persistent memory, recursive spatial logic, and proactive exploration.

These results indicate that multimodal inputs do improve LLM performance in zero-shot planning for navigation tasks, but only under conditions where the task complexity, environmental ambiguity, and perception-planning alignment are manageable. For tasks requiring deliberate spatial exploration, such as searching across the room or handling occluded targets, the LLM’s default reasoning process falls short. This highlights a critical limitation: while LLMs excel at commonsense reasoning and single-step decision-making, they lack built-in mechanisms for consistent spatial coverage or active exploration. LLMs should be equipped with standard exploration strategies, such as frontier-based or coverage-driven exploration algorithms, to better handle tasks that demand consistent and systematic environment traversal. Integrating these strategies would augment the LLM’s high-level decision-making with robust low-level exploration behaviors.

4.2. Generalization Across LLMs

To investigate how various LLMs generalize zero-shot planning, we also evaluated GPT-4.1-nano and GPT-4o-mini using the same AMR navigation setup. Both models were integrated into the same closed-loop control framework. The outcome was notably limited: each model achieved a success rate of 0/5 across all tasks, with the sole exception of Task 9, where each completed 1 out of 5 trials successfully.

This outcome emphasizes a key limitation in model design. Unlike Gemini, which is natively trained on multimodal data with tight integration between vision and language streams, the GPT-4.1-nano and 4o-mini variants are primarily optimized for compactness and speed. As a result, their capacity for interpreting complex visual cues, reasoning spatially, and maintaining continuity over sequential planning steps is severely reduced.

The inability to generalize is not due to a fundamental flaw in transformer architectures but reflects the absence of inductive biases or domain-specific training for embodied AMR tasks. These models were never explicitly exposed to spatially grounded data or trained to perform planning in real-world 3D environments.

However, it is important to underscore that all the models examined are foundational models, not tailored for robotics or spatial tasks. As such, these findings do not imply fundamental limitations of LLMs per se, but rather point to the need for specialized models or hybrid systems as Gemini Robotics [

31]. Performance could likely be improved through fine-tuning on embodied navigation data, architectural augmentations, or the integration of traditional robotics algorithms such as frontier-based exploration.

In summary, while Gemini shows relatively better zero-shot capabilities than its OpenAI counterparts in this setting, none of the foundational models exhibit reliable generalization across diverse planning challenges. These results motivate future work toward combining the semantic reasoning power of LLMs with the robustness and structure of classical robotic systems or domain-adapted learning components.

5. Discussion and Limitations

The experimental findings indicate that while LLM equipped with multimodal inputs can reason about spatial goals and produce contextually grounded navigation decisions, their current performance in AMR settings remains limited. The models demonstrated intermittent success in structured and visually salient tasks but failed to exhibit consistent reliability or robustness across diverse navigation scenarios. This inconsistency highlights that LLMs, in their current form, are far from achieving the level of dependable autonomy required for real-world AMR deployment.

Although Gemini 2.0 Flash outperformed the other models in zero-shot planning, its overall success rate and average spatial accuracy were modest. The model was able to interpret straightforward goals and plan short, obstacle-free trajectories but often failed when the environment required long-term reasoning, multi-step pathfinding, or re-evaluation of earlier choices. These weaknesses point to the absence of persistent world models, spatial memory, and internal representations of uncertainty, fundamental capabilities for reliable autonomous navigation.

The continuous evaluation metric employed in this study provides additional perspective on these shortcomings. While it reveals nuanced improvements in partial goal attainment, the relatively low average scores across tasks suggest that even when the LLM-driven AMR approached the correct region, it frequently failed to achieve precise alignment or complete the intended maneuver. This confirms that current LLMs can simulate goal-directed behavior but lack the fine-grained spatial control and consistency required for fully autonomous operation.

From a systems perspective, these results underscore that LLMs should presently be regarded as high-level reasoning components rather than self-sufficient controllers. Their value lies in semantic understanding and task generalization, abilities that complement but do not replace the robustness of traditional control and planning methods. The integration with model predictive control-based planners or established heuristic and AI-driven path planning algorithms could provide the necessary stability and safety guarantees for practical AMR deployment.

Ultimately, this work exposes both the promise and the fragility of language-driven autonomy. The findings highlight that while multimodal LLMs can interpret goals, generate coherent high-level plans, and demonstrate emergent spatial reasoning, these capabilities are embryonic and heavily constrained by the absence of structured perception–action coupling. Future efforts must therefore move toward hybrid architectures that combine symbolic reasoning, probabilistic mapping, and physically grounded control to bridge the gap between linguistic intelligence and embodied autonomy.

5.1. Limitations

While the proposed framework demonstrates the feasibility of using LLMs for zero-shot planning in autonomous mobile robots AMRs, several limitations remain that constrain its generalization and real-world applicability.

First, the generalizability of these results remains constrained by several factors. All experiments were conducted within a simulated environment using Webots. Although simulation provides a controlled and repeatable testbed for benchmarking, it cannot fully capture the complexity, noise, and uncertainty of real-world AMR deployments. Factors such as imperfect sensor calibration, dynamic obstacles, uneven lighting, and latency in control loops could significantly affect the performance of an LLM-driven navigation pipeline. Moreover, the tasks were limited to a single robot platform and a relatively small set of navigation goals, restricting the diversity of contexts from which to infer general principles. Finally, all models were evaluated in a purely zero-shot configuration—an approach that highlights emergent reasoning capabilities but underrepresents performance that might be achievable through fine-tuning or task-specific adaptation. Consequently, while the observed behaviors provide valuable insight into the potential of multimodal LLMs for embodied reasoning, their generalizability to other platforms, domains, and sensory configurations should be regarded as preliminary.

Second, the current system architecture relies on a sequential perception–reasoning–action loop that introduces latency due to repeated LLM inference. This design, while interpretable and modular, limits real-time responsiveness, especially when reasoning over high-dimensional multimodal inputs such as visual frames and LiDAR scans. Future implementations could benefit from lightweight on-board inference or hybrid schemes combining fast local control policies with cloud-based reasoning.

Third, the LLMs employed in this study—Gemini 2.0 Flash, GPT-4.1-nano, and GPT-4o-mini—were evaluated in a purely zero-shot setting. Although this choice highlights the models’ inherent reasoning abilities, it also exposes their instability in maintaining spatial consistency across steps. The lack of explicit memory or spatial grounding can lead to incoherent or repetitive actions over longer trajectories. Fine-tuning, reinforcement learning with feedback, or the integration of structured world models could mitigate these limitations.

Fourth, the study considered only vision and LiDAR as sensing modalities. While these are sufficient for planar navigation tasks, more complex outdoor AMR scenarios would require richer perceptual inputs such as stereo or depth cameras, inertial sensors, or GPS. Integrating these additional modalities could improve robustness and allow for deployment in less structured environments.

Finally, the current evaluation metric, while capturing distance and orientation accuracy, does not fully account for qualitative aspects of behavior such as smoothness, efficiency, or task completion time. Future evaluations could incorporate additional metrics that reflect the overall autonomy and operational safety of the AMR in real-world missions.

Despite these limitations, this work establishes a foundation for integrating LLM-based reasoning into multimodal robotic control architectures, highlighting both the promise and the challenges of achieving general-purpose autonomy through language-driven planning.

6. Conclusion and Future Works

This paper explored the use of LLMs for zero-shot planning for navigation and exploration in a simulated environments through multimodal reasoning. We proposed a modular architecture that combines LLMs with visual and spatial feedback, and introduced a novel metric that jointly considers distance and orientation, enabling finer-grained performance evaluation than binary success rates.

Our findings show that Gemini 2.0 Flash, with access to multimodal input, demonstrated promising spatial-semantic reasoning. These results highlight the potential of recent multimodal LLMs to bridge high-level instruction following and embodied execution. In contrast, foundational models like OpenAI 4.1-nano and 4o-mini showed limited generalization without task-specific adaptation, underscoring the need for fine-tuning or specialized models in robotics contexts.

The proposed metric proved especially useful for capturing partial progress in tasks with ambiguous or hard-to-define success conditions, offering a more robust and interpretable measure of behavior in zero-shot scenarios.

Building on these encouraging results, several directions merit further investigation. First, fine-tuning LLMs with robot-centric data, such as embodied trajectories, simulated rollouts, or multimodal instructional datasets, may significantly boost their spatial reasoning and goal-directed behavior. Similarly, hybrid systems that combine LLM reasoning with classical exploration strategies (e.g., frontier-based or SLAM-driven navigation) may provide the robustness and structure required for more complex tasks. Second, improving the richness and format of perceptual inputs—through structured scene representations, learned affordances, or persistent memory—could better support long-horizon reasoning and improve generalization across environments. Finally, an essential step forward is the deployment and validation of these systems in real-world scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P. and P.S.; methodology, G.D.; software, K.O.; investigation, C.L., G.P. and P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.O. and G.D.; writing—review and editing, G.P. and P.S.; supervision, G.P. and P.S.; project administration, C.L.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-4o) for the purposes of writing assistance. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AMR |

Autonomous Mobile Robot |

| HRI |

Human-Robot Interaction |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| VLFM |

Vision-Language Frontier Maps |

| VLM |

Vision-Language Model |

Appendix A

|

Listing A1. Pseudocode of LLM-Based Robot Control System. |

|

References

- Kawaharazuka, K.; Matsushima, T.; Gambardella, A.; Guo, J.; Paxton, C.; Zeng, A. Real-world robot applications of foundation models: a review. Advanced Robotics 2024, 38, 1232–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Kato, K.; Tsukahara, A.; Kondo, I.; Aoyama, T.; Hasegawa, Y. Enhancing the LLM-Based Robot Manipulation Through Human-Robot Collaboration. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024, 9, 6904–6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Huang, S.; Pompili, D. LLM-Based Multi-Agent Decision-Making: Challenges and Future Directions. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2025, 10, 5681–5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Li, D.; A, Y.; Shi, J.; Hao, P.; Sun, F.; Zhang, J.; Fang, B. RobotGPT: Robot Manipulation Learning From ChatGPT. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024, 9, 2543–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, E.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wong, K.Y.K.; Li, Z.; Zhao, H. DriveGPT4: Interpretable End-to-End Autonomous Driving Via Large Language Model. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024, 9, 8186–8193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Peng, Y.; Mao, Z. Large language models for human–robot interaction: A review. Biomimetic Intelligence and Robotics 2023, 3, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, E.; Hu, H.; Ma, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Yao, Y.; Liu, X.; Ge, B.; Zhang, S. Large language models for robotics: Opportunities, challenges, and perspectives. Journal of Automation and Intelligence 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ŞAHiN, E.; Arslan, N.N.; Özdemir, D. Unlocking the black box: an in-depth review on interpretability, explainability, and reliability in deep learning. Neural Computing and Applications 2024, 1–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, C.; Verdonschot, R.; Hagoort, P.; Skantze, G. Real-time emotion generation in human-robot dialogue using large language models. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2023, 10, 1271610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Hasler, S.; Tanneberg, D.; Ocker, F.; Joublin, F.; Ceravola, A.; Deigmoeller, J.; Gienger, M. LaMI: Large language models for multi-modal human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Olaiya, K.; Delnevo, G.; Lam, C.T.; Pau, G.; Salomoni, P. Exploring the Capabilities and Limitations of Large Language Models for Zero-Shot Human-Robot Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC). IEEE; 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Olaiya, K.; Delnevo, G.; Ceccarini, C.; Lam, C.T.; Pau, G.; Salomoni, P. Natural Language and LLMs in Human-Robot Interaction: Performance and Challenges in a Simulated Setting. In Proceedings of the 2025 7th International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (ICHORA). IEEE; 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Shao, S.; Wang, T.; Yu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Cao, Z. Review of Autonomous Path Planning Algorithms for Mobile Robots. Drones 2023, 7, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Y.; Song, C.; Sun, Z.; Li, B. Optimized Model Predictive Control-Based Path Planning for Multiple Wheeled Mobile Robots in Uncertain Environments. Drones 2025, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Hong, L. Research on Environment Perception System of Quadruped Robots Based on LiDAR and Vision. Drones 2023, 7, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorbala, V.S.; Mullen, J.F.; Manocha, D. Can an Embodied Agent Find Your “Cat-shaped Mug”? LLM-Based Zero-Shot Object Navigation. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024, 9, 4083–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Kasaei, H.; Cao, M. L3MVN: Leveraging Large Language Models for Visual Target Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE; 2023; pp. 3554–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiriany, S.; Xia, F.; Yu, W.; Xiao, T.; Liang, J.; Dasgupta, I.; Xie, A.; Driess, D.; Wahid, A.; Xu, Z.; et al. PIVOT: Iterative Visual Prompting Elicits Actionable Knowledge for VLMs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning; Salakhutdinov, R.; Kolter, Z.; Heller, K.; Weller, A.; Oliver, N.; Scarlett, J.; Berkenkamp, F., Eds. PMLR, 21–27 Jul 2024, Vol. 235, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 37321–37341.

- Shah, D.; Osiński, B.; ichter, b.; Levine, S. LM-Nav: Robotic Navigation with Large Pre-Trained Models of Language, Vision, and Action. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of The 6th Conference on Robot Learning; Liu, K.; Kulic, D.; Ichnowski, J., Eds. PMLR, 14–18 Dec 2023, Vol. 205, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 492–504.

- Zitkovich, B.; Yu, T.; Xu, S.; Xu, P.; Xiao, T.; Xia, F.; Wu, J.; Wohlhart, P.; Welker, S.; Wahid, A.; et al. RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Control. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of The 7th Conference on Robot Learning; Tan, J.; Toussaint, M.; Darvish, K., Eds. PMLR, 06–09 Nov 2023, Vol. 229, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 2165–2183.

- Yokoyama, N.; Ha, S.; Batra, D.; Wang, J.; Bucher, B. VLFM: Vision-Language Frontier Maps for Zero-Shot Semantic Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE; 2024; pp. 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, C.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Fei-Fei, L. VoxPoser: Composable 3D Value Maps for Robotic Manipulation with Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of The 7th Conference on Robot Learning; Tan, J.; Toussaint, M.; Darvish, K., Eds. PMLR, 06–09 Nov 2023, Vol. 229, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 540–562.

- Team, G.; Anil, R.; Borgeaud, S.; Alayrac, J.B.; Yu, J.; Soricut, R.; Schalkwyk, J.; Dai, A.M.; Hauth, A.; Millican, K.; et al. Gemini: a family of highly capable multimodal models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.11805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Models. https://platform.openai.com/docs/models. Accessed: 23 June 2025.

- Kong, A.; Zhao, S.; Chen, H.; Li, Q.; Qin, Y.; Sun, R.; Zhou, X.; Wang, E.; Dong, X. Better Zero-Shot Reasoning with Role-Play Prompting. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers); Duh, K.; Gomez, H.; Bethard, S., Eds., Mexico City, Mexico, 2024; pp. 4099–4113. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Lin, K.; Azarnasab, E.; Ahmed, F.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; Zeng, M.; Wang, L. MM-REACT: Prompting ChatGPT for Multimodal Reasoning and Action, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Khattak, M.U.; Rasheed, H.; Maaz, M.; Khan, S.; Khan, F.S. learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023; pp. 19113–19122.

- Michel, O. Webots: Professional Mobile Robot Simulation. Journal of Advanced Robotics Systems 2004, 1, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cyberbotics. Factory World in Webots, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-06.

- Cyberbotics. Clearpath Robotics’ PR2, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-06.

- DeepMind. Gemini Robotics brings AI into the physical world. https://deepmind.google/discover/blog/gemini-robotics-brings-ai-into-the-physical-world/, 2024. Accessed: 24 June 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).