Submitted:

05 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Scaling Effects

2. Drag Reduction in Avian

2.1. Structural and Physical Characteristics of Avian

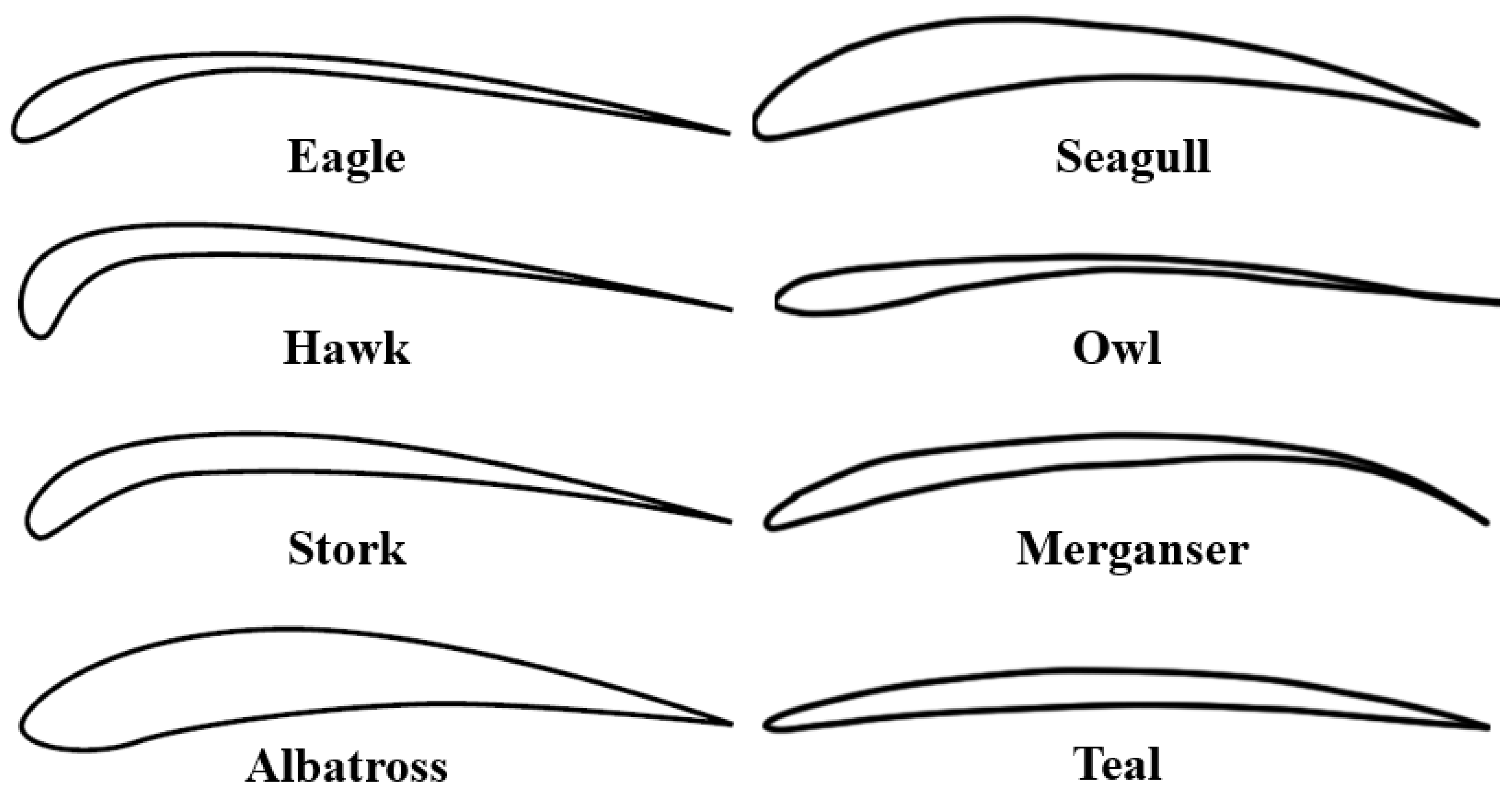

2.1.1. Wing Shape, Airfoils, and Morphing Capabilities

Aerodynamics and Ecomorphology of Avian Wings

Aerodynamics of Aircraft Wings

Application to Flapping Micro Air Vehicles (FMAVs)

Advanced Wing Morphing Technologies

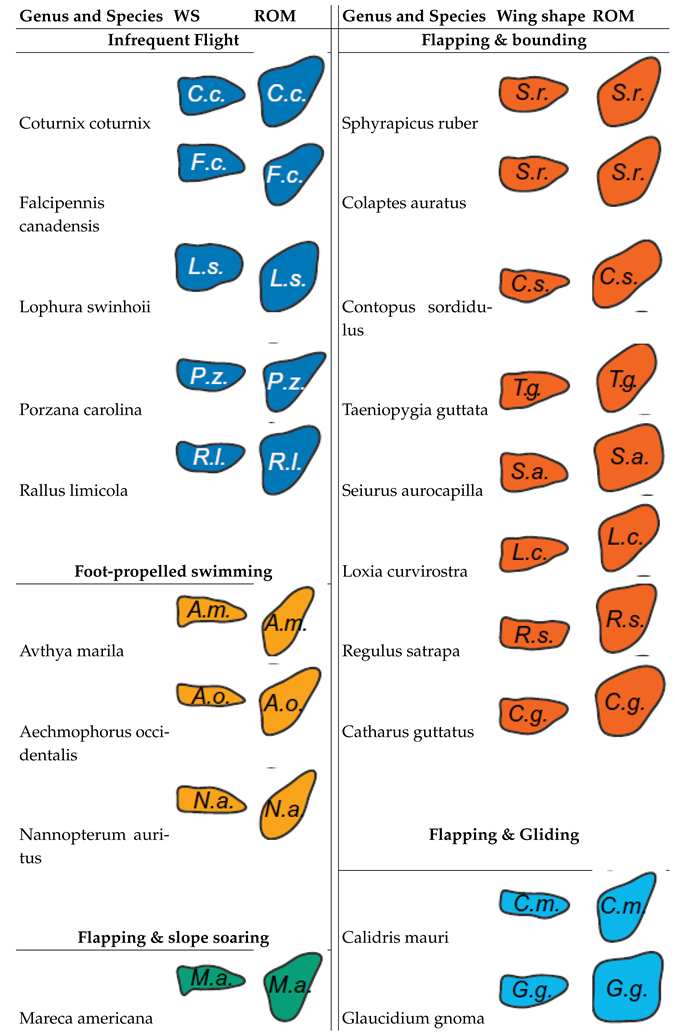

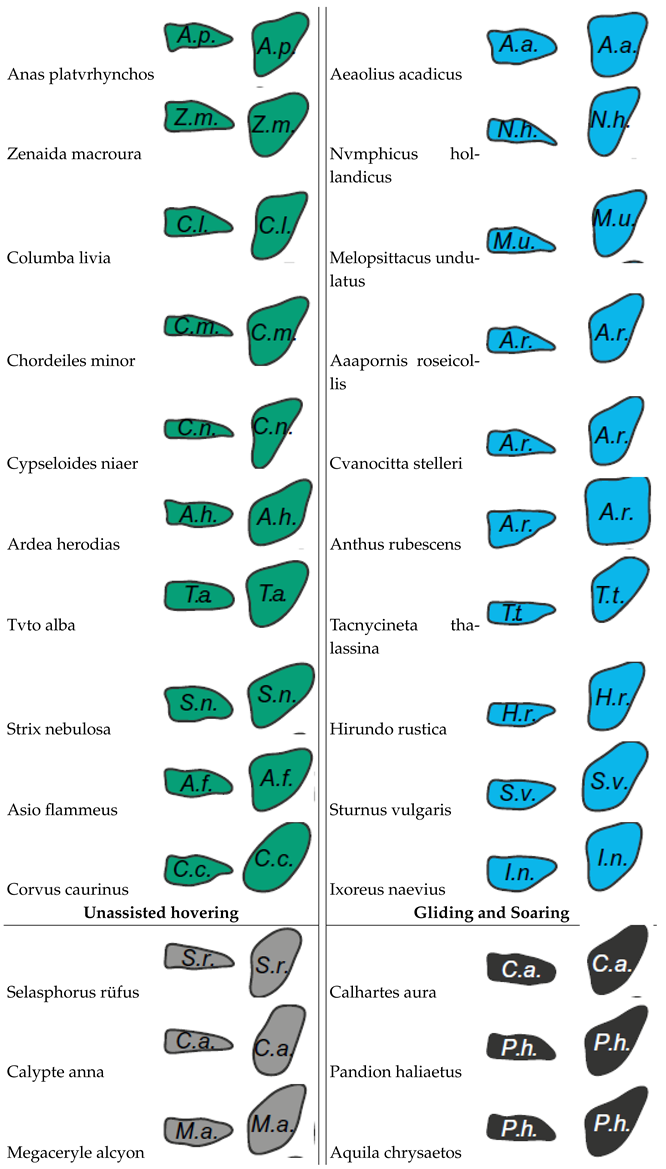

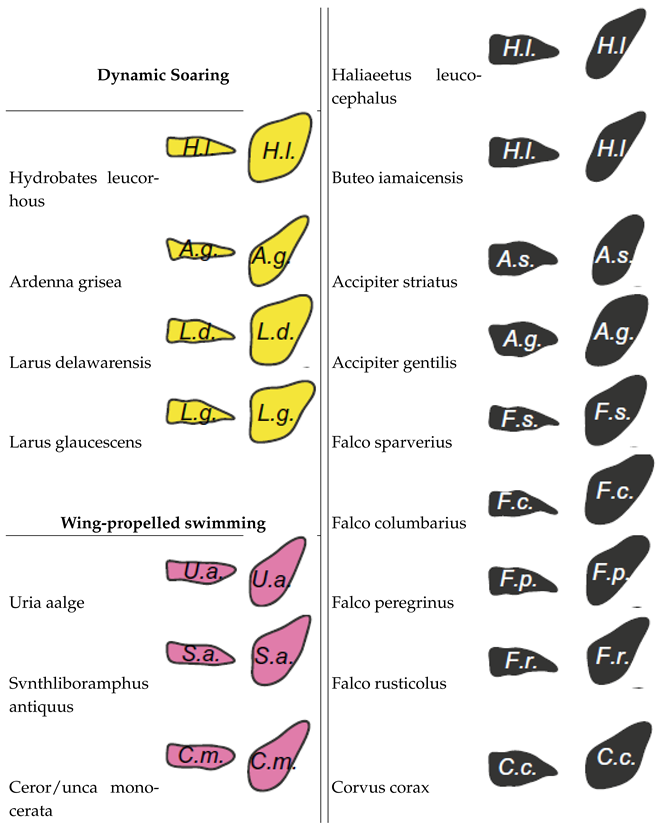

The Influence Of Flight Style On The Aerodynamic Properties Of Avian Wings As Fixed Lifting Surfaces

State of Morphing Wing Research

Engineering Analysis of Avian Flight

Bio-Inspired Flapping Kinematics

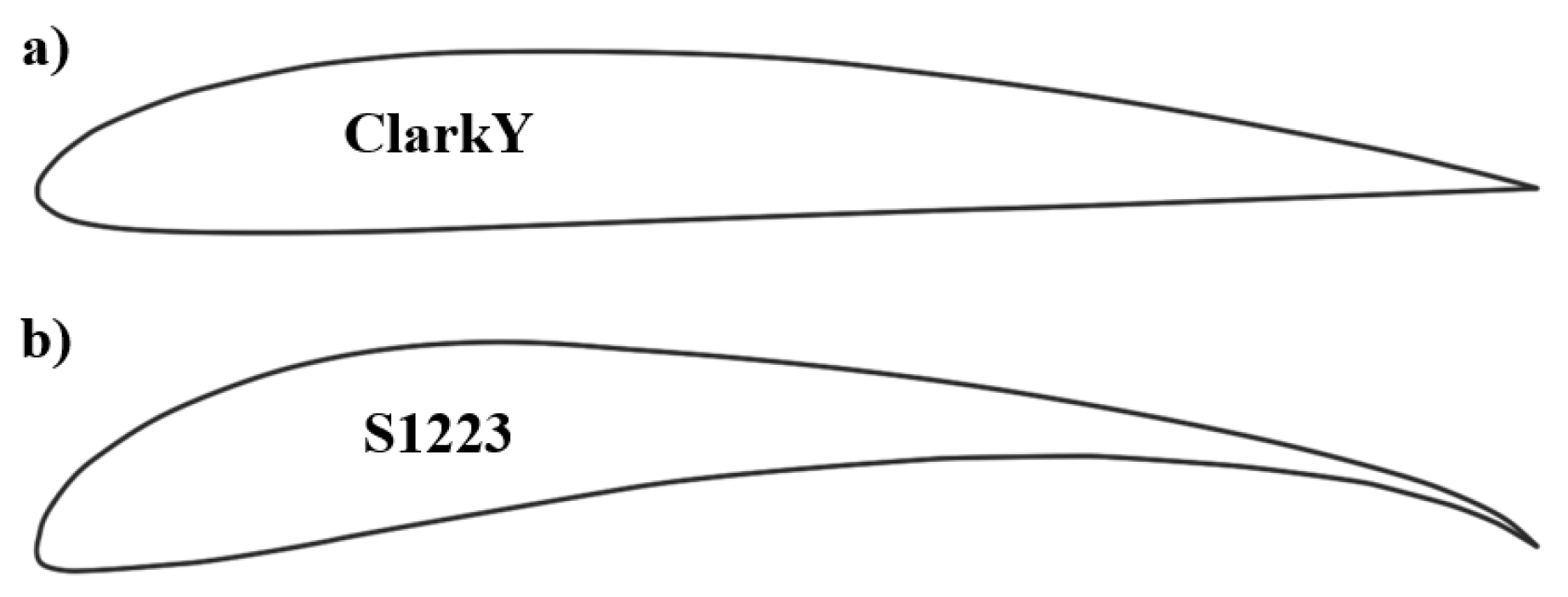

Avian Airfoil Characterisitic

Bird-Inspired Airfoil Design Approach

Evolutionary Innovations in Avian Wings

Dynamic Airfoil Morphology of Birds

Numerical Insights into Bird Airfoil Efficiency

Biological Insights into MAV Design

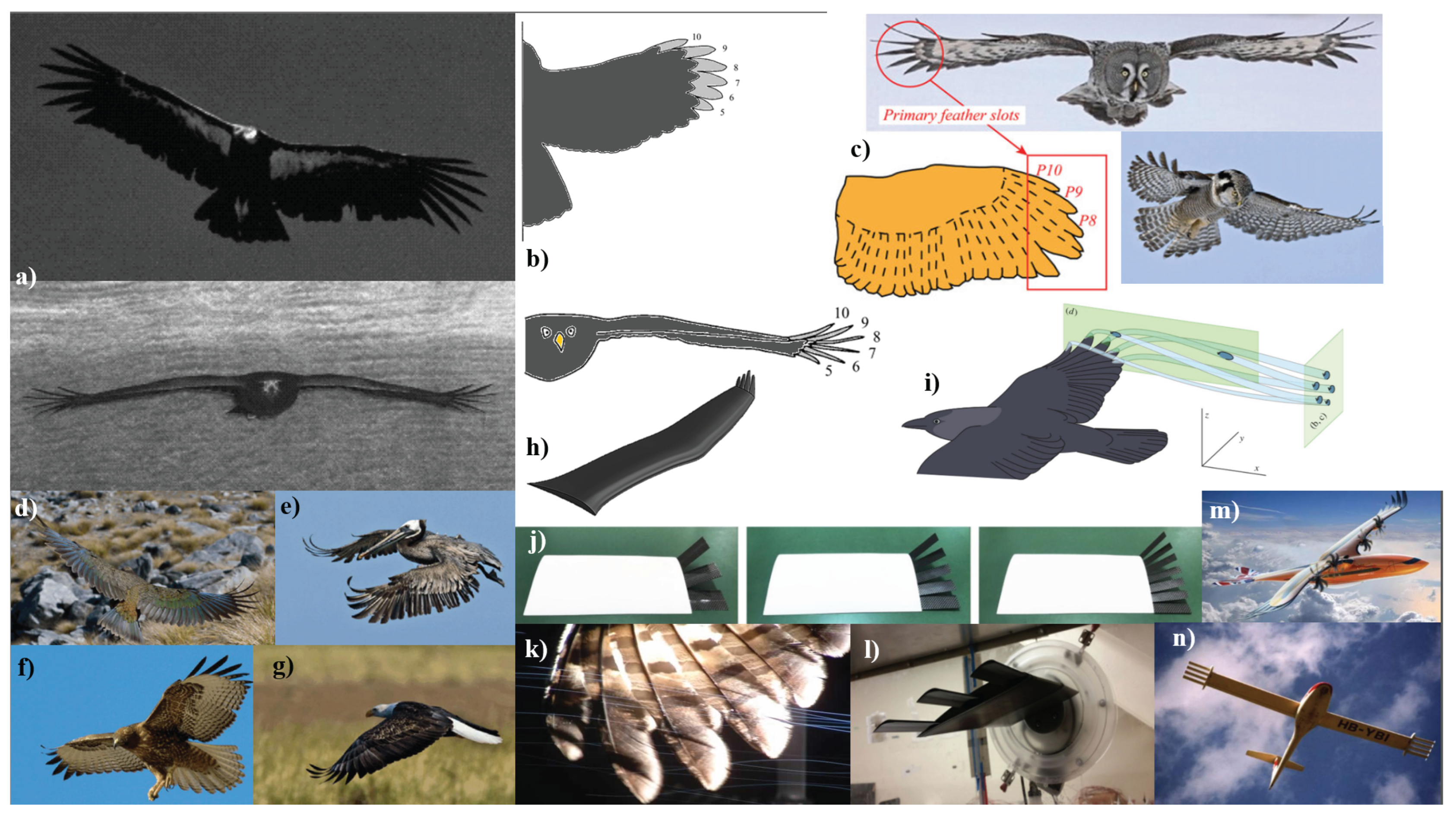

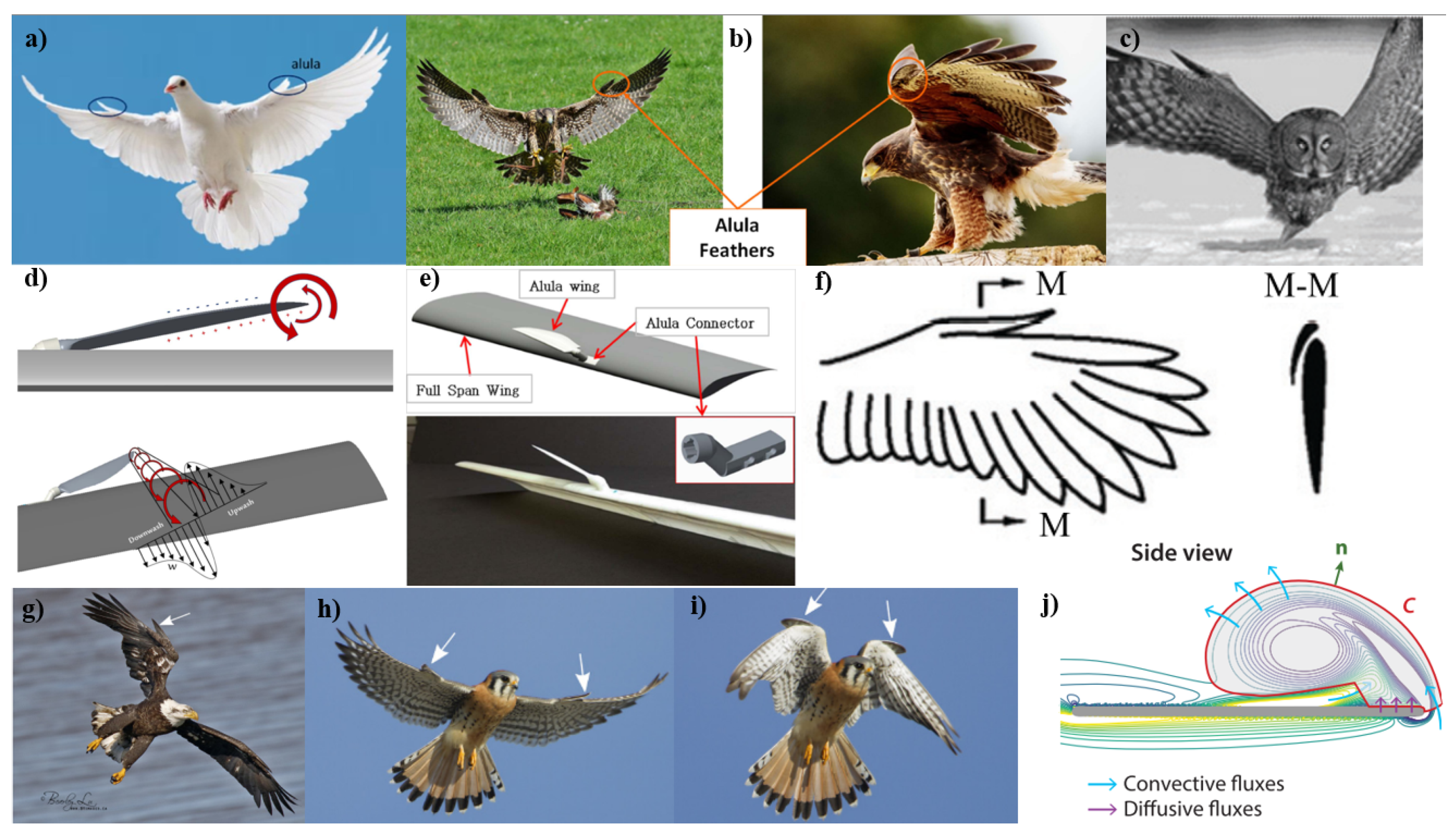

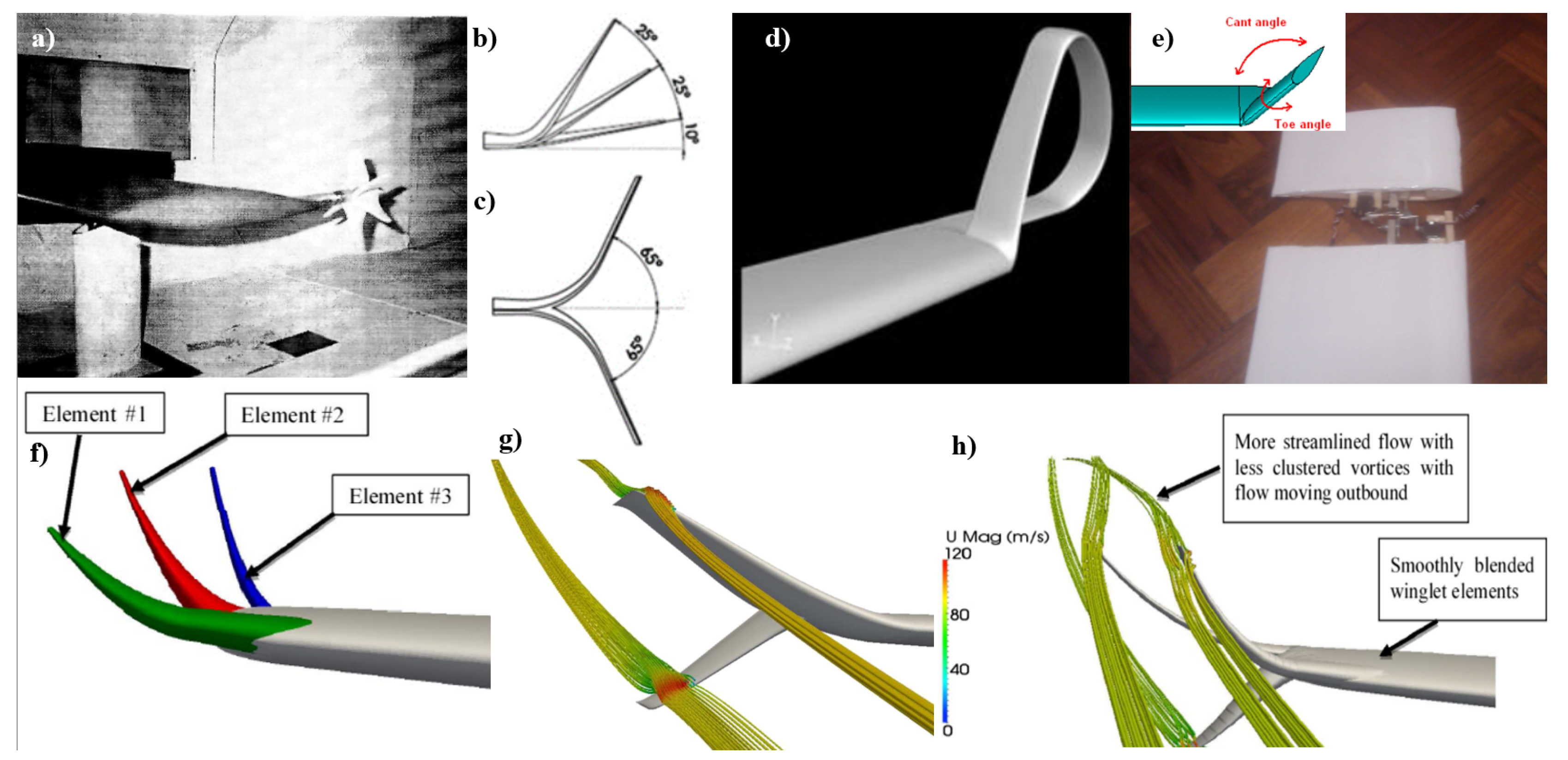

2.1.2. Wingtips and Winglets

Aerodynamic Performance of Wingtip Slots and Research Prospect

Aerodynamics and Ecomorphology of Flexible Feathers and Morphing Wings

Aerodynamic Analysis of Bionic Winglet-Slotted Wings

Varying Wingtip Devices

Study Methodology and Winglet Designs

Experimental Optimization of a Wingtip Vortex Turbine

Gliding Harris’ Hawk Wingtip Slots

Wingtip Vortices in Flapping Wings

A Numerical Study of a Biomimetic Wing in Soaring Flight

2.1.3. Feather’s Structure and Riblets

Pioneering Research on Bird Feather Structures for Drag Reduction

Insights from Various Biological Surfaces

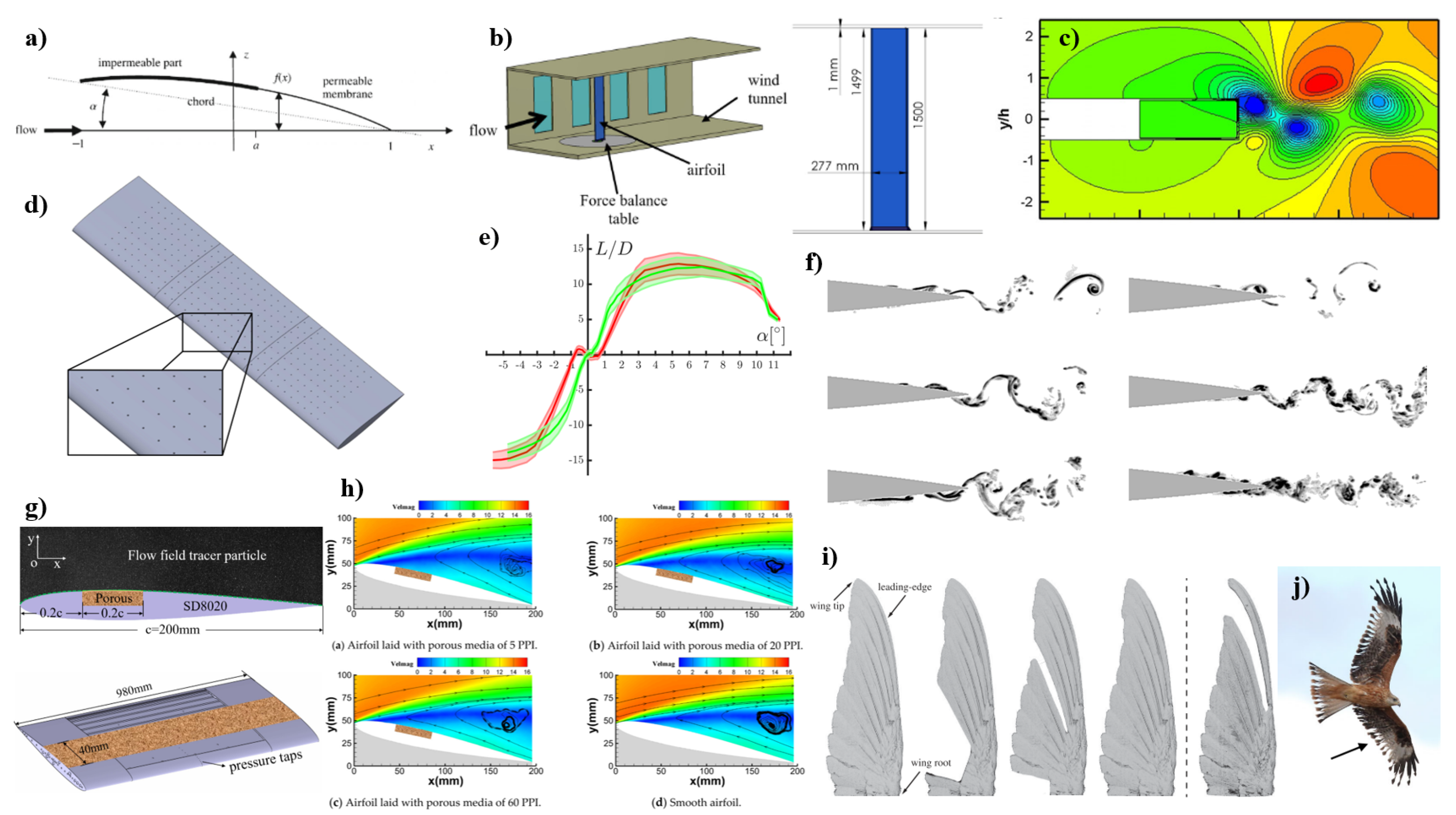

2.1.4. Moult and Porosity of the Wings

Permeable Airfoils

Biomimetic Self-Adaptive Porous Flaps

Effects of Wing Damage and Molt Gaps Flight Performance

Passive Separation Control by Acoustic Resonance

2.1.5. Body Shape

Evolutionary Advantage

Estimates of Body Drag During Dives

Hydrodynamics in Diving Birds

Experimental Challenges in Aerodynamics Research

2.1.6. Beak Shape

Morphological and Ecological Correlations

2.1.7. Color of the Feathers

Avian Wing Coloration and Flight Efficiency

| Bird |

Weight (g) |

Wingspan (cm) |

Body length (cm) |

Aspect ratio |

Wing loading (N/m2) |

Flapping frequency (Hz) |

Max flight altitude (m) |

| Alpine Chough |

188–252 | 75–85 | 37–39 | 6.40 | 21.8 | - | 8,000 |

| Whooper Swan |

8500-10000 | 218-243 | 145-160 | 8.7 | 175 | 3.44 | 8,200 |

| Avocets | 260-290 | 77-80 | 42-45 | - | - | - | 3,000 |

| Yellow-billed Magpie |

150-170 | 61 | 43-54 | - | - | - | - |

| Pied Crow | 520 | 328-388 | 46-52 | - | - | - | - |

| Australian Magpie |

220-350 | 65-85 | 37-43 | 3.1 | - | - | - |

| Great Hornbill |

2000-4000 | 152 | 95-130 | - | - | - | - |

| Black-headed Ibis |

1100-1400 | 130 | 65-76 | - | - | - | - |

| Wandering Albatross |

5,900-12,700 | 250-350 | 107-135 | 15.6 | 150 | - | - |

| Manx Shearwater |

350-575 | 76-89 | 30-38 | - | - | - | - |

| White stork | 2300-4500 | 155-215 | 110-125 | 7.2 | 63 | - | 4,800 |

| Swallow-tailed Kite |

310-600 | 112-136 | 50-68 | - | - | - | - |

| Bearded Vulture |

4500-7800 | 231-283 | 94-125 | 8.9 | 79 | - | 7,300 |

| Bar-headed Goose |

2000-3000 | 140-160 | 68-78 | 8.5 | 92 | 3.75 | 8,800 |

| Common Crane |

4600-5400 | 180-240 | 100-130 | - | - | - | 10,000 |

| Andean Condor |

10100-12500 | 283-330 | 100-130 | - | - | - | 6,500 |

| Rüppell’s Vulture |

6400-9000 | 226-260 | 85-103 | - | - | 3 | 11,300 |

| Snow Goose |

2050-4500 | 135-165 | 64-79 | - | - | - | 3,050 |

| Whooping Crane |

4500-8500 | 200-230 | 132 | 4.1 | 50 | - | 950 |

| Indian Paradise Flycatcher |

20-22 | 86-92 | 19-22 | - | - | - | - |

| White-browed Wagtail |

30-36 | - | 21 | - | - | - | - |

| Hoopoe | 46-89 | 44-48 | 25-32 | - | - | - | - |

| Black and White Warbler |

8-15 | 18-22 | 11-13 | - | - | - | - |

| Great Shearwater |

670-995 | 105-122 | 43-51 | - | - | - | - |

| Magpie Lark | 64-118 | - | 25-30 | - | - | - | - |

2.1.8. Concluding Summary of Structural and Physical Characteristics of Avian

2.2. Flight Modes and Features

2.2.1. Gliding Flight

Hang-Gliding

Dynamic Soaring in Avian Species

2.2.2. Bounding Flight

Intermittent Flight Strategies in Birds

2.2.3. Hovering Flight

Kinematics and Morphology

Wind-Hovering Flight

Flight Adaptations and Efficiency

Implications for Hovering and Windhovering Flight

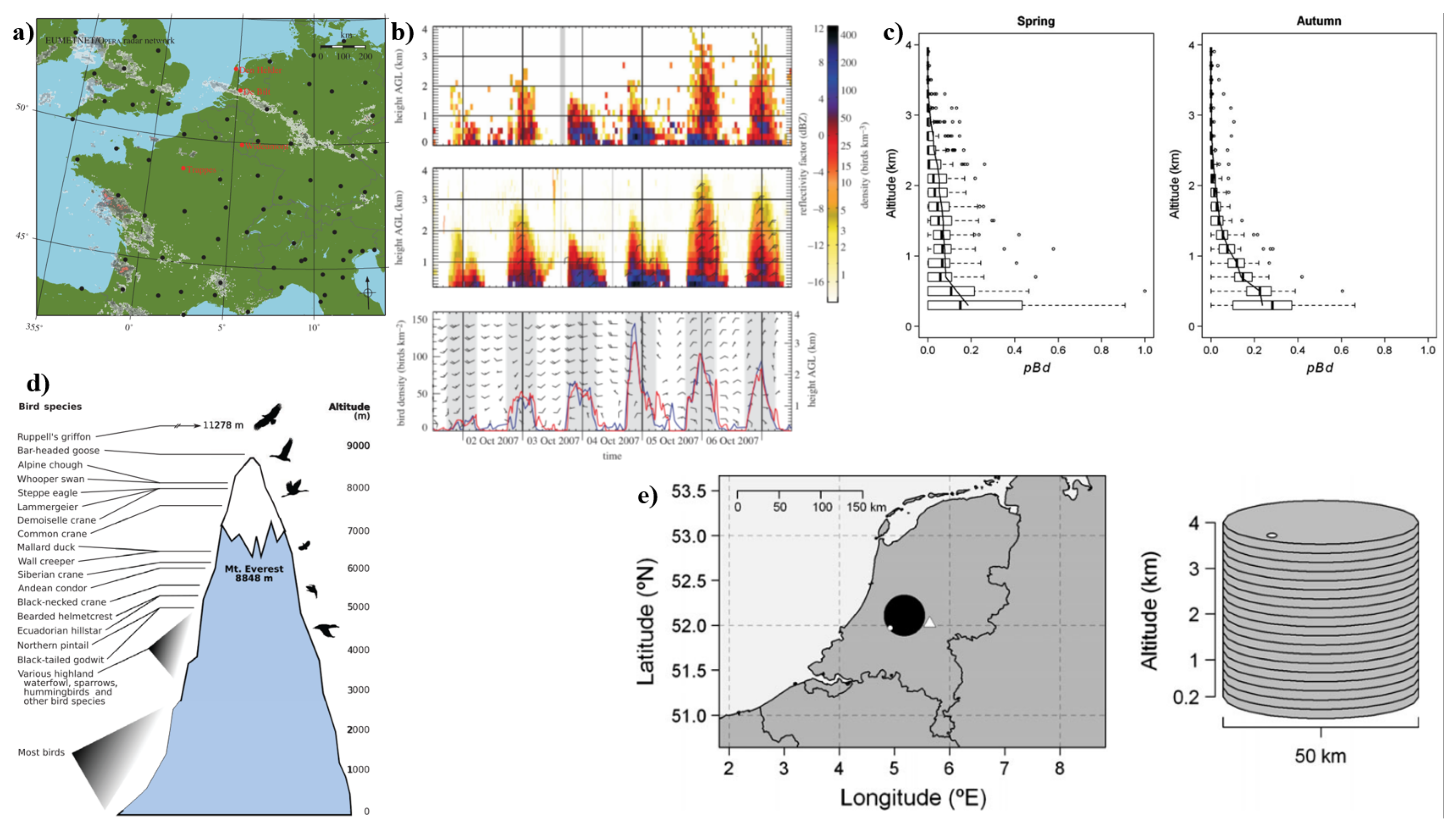

2.2.4. Formation Flight

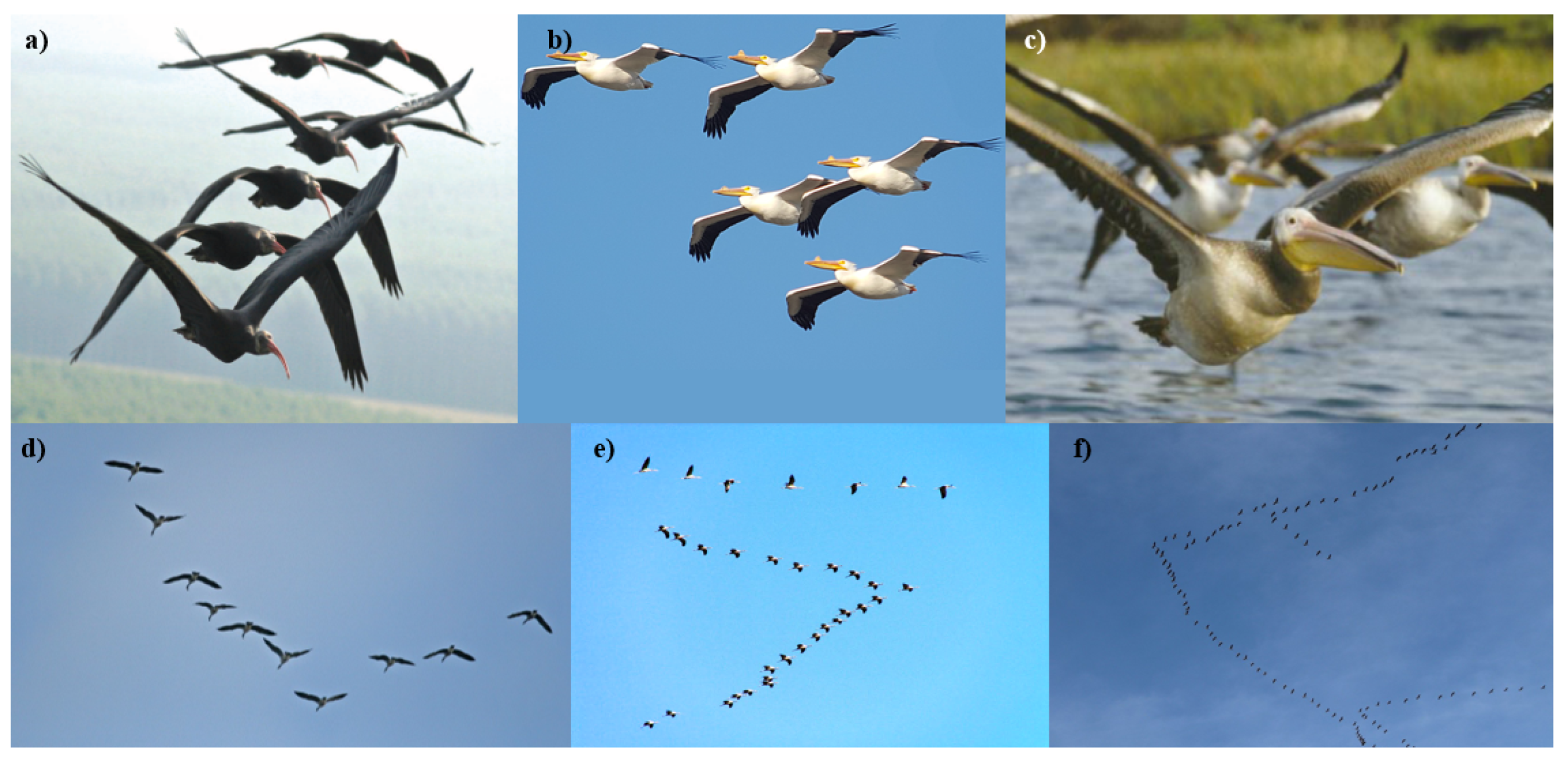

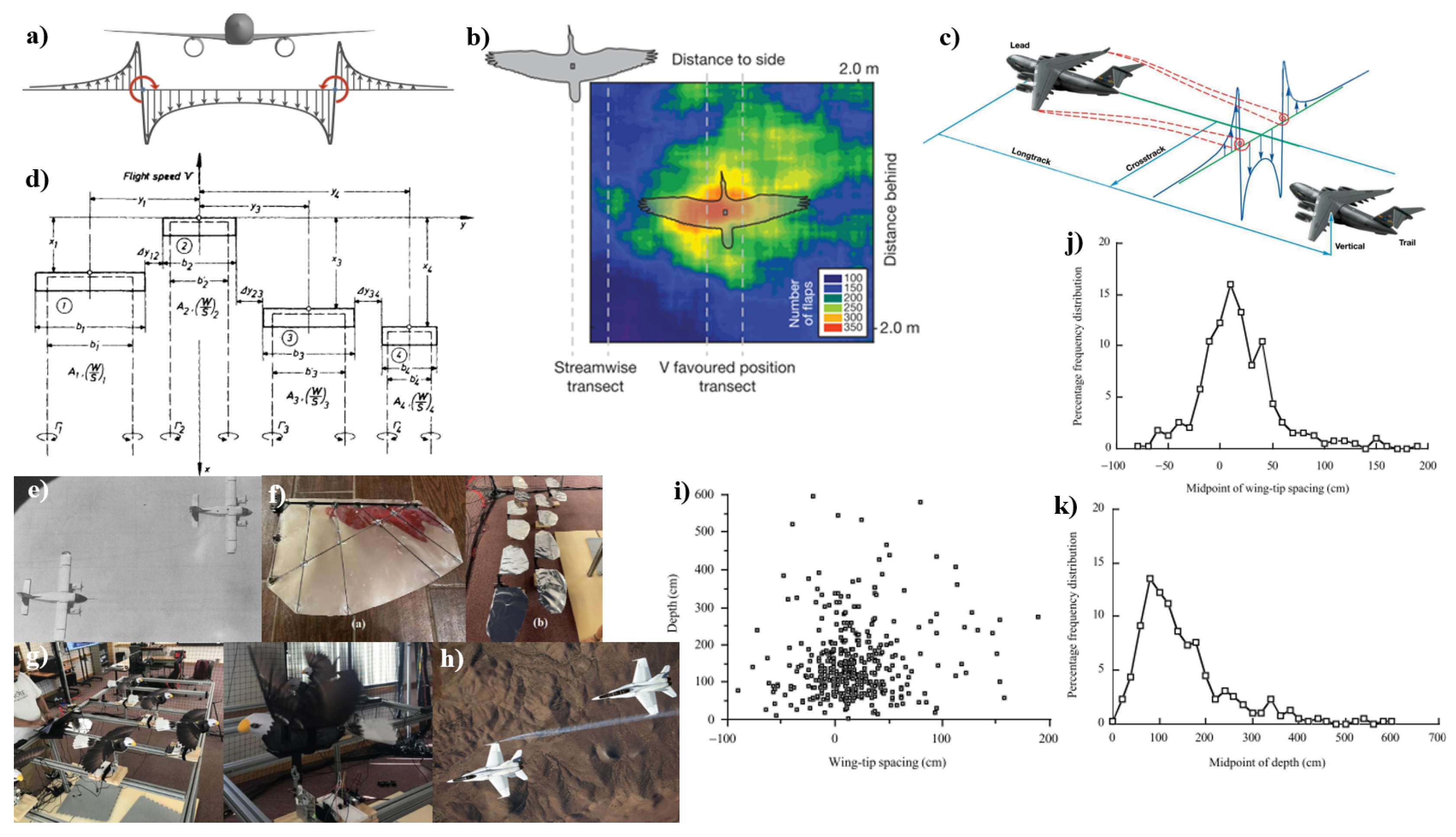

Avian Based Evidence and Measurements

Extended Formation Flight in Man-Made Aircraft

2.2.5. Leader Switching in Flock

Leader-Follower Dynamics in V-Shaped Flight Formations

Current State and Future Directions in Leader Switching Research

2.3. Environmental Interactions

2.3.1. Time of Migration of Migratory Birds

Energy-Minimizing Strategies in Herring Gulls and Lesser Black-Backed Gulls

Historical Adaptability and Future Predictions

2.3.2. Flight Routes of Migratory Birds

Wind-Dependent Flight Routes

Analysis on the Impact of Artificial Light on Migratory Patterns

Integrating Avian Migration Strategies into Broader Contexts

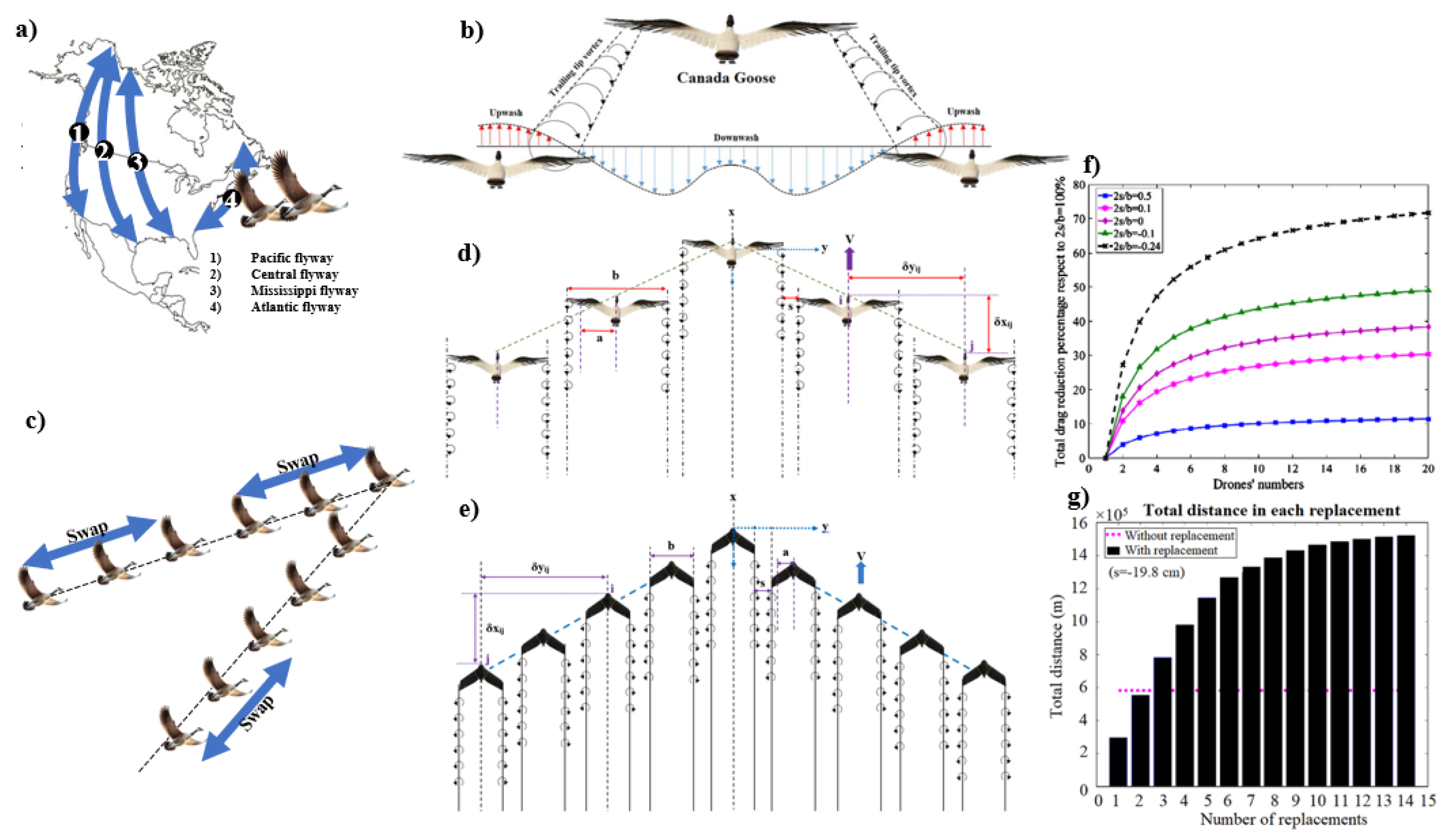

2.3.3. Changing Altitude

Influence of Weather and Wind Conditions

Adaptations for High-Altitude Flight

Implications for Avian Flight Strategy and Future Research

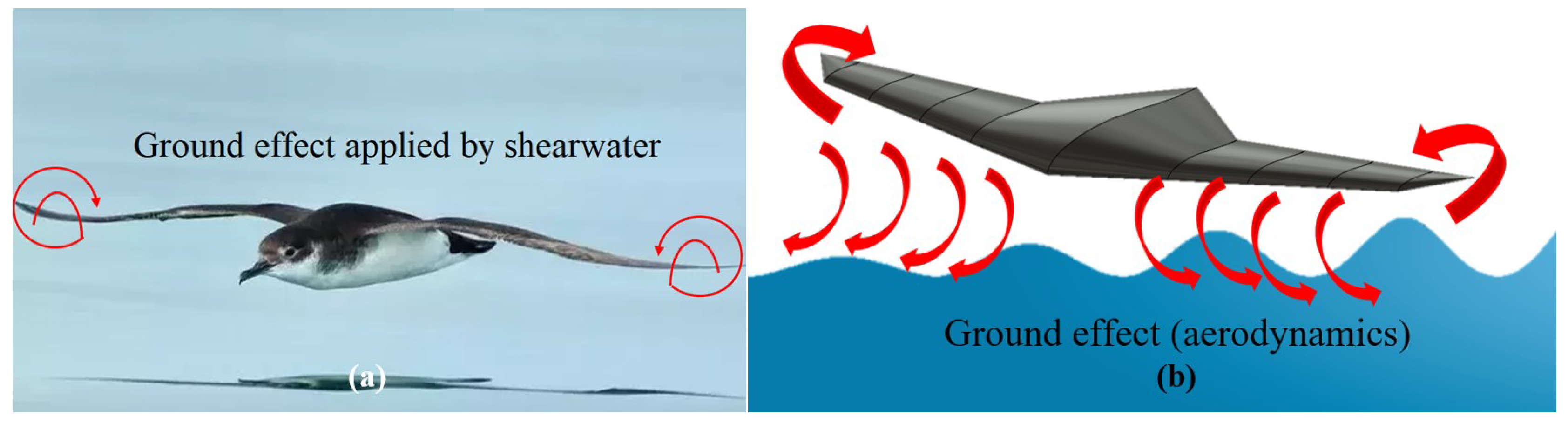

2.4. Ground Effects

3. Drag Reduction in Flying Insects

3.1. Structural and Physical Characteristics of Insects

3.1.1. Wing Shape

Morphological Influence on MAV Design

Genetic Influence on Wing Shape

Impact of Wing Planform on Aerodynamics

3.1.2. Wing Structure and Hairs

Hair Structures

Flexural Stiffness in Insect Wings

Inspiration from Insect Wing Scales

3.1.3. Wing Color

Energy-Harvesting Applications in Butterfly Wing Structures

3.1.4. Flight Modes

Hovering Flight

Gliding Flight

Summary of Flight Modes in Insects

4. Energy Harvesting

4.1. Soaring

4.1.1. Dynamic Soaring

Bio-Inspired Energy-Harvesting Mechanisms in Dynamic Soaring

Modeling and Application in UAV Design

4.1.2. Thermal Soaring

Historical Evolution of Thermal Soaring

Modeling Thermal Soaring

Interdisciplinary Insights and Future Directions

4.1.3. Slope Soaring

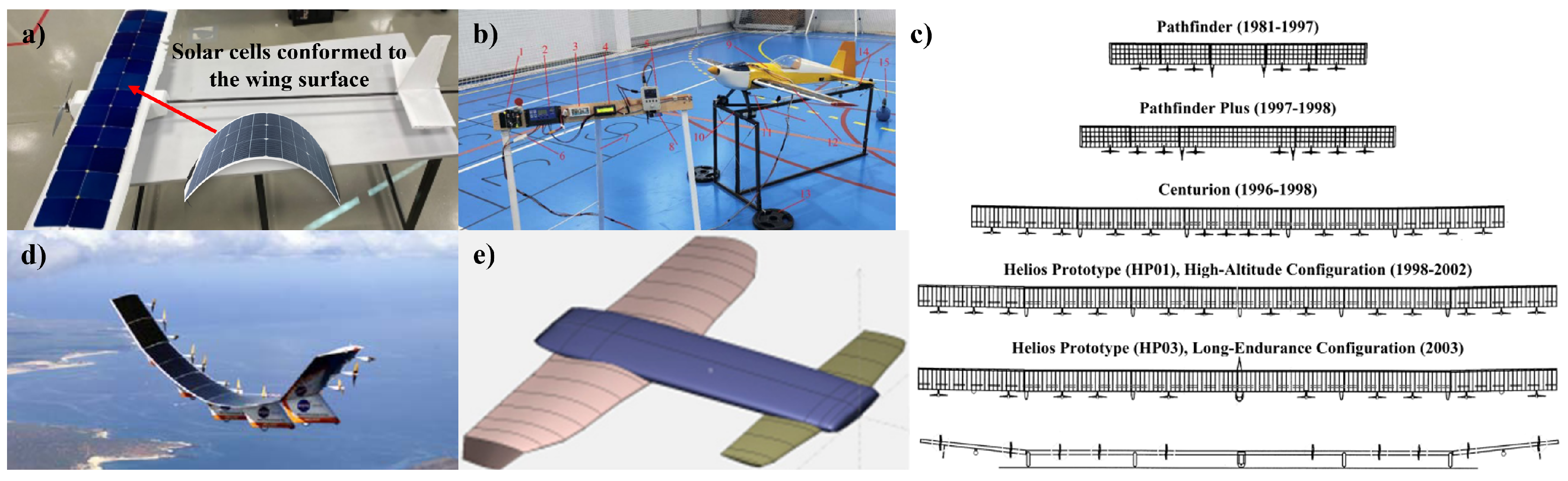

4.2. Solar Energy Harvesting

Drone Hubs for Solar Charging

Solar Powered UAVs

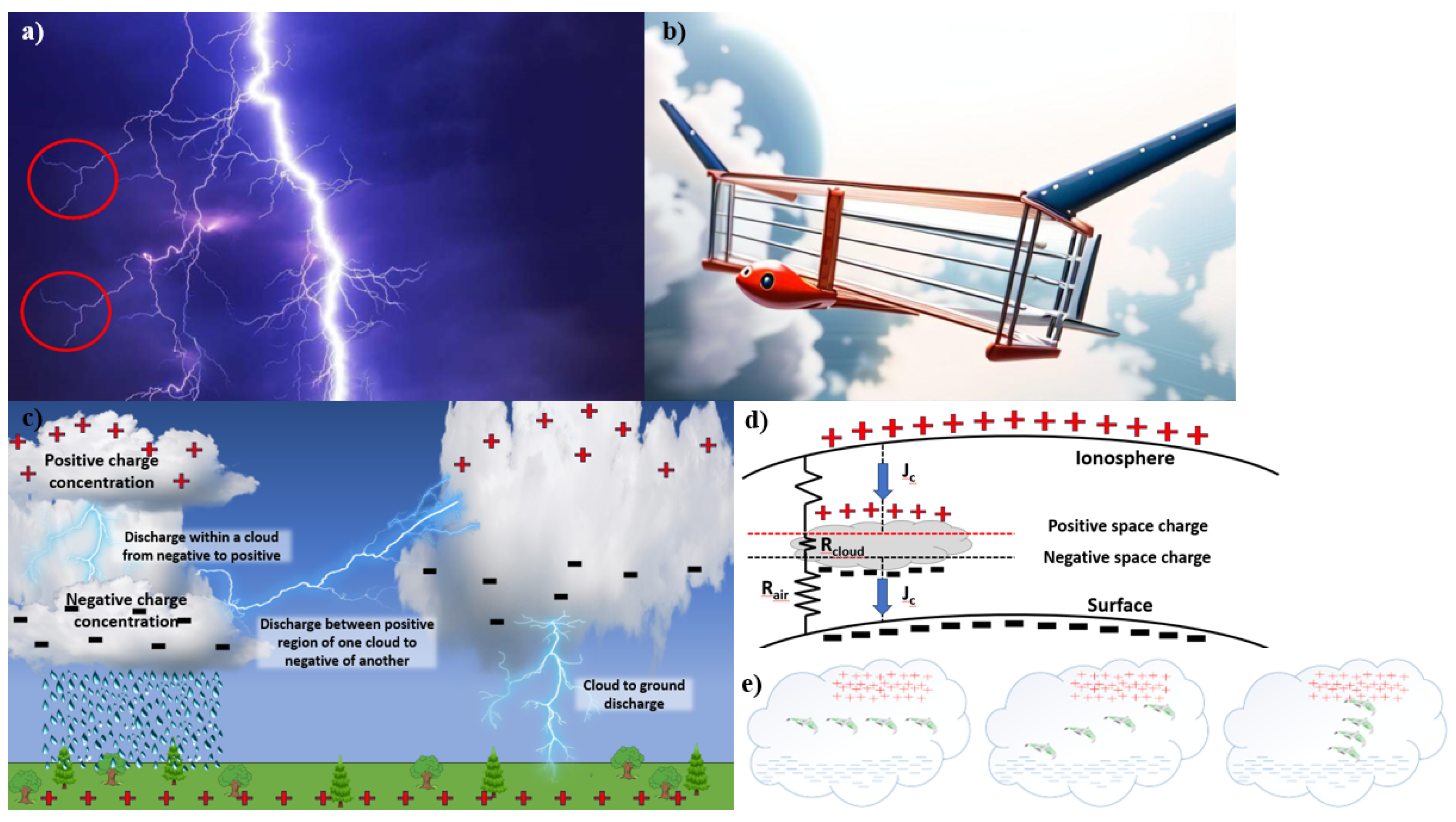

4.3. Ionized Winds and Energy Harvesting

Electro-Aerodynamic Propulsion

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

DURC Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Permissions

References

- Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, 2023.

- Chen, H.; Rao, F.; Shang, X.; Zhang, D.; Hagiwara, I. Biomimetic drag reduction study on herringbone riblets of bird feather. Journal of Bionic Engineering 2013, 10, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilovic, N.; Mohamed, A.; Marino, M.; Watkins, S.; Moschetta, J.M.; Benard, E. Avian-inspired energy-harvesting from atmospheric phenomena for small UAVs. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboelezz, A.; Herkenhoff, B.; Hassanalian, M. Effects of avian wings color patterns on their flight performance: experimental and computational studies. Journal of Bionic Engineering 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammill, M.; Sherman, M.; Raissi, A.; Hassanalian, M. Energy Harvesting Mechanisms for a Solar Photovoltaic Plant Monitoring Drone: Thermal Soaring and Bioinspiration. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2021 Forum. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2021, p. 1053. [CrossRef]

- Hassanalian, M.; Mohammadi, S.; Acosta, G.; Guido, N.; Bakhtiyarov, S. Surface temperature effects of solar panels of fixed-wing drones on drag reduction and energy consumption. Meccanica 2021, 56, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.M. Energy, environment and sustainable development. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2008, 12, 2265–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldheeb, M.A.; Asrar, W.; Sulaeman, E.; Omar, A.A. A review on aerodynamics of nonflapping bird wings. Journal of Aerospace Technology and Management 2016, 8, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.J. Riblets as a Viscous Drag Reduction Technique. AIAA Journal 1983, 21, 485–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.; Habegger, M.L.; Motta, P. Shark Skin Drag Reduction. In Encyclopedia of Nanotechnology; Bhushan, B., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2012; pp. 2394–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, B.; Bhushan, B. Shark-skin surfaces for fluid-drag reduction in turbulent flow: A review. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2010, 368, 4775–4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.; Lindemann, A. Optimization and application of riblets for turbulent drag reduction. In 22nd Aerospace Sciences Meeting; Aerospace Sciences Meetings, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 1984. [CrossRef]

- Domel, A.G.; Saadat, M.; Weaver, J.C.; Haj-Hariri, H.; Bertoldi, K.; Lauder, G.V. Shark skin-inspired designs that improve aerodynamic performance. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2018, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechert, D.W.; Bruse, M.; Hage, W.; Meyer, R. Fluid mechanics of biological surfaces and their technological application. Naturwissenschaften 2000, 87, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benschop, H.O.; Breugem, W.P. Drag reduction by herringbone riblet texture in direct numerical simulations of turbulent channel flow. Journal of Turbulence 2017, 18, 717–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.W.; Rao, F.G.; Zhang, D.Y.; Shang, X.P. Drag reduction study about bird feather herringbone riblets. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2014, 461, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rao, F.; Shang, X.; Zhang, D.; Hagiwara, I. Flow over bio-inspired 3D herringbone wall riblets. Experiments in Fluids 2014, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Chen, D.; Wang, J.; Yang, X. Bionic research on bird feather for drag reduction. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Dutta, S. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Bio-Inspired Riblet for Drag Reduction. Journal of Fluids Engineering 2022, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelezz, A.; Rubin, Z.; Hassanalian, M. Heated Boundary Layer and Aerodynamic Efficiency of Airfoils: Birds Coloration and Bioinspiration. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2021 Forum. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, jan 2021, AIAA SciTech Forum, p. 848. [CrossRef]

- Achache, Y.; Sapir, N.; Elimelech, Y. Hovering hummingbird wing aerodynamics during the annual cycle. Ii. implications of wing feather moult. Royal Society Open Science 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajanic, E.; Paolini, A.; Coster, C.; Floreano, D.; Johansson, C. Robotic Avian Wing Explains Aerodynamic Advantages of Wing Folding and Stroke Tilting in Flapping Flight. Advanced Intelligent Systems 2023, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldheeb, M.; Asrar, W.; Sulaeman, E.; Omar, A.A. Aerodynamics of porous airfoils and wings. Acta Mechanica 2018, 229, 3915–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R. The Whooping Crane; National Audobon Society, 1952.

- Alonso, J.C.; Bautista, L.M.; Alonso, J.A. Sexual size dimorphism in the Common Crane, a monogamous, plumage-monomorphic bird. Ornis Fennica 2019, 96, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, G.K.; Selig, M.S. Design of bird-like airfoils. AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, 2018 2018, pp. 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Anderton, J.; Rasmussen, P. Birds of South Asia The Ripley Guide, 2 ed.; Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions, 2005; p. 315.

- Azargoon, Y.; Djavareshkian, M.H. Unsteady characteristic study on the flapping wing with the corrugated trailing edge and slotted wingtip. Aerospace Science and Technology 2023, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.; Jeong, Y.E.; Moon, Y.J. Computation of flow past a flat plate with porous trailing edge using a penalization method. Computers and Fluids 2012, 66, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliga, B.; Szabo, I.; Altshuler, D.L. Range of motion in the avian wing is strongly associated with flight behavior and body mass. Science Advances 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Song, B.; Yang, W.; Xuan, J.; Xue, D. The progress of aerodynamic mechanisms based on avian leading-edge alula and future study recommendations. Aerospace 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, J.A.; Marugán-Lobón, J.; Cobb, S.N.; Rayfield, E.J. The shapes of bird beaks are highly controlled by nondietary factors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016, 113, 5352–5357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, M. Albatrosses and petrels across the world; Vol. 11, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Brown, C. Plumages And Measurements Of The Bearded Vulture In Southern Africa. Ostrich 1989, 60, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, D.M.; Moore, K.J. Drag reduction in nature. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 1991, 23, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboneras, C.; Jutglar, F.; Kirwan, G. Great Shearwater Ardenna gravis, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, A.C.; Walker, S.M.; Thomas, A.L.; Taylor, G.K. Aerodynamics of aerofoil sections measured on a free-flying bird. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part G: Journal of Aerospace Engineering 2010, 224, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carwardine, M.; Natural History Museum (London, E. Animal Records; Sterling, 2008.

- Catry, P.; Phillips, R.A.; Croxall, J.P. Sustained fast travel by a gray-headed albatross (Thalassarche chrysostoma) riding an antarctic storm. Auk 2004, 121, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czikeli, H. Whooping Crane, 1982.

- del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J. Ostrich to Ducks, 1992.

- del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J.; Christie, D.; de Juana, E. Manx Shearwater (Puffinus puffinus); Lynx Edicions, 2013.

- Drovetski, S.V. Influence Of The Trailing-Edge Notch On Flight Performance Of Galliforms. Auk 1996, 113, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J. Accidentals, Extinct Species. National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America (fifth ed.) 2006, p. 467.

- Dunning, J.B. CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses; CRC Press, 2007.

- Dutta, P.; Nagar, O.P.; Sahu, S.K.; Savale, R.R.; Gokul Raj, R. Aerodynamic analysis of bionic winglet- slotted wings. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 62, 6701–6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, H.; Fiedler, W.; Neuhäuser, M. Evaluation of aerodynamic parameters from infrared laser tracking of free-gliding white storks. Journal of Ornithology 2015, 156, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elphick, J. The Atlas of Bird Migrations: Tracing the Great Journeys of the World’s Birds; Struik Publishers, 2007; pp. 88–89.

- Elphick, J. The Atlas of Bird Migration: Tracing the Great Journeys of the World’s Birds, illustrate ed.; Firefly Books, 2011.

- Ferguson-Lees, J. Raptors of the World; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001.

- Gargiulo, C. Distribución y situación actual del cóndor andino (Vultur gryphus) en las sierras centrales de Argentina. PhD thesis, Universidad de Buenos Aires Facultad, 2012.

- Goumas, M. Dark wing pigmentation as a mechanism for improved flight efficiency in the Larinae. Communications Biology 2022, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsey, L.G.; Portugal, S.J.; Smith, J.A.; Murn, C.P.; Wilson, R.P. Recording raptor behavior on the wing via accelerometry. Journal of Field Ornithology 2009, 80, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.; Kushlan, J.; Kahl, M.P. Storks, Ibises, and Spoonbills of the World, 1 ed.; Academic Press, 1992.

- Hanna, Y.G.; Spedding, G.R. Aerodynamic performance improvements due to porosity in wings at moderate re. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation 2019 Forum, 2019, number June, pp. 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P. Seabirds , an Identification Guide. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 1984, 96, 333–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanalian, M.; Abdelmoula, H.; Ben Ayed, S.; Abdelk, A. Effects of birds’ wing color on their flight performance for biomimetic purposes. 25th AIAA/AHS Adaptive Structures Conference, 2017 2017, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Hassanalian, M.; Abdelmoula, H.; Ben Ayed, S.; Abdelkefi, A. Thermal impact of migrating birds’ wing color on their flight performance: Possibility of new generation of biologically inspired drones. Journal of Thermal Biology 2017, 66, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

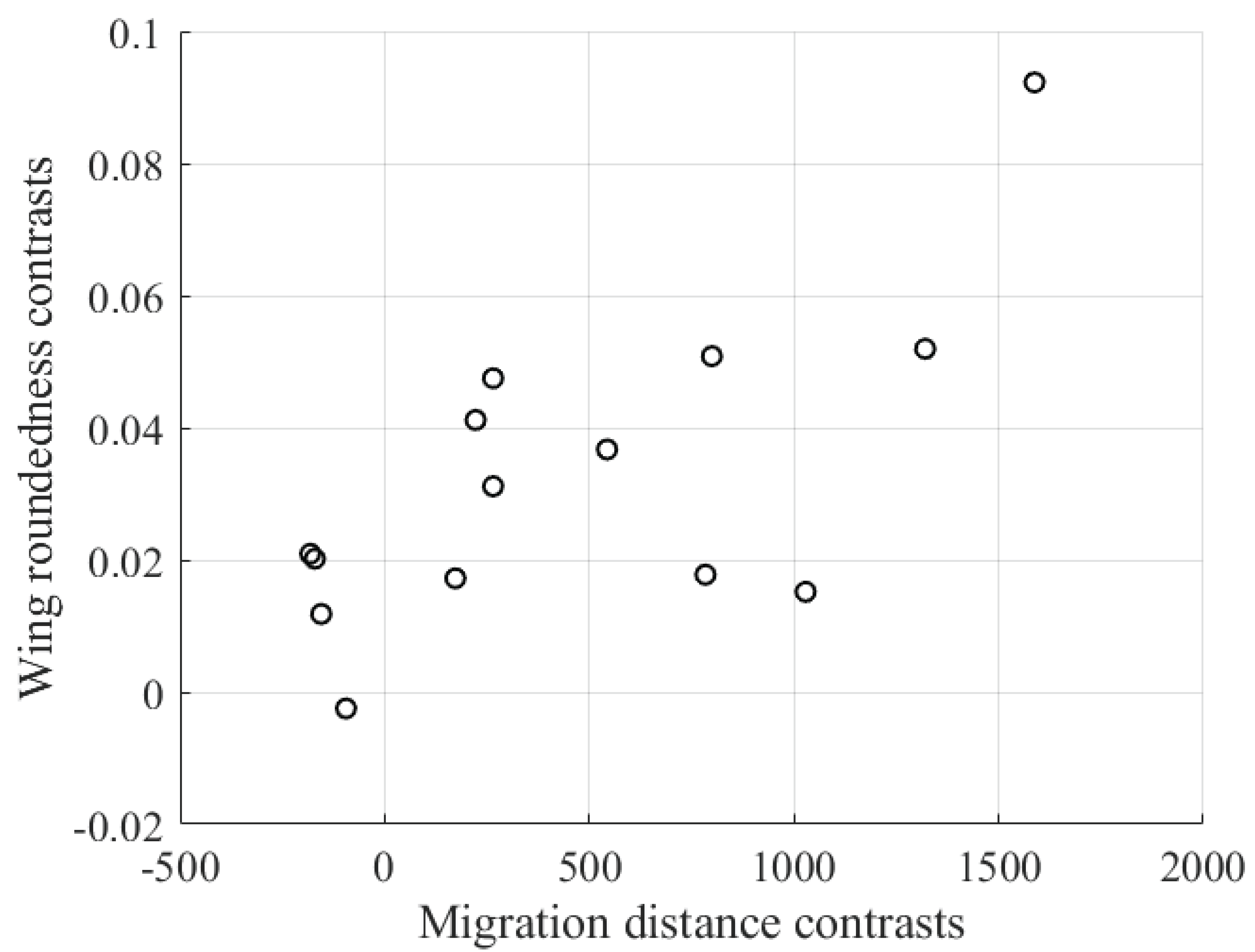

- Hassanalian, M.; Ayed, S.B.; Ali, M.; Houde, P.; Hocut, C.; Abdelkefi, A. Insights on the thermal impacts of wing colorization of migrating birds on their skin friction drag and the choice of their flight route. Journal of Thermal Biology 2018, 72, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedenström, A. Effects of wing damage and moult gaps on vertebrate flight performance. Journal of Experimental Biology 2023, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedenström, A.; Liechti, F. Field estimates of body drag coefficient on the basis of dives in passerine birds. Journal of Experimental Biology 2001, 204, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedenström, A.; Sunada, S. On the aerodynamics of moult gaps in birds. Journal of Experimental Biology 1999, 202, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Rahman, A.; Hossen, J.; Iqbal, P.; Shaari, N.; Sivaraj, G.K. Drag reduction in a wing model using a bird feather like winglet. Jordan Journal of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering 2011, 5, 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, J.; Kong, F.; Liu, H.H. Unsteady thermodynamic computational fluid dynamics simulations of aircraft wing anti-icing operation. Journal of Aircraft 2007, 44, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.H.; Turbek, S.P.; Bostwick, K.S.; Safran, R.J. Comparative analysis reveals migratory swallows (Hirundinidae) have less pointed wings than residents. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 2017, 120, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosilevskii, G. Aerodynamics of permeable membrane wings. European Journal of Mechanics, B/Fluids 2011, 30, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsgard, P.A. Cranes of the World; Indiana University Press, 1983.

- Jouventin, P.; Weimerskirch, H. Satellite tracking of Wandering albatrosses. Nature 1990, 343, 746–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Dong, H.; Wu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, Z. Experimental Study on the Effect of Porous Media on the Aerodynamic Performance of Airfoils. Aerospace 2023, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricher, J. Black-and-white Warbler Mniotilta varia, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kuyt, E. WHOOPING CRANE. Hinterland Who’s Who 1993.

- Kuyt, E. Aerial radio-tracking of whooping cranes migrating between Wood Buffalo National Park and Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, 1981-84; Vol. 74, Authority of the Minister of Environment Canadian Wildlife Service, 1992.

- Lang, X.; Song, B.; Yang, W.; Song, W. Aerodynamic performance of owl-like airfoil undergoing bio-inspired flapping kinematics. Chinese Journal of Aeronautics 2021, 34, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laybourne, R.C. Collision between a Vulture and an Aircraft at an Altitude of 37,000 Feet. The Wilson Bulletin 1974, 86, 461–462. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.Y.; Scott, G.R.; Milsom, W.K. Have wing morphology or flight kinematics evolved for extreme high altitude migration in the bar-headed goose? Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology - C Toxicology and Pharmacology 2008, 148, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.J.; Dimitriadis, G.; Nudds, R.L. The influence of flight style on the aerodynamic properties of avian wings as fixed lifting surfaces. PeerJ 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Shen, H.; Han, Q.; Ji, A.; Dai, Z.; Gorb, S.N. Effects of Morphological Integrity of Secondary Feather on Their Drag Reduction in Pigeons. Journal of Bionic Engineering 2022, 19, 1422–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likoff, L. Adelie Penguin to Budgerigar; Number v. 6 in The Encyclopedia of Birds, Facts on File, 2007.

- Lincoln, F. Migration of Birds, illustrate ed.; U.S. Government Printing Office, 1999.

- Liu, D.; Song, B.; Yang, W.; Yang, X.; Xue, D.; Lang, X. A Brief Review on Aerodynamic Performance of Wingtip Slots and Research Prospect. Journal of Bionic Engineering 2021, 18, 1255–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Kuykendoll, K.; Rhew, R.; Jones, S. Avian wing geometry and kinematics. AIAA Journal 2006, 44, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; He, G. Engineering perspective on bird flight: Scaling, geometry, kinematics and aerodynamics. Progress in Aerospace Sciences, 2023; 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovvorn, J.R.; Liggins, G.A.; Borstad, M.H.; Calisal, S.M.; Mikkelsen, J. Hydrodynamic drag of diving birds: Effects of body size, body shape and feathers at steady speeds. Journal of Experimental Biology 2001, 204, 1547–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, A.I.; Bradley, C.W.; Garcia, E. Aerodynamic Properties Of Avian Flight As A Function Of Wing Shape. In Proceedings of the International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition (IMECE), Orlando, Florida, 2005; pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Maybury, W.J. The aerodynamics of bird bodies. PhD thesis, University of Bristol, 2000.

- Mazellier, N.; Feuvrier, A.; Kourta, A. Biomimetic bluff body drag reduction by self-adaptive porous flaps. Comptes Rendus - Mecanique 2012, 340, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowbray, T.; Fred, C.; Barbara, G. Snow Goose (Chen caerulescens), 2000. [CrossRef]

- Müller, W.; Patone, G. Air transmissivity of feathers. Journal of Experimental Biology 1998, 201, 2591–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murayama, Y.; Nakata, T.; Liu, H. Flexible Flaps Inspired by Avian Feathers Can Enhance Aerodynamic Robustness in low Reynolds Number Airfoils. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2021, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayan, G.; John, B. Effect of winglets induced tip vortex structure on the performance of subsonic wings. Aerospace Science and Technology 2016, 58, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navalón, G.; Bright, J.A.; Marugán-Lobón, J.; Rayfield, E.J. The evolutionary relationship among beak shape, mechanical advantage, and feeding ecology in modern birds*. Evolution 2019, 73, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, A.; Rahuma, R.; Emhemmed, A. Numerical investigation on aerodynamic performance of bird’s airfoils. Journal of Aerospace Technology and Management 2020, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osváth, G.; Vincze, O.; David, D.C.; Nagy, L.J.; Lendvai, Á.Z.; Nudds, R.L.; Pap, P.L. Morphological characterization of flight feather shafts in four bird species with different flight styles. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 2020, 131, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D. The rufous and white forms of an Asiatic paradise flycatcher, Terpsiphone paradisi. Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 1959.

- Öztürk, Ş.; Örs, İ. An overview for effects on aerodynamic performance of using winglets and wingtip devices on aircraft. International Journal of Aeronautics and Astronautics 2020, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Pap, P.L.; Osváth, G.; Sándor, K.; Vincze, O.; Bărbos, L.; Marton, A.; Nudds, R.L.; Vágási, C.I. Interspecific variation in the structural properties of flight feathers in birds indicates adaptation to flight requirements and habitat. Functional Ecology 2015, 29, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellerito, V.; Hassanalian, M.; Sedaghat, A.; Sabri, F.; Borvayeh, L.; Sadeghi, S. Performance analysis of a bioinspired albatross airfoil with heated top wing surface: experimental study. AIAA Propulsion and Energy Forum and Exposition, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pennycuick, J. The flight of petrels and albatrosses (procellariiformes), observed in South Georgia and its vicinity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences 1982, 300, 75–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Weng, Z.; Li, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, H. On the controlled evolution for wingtip vortices of a flapping wing model at bird scale. Aerospace Science and Technology 2021, 110, 106460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rader, J.; Hedrick, T.L. Morphological evolution of bird wings follows a mechanical sensitivity gradient determined by the aerodynamics of flapping flight Mechanical sensitivity drives wing shape evolution. bioRxiv 2022, pp. 1–32.

- Rajesh Senthil Kumar, T.; Shriram, S.V.; Chowdary, G.P.; Sagar, J.; Ramakrishnananda, B. Aerodynamic characteristics of avian airfoils. AIP Conference Proceedings 2019, 2134, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.L. How do albatrosses fly around the world without flapping their wings? Progress in Oceanography 2011, 88, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A. The Design and Experimental Optimization of a Wingtip Vortex Turbine for General Aviation Use. PhD thesis, Embry Riddle Aeronautical University, 1997.

- Robertson, R. Albatrosses (Diomedeidae), 2 ed.; Cengage Gale, 2002.

- Rogalla, S.; D’Alba, L.; Verdoodt, A.; Shawkey, M.D. Hot wings: Thermal impacts of wing coloration on surface temperature during bird flight. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogalla, S.; Nicolaï, M.P.; Porchetta, S.; Glabeke, G.; Battistella, C.; D’Alba, L.; Gianneschi, N.C.; Van Beeck, J.; Shawkey, M.D. The evolution of darker wings in seabirds in relation to temperature-dependent flight efficiency. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, G.; Traugott, J.; Nesterova, A.P.; Dell’Omo, G.; Kümmeth, F.; Heidrich, W.; Vyssotski, A.L.; Bonadonna, F. Flying at No Mechanical Energy Cost: Disclosing the Secret of Wandering Albatrosses. PLoS ONE 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savile, D.B.O. Adaptive Evolution in the Avian Wing. Society for the Study of Evolution 1957, 11, 212–224. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, I.; Hockey, P. SASOL Larger Illustrated Guide to Birds of Southern Africa; New Holland Publishers, 2005.

- Stetson, K.F.; Kimmel, R.L. Surface temperature effects on boundary-layer transition. AIAA Journal 1992, 30, 2782–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, T.; Fanshawe, J. Birds of East Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi Second Edition, 2 ed.; Princeton University Press, 2020.

- Swift, K.M. An Experimental Analysis of the Laminar Separation Bubble At Low Reynolds Numbers. PhD thesis, The University of Tennessee, 2009.

- Tangermann, E.; Ercolani, G.; Klein, M. Aerodynamic Behavior of a Biomimetic Wing in Soaring Flight – A Numerical Study. Flow, Turbulence and Combustion 2022, 109, 1155–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traub, L.W.; Coffman, C. Efficient low-Reynolds-number airfoils. Journal of Aircraft 2019, 56, 1987–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, V.A. Drag Reduction by Wing Tip Slots in a Gliding Harris’ Hawk, Parabuteo Unicinctus. Journal of Experimental Biology 1995, 198, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, V.A. Gliding Birds: Reduction of Induced Drag by Wing Tip Slots Between the Primary Feathers. Journal of Experimental Biology 1993, 180, 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oorschot, B.K. Aerodynamics and Ecomorphology of Flexible Feathers and Morphing Bird Wings. PhD thesis, University of Montana, 2017.

- Van Wassenbergh, S.; Baeckens, S. Digest: Evolution of shape and leverage of bird beaks reflects feeding ecology, but not as strongly as expected. Evolution 2019, 73, 621–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, S.; Bishop, C.M.; Woakes, A.J.; Butler, P.J. Heart rate and the rate of oxygen consumption of flying and walking barnacle geese (Branta leucopsis) and bar-headed geese (Anser indicus). Journal of Experimental Biology 2002, 205, 3347–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warham, J., Ed. The Behaviour, Population Biology and Physiology of the Petrels; Vol. 21, Harcourt Brace & Company, 1998; p. 114. [CrossRef]

- Warham, J. Wing loadings, wing shapes, and flight capabilities of procellariiformes. New Zealand Journal of Zoology 1977, 4, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, L. The High Life. Audubon 2000, 102, 104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.L.; Spedding, G.R. Passive separation control by acoustic resonance. Experiments in Fluids 2013, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, A.; Tekeci, A.; Ozyetkin, M.; Demircali, A.; Unsal, K.; Uvet, H. The effect of pore structure in flapping wings on flight performance. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.04390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yin, Y. Study on riblet drag reduction considering the effect of sweep angle. Energies 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, D.R.R.; Bhattacharya, S. Ground Effect-Enhanced Unsteady Aerodynamic of Rapid-Pitch-Up Motions for Diverse Flying Objectives in Birds. In AIAA SCITECH 2024 Forum; AIAA SciTech Forum, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ákos, Z.; Nagy, M.; Leven, S.; Vicsek, T. Thermal soaring flight of birds and unmanned aerial vehicles. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baddoo, P.J.; Kurt, M.; Ayton, L.J.; Moored, K.W. Exact solutions for ground effect. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2020, 891, 2, [1912.02713]. [CrossRef]

- Blake, R.W. Mechanics of gliding in birds with special reference to the influence of the ground effect. Journal of Biomechanics 1983, 16, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohrer, G.; Brandes, D.; Mandel, J.T.; Bildstein, K.L.; Miller, T.A.; Lanzone, M.; Katzner, T.; Maisonneuve, C.; Tremblay, J.A. Estimating updraft velocity components over large spatial scales: Contrasting migration strategies of golden eagles and turkey vultures. Ecology Letters 2012, 15, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerr, A.E.; Miller, T.A.; Lanzone, M.; Brandes, D.; Cooper, J.; O’Malley, K.; Maisonneuve, C.; Tremblay, J.A.; Katzner, T. Flight response of slope-soaring birds to seasonal variation in thermal generation. Functional Ecology 2015, 29, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duriez, O.; Kato, A.; Tromp, C.; Dell’Omo, G.; Vyssotski, A.L.; Sarrazin, F.; Ropert-Coudert, Y. How cheap is soaring flight in raptors? A preliminary investigation in freely-flying vultures. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, J.; Carlsson, J.; Kelly, T.; Davenport, J. Avoidance of headwinds or exploitation of ground effect-why do birds fly low. Journal of Field Ornithology 2012, 83, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, H. An Interface Management Approach for Civil Aircraft Design; Vol. 680 LNEE, 2021; pp. 435–446. [CrossRef]

- Hainsworth, F.R. Induced Drag Savings From Ground Effect and Formation Flight in Brown Pelicans. Journal of Experimental Biology 1988, 135, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, R.; Nathan, R. The characteristic time-scale of perceived information for decision-making: Departure from thermal columns in soaring birds. Functional Ecology 2018, 32, 2065–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, L.C.; Jakobsen, L.; Hedenström, A. Flight in Ground Effect Dramatically Reduces Aerodynamic Costs in Bats. Current Biology 2018, 28, 3502–3507.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.H.; Chun, H.H.; Kim, H.J. Experimental investigation of wing-in-ground effect with a NACA6409 section. Journal of Marine Science and Technology 2008, 13, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempton, J.A.; Wynn, J.; Bond, S.; Evry, J.; Fayet, A.L.; Gillies, N.; Guilford, T.; Kavelaars, M.; Juarez-Martinez, I.; Padget, O.; et al. Optimization of dynamic soaring in a flap-gliding seabird affects its large-scale distribution at sea. Science Advances 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaghani, J.; Nekoui, M.; Nasiri, R.; Ahmadabadi, M.N. Analytical Model of Thermal Soaring: Towards Energy Efficient Path Planning for Flying Robots. IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems 2018, pp. 7589–7594. [CrossRef]

- Khosravifard, S.; Venus, V.; Skidmore, A.K.; Bouten, W.; Muñoz, A.R.; Toxopeus, A.G. Identification of Griffon Vulture’s Flight Types Using High-Resolution Tracking Data. International Journal of Environmental Research 2018, 12, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.M.; Gopalarathnam, A. Ideal aerodynamics of ground-effect and formation flight. AIAA Paper 2004, 42, 11500–11511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.N.; Hou, Z.X.; Guo, Z.; Yang, X.X.; Gao, X.Z. Bio-inspired energy-harvesting mechanisms and patterns of dynamic soaring. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallon, J.M.; Bildstein, K.L.; Katzner, T.E. In-flight turbulence benefits soaring birds. Auk 2016, 133, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, J.T. Using Movement Ecology To Understand Flight Behavior In Soaring Birds 2009.

- Miller, T.A.; Brooks, R.P.; Lanzone, M.J.; Brandes, D.; Cooper, J.; Tremblay, J.A.; Wilhelm, J.; Duerr, A.; Katzner, T.E. Limitations and mechanisms influencing the migratory performance of soaring birds. Ibis 2016, 158, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Taylor, G.K.; Watkins, S.; Windsor, S.P. Opportunistic soaring by birds suggests new opportunities for atmospheric energy harvesting by flying robots. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg, U.M.L.; Brooke, A.P.; Trewhella, W.J. Soaring And Non-Soaring Bats Of The Family Pteropodidae 2000. 664, 651–664.

- Pekarsky, S.; Shohami, D.; Horvitz, N.; Bowie, R.C.K.; Kamath, P.L.; Markin, Y.; Getz, W.M.; Nathan, R. Cranes soar on thermal updrafts behind cold fronts as they migrate across the sea. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Royal Society B, 2024, number 291. [CrossRef]

- Penn, M.; Yi, G.; Watkins, S.; Martinez Groves-Raines, M.; Windsor, S.P.; Mohamed, A. A method for continuous study of soaring and windhovering birds. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycuick, C.J. Field Observations of Thermals and Thermal Streets , and the Theory of Cross-Country Soaring Flight. Journal of Avian Biology 1998, 29, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycuick, C.J. Soaring Behaviour and Performance of Some East African Birds, Observed From a Motor-Glider. Ibis 1972, 114, 178–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycuick, C.J. The Soaring Flight of Vultures. Scientific American 1973, 229, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S.; Eisa, S.A. A novel hypothesis for how albatrosses optimize their flight physics in real-time: an extremum seeking model and control for dynamic soaring. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayner, J.M. On the aerodynamics of animal flight in ground effect. Royal Society, 1991; 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, J.M.; Thomas, A.L. On the vortex wake of an animal flying in a confined volume. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 1991, 334, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.L. Leonardo da Vinci’s Discovery of the Dynamic Soaring by Birds in Wind Shear. Royal Society, 2018; 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.L.; Wakefield, E.D.; Phillips, R.A. Flight speed and performance of the wandering albatross with respect to wind. Movement Ecology 2018, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, G. Minimum shear wind strength required for dynamic soaring of albatrosses. Ibis 2005, 147, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, G. In-flight measurement of upwind dynamic soaring in albatrosses. Progress in Oceanography 2016, 142, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakornsin, R.; Atipan, S. Experimental Investigation of Seabird-Like Wings in Ground Effect. Journal of Aeronautics, Astronautics and Aviation 2019, 51, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.D.; Hanssen, F.; Muñoz, A.R.; Onrubia, A.; Wikelski, M.; May, R.; Silva, J.P. Match between soaring modes of black kites and the fine-scale distribution of updrafts. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, F.J.; Chiappe, L.M. Aerodynamic modelling of a Cretaceous bird reveals thermal soaring capabilities during early avian evolution. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamoun-Baranes, J.; Leshem, Y.; Yom-Tov, Y.; Liechti, O. Differential Use of Thermal Convection by Soaring Birds over Central Israel. The Condor 2003, 105, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. Fly low: The ground effect of a barn owl (Tyto alba) in gliding flight. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 2021, 235, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, I.A.; Lucas, A.J. Wave-slope soaring of the brown pelican. Movement Ecology 2021, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.Y.; Tang, J.H.; Wang, C.H.; Yang, J.T. A numerical investigation on the ground effect of a flapping-flying bird. Physics of Fluids 2013, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallman, J.; Yu, D.; Pantoja, M. Thermal detection for free flight. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2021, 1828, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.H.; Su, J.Y.; Wang, C.H.; Yang, J.T. Numerical investigation of the ground effect for a small bird. Journal of Mechanics 2013, 29, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorup, K.; Alerstam, T.; Hake, M.; Kjellén, N. Traveling or stopping of migrating birds in relation to wind: An illustration for the osprey. Behavioral Ecology 2006, 17, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Erp, J.; Sage, E.; Bouten, W.; van Loon, E.; Camphuysen, K.C.; Shamoun-Baranes, J. Thermal soaring over the North Sea and implications for wind farm interactions. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2023, 723, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; An, W.; Song, B. The Mechanisms of Albatrosses’ Energy-Extraction During the Dynamic Soaring; Vol. 680 LNEE, Springer Singapore, 2021; pp. 507–516. [CrossRef]

- Warham, J. The behaviour, population biology and physiology of the petrels; Academic Press, 1996. [CrossRef]

- Weinzierl, R.; Bohrer, G.; Kranstauber, B.; Fiedler, W.; Wikelski, M.; Flack, A. Wind estimation based on thermal soaring of birds. Ecology and Evolution 2016, 6, 8706–8718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.J.; Shepard, E.L.; Holton, M.D.; Alarcón, P.A.; Wilson, R.P.; Lambertucci, S.A. Physical limits of flight performance in the heaviest soaring bird. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2020, 117, 17884–17890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, D.J.; Peraire, J.; Breuer, K.S. A computational investigation of bio-inspired formation flight and ground effect. Collection of Technical Papers - AIAA Applied Aerodynamics Conference 2007, 2, 1140–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, P.C.; Timko, P.L. The Significance of Ground Effect to the Aerodynamic Cost of Flight and Energetics of the Black Skimmer ( Rhyncops Nigra ). Journal of Experimental Biology 1977, 70, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanalian, M.; Abdelkefi, A. Classifications, applications, and design challenges of drones: A review. Progress in Aerospace Sciences 2017, 91, 99–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, T.J. Fixed and Flapping Wing Aerodynamics for Micro Air Vehicle Applications; Vol. 195, Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, 2001.

- Bannasch, R., From Soaring and Flapping Bird Flight to Innovative Wing and Propeller Constructions. In Fixed and Flapping Wing Aerodynamics for Micro Air Vehicle Applications; Mueller, T.J., Ed.; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, 2001; Vol. 195, Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics, pp. 449–477.

- Kato, N.; Kamimura, S. Biomechanisms of Swimming and Flying; Springer: Tokyo, New York, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shyy, W.; Aono, H.; Kang, C.k.; Liu, H. An introduction to flapping wing aerodynamics, 2013. https://doi.org/LK - https://nmt.on.worldcat.org/oclc/847664062.

- Harvey, C.; de Croon, G.; Taylor, G.K.; Bomphrey, R.J. Lessons from natural flight for aviation: then, now and tomorrow. Journal of Experimental Biology 2023, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyy, W.; Lian, Y.; Tang, J.; Viieru, D.; Liu, H. Aerodynamics ofLow Reynolds Number Flyers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T. Comparative scaling of flapping- and fixed-wing flyers. AIAA Journal 2006, 44, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycuick, C.J. Wingbeat frequency of birds in steady cruising flight: New data and improved predictions. Journal of Experimental Biology 1996, 199, 1613–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandtl, L. Induced Drag of Multiplanes. Technical report, NASA, 1924.

- Prandtl, L. The Mechanics of Viscous Fluids. 1935.

- Jones, R.T. Wing Theory; Princeton University Press, 1990.

- Knoller, R.; Verein, O.F. Die Gesetze des Luftwiderstandes; Verlag des Österreichischer Flugtechnischen Vereines: Wien SE - 14 pages : illustrations ; 24 cm, 1909. https://doi.org/LK-https://worldcat.org/title/841616578.

- Betz, A. Ein Beitrag zur Erklärung des Segelfluges. Zeitschrift für Flugtechnik und Motorluftschiffahrt 1912, 3, 269–272. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum, W. Flugmechanik der Flügelschläge. Zeitschrift für Flugtechnik und Motorluftschiffahrt 1912, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Theodorsen, T.; Mutchler, W.H.; for Aeronautics, U.S.N.A.C. General theory of aerodynamic instability and the mechanism of flutter; National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics: Washington, D.C. SE - 23 pages : illustrations ; 26 cm, 1935. https://doi.org/LK - https://worldcat.org/title/46448356.

- Jones, K.D.; Dohring, C.M.; Platzer, M.F. Experimental and Computational Investigation of the Knoller-Betz Effect. AIAA Journal 1998, 36, 1240–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.J.; Feng, A.L.; Lee, H.C.; Esakki, B.; He, W. The three-dimensional flow simulation of a flapping wing. Journal of Marine Science and Technology (Taiwan) 2018, 26, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandell, K.E.; Howe, R.O.; Falkingham, P.L. Repeated evolution of drag reduction at the air–water interface in diving kingfishers. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.R.; Sobieczky, H.; Dulikravic, G.S.; Abdoli, A. Multi-element winglets: Multi-objective optimization of aerodynamic shapes. Journal of Aircraft 2016, 53, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.Z.; Sun, M. Power requirements for the hovering flight of insects with different sizes. Journal of Insect Physiology 2021, 134, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aono, H.; Liang, F.; Liu, H. Near- and far-field aerodynamics in insect hovering flight: An integrated computational study. Journal of Experimental Biology 2008, 211, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, B.; Roll, J.; Liu, Y.; Troolin, D.R.; Deng, X. Three-dimensional vortex wake structure of flapping wings in hovering flight. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2014, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, P.R.; Hossain, A.; Edi, P.; Jaafar, A.A.; Younis, T.S.; Saleem, M. Drag Reduction in Aircraft Model Using Elliptical Winglet. The Institution of Engineer Malaysia 2005, 66, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kernstine, K.H.; Moore, C.J.; Cutler, A.; Mittal, R. Initial Characterization of Self-Activated Movable Flaps, “Pop-Up Feathers”. In Proceedings of the 46th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, Nevada; 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosti, M.E.; Kamps, L.; Bruecker, C.; Omidyeganeh, M.; Pinelli, A. The PELskin project-part V: towards the control of the flow around aerofoils at high angle of attack using a self-activated deployable flap. Meccanica 2017, 52, 1811–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, J.U. Lift enhancement at low Reynolds numbers using pop-up feathers. In Proceedings of the 39th AIAA Fluid Dynamics Conference, 2009, number June. [CrossRef]

- Ponitz, B.; Schmitz, A.; Fischer, D.; Bleckmann, H.; Brücker, C. Diving-flight aerodynamics of a peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus). PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz, M.; Knacke, T.; Thiele, F.; Meyer, R.; Hage, W.; Bechert, D.W. Separation Control by Self-Activated Movable Flaps. In Proceedings of the 42nd AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting & Exhibit, Reno, NV, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.E.; Maestro, D.; Bottaro, A. Biomimetic spiroid winglets for lift and drag control. Comptes Rendus - Mecanique 2012, 340, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KleinHeerenbrink, M.; Christoffer Johansson, L.; Hedenström, A. Multi-cored vortices support function of slotted wing tips of birds in gliding and flapping flight. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, Z.; Cheng, G.; Chen, G. Experimental investigation on tip-vortex flow characteristics of novel bionic multi-tip winglet configurations. Physics of Fluids 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Roche, U.; Palffy, S. WING-GRID, a Novel Device for Reduction of Induced Drag on Wings. In Proceedings of the International Civil Aviation Convention, Switzerland; 1996; pp. 2303–2309. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, J.; Liu, H. Effects of owl-inspired leading-edge serrations on tandem wing aeroacoustics. AIP Advances 2022, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.; Mandadzhiev, B.; Wissa, A. Bioinspired wingtip devices: A pathway to improve aerodynamic performance during low Reynolds number flight. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brothers, E. Airbus unveils hybrid-electric regional airliner concept, 2019.

- Hubbard, L. Peacock at the Cincinnati Zoo, 2016.

- A leading-edge alula-inspired device (LEAD) for stall mitigation and lift enhancement for low Reynolds number finite wings. In Proceedings of the ASME Conference on Smart Materials, Adaptive Structures and Intelligent Systems, San Antonio, TX, 2018; Vol. 2, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, L.P.; Lynch, M.K. Alula-inspired Leading Edge Device for Low Reynolds Number Flight. In Proceedings of the ASME Conference on Smart Materials, Adaptive Structures and Intelligent Systems, Stowe, VT, 2017; pp. 1–12.

- Mandadzhiev, B.A.; Lynch, M.K.; Chamorro, L.P.; Wissa, A.A. An experimental study of an airfoil with a bio-inspired leading edge device at high angles of attack. Smart Materials and Structures 2017, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyy, W.; Liu, H. Flapping wings and aerodynamic lift: The role of leading-edge vortices. AIAA Journal 2007, 45, 2817–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, T.; Mohseni, K. Investigation of a sliding alula for control augmentation of lifting surfaces at high angles of attack. Aerospace Science and Technology 2019, 87, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muijres, F.T.; Johansson, L.C.; Hedenström, A. Leading edge vortex in a slow-flying passerine. Biology Letters 2012, 8, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muijres, F.T.; Johansson, L.C.; Barfield, R.; Wolf, M.; Spedding, G.R.; Hedenström, A. Leading-Edge Vortex Improves Lift in. Science 2008, 319, 1250–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videler, J.J.; Stamhuis, E.J.; Povel, G.D. Leading-edge vortex lifts swifts. Science 2004, 306, 1957–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentink, D.; Dickson, W.B.; Van Leeuwen, J.L.; Dickinson, M.H. Leading-edge vortices elevate lift of autorotating plant seeds. Science 2009, 324, 1438–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldredge, J.D.; Jones, A.R. Leading-edge vortices: Mechanics and modeling. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2019, 51, 75–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer, J.; Franchini, S.; Pérez-Grande, I.; Sanz, J.L. On the aerodynamics of leading-edge high-lift devices of avian wings. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part G: Journal of Aerospace Engineering, 2005, Vol. 219, pp. 63–68. [CrossRef]

- Linehan, T.; Mohseni, K. On the maintenance of an attached leading-edge vortex via model bird alula. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2020, 897, 2001.03964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, T.; Mohseni, K. Scaling trends of bird’s alular feathers in connection to leading-edge vortex flow over hand-wing. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, B.; Anderson, A.M. The alula and its aerodynamic effect on avian flight. ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Proceedings (IMECE) 2007, 7, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.I.; Kim, J.; Park, H.; Jabłoński, P.G.; Choi, H. The function of the alula in avian flight. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.R.; Duan, C.; Wissa, A.A. The function of the alula on engineered wings: A detailed experimental investigation of a bioinspired leading-edge device. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubel, T.Y.; Tropea, C. The importance of leading edge vortices under simplified flapping flight conditions at the size scale of birds. Journal of Experimental Biology 2010, 213, 1930–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sander, A. The Role of the Alula in Avian Flight and Its application to Small Aircraft: A Numerical Study. PhD thesis, University of Grogingen, 2018.

- Ge, C.; Ren, L.; Liang, P.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z. High-Lift effect of bionic slat based on owl wing. Journal of Bionic Engineering 2013, 10, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, M. Dynamic soaring : aerodynamics for albatrosses Dynamic soaring : aerodynamics for 2009. [CrossRef]

- Pennycuick, C.J. Gust soaring as a basis for the flight of petrels and albatrosses (Procellariiformes). Avian Science 2002, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Videler, J.J. Bird flight modes. In Avian Flight; Oxford Academic, 2006; chapter 6, pp. 118–155. [CrossRef]

- Hassanalian, M.; Abdelmoula, H.; Ben Ayed, S.; Abdelkefi, A. Thermal impact of migrating birds’ wing color on their flight performance: Possibility of new generation of biologically inspired drones. Journal of Thermal Biology 2017, 66, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; Bouten, W.; Camphuysen, K.C.; Nolet, B.A.; Shamoun-Baranes, J. Energetic and behavioral consequences of migration: an empirical evaluation in the context of the full annual cycle. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahy-Rewald, O.; Perinot, E.; Fritz, J.; Vyssotski, A.L.; Fusani, L.; Voelkl, B.; Ruf, T. Empirical Evidence for Energy Efficiency Using Intermittent Gliding Flight in Northern Bald Ibises. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamoun-Baranes, J.; van Loon, E.; van Gasteren, H.; van Belle, J.; Bouten, W.; Buurma, L. A Comparitive Analysis Of The Influence Of Weather On The Flight Altitudes Of Birds. American Meteorological Society 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.M. Bounding and undulating flight in birds. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1985, 117, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.M.V. A New Approach to Animal Flight Mechanics. Journal of Experimental Biology 1979, 80, 17–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, I.; Eisa, S.A.; Maqsood, A. Review of dynamic soaring: technical aspects, nonlinear modeling perspectives and future directions. Nonlinear Dynamics 2018, 94, 3117–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Atabi, M. Aerodynamics of wing tip sails mushtak al-atabi. 2006; 1, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Dai, C. Experimental Study on Ground Effect of a Wing with Tip Sails; Vol. 126, Elsevier B.V., 2015; pp. 559–563. [CrossRef]

- Gavrilović, N.N.; Rašuo, B.P.; Dulikravich, G.S.; Parezanović, V.B. Commercial aircraft performance improvement using winglets. FME Transactions 2015, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.; Chou, H.C.; Lien, K.W. Aerodynamic efficiency study of modern spiroid winglets. ICAS-Secretariat - 25th Congress of the International Council of the Aeronautical Sciences 2006 2006, 2, 707–713. [Google Scholar]

- Falcão, L.; Gomes, A.A.; Suleman, A. Design and analysis of an adaptive wingtip. In Proceedings of the 52nd AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics and Materials Conference, 2011, number April. [CrossRef]

- Van Bokhorst, E.; De Kat, R.; Elsinga, G.E.; Lentink, D. Feather roughness reduces flow separation during low Reynolds number glides of swifts. Journal of Experimental Biology 2015, 218, 3179–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servini, P. Roughing up wings: boundary layer separation over static and dynamic roughness elements. Doctoral dissertation, UCL (University College London), 2018.

- Maybury, W.J.; Rayner, J.M. The avian tail reduces body parasite drag by controlling flow separation and vortex shedding. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2001, 268, 1405–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, V.A. Body drag, feather drag and interference drag of the mounting strut in a peregrine falcon, Falco peregrinus. Journal of Experimental Biology 1990, 149, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycuick, C.J.; Obrecht, H.H.; Fuller, M.R. Empirical Estimates of Body Drag of Large Waterfowl and Raptors. Journal of Experimental Biology 1988, 135, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, L.; Xiao, T.; Yohann, D.; Jung, S.; Kanso, E. Dynamics of water entry. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2018, 846, 508–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, J.; Jaramillo, A.; Hayes, F. Bird Guide Training Curriculum: Advanced Level; National Audubon Society, 2015; p. 5.

- Ropert-Coudert, Y.; Grémillet, D.; Ryan, P.; Kato, A.; Naito, Y.; Le Maho, Y. Between air and water: The plunge dive of the Cape Gannet Morus capensis. Ibis 2004, 146, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, R. Diving energetics in lesser scaup (Aythyta affinis, Eyton). Journal of Experimental Biology 1994, 190, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Croson, M.; Straker, L.; Gart, S.; Dove, C.; Gerwin, J.; Jung, S. How seabirds plunge-dive without injuries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016, 113, 12006–12011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, C.T.; Omar, B.; Taib, I. Shape Optimization of High-Speed Rail by Biomimetic. MATEC Web of Conferences 2017, 135, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laman, T. Vogelkop Lophorina ML62128001, 2017.

- Bissett, K.; Duncan, J. Victoria’s Riflebird (Ptiloris victoriae) ML384020521, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R, W. Greater Sage-Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) ML432171241, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Venetz, C. Wilson’s Bird-of-Paradise (Diphyllodes respublica) ML588187181, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Seminario, Y. Crimson-backed Tanager (Ramphocelus dimidiatus) ML314404811, 2013. [CrossRef]

- De Munck, P. Resplendent Quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno) ML251030911, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Videler, J.; Groenewold, A. Field measurements of hanging flight aerodynamics in the kestrel Falco tinnunculus. Journal of Experimental Biology 1991, 155, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.; Inman, D.J. Aerodynamic efficiency of gliding birds vs comparable UAVs: A review. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zufelt, K. Manx Shearwater ML216800971, 2020.

- Ornelas, R. White Pelican Pelecanus onocrotalus, 2006.

- Hunt, S. High Soarer, 2015.

- Patel, C.; Lee, H.T.; Kroo, I. Extracting energy from atmospheric turbulence with flight tests. Technical Soaring 2009, 33, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Katzmayr, R. Effect of periodic changes in angle of attack on behavior of airfoils. Technical Report NACA-TM-147, NACA, 1922.

- Lissaman, P. Wind energy extraction by birds and flight vehicles. In Proceedings of the 43rd AIAA aerospace sciences meeting and exhibit. AIAA, January 2005, p. 241.

- Rayner, J. The intermittent flight of birds. In Scale effects in animal locomotion; Academic Press: London, 1977; chapter The interm, pp. 437–444.

- Rayner, J.M. A vortex theory of animal flight. Part 1. The vortex wake of a hovering animal. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1979, 91, 697–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.M. A vortex theory of animal flight. Part 1. The vortex wake of a hovering animal. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1979, 91, 697–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobalske, B.W. Hovering and intermittent flight in birds. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobalske, B.W.; Peacock, W.L.; Dial, K.P. Kinematics of flap-bounding flight in the zebra finch over a wide range of speeds. Journal of Experimental Biology 1999, 202, 1725–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobalske, B.W. Morphology, velocity, and intermittent flight in birds’. American Zoologist 2001, 41, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobalske, B.W. Scaling of muscle composition, wing morphology, and intermittent flight behavior in woodpeckers. Auk 1996, 113, 151–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battell, R.; Battell, M. Image of the Day.

- Chaplin, S. Bounding Flight, 2019.

- Rayner, J.M.; Viscardi, P.W.; Ward, S.; Speakmanf, J.R. Aerodynamics and energetics of intermittent flight in birds1. American Zoologist 2001, 41, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, H.a. A Literature Review on Bounding Flight in Birds With Applications to Micro Uninhabited Air Vehicles. Semantic Scholar.

- Videler, J.J.; Weihs, D.; Daan, S. Intermittent Gliding in the Hunting Flight of the Kestrel, Falco Tinnunculus L. Journal of Experimental Biology 1983, 102, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Vejdani, H.R.; Boerma, D.B.; Swartz, S.M.; Breuer, K.S. The dynamics of hovering flight in hummingbirds, insects and bats with implications for aerial robotics. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 2019, 14, 0–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrick, D.R.; Tobalske, B.W.; Powers, D.R. Aerodynamics of the hovering hummingbird. Nature 2005, 435, 1094–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.M. Avian flight energetics. Annual review of physiology 1982, 44, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Ren, Z.; Jiang, C.; Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Nabi, G.; Wu, Y.; Li, D. A comparison of flight energetics and kinematics of migratory Brambling and residential Eurasian Tree Sparrow. Avian Research 2020, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, P.; Chen, J.S.; Dudley, R. Transient hovering performance of hummingbirds under conditions of maximal loading. Journal of Experimental Biology 1997, 200, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muijres, F.T.; Johansson, L.C.; Bowlin, M.S.; Winter, Y.; Hedenström, A. Comparing aerodynamic efficiency in birds and bats suggests better flight performance in birds. PLoS ONE 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, D. Formation flight as an energy -saving mechanism. Israel Journal of Zoology 1995, 41, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, D. Formation Flight as an Energy-Saving Mechanism. Progress in Aerospace Sciences 2000, 35, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Ponce, J.; Urban, C.; Armanini, S.F.; Agarwal, R.K.; Hassanalian, M. Aerodynamic Analysis of V-Shaped Flight Formation of Flapping-Wing Drones: Analytical and Experimental Studies. In Proceedings of the AIAA SCITECH 2022 Forum. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, dec 2021, AIAA SciTech Forum, p. 1979. [CrossRef]

- Gould, L.; Heppner, F. The Vee Formation of Canada Geese. The Auk 1974, 91, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portugal, S.J.; Hubel, T.Y.; Fritz, J.; Heese, S.; Trobe, D.; Voelkl, B.; Hailes, S.; Wilson, A.M.; Usherwood, J.R. Upwash exploitation and downwash avoidance by flap phasing in ibis formation flight. Nature 2014, 505, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henise, D. American White Pelican, 2016.

- Weimerskirch, H.; Martin, J.; Clerquin, Y.; Alexandre, P.; Jiraskova, S. Energy saving in flight formation. Nature 2001, 413, 697–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, J. ’V’ is for Vamoose, 2007.

- Hajihusseini, H. Eurasian Cranes migrating to Meyghan Salt Lake, 2010.

- Scott, J. V-Formation Flight of Birds, 2005.

- Cutts, C.J.; Speakman, J.R. Energy savings in formation flight of pink-footed geese. Journal of Experimental Biology 1994, 189, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higdon, J.J.L.; Corrsin, S. Induced Drag of a Bird Flock. The American Naturalist 1978, 112, 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelkl, B.; Portugal, S.J.; Unsölde, M.; Usherwood, J.R.; Wilsond, A.M.; Fritz, J. Matching times of leading and following suggest cooperation through direct reciprocity during V-formation flight in ibis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2015, 112, 2115–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppner, F.H.; Convissar, J.L.; Moonan, D.E.; John, G.; Anderson, T.; Auk, S.T.; Jan, N. Visual Angle and Formation Flight in Canada Geese (Branta canadensi. The Auk: Ornithological Advances 1985, 102, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.A. Aircraft Drag Reduction Through Extended Formation Flight. PhD thesis, STANFORD UNIVERSITY, 2011.

- Pahle, J.; Berger, D.; Venti, M.; Duggan, C.; Faber, J.; Cardinal, K. An initial flight investigation of formation flight for drag reduction on the C-17 aircraft. AIAA Atmospheric Flight Mechanics Conference 2012 2012, pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-ponce, J.; Herkenhoff, B.; Aboelezz, A.; Hassanalian, M. Load Distribution on “ V ” and Echelon Formation Flight of. In Proceedings of the AIAA SciTech Forum, Orlando, FL, 2024; Number January. [CrossRef]

- Lambach, J.L. Integrating UAS Flocking Operations with Formation Drag, Thesis. Air Force Institue of Technology 2014, p. 99.

- Mirzaeinia, A.; Heppner, F.; Hassanalian, M. An analytical study on leader and follower switching in V-shaped Canada Goose flocks for energy management purposes. Swarm Intelligence 2020, 14, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaeinia, A.; Hassanalian, M.; Lee, K.; Mirzaeinia, M. Energy conservation of V-shaped swarming fixed-wing drones through position reconfiguration. Aerospace Science and Technology 2019, 94, 105398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshatriya, M.; Blake, R.W. Theoretical model of the optimum flock size of birds flying in formation. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1992, 157, 135–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thien, H.P.; Moelyadi, M.A.; Muhammad, H. Effects of Leaders Position and Shape on Aerodynamic Performances of V Flight Formation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Unmanned System; 2008; pp. 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, M.; Wallander, J. Kin selection and reciprocity in flight formation? Behavioral Ecology 2004, 15, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.M.; Gilchrist, H.G.; Ronconi, R.A.; Shlepr, K.R.; Clark, D.E.; Fifield, D.A.; Robertson, G.J.; Mallory, M.L. Both short and long distance migrants use energy-minimizing migration strategies in North American herring gulls. Movement Ecology 2020, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somveille, M.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Manica, A. Energy efficiency drives the global seasonal distribution of birds. Nature Ecology and Evolution 2018, 2, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somveille, M.; Wikelski, M.; Beyer, R.M.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Manica, A.; Jetz, W. Simulation-based reconstruction of global bird migration over the past 50,000 years. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alerstam, T.; Lindström, Å. Optimal bird migration: the relative importance of time, energy and safety. – In: Gwinner, E. (ed) Bird Migration: The Physiology and ecophysiology. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. pp. 331-351. Springer 1990, pp. 331–351.

- Acácio, M.; Catry, I.; Soriano-Redondo, A.; Silva, J.P.; Atkinson, P.W.; Franco, A.M. Timing is critical: consequences of asynchronous migration for the performance and destination of a long-distance migrant. Movement Ecology 2022, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourani, E.; Yamaguchi, N.M.; Higuchi, H. Climate change alters the optimal wind-dependent flight routes of an avian migrant. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2017, 284, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzone, M.J.; Miller, T.A.; Turk, P.; Brandes, D.; Halverson, C.; Maisonneuve, C.; Tremblay, J.; Cooper, J.; O’Malley, K.; Brooks, R.P.; et al. Flight responses by a migratory soaring raptor to changing meteorological conditions. Biology Letters 2012, 8, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüppel, G.; Hüppop, O.; Lagerveld, S.; Schmaljohann, H.; Brust, V. Departure, routing and landing decisions of long-distance migratory songbirds in relation to weather. Royal Society Open Science 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranstauber, B.; Weinzierl, R.; Wikelski, M.; Safi, K. Global aerial flyways allow efficient travelling. Ecology Letters 2015, 18, 1338–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S. Migratory behaviour of Eastern Whip-poor- wills ( Antrostomus vociferus ): quantifying return rates and the effects of artificial light on flight paths. PhD thesis, University of Manitoba, 2023.

- Dokter, A.M.; Liechti, F.; Stark, H.; Delobbe, L.; Tabary, P.; Holleman, I. Bird migration flight altitudes studied by a network of operational weather radars. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2010, 8, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, M.U.; Shamoun-Baranes, J.; Dokter, A.M.; van Loon, E.; Bouten, W. The influence of weather on the flight altitude of nocturnal migrants in mid-latitudes. International Journal of Avian Science 2013, 155, 734–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Rodríguez, M.; Liechti, F. How do diurnal long-distance migrants select flight altitude in relation to wind? Behavioral Ecology 2012, 23, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.R. Elevated performance: The unique physiology of birds that fly at high altitudes. Journal of Experimental Biology 2011, 214, 2455–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altshuler, D.L. The physiology and biomechanics of avian flight at high altitude. Integrative and Comparative Biology 2006, 46, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B. Bird Flight Over Water | Loyola University Center for Environmental Communication, 2011.

- Cutler, C. Ground effect: Why You Float During Landing, 2020.

- Herkenhoff, B.; Hassanalian, M. Potential Applications and Integration of Ground Effects on Amphibious Drones: Shearwaters and Bioinspiration. AIAA AVIATION 2022 Forum 2022, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Yang, Y.; Kiong Soh, C.; Halvorsen, E.; Nguyen, S.D.; Mann, B.P.; Pozzi, M.; Zhu, M.; Benasciutti, D.; Moro, L.; et al. Advances in Energy Harvesting Methods; Springer, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Whitney, J. Design and Performance of Insect-Scale Flapping-Wing Vehicles. PhD thesis, Harvard University, 2012.

- Ray, R.P.; Nakata, T.; Henningsson, P.; Bomphrey, R.J. Enhanced flight performance by genetic manipulation of wing shape in Drosophila. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterfield, D.A.; Davis, A.K. Variation in wing characteristics of monarch butterflies during migration: Earlier migrants have redder and more elongated wings. Animal Migration 2014, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.; Walker, S.M.; Bomphrey, R.J.; Taylor, G.K.; Thomas, A.L. Details of insect wing design and deformation enhance aerodynamic function and flight efficiency. Science 2009, 325, 1549–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootton, R. The geometry and mechanics of insect wing deformations in flight: A modelling approach. Insects 2020, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, T.; Kolomenskiy, D.; Lehmann, F.O. Flight efficiency is a key to diverse wing morphologies in small insects. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, L.C.; Henningsson, P. Butterflies fly using efficient propulsive clap mechanism owing to flexible wings: Butterflies fly using efficient propulsive clap mechanism owing to flexible wings. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flockhart, D.T.; Fitz-gerald, B.; Brower, L.P.; Derbyshire, R.; Altizer, S.; Hobson, K.A.; Wassenaar, L.I.; Norris, D.R. Migration distance as a selective episode for wing morphology in a migratory insect. Movement Ecology 2017, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.; Cho, M.; Wehmann, H.N.; Engels, T.; Lehmann, F.O. Wing design in flies: Properties and aerodynamic function. Insects 2020, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Nabawy, M.R. Wing Planform Effect on the Aerodynamics of Insect Wings. Insects 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, P.; Song, F.; Sun, J. Wing shape optimization design inspired by beetle hindwings in wind tunnel experiments. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2021, 135, 104642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, T.; Wehmann, H.N.; Lehmann, F.O. Three-dimensional wing structure attenuates aerodynamic efficiency in flapping fly wings. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Kolomenskiy, D.; Liu, H. The impact of insect wing shape on the formation of leading edge vortex. The Proceedings of the Bioengineering Conference Annual Meeting of BED/JSME 2017, 2017.29, 2F22. [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.A.; Cribb, B.W.; Hu, H.M.; Watson, G.S. A dual layer hair array of the brown lacewing: Repelling water at different length scales. Biophysical Journal 2011, 100, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Tu, Z.; Li, D.; Kan, Z.; Xiang, J. Aerodynamic Characteristics of Bristled Wings in Flapping Flight. Aerospace 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolomenskiy, D. Recent Progress in the Biomechanics of Flight of Miniature Insects with Bristled Wings. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 2023, 92, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, F.; Lehmann, F.O. Flow development and leading edge vorticity in bristled insect wings. Journal of Comparative Physiology A: Neuroethology, Sensory, Neural, and Behavioral Physiology 2023, 209, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Callaghan, F.; Sarig, A.; Ribak, G.; Lehmann, F.O. Efficiency and Aerodynamic Performance of Bristled Insect Wings Depending on Reynolds Number in Flapping Flight. Fluids 2022, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, S.A.; Daniel, T.L. Flexural stiffness in insect wings: Effects of wing venation and stiffness distribution on passive bending. American Entomologist 2005, 51, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, J.H.; Taylor, D. Veins improve fracture toughness of insect wings. PLoS ONE 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, H.E.; Schwab, R.K.; Maxcer, M.; Peterson, R.K.; Johnson, E.L.; Jankauski, M. Wing flexibility reduces the energetic requirements of insect flight. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, M.K.; Socha, J.J. Circulation in insect wings. Integrative and Comparative Biology 2020, 60, 1208–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Gu, J.; Fan, T.; Liu, Q.; Su, H.; Zhu, S. Inspiration from butterfly and moth wing scales: Characterization, modeling, and fabrication. Progress in Materials Science 2015, 68, 67–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slegers, N.; Heilman, M.; Cranford, J.; Lang, A.; Yoder, J.; Habegger, M.L. Beneficial aerodynamic effect of wing scales on the climbing flight of butterflies. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.W. Microscopic scales enhance a butterfly’s flying efficiency, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wilroy, J.; Wahidi, R.A.; Lang, A. Effect of butterfly-scale-inspired surface patterning on the leading edge vortex growth. Fluid Dynamics Research 2018, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badejo, O.; Skaldina, O.; Gilev, A.; Sorvari, J. Benefits of insect colours : a review from social insect studies. Oecologia 2020, 194, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osotsi, M.I.; Zhang, W.; Zada, I.; Gu, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, D. Butterfly wing architectures inspire sensor and energy applications. National Science Review 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.K.; Chi, J.; Bradley, C.; Altizer, S. The redder the better: Wing color predicts flight performance in monarch butterflies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.K.; Herkenhoff, B.; Vu, C.; Barriga, P.A.; Hassanalian, M. How the monarch got its spots: Long-distance migration selects for larger white spots on monarch butterfly wings. PloS one 2023, 18, e0286921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, G.J.; Wang, Z.J. Energy-minimizing kinematics in hovering insect flight. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2007, 582, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhou, C.; Zhu, X. Influences of flapping modes and wing kinematics on aerodynamic performance of insect hovering flight. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology 2020, 34, 1603–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, S.N.; Sayaman, R.; Dickinson, M.H. The aerodynamics of hovering flight in Drosophila. Journal of Experimental Biology 2005, 208, 2303–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roy, C.; Amadori, D.; Charberet, S.; Windt, J.; Muijres, F.T.; Llaurens, V.; Debat, V. Adaptive evolution of flight in Morpho butterflies. Science 2021, 374, 1158–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cespedes, A.; Penz, C.M.; Devries, P.J. Cruising the rain forest floor: Butterfly wing shape evolution and gliding in ground effect. Journal of Animal Ecology 2015, 84, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena, S.; Kozak, K.M.; Cárdenas, R.E.; Checa, M.F. Forest stratification shapes allometry and flight morphology of tropical butterflies: Stratification and butterfly morphology. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2020, 287, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, J. Experimental investigation on aerodynamic performance of gliding butterflies. AIAA Journal 2010, 48, 2454–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, C.R.; Wootton, R.J. Wing Shape and Flight Behaviour in Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea and Hesperioidea): A Preliminary Analysis. Journal of Experimental Biology 1988, 138, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeling, J.M.; Ellington, C.P. Dragonfly flight: I gliding flight and steady-state aerodynamic forces. Journal of Experimental Biology 1997, 200, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, P.; Chaugule, S. Thermal Soaring and Control Surface Dynamics of an Eagle and the Hummingbird’s Flapping Flight Aerodynamics. International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology 2022, 10, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, S.; Vale, M.; Firth, L.; Burrows, M.; Mieszkowska, N.; Frost, M. Sustained Observation of Marine Biodiversity and Ecosystems. Oceanography: Open Access 2013, 01, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbi, S.R.; Sandifer, P.A.; Allan, J.D.; Beck, M.W.; Fautin, D.G.; Fogarty, M.J.; Halpera, B.S.; Incze, L.S.; Leong, J.A.; Norse, E.; et al. Managing for ocean biodiversity to sustain marine ecosystem services. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2009, 7, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, J.E.; Amaral-Zettler, L.A.; Fautin, D.G.; Paulay, G.; Rynearson, T.A.; Sosik, H.M.; Stachowicz, J.J. Envisioning a marine biodiversity observation network. BioScience 2013, 63, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolich, A.; Palma, D.; Kansanen, K.; Fjørtoft, K.; Sousa, J.; Johansson, K.H.; Jiang, Y.; Dong, H.; Johansen, T.A. Survey on Communication and Networks for Autonomous Marine Systems. Journal of Intelligent and Robotic Systems: Theory and Applications 2019, 95, 789–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynne, P.F.; Von Ellenrieder, K.D. Unmanned autonomous sailing: Current status and future role in sustained ocean observations. Marine Technology Society Journal 2009, 43, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.; Austin, T.; Forrester, N.; Goldsborough, R.; Kukulya, A.; Packard, G.; Purcell, M.; Stokey, R. Autonomous docking demonstrations with enhanced REMUS technology. In Proceedings of the OCEANS; 2006; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meindl, A. Guide to moored buoys and other ocean data acquisition systems. Data Buoy Cooperation Panel 1996, 8, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Shashati, M.; Ain, A.; Zeyoudi, S.A.; Ain, A.; Ain, A.; Khatib, O.A.; Ain, A.; Ain, A.; Hakim, A. Design and Fabrication of a Solar Powered Unmanned Aerial Vehicle ( UAV ). 2023 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET) 2023, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Nileshkumar, S.K.; Prince, P.; Mukulbhai, K.J. Design and Development of Solar Drone. International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology 2023.

- Buzdugan, A.; Bălteanu, A. Numerical Modeling of an Energy Management System for a UAV Design Powered by Photovoltaic Cells. Review of the Air Force Academy 2022, 2, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]