1. Introduction

Plastic waste is a significant global pollution issue, especially concerning single-use plastic packaging. Plastic waste like polypropylene, polyethylene, and polystyrene can take hundreds of years to decompose [

1]. The idea of utilizing biodegradable polymers for different types of plastic packaging has emerged as a potential solution to replace conventional plastics and mitigate pollution caused by plastic waste. Biodegradable polymers are those that can be degraded by simple hydrolysis reactions, and the products can be further degraded by microorganisms [

2,

3].

Biodegradable polymers can be categorized into two main types: petroleum-based polymers and bio-based polymers. Petroleum-based polymers include poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), poly(butylene adipate-

co-terephthalate) (PBAT), and poly(butylene succinate) (PBS). In contrast, bio-based polymers consist of poly(lactic acid) (PLA), polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), and natural materials, which include polysaccharides (such as starch, cellulose, chitosan, guar gum, agar, alginate, and carrageenan) as well as proteins (including silk sericin, silk fibroin, and keratin). Biodegradable and bio-based polymers have a lower carbon footprint compared to their petroleum-based counterparts [1,4−6]. Currently, numerous reports highlight research and development efforts that focus on biodegradable and bio-based polymers for packaging applications [

4,

6,

7]. This innovative material is being explored not only for its environmental benefits but also for its potential to meet the growing demand for eco-friendly and sustainable packaging solutions. As research advances, researchers are optimizing the performance characteristics of these polymers to improve their suitability for commercial packaging applications.

Guar gum (GG) is a high-molecular-weight polysaccharide that is specifically classified as a polymer of galactomannan. It is composed of mannose sugar molecules linked by

β-1,4-glycosidic bonds, with galactose sugar branches connected by

α-1,6-bonds. GG has been widely studied and developed for various applications, including biomedical [

8,

9], the food industry [

8], wastewater treatment [

8,

10], cosmetics [

8], the petroleum industry [

11], and packaging [

8,

12,

13]. GG is a hydrocolloid that has garnered significant attention for its potential as a food packaging material, primarily due to its low cost and widespread availability. However, in the past, industrial production has encountered considerable limitations because it has relied almost exclusively on the solution casting technique for the formation of GG-based packaging products. To the best of our knowledge, there have been scarcely any reports on the formation of GG-based films using the melt processing techniques [

14]. This research is the first report to document the production of GG films using the compression molding technique.

Polysaccharide films typically contain glycerol as a plasticizer to improve their flexibility. Before casting, glycerol is incorporated into GG films by mixing it with the GG solution [15−19]. Microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) is a natural filler derived from agricultural waste materials [

20,

21]. It plays an active role in the formulation of various polysaccharide films, enhancing their strength [22−25]. When external forces apply, the hydrogen bonding between microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) and the polysaccharide facilitates effective stress transfer. This study employed glycerol as a plasticizer and microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) as a reinforcing filler in the formulation of thermo-compressed GG films. We hypothesized that glycerol and microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) would influence the flexibility and strength of the thermo-compressed GG films. To evaluate this hypothesis, we conducted two sample series (glycerol-plasticized GG films and MCC-reinforced/glycerol-plasticized GG films) of tensile tests. We also determined the chemical structures, phase morphology, thermal stability, crystalline structures, moisture content, and opacity of the thermo-compressed GG films.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

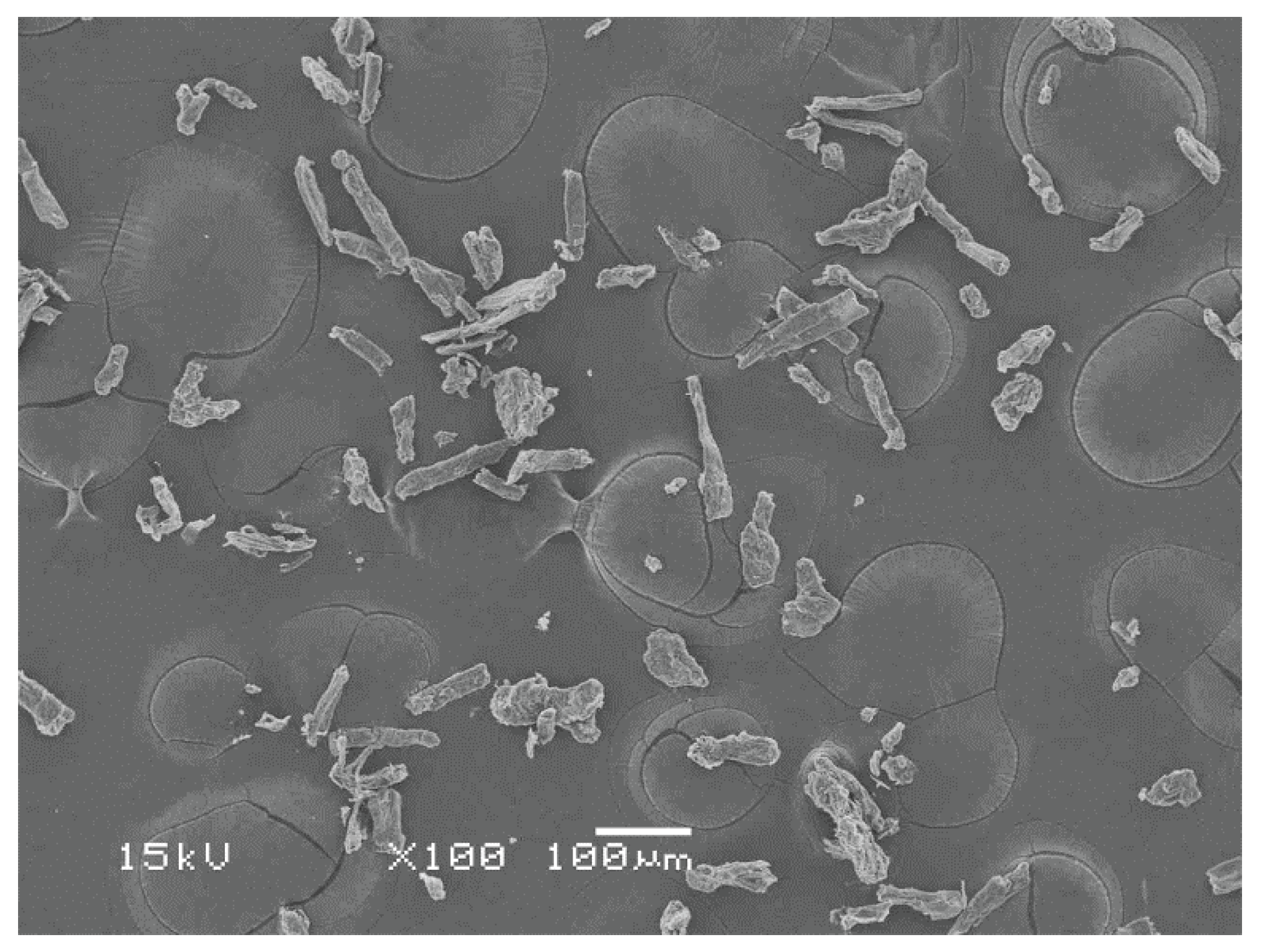

Food-grade guar gum (GG) powder with 82% min galactomannan content and a viscosity of 6000 cps (1% aqueous solution) was purchased from Chanjao Longevity Co., Ltd. (Bangkok, Thailand). Microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) with an average particle size of 50 µm was supplied by Acros Organics (MA, USA).

Figure 1 shows an SEM image of MCC. Glycerol (99.5%) was obtained from QReC (Pathum Thani, Thailand).

2.2. Preparation of Thermo-Compressed GG-Based Films

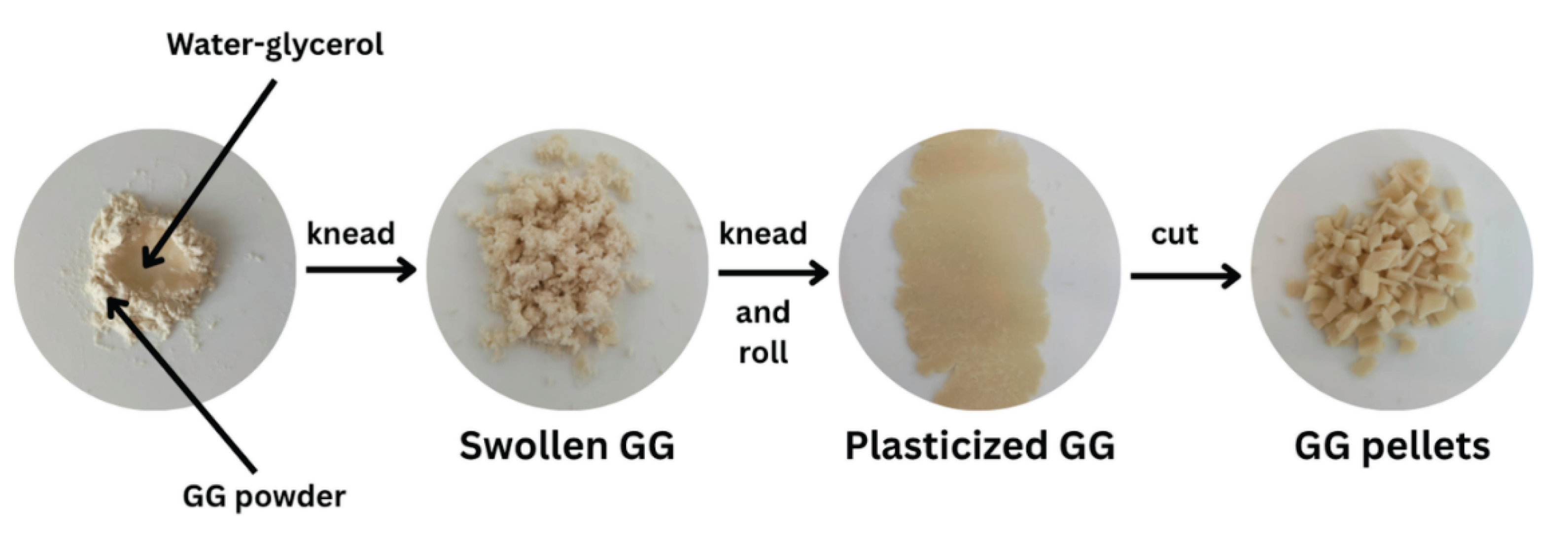

To study the plasticization effectiveness of glycerol on GG film, GG powder (10 g) was mixed with a glycerol aqueous solution (30 g) and kneaded until a homogeneous mixture was achieved. The mixture was then rolled and cut into pellets, as illustrated in

Figure 2. We investigated glycerol contents of 0, 15, 30, and 45 wt% based on the weight of GG. The plasticized GG pellets were subjected to thermo-compression at 120°C for a duration of 5 minutes, applying a force of 5 MPa using an Auto CH Carver hot-press machine (Wabash, IN, USA). The films were then cooled using cool plates while maintaining a compressed force of 5 MPa for 5 minutes. The films were fixed on plastic mesh frames and subsequently dried in an airflow oven at 30°C for a duration of 6 hours. Before characterization, the films were stored at room temperature (25−30°C) and at a relative humidity (RH) of 50−60% for 14 days [

26,

27].

To evaluate the reinforcement effectiveness of MCC on glycerol-plasticized GG film, the mixture of GG and MCC was kneaded and rolled with a glycerol aqueous solution, following the same method described previously. We maintained a constant glycerol content of 30 wt%, which was calculated based on the weight of GG. We examined the MCC contents of 5, 10, 20, and 30 wt% based on the weight of GG. The glycerol-plasticized GG pellets mixed with MCC were hot-pressed and then dried at 30°C in an airflow oven for 6 hours before being stored for 14 days using the same methods described earlier before characterization.

Figure 2.

Preparation of glycerol-plasticized GG pellets.

Figure 2.

Preparation of glycerol-plasticized GG pellets.

2.3. Characterization of Thermo-Compressed GG Films

A Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer equipped with attenuated total reflection (ATR) diamond (Invenio-S, Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) was used to analyze the chemical structures of each sample. The ATR-FTIR spectra were collected at a wavenumber range of 500−4000 cm-1 with an accumulation of 32 scans and a resolution of 4 cm-1.

The thermal decomposition behavior of each sample (~10 mg) was analyzed with a thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA, SDT Q600, TA-Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) under nitrogen flow at a rate of 100 mL/min. All the samples were scanned from 50 to 800°C at a heating rate of 20°C/min.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was used to determine the crystalline structures of each sample using an X-ray diffractometer (D8 Advance, Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) with a CuKα source operated at 40 kV and 40 mA. The XRD pattern was recorded from 5 to 60° of 2θ diffraction angle, and the scan rate was 3°/min.

Tensile tests were performed to determine the mechanical properties of the film samples (60 mm × 10 mm) using a universal testing machine (LY-1066B, Dongguan Liyi Environmental Technology Co., Ltd., Dongguan, China) with a 100 kg load cell at 25°C. The test was performed with an initial gauge length of 40 mm and a crosshead speed of 50 mm/min in accordance with ASTM D882-81.

The cryo-fractured surfaces of the film samples prepared in liquid nitrogen were examined with a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM-6460LV, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 15 kV. All samples were sputtered with gold before SEM analysis.

The film samples (20 mm × 20 mm) were weighed (

W1) before drying at 105°C for 24 h. The film samples were weighed again (

W2) after drying. The moisture content of the film samples was calculated using the following equation.

Film opacity of the film samples was determined from absorbance at a wavelength of 600 nm (

A600) using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Cary 60, Agilent Technologies, Victoria, Australia). The film opacity was calculated using the following equation [

28,

29].

where

X is the thickness of the film sample (mm).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The experimental data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan's post hoc test. The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with statistically significant differences at p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Glycerol on Properties of GG Films

3.1.1. FTIR Analysis of Glycerol-Plasticized GG Films

The chemical functional groups present in the films, as well as the potential intermolecular interactions among the film components (GG, water, and glycerol), were analyzed using ATR-FTIR spectra. An ATR-FTIR spectrum of GG powder, as shown in

Figure S1(a), reveals a broad band at 3283 cm⁻¹ corresponding to O−H stretching vibrations and adsorbed water molecules in the film [

14,

19]. A band at 2883 cm⁻¹ shows that C−H stretching vibrations are present [

19,

25]. Additionally, a band at 1639 cm⁻¹ represents the ring stretching of GG and O−H bending associated with water [

30,

31]. The spectrum also shows a band at 1376 cm⁻¹ for C−H bending vibrations and a sharp band at 1016 cm⁻¹ for O−H bending vibrations [

30], as well as C−O−C stretching vibrations from the glycosidic bonds of GG [

25,

32]. Furthermore, a band at 869 cm⁻¹ corresponds to mannose and galactose 1-4 and 1-6 linkages in GG molecules [

17,

32], and a band at 810 cm⁻¹ indicates glycosidic linkages from galactopyranose units in GG molecules [

32,

33].

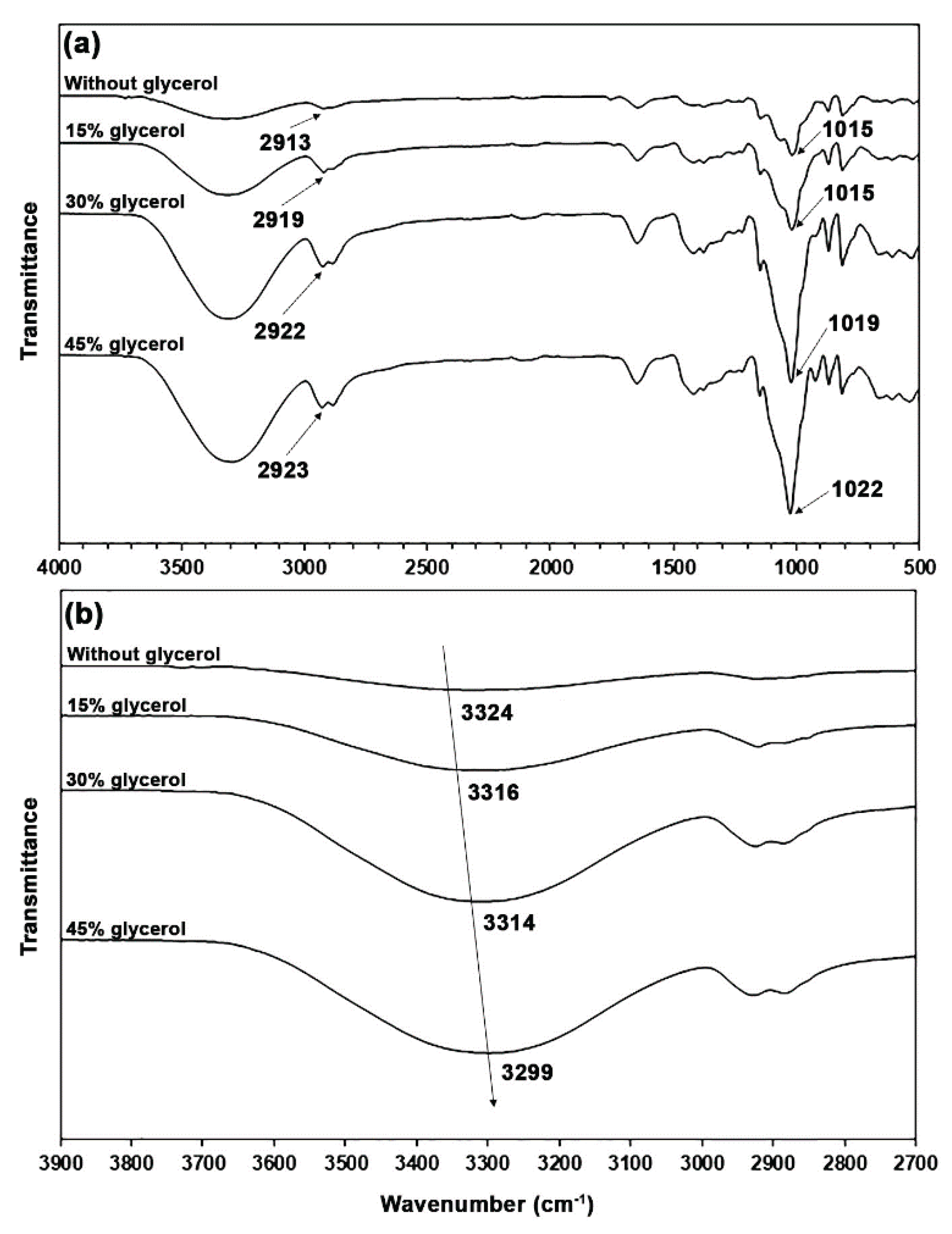

The thermo-compressed GG films with and without glycerol showed the same ATR-FTIR pattern as the GG powder, as shown in

Figure 3(a). However, differences in the intensity of bands could have occurred. The band intensities of O−H stretching vibration in the range of 3000–3700 cm⁻¹ increased with the glycerol content as a result of the increasing hydroxyl groups provided by glycerol. The band intensities in the range of 800−1150 cm⁻¹ attributed to glycerol molecules also increased [

17]. In

Figure 3(b), the O−H band of a glycerol-free GG film at 3324 cm⁻¹ shifted to lower wavenumbers when glycerol plasticizer was incorporated (3316, 3314, and 3299 cm⁻¹ for 15, 30, and 45 wt% glycerol, respectively), which represents the hydrogen-bonding interactions among the hydroxyl groups of GG, absorbed water, and glycerol [

34,

35].

The spectrum of a glycerol-free GG film exhibited a band at 2913 cm⁻¹, indicative of the asymmetric C−H stretching vibration of methylene groups. It was observed at 2919, 2922, and 2923 cm⁻¹ when glycerol was present in concentrations of 15, 30, and 45 wt%, respectively. The observed shift toward higher wavenumbers suggests that there are weaker interactions with the plasticizers [

34]. A band at 1015 cm⁻¹ in a glycerol-free GG film is associated with O−H bending vibrations [

30] and C−O−C stretching vibration linkages from the glycosidic bonds of GG [

25,

32]. Mutlu [

36] attributes this band to interactions between the film matrix and the absorbed water. The band was detected at 1015 cm⁻¹ for a glycerol content of 15 wt%, at 1019 cm⁻¹ for 30 wt%, and at 1022 cm⁻¹ for 45 wt%, respectively. The shift toward higher wavenumbers, which indicates hydrogen bonding between absorbed water and GG, was diminished due to the increased affinity of water for glycerol [

27,

37].

Figure 3.

(a) ATR-FTIR spectra and (b) expanded hydroxyl group regions of glycerol-plasticized GG films with varying glycerol content.

Figure 3.

(a) ATR-FTIR spectra and (b) expanded hydroxyl group regions of glycerol-plasticized GG films with varying glycerol content.

3.1.2. Thermal Decomposition of Glycerol-Plasticized GG Films

We studied the effect of glycerol plasticization on the thermal decomposition behaviors of GG films using thermogravimetric (TG) and derivative TG (DTG) thermograms in the temperature range of 50−800°C. The TG and DTG thermograms of GG powder in

Figure S2(a) demonstrated two major steps of weight loss: the first weight-loss step in the temperature range of 50−120°C is related to the evaporation of residue moisture, and the second weight-loss step in the temperature range of 250−400°C corresponds to the thermal decomposition of GG [

19,

38]. The char residue at 800°C in the GG powder was 16.4%. The maximum decomposition temperature of the GG fraction (

GG-Tmax) obtained from the DTG thermogram was 311°C. This value is similar to that found in previous work [

38].

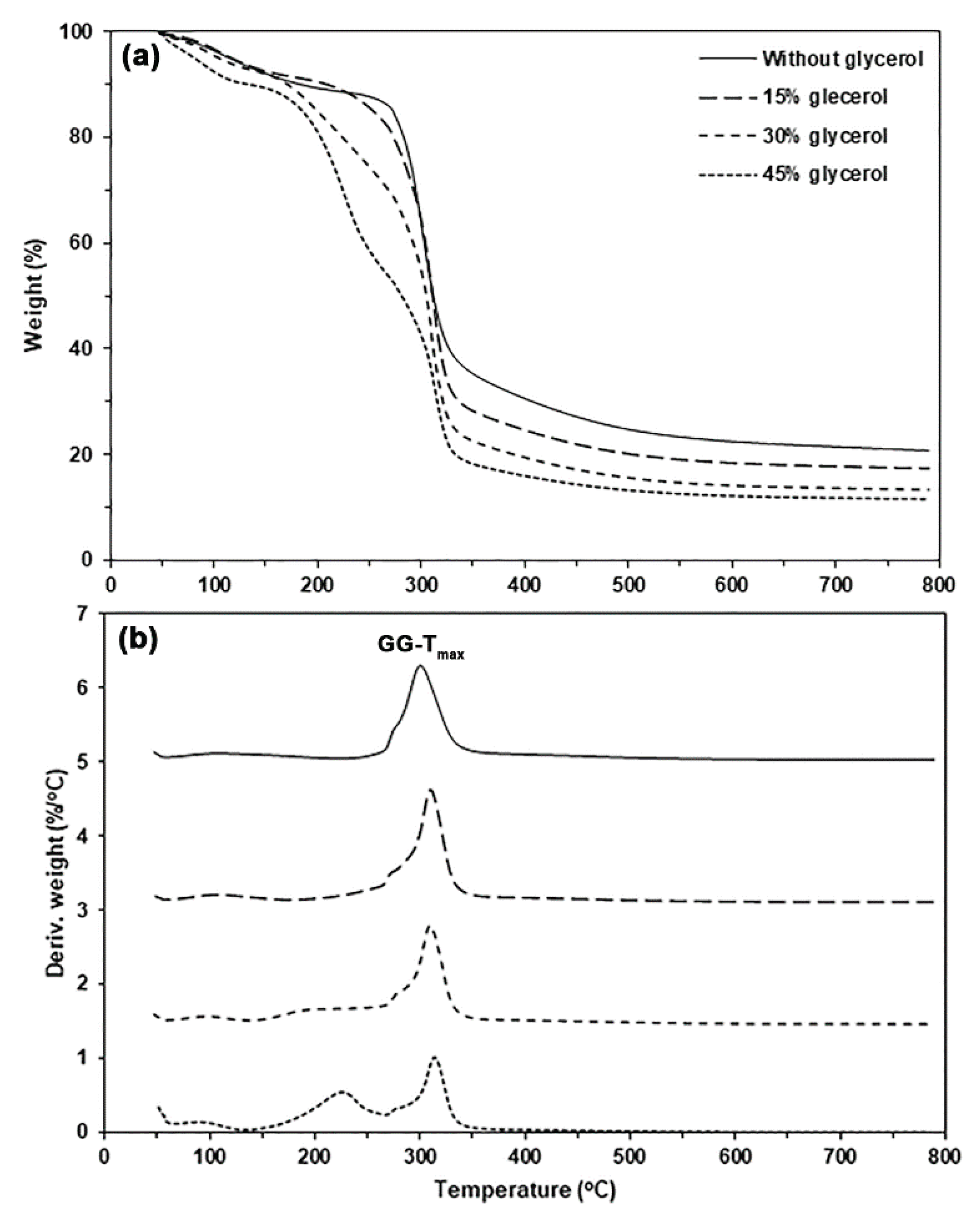

Figure 4 presents the TG and DTG thermograms for both the pure GG and glycerol-plasticized GG films, with a summary of the TGA results provided in

Table 1. The pure GG film exhibited two major steps of weight loss. The first weight-loss step (5.5%) was in the temperature range of 50−120°C, and the second weight-loss step was in the temperature range of 250−400°C, as shown in

Figure 4(a). The char residue at 800°C of the pure GG film was 20.8%. The

GG-Tmax of pure GG film was 300°C. This observation suggests that the thermal decomposition of pure GG film was faster than that of GG powder. This effect may be due to some GG molecules thermally decomposing during the compression molding process.

The TG curves in

Figure 4(a) for glycerol-plasticized GG films displayed a new weight-loss step in the temperature range of 120−260°C, which is attributed to the evaporation of glycerol [

39]. This finding was further corroborated by the appearance of DTG peaks in the temperature range of 120−260°C, as shown in

Figure 4(b). The height of this DTG peak in

Figure 4(b) increased with the glycerol content. The moisture weight loss of glycerol-plasticized GG films, as reported in

Table 1, increased with the glycerol content. Films with greater glycerol content exhibited enhanced hydrophilicity, which improved their moisture absorption during the 14-day storage period. As the glycerol content increased, the char residue at 800°C in the film samples steadily decreased due to a reduction in the GG content of the films. The

GG-Tmax values of glycerol-plasticized GG films (310−314°C) were higher than the pure GG film (300°C), suggesting that the added glycerol improved the thermal stability of GG phases. The added glycerol induced a plasticization effect that rearranged the GG chains to be closer together. This effect may enhance stronger interactions among GG chains.

Figure 4.

(a) TG and (b) DTG thermograms of glycerol-plasticized GG films with varying glycerol content.

Figure 4.

(a) TG and (b) DTG thermograms of glycerol-plasticized GG films with varying glycerol content.

Table 1.

TGA results of glycerol-plasticized GG films.

Table 1.

TGA results of glycerol-plasticized GG films.

Glycerol content

(wt%)

|

Weight loss of moisture

(50−120°C) (%)

|

Char residue

at 800°C

(%)

|

GG-Tmax

(°C)

|

-

15

30

45 |

5.5

5.6

6.2

9.4 |

20.8

17.2

14.6

11.6 |

300

310

311

314 |

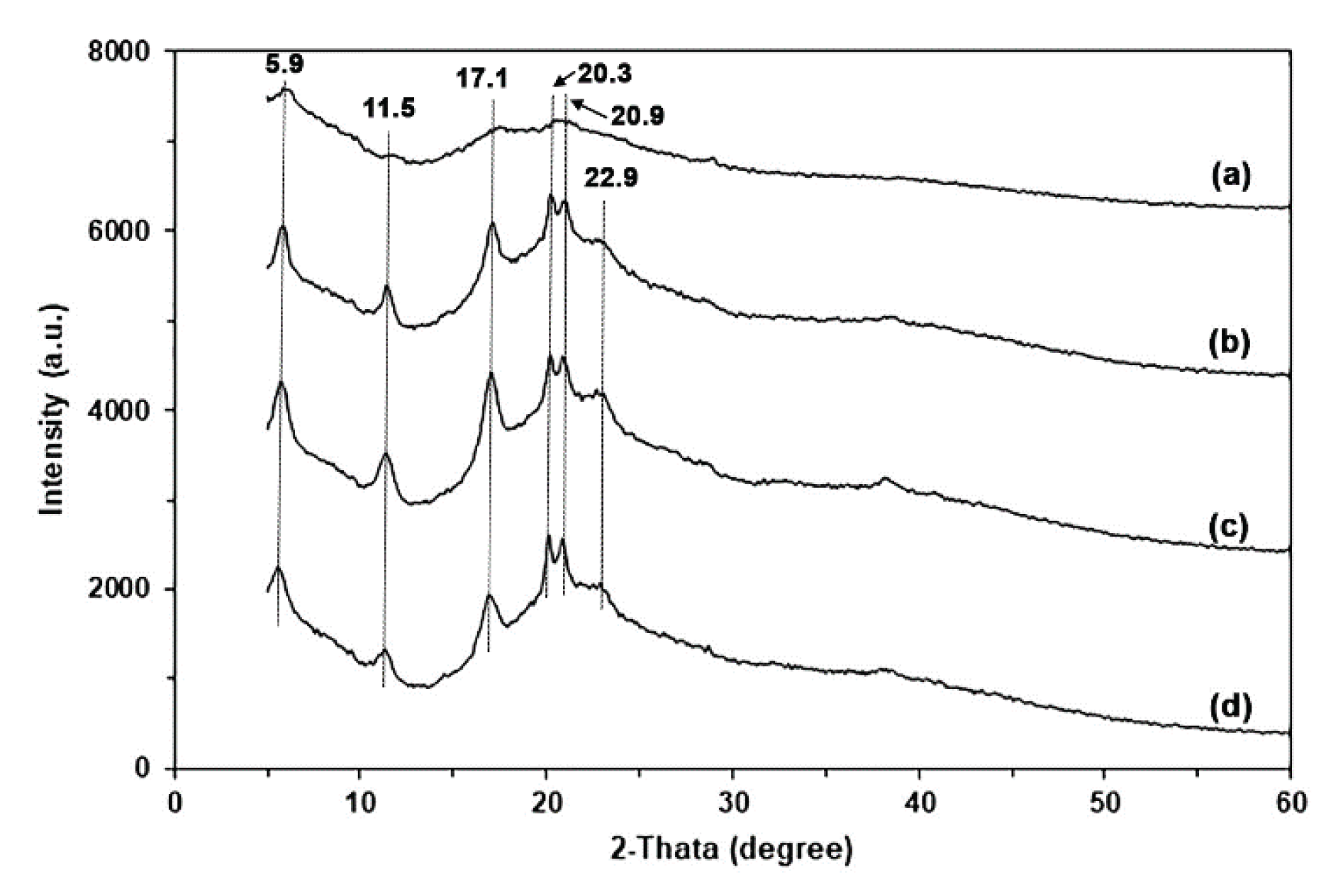

3.1.3. Crystalline Structures of Glycerol-Plasticized GG Films

The XRD pattern of GG powder shown in

Figure S3(a) indicated low overall crystallinity, featuring a small diffraction peak corresponding to the crystalline form of native GG at 2θ = 20.3° [

32,

40].

Figure 5 displays the XRD patterns of GG films, comparing those with glycerol to those without. The glycerol-free GG film exhibited a prominent XRD peak at 2θ = 20.3°, along with smaller XRD peaks at 2θ = 5.9°, 11.5°, and 17.1°. These peaks were more pronounced when glycerol was added. This behavior suggests that the addition of glycerol resulted in an enhanced ordered phase. Furthermore, we noted an increase in the intensities of the XRD peaks at 2θ = 20.3°, 20.9°, and 22.9°. The XRD peaks observed at 5.9° correspond to B-type crystallinity, and 17.1° and 22.9° correspond to A-type crystallinity of polysaccharides [

24,

41]. The presence of water (a de-structuring agent) and glycerol (a non-volatile plasticizer) during compression molding may enhance the chain mobility of GG and improve the arrangement and packing of GG molecules, resulting in a more compact organization within the ordered domains [

42]. The XRD results suggest that water, temperature, compression force, and glycerol significantly influence the formation of crystalline structures within the GG film matrix.

3.1.4. Tensile Properties of Glycerol-Plasticized GG Films

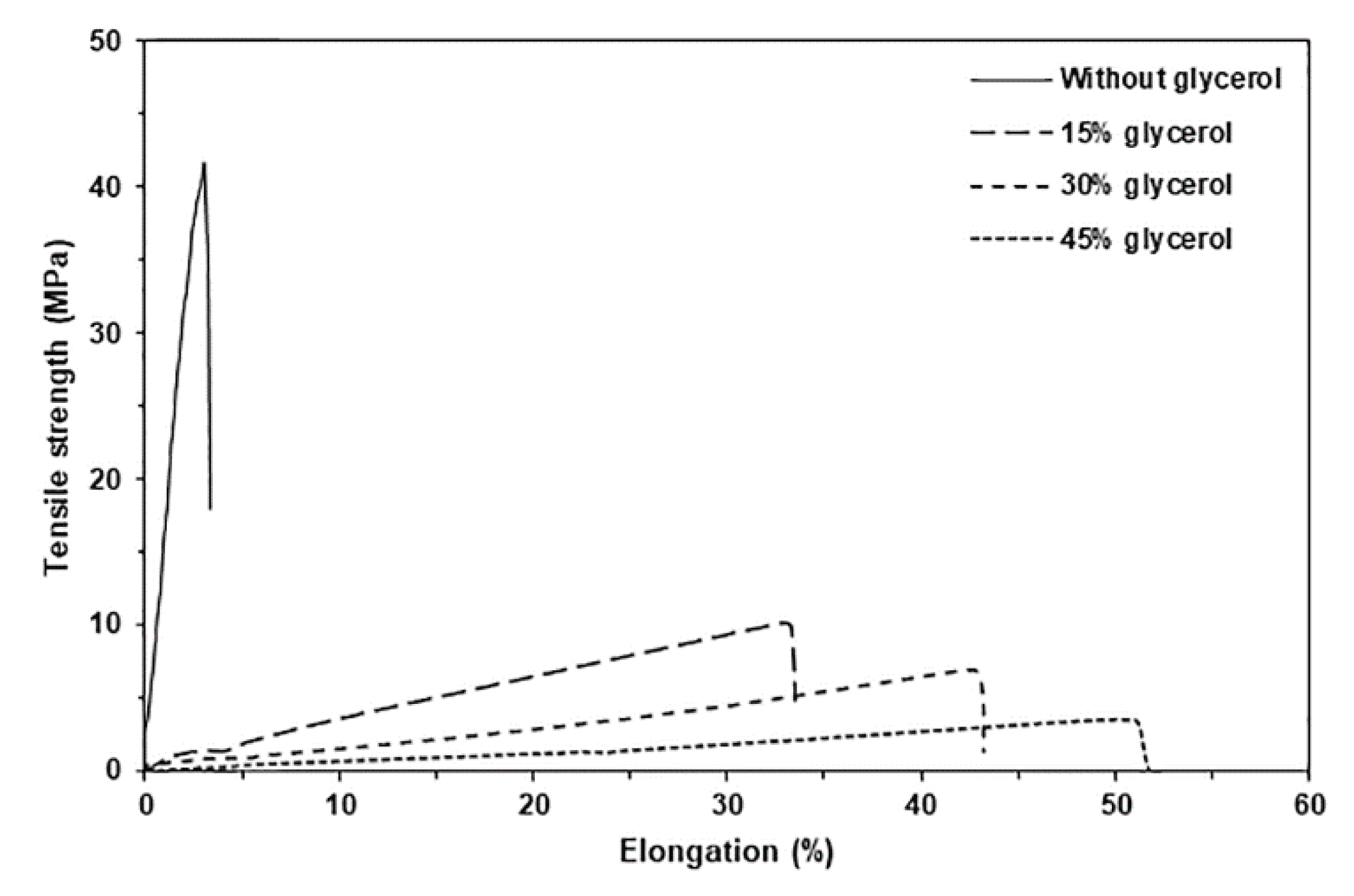

Figure 6 displays selected tensile curves for pure GG and glycerol-plasticized GG films, while

Table 2 provides a summary of the tensile results. The pure GG film exhibited a maximum tensile strength of 40.6 MPa, an elongation at break of 3.4%, and a Young′s modulus of 988.2 MPa. The incorporation of glycerol led to a significant decrease in both the maximum tensile strength and Young′s modulus values, while the elongation at break increased dramatically. This finding suggests that glycerol acts as an effective plasticizer for the GG. Glycerol is a common plasticizer for polysaccharides because it enhances their chain mobility by reducing intermolecular forces between polymer chains, making them more flexible and less rigid [

43]. Various starch films also demonstrated this behavior [44−47]. In addition, Jiang et al. [

12] reviewed studies indicating that glycerol is the most effective plasticizer for GG films produced using the solvent casting method.

As the glycerol content increased, there was a consistent decrease in both the maximum tensile strength and Young′s modulus values, along with a significant increase in elongation at break. This trend can be attributed to glycerol's role in reducing the strong intramolecular forces among polysaccharide chains while also promoting the formation of hydrogen bonds between glycerol and polysaccharide molecules. The reduction in tensile strength of plasticized polysaccharide films can be attributed to the diminished hydrogen bonds among the polysaccharide chains [

48]. This adaptability enables the production of thermo-compressed GG films that satisfy a wide variety of mechanical property and performance requirements. Optimizing the content of glycerol can improve the effectiveness of GG films in different packaging applications.

Figure 6.

Selected tensile curves of glycerol-plasticized GG films with varying glycerol content.

Figure 6.

Selected tensile curves of glycerol-plasticized GG films with varying glycerol content.

Table 2.

Tensile properties of glycerol-plasticized GG films.

Table 2.

Tensile properties of glycerol-plasticized GG films.

Glycerol content

(wt%)

|

Maximum tensile strength (MPa) |

Elongation at break (%) |

Young's modulus

(MPa)

|

-

15

30

45 |

40.6 ± 2.5 a

11.2 ± 0.8 b

8.0 ± 0.9 c

3.9 ± 0.3 d

|

3.4 ± 0.5 a

34.8 ± 4.2 b

42.2 ± 5.1 c

56.8 ± 4.8 d

|

988.2 ± 15.6 a

29.9 ± 4.5 b

8.6 ± 2.2 c

7.7 ± 1.8 c

|

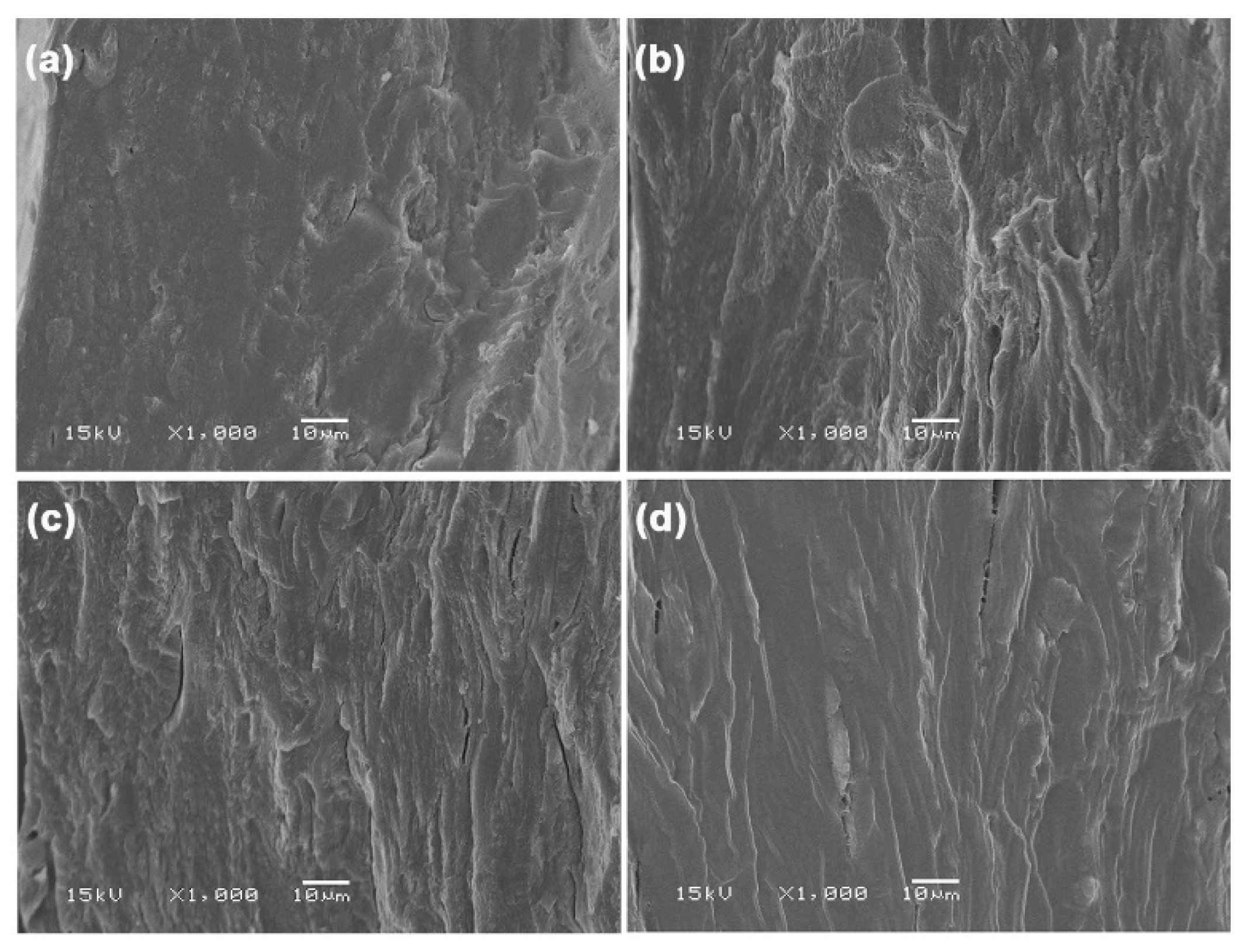

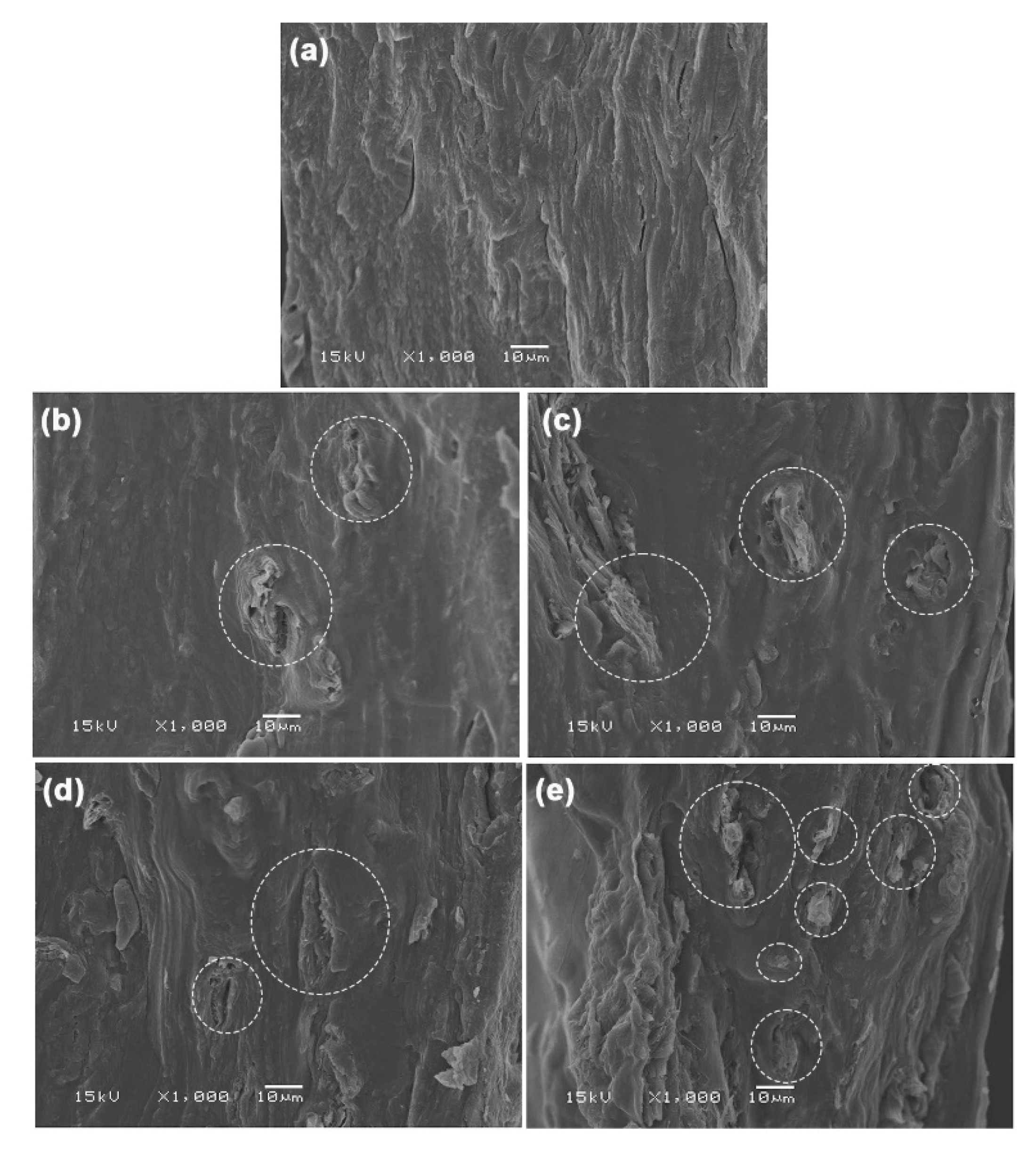

3.1.5. Phase Morphology of Glycerol-Plasticized GG Films

The phase morphology of the plasticized GG films was examined using SEM images of their cryogenically fractured surfaces, as illustrated in

Figure 7. The absence of visible GG particles in these film matrices indicates that the kneading and rolling process used in this work effectively plasticizes the GG particles. The pure GG film exhibits the smoothest surface texture, suggesting that it is the most brittle, which aligns with the previously mentioned tensile results. The lack of sufficient plasticizer distribution, crucial for enhancing the material's flexibility, may be the cause of this brittleness. The observed morphology of the fractured surface is directly linked to the mechanical properties, emphasizing the relationship between the film's structure and its performance. The fractured surface texture of the plasticized GG films appears rougher, suggesting that they possess greater flexibility compared to pure GG film. The observed rough cross-section structures may be due to insufficient interfacial adhesion between the GG film matrix and glycerol plasticizer, leading to weak forces during the tensile test and a subsequent decrease in tensile strength and increase in elongation at break [

48].

Additionally, we observed that the incorporation of 45% glycerol in

Figure 7(d) led to greater homogeneity compared to the 15% and 30% glycerol concentrations shown in

Figures 7(b) and 7(c), respectively. A similar observation indicated that the cross-section of biopolymer films with higher glycerol content demonstrated increased homogeneity [

49]. The findings suggested that films with higher glycerol content displayed greater homogeneity compared to those with lower glycerol content.

Figure 7.

SEM images of cryogenically fractured surfaces of (a) pure GG film and glycerol-plasticized GG films with glycerol contents of (b) 15 wt%, (c) 30 wt%, and (d) 45 wt%.

Figure 7.

SEM images of cryogenically fractured surfaces of (a) pure GG film and glycerol-plasticized GG films with glycerol contents of (b) 15 wt%, (c) 30 wt%, and (d) 45 wt%.

3.1.6. Moisture Content and Film Opacity of Glycerol-Plasticized GG Films

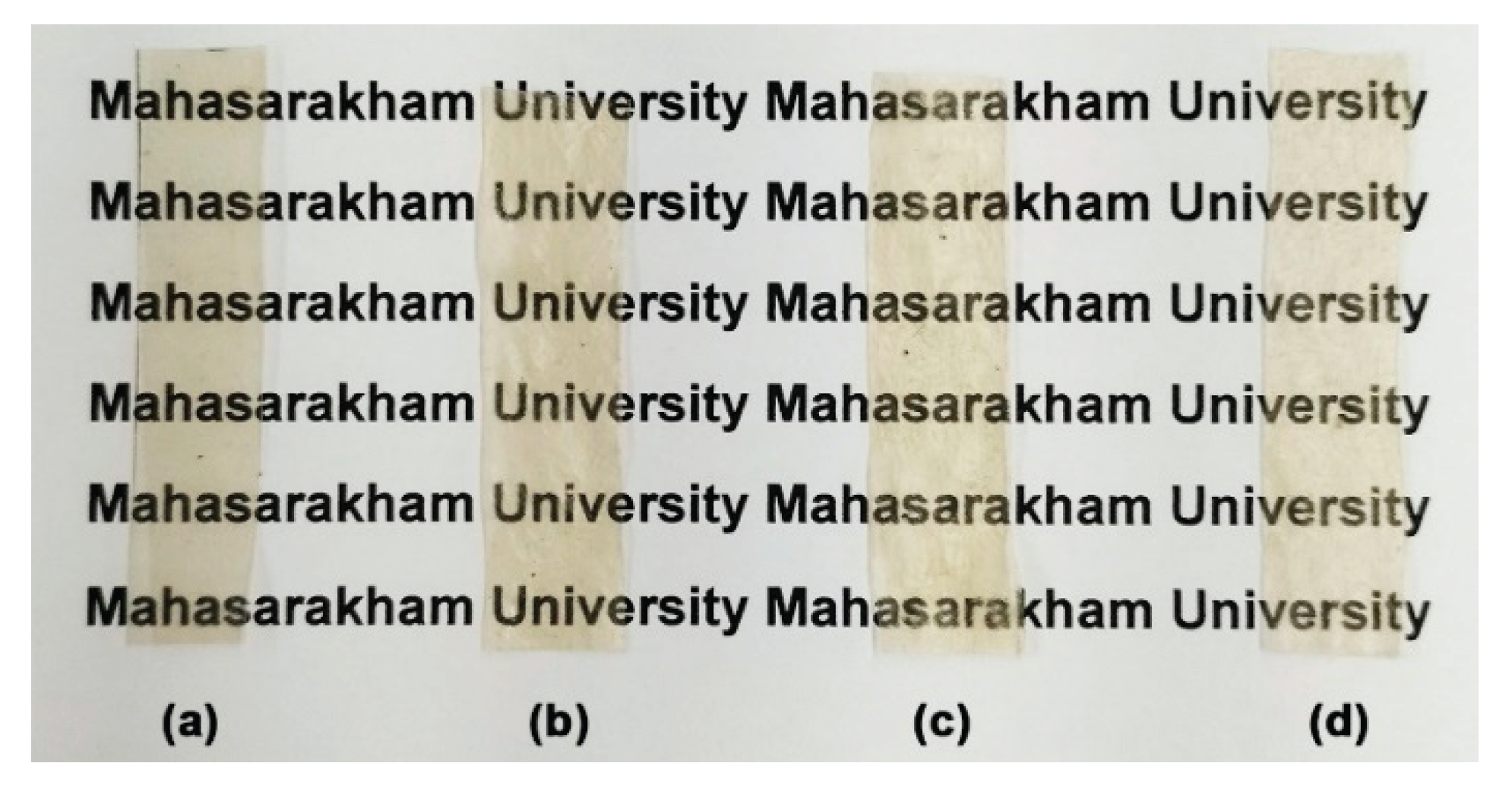

Table 3 demonstrates the influence of glycerol content on the thickness, moisture content, and opacity of GG films. All films exhibited thicknesses between 0.19 and 0.21 mm, with opacity values ranging from 1.67 to 1.71 mm⁻¹. The incorporation of glycerol did not influence the thickness and opacity of GG films. The moisture content of GG films significantly increased as the glycerol content rose, which is attributed to glycerol's highly hydrophilic nature. Various hydrocolloid films also demonstrated this behavior [50−52].

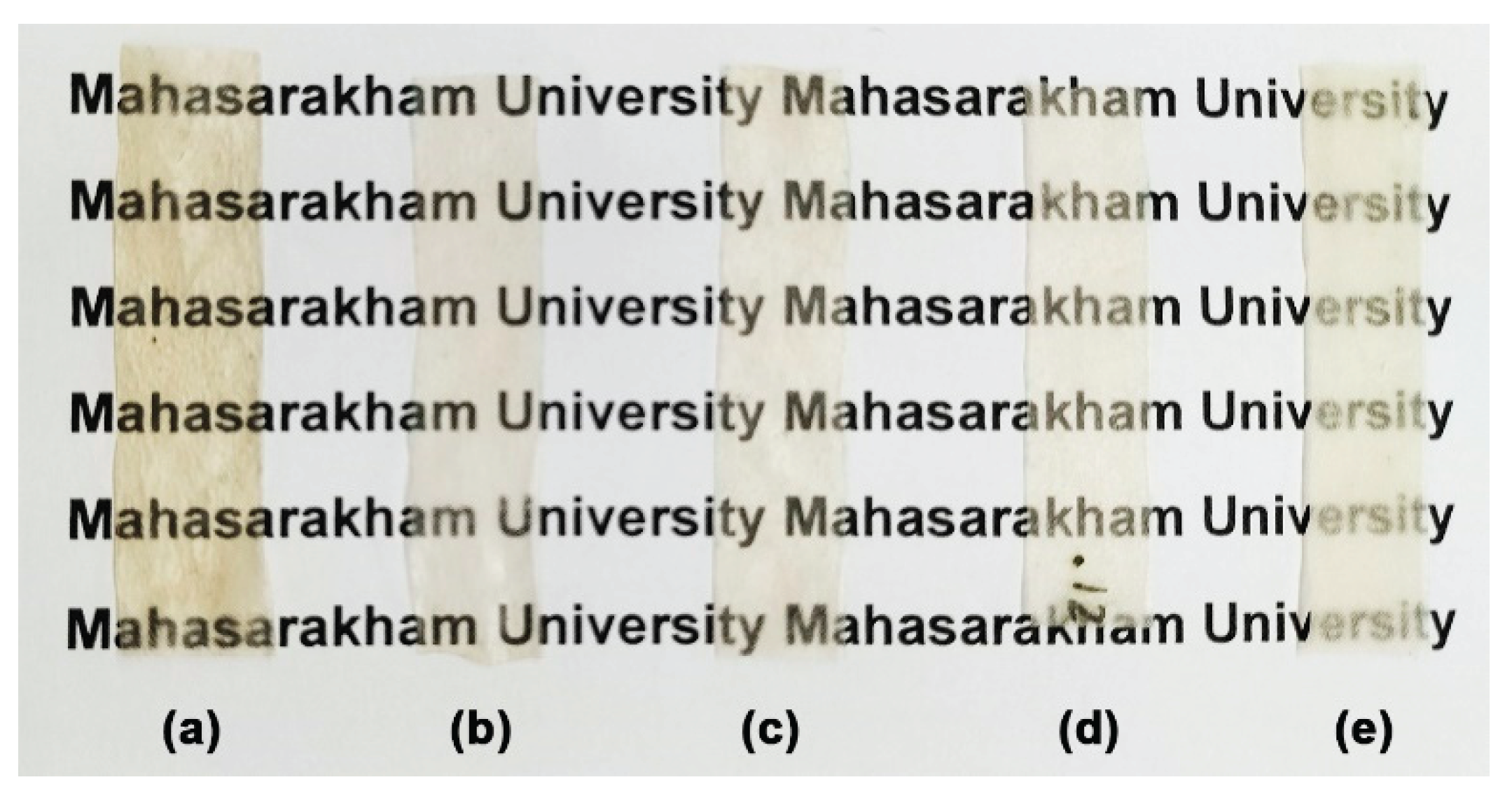

Figure 8 displays the characteristics of pure GG film alongside those that have been plasticized with glycerol. All films display transparency, providing a clear view of the characters beneath them.

3.2. Effect of MCC on Properties of Plasticized GG Films

3.2.1. FTIR Analysis of GG/MCC Films

The ATR-FTIR spectrum of MCC in

Figure S1(b) displays several characteristic bands. It shows a broad band at 3329 cm⁻¹ corresponding to O−H stretching vibrations, a band at 2886 cm⁻¹ associated with C−H stretching vibrations, and a band at 1426 cm⁻¹ indicative of intermolecular hydrogen bonding at C6 of the aromatic ring groups. Additionally, there is a band at 1162 cm⁻¹ related to C−O−C stretching vibrations of the

β-1,4-glycosidic linkage [

53]. A band at 1076 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the deformation of the glucopyranose ring [

54]. Furthermore, bands at 1035 and 1030 cm⁻¹ are attributed to C−O stretching vibrations of cellulose [

55], while a band at 895 cm⁻¹ is associated with the

β-1,4-glycosidic linkage [

56].

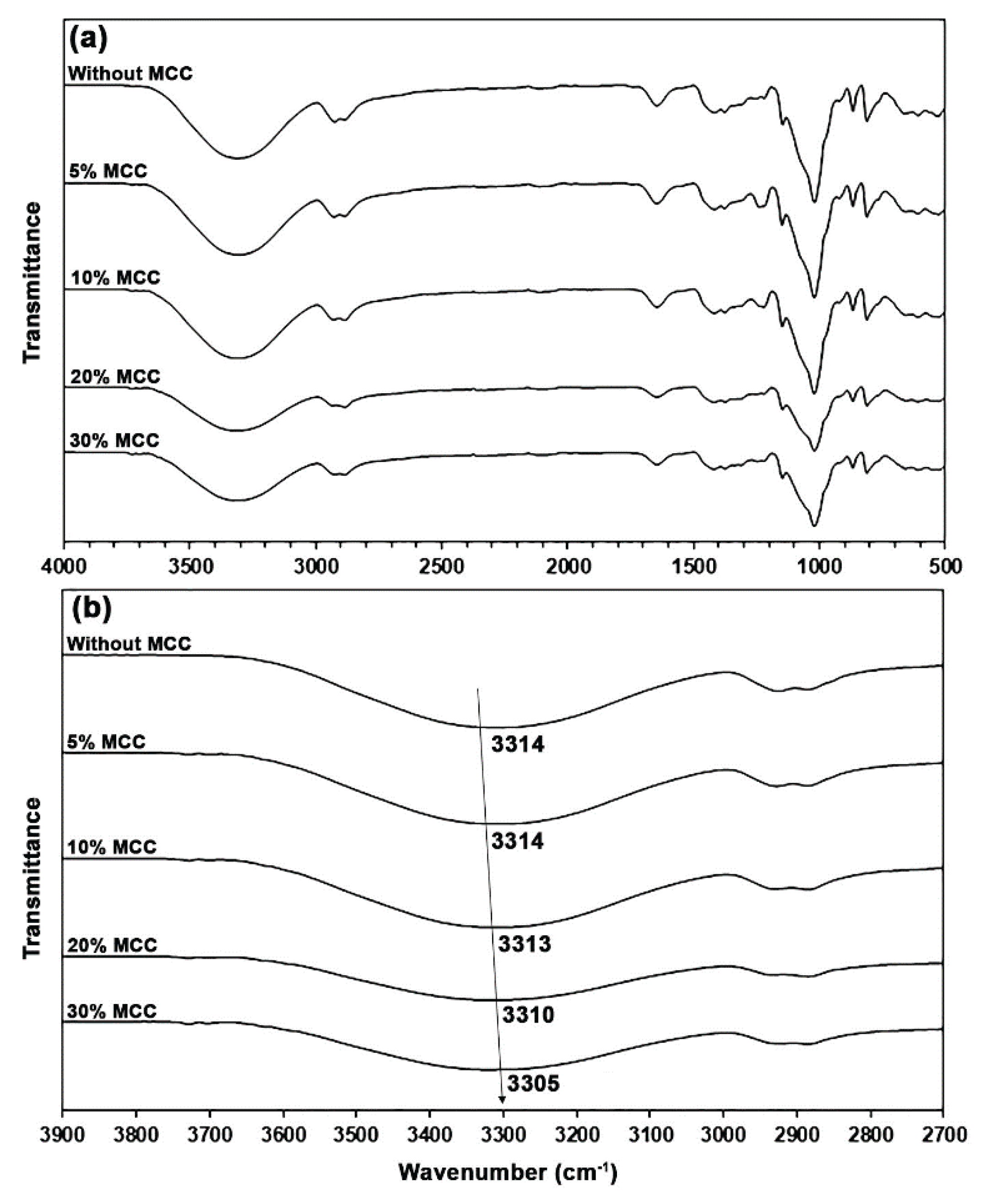

In

Figure 9(a), the ATR-FTIR spectra of glycerol-plasticized GG films with MCC show a pattern similar to that of the glycerol-plasticized GG film without MCC. In

Figure 9(b), the band at 3314 cm⁻¹ shifted to lower wavenumbers upon incorporating MCC, which corresponds to the O−H stretching vibration of a 30% glycerol-plasticized GG film. The observed values were 3314, 3313, 3310, and 3305 cm⁻¹ for 5, 10, 20, and 30 wt% MCC, respectively. This shift indicates that hydrogen-bonding interactions among the hydroxyl groups of GG, absorbed water, glycerol, and MCC occurred within the film matrix [

34,

35]. Previously, Tian et al. [

57] reported a similar finding when they incorporated MCC into the starch film.

3.2.2. Thermal Decomposition of GG/MCC Films

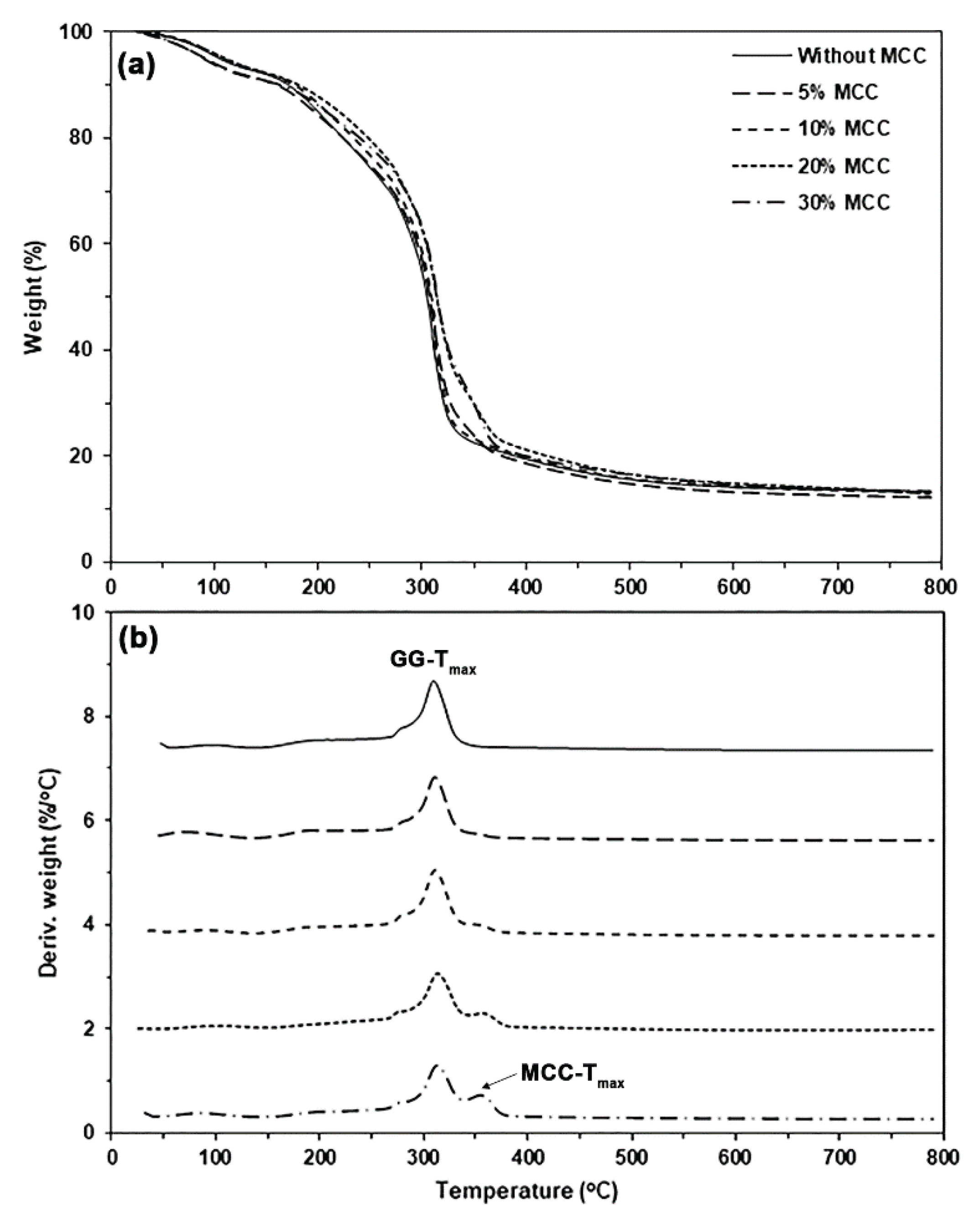

Figure 10(a,b) depict the TG and DTG thermograms, respectively, of MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films.

Table 4 summarizes the TGA results of the MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films. The char residue at 800°C of the MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films (12.9−13.3%) was lower than that of the film without MCC (14.6%). This difference arises because the char residue of MCC at 800°C is lower than that of GG (see

Figure S2). From

Figure 10(b), the

GG-Tmax peaks of the film samples appear to shift to higher temperatures with the addition of MCC. The

GG-Tmax peak of the glycerol-plasticized GG film without MCC was recorded at 310°C. In contrast, the MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films exhibited

GG-Tmax peaks ranging from 311 to 314°C. The addition of MCC appears to improve the thermal stability of the GG film matrix. As illustrated in

Figure S2, the higher

GG-Tmax of MCC (355°C) accounts for the observed difference. The enhanced thermal stability of MCC functions as a barrier, limiting heat transfer through the GG matrix [

58]. The temperature range of 355−358°C reveals the

Tmax peaks of MCC (

MCC-Tmax) in the GG films that are reinforced with MCC and plasticized with glycerol.

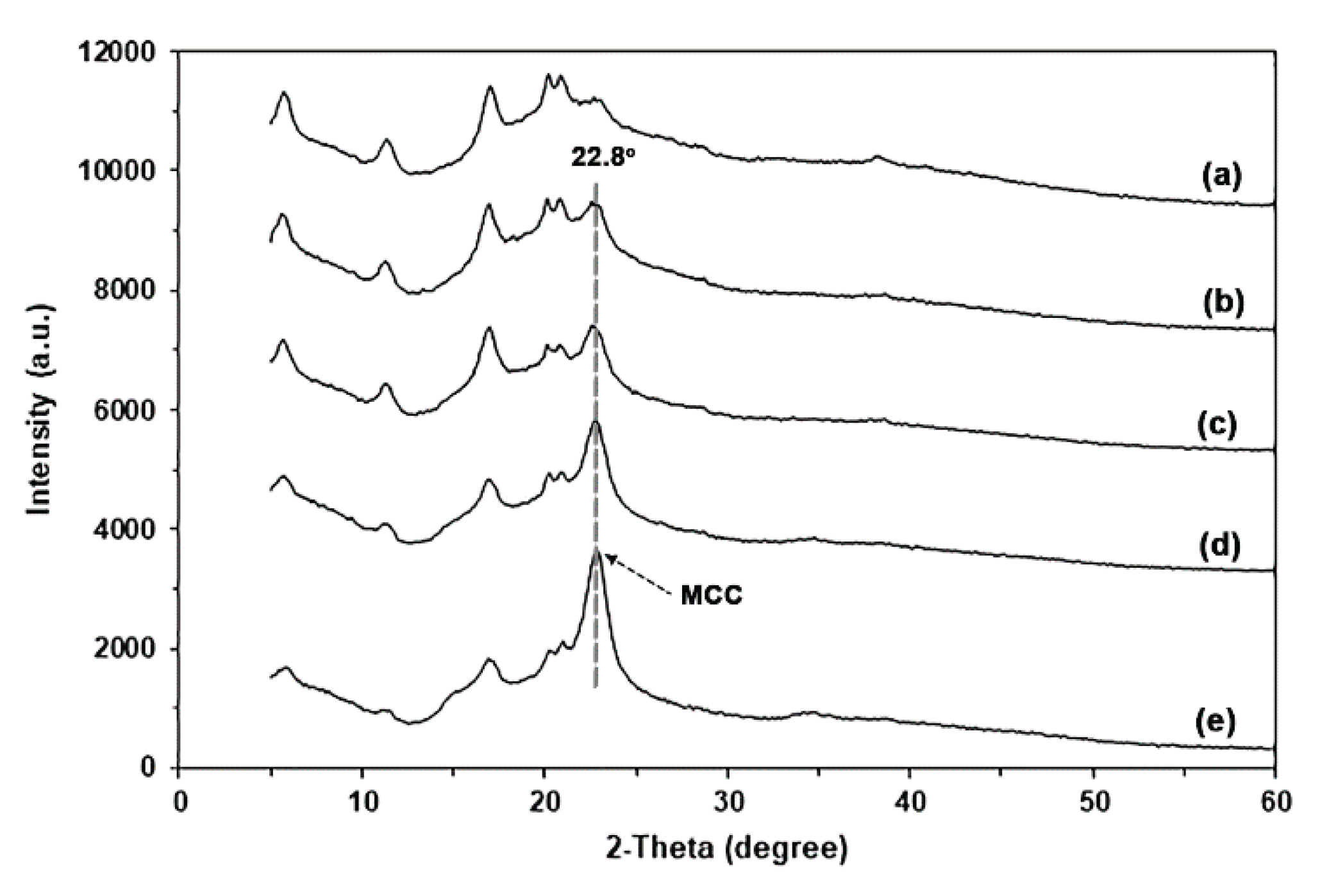

3.2.3. Crystalline Structures of GG/MCC Films

The XRD pattern of MCC, as shown in

Figure S3(b), exhibited peaks at 2θ = 15.2°, 22.8°, and 34.9°, which represent the crystalline characteristics of cellulose type I [59−61].

Figure 11 presents the XRD patterns of glycerol-plasticized GG films with and without MCC. The addition of MCC did not change the XRD patterns of the glycerol-plasticized GG film. The peak intensities of the characteristic features of the glycerol-plasticized GG film decrease with increasing MCC content. The XRD peak of MCC at 2θ = 22.8° demonstrated a steady increase in peak intensity, suggesting that GG films can be produced with different quantities of MCC.

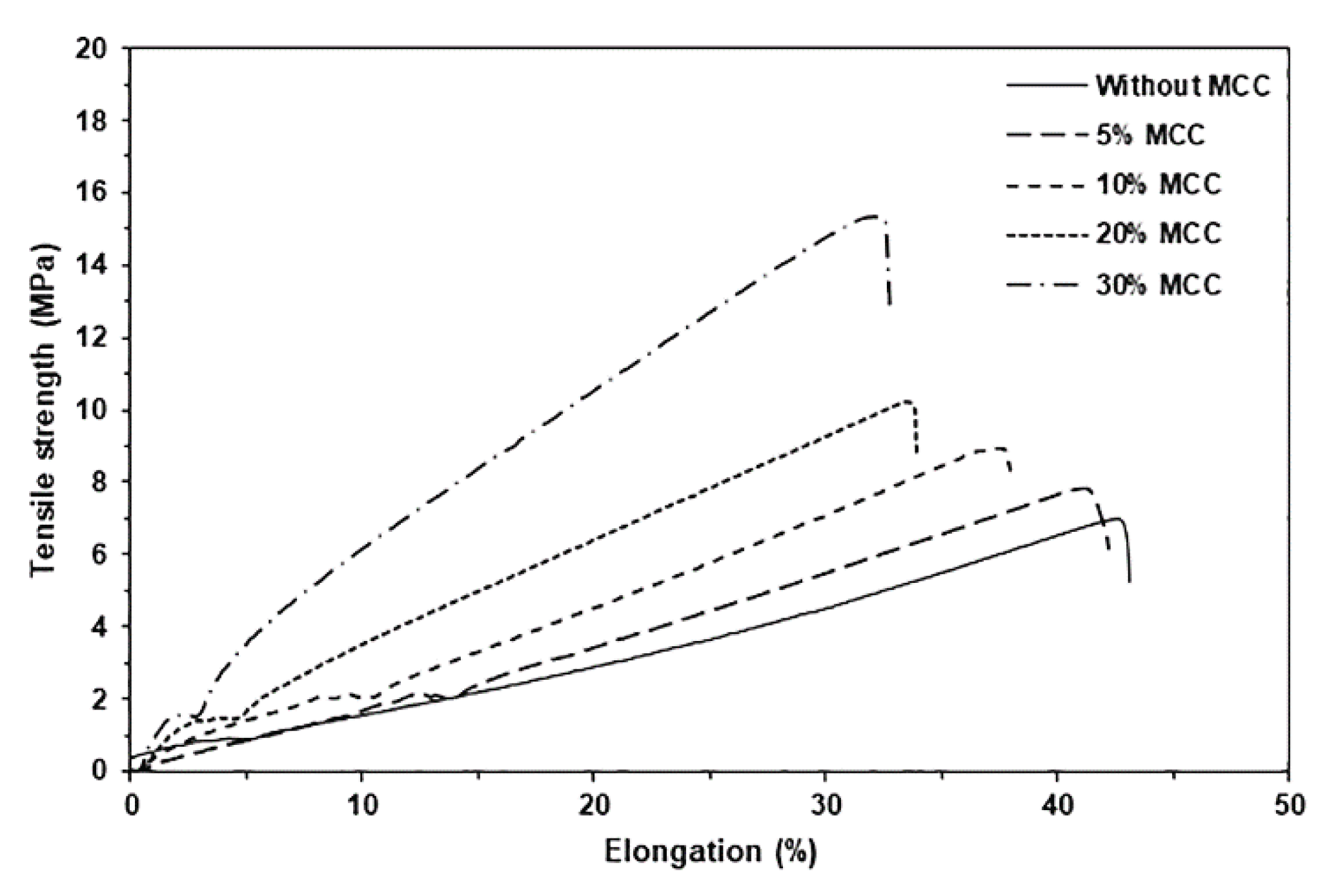

3.2.4. Tensile Properties of GG/MCC Films

Figure 12 presents the tensile curves for MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films, while

Table 5 provides a summary of the tensile results. The maximum tensile strength and Young′s modulus showed significant increases, while elongation at break exhibited a slight decrease as the MCC content rose. The tensile results demonstrated that the incorporation of MCC improved the reinforcement of the GG film matrix. Interactions between the GG and MCC may have facilitated effective stress transfer between the two materials, as described above in the FTIR analysis. A similar observation was made regarding the GG films produced using a solvent casting method, where enhanced mechanical properties were observed in GG films that incorporated MCC [

25]. Moreover, several hydrophilic biopolymer films, including starch [

23], thermoplastic starch (TPS) [

22,

24], and soy protein isolate [

62], have employed MCC as a cost-effective reinforcing filler. MCC possesses the capability to serve as an efficient reinforcing agent for GG film while simultaneously reducing production costs.

3.2.5. Phase Morphology of GG/MCC Films

Figure 13 displays SEM images of the cryo-fractured surfaces of MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films, alongside the glycerol-plasticized GG film for comparison. MCC particles were distinctly visible within the GG film matrices. Strong interfacial adhesion between the GG and MCC was evident. The high hydrophilic nature of both GG and MCC contributes to this observation. MCC has shown effective interfacial adhesion with various hydrophilic biopolymers, such as starch [

23], TPS [

24], and soy protein isolate [

62], in earlier studies. The SEM results supported the strong interactions between the GG and MCC, which were further indicated by the previous analyses, including FTIR, TGA, and tensile tests. The advantageous interfacial adhesion between them augmented heat transfer, thereby enhancing the thermal stability of the GG film matrix. Additionally, it facilitated stress transfer, which in turn improved both the tensile strength and Young′s modulus of the GG film matrix.

3.2.6. Moisture Content and Film Opacity of GG/MCC Films

Table 6 presents the thickness, moisture content, and opacity of films containing varying amounts of MCC. The films became thicker as the amount of MCC in them went up. The addition of MCC may have increased the viscosity of the glycerol-plasticized GG, which could have led to reduced flow during the compression molding process. Rico et al. [

24] reported that the addition of MCC increases the viscosity of the TPS in its molten state. The moisture content of the films consistently diminished with the increase in MCC content. This trend is consistent with research indicating that adding MCC decreases the moisture absorption of the films. The MCC filler's higher degree of crystallinity contributes to this reduction [

24,

63]. The incorporation of additional MCC increased the opacity of the films.

Figure 14 shows the appearance of glycerol-plasticized GG film, comparing the version without MCC [

Figure 14(a)] to those with different MCC content levels [

Figure 14(b–e)]. As the amount of MCC increases, the film becomes increasingly opaque; however, the letters underneath the film remain visible. Packaging can use these films to maintain the visibility of product features.

4. Conclusions

The MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized guar gum (GG) films were successfully produced using a thermo-compression process. We conducted a detail investigation into the effects of glycerol and microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) on the properties of thermo-compressed GG films. The formation of hydrogen bonds among the components of the glycerol-plasticized GG films was indicated by a shift to lower wavenumbers in the hydroxyl stretching bands observed in the ATR-FTIR spectra. The thermal stability of the GG film matrix was observed to improve with increased glycerol content, as demonstrated by TGA analysis.

The addition of glycerol led to the crystallization of the GG film matrix, as demonstrated by XRD analysis. The tensile analysis revealed that glycerol-plasticized GG films displayed a reduction in tensile strength and Young′s modulus while also showing increased elongation at break when compared to glycerol-free GG films. This evidence suggests that glycerol acts as an effective plasticizer, enhancing the flexibility of the GG film. The moisture content in GG films was found to increase as the glycerol content increased. The addition of MCC to the glycerol-plasticized GG film created hydrogen bonds with the film matrix, which improved thermal stability and elevated the tensile strength of the GG film. However, this addition also resulted in a decrease in the elongation at break of the glycerol-plasticized GG film. The incorporation of MCC resulted in an increased thickness and opacity of the glycerol-plasticized GG film. However, this addition also led to a decrease in the moisture content of the GG film.

The findings of this research indicate that the mechanical properties, hydrophilicity, and opacity of GG films can be tailored for various packaging applications by adjusting the glycerol and MCC content. We anticipate that the research findings will facilitate the creation of biodegradable blends and composites from GG material using conventional melt processing techniques. In the future, systematic research will be conducted to investigate the barrier properties of thermo-compressed GG films, as well as to examine their biodegradation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S., Y.B.; Methodology, P.S., Y.B.; Investigation, P.S., J.J., Y.B.; Resources, P.S., Y.B.; Visualization, Y.B.; Writing–original draft, P.S., J.J., P.N., N.K., Y.B.; Writing–review & editing, P.S., J.J., P.N., N.K., Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Mahasarakham University. The APC was funded by Mahasarakham University. PS and YB is also grateful to the partially support provided by the Centre of Excellence for Innovation in Chemistry (PERCH-CIC), Office of the Higher Education Commission, Ministry of Education, Thailand.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Tripathi, N.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Durable polylactic acid (PLA)-based sustainable engineered blends and biocomposites: Recent developments, challenges, and opportunities. ACS Eng. Au 2021, 1, 7−38. [CrossRef]

- Andreeßen, C.; Steinbüchel, A. Recent developments in non-biodegradable biopolymers: Precursors, production processes, and future perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103(1), 143−157. [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.R.A.; Marques, C.S.; Arruda, T.R.; Teixeira, S.C.; de Oliveira, T.V. Biodegradation of polymers: Stages, measurement, standards and prospects. Macromol 2023, 3, 371–399. [CrossRef]

- Jariyasakoolroj, P.; Leelaphiwat, P.; Harnkarnsujarit, N. Advances in research and development of bioplastic for food packaging. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100(14), 5032−5045. [CrossRef]

- Kakadellis, S.; Harris, Z.M. Don’t scrap the waste: The need for broader system boundaries in bioplastic food packaging life cycle assessment-A critical review. J. Clean Prod. 2020, 274, 122831. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cornish, K.; Vodovotz, Y. Narrowing the gap for bioplastic use in food packaging: An update. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54(8), 4712−4732. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Gao, R.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, Q. Applications of biodegradable materials in food packaging: A review. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 91, 70−83. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, A.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Naushad, M.; Ghfar, A.A.; Mola, G.T.; Stadler, F.J. Guar gum and its composites as potential materials for diverse applications: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 199, 534−545. [CrossRef]

- Sharahi, M.; Bahrami, S.H.; Karimi, A. A comprehensive review on guar gum and its modified biopolymers: Their potential applications in tissue engineering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 347, 122739. [CrossRef]

- Saya, L.; Malik, V.; Singh, A.; Singh, S.; Gambhir, G.; Singh, W.R.; Chandra, R.; Hooda, S. Guar gum based nanocomposites: Role in water purification through efficient removal of dyes and metal ions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 261, 117851. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.M.A.; Abdel-Raouf, M.E. Applications of guar gum and its derivatives in petroleum industry: A review. Egypt J. Pet. 2018, 27(4), 1043−1050. [CrossRef]

- Maurizzi, E.; Bigi, F.; Volpelli, L.A.; Pulvirenti, A. Improving the post-harvest quality of fruits during storage through edible packaging based on guar gum and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 40, 101178. [CrossRef]

- Singha. T.; Tanwara, M.; Gupta, R.K. Carboxymethyl guar gum-based bioactive and biodegradable film for food packaging. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2024, 66(2), 202–215.

- Priyadarsini, P.; Biswal, M.; Gupta, S.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Development and characterization of ester modified endospermic guar gum/polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) blown film: Approach towards greener packaging. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 187(A), 115319. [CrossRef]

- Kirtil, E.; Aydogdu, A.; Svitova, T.; Radke, C.J. Assessment of the performance of several novel approaches to improve physical properties of guar gum based biopolymer films. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 29, 100687. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, J.; Ambolikar, R.S.; Gupta, S.; Variyar, P.S. Preparation and characterization of methylated guar gum based nano-composite films. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124(B), 107312. [CrossRef]

- Dehankar, H.B.; Mali, P.S.; Kumar, P. Edible composite films based on chitosan/guar gum with ZnONPs and roselle calyx extract for active food packaging. Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3(1), 100276. [CrossRef]

- Bal-Öztürk, A.; Torkay, G.; İdil, N.; Özkahraman, B.; Zehra Özbaş, Z. Gellan gum/guar gum films incorporated with honey as potential wound dressings. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 1211–1228. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, K.; Bhattacharjee, S.K.; Goud, V.V.; Katiyar, V. Effect of waste Dunaliella tertiolecta biomass ethanolic extract and turmeric essential oil on properties of guar gum-based active films. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 146(A), 109199. [CrossRef]

- Karthik, K.; Velumayil, R.; Perumal, S.N.; Venkatesan, E.P.; Reddy, D.S.K.; Annakodi, V.A.; Alwetaishi, M.; Prabhakar, S. Synthesis and characterization of Borassus flabellifer flower waste-generated cellulose fillers reinforced PMC composites for lightweight applications. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28389. [CrossRef]

- Yong, W.S.; Yeu, Y.L.; Chung, P.P.; Soon, K.H. Extraction and characterization of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) from durian rind for biocomposite application. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 6544–6575. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chang, P.R.; Yu, J. Properties of biodegradable thermoplastic pea starch/carboxymethyl cellulose and pea starch/microcrystalline cellulose composites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 72(3), 369−375. [CrossRef]

- Wittaya, T. Microcomposites of rice starch film reinforced with microcrystalline cellulose from palm pressed fiber. Int. Food Res. J. 2009, 16(4), 493−500.

- Rico, M.; Rodríguez-Llamazares, S.; Barral, L.; Bouza, R.; Montero, B. Processing and characterization of polyols plasticized-starch reinforced with microcrystalline cellulose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 149, 83−93. [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, R.K.; Tripathi, P.; Kumar, S.; Gaikwad, K.K. Enhanced heat sealability and barrier performance of guar gum/polyvinyl alcohol based on biocomposite film reinforced with micro-fibrillated cellulose for packaging application. Polym. Bull. 2025, 82, 3755–3783.

- Schmid, M.; Reichert, K.; Hammann, F. Stabler, storage time-dependent alteration of molecular interaction-property relationships of whey protein isolate-based films and coating. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 50, 4396–4404. [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Pollet, E.; Avérous, L. Properties of glycerol-plasticized alginate films obtained by thermo-mechanical mixing. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 63, 414−420. [CrossRef]

- Hasheminya, S.-M.; Mokarram, R.R.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Hamishekar, H.; Kafil, H.S.; Dehghannya, J. Development and characterization of biocomposite films made from kefiran, carboxymethyl cellulose and Satureja Khuzestanica essential oil. Food Chem. 2019, 289, 443−452. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Fan, F.; Chu, Z.; Fan, C.; Qin, Y. Barrier properties and characterizations of poly(lactic acid)/ZnO nanocomposites. Molecules 2020, 25(6), 1310. [CrossRef]

- Nandal, K.; Vaid, V.; Rahul; Saini, P.; Devanshi; Sharma, R.K.; Joshi, V.; Jindal, R.; Mittal, H. Synthesis and characterization of κ-carrageenan and guar gum-based hydrogels for controlled release fertilizers: Optimization, release kinetics, and agricultural impact. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 225, 120587. [CrossRef]

- Ananthi, P.; Hemkumar, K.; Pius, A. Development of MOF and Cleome Gynandra infused guar gum film: A high-performance antibacterial and antioxidant packaging solution for fruits shelf life extension. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2025, 49, 101522. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Shah, Y.A.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Alhadhrami, A.S.; Al Hashmi, D.S.H.; Jawad, M.; Dıblan, S.; Al Dawery, S.K.H.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Anwer, M.K.; Koca, E.; Aydemir, L.Y. Characterization of biodegradable films based on guar gum and calcium caseinate incorporated with clary sage oil: Rheological, physicochemical, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties. J. Agr. Food Res. 2024, 15, 100948. [CrossRef]

- Madhu, K.; Dhal, M.K.; Banerjee, A.; Katiyar, V.; Kumar, A.A. Melt-processed cast films of calcite reinforced starch/guar-gum biopolymer composites for packaging applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 2689−2708. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemlou, M.; Khodaiyan, F.; Oromiehie, A. Rheological and structural characterisation of film-forming solutions and biodegradable edible film made from kefiran as affected by various plasticizer types. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 49(4), 814−821. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, P. Silver nanoparticles embedded guar gum/ gelatin nanocomposite: Green synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity. Colloid Interfac. Sci. Comm. 2020, 35, 100242. [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, N. Physicochemical and antimicrobial properties of biodegradable films based on gelatin/guar gum incorporated with grape seed oil. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 1515–1525. [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Pollet, E.; Avérous, L. Innovative plasticized alginate obtained by thermo-mechanical mixing: Effect of different biobased polyols systems. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 669−676. [CrossRef]

- Palanichamy, P.; Venkatachalam, S.; Gupta, S. Tough, flexible and oil-resistant film from sonicated guar gum and cellulose nanofibers for food packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 40, 101189. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, S.; Liu, S.; Sun, Y.; Xu, H. A Contribution to improve barrier properties and reduce swelling ratio of κ-carrageenan film from the incorporation of guar gum or Locust bean gum. Polymers 2023, 15, 1751. [CrossRef]

- Raj, V.; Bajpai, A. Synthesis of hydrophobically modified guar gum film for packaging materials. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 29 Part 4, 1132−1142. [CrossRef]

- Buléon, A.; Colonna, P.; Planchot, V.; Ball, S. Starch granules: structure and biosynthesis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1998, 23(2), 85−112. [CrossRef]

- Todica, M.; Nagy, E.M.; Niculaescu, C.; Stan, O.; Cioica, N.; Pop, C.V. XRD investigation of some thermal degraded starch-based materials. J. Spectrosc. 2016, 2016, 9605312. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.G.A.; da Silva, M.A.; dos Santos, L.O.; Beppu, M.M. Natural-based plasticizers and biopolymer films: A review. Eur. Polym. J. 2011, 47, 254–263.

- Bergo, P.V.A.; Carvalho, R.A.; Sobral, P.J.A.; Santos, R.M.C.; Silva, F.B.R.; Prison, J.M.; Solorza-Feria, J.; Habitante, A.M.Q.M. Physical properties of edible films based on cassava starch as affected by the plasticizer concentration. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2002, 21, 85–89. [CrossRef]

- Laohakunjit, N.; Noomhorm, A. Effect of plasticizers on mechanical and barrier properties of rice starch film. Starch 2004, 56, 348–356. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, O.V.; Garcia, M.A.; Zaritzky, N.E. Film forming capacity of chemically modified corn starches. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 73, 573–581. [CrossRef]

- Talja, R.A.; Hele´n, H.; Ross, Y.H.; Jouppila, K. Effect of type and content of binary polyol mixtures on physical and mechanical properties of starch-based edible films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 71, 269–276.

- Tarique, J.; Sapuan, S.M.; Khalina, A. Effect of glycerol plasticizer loading on the physical, mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of arrowroot (Maranta arundinacea) starch biopolymers. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13900. [CrossRef]

- Rocha Plácido Moore, G.; Maria Martelli, S.; Gandolfo, C.; José do Amaral Sobral, P.; Borges Laurindo, J. Influence of the glycerol concentration on some physical properties of feather keratin films. Food Hydrocoll. 2006, 20, 975–982. [CrossRef]

- Saberi, B.; Vuong, Q.V.; Chockchaisawasdee, S.; Golding, J.B.; Scarlett, C.J.; Stathopoulos, C.E. Water sorption isotherm of pea starch edible films and prediction models. Foods 2015, 5(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Saberi, B.; Thakur, R.; Vuong, Q.V.; Chockchaisawasdee, S.; Golding, J.B.; Scarlett, C.J.; Stathopoulos, C.E. Optimization of physical and optical properties of biodegradable edible films based on pea starch and guar gum. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 86, 342−352. [CrossRef]

- Sanyang, M.L.; Sapuan, S.M.; Jawaid, M.; Ishak, M.R.; Sahari, J. Effect of plasticizer type and concentration on physical properties of biodegradable films based on sugar palm (Arenga pinnata) starch for food packaging. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 326–336. [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Xiong, Z.; Na, H.; Zhu, J. How does epoxidized soybean oil improve the toughness of microcrystalline cellulose filled polylactide acid composites? Compos. Sci. Technol. 2014, 90, 9−15. [CrossRef]

- Lertprapaporn, T.; Manuspiya, H.; Laobuthee, A. Dielectric improvement from novel polymeric hybrid films derived by polylactic acid/nanosilver coated microcrystalline cellulose. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5(3) Part 2, 9326−9335. [CrossRef]

- Othman, N.A.; Adam, F.; Yasin, N.H.M. Reinforced bioplastic film at different microcrystalline cellulose concentration. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 41 Part 1, 77−82. [CrossRef]

- Isıtan, A.; Pasquardini, L.; Bersani, M.; Gök, C.; Fioravanti, S.; Lunelli, L.; Çaglarer, E.; Koluman, A. Sustainable production of microcrystalline and nanocrystalline cellulose from textile waste using HCl and NaOH/urea treatment. Polymers 2025, 17, 48. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, M.; Wei, Y.J.; Cheng, F.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, P.X. High-performance starch films reinforced with microcrystalline cellulose made from Eucalyptus pulp via ball milling and mercerization. Starch 2019, 71(3−4), 1800218. [CrossRef]

- Rammak, T.; Boonsuk, P.; Kaewtatip, K. Mechanical and barrier properties of starch blend films enhanced with kaolin for application in food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 192, 1013−1020. [CrossRef]

- Fouad, H.; Kian, L.K.; Jawaid, M.; Alotaibi, M.D.; Alothman, O.Y.; Hashem, M. Characterization of microcrystalline cellulose isolated from Conocarpus fiber. Polymers 2020, 12(12), 2926. [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Ahmed, D.; Ahmad, N.; Qamar, M.T.; Alruwaili, N.K.; Bukhari, S.N.A. Extraction and characterization of microcrystalline cellulose from Lagenaria siceraria fruit pedicles. Polymers 2022, 14(9), 1867. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S.; Ji, N.; Li, D. Extraction process research and characterization of microcrystalline cellulose derived from bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis (Carrière) J. Houz.) fibers. Polymers 2025, 17, 1143.

- Wang, Z.; Sun, X.-X.; Lian, Z.-X.; Wang, X.-X.; Zhou, J.; Ma, Z.-S. The effects of ultrasonic/microwave assisted treatment on the properties of soy protein isolate/microcrystalline wheat-bran cellulose film. J. Food Eng. 2013, 114(2), 183−191. [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, A.; Singh, M.; Verma, G. Green nanocomposites based on thermoplastic starch and steam exploded cellulose nanofibrils from wheat straw. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 82, 337–345. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

SEM image of MCC.

Figure 1.

SEM image of MCC.

Figure 5.

XRD patterns of (a) pure GG film and glycerol-plasticized GG films with glycerol contents of (b) 15 wt%, (c) 30 wt%, and (d) 45 wt%.

Figure 5.

XRD patterns of (a) pure GG film and glycerol-plasticized GG films with glycerol contents of (b) 15 wt%, (c) 30 wt%, and (d) 45 wt%.

Figure 8.

Thermo-compressed films of (a) pure GG and glycerol-plasticized GG with glycerol contents of (b) 15 wt%, (c) 30 wt%, and (d) 45 wt%.

Figure 8.

Thermo-compressed films of (a) pure GG and glycerol-plasticized GG with glycerol contents of (b) 15 wt%, (c) 30 wt%, and (d) 45 wt%.

Figure 9.

(a) ATR-FTIR spectra and (b) expanded hydroxyl regions of MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films with varying MCC content. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Figure 9.

(a) ATR-FTIR spectra and (b) expanded hydroxyl regions of MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films with varying MCC content. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Figure 10.

(a) TG and (b) DTG thermograms of MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films with varying MCC content. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Figure 10.

(a) TG and (b) DTG thermograms of MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films with varying MCC content. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Figure 11.

XRD patterns of glycerol-plasticized GG films: (a) without MCC and with MCC contents of (b) 5 wt%, (c) 10 wt%, (d) 20 wt%, and (e) 30 wt%. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Figure 11.

XRD patterns of glycerol-plasticized GG films: (a) without MCC and with MCC contents of (b) 5 wt%, (c) 10 wt%, (d) 20 wt%, and (e) 30 wt%. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Figure 12.

Selected tensile curves for MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films with varying MCC content. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Figure 12.

Selected tensile curves for MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films with varying MCC content. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Figure 13.

SEM images of cryo-fractured surfaces of glycerol-plasticized GG films: (a) without MCC and with MCC contents of (b) 5 wt%, (c) 10 wt%, (d) 20 wt%, and (e) 30 wt%. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol. Some MCC particles are indicated in white circles.

Figure 13.

SEM images of cryo-fractured surfaces of glycerol-plasticized GG films: (a) without MCC and with MCC contents of (b) 5 wt%, (c) 10 wt%, (d) 20 wt%, and (e) 30 wt%. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol. Some MCC particles are indicated in white circles.

Figure 14.

Thermo-compressed films of glycerol-plasticized GG: (a) without MCC and with MCC contents of (b) 5 wt%, (c) 10 wt%, (d) 20 wt%, and (e) 30 wt%. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Figure 14.

Thermo-compressed films of glycerol-plasticized GG: (a) without MCC and with MCC contents of (b) 5 wt%, (c) 10 wt%, (d) 20 wt%, and (e) 30 wt%. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Table 3.

Film thickness, moisture content, and film opacity of glycerol-plasticized GG films.

Table 3.

Film thickness, moisture content, and film opacity of glycerol-plasticized GG films.

Glycerol content

(wt%)

|

Film thickness

(mm)

|

Moisture content

(%)

|

Film opacity

(mm-1)

|

-

15

30

45 |

0.19 ± 0.06 a

0.20 ± 0.05 a

0.21 ± 0.06 a

0.19 ± 0.08 a

|

10.2 ± 0.2 a

13.1 ± 0.4 a

26.1 ± 0.6 b

41.8 ± 0.5 c

|

1.67 ± 0.09 a

1.71 ± 0.08 a

1.70 ± 0.10 a

1.68 ± 0.12 a

|

Table 4.

TGA results of MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Table 4.

TGA results of MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Glycerol content

(wt%)

|

Char residue

at 800°C (%)

|

GG-Tmax

(°C)

|

MCC-Tmax

(°C)

|

-

5

10

20

30 |

14.6

12.9

13.1

13.3

13.2 |

310

311

311

314

314 |

-

-

355

358

358 |

Table 5.

Tensile properties of MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Table 5.

Tensile properties of MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

MCC content

(wt%)

|

Maximum tensile strength (MPa) |

Elongation at break (%) |

Young's modulus

(MPa)

|

-

5

10

20

30 |

8.0 ± 0.9 a

8.8 ± 0.5 ab

9.9 ± 1.2 bc

10.8 ± 0.9 c

15.9 ± 1.5 d

|

42.2 ± 5.1 c

41.6 ± 3.5 bc

38.9 ± 2.6 b

33.0 ± 2.5 a

31.8 ± 1.7 a

|

8.6 ± 2.2 a

16.9 ± 1.8 b

26.3 ± 2.6 c

29.9 ± 2.4 c

67.1 ± 4.5 d

|

Table 6.

Film thickness, opacity, and moisture content of MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

Table 6.

Film thickness, opacity, and moisture content of MCC-reinforced and glycerol-plasticized GG films. All films contain 30 wt% glycerol.

MCC content

(wt%)

|

Film thickness

(mm)

|

Moisture content

(%)

|

Film opacity

(mm-1)

|

-

5

10

20

30 |

0.21 ± 0.06 a

0.34 ± 0.11 ab

0.43 ± 0.08 b

0.62 ± 0.10 c

0.83 ± 0.12 d

|

26.1 ± 0.6 c

11.5 ± 1.2 b

10.1 ± 0.8 b

8.4 ± 0.9 a

8.1 ± 0.8 a

|

1.70 ± 0.10 a

2.58 ± 0.11 b

3.04 ± 0.08 c

4.40 ± 0.06 d

5.07 ± 0.10 e

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).