Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

2.1.1. Film Preparation

2.1.2. Film Heat-Sealing

2.1.3. Proximate Analysis of Biomass

2.1.4. Antioxidant Activity Assays

Reducing Power

DPPH Scavenging Activity

Total Polyphenol Content

2.2. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

2.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetric Analysis (DSC)

2.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.7. Mechanical Tests

2.8. Water Vapor Permeability

Biodegradability

3. Results

3.1. Proximate Analysis of Biomass and Antioxidant Capacity

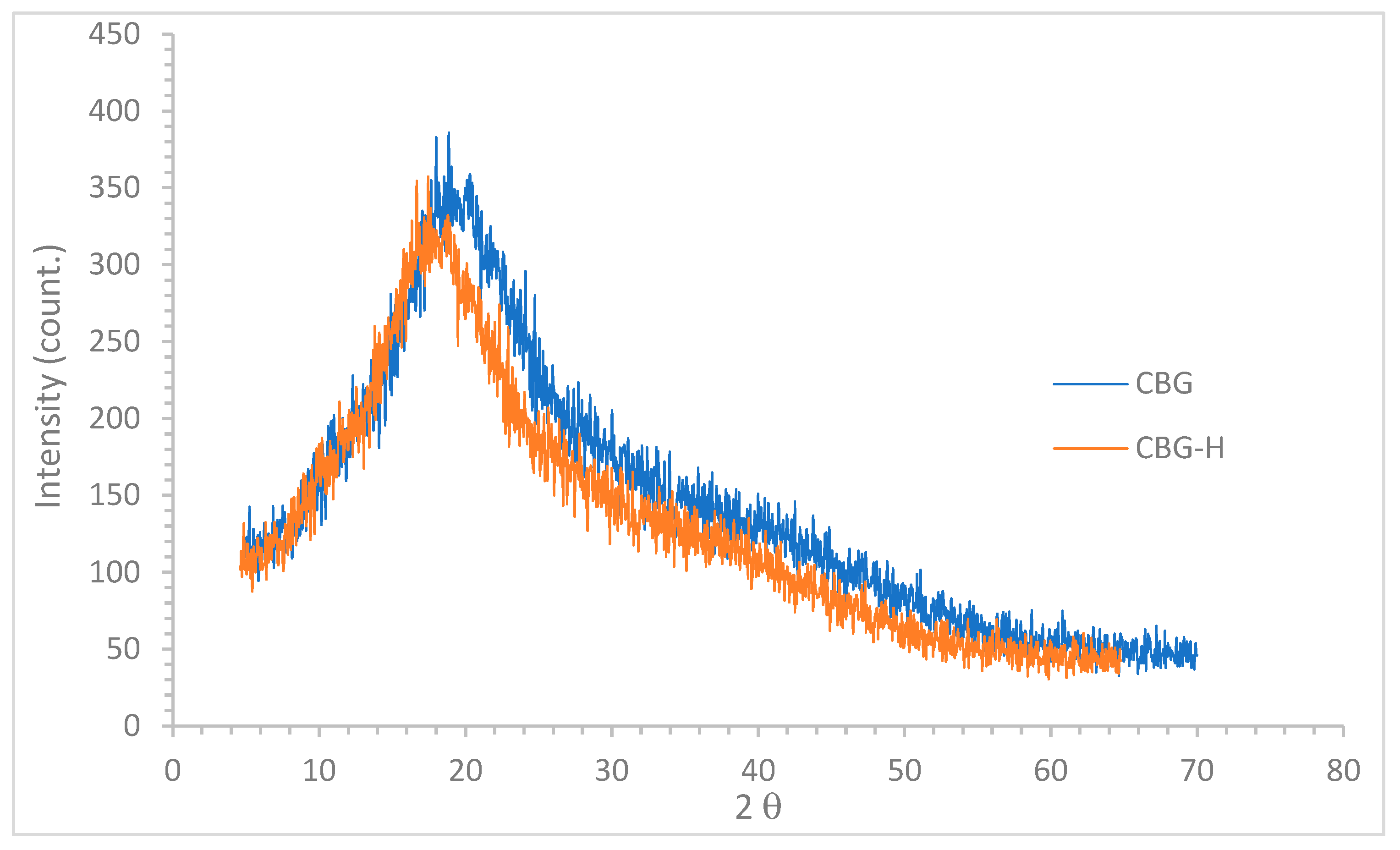

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

| Flour | 2θ | dspacing (nm) | ICr % |

| CBG | 18.15 ± 0.72 | 4.88 ± 0.97 | 34.16 ± 0.97 |

| CBG-H | 19.05 ± 0.84 | 4.66 ± 0.91 | 32.54 ± 0.89 |

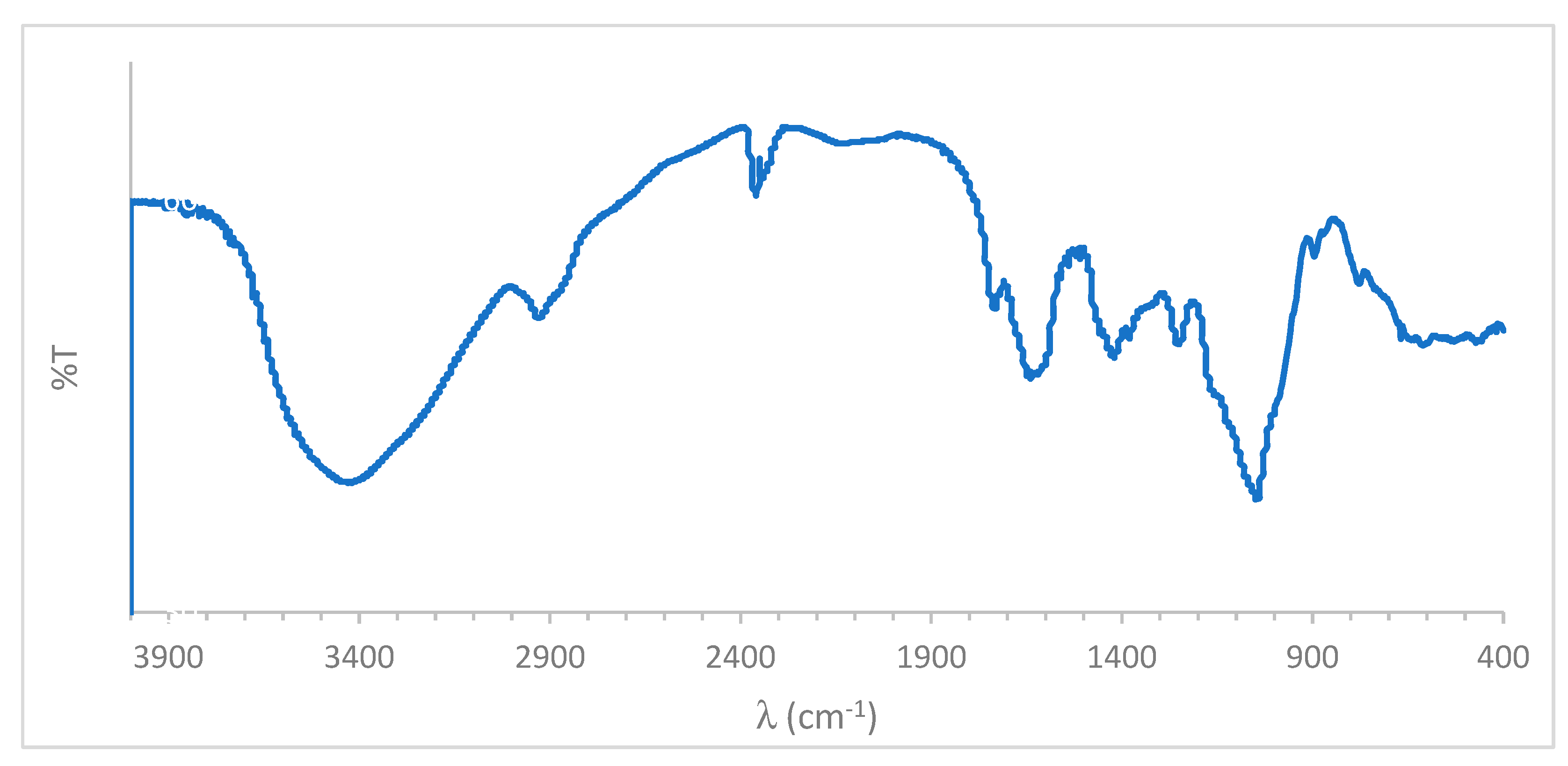

3.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

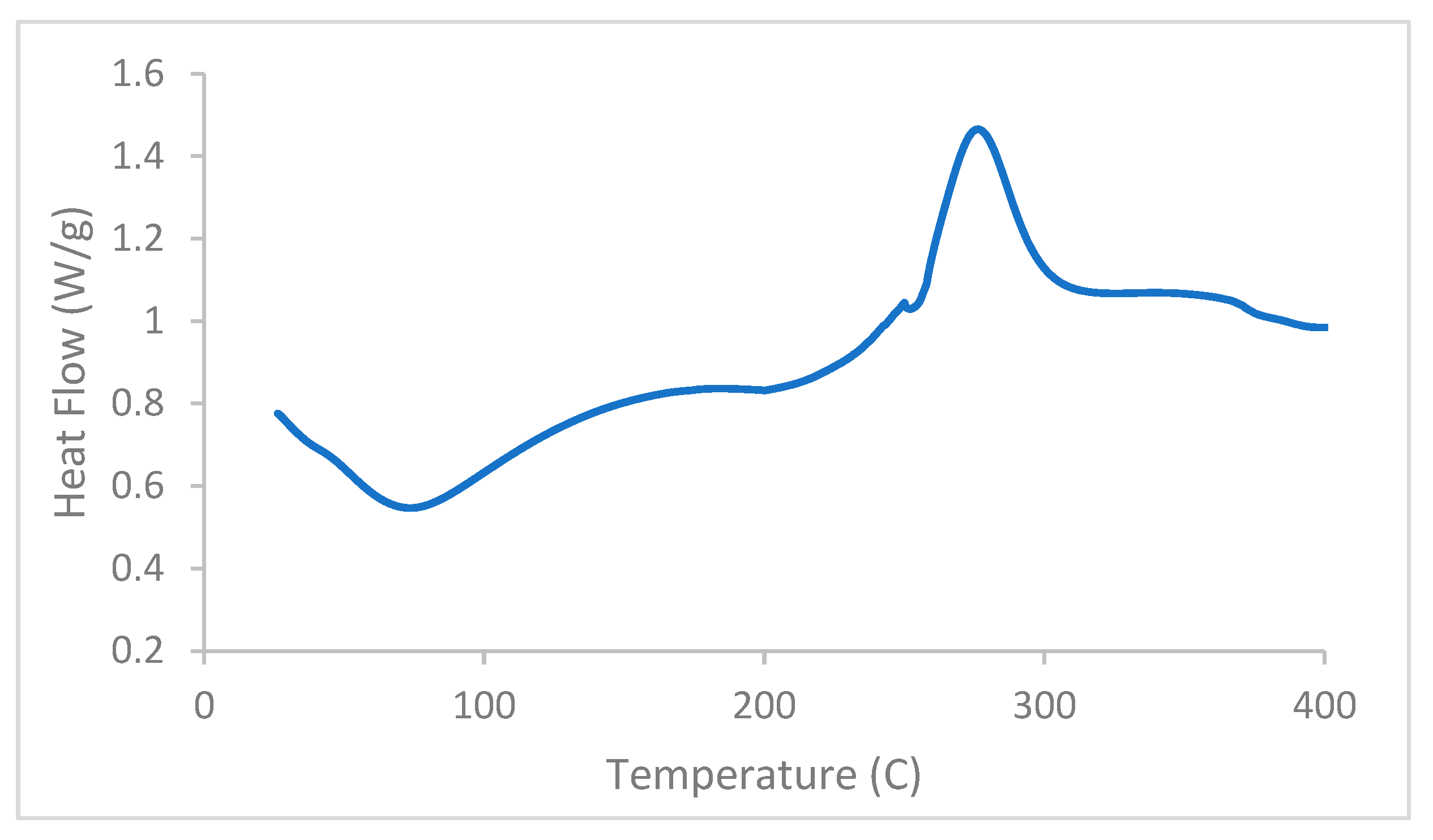

3.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

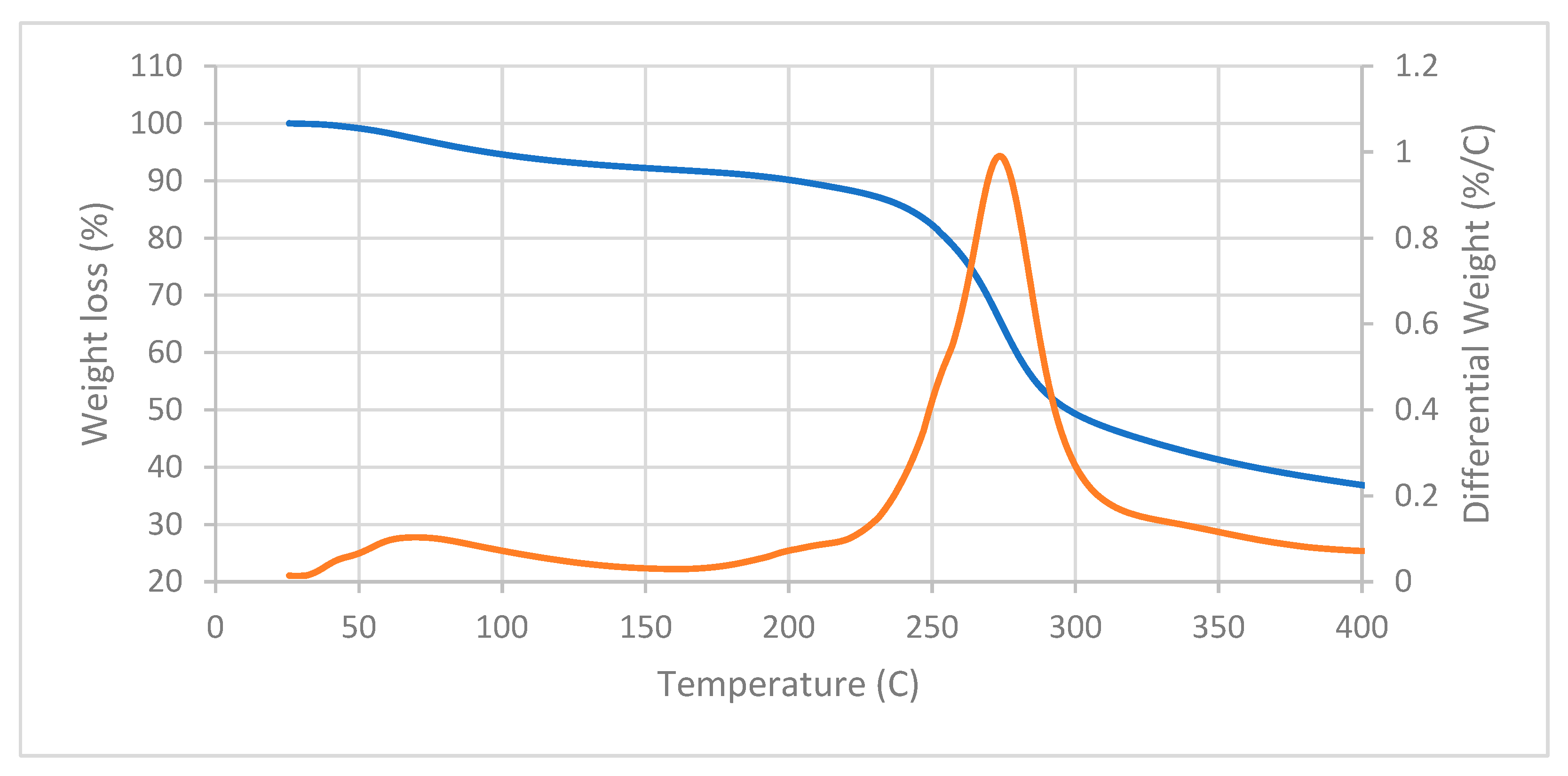

3.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA-DTGA)

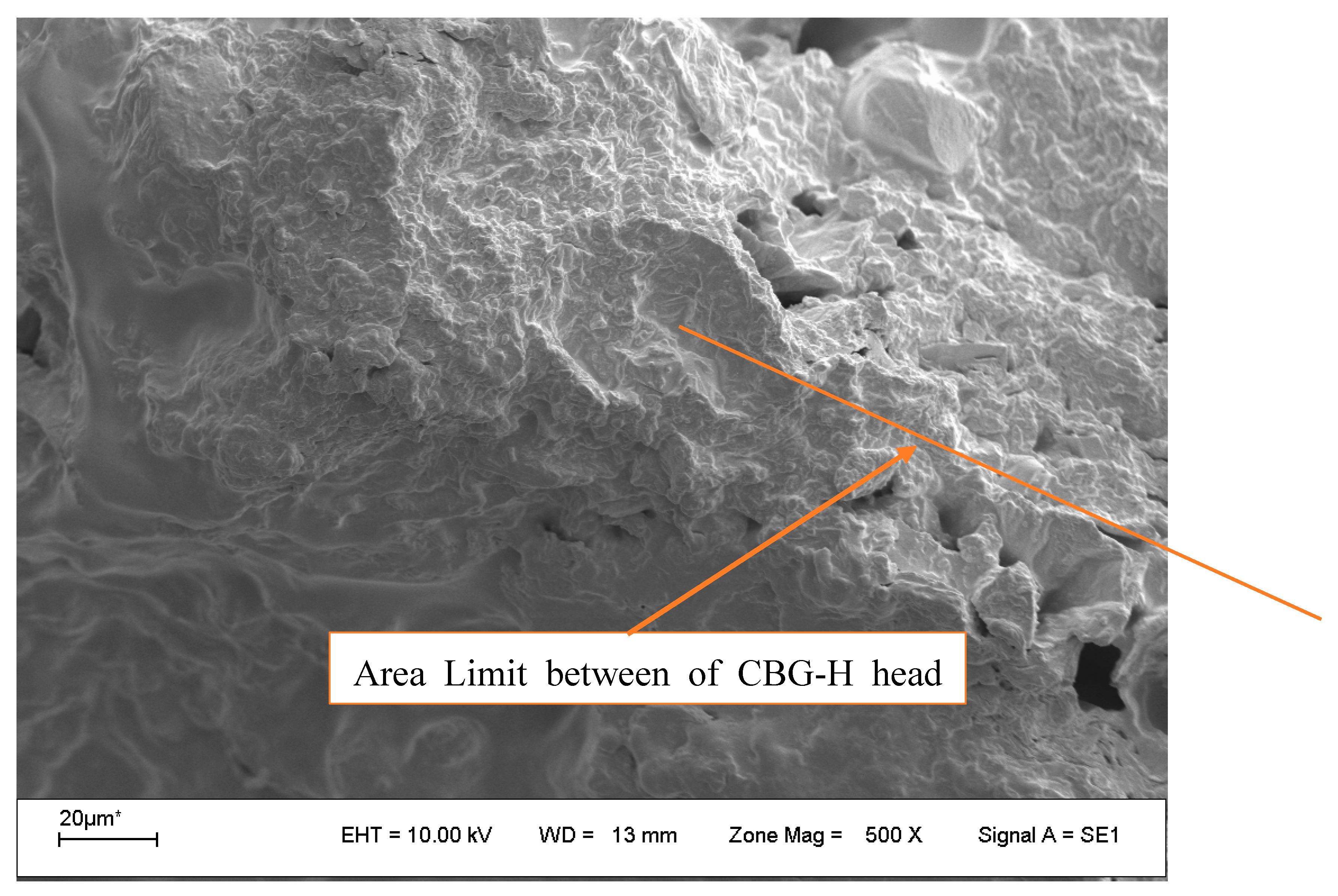

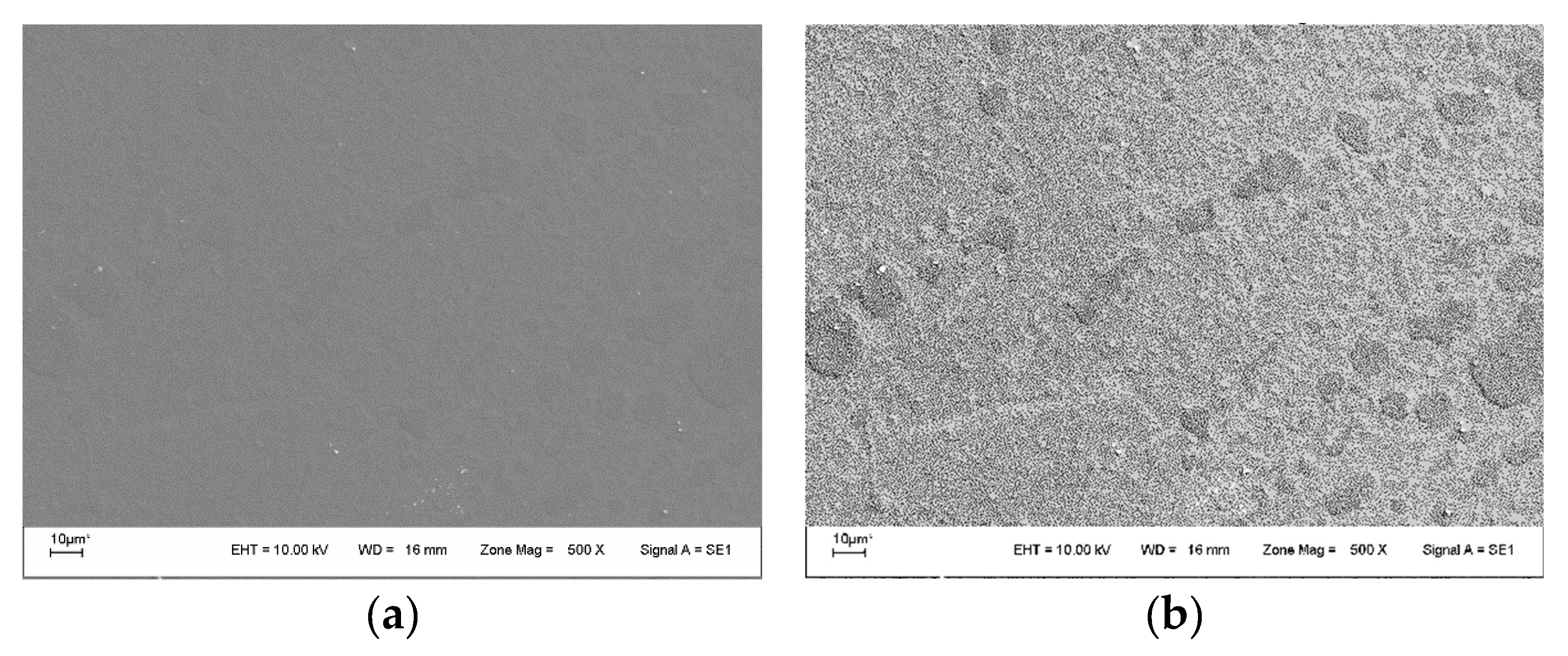

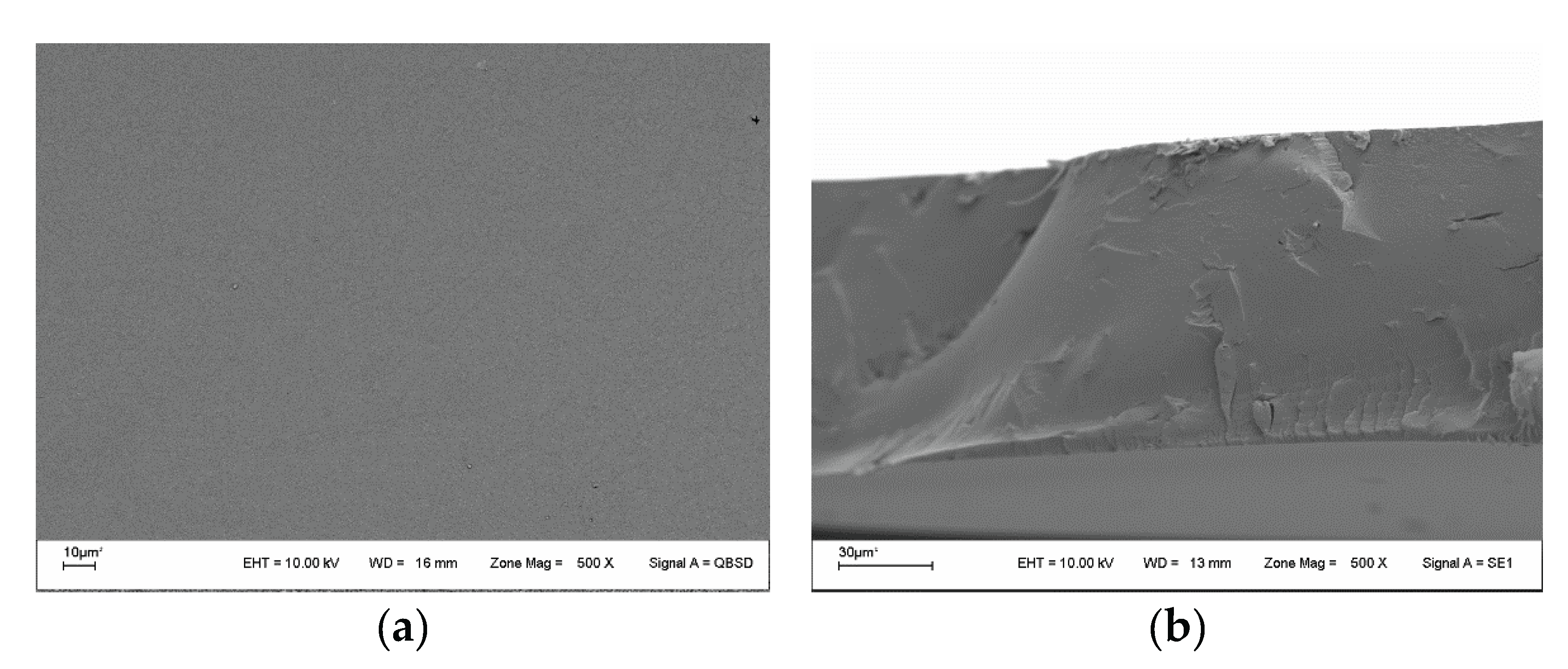

3.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

3.7. Water Sorption and Water Vapor Permeability

3.8. Mechanical Test and Heat-Sealing Capacity

| Film | e (µm) | εmax% | τmax (MPa) | E(MPa) |

| CBG | 190 | 5.11 | 4.48 | 132.0 |

| CBG-H | 307 | 11.09 | 3.36 | 96.8 |

| CBG-V | 305 | 12.13 | 4.58 | 159 |

Heat Sealing Capacity

3.9. Biodegradability

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Das, M., & Chowdhury, T. (2016). Heat sealing property of starch based self-supporting edible films. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 9, 64-68. [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, D., Álvarez, C., & Mullen, A. M. (2021). Biodegradable packaging materials from animal processing co-products and wastes: An overview. Polymers, 13(15), 2561. [CrossRef]

- Jeevahan, J. J., Chandrasekaran, M., Venkatesan, S. P., Sriram, V., Joseph, G. B., Mageshwaran, G., & Durairaj, R. B. (2020). Scaling up difficulties and commercial aspects of edible films for food packaging: A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 100, 210-222. [CrossRef]

- Dag, D., Jung, J., & Zhao, Y. (2023). Development and characterization of cinnamon essential oil incorporated active, printable and heat sealable cellulose nanofiber reinforced hydroxypropyl methylcellulose films. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 39, 101153. [CrossRef]

- Yi, C., Yuan, T., Xiao, H., Ren, H., & Zhai, H. (2023). Hydrophobic-modified cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs)/chitosan/zein coating for enhancing multi-barrier properties of heat-sealable food packaging materials. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 666, 131245. [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar, L., Ramesh, M., Bhuvaneswari, V., Balaji, D., & Deepa, C. (2023). Synthesis and thermomechanical properties of bioplastics and biocomposites: a systematic review. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 11(15), 3307-3337. [CrossRef]

- Kalina, S., Kapilan, R., Wickramasinghe, I., & Navaratne, S. B. (2024). Potential use of plant leaves and sheath as food packaging materials in tackling plastic pollution: A Review. Ceylon Journal of Science, 53(1). [CrossRef]

- Zink, J., Wyrobnik, T., Prinz, T., & Schmid, M. (2016). Physical, chemical and biochemical modifications of protein-based films and coatings: An extensive review. International journal of molecular sciences, 17(9), 1376. [CrossRef]

- Song, X., Zuo, G., & Chen, F. (2018). Effect of essential oil and surfactant on the physical and antimicrobial properties of corn and wheat starch films. International journal of biological macromolecules, 107, 1302-1309. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Huang, J., Zheng, X., Liu, S., Lu, K., Tang, K., & Liu, J. (2020). Heat sealable soluble soybean polysaccharide/gelatin blend edible films for food packaging applications. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 24, 100485. [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, K. K., Konwar, A., Borah, A., Saikia, A., Barman, P., & Hazarika, S. (2023). Cellulose nanofiber mediated natural dye based biodegradable bag with freshness indicator for packaging of meat and fish. Carbohydrate Polymers, 300, 120241. [CrossRef]

- Alves, Z., Ferreira, N. M., Ferreira, P., & Nunes, C. (2022). Design of heat sealable starch-chitosan bioplastics reinforced with reduced graphene oxide for active food packaging. Carbohydrate Polymers, 291, 119517. [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. S., Ock, S. Y., Park, G. D., Lee, I. W., Lee, M. H., & Park, H. J. (2020). Heat-sealing property of cassava starch film plasticized with glycerol and sorbitol. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 26, 100556. [CrossRef]

- Bamps, B., Buntinx, M., & Peeters, R. (2023). Seal materials in flexible plastic food packaging: A review. Packaging Technology and Science, 36(7), 507-532. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z., Ning, Y., Xu, J., Cheng, X., & Wang, L. (2024). Eco-friendly fabricating Tara pod extract-soy protein isolate film with antioxidant and heat-sealing properties for packaging beef tallow. Food Hydrocolloids, 153, 110041. [CrossRef]

- Garavito, J., Peña-Venegas, C. P., & Castellanos, D. A. (2024). Production of Starch-Based Flexible Food Packaging in Developing Countries: Analysis of the Processes, Challenges, and Requirements. Foods, 13(24), 4096. [CrossRef]

- Trianti, M., Mastora, A., Nikolaidou, E., Zorba, D., Rozou, A., Giannou, V., ... & Papadakis, S. E. (2024). Development and characterization of "Greek Salad" edible films. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 46, 101378. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., Chen, Z., Shu, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, W., Zhu, H., ... & Ma, Q. (2024). Apple pectin-based active films to preserve oil: Effects of naturally branched phytoglycogen-curcumin host. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 266, 131218. [CrossRef]

- Zehra, A., Amin, T., Wani, S. M., Sidiq, H., Bashir, I., Mustafa, S., ... & Showkat, S. (2024). Chitosan-Based Films. In Polysaccharide Based Films for Food Packaging: Fundamentals, Properties and Applications (pp. 121-144). Singapore: Springer Nature, Singapore.

- Rahman, S., Konwar, A., Gurumayam, S., Borah, J. C., & Chowdhury, D. (2025). Sodium Alginate-chitosan-starch based glue formulation for sealing biopolymer films. Next Materials, 7, 100507. [CrossRef]

- Uribarrena, M., Cabezudo, S., Núñez, R. N., Copello, G. J., de la Caba, K., & Guerrero, P. (2025). Development of smart films based on soy protein and cow horn dissolved in a deep eutectic solvent: Physicochemical and environmental assessment. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 291, 139045. [CrossRef]

- Nafchi, A. M., Nassiri, R., Sheibani, S., Ariffin, F., & Karim, A. A. (2013). Preparation and characterization of bionanocomposite films filled with nanorod-rich zinc oxide. Carbohydrate Polymers, 96(1), 233-239. [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Florencia. (2021). Tesis Doctoral. Materiales biodegradables con nanopartículas de plata con capacidad antimicrobiana para mejorar los procesos de conservación de alimentos. Universidad Nacional de la Plata, La Plata, Argentina.

- Bertuzzi, M. A., Slavutsky, A. M., & Armada, M. (2012). Physicochemical characterisation of the hydrocolloid from Brea tree (Cercidium praecox). International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 47(4), 768-775. [CrossRef]

- Bertuzzi, M. A., & Slavutsky, A. M. (2013). Formulation and Characterization of Film Based on Gum Exudates from Brea Tree (Cercidium praecox). Journal of Food Science and Engineering, 3 113-122.

- Slavutsky, A. M., Bertuzzi, M. A., Armada, M., García, M. G., & Ochoa, N. A. (2014). Preparation and characterization of montmorillonite/brea gum nanocomposites films. Food Hydrocolloids, 35, 270-278. [CrossRef]

- Slavutsky, A. M., & Bertuzzi, M. A. (2015). Thermodynamic study of water sorption and water barrier properties of nanocomposite films based on brea gum. Applied Clay Science, 108, 144-148. [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, J. P., Spotti, M. J., Piagentini, A. M., Milt, V. G., & Carrara, C. R. (2017). Development of edible films obtained from submicron emulsions based on whey protein concentrate, oil/beeswax and brea gum. Food Science and Technology International, 23(4), 371-381. [CrossRef]

- Slavutsky, A. M., Gamboni, J. E., & Bertuzzi, M. A. (2018). Formulation and characterization of bilayer films based on Brea gum and Pectin. Brazilian Journal of Food Technology, 21, e2017213. [CrossRef]

- Masuelli, M. A., Slatvustky, A., Ochoa, A., & Bertuzzi, M. A. (2018). Physicochemical Parameters for Brea Gum Exudate from Cercidium praecox Tree. Colloids and Interfaces, 2(4), 72. [CrossRef]

- Torres, M. F., Lazo Delgado, L., Filippa, M., Masuelli, M. A. (2020). Effect of Temperature on Mark-Houwink-Kuhn-Sakurada (MHKS) Parameters of Chañar Brea Gum Solutions. Journal of Polymer and Biopolymer Physics Chemistry, 8(1), 28-30.

- Torres, M. F., Lazo Delgado, L., D'Amelia, R., Filippa, M., Masuelli, M. (2021). Sol/gel transition temperature of chañar brea gum. Current Trends in Polymer Science, 20, 83-93.

- Becerra, F., Garro, M. F., Melo, G., & Masuelli, M. (2024). Preparation and Characterization of Lithraea molleoides Gum Flour and Its Blend Films. Processes, 12(11), 2506. [CrossRef]

- Rulli, M.M.; Villegas, L.B.; Barcia, C.S.; Colin, V.L. Bioconversion of sugarcane vinasse into fungal biomass protein and its potential use in fish farming. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106136. [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Hu, Z.; Fu, H.; Hu, M.; Xu, X.; Chen, J. Chemical analysis and antioxidant activity in vitro of β-D-glucan isolated from Dictyophora indusiate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2012, 51, 70-75. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Arora, S.; Singh, B. Antioxidant activity of the phenol rich fractions of leaves of Chukrasia tabularis A. Juss. Bioresour. Technol., 2008, 99, 7692-7698. [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Gillespie, K.M. Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Nat. Protoc., 2007, 2, 875-877. [CrossRef]

- Zanon, M.; Masuelli, M. Purification and characterization of alcayota gum. Biopolym. Res., 2018, 2, 105.

- Al Sagheer, F.A.; Al-Sughayer, M.A.; Muslim, S.; Elsabee, M.Z. Extraction and characterization of chitin and chitosan from marine sources in Arabian Gulf. Carbohydr. Polym., 2009, 77, 410-419. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, H.F.; Francisco, D.S.; Ferreira, A.P.; Cavalheiro, É.T. A new look towards the thermal decomposition of chitins and chitosans with different degrees of deacetylation by coupled TG-FTIR. Carbohydr. Polym., 2019, 225, 115232. [CrossRef]

- Zanon, M.; Masuelli, M.A. Alcayota gum films: Experimental reviews. J. Mater. Sci. Chem. Eng., 2018, 6, 11-58. [CrossRef]

- Masuelli, M. A., Lazo, L., Becerra, F., Torres, F., Illanes, C. O., Takara, A., Auad, M. L., Bercea, M. (2024). Physical and Chemical Properties of Pachycymbiola brasiliana Eggshells-From Application to Separative Processes. Processes, 12(4), 814. [CrossRef]

- Ruano, P., Delgado, L. L., Picco, S., Villegas, L., Tonelli, F., Merlo, M. E. A., ... & Masuelli, M. (2019). Extraction and Characterization of Pectins from Peels of Criolla Oranges (Citrus sinensis): Experimental Reviews. In Pectins-Extraction, Purification, Characterization and Applications. Martin Masuelli Ed. IntechOpen, London, UK.

- Lazo, L.; Melo, G.M.; Auad, M.L.; Filippa, M.; Masuelli, M.A. Synthesis and characterization of Chañar gum films. Colloids Interfaces, 2022, 6, 10. [CrossRef]

- Illanes, C.O.; Takara, E.A.; Masuelli, M.A.; Ochoa, N.A. pH-responsive gum tragacanth hydrogels for high methylene blue adsorption. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol., 2024, 99, 31-39. [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, N. D., Bains, A., Sridhar, K., Kaushik, R., Chawla, P., & Sharma, M. (2023). Recent advances in plant-based polysaccharide ternary complexes for biodegradable packaging. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 253, 126725. [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Ferreira, S.; Castillo, O.S.; Madera-Santana, J.T.; Mendoza-García, D.A.; Núñez-Colín, C.A.; Grijalva-Verdugo, C.; Villa-Lerma, A.G.; Morales-Vargas, A.T.; Rodríguez-Núñez, J.R. Production and physicochemical characterization of chitosan for the harvesting of wild microalgae consortia. Biotechnol. Rep., 2020, 28, e00554. [CrossRef]

- 48. 47. Chel-Guerrero, L.; Betancur-Ancona, D.; Aguilar-Vega, M.; Rodríguez-Canto, W. Films properties of QPM corn starch with Delonix regia seed galactomannan as an edible coating material. Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2024, 255, 128408. [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, M. K., Seidi, F., Jin, Y., Zarrintaj, P., Xiao, H., Esmaeili, A., ... & Saeb, M. R. (2021). Crystallization of polysaccharides. Polysaccharides: Properties and Applications, 283-300. [CrossRef]

- Luo, A. Luo, A., Hu, B., Feng, J., Lv, J., & Xie, S. (2021). Preparation, and physicochemical and biological evaluation of chitosan Arthrospira platensis polysaccharide active films for food packaging. Journal of Food Science, 86(3), 987-995. [CrossRef]

- Nahas, E. O., Furtado, G. F., Lopes, M. S., & Silva, E. K. (2025). From Emulsions to Films: The Role of Polysaccharide Matrices in Essential Oil Retention Within Active Packaging Films. Foods, 14(9), 1501. [CrossRef]

- Du, B., Jeepipalli, S. P., & Xu, B. (2022). Critical review on alterations in physiochemical properties and molecular structure of natural polysaccharides upon ultrasonication. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 90, 106170. [CrossRef]

- Demircan, B., McClements, D. J., & Velioglu, Y. S. (2025). Next-Generation Edible Packaging: Development of Water-Soluble, Oil-Resistant, and Antioxidant-Loaded Pouches for Use in Noodle Sauces. Foods, 14(6), 1061. [CrossRef]

- Bumbudsanpharoke, N., Harnkarnsujarit, N., Chongcharoenyanon, B., Kwon, S., & Ko, S. (2023). Enhanced properties of PBAT/TPS biopolymer blend with CuO nanoparticles for promising active packaging. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 37, 101072. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y., Rao, Z., Liu, Y., Zheng, X., Tang, K., & Liu, J. (2023). Soluble soybean polysaccharide/gelatin active edible films incorporated with curcumin for oil packaging. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 35, 101039. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, R., Abdullah, N., Din, R. H., & Tay, G. S. (2013). Producing novel sago starch based food packaging films by incorporating lignin isolated from oil palm black liquor waste. Journal of Food Engineering, 119(4), 707-713. [CrossRef]

- Sadegh-Hassani, F., & Nafchi, A. M. (2014). Preparation and characterization of bionanocomposite films based on potato starch/halloysite nanoclay. International journal of biological macromolecules, 67, 458-462. [CrossRef]

- Chhikara, S., & Kumar, D. (2022). Edible coating and edible film as food packaging material: A review. Journal of Packaging Technology and Research, 6(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. J., & Ustunol, Z. (2001). Thermal properties, heat sealability and seal attributes of whey protein isolate/lipid emulsion edible films. Journal of food science, 66(7), 985-990. [CrossRef]

- Nafchi, A. M. (2013). Mechanical, barrier, physicochemical, and heat seal properties of starch films filled with nanoparticles. Journal of Nano Research, 25, 90-100. [CrossRef]

- Shah, Y. A., Bhatia, S., Al-Harrasi, A., Oz, F., Khan, M. H., Roy, S., ... & Pratap-Singh, A. (2024). Thermal properties of biopolymer films: Insights for sustainable food packaging applications. Food Engineering Reviews, 16(4), 497-512. [CrossRef]

- Demircan, B., & Velioglu, Y. S. (2025). Revolutionizing single-use food packaging: a comprehensive review of heat-sealable, water-soluble, and edible pouches, sachets, bags, or packets. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 65(8), 1497-1517. [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y. (2023). Regenerated Cellulose Films with Heat Sealability and Improved Barrier Properties for Sustainable Food Packaging. McGill University, Montreal, Canada.

- Cho, S. W., Ullsten, H., Gällstedt, M., & Hedenqvist, M. S. (2007). Heat-sealing properties of compression-molded wheat gluten films. Journal of Biobased Materials and Bioenergy, 1(1), 56-63. [CrossRef]

- Rouhi, J., Mahmud, S., Naderi, N., Ooi, C. R., & Mahmood, M. R. (2013). Physical properties of fish gelatin-based bio-nanocomposite films incorporated with ZnO nanorods. Nanoscale research letters, 8, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F., Jiang, L., Wang, C., Li, S., Sun, D., Ma, Q., ... & Jiang, W. (2024). Flexibility, dissolvability, heat-sealability, and applicability improvement of pullulan-based composite edible films by blending with soluble soybean polysaccharide. Industrial Crops and Products, 215, 118693. [CrossRef]

- Roidoung, S., Sonyiam, S., & Fugthong, S. (2025). Development of heat sealable film from tapioca and potato starch for application in edible packaging. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 62(2), 389-395. [CrossRef]

- Aleksanyan, K. V. (2023). Polysaccharides for biodegradable packaging materials: Past, present, and future (Brief Review). Polymers, 15: 451. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Li, B., Li, C., Xu, Y., Luo, Y., Liang, D., & Huang, C. (2021). Comprehensive review of polysaccharide-based materials in edible packaging: A sustainable approach. Foods, 10(8), 1845. [CrossRef]

- López, O. V., Lecot, C. J., Zaritzky, N. E., & García, M. A. (2011). Biodegradable packages development from starch based heat sealable films. Journal of Food Engineering, 105(2), 254-263. [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y., Popovich, C., & Wang, Y. (2023). Heat sealable regenerated cellulose films enabled by zein coating for sustainable food packaging. Composites Part C: Open Access, 12, 100390. [CrossRef]

- Jongjun, Y., Pornprasert, P., & Prateepchanachai, S. (2024). Improvement of heat-sealing strength of chitosan-based composite films and product costs analysis in the production process. Journal of Applied Research on Science and Technology, 23(1), 251817-251817. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Li, M., Liu, Z., Li, R. A., & Cao, Y. (2024). Heat-sealable, transparent, and degradable arabinogalactan/polyvinyl alcohol films with UV-shielding, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 275, 133535. [CrossRef]

- Janik, W., Nowotarski, M., Shyntum, D. Y., Bana?, A., Krukiewicz, K., Kud?a, S., & Dudek, G. (2022). Antibacterial and biodegradable polysaccharide-based films for food packaging applications: Comparative study. Materials, 15(9), 3236. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A. R., Torres, C. A., Freitas, F., Reis, M. A., Alves, V. D., & Coelhoso, I. M. (2014). Biodegradable films produced from the bacterial polysaccharide FucoPol. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 71, 111-116. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S. S., Romani, V. P., da Silva Filipini, G., & G Martins, V. (2020). Chia seeds to develop new biodegradable polymers for food packaging: Properties and biodegradability. Polymer Engineering & Science, 60(9), 2214-2223. [CrossRef]

- Masuelli, M. A. & García, M. G. (2017). Biopackaging: Tara Gum Films. In Advances in Physicochemical Properties of Biopolymers. Part 2, pp. 876-898. Martin Masuelli & Denis Renard Eds. Bentham Publishing. Dubai, UEA.

- García, María Guadalupe, Masuelli, Martin A. (2022). Effect of Cross-Linking Agent on Mechanical and Permeation Properties of Criolla Orange Pectin". In Pectin-The New-Old Polysaccharides, Martin Masuelli Ed. INTECH, Rijeka, Croatia.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).