1. Introduction

Polymer-based packaging is widely used across various industries due to its relative ease of production, low cost, light weight, strength and performance characteristics. The main consumers of polymer packaging include manufacturers of electronic, agricultural, food, and pharmaceutical products [

1,

2].

Among polyolefin-based polymers, polyethylene (PE) is the most commonly used material. It has a high molecular weight structure and exhibits high chemical inertness to various aggressive conditions, which provides significant advantages over many other polymers. There are two main types of PE used in the food industry: low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) [

3].

Polymers are susceptible to degradation and, under the influence of external factors (physical, chemical, or environmental), can relatively quickly lose their strength, elasticity, and functional properties [

3,

4,

5]. In modern manufacturing, synthetic polymer materials used for packaging are rarely applied in their pure form; they are typically incorporated with mineral fillers, modifiers, and stabilizers [

6,

7,

8]. Due to the wide variety of polymer materials with different structures and properties, it is possible to obtain modified packaging that demonstrates improved and more stable characteristics compared to the base polymer. These materials can also offer targeted functional properties, remain compatible with standard processing equipment and require minimal changes to the production process [

9,

10,

11,

12]. However, it is important to consider that improper selection of modifiers, their concentrations, or processing conditions may compromise the safety of the final material [

13,

14]. Intermolecular interactions between the synthetic polymer matrix and inorganic fillers can affect the material’s properties at the microscopic level [

6,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Various mineral fillers are widely used to modify polymer films, including calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) [

17,

18,

19,

20], clay [

21], talc [

18,

22], silicon dioxide (SiO₂) [

23], and others.

Global consumption of calcium carbonate (chalk) in the polymer industry is estimated to exceed 10 million tons per year [

24]. The addition of CaCO₃ [

25,

26] as a filler for LDPE improves impact strength, heat resistance, elastic modulus, tensile strength, and resistance to environmental stress cracking. However, increasing the chalk content leads to a higher degree of crystallinity, which is subsequently associated with a reduction in the elastic modulus.

In the food and dairy industries, a classic example of modified packaging materials is PE film with fillers. This material is used for manufacturing milk and fermented dairy beverage pouches, as well as sheet materials for thermoformed packaging. Dispersed titanium dioxide (TiO₂) and food-grade carbon black (C) are commonly used as base fillers in such films [

15,

27,

28].

A promising area of research is the development of modified functional packaging, known as "active packaging", which has a beneficial effect upon contact with food products. Active packaging includes antimicrobial and antioxidant films that incorporate natural plant-based extracts as functional agents [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. These substances migrate from the packaging material to the product over time and prevent surface spoilage by inhibiting undesirable microorganisms [

37,

38] or slowing oxidative processes. Dairy products, particularly those with a short shelf-life, are especially prone to microbiological contamination and spoilage caused by oxidation [

37,

39,

40]. The use of active packaging materials is most appropriate for solid products with a large contact surface area, such as butter, cheese, high-fat products, functional foods, and infant foods [

32,

37,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

Previous studies [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50] have examined the interactions between polymer molecules and modifiers in the melt, as well as their influence on the overall set of tensile and sensory properties.

However, the incorporation of various functional components into the polymer matrix of food packaging may present challenges due to differences in operating temperatures or pose risks to quality and safety [

41,

45,

51,

52]. Milk is a complex, multi-component system that can be affected by certain packaging modifiers, with the potential to form toxic compounds.

An overview of Russian and global research [

9,

10,

11,

12,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50] on synthetic polymer materials with high mineral filler content, including those used in food packaging, highlights the relevance of studying the tensile properties of PE films with varying levels of CaCO₃ filler. This is also supported by the global trend toward expanding the use of modified and functional packaging. Analysis of the changes in tensile properties and structure of such materials may provide insights into their resistance to degradation. These findings may also help mitigate the risk of microplastic formation and subsequent migration into food products during storage. This study aims to investigate the tensile, structural, and hygienic properties of PE films modified with varying CaCO₃ and DHQ (natural antioxidant) contents, for potential application in food packaging.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Calcium Carbonate

Calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), commonly known as chalk, is the most widely used filler for polyolefins [

53]. It is typically derived from natural sources such as marble and limestone, and its abundance makes it a cost-effective additive. Chalk-based fillers can increase processing efficiency by reducing cooling rates during molding, raise the operating temperature of the material, and enhance insulation in electrical applications [

54]. Additionally, the incorporation of CaCO₃ enhances the whiteness of opaque or white materials and imparts brightness and gloss to colored surfaces [

55].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of calcium carbonate.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of calcium carbonate.

CaCO₃ is also extensively used as a filler in the packaging industry. It is an economical additive capable of improving various polymer properties (tensile strength, barrier properties, and impact resistance). When incorporated into polymer films, CaCO₃ increases rigidity and reduces the permeability to gases and liquids [

54,

55,

56]. CaCO₃ can also enhance the surface hardness and abrasion resistance of polymer materials [

57]. Additionally, it may improve the heat resistance of polymers and reduce the flammability of polymer films [

57]. The incorporation of CaCO₃ can also affect polymer processing behavior, influencing parameters such as melt viscosity and crystallization kinetics [

58]. The particle size and shape of the filler are likewise known to impact the final properties of the polymer material [

59]. In this study, CaCO₃ was incorporated using a masterbatch, the technical specifications of which are presented in

Table 1.

The particle size distribution of the mineral filler affects the visual appearance of the final product by preventing the formation of visible CaCO₃ agglomerates on the surface. In addition, particle size influences the material’s ability to form joints. A uniform composition of the chalk-based filler ensures consistent thermal conductivity, which facilitates the formation of smooth and strong joints.

2.2. Dihydroquercetin

Dihydroquercetin (DHQ) is a natural antioxidant and polyphenol primarily extracted from the root wood of Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and certain other coniferous species. It can also be obtained in smaller amounts from the seeds of milk thistle and peony. DHQ is a flavonoid belonging to the quercetin group – an antioxidant of natural origin and a known component of food products (

Figure 2) [

59].

DHQ is classified as a bioflavonoid, also known as vitamin P, which is not synthesized in the human body. Among all polyphenols, DHQ exhibits notably high antioxidant activity, along with anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic effects [

60].

Table 2 presents selected technical characteristics of the DHQ used in this study.

In the food industry, dihydroquercetin (DHQ) is used as an additive to reduce oxidative degradation during storage and to extend product shelf life.

2.3. Polyethylene

Low-density polyethylene (LDPE), grade 15803-020, produced by SIBUR, was selected as the base polymer for film production. The main technical characteristics of the raw material are presented in

Table 3.

This LDPE grade is used for the production of films and film-based products intended for food applications.

2.4. Modified Films

Film samples were produced using an SJ-28 laboratory-scale extruder. To improve dispersion in the polymer melt, a masterbatch was employed and mechanically blended with the base LDPE using a tumbling drum.

The extrusion line and its technical specifications are shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 4.

The following polymer film compositions were prepared for the study: LDPE film based on grade 15803-20 (LDPE); LDPE film with 20.0% CaCO₃ (LDPE 20 CaCO₃); LDPE film with 40.0% CaCO₃ (LDPE 40 CaCO₃); LDPE film with 0.5% dihydroquercetin (DHQ) (LDPE + 0.5 DHQ); LDPE film with 20.0% CaCO₃ and 0.5% DHQ (LDPE 20 + 0.5 DHQ); LDPE film with 40.0% CaCO₃ and 0.5% DHQ (LDPE 40 + 0.5 DHQ); LDPE film with 20.0% CaCO₃ and 1.0% DHQ (LDPE 20 + 1.0 DHQ); LDPE film with 40.0% CaCO₃ and 1.0% DHQ (LDPE 40 + 1.0 DHQ).

The developed materials show strong potential for use in the food industry as functional packaging in various formats, with the ability to enhance product stability during storage.

2.5. Methods

Stress at break (σ), strain at break (ε), and the joint strength were measured in accordance to GOST 14236-81 and GOST 12302-2013 using a Shimadzu EZ-LX tensile tester (with a 2 kN load cell and traverse stroke length 920 mm), equipped with TRAPEZIUM X software.

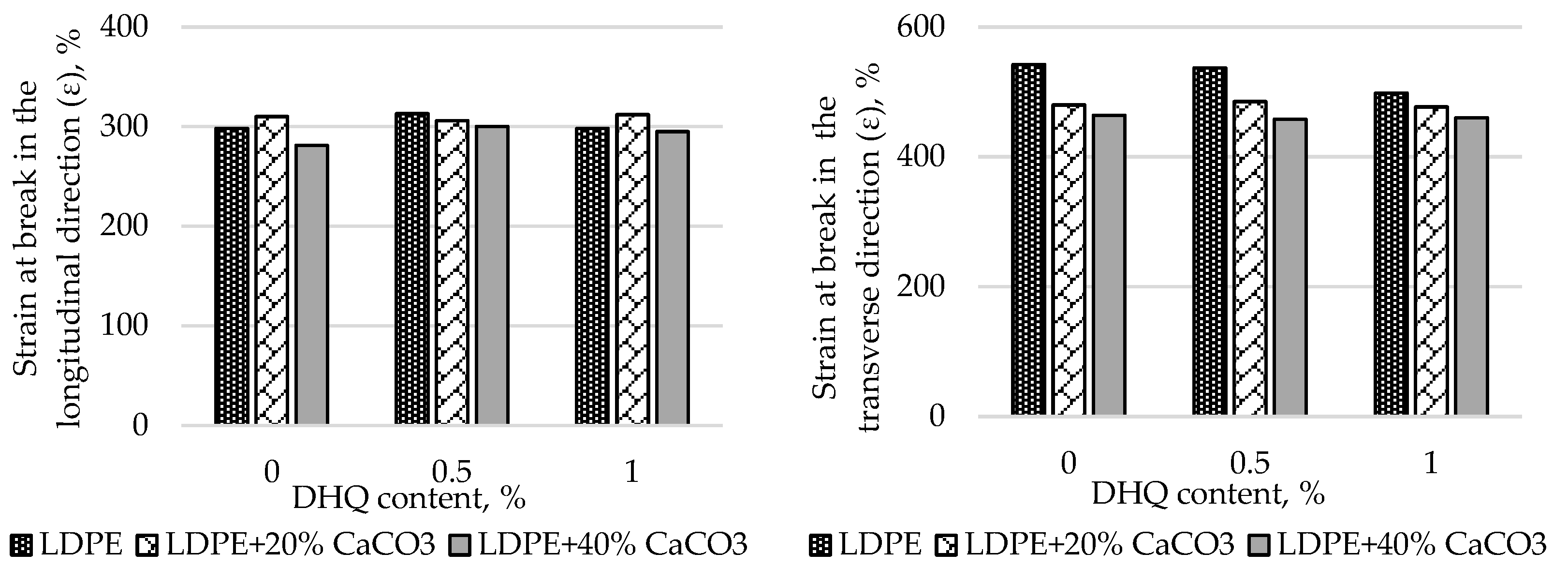

The sessile drop method was used to determine the contact angle, defined as the angle formed between the tangent to the surface of a droplet of wetting liquid and the solid surface at the point of contact.

Surface morphology of the developed film samples was evaluated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) on a Vega 3 scanning electron microscope (Tescan, Czech Republic), equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) detector, X-Act (Oxford Instruments, UK). Before imaging, the samples were sputter-coated with a ~20 nm platinum layer.

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of LDPE- and HDPE-based films with varying filler content were obtained using a Perkin Elmer Spectrum One FTIR spectrometer equipped with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory. For each sample, 64 scans were recorded at a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹ in the range of 4000–650 cm⁻¹.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was used to analyze the surface morphology of the films. Measurements were carried out in semi-contact mode using the Ntegra Prima scanning probe system (NT-MDT, Russia), with configuration-specific settings including output signal amplitude, loop gain, piezo actuator frequency, and detector sensitivity. A "CSG01" cantilever (dimensions: 3.4 × 1.6 × 0.3 mm, tip radius 10 nm, spring constant 0.03 N/m) was used. The acquired data were processed and comparatively analyzed using the Nova software package (NT-MDT), based on the INTEGRA and Solver platforms.

Data visualization was performed using Microsoft Office applications (MS Word, MS Excel).

3. Results and Discussion

Experimental film samples based on LDPE grade 15803-20 with varying contents of CaCO₃ and DHQ were produced (

Figure 4). The width of the resulting film bubble was 175 ± 2 mm, and the film thickness was 35 ± 3 µm.

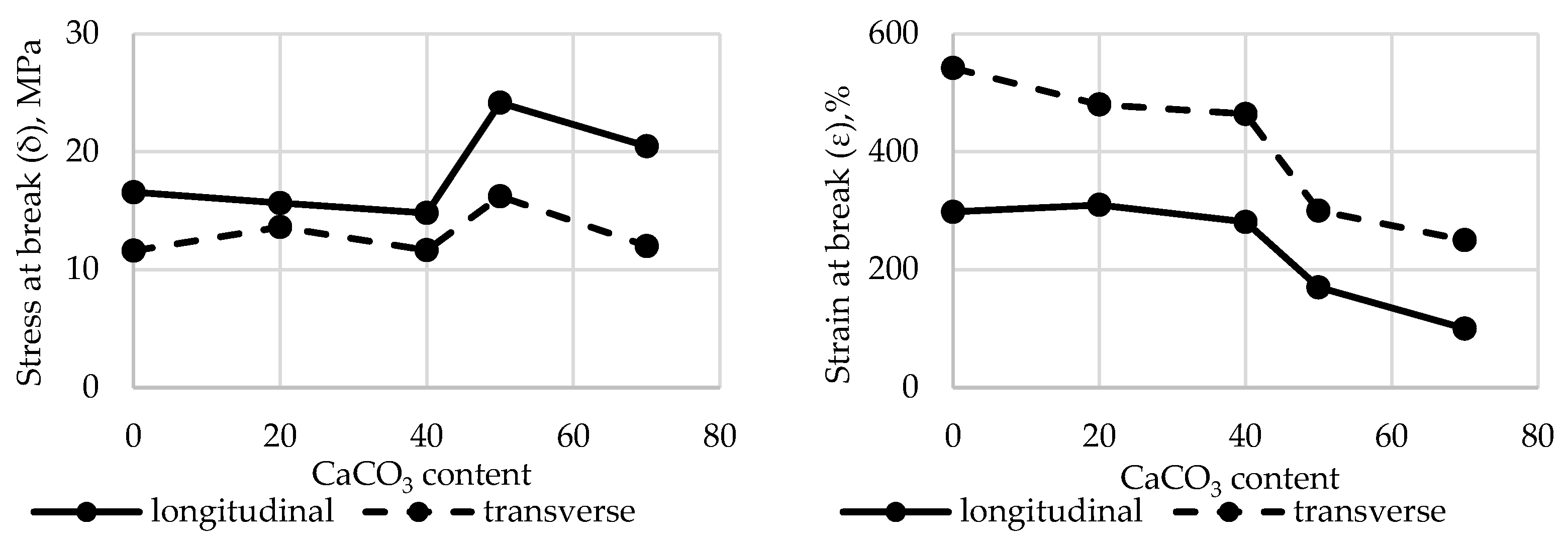

Results of Tensile Properties Evaluation

A comprehensive study was carried out to assess the effect of CaCO₃ content on the tensile properties of polyethylene films. The results are presented in

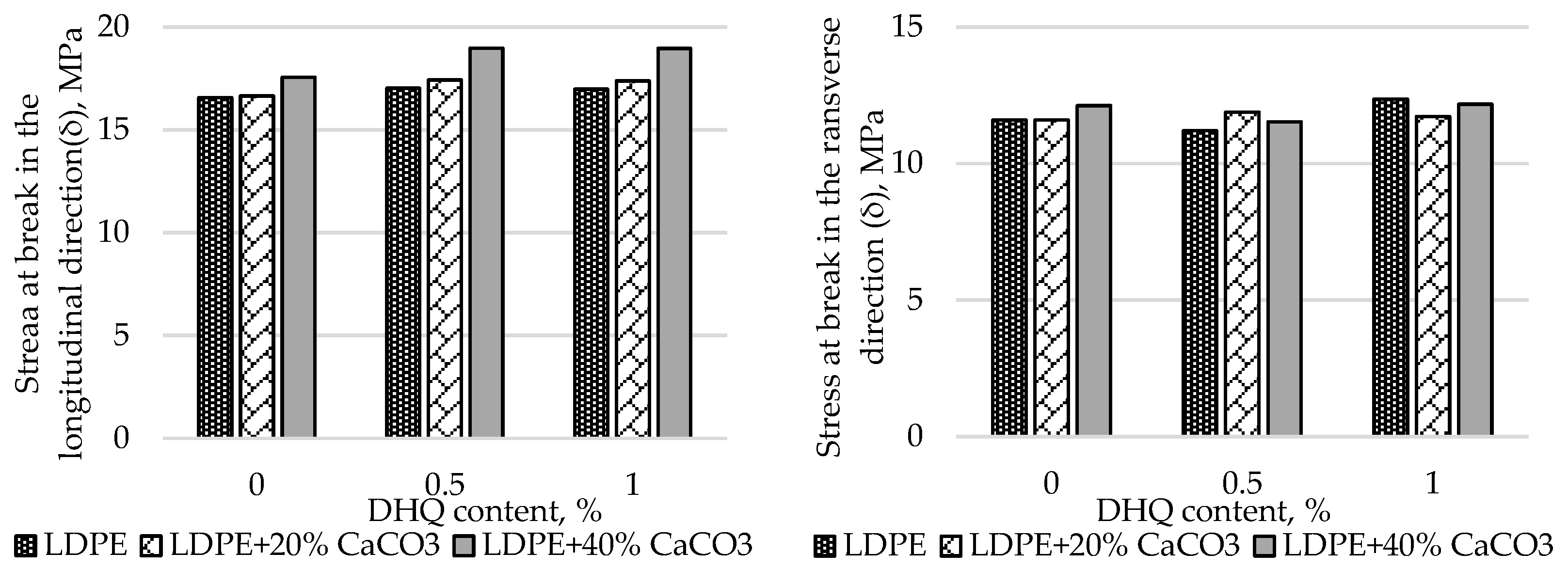

Figure 5.

The results show that the σ (stress at break) of polyethylene films filled with up to 40% CaCO₃ changes slightly. However, in samples containing more than 50.0% filler, stress at break increases by 45.9% in the longitudinal direction and by 39.8% in the transverse direction. Strain at break (ε) is more significantly affected. At 70% CaCO₃ filler content, ε decreases by 66.4% (longitudinal) and 53.9% (transverse), respectively. This may be attributed to the fact that the addition of a low-molecular-weight inorganic filler alters the polymer matrix structure and weakens intermolecular interactions within the polymer.

The strength of joints in the polyethylene film with fillers was measured to determine their suitability for packaging applications. The results are presented in

Figure 6.

Joint strength decreased by 38.3–49.8% in both longitudinal and transverse directions as CaCO₃ content increased, compared to the LDPE film without fillers.

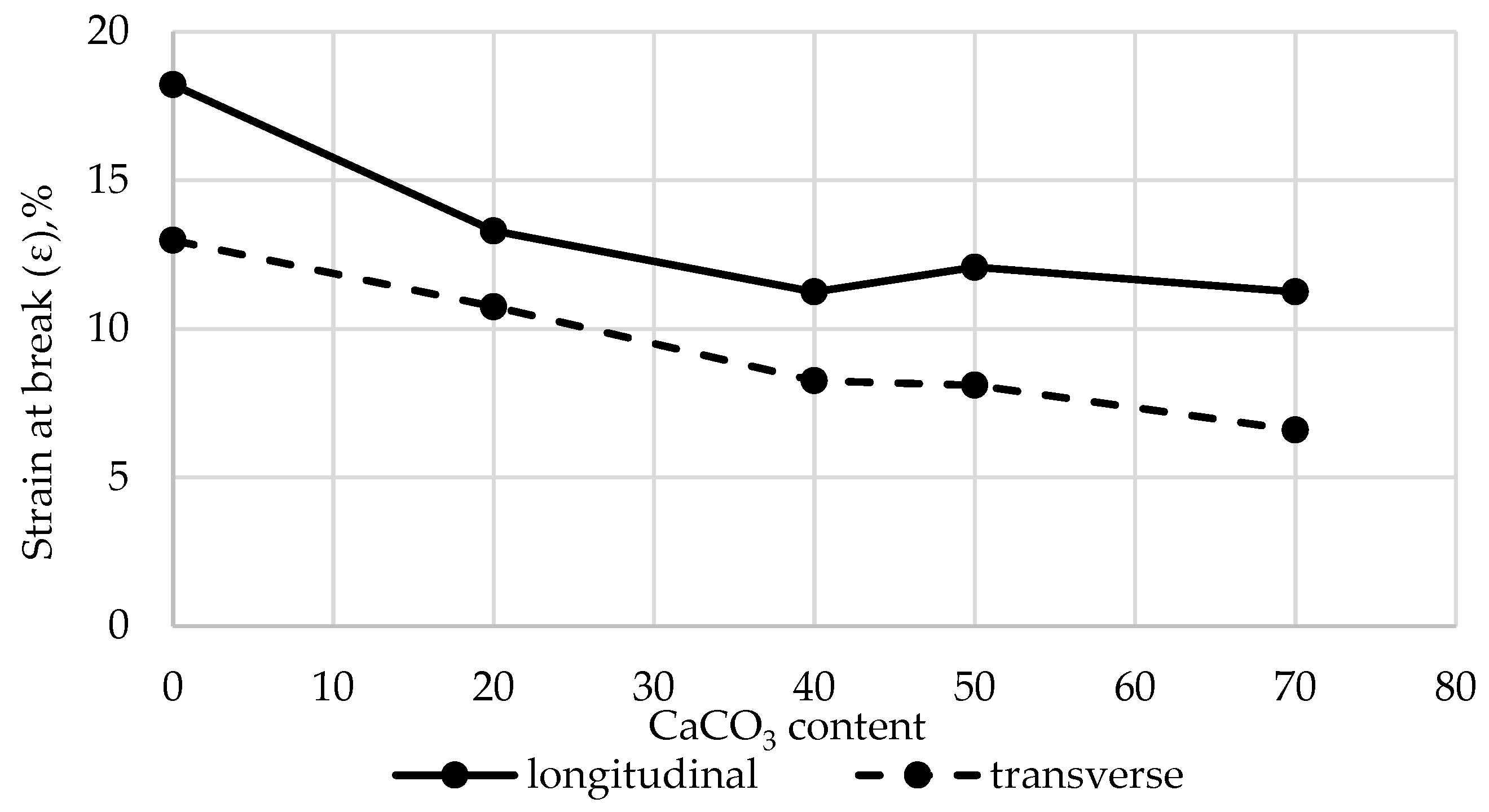

Preliminary studies on the influence of CaCO₃ on the tensile properties of LDPE films revealed a substantial decline in strength when the filler content exceeded 50%. Therefore, all subsequent experiments were performed using a CaCO₃ content of no more than 40.0%. The results are shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

At the initial stage, the effects of CaCO₃ and DHQ on the tensile properties of the developed LDPE-based films were investigated. The results indicate that the incorporation of CaCO₃ by itself led to only minor changes in stress at break (σ). However, incorporation of DHQ at contents up to 1.0% into the polymer matrix containing various amounts of mineral filler resulted in an increase in the stress at break by up to 8.0% in the longitudinal direction and up to 6.5% in the transverse direction.

The strain at break (ε) of the samples also remained virtually unchanged, with deviations not exceeding 5.0% compared to the control film without fillers. Films with high filler contents exhibited higher values of stress at break than the unmodified LDPE base material. Depending on the filler content, stress at break values increased by 2.3% to 12.0% in the longitudinal direction and by 2.8% to 4.5% in the transverse direction.

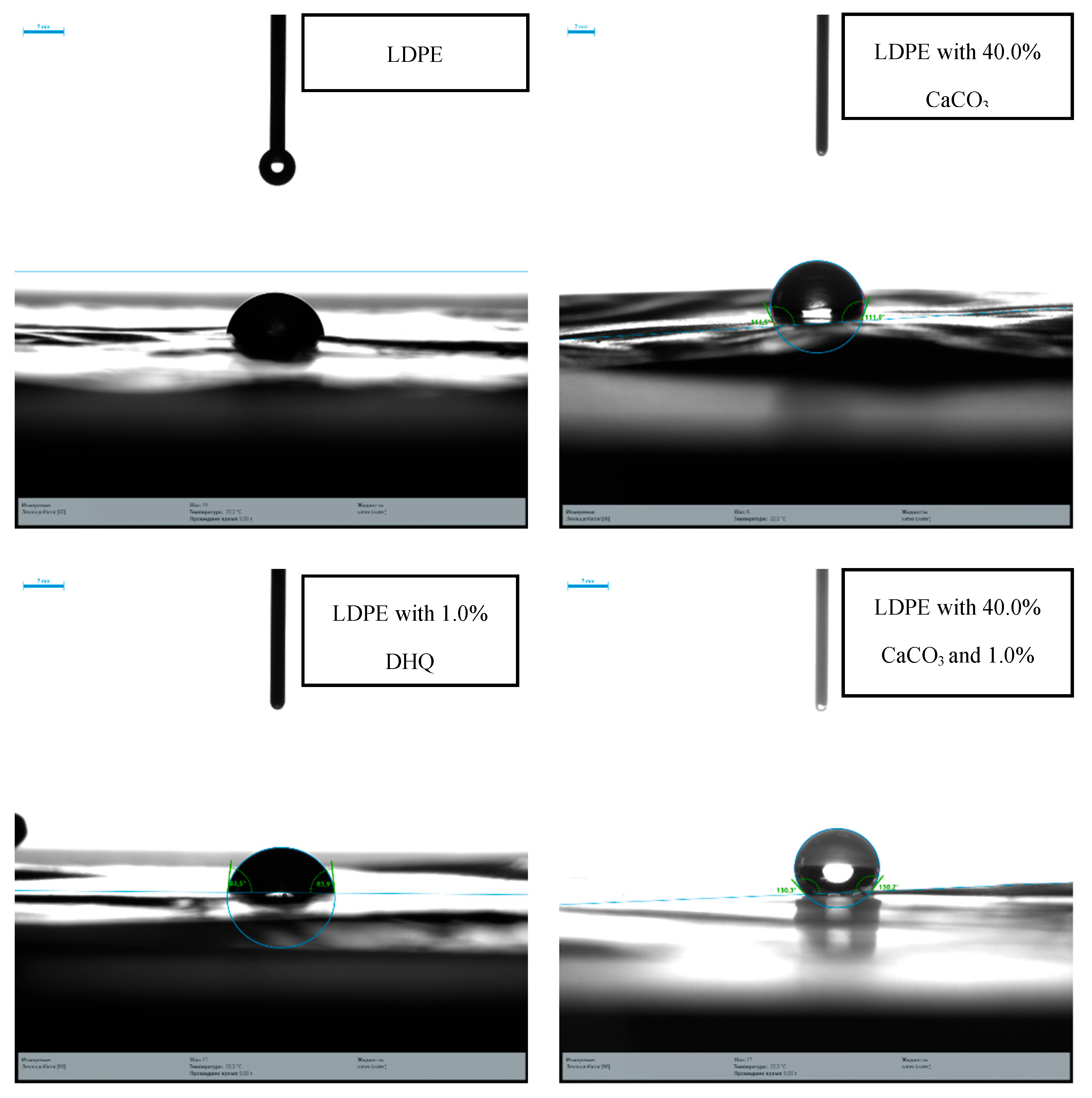

SEM Microstructural Analysis

Structural changes in the LDPE-based films modified with 20% and 40% CaCO₃ were assessed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The results are presented in

Figure 10.

According to the SEM images, CaCO₃ (20% and 40%) is distributed uniformly in the LDPE matrix, with no significant differences visible at 100 µm magnification. However, at 20 µm magnification, the surface of the film with 40.0% CaCO₃ appears more porous, with numerous fine mineral particles observed near the surface. No through-holes, cracks, or tears were detected. At higher magnification, some CaCO₃ particles appear to separate from the polymer matrix; however, they are not deep or extensive enough to influence the visual integrity of the film or interfere with subsequent evaluation of its physical-mechanical properties.

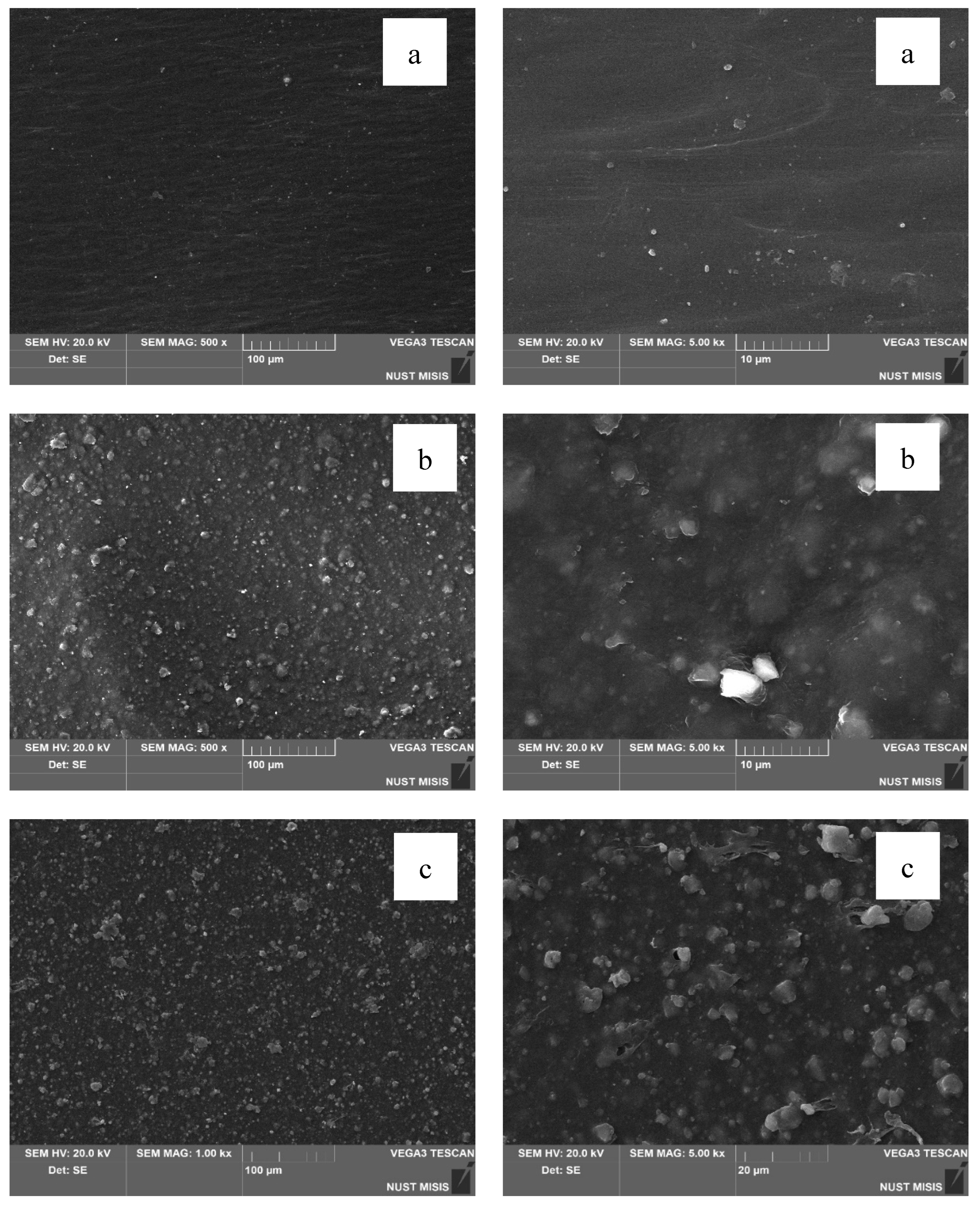

In the next stage, the surface morphology of LDPE films with 40.0% CaCO₃ and 0.5% or 1.0% DHQ was assessed. The results are presented in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12.

The SEM images in

Figure 11 show that the surfaces of LDPE films with 20.0% CaCO₃ and 0.5% or 1.0% DHQ exhibit no visible chipping, tearing, or cracking. This indicates a sufficiently uniform dispersion of filler particles within the polymer melt. In comparison with films without DHQ, the modified samples show a notable presence of numerous fine crystalline particles on the surface. These are DHQ particles, which tend to migrate to the surface due to their relatively high molecular weight.

As shown in

Figure 12, the surface morphology of LDPE films highly filled with 40.0% CaCO₃ and 0.5% or 1.0% DHQ reveals no visible chipping, tearing, or cracking. However, in contrast to the samples with 20.0% CaCO₃, the number of fine antioxidant particles on the surface is noticeably lower. This may be due to the higher filler load, which could hinder the diffusion of DHQ molecules to the surface. This phenomenon requires further investigation.

The microstructural analysis of films filled with an antioxidant confirms the presence of DHQ particles on the surface. The surface localization of DHQ particles may enhance the antioxidant activity precisely at the film–product interface in dairy applications. Additionally, DHQ migration occurs on both the inner and outer surfaces of the film, potentially improving adhesion properties. These surface observations are consistent with the results of the tensile properties analysis.

The incorporation of different fillers and modifiers can influence the degradation behavior of polymer materials, which in turn may affect their strength and contribute to microplastic formation and migration into packaged foods.

The structural analysis suggests that high CaCO₃ content reduces surface homogeneity. However, no discrete agglomerates of filler or polymer were visually detected, indicating the potential morphological stability of the material during its use in food packaging applications.

Surface Morphology Analysis of LDPE-Based Filled Films Using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

The obtained AFM data were processed and comparatively analyzed using the Nova SPM software package (NT-MDT, Russia) based on the INTEGRA and Solver platforms. Surface images in various planes are presented in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 and

Table 5 and

Table 6.

The statistical analysis of the surface topography of LDPE-based filled films is summarized in

Table 6.

Based on the data in

Table 6, it was observed that increasing the DHQ content in the formulation led to a decrease in surface roughness. However, the overall surface profile became more heterogeneous. For instance, the average surface roughness (Ra) of the LDPE film with 40% CaCO₃ and 1.0% DHQ was 1.3 times lower than that of the LDPE film with 40% CaCO₃.

It was found that decreasing the CaCO₃ content to 20 wt.% while maintaining the same DHQ content (0.5% and 1.0% by weight) led to a significant reduction in both average surface roughness and the depth of surface pores (

Table 7).

The data obtained were consistent with those presented in

Table 5: increasing the DHQ content led to a reduction in both Ra and Rpm values. Specifically, the average surface roughness (Ra) decreased by a factor of 1.6 with a 0.5 wt.% increase in DHQ content.

The AFM analysis confirmed that CaCO₃, when added at varying contents, influences both surface roughness and heterogeneity of the developed films. The incorporation of DHQ contributed to a smoother, more uniform surface morphology.

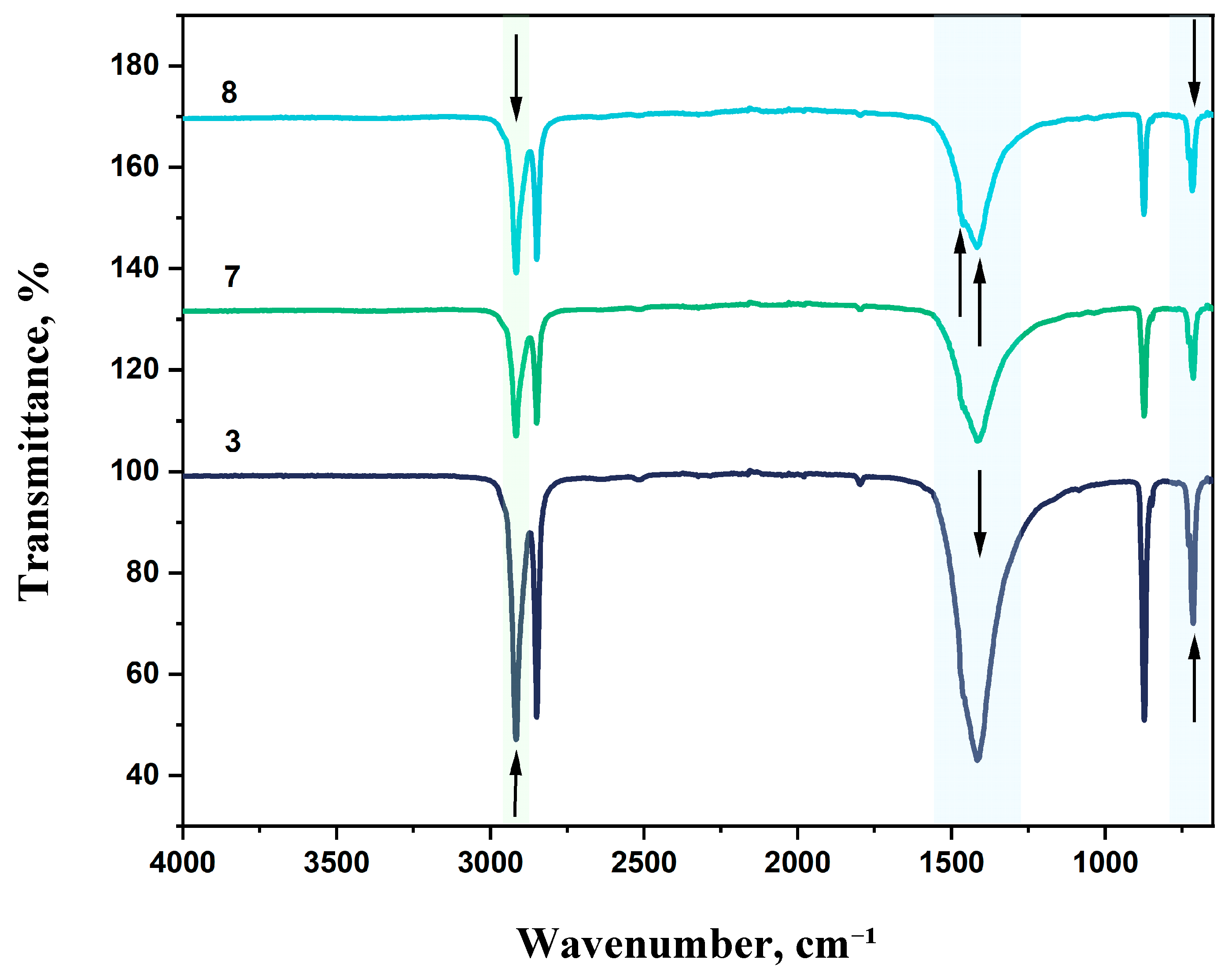

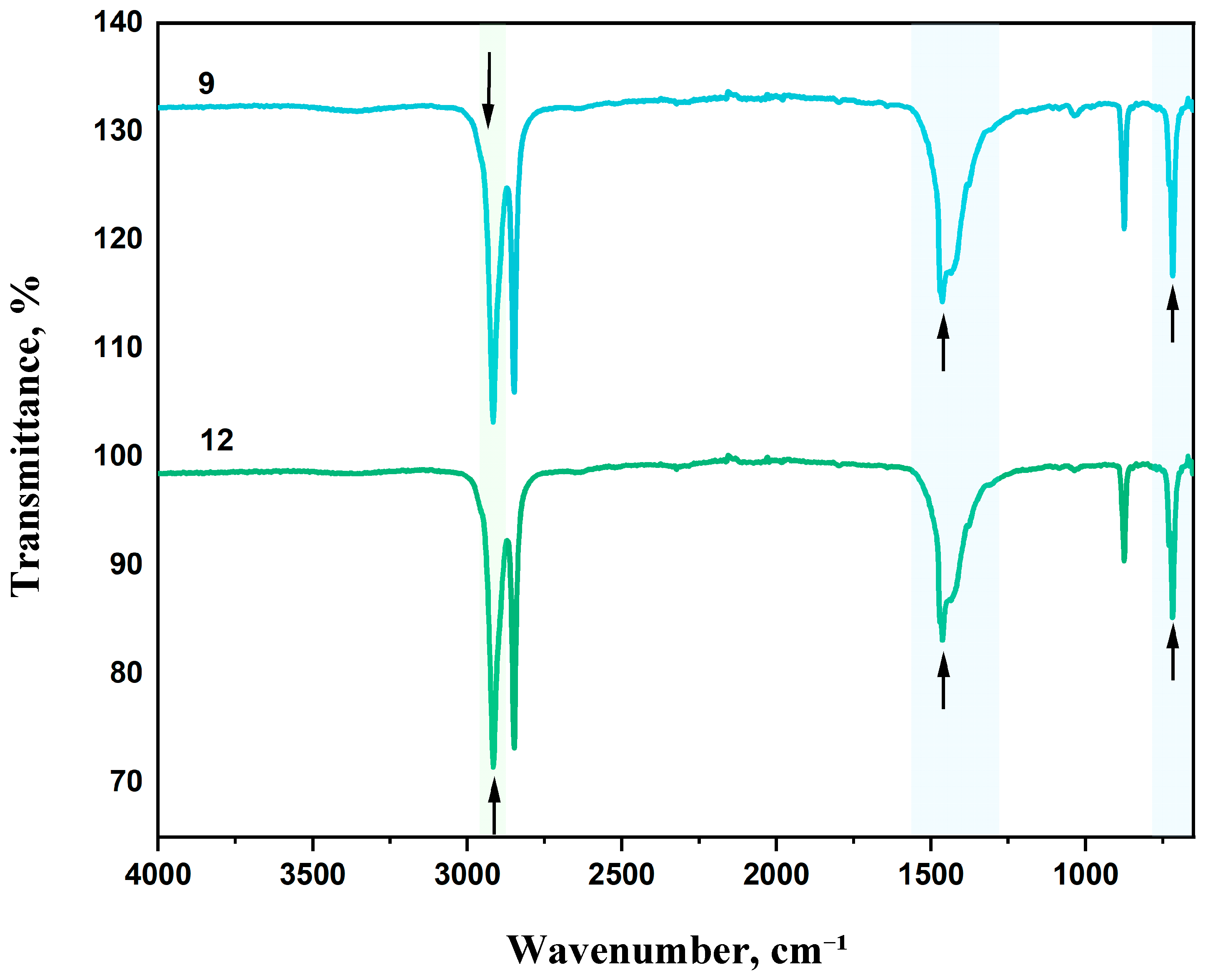

FTIR Analysis of Modified LDPE Films

LDPE is characterized by strong asymmetric (ν

as CH₂) and symmetric (ν

s CH₂) stretching vibrations observed at 2918 and 2851 cm⁻¹, respectively. A medium-intensity absorption band at 1085 cm-¹ corresponds to C–C stretching vibrations. The band near 1462 cm⁻¹ is associated with asymmetric CH₂ bending vibrations (δ CH₂), which are typical for all polyethylene types. A weak band at 1373 cm⁻¹ may be attributed to bending vibrations [

61]. The absorption maximum at 714 cm⁻¹ is also due to CH₂ vibrations.

FTIR spectra of LDPE-based film samples containing CaCO₃ and DHQ are shown in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16.

The effect of filler content on the structure of LDPE-based film materials produced by blown film extrusion was investigated using attenuated total reflectance Fourier-transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy. For films with up to 40 wt.% CaCO₃, a slight shift in the absorption band corresponding to asymmetric stretching vibrations of –CH₂– groups is observed, with the peak position moving to 2912 cm⁻¹. This type of filler does not affect the RCH₂–CO–CH₂R group or the C–C bond. However, a new absorption peak appears at 873 cm⁻¹, which is not typical for standard LDPE grades.

Further incorporation of 0.5% and 1.0% DHQ results in a reduction in the intensity of the asymmetric –CH₂– stretching vibrations (νas CH₂) and shifts this band to 2917 cm⁻¹. With increasing DHQ content, a distinct shift of the CH₂-related band from 714 to 718 cm⁻¹ is also observed, along with the appearance of minor absorption bands at 1471 and 1455 cm⁻¹, which may be attributed to vibrations of functional groups present in DHQ.

A decrease in CaCO₃ content to 20 wt.% while maintaining equivalent DHQ levels (0.5 and 1.0 wt.%) resulted in a shift of the asymmetric CH₂ stretching vibration band (ν

as CH₂) from 2912 cm⁻¹ to 2916 cm⁻¹ (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16). Additionally, lowering the crystalline filler content increased the intensity of bands at 1455, 1463, and 1472 cm⁻¹.

As in previous samples, variation in filler content did not affect the C–C stretching band at 1085 cm⁻¹.

This band of medium intensity consistently corresponds to C–C vibrations. The band at 1462 cm⁻¹ reflects asymmetric CH₂ bending vibrations typical of polyethylene [

62,

63].

The absorption maximum at 714 cm⁻¹ also corresponds to CH₂ vibrations. In highly crystalline polyethylene, this peak may split, leading to the appearance of an additional band at 730 cm⁻¹.

4. Conclusions

Test samples of LDPE (grade 15803-20) films were produced and modified with 20.0%, 40.0%, 50.0%, and 70.0% CaCO₃ and 0.5% and 1.0% DHQ (the natural antioxidant), as well as their combinations.

Tensile properties analysis revealed that incorporating 40.0% CaCO₃ into LDPE had a negligible effect on the stress at break (σ) in both longitudinal and transverse directions compared to the unmodified control. Beyond this filler content, stress at break initially increased, then decreased as the filler content reached 70%. Changes in strain at break (ε) became pronounced at 40% filler content, with further increases leading to a loss of elasticity. These results suggest that an optimal filler content for maintaining tensile properties is no more than 40.0%. The joint strength measurements revealed only minor variations across the tested filler contents, indicating that all modified films retained their ability to form strong joints and heat-seal effectively.

It was demonstrated that adding up to 1.0% DHQ to the LDPE matrix with CaCO₃ led to an increase in σ by up to 8.0% in the longitudinal direction and 6.5% in the transverse direction. Strain at break remained largely unchanged, with deviations of no more than 5.0% relative to the unmodified control film. Joint strength of LDPE films decreased by 18.0–60.0% as CaCO₃ content increased (up to 40.0%), while the addition of DHQ up to 1.0% had a limited impact, with reductions not exceeding 6.0% compared to the control film.

Contact angle measurements confirmed that surface adhesion properties are significantly affected by the CaCO₃ content. The contact angle ranged from 84–86° for unmodified LDPE, 90–100° for films with 20.0% CaCO₃, and above 100° for those with 40.0% mineral filler.

SEM analysis of films with high CaCO3 content and DHQ revealed visible antioxidant particles on the film surface, suggesting enhanced antioxidant potential at the interface between the film and dairy products. DHQ was found to migrate to both the outer and inner surfaces, which may also influence the adhesion behavior of the material.

AFM analysis confirmed that different CaCO₃ content alters the surface roughness and heterogeneity of the films. The presence of DHQ contributed to surface smoothing and improved homogeneity.

FTIR spectroscopy revealed that the incorporation of CaCO₃ influenced the overall spectral profile of polyethylene, resulting in decreased peak intensities depending on the concentration of the filler.

Overall, the comprehensive analysis showed that CaCO₃ and DHQ incorporation at the selected contents did not have a detrimental effect on the tensile or structural properties of the modified LDPE films. The developed materials proved to be stable and hold promise for applications in the food industry, both as functional packaging and as a potential solution to minimize microplastic migration from the surface.

Author Contributions

Writing—reviewing and editing, D.M.; writing—preparation of the original project, O.F. and D.M.; conceptualization, O.F.; examination, D.M.; investigation, O.F., D.M., A.A, P.P and S.S; methodology, O.F.; visualization, D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was carried out as part of the implementation of the State task of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lee, J. G.; Jeong, J. O.; Jeong, S. I.; Park, J. S. Radiation-based crosslinking technique for enhanced thermal and mechanical properties of HDPE/EVA/PU blends. Polymers 2021, 13(16), 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, M.; Tu, W.; Yang, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J. Sustainable chemical upcycling of waste polyolefins by heterogeneous catalysis. SusMat 2022, 2(2), 161–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Min, M. Exploring the Effects of Nano-CaCO3 on the Core–Shell Structure and Properties of HDPE/POE/Nano-CaCO3 Ternary Nanocomposites. Polymers 2024, 16(8), 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Solis-Ramos, E.; Yi, Y.; Kumosa, M. UV degradation model for polymers and polymer matrix composites. Polymer degradation and stability 2018, 154, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tertyshnaya, Y. V.; Podzorova, M. Effect of UV irradiation on the structural and dynamic characteristics of polylactide and its blends with polyethylene. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2020, 14, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowaczyk, G.; Głowinkowski, S.; Jurga, S. Rheological and NMR studies of polyethylene/calcium carbonate composites. Solid state nuclear magnetic resonance 2004, 25(1-3), 194-199.

- Sreekumar, P. A.; Elanamugilan, M.; Singha, N. K.; Al-Harthi, M. A.; De, S. K.; Al-Juhani, A. LDPE filled with LLDPE/Starch masterbatch: Rheology, morphology and thermal analysis. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2014, 39, 8491–8498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsh, I.A.; Ananiev, V.V.; Chalykh, T.I.; Sogrina, D.A.; Pomogova, D.A. Study of the effect of ultrasonic treatment on the rheological properties of polymers during their multiple recycling. Plast. Massy 2014, 11–12, 45–48. (in Russian).

- Mikhailin, Yu. A. Thermally Stable Polymers and Polymer Materials. / Profession. 2006. 623 p.

- Babayevsky, L. G. (Ed.). Fillers for Polymeric Composite Materials: A Reference Guide (Translated from English). Moscow: Khimiya. 1986. 726 p.

- Panova, L. G. Fillers for Polymeric Composite Materials. 2010.

- Berlin, A. A. (Ed.). Polymer Composite Materials: Structure, Properties, and Processing. St. Petersburg: Professiya. 2008. 557 p.

- Maurer, F. H. J.; Kosfeld, R.; Uhlenbroich, T. Interfacial interaction in kaolin-filled polyethylene composites. Colloid and Polymer Science 1985, 263, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothon, R. N. Mineral fillers in thermoplastics: filler manufacture and characterisation. Mineral Fillers in Thermoplastics I: Raw Materials and Processing 1999, 67-107.

- Thio, Y. S.; Argon, A. S.; Cohen, R. E.; Weinberg, M. Toughening of isotactic polypropylene with CaCO3 particles. Polymer 2002, 43(13), 3661–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadal, R. S.; Misra, R. D. K. The influence of loading rate and concurrent microstructural evolution in micrometric talc-and wollastonite-reinforced high isotactic polypropylene composites. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2004, 374(1-2), 374-389.

- Jia, X.; Wen, Q.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gao, D.; Ru, Y.; Chen, N. Preparation and Performance of PBAT/PLA/CaCO3 Composites via Solid-State Shear Milling Technology. Polymers 2024, 16(20), 2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longkaew, K.; Gibaud, A.; Tessanan, W.; Daniel, P.; Phinyocheep, P. Spherical CaCO3: Synthesis, Characterization, Surface Modification and Efficacy as a Reinforcing Filler in Natural Rubber Composites. Polymers 2023, 15(21), 4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Song, B.; Tee, T. T.; Sin, L. T.; Hui, D.; Bee, S. T. Investigation of dynamic characteristics of nano-size calcium carbonate added in natural rubber vulcanizate. Composites Part B: Engineering 2014, 60, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, M. O.; Shakoor, A.; Rehan, M. S.; Gill, Y. Q. Development of HDPE composites with improved mechanical properties using calcium carbonate and NanoClay. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2021, 606, 412568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghari, H. S.; Jalali-Arani, A. Nanocomposites based on natural rubber, organoclay and nano-calcium carbonate: Study on the structure, cure behavior, static and dynamic-mechanical properties. Applied Clay Science 2016, 119, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, C.; Luo, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, B. ;... Ji, J. Effect of talc and diatomite on compatible, morphological, and mechanical behavior of PLA/PBAT blends. e-Polymers 2021, 21(1), 234-243.

- Sarkawi, S. S.; Dierkes, W. K.; Noordermeer, J. W. Reinforcement of natural rubber by precipitated silica: The influence of processing temperature. Rubber chemistry and technology 2014, 87(1), 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data Intelligence «Filled Polymers Market Size, Competitive Landscape and Market Forecast - 2029». Available online: https://www.datamintelligence.com/research-report/filled-polymers-market (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Sultonov, N. Zh. Composite Materials Based on Low-Density Polyethylene and Nanosized Calcium Carbonate. 2011.

- Parsons, E. M.; Boyce, M. C.; Parks, D. M.; Weinberg, M. Three-dimensional large-strain tensile deformation of neat and calcium carbonate-filled high-density polyethylene. Polymer 2005, 46(7), 2257–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, H.; Yasir, M.; Ali, F.; Nazir, A.; Ali, A.; Al Huwayz, M. ;... Iqbal, M. Photocatalytic degradation of atrazine and abamectin using Chenopodium album leaves extract mediated copper oxide nanoparticles. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie 2023, 237(6), 689-705.

- Boutillier, S.; Casadella, V.; Laperche, B. Economy–innovation economics and the dynamics of interactions. Innovation Economics, Engineering and Management Handbook 1: Main Themes 2021, 1-23.

- Fomichev, Yu. P. , Nikanova, L. A., Dorozhkin, V. I., Torshkov, A. A., Romanenko, A. A., Eskov, E. K.,... Stolnaya, N. I. (2017). Dihydroquercetin and Arabinogalactan: Natural Bioregulators in Human and Animal Physiology, Applications in Agriculture and the Food Industry. [In Russian].

- Srisa, A.; Harnkarnsujarit, N. Antifungal films from trans-cinnamaldehyde incorporated poly (lactic acid) and poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) for bread packaging. Food Chemistry 2020, 333, 127537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Jafari, S. M.; Sharma, S. Antimicrobial bio-nanocomposites and their potential applications in food packaging. Food Control 2020, 112, 107086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryanichnikova, N. S. Protective Coatings for Food Products. In Modern Advances in Biotechnology: Equipment, Technologies, and Packaging for the Implementation of Innovative Projects in Food and Biotechnological Industries. Proceedings of the VII International Scientific and Practical Conference, Pyatigorsk, 2020, pp. 86–89.

- Pryanichnikova, N. S. Edible Packaging: A Carrier for Functional and Bioactive Compounds. Dairy River, 2020, (4), 32–34.

- Filchakova, S. A. Microbiological Purity of Packaging for Dairy Products. Dairy Industry, 2008, 7, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Yurova, E. A.; Filchakova, S. A. Assessment of Quality and Shelf Life of Functionally Oriented Dairy Products. Milk Processing, 2019, (10), 6–11.

- Fedotova, O. B. Packaging for Milk and Dairy Products: Quality and Safety. Moscow: Rosselkhozacademy Publishing House, 2008.

- Kirsh, I.; Frolova, Y.; Bannikova, O.; Beznaeva, O.; Tveritnikova, I.; Myalenko, D.; ... Zagrebina, D. Research of the Influence of the Ultrasonic Treatment on the Melts of the Polymeric Compositions for the Creation of Packaging Materials with Antimicrobial Properties and Biodegrability. Polymers 2020, 12(2), 275.

- Illarionova, E. E.; Turovskaya, S. N.; Radaeva, I. A. To the question of increasing of canned milk storage life. Actual Issues of the Dairy Industry, Intersectoral Technologies and Quality Management Systems 2020, 1, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fedotova, O. B.; Pryanichnikova, N. S. Research of the polyethylene packaging layer structure change in contact with a food product at exposure to ultraviolet radiation. Food systems 2021, 4(1), 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobkova, Z.S.; Fursova, T.P.; Zenina, D.V. Protein ingredients selection, enriching and modifying the oxidum drinks structure. Aktualnye voprosy industrii napitkov. Izdatelstvo i tipografiya “Kniga-memuar,” 2018, 64–69.

- Yurova, E. A.; Filchakova, S. A. Evaluation of Quality and Shelf Life of Functionally Oriented Dairy Products. Milk Processing, 2019, (10), 6–11.

- Khurshudyan, S. A.; Pryanichnikova, N. S.; Ryabova, A. E. Food Quality and Safety: Transformation of Concepts. Food Industry 2022, 3, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zobkova, Z. S. Defects in Milk and Dairy Products: Causes and Prevention Measures. 2006. 99 p.

- Yurova, E.A. Quality control and safety of milk-based functional products. Dairy Industry. Autonomous Nonprofit Organization Publishing Dairy Industry, 2020, 70, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galstyan, A. G.; Aksyonova, L. M.; Lisitsyn, A. B.; Oganesyants, L. A.; Petrov, A. N. Modern approaches to storage and effective processing of agricultural products for obtaining high quality food products. Herald of the Russian academy of sciences 2019, 89, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaeva, I. A.; Illarionova, E. E.; Turovskaya, S. N.; Ryabova, A. E.; Galstyan, A. G. Principles of Quality Assurance for Domestic Powdered Milk. Food Industry, 2019, (9), 54–57.

- Bartczak, Z.; Argon, A. S.; Cohen, R. E.; Weinberg, M. Toughness mechanism in semi-crystalline polymer blends: II. High-density polyethylene toughened with calcium carbonate filler particles. Polymer 1999, 40(9), 2347-2365.

- Tiemprateeb, S.; Hemachandra, K.; Suwanprateeb, J. A comparison of degree of properties enhancement produced by thermal annealing between polyethylene and calcium carbonate–polyethylene composites. Polymer testing 2000, 19(3), 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thio, Y. S.; Argon, A. S.; Cohen, R. E.; Weinberg, M. Toughening of isotactic polypropylene with CaCO3 particles. Polymer 2002, 43(13), 3661–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatko, Z. N.; Ashinova, A. A. Polymer Compositions for Food-Grade Films: A Review. New Technologies, 2016, (1), 30–34.

- Myalenko, D.M.; et al. The development of a modified packaging material with antioxidant properties and the study of its sanitary and hygienic characteristics. Food metaengineering, 2024, 2(1).

- Prjanichnikova, N. S.; Fedotova, O. B. Application of Qualimetric Design Techniques in the Development of Functional Coatings for Food Products. In Modern Biotechnology: Current Issues, Innovations, and Achievements, 2020, 141–143.

- Fedotova, O. B. Specific Features in the Evaluation of the Organoleptic Properties of Packaging. Milk Processing, 2017, (6), 6–9.

- Tolinski, M. . Additives for polyolefins: getting the most out of polypropylene, polyethylene and TPO. William Andrew, 2015.

- Murphy, J. Modifying specific properties: mechanical properties–fillers. Additives for Plastics Handbook 2001, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Company European Plastic “ Filler masterbatch. Cost-effective material solution for plastic enterprises”. Available online: https://europlas.com.vn/en-US/products/filler-masterbatch-4. (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Avella, M.; Cosco, S.; Lorenzo, M. L. D.; Pace, E. D.; Errico, M. E.; Gentile, G. iPP based nanocomposites filled with calcium carbonate nanoparticles: structure/properties relationships. In Macromolecular symposia 2006, 234(1), 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, S.; Taşdemir, M. Zinc oxide (ZnO), magnesium hydroxide [Mg(OH)2] and calcium carbonate (CaCO3) filled HDPE polymer composites: Mechanical, thermal and morphological properties. Marmara Fen Bilimleri Dergisi 2012, 24(4), 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, X. L.; Wei, Y. F.; Wu, L.; He, D. M.; Mo, H.; Zhou, N. L. ;... Shen, J. Studies on crystal morphology and crystallization kinetics of polyamide 66 filled with CaCO3 of different sizes and size distribution. Polymer-Plastics Technology and Engineering 2012, 51(6), 590-596.

- Khalaf, M. N. Mechanical properties of filled high density polyethylene. Journal of Saudi chemical society 2015, 19(1), 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogovsky, V. S.; Matyushin, A. I.; Shimanovsky, N. L.; Semeykin, A. V.; Kukhareva, T. S.; Koroteev, A. M. ;... Nifantyev, E. E. Antiproliferative and Antioxidant Activity of New Dihydroquercetin Derivatives. Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology, 2010, 73(9), 39–42.

- Rajandas, H.; Parimannan, S.; Sathasivam, K.; Ravichandran, M.; Yin, L. S. A novel FTIR-ATR spectroscopy based technique for the estimation of low-density polyethylene biodegradation. Polymer Testing 2012, 31(8), 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouallif, I.; Latrach, A.; Chergui, M. H.; Benali, A.; Barbe, N. FTIR study of HDPE structural changes, moisture absorption and mechanical properties variation when exposed to sulphuric acid aging in various temperatures. In CFM 2011-20ème Congrès Français de Mécanique. AFM, Maison de la Mécanique 2011, 39/41 rue Louis Blanc-92400 Courbevoie.

- Charles, J. Qualitative analysis of high density polyethylene using FTIR spectroscopy. Asian Journal of Chemistry 2009, 21(6), 4477. [Google Scholar]

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of dihydroquercetin (DHQ).

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of dihydroquercetin (DHQ).

Figure 3.

Appearance and technical specifications of the laboratory extruder SJ-28.

Figure 3.

Appearance and technical specifications of the laboratory extruder SJ-28.

Figure 4.

Appearance of modified LDPE films (grade 15803-20) with 20.0% and 40.0% CaCO₃ and 0.5% and 1.0% DHQ.

Figure 4.

Appearance of modified LDPE films (grade 15803-20) with 20.0% and 40.0% CaCO₃ and 0.5% and 1.0% DHQ.

Figure 5.

Changes in stress at break (σ) and strain at break (ε) in the longitudinal and transverse directions of HDPE films filled with CaCO₃.

Figure 5.

Changes in stress at break (σ) and strain at break (ε) in the longitudinal and transverse directions of HDPE films filled with CaCO₃.

Figure 6.

Changes in joint strength (σ) in the longitudinal and transverse directions of LDPE films filled with CaCO₃.

Figure 6.

Changes in joint strength (σ) in the longitudinal and transverse directions of LDPE films filled with CaCO₃.

Figure 7.

Changes in stress at break (σ) in longitudinal and transverse directions of LDPE films with varying CaCO3 and DHQ contents.

Figure 7.

Changes in stress at break (σ) in longitudinal and transverse directions of LDPE films with varying CaCO3 and DHQ contents.

Figure 8.

Changes in strain at break (σ) in the longitudinal and transverse directions of LDPE films with varying CaCO3 and DHQ contents.

Figure 8.

Changes in strain at break (σ) in the longitudinal and transverse directions of LDPE films with varying CaCO3 and DHQ contents.

Figure 9.

Contact angle at the surface of LDPE films modified with CaCO₃ and DHQ.

Figure 9.

Contact angle at the surface of LDPE films modified with CaCO₃ and DHQ.

Figure 10.

SEM images of film surfaces: (a) LDPE without CaCO₃; (b) LDPE with 20.0% CaCO₃; (c) LDPE with 40.0% CaCO₃.

Figure 10.

SEM images of film surfaces: (a) LDPE without CaCO₃; (b) LDPE with 20.0% CaCO₃; (c) LDPE with 40.0% CaCO₃.

Figure 11.

Comparative SEM images of film surfaces: (a) LDPE with 20.0% CaCO₃ and 0.5% DHQ; (b) LDPE with 20.0% CaCO₃ and 1.0% DHQ.

Figure 11.

Comparative SEM images of film surfaces: (a) LDPE with 20.0% CaCO₃ and 0.5% DHQ; (b) LDPE with 20.0% CaCO₃ and 1.0% DHQ.

Figure 12.

Comparative SEM images of film surfaces: (a) LDPE with 40.0% CaCO₃ and 0.5% DHQ; (b) LDPE with 40.0% CaCO₃ and 1.0% DHQ.

Figure 12.

Comparative SEM images of film surfaces: (a) LDPE with 40.0% CaCO₃ and 0.5% DHQ; (b) LDPE with 40.0% CaCO₃ and 1.0% DHQ.

Figure 13.

Surface morphology of films: 3 – LDPE + 40% CaCO₃; 7 – LDPE + 40% CaCO₃ + 0.5% DHQ; 8 – LDPE + 40% CaCO₃ + 1.0% DHQ.

Figure 13.

Surface morphology of films: 3 – LDPE + 40% CaCO₃; 7 – LDPE + 40% CaCO₃ + 0.5% DHQ; 8 – LDPE + 40% CaCO₃ + 1.0% DHQ.

Figure 14.

Surface morphology of films: 9 – LDPE + 20% CaCO₃ + 1.0% DHQ; 12 – LDPE + 20% CaCO₃ + 0.5% DHQ.

Figure 14.

Surface morphology of films: 9 – LDPE + 20% CaCO₃ + 1.0% DHQ; 12 – LDPE + 20% CaCO₃ + 0.5% DHQ.

Figure 15.

FTIR spectra, where: 3 – LDPE + 40% CaCO₃; 7 – LDPE + 40% CaCO₃ + DHQ 0.5%; 8 – LDPE + 40% CaCO₃ + DHQ 1%.

Figure 15.

FTIR spectra, where: 3 – LDPE + 40% CaCO₃; 7 – LDPE + 40% CaCO₃ + DHQ 0.5%; 8 – LDPE + 40% CaCO₃ + DHQ 1%.

Figure 16.

FTIR spectra of samples: 9 – LDPE + 20% CaCO₃ + 1.0% DHQ; 12 – LDPE + 20% CaCO₃ + 0.5% DHQ.

Figure 16.

FTIR spectra of samples: 9 – LDPE + 20% CaCO₃ + 1.0% DHQ; 12 – LDPE + 20% CaCO₃ + 0.5% DHQ.

Table 1.

Technical specifications of the CaCO₃ masterbatch used.

Table 1.

Technical specifications of the CaCO₃ masterbatch used.

| Characteristic |

Value |

| Appearance |

White granules |

| Granule size, mm |

3-4 |

| Whiteness, % |

> 97 |

| Bulk density, g/cm3

|

1,9 |

| MFR (190°С), g/10 min |

3 |

| СаСО3 content, % |

80.0 |

| Base polymer content (LDPE), % |

20.0 |

| Mean particle size of СаСО3, µm |

2.0 |

| Moisture content, % |

< 0.15 |

Table 2.

Technical characteristics of dihydroquercetin.

Table 2.

Technical characteristics of dihydroquercetin.

| Parameter |

Description |

| Compound name |

Dihydroquercetin |

| Raw material |

Dahurian larch Latix Gmelinii (Rupr.) Rupr |

| Plant part used |

Root wood |

| Country of origin |

Russia |

| Substance class |

Bioflavonoids |

| Composition |

Dihydroquercetin >90% |

| Other flavonoids |

Aromadendrin, eriodictyol, quercetin, taxifolin, pinocembrin, total content <10% |

| Appearance |

Fine powder |

| Color |

White to pale yellow |

| Solubility |

Soluble in ethanol, hydroalcoholic solutions, ethyl acetate; slightly soluble in water; insoluble in chloroform, ether, and benzene |

| Moisture content |

<2% |

Table 3.

Main characteristics of LDPE.

Table 3.

Main characteristics of LDPE.

| Characteristics |

Method |

Value |

| Flow index of melt |

GOST 11645 |

2.0g/10 min |

| Density |

GOST 15139 |

0.92 g/cm3

|

| Stress at yield |

GOST 11262 |

9.3 MPa |

| Stress at break |

GOST 11262 |

11.3 MPa |

| Extractable substances content |

GOST 26393 |

0.4% |

| Odor intensity from aqueous solution |

GOST 22648 |

Not more than 1.0 point |

Table 4.

Main characteristics of the technical specifications of the laboratory extruder.

Table 4.

Main characteristics of the technical specifications of the laboratory extruder.

| Characteristic |

Value |

| Screw diameter |

28 mm |

| Maximum film bubble width |

200 mm |

| Die (film die) diameter |

40 mm |

| Film thickness |

0.010-0.050 |

| Length-to-diameter ratio |

34:1 |

| Number of temperature control zones |

4 |

Extruder zone temperatures:

Zone 1

Zone 2

Zone 3 |

145°С

150°С

153 °С |

| Zone 4 |

157°С |

Table 5.

Results of experimental assessment of the water contact angle on the surface of LDPE films modified with CaCO₃ and DHQ.

Table 5.

Results of experimental assessment of the water contact angle on the surface of LDPE films modified with CaCO₃ and DHQ.

| Indicator |

LDPE film with varying СаСО3 and DHQ contents** |

| №1 |

№2 |

№3 |

№4 |

№5 |

№6 |

№7 |

№8 |

№9 |

| Mean CA (avg) [°]* |

85.35 |

82 |

84.34 |

89.54 |

90.76 |

86.07 |

107.97 |

114.4 |

129.84 |

| Mean CA (l) [°]* |

85.57 |

81.59 |

84.13 |

89.55 |

90.62 |

85.82 |

107.86 |

114.4 |

129.93 |

| Mean CA (r) [°]* |

85.13 |

82.41 |

84.55 |

89.53 |

90.91 |

86.33 |

108.08 |

114.4 |

129.75 |

| Mean triple-phase point (l) [mm]* |

7.5 |

7.7 |

7.6 |

7.8 |

7.6 |

7.6 |

7.6 |

9.1 |

8.8 |

| Mean triple-phase point (r) [mm]* |

11 |

11.5 |

11.4 |

11.2 |

11.4 |

11.3 |

10.8 |

12.2 |

11.2 |

| Mean diameter [mm] |

3.52 |

3.8 |

3.83 |

3.42 |

3.78 |

3.75 |

3.17 |

3.1 |

2.39 |

| Mean volume [µL] |

9.63 |

10.99 |

11.90 |

9.86 |

13.86 |

11.88 |

13.56 |

14.75 |

12.16 |

* Mean CA (avg) – the average value of the left and right contact angles.

Mean CA (l) – the average value of the left angle.

Mean CA (r) – the average value of the right angle.

Triple-phase point – the point at which the solid, liquid, and vapor phases are in contact.

Mean triple-phase point (l) – average value of the left three-phase points.

Mean triple-phase point (r) – average value of the right three-phase points.

** №1 – LDPE; №2 – LDPE+0.5DHQ; №3 – LDPE+1.0DHQ; №4 – LDPE 20; №5 – LDPE 20+0.5DHQ; №6 – LDPE 20+1.0DHQ; №7 – LDPE 40; №8 – LDPE 40+0.5DHQ; №9 – LDPE 40+1.0DHQ |

Table 6.

Statistical parameters of surface roughness for the films.

Table 6.

Statistical parameters of surface roughness for the films.

| Parameter |

Sample number |

| 3 |

7 |

8 |

| Average roughness (Ra), µm |

0.178 |

0.165 |

0.133 |

| Average maximum depth of surface pores (Rvm), µm |

0.517 |

0.446 |

0.659 |

| Average maximum peak height of roughness (Rpm), µm |

1.728 |

1.003 |

1.033 |

Table 7.

Statistical parameters of surface morphology for samples with reduced CaCO₃ content.

Table 7.

Statistical parameters of surface morphology for samples with reduced CaCO₃ content.

| Parameter |

Sample number |

| 9 |

12 |

| Average roughness (Ra), µm |

0.122 |

0.077 |

| Average maximum depth of the roughness valley (Rvm), µm |

0.326 |

0.251 |

| Average maximum peak height of roughness (Rpm), µm |

0.919 |

0.633 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).