3.2. Feature analysis of demagnetization fault

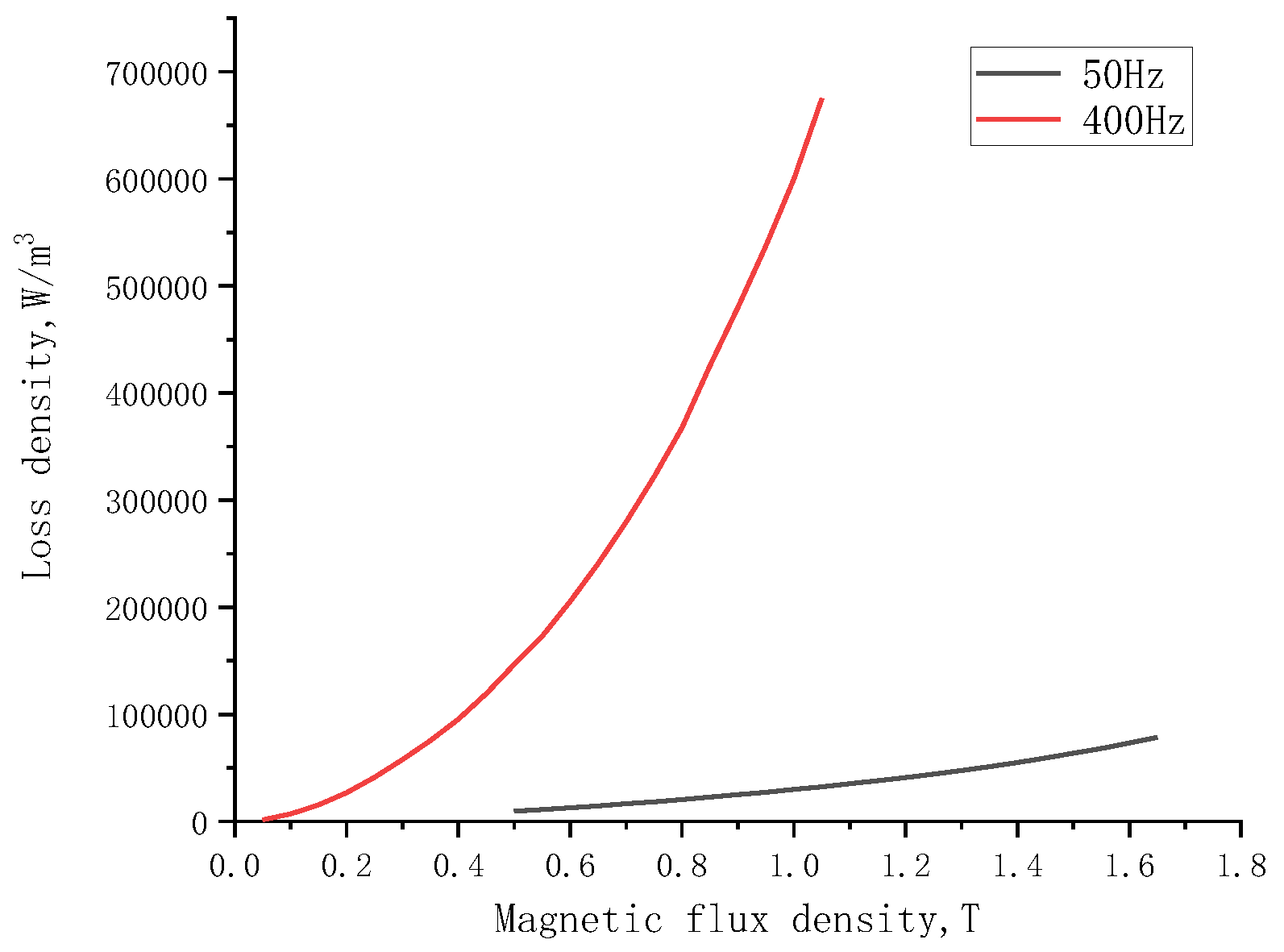

The remanence and coercivity of a permanent magnet decrease with the increase of temperature. The demagnetization rate Dem of a permanent magnet can be shown in equation(7).

Br is the initial remanence and Br1 is the remanence under the current demagnetization. Most of the magnetic energy is stored in the air gap for the large magnetic reluctance. Therefore, the magnetic density of the air gap becomes an important target to measure the magnetic performance of the motor. Fundamental magnetic flux per pole is shown as equation(8):

b' is the per unit value of the magnetic flux density under the current working condition of the permanent magnet. S is the cross-sectional area of each pole. ε0 is the no-load magnetic leakage coefficient. No-load air gap magnetic density B0 is shown in equation(9).

α is the polar arc coefficient. τ is the pole pitch. lef is the length of the core. As shown in formula and , it can be seen that the fundamental flux of each pole decreases due to the reduction of remanence when demagnetization faults occur, which resulting in the decrease of the air gap magnetic density and the output performance of the motor.

The input electric power P1 can be expressed as:

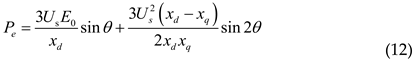

PCu is the copper loss. Electromagnetic power Pe can be expressed as:

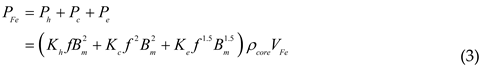

PFe is the iron loss. PΩ is the mechanical loss. P2 is the output mechanical power on the shaft. Pe can also be expressed as:

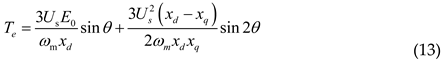

Us is the RMS value of the phase voltage. xq and xd are the reactance of quadrature and direct axis respectively. ωm is the mechanical angular velocity. θ is the power angle. For the interior PMSM, the electromagnetic torque Te of the motor is divided into basic torque and reluctance torque because of the inequality of quadrature and direct axis reactance. The expression of Te is as follows:

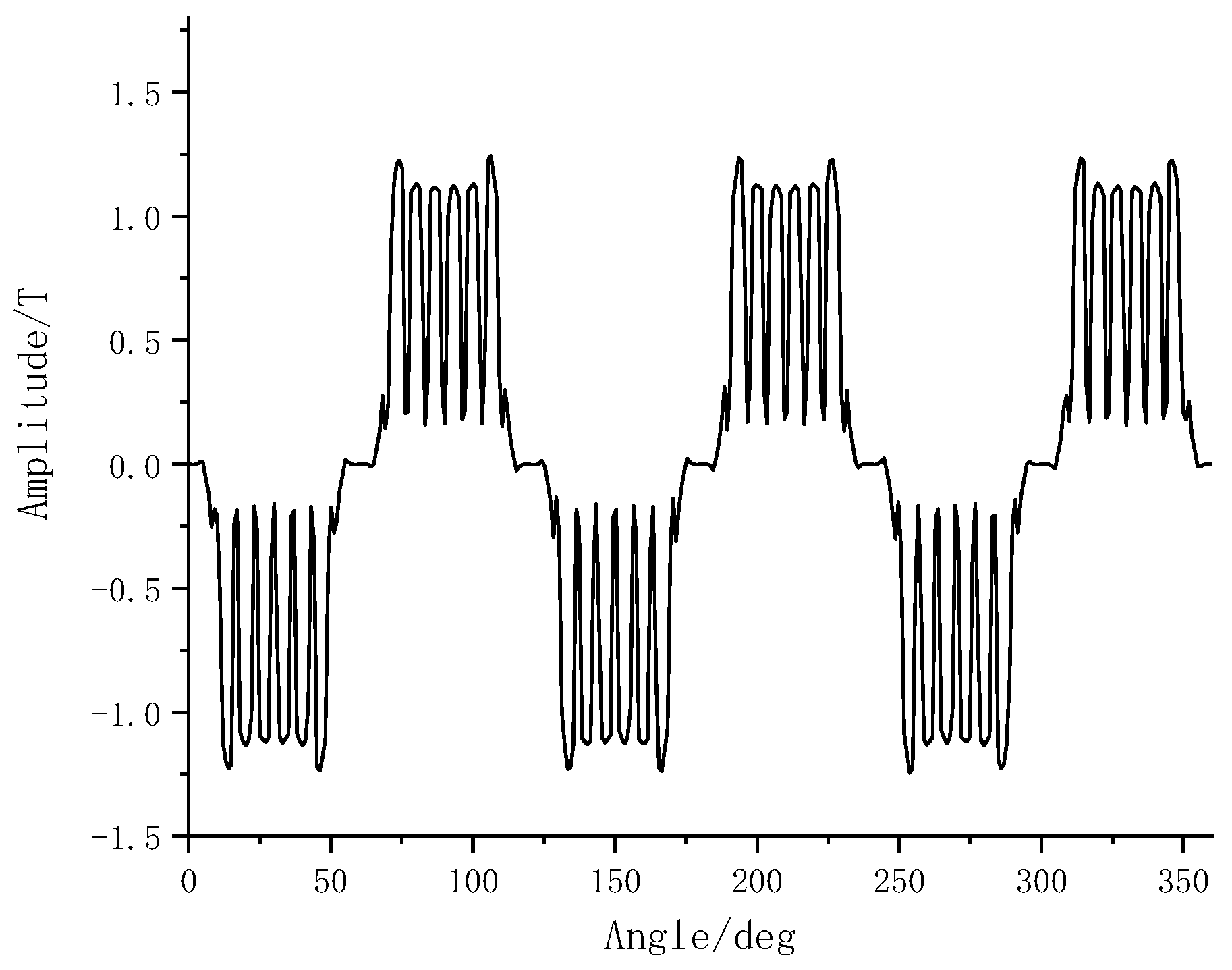

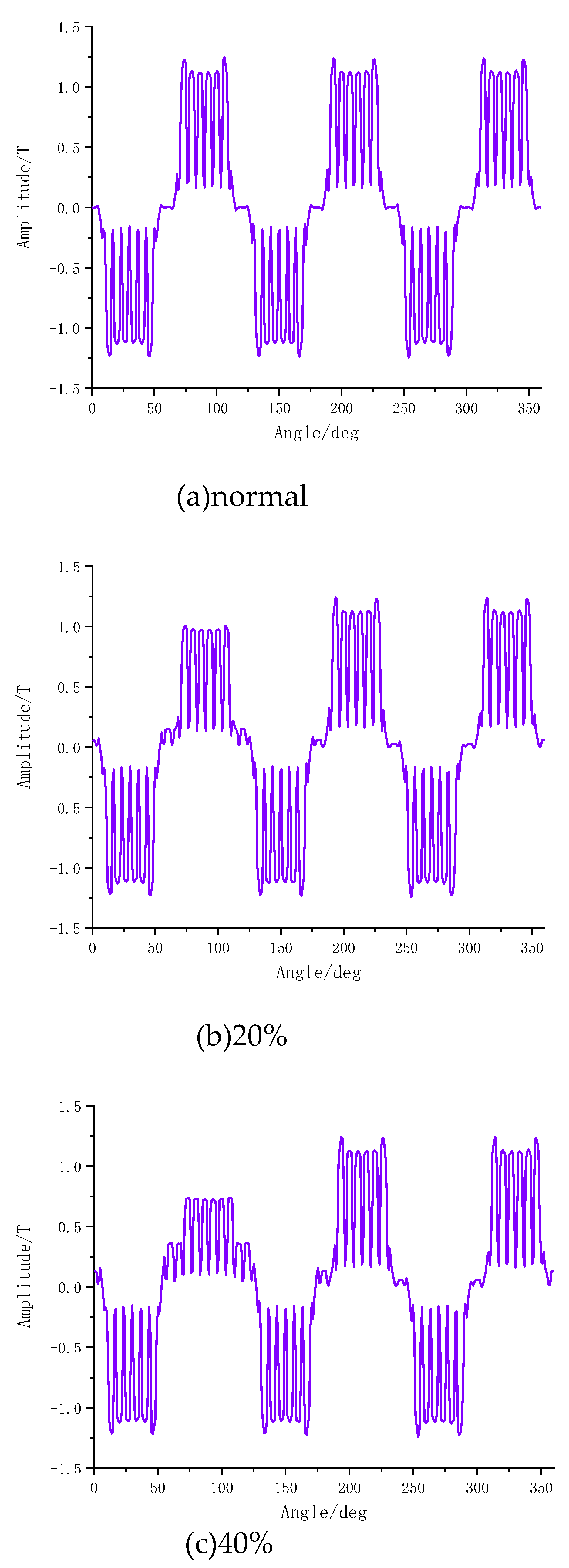

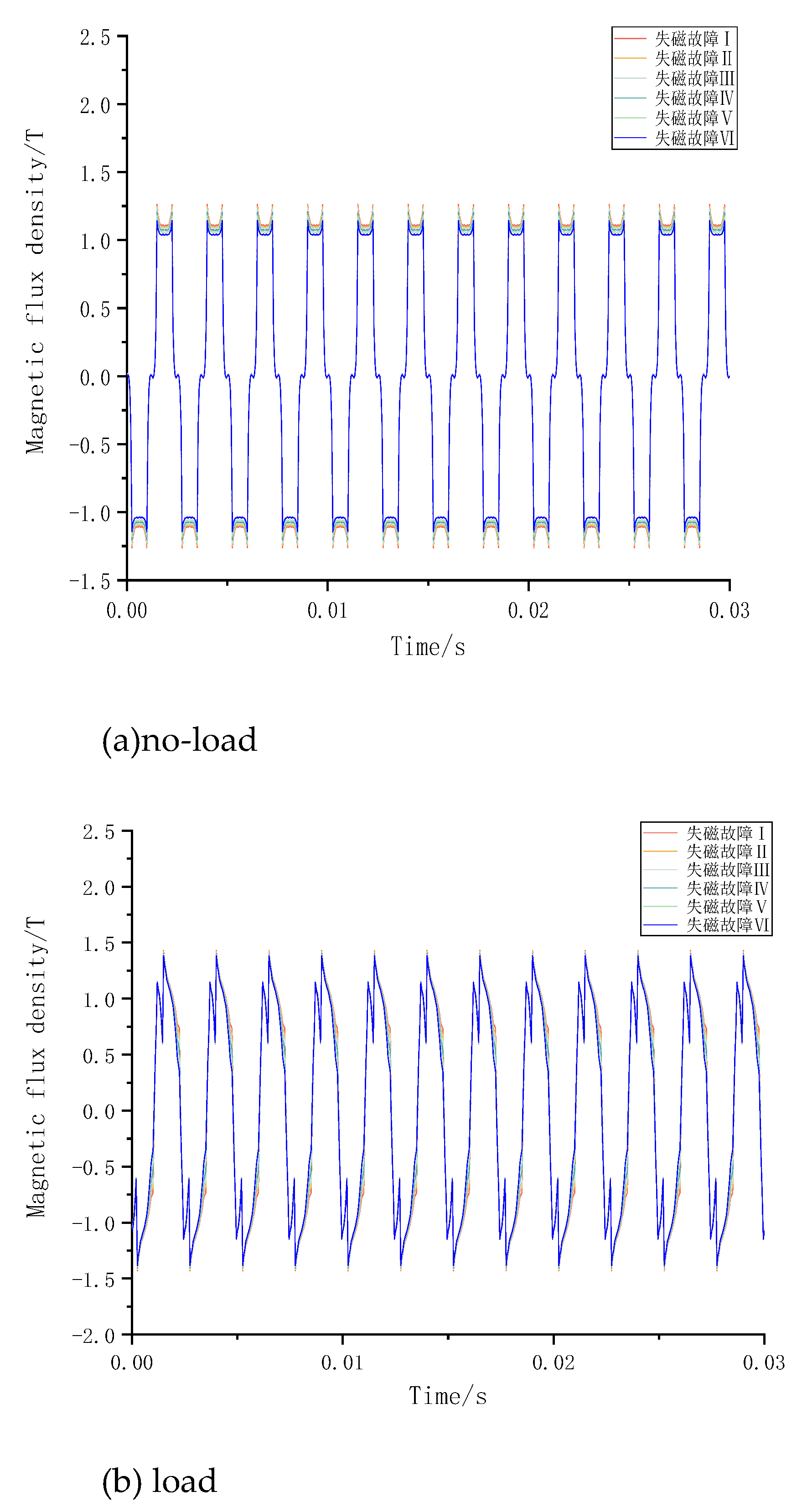

When the motor operates under no-load conditions, the air-gap magnetic field mainly consists of permanent magnet flux. The amplitude and waveform of the air-gap magnetic flux density are directly determined by the remanence of the permanent magnet. When the motor operates under load, the air-gap magnetic field consists of the permanent magnet field and the field generated by the windings. Due to the winding field, the impact of demagnetization faults on the air-gap magnetic field is relatively weakened.

Figure 16 illustrates the no-load and load air-gap magnetic flux density waveforms under six levels of overall demagnetization faults.

When temperature of the motor rises to 120℃, that is, the overall demagnetization fault Ⅵ occurs, the air gap magnetic density of both conditions decreases to a certain extent and the reduction is more obvious under no-load operation.

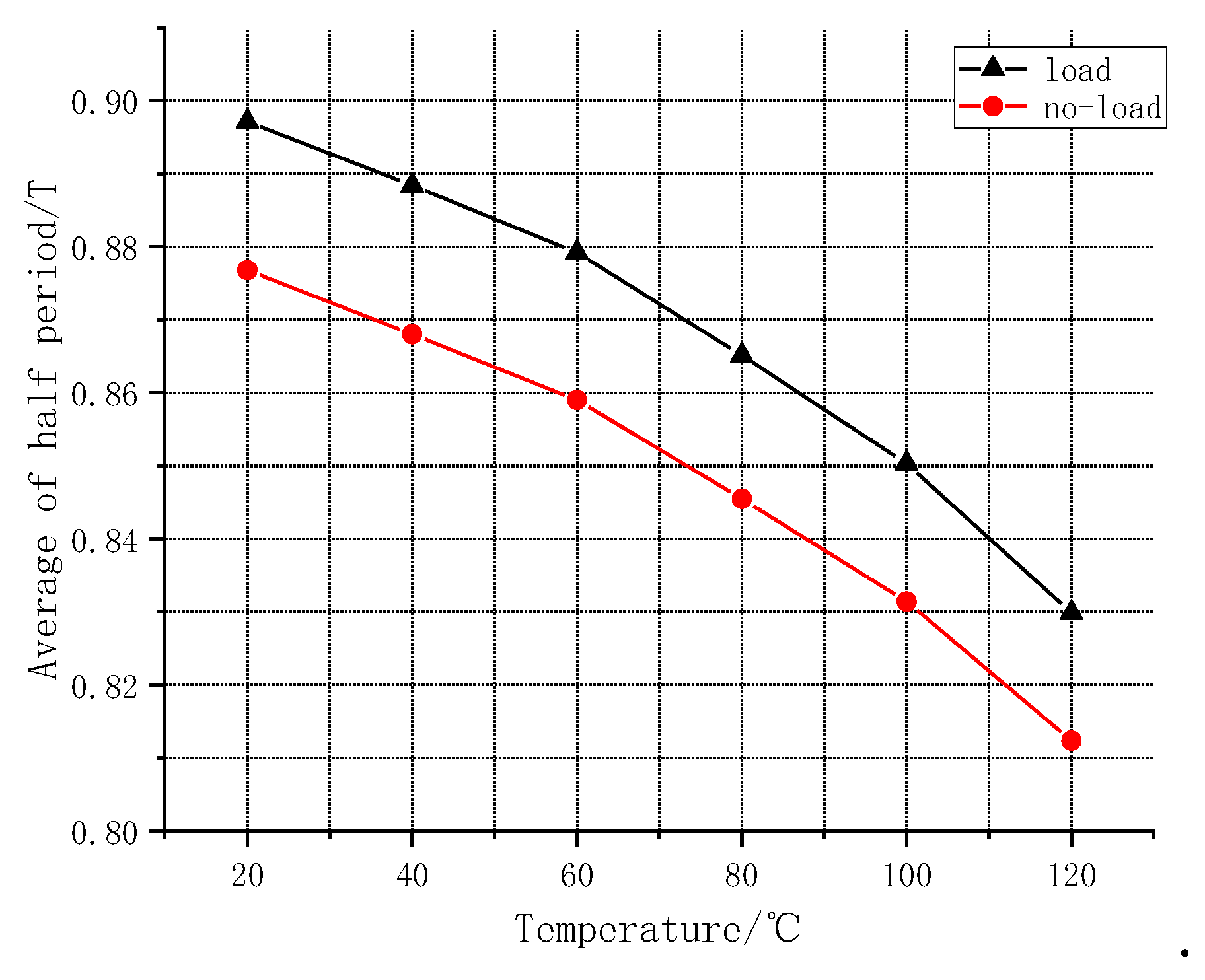

Figure 17 can be obtained by intercepting a positive half period of no-load and load air gap magnetic density and taking its average value. It can be seen from

Figure 17 that under no-load and load conditions, the mean value of magnetic density decreases with the increase of demagnetization degree. Under the influence of winding magnetic field, the average magnetic density of air gap is larger.

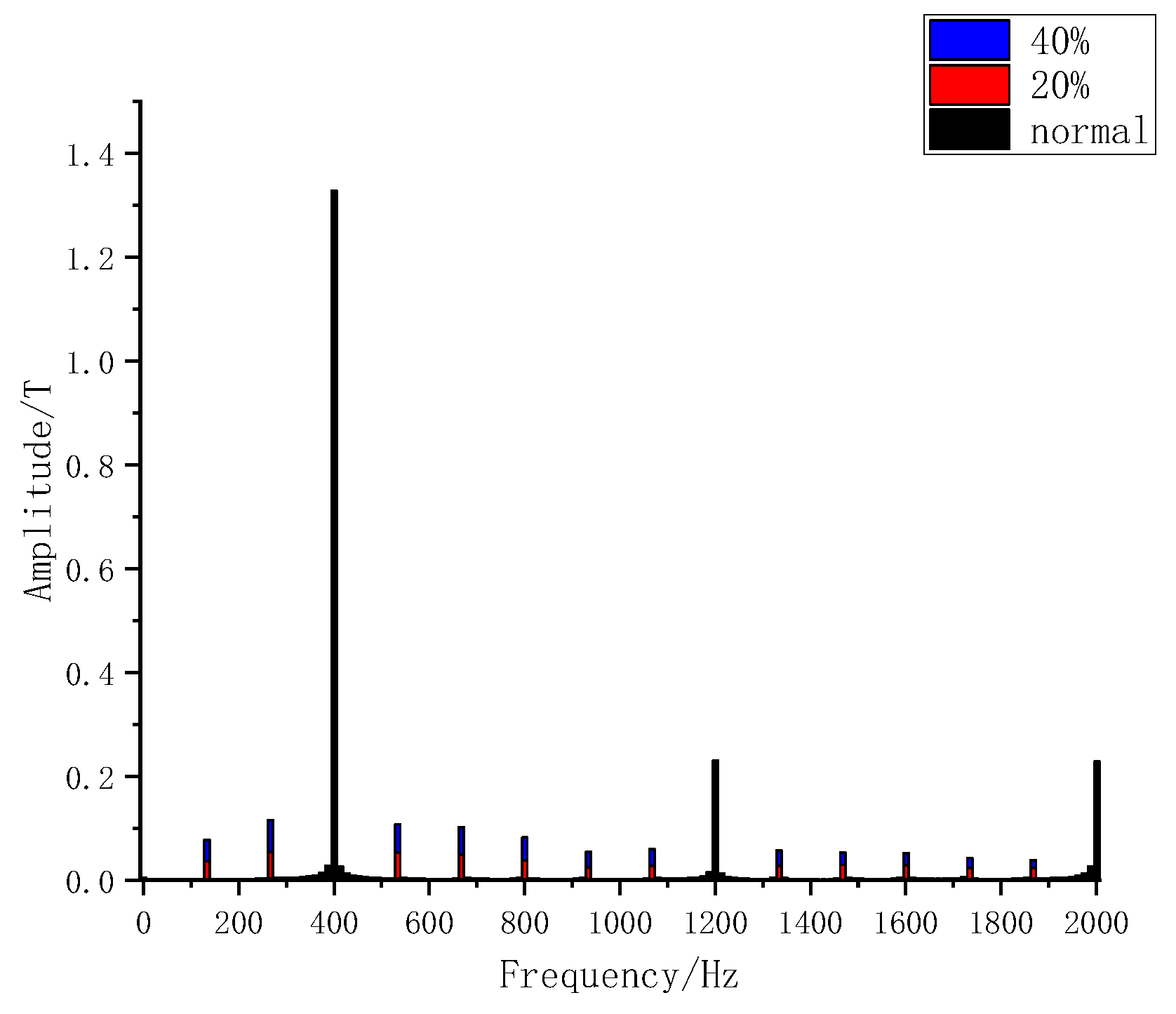

The frequency components of the airgap magnetic extracted from six kinds of overall demagnetization faults are shown in

Table 8. With the increase of demagnetization degree, the fundamental amplitude of the air gap magnetic density decreases significantly and other odd harmonics also decrease to varying degrees except the ninth harmonic.

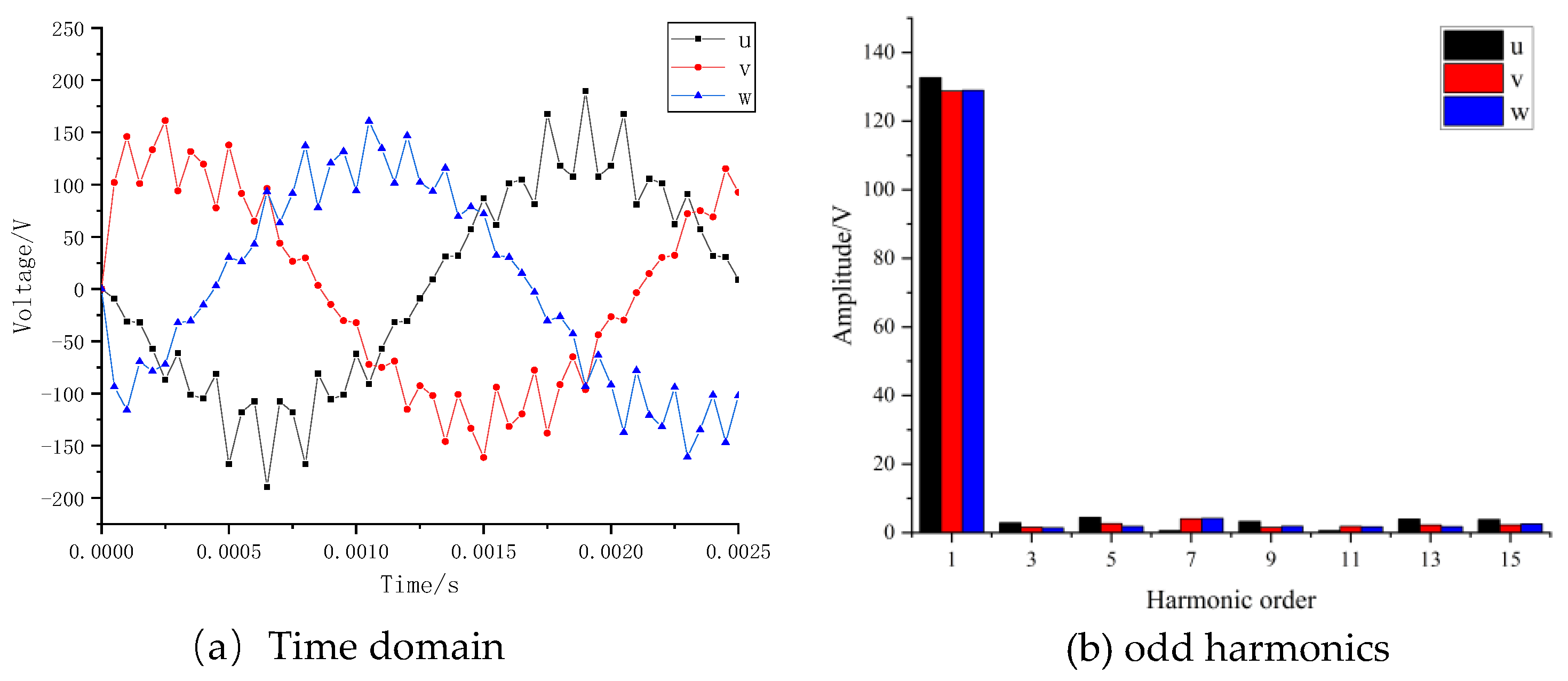

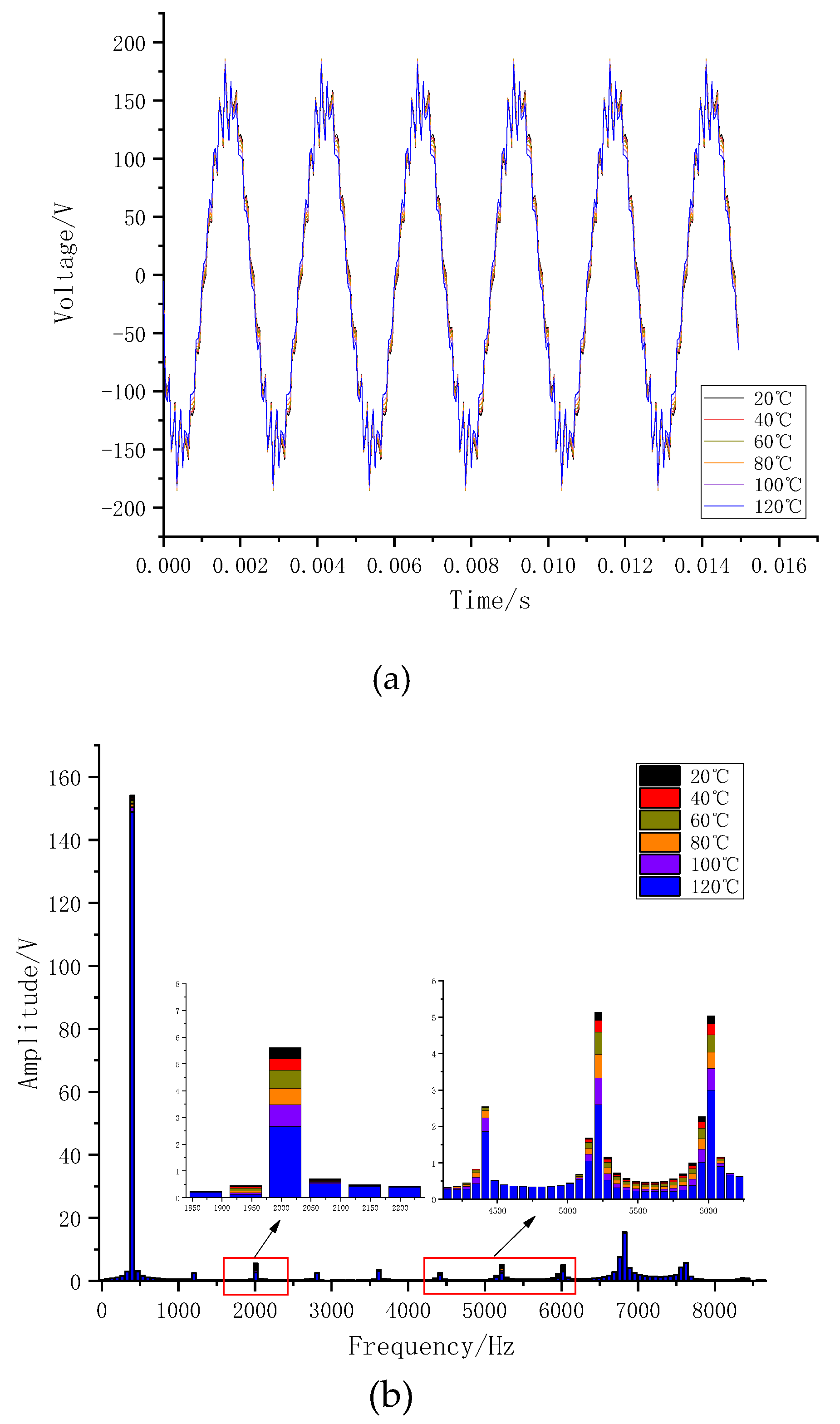

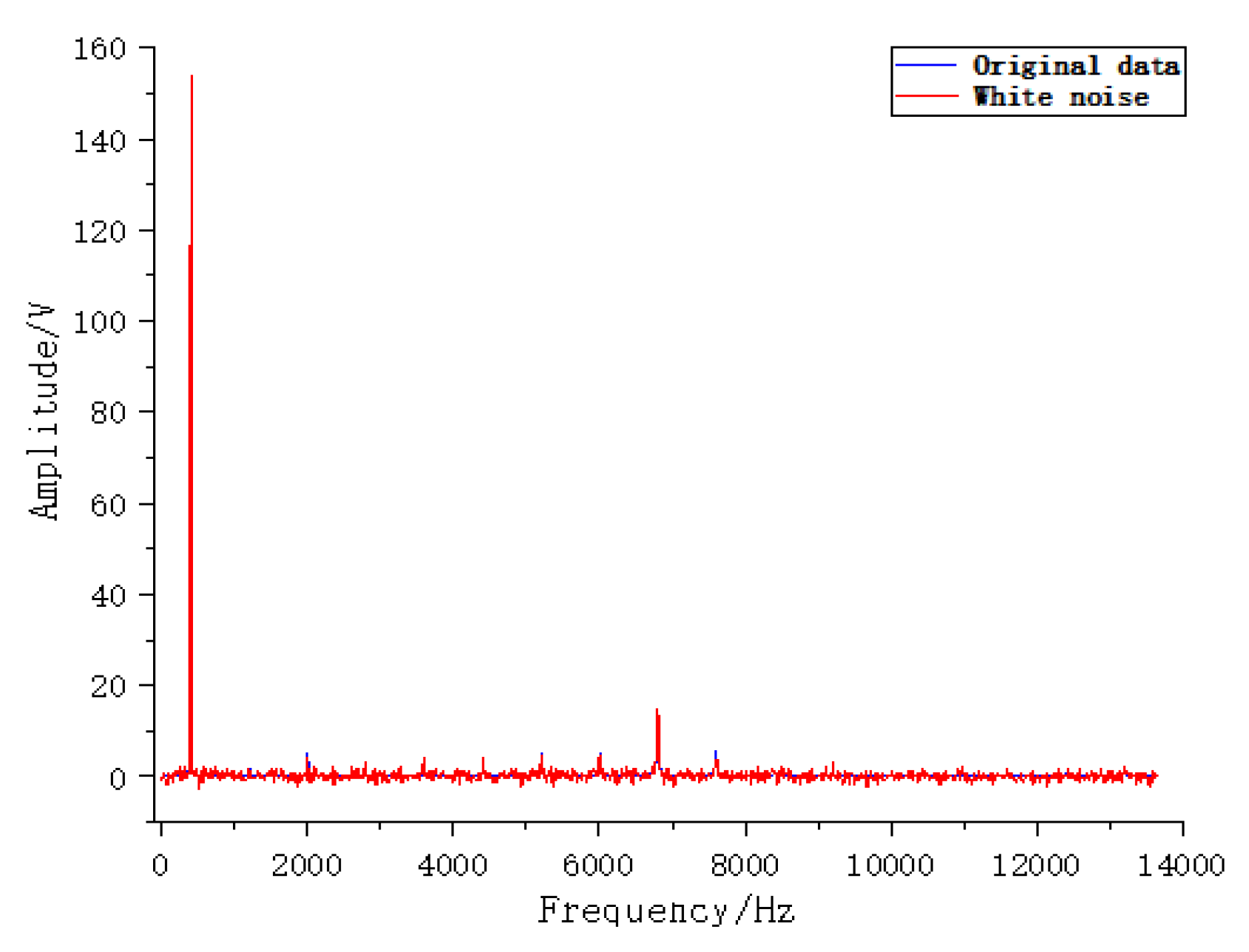

The three-phase voltage shows a decreasing trend as temperature rises, as shown in

Figure 18. After extracting the single-phase voltage for FFT analysis, the amplitude of the fundamental frequency component decreases significantly, while the amplitudes of other frequency components, such as the 5th, 13th, and 15th harmonics, exhibit significant variations. At lower temperatures, the voltage does not decrease markedly and exhibits a nonlinear variation with increasing temperature.

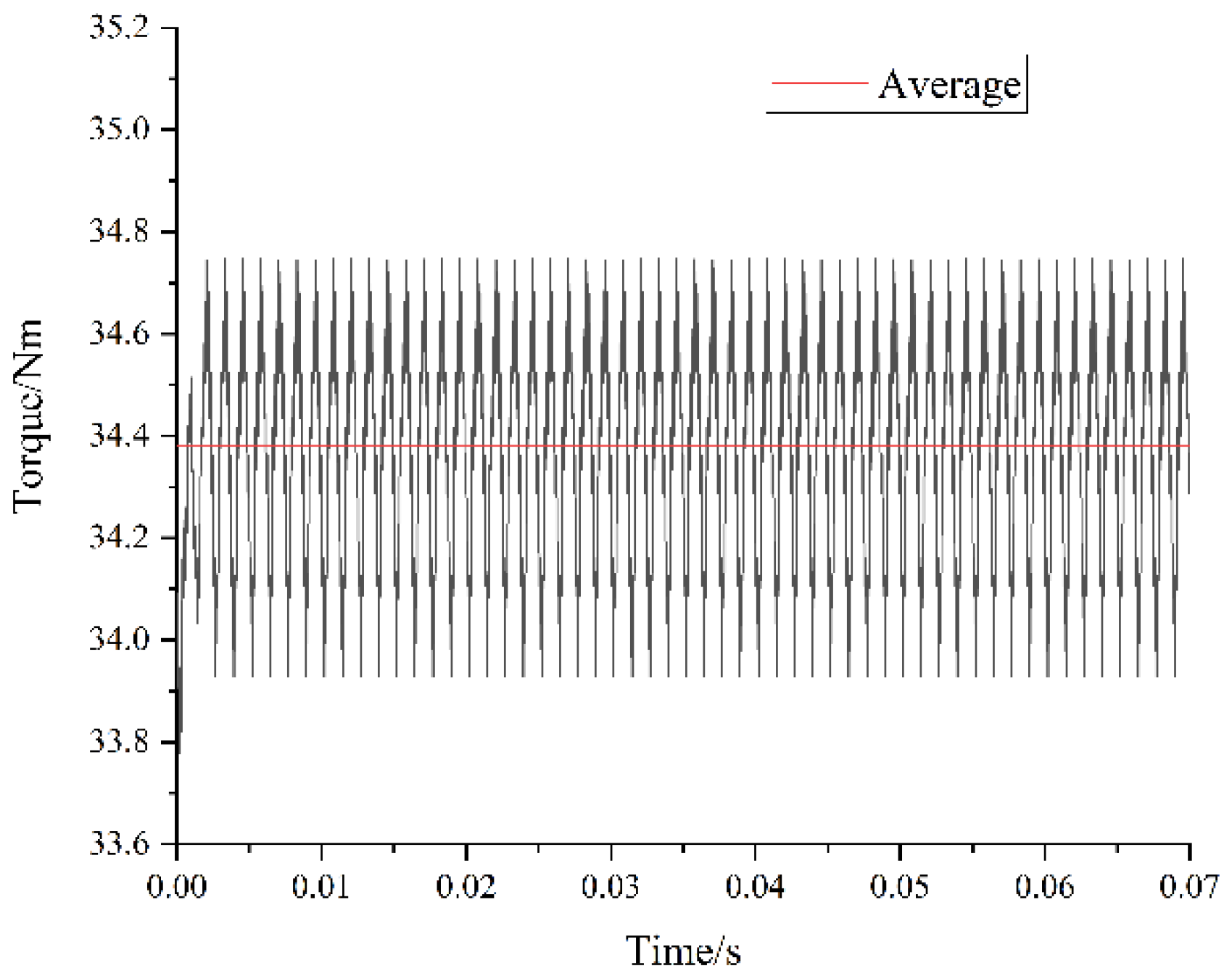

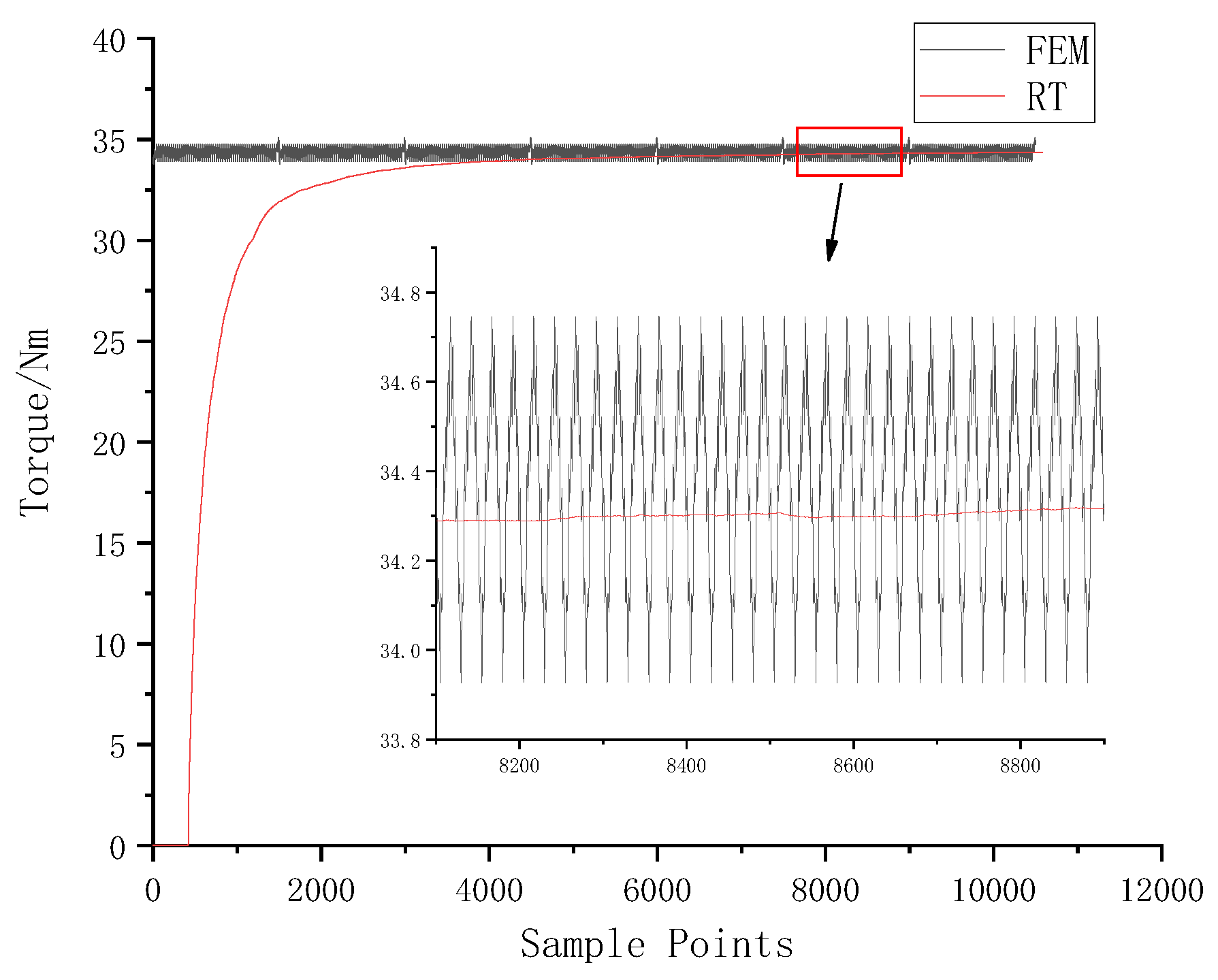

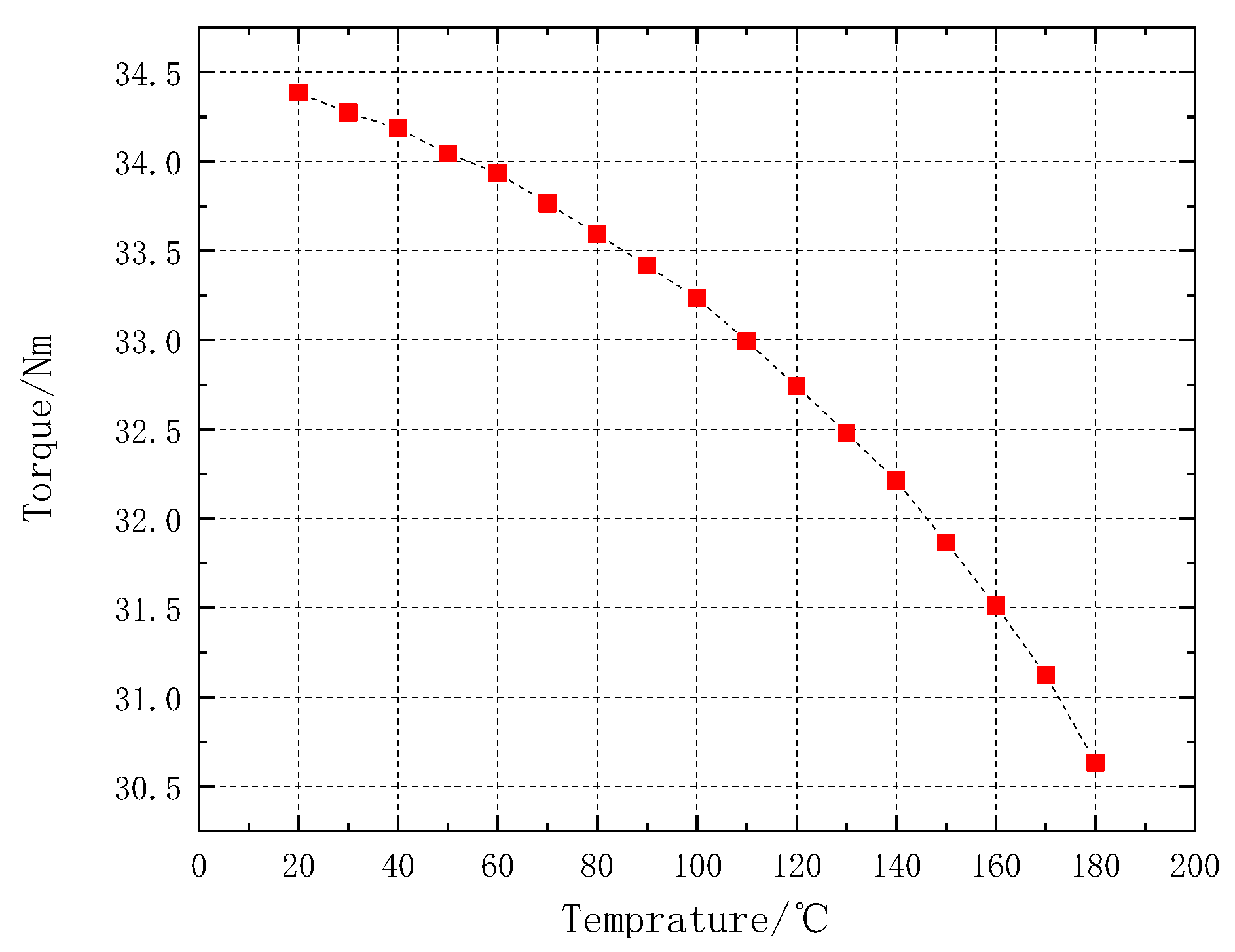

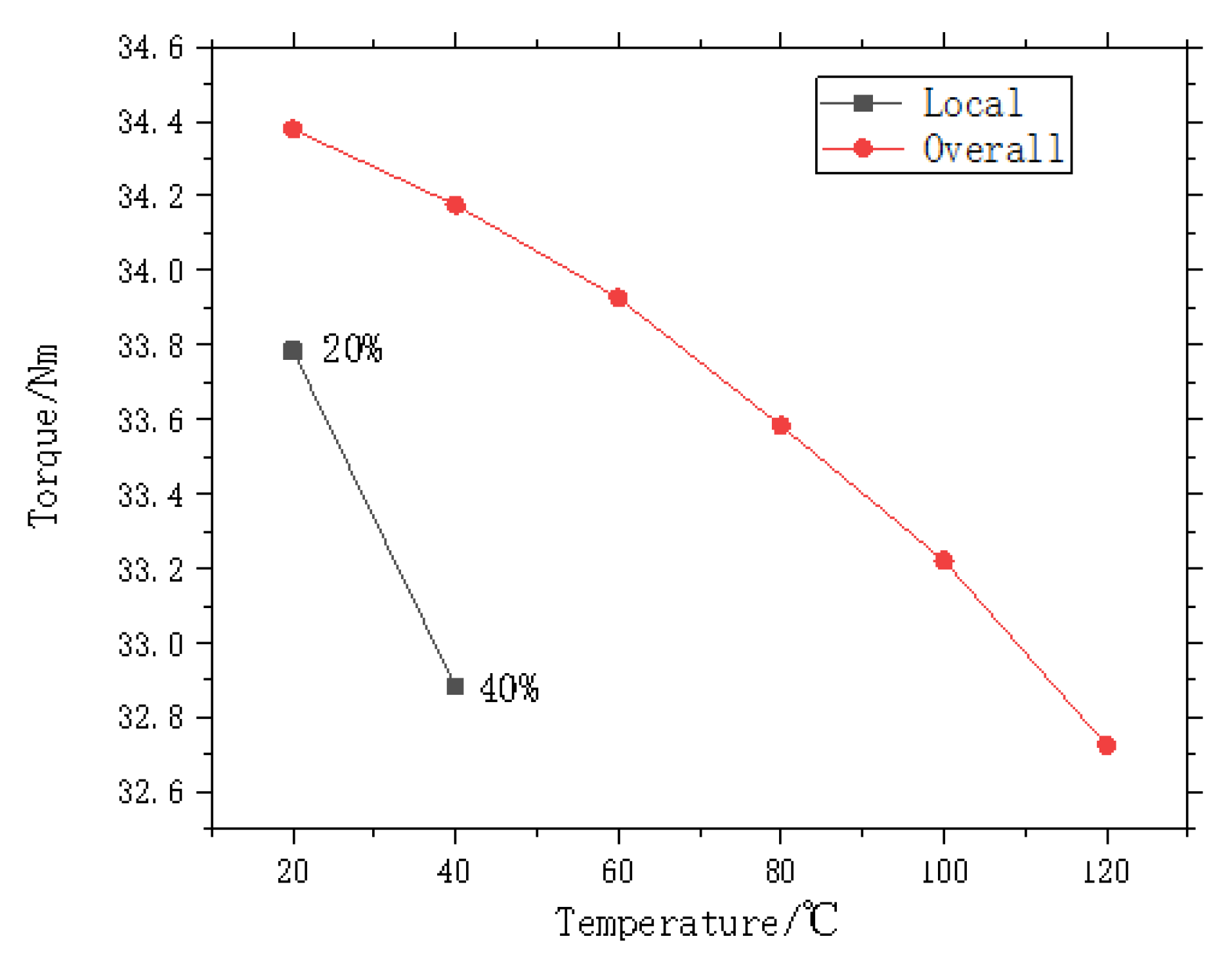

Overall demagnetization faults lead to a decrease and fluctuation in output torque. The effect is approximately linear within a relatively low temperature range and exhibits an accelerated decline as temperature increases, as shown in

Figure 19.

Local demagnetization faults destroy the symmetry of the air-gap magnetic field, causing the magnetic density to generate several specific frequency harmonics. These harmonics can be expressed as:

fd is the characteristic frequency of local demagnetization faults. f is the fundamental frequency. p is the number of pole-pairs. k is a positive integer.

Taking the magnetic density of the stator as an example, the characteristic frequency components of local demagnetization faults are analyzed. According to the equation, several components are generated around the fundamental frequency.

Figure 20 illustrates the details, and specific data are presented in

Table 9. For different values of k, the characteristic components in equation (14) are 133.33, 266.67, 533.33, 666.67, 800, 933.33, etc. The calculated results agree with the tabulated data.

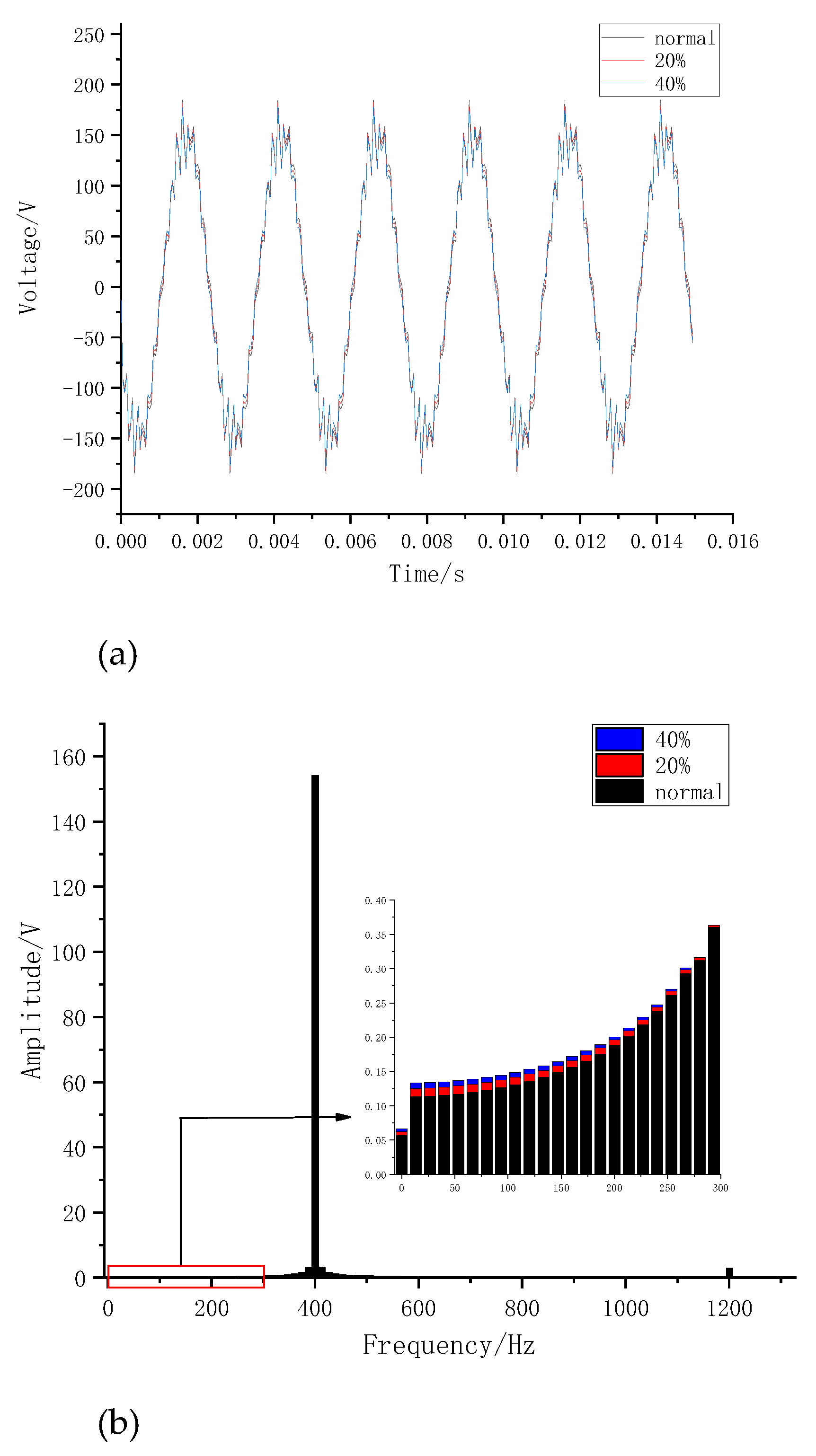

The characteristic frequency of local demagnetization faults can be used to distinguish overall demagnetization faults from local demagnetization faults. This characteristic frequency introduces harmonic components into the three-phase voltage. The time and frequency characteristics of the single-phase voltage are shown in

Figure 21. Local demagnetization faults lead to characteristic components in the three-phase voltage. Therefore, local demagnetization faults can be diagnosed by extracting the stator voltage frequency and analyzing the amplitudes of specific frequency components.

On account of the asymmetry in the magnetic density distribution under local demagnetization faults, it is deduced that the motor’s voltage and torque will be affected, thereby producing harmonics. Local demagnetization faults weaken the magnetic field generated by the permanent magnets and cause a reduction in output torque, potentially leading to a mismatch between the motor output torque and the load torque. Such asymmetry may also result in eccentric faults when the magnetic pull on the rotor becomes unbalanced. The output torque under demagnetization faults is shown in

Figure 22.

As can be seen from

Figure 22, within the range of demagnetization studied in this paper—specifically 20% and 40% demagnetization of a magnetic pole—local demagnetization faults cause greater torque loss than overall demagnetization faults. A rapid decline in torque intensifies the imbalance on the motor’s output shaft, resulting in deceleration, strong current pulsations, and mechanical vibrations, all of which threaten the structural safety of the motor.

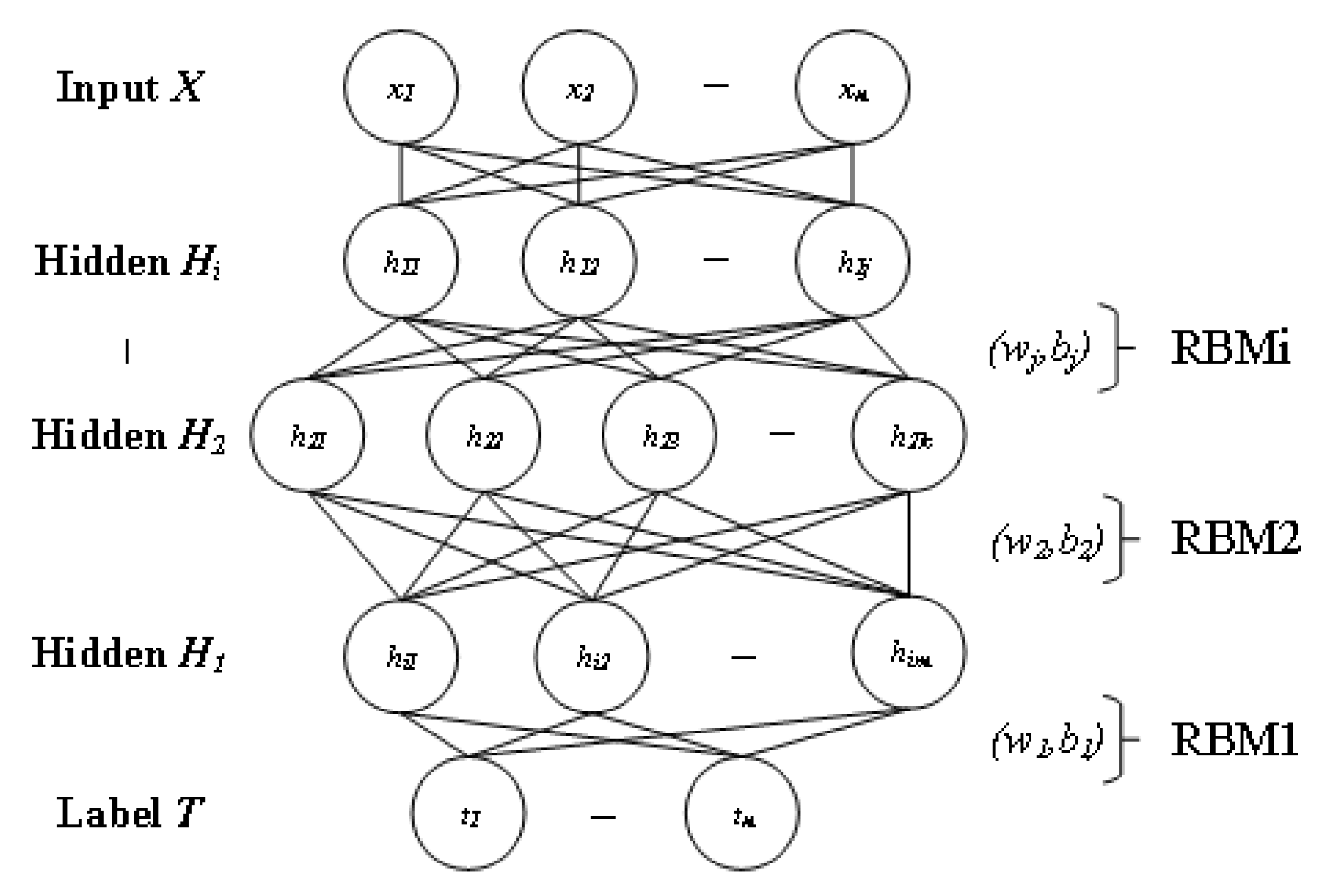

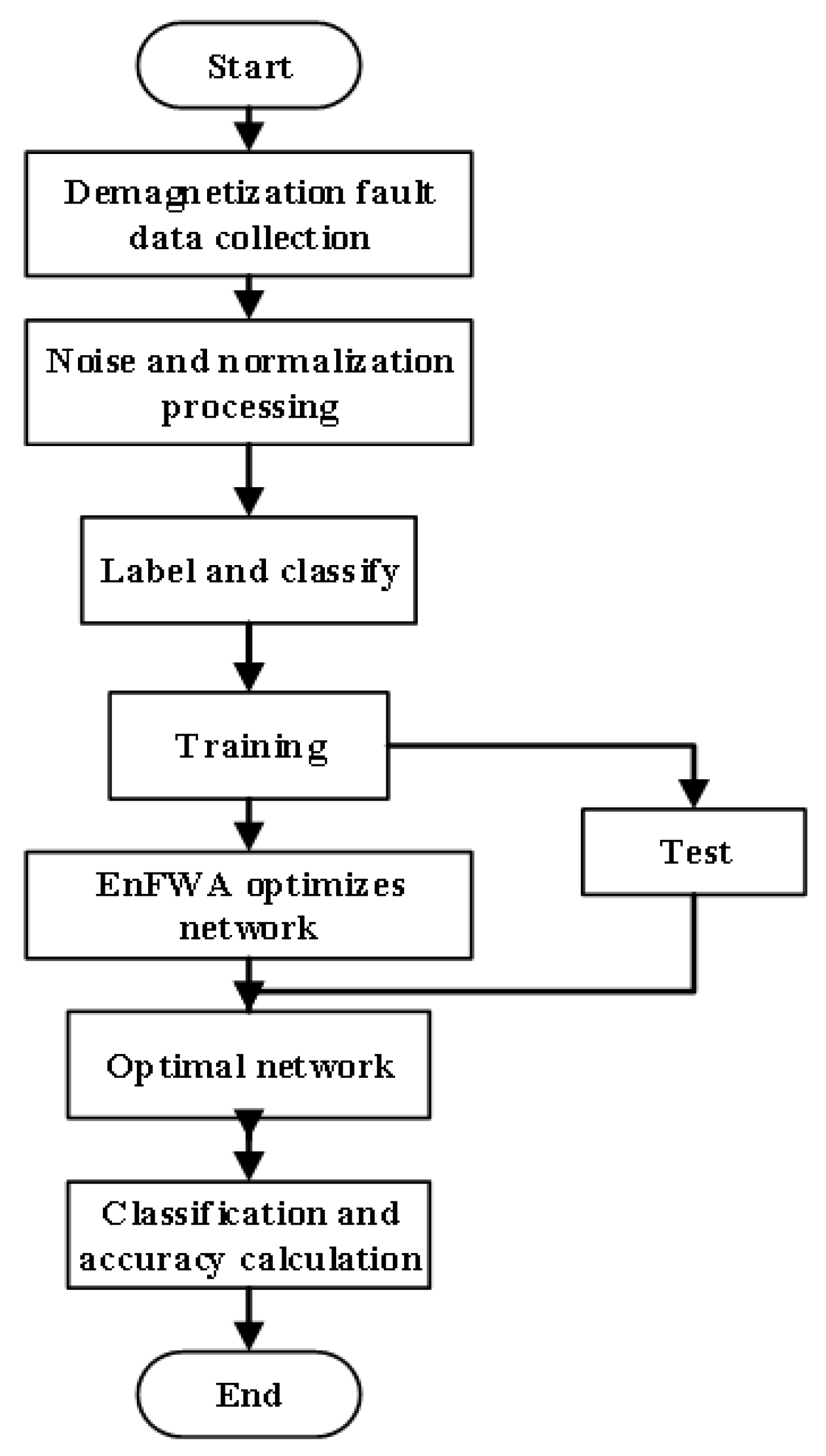

The preceding analyses identified the characteristic features of demagnetization faults and clarified their impact on motor behavior. To translate these insights into an effective fault diagnosis, a systematic framework is required to extract representative features, ensure robustness against interference, and achieve reliable classification. The following section develops such a diagnostic framework and evaluates its performance.