1. Introduction

Human–Computer Interaction [

1] studies how to design systems so that they are usable and accessible for everyone, in accordance with the principles of Universal Design [

2]. Among interactive systems, special attention is given to those aimed at teaching, and in particular, at teaching programming [

3].

According to [

4], the teaching of programming at an early age should be a priority. This is because, in early childhood education, children develop the foundations of computational thinking [

5], and logical thinking, which enable them to solve problems, design projects, and communicate ideas [

6,

7].

The resources commonly used for teaching programming in early childhood education include robots such as Cubetto [

8,

9], Bee-Bot [

10], Tale-Bot [

11], and KUBO [

12].

At the software level, there is a simplified version of Scratch [

13] called Scratch Jr. [

14], which includes fewer blocks that are mainly focused on movement, simple dialogue, and repetition—fundamental concepts typically introduced between the ages of 3 and 7.

Neurotypical children—that is, those who follow a developmental trajectory consistent with the timeframes studied in psychology—are generally able to learn Scratch Jr. directly within the application, with guidance from their teachers [

15].

However, in the case of children with a disability or learning disorder, the teaching of programming requires additional support and curricular adaptations, as is done in other subjects, following the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) [

16].

In the literature, there are examples of Scratch Jr. versions such as Scratch Jr. Tactile, a non-digital, tangible version designed to address diversity [

17]. There are also examples of tools developed to teach programming to students with autism [

18,

19], intellectual disabilities [

20] or visual impairments [

21].

On the other hand, it is worth highlighting the existence of interactive systems that rely on the use of a Pedagogical Conversational Agent (PCA)—that is, an internal or external representation within the system in the form of an animal, robot, or human [

22]—which serves as a guide and support for teaching, taking on the role of teacher, student, or companion.

However, there are no examples in the literature of teaching programming to neurodivergent students with the support of this type of agent. There are, however, examples of agents that have been shown to improve both the performance and satisfaction of neurotypical students [

23]. Improvements have even been reported in students’ emotional capacity when learning programming with a PCA incorporating mindfulness [

24].

In our previous work, teachers were consulted about the possibility of creating an interactive system to train children—both neurotypical and neurodivergent—in the use of Scratch Jr., according to their preferences and needs [

25].

The difficulty of identifying the needs of some non-verbal neurodivergent children or those with limited attention spans to complete a questionnaire independently was taken into account. This is especially relevant considering that, at these ages, executive functions are generally not yet fully developed, nor are reading and writing skills.

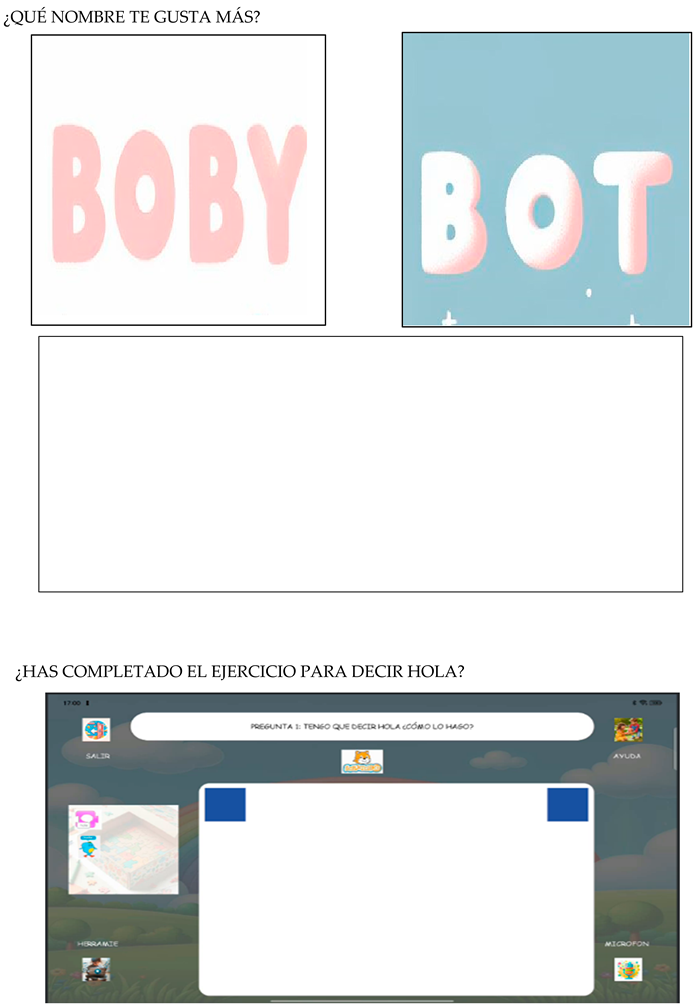

Therefore, a User-Centered Design process [

1] was initiated to begin the development of a Pedagogical Conversational Agent (PCA), which the children decided to name Boby, in the role of student, to train in the use of Scratch Jr., taking into account classroom diversity.

The first functional prototype of Boby was brought to the classroom during the 2024–2025 school year at a school in Madrid, Spain. It was tested by 50 children, aged 6 to 7, both neurotypical and neurodivergent, and the results of the usability validation are presented in this article.

Additionally, this article also aims to address research questions such as whether children who are accustomed to using technology will find interaction with Boby more satisfying (beyond their neurotypical or neurodivergent status) and taking into account their level of digital competence.

Another issue raised is the relationship between block-based games and interaction with Boby, considering that Scratch Jr. is a block-based language and that not all children may enjoy playing with blocks.

Finally, the aim is to explore which factors influence children’s ability to complete activities with Boby and the outcomes they achieve when interacting with this type of system before beginning to use Scratch Jr.

The article is structured into five sections:

Section 2 presents the related state of the art,

Section 3 describes the results obtained from the conducted experience,

Section 4 presents the materials and methods of the experiment,

Section 5 presents the results,

Section 6 presents the discussion of the results, and Section 7 ends the paper with the main conclusions and future lines of work.

2. State of the Art

Research on teaching programming in early childhood education is still in its early stages [

26,

27,

28]. This section reviews the published work from both methodological perspectives and practical implementations. It is also important to note that, since the children are between 3 and 6 years old, they are generally not expected to create programs as in primary education. Instead, the focus is usually on coding simpler tasks [

29], such as performing sequences of movements or planning routes. In this planning—moving from one point to another, for example, on a grid—basic concepts such as conditionals (going left or right) or loops (turning an object a certain number of times) can begin to be introduced.

Furthermore, when teaching coding to preschool-aged children, it is essential to use an appropriate pedagogical approach, as at this age children have only developed very basic reasoning, lacking the ability to abstract or make complex associations. However, they can already perform two tasks simultaneously, making it an ideal time to introduce them to computer science [

30].

[

31] proposed, at a methodological level, the TangibleK program, which is a detailed curriculum for teachers who wish to teach coding in early childhood education. The theoretical foundations of this approach can be found in the framework of Positive Technological Development, aimed at developing personal and coding skills based on constructionism [

32], and Positive Youth Development [

33]. The program involves a minimum of 20 hours of in-person work divided into six sessions dedicated to engineering design processes, robotics, flows, loops and parameters, sensors and loops, and sensors and branches.

Each session follows a similar format: (1) initial preparation; (2) activities; (3) individual or collaborative work on a small project; (4) technology circle; and (5) assessment. The MECUE methodology [

34] is based on the TangibleK program adapted for an unplugged teaching approach without using robots, and on books such as

Hello Ruby [

35], in which a 5-year-old girl must solve various puzzles using coding skills—for example, dressing herself using the correct sequence of clothing. Other tasks may involve asking children to perform movements as if they were a robot executing the orders provided by the teacher in sequence, as if following a program.

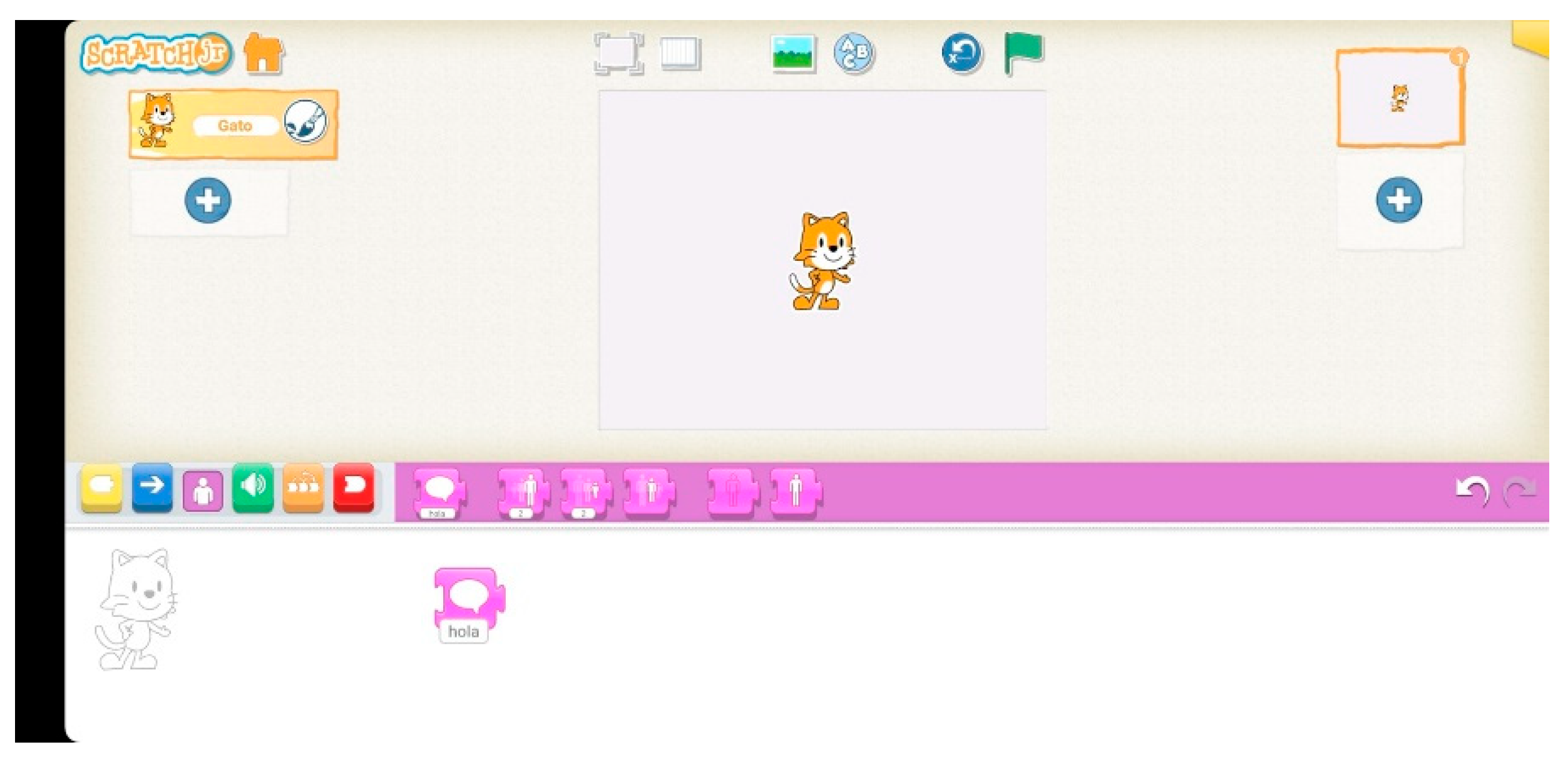

At the practical tools level, [

36] distinguished two main approaches: software environments and robots. In the case of software environments, it is emphasized that interaction for children aged 3 to 6 should be primarily tactile, interacting with a digital projector in class or with tablets. One of the most widely used software environments is the Scratch Jr. programming language [

37]. This language is simplified compared to Scratch but follows the same philosophy, facilitating the transition to using Scratch when the child turns 6. The instructions are also pieces of a puzzle that form the program to move an object, which can also be a cat. However, unlike Scratch, Scratch Jr. has fewer instruction blocks and is used on a tablet, as shown in

Figure 1.

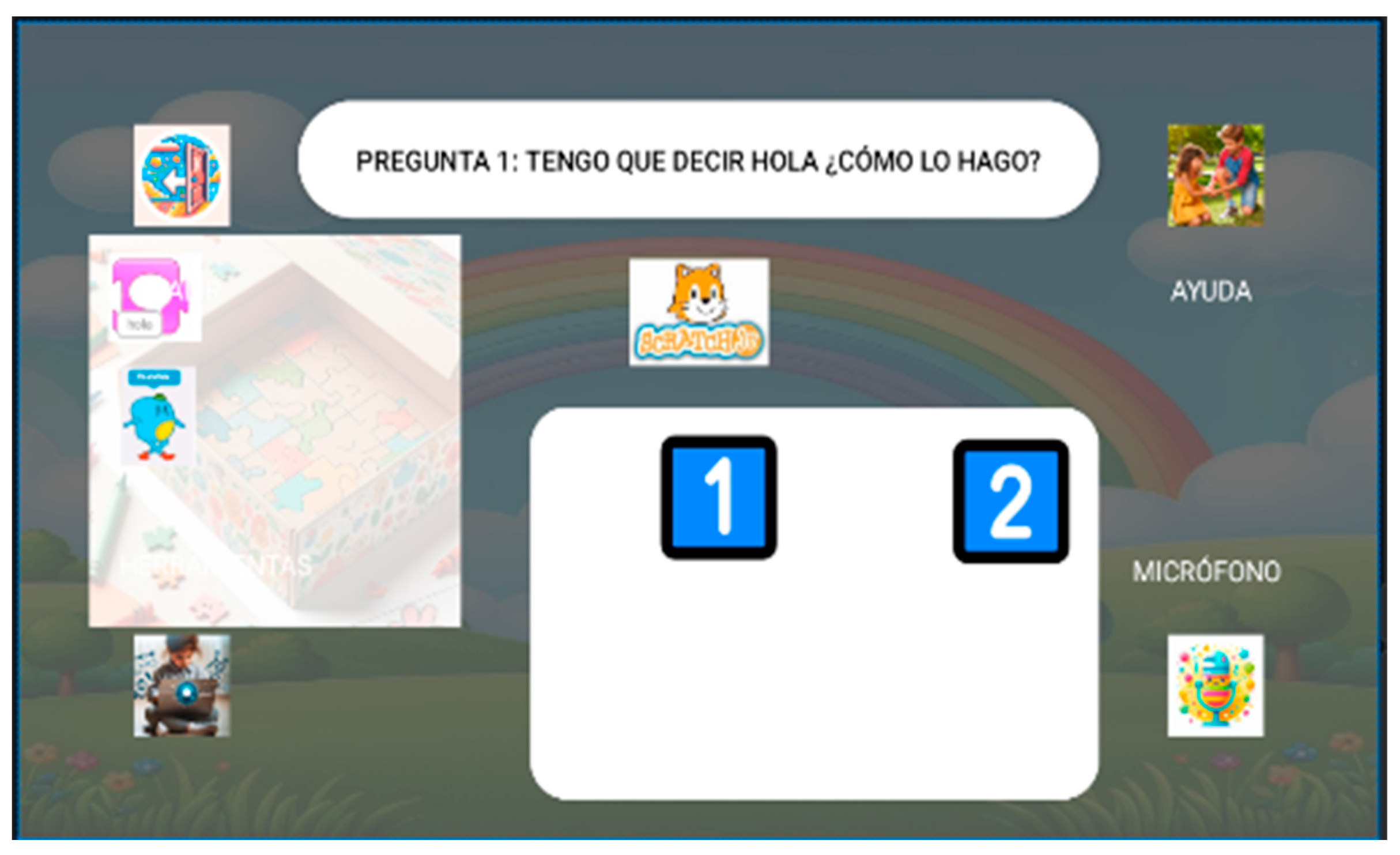

Figure 2 shows an example of a program to say “Hello” in Scratch Jr. on a tablet screen. It can be seen how the instruction with the text “Hello” is selected, and when executed, the cat says “Hello.”

In the case of robots, approaches without screens are distinguished, such as Cubetto [

8,

9], in which children also complete a puzzle—in this case, pieces to be placed on a wooden controller to move the robot on a grid mat forward, turn left, or turn right. It is also possible to combine this with a mixed approach, where one group of children uses Cubetto while other children perform the same actions themselves, following the robot’s sequence [

36].

Another group of robots is used with buttons, such as KIBO, Bee-Bot, Code & Go, and Code-a-pillar [

38], which differ in their design, how children can explore concepts and interact with the robot, and the range of activities that can be performed with the robot.

Figure 3 shows an example of the most representative button-based robots for developing programming skills in early childhood.

It can be observed that, in all cases, the design is friendly, rounded, and features bright colours to attract children’s attention. Additionally, three of the four robots are shaped like animals, which are generally very appealing at these ages. Regarding materials, plastic is typically used to reduce costs. They can also be distinguished based on whether they use insertable code blocks, as in KIBO, or plastic tiles, as in Code & Go. In any case, the benefits of young children being able to immediately see the effects of their interactions with the robot have been validated in multiple studies ([

31,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]).

However, there are few studies in the literature that integrate students with special educational needs, beyond the use of tangible versions of Scratch such as Scratch Jr., systematic reviews like the one published by [

44], or isolated experiences such as the one conducted by [

20], in which a Pedagogical Conversational Agent (PCA) was not used in any case [

22].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Context

During the 2024/2025 school year, a school in the Community of Madrid, Spain, was asked for permission to attend a validation session of a new interactive system being developed as a future training agent in Scratch Jr. This was done to assess whether, at that stage of development, students were able to interact with the system and their level of satisfaction.

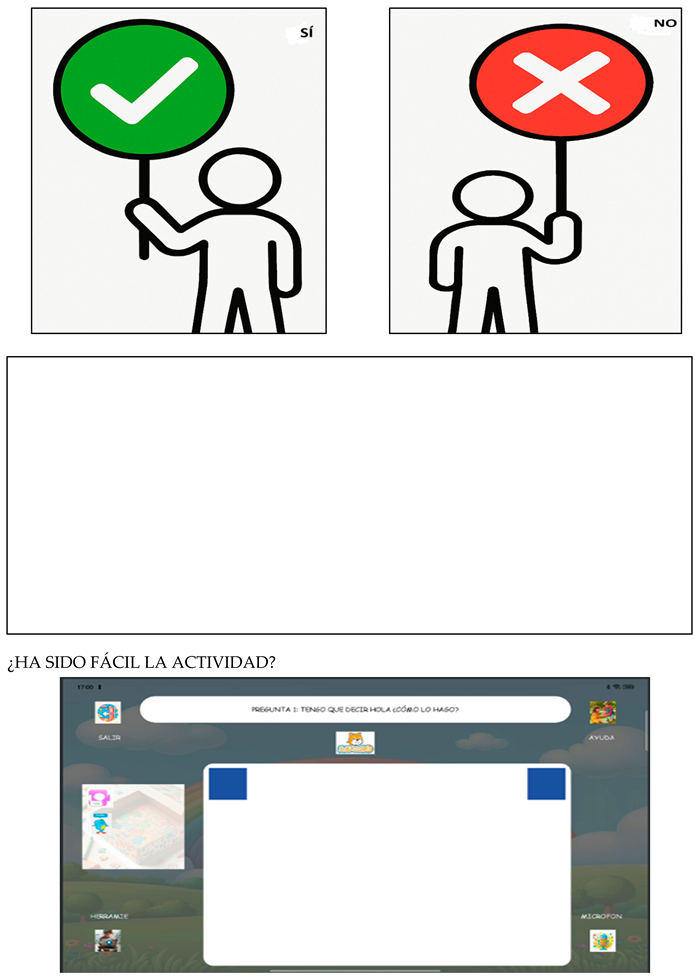

Figure 4 shows an example of a system screen, where it can be seen that the Scratch Jr. blocks are displayed on the left, the question appears at the top, and students must drag the blocks to the center to check whether they have completed the exercise correctly or if they need to try again.

As can be seen in

Figure 4, the initial question is “I have to say Hello! How can I do it?”. The idea is that the child helps Boby by dragging the Scratch Jr. blocks so that “Hello” is said in the correct position. Initially, no support is provided to see if neurotypical or neurodivergent students can complete the task independently. The option to receive help is available, including interacting with the agent by speaking (microphone) if a block cannot be dragged, and receiving all information in audio for students with visual impairments. For students with autism, the idea of sequence is emphasized using the numbers 1 and 2, and guided information about the task is provided in advance. For students with ADHD, they are allowed to take a pause and receive recommendations, such as going for a walk or using a Bobath ball, to better focus on the system’s instructions.

The novel approach of the tool should also be highlighted: it does not aim to teach the student and does not assume the role of a teacher. On the contrary, it takes on the role of a student who needs help, in order to increase motivation and satisfaction for learners who are not only learning for themselves but also helping the agent Boby, following the Learning by Teaching methodology used by agents such as Betty [

45].

3.2. Sample

Fifty children aged 6–7 years were recruited, of whom 17 (34%) are boys and the remaining 33 (66%) are girls. Two of the children are neurodivergent and have special educational needs. They are distributed across two classes with 25 students each, and in each class, 24 are neurotypical and 1 is neurodivergent with educational support needs.

None of the students have previously learned programming or are familiar with Scratch Jr. Forty-three of the 50 students (86%) are able to complete a simple questionnaire and have basic reading skills.

3.3. Research Questions

The main objective of this study is to validate whether both neurotypical and neurodivergent students are able to use the Boby system to train in the use of Scratch Jr., and to analyse which factors influence user satisfaction with the tool.

Research Question 1 (RQ1) is: which factors influence students’ satisfaction with Boby? The associated hypotheses are:

H1. Students who are accustomed to using tablets for learning will find using the Boby system more satisfying.H2. Students who enjoy block-based games will find using the Boby system more satisfying.

Research Question 2 (RQ2) is: to what extent does the student’s reading ability influence their ability to use Boby?

Research Question 3 (RQ3) is: which factors influence students’ ability to complete the activity shown in

Figure 4, that is, teaching Boby to say “Hello”.

3.4. Instrument

To address the research questions, a questionnaire with nine multiple-choice questions was designed and validated by a Special Education teacher, as described in our previous work [

25].

The questionnaire is included in

Appendix A (in Spanish).

3.5. Procedure

During a session in the computer classroom, students were arranged so that everyone had access to a tablet connected to the Internet to interact with the Boby system (see

Figure 4). The classroom tutor and a support teacher for students with special educational needs were present. Additionally, the first author of the article was allowed access to the classroom as an observing researcher.

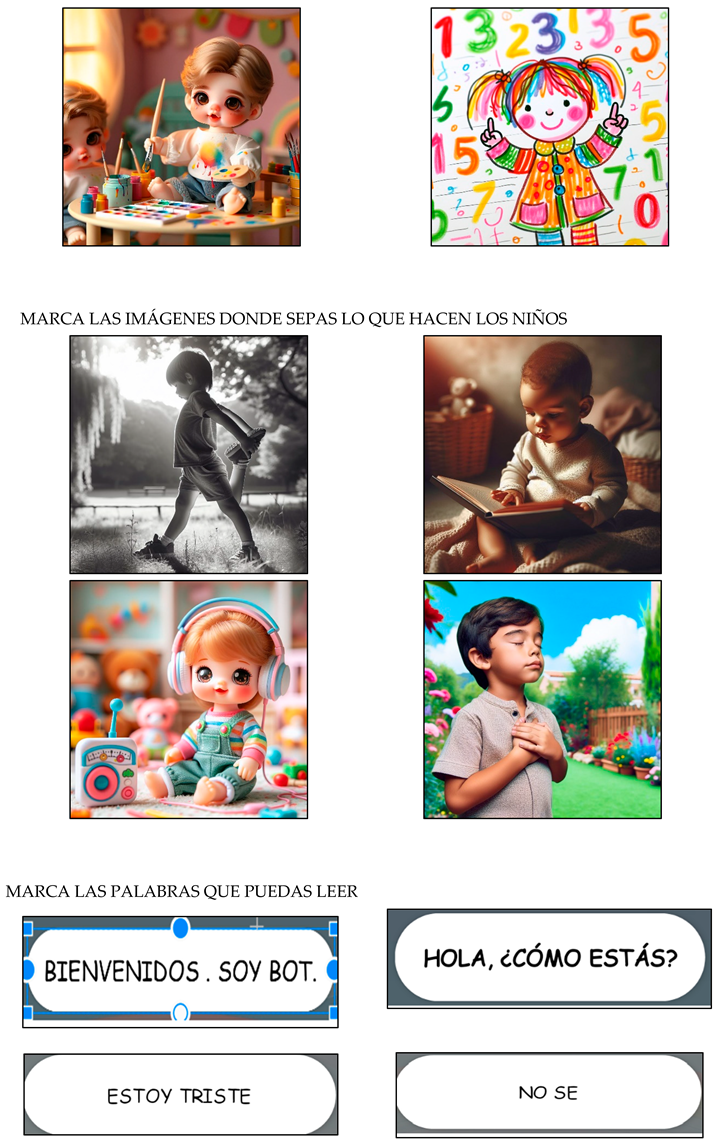

Initially, all students were asked to individually complete a paper questionnaire validated by the Special Education teacher, as described in our previous work [

25]. All neurotypical students were able to complete the questionnaire, as were the two students with special educational needs, with partial support of the teacher.

Subsequently, all students were allowed to interact with the Boby system freely for 30 minutes. It was observed that all neurotypical students were able to interact with the system without difficulty, and the two neurodivergent students with special educational needs were also able to interact with the system with the support of their teacher.

Finally, all students and their teachers were thanked for their participation in the experiment. The tablets were collected (an email with information about the completed exercise was sent to the researchers), and all data on the classroom tablets were deleted.

4. Results

This section analyses the two research questions posed. All inferential analyses were conducted after cleaning the data to exclude “No Response” (NR) answers in the variable measuring satisfaction with the app. The dependent variable of interest is Y26, which codes whether the child “liked the app” (1 = “Yes”, 0 = “No”). This allows satisfaction to be treated as a dichotomous variable.

Among the explanatory variables considered:

Q10 records the child’s usual use of the tablet (for example, “Games” or “Learning”).

Q14 records whether the child likes block-based games (“Yes” / “No”).

Q7 measures reading ability on an ordinal scale from 0 to 3, where higher values indicate greater reading proficiency.

It is important to consider three characteristics of the sample that influence interpretation:

The vast majority of children reported that they liked the app. That is, Y26 is highly skewed toward “Yes” (over 80%). This imbalance makes it more difficult to detect differences between groups, because there are few “No” cases.

Some levels of the predictor variables include very few children (for example, some do not like block-based games, or in Q7 = 0 there is only one case). This results in very low expected frequencies in certain cells of contingency tables, which reduces statistical power and can destabilize model estimation.

In the presence of cells with zero cases in a category (“separation”), logistic models may produce extreme odds ratios or very wide confidence intervals. Therefore, in addition to statistical significance, the stability or instability of the estimates is also reported.

With these precautions in mind, we first present RQ1 (factors associated with satisfaction) and then RQ2 (relationship with reading ability).

4.1. P1 — Factors Associated with Satisfaction with the App

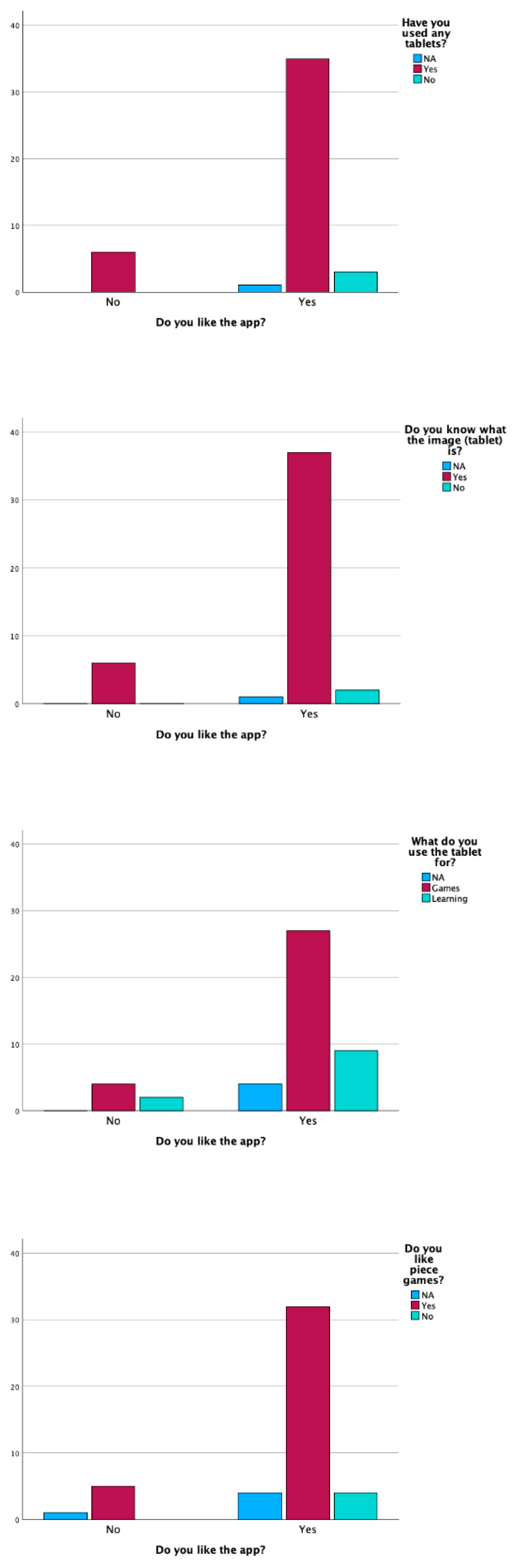

Descriptively, the majority of children reported that they liked the app.

Figure 5 shows the proportions of “Yes” and “No” responses in Y26, broken down by various relevant variables (for example, tablet use, preference for block-based games). Visually, it can be observed that in almost all categories, the bar corresponding to “Yes” is clearly dominant: practically all subgroups show high percentages of satisfaction with the app. At first glance, there is no large subgroup that rejects the app.

To analyse this question more rigorously, two specific hypotheses were evaluated:

4.1.1. H1 — “Children Who Are Accustomed to Using the Tablet for Learning Will Find the App More Satisfactory”

This hypothesis assesses whether the type of tablet use (Q10) is associated with liking the app (Y26). To test this, two steps were performed: (a) a bivariate contrast Y26 × Q10, and (b) a logistic regression model with Q10 as the predictor.

Firstly,

Table 2 summarizes the cross-tabulation between satisfaction (Y26 = “Yes” / “No”) and the usual type of tablet use (Q10). Pearson’s chi-square test was not significant (χ²(4) = 4.241, p = .374), and the effect size (Cramér’s V ≈ 0.227) falls within the small range. This suggests that, overall, no statistically clear differences were detected in the proportion of satisfied children across the different categories of tablet use.

However,

Table 2 also shows that 77.8% of the cells have expected frequencies lower than 5. This is methodologically very important: when there are cells with very few cases, the “classical” chi-square loses reliability, and results should be interpreted with caution or supplemented with exact or Monte Carlo tests. In other words, the data do not contradict the null hypothesis, but they also lack sufficient power to rule out small effects.

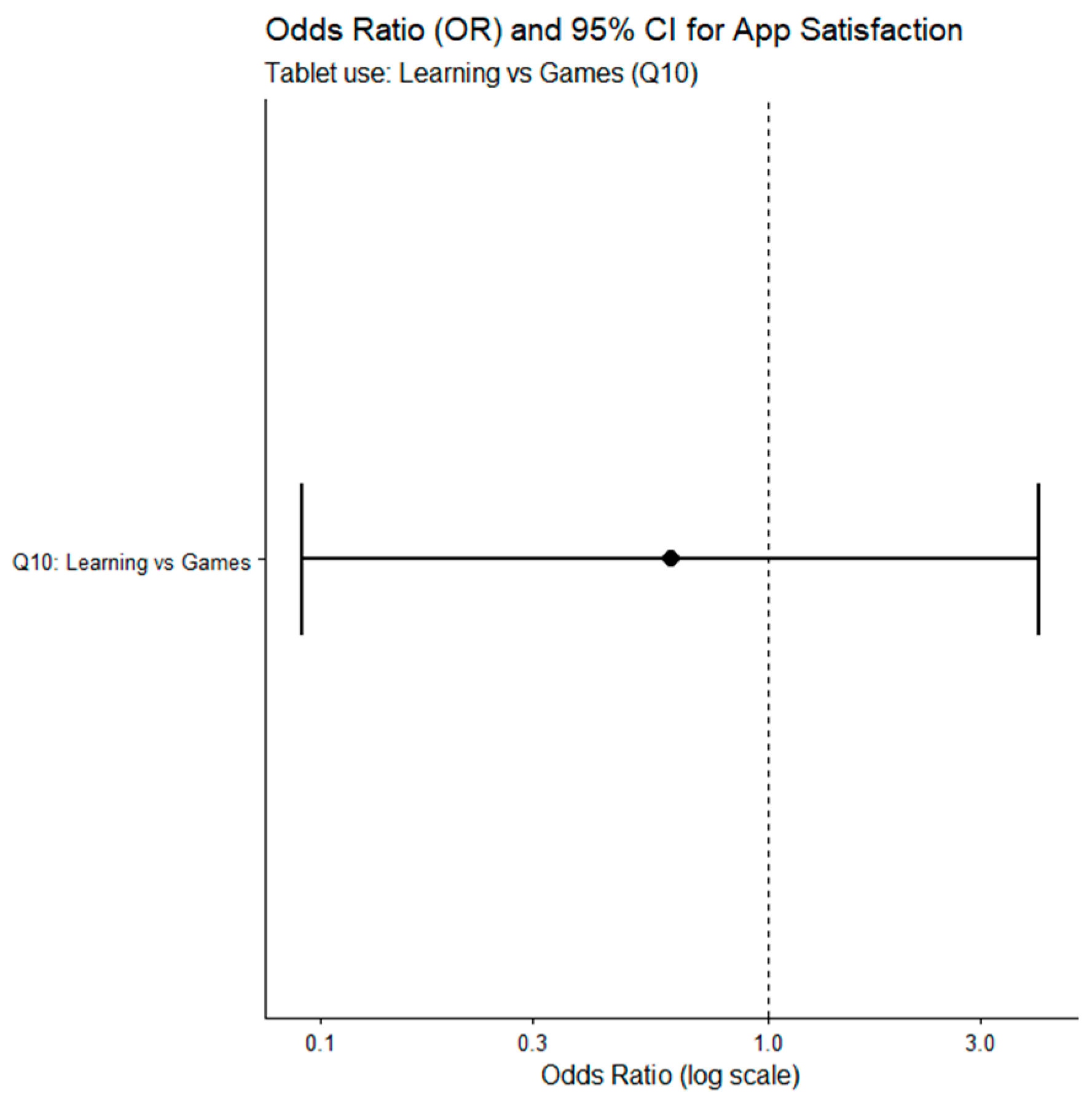

To further examine H1, a binary logistic regression was fitted with Y26 as the dependent variable (1 = “Yes”, 0 = “No”), and Q10 as the categorical predictor. In the model, the category “Games” (using the tablet mainly for playing) was taken as the reference, and the effect of “Learning” (using the tablet for learning) was estimated. The results are shown in

Table 3.

As shown in

Table 3, the odds ratio (OR) associated with the category “Learning” versus “Games” was 0.609. An OR lower than 1 would, in principle, suggest that “using the tablet for learning” is associated with a slightly lower likelihood of saying that the app is liked, compared to “using the tablet for playing.” However, this effect is not statistically significant (p = .608), and its 95% confidence interval is very wide ([0.091, 4.056]). This interval comfortably includes 1, which means that, given these data, the true effect could be slightly negative, null, or even positive; we cannot determine it precisely.

Moreover, the overall model barely improves over the model with only the constant (χ²(1) = 0.254, p = .615; Nagelkerke R² = .012). In other words, knowing whether the child uses the tablet for learning versus playing hardly helps to predict whether they will like the app.

Figure 6 shows the estimated odds ratio for “Learning vs Games,” along with its 95% confidence interval. The vertical dashed line marks OR = 1 (no effect). The point is slightly below 1, but the confidence band crosses 1 widely. Visually,

Figure 6 reinforces the same conclusion as

Table 3: there is no stable evidence that educational use (“Learning”) translates into higher (or lower) satisfaction with the app.

H1 is not confirmed. In this sample, reporting that the tablet is used “for learning” versus “for playing” is not significantly associated with a higher likelihood of liking the app.

4.1.2. “Children Who Like Block Games Will Find the App More Satisfying”

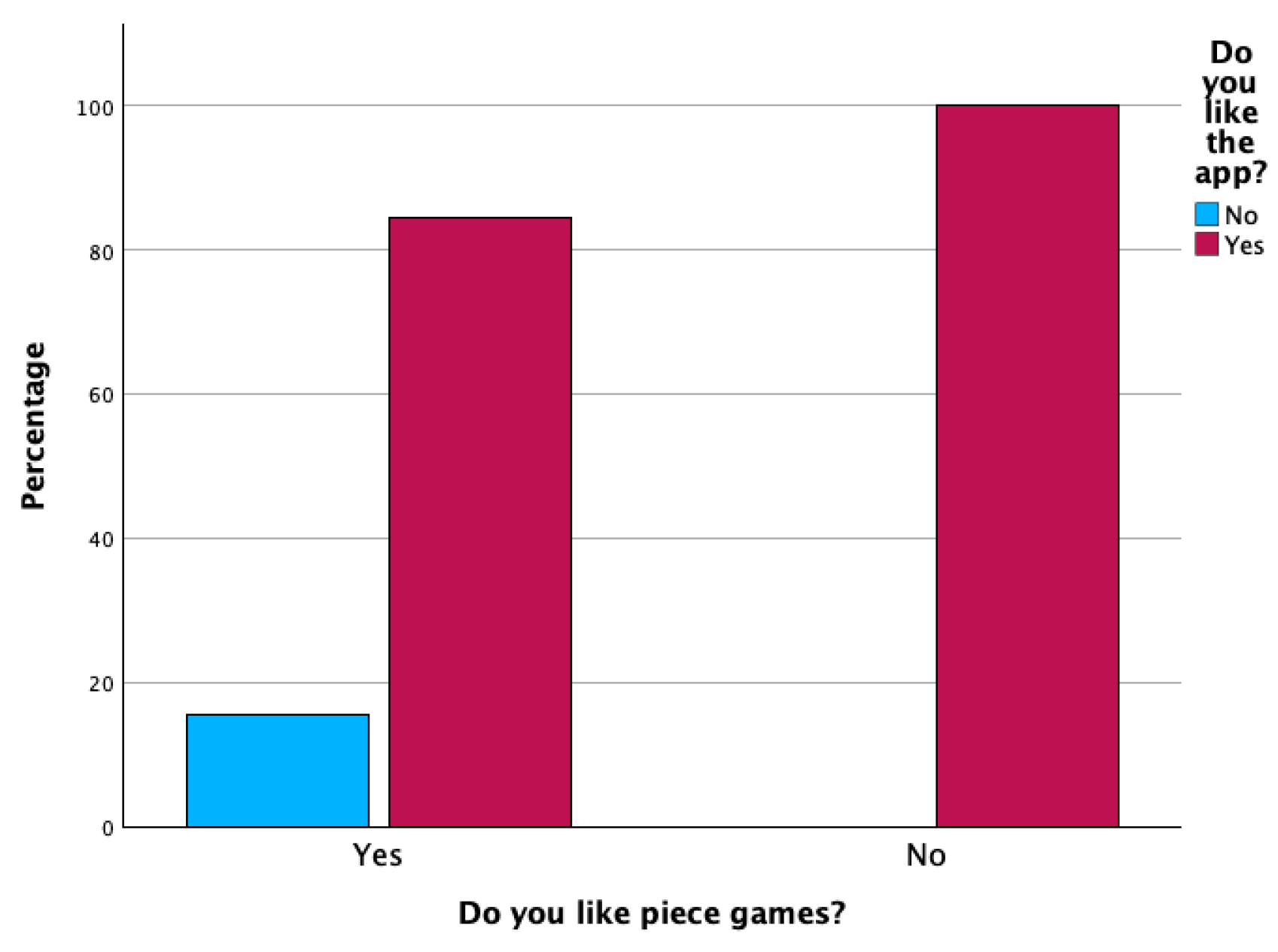

This hypothesis tests whether liking or disliking block/piece games (Q14) is related to liking the app (Y26).

Table 4 shows the frequencies and percentages of “Yes, I liked the app” depending on Q14 (“I like block games” / “I don’t like them”). The descriptive results are very high in both groups. Among children who said they like blocks, 84.4% reported that they liked the app (27 out of 32). Among those who said they do NOT like blocks, 100% reported that they liked the app (4 out of 4). In other words, satisfaction is high in both cases.

The test of independence was not significant: Pearson’s χ² = 0.726, p = .394, and Fisher’s exact test also showed no significant differences (p = .618). The effect size (Cramér’s V ≈ 0.142) is small. This suggests that, statistically, no clear difference is detected between the two groups.

However,

Table 4 itself reveals a critical limitation: the “Don’t like blocks” group is very small (n = 4), and within that group no child said “I didn’t like the app.” This results in a cell with a value of 0, known as quasi-separation. Such quasi-separation means that, if we attempt to fit a logistic regression with Q14 as the predictor, the model becomes numerically unstable (extreme odds ratios, infinite confidence intervals). In practical terms, it is impossible to reliably estimate how much liking blocks “protects” the outcome, because in a tiny subgroup all responses were positive.

Figure 7 shows the percentage of children who said “Yes, I liked the app” according to their preference for block games. Both bars are high (≥84%). The apparent difference (100% vs. 84.4%) should be interpreted with great caution because the 100% comes from only four children. Visually,

Figure 7 supports the idea that, in this sample, no subgroup is clearly dissatisfied with the app based on Q14.

H2 is also not confirmed. It was not found statistically strong evidence that liking block/piece games determines greater liking of the app.

4.2. P2 — To What Extent Does Reading Ability Influence Whether the App Is Liked?

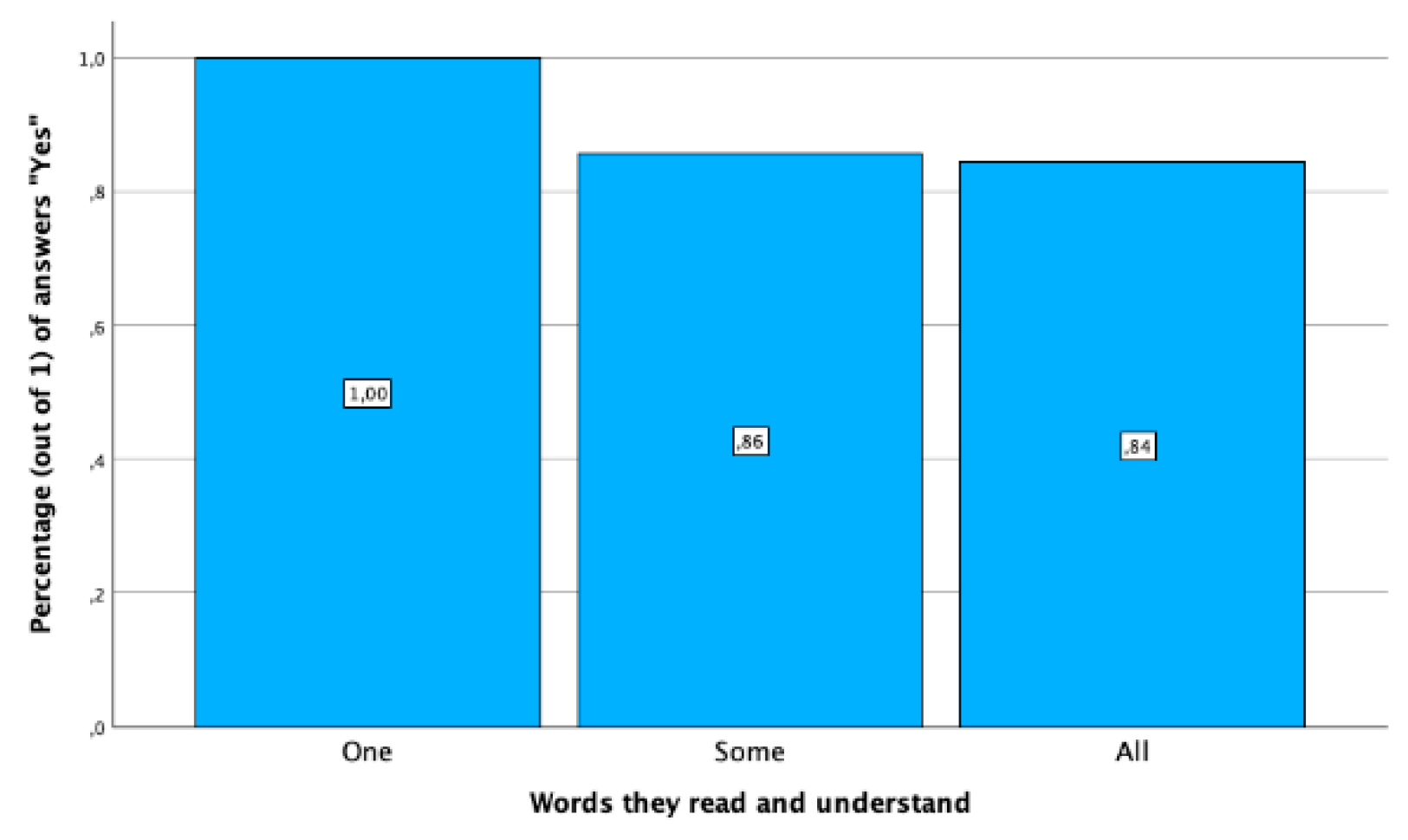

The second research question (P2) evaluates whether the child’s reading ability (Q7, ordinal scale from 0 to 3) is associated with the likelihood of liking the app (Y26). The theoretical interpretation would be: “As the child’s reading improves, is it more likely that they will rate the app positively?”

Table 5 presents, for each level of Q7, the subgroup size (n), the number of children who said they liked the app (Yes (n)), and the corresponding percentage (Yes (%)). For Q7 = 2 (“reads all words”), 84.4% of the children reported liking the app (27/32). For Q7 = 1 (“reads some words”), 85.7% gave the same response (6/7). For Q7 = 0 (“reads one word”), there was a single case, and it was positive (100%). There were no valid cases for Q7 = 3. The total valid sample in this analysis had 85.0% positive responses.

Figure 8 graphically shows the percentage of “Yes” (Y26 = 1) by Q7 level. The bars corresponding to Q7 = 1 and Q7 = 2 are very similar (around 85%), and the bar for Q7 = 0 appears at 100% only because there was a single child at that level. Visually,

Figure 8 suggests that there is no clear trend: satisfaction with the app remains high and fairly consistent across reading levels.

To formally test this impression, several analyses were conducted, and the results are presented in

Table 6.

The Pearson chi-square test on the Y26 × Q7 table was not significant (χ²=0.189, df=2, p=.910), indicating that, overall, no statistically reliable differences were detected in the distribution of “Yes”/ “No” responses across reading levels.

The linear-by-linear association test (a test of monotonic trend between Q7 and “I like the app”) also failed to reach significance (χ²=0.104, df=1, p=.747). In other words, there was no observable relationship of the form “the higher the reading level, the greater the likelihood of liking the app.”

The Spearman correlation between Q7 (ordinal) and Y26 (dichotomous) was very small and negative (ρ≈–0.039, p≈.81). This supports the idea that there is no appreciable monotonic relationship between reading ability and satisfaction with the app.

A binary logistic regression was fitted, with Y26 as the dependent variable and Q7 as the sole continuous covariate (Q7 treated as a 0–3 scale). The results of this model are reported in

Table 7.

In

Table 7, the odds ratio (OR) associated with a one-point increase in Q7 was approximately 0.71 (p=.745). An OR close to 1, together with such a high p-value, indicates that statistically, there is no evidence that higher reading ability alters the likelihood that a child reports liking the app. Furthermore, the model shows almost no improvement over the null model (omnibus χ² ≈ 0.116, p=.734; Nagelkerke R² ≈ .005), suggesting that Q7 accounts for virtually none of the variability in satisfaction.

No evidence was found that higher reading ability is associated with a greater likelihood of liking the app. Satisfaction levels were high across all reading proficiency levels considered.

4.3. Synthesis

Taken together, the results reveal a consistent pattern: satisfaction with the app was very high across nearly the entire sample, and no factors were identified that clearly explain differences in satisfaction among subgroups of children.

Specifically, no statistically significant associations were observed between liking the app and (a) the child’s usual use of the tablet (e.g., primarily for learning versus primarily for playing), (b) whether the child likes block or piece-based games, or (c) their reading level. In all cases, the probability that the child reported liking the app was high and very similar across categories or levels.

From a statistical perspective, independence tests did not detect significant differences between subgroups, effect sizes were small, and logistic regression models yielded odds ratios with wide confidence intervals that included the null value, along with very low explanatory power. Practically speaking, this implies that the data do not support the notion of a profile of children “who do not like the app”: both those who use the tablet primarily for playing and those who use it primarily for learning, both those who enjoy block-based games and those who do not, and both more advanced and less advanced readers tended to rate the experience positively.

These conclusions should be interpreted with caution due to several study limitations. First, some subgroups were very small (e.g., children who reported not liking block games or children at the lowest reading levels), which reduces statistical power and introduces instability in the estimates. Second, the dependent variable is highly unbalanced: the vast majority of children reported liking the app, with very few negative cases, making it more difficult to model differences accurately. Third, in some comparisons the expected frequencies were very low or even zero, limiting the robustness of certain tests.

Despite these limitations, the data gathered supports that the app was well received generally, and no large subgroup of children systematically rejected it.

5. Discussion

Regarding the first research question (P1) about the factors that influence students’ satisfaction with Boby, the following hypotheses were explored:

H1. Students who are used to learning with a tablet will find the use of the Boby system more satisfactory.

H2. Students who enjoy block-based games will find the use of the Boby system more satisfactory.

As shown in the results (

Section 4.1), neither of the two hypotheses was confirmed. This means that it is not necessary for students to be accustomed to using a tablet in order to use Boby, nor is it necessary for them to enjoy block-based games.

These results are relevant because they broaden the number of students who can interact with the agent to carry out their programming training using ScratchJr.

In particular, this includes autistic students who might not show interest in playing with blocks [

46] , but who may still be motivated to use Boby for training in ScratchJr, which is a block-based language.

It also takes into account students who usually do not have access to tablets due to economic constraints in their families or other types of limitations. Specifically, this refers to new regulations such as those in the [

47] in Spain, where the use of screens has been legally prohibited for children aged 0 to 3, limited to one shared hour per week for students in the second cycle of Early Childhood Education (ages 3–6) and the first cycle of Primary Education (ages 6–8), one and a half hours per week for students in the second cycle of Primary Education (ages 8–10), and two hours per week for those in the third cycle of Primary Education (ages 10–12).

There are exceptions to these laws for children with special educational needs, provided that a psychopedagogical report justifies that technology could support their learning [

47].

Regarding the second research question, which examined the extent to which a student’s reading ability influences their capacity to use Boby, the statistical analysis presented in

Section 4.2 also found no evidence that higher reading ability is associated with a greater likelihood of satisfaction when using Boby. This finding is significant because it indicates that students do not need to know how to read in order to use the app, which was designed to be visually accessible through descriptive icons and also includes auditory aids for students who are visually impaired.

These results are consistent with other studies that have gone a step further in exploring the inverse relationship—namely, that the use of an interactive application may even improve reading ability. In particular, studies have shown that young learners can engage successfully with interactive reading applications and that such experiences can positively influence their later non-digital reading skills [

48,

49]

Regarding the third research question, which explores the factors that influence students’ ability to complete the activity shown in

Figure 4—that is, teaching Boby to say “Hello”—the results show that both neurotypical and neurodivergent students are able to complete the activity regardless of their ability to use tablets, read, or visually identify the content of images.

In total, 38 out of 48 students were able to complete the activity (79.2%), including the two neurodivergent students, although both indicated that they had needed help. In any case, the assistance provided was minimal, and at no point did the teacher or the researcher complete the exercise for the student; rather, support was given only to allow the student to finish it independently.

When examining the cases in which students did not need help to complete the activity, no significant pattern was observed that could link reading ability or visual image recognition skills. Based on direct observation, it appears instead that this may be more closely related to the students’ own attitude—specifically, their preference for completing activities independently and their lower tendency to ask for or request help.

Finally, it should be noted that no student highlighted the agent’s “student” behaviour, possibly due to the short duration of the interaction (only a single session). This time limitation should be taken into account when interpreting the results.

6. Conclusion

The use of a pedagogical conversational agent in the role of a student to train both neurotypical and neurodivergent learners in ScratchJr. appears to be effective, regardless of the students’ ability to use tablets or play with blocks, when the students are between 6 and 7 years of age.

In particular, 79.2% of the students were able to complete the activity requested by the agent.

In the case of the two neurodivergent students, it is noteworthy that both were also able to complete the activity, although they required assistance from the support teacher.

Further exploration is planned to investigate the agent’s potential for teaching additional ScratchJr. instructions over longer periods and multiple sessions, and to subsequently assess to what extent this learning enables both neurotypical and neurodivergent students to program directly in the ScratchJr. environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J. Manzanares; methodology, D. Pérez-Marín.; software, M.J. Manzanares.; validation, D. Pérez-Marín; formal analysis, C. Pizarro.; investigation, M.J. Manzanares.; resources, M.J. Manzanares.; data curation, C. Pizarro; writing—original draft preparation, M.J. Manzanares; writing—review and editing, D. Pérez-Marín and C. Pizarro. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and FEDER/UE, grant number PID2022-137849OB-I00. The authors did not have to pay any APC.

Data Availability Statement

The data are public in BURJC.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all students and teachers involved in the experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- J. Abascal, I. Aedo, J. Cañas, M. Gea, A. Gil, J. Lorés, A. Martínez, M. Ortega, P. Valero y M. Vélez, «La interacción persona-ordenador,» 2001.

- J. Muñoz-Arteaga, C. Collazos, T. Granollers y H. (. Luna-García, Perspectivas en la Interacción humano-tecnología, Red HCI-Collab, 2023.

- CSTA, «Guía Educativa: Computer Science Teachers Association,» Computer Science K-8: Building a Strong Foundation., 2012.

- A. Manches y L. Plowman, «Computing education in children's early years: A call for debate.,» British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 48, nº 1, pp. 191-201, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Wing, «Computational Thinking.,» Communications of the ACM, vol. 49, nº 3, pp. 33-35, 2006.

- B. Oro-Martín y A. Martín-Giménez, «Cómo introducir la programación y la robótica en Educación Infantil, una propuesta de intervención con niños de cuatro años. Primera parte: Aprendiendo a programar.,» DIWO Journal., 2015.

- L. Caguana-Anzoátegui, M. Rodrigues-Pereira y M. Solís-Jarrín, «Cubetto for preschoolers: computer programming code to code.,» IEEE, 2017.

- Á. Alsina y Y. Acosta, «Conectando la educación matemática infantil y el pensamiento computacional: aprendizaje de patrones de repetición con el robot educativo programable Cubetto.,» Innovaciones Educativas., vol. 24, nº 37, pp. 1-20, 2022.

- J. Ramos Ruiz y P. Paredes Barragán, «Desarrollo del pensamiento Computacional mediante Cubetto en Educación Infantil.,» IE Comunicaciones: Revista Iberoamericana de Informática Educativa, nº 38, pp. 35-44, 2023.

- E. Pérez Vázquez, G. Lorenzo Lledó y A. Lledó Carreres, «Aplicación del robot Bee-bot en las aulas de educación infantil y educación: Una revisión sistemática desde el año 2016.,» 2021.

- G. I. Buendía Cueva, A. P. Tasayco Díaz y A. S. Menacho Rivera, «Gamificación y tecnología en la educación infantil: una revisión sistemática.,» Revista InveCom, vol. 5, nº 3, 2025.

- M. Ruiz Moltó y B. Arteaga Martínez, «El pensamiento geométrico-espacial y computacional en educación infantil: un estudio de caso con KUBO,» Contextos Educativos: Revista de Educación., nº 30, pp. 41-60, 2022.

- M. Resnick, J. Maloney, A. Monroy-Hernández, N. Rusk, E. Eastmond, K. Brennan, A. Millner, E. Rosenbaum, J. Silver, B. Silverman y Y. Kafay, «Scratch: Programming for all.,» Communications of the ACM., vol. 52, nº 11, pp. 60-67, 2009.

- M. Bers, «El desarrollo de Scratch J.R: el aprendizaje de programación en primera infancia como nueva alfabetización.,» Virtualidad, Educación y Ciencia, vol. 26, nº 14, pp. 43-62, 2023.

- J. Narváez Minda, E. J. Torres Navas, J. Analuisa Maguashca y E. R. Guerrón Varela, «Software Scratch J.R como recurso pedadógico para la consolidación de nociones espaciales en Educación Infantil.,» MIKARIMIN Revista Multidisciplinaria., vol. 7, nº 3, pp. 71-84, 2021.

- A. Meyer, D. H. Rose y D. Gordon, «Universal Design for Learning: Principles, Framework, and Practice (3rd ed.),» CAST, 2025.

- J. Smith y L. Brown, «Scratch Jr. Tactile: An inclusive approach to programming for young children.,» Jounal of Educationl Technlogy, vol. 10, nº 2, pp. 45-60, 2013.

- M. Elshahawy, K. Aboelnaga y N. Sharaf, «CodaRoutine: A serious game for introducing sequencial programming concepts to children with autism.,» IEEE Global Enginerering Education Conference (EDUCON), 2020.

- M. S. Zubair, D. Brown, T. Hughes-Roberts y M. Bates, «Designing accessible visual programming tools for children with autism spectrum condiction.,» Universal Access in the Information Society, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Taylor, «Computer programming with Pre-K through first-grade students with intellectual disabilities.,» The Journal of Special Education, vol. 52, nº 2, pp. 78-88, 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Utreras y E. Pontelli, «Introductory programming and young learners with visual disabilities: a review.,» Univ Access inf Soc 22, nº 22, pp. 169-184, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Johnson, «Animated Pedagogical Agents: Face-to-Face Interaction in Interactive Learning Environments,» Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education., vol. 11, pp. 47-78, 2000.

- J. Ocaña, E. Morales-Urrutia, D. Pérez-Marín y C.Pizarro, «Can a Learning Companion Be Used To Continue Teaching Programming to Children Even During The Covid-19 Pandemic?,» IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 157840-157861, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Morales-Urrutia, J. Ocaña, D. Pérez-Marín y C. Pizarro, «Cand Mindfulness Help Primary Education Students to Learn How to Program With an Emotional Learning Companion?,» IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 6642-6660, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Manzanares, D. Pérez-Marín y C. Pizarro-Romero, «Towards the use of pedagogic Conversational Agents to teach block-based programming to all using ScartchJr.,» Accpeted to be publieshed at SIIE 2025 press, 2025.

- F. García-Peñalvo, «Pensamiento computacional en los estudios preuniversitarios.,» El enfoque de TACCLE3, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Ozturk y L. Calingasan, «Robotics in early childhood education: A case study for the best practices.,» In H. Ozcinar, G. Wong, & H. Ozturk (Eds). Teaching computational thinking in primary education. Hersey, PA: IGI Global, pp. 182-200, 2018.

- Y. Ching, Y. Hsu y S. Baldwin, «Developing computational thinkin with educational technologies for young learners.,» TechTrends, vol. 62, nº 6, pp. 563-573, 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Morgado, M. Cruz y K. Kahn, «Preschool cookbook of computer programming topics.,» Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 26, nº 3, pp. 309-326, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Etecé, «Niño de 3 años,» Biblioteca Humanidades, 2023.

- M. Bers, «Beyond computer literacy: Supporting youth`s positive development through technology.,» New Directions for Youth Development, nº 128, pp. 13-23, 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Papert, «Mindstorms: Children: computers, and powerful ideas,» New York, NY: Basic Books, 1980.

- R. Lerner, J. Almerigi, C. Theokas y J. Lerner, «Positive youth development: A view of the issues.,» Journal of Early Adolescence, vol. 25, nº 1, pp. 10-16, 2005. [CrossRef]

- D. Pérez-Marín, «Teaching Programming in Early Childhood Education with stories.,» Actas de la international Coference of Education Research and Innovation (ICERI), pp. 9206-9212, 2019.

- L. Liukas, Hello Ruby: adventures in coding., Macmillan, 2015.

- A. Otterborn, K. Schonborn y M. Hultén, «Investigating Preschool Educators` implementation of Computer Programming in Their Teaching Practice.,» Early Childhood Education Journal, vol. 48, pp. 253-262, 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Flannery, B. Silverman, E. Kazakoff, M. Bers, P. Bontá y M. Resnick, «Designing ScratchJr: Support for early childhood learning through computer programming.,» In Proceedings of the 12th international conference on interaction design and children, pp. 1-10., 2013.

- T. Yu y N. Roque, «Designing pedagogic conversational agents: A framework and review.,» International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, vol. 32, nº 1, pp. 1-35, 2022.

- I. Beraza, A. Pina y B. Demo, «Soft & hard ideas to improve interaction with robots for kids & teachers.,» Proceedings of SIMPAR 2010 international conference on simulation, modeling and programming for autonomous robots., pp. 549-557, 2010.

- K. Highfield, «Robotic toys as a catalyst for mathematical problem solving,» Australian Primary Mathematics Classroom., vol. 15, nº 2, pp. 22-27, 2010.

- K. Stoeckelmayr, M. Tesar y A. Hofmann, «Pre-primary children programming robots: A first attempt.,» Proceedings of 2nd international conference on robotics in education., pp. 185-192, 2011.

- E. Kazakoff y M. Bers, «Programming in a robotics context in the pre-primary classroom: The impact on sequencing skills.,» Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, vol. 21, nº 4, pp. 371-391, 2012.

- M. Bers, L. Flannery, E. Kazakoff y A. Sullivan, «Computational Thinking and tinkering: Exploration of an early childhood robotics curriculumn.,» Computers & Education, nº 72, pp. 145-147, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, H. Skouteris, A. Tamblyn, E. Berger y C. Blewitt, «Cross-disciplinary collaboration supporting children with special educational needs in early childhood education: A scoping review.,» Early Childhood Education Journal., 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Leelawong y G. Biswas, «Designing learning by teaching agents: The Betty's Brian system.,» International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education., vol. 18, nº 3, pp. 181-208, 2008.

- R. Elbeltagi, M. Al-Beltagi, N. K. Saeed y R. Alhawamdeh, «Play therapy in children with autism: its role, implications, and limitations.,» World journal of clinical pediatrics, vol. 12, nº 1, p. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. d. Madrid, 2025. [En línea]. Available: https://www.comunidad.madrid/noticias/2025/03/19/comunidad-madrid-primera-espana-elimina-uso-individual-dispositivos-digitales-colegios#:~:text=Los%20m%C3%A1s%20peque%C3%B1os%20del%20primer,de%20madurez%20de%20sus%20alumnos.&text=La%20norma%20tambi%C3%A9n.

- X. C. Wang, T. Christ, M. M. Chiu y E. Strekalova-Hughes, «Exploring the relationship between kindergarteners' buddy reading and individual comprehension of interactive app books.,» AREA Open, vol. 5, nº 3, pp. 1-17, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Raja, A. B. Setiyadi y F. Riyantika, «The Correlation between perceptions on the use of online digital interactive media and reading comprehension ability.,» International Journal of English Language and Literature Studies, vol. 10, nº 4, pp. 292-319, 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).