1. Introduction

The assessment of the learning process is an essential element present in various educational systems. This assessment allows measuring and contrasting the progress made by students, being essential to consolidate the content in the pedagogical field (Hernández-Nodarse, 2017). In the field of sciences, this component acquires significant relevance, as it seeks to promote understanding and scientific reasoning in classrooms (Sáez Brezmes and Carretero, 1996).

Evaluation in the Science environment fosters the development of scientific skills and the acquisition of knowledge, facilitating students' understanding of the world around them (Izquierdo Aymerich, 2014). From this need arises the purpose of designing an evaluation method that covers topics such as "The organs of the senses and the locomotor system" and "The nervous and endocrine systems," based on formative assessment that provides constructive feedback, promoting learning improvement and the development of scientific competencies (Torres, 2013).

The integration of technologies in education has become essential, given its significant impact on the development of current society. The use of these technologies brings about various changes in the educational context, forcing teachers and researchers to rethink their priorities to meet the educational demands of their students (Adell Segura, 1997; Coscollola and Agustó, 2010). To address these needs, various useful tools and applications have emerged in teaching.

Scratch is an example of a tool with great educational potential. This programming environment, designed by the "Lifelong Kindergarten" research group at the MIT Media Lab, was created for multidisciplinary projects through electronics (Barceló Garcia, 2014). In addition to its utility in project development, Scratch is presented as an effective tool for creating more engaging assessments for students. Jiménez-Pérez et al. (2018) developed a research project that supports the use of Scratch as an assessment method in the classroom, using their classes as samples and evaluating, through various activities, the knowledge acquired by their students.

The main objective of this study is to evaluate the content learned by students through the use of the Scratch tool. By analyzing the results obtained, the study aims to observe the potential that this tool can contribute to the processes of evaluating student learning and development, considering the level of knowledge that both teachers and students must possess to maximize its benefits (Bayón, 2015). Additionally, the study examines how the integration of innovative technologies can influence student motivation and engagement.

In this context, the results are compared with another group that conducts a gamification session in the classroom to cover the same content but through a different methodology. This comparison aims not only to assess the effectiveness of each approach but also to identify best pedagogical practices to foster active and meaningful learning. Thus, the study seeks to understand the multiple advantages and influences of gamification in learning processes, supported by various studies and experiences in the educational field (González, 2019).

In the present study, the following questions will be addressed with the aim of clarifying potential uncertainties regarding the use of the Scratch application in educational settings:

-

RQ1: What is the impact of using the Scratch tool on student learning and development?

This question will examine how the use of Scratch has influenced the knowledge and skills acquired by students, as well as their cognitive and academic development.

-

RQ2: What level of knowledge and training do both teachers and students require to maximize the benefits of Scratch?

This will analyze the degree of preparation and training necessary for teachers and students to fully leverage the capabilities of the Scratch tool in the educational process.

-

RQ3: How does the integration of innovative technologies influence student motivation and engagement?

This will explore the effect of incorporating technologies such as Scratch on student motivation and their level of engagement with their learning.

-

RQ4: What differences in effectiveness were observed between the use of Scratch and gamification to teach the same content?

This will compare the results of students who used Scratch with those who participated in gamification activities to determine which method was more effective in teaching the intended content.

-

RQ5: What best pedagogical practices have been identified to promote active and meaningful learning?

This will identify and discuss the most effective pedagogical strategies that emerged from the study, focusing on promoting active and meaningful learning among students.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Technologies in the Educational Field

Technologies play a crucial role in the educational field, providing new tools and methods that significantly enhance teaching and learning processes. The integration of these technologies has demonstrated improvements in students' academic performance, although further research is needed to consolidate these findings (Valverde-Berrocoso, Acevedo-Borrega, & Cerezo-Pizarro, 2022; Scherer, Siddiq, & Tondeur, 2019).

One of the advantages that technology offers in education is the diversity of options that can be utilized according to the individual needs of each student. These options include personalized learning platforms and online courses, which facilitate continuous knowledge acquisition. The effectiveness of these tools varies depending on their proper implementation, as incorrect application can be counterproductive (Escueta, Nickow, Oreopoulos, & Quan, 2020; Walkington, 2013).

Technological innovation not only enhances the quality of teaching but also promotes self-learning and fosters critical thinking among students (An & Oliver, 2020). Digital tools like simulations and educational games have been found to improve problem-solving skills and encourage active learning (Clark, Tanner-Smith, & Killingsworth, 2016). However, it is important to consider that these innovations entail associated costs, both in terms of acquiring and maintaining equipment and in the training required for instructors to use them effectively (Loui, 2005; Robinson et al., 2020).

Furthermore, integrating technology in education requires robust cybersecurity measures to protect sensitive student data and ensure a safe learning environment. As educational institutions increasingly rely on digital tools, they must also address privacy concerns and implement stringent data protection policies (Livingstone, Stoilova, & Nandagiri, 2019).

Overall, while the potential of educational technology is vast, its successful integration necessitates thoughtful planning, ongoing support, and a commitment to equity to truly enhance the learning experience for all students.

2.2. Importance of Assessment in Science

Assessment in science is a multifaceted process integral to the educational landscape, serving as a cornerstone for measuring students' knowledge and skills while also guiding pedagogical strategies and curriculum development. This holistic approach to assessment is underscored by a body of research that emphasizes its crucial role in fostering effective teaching and learning practices.

Moeed (2015) highlights the diagnostic function of assessment, emphasizing its capacity to monitor students' progress and performance over time. By providing educators with valuable insights into students' strengths and areas requiring further attention, assessment acts as a catalyst for instructional refinement and targeted interventions.

Moreover, assessment in science extends beyond the confines of individual classrooms, influencing educational policies and curriculum standards. Stern and Ahlgren (2002) underscore the importance of aligning science curriculum with national and state standards to ensure coherence and relevance in educational content.

A pivotal aspect of effective assessment lies in the provision of constructive feedback for both teachers and students. Stăncescu (2017) emphasizes the reciprocal nature of feedback, positing that meaningful engagement with feedback fosters continuous improvement in teaching and learning practices.

In the realm of science education, the use of diverse assessment tools is essential for capturing the complexity of students' knowledge and skills. Lovelace and Brickman (2013) advocate for the incorporation of theoretically grounded analyses supported by empirical evidence to enhance the validity and reliability of assessments, particularly regarding students' attitudes towards scientific inquiry.

Furthermore, the validity and reliability of assessment instruments are paramount in accurately gauging students' scientific reasoning and knowledge. Liu, Lee, Hofstetter, and Linn (2008) stress the importance of employing rigorous methodologies to ensure the trustworthiness of assessment results.

In conclusion, assessment in science serves as a linchpin for educational improvement, driving pedagogical innovation, and curriculum alignment while also fostering a culture of continuous learning and development. By integrating evidence-based assessment practices into science education, educators can effectively nurture the next generation of scientifically literate individuals equipped to navigate the complexities of the modern world.

2.3. Scratch as an Educational Tool

In addition to its impact on academic performance and motivation, Scratch has been recognized for its versatility in enhancing learning outcomes across diverse subjects and educational levels. For instance, a study by Malinverni, Giacomin, and Storti (2018) investigated the use of Scratch in teaching mathematics. Their findings revealed that integrating Scratch into math lessons not only facilitated a deeper understanding of mathematical concepts but also promoted collaboration and problem-solving skills among students.

Furthermore, Scratch's applicability extends beyond primary education, reaching secondary and even tertiary levels. Research by Caballé, Clarisó, and Rodríguez-Ardura (2017) explored the use of Scratch in higher education, particularly in computer science courses. They found that Scratch served as an effective introductory tool for programming concepts, allowing students to grasp fundamental principles in a hands-on and engaging manner.

Moreover, the collaborative nature of Scratch projects fosters teamwork and communication skills, essential attributes for success in the modern workforce (Sáez-López, Román-González, & Vázquez-Cano, 2016). Students working on Scratch projects often collaborate, share ideas, and provide feedback to one another, simulating real-world professional environments.

In summary, Scratch's effectiveness as an educational tool transcends disciplinary boundaries and educational levels. Its ability to foster computational thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, and motivation makes it an asset in modern educational settings (Malinverni et al., 2018; Caballé et al., 2017; Sáez-López et al., 2016).

3. Research Design

Conventional evaluation systems are becoming obsolete with the advancement and development of technologies. It is crucial that educators familiarize themselves with these new tools to address and meet the educational needs of their students. Therefore, they must maximize the potential benefits of these applications. However, educators and researchers need to verify their effectiveness and determine whether it is worthwhile to introduce them into the classroom.

From this notion arises the necessity of conducting experimental projects in the classroom, where real data can be obtained for comparison with different samples. This process determines the functionality and potency of their usage. The objective is not only to facilitate student learning but also to empower educators with the capacity and time to develop suitable and precise evaluation systems.

The present study employs the experimental research method from a quantitative perspective, complemented by the collection and utilization of qualitative results to bolster the project's development. In this regard, the choice of the adopted methodological model is supported by the data obtained, the researcher's observations, feedback from participating students, and the employed methodological procedures (Hernández, R., Fernández, C., & Baptista, P., 2010). The dependent variable under evaluation is the progress in student learning through the utilization of the Scratch platform. The experimental design is supported by the execution of pretests and posttests in two distinct groups: one serving as the control group and the other as the experimental group. Each group is assigned to work, respectively, with Scratch and a gamification application developed by the researcher. This approach enables the comparison and analysis of two different evaluation modalities, each with its own peculiarities and inherent challenges.

The contextual framework of the research is limited to third-grade students of Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO), specifically in the subject of "Biology and Geology." A non-probabilistic, casual sampling method is employed, selecting two classes as a representative sample. Class "A" comprises 22 students, while class "B" consists of 27 members. It is noteworthy that the study is conducted in a school located in the Usera neighborhood, with the sample selection confined to the third-grade educational level. Participating students have recently worked with the Scratch platform, possessing basic knowledge of its operation.

3.1. Pedagogical Strategy

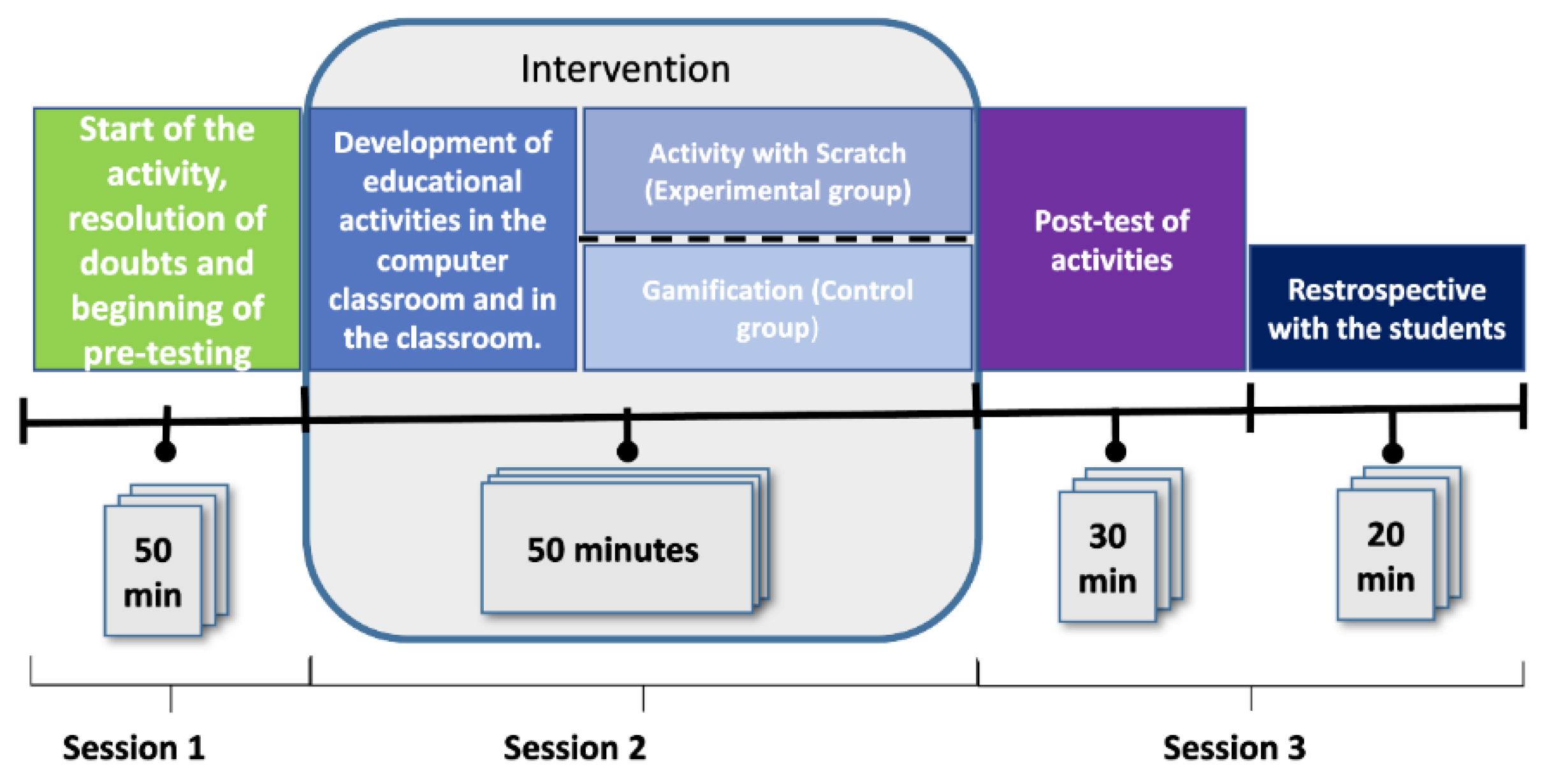

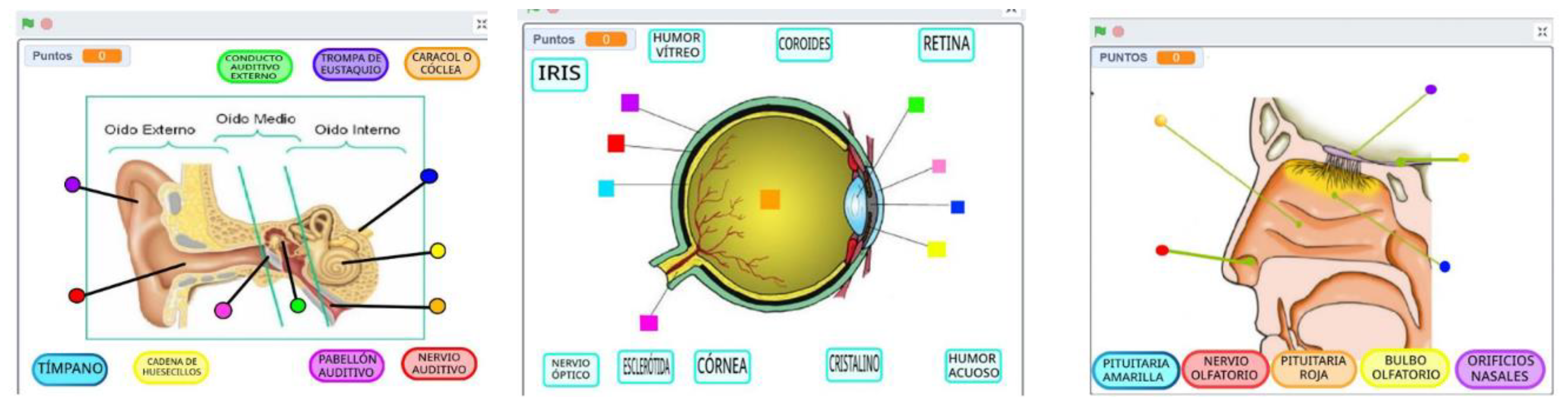

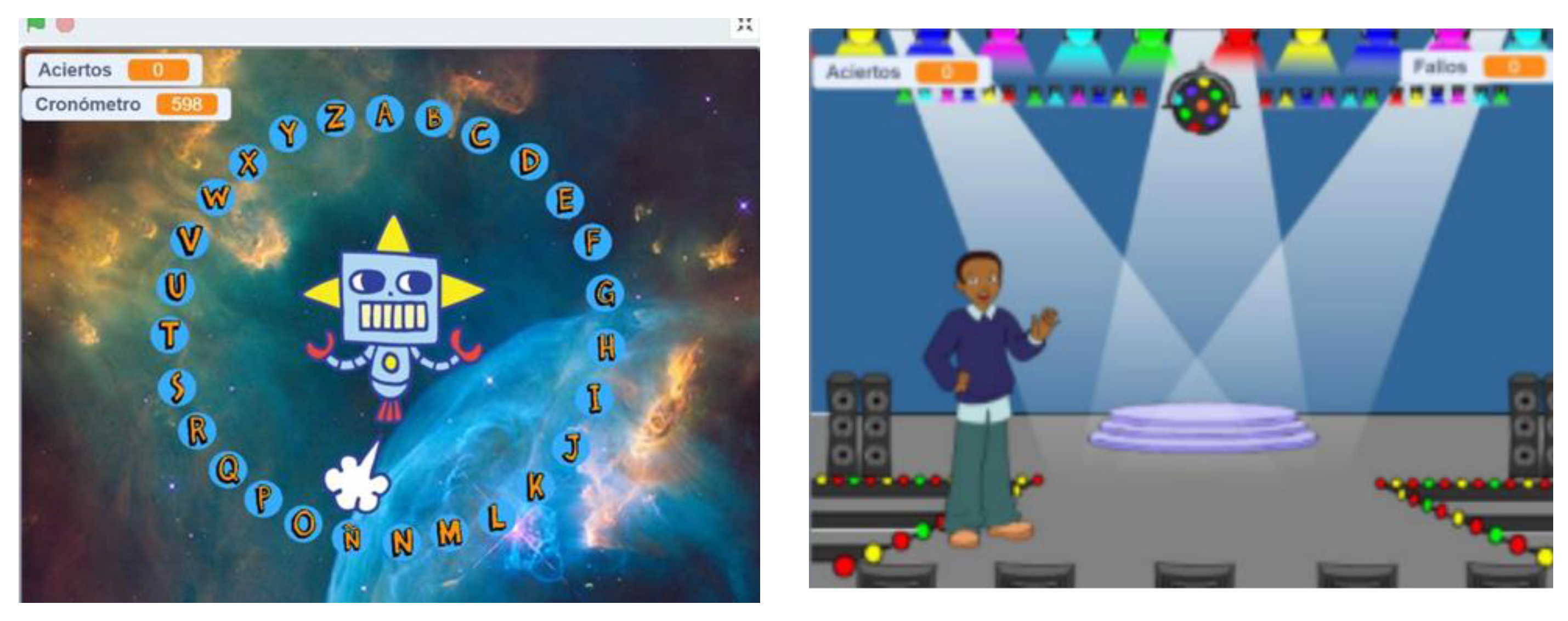

Educational intervention is defined as the process in which students play an active role in the educational domain (see

Figure 1). This stage encompasses both didactic activities and data collection, with the ultimate purpose of analyzing and comparing the information gathered from the samples.

Over the course of three sessions, students will utilize Scratch and gamification as learning tools. The first session is dedicated to explaining the project's dynamics and objectives to the students. Following the researcher's presentation, a Q&A session ensues to address any queries raised. It is noteworthy that prior to this session, both participants and their parents have received two informational documents allowing them to decide on their participation in the activity. Subsequently, participants will complete a pretest as the initial step of the activity, using an electronic form. Thus, a Chromebook will be provided per participant for individual responses. In sessions two and three, groups will engage in their respective activities, with the researcher present to address any emerging queries or difficulties. At the conclusion of the third session, participants will fill out a posttest, marking the conclusion of the study.

Determining the number of sessions for the research entails selecting activities most relevant to the study's context. In this context, the activities to be carried out throughout the project are specified:

-

Gamification activity:

- ○

This activity is based on a board game like "Oca", with varied rules and challenges. Participants face different game formats depending on the card's color, which may include questions, drawings, mime, and challenges like Trivial Pursuit and Taboo.

Figure 4.

Image of the game of the Oca.

Figure 4.

Image of the game of the Oca.

From a methodological perspective, the sessions are designed for students to present the concepts learned through practical activities, receiving continuous feedback on their performance. The activities themselves provide indicators of answer correctness, offering brief explanations in case of errors or doubts. Should a lack of understanding persist, the teacher and researcher intervene. Students actively participate in their learning process, utilizing available resources to solve posed challenges. Furthermore, as the activities take place at the end of the didactic unit, participants always have ample resources for support, as well as the opportunity to collaborate with each other to reinforce their knowledge.

3.2. Research Participants

The sample selection comprised a group of 49 third-grade students of Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO). Access to this group was fortuitous, stemming from the researcher's planning and facilitated accessibility. The choice of the subject "Biology and Geology" was based on the researcher's particular motivation and preference for this field. This subject encompasses concepts previously encountered and interacted with by the participants in the "Technology" subject, rendering this grade the most suitable context for the experimentation conducted in the classroom. Moreover, this selection enables the pursuit of the objectives outlined by the subject tutors. Consequently, the study does not disrupt the regular learning process but rather serves as a complement to motivate and solidify established knowledge.

A non-probabilistic casual sampling approach was employed, involving 49 students from a secondary education institution in the Community of Madrid. These participants were divided into two sample groups according to the school's established organization, namely, class "A" and class "B". Both classes follow the same study methodology, ensuring that the achieved results are comparable. Class "A" comprises 22 students, while class "B" comprises 27.

The control group was assigned to class "A", which conducted the gamification-related activity, while class "B" constituted the experimental group, focusing on working with activities designed using Scratch software. The participants' age was not deemed a relevant factor in the study, and participation in the project was voluntary during all scheduled sessions. Importantly, the participants' identities remained anonymous throughout, ensuring impartiality in their opinions and responses.

3.3. Ethics Comitee

Research Ethics Committee of the Rey Juan Carlos University has favorably evaluated this research project with internal registration number 2802202310023.

3.4. Instrument for Measuring

The most suitable data collection technique determined is the implementation of both a pretest and a post-test. The pretest will be conducted at the outset of the project in both groups to assess the initial level of the students. At the conclusion of the session, both groups will respond to the post-test with the aim of observing the potential changes generated by the various activities.

The development of the questionnaire for both working groups involves formulating an instrument designed to obtain project results. This questionnaire has been crafted by the researcher, who has derived the questions from the content delivered by the classroom tutors, primarily drawing from the instructional material used during the academic year and supplementary information sources. At no point are questions included that have not been addressed during the classes or that fall outside the participants' scope of knowledge.

As previously mentioned, an assessment is conducted both before commencing the proposed activities (pretest) and upon their completion (post-test). It is noteworthy that both groups will respond to the same questions in the pretest and post-test, with only the presentation order of the questions varying. The questionnaire comprises nine questions with four possible answers related to the study topic, with it being indicated that only one of them is correct. At this juncture, potential quantitative results are obtained.

To refine and enrich the project, the questionnaires include three unprompted questions, through which participants express their opinion regarding the tools utilized in each group. Thus, qualitative results are obtained that reflect the motivation and interest elicited in the students by said pedagogical tool.

The developed questionnaire exhibits the following characteristics:

Objective: To assess the level of knowledge acquired by the participants.

Target population: 3rd-grade students of Secondary Education.

Type of instrument: Objective multiple-choice questionnaire with four possible response options and only one correct solution.

Maximum completion time: 30 minutes.

-

Guidance questions: Once the nine questions are answered, participants encounter three questions where they can provide their opinion.

The links used for the students are as follows:

4. Results

Throughout the course of the research, both quantitative and qualitative data were collected. Quantitative data were gathered through the administration of questionnaires using electronic devices such as personal computers and tablets. Qualitative data, on the other hand, were obtained through methods of direct observation and the formulation of anonymous open-ended questions, allowing participants to express their opinions.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4.1. Quantitative Aspects

Regarding the quantitative data, a statistical analysis of the questionnaire results was conducted. As for the qualitative data, findings were presented descriptively.

In terms of quantitative data, it is reported that the results obtained during the study belong to a non-probabilistic sample, comprising two distinct groups. The control group consisted of 22 individuals, while the experimental group comprised 27 participants.

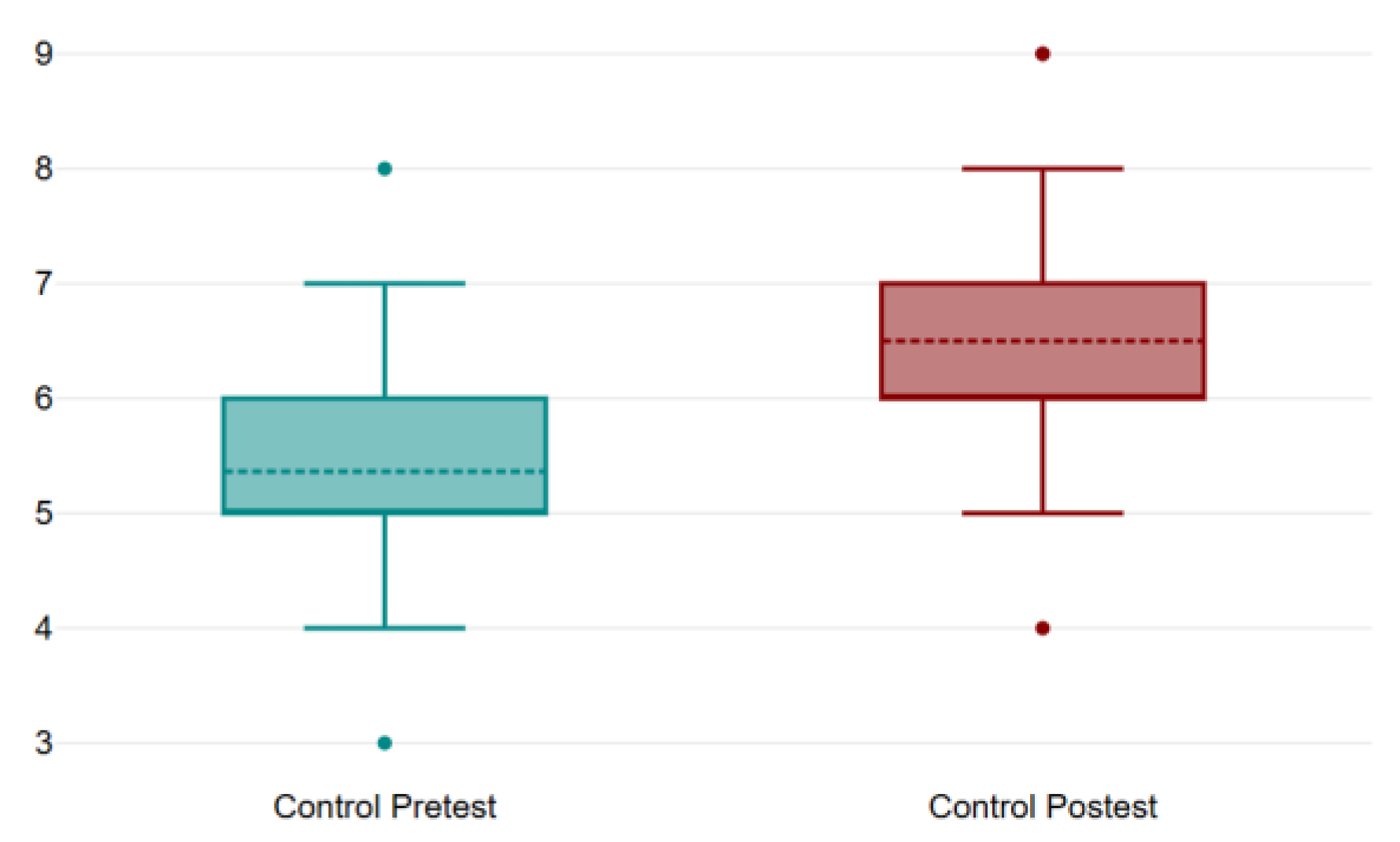

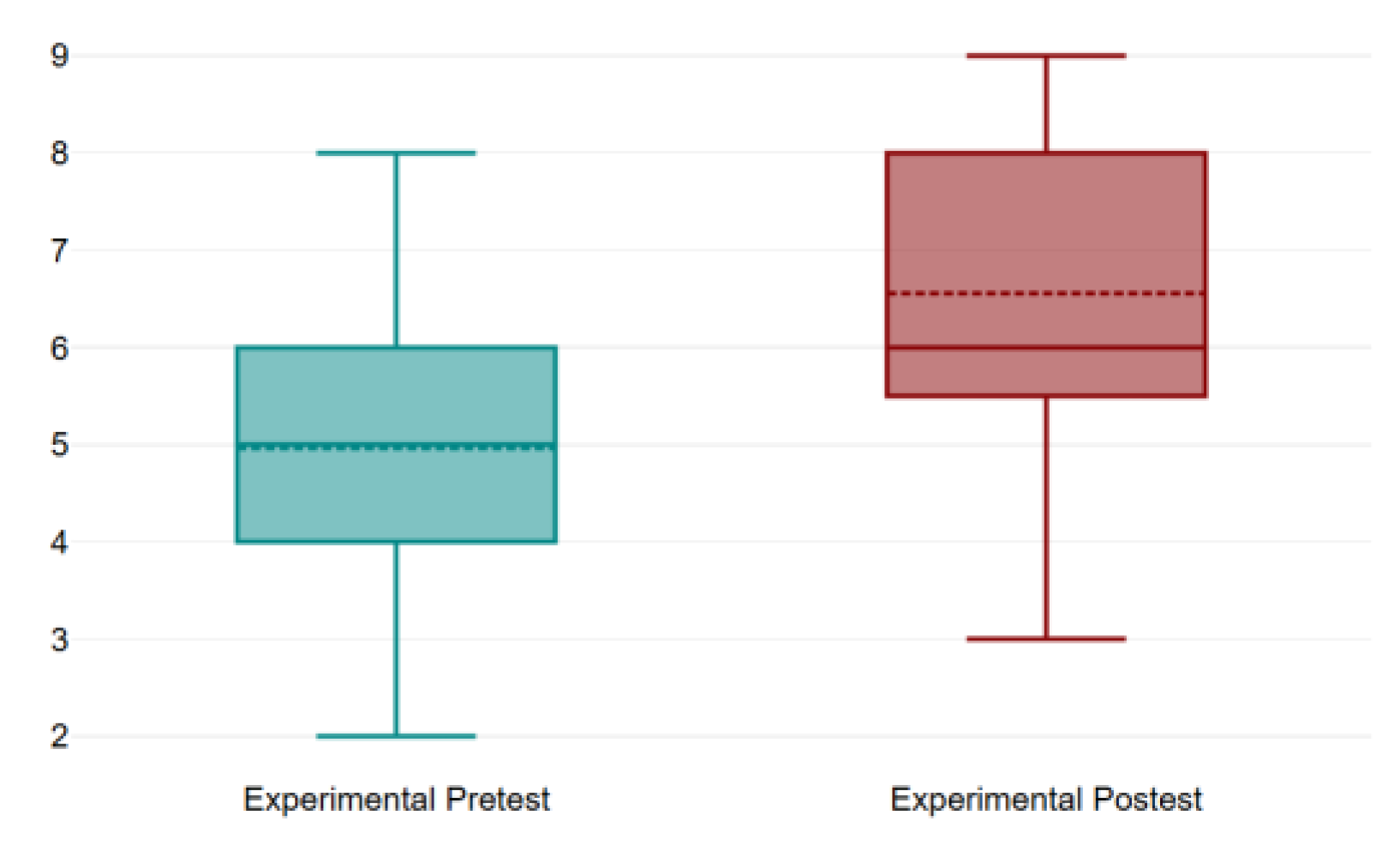

To facilitate data analysis, each question in the questionnaire was evaluated on a scale from one to nine. This evaluation was carried out both in the pretest and the posttest. The collected data were recorded invariables named "Pre_global9" and "Post_global9," detailed in

Table 1 and

Figure 2.

According to the information presented in

Table 1, it can be observed that both groups show an increase in the value of the variable "Post_global9" compared to "Pre_global9," resulting in greater dispersion in both sets.

Figure 4.

Box-Plots for the control test.

Figure 4.

Box-Plots for the control test.

Figure 5.

Box-Plots for the experimental test.

Figure 5.

Box-Plots for the experimental test.

The results obtained from descriptive statistics, presented in

Table 2, indicate that the control group in the pretest exhibits higher values for the dependent variable (mean = 5.36, standard deviation = 1.22) compared to the experimental group in the pretest (mean = 4.96, standard deviation = 1.4). These findings suggest that the control group possesses greater prior knowledge in the investigated field compared to the experimental group.

Subsequently, a Levene test (

Table 3) was conducted to assess whether the variances of the two groups were statistically equal or different. The results indicate a p-value of 0.635, which exceeds the 5% significance level. This suggests that there are no significant differences between the variances of the two groups, supporting the null hypothesis of equal variances.

A two-tailed t-test for independent samples was then conducted, assuming equal variances. The results of this test (

Table 4 and

Table 5) indicate that there is no significant difference between the two groups regarding the dependent variable.

Following a comparison of the initial test data from both groups, an analysis of potential improvement was conducted separately. The results of this comparison are presented in

Table 6, demonstrating a significant improvement in scores between the pretest and posttest in the control group. Similarly, the experimental group also showed a statistically significant improvement concerning the dependent variable.

To ensure a more comprehensive analysis, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to determine whether significant differences exist between the category variable and the dependent variable. The results of this test (F = 8.84, p = <.001) indicate that indeed significant differences exist between the analyzed categories and the dependent variable.

Furthermore, a Bonferroni post hoc test was conducted to compare pairs of groups and determine which ones differed significantly from each other. The results of this test (

Table 7) indicate that each group differs significantly from the others, with a p-value less than 0.05.

4.2. Qualitative Actions

Throughout the working sessions with the students, additional information is gathered through direct observation and open-ended questions, which is not present in the pretest and posttest. Since the results are not intended to be measured with numerical data but rather to enhance the performance of the sessions and activities for consideration by the researcher in future studies. It was initially assumed that the participants possessed the necessary prior knowledge on the topics covered in the activities. Therefore, the objective was to review and support the acquisition of the aforementioned prior knowledge. Additionally, the students had previously worked with the Scratch application in another subject, where they carried out group projects aimed at programming character movements, thus they were familiar with the proposed application.

During the first contact session where teachers explain and provide informative documents to inform the students and their families, an atmosphere of interest and participation by the students is conceived. In the first session of the research, the students shared their questions about the development of the different activities, the questionnaires, and the origin of this work. The good dynamics they show when facing this novelty for them are observed in these questions. They are also presented with the corresponding pretest and how to carry it out. They are emphasized that they should not put their name or any data that identifies them. This initially generates a lot of confusion when establishing their code, but through some examples and help, they manage to apply it without major difficulty.

Once the first session is successfully completed, the second session addresses greater complications for the groups. The control group, which works through gamification activity, receives the corresponding instructions for the proper use and development of the activity. At the beginning, doubts arise, but when they have been playing for a while, they solve them themselves during the game. At some points, the researcher participates to complement information that they need or do not have very clear. The session proceeds normally, and a great participation of all the students is observed, highlighting the collaboration of the members to generate an adequate atmosphere of study and fun. The experimental group, which addresses the activities carried out with Scratch, experiences different problems that affect the proper development of the activity. On the day scheduled for the session, the activity cannot be carried out due to the internet failure at the school. This generates the need to reschedule it. Once a new day is established for this session, the students receive the corresponding talk for it. The students participate in it, and it is observed that gradually various problems are emerging. In the activities of joining, some students observe how the elements established for joining get stuck, and this prevents them from advancing in the session. After trying several options, they are instructed that when this happens to them, they should restart the activity. In the question activities, they were told the importance of spelling mistakes, which gave them an error in some questions, even if the result was correct. Some students emphasize the time used in the sessions because they have not been able to finish all the activities, but other students have had time left over.

At the end of the sessions, a distinction is made within the two groups, despite having the same time, there are users who have not shown any difficulty, they have even been able to help their classmates, and a small group has had greater difficulties in the development of these. In the last session, after completing the posttest by the participants, the students received three questions that allowed them to anonymously express their experiences and opinions about the activity. The questions used to obtain this information were as follows:

What did you think of the approach and development of the practice?

Would you prefer this method to evaluate your knowledge?

What would you change or add to improve this activity?

It was not mandatory to answer the questions, but each one could freely leave feedback to collaborate in the improvement. Many students left their opinion providing a different point of view for the researcher. Within the experimental group, the most common responses were related to breaking out of the routine. This method of evaluation seemed more dynamic and fun to them because they did not feel that their prior knowledge was being assessed. They saw it as a tool for practicing and improving much more playfully, thus avoiding entering the monotony of paper. They did emphasize that they would have liked to work in groups or pairs to collaborate more among their peers and not do it alone. They found it interesting to delve into code programming by observing the different blocks used to generate new functions. Some asked if they could modify it to give their approach or to orient it in other areas. In the control group, the vast majority of responses focused on two fundamental aspects: teamwork and ease of acquiring knowledge. By establishing groups, the students emphasized the feeling of cooperation and participation of all members to win the game. Additionally, they mentioned that they remembered the studied knowledge more fluently and debated with arguments related to the topic. They also identified that the use of cards and different functions such as time allows them greater interaction and enjoyment of the game.

5. Discussing and Conclussion

The main objective of the study is to evaluate the contents learned by students through the utilization of the Scratch tool, examining its potential in the processes of learning assessment and student development. This research was conducted in the subject of "Biology and Geology," chosen due to its highly visual nature and suitability for dynamic activities.

The results reveal that both the control and experimental groups start from different levels of knowledge regarding the proposed subject matter. It indicates that the control group begins with higher scores in the pretest concerning the dependent variable. However, upon conducting various tests to verify the results, it is found that the sample lacks statistical significance, and the hypothesis that all group variances are equal is upheld. Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated that the variance regarding the pretest of both groups is not statistically significant. However, both results were separately verified with their respective post-tests conducted at the end of the study.

The initial conclusion drawn from the results is that both groups have improved their knowledge of the taught material. This improvement is not only evident in the mean scores of both groups but also in their proficiency in completing the post-test. The improvement has been quite significant when comparing the initial and final assessments. Both groups achieve a similar average, despite differing prior knowledge.

Regarding the questions related to student opinions about the activity, it can be affirmed that, despite being in different groups, they reach very similar conclusions. The experimental group highlights the positive experience of working collaboratively and engaging with their classmates. They believe that learning through play and teamwork are key to facilitating the knowledge acquisition process. In contrast, the control group misses the cooperation with their classmates during the activity. They acknowledge the utility and entertainment offered by the use of Scratch but express a preference for conducting the activity in groups, basing their responses on the idea of cooperating to participate collectively in their learning process rather than facing it alone.

Regarding the session's development, it is worth noting that the main difficulty encountered was resolving technical issues that arose during programming due to the high number of students, the limitation of having only one computer class for the entire school, and technical issues caused by internet connections.

Regarding the impact of the intervention, it is indicated that the feedback received from the participants has facilitated improvement in the development of new ideas for future research and has confirmed the potential use of the Scratch application in the classroom. The effort made to obtain favorable evaluation from the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos is emphasized, as studies involving minors have stringent requirements, and compliance with them requires additional effort and time during the study's preparation. Failure to comply could result in the necessary delay in the research until validity is obtained.

After obtaining the results of the study, the questions that were asked at the beginning of the study can be answered.

RQ1: What is the impact of using the Scratch tool on student learning and development?

The study indicates that the utilization of Scratch has a positive impact on student learning and development. Both the control and experimental groups showed significant improvement in their knowledge of the material, as evidenced by higher post-test scores compared to pre-test scores. The experimental group, in particular, highlighted the benefits of collaborative learning and engagement facilitated by Scratch, suggesting enhanced knowledge acquisition through interactive and dynamic activities.

RQ2: What level of knowledge and training do both teachers and students require to maximize the benefits of Scratch?

The research does not explicitly detail the level of knowledge and training required for teachers and students. However, it notes that resolving technical issues during programming was a challenge due to limited resources and technical difficulties, implying the need for adequate training and preparation for both teachers and students to effectively utilize Scratch in the classroom.

RQ3: How does the integration of innovative technologies influence student motivation and engagement?

The integration of innovative technologies like Scratch positively influences student motivation and engagement. The experimental group particularly appreciated the collaborative and playful learning environment, which they found key to facilitating knowledge acquisition. This suggests that innovative technologies can significantly enhance student engagement and motivation by making learning more interactive and enjoyable.

RQ4: What differences in effectiveness were observed between the use of Scratch and gamification to teach the same content?

The study did not directly compare the effectiveness of Scratch with other gamification methods for teaching the same content. However, it compared the experiences of the control group, which used traditional methods, with the experimental group using Scratch. While both groups showed similar overall improvement, the experimental group noted the positive aspects of collaborative and playful learning, which were less emphasized by the control group.

RQ5: What best pedagogical practices have been identified to promote active and meaningful learning?

The study identifies several best pedagogical practices to promote active and meaningful learning, including:

Collaborative learning: Encouraging students to work together and engage with peers, as emphasized by the experimental group's feedback.

Interactive and dynamic activities: Using tools like Scratch to create engaging, hands-on learning experiences.

Redesigning activities for better playability and interest: Enhancing the quality and playability of Scratch activities to captivate students' interest and explore their learning processes.

Promoting cooperative learning: Shifting from individualistic to cooperative game dynamics to encourage mutual assistance and knowledge sharing among students.

Increasing the number of work sessions: Allowing more time for students to acquire the proposed study content and to address any setbacks encountered during the learning process.

Regarding future lines of work, it is proposed, first, to redesign the activities developed with Scratch to enhance their quality and playability, thus captivating students' interest and exploring their learning processes. Second, the idea of changing the game dynamics to seek a system of cooperation instead of individuality is suggested. This would encourage students to assist each other and strengthen their knowledge by explaining and resolving their classmates' doubts. Finally, increasing the number of work sessions to improve the acquisition of the proposed study and allow for resolving any setbacks that may arise during the researcher's proposed sessions.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, E.S. and R.H.N; methodology, E.S and R.H.N; software, , E.S. and R.H.N validation, , E.S. and R.H.N.; formal analysis, , E.S. and R.H.N.; investigation, E.S. and R.H.N.; resources, E.S. and R.H.N.; data curation, E.S. and R.H.N.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S. and R.H.N.; writing—review and editing, E.S. and R.H.N.; visualization, E.S. and R.H.N; supervision, R.H.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by research Grants PID2022-137849OB-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ERDF, EU.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Research Ethics Committee of the Rey Juan Carlos University with internal registration number 2802202310023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, O., Lee, H., Hofstetter, C., & Linn, M. (2008). Evaluación de la integración del conocimiento en la ciencia: constructo, medidas y evidencia. Evaluación Educativa, 13, 33 - 55. [CrossRef]

- Moeed, A. (2015). Evaluación de la Investigación Científica., 41-56. [CrossRef]

- Stern, L., & Ahlgren, A. (2002). Análisis de las evaluaciones de los estudiantes en los materiales curriculares de la escuela intermedia: Apuntando precisamente a los puntos de referencia y estándares. Revista de Investigación en Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 39, 889-910. [CrossRef]

- Stăncescu, I. (2017). La importancia de la evaluación en el proceso educativo - Perspectiva de los profesores de ciencias. , 753-759. [CrossRef]

- Lovelace, M., & Brickman, P. (2013). Mejores prácticas para medir las actitudes de los estudiantes hacia el aprendizaje de las ciencias. Educación en Ciencias de la Vida de la EBC, 12, 606 - 617. [CrossRef]

- Tretter, T., Brown, S., Bush, W., Saderholm, J., & Holmes, V. (2013). Evaluaciones de contenido de ciencias válidas y confiables para profesores de ciencias. Revista de Formación de Profesores de Ciencias, 24, 269-295. [CrossRef]

- Fagerlund, J., Häkkinen, P., Vesisenaho, M., & Viiri, J. (2020). Pensamiento computacional en programación con Scratch en escuelas primarias: Una revisión sistemática. Aplicaciones informáticas en la enseñanza de la ingeniería, 29, 12 - 28. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Colón, A., & Romo, J. (2016). Enseñanza con Scratch en Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn., 11, 67-70. [CrossRef]

- Valverde-Berrocoso, J., Acevedo-Borrega, J., & Cerezo-Pizarro, M. (2022). Tecnología Educativa y Desempeño de los Estudiantes: Una Revisión Sistemática., 7. [CrossRef]

- Escueta, M., Nickow, A., Oreopoulos, P., & Quan, V. (2020). Actualización de la educación con tecnología: perspectivas de la investigación experimental. Revista de Literatura Económica, 58, 897-996. [CrossRef]

- An, T., & Oliver, M. (2020). ¿Qué es la tecnología educativa? Repensar el campo desde la perspectiva de la filosofía de la tecnología. Aprendizaje, Medios y Tecnología, 46, 6 - 19. [CrossRef]

- Adell Segura, J. (1997). Tendencias en educación en la sociedad de las tecnologías de la información. EDUTEC: Revista electrónica de tecnología educativa. http://hdl.handle.net/11162/6072.

- Alban, G. P. G., Arguello, A. E. V., & Molina, N. E. C. (2020). Metodologías de investigación educativa (descriptivas, experimentales, participativas, y de investigación-acción). Recimundo, 4(3), 163-173. http://www.recimundo.com/index.php/es/article/download/860/1363. [CrossRef]

- Arevalo, F. [Fabian Arevalo]. (2020, 26 de agosto). Juego arrastrar y soltar. YouTube. Recuperado el 19 de abril de 2023. https://youtu.be/dPsR06buwg?si=UzhGaz45dsmxO1Hz.

- Barceló Garcia, M. (2014). El fenómeno Scratch. Byte España, (212), 66-66. ARADOJAS (Universo 53- septiembre 1999) (upc.edu).

- Barrachina, C. M. B. Métodos aplicables para un TFT o TFM de carácter performativo. https://scholar.archive.org/work/3c2tdakajjh4pf6epaxh4t3sbq/access/wayback/https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Clara_Maria_Blat/publication/339613098_Metodos_aplicables_para_un_TFT_o_TFM_de_caracter_performativo/links/5e5c2bb3a6fdccbeba124772/Metodos-aplicables-para-un-TFT-o-TFM-de-caracter-performativo.pdf.

- Bayón, J. B. (2015). Formación del profesorado con scratch: análisis de la escasa incidencia en el aula. Opción, 31(1), 164-182. Redalyc.Formación del profesorado con scratch: análisis de la escasa incidencia en el aula.

- Coscollola, M. D., & Agustó, M. F. (2010). Innovación educativa: experimentar con las TIC y reflexionar sobre su uso. Píxel-Bit. Revista de medios y educación, (36), 171-180. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/368/36815128013.pdf.

- Garaje Imagina. (2020, 30 de abril). Juego de preguntas y respuestas con Scratch. YouTube. Recuperado el 26 de abril de 2023. https://youtu.be/daSe-VtxthU?si=U4deTaHzGcJgCYtM.

- Hernández-Nodarse, M. (2017). ¿Por qué ha costado tanto transformar las prácticas evaluativas del aprendizaje en el contexto educativo? Ensayo y crítico sobre una patología pedagógica pendiente de tratamiento. Revista Electrónica Educare, 21(1), 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R., Fernández, C. y Baptista, P. (2010). «1. Definiciones de los enfoques cuantitativo y cualitativo, sus similitudes y diferencias». En Metodología de la investigación (5.ª ed., pp.4-20). México: McGraw-Hill.

- Hurtado, M. J. R., & Silvente, V. B. (2012). Cómo aplicar las pruebas paramétricas bivariadas t de Student y ANOVA en SPSS. Caso práctico. Reire, 5(2), 83-100.https://www.academia.edu/download/62285491/articulo_Vanesa20200305-56077-1omgwka.pdf.

- Izquierdo, M. (2014). LOS MODELOS TEÓRICOS EN LA "ENSEÑANZA DE CIENCIAS PARA TODOS" (ESO, NIVEL SECUNDARIO). Recuperado de: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12209/3989.

- Pàmies, Mª del M., Ryan, G. y Valverde, M. (2017). «7. Diseño de la investigación». En O. Amat y G. Rocafort (Dir.), Cómo investigar: Trabajo fin de grado, tesis de máster, tesis doctoral y otros proyectos de investigación (pp.113-123). Barcelona: Profit Editorial. ISBN: 978-84-16904-69-3.

- Pérez-Tavera, I. H. (2019). Scratch en la educación. Vida Científica Boletín Científico de la Escuela Preparatoria No. 4, 7(13). https://repository.uaeh.edu.mx/revistas/index.php/prepa4/article/download/3588/5413.

- Rodríguez Sabiote, C., Herrera Torres, L., & Lorenzo Quiles, O. (2005). Teoría y práctica del análisis de datos cualitativos. Proceso general y criterios de calidad. http://148.202.167.116:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/1038.

- An, H., & Oliver, K. (2020). Integrating technology in the classroom: The effectiveness of a professional development program for practicing teachers. Computers & Education, 145, 103699. [CrossRef]

- Clark, D. B., Tanner-Smith, E. E., & Killingsworth, S. S. (2016). Digital games, design, and learning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 86(1), 79–122. [CrossRef]

- Escueta, M., Nickow, A. J., Oreopoulos, P., & Quan, V. (2020). Technology and education: Computers, software, and the Internet. Annual Review of Economics, 12(1), 631–658.

- Livingstone, S., Stoilova, M., & Nandagiri, R. (2019). Children and the Internet: A global perspective. In N. Blumberg (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Media and Migration (pp. 145–161). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Loui, M. C. (2005). Technology and the law: Is Google a Fourth Amendment “Search Engine”?: The search for a solution to protect privacy while letting technology evolve. Journal of Law, Technology and Policy, 1, 117–154.

- Robinson, L., Cotten, S. R., Ono, H., Quan-Haase, A., Mesch, G., Chen, W., Schulz, J., Hale, T. M., Stern, M. J., & Stern, M. J. (2020). Digital inequalities and why they matter. Information, Communication & Society, 23(5), 700–714.

- Scherer, R., Siddiq, F., & Tondeur, J. (2019). The technology acceptance model (TAM): A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach to explaining teachers’ adoption of digital technology in education. Computers & Education, 128, 13–35. [CrossRef]

- Valverde-Berrocoso, J., Acevedo-Borrega, M., & Cerezo-Pizarro, C. (2022). The impact of technology on students’ academic performance: A systematic review. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(1), 6–18. [CrossRef]

- Walkington, C. A. (2013). Using adaptive learning technologies to personalize instruction to student interests: The impact of relevant contexts on performance and learning outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(4), 932–945. [CrossRef]

- González, C. (2019). Gamificación en el aula: ludificando espacios de enseñanza aprendizaje presenciales y espacios virtuales. Researchgate. net, 1-22. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334519680_Gamificacion_en_el_aula_ludificando_espacios_de_ensenanza-_aprendizaje_presenciales_y_espacios_virtuales.

- Lovelace, M., & Brickman, P. (2013). Best practices for measuring students’ attitudes toward learning science. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 12(4), 606-617. [CrossRef]

- Liu, O. L., Lee, H. S., Hofstetter, C. H., & Linn, M. C. (2008). Assessing knowledge integration in science: Construct, measures, and evidence. Educational Assessment, 13(1), 33-55. [CrossRef]

- Moeed, A. (2015). Assessment in science education. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(6), 104-108.

- Stăncescu, V. (2017). Feedback in learning: Reciprocity in teaching and learning processes. Social Sciences, 6(3), 75.

- Stern, J. L., & Ahlgren, A. (2002). Learning to teach science: Exploring the power of subject matter courses. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 39(4), 313-340.

- Malinverni, L., Giacomin, M., & Storti, G. (2018). Integrating Scratch in Mathematics Education: A Comprehensive Review. In D. Ifenthaler, Y. J. Kim, & R. M. Spector (Eds.), Learning Technologies for Transforming Teaching, Learning and Assessment (pp. 247-269). Springer.

- Caballé, S., Clarisó, R., & Rodríguez-Ardura, I. (2017). On the Impact of Scratch on the Improvement of Programming Skills and Self-Efficacy. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy (iJEP), 7(3), 26-37.

- Sáez-López, J. M., Román-González, M., & Vázquez-Cano, E. (2016). Scratch in Education: A Review of the Literature. Computers & Education, 104, 71-83.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).