Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How does the integration of gamification in mBlock learning influence students’ computational thinking abilities?

- (2)

- How does incorporating gamification into the mBlock learning environment influence students’ learning motivation?

- (3)

- What are the outcomes in terms of student achievement after engaging with mBlock through gamification?

- (4)

- What is the relationship between computational thinking, learning motivation, and programming achievement when students engage with mBlock through gamification?

2. Literature Review

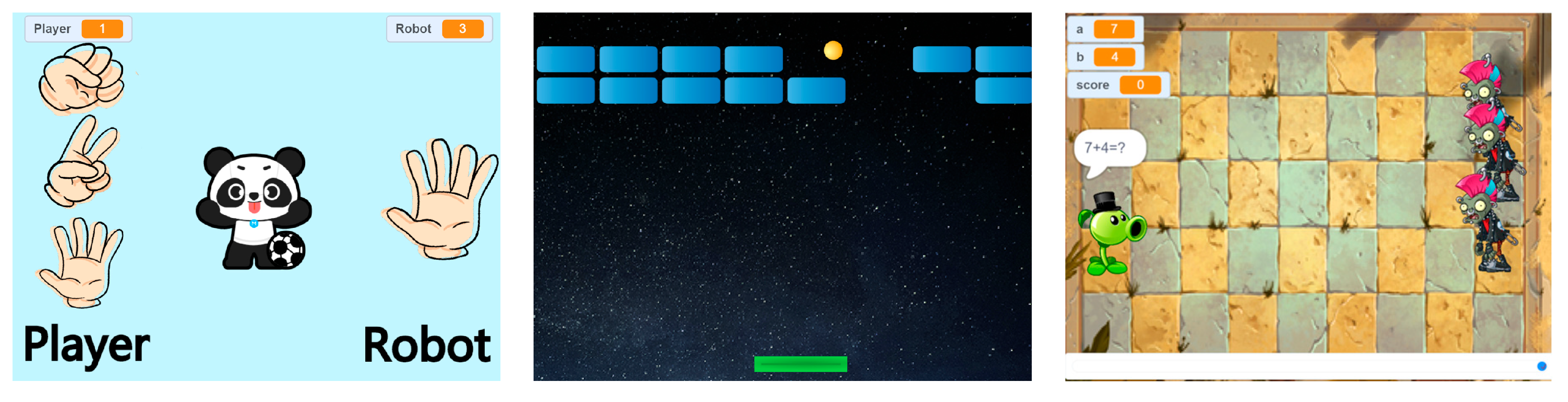

2.1. Gamification, Serious Games and Programming Learning

2.2. Computational Thinking

2.3. Learning Motivation

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participants

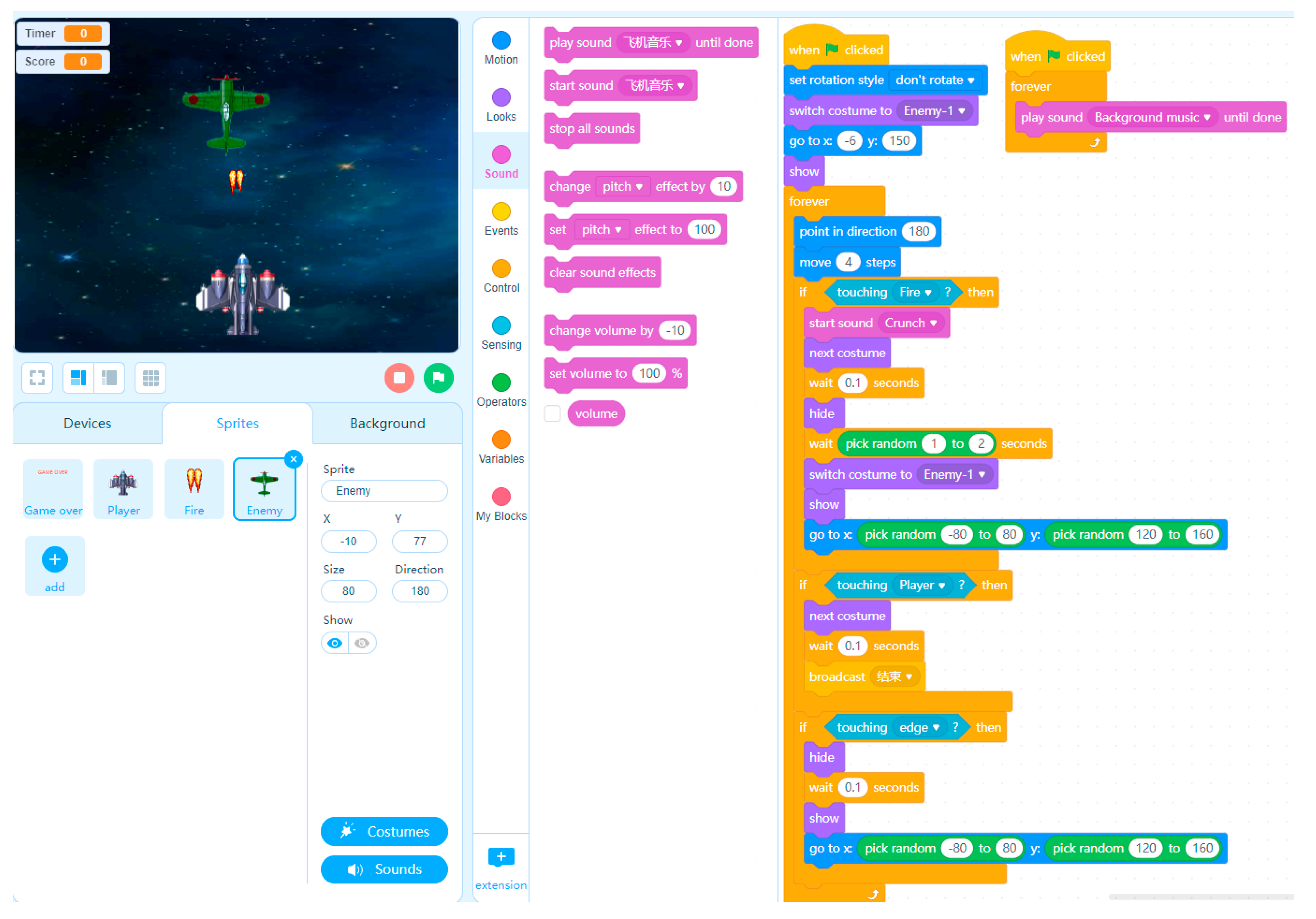

3.3. Implementation of Experiment

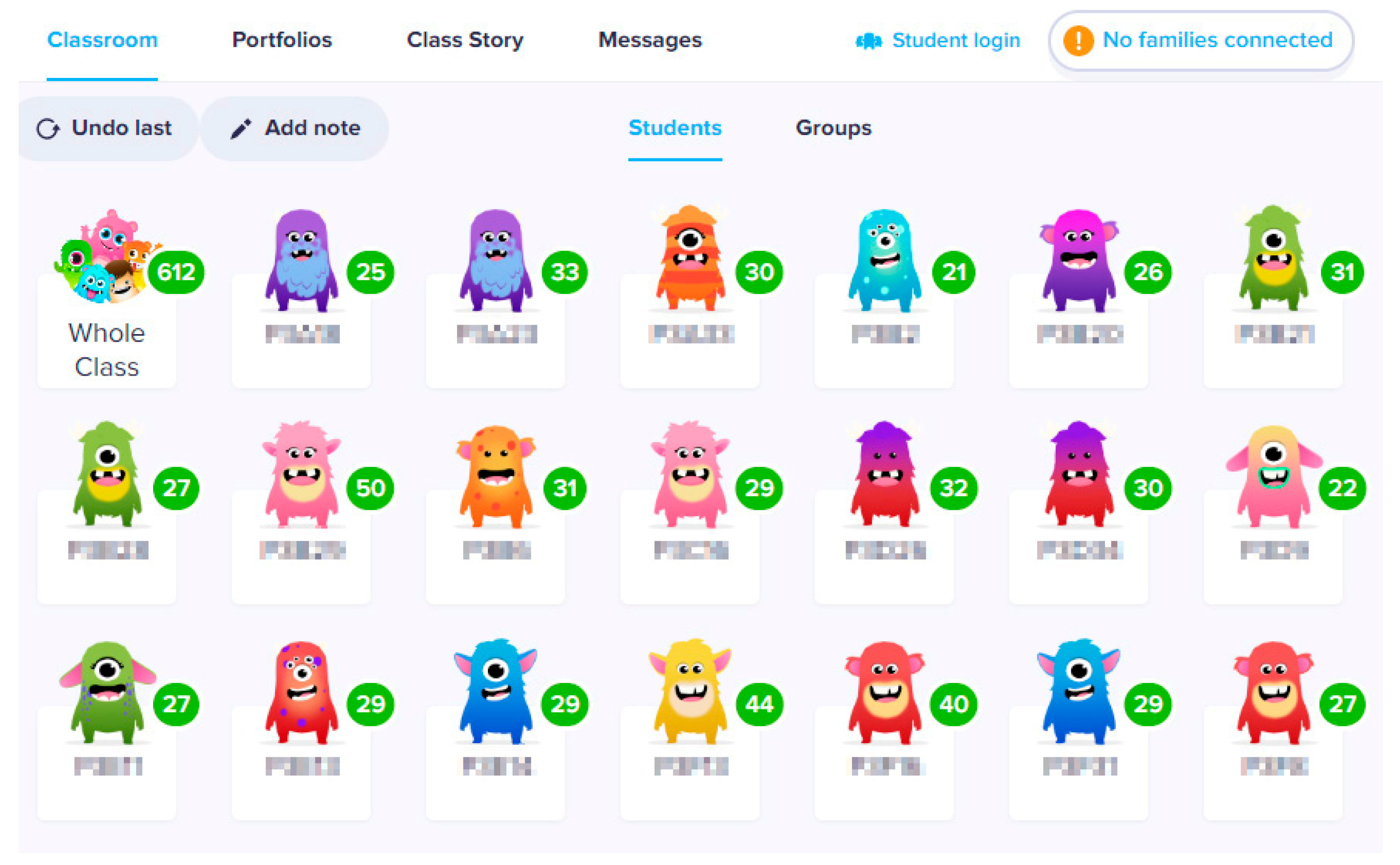

3.4. Integrating Classdojo for Engagement

3.5. Instruments

3.5.1. Programming Computational Thinking Scale (PCTS)

3.5.2. Instructional Materials Motivation Survey (IMMS)

3.5.3. Programming Achievement Test (PAT)

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results

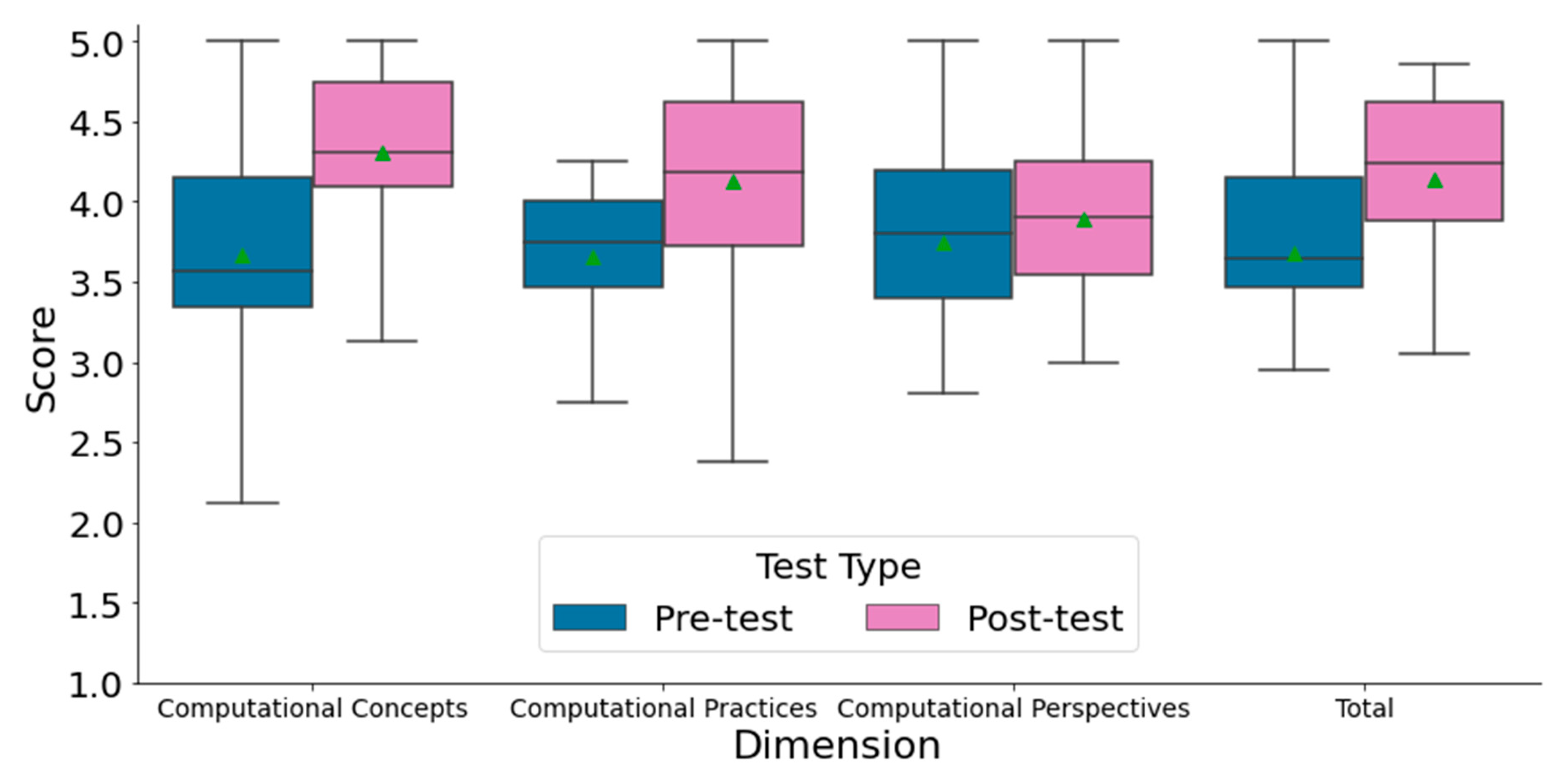

4.1. Analysis of Computational Thinking

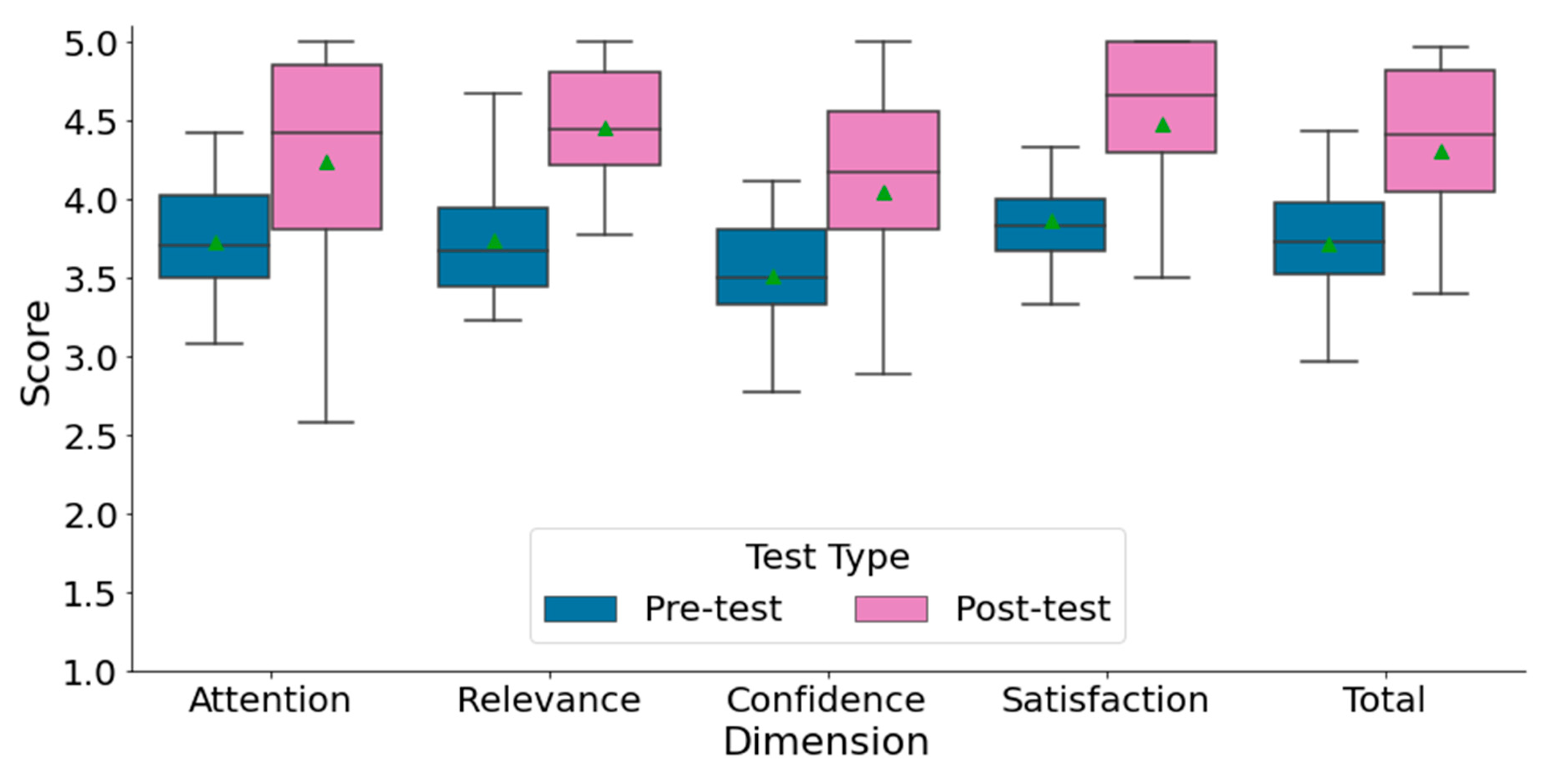

4.2. Analysis of Learning Motivation

4.3. Analysis of Programming Achievement

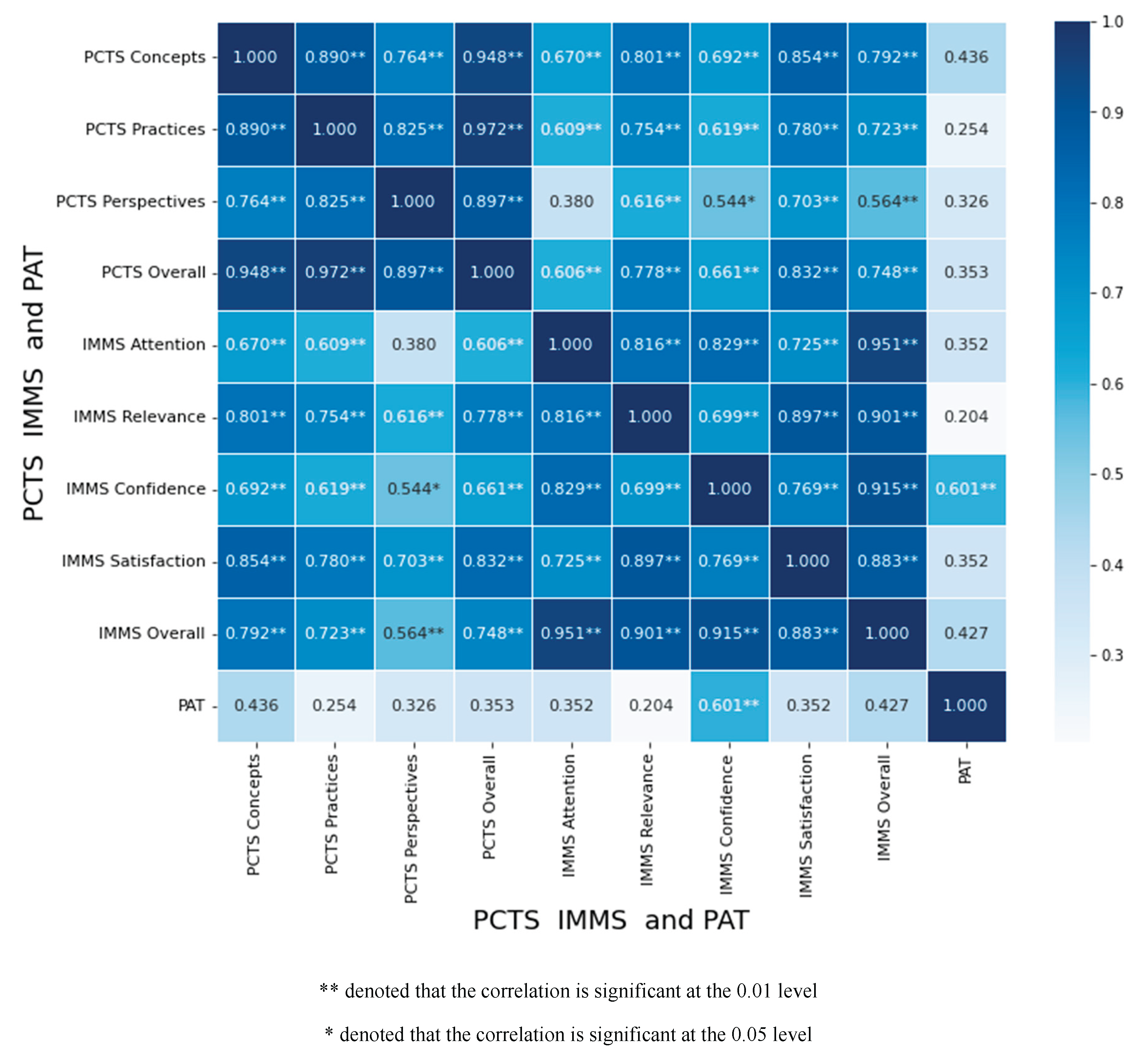

4.4. Correlation Between Computational Thinking, Learning Motivation, and Programming Achievement

4.4.1. Significant Correlations Within PCTS Dimensions

4.4.2. Significant Correlations Within IMMS Dimensions

4.4.3. Significant Correlations Between PCTS and IMMS Dimensions

4.4.4. Overall PCTS and IMMS Correlation

4.4.5. Correlation Between PCTS, IMMS, and PAT

5. Discussion

5.1. RQ1) How Does the Integration of Gamification in mBlock Learning Influence Students’ Computational Thinking Abilities?

5.2. RQ2) How Does Incorporating Gamification into the mBlock Learning Environment Influence Students’ Learning Motivation?

5.3. RQ3) What Are the Outcomes in Terms of Student Achievement After Engaging with mBlock Through Gamification?

5.4. RQ4) What Is the Relationship Between Computational Thinking, Learning Motivation, and Programming Achievement When Students Engage with mBlock Through Gamification?

6. Conclusions

References

- A. Robins, J. Rountree, and N. Rountree, ‘Learning and teaching programming: A review and discussion’, Computer science education, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 137–172, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhan, L. He, Y. Tong, X. Liang, S. Guo, and X. Lan, ‘The effectiveness of gamification in programming education: Evidence from a meta-analysis’, Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, vol. 3, p. 100096, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Weintrop, ‘Block-based programming in computer science education’, Commun. ACM, vol. 62, no. 8, pp. 22–25, July 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Brennan and M. Resnick, ‘New frameworks for studying and assessing the development of computational thinking’, in Proceedings of the 2012 annual meeting of the American educational research association, Vancouver, Canada, 2012, p. 25.

- T. Jenkins, ‘On the difficulty of learning to program’, in Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Conference of the LTSN Centre for Information and Computer Sciences, Citeseer, 2002, pp. 53–58.

- J. Du, H. Wimmer, and R. Rada, ‘“ Hour of Code”: Can It Change Students’ Attitudes Toward Programming?’, Journal of Information Technology Education: Innovations in Practice, vol. 15, p. 53, 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Du Boulay, ‘Some difficulties of learning to program’, Journal of Educational Computing Research, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 57–73, 1986.

- J. Boustedt et al., ‘Threshold concepts in computer science: do they exist and are they useful?’, ACM Sigcse Bulletin, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 504–508, 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Agapito, M. Rodrigo, and T. Mercedes, ‘Designing an intervention for novice programmers based on meaningful gamification: An expert evaluation’, 2017.

- N. Zeybek and E. Saygı, ‘Gamification in Education: Why, Where, When, and How?—A Systematic Review’, Games and Culture, p. 155541202311586, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Maryono, S. Budiyono, and M. Akhyar, ‘Implementation of Gamification in Programming Learning: Literature Review’, Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. C. Choi and I. C. Choi, ‘Investigating the Effect of the Serious Game CodeCombat on Cognitive Load in Python Programming Education’, in 2024 IEEE World Engineering Education Conference (EDUNINE), IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- D. Pérez-Jorge and M. C. Martínez-Murciano, ‘Gamification with Scratch or App Inventor in Higher Education: A Systematic Review’, Future Internet, vol. 14, no. 12, p. 374, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. J. Agbo, S. S. Oyelere, J. Suhonen, and T. H. Laine, ‘Co-design of mini games for learning computational thinking in an online environment’, Education and Information Technologies, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 5815–5849, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Yadav and S. S. Oyelere, ‘Contextualized mobile game-based learning application for computing education’, Education and Information Technologies, vol. 26, pp. 2539–2562, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Baytak and S. M. Land, ‘An investigation of the artifacts and process of constructing computers games about environmental science in a fifth grade classroom’, Educational Technology Research and Development, vol. 59, pp. 765–782, 2011. [CrossRef]

- K. Gross and S. Gross, ‘Transformation: Constructivism, design thinking, and elementary STEAM’, Art Education, vol. 69, no. 6, pp. 36–43, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. B. Kafai and Q. Burke, ‘Constructionist gaming: Understanding the benefits of making games for learning’, Educational psychologist, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 313–334, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Bullon, A. H. Encinas, M. J. S. Sanchez, and V. G. Martinez, ‘Analysis of student feedback when using gamification tools in math subjects’, in 2018 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Tenerife: IEEE, Apr. 2018, pp. 1818–1823. [CrossRef]

- V. Panthalookaran, ‘Gamification of physics themes to nurture engineering professional and life skills’, in 2018 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Tenerife: IEEE, Apr. 2018, pp. 931–939. [CrossRef]

- A. H. S. Metwally and W. Yining, ‘Gamification in massive open online courses (MOOCs) to support chinese language learning’, in 2017 International Conference of Educational Innovation through Technology (EITT), IEEE, 2017, pp. 293–298.

- D. Dicheva, C. Dichev, G. Agre, and G. Angelova, ‘Gamification in education: A systematic mapping study’, Journal of educational technology & society, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 75–88, 2015.

- S. de Sousa Borges, V. H. Durelli, H. M. Reis, and S. Isotani, ‘A systematic mapping on gamification applied to education’, in Proceedings of the 29th annual ACM symposium on applied computing, 2014, pp. 216–222.

- I. Caponetto, J. Earp, and M. Ott, ‘Gamification and education: A literature review’, in European Conference on Games Based Learning, Academic Conferences International Limited, 2014, p. 50.

- M. F. Areed, M. A. Amasha, R. A. Abougalala, S. Alkhalaf, and D. Khairy, ‘Developing gamification e-quizzes based on an android app: the impact of asynchronous form’, Education and Information Technologies, vol. 26, pp. 4857–4878, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Vaquero, ‘Gamificación y juegos serios en Educación Superior.’, in IV Congreso Virtual Internacional sobre Innovación Pedagógica y Praxis Educativa INNOVAGOGÍA 2018: libro de actas. 20, 21 y 22 de marzo 2018, AFOE. Asociación para la Formación, el Ocio y el Empleo, 2018, p. 100.

- J. M. Wing, ‘Computational thinking’, Commun. ACM, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 33–35, Mar. 2006. [CrossRef]

- D. Hemmendinger, ‘A plea for modesty’, ACM Inroads, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 4–7, June 2010. [CrossRef]

- W. C. Choi, I. C. Choi, and C. I. Chang, ‘Improving computational thinking through flipped classroom: A case study on K-12 programming course in Macao.’, International Research Journal of Science, Technology, Education, & Management (IRJSTEM), vol. 4, no. 3, 2024.

- W. C. Choi and C. I. Chang, ‘The Students’ Perspective on Computational Thinking through Flipped Classroom in K-12 Programming Course’, in Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Education and Multimedia Technology, 2024, pp. 106–113.

- W. C. Choi, ‘The Influence of Code.org on Computational Thinking and Learning Attitude in Block-Based Programming Education’, in Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Education and E-Learning, Yamanashi Japan: ACM, Nov. 2022, pp. 235–241.

- W. C. Choi and I. C. Choi, ‘The Influence and Relationship between Computational Thinking, Learning Motivation, Attitude, and Achievement of Code.org in K-12 Programming Education’, arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.14180, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Aldrich, Learning online with games, simulations, and virtual worlds: Strategies for online instruction. John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

- J. D. Bayliss and S. Strout, ‘Games as a” flavor” of CS1’, in Proceedings of the 37th SIGCSE technical symposium on Computer science education, 2006, pp. 500–504.

- W. C. Choi and I. C. Choi, ‘Discovering Programming Talent and Improving Learning Motivation with CodeCombat in K-12 Education’, in 2024 IEEE World Engineering Education Conference (EDUNINE), IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- B. Huang and K. F. T. Hew, ‘Measuring learners’ motivation level in massive open online courses’, International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Law, S. Geng, and T. Li, ‘Student enrollment, motivation and learning performance in a blended learning environment: The mediating effects of social, teaching, and cognitive presence’, Computers & Education, vol. 136, pp. 1–12, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Kazimoglu, ‘Enhancing confidence in using computational thinking skills via playing a serious game: A case study to increase motivation in learning computer programming’, IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 221831–221851, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Leutenegger and J. Edgington, ‘A games first approach to teaching introductory programming’, in Proceedings of the 38th SIGCSE technical symposium on Computer science education, 2007, pp. 115–118. [CrossRef]

- T. Barnes, H. Richter, E. Powell, A. Chaffin, and A. Godwin, ‘Game2Learn: building CS1 learning games for retention’, in Proceedings of the 12th annual SIGCSE conference on Innovation and technology in computer science education, 2007, pp. 121–125.

- M. Muratet, P. Torguet, F. Viallet, and J.-P. Jessel, ‘Experimental feedback on Prog&Play: a serious game for programming practice’, in Computer graphics forum, Wiley Online Library, 2011, pp. 61–73. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Keller, ‘Motivation and instructional design: A theoretical perspective’, Journal of instructional development, pp. 26–34, 1979. [CrossRef]

- Ş. Büyüköztürk, E. Kılıç Çakmak, Ö. E. Akgün, Ş. Karadeniz, and F. Demirel, Scientific research methods, 3rd edn. Ankara: PegemA, 2008.

- Classdojo, ‘What’s ClassDojo?’ [Online]. Available: classdojo.com/about/.

- P. Z. Wu, ‘Compilation of Computational Thinking Self-efficacy Scale and Verification of Reliability and Validity’, Taichung University of Education, Taichung, Taiwan, 2021.

- B. Zhong, Q. Wang, J. Chen, and Y. Li, ‘An Exploration of Three-Dimensional Integrated Assessment for Computational Thinking’, Journal of Educational Computing Research, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 562–590, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Keller, ‘The Arcs model of motivational design’, Motivational design for learning and performance: The ARCS model approach, pp. 43–74, 2010.

| N | Pre-Test | Experiment | Post-Test |

| 20 | O1 O2 | E | O3 O4 O5 |

| Dimension | Test | Mean | N | Sd | t | p |

| Computational Concepts | Pre-test | 3.67 | 20 | 0.64 | -3.77 | 0.001 |

| Post-test | 4.31 | 20 | 0.56 | |||

| Computational Practices | Pre-test | 3.66 | 20 | 0.62 | -2.56 | 0.019 |

| Post-test | 4.13 | 20 | 0.68 | |||

| Computational Perspectives | Pre-test | 3.75 | 20 | 0.72 | -0.73 | 0.474 |

| Post-test | 3.89 | 20 | 0.66 | |||

| Total | Pre-test | 3.68 | 20 | 0.62 | -2.72 | 0.014 |

| Post-test | 4.14 | 20 | 0.59 |

| Dimension | Test | N | Mean | SD | t | p |

| Attention | Pre-test | 3.72 | 20 | 0.39 | -3.22 | 0.005 |

| Post-test | 4.24 | 20 | 0.76 | |||

| Relevance | Pre-test | 3.74 | 20 | 0.48 | -5.64 | 0.000 |

| Post-test | 4.46 | 20 | 0.45 | |||

| Confidence | Pre-test | 3.52 | 20 | 0.37 | -3.72 | 0.001 |

| Post-test | 4.05 | 20 | 0.71 | |||

| Satisfaction | Pre-test | 3.87 | 20 | 0.38 | -3.95 | 0.001 |

| Post-test | 4.47 | 20 | 0.66 | |||

| Total | Pre-test | 3.70 | 20 | 0.36 | -4.59 | 0.000 |

| Post-test | 4.28 | 20 | 0.60 |

| Concept | Total | Mean | Correctness Rate |

| Sequences | 10 | 9.70 | 97.0% |

| Parallelism | 10 | 7.30 | 73.0% |

| Events | 10 | 8.20 | 82.0% |

| Conditions | 20 | 14.59 | 73.0% |

| Data | 17 | 14.88 | 87.5% |

| Operators | 20 | 16.01 | 80.1% |

| Loops | 13 | 9.61 | 73.9% |

| Total | 100 | 80.29 | 80.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).