1. Introduction

A common problem in education has always been to get students to achieve an adequate level of motivation and engagement in studying a subject in order to improve academic performance. There are a lot of papers concluding that gamification, usually defined as the use of game thinking and game mechanics and dynamics in non-game environments and applications, has the potential to make learning more engaging, motivating, and satisfactory ([

1,

2,

3]) with the ultimate goal of improving their academic performance ([

4,

5]) and their final grades ([

6]). In this way, an interesting recent meta-analysis of the literature [

7] analyses the results of 32 papers comparing academic performance between groups that use gamification (experimental) and groups that do not (control). This paper concludes that academic performance was significantly better for students in the experimental groups than in the control groups.

However, although it is essential to design gamified experiences thoughtfully, ensuring that they align with educational objectives and promote meaningful learning outcomes, in most of the works using gamification in education, game elements are used without justifying the choice, without methodological approach on how to gamify, which elements should be chosen, or how they are related. Specifically in higher education settings, certain instances of gamified learning have yielded minimal advantages or even negative outcomes ([

8]). Therefore, implementing gamification in education can lead to unintended consequences due to the lack of established design methodologies, and so selecting the appropriate formal process for gamification design has become a crucial factor for success, offering a valuable resource for educational practitioners, gamification designers, and researchers alike.

On the other hand, the design and implementation of gamification in the learning process requires a significant effort ([

9]), and educators often find that the expenses, time commitments, and challenges associated with design and implementation outweigh the anticipated benefits ([

10]).

We can find in the literature several gamification design frameworks and approaches in the field of education. The most important proposals have been collected and analyzed in several recent systematic reviews ([

11,

12,

13]. In addition, each of these review papers highlights some fact that we consider relevant to propose a design framework or approach for gamification in education:

Mora et al. [

11] highlights the

need for a formalisation to guide and support the processes of gamification design.

Saggah et al. [

12] focuses on learning theories and state that integrating gamification into education without establishing a

solid foundation in learning theories could result in an unsatisfactory experience and fail to accomplish educational objectives.

Khaldi et al. [

13] emphasizes that the

appropriate selection and combination of game components continues to be a challenge for gamification designers and practitioners, primarily because proven design methodologies are lacking, and there is not a universally effective approach that can be applied regardless of the gamification scenario.

We also must note that the vast majority of design proposals focus on structural gamification rather than content gamification ([

13,

14]). The difference between them lies on the application scope of the game elements, mechanics or dynamics (points, badges, goals, rewards, progression, status, challenge, feedback, etc.). In the structural gamification, these elements are used to motivate students along a learning itinerary or didactic proposal, and it does not depend on the specific content. Instead, content gamification applies game elements only for a specific content or learning objectives and hence cannot be reused for another different content.

Saggah et al. [

12], and later Khaldi et al. [

13], classify gamification design frameworks into three categories, according to the level of detail:

High-level approachs offer a broad outline of the design procedure, acting as a general directive at a high level that outlines the global stages, without specifying particular game components or implementation details.

Gamification elements guidance refer to design frameworks that focuses on the gamification elements that can be used, generally including implementation guidance.

Scenario-based approaches describe the application of game elements through real empirical studies in real learning environments.

As stated by Khaldi et al., it is worth highlighting that scenario-based approaches are the most specific and therefore difficult to replicate in other environments. In contrast, high-level approaches are the most general and need to be adapted according to the context. Finally, frameworks belonging to the "gamification elements guidance" category can greatly help implement gamified learning environments by providing an useful set of game elements that can be seamlessly integrated into learning environments. Since we are interested in a general framework, not restricted to a specific scenario or setting, we will precisely focus on this latter category because we want to get as close as possible to the design and practical implementation by the teacher in the in Learning Management Systems (LMS), widely used in MOOCs, secondary and higher education.

After analyzing the frameworks classified in this category in the above cited reviews, we can conclude that in most of cases they are really close enough to high-level approaches, since they refer to design stages such as analysis, planning or design, development, implementation, evaluation, etc.([

15,

16]). There are also some papers that present simple frameworks based on the enumeration of different types of game elements commonly used in the literature ([

17]), but they either do not include use guidelines or do not show the relation of the design framework to any theory of learning or motivation.

To sum up, it is clear that there arises a pressing necessity for a structural approach with basis on motivational theory to steer and simplify the gamification design process, and to provide support and guidelines for educators in integrating gamification as a pedagogical tool in a digital learning environment. To fill this gap, we propose APAR, a design framework with the following characteristics:

APAR stands for Actions, Points, Achievements and Rewards, because these are the four elements that we consider essential for gamification in education.

It is based on structural gamification, that is, it does not depend on the learning content or subject.

According to the level of detail, the approach lies under the category "Gamification elements guidance", but at the lower lever, that is, very close to the implementation in digital learning platforms. Although LMSs were designed for learning, and not specifically for gamification, they are increasingly incorporating gamification elements in their latest versions, with Moodle being the LMS that has made the strongest effort.

The design framework will consider motivation theories

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 focus on motivation both intrinsic and extrinsic and the most important theories related to gamification in education. In

Section 3, we describe APAR, our structural design framework for gamification.

Section 4 is devoted to provide guidelines for implementing the design framework in a LMS. Finally, we draw some conclusions in

Section 5.

2. Gamification and Motivation

All definitions of gamification state that the ultimate goal of gamification is motivation. Because of this, when designing a gamified classroom, we must know extremely well what human motivation is like. When we talk about human motivation, we can distinguish between intrinsic motivation, which is innate to the individual and comes from within, and extrinsic motivation, which corresponds to stimulation coming from outside in the form of rewards and incentives.

Intrinsic motivation is that which leads us to do things for the simple pleasure of doing them, for personal satisfaction, and without the need for extrinsic reinforcement. There are several theories related to intrinsic motivation that have been commonly applied in the gamification literature. In the following, we briefly describe those theories that have been considered in our design framework.

According to Goal-Setting Theory (GST) by Locke [

18], goals that are immediate, specific and moderately stringent are more motivating than those that are long term, vaguely defined, or those that are too easy or too difficult. To this end, it is essential to provide immediate feedback so that learners can measure their progress in relation to the goals, and also to let them know if they need to make adjustments in their strategy or dedication.

Self-Efficacy Theory (SET) by Bandura [

19] refers with this concept to confidence in one’s own ability to achieve desired goals and outcomes. Self-efficacy can be increased when the student succeeds in completing series of tasks that allow to perceive progress. Therefore, the design framework must allow students to measure this progress and to have direct feedback on their performance.

According to Social Comparison Theory by Festinger [

20], people evaluate their opinions and abilities in comparison with those of others. There are quite a few studies that point out that upward comparison positively influences students to be more engaged in their learning.

The Operant Conditioning Theory (OCT) by Skinner [

21] argues that a behaviour can be reinforced by the consequences it carries. In this sense, Skinner recommends the reinforcement of intrinsic motivation through the use of extrinsic rewards or incentives.

The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) by Ryan & Deci [

22], that is considered the most important theory of human motivation, is based on the assumption that all humans have three innate (unlearned) psychological needs, which we seek to satisfy for excellent functioning and well-being: Competence, or the need to acquire skill or mastery in those areas of knowledge in which we are interested; Relatedness, or the need to relate to other people; and Autonomy, or the need to be free to be able to make the decisions one considers appropriate at any given moment. The Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET) is a sub-theory of SDT, also due to Deci & Ryan, that focuses on how competence and autonomy is affected by external factors such as rewards, deadlines, evaluations, and other pressures. These external factors can either support or undermine intrinsic motivation, depending on how they are perceived.

Marczewski [

23] proposes his model of intrinsic motivation for gamification, based on the SDT model, but considering an additional need. This fourth element of the Marczewski’s model is the Purpose, previously introduced by Dan Pink [

24], and refers to as the human need to want to give meaning to what we do, and which is closely linked to altruism, help, charity or social compromise. In this way, Marczewski refers to his model as RAMP: Relationship, Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose. An important added value of Marczewski’s work was to relate these four motivators to the types of users (or behaviours) that can be found in a gamified system:

Philanthropists, especially motivated by Purpose.

Achievers, mainly motivated by Mastery.

Socializers, especially motivated by Relatedness.

Free Spirits, mainly motivated by Autonomy.

It is worth mentioning that, in practice, all students have a little of each type of user, although usually one type of behaviour clearly stands out from the others. The RAMP model is now considered a very useful model in the design of gamified systems. Bai et al. [

7] argue that the better academic performance of groups in which gamification techniques were used can be explained by the theories of intrinsic motivation mentioned above. Gamification promotes goal-setting and, as a result, students tend to achieve better results. On the other hand, gamification can satisfy the need for recognition cited in social comparison theory and SDT (need for relatedness). Even operant conditioning theory points to social recognition as a positive external reinforcement. In addition, gamification provides the learner with feedback on their performance, which helps to satisfy the SDT need for mastery.

The fact that Skinner’s operant conditioning studies argue that extrinsic rewards can reinforce intrinsic motivation means that special attention should be paid to extrinsic motivation. Zichermann & Cunningham (2011) identify four types of extrinsic rewards or incentives, ordered according to the priority given by people. This is the well-known SAPS model for extrinsic motivation:

Status: People place the higher value on being able to achieve a position of privilege and recognition above all others.

Access: On a second level, we value having restricted or exclusive access to advantages, spaces, information, resources, elements, etc. to which others do not have access.

Power: Next, we value the ability to exercise some kind of power, rank, command, etc. over others.

Stuff: Finally, it is curious to note that "things", i.e. tangible or material rewards, occupy the last position in terms of preference.

This preference order is also due to the fact that it is common for each element of the pyramid to imply the availability of the elements below it. Status usually implies access, but not the other way around. Access usually implies power, and power is usually accompanied by the possibility of having things.

Zichermann & Cunningham [

25] also consider the relationship between the two types of motivation, indicating that intrinsic motivation is necessary in the medium/long term, but is not always sufficient or explicit. As examples, intrinsic motivation may exist and the person may be aware of it, but it may not be sufficient, and in that case extrinsic motivation may help to enhance it and serve as a trigger (e.g. losing weight or quitting smoking). On the other hand, intrinsic motivation may be hidden or the person may not be aware of it, and extrinsic motivation may help to uncover it and make it explicit (e.g. reading or playing chess).

In the next section we describe our design framework, that takes all these theories into account, mainly the Self-Determination Theory and the models for intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, that is, RAMP and SAPS models.

3. APAR Design Framework: Activities, Points, Achievements and Rewards

As we said in the Introduction section, the main objective of this work is to propose a structural gamification design framework based on motivational theories, that is generalist enough to be implemented in any LMS. We will describe the necessary and essential gamification elements and the interrelationships between them, in order to design a gamified virtual classroom that increases the motivation, engagement and satisfaction in learners with the ultimate goal of improving their academic performance.

With regard to the game elements, several recent systematic reviews ([

13,

26,

27,

28]) found that points, badges and leaderboards (the popular tern known as PBL) are the most used game elements ([

26,

27,

29]), but it is widely accepted that these elements are a good start for creating engagement, but using other deeper game elements or dynamics helps to improve engagement and motivation ([

13,

30,

31]).

The proposed design framework is the result of many years of experience of the first author in successfully applying gamification, both as a teacher in higher education and as a teacher trainer and consultant at all education levels. The remaining authors contributed to the implementation of gamification in LMSs, including the customization of some plugins for Moodle and the development of software for our platform SocialWire [

32]. In addition, they are currently collaborating on the development of tool for the improvement of English pronunciation for children where this design framework has been extensively used.

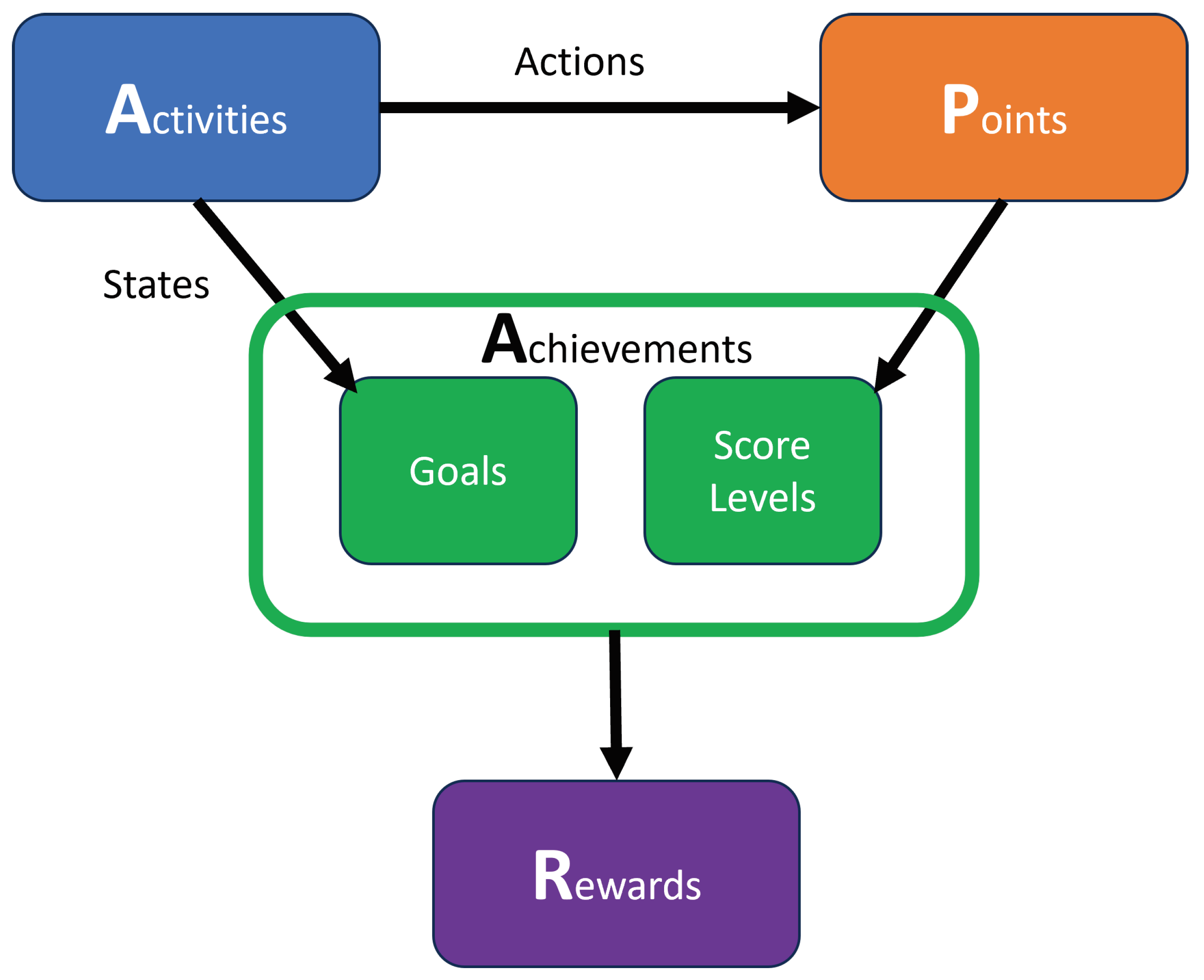

Let’s start by defining the four game elements that we propose for our design framework APAR: Activities, Points, Achievements and Rewards. The sequencing is intentional since the Activities result in Points being earned by students. Points and Activities states allow us to define Achievements as intermediate goals or score levels. And, finally, these Achievements should result in the awarding of Rewards.

Figure 1 shows the different elements of the design framework and their interrelationships.

3.1. Activities

An essential element in any game are challenges, tasks, quests, missions, competitions, races, contests, etc. that must be completed by players. We refer to all these elements as Activities, since they require interaction with the players. In education, these activities will be quizzes, forums, interactive content and different types of tasks or assignments proposed by the teacher to be performed by the learner (individual or in groups, with self- or peer assessment, etc.). These activities will be organized in learning blocks or stages forming a sequential learning pathway.

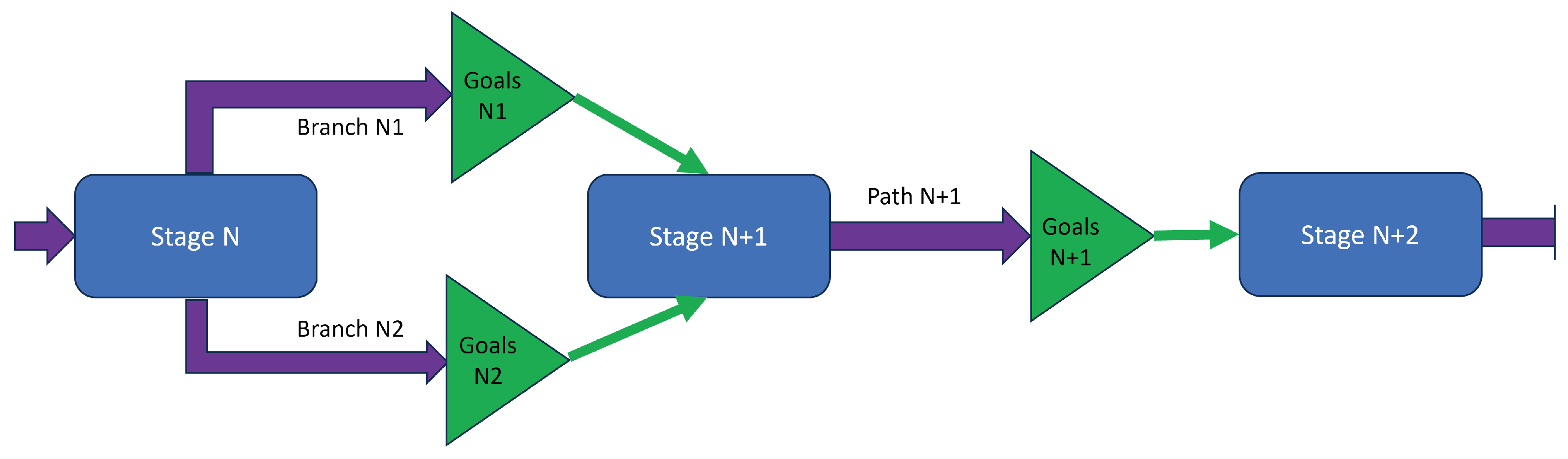

The sequential pathway is also very common in videogames, where players must complete different activities to earn points and progress through the game by achieving intermediate goals. It is also very common that these games are organised in phases or stages (sometimes also called scenarios, chapters, screens or game levels), and players sometimes must overcome an special mandatory challenge (usually called boss battle) that requires a certain difficulty in order to pass or complete the phase. This behaviour can be also emulated in education, and so the phases of the game will be the different skill levels, lessons, topics, didactic units, learning blocks, etc. into which the learning activities of a course are organized. We refer to these sets of activities as Stages, that must also include one o more intermediate goals based on the activities into the stage and, optionally, a final mandatory "boss battle" activity.

Finally, just as in games there may be different paths to reach the end of a phase, a stage may contain different branches between two consecutive stages, that is, different activity sets with the corresponding goals. On the one hand, the use of multipath stages allows reinforcing the autonomy of the students and, on the other hand, allows the teacher to propose paths with types of activity tailored to the type of student (Philanthropist, Achiever, Socializer, Free Spirit), or with different difficulty levels (adaptive learning). Each branch will be associated with the corresponding goal(s).

3.1.1. Actions & States

We will consider two elements related to Activities,

Actions and States, that we can also see in

Figure 1.

Both students and teachers can perform actions on an activity but, like in a game, we are only interested in actions that allow students to earn points. Examples of these actions performed by learners could be starting a discussion or positing a reply in a forum, answering a quiz or a survey, making a submission or, more generally, completing a task. In the case of teachers, the main action that award points to students is grading an activity.

The state of an activity for a learner is usually defined after the activity has been graded.

Pass state is reached when the student get a minimum grade predefined for the activity.

Fail state is reached otherwise.

Outstanding or Top state is reached when the student get one of the highest grades in the activity.

However, since LMSs usually allow teachers specify the conditions that must be met for the completion of an activity, we will also consider the state Completed for a student in an activity. For example, an assignment could be completed simply after submission or, instead, after grading or passing. In the case of a forum activity, completion could require certain number of posts or replies. LMSs also allow to restrict the access to an activity based on the states of previous activities. In this way, the path or a branch in a stage could be optionally configured as a set of sequential activities, where the completion of one activity give access to the next activity.

3.2. Points for Intrinsic Motivation

As previously said, students get points by performing certain actions on activities. These points will be accumulated in a scoreboard. Teachers can decide to display scoreboards in an orderly way, and so the name "leaderboard" is preferred.

In a simple gamification design, we can choose to use a single type of points and all the actions on activities would contribute to points of this type. However, most of the games use several types of points for different reasons. In education, the reason to do it is that learners exhibit a combination of different types of behaviours according the RAMP model (Achievers, Philanthropists, Socialisers and Free spirits), and so we should use different types of points to motivate different types of behaviours. We propose to differentiate between three types of points:

Merit Points (MP) will be used to assess the performance level in certain activities. That is, these points are awarded by teachers like traditional grades. These points will be especially interesting for “achiever” behaviour.

Activity Points (AP) will be used to reward other actions, mainly the completion of activities, regardless of the grade obtained. They can be also used to encourage interactivity with the platform (using the forum, submitting an assignment, starting a discussion, answering a quiz, doing a peer assessment, viewing certain learning content, etc.). In other words, these points will award work and effort, not merit or performance level. In fact, a student can usually get merit and activity points in the same activity. Activity points are attractive for "free spirit" behaviour.

Karma Points (KP) will be awarded by teachers to reward altruism, leadership or significant collaboration in group work, reputation among peers, help in the forums, etc. Karma points are very attractive for philanthropic and socializer behaviour.

3.3. Achievements

According to the motivation theories in

Section 2, teachers should set a number of short-term intermediate goals that students must achieve in order to progress through the course. We refer to these objectives as

Achievements, and We consider two types:

Score Levels: Since students accumulate points in scoreboards, we can define several score levels. Although we can define levels using any type of points, we strongly recommend to use the main score category, that is, the above cited Game or Experience points.

Pathway Goals are intermediate milestones based on the set of activities included in a path or a branch between consecutive stages along the learning pathway. A goal will consist of a set of conditions based on obtaining states "Completed", "Pass" or "Outstanding" in a set of selected activities.

3.4. Rewards for Extrinsic Motivation

Achievements and rewards must be directly related and so each goal or score level achieved should be rewarded. It is also important that rewards are directly related to the extrinsic motivation, and so we must take into account the SAPS model of Zichermann & Cunningham [

25] (see

Section 2):

Status: We consider that Badges are really rewards that grant status and, therefore, must be publicly visible. Similarly, another ’status’ reward is the use of public Leaderboards, as students will, as far as possible, wish to occupy top positions.

Access: Within the type of rewards that grant access, one possibility is to restrict access to the next stage along the learning pathway or to special and exclusive (VIP) resources and activities. Other finalist ‘access’ rewards that are highly valued by students are exclusive advantages in assignments, exams, written tests, etc., such as cheats, extra time, extra attempts at quizzes or homework submissions, etc.

Power: In order to reward our learners with power, we could do so by assigning them roles such as "forum moderator", "group leader", "reviewer", etc.

Stuff: Finally, we can use any other finalist reward, like books, tickets, academic material, or even merit points.

4. Design Guide and Complementary Elements

We propose that the first task for designing a gamified course is to outline a sequence of learning stages. The path between two consecutive stages will be formed by a set of activities, that must be done in a sequential way or not. These activities allow learners to get points and will be used to define the goals for this stage. In the case of a multipath stage, each branch will contain a set the activities and the associated goal(s) (see

Figure 2).

To boost the autonomy of students and besides to offer activities tailored to the student types (Philanthropist, Achiever, Socializer, Free Spirit), we recommend to include some multipath stages.

It should be noted that the advance through the different stages of the course may be self-paced or teacher-paced. The self-paced advance is very common in MOOCs or unattended courses, usually without periodic synchronous teaching. Instead, the teacher-paced progress is generally used in formal education, following the pace of lectures given periodically by a teacher.

Once the stages through the learning pathway has been defined, the next step is to assign Merit and Activity Points to activities. It is obvious that Merit Points are the most important from an academic point of view, and therefore they could be converted to a grade to be used in the calculation of the Final Grade for the course. As an example, if we want Merit Points (MP) to have a weight of 20% in the final grade, we can distribute 200 MP among the main learning activities of the course, so that students see a direct relationship between the MP scoreboard and its contribution to the final grade (by simply dividing the points by 100).

In relation to Activity Points (AP), the implementation in a LMS will typically require a mechanism or module that automatically associate points to events (completing an activity or starting a discussion, for example). We can also make the grade in an optional or special activity counts as activity points.

We also recommend to propose some specific activities to get Karma Points, such as group works, help or debate forums, tasks for constructive criticism, any contest where students can vote, etc.

Although we use different types of points, we propose to use a main category to simplify gamification management. This main type of points, which could be called eXperience Points (XP), will be the most important in the evolution of the game, and the other types of points (MP, AP or KP) will usually contribute to XP with different weights. In this way, we should use a single leaderboard in the course based on XP points. This allows the benefits of social comparison to be obtained in a more playful way and not directly related to academic merit.

Now, it is the moment to configure the achievements. First of all, we should define some score levels based on XP points. Of course, levels based on another type of points are also possible. We must remember that each score level must be associated to a reward.

The next step is to define the goals for each single-path stage, or for the different branches in the case of multipath stages. In the simplest case, the goal for any path could be to complete or pass a final activity, and optionally configure another goal for achieving an outstanding grade in it. If we decide to include more activities in the path, some of then can be used to we can set multiple goals combining their completion, passing or outstanding states.

In order to provide a suitable sense of progress and motivation to the students, we propose to define a large enough set of achievements (stage goals and score levels) that allows students be rewarded on a regular way. To do this, we think that the best option is to use virtual objects as intermediate rewards that can be later exchanged for finalist rewards. We recommend that students collect virtual objects as they reach achievements. Typically at the end of the course, the collected items can be used to purchase meaningful rewards, belonging in this case to the "Access" or "Stuff" types, as seen in

Section 3.4.

In any case, we must take care that the achievements, either score levels or stage goals, are attainable and the periodicity is not too high in order to provide continuous feedback and a greater sense of progress to the students. This also permit to reward learning on a regular basis to increase the motivation of the student.

We must note that a goal must always be associated to one or more rewards (one badge and one virtual object, for example). By default, goals are optional but if one of the rewards associated to a goal is the "Access" to the next stage, then the goal is mandatory. A self-paced course usually includes mandatory goals that unlock the access to stages but, instead, they are not been generally used in teacher-paced courses, where the teacher unlocks stages as related content is explained in the classroom.

4.1. Progress, Feedback and Storytelling

Finally, we must note that a significant number of studies ([

13,

30,

31]) have highlighted that the use of game elements or dynamics like progress, feedback and storytelling usually boost engagement and motivation.

With regard to Progress, it is highly recommended to use some type of graphic that visually displays the progress of the student in the course. For example, a very interesting tool could be a progress bar, or similar, showing the completion state of the activities for one or several stages, or showing the achievement status for the goals. In addition to the leaderboard (for XP points, typically), another element that helps in this task is to display the score levels and allow students to have access to the inventory of virtual objects and badges obtained.

Feedback also plays a crucial role when incorporating gamification into education:

Regular and meaningful feedback is essential in guiding students along their educational itinerary.

Immediate feedback serves as a powerful motivator, allowing students to identify and correct misconceptions early.

Timely feedback provides clarity on students’ progress so that they can assess their performance, identify areas for improvement and adjust their learning strategies accordingly.

Activities and related content can include narrative and Storytelling elements such as characters, plot twists, settings, stories, etc., embedded within the context of a larger storyline, but always in a way that is appropriate to the educational level. This allows the learning content to be presented in the form of a captivating story that engages students and makes them more involved and interested in the content. The storytelling can be extended to the names and images used in the different types of points, goals and rewards (also in badges and virtual objects).

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose a design framework for gamification in education called APAR, which utilizes motivation theories to guide the gamification design process. The approach is structural, that is, content-independent and it focuses on four essential elements: Actions, Points, Achievements, and Rewards. The framework provides a systematic way to design gamified learning experiences that align with educational goals and promote meaningful learning outcomes; and it also offers support and guidelines for teachers to successfully apply gamification as a pedagogical tool in a digital learning environment.

Although different design frameworks has been proposed in the literature, to the best of our knowledge, we think that our proposal is the only one that brings together a set of characteristics that we consider to be of great interest to teachers who want to implement gamification in their classrooms:

It is based on structural gamification, that is, it does not depend on the learning content or subject.

The design framework considers motivation theories.

It is a design approach at the lowest level of detail., that is, very close to the implementation in digital learning platforms.

It offers support and guidelines for teachers to successfully apply gamification in classroom.

Overall, the proposed framework can simplify and steer the gamification design process and provide a valuable resource for educational practitioners, gamification designers, and researchers alike.

Acknowledgments

This work has received financial support from grant TED2021-130283B – C22 financed by MCIN/ AEI 2021ESMECO06122021GCON, and by the Xunta de Galicia (Centro singular de investigación de Galicia accreditation 2022–2025) and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund—ERDF).

References

- Bilro, R.G.; Loureiro, S.M.C.; de Aires Angelino, F.J. The Role of Creative Communications and Gamification in Student Engagement in Higher Education: A Sentiment Analysis Approach. Journal of Creative Communications 2022, 17, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchrika, I.; Harrati, N.; Wanick, V.; Wills, G. Exploring the impact of gamification on student engagement and involvement with e-learning systems. Interactive Learning Environments 2021, 29, 1244–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeybek, N.; Saygı, E. Gamification in Education: Why, Where, When, and How?—A Systematic Review. Games and Culture 2024, 19, 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Castillo, L.; Clavijo-Rodriguez, A.; Hernández-López, L.; De Saa-Pérez, P.; Pérez-Jiménez, R. Gamification and deep learning approaches in higher education. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education 2021, 29, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon-Flores, E.G.; Mena, J.; López-Camacho, E. Gamification as a Teaching Method to Improve Performance and Motivation in Tertiary Education during COVID-19: A Research Study from Mexico. Education Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Martínez, E.; Santos-Jaén, J.M.; Palacios-Manzano, M. Games in the classroom? Analysis of their effects on financial accounting marks in higher education. The International Journal of Management Education 2022, 20, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Hew, K.; Huang, B. Does gamification improve student learning outcome? Evidence from a meta-analysis and synthesis of qualitative data in educational contexts. Educational Research Review 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broer, J. Gamification and the Trough of Disillusionment. In Mensch & Computer 2014 – Workshopband; De Gruyter Oldenbourg: München, 2014; Butz, A., Koch, M., Schlichter, J., Eds.; De Gruyter Oldenbourg: München, 2014; pp. 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamifying learning experiences: Practical implications and outcomes. Computers & Education 2013, 63, 380–392. [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, S.; Gain, J.; Marais, P. A case study in the gamification of a university-level games development course. Proceedings of the South African Institute for Computer Scientists and Information Technologists Conference; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 242–251. [CrossRef]

- Mora, A.; Riera, D.; González, C.; Arnedo-Moreno, J. Gamification: a systematic review of design frameworks. Journal of Computing in Higher Education 2017, 29, 516–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggah, A.; Atkins, A.S.; Campion, R.J. A Review of Gamification Design Frameworks in Education. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Khaldi, A.; Bouzidi, R.; Nader, F. Gamification of e-learning in higher education: a systematic literature review. Smart Learning Environments 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garone, P.; Nesteriuk, S. Gamification and Learning: A Comparative Study of Design Frameworks. Digital Human Modeling and Applications in Health, Safety, Ergonomics and Risk Management. Healthcare Applications; Duffy, V.G., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 473–487. [Google Scholar]

- Yamani, H.A. A Conceptual Framework for Integrating Gamification in eLearning Systems Based on Instructional Design Model. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning 2021, 16, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urh, M.; Vukovic, G.; Jereb, E.; Pintar, R. The Model for Introduction of Gamification into E-learning in Higher Education. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2015, 197, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubhi, M.A.; Sahari, N. A Conceptual Engagement Framework for Gamified E-Learning Platform Activities. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning 2020, 15, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.; Shaw, K.; Saari, L.; Latham, G. Goal setting and task performance: 1969-1980. Psychological Bulletin 1981, 90, 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy 1978, 1, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Human Relations 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, B. Science and Human Behavior; MacMillan: New York, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczewski, A. The intrinsic motivation RAMP. https://www.gamified.uk/gamification-framework/the-intrinsic-motivation-ramp/, 2013.

- Pink, D.H. Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us; Riverhead Books: New York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zichermann, G.; Cunningham, C. Gamification by Design: Implementing Game Mechanics in Web and Mobile Apps; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ekici, M. A systematic review of the use of gamification in flipped learning. Education and Information Technologies 2021, 26, 3327–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannakis, M.; Papadakis, S.; Zourmpakis, A.I. Gamification in Science Education. A Systematic Review of the Literature. Education Sciences 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanzadeh, H.; Farrokhnia, M.; Dehghanzadeh, H.; Taghipour, K.; Noroozi, O. Using gamification to support learning in K-12 education: A systematic literature review. British Journal of Educational Technology 2024, 55, 34–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamified learning in higher education: A systematic review of the literature. Computers in Human Behavior 2018, 87, 192–206. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Ritzhaupt, A.D.; Sommer, M.; Zhu, J.; Stephen, A.; Valle, N.; Hampton, J.; Li, J. The impact of gamification in educational settings on student learning outcomes: a meta-analysis. Educational Technology Research and Development 2020, 68, 1875–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzhaupt, A.D.; Huang, R.; Sommer, M.; Zhu, J.; Stephen, A.; Valle, N.; Hampton, J.; Li, J. A meta-analysis on the influence of gamification in formal educational settings on affective and behavioral outcomes. Educational Technology Research and Development 2021, 69, 2493–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Vieira, M.E.; López-Ardao, J.C.; Fernández-Veiga, M.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.; Herrería-Alonso, S. An open-source platform for using gamification and social learning methodologies in engineering education: Design and experience. Computer Applications in Engineering Education 2016, 24, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).