1. Introduction

The global call for environmental sustainability has significantly reshaped the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industries, driving a shift towards greener and more resource-efficient building practices. This transition has been facilitated by the development and implementation of Green Building Assessment Systems (GBAS), which provide structured methodologies for evaluating the environmental performance of buildings throughout their lifecycle. These systems assess a range of criteria, including energy and water efficiency, indoor environmental quality, materials usage, waste management, and carbon emissions, thereby promoting sustainable design and construction practices [

1,

2]. Across the world, various GBAS frameworks such as LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) in the United States, BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method) in the United Kingdom, and Green Star in Australia have gained prominence. According to Goosen [

3], South Africa has aligned itself with this global momentum through the adoption of the Green Star South Africa (Green Star SA) rating system, developed by the Green Building Council of South Africa (GBCSA) in 2008. This framework was designed to reflect local environmental priorities and challenges while benchmarking against international best practices [

4].

Despite the evident environmental and economic benefits associated with green buildings including operational cost savings, improved occupant health, enhanced asset value, and reduced environmental footprint [

5,

6,

7] the uptake of GBAS in South Africa remains uneven. While large-scale commercial and government buildings in urban centres are increasingly adopting green certifications, the broader construction industry still lags in widespread implementation [

4,

8]. This gap necessitates a deeper exploration of the drivers influencing the adoption of green building assessment systems in the country. Understanding these drivers is critical for promoting broader acceptance of green building practices and informing strategies to accelerate their integration into mainstream construction. Studies conducted in developed countries have identified several key drivers of GBAS adoption, including regulatory incentives, environmental awareness, client demand, corporate social responsibility, market competitiveness, and financial benefits [

9,

10]. However, the applicability of these drivers may vary in developing countries, including South Africa, due to contextual factors such as economic constraints, limited technical expertise, insufficient government incentives, and socio-political dynamics [

11,

12].

In South Africa, energy insecurity, water scarcity, and the country’s commitment to the Paris Agreement and United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide strong policy and environmental imperatives for green building adoption [

13]. Moreover, the introduction of green building guidelines in municipal policies, such as those in Johannesburg and Cape Town, has further catalyzed interest in sustainable construction. However, beyond policy, there remains limited empirical understanding of what drives stakeholders developers, contractors, consultants, and clients to adopt GBAS in practice [

14]. Recent studies by Darko, Zhang and Chan [

12] and Ametepey, Aigbavboa and Ansah [

15] stress the importance of contextualizing GBAS drivers based on local environmental, cultural, economic, and institutional realities. In South Africa, this is particularly pertinent given the country’s dual economy and housing backlog, which pose unique challenges to the adoption of sustainable building technologies. Thus, a one-size-fits-all approach to green building promotion is unlikely to succeed without a grounded understanding of context-specific motivators and constraints.

Furthermore, the role of industry awareness and education, technology availability, project financing, and the perceived complexity of GBAS processes are emerging as crucial factors in the South African context [

16]. Industry practitioners often cite lack of knowledge and upfront cost perceptions as barriers, even in cases where life-cycle benefits are demonstrably positive [

11]. These observations point to the need for targeted advocacy, capacity building, and financial mechanisms that align stakeholders’ economic and environmental objectives.

Therefore, this study seeks to assess and synthesise the key drivers influencing the adoption of GBAS in South Africa, considering the views of various stakeholders within the construction ecosystem. The goal is to provide empirical evidence that can inform policymakers, developers, and regulatory authorities about the most influential factors that drive or hinder GBAS uptake. By doing so, the study contributes to the advancement of sustainable construction practices and supports South Africa’s broader climate action goals. Ultimately, an improved understanding of these drivers can facilitate evidence-based interventions aimed at scaling up green building practices and ensuring that sustainability is no longer viewed as a luxury but as a standard in construction. This research is timely, as it aligns with both national imperatives, such as the National Development Plan 2030, and international agendas geared toward sustainable urban development.

2. Literature review

The construction industry has increasingly recognised the need for sustainable practices to mitigate its environmental footprint and promote long-term socio-economic resilience [

17,

18]. This awareness has driven the adoption of green building assessment systems (GBASs), which provide frameworks for evaluating and improving the environmental performance of buildings throughout their life cycles. They provide structured methods for assessing how effectively buildings minimize environmental impacts, enhance occupant wellbeing, and promote resource efficiency. Widely recognized international systems include LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method), and Green Star, each incorporating key indicators such as energy use, water efficiency, material selection, indoor environmental quality, and innovation [

19,

20]. In the South African context, the Green Star SA rating tool administered by the Green Building Council South Africa (GBCSA) has served as the primary mechanism for benchmarking and certifying sustainable buildings since its introduction in 2008 [

21].

GBAS have evolved in response to growing global and local demands for environmentally responsible construction practices. Their development reflects the increasing recognition that the built environment plays a critical role in addressing sustainability challenges, including climate change, resource depletion, and social wellbeing. Although these systems share a common objective of promoting sustainable construction, their scope, criteria, and application differ according to the environmental, social, and economic conditions of each region [

22]. The core components of GBAS typically revolve around comprehensive evaluation criteria that measure a building’s sustainability performance. Commonly assessed aspects include energy and water efficiency, waste management, indoor environmental quality, occupant safety, and comfort [

22,

23].

In recent years, GBAS have expanded beyond their original environmental focus to encompass social and economic dimensions, aligning with the holistic concept of sustainable development. This evolution acknowledges that the sustainability of the built environment depends not only on energy and material efficiency but also on community development, user health, and long-term economic viability. Nonetheless, Krajangsri and Pongpeng [

24] emphasized that systems developed for specific environmental contexts may not always be directly applicable elsewhere, thus underscoring the need for context-sensitive and adaptable assessment frameworks. Technological advancements have also driven innovation in GBAS methodologies. For instance, systems have begun incorporating decision-support tools such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and artificial neural networks (ANNs) to improve the objectivity and reliability of sustainability evaluations [

25,

26]. Similarly, the LEED framework exemplifies a structured and transparent approach to sustainability assessment, offering defined performance criteria and documentation requirements that guide sustainable building design, construction, and certification [

27,

28].

The adoption and implementation of GBAS are influenced by multiple factors, including environmental priorities, economic incentives, regulatory frameworks, market pressures, and social awareness [

29]. In South Africa, these drivers are particularly relevant given the nation’s pressing environmental challenges such as high greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, water scarcity, and dependence on coal-based energy systems [

30]. Understanding these contextual drivers is therefore essential to promote GBAS adoption and ensure that assessment frameworks effectively address local sustainability priorities.

While the primary focus of GBAS remains on environmental performance, there is a growing recognition of the importance of integrating broader social and economic considerations. This shift reflects a more comprehensive approach to sustainability, one that balances environmental stewardship with social equity and economic feasibility. Nevertheless, the proliferation of diverse GBAS frameworks across different regions can create uncertainty for practitioners in choosing the most appropriate system for specific projects. This underscores the need for continued research, standardization, and contextual adaptation to enhance the effectiveness and relevance of GBAS in different settings [

24].

3. Methodology

The study examined the drivers influencing the adoption of green building assessment systems within the South African construction industry, with a particular focus on Gauteng Province. A quantitative research design was employed, using a structured questionnaire to collect data from a purposive sample of construction professionals, including quantity surveyors, architects, project managers, and engineers. The quantitative approach was deemed appropriate as it allowed for the systematic measurement of respondents’ perceptions in numerical form, enabling objective ranking and rigorous statistical analysis of the identified drivers [

31]. A descriptive survey design was selected because it facilitates the assessment of prevailing conditions without manipulating variables [

32]. Gauteng was purposively chosen due to its high concentration of construction professionals and the diversity of ongoing projects in the province [

33]. From the questionnaires distributed, sixty valid responses were obtained for analysis. Although the sample size was relatively small, it aligns with prior studies employing descriptive and non-parametric statistical techniques, where samples of 30–100 respondents are considered adequate for identifying patterns and testing differences in ranked data [

34]. Data analysis techniques included Mean Item Score, Standard Deviation, Friedman Test, and One sample t-test. Reliability of the research instrument was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, which returned a value of 0.983, indicating excellent internal consistency [

35].

4. Results

According to the respondents’ background information presented in

Table 1, 46.67% hold a BSc degree, 23.33% an Honours degree, 16.67% a post-matric certificate or diploma, 3.33% an MSc degree, and 10% a PhD. In terms of professional roles, the largest group comprised Construction Managers (35%), followed by Quantity Surveyors (33.33%), Property Managers (11.67%), Construction Project Managers (10%), and Architects (5%). Regarding experience in the adoption of green building assessment systems, 51.67% reported 0–5 years, 28.33% reported 5–10 years, 16.67% reported 10–15 years, and only 3.33% had more than 15 years of experience. These findings suggest that the respondents collectively possess substantial professional expertise and strong academic qualifications, positioning them to provide informed and relevant insights that contribute meaningfully to the objectives of this study.

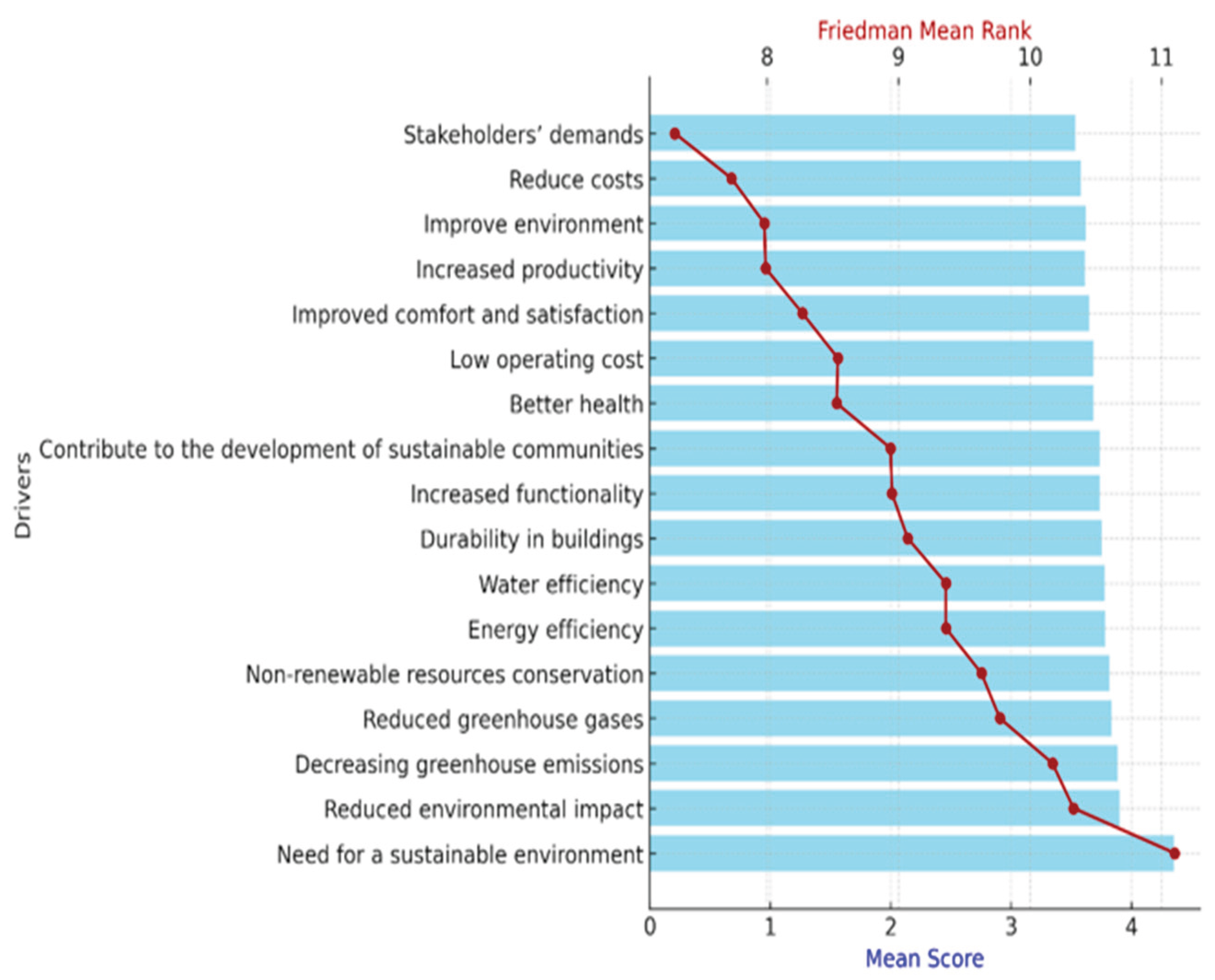

The combined results from the mean score and Friedman Test in

Table 2 reveal that “Need for a sustainable environment” emerged as the highest-rated driver influencing GBAS adoption (Mean = 4.350, SD = 0.5150; Mean Rank = 11.10). This is closely followed by “Reduced environmental impact” (Mean Rank = 10.33) and “Decreasing greenhouse emissions” (Mean Rank = 10.17), reflecting a strong emphasis on environmental preservation and climate change mitigation in the South African construction industry. In contrast, “Stakeholders’ demands” (Mean Rank = 7.30) and “Reduce costs” (Mean Rank = 7.73) ranked lowest, suggesting that market or financial pressures are less influential than sustainability imperatives in driving GBAS adoption. The Friedman Test indicated a statistically significant difference between the drivers, χ² (16, N = 60) = 148.039, p < 0.001, confirming that respondents did not rate all factors equally.

Furthermore, a one-sample t-test was conducted to examine whether the mean scores of the identified drivers influencing the adoption of Green Building Assessment Systems (GBAS) in South Africa differed significantly from the neutral test value of 3 on a five-point Likert scale. The test value of 3 represented a neutral response, while values greater than 3 indicated agreement with the respective driver as an influential factor. As presented in

Table 3, the results revealed that all the tested drivers had mean values significantly greater than 3 (p < 0.001), implying that respondents strongly perceived each factor as a positive driver of GBAS adoption in the South African construction industry. The t-values ranged from 5.22 to 20.30, confirming that the differences between the observed means and the test value were statistically significant at the 0.001 level.

The results of the one-sample t-test, as summarised in

Table 4, reveal that all identified drivers significantly influence the adoption of Green Building Assessment Systems in South Africa (p < 0.05). The “Need for a sustainable environment” (Mean = 4.35) ranked as the most influential driver, followed by “Reduced environmental impact” (Mean = 3.90) and “Decreasing greenhouse emissions” (Mean = 3.88). These findings indicate that environmental and sustainability considerations are the predominant motivators for GBAS adoption. Conversely, “Stakeholders’ demands” (Mean = 3.53) ranked lowest, suggesting that external pressures such as client or regulatory demands currently play a limited role in promoting adoption.

Figure 1 compares the mean scores, and Friedman mean ranks of the drivers influencing the adoption of Green Building Assessment Systems (GBAS) in South Africa. The results show that environmental motivations dominate over economic or stakeholder-related factors. The Need for a sustainable environment emerged as the most influential driver, achieving the highest mean score (M = 4.35) and Friedman rank (11.10), followed closely by Reduced Environmental Impact and Decreasing greenhouse emissions. In contrast, Stakeholders’ demands (M = 3.53, rank = 7.30) and Reduce costs (M = 3.58, rank = 7.73) were consistently rated as the least influential. The Friedman test confirmed statistically significant differences among the drivers (χ² (16) = 148.039, p < 0.001), suggesting a clear hierarchy of priorities. Overall, the findings indicate that sustainability imperatives (Environmental concern) are the primary motivators for GBAS adoption in the South African construction industry, particularly in Gauteng, while economic considerations are comparatively less influential.

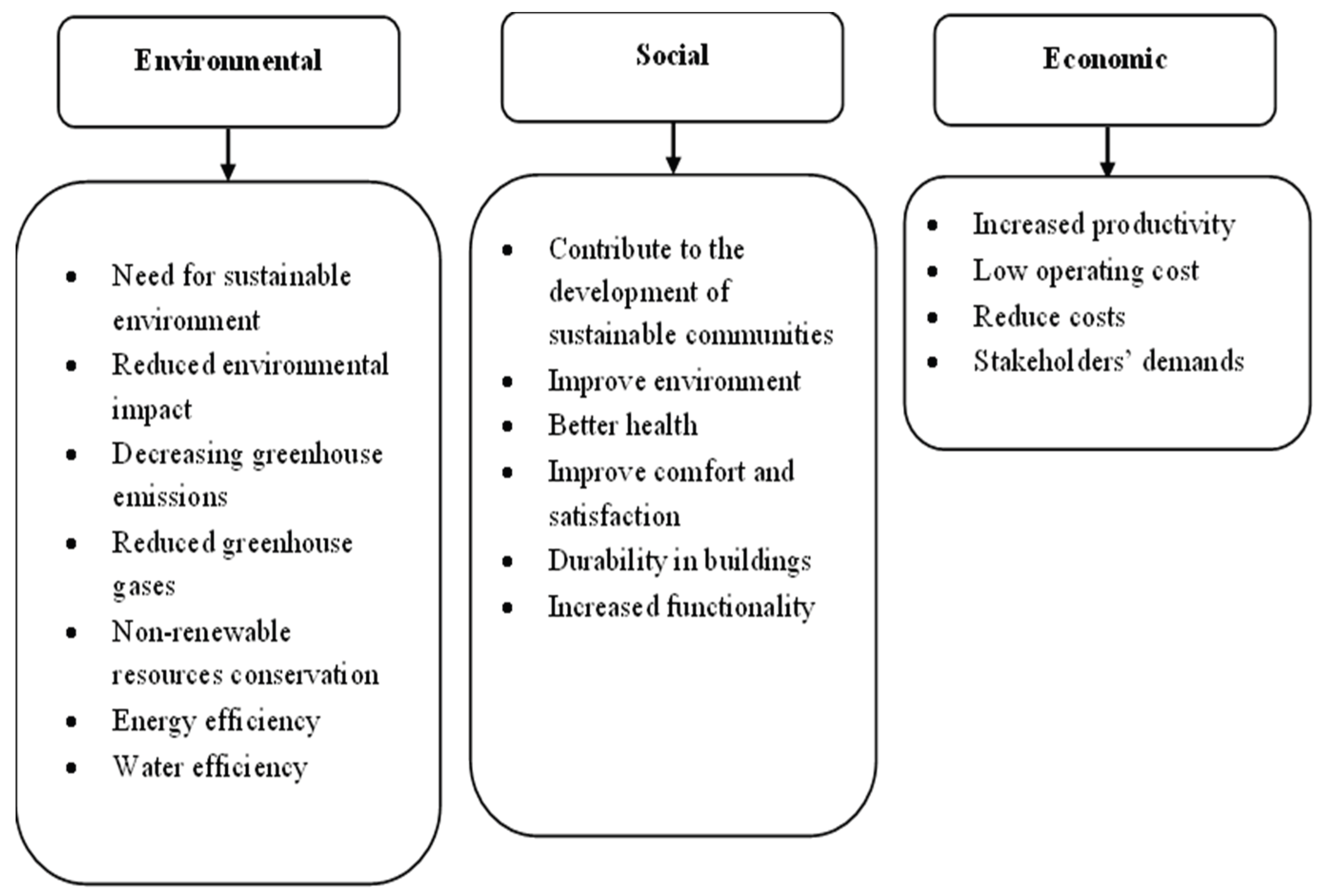

To provide a clearer thematic understanding of the identified drivers, the 17 factors were categorised into three overarching dimensions - environmental, social, and economic based on their nature and primary area of impact as shown in

Figure 2. The environmental category, which contained the largest number of drivers, included aspects such as need for a sustainable environment, reduced environmental impact, decreasing greenhouse emissions, reduced greenhouse gases, non-renewable resources conservation, energy efficiency and water efficiency. Social drivers comprised factors such as Contributes to the development of sustainable communities, improved environment, better health, and improved comfort and satisfaction, durability in buildings, and increase functionality. The economic category included drivers related to cost and productivity, such as Reduced costs, Low operating cost, and Increased productivity, and stakeholders’ demands. This classification helps to contextualise the statistical rankings presented earlier and illustrates that environmental considerations dominate GBAS adoption motivations in the South African construction sector.

5. Discussion

The findings from this study reveal that among the various drivers influencing the adoption of Green Building Assessment Systems (GBAS) in South Africa,

“Need for a sustainable environment

” emerged as the most significant driver, with the highest mean score and Friedman mean rank. This underscores the growing recognition among stakeholders of the pressing need to address environmental degradation and promote long-term ecological balance. Similar findings have been reported in prior studies, where environmental sustainability was consistently identified as a primary motivator for green building adoption [

2,

36]. The second and third ranked drivers

“Reduced environmental impact

” and

“Decreasing greenhouse emissions

” reinforce the prioritisation of environmental protection within the construction sector. These results indicate a shared industry awareness of the construction sector

’s significant carbon footprint and its role in meeting South Africa’s climate commitments under the Paris Agreement [

13]. This aligns with findings by [

9], who noted that climate change mitigation goals are strong motivators for green building adoption, especially in economies with high carbon-intensive energy systems such as South Africa’s coal-dependent grid.

Closely related is

“Reduced greenhouse gases

”, which rank fourth. This suggests that industry stakeholders differentiate between general greenhouse emissions reduction and targeted strategies for specific greenhouse gas mitigation. The emphasis on these climate-related drivers collectively indicates that environmental imperatives outweigh purely economic considerations in motivating GBAS uptake. The fifth-ranked driver,

“Non-renewable resources conservation

”, highlights the importance of resource efficiency in green building adoption. This resonates with international literature that identifies the conservation of finite resources such as fossil fuels and certain raw materials as a critical sustainability goal [

1,

15]. In South Africa, resource conservation is particularly pertinent given ongoing water scarcity challenges and energy supply instability [

37].

Furthermore, energy and water efficiency are positioned sixth and seventh in the ranking. While still considered important, their lower relative ranking suggests that they are seen as secondary outcomes of broader environmental sustainability initiatives rather than primary drivers in themselves. Previous studies, such as Hwang and Tan [

5], have observed similar patterns, where efficiency measures are valued but not necessarily perceived as the core motivation for adopting green building certifications. Durability in buildings and Increased functionality were moderately ranked, indicating that while stakeholders value long-term performance and adaptability, these are less compelling than environmental factors. The driver

“Contribute to the development of sustainable communities

” reflects a recognition of the social dimension of sustainability, consistent with the integrated triple-bottom-line approach advocated in sustainable construction literature [

10]. Interestingly, drivers related to occupant well-being, such as

“Better health

”,

“Improved comfort and satisfaction

”, and

“Increased productivity

”, were placed lower in the ranking. This suggests that while these benefits are acknowledged, they may not be strong decision-making factors for GBAS adoption in South Africa’s current market conditions. Darko, Zhang and Chan [

12] note that in emerging economies, environmental and cost-related factors tend to take precedence over user experience and productivity gains. Economic considerations such as

“Low operating cost

” and

“Reduce costs

” also ranked relatively low compared to environmental factors. This is somewhat contrary to studies in developed contexts where operational savings are often a dominant driver [

6]. In the South African context, this may indicate that cost considerations are overshadowed by the urgent need to address environmental crises, or that the industry perceives the cost benefits of GBAS as indirect and long-term rather than immediate.

Finally,

“Stakeholders’ demands

” was the least influential driver. This suggests that market pull from clients, end-users, or investors is currently weak compared to environmental and regulatory motivations. This is consistent with the observations of Madzingaidzo, van Schalkwyk and Nurick [

14] and Onososen, Osanyin and Adeyemo [

38], who argued that in South Africa, client-driven demand for certified green buildings is still emerging and requires stronger advocacy and policy reinforcement. Overall, the findings demonstrate that environmental sustainability is the dominant driver for GBAS adoption in South Africa, followed by targeted environmental impact reductions and resource conservation. Economic, social, and market-related drivers, while present, are comparatively less influential. These insights suggest that strategies to increase GBAS adoption in South Africa should leverage strong environmental motivations while simultaneously strengthening client demand, economic incentives, and awareness of social benefits.

6. Conclusions

This study assessed the key drivers influencing the adoption of Green Building Assessment Systems (GBAS) in South Africa. The results reveal that environmental imperatives are the most compelling motivators for adoption, with the need for a sustainable environment, reduced environmental impact, and decreasing greenhouse gas emissions ranking as the top three drivers. These findings underscore the growing recognition within the South African built environment sector of the urgent role buildings play in mitigating climate change and advancing sustainability goals. Conservation-oriented drivers such as the preservation of non-renewable resources, energy efficiency, and water efficiency also emerged as significant, reflecting a broader awareness of resource constraints and the necessity for responsible consumption patterns. While operational and occupant-focused benefits, such as lower operating costs, improved comfort, and increased productivity, were rated slightly lower, they remain important considerations that complement the environmental agenda. This suggests that although economic and user-experience benefits are acknowledged, the primary impetus for GBAS adoption in South Africa is rooted in environmental responsibility rather than purely financial or operational gain. The relative ranking of drivers indicates a shift in industry priorities toward a long-term sustainability vision, aligning with global green building trends. However, the comparatively lower ranking of stakeholder demands, and cost reduction implies that market and regulatory pressures may not yet be strong enough to accelerate adoption on a large scale. For GBAS uptake to expand further, supportive policy frameworks, targeted awareness campaigns, and stronger stakeholder engagement mechanisms may be required. In conclusion, this research highlights that in South Africa, the adoption of GBAS is chiefly driven by environmental stewardship, with economic and operational benefits serving as important, but secondary, incentives. The findings not only provide actionable insights for policymakers, industry practitioners, and certification bodies but also contribute to the broader discourse on sustainable construction in emerging economies. Strengthening the synergy between environmental objectives, economic incentives, and regulatory frameworks will be critical in embedding green building practices as a standard across the country’s construction sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O; and M.I.; methodology, M.O and M.I; software, M.O.; validation, M.O., C.A. and A.O.; formal analysis, M.O.; investigation, M.O. and A.O; resources, M.I; data curation, M.O.; writing—original draft preparation, M.O.; writing—review and editing, C.A and M.I.; visualization, A.O.; supervision, M.I.; project administration, C.A and A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BREEAM |

Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method |

| GBAS |

Green Building Assessment System |

| LEED |

Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design |

| AEC |

Architecture, Engineering, and Construction |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| AHP |

Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| ANN |

Artificial Neural Network |

References

- Ding, G.K.C.: Sustainable construction—The role of environmental assessment tools. Journal of Environmental Management 86, 451-464 (2008).

- Darko, A., Chan, A.P.: Review of barriers to green building adoption. Sustainable development 25, 167-179 (2017).

- Goosen, H.J.H.: Green star rating, is it pain or glory? (2012).

- Hoffman, D., Huang, L.-Y., van Rensburg, J., Yorke-Hart, A.: Trends in application of green star SA credits in South African green building. Acta Structilia 27, 1-29 (2021).

- Hwang, B.G., Tan, J.S.: Green building project management: obstacles and solutions for sustainable development. Sustainable development 20, 335-349 (2012).

- Verma, S., Mandal, S.N., Robinson, S., Bajaj, D., Saxena, A.: Investment appraisal and financial benefits of corporate green buildings: a developing economy case study. Built Environment Project and Asset Management 11, 392-408 (2021).

- Yudelson, J.: The business case for green buildings. Sustainable Investment and Places–Best Practices in Europe (88-91) (2010).

- Du Plessis, C.: A strategic framework for sustainable construction in developing countries. Construction Management and Economics 25, 67-76 (2007).

- Zhang, X., Platten, A., Shen, L.: Green property development practice in China: Costs and barriers. Building and Environment 46, 2153-2160 (2011).

- Zainul Abidin, N.: Investigating the awareness and application of sustainable construction concept by Malaysian developers. Habitat International 34, 421-426 (2010).

- Oguntona, O., Akinradewo, O., Ramorwalo, D., Aigbavboa, C., Thwala, W.: Benefits and drivers of implementing green building projects in South Africa. In: Journal of Physics: Conference Series, pp. 032038. IOP Publishing, (Year).

- Darko, A., Zhang, C., Chan, A.P.C.: Drivers for green building: A review of empirical studies. Habitat International 60, 34-49 (2017).

- UN-Habitat: World Cities Report 2020: The value of sustainable urbanization. (2020).

- Madzingaidzo, R., van Schalkwyk, L., Nurick, S.: Investigating the Drivers and Barriers to Implementing Green Building Features and Initiatives (GBFIs) in South Africa’s Private Housing Sector. In: 23 rdAnnual Conference, pp. 261. (Year).

- Ametepey, O., Aigbavboa, C., Ansah, K.: Barriers to Successful Implementation of Sustainable Construction in the Ghanaian Construction Industry. Procedia Manufacturing 3, 1682-1689 (2015).

- Windapo, A.O.: Examination of green building drivers in the South African construction industry: Economics versus ecology. Sustainability 6, 6088-6106 (2014).

- Darko, A., Chan, A.P.: Critical analysis of green building research trend in construction journals. Habitat International 57, 53-63 (2016).

- Opoku, A.: Construction industry and the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Research Companion to Construction Economics, pp. 199-214. Edward Elgar Publishing (2022).

- Ding, G.K.: Sustainable construction—The role of environmental assessment tools. Journal of environmental management 86, 451-464 (2008).

- Illankoon, I.M.C.S., Tam, V.W.Y., Le, K.N., Shen, L.: Key credit criteria among international green building rating tools. Journal of Cleaner Production 164, 209-220 (2017).

- Emere, C., Aigbavboa, C., Thwala, D.: A principal component analysis of regulatory environment features for sustainable building construction in South Africa. Journal of Construction Project Management and Innovation 13, 17-32 (2023).

- Atanda, J.O., Öztürk, A.: Social criteria of sustainable development in relation to green building assessment tools. Environment, Development & Sustainability 22, (2020).

- Sarbu, I., Sebarchievici, C.: Aspects of indoor environmental quality assessment in buildings. Energy and Buildings 60, 410-419 (2013).

- Krajangsri, T., Pongpeng, J.: A comparison of green building assessment systems. In: MATEC Web of Conferences, pp. 02027. EDP Sciences, (Year).

- Kaklauskas, A., Dzemyda, G., Tupenaite, L., Voitau, I., Kurasova, O., Naimaviciene, J., Rassokha, Y., Kanapeckiene, L.: Artificial Neural Network-Based Decision Support System for Development of an Energy-Efficient Built Environment. Energies 11, 1994 (2018).

- Saboor, S., Ahmed, V., Anane, C., Bahroun, Z.: A Hybrid AHP–Fuzzy MOORA Decision Support Tool for Advancing Social Sustainability in the Construction Sector. Sustainability 17, 4879 (2025).

- Di Gaetano, F., Cascone, S., Caponetto, R.: Integrating BIM Processes with LEED Certification: A Comprehensive Framework for Sustainable Building Design. Buildings 13, 2642 (2023).

- Hallas, N.E.: LEED certification and sustainable building practices: a comprehensive guide to efficient and sustainable facilities. Design Strategies for Efficient and Sustainable Building Facilities, pp. 124-161. IGI Global (2024).

- Darko, A., Chan, A.P.C., Owusu-Manu, D.-G., Gou, Z., Man, J.C.-F.: Adoption of Green Building Technologies in Ghana. In: Gou, Z. (ed.) Green Building in Developing Countries: Policy, Strategy and Technology, pp. 217-235. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2020).

- Smarte Anekwe, I.M., Akpasi, S.O., Mkhize, M.M., Zhou, H., Moyo, R.T., Gaza, L.: Renewable energy investments in South Africa: Potentials and challenges for a sustainable transition - a review. Science Progress 107, 00368504241237347 (2024).

- Creswell, J.W., Clark, V.L.P.: Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage (2017).

- Babbie, E.R.: The practice of social research. Cengage Au (2020).

- Ikuabe, M., Aigbavboa, C., Ngcobo, N., Stephen, S.: Towards a Hybrid Project Management for Construction Delivery. In: The Fourteenth International Conference on Construction in the 21st Century (CITC-14). (2024).

- Saunders, M.N., Lewis, P., Thornhill, A., Bristow, A.: Research Methods for Business Students (8th ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited (2019).

- Tavakol, M., Dennick, R.: Making sense of Cronbach’s Alpha. International Journal of Medical Education 2, (2011).

- Oke, A., Aghimien, D., Aigbavboa, C., Musenga, C.: Drivers of Sustainable Construction Practices in the Zambian Construction Industry. Energy Procedia 158, 3246-3252 (2019).

- Mohamed, N.: Sustainability Transitions in South Africa. Routledge Abingdon and New York (2019).

- Onososen, A.O., Osanyin, O., Adeyemo, M.: Drivers and barriers to the implementation of green building development. PM World Journal 8, 1-15 (2019).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).