Submitted:

28 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods

2.1. Research Design and Approach

2.2. Population and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Method of Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Respondents’ Demographic Information

3.2. One-Sample Test of the Challenges Affecting the Adoption and Implementation of SCPs.

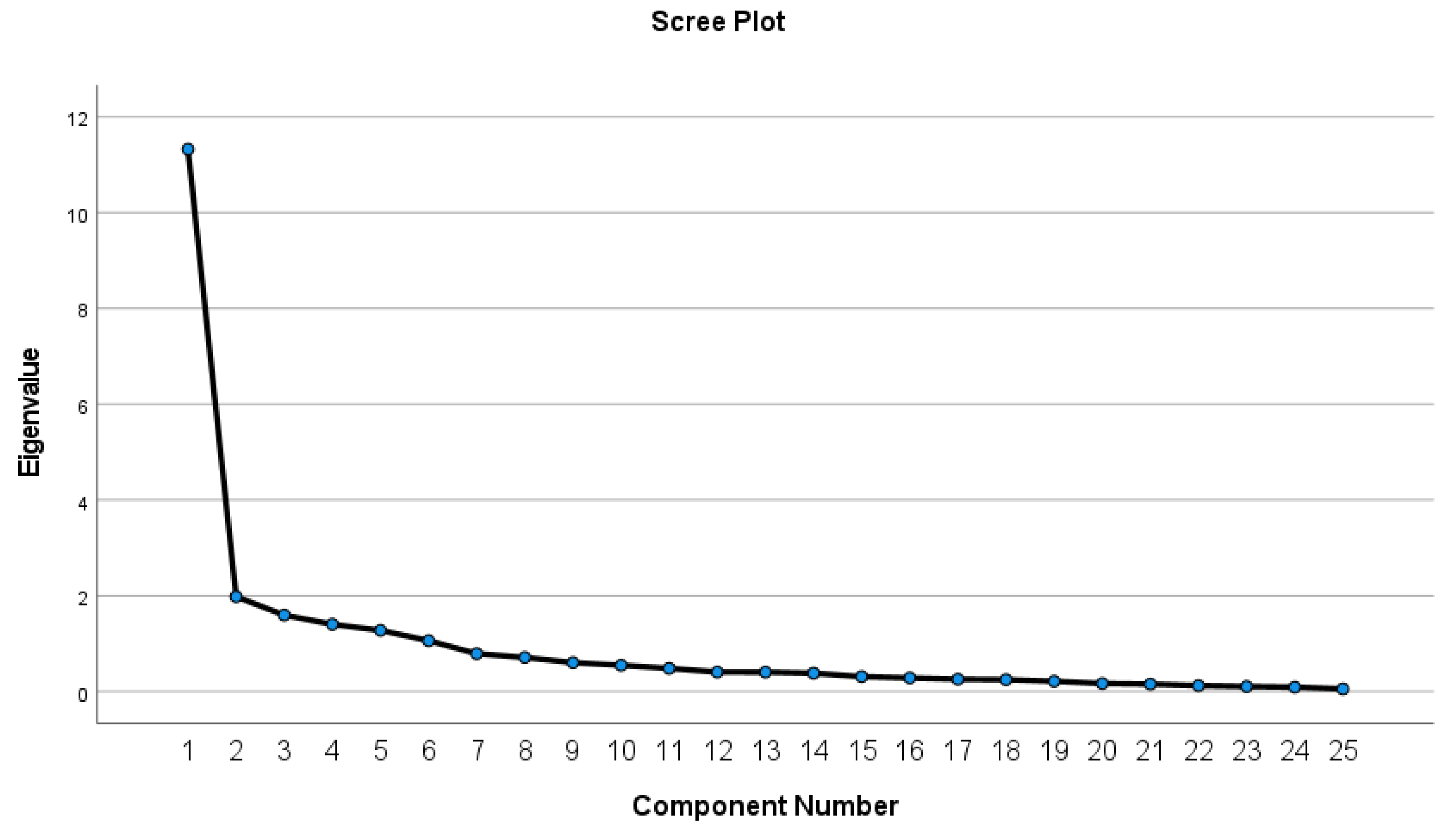

3.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis of the Challenges Affecting the Adoption and Implementation of SCPs.

Component I: Institutional Limitations

Component 2: Inadequate Technical Experience

Component 3: Inadequate Knowledge and Information

Component 4: Operational

Component 5: Financial

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. J. Epstein, Making sustainability work: Best practices in managing and measuring corporate social, environmental and economic impacts. Routledge, 2018.

- C. Ainger and R. Fenner, Sustainable infrastructure: principles into practice. ICE publishing, 2014.

- L. Loizou, K. Barati, X. Shen, and B. Li, “Quantifying advantages of modular construction: Waste generation,” Buildings, vol. 11, no. 12, p. 622, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Ganda and C. C. Ngwakwe, “Role of energy efficiency on sustainable development,” Environmental Economics, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 86–99, 2014.

- C. S. Goh, J. N. Ting, and A. Bajracharya, “Exploring social sustainability in the built environment,” Advances in Environmental and Engineering Research, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1–15, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Willbroad Sihela and D. Nkengbeza, “Factors Affecting Project Success at Katima Mulilo Town Council in the Zambezi Region of Namibia: A Study of the Build Together Project,” Global Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 1–30, 2021.

- L. B. Cole, G. Lindsay, and A. Akturk, “Green building education in the green museum: design strategies in eight case study museums,” International Journal of Science Education, Part B, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 149–165, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang et al., “A survey of the status and challenges of green building development in various countries,” Sustainability, vol. 11, no. 19, p. 5385, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Hershey, M. Kalina, I. Kafodya, and E. Tilley, “A sustainable alternative to traditional building materials: assessing stabilised soil blocks for performance and cost in Malawi,” International Journal of Sustainable Engineering, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 155–165, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. O. Aghimien, C. O. Aigbavboa, and W. D. Thwala, “Microscoping the challenges of sustainable construction in developing countries,” Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 1110–1128, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Khan, S. M. Wabaidur, M. R. Siddiqui, A. A. Alqadami, and A. H. Khan, “Silico-manganese fumes waste encapsulated cryogenic alginate beads for aqueous environment de-colorization,” J Clean Prod, vol. 244, p. 118867, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. AlSanad, “Awareness, drivers, actions, and barriers of sustainable construction in Kuwait,” Procedia Eng, vol. 118, pp. 969–983, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Djokoto, J. Dadzie, and E. Ohemeng-Ababio, “Barriers to sustainable construction in the Ghanaian construction industry: consultants perspectives,” J Sustain Dev, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 134, 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Pham and S.-Y. Kim, “The effects of sustainable practices and managers’ leadership competences on sustainability performance of construction firms,” Sustain Prod Consum, vol. 20, pp. 1–14, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Iqbal, J. Ma, N. Ahmad, K. Hussain, M. S. Usmani, and M. Ahmad, “Sustainable construction through energy management practices in developing economies: an analysis of barriers in the construction sector,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 28, pp. 34793–34823, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Tokbolat, F. Karaca, S. Durdyev, and R. K. Calay, “Construction professionals’ perspectives on drivers and barriers of sustainable construction,” Environ Dev Sustain, vol. 22, pp. 4361–4378, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Dwaikat, K. A.-E. and Buildings, and undefined 2016, “Green buildings cost premium: A review of empirical evidence,” Elsevier, vol. 110, pp. 396–403, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Darko, C. Zhang, and A. P. C. Chan, “Drivers for green building: A review of empirical studies,” Habitat Int, vol. 60, pp. 34–49, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Ayarkwa, D.-G. J. Opoku, P. Antwi-Afari, and R. Y. M. Li, “Sustainable building processes’ challenges and strategies: The relative important index approach,” Clean Eng Technol, vol. 7, p. 100455, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Davies, M. Dodgson, and D. Gann, “Dynamic Capabilities in Complex Projects: The Case of London Heathrow Terminal 5,” Project Management Journal, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 26–46, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. D. J. Mwamvani, C. Amoah, and E. Ayesu-Koranteng, “Causes of road projects’ delays: a case of Blantyre, Malawi,” Built Environment Project and Asset Management, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 293–308, 2022.

- M. Singh and E. Schoenmakers, “Comparative Impact Analysis of Cyclone Ana in the Mozambique Channel Using Satellite Data,” Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 7, p. 4519, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Martín-Martín, M. Thelwall, E. Orduna-Malea, and E. Delgado López-Cózar, “Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic, Scopus, Dimensions, Web of Science, and OpenCitations’ COCI: a multidisciplinary comparison of coverage via citations,” Scientometrics, vol. 126, no. 1, pp. 871–906, 2021.

- X. Zhao, B.-G. Hwang, and J. Lim, “Job satisfaction of project managers in green construction projects: Constituents, barriers, and improvement strategies,” J Clean Prod, vol. 246, p. 118968, 2020.

- N. Wang, S. Yao, G. Wu, and X. Chen, “The role of project management in organisational sustainable growth of technology-based firms,” Technol Soc, vol. 51, pp. 124–132, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Franco, P. Pawar, X. W.-E. and buildings, and undefined 2021, “Green building policies in cities: A comparative assessment and analysis,” Elsevier, Accessed: Nov. 22, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378778820323690.

- L. B. Robichaud and V. S. Anantatmula, “Greening project management practices for sustainable construction,” Journal of management in engineering, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 48–57, 2011. [CrossRef]

- B.-G. Hwang and W. J. Ng, “Project management knowledge and skills for green construction: Overcoming challenges,” International journal of project management, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 272–284, 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Barbosa, … M. S.-I. J. of, and undefined 2021, “Configurations of project management practices to enhance the performance of open innovation R&D projects,” Elsevier, Accessed: Nov. 22, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0263786320300454.

- A. J. G. Silvius and M. de Graaf, “Exploring the project manager’s intention to address sustainability in the project board,” J Clean Prod, vol. 208, pp. 1226–1240, 2019.

- A. P. C. Chan, A. Darko, and E. E. Ameyaw, “Strategies for promoting green building technologies adoption in the construction industry—An international study,” Sustainability, vol. 9, no. 6, p. 969, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Opoku, J. Deng, A. Elmualim, S. Ekung, A. A. Hussien, and S. B. Abdalla, “Sustainable procurement in construction and the realisation of the sustainable development goal (SDG) 12,” J Clean Prod, vol. 376, p. 134294, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Kibert, Sustainable construction: green building design and delivery. John Wiley & Sons, 2016.

- J.-P. Schöggl, R. J. Baumgartner, and D. Hofer, “Improving sustainability performance in early phases of product design: A checklist for sustainable product development tested in the automotive industry,” J Clean Prod, vol. 140, pp. 1602–1617, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. S. J. Koolwijk, C. J. van Oel, J. W. F. Wamelink, and R. Vrijhoef, “Collaboration and integration in project-based supply chains in the construction industry,” Journal of Management in Engineering, vol. 34, no. 3, p. 04018001, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Häkkinen and K. Belloni, “Barriers and drivers for sustainable building,” Building Research & Information, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 239–255, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. J.-T. Zidane and B. Andersen, “The top 10 universal delay factors in construction projects,” International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 650–672, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Alshawi and I. Faraj, “Integrated construction environments: technology and implementation,” Construction Innovation, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 33–51, 2002.

- S. Argyroudis, S. Mitoulis, E. Chatzi, … J. B.-C. R., and undefined 2022, “Digital technologies can enhance climate resilience of critical infrastructure,” Elsevier, Accessed: Nov. 22, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212096321001169.

- M. R. Delos Reyes, M. A. M. Gamboa, and R. R. B. Rivera, “The Philippines’ National Urban Policy for achieving sustainable, resilient, greener and smarter cities,” Developing National Urban Policies: Ways Forward to Green and Smart Cities, pp. 169–203, 2020.

- O. Akinradewo, C. Aigbavboa, D. Aghimien, A. Oke, and B. Ogunbayo, “Modular method of construction in developing countries: the underlying challenges,” International Journal of Construction Management, vol. 23, no. 8, pp. 1344–1354, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B.-G. Hwang, L. Zhu, and J. S. H. Tan, “Green business park project management: Barriers and solutions for sustainable development,” J Clean Prod, vol. 153, pp. 209–219, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Ahmed and S. El-Sayegh, “The challenges of sustainable construction projects delivery–evidence from the UAE,” Architectural Engineering and Design Management, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 299–312, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Suprapto, H. L. M. Bakker, H. G. Mooi, and M. J. C. M. Hertogh, “How do contract types and incentives matter to project performance?,” International journal of project management, vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 1071–1087, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kang, C. Kim, H. Son, S. Lee, and C. Limsawasd, “Comparison of preproject planning for green and conventional buildings,” J Constr Eng Manag, vol. 139, no. 11, p. 04013018, 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. M. El-Sayegh, S. Manjikian, A. Ibrahim, A. Abouelyousr, and R. Jabbour, “Risk identification and assessment in sustainable construction projects in the UAE,” Taylor & FrancisSM El-Sayegh, S Manjikian, A Ibrahim, A Abouelyousr, R JabbourInternational Journal of Construction Management, 2021•Taylor & Francis, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 327–336, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Al-Hajj and K. Hamani, “Material waste in the UAE construction industry: Main causes and minimization practices,” Architectural engineering and design management, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 221–235, 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. A. E. Othman, N. A.- Organization, & technology, and undefined 2021, “A framework for achieving sustainability by overcoming the challenges of the construction supply chain during the design process,” hrcak.srce.hrA Ahmed Ezzat Othman, N AlNassarOrganization, technology & management in construction: an international, 2021•hrcak.srce.hr, vol. 13, pp. 2391–2415, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Tafazzoli, E. Mousavi, and S. Kermanshachi, “Opportunities and challenges of green-lean: An integrated system for sustainable construction,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 11, p. 4460, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Bohari, M. Skitmore, B. Xia, M. T.-J. of cleaner production, and undefined 2017, “Green oriented procurement for building projects: Preliminary findings from Malaysia,” Elsevier, vol. 148, pp. 690–700, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. O. Olawumi and D. W. M. Chan, “Key drivers for smart and sustainable practices in the built environment,” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 1257–1281, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Singh and M. B. Masuku, “Sampling techniques & determination of sample size in applied statistics research: An overview,” International Journal of economics, commerce and management, vol. 2, no. 11, pp. 1–22, 2014.

- Z. Liu, Y. Lu, T. Nath, Q. Wang, R. L. K. Tiong, and L. L. C. Peh, “Critical success factors for BIM adoption during construction phase: A Singapore case study,” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, vol. 29, no. 9, pp. 3267–3287, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Lekan, A. Clinton, E. Stella, E. Moses, and O. Biodun, “Construction 4.0 application: Industry 4.0, internet of things and lean construction tools’ application in quality management system of residential building projects,” Buildings, vol. 12, no. 10, p. 1557, 2022.

- A. S. Beavers, J. W. Lounsbury, J. K. Richards, S. W. Huck, G. J. Skolits, and S. L. Esquivel, “Practical considerations for using exploratory factor analysis in educational research,” Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 6, 2019.

- O. A. Ogunsanya, C. O. Aigbavboa, D. W. Thwala, and D. J. Edwards, “Barriers to sustainable procurement in the Nigerian construction industry: an exploratory factor analysis,” International Journal of Construction Management, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 861–872, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Darko, A. P. C. Chan, Y. Yang, M. Shan, B.-J. He, and Z. Gou, “Influences of barriers, drivers, and promotion strategies on green building technologies adoption in developing countries: The Ghanaian case,” J Clean Prod, vol. 200, pp. 687–703, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. W. Watkins, “Exploratory factor analysis: A guide to best practice,” Journal of black psychology, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 219–246, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Nasiru and N. H. Md Dahlan, “Exploratory factor analysis in establishing dimensions of intervention programmes among obstetric vesicovaginal fistula victims in Northern Nigeria,” Journal of Critical Reviews, vol. 7, no. 8, pp. 1554–1560, 2020.

- L. Sürücü and A. Maslakci, “Validity and reliability in quantitative research,” Business & Management Studies: An International Journal, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 2694–2726, 2020.

- K. S. Taber, “The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education,” Res Sci Educ, vol. 48, pp. 1273–1296, 2018.

- O. I. Olanrewaju and V. N. Okorie, “Exploring the Qualities of a Good Leader Using Principal Component Analysis.,” Journal of Engineering, Project & Production Management, vol. 9, no. 2, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. O. Toyin and M. C. Mewomo, “An investigation of barriers to the application of building information modelling in Nigeria,” Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 442–468, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. U. Okoye, K. C. Okolie, and I. A. Odesola, “Risks of implementing sustainable construction practices in the Nigerian building industry,” Construction Economics and Building, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 21–46, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Jaffar, N. I. N. Affendi, I. Mohammad Ali, N. Ishak, and A. S. Jaafar, “Barriers of green building technology adoption in Malaysia: contractors’ perspective,” International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, vol. 12, no. 8, pp. 1552–1560, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Fathalizadeh, M. R. Hosseini, S. S. Vaezzadeh, D. J. Edwards, I. Martek, and S. Shooshtarian, “Barriers to sustainable construction project management: the case of Iran,” Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 717–739, 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Ngoma, I. Kafodya, P. Kloukinas, V. Novelli, J. Macdonald, and K. Goda, “Building classification and seismic vulnerability of current housing construction in Malawi,” Malawi Journal of Science and Technology, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 57–72, 2019.

- E. O’Dwyer, I. Pan, S. Acha, and N. Shah, “Smart energy systems for sustainable smart cities: Current developments, trends and future directions,” Appl Energy, vol. 237, pp. 581–597, 2019.

- M. Gunduz and E. A. Abdi, “Motivational factors and challenges of cooperative partnerships between contractors in the construction industry,” Journal of Management in Engineering, vol. 36, no. 4, p. 04020018, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Tavakol and A. Wetzel, “Factor Analysis: a means for theory and instrument development in support of construct validity,” Int J Med Educ, vol. 11, p. 245, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Hatcher and N. O’Rourke, A step-by-step approach to using SAS for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Sas Institute, 2013.

- D. Willar, E. V. Y. Waney, D. D. G. Pangemanan, and R. E. G. Mait, “Sustainable construction practices in the execution of infrastructure projects: The extent of implementation,” Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 106–124, 2021.

- M. A. Adabre, A. P. C. Chan, and A. Darko, “Interactive effects of institutional, economic, social and environmental barriers on sustainable housing in a developing country,” Build Environ, vol. 207, p. 108487, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Oke, A. O. Oyediran, G. Koriko, and L. M. Tang, “Carbon trading practices adoption for sustainable construction: A study of the barriers in a developing country,” Sustainable Development, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 1120–1136, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Mendoza-del Villar, E. Oliva-Lopez, O. Luis-Pineda, A. Benešová, J. Tupa, and J. A. Garza-Reyes, “Fostering economic growth, social inclusion & sustainability in Industry 4.0: a systemic approach,” Procedia Manuf, vol. 51, pp. 1755–1762, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Ikudayisi, A. P. C. Chan, A. Darko, and O. B. Adegun, “Integrated design process of green building projects: a review towards assessment metrics and conceptual framework,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 50, p. 104180, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Agyekum, F. D. K. Fugar, K. Agyekum, I. Akomea-Frimpong, and H. Pittri, “Barriers to stakeholder engagement in sustainable procurement of public works,” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 3840–3857, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Marchi, E. Antonini, and S. Politi, “Green building rating systems (GBRSs),” Encyclopedia, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 998–1009, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Akbari, M. Sheikhkhoshkar, F. P. Rahimian, H. B. El Haouzi, M. Najafi, and S. Talebi, “Sustainability and building information modelling: Integration, research gaps, and future directions,” Autom Constr, vol. 163, p. 105420, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Martínez-Peláez et al., “Role of digital transformation for achieving sustainability: mediated role of stakeholders, key capabilities, and technology,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 14, p. 11221, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Malik, P. B. K. Mbewe, N. Kavishe, T. Mkandawire, and P. Adetoro, “Sustainable Construction Practices in Building Infrastructure Projects: The Extent of Implementation and Drivers in Malawi,” Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 24, p. 10825, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, L. Jiang, M. Osmani, and P. Demian, “Building information management (BIM) and blockchain (BC) for sustainable building design information management framework,” Electronics (Basel), vol. 8, no. 7, p. 724, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. T. Quang and D. P. Thao, “Analyzing the green financing and energy efficiency relationship in ASEAN,” The Journal of Risk Finance, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 385–402, 2022. [CrossRef]

| Code | Critical challenges | Reference |

| CH 1 | Higher costs of sustainable building materials | [18,25] |

| CH 2 | The technicalities of the construction process | [26,27] |

| CH 3 | Lengthy bureaucratic procedures of sustainable building processes | [28] |

| CH 4 | lack of knowledge about sustainable technology | [29,30,31] |

| CH 5 | Lack of awareness of sustainable practices | [19,32,33] |

| CH 6 | lack of information on sustainable building products | [34,35,36] |

| CH 7 | Lack of stakeholder Collaboration | [37,38] |

| CH 8 | Lack of Long-Term Performance Monitoring and Maintenance | [39] |

| CH 9 | Poor communication between stakeholders | [20] |

| CH 10 | Higher costs of sustainable building processes. | [17] |

| CH 11 | Inadequate project planning and coordination | [21,40] |

| CH 12 | Inability the inability of stakeholders to let go of traditional construction and project management practices | [41] |

| CH 13 | Poor feasibility and management of risk | [42] |

| CH 14 | Lack of sustainability building codes and policies | [36] |

| CH 15 | Limited experience in selecting sustainable construction procedures and techniques | [43] |

| CH 16 | Absence of sustainability criteria in the bidding process | [43] |

| CH 17 | Inadequate funding for sustainable projects | [43] |

| CH 18 | Lack of incentives for contractors who incorporate sustainability practices in the project delivery | [44] |

| CH 19 | Inability the inability of contractors to budget sustainable projects | [27] |

| CH 20 | Poor scope definition of sustainable construction requirements | [45] |

| CH 21 | Incomplete sustainability specifications for projects | [46,47] |

| CH 22 | Difficulty in complying with sustainable building codes and certifications | [46,48] |

| CH 23 | Clients’ unwillingness to pay extra for green buildings | [13,49] |

| CH 24 | Fragmented guidelines for sustainable procurement procedure | [50] |

| CH 25 | Need for special materials for sustainable projects | [51] |

| Demographics of respondents | Responses per demographic (n=193) | Frequency (%) |

| Highest Qualification | ||

| Secondary/Senior High | 8 | 4 |

| Diploma | 46 | 24 |

| Degree | 105 | 54 |

| Master's Degree | 27 | 14 |

| PhD | 7 | 4 |

| Job Description | ||

| Architect | 46 | 24 |

| Project Manager | 43 | 22 |

| Civil Engineer | 38 | 20 |

| Quantity Surveyors | 32 | 17 |

| Specialist Engineer | 18 | 9 |

| Builder | 9 | 5 |

| Procurement officer | 7 | 3 |

| Work Experience | ||

| 1-5 years | 74 | 38 |

| 6-10 years | 68 | 35 |

| 11-15 years | 42 | 22 |

| 16-20 years | 7 | 4 |

| 21 years and above | 2 | 1 |

| Kind of Firm | ||

| Construction Company | 79 | 41 |

| Consultant | 55 | 28 |

| Real Estate Company | 31 | 16 |

| Government Agency | 28 | 15 |

| Test Value (µ = 3.5) | |||||||||

| Code | Challenges | MS | SD | t-value | Df | Sig. (2-tailed) | MD | R | Significant (P<0.05) |

| CH1 | Higher costs of sustainable building processes. | 3.84 | 0.750 | 6.286 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.339 | 1 | Yes |

| CH2 | Lack of information on sustainable building products | 3.83 | 0.762 | 6.002 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.329 | 2 | Yes |

| CH3 | Higher costs of sustainable building materials | 3.83 | 0.795 | 5.749 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.329 | 3 | Yes |

| CH4 | Lack of knowledge about sustainable technology | 3.82 | 0.722 | 6.233 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.324 | 4 | Yes |

| CH5 | Inability of stakeholders to let go of traditional construction and project management practices | 3.82 | 0.844 | 5.247 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.319 | 5 | Yes |

| CH6 | Need for special materials for sustainable projects | 3.81 | 0.721 | 5.937 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.308 | 6 | Yes |

| CH7 | Lack of awareness of sustainable practices | 3.81 | 0.814 | 5.349 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.313 | 7 | Yes |

| CH8 | Limited experience in selecting sustainable construction procedures and techniques | 3.80 | 0.752 | 5.601 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.303 | 8 | Yes |

| CH9 | Clients unwillingness to pay extra for green buildings | 3.79 | 0.763 | 5.332 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.293 | 9 | Yes |

| CH10 | Lengthy bureaucratic procedures of sustainable building processes | 3.77 | 0.750 | 5.039 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.272 | 10 | Yes |

| CH11 | Inadequate project planning and coordination | 3.77 | 0.765 | 4.843 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.267 | 11 | Yes |

| CH12 | Fragmented guidelines for the sustainable procurement procedure | 3.76 | 0.713 | 4.999 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.256 | 12 | Yes |

| CH13 | Lack of Stakeholder Collaboration | 3.76 | 0.718 | 5.061 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.262 | 13 | Yes |

| CH14 | Lack of Long-Term Performance Monitoring and Maintenance | 3.76 | 0.762 | 4.674 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.256 | 14 | Yes |

| CH15 | Inadequate Funding for sustainable projects | 3.76 | 0.675 | 5.276 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.256 | 15 | Yes |

| CH16 | Lack of sustainable building codes and policies | 3.76 | 0.828 | 4.305 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.256 | 16 | Yes |

| CH17 | Difficulty in complying with sustainable building codes and certifications | 3.74 | 0.733 | 4.569 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.241 | 17 | Yes |

| CH18 | The technicalities of the construction process | 3.74 | 0.826 | 4.051 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.241 | 18 | Yes |

| CH19 | Poor feasibility and management of risk | 3.73 | 0.797 | 4.019 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.231 | 19 |

Yes |

| CH20 | Absence of sustainability criteria in the bidding process | 3.72 | 0.739 | 4.139 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.220 | 20 | Yes |

| CH21 | Lack of incentives for contractors who incorporate sustainability practices in the project delivery | 3.72 | 0.753 | 4.062 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.220 | 21 | Yes |

| CH22 | Incomplete sustainability specifications for projects | 3.66 | 0.755 | 2.908 | 192 | 0.004 | 0.158 | 22 | Yes |

| CH23 | Poor Communication between stakeholders | 3.66 | 0.808 | 2.716 | 192 | 0.007 | 0.158 | 23 | Yes |

| CH24 | Inability of contractors to budget Sustainable projects | 3.63 | 0.826 | 2.223 | 192 | 0.027 | 0.132 | 24 | Yes |

| CH25 | Poor scope definition of sustainable construction requirements | 3.62 | 0.782 | 2.163 | 192 | 0.032 | 0.122 | 25 | Yes |

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. | 0.915 | |

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 3121.711 |

| Df | 300 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

| Cronbach's Alpha | 0.949 | |

| Code | Factors | Initial | Extraction |

| CH1 | Higher costs of sustainable building processes. | 1.000 | 0.552 |

| CH2 | Lack of information on sustainable building products | 1.000 | 0.817 |

| CH3 | Higher costs of sustainable building materials | 1.000 | 0.806 |

| CH4 | Lack of knowledge about sustainable technology | 1.000 | 0.771 |

| CH5 | Inability of stakeholders to let go of traditional construction and project management practices | 1.000 | 0.631 |

| CH6 | Need for special materials for sustainable projects | 1.000 | 0.643 |

| CH7 | Lack of awareness of sustainable practices | 1.000 | 0.802 |

| CH8 | Limited experience in selecting sustainable construction procedures and techniques | 1.000 | 0.629 |

| CH9 | Clients unwillingness to pay extra for green buildings | 1.000 | 0.600 |

| CH10 | Lengthy bureaucratic procedures of sustainable building processes | 1.000 | 0.490 |

| CH11 | Inadequate project planning and coordination | 1.000 | 0.647 |

| CH12 | Fragmented guidelines for the sustainable procurement procedure | 1.000 | 0.662 |

| CH13 | Lack of Stakeholder Collaboration | 1.000 | 0.687 |

| CH14 | Lack of Long-Term Performance Monitoring and Maintenance | 1.000 | 0.618 |

| CH15 | Inadequate Funding for sustainable projects | 1.000 | 0.621 |

| CH16 | Lack of sustainable building codes and policies | 1.000 | 0.743 |

| CH17 | Difficulty in complying with sustainable building codes and certifications | 1.000 | 0.666 |

| CH18 | The technicalities of the construction process | 1.000 | 0.742 |

| CH19 | Poor feasibility and management of risk | 1.000 | 0.665 |

| CH20 | Absence of sustainability criteria in the bidding process | 1.000 | 0.572 |

| CH21 | Lack of incentives for contractors who incorporate sustainability practices in the project delivery | 1.000 | 0.694 |

| CH22 | Incomplete sustainability specifications for projects | 1.000 | 0.704 |

| CH23 | Poor Communication between stakeholders | 1.000 | 0.585 |

| CH24 | Inability of contractors to budget Sustainable projects | 1.000 | 0.702 |

| CH25 | Poor scope definition of sustainable construction requirements | 1.000 | 0.767 |

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. | |||

| Component | % of Variance | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Institutional Limitations | 45.807 | ||||||

| CH16 | Lack of sustainable building codes and policies | 0.759 | |||||

| CH19 | Poor feasibility and management of risk | 0.703 | |||||

| CH5 | Inability of stakeholders to let go of traditional construction and project management practices | 0.684 | |||||

| CH6 | Need for special materials for sustainable projects | 0.546 | |||||

| CH11 | Inadequate project planning and coordination | 0.535 | |||||

| CH12 | Fragmented guidelines for the sustainable procurement procedure | 0.501 | |||||

| CH20 | Absence of sustainability criteria in the bidding process | 0.472 | |||||

| Inadequate Technical Experience | 6.575 | ||||||

| CH25 | Poor scope definition of sustainable construction requirements | 0.804 | |||||

| CH24 | Inability of contractors to budget Sustainable projects | 0.764 | |||||

| CH22 | Incomplete sustainability specifications for projects | 0.691 | |||||

| CH17 | Difficulty in complying with sustainable building codes and certifications | 0.658 | |||||

| CH8 | Limited experience in selecting sustainable construction procedures and techniques | 0.648 | |||||

| CH18 | The technicalities of the construction process | 0.563 | |||||

| Inadequate Knowledge and information | 5.675 | ||||||

| CH7 | Lack of awareness of sustainable practices | 0.807 | |||||

| CH4 | Lack of knowledge about sustainable technology | 0.772 | |||||

| CH2 | Lack of information on sustainable building products | 0.771 | |||||

| Operational | 4.705 | ||||||

| CH14 | Lack of Long-Term Performance Monitoring and Maintenance | 0.673 | |||||

| CH13 | Lack of Stakeholder Collaboration | 0.665 | |||||

| CH10 | Lengthy bureaucratic procedures of sustainable building processes | 0.639 | |||||

| CH23 | Poor Communication between stakeholders | 0.580 | |||||

| Financial | 4.503 | ||||||

| CH9 | Clients’ unwillingness to pay extra for green buildings | 0.852 | |||||

| CH1 | Higher costs of sustainable building processes. | 0.841 | |||||

| CH3 | Higher costs of sustainable building materials | 0.776 | |||||

| CH15 | Inadequate Funding for sustainable projects | 0.582 | |||||

| CH21 | Lack of incentives for contractors who incorporate sustainability practices in the project delivery | 0.522 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).