Submitted:

04 November 2025

Posted:

05 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods of the Current Study

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Selection Process

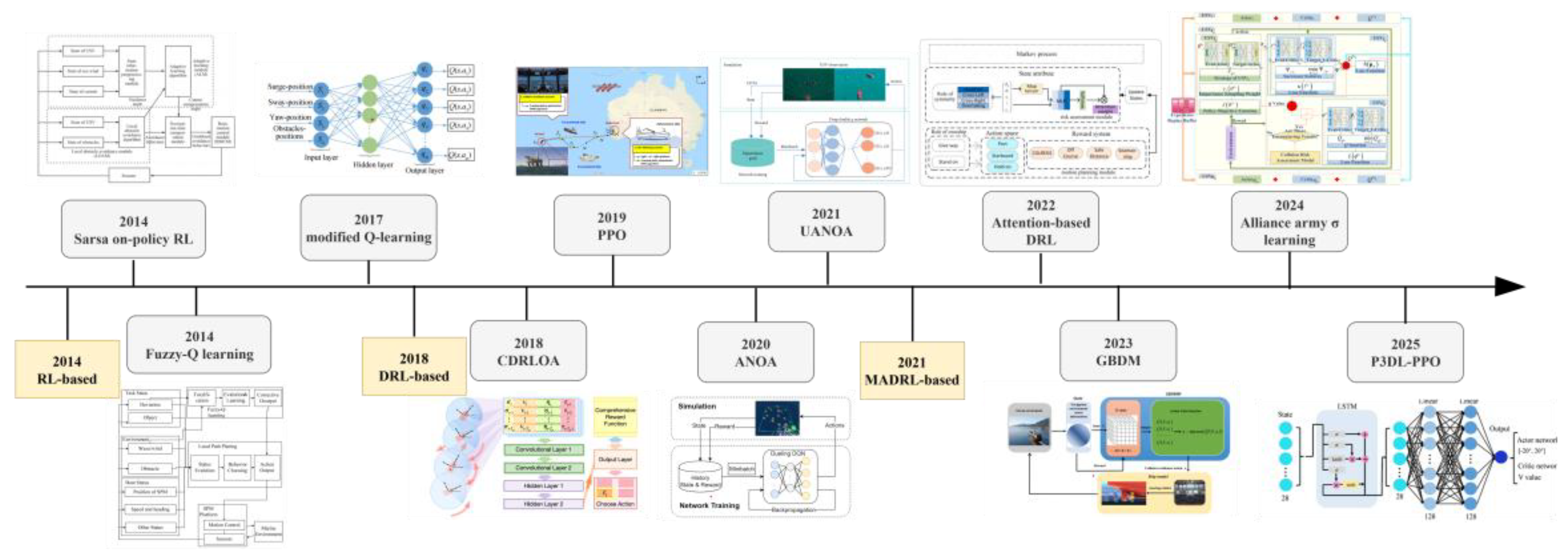

3. Single-Agent Collision Avoidance

3.1. Collision Avoidance in Static Environment

3.2. Collision Avoidance in Dynamic Environment

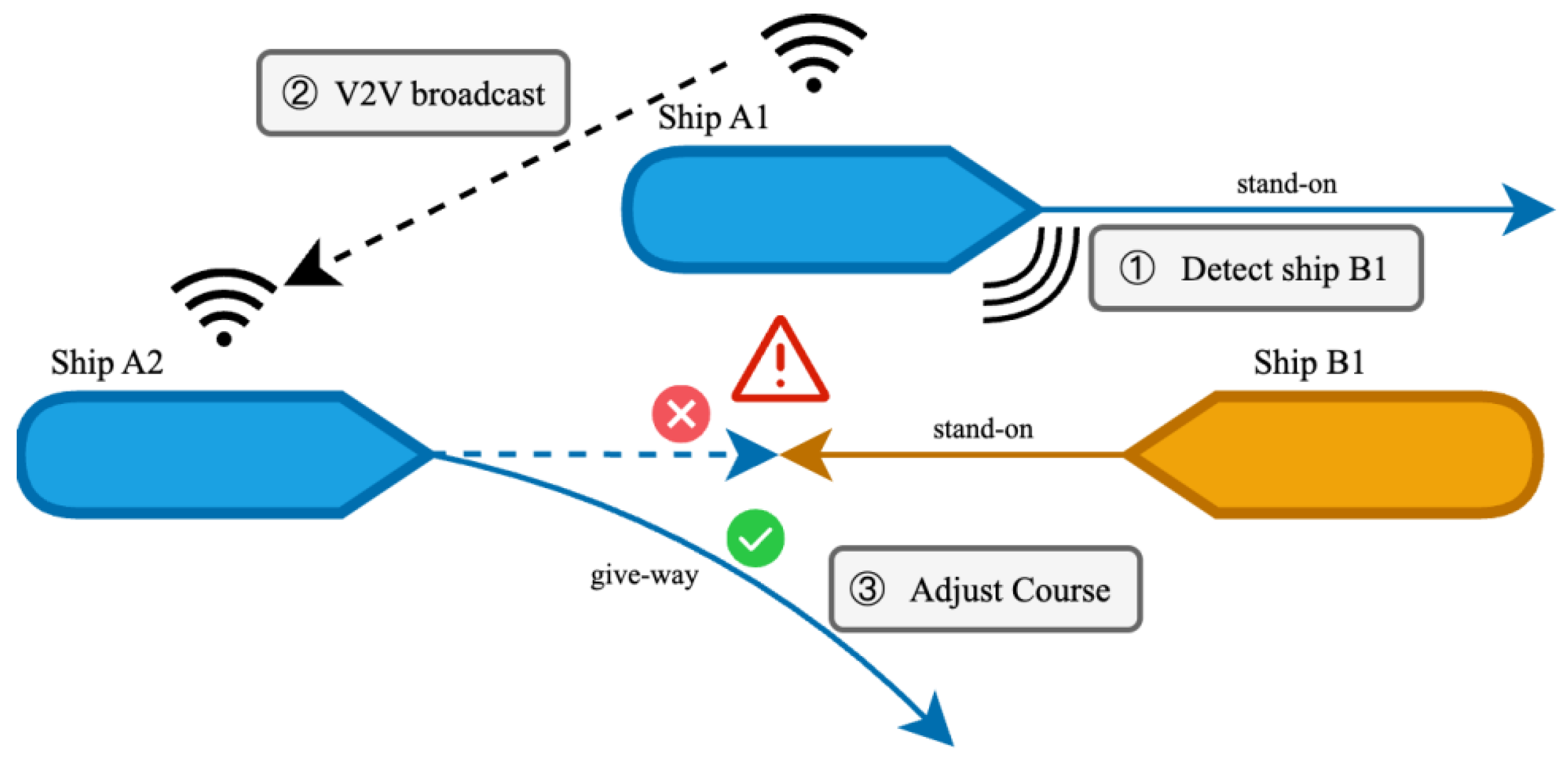

4. Multi-Agent Collision Avoidance

4.1. Collision Avoidance in Collaborative Environment

4.2. Collision Avoidance in Non-Collaborative Environment

5. Challenges and Future Directions

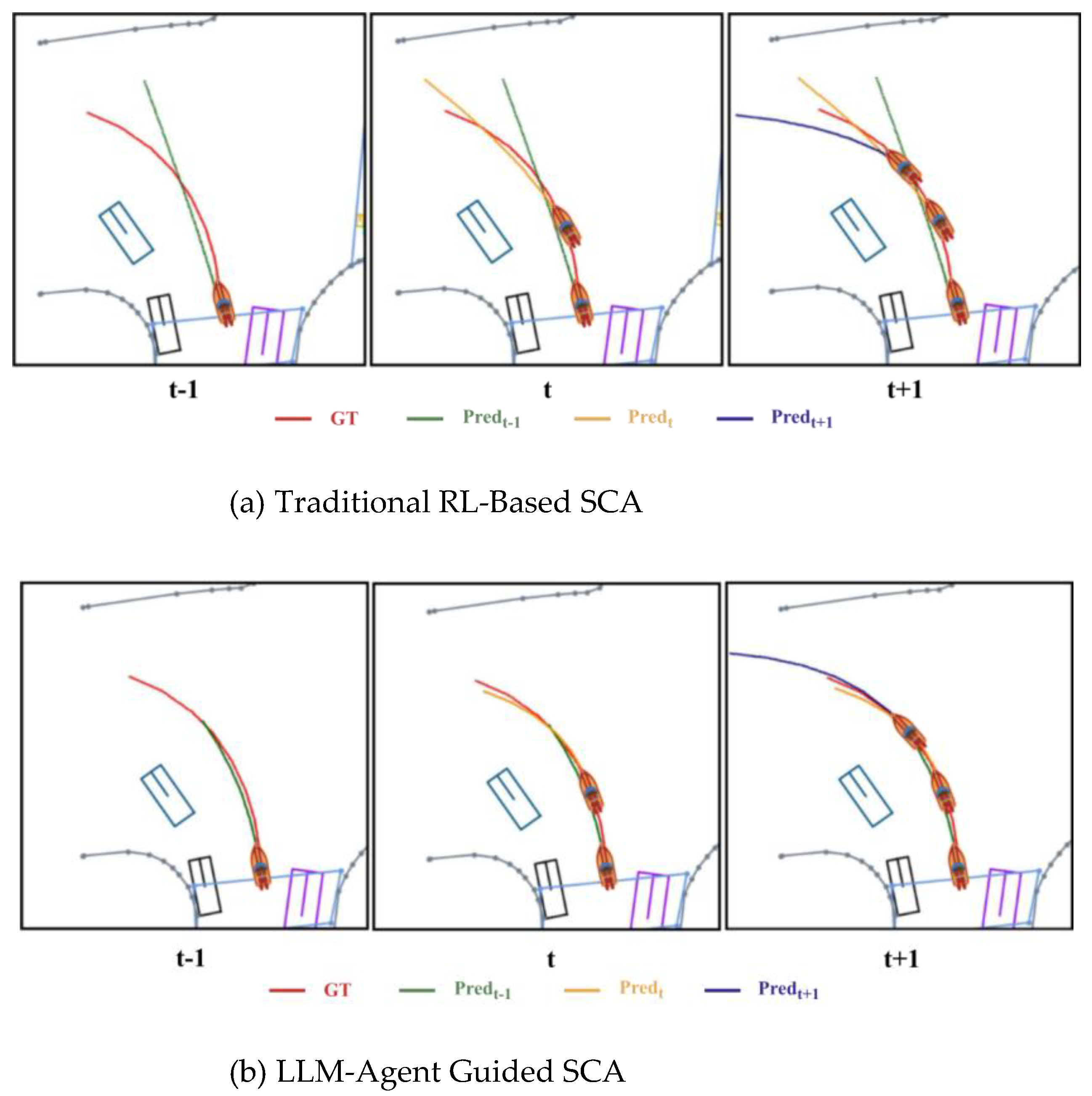

5.1. Limitations and Open Challenges of Present RL Solutions

5.2. LLM Enhanced Decision for SCA

Abbreviations

| AABSRL | Avoidance Algorithm Based on Sarsa on-policy Reinforcement Learning |

| ADRL | Attention-Based Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| ANOA | Autonomous Navigation and Obstacle Avoidance |

| CDRLOA | Concise DRL Obstacle Avoidance |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| COLREGs | Convention on The International Regulations for Preventing Collisions At Sea |

| CPA | Closest Point of Approach |

| DDPG | Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient |

| DE | Differential Evolution |

| DEDRL | Differential Evolution Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| Dec-POMDP | Decentralized Partially Observable Markov Decision Process |

| DQN | Deep Q-Network |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| DRQN | Deep Recurrent Q-network |

| GBDM | Generalized Behavior Decision-Making |

| HRVO | Hybrid Reciprocal Velocity Obstacle |

| ITDRL3 | Three-layer Hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MARL | Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning |

| MDP | Markov Decision Process |

| MLLM | Multi-Modal LLM |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| OZT | Obstacle Zone by Target |

| PER | Prioritized Experience Replay |

| POMDP | Partially Observable Markov Decision Process |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RVO | Reciprocal Velocity Obstacle |

| SCA | Ship Collision Avoidance |

| SMDP | Semi-Markov Decision Process |

| ToT | Tree-of-Thought |

| UANOA | Autonomous Navigation and Obstacle Avoidance in USVs |

| UMVs | Underactuated Unmanned Vessels |

| USVs | Unmanned Surface Vehicles |

| V2V | Vessel-to-Vessel |

| VO | Velocity Obstacle |

| WOS | Web of Science |

References

- Uflaz, E.; Akyuz, E.; Arslan, O.; et al. Analysing human error contribution to ship collision risk in congested waters under the evidential reasoning SPAR-H extended fault tree analysis. Ocean Engineering, 2023, 287, 115758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Ma, X.; Wang, T.; et al. A data-driven approach to determine the distinct contribution of human factors to different types of maritime accidents. Ocean Engineering, 2024, 295, 116874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X. ; qian, Zheng, Q. ; Guo, Y. Maritime accident causation: A spatiotemporal and HFACS-Based approach. Ocean Engineering, 2025, 340, 122329. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorini, P.; Shiller, Z. Motion planning in dynamic environments using velocity obstacles. The international journal of robotics research, 1998, 17, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, den, Berg, J.; Lin, M.; Manocha, D. Reciprocal velocity obstacles for real-time multi-agent navigation. In Proceedings of 2008 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation, Pasadena, CA, USA, 19-23 May 2008; pp. 1928–1935.

- Snape, J. ; Van, Den, Berg, J. ; Guy, S. J. et al. The hybrid reciprocal velocity obstacle. IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 2011, 27, 696–706. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, S. L.; Lee, K. T.; Chang, K. Y.; et al. A fuzzy logic method for collision avoidance in vessel traffic service. The journal of navigation, 2007, 60, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, C. V.; Dunlap, D. D.; Collins, E. G. Motion planning for an autonomous underwater vehicle via sampling based model predictive control. Proceedings of OCEANS 2010 MTS/IEEE SEATTLE, Seattle, WA, USA, 20-23 September 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kaelbling, L. P.; Littman, M. L.; Moore, A. W. Reinforcement learning: A survey. Journal of artificial intelligence research, 1996, 4, 237–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puterman, M. L. Markov decision processes. Handbooks in operations research and management science, 1990, 2, 331–434. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins C J C H, Dayan P. Q-learning. Machine learning, 1992, 8, 279–292.

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. nature, 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillicrap, T. P.; Hunt, J. J.; Pritzel, A.; et al. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1509.02971. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; et al. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, J.; Kim, N. Collision avoidance for an unmanned surface vehicle using deep reinforcement learning. Ocean Engineering, 2020, 199, 107001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E.; Heiberg, A.; Rasheed, A.; et al. COLREG-compliant collision avoidance for unmanned surface vehicle using deep reinforcement learning. Ieee Access, 2020, 8, 165344–165364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Hashimoto, H.; Matsuda, A.; et al. Automatic collision avoidance of multiple ships based on deep Q-learning. Applied Ocean Research, 2019, 86, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busoniu, L.; Babuska, R. ; De, Schutter. B. Multi-agent reinforcement learning: A survey. In Proceedings of 2006 9th international conference on control, automation, robotics and vision, Singapore, 05-08 December 2006; pp. 1–6.

- Chen, C.; Ma, F.; Xu, X.; et al. A novel ship collision avoidance awareness approach for cooperating ships using multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2021, 9, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Hashimoto, H.; Matsuda, A. Artificial Intelligence for Cooperative Collision Avoidance of Ships Developed by Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. Proceedings of International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Singapore, 09-14 June, 2024; pp. 125392–125400.

- Zheng, S.; Luo, L. Multi-Agent Cooperative Navigation with Interlaced Deep Reinforcement Learning. Proceedings of 2024 IEEE 6th International Conference on Civil Aviation Safety and Information Technology (ICCASIT), Hangzhou, China, 23-25 October, 2024; pp. 409–414.

- Wang, Z.; Chen, P.; Chen, L.; et al. Collaborative Collision Avoidance Approach for USVs Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2025, 26, 4780–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tang, P.; Su, Y.; et al. An adaptive obstacle avoidance algorithm for unmanned surface vehicle in complicated marine environments. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica, 2014, 1, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Pang, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Local path planning method of the self-propelled model based on reinforcement learning in complex conditions. Journal of Marine Science and Application, 2014, 13, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhopale, P.; Kazi, F.; Singh, N. Reinforcement learning based obstacle avoidance for autonomous underwater vehicle. Journal of Marine Science and Application, 2019, 18, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, H.; Chen, C.; et al. The autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance for USVs with ANOA deep reinforcement learning method. Knowledge-Based Systems, 2020, 196, 105201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Huang, S.; Kong, C. Reinforcement Learning-Based Autonomous Navigation and Obstacle Avoidance for USVs under Partially Observable Conditions. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2021, 2021, 5519033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, W. Concise deep reinforcement learning obstacle avoidance for underactuated unmanned marine vessels. Neurocomputing, 2018, 272, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Hashimoto, H.; Matsuda, A.; et al. Automatic collision avoidance of multiple ships based on deep Q-learning. Applied Ocean Research, 2019, 86, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Roh, M. I. COLREGs-compliant multiship collision avoidance based on deep reinforcement learning. Ocean Engineering, 2019, 191, 106436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, P.; Zhang, Y.; Shaobo, W. Intelligent ship collision avoidance algorithm based on DDQN with prioritized experience replay under COLREGs. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2022, 10, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayrac, J. B.; Donahue, J.; Luc, P.; et al. Flamingo: a visual language model for few-shot learning. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2022, 35, 23716–23736. [Google Scholar]

- Sawada, R.; Sato, K.; Majima, T. Automatic ship collision avoidance using deep reinforcement learning with LSTM in continuous action spaces. Journal of Marine Science and Technology, 2021, 26, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ma, F.; Xu, X.; et al. A novel ship collision avoidance awareness approach for cooperating ships using multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2021, 9, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Liu, S.; Lin, Y. Dynamic navigation and area assignment of multiple USVs based on multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. Sensors, 2022, 22, 6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantogma, S.; Zhang, S.; Yu, X.; et al. Multi-USV dynamic navigation and target capture: A guided multi-agent reinforcement learning approach. Electronics, 2023, 12, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wang, X.; Cao, X.; et al. Multi-USV Formation Control and Obstacle Avoidance Under Virtual Leader. Proceedings of 2023 China Automation Congress (CAC), Chongqing, China, 17-19 November 2023; pp. 3411–3416.

- Glorennec, P. Y.; Jouffe, L. ; Fuzzy Q-learning. Proceedings of 6th international fuzzy systems conference, Barcelona, Spain, 05-05 July, 1997; pp. 659–662.

- Zhang, J.; Ren, J.; Cui, Y.; et al. Multi-USV task planning method based on improved deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2024, 11, 18549–18567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockman, G.; Cheung, V.; Pettersson, L.; et al. Openai gym. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.01540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Xiao, Y. Intelligent ships collision avoidance and navigation method based on deep reinforcement learning. Proceedings of 2021 International Conference on Computer Information Science and Artificial Intelligence (CISAI), Kunming, China, 17-19 September, 2021; pp. 573–578.

- Jiang, L.; An, L.; Zhang, X.; et al. A human-like collision avoidance method for autonomous ship with attention-based deep reinforcement learning. Ocean Engineering, 2022, 264, 112378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, C.; et al. Generalized behavior decision-making model for ship collision avoidance via reinforcement learning method. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2023, 11, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Weng, J.; Zhou, Y. Ship collision avoidance method in starboard-to-starboard head-on situations. Proceedings of 2023 7th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety (ICTIS), Xi’an, China, 04-06 August, 2023; pp. 609–614.

- Niu, Y.; Zhu, F.; Zhai, P. An autonomous decision-making algorithm for ship collision avoidance based on DDQN with prioritized experience replay. Proceedings of 2023 7th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety (ICTIS), Xi’an, China, 04-06 August, 2023; pp. 1174–1180.

- Zheng, K.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; et al. A partially observable multi-ship collision avoidance decision-making model based on deep reinforcement learning. Ocean & Coastal Management, 2023, 242, 106689. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Liao, Z.; Chen, D. Differential Evolution Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithm for Dynamic Multiship Collision Avoidance with COLREGs Compliance. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2025, 13, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. P. ; Sutton, R, S. Reinforcement learning with replacing eligibility traces. Machine learning, 1996, 22, 123–158. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Yu, D.; Zhao, J.; et al. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2023, 36, 11809–11822. [Google Scholar]

| Scene type | Triggering condition | Reward value | Key parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful SCA | no collision risk | +10,) | Sub-reward weights: |

| Collision penalty | distance to the target vessel | -10 | Critical distance threshold: 0.3 NM |

| Potential risk penalty | Predicting danger | -1 | Observation vector dimension: 35 danger sectors |

| Neutral state | No significant events | 0 | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).