1. Introduction

Autonomous driving is currently a highly popular research topic in the mobility area with immense potential to enhance safety, reduce traffic congestion, and revolutionize urban transportation [

1,

2]. However, one of the major challenges in the development of autonomous vehicles is ensuring collision-free navigation in dynamic and unpredictable environments [

3,

4]. This challenge becomes particularly significant in environments ranging from multi-lane highways with fast-moving traffic [

5] to crowded urban settings where vehicles must navigate amidst pedestrians [

6].

Extensive research has been conducted in the field of autonomous driving to develop high-performance and robust collision avoidance systems. Currently, most path planning and collision avoidance research focuses on two major approaches. The first is the optimization-based approach which frames path planning and collision avoidance as an optimization problem with well-defined constraints. The objective is to compute an optimal, collision-free trajectory by minimizing or maximizing specific objective functions. Among the various methods, the CLF-CBF-QP approach stands out as one of the most favored and widely used. This method formulates path following and collision avoidance as constraints using Control Lyapunov Functions (CLF) for stability and Control Barrier Functions (CBF) for safety. The optimal control is then calculated by solving a Quadratic Programming (QP) problem, ensuring both efficient and safe navigation. Ames et al. introduced a novel framework that unifies safety conditions, expressed as CBFs, with control stability objectives, represented by CLFs, within a QP setting. This framework was applied to design adaptive cruise control that balanced speed following performance with safety constraints to ensure the vehicle maintains a safe following distance [

7]. Later, Ames et al. further explored the application of CBF in safety-critical systems and introduced two new types: reciprocal and zeroing. By integrating these functions, their methodology ensured the forward invariance of safe sets while effectively balancing safety and performance. The proposed method was demonstrated in applications such as adaptive cruise control and lane keeping [

8,

9]. He et al. proposed to integrate a Finite State Machine (FSM) with the CLF-CBF-QP framework for autonomous vehicles, focusing on safe lane change maneuvers in dynamic traffic environments. Their method ensured real-time safety constraints during lane changes [

10]. Wang et al. introduced a decentralized method for ensuring collision-free operation in multirobot systems using Safety Barrier Certificates. Their approach utilized CBFs to modify nominal controllers minimally while ensuring safety constraints are satisfied in real-time applications [

11]. Liu et al. compared potential games-based reinforcement learning and traditional CBF based approach for decision-making in autonomous driving. Their study highlighted that while potential games offer robustness in non-safety-conscious environments, CBFs are more computationally efficient and feasible for real-time applications [

12]. Reis et al. integrated spline-based barrier functions for path following in multi-vehicle scenarios. Their approach integrated CLFs, elliptical CBFs and spline-based CBFs to ensure smooth and collision-free navigation, particularly useful for highway driving with dynamic lane changes and vehicle interactions [

13]. Moreover, Desai et al. introduced a CLF-CBF framework to handle nonholonomic mobile robots navigating around moving obstacles. Their approach included constraints on the steering angle to avoid impractical maneuvers, optimizing the trade-off between safety and control smoothness and achieved smooth avoidance performance [

14]. Long et al. proposed a distributionally robust Lyapunov Function (LF) search method for closed-loop dynamical systems under uncertainty which can learn LFs with neural network (NN) [

15], while Chang et al. proposed another method for learning control policies and NN-LF which can significantly simplify the process of Lyapunov function design and provide end-to-end correctness guarantee [

16]. Meanwhile, numerous optimization-based autonomous driving control approaches have been explored that do not rely on CLF-CBF frameworks [

17,

18,

19,

20] such as Elastic Band algorithm [

21], potential field based approach [

22], Support Vector Machines (SVM) based approach [

23], quintic spline optimization approach [

24] and hybrid A* search in spatiotemporal map [

25]. However, the major limitations of the traditional optimization approach are its deficiency in real-time performance caused by computational complexity and its shortage on control feasibility.

The second approach is the machine learning method which considers autonomous driving and collision avoidance tasks as Markov Decision Processes (MDP) and utilizes the reinforcement learning (RL) method to find optimal solutions. This approach makes concurrent optimization of all processing phases possible and eventually yields superior performance. Kendall et al. pioneered the application of DRL framework in autonomous driving, innovatively proposing an end-to-end model structure for autonomous driving [

26]. Yurtsever et al. proposed an innovative hybrid deep-reinforcement-learning framework to develop Automated Driving Systems (ADS) [

27]. Smith et al. proposed a novel load balancing framework that integrates CBFs with DRL to ensure both safety and efficiency in dynamic network environments. Their approach guarantees system stability by enforcing safety constraints through CBFs while DRL optimizes load distribution in real-time [

28]. Ashwin et al. proposed a DDPG-based sequential decision algorithm for autonomous vehicles, focusing on lane-keeping and overtaking scenarios. Their approach trains vehicles to navigate lanes, overtake static and moving obstacles, and avoid collisions, demonstrating effective performance in TORC traffic simulator [

29]. Muzahid et al. introduced a DRL-based driving strategy aimed at preventing chain collisions in autonomous traffic flow. By considering the behavior of both leading and following vehicles, their method effectively mitigates the risk of multi-vehicle collisions in high-density traffic scenarios [

30]. Emuna et al. introduced a model-free DRL approach to imitate human driving behavior in collision avoidance tasks. Their control algorithm combines model-driven rules with data-driven human expert knowledge, resulting in human-like driving policies in simulated highway scenarios [

31]. Chen et al. applied a double deep reinforcement learning controller to the safety of vulnerable road users during their interactions with autonomous vehicles [

32]. However, a notable disadvantage of the machine learning-based approach is the instability in model performance under normal traffic condition due to the absence of hard-coded safety protocols.

In this paper, we propose a novel approach that combines traditional optimization-based control design with DRL to develop a high-performance and robust control strategy for autonomous vehicles. The proposed control system enables precise path tracking when no potential collisions are detected and performs effective collision avoidance when obstacles are nearby. To achieve this, we first apply the CLF-CBF-QP approach to design an optimization-based path-tracking controller. The CLF constraint in the optimization ensures the stability and accurate path tracking of the autonomous vehicle, while the CBF constraint guarantees safety by preventing potential collisions between the vehicle and obstacles. Building on this foundation, we integrate the traditional CLF-CBF-based control with a deep reinforcement learning algorithm for path planning. The DRL algorithm generates a rough sketch of the optimal path, which the proposed optimization-based control then refines and executes. To further enhance computational efficiency, a lookup table is incorporated into the CLF-CBF optimization framework, significantly accelerating the calculation process. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both traditional control theory and modern machine learning to achieve robust, safe, and efficient autonomous vehicle operation.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces the methodologies employed in this study, including the unicycle vehicle dynamic model, the principles and design of the CLF and CBF, and the DRL frameworks.

Section 3 presents the simulation results of the proposed algorithm, covering CLF-based path-tracking control, CLF-CBF path-tracking and collision-avoidance control for both static and dynamic obstacles, and the design of a hybrid CLF-CBF-based DRL autonomous driving agent. Detailed results and analysis are provided in this section. Finally,

Section 4 concludes the paper and discusses potential directions for future work.

2. Methodology

To develop a high-performance and robust autonomous driving algorithm for navigating an autonomous vehicle from a starting point to an endpoint while performing collision avoidance as needed, we first present a simple unicycle vehicle dynamic model. After that we introduce the basic principle of CLF and CBF and demonstrate how to design optimization-based control using CLF-CBF-QP approach for autonomous vehicle. Finally, we introduce how to integrate CLF-CBF-QP control with deep reinforcement learning techniques to create a comprehensive algorithm for autonomous vehicles.

2.1. Unicycle Vehicle Dynamics

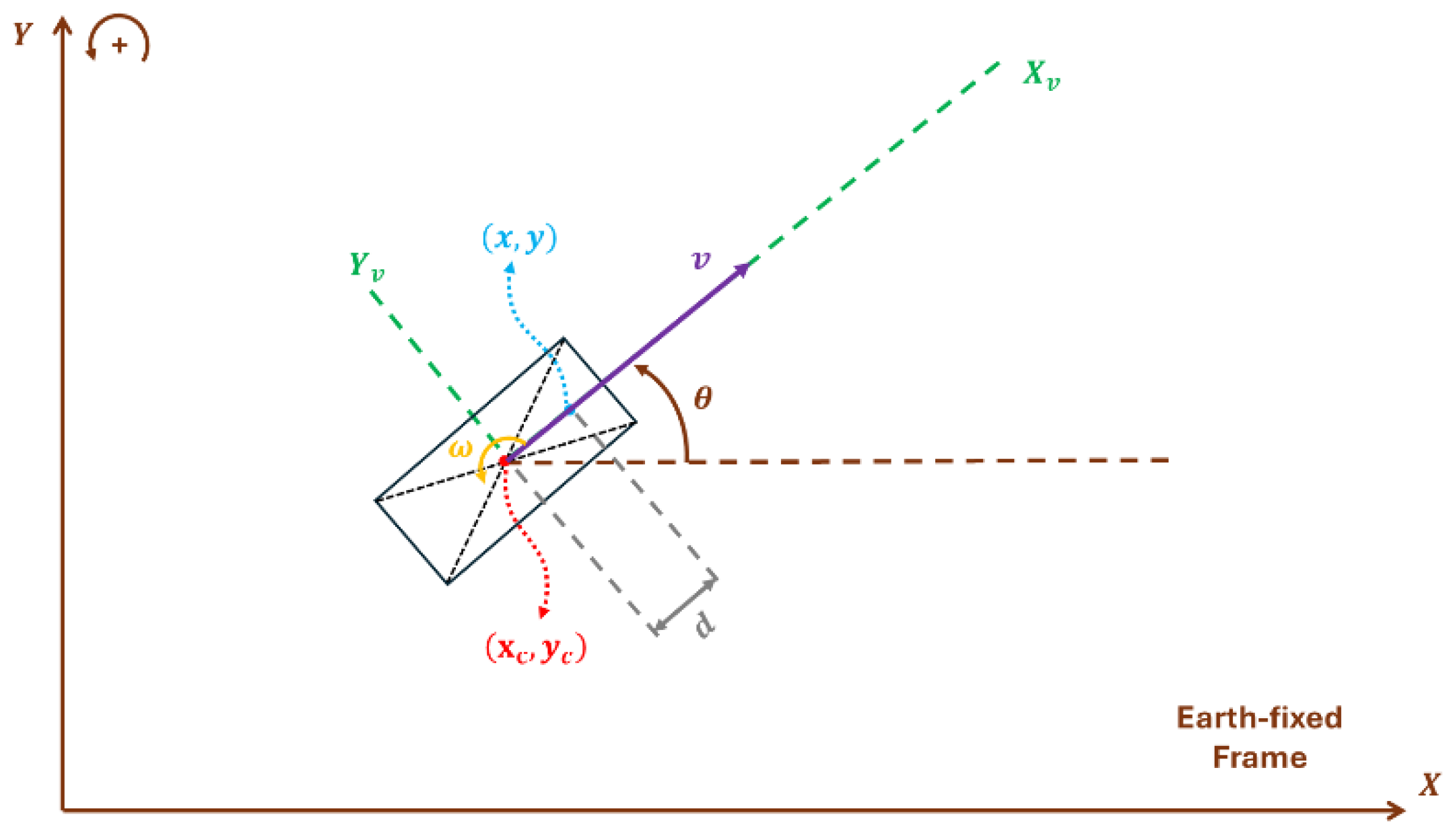

In this paper, we propose to use a unicycle vehicle model for dynamic simulation of the vehicle.

Figure 1 illustrates the plane motion of this unicycle vehicle. The vehicle can move forward with various speed and rotate with various angular speed around its geometry center. Note that this is also the Dubins model of a vehicle if we fix the speed and limit the rotation angle. The state-space equation for this vehicle model is

where

is the geometric center coordinates of the vehicle and

donates the orientation of the vehicle. Now, consider another point

located at a different position along the longitudinal axis

xv of the vehicle. This point is located at an offset distance

along the vehicle's x-axis relative to the geometric center. The relationship between point

and vehicle’s geometry center

can be represented using equations below.

The state-space equation for the geometric center of the vehicle is given by

Both state-space equations (1) and (3) are driftless nonlinear systems which rely entirely on control inputs to define their motion. They are particularly useful for autonomous driving research, as they simplify the analysis and synthesis of control laws without the need to counteract drift dynamics. Moreover, the simplicity of the unicycle model largely simplifies the design of Control Lyapunov Function and Control Barrier Functions by streamlining the calculations. For realistic simulation, we construct the model in both Python and Simulink for MIL and real time MIL simulation. The simulation setting and results are demonstrated in the results section.

2.2. Control Lyapunov Functions and Control Barrier Functions

2.2.1. Control Lyapunov Function Principle and Design

The CLF is usually used as a constraint of an optimization problem to ensure the stability of dynamic systems by defining a scalar function that decreases over time as the system evolves. By encoding stability criteria into a function, the CLF allows the system to converge to the desired state with reasonable speed despite dynamic and environmental uncertainties. In autonomous driving, a CLF is employed to design path-tracking controller that guides the vehicle towards the desired target position. This approach is robust in real-time applications where stability must be maintained even in the presence of disturbances, ensuring that the autonomous vehicle operates reliably and efficiently. Through CLF-based control strategies, vehicles can achieve precise trajectory tracking even in complex driving scenarios, which makes it a foundational element in advanced autonomous driving algorithms.

Let us first introduce the basic principle of CLF. Consider the control affine system given by

where

is the state vector,

is the control input vector,

and

are Lipschitz continuous in

.

is the uncontrolled part, which represents the system’s natural dynamics, while

is the control distribution matrix which determines how the control inputs influence the system’s dynamics. Let

be a continuously differentiable function, a CLF

satisfies:

- (1)

Positive definiteness:

where

is the equilibrium point.

- (2)

Sublevel set boundedness: For a given constant , the sublevel set, is bounded. This ensures that defines a meaningful region of attraction (ROA) around .

- (3)

Stability: There exists a control input

such that the derivative of

along the trajectory of the system satisfies:

In this paper, the CLF is applied to design the path-tracking controller, ensuring the vehicle accurately follows a predefined trajectory. Equations 7 and 8 given below demonstrate the design of a Lyapunov function and its derivative where

is the path tracking error. The path tracking error can be calculated using the position of vehicle and the position of tracking point on the path,

, where

represents the planar parameterized path, generated by B-Spline fitting for example, and

is a time dependent parameter for position along the path. Equation 6 demonstrates the dynamics of the path where desired path speed is

and

is used to slow down the tracking point when the path tracking error is too large. The CLF incorporates the path-tracking error, quantifying the deviation of the vehicle from the desired path. By integrating the CLF as a constraint within the quadratic programming (QP) optimization problem, the controller ensures that the system minimizes the path-tracking error at every time step. This formulation guarantees stability by driving the CLF to decrease over time, ultimately forcing the vehicle to converge to the predefined path. The detailed design of CLF is illustrated in Equation 10 where

is the relaxing term which indicates that the vehicle can temporarily deviate from the path when necessary.

2.2.2. Control Barrier Functions Principle and Design

The Control Barrier Function (CBF) is usually used as a constraint of an optimization problem to ensure the safety of dynamic systems. A CBF defines a safe set which is a region in the state space where the system can operate without violating safety conditions. By incorporating CBF constraints into optimization-based controllers, the controller ensures that the system remains within the defined safe set while allowing flexibility for other objectives such as stability or performance. In the context of autonomous driving, CBFs are usually employed to guarantee collision avoidance, maintain lane adherence, and respect speed limits. In this paper, we use CBF to enforce minimum distance constraints between the autonomous vehicle and obstacles, ensuring safe operation in dynamic environments. By integrating CBFs with other constraints such as CLF, optimization-based control strategy can be designed for autonomous vehicles. This approach enables simultaneous achievement of safety, efficient path tracking, and effective collision avoidance.

For CBF, let

be a continuously differentiable function that defines the safe set

where

represents the safe region, and

represents the unsafe region. The function

is considered a CBF if there exists a control input

such that the following condition holds for all

.

where

is a class-

function, which specifies the rate at which the system can approach the boundary of the safe set.

In this paper, the CBF is utilized to design the collision avoidance controller, ensuring the vehicle's safety in the presence of nearby obstacles. To simplify the problem and enable an effective mathematical formulation, we assume that both the vehicle and obstacles have elliptical geometries. This assumption allows the use of an ellipse-based barrier function, which defines a safe region by ensuring that the vehicle maintains an appropriate distance from obstacles. Equations 13 is the barrier function of elliptical region with

and

. The center of this elliptical region is located at

and the orientation of the region is

. Equation 14 represent the boundary of the aforementioned elliptical region where

is the rotation angle between 0 to

. Equation 14 demonstrates the design of barrier function between two arbitrary elliptical regions

i and

j where

represents the barrier function of elliptical region

i,

represents the boundary function of the elliptical region

j, and

represent the position and orientation of the two elliptical regions. By incorporating this barrier function into the control framework, the vehicle can dynamically adjust its trajectory to avoid collisions while preserving stability and operational efficiency. The detailed design of CBF is illustrated in Equation 16.

2.2.3. CLF-CBF-QP Formulation

After designing the appropriate CLF and CBF constraints for the optimization-based controller, the next step is to formulate the CLF-CBF-QP framework. The complete formulation of the CLF-CBF-QP is presented in Equation 17.

By solving this optimization problem, the autonomous vehicle can effectively avoid potential collisions with obstacles, achieve accurate path tracking to the greatest extent possible, and minimize control effort while ensuring efficient and safe navigation.

2.3. Deep-Reinforcement-Learning

Autonomous can be viewed as inherently being a Markov Decision Process (MDP) problem, as it requires continuous decision-making in a highly uncertain and dynamic traffic environment. This means that the system must account for evolving traffic conditions, unpredictable obstacles and vulnerable road users (VRUs), and complex interactions with other road users while making sequential decisions to achieve safe and efficient navigation. Due to these characteristics, DRL has emerged as a promising tool for tackling this challenge. DRL has been extensively researched for developing advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS), leveraging its ability to learn optimal policies directly from interactions with the environment. Currently, most research focuses on end-to-end DRL approaches where raw sensor inputs, such as images or videos, are directly processed to generate control commands for the vehicle. For instance, an autonomous vehicle may use camera images to predict steering angles or acceleration commands. This approach has several advantages: it simplifies the optimization process by avoiding the need for intermediate steps, such as feature extraction or trajectory planning, and allows the system to optimize all stages of decision-making and control simultaneously in a unified framework. Additionally, end-to-end methods are usually model-free and can adapt to complex scenarios by learning directly from large-scale data, capturing patterns that may be difficult to model explicitly.

However, the end-to-end DRL approach also presents significant limitations. One major drawback is the requirement for extensive computational resources to train the DRL agent effectively, often requiring large datasets and substantial training time. Another critical issue is the difficulty of incorporating hard-coded safety rules into the learned policy. While DRL excels at finding solutions that work well in training environments, it may fail to ensure safety under untrained or extreme conditions, which is unacceptable for real-world autonomous driving applications. These limitations highlight the need for a hybrid approach that combines the strengths of DRL with traditional optimization-based control methods.

To address these challenges, we propose a novel framework that integrates DRL with traditional CLF-CBF based control. In this hybrid framework, DRL is utilized for high-level decision-making, such as generating rough path plans and determining strategic maneuvers based on environmental conditions. This enables the system to leverage DRL's data-driven capabilities for better decision-making and adaptability in complex and uncertain environments. On the other hand, the CLF-CBF-based control is responsible for refining and executing the planned paths, ensuring the vehicle's stability, safety, and efficiency during operation. By separating high-level decision-making from low-level control, this approach combines the flexibility and learning capabilities of DRL with the robustness and safety guarantees provided by traditional control techniques. This hybrid method not only addresses the limitations of end-to-end DRL approaches but also ensures that the autonomous vehicle can operate reliably and safely in a wide range of scenarios while benefiting from the strengths of both methodologies.

DRL can be broadly categorized into two methods: value-based approach and policy-based approach. Value-based DRL, inspired by Q-learning [

15], focuses on estimating the value of different actions to determine the best one. Deep Q-Networks (DQN) and its successor [

16,

17,

18,

19] extend this by using neural networks to approximate Q-values in environments with large state spaces. On the other hand, policy-based DRL methods directly learn the policy, which maps states to actions without explicitly estimating value functions. Policy Gradient (PG) methods, inspired by REINFORCE [

20], Actor-Critic [

21], such as A2C, A3C [

22], PPO [

23] and their successors [

24,

25,

26], optimize the policy by adjusting its parameters in the direction that maximizes expected rewards. Both approaches in DRL are widely utilized in the field of autonomous driving [

27,

28,

29,

30].

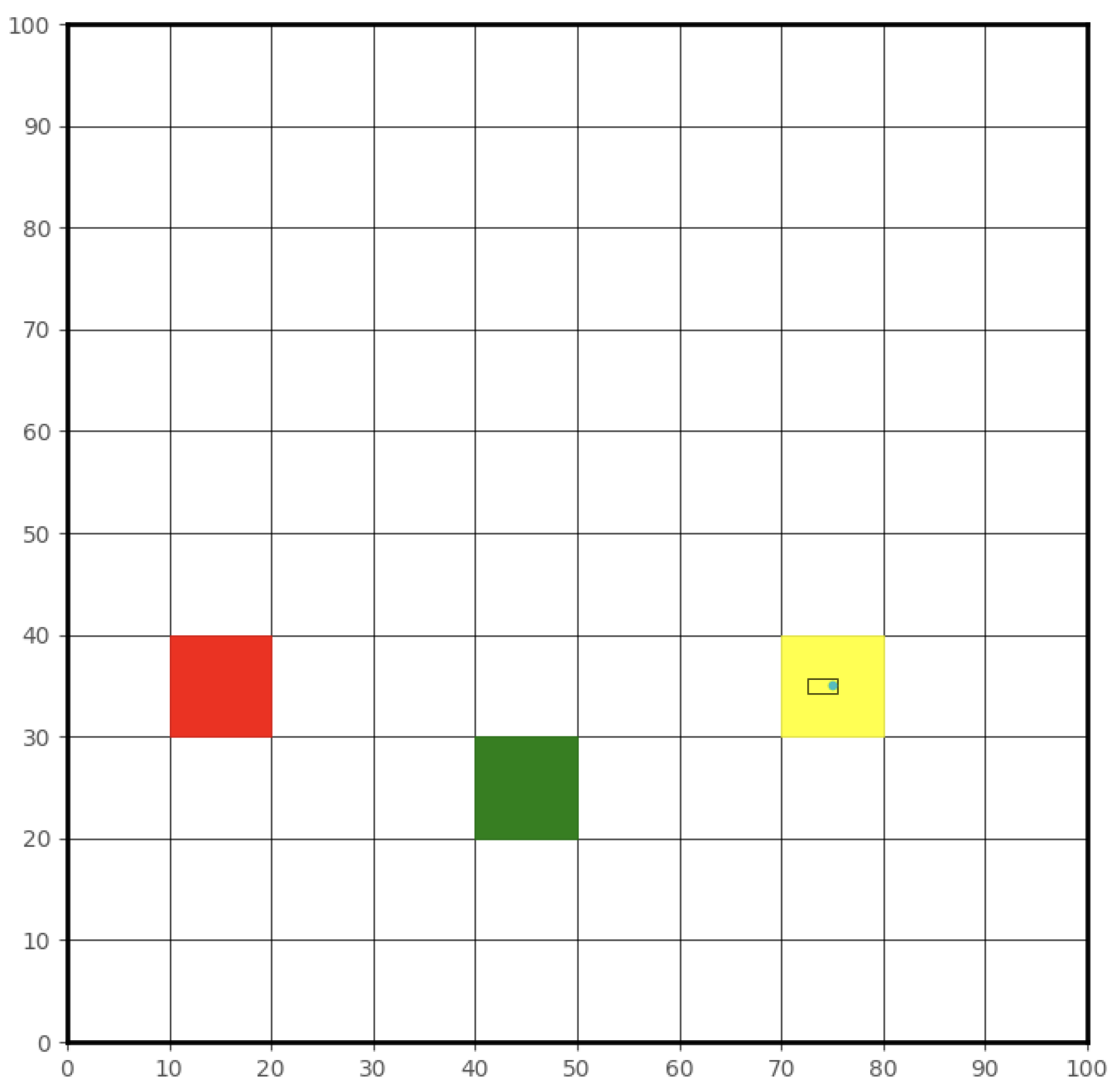

In this paper, we propose using the DQN framework to design the high-level control for autonomous driving. DQN, as a value-based reinforcement learning algorithm, offers several advantages over policy-based algorithms. It is computationally efficient, particularly for discrete action spaces, and can achieve stable convergence with techniques like experience replay and target networks. These properties make DQN an ideal choice for handling high-level decision-making in structured environments. To implement this, we convert the driving environment into a grid map, where the map is divided into discrete grids. Each grid represents a specific location, with grids containing the destination and obstacles distinctly marked. At each time step, the DQN framework determines a high-level decision, guiding the vehicle to move to a nearby grid based on its learned policy. The CLF-CBF controller then executes these high-level decisions, refining the vehicle's trajectory and ensuring stability, safety, and efficiency throughout the process. This combination of DQN for decision-making and CLF-CBF for control execution ensures a robust and effective approach to autonomous driving in dynamic environments.

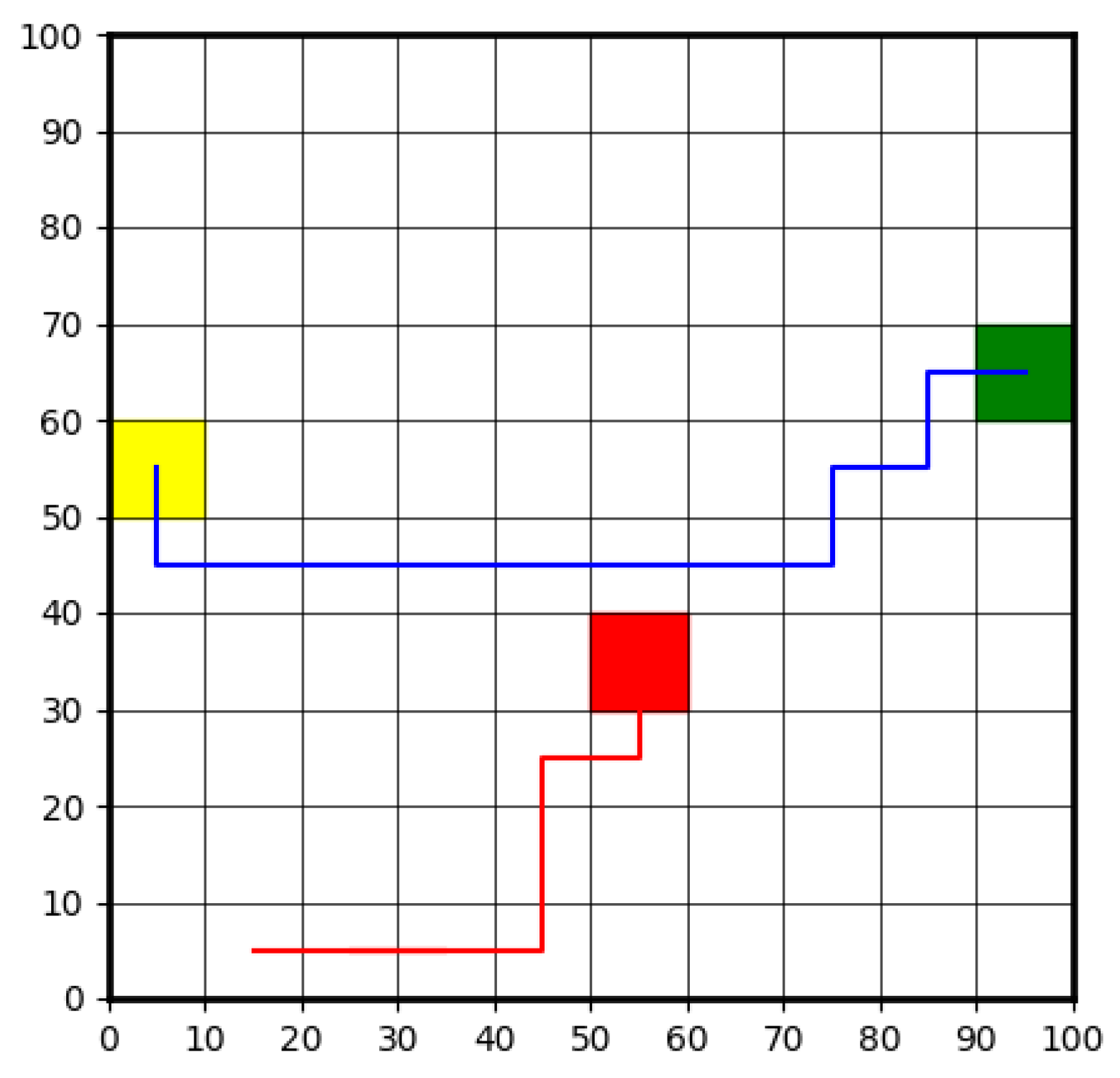

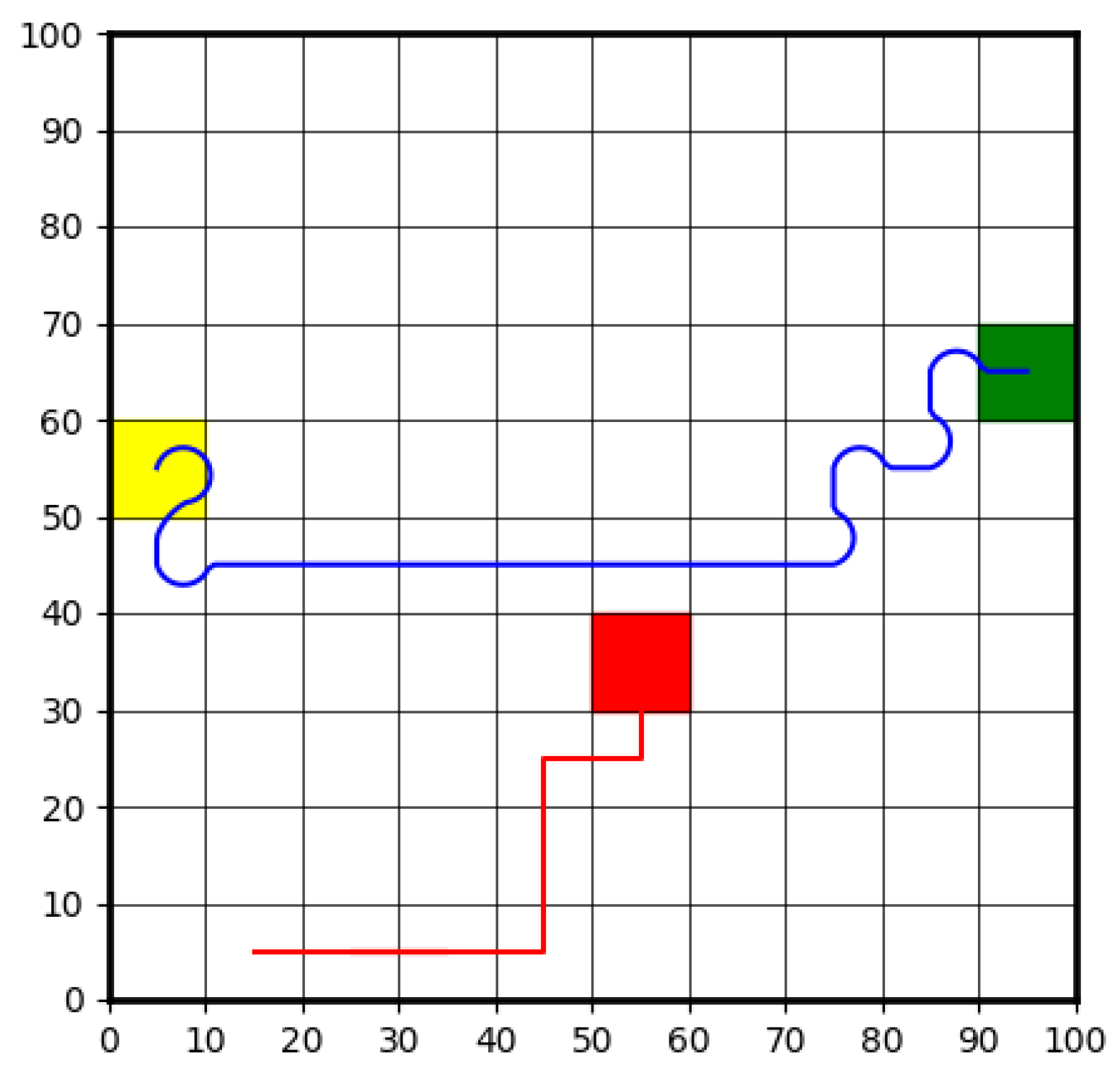

Figure 2 illustrates an example of the traffic environment which can be using to train a DRL based high level decision-making agent. The yellow grid represents the vehicle's current position, while the red grid indicates the presence of a dynamic obstacle. The green grid marks the destination. The vehicle's objective is to navigate around the dynamic obstacle and reach the destination as quickly as possible. The DRL-based high-level decision-making agent is responsible for generating basic navigation commands, such as moving to the grid above or below the current position. These commands serve as guidance for the overall trajectory planning. The CLF-CBF-QP-based low-level controller, in turn, interprets and executes these commands with precision, ensuring smooth and safe motion while adhering to vehicle dynamics and avoiding collisions. This hierarchical structure enables the seamless integration of high-level strategic decision-making with low-level control execution, providing both flexibility and robustness in navigation.

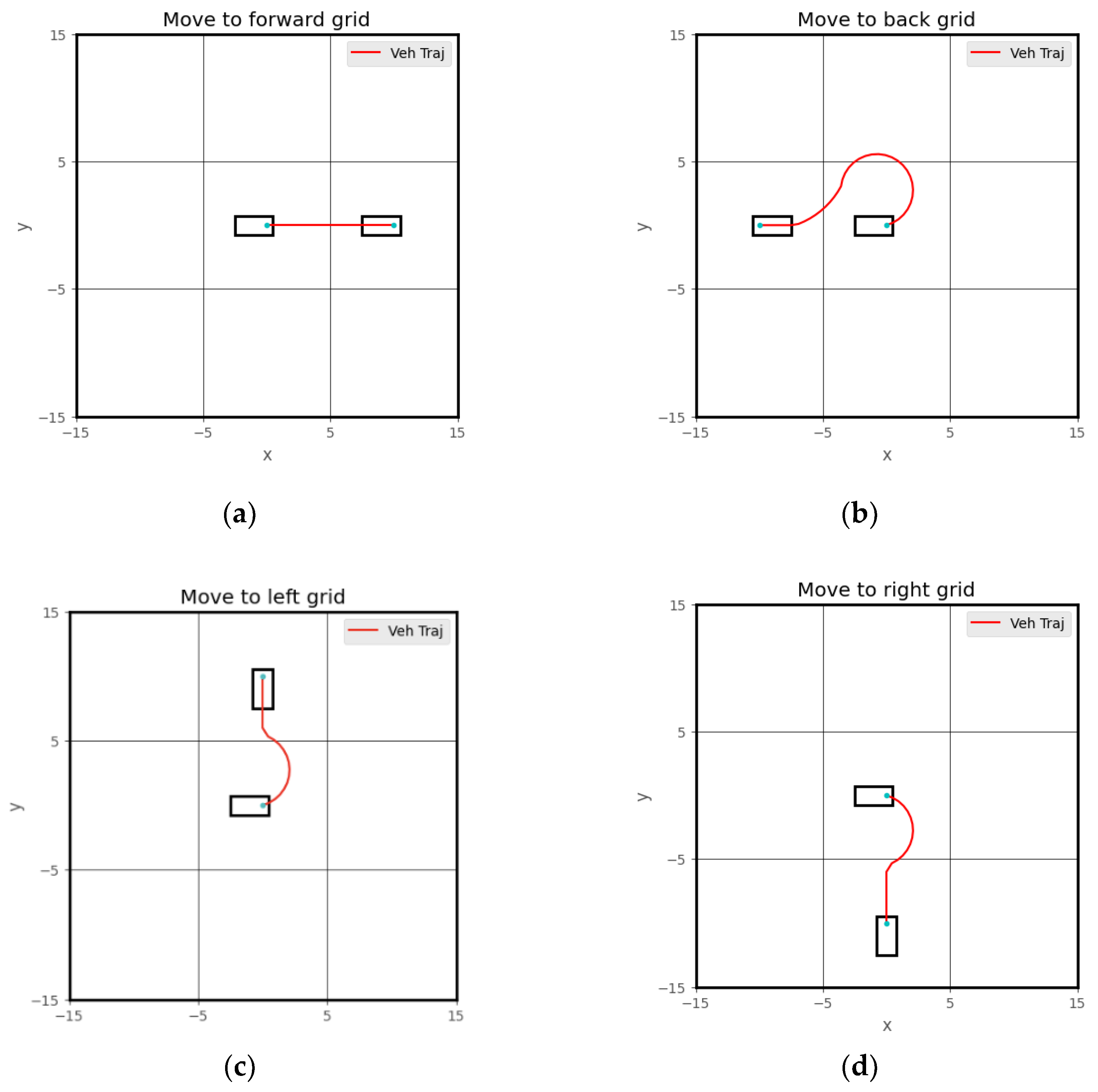

Figure 3 demonstrates how to use the CLF-CBF controller to execute high-level steps generated by the DRL agent. Each high-level decision corresponds to a unique trajectory. After the DRL-based high-level controller decides, the CLF-CBF controller ensures the vehicle moves from the center of the current grid to the center of the next grid. Notably, there are two possible ways to move to the grid behind the vehicle: either a left turn or a right turn, both of which are feasible. To handle such scenarios, an additional rule-based algorithm can be incorporated to select the optimal path based on specific conditions. Furthermore, the DRL controller may occasionally decide that the vehicle should remain stationary. If the DRL chooses not to move, the low-level controller will maintain the vehicle's position until the next time step.

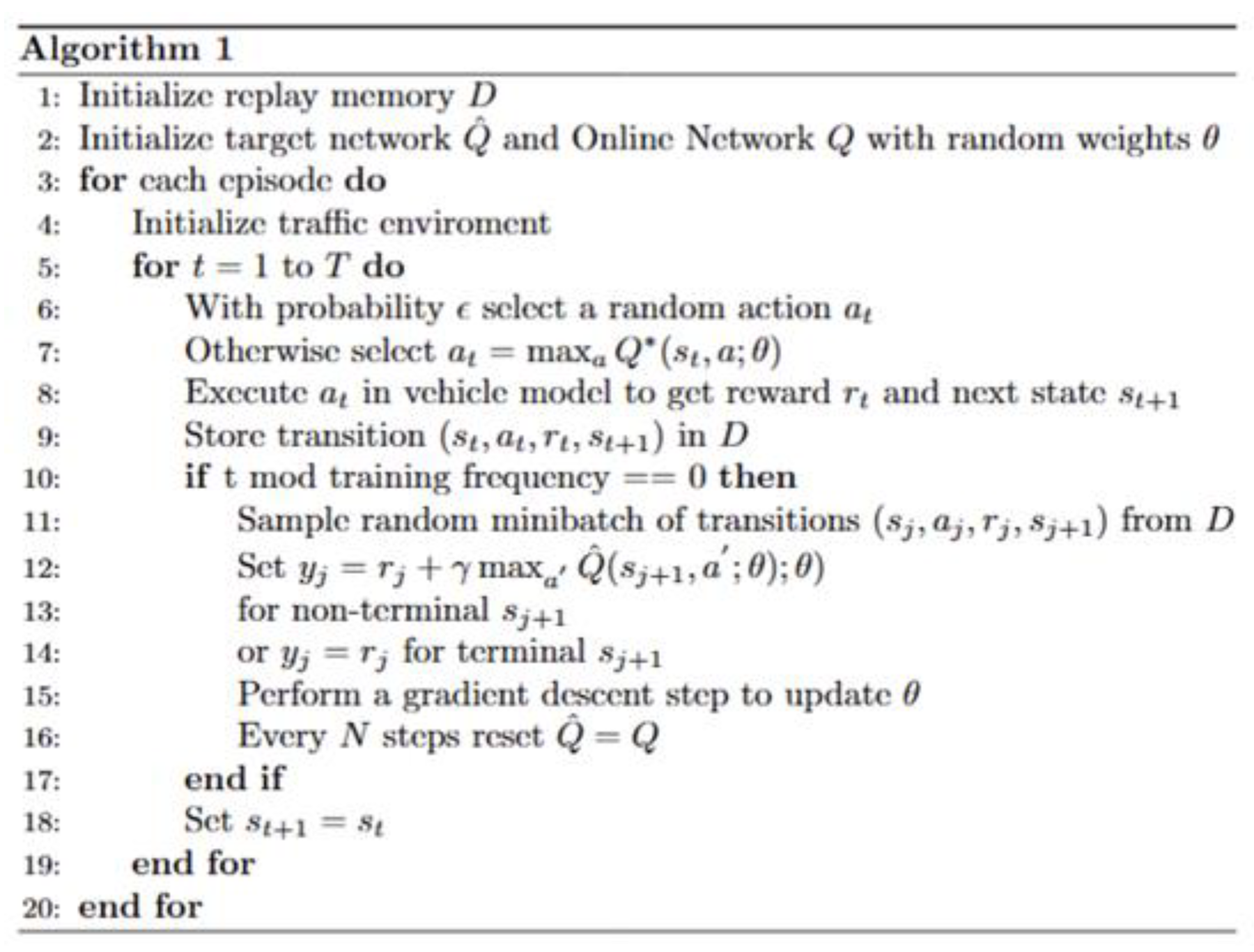

Figure 4 demonstrates the DQN framework that is used to train the autonomous driving high-level decision-making agent in this paper. The proposed DQN agent contains two hidden layers that each contain 32 neurons.

3. Results

In this section, we present the simulation results of the proposed controller to evaluate its performance and robustness. First, the CLF-based path-tracking simulation results are shown, highlighting the controller's ability to achieve precise path tracking under normal conditions. Next, the simulation results of the CLF-CBF-based autonomous driving controller are shown for scenarios involving both static and dynamic obstacles. These results illustrate the vehicle's capability to maintain precise path tracking during normal traffic conditions and effectively execute collision avoidance maneuvers in emergency situations. Finally, we present the simulation results of the hybrid framework, where the DQN-based high-level decision-making agent is combined with the CLF-CBF-based low-level controller. These results demonstrate how integrating traditional optimization-based controllers with deep reinforcement learning can significantly enhance the autonomous driving capabilities of vehicles, enabling better decision-making and improved driving safety in complex traffic environments. Moreover, all the test conditions are initially evaluated using simulations within a Python-based environment. These simulations are then followed by Simulink-based real-time model-in-the-loop (MIL) simulations, which validate the real-time capabilities of the proposed controller. This two-stage testing process ensures both the feasibility and practicality of the controller in dynamic and real-time scenarios.

3.1. CLF-CBF Based Optimization Controller

3.1.1. CLF Based Path Tracking Controller

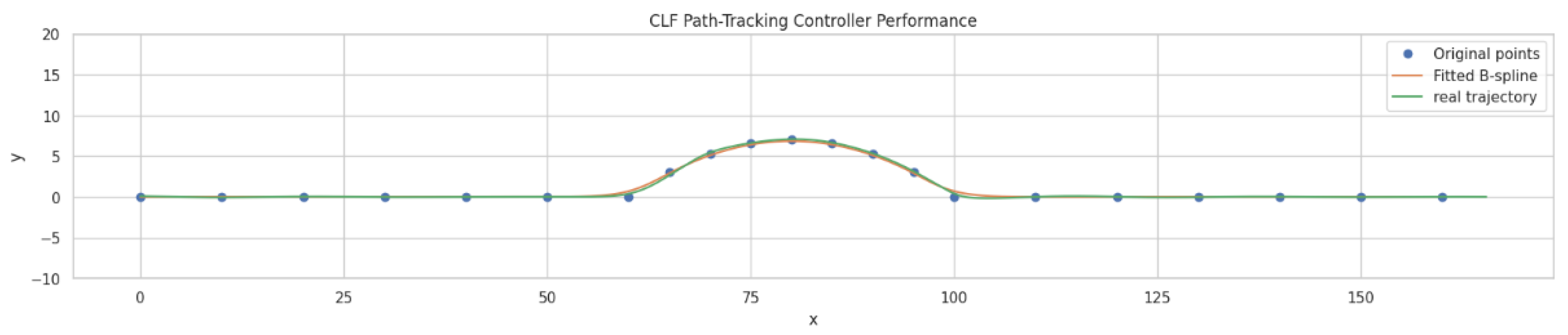

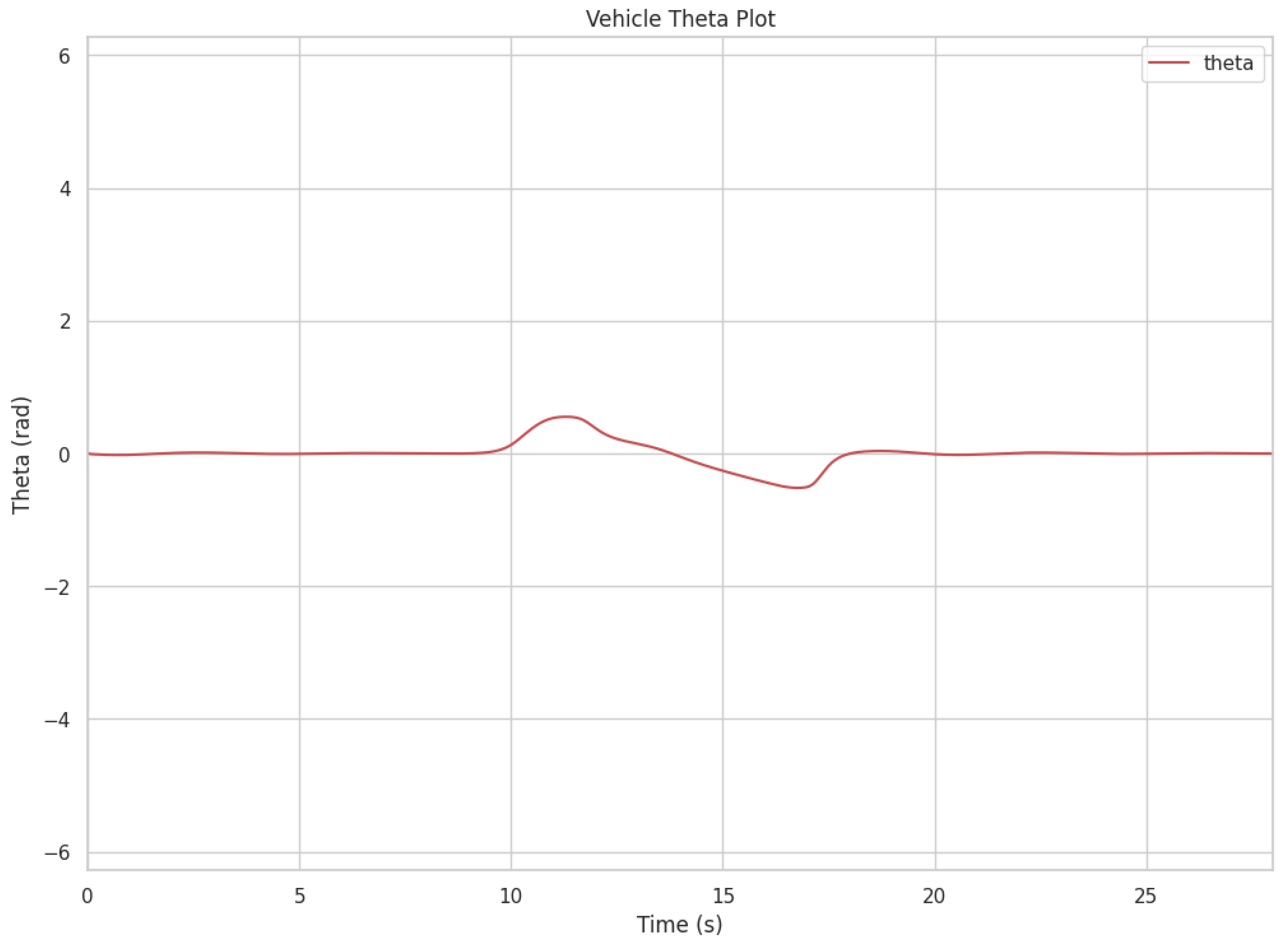

Figure 5 shows the real-time MIL simulation results of CLF based path tracking controller. The figure illustrates that the vehicle follows the desired path with high precision under most conditions, demonstrating the controller's effectiveness in path tracking tasks. However, a slight deviation from the original path is observed in regions with higher curvature, where tracking accuracy decreases marginally. This minor deviation could be attributed to the dynamic complexity introduced by the path's curvature, which challenges the controller's ability to maintain perfect alignment. Despite these small discrepancies, the overall performance of the CLF-based path-tracking controller is robust, showing its capability to handle real-time scenarios effectively while maintaining accurate path tracking. Further refinements or adjustments may help address the minor tracking offsets in curved sections to improve performance further.

Figure 6 shows the steering angle response

of the vehicle over time during the simulation. The plot indicates that the controller maintains stable steering behavior throughout the scenario.

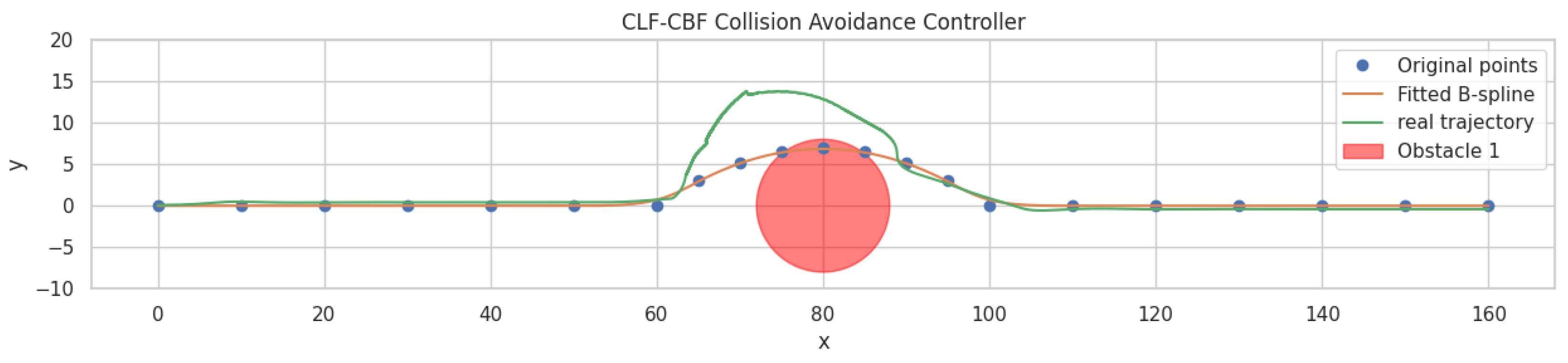

3.1.2. CLF-CBF Based Autonomous Driving Controller for Static Obstacle

Figure 7 illustrates the simulation results of the CLF-CBF-based autonomous driving controller in an environment with a static obstacle. The figure marks the original path waypoints in blue dot, the fitted B-spline trajectory in orange, and the vehicle's actual trajectory in green. The presence of an obstacle, marked as a red circle, requires the vehicle to deviate from the original path to avoid a collision. The simulation demonstrates that the controller successfully adjusts the vehicle's trajectory while maintaining safe navigation around the obstacle. This result highlights the controller's ability to combine path tracking with collision avoidance effectively. The smooth transitions and minimal deviation from the intended path illustrate the robustness of the CLF-CBF framework in handling static obstacles.

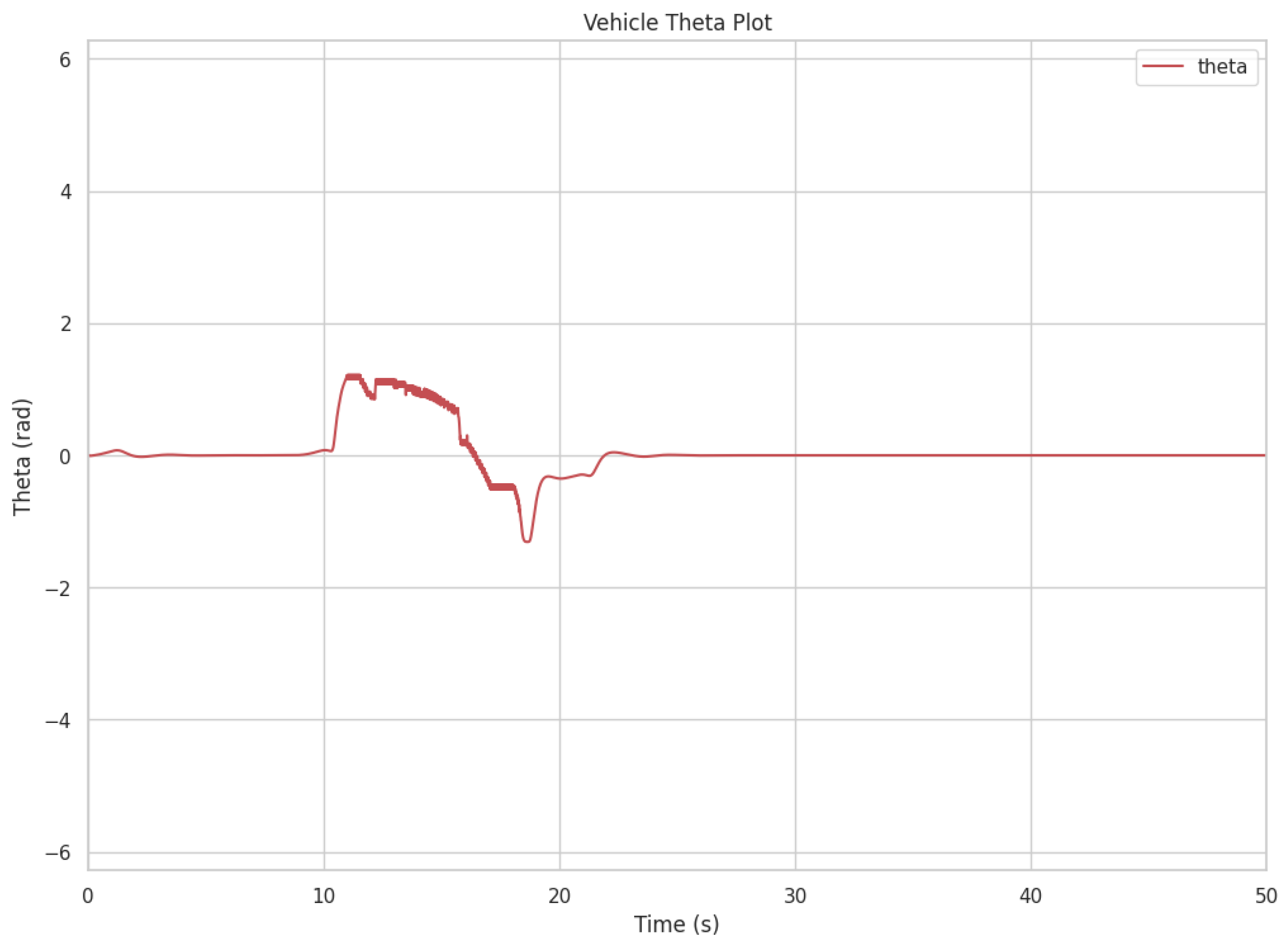

Figure 8 shows the steering angle response

of the vehicle over time during the simulation. The plot indicates that the controller maintains stable steering behavior throughout the scenario. During the initial phase, slight oscillations in the steering angle can be observed as the vehicle adjusts to follow the desired trajectory and avoid the static obstacle. These oscillations diminish over time, and the steering angle stabilizes as the vehicle returns to the planned path after bypassing the obstacle. The results demonstrate the controller's ability to make precise adjustments while ensuring stability and smooth operation, even in scenarios requiring significant maneuvering. The demo video link of this scenario is attached at the end of the paper.

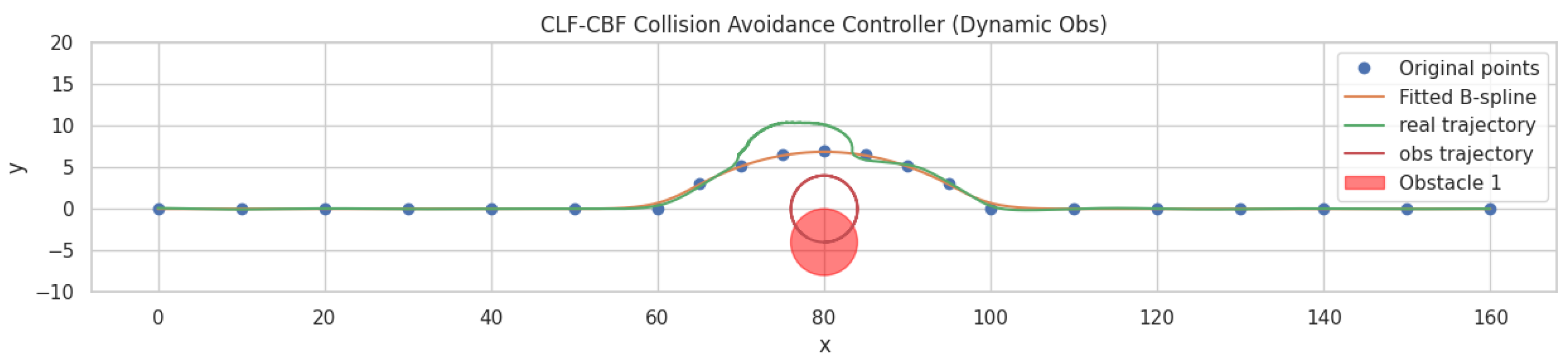

3.1.3. CLF-CBF Based Autonomous Driving Controller for Dynamic Obstacle

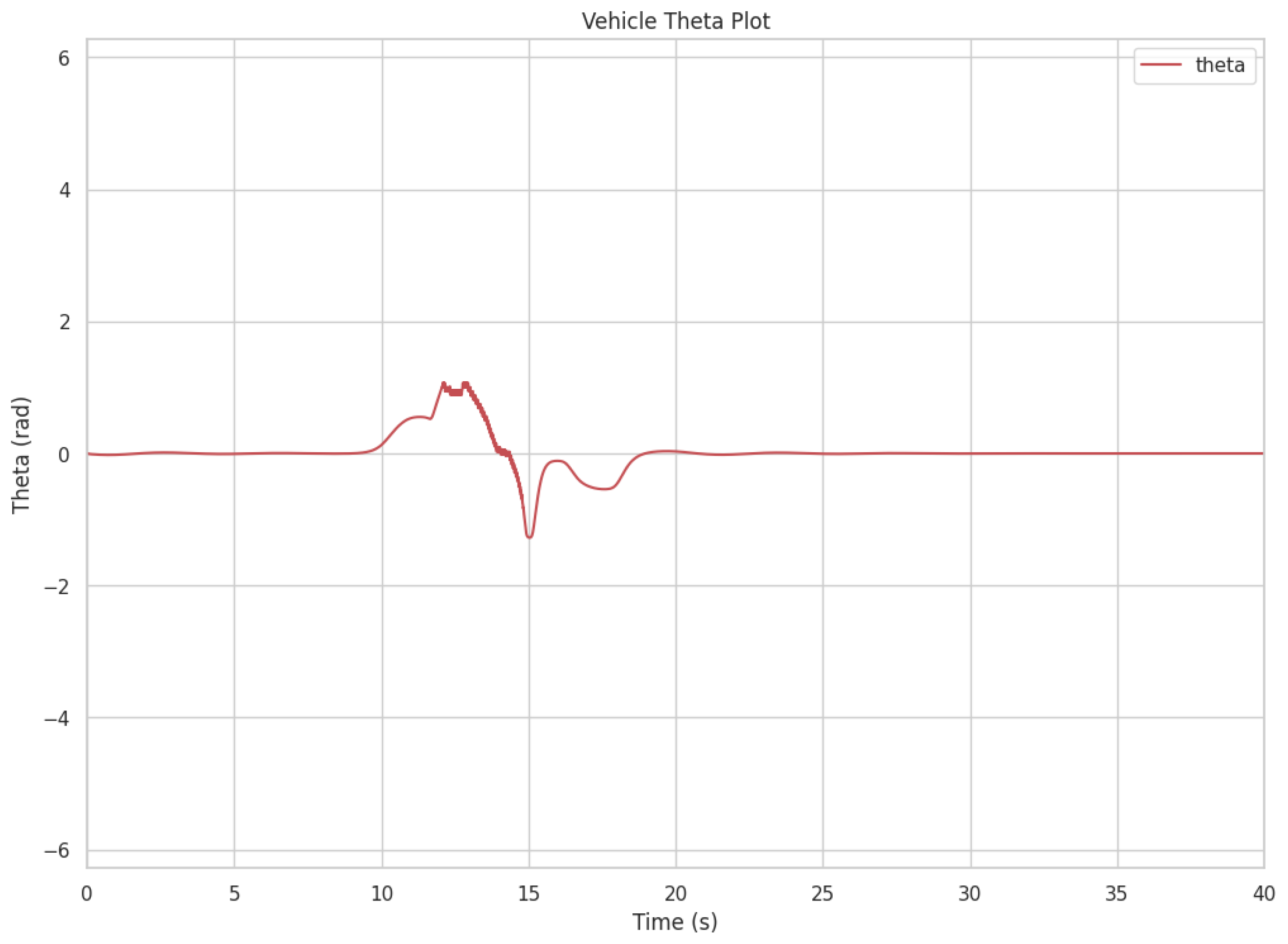

Figure 9 presents the simulation results of the CLF-CBF-based autonomous driving controller in an environment with dynamic obstacles. The original path waypoints are marked with blue dots, the fitted B-spline trajectory in orange, and the vehicle's actual trajectory in green. A dynamic obstacle, represented as a red circle, moves in a circular pattern. When the obstacle moves to the top and blocks a section of the pre-planned trajectory, the vehicle is required to deviate from the original path to avoid a collision. The simulation results demonstrate the controller's ability to adjust the vehicle's trajectory dynamically, ensuring safe navigation around the obstacle. The smooth transitions and minimal deviation from the intended path highlight the robustness of the CLF-CBF framework in handling dynamic obstacles effectively. Additionally,

Figure 10 illustrates the vehicle's steering angle response

over time during the simulation. The plot reveals stable steering behavior throughout the scenario, with minor oscillations in the middle phase as the vehicle adjusts to the desired trajectory while avoiding the obstacle. The demo video link of this scenario is attached at the end of the paper.

3.2. Hybrid DRL and CLF-CBF Based Controller

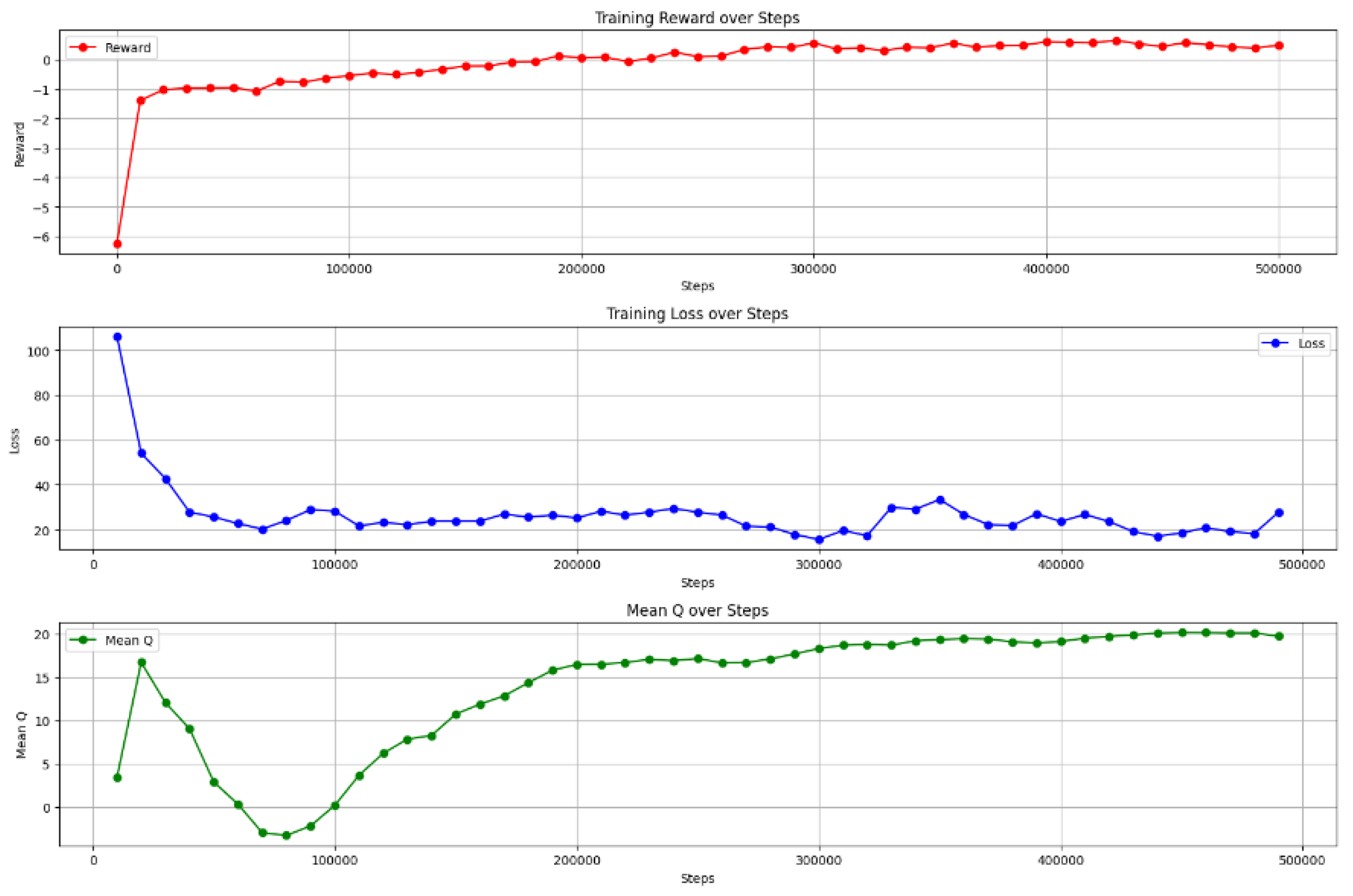

3.2.1. DRL High-Level Decision-Making Agent

Figure 11 demonstrates the training process of the proposed DRL high-level decision-making agent, which indicates significant improvements in the agent's performance over time. The reward plot shows a sharp increase during the early stages, starting from a highly negative value -6.2 and stabilizing near 0.5 after 300,000 steps, indicating that the agent quickly learned a basic policy and continued to refine it. The loss decreases rapidly from an initial high value 106 to a more stable range after 100,000 steps, with minor fluctuations throughout the end, which reflects that the agent can effectively minimize prediction error. Similarly, the mean Q-values show a notable increase, transitioning from early negative values to a stable value range around 20 after 100,000 steps. This demonstrates an improved confidence in action-value estimations. Together, these three plots indicate the agent's ability to effectively learn and optimize its policy, balancing exploration and exploitation to achieve improved performance as training progresses. The minor fluctuations in loss and reward suggest that further fine-tuning may still enhance stability and performance.

Figure 12 demonstrates an example of the proposed DRL high-level decision-making agent. The blue line indicates the trajectory of proposed agent, and the red line indicates the motion of obstacles. It is shown that the agent can navigate through the grid while avoiding obstacles. The agent begins from the starting position on the left and successfully reaches the goal area on the right. The smooth progression of the blue line highlights the agent's ability to make efficient decisions to circumvent the moving obstacles while maintaining a clear path toward the target. In contrast, the red trajectory depicts the dynamic movement of obstacles, adding complexity to the environment. This example demonstrates the agent’s effective decision-making capabilities in handling high-level planning and real-time obstacle avoidance. The demo video link of other scenarios is attached at the end of the paper.

3.2.2. Hybrid DRL and CLF-CBF Controller

Figure 13 demonstrates the trajectory generated by the proposed DRL high-level decision-making agent. The blue line indicates the real trajectory which can be tracked by the vehicle. Compared to previous results, the rough sketch generated by the DRL high-level agent is successfully converted into a control feasible path that can be tracked by the vehicle. Combined with CLF-CBF-QP-based control, the autonomous vehicle successfully follows this path, navigating from the starting point to the endpoint without colliding with obstacles. Overall, the proposed DRL high-level controller demonstrate its capability to find collision-free and optimal paths which can be further improved by increase training episodes and fine tuning the hyperparameter.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

In this study, we proposed a hybrid control framework by integrating CLF, CBF, and DRL to achieve safe and efficient autonomous driving. The results from simulation tests demonstrate that the proposed approach effectively combines the stability and safety guarantees of optimization-based methods with the adaptability and decision-making capabilities of machine learning techniques. The unicycle vehicle dynamic model provided a simplified yet functional foundation for designing and evaluating control strategies.

The CLF-CBF-QP approach exhibited robust performance in different traffic scenarios with obstacles, achieving precise path tracking while maintaining collision avoidance. The incorporation of a DRL-based high-level decision-making agent further enhanced the system's capability to navigate complex traffic environments, ensuring flexibility and robustness in decision-making. Moreover, the real-time performance demonstrated in MIL simulations underscores the potential applicability of the proposed framework in real-world autonomous driving systems.

Despite the advancements presented in this paper, the proposed hybrid controller has several limitations that require further exploration in future work. First, the unicycle vehicle model used in this study is an oversimplification and does not fully capture the complexities of real-world vehicle dynamics. To enhance the controller’s performance and enable its application in real-world scenarios, a more realistic vehicle dynamic model should be adopted in the future. Additionally, the design of CLF and CBF is heavily dependent on the specific vehicle model. For more complex vehicle dynamics, designing valid CLF and CBF can become challenging. Future work should explore advanced methodologies, such as integrating neural networks as CLF and CBF for more realistic vehicle models.

Moreover, the current testing pipeline is insufficient to comprehensively evaluate the controller's capabilities. In this work, the control strategies were only tested using MIL simulations. To further validate the controller’s performance, hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing should be conducted in future studies. Afterward, rigorous testing using the vehicle-in-virtual-environment (VVE) framework [

33], as well as real-world road tests, should be implemented to ensure the robustness, safety, and reliability of the proposed controller in practical scenarios. Sensing and perception of the obstacles was outside the scope of this work and can be treated in future work which can also include vehicle to vehicle communication [

34]. These future steps will be useful to advancing the hybrid controller for deployment in autonomous driving systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C., F.Z. and B.A.-G.; methodology, H.C., F.Z. and B.A.-G.; software, H.C. and F.Z.; validation, H.C. and F.Z.; formal analysis, H.C. and F.Z.; investigation, H.C. and F.Z.; resources, B.A.-G.; data curation, H.C. and F.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C. and F.Z.; writing—review and editing, B.A.-G.; visualization, H.C. and F.Z.; supervision, B.A.-G.; project administration, B.A.-G.; funding acquisition, B.A.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is funded in part by Carnegie Mellon University’s Safety21 National University Transportation Center, which is sponsored by the US Department of Transportation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Automated Driving Lab at the Ohio State University.

Demo Video Link

CLF-CBF for static obstacle, CLF-CBF for dynamic obstacle, DRL high-level.

References

- B. Wen et al, “Localization and Perception for Control and Decision Making of a Low Speed Autonomous Shuttle in a Campus Pilot Deployment,” Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Gelbal, B. A. Guvenc, and L. Guvenc, “SmartShuttle: a unified, scalable and replicable approach to connected and automated driving in a smart city,” in Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Science of Smart City Operations and Platforms Engineering, in SCOPE ’17. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2017, pp. 57–62. [CrossRef]

- L. Guvenc, B. A. Guvenc and M. T. Emirler, "Connected and Autonomous Vehicles," in Internet of Things and Data Analytics Handbook, John Wiley & Sons, 2017, pp. 581-595.

- L. Guvenc et al, Autonomous Road Vehicle Path Planning and Tracking Control., Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2022.

- E. Lowe and L. Guvenc, "Autonomous Vehicle Emergency Obstacle Avoidance Maneuver Framework at Highway Speed," Electronics, 12(23), 4765., vol. 12, no. 23, p. 4765, 2023.

- M. T. Emirler, H. Wang, and B. Guvenc, “Socially Acceptable Collision Avoidance System for Vulnerable Road Users,” IFAC-Pap., vol. 49, pp. 436–441, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Ames, J. W. Grizzle, and P. Tabuada, “Control barrier function based quadratic programs with application to adaptive cruise control,” in 53rd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Dec. 2014, pp. 6271–6278. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Ames, X. Xu, J. W. Grizzle, and P. Tabuada, “Control Barrier Function Based Quadratic Programs for Safety Critical Systems,” IEEE Trans. Autom. Control, vol. 62, no. 8, pp. 3861–3876, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Ames, S. Coogan, M. Egerstedt, G. Notomista, K. Sreenath, and P. Tabuada, “Control Barrier Functions: Theory and Applications,” in 2019 18th European Control Conference (ECC), Jun. 2019, pp. 3420–3431. [CrossRef]

- S. He, J. Zeng, B. Zhang, and K. Sreenath, “Rule-Based Safety-Critical Control Design using Control Barrier Functions with Application to Autonomous Lane Change,” Mar. 23, 2021, arXiv: arXiv:2103.12382. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, A. D. Ames, and M. Egerstedt, “Safety Barrier Certificates for Collisions-Free Multirobot Systems,” IEEE Trans. Robot., vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 661–674, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Liu, I. Kolmanovsky, H. E. Tseng, S. Huang, D. Filev, and A. Girard, “Potential Game-Based Decision-Making for Autonomous Driving,” Nov. 09, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2201.06157. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Reis, G. A. Andrade, and A. P. Aguiar, “Safe Autonomous Multi-vehicle Navigation Using Path Following Control and Spline-Based Barrier Functions,” in Robot 2023: Sixth Iberian Robotics Conference, L. Marques, C. Santos, J. L. Lima, D. Tardioli, and M. Ferre, Eds., Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024, pp. 297–309. [CrossRef]

- M. Desai and A. Ghaffari, “CLF-CBF Based Quadratic Programs for Safe Motion Control of Nonholonomic Mobile Robots in Presence of Moving Obstacles,” in 2022 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM), Jul. 2022, pp. 16–21. [CrossRef]

- K. Long, Y. Yi, J. Cortes, and N. Atanasov, “Distributionally Robust Lyapunov Function Search Under Uncertainty,” Jul. 11, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2212.01554. [CrossRef]

- Y.-C. Chang, N. Roohi, and S. Gao, “Neural Lyapunov Control,” Sep. 22, 2022, arXiv: arXiv:2005.00611. [CrossRef]

- W. B. Knox, A. Allievi, H. Banzhaf, F. Schmitt, and P. Stone, “Reward (Mis)design for autonomous driving,” Artif. Intell., vol. 316, p. 103829, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. R. Kiran et al., “Deep Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Driving: A Survey,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 4909–4926, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Ye, S. Zhang, P. Wang, and C.-Y. Chan, “A Survey of Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithms for Motion Planning and Control of Autonomous Vehicles,” in 2021 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Jul. 2021, pp. 1073–1080. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhu and H. Zhao, “A Survey of Deep RL and IL for Autonomous Driving Policy Learning,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 23, no. 9, pp. 14043–14065, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, A. Tota, B. Aksun-Guvenc, and L. Guvenc, “Real time implementation of socially acceptable collision avoidance of a low speed autonomous shuttle using the elastic band method,” Mechatronics, vol. 50, pp. 341–355, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Lu, R. Xu, Z. Li, B. Wang, and Z. Zhao, “Lunar Rover Collaborated Path Planning with Artificial Potential Field-Based Heuristic on Deep Reinforcement Learning,” Aerospace, vol. 11, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Morsali, E. Frisk, and J. Åslund, “Spatio-Temporal Planning in Multi-Vehicle Scenarios for Autonomous Vehicle Using Support Vector Machines,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh., vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 611–621, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhu, “Path Planning and Robust Control of Autonomous Vehicles,” Ph.D., The Ohio State University, United States -- Ohio, 2020. Accessed: Oct. 24, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2612075055/abstract/73982D6BAE3D419APQ/1.

- G. Chen et al., “Emergency Obstacle Avoidance Trajectory Planning Method of Intelligent Vehicles Based on Improved Hybrid A*,” SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 10-08-01–0001, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Kendall et al., “Learning to Drive in a Day,” Sep. 11, 2018, arXiv: arXiv:1807.00412. [CrossRef]

- E. Yurtsever, L. Capito, K. Redmill, and U. Ozguner, “Integrating Deep Reinforcement Learning with Model-based Path Planners for Automated Driving,” May 19, 2020, arXiv: arXiv:2002.00434. Accessed: Nov. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2002.00434.

- L. Dinh, P. T. A. Quang, and J. Leguay, “Towards Safe Load Balancing based on Control Barrier Functions and Deep Reinforcement Learning,” Jan. 10, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2401.05525. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Ashwin and R. Naveen Raj, “Deep reinforcement learning for autonomous vehicles: lane keep and overtaking scenarios with collision avoidance,” Int. J. Inf. Technol., vol. 15, no. 7, pp. 3541–3553, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. J. M. Muzahid, S. F. Kamarulzaman, Md. A. Rahman, and A. H. Alenezi, “Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Driving Strategy for Avoidance of Chain Collisions and Its Safety Efficiency Analysis in Autonomous Vehicles,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 43303–43319, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Emuna, A. Borowsky, and A. Biess, “Deep Reinforcement Learning for Human-Like Driving Policies in Collision Avoidance Tasks of Self-Driving Cars,” Jun. 19, 2020, arXiv: arXiv:2006.04218. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen et al, “Deep-Reinforcement-Learning-Based Collision Avoidance of Autonomous Driving System for Vulnerable Road User Safety,” Electronics, vol. 13, no. 10, Art. no. 10, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Cao et al, “Vehicle-in-Virtual-Environment (VVE) Method for Autonomous Driving System Development, Evaluation and Demonstration,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 11, Art. no. 11, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- O. Kavas-Torris et al, “V2X Communication between Connected and Automated Vehicles (CAVs) and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs),” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 22, Art. no. 22, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).