3.1. Vehicle Following and Lane Changing Model

In the Internet of Vehicles environment, autonomous vehicle, equipped with laser radar, infrared video ranging and other on-board sensing equipment, can achieve braking control with shorter response time by virtue of the information interaction and collaboration capabilities of the Internet of Vehicles, so as to obtain higher precision and better numerical safety distance threshold. For manually driven vehicles, based on the differences in driver driving styles, they can be divided into three categories: aggressive, conservative, and cautious. Therefore, the driver adventure coefficient

a is introduced. The acceleration of the preceding vehicle can reflect its motion state trend. When the current vehicle is decelerating, the following vehicle needs to reserve a larger safety distance. Based on this, the acceleration influence factor

b of the preceding vehicle is introduced to improve and optimize the Gipps safety distance following model. The optimized model is shown in equation (1).

In the formula: represents the minimum safe following distance of vehicle n; represents the speed of vehicle n at time t; represents the reaction time required for vehicle n to apply emergency braking; represents the maximum deceleration of vehicle n, and represents the acceleration of the preceding vehicle;For autonomous vehicles, the risk factor can be set as a fixed value ; The risk factor of manually driven vehicles ; Sensitivity coefficient , when , this term was positive, increasing the safety distance; when , this item was negative and the distance could be appropriately reduced.

After considering the acceleration of the preceding vehicle, the velocity of the preceding vehicle is corrected to the predicted value, as shown in equation (2):

In the formula: indicate the predicted speed of the preceding vehicle.

Enter the formula for safe speed, as shown in equation (3):

In the formula: represents the safe speed at which vehicle n does not collide with the preceding vehicle at time t; Indicate the distance between vehicle n and the preceding vehicle at time t.

The above artificial driving model belongs to the ideal physical model. In actual driving scenarios, when in a high-density traffic environment, the psychological pressure of drivers tends to increase, which may lead to unnecessary deceleration behaviors without the interference of the preceding vehicle (such as unconsciously releasing the accelerator pedal). To accurately characterize the probability characteristics of the random slowing behavior, this paper introduces the Richards growth curve model from the field of biology and constructs a functional mapping relationship between road traffic density and driver random slowing probability. Through this model, it is possible to simulate the dynamic process where the psychological burden on drivers gradually increases as road traffic density continues to increase, ultimately leading to a corresponding increase in the probability of implementing deceleration operations during the driving process. This is more in line with the complex characteristics of actual human driving behavior. Set the initial value (basic slowing tendency under low density) to 0.2, the maximum slowing probability

A under high density to 0.4, the growth efficiency (sensitivity of density to pressure)

K to 0.05, the metabolic rate (improvement of psychological tolerance after high pressure adaptation)

m to 0.95, and the random slowing probability curve equation to equation (4):

B is the theoretical capacity of a road, which is the maximum number of vehicles that a unit length (1 km) of road can carry under ideal conditions; represents the density of road traffic flow, which characterizes the distribution of vehicles within a unit length of the road; N is the actual total number of vehicles on the road; L is the length of the road in kilometers. In actual traffic scenarios, as the traffic density continues to increase, the psychological burden on drivers exhibits dynamic changes: in the initial stage, the increase in traffic density increases the complexity of the driving environment, and the psychological burden on drivers accelerates and accumulates with the increase in density, directly manifested as the growth rate of the probability of slowing down with the machine gradually increasing (slowing down behaviors such as unnecessary deceleration, delayed operation response, etc.); When the traffic density exceeds a certain critical threshold (i.e. the inflection point of the curve), due to the high stress psychological state of the driver, the marginal stimulus effect of increasing traffic density on their psychology gradually decreases. At this time, the growth rate of the random slowing probability changes from increasing to decreasing, and finally approaches the theoretical probability upper limit of 0.4 asymptotically.

The lane change behavior for mixed traffic flow can only be triggered when the lane change conditions are met. Consider free lane changing behavior. When the speed on this lane is insufficient and the safety distance between the front and rear is within the constraint conditions, lane changing can be carried out.

The triggering condition is shown in equation (5):

In the formula: indicate the speed of the preceding vehicle in this lane, indicate the current speed of the vehicle, representing the speed ratio threshold (triggering lane change demand), the value is 0.85.

The forward safety distance constraint is shown in equation (6):

In the formula: indicate the distance to the vehicle in front of this lane; indicating forward safe time interval, 1.8 (aggressive)~2.2 (conservative); indicates standard vehicle length, ranging from 4.5 (sedan) to 5 (SUV).

The backward safety distance constraint is shown in equation (7):

In the formula: represents the distance to the vehicle behind the target lane; indicate the safe time interval for the rear vehicle, ranging from 1.2 (aggressive) to 1.8 (conservative); representing the driver's risk preference factor, ranging from 0.8 (aggressive) to 1.2 (conservative); indicate the maximum braking deceleration of the rear vehicle; indicates the speed of the vehicle behind the target lane.

The comprehensive decision function for lane changing is shown in equation (8):

Where: ,。

3.2. Hybrid Fleet Energy Consumption Model

Regarding the energy consumption of hybrid fleets, considering that the existing vehicle types mainly include pure fuel vehicles, pure electric vehicles, and hybrid vehicles, and hybrid vehicles also include plug-in hybrid and extended range hybrid, it is possible to consider setting a power type coefficient a to divide hybrid vehicles into a combination of pure fuel vehicles and pure electric vehicles. The energy consumption of electric vehicles is mainly related to the power of the motor, while that of fuel vehicles is affected by the thermal efficiency of the engine. In order to facilitate the analysis of the energy consumption of the fleet from the same dimension, this article represents the energy consumption of both electric vehicles and fuel vehicles as kj. Specifically, in the energy consumption calculation of electric vehicles, the energy unit of the battery is converted from kw·h to kj units of energy value; In the energy consumption calculation of fuel vehicles, the calorific value of the consumed fuel is converted into an energy value in units of kj, assuming 1kw=3600kj.

Existing research usually establishes energy consumption models for AV and HDV separately, which leads to the need to calculate and stack different vehicle models for hybrid fleets, making the calculations complex and difficult to optimize collaborative strategies. For the convenience of calculation, a unified energy consumption model is established by separately modeling the acceleration/uniform speed (a ≥ 0) and deceleration (a < 0) operating conditions.

Step 1: In the acceleration/uniform speed stage, the theoretical basis adopted by the electric part is: instantaneous power of the electric vehicle=base load + driving resistance power + acceleration power,

Driving resistance power

(rolling resistance + air resistance),

is simplified to reduce the risk of overfitting. The acceleration power

reflects the nonlinear variation of motor efficiency with load (experimental calibration shows that the square term is better than the linear term). The specific expression is equation (9):

In the formula: represents the basic power consumption of vehicle electronic devices, air conditioning, etc., set to 0.05kw; is the linear term of speed, represents the energy consumption to overcome rolling resistance (tire deformation, transmission friction), set to 0.003; is the square term of speed, representing the energy consumption of customer service air resistance, set to 1.8e-4; is the square term of acceleration, representing the energy cost of kinetic energy changes (additional load on the motor/engine), set to 0.0012.

The basic theory used in the fuel section is that the fuel consumption rate is related to the effective fuel consumption rate (BSFC) of the engine, which is exponentially related to the speed (

v) and load (

a). The specific expression is equation (10):

In the formula: represents the basic fuel consumption of fuel vehicles at idle speed, set to -1.85; representing the relationship between combustion efficiency and load, affected by speed, set to 0.04; represents the non-linear relationship between throttle opening and fuel injection quantity, influenced by acceleration,is set to 0.08;

Step 2: During the deceleration phase, the basic theory used for the electric part is: The regenerative braking power is brake torque × speed. The experiment shows that torque is correlated with deceleration to the power of 0.8 (nonlinear energy recovery efficiency). The specific expression is equation (11):

In the formula: represents the regenerative braking rate of electric vehicles, represents the proportion of recovered kinetic energy, and the higher the speed, the greater the motor reaction force, and the higher the proportion of kinetic energy recovered.

The basic theory used in the fuel section is that the fuel injection amount during deceleration of a fuel vehicle is approximately equal to the idle fuel consumption (only maintaining engine operation), which is weakly correlated with speed (intake compensation). The specific expression is equation (12):

Step 3: Substitute the power type coefficient

a and obtain the unified form of the energy consumption model for the hybrid fleet as equation (13):

Establishing a unified energy consumption model for hybrid fleets avoids the need for separately calculating energy consumption by vehicle type and solves the problem of complex calculations and difficult collaborative optimization strategies.

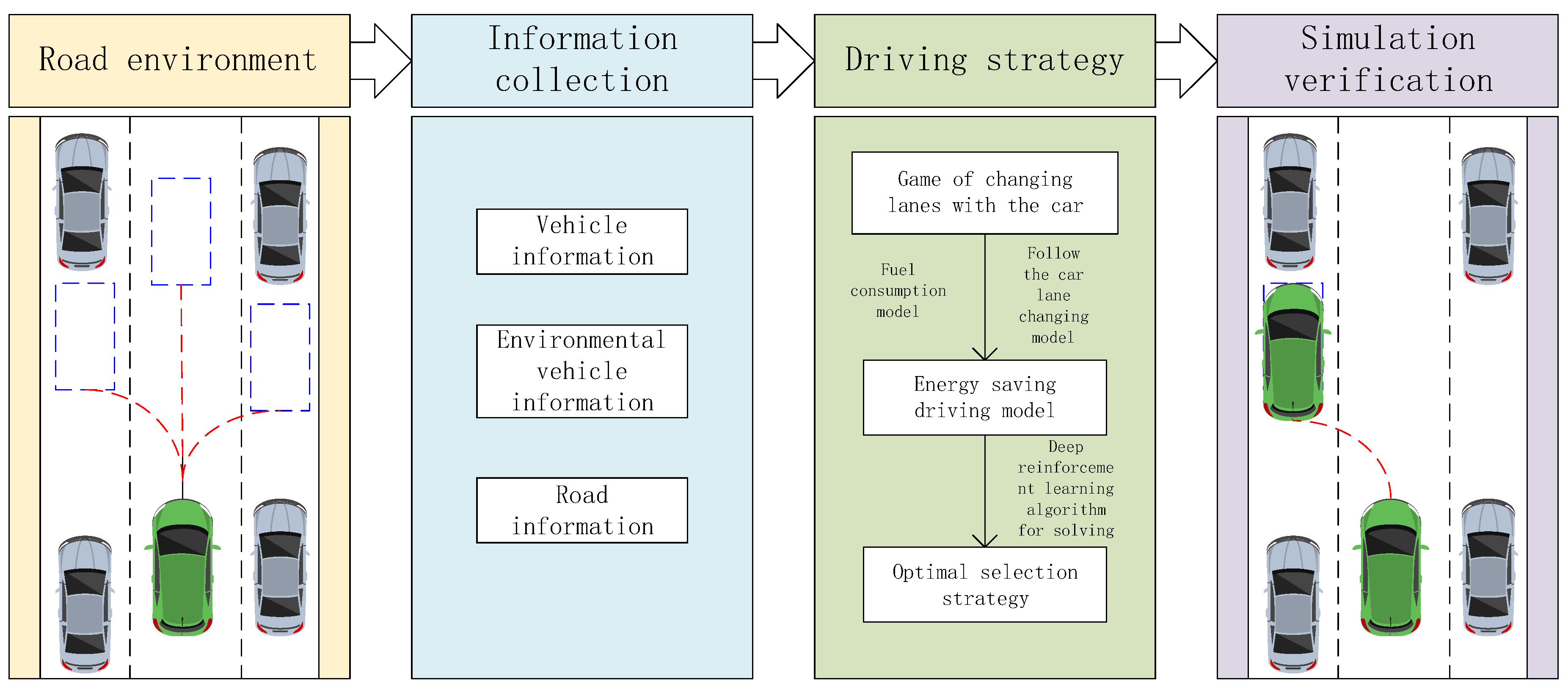

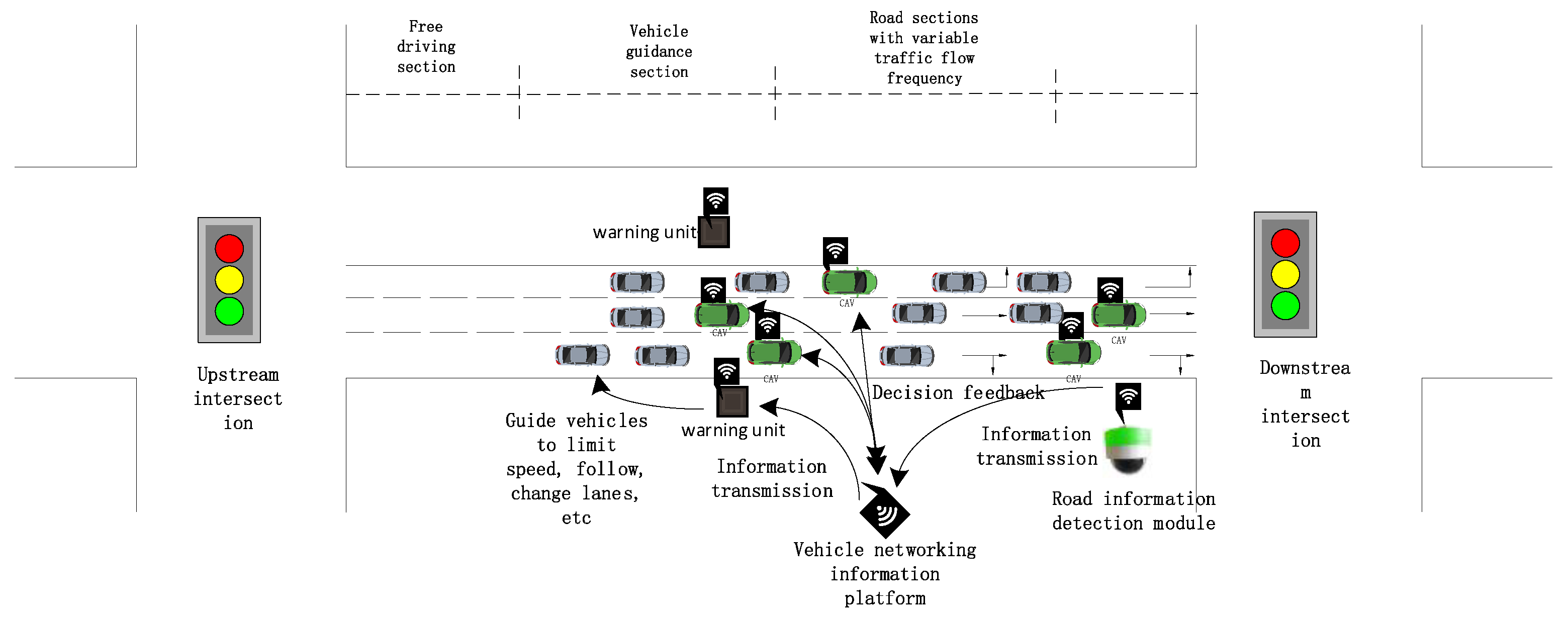

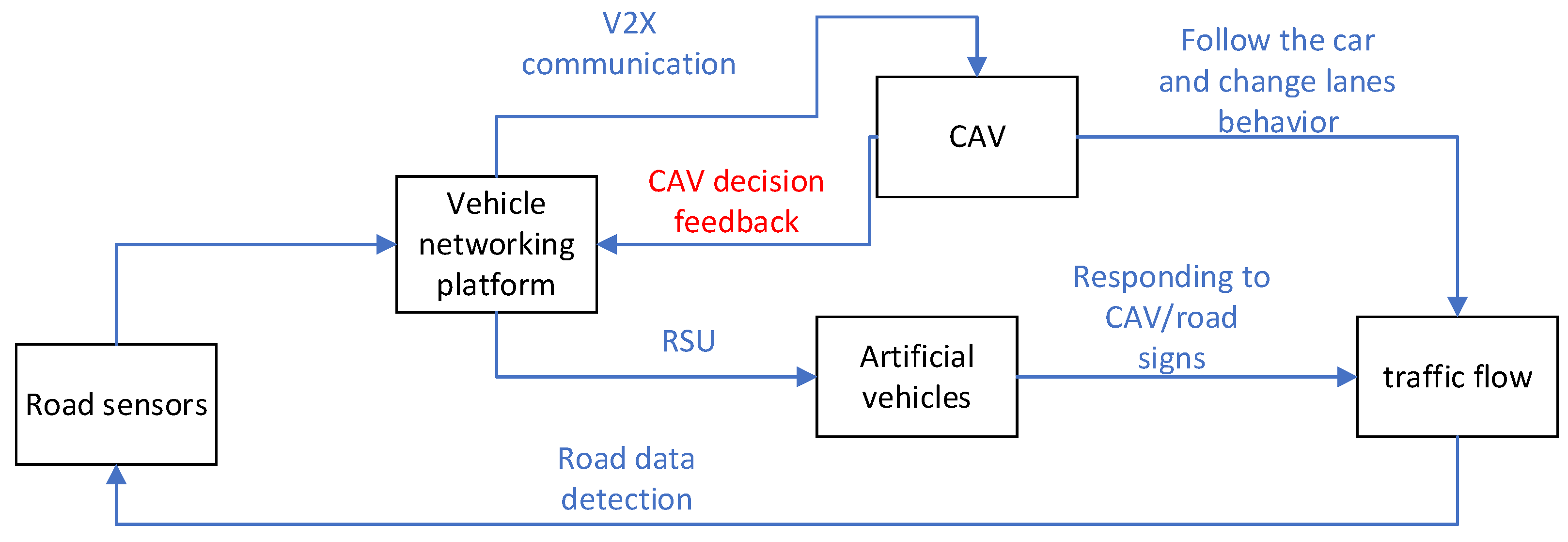

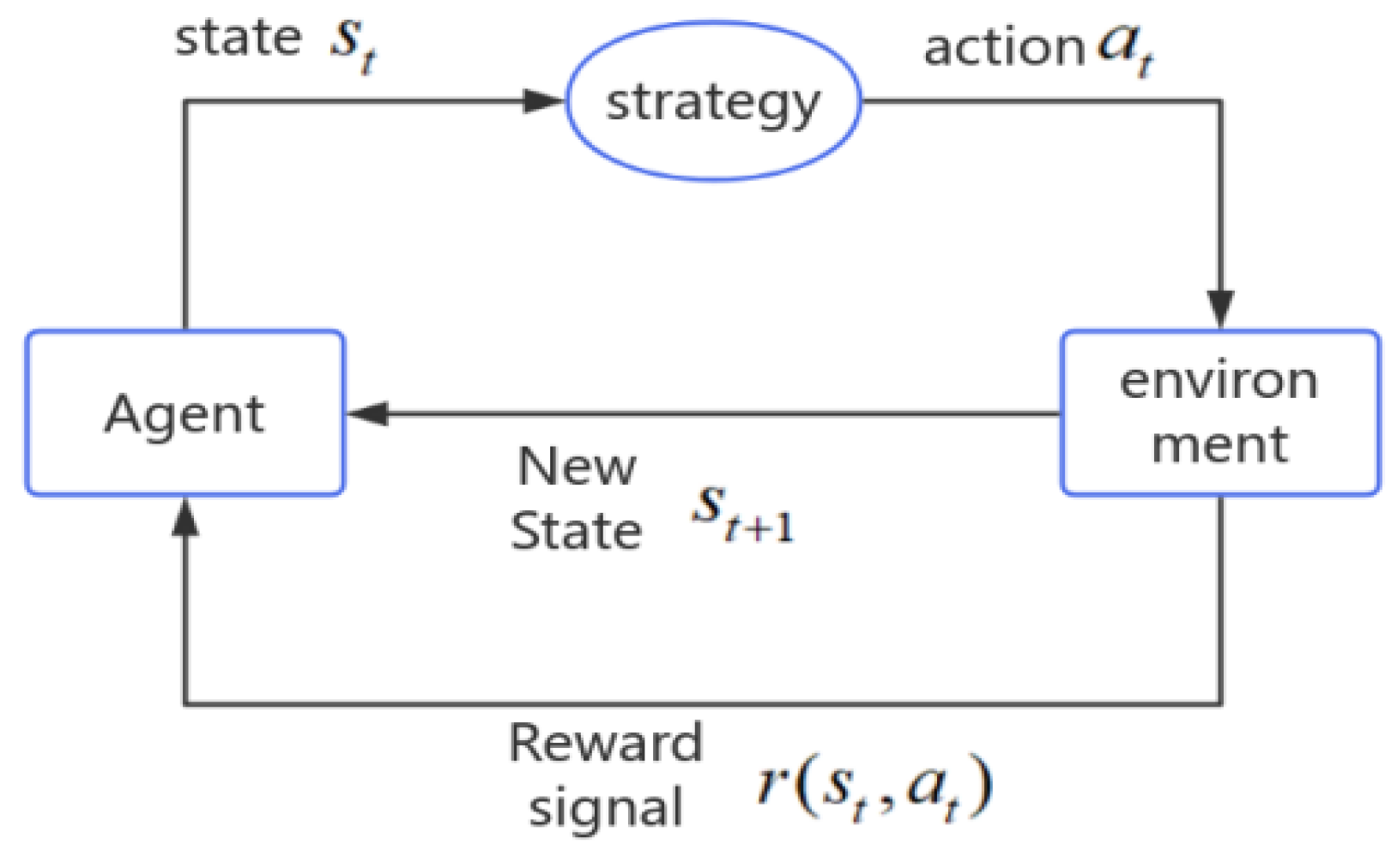

3.3. Energy Saving Driving Model for Hybrid Fleet

To find the optimal energy-saving driving strategy for road sections with variable traffic flow frequency, the energy-saving driving strategy can be divided into two types of implementation paths based on the traffic status (distribution of vehicles in the lane) of the nearby intersection obtained in the vehicle networking environment. When the traffic scene features perceive that the traffic flow ahead is in a steady state and the intersection signal light is green, guide the vehicle to follow the vehicle ahead in a stable mode within the vehicle guidance area; When a waiting queue vehicle is detected ahead and the adjacent lane belongs to the target available lane, guide the vehicle to perform a lane change operation within the vehicle guidance area. The above two scenarios were both carried out under the condition of satisfying the car following and lane changing model, ultimately resulting in a driving strategy that guides the safe and energy-saving operation of the vehicle.

Based on dynamic programming theory, the road driving space is subjected to spatially uniform discretization, and then deconstructed into a continuous multi-stage decision space. At the same time, the driving state of the vehicle is divided into three dimensions: distance, speed, and relative state. Based on the characteristics of actual driving scenarios, the safety distance model is extended to adapt to the constraints of vehicle driving behavior. Among them, the definition of moderate following distance is that the current following distance can meet the safety requirements for the following vehicle to follow at a constant speed. Therefore, the extended formula for calculating the relative following distance is equations (14) – (15):

In the formula: is the moderate following distance of vehicle n; is the longer following distance of vehicle n; is the following speed of vehicle n at time t; is the maximum acceleration of vehicle n; is the maximum deceleration of vehicle n.

Segmented solution is applied to the driving space ahead. Assuming the straight space length of the driving space ahead is

L, the driving space is divided into

n sub intervals, each with a length of

. Generally, the value of

is small, and the running speed within the interval can be simplified to take the average of the end of stage speeds. For vehicles that maintain a following state, the calculation formula for the running time of the subinterval can be obtained as shown in equation (16):

For vehicles engaged in lane changing behavior, let the lane width be

,the approximate length traveled by the vehicle is

,At this time, the running time of the subinterval is shown in equation (17):

Assuming constant acceleration within the subinterval, combined with the energy consumption model calculation formula, the energy consumption calculation formula for each stage of state transition is shown in equation (18):

In the formula: is the total energy consumption of stage k; is the instantaneous energy consumption of vehicles; is the running time for phase k.