1. Introduction

1.1. The Place of Microwave Heating in Ceramic Firing Methods

Since their invention after World War II, microwave heating and cooking have become a universal tool, widely adopted in homes and catering. This led to the mass production of low-cost, easy-to-use domestic appliances [

1]. Industrially, the technology is also extensively used for low and medium-temperature applications like drying and sterilisation [

2,

3,

4].

At higher temperatures, microwave energy has proven effective for tasks such as reducing iron ore [

5,

6,

7]. For sintering ceramic materials and oxides, microwave heating offers clear advantages over traditional methods. It is a well-established fact that it improves diffusion kinetics and densification, allowing these processes to be completed at a much faster rate and at a lower temperature than conventional sintering [

8,

9,

10]. This combination of faster heating and improved densification dramatically divides processing time by an or two order of magnitude [

10,

11] and reduces significantly energy consumption [

8,

9].

Consequently, high-temperature microwave sintering has been developed for manufacturing high-quality technical ceramics [

10,

11,

12] with significant added value for advanced applications in the medical, space, and military sectors. In the consumer sector, however, high-temperature microwave applications are rare. They are almost exclusively limited to dental applications for producing small prostheses (zirconia) in very small kilns (1/4–1/2 liter). For utilitarian or artisanal ceramics, which represent a large market, there is currently no available equipment that uses only microwave energy.

Despite this, a large number of laboratory studies over the last 30 years have demonstrated the clear benefits of microwave heating for both test specimens and standard-sized objects [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Nevertheless, the technologies used for firing utilitarian ceramics remain based on traditional kilns heated by an external source—often powered by fossil fuels. These energy-intensive and time-consuming techniques immobilise equipment and human resources.

This surprising conservatism in heating techniques for artisanal ceramics, especially when faced with the extraordinary potential of microwave technology in terms of energy, time, and quality gains, has been noted by many authors. One interpretation [

22] is the difficulty of modelling wave-matter interactions, particularly for large objects. However, experimental and theoretical work from the last ten years has consistently shown that it is possible to successfully manufacture ceramic tableware using microwave heating [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

23].

1.2. Microwave Heating: Principles and Current State of Knowledge

Microwave heating is fundamentally different from traditional heating processes. In conventional methods, an external source (like oil, gas, or electrical resistance) transfers energy to a material primarily through radiation and conduction. In contrast, microwave heating generates heat internally within the material itself. This occurs at an atomic level as microwaves interact with the material’s molecules.

When a material containing polar molecules is exposed to microwave energy, the electromagnetic radiation causes these molecules to rotate, which generates heat. This phenomenon is known as dielectric heating. A polar molecule, such as water, has a distinct positive and negative charge, giving it an electric dipole moment.

A material’s ability to self-heat when exposed to microwaves is referred to as its ability to couple with or suscept to the electromagnetic radiation. Conversely, a material that allows microwaves to pass through without heating is transparent, while one that blocks them is reflecting. A ceramic material that undergoes dielectric heating is called a susceptor.

Achieving high-temperature conditions for sintering materials using direct microwave heating presents several challenges. The most common applicators, which operate at low frequencies (2.45 GHz), often struggle to efficiently couple with many materials at room temperature, making initial heating difficult. Ceramics, with their non-homogeneous properties (such as dielectric permittivity and losses), complicate this interaction. For large ceramic pieces, uneven heating can lead to thermal gradients, causing cracks. Additionally, rapid heating can induce thermal stresses, porosity, and localised hot spots, which may lead to a catastrophic temperature runaway [

24,

25].

To overcome these issues, hybrid heating techniques have been developed. These methods combine direct microwave heating with a secondary heat source, often a susceptor material with high dielectric loss at low temperatures. A susceptor absorbs microwave energy and quickly reaches high temperatures, transferring heat to the ceramic sample through conventional mechanisms like radiation. Once the sample reaches a high enough temperature, its own dielectric loss increases, allowing it to begin absorbing microwaves and heating internally.

This hybrid approach, also known as “susceptor-assisted microwave heating,” offers a dual heating mechanism: the susceptor heats the material from the surface, while the microwaves heat it from the center. This results in more uniform heating compared to direct microwave heating, where the center typically becomes hotter than the surface. The reduced heat loss from the surface, aided by the susceptor, further contributes to maintaining thermal homogeneity during the process [

10,

11,

22,

26]. In practice, this involves placing various forms of susceptors (tubes, plates, rods, etc.) near the piece to be heated [

26,

27].

Microwave heating cavities are metal enclosures designed to maximise energy transfer efficiency by containing and reflecting microwaves to create standing waves. These cavities can be multi-mode or single-mode, which influences the distribution of the electromagnetic field. Multi-mode cavities, such as those in a standard microwave oven, allow waves to propagate freely throughout a large volume, while single-mode cavities constrain the field, making them more efficient for small samples and precise control.

The electric field distribution within a multi-mode cavity is complex, depending on the material’s geometry, the microwave emission characteristics, and the material’s evolving dielectric properties [

25]. Non-uniform field patterns and hot spots caused by a static applicator design can lead to uneven heating and thermal runaway. To improve heating uniformity and efficiency, multi-mode applicators often use mode stirrers—mobile metallic elements that modify the electromagnetic field—and rotating turntables to change the sample’s position within the cavity [

28,

29].

Despite the challenges, a major advantage of microwave heating is the spectacular time savings, which can be 5 to 10 times faster than conventional heating for achieving comparable or even superior product quality [

10,

14,

18,

26].

Since the late 1980s, when microwave ovens were first used for ceramics [

9], extensive research has demonstrated the benefits of this heating method. The work of Tiago Santos and his colleagues at the University of Aveiro, Portugal, stands out as some of the most successful in manufacturing everyday ceramic objects with microwaves. Their latest article (23) provides a comprehensive review of this research, highlighting the following key benefits:

Significant reduction in sintering time and energy consumption.

Lower firing temperatures (50–75 °C lowest than traditional methods) to achieve similar results.

Faster and more uniform densification of materials.

Comparable or superior mechanical properties of microwave-fired products compared to those fired conventionally.

Challenges still exist in accurately measuring sintering temperatures, as thermocouples and pyrometers have limitations. However, analysing the final colour of the ceramics, glazes, and decals can serve as a useful tool for assessing and mapping the firing temperature of the finished pieces [

23].

1.3. Aim of the Article

The performance of microwave heating, particularly its time-saving benefits for firing traditional ceramic pieces, makes it a compelling option for craftspeople or amateurs producing small quantities or unique pieces. The absence of commercial devices for this purpose makes it tempting to build such a system using readily available materials, especially given how common microwave appliances are.

The purpose of this article is to demonstrate that it is feasible to build and use a controllable and configurable microwave kiln—one with adjustable temperature, heating rates, and duration—for firing traditional artisanal or artistic ceramics. We will show that this can be done using materials and equipment available from standard retailers. This article will also highlight the great flexibility of microwave heating for artisanal ceramic production, even in a less-than-perfectly configured kiln.

We will tackle the most difficult questions of development of susceptors that can be made by the craftsperson using mineral powders in their own workshop. The thermal, physical, and mineralogical behaviours of these susceptors will be described in an initial analysis. We will also evaluate their potential impact on the kiln’s oxidation-reduction properties. To illustrate the process, some examples of firing earthenware, porcelain, and enamels will be presented. Finally, we will compare the advantages and disadvantages of this method to a conventional kiln.

5. Discussion

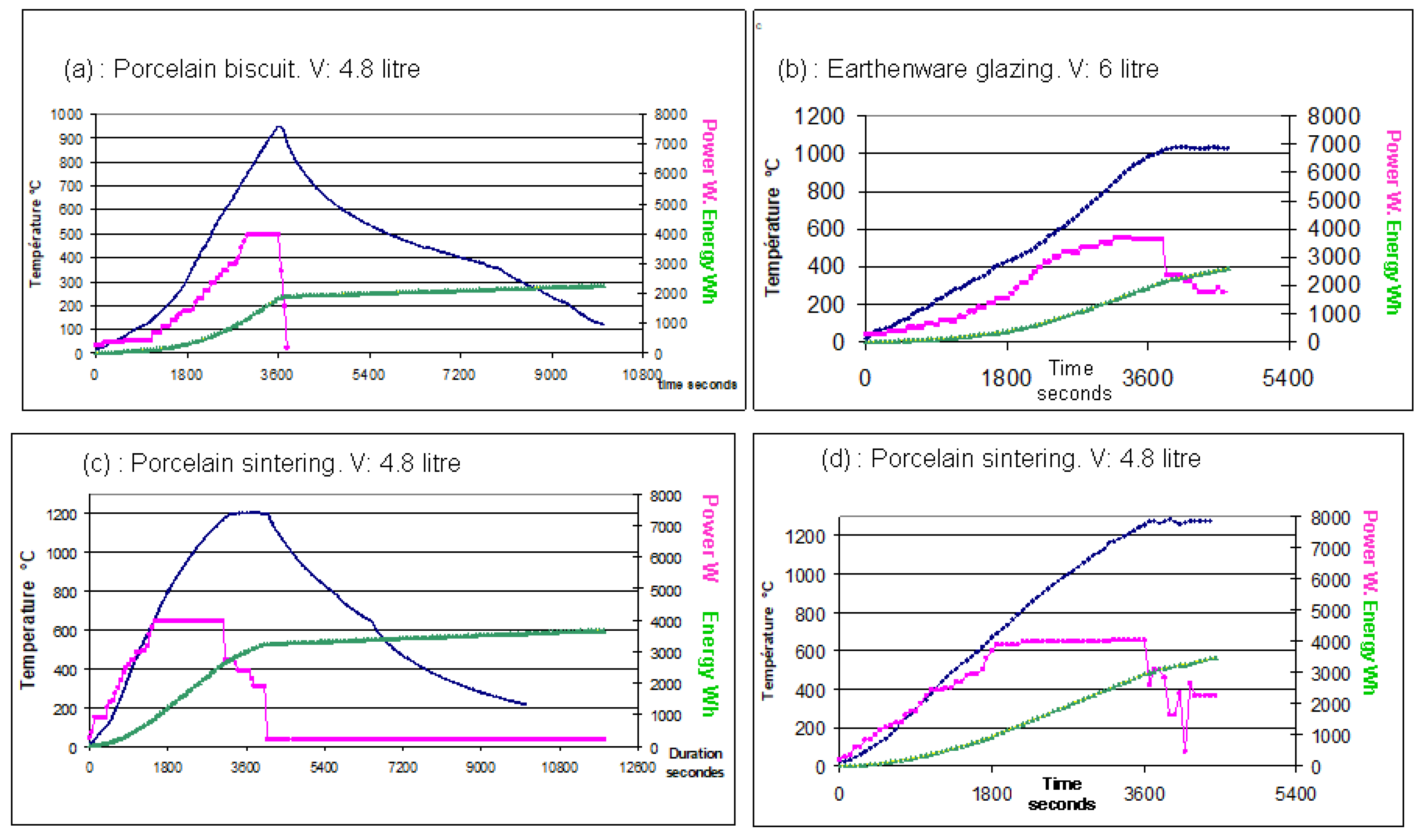

The primary objective of this study—to demonstrate the feasibility of constructing an easily accessible microwave kiln for artisan ceramic firing—was successfully achieved. The resulting kiln, built from readily available components, is suitably sized for craft production, capable of firing and glazing earthenware, stoneware and porcelain up to 1280 °C with satisfactory results. Its practical utility is underscored by its efficiency: the ability to fire pieces up to 21×21×12 cm within hours represents a substantial time and convenience advantage over conventional kilns. Although the current mechanical and electrical setup requires optimisation—specifically through a centralised, automated control system and better-calibrated power regulation—a strong correlation between heating rate and electrical power suggests that precise control could effectively compensate for potential temperature measurement inaccuracies (

Figure 26). However, the temperatures derived from the analysis of mineral reactions on the susceptors did not reveal any inconsistencies with the temperatures measured using thermocouples or optical pyrometry with a commercial device.

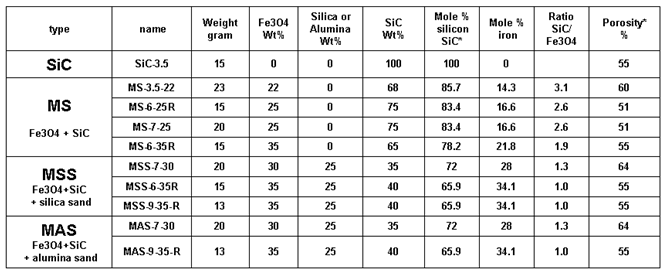

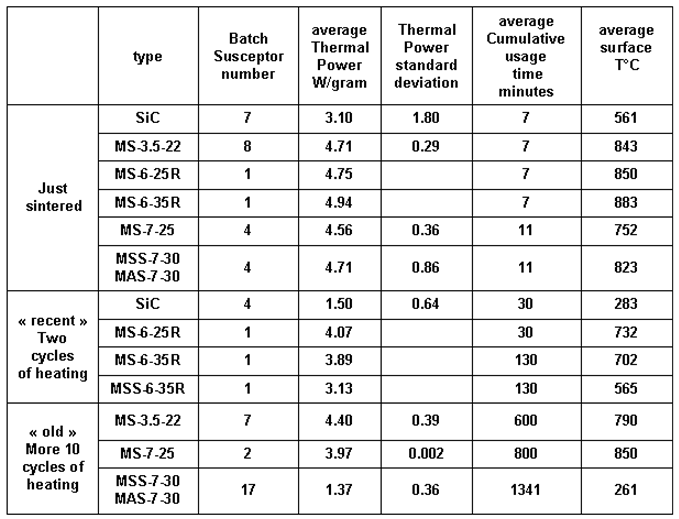

Beyond the practical construction, a key scientific challenge was the development of an inexpensive, efficient, and durable susceptor for hybrid microwave heating. This challenge led to the investigation of SiC-Fe₃O₄ composite materials. Optimal compositions were identified, leading to two distinct products: a high-durability susceptor (Fe₃O₄≤25 wt% of SiC content) comparable in performance to commercial SiC susceptors; and a highest Fe₃O₄ content one (40 to 50 wt% of Fe₃O₄) with limited durability but unique redox properties.

The intriguing behavior of the magnetite-rich susceptors, which exhibited evidence of partial fusion, revealed a significant insight into the material’s function. The physicochemical conditions attained within these susceptors mimic those found in industrial processes like steel slag or ferrosilicon production [

38] or in environments with a high reducing power, such as those found in the Earth’s mantle or in meteorites [

49,

50]. These are characterised by extremely low oxygen environments and liquidus temperatures as low as 1200 °C for the iron-rich Fe-Si-Al-O system.

In the susceptors, Fe₃O₄ acts as a “catalyst,” initiating the reactive sintering of SiC due to its strong microwave absorption. During this process, silicon carbide is consumed and replaced by ferrosilicon and silica as carbon burn away. The synergistic combination of dielectric loss (SiC) and magnetic loss (Fe/ferrosilicon), generated by eddy currents within the metallic cores [

51,

52], maintains the material’s thermal performance.

Incidentally, the partial melting and subsequent expulsion of molten material and gaseous products from the susceptors in high magnetite variants facilitates an interface between the internal susceptor environment and the furnace atmosphere allowing the furnace to potentially operate under reducing conditions. While this partial melting compromises long-term durability, the resulting reducing environment is a highly desirable asset for specific ceramic glazes and body compositions (46).

Future research must focus on validating this reducing atmosphere for the whole kiln hypothesis through detailed glaze analysis (23, 46). Furthermore, the observation that the Fe₃O₄ additive enables the reactive sintering of SiC at low temperature (850 °C–950 °C) and low pressure (1 bar) to form a silicate binder represents an incidental but highly promising avenue for developing new, low-energy SiC based material manufacturing processes.

6. Conclusions

This work has demonstrated the possibility for a ceramic craftsman or amateur to use a microwave oven to fire earthenware and porcelain up to approximately 1280 °C. The system’s operation is similar to that of a conventional microwave.

With ramp up firing cycles taking only 1 hours, the time savings are considerable. Despite a reduced volume, the energy consumption per object is equivalent to that of a large kiln, offering a flexibility previously unknown in ceramics. This allows for the finished object to be obtained soon after its design.

The process is exceptionally efficient, allowing a ceramist to prepare a piece in the morning, fire it before lunch, and remove it after coffee, thereby demonstrating extraordinary ease of use and a significant time-saving advantage over traditional kilns.

The results and difficulties encountered align with those described in the literature, both in terms of the remarkable quality of the finished products and the challenges in understanding the actual temperature conditions they experienced (23). It is surprising that, despite a lack of precise temperature and power control, the results were consistently excellent. This suggests that the ceramic piece, rather than the kiln, might be controlling the firing process.

The research conducted to create susceptors from readily available materials led to the development of components with unexpected capabilities. Not only do they provide efficient heating, but they also have the capacity to reduce the atmosphere of the kiln. This latter ability, which still needs to be fully demonstrated on a kiln-wide scale, could represent a new advancement for ceramic firing using electricity.

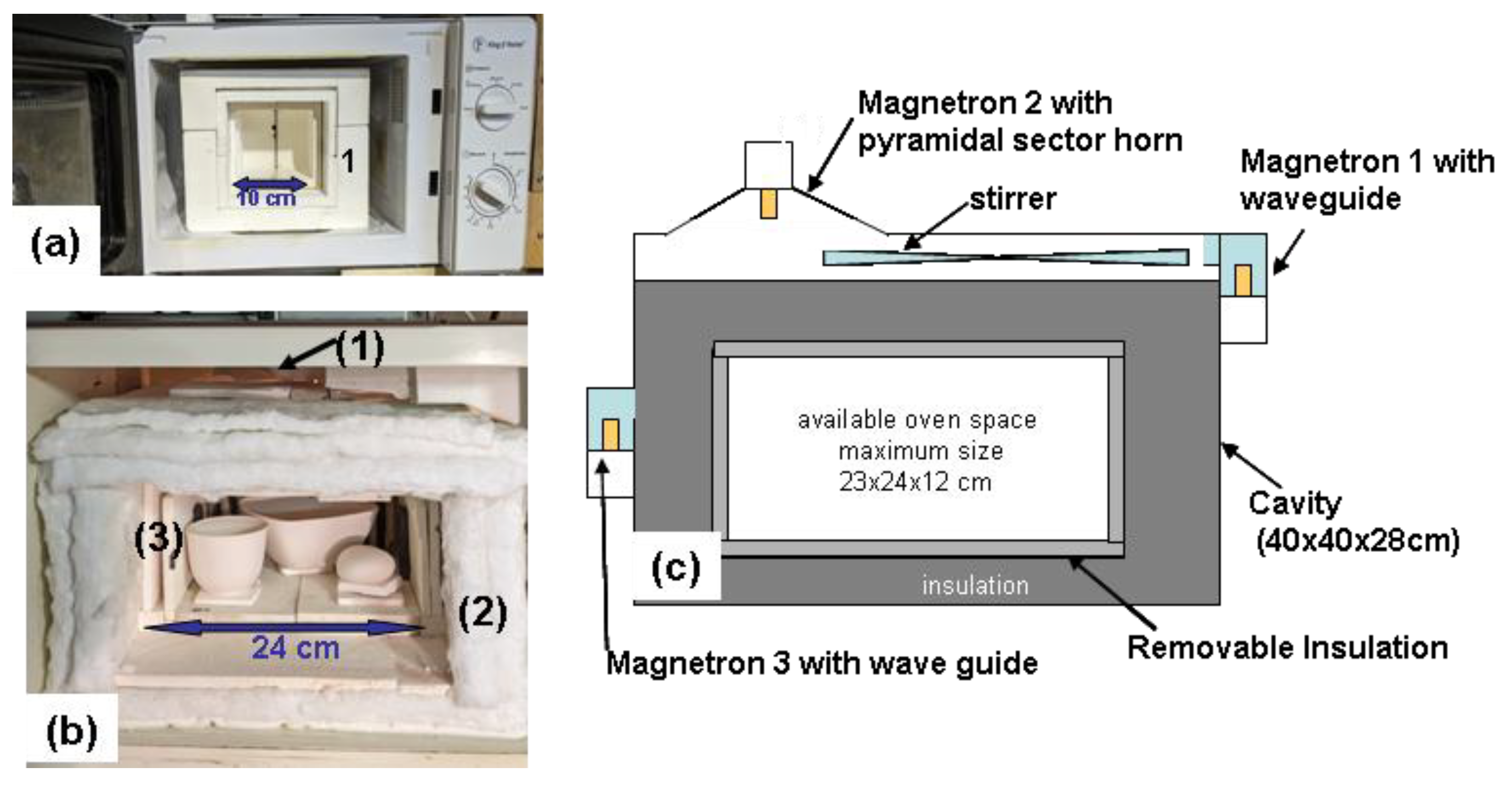

Figure 1.

Modified Microwave Kilns :(a) small, 18-litre microwave containing (1) an insulated 0.8-litre high-temperature cell. (b) interior view of the tri magnetron large kiln : 1) mode stirrer, (2) insulation fibres, (3) refractory brick plates, the kiln is loaded with three porcelain pieces for glazing. (c) construction diagram showing how three microwave ovens were combined to form a large, triple-magnetron setup. Note: The high-temperature cells are sealed with an insulated wall before the main door is closed.

Figure 1.

Modified Microwave Kilns :(a) small, 18-litre microwave containing (1) an insulated 0.8-litre high-temperature cell. (b) interior view of the tri magnetron large kiln : 1) mode stirrer, (2) insulation fibres, (3) refractory brick plates, the kiln is loaded with three porcelain pieces for glazing. (c) construction diagram showing how three microwave ovens were combined to form a large, triple-magnetron setup. Note: The high-temperature cells are sealed with an insulated wall before the main door is closed.

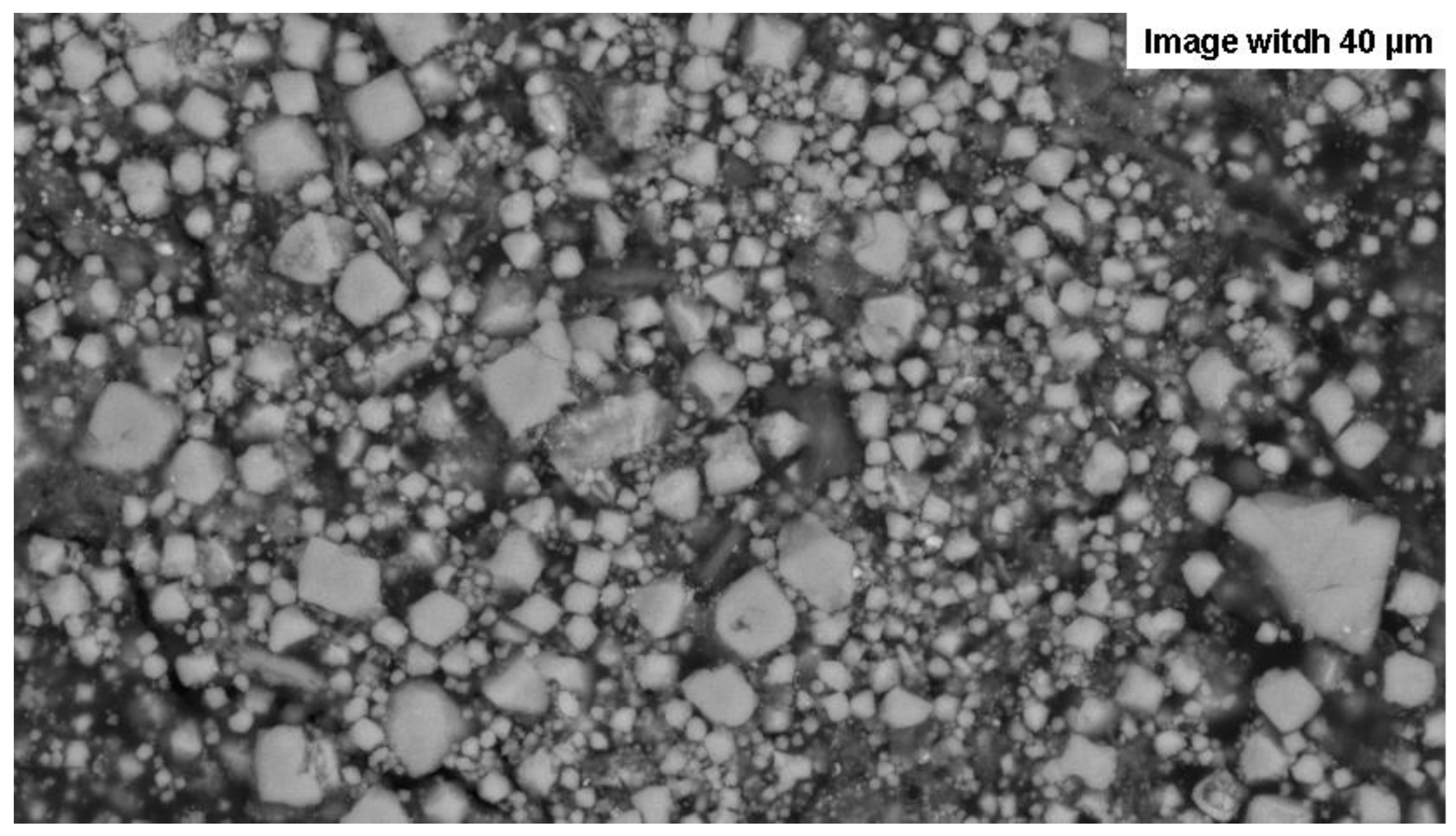

Figure 2.

SEM image of the magnetite powder used to create the susceptors. The image also reveals that some grains are agglomerated, as seen in the bottom right, which necessitates light grinding.

Figure 2.

SEM image of the magnetite powder used to create the susceptors. The image also reveals that some grains are agglomerated, as seen in the bottom right, which necessitates light grinding.

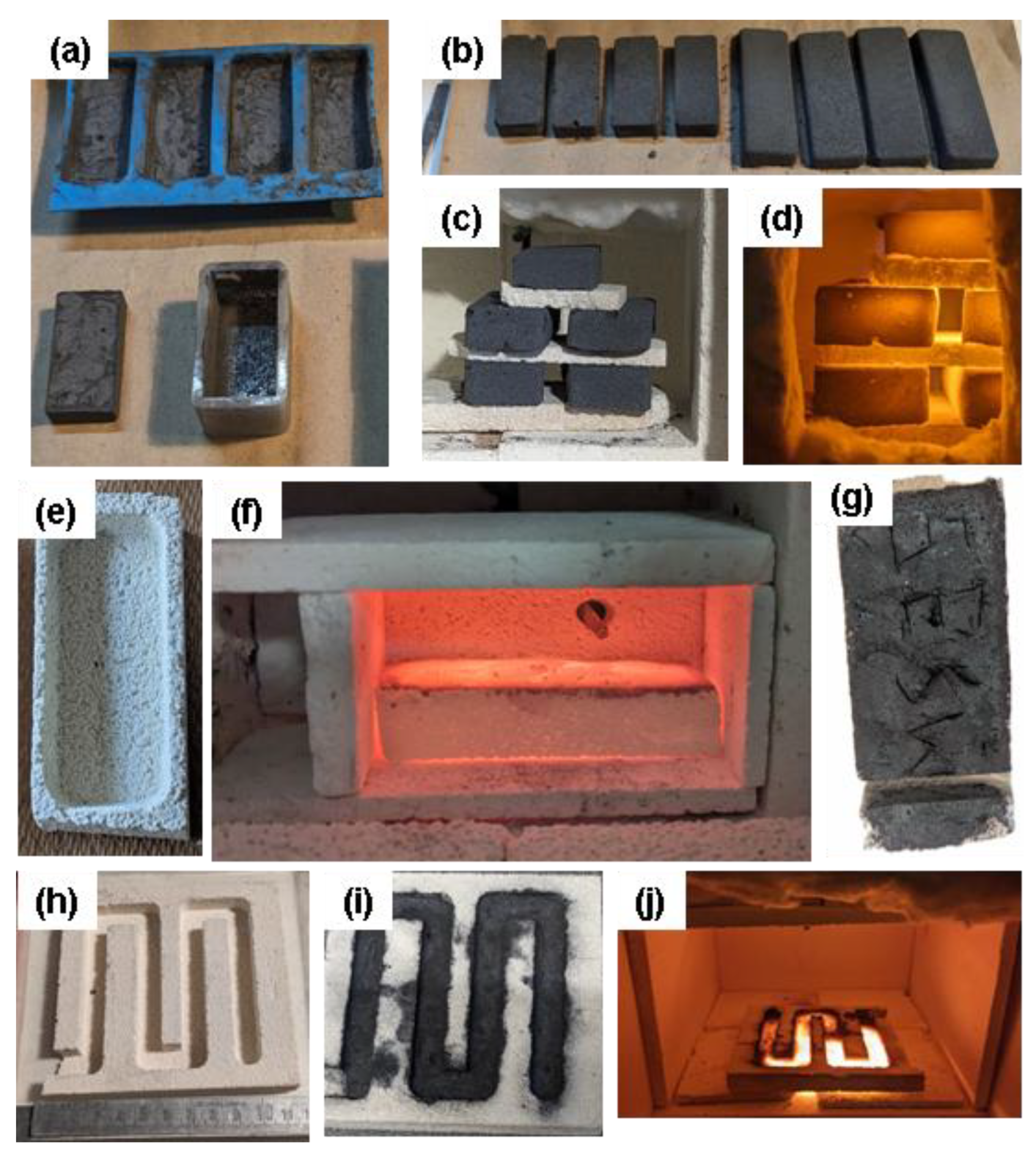

Figure 3.

Illustration of the steps of moulding and sintering powders to manufacture susceptors of various shapes. (a) Silicone moulds, 5 cm and 4 cm long. (b) Batch of 5-7 cm long susceptors, moulded and dried before sintering. (c) and (d) Batch of five susceptors undergoing sintering, viewed through the shutter of the small microwave oven door. (e) A mould milled into a refractory brick. (f) sintering inside a small 100 cm³ furnace built within the 800 cm³ furnace of the small microwave oven with a thermocouple positioned 0,6cm above the surface of the susceptor. (g) Susceptor after sintering (the base is cut for analysis). (h) 10x10 cm “snake” mould milled into a refractory brick, (i) with the powder mixture, (j) just after sintering, the blackish area at the two ends of the mould resulted from a heterogeneous powder mixture.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the steps of moulding and sintering powders to manufacture susceptors of various shapes. (a) Silicone moulds, 5 cm and 4 cm long. (b) Batch of 5-7 cm long susceptors, moulded and dried before sintering. (c) and (d) Batch of five susceptors undergoing sintering, viewed through the shutter of the small microwave oven door. (e) A mould milled into a refractory brick. (f) sintering inside a small 100 cm³ furnace built within the 800 cm³ furnace of the small microwave oven with a thermocouple positioned 0,6cm above the surface of the susceptor. (g) Susceptor after sintering (the base is cut for analysis). (h) 10x10 cm “snake” mould milled into a refractory brick, (i) with the powder mixture, (j) just after sintering, the blackish area at the two ends of the mould resulted from a heterogeneous powder mixture.

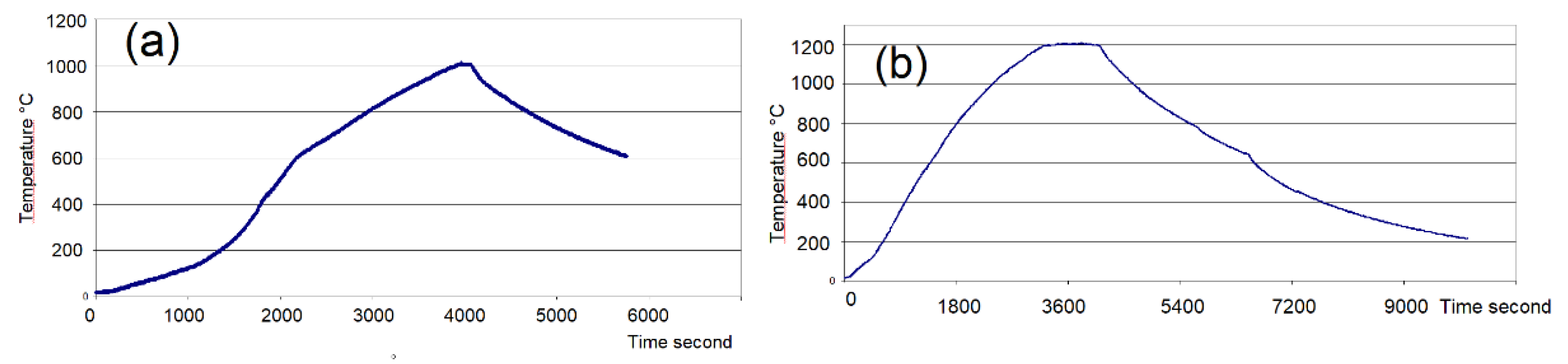

Figure 4.

Typical Firing Cycles in the Large Microwave Kiln

. The kiln’s volume was 4.8 litres. The temperature was measured by a type K thermocouple placed at the top side of the kiln.

(a): Firing of 320g of biscuit earthenware to 1005 °C.

(b) : Firing of 310g of glazed porcelain to 1210 °C (

Figure 1 (e)).

Figure 4.

Typical Firing Cycles in the Large Microwave Kiln

. The kiln’s volume was 4.8 litres. The temperature was measured by a type K thermocouple placed at the top side of the kiln.

(a): Firing of 320g of biscuit earthenware to 1005 °C.

(b) : Firing of 310g of glazed porcelain to 1210 °C (

Figure 1 (e)).

Figure 5.

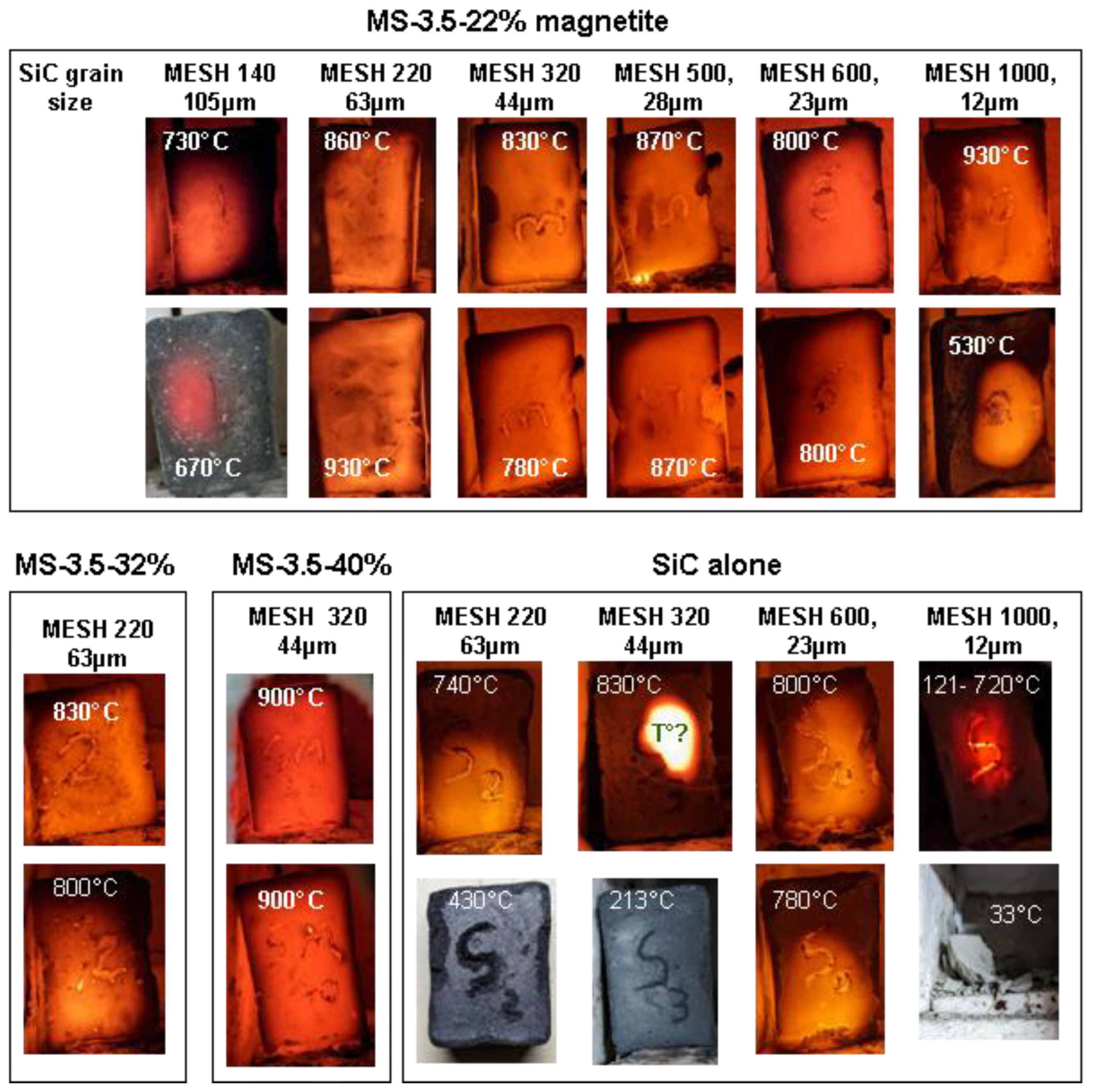

Images of the first sintering runs performed to identify the best susceptor formulations. Susceptors measuring 3.5 x 2 x 1 cm were systematically placed in the same upright position inside the small microwave kiln, facing the door shutter. The sintering time was 10 minutes except for MS-3.5-22% MESH 1000 where it is 20 minutes. Temperature is measured with an optical pyrometer through the shutter. The samples placed in the same column came from the same 7cm casting cut in two halves and sintered independently to test the reproducibility.

Figure 5.

Images of the first sintering runs performed to identify the best susceptor formulations. Susceptors measuring 3.5 x 2 x 1 cm were systematically placed in the same upright position inside the small microwave kiln, facing the door shutter. The sintering time was 10 minutes except for MS-3.5-22% MESH 1000 where it is 20 minutes. Temperature is measured with an optical pyrometer through the shutter. The samples placed in the same column came from the same 7cm casting cut in two halves and sintered independently to test the reproducibility.

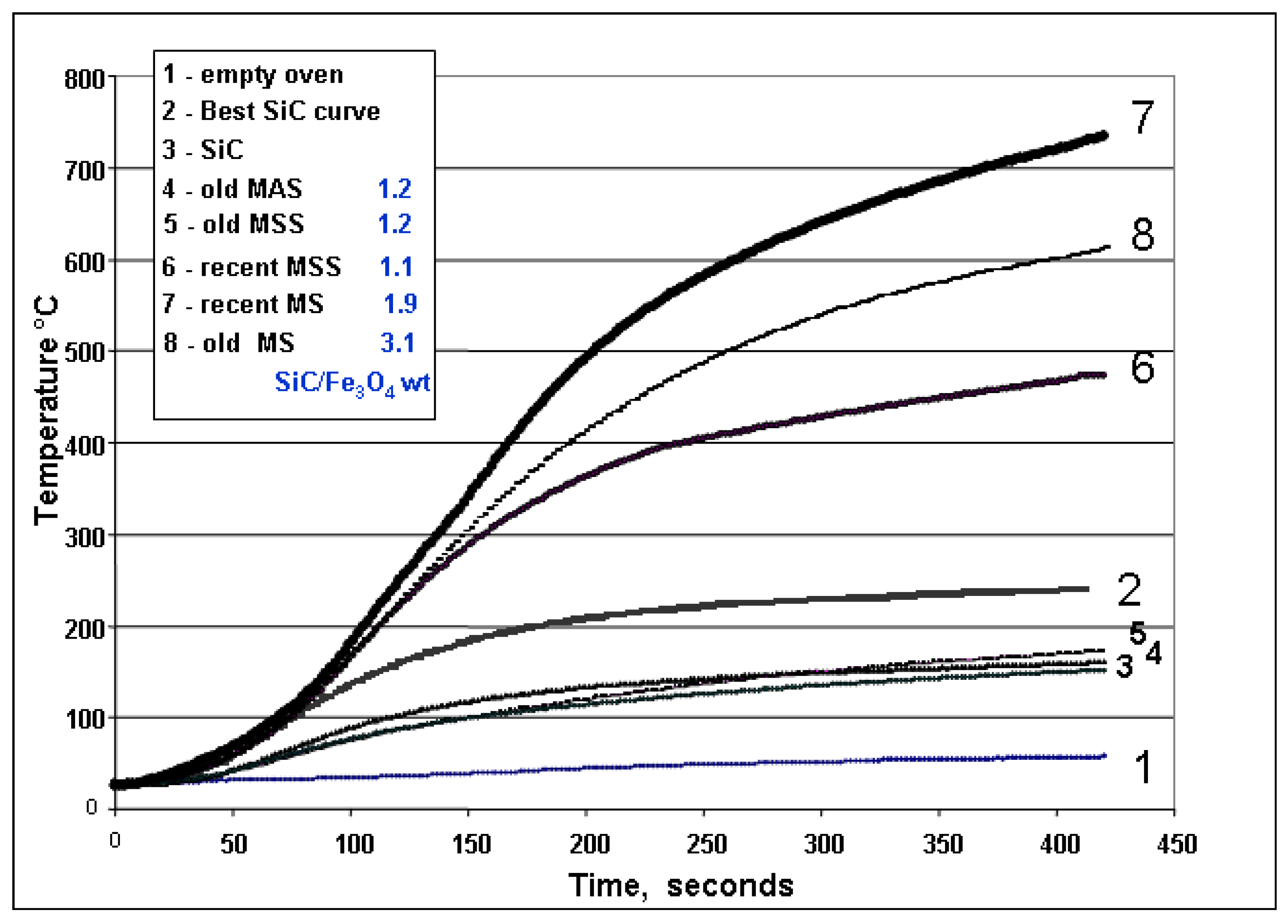

Figure 6.

Average Heating Curves for Susceptors. This diagram shows the average heating curves over 420 seconds of the small, 100 cm

3 oven (

Figure 4 (f)) by the main susceptors batches. The nomenclature corresponds to that in

Table 1 and

Table 3.

Figure 6.

Average Heating Curves for Susceptors. This diagram shows the average heating curves over 420 seconds of the small, 100 cm

3 oven (

Figure 4 (f)) by the main susceptors batches. The nomenclature corresponds to that in

Table 1 and

Table 3.

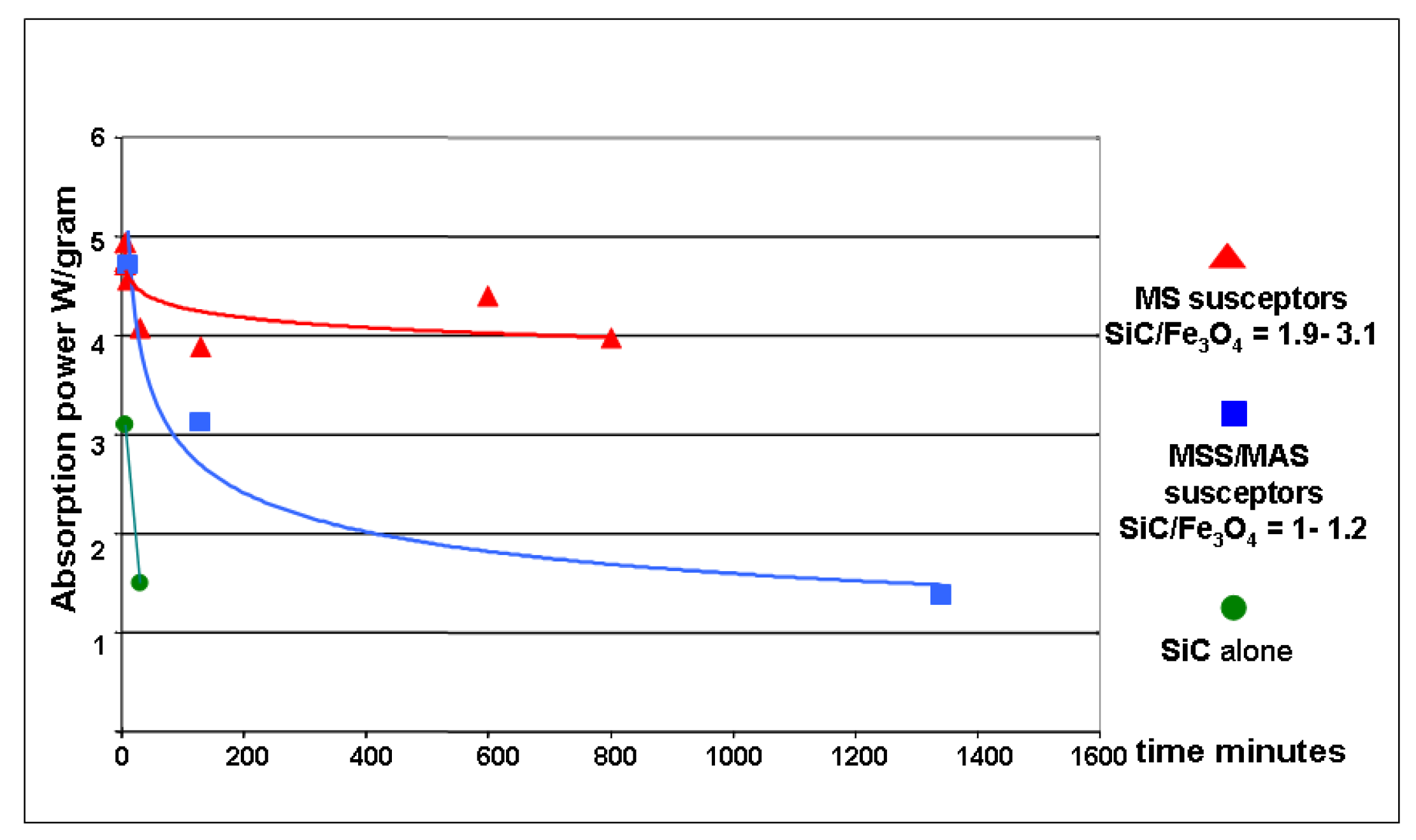

Figure 7.

Plot of the absorption power as a function of cumulated firing time. Average absorption power (W/gram) is found to decrease over time for the three main types of susceptor batches.

Figure 7.

Plot of the absorption power as a function of cumulated firing time. Average absorption power (W/gram) is found to decrease over time for the three main types of susceptor batches.

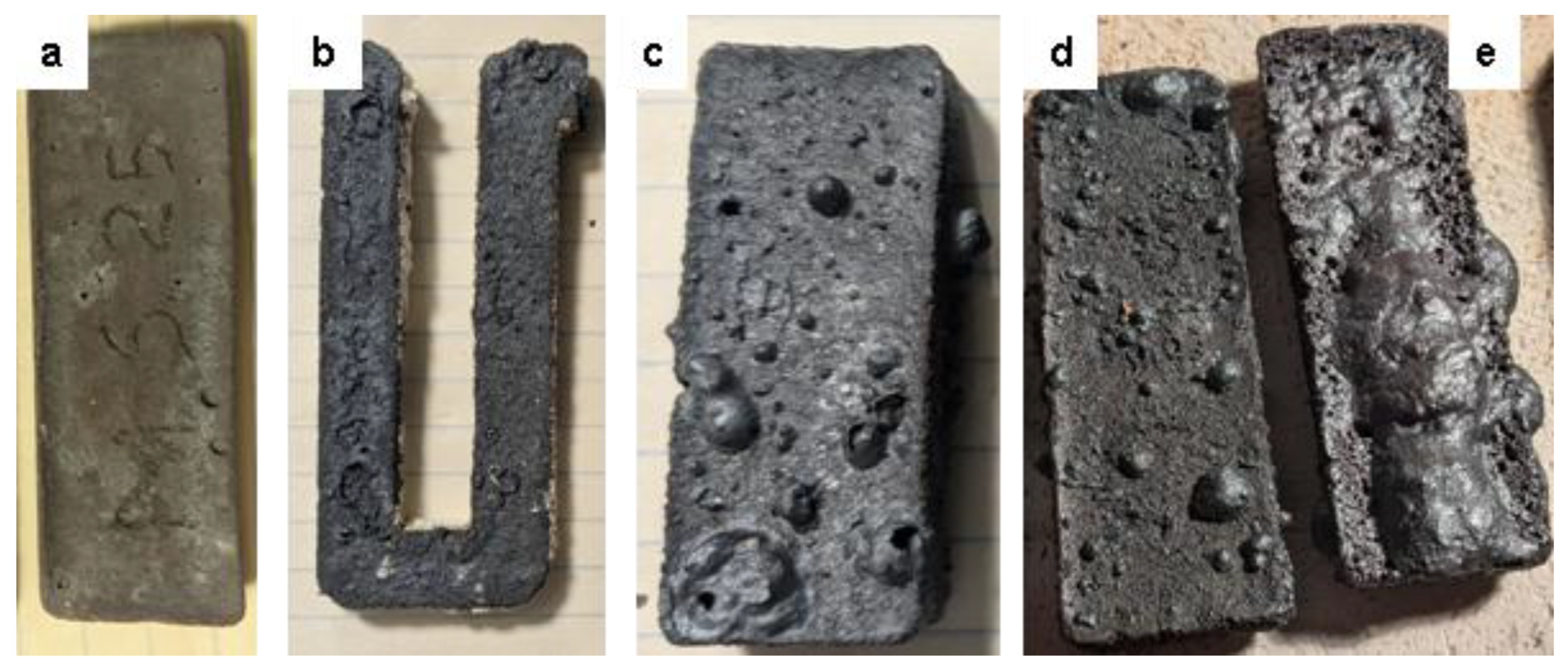

Figure 8.

Physical changes in various susceptors over time.

(a) MS -25 low iron type susceptor after 10 hours of cumulative heating in firings between 1000 °C and 1300 °C. (

b) U-shaped MSS -30 susceptor cut from the “snake-shaped” susceptor (

Figure 4 (i), (j)), after 15 hours of cumulative heating of earthenware at 1050-1070 °C, showing traces of melting structures.

(c) MSS7-30 high iron type susceptor

, after 20 hours of earthenware and porcelain firings between 1000 °C and 1270 °C showing melting bubbles on its surface.

(d) MSS-30 and

(e) MAS-30 susceptors used under the same conditions as susceptor

(c), but with an additional 75-minutes porcelain firing up to 1300 °C showing a molten film on the MAS susceptor surface while the MSS shows the same melting bubbles as before this additional firing.

Figure 8.

Physical changes in various susceptors over time.

(a) MS -25 low iron type susceptor after 10 hours of cumulative heating in firings between 1000 °C and 1300 °C. (

b) U-shaped MSS -30 susceptor cut from the “snake-shaped” susceptor (

Figure 4 (i), (j)), after 15 hours of cumulative heating of earthenware at 1050-1070 °C, showing traces of melting structures.

(c) MSS7-30 high iron type susceptor

, after 20 hours of earthenware and porcelain firings between 1000 °C and 1270 °C showing melting bubbles on its surface.

(d) MSS-30 and

(e) MAS-30 susceptors used under the same conditions as susceptor

(c), but with an additional 75-minutes porcelain firing up to 1300 °C showing a molten film on the MAS susceptor surface while the MSS shows the same melting bubbles as before this additional firing.

Figure 9.

Apparent Temperature Homogeneity of Susceptors as view in a heating test of 10 recent magnetite-based susceptors after 11 minutes of firing. The total weight of these 10 susceptors is 185g. The temperature of the oven, measured by a thermocouple visible at the top centre, was 810 °C just before the aperture was opened. The temperature of the susceptor surface at the time the photograph was taken was 750 °C, measured using an optical pyrometer.

Figure 9.

Apparent Temperature Homogeneity of Susceptors as view in a heating test of 10 recent magnetite-based susceptors after 11 minutes of firing. The total weight of these 10 susceptors is 185g. The temperature of the oven, measured by a thermocouple visible at the top centre, was 810 °C just before the aperture was opened. The temperature of the susceptor surface at the time the photograph was taken was 750 °C, measured using an optical pyrometer.

Figure 10.

SEM image of a MS-25 type susceptor after 7 minutes of sintering at 850 °C. It reveals a matrix of silicon carbide grains, coated with fine ferrosilicon particles and an overlying layer of cristobalite. Localised precipitation of hematite and dispersed iron droplets are observable within the porous regions.

Figure 10.

SEM image of a MS-25 type susceptor after 7 minutes of sintering at 850 °C. It reveals a matrix of silicon carbide grains, coated with fine ferrosilicon particles and an overlying layer of cristobalite. Localised precipitation of hematite and dispersed iron droplets are observable within the porous regions.

Figure 11.

SEM images and EBSD/EDS analyses of the MS-25 susceptor shown in

Figure 10, following an additional 18-minute heating up to 1100 °C.

(a) Overall view, displaying two distinct droplets of BCC iron (image width : 970µm).

(b) EDS spectrum of the BCC iron, revealing trace contaminants of Mn and Cr, attributed to SiC grinding.

(c) Detailed view of an iron droplet, where variations in brightness correspond to two distinct crystal orientations.

(d), (e) EBSD analysis confirming the two different crystal orientations of BCC crystals.

(f) Detailed view (BSE-Si-Fe-O-C composite image) of the matrix (image width : 50 µm) with Cris : cristobalite, F fayalite.

Figure 11.

SEM images and EBSD/EDS analyses of the MS-25 susceptor shown in

Figure 10, following an additional 18-minute heating up to 1100 °C.

(a) Overall view, displaying two distinct droplets of BCC iron (image width : 970µm).

(b) EDS spectrum of the BCC iron, revealing trace contaminants of Mn and Cr, attributed to SiC grinding.

(c) Detailed view of an iron droplet, where variations in brightness correspond to two distinct crystal orientations.

(d), (e) EBSD analysis confirming the two different crystal orientations of BCC crystals.

(f) Detailed view (BSE-Si-Fe-O-C composite image) of the matrix (image width : 50 µm) with Cris : cristobalite, F fayalite.

Figure 12.

This figure presents a second SEM image of the MS-25 susceptor referenced in

Figure 11 complemented by chemical and crystallographic characterisation of minerals in the matrix.

(a) BSE-EDS-Si-Fe-O-C composite image (100 µm wide) details the cementation of silicon carbide (SiC) and Ferrosilicon (FeSi) grains. The cement consists of cristobalite (Cris) intergrown with Fayalite (Fa) and associated with magnetite (Ma).

(b) and

(c) show the EBSD crystallographic determination and EDS chemical analysis for magnetite.

(d) and

(e) provide similar EBSD and EDS analyses for fayalite.

Figure 12.

This figure presents a second SEM image of the MS-25 susceptor referenced in

Figure 11 complemented by chemical and crystallographic characterisation of minerals in the matrix.

(a) BSE-EDS-Si-Fe-O-C composite image (100 µm wide) details the cementation of silicon carbide (SiC) and Ferrosilicon (FeSi) grains. The cement consists of cristobalite (Cris) intergrown with Fayalite (Fa) and associated with magnetite (Ma).

(b) and

(c) show the EBSD crystallographic determination and EDS chemical analysis for magnetite.

(d) and

(e) provide similar EBSD and EDS analyses for fayalite.

Figure 13.

Microstructural and crystallographic analysis of the MS-25 shown in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12. (a) BSE image (plane view) illustrating the general morphological features. (b) BSE image acquired at a 70° tilt for EBSD analysis. (c) EBSD scanning map, accompanied by a table detailing the mineralogical proportions derived from the EBSD analysis (average from two different mapping). (d), (e) EDS chemical analyses and EBSD crystallographic determination of cristobalite. (f), (g) Similar EDS and EBSD analyses for moissanite 3C. (h), (i) Corresponding EDS and EBSD analyses for ferroan forsterite (fayalite substituted to a small extent by forsterite).

Figure 13.

Microstructural and crystallographic analysis of the MS-25 shown in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12. (a) BSE image (plane view) illustrating the general morphological features. (b) BSE image acquired at a 70° tilt for EBSD analysis. (c) EBSD scanning map, accompanied by a table detailing the mineralogical proportions derived from the EBSD analysis (average from two different mapping). (d), (e) EDS chemical analyses and EBSD crystallographic determination of cristobalite. (f), (g) Similar EDS and EBSD analyses for moissanite 3C. (h), (i) Corresponding EDS and EBSD analyses for ferroan forsterite (fayalite substituted to a small extent by forsterite).

Figure 14.

Micro-structural and Crystallographic Analysis of Ferrosilicon monocrystal in MS-25 Susceptor shown in

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13.

(a) BSE image (70° tilted sample), illustrating morphological features,

(b) EBSD scanning map

(c) Ferrosilicon mineralogical proportion derived from EBSD analysis,

(d), (e), (f) EDS analyses and

(g), (h), (i) EBSD crystallographic characterisation of three different ferrosilicon varieties identified within the susceptor matrix.

Figure 14.

Micro-structural and Crystallographic Analysis of Ferrosilicon monocrystal in MS-25 Susceptor shown in

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13.

(a) BSE image (70° tilted sample), illustrating morphological features,

(b) EBSD scanning map

(c) Ferrosilicon mineralogical proportion derived from EBSD analysis,

(d), (e), (f) EDS analyses and

(g), (h), (i) EBSD crystallographic characterisation of three different ferrosilicon varieties identified within the susceptor matrix.

Figure 15.

SEM and EBSD analysis of a aged MAS22 susceptor with low Fe₃O₄ content, after more than 10 ceramic heating cycles up to 1300 °C. (a) Composite BSE-EDS-Si-Al-Fe-O image showing fayalite or ferrous forsterite (Fa), Fe-Si-O glass (Fa-G), and cristobalite (Cris). (b) EBSD map. (c) Table summarises the quantitative phase proportions derived from the EBSD analysis.

Figure 15.

SEM and EBSD analysis of a aged MAS22 susceptor with low Fe₃O₄ content, after more than 10 ceramic heating cycles up to 1300 °C. (a) Composite BSE-EDS-Si-Al-Fe-O image showing fayalite or ferrous forsterite (Fa), Fe-Si-O glass (Fa-G), and cristobalite (Cris). (b) EBSD map. (c) Table summarises the quantitative phase proportions derived from the EBSD analysis.

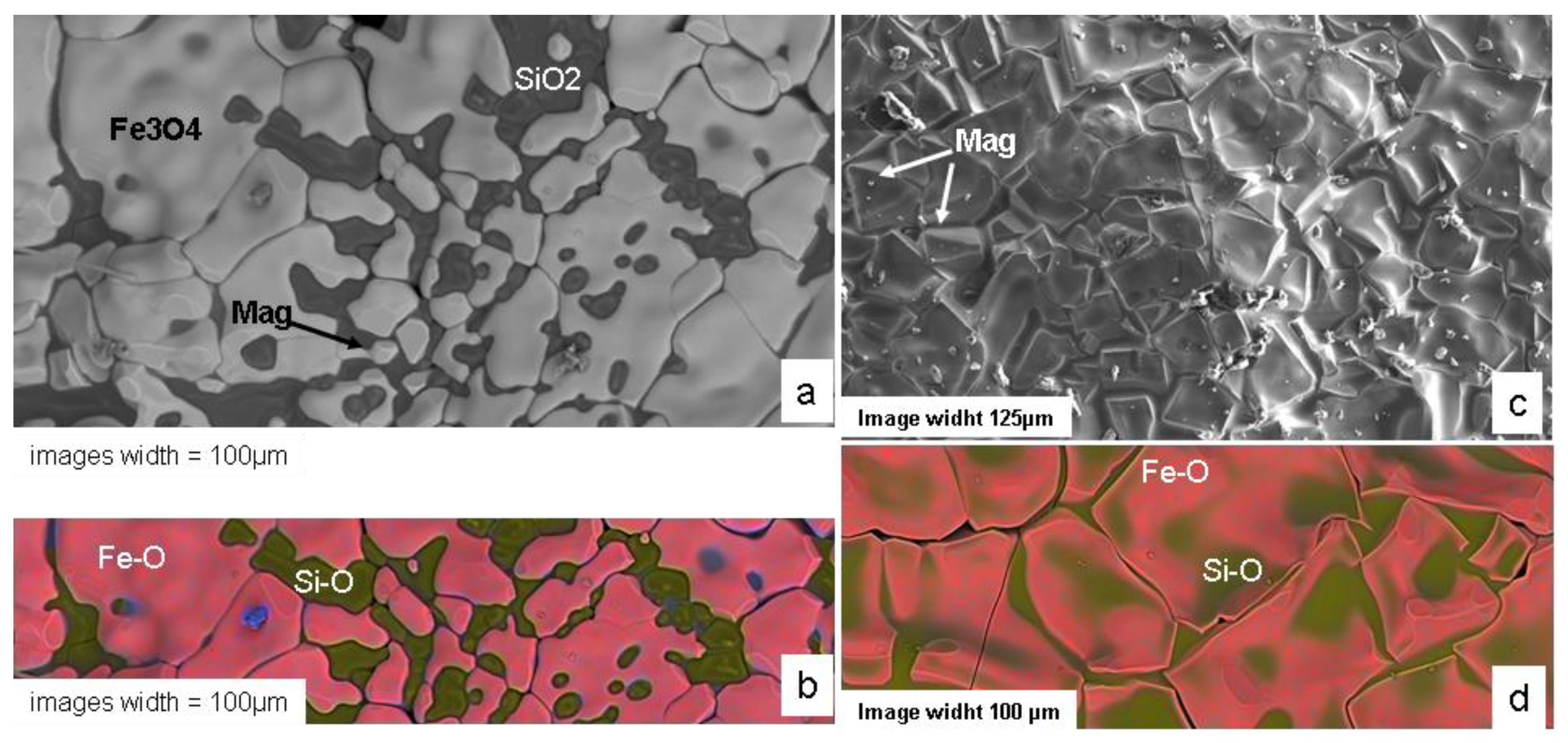

Figure 16.

SEM Image of a Recent MSS-35 susceptor cross-section. Cristobalite (Cri), Magnetite (mag), hematite-cristobalite intergrown (H+Cri).

Figure 16.

SEM Image of a Recent MSS-35 susceptor cross-section. Cristobalite (Cri), Magnetite (mag), hematite-cristobalite intergrown (H+Cri).

Figure 17.

SEM images of the surface features—bubble-like exudates on MSS susceptors and molten deposits on MAS susceptors (see

Figure 8 d, e). (a) BSE image and (b) BSE-EDS composite Si-Fe-O image of the molten deposit on the MAS susceptor. (c) SE image and (d) BSE-EDS composite Si-Fe-O image of a bubble on the MSS susceptor. Magnetite (Mag) is reported when the shape of the mineral is recognisable among Fe₃O₄ in the BSE (a) and SE (c) images.

Figure 17.

SEM images of the surface features—bubble-like exudates on MSS susceptors and molten deposits on MAS susceptors (see

Figure 8 d, e). (a) BSE image and (b) BSE-EDS composite Si-Fe-O image of the molten deposit on the MAS susceptor. (c) SE image and (d) BSE-EDS composite Si-Fe-O image of a bubble on the MSS susceptor. Magnetite (Mag) is reported when the shape of the mineral is recognisable among Fe₃O₄ in the BSE (a) and SE (c) images.

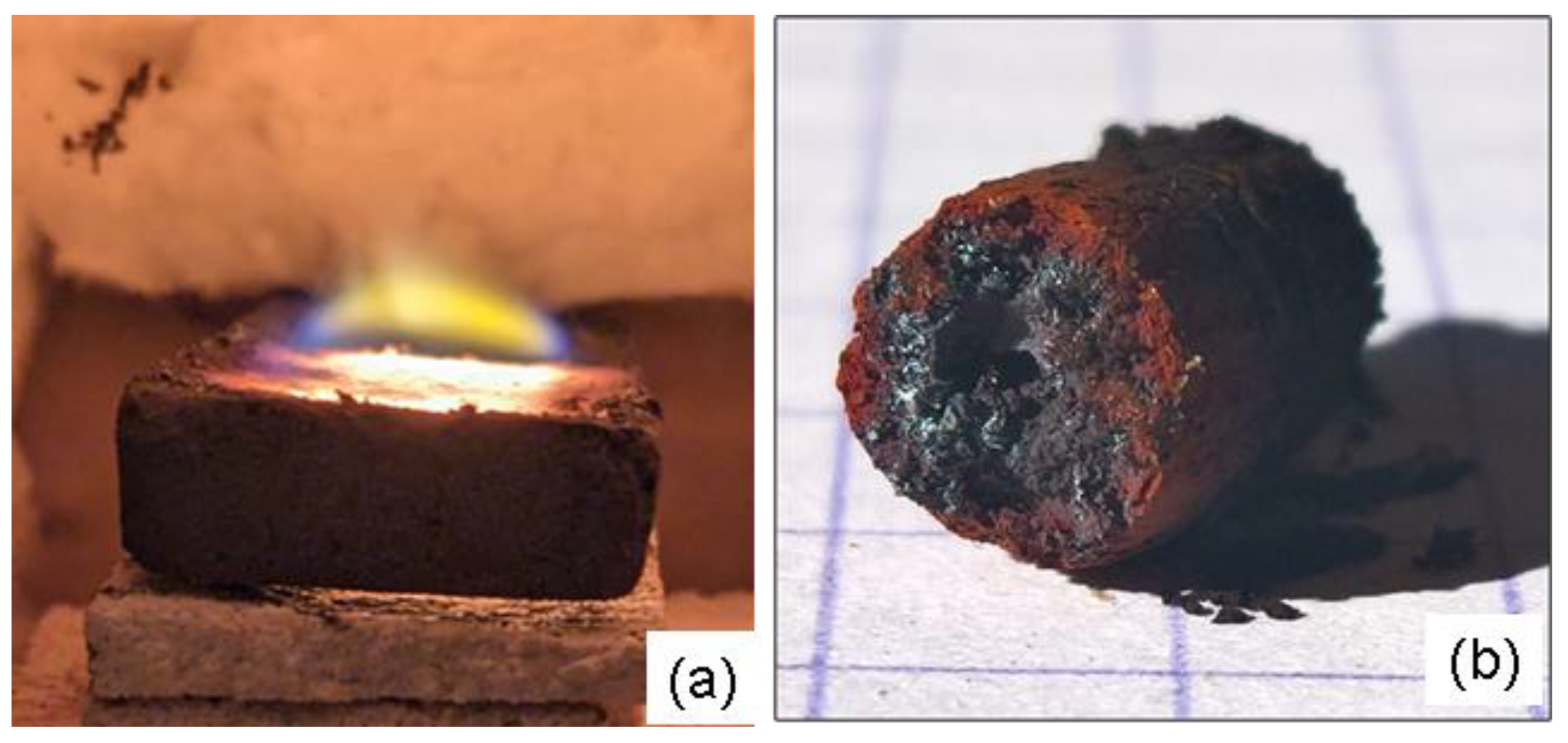

Figure 18.

(a) Image showing the flame produced by the combustion phenomenon that occurs during the initial minutes of a Fe₃O₄−SiC susceptor (7x2x0.8 cm in size) sintering process . (b) Image of the solid material formed by exposing submicroscopic magnetite powder inside a sealed silica tube showing the red crown structure around a black core (see text). The scale reference square on the paper measures 5mm.

Figure 18.

(a) Image showing the flame produced by the combustion phenomenon that occurs during the initial minutes of a Fe₃O₄−SiC susceptor (7x2x0.8 cm in size) sintering process . (b) Image of the solid material formed by exposing submicroscopic magnetite powder inside a sealed silica tube showing the red crown structure around a black core (see text). The scale reference square on the paper measures 5mm.

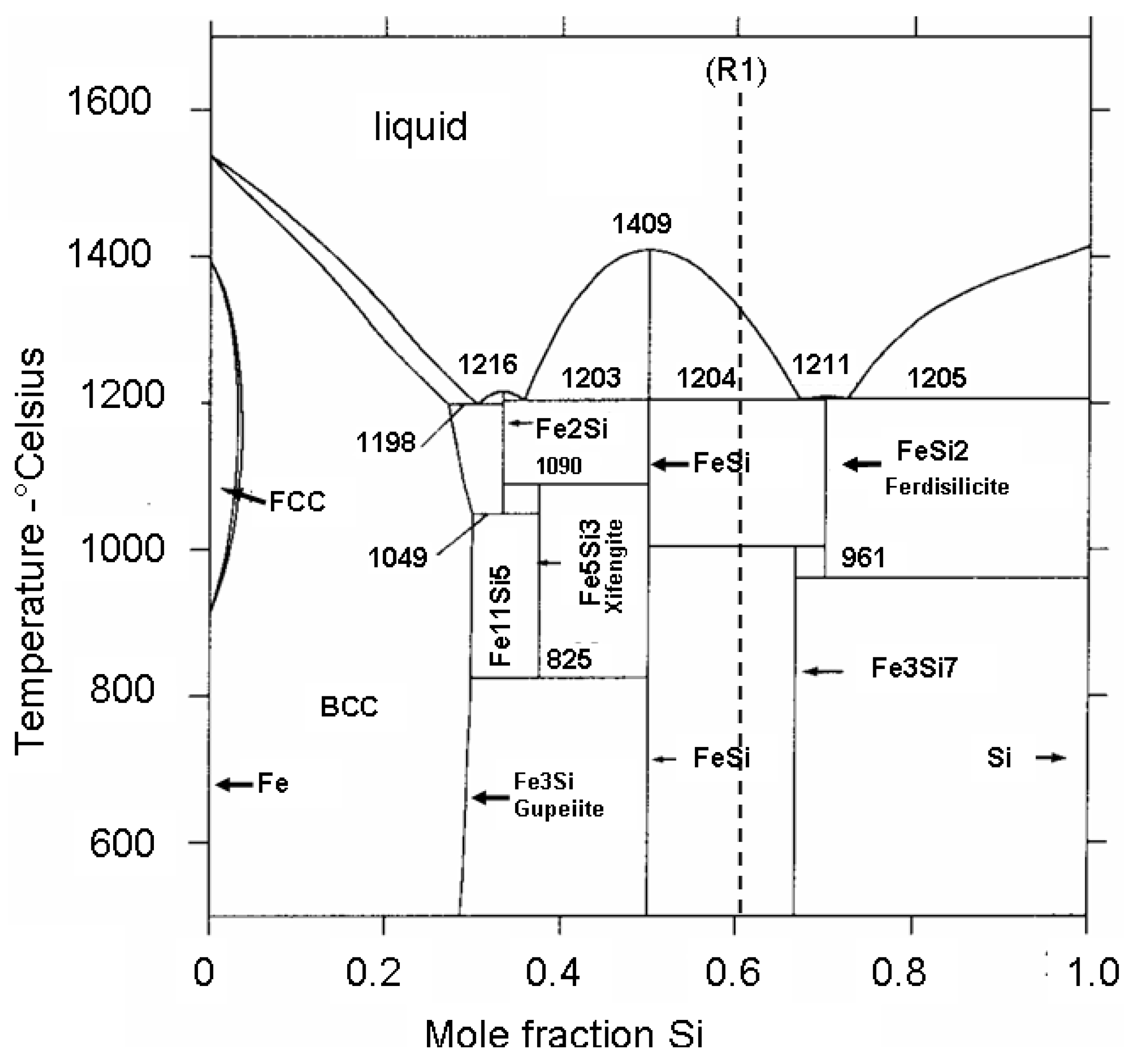

Figure 19.

Fe-Si phases diagramme adapted from (41) illustrating the stability domains of identified ferrosilicon (Gupeiite, Xifengite, Ferdisilicite and Fe11Si5). R1 dotted line indicates the composition of the reaction (R1) products (see text).

Figure 19.

Fe-Si phases diagramme adapted from (41) illustrating the stability domains of identified ferrosilicon (Gupeiite, Xifengite, Ferdisilicite and Fe11Si5). R1 dotted line indicates the composition of the reaction (R1) products (see text).

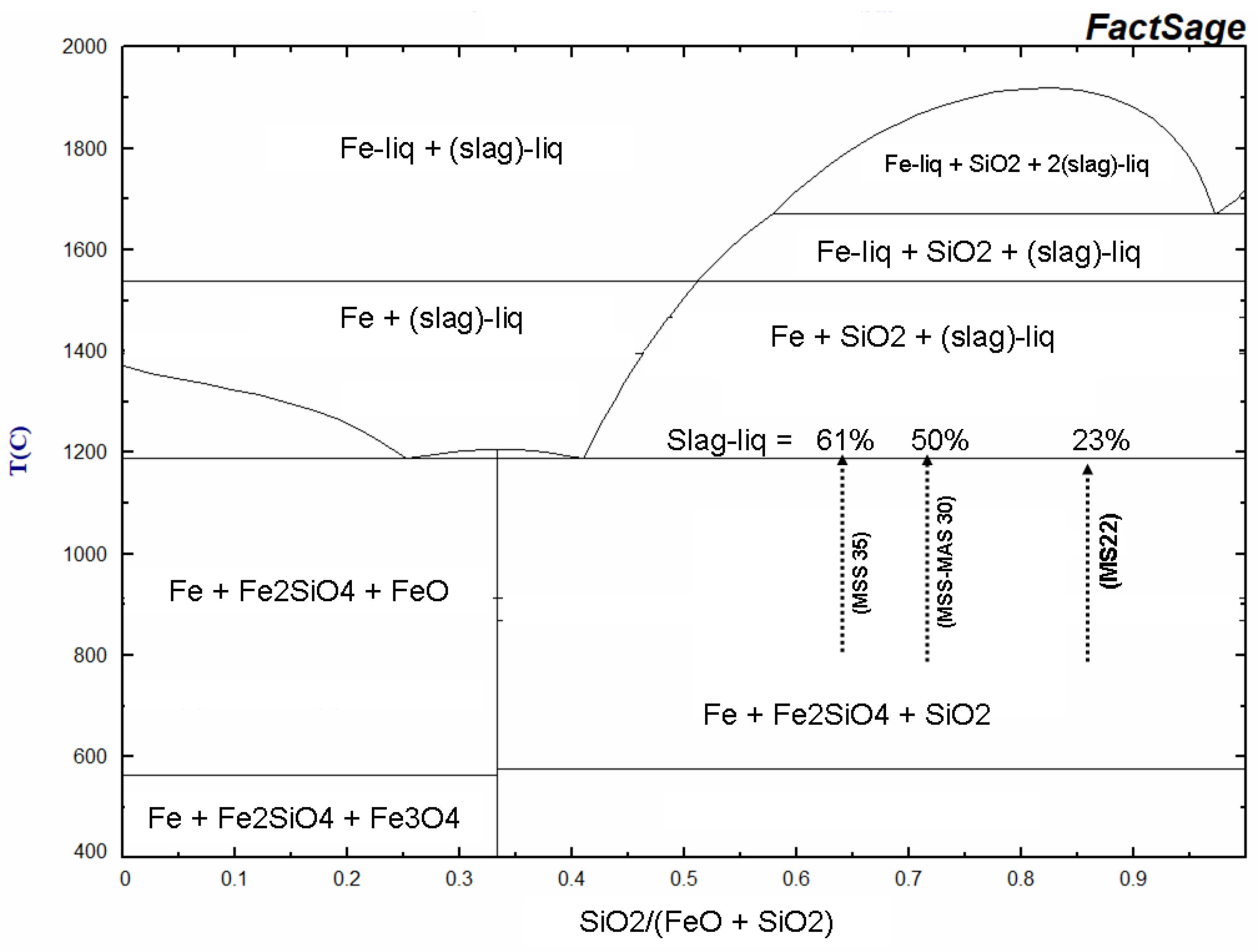

Figure 20.

Simplified phase relation of the FeO- SiO

2 system in equilibrium with metallic Fe calculated using FactSage [

45]. Liq = liquide, Slag = Fe-Si-O melting phase. Arrows indicate the SiO

2 fraction in the susceptor in function of their global composition with the corresponding melting proportions.

Figure 20.

Simplified phase relation of the FeO- SiO

2 system in equilibrium with metallic Fe calculated using FactSage [

45]. Liq = liquide, Slag = Fe-Si-O melting phase. Arrows indicate the SiO

2 fraction in the susceptor in function of their global composition with the corresponding melting proportions.

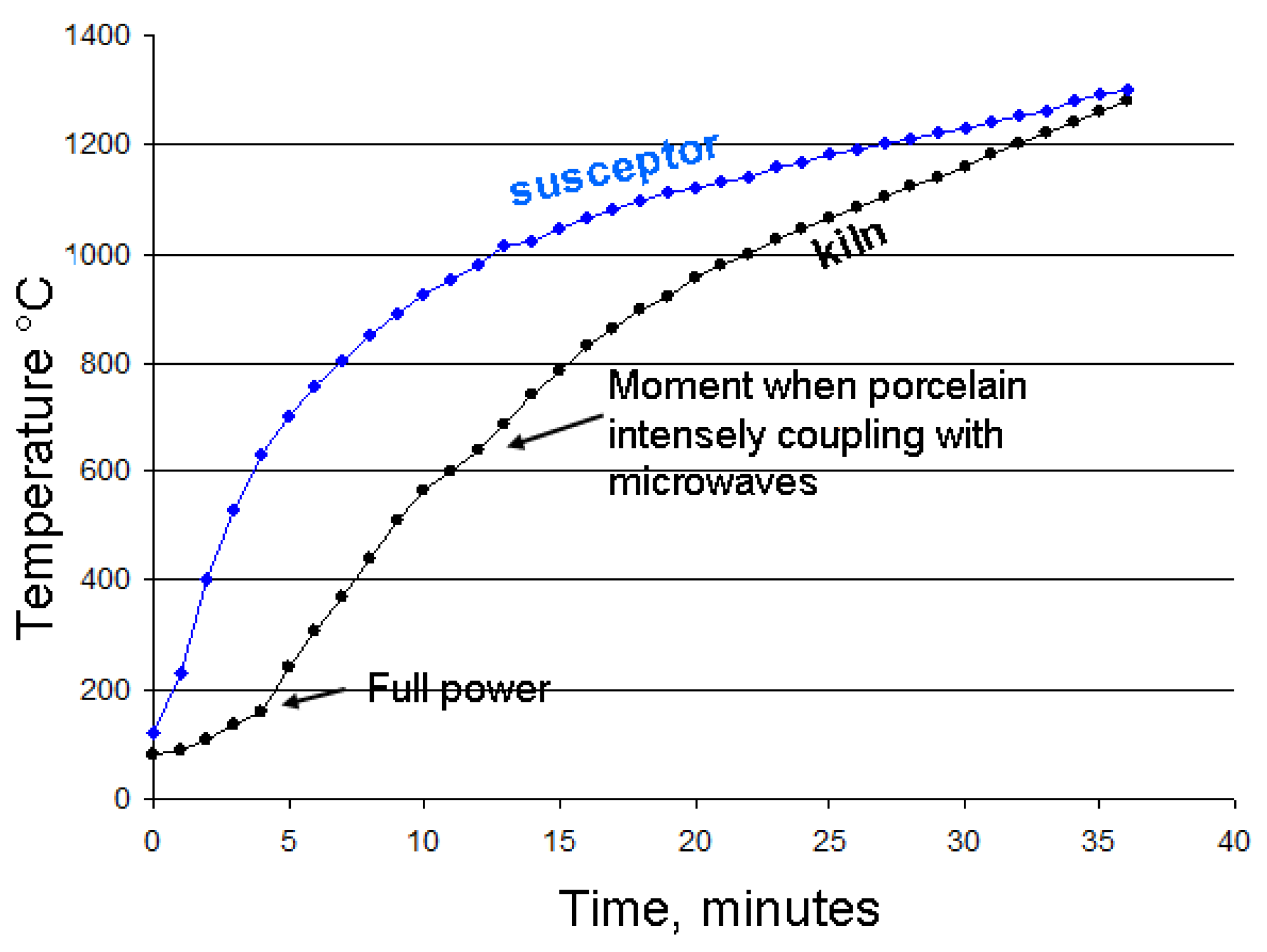

Figure 21.

This diagram compares the heating rate curves of the susceptor with those of the kiln for two similar porcelain firing to 1280 °C in the small microwave kiln. The measurements were taken separately during the two successive firings of identical porcelain pieces in the same kiln configuration (80g of porcelain, 80g of MS-25 susceptors).

Figure 21.

This diagram compares the heating rate curves of the susceptor with those of the kiln for two similar porcelain firing to 1280 °C in the small microwave kiln. The measurements were taken separately during the two successive firings of identical porcelain pieces in the same kiln configuration (80g of porcelain, 80g of MS-25 susceptors).

Figure 22.

Melting of JM23 Brick upon Contact with an Iron-Rich Susceptor during Porcelain Firing at 1300 °C. The silica-mullite that makes up the JM23 brick melts on contact with susceptors glasses (T°> Fe-Si-Al-O eutectic in reducing conditions). Despite this, the porcelain piece remained intact and was well-fired. The porcelain tealight holder is a handcrafted creation by Caroline Combes.

Figure 22.

Melting of JM23 Brick upon Contact with an Iron-Rich Susceptor during Porcelain Firing at 1300 °C. The silica-mullite that makes up the JM23 brick melts on contact with susceptors glasses (T°> Fe-Si-Al-O eutectic in reducing conditions). Despite this, the porcelain piece remained intact and was well-fired. The porcelain tealight holder is a handcrafted creation by Caroline Combes.

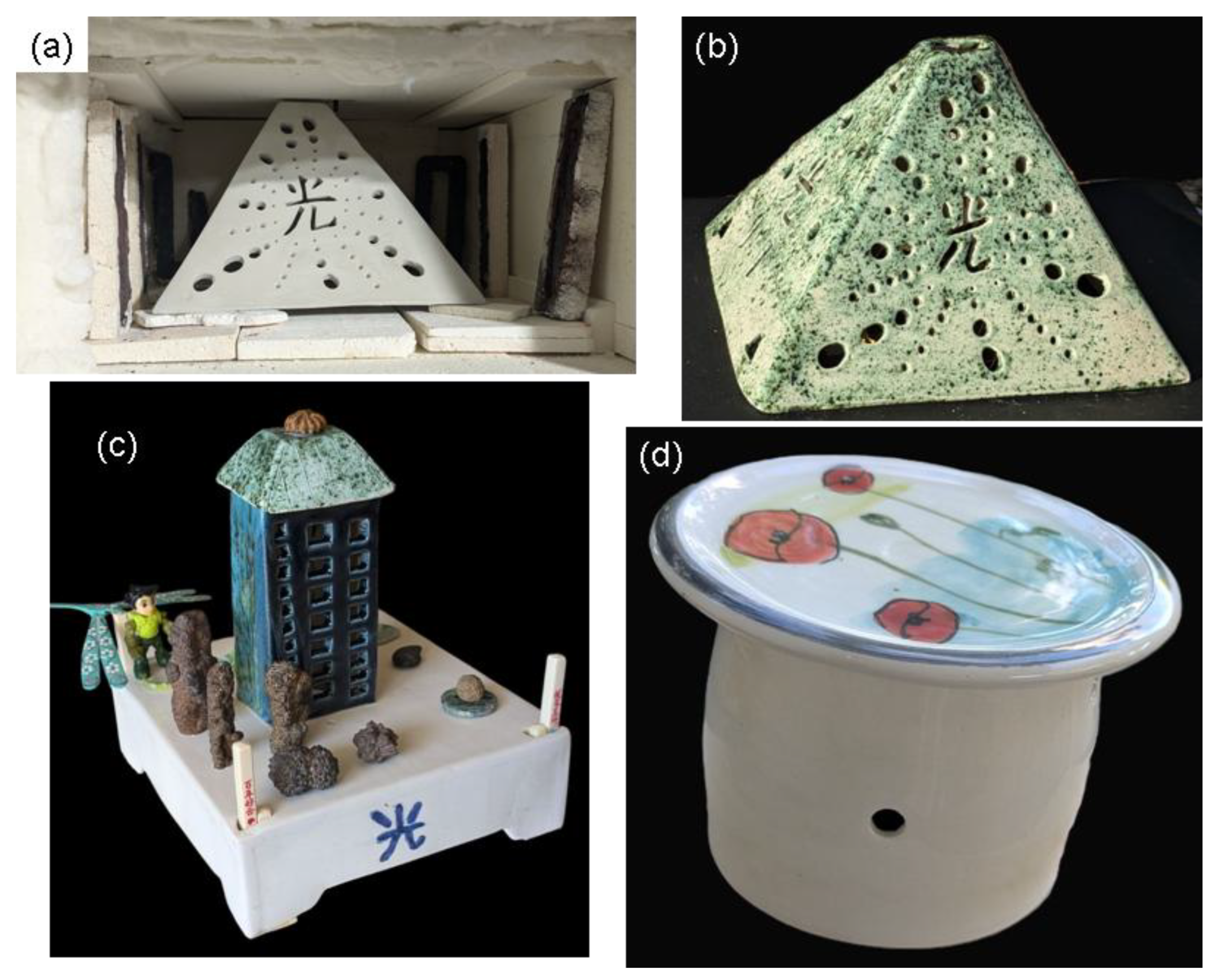

Figure 23.

Examples of Large Earthenware Pieces Successfully Fired and Glazed in a Microwave Kiln. (a): 435g pyramidal tealight holder(18x16x12 cm) in its raw state, positioned in the kiln. Six susceptors (130g), some still in their refractory mould, are arranged around the piece. (b): The same tealight hageder after a 90-minute firing at 1030 °C and a subsequent 70-minute glazing at 1030 °C. (c): A decorative set of two earthenware pieces fired and glazed separately. The base (21x16x6 cm, 765g) was fired with six susceptors (142g) in 104 minutes at 1026 °C and glazed in 73 minutes at 978 °C. The tower (17x7x5 cm, 200g) was fired with other pieces in 90 minutes at 995 °C and glazed in 67 minutes at 1020 °C. (d): Water butter dish: A 170g water butter dish (8x10 cm) fired in the same batch as the tower, in the presence of seven susceptors (160g). The water butter dish is a handcrafted creation by ceramist Caroline Combes.

Figure 23.

Examples of Large Earthenware Pieces Successfully Fired and Glazed in a Microwave Kiln. (a): 435g pyramidal tealight holder(18x16x12 cm) in its raw state, positioned in the kiln. Six susceptors (130g), some still in their refractory mould, are arranged around the piece. (b): The same tealight hageder after a 90-minute firing at 1030 °C and a subsequent 70-minute glazing at 1030 °C. (c): A decorative set of two earthenware pieces fired and glazed separately. The base (21x16x6 cm, 765g) was fired with six susceptors (142g) in 104 minutes at 1026 °C and glazed in 73 minutes at 978 °C. The tower (17x7x5 cm, 200g) was fired with other pieces in 90 minutes at 995 °C and glazed in 67 minutes at 1020 °C. (d): Water butter dish: A 170g water butter dish (8x10 cm) fired in the same batch as the tower, in the presence of seven susceptors (160g). The water butter dish is a handcrafted creation by ceramist Caroline Combes.

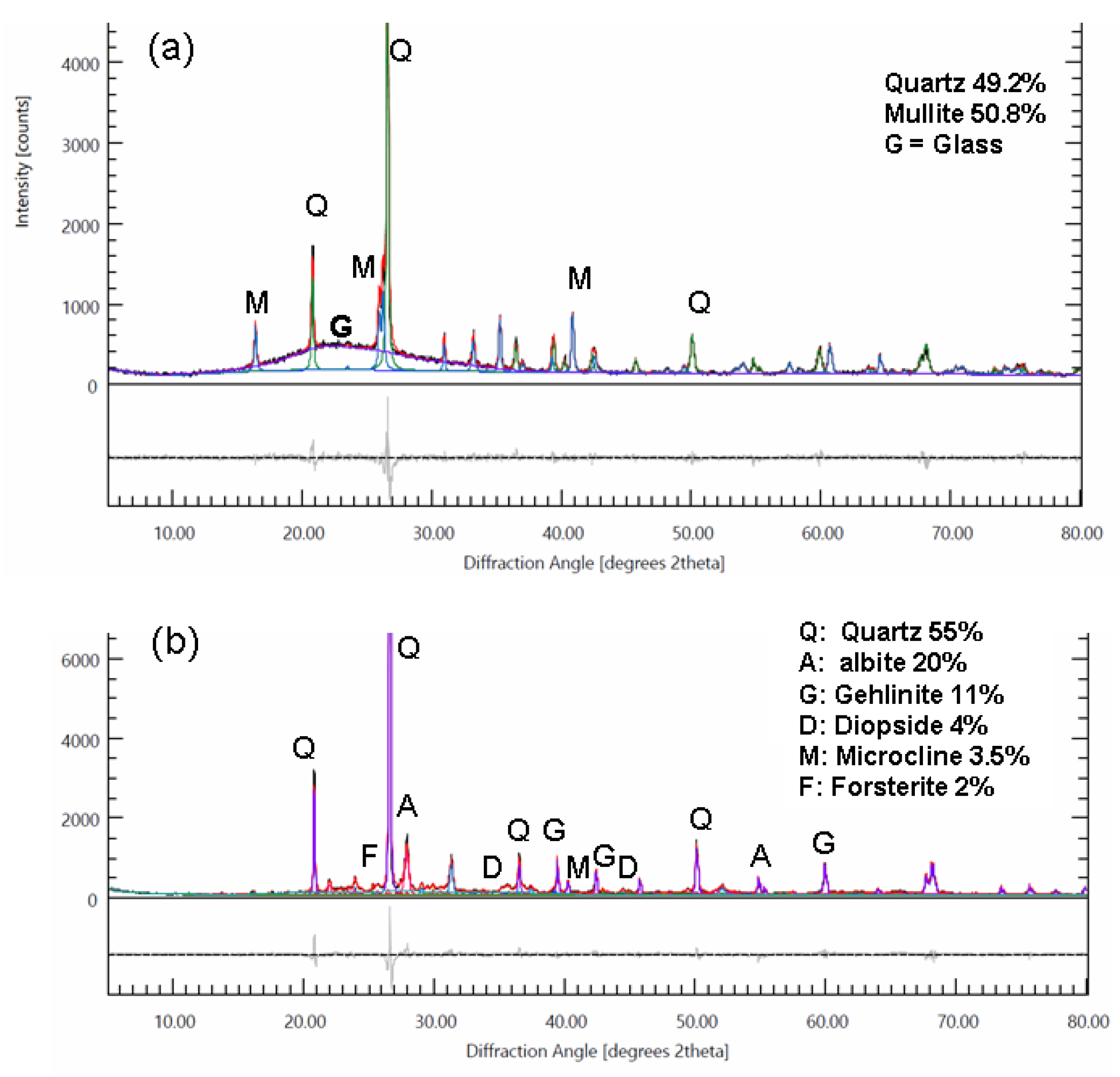

Figure 24.

X-ray diffractograms of fired earthenware and porcelain. (a) porcelain fired to 1280 °C, heating time 48mn. (b) biscuit earthenware fired to 1005 °C, heating time 66 mn. Quantitative analysis was performed using the Rietveld refinement method, and only phases present at a concentration of more 2% are listed.

Figure 24.

X-ray diffractograms of fired earthenware and porcelain. (a) porcelain fired to 1280 °C, heating time 48mn. (b) biscuit earthenware fired to 1005 °C, heating time 66 mn. Quantitative analysis was performed using the Rietveld refinement method, and only phases present at a concentration of more 2% are listed.

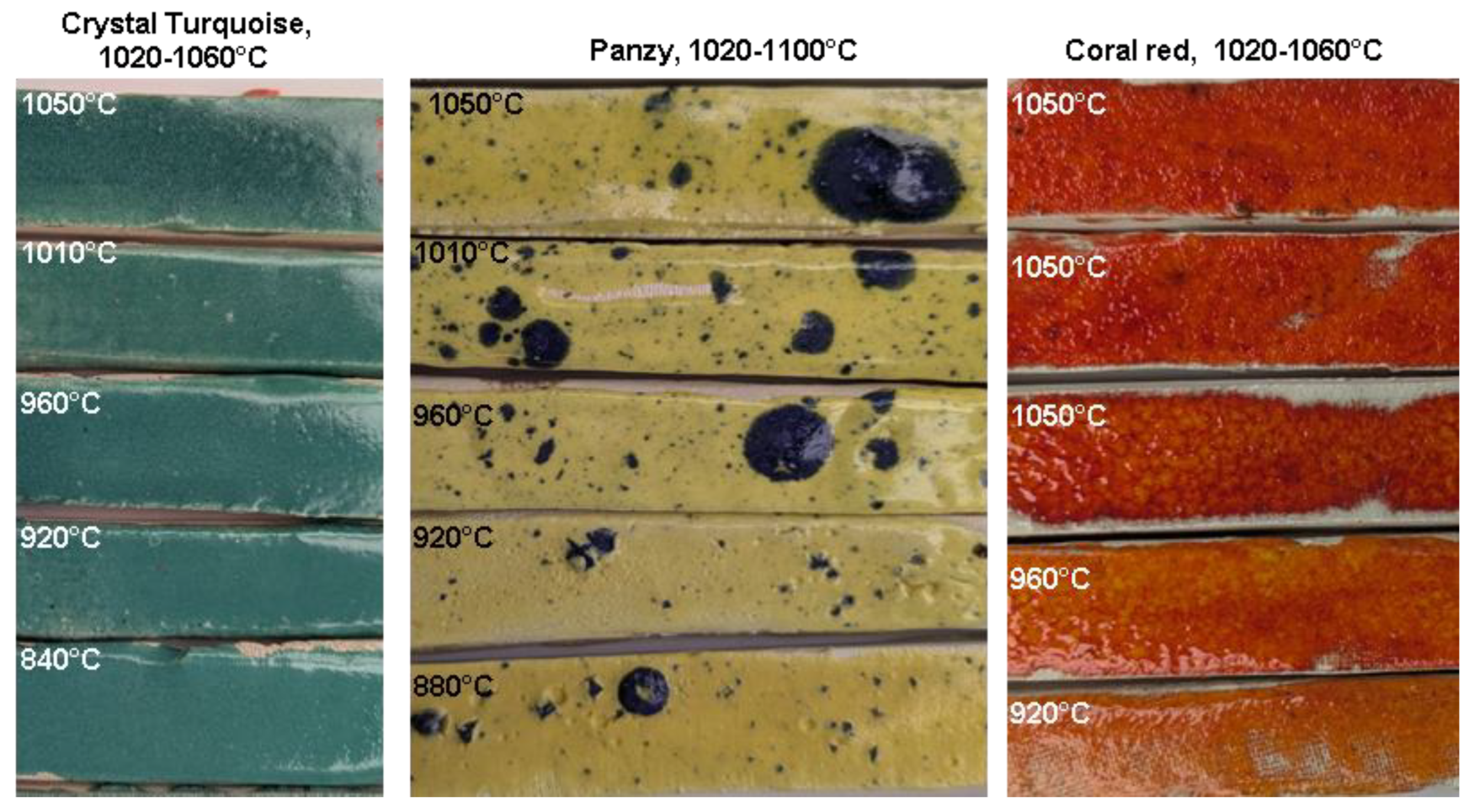

Figure 25.

Comparative photographic analysis of commercial earthenware glazes fired at different temperature in the microwave kiln. The glazes were designed for a temperature range between 1020–1060 °C (crystal turquoise and coral red) and 1020–1100 °C (panzy). Five firings, using six susceptors, of the three glaze batches were conducted on test pieces made from three types of commercial white earthenware clay. Each firing lasted between 30 and 50 minutes, depending on the target temperature, with a 10-minute plateau at the maximum temperature. The temperature was measured using a thermocouple placed in the middle of the oven, 4 cm above the pieces. The three 1050 °C glazes of coral red are on three different white commercial earthenware pastes (FDS, Loza and a common one).

Figure 25.

Comparative photographic analysis of commercial earthenware glazes fired at different temperature in the microwave kiln. The glazes were designed for a temperature range between 1020–1060 °C (crystal turquoise and coral red) and 1020–1100 °C (panzy). Five firings, using six susceptors, of the three glaze batches were conducted on test pieces made from three types of commercial white earthenware clay. Each firing lasted between 30 and 50 minutes, depending on the target temperature, with a 10-minute plateau at the maximum temperature. The temperature was measured using a thermocouple placed in the middle of the oven, 4 cm above the pieces. The three 1050 °C glazes of coral red are on three different white commercial earthenware pastes (FDS, Loza and a common one).

Figure 26.

Representative firing cycles in the large microwave kiln for porcelain and earthenware in different volume (V) configurations. (a) porcelain degourdi shown in

Figure 1e and (b) glazing earthenware shown in

Figure 23b. (c) and (d) porcelain sintering and glazing. The data is represented by three curves for each firing: The blue curve shows the temperature measured by a thermocouple. The pink curve represents the instantaneous power, manually adjusted for each microwave. The green curve shows the cumulative electrical consumption, including both the microwaves and the ventilation which works also during cooling.

Figure 26.

Representative firing cycles in the large microwave kiln for porcelain and earthenware in different volume (V) configurations. (a) porcelain degourdi shown in

Figure 1e and (b) glazing earthenware shown in

Figure 23b. (c) and (d) porcelain sintering and glazing. The data is represented by three curves for each firing: The blue curve shows the temperature measured by a thermocouple. The pink curve represents the instantaneous power, manually adjusted for each microwave. The green curve shows the cumulative electrical consumption, including both the microwaves and the ventilation which works also during cooling.

Table 1.

main types of susceptors manufactured. * only SiC is considered to calculate the Si mole fraction, the porosity is calculated as the difference between the volume of the susceptor and that of the mineral constituents.

Table 1.

main types of susceptors manufactured. * only SiC is considered to calculate the Si mole fraction, the porosity is calculated as the difference between the volume of the susceptor and that of the mineral constituents.

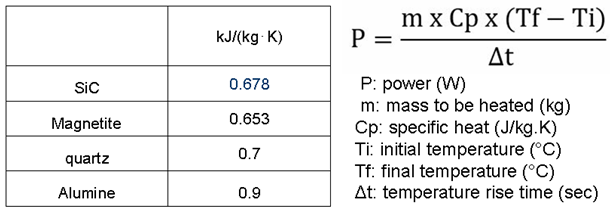

Table 2.

specific heat value for the considered minerals and calculation of adsorption power.

Table 2.

specific heat value for the considered minerals and calculation of adsorption power.

Table 3.

Average Absorption Power (W/gram) for the main batches of susceptors. The values are presented as a function of their cumulative usage time, from their initial sintering up to their final state after firing ceramics. Cumulative usage time is defined as the total heating time, not including cooling periods.

Table 3.

Average Absorption Power (W/gram) for the main batches of susceptors. The values are presented as a function of their cumulative usage time, from their initial sintering up to their final state after firing ceramics. Cumulative usage time is defined as the total heating time, not including cooling periods.

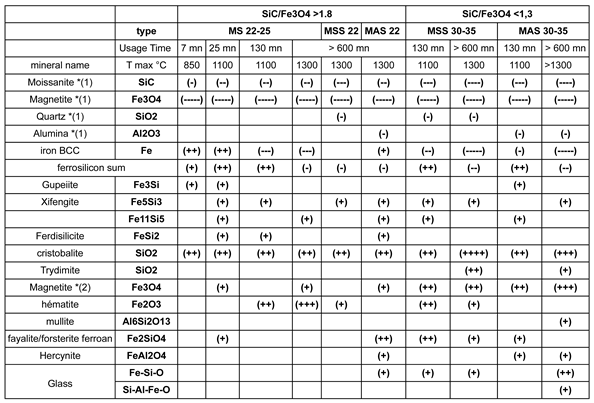

Table 4.

Mineralogical transformations of the main types of susceptors, from their sintering process to their transformation during prolonged use in ceramic heating cycles. The data are derived from the compilation of observations and analyses performed using SEM techniques: SE, BSE, EDS and EBSD imaging and characterisations, as well as powder X-ray diffraction. The symbols (+) and (-) correspond to the apparition or disappearance of a phase. The number of symbols in brackets represents an approximate intensity between 0 and 5 (100%). *(1) and *(2) indicate that the phase is primary (initial) or secondary (subsequent).

Table 4.

Mineralogical transformations of the main types of susceptors, from their sintering process to their transformation during prolonged use in ceramic heating cycles. The data are derived from the compilation of observations and analyses performed using SEM techniques: SE, BSE, EDS and EBSD imaging and characterisations, as well as powder X-ray diffraction. The symbols (+) and (-) correspond to the apparition or disappearance of a phase. The number of symbols in brackets represents an approximate intensity between 0 and 5 (100%). *(1) and *(2) indicate that the phase is primary (initial) or secondary (subsequent).

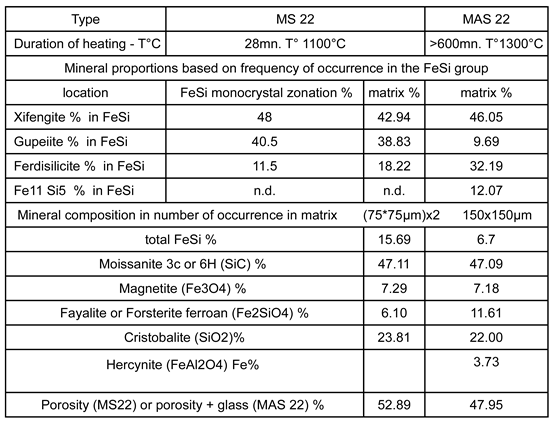

Table 5.

partial quantification of the mineralogical and porosity changes resulting from thermal cycling, comparing a just sintered susceptor (MS22 at 1100∘C,

Figure 11) with an aged one (MAS22 reaching 1300 °C,

Figure 15).

Table 5.

partial quantification of the mineralogical and porosity changes resulting from thermal cycling, comparing a just sintered susceptor (MS22 at 1100∘C,

Figure 11) with an aged one (MAS22 reaching 1300 °C,

Figure 15).

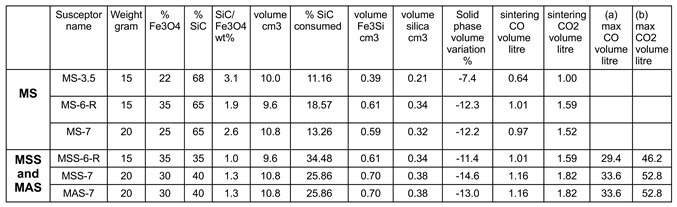

Table 6.

Stoichiometric balance following reactions R1 and R2 of the susceptor sintering reactions and its consequences on solid phase volume reduction and gas emissions as a function of material composition. (a) and (b) Calculation of the total amount of gas generated by a 150-gram susceptors assembly in the same furnace over their typical lifespan of approximately ten heating cycles in the furnace.

Table 6.

Stoichiometric balance following reactions R1 and R2 of the susceptor sintering reactions and its consequences on solid phase volume reduction and gas emissions as a function of material composition. (a) and (b) Calculation of the total amount of gas generated by a 150-gram susceptors assembly in the same furnace over their typical lifespan of approximately ten heating cycles in the furnace.