Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the standard surgical approach for gallstone disease, offering distinct advantages over open cholecystectomy, including shorter recovery times and earlier return to normal activities [

1]. Despite these benefits, LC is associated with moderate to severe postoperative pain, particularly within the first 24 hours, often necessitating opioid analgesia [

2]. High-dose opioid use, however, is frequently complicated by nausea, vomiting, dizziness, abdominal distension, and urinary retention, which may delay recovery and prolong hospitalization [

3,

4].

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols have been widely implemented to optimize perioperative care and expedite recovery. Multimodal analgesia represents a cornerstone of these protocols, aiming to minimize opioid use while maintaining effective pain control [

5,

6]. Within this framework, the subcostal transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block has emerged as a valuable component of multimodal analgesia, providing targeted pain relief following LC. When performed under ultrasound guidance using 0.25% bupivacaine, this block reliably anesthetizes thoracic (T7–T12) and lumbar (L1) nerves, thereby improving pain control and facilitating earlier mobilization [

7,

8]. Nevertheless, its dependence on anesthesiologist expertise and specialized equipment limits feasibility in certain clinical environments.

To address these limitations, the laparoscopic-guided subcostal TAP block has been developed as a surgeon-performed technique seamlessly incorporated into the operative workflow. Under direct laparoscopic visualization, local anesthetic can be precisely delivered into the transversus abdominis plane, providing consistent parietal analgesia while obviating the need for ultrasound equipment or additional personnel. This method has been demonstrated to be safe, efficient, and time-effective, offering a practical alternative for postoperative pain control following laparoscopic cholecystectomy [

9].

Nevertheless, most previous studies on laparoscopic-guided subcostal TAP block have focused on patients with uncomplicated gallstone disease under controlled trial conditions, limiting the generalizability of their findings to real-world surgical populations. Data on its performance in patients with complicated gallstone disease remain limited.

The present study aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes of surgeon-performed laparoscopic-guided subcostal TAP block for postoperative pain management in patients undergoing LC for both uncomplicated and complicated gallstone disease, including acute cholecystitis and gallstone-related pancreatitis. Additionally, perioperative factors potentially associated with postoperative opioid requirements were explored.

Materials and Methods

A single-center observational study was conducted at the Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Srinakharinwirot University, Thailand, between November 2023 and October 2024. Eligible patients were aged 18–80 years and diagnosed with cholelithiasis or gallstone-related complications, including acute cholecystitis, acute cholangitis, gallstone pancreatitis, or a history of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Patients converted to open surgery or with known bupivacaine allergy were excluded. The target sample size was 40 patients; to enhance reliability, 50 patients were enrolled.

Study Design Declaration

The initial ethics-approved protocol was designed as a randomized comparison between subcostal TAP block and port-site local infiltration. However, due to limited patient recruitment, randomization could not be executed. The present report therefore represents an observational analysis of patients who received the surgeon-performed, laparoscopic-guided subcostal TAP block in accordance with the originally approved protocol. No additional procedures, interventions, or deviations from the ethical approval were undertaken.

Ethics Approval and Registration

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Srinakharinwirot University (Ethics code: SWUEC-004/2566F). It was retrospectively registered with the Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR20250314002) in accordance with transparency recommendations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. All patient data were collected and managed according to institutional and international standards for data confidentiality and ethical research practice.

Laparoscopic-Guided Transversus Abdominis Plane (TAP) Block

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed under general anesthesia. Intraoperative analgesia was standardized according to the institutional protocol and was not analyzed separately. Before skin incision, 5 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine was infiltrated at the umbilical site for local analgesia. A 12-mm umbilical port was introduced for the laparoscopic camera, and pneumoperitoneum was established at 8 to 12 mmHg.

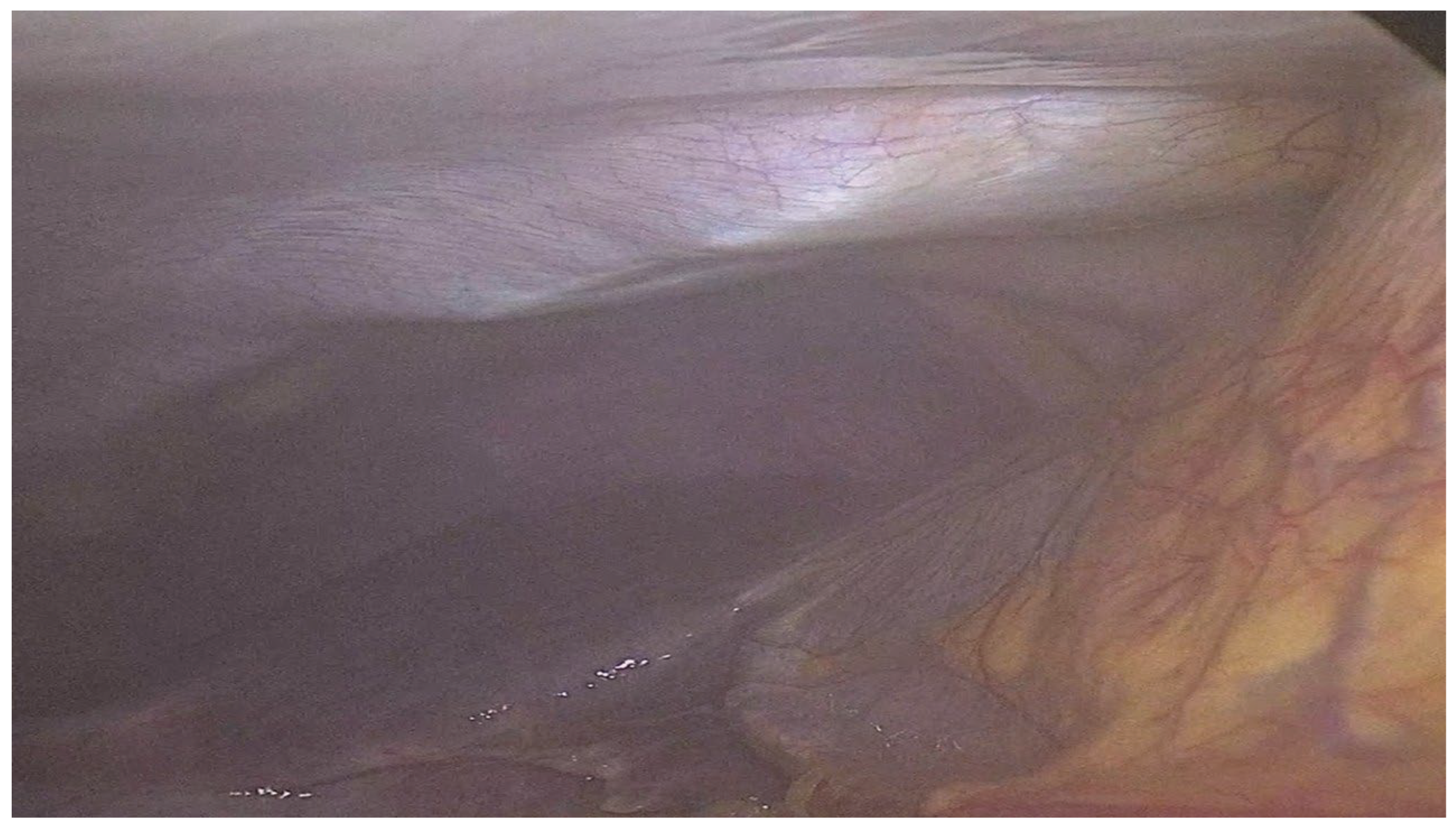

After insufflation, a laparoscopic-guided subcostal TAP block was performed using 20 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine injected into the subxiphoid area to cover the right subcostal region. The needle was advanced to the junction of the posterior rectus sheath and the transversus abdominis muscle, and correct placement was confirmed by visualization of Doyle’s bulge (

Figure 1) under laparoscopic vision, indicating accurate fascial plane infiltration as previously described [

10]. Following the block, three 5-mm ports were inserted along the right subcostal margin, and standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy was completed.

Postoperative Pain Management and Monitoring

All patients received standardized postoperative analgesia. Oral paracetamol (500 mg every 6 hours) and naproxen (250 mg twice daily) were prescribed as first-line agents; tramadol (50 mg twice daily) was substituted for patients with NSAID intolerance. Persistent pain with a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score > 5 despite oral medication was managed with intravenous morphine (0.1 mg/kg every 4 hours as needed). Ondansetron (4 mg every 8 hours as required) was given for nausea and vomiting prophylaxis.

Pain intensity was evaluated using the VAS (0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain) at 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 hours postoperatively and during mobilization. Total morphine consumption and opioid-related adverse events (nausea, vomiting, urinary retention) were recorded within the first 24 hours. Patients were observed for possible bupivacaine toxicity during this period.

Clinical Variables

Data collection included patient demographics, comorbidities, laboratory parameters, operative details, postoperative outcomes, and histopathological findings. Operative variables comprised surgical duration, estimated blood loss, and intraoperative complications.

Postoperative variables included pain scores, total morphine consumption, and postoperative complications. All data were prospectively recorded in a predesigned spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) for statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation, frequencies, and percentages) were used to summarize demographic and clinical data. Comparisons between subgroups were conducted using the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the independent t-test or one-way ANOVA for continuous variables, as appropriate.

Exploratory multivariable logistic regression was applied to assess potential associations between perioperative factors and postoperative morphine requirement, acknowledging the limited sample size. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 50 patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy during the study period. Eight cases were excluded due to conversion to open surgery, leaving 42 patients for analysis. Of these, 21 patients (50.0%) required morphine for postoperative pain management, while 21 (50.0%) did not. The mean cumulative morphine dose within the first 24 hours among patients in the morphine-required group was 3.86 ± 1.39 mg.

Patient Characteristics

The mean age did not differ significantly between the morphine-required and morphine-free groups (57.1 ± 14.1 vs. 54.3 ± 15.8 years; p = 0.553). Similarly, body mass index (25.8 ± 5.3 vs. 24.8 ± 4.9 kg/m²; p = 0.554) and sex distribution (female: 61.9% vs. 36.0%; p = 0.226) were comparable. Comorbidities were more frequent among patients who required morphine (81.0% vs. 48.0%), although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.100). The mean ASA classification was significantly higher in the morphine-required group (2.14 ± 0.57 vs. 1.67 ± 0.73; p = 0.024), suggesting a greater perioperative risk burden. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

Preoperative Laboratory Parameters

Patients in the morphine-required group had significantly lower hemoglobin (11.95 ± 1.78 g/dL vs. 13.34 ± 1.60 g/dL; p = 0.011) and hematocrit levels (35.9 ± 4.8% vs. 40.2 ± 4.0%; p = 0.002).No significant differences were found in white blood cell count (p = 0.852), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (p = 0.481), liver function tests, or albumin levels (p > 0.05). Preoperative laboratory findings are summarized in

Table 1.

Operative Details and Postoperative Outcomes

Operative characteristics did not differ significantly between groups. The mean operative time was 63.5 ± 15.6 minutes in the morphine-required group versus 58.4 ± 18.0 minutes in the morphine-free group (p = 0.328). Estimated blood loss was comparable (15.7 ± 11.3 mL vs. 13.3 ± 12.5 mL; p = 0.521). The mean length of hospital stay was 2.57 ± 0.98 days and 2.33 ± 0.86 days, respectively (p = 0.406). No significant differences were observed in postoperative complications (p = 0.441) or analgesic regimens (p > 0.05). Operative and postoperative outcomes are presented in

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Postoperative Morphine Requirement

Multivariable logistic regression identified ASA classification as the only independent predictor of postoperative morphine requirement. Patients with higher ASA scores were significantly more likely to require morphine within 24 hours after surgery (p = 0.018, OR = 6.51, 95% CI: 1.37–30.96). Although hemoglobin showed a negative association with morphine use, this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.076, OR = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.32–1.06). Other variables including sex, age, gallstone-related complications, and history of ERCP were not significantly associated (all p > 0.05).

Due to the limited number of outcome events, the multivariable model was performed under an exploratory framework constrained by events-per-variable (EPV) considerations. A summary of the regression analysis is provided in

Table 3.

Comparison of Postoperative Pain Scores Between Groups

Patients who required morphine reported significantly higher pain scores during the early postoperative period, particularly at 2 hours (3.29 ± 1.45 vs. 1.93 ± 0.96, p = 0.009),4 hours (3.95 ± 1.39 vs. 2.07 ± 1.00, p < 0.001), and12 hours (3.57 ± 1.44 vs. 2.43 ± 1.06, p = 0.021). At 6 hours (p = 0.261), 24 hours (p = 0.078), and during mobilization (p = 0.406), pain scores remained numerically higher in the morphine-required group but were not statistically significant.

These findings suggest that the subcostal TAP block provides effective early postoperative analgesia, although patients with higher ASA class (≥II) may still experience greater pain intensity and opioid demand. Pain score comparisons are summarized in

Table 4.

Discussion

This prospective observational study suggests a clinically relevant opioid-sparing association of laparoscopic-guided subcostal TAP block in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Half of the patients required no postoperative opioids, and those who did received only a modest cumulative dose (mean 3.86 mg). The postoperative analgesic effect was most evident between 2 and 12 hours, consistent with the pharmacodynamic duration of 0.25% bupivacaine. These findings support the use of surgeon-performed TAP block as a practical adjunct to multimodal analgesia, thereby minimizing opioid use while maintaining effective postoperative pain control [

11,

12,

13,

14].

The results are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that thoracoabdominal and subcostal TAP blocks improve early postoperative pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy [

15,

16,

17]. Our findings align with the randomized trial by Emile et al., which reported comparable analgesic efficacy and opioid reduction between ultrasound- and laparoscopic-guided approaches [

18]. This study further extends the evidence base by including patients with complicated gallstone disease, a population underrepresented in earlier research.

Mechanistically, this effect likely reflects localized somatic blockade of the upper abdominal wall corresponding to trocar insertion sites. Such coverage attenuates incisional and parietal peritoneal pain, explaining the pronounced reduction in pain scores during the first 12 postoperative hours [

10,

19]. Clinically, these findings highlight the importance of scheduled non-opioid co-analgesics and timely rescue dosing to sustain analgesia within ERAS-oriented protocols [

5,

6,

13,

14].

Predictor analysis revealed that patient-related factors exerted a greater influence on opioid requirement than intraoperative variables. Higher ASA classification independently predicted postoperative morphine use, suggesting that systemic comorbidities and reduced physiologic reserve may heighten analgesic needs despite regional blockade. These associations indicate that comorbidity burden and physiologic reserve shape analgesic demand, supporting risk-stratified analgesic planning and the consideration of extended-duration local anesthetic strategies for high-risk patients.

Beyond its analgesic efficacy, the surgeon-performed subcostal TAP block provides distinct practical advantages in environments with limited anesthesiology support or ultrasound availability. Integrating this technique into the laparoscopic workflow enables consistent, equipment-independent regional analgesia, aligning with global initiatives in opioid stewardship and sustainable ERAS implementation [

9,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The approximately 50% reduction in postoperative opioid utilization observed in this cohort further underscores its feasibility and potential clinical impact in such settings.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The single-center, non-randomized design limits causal inference, and the absence of a control group precludes direct comparison with standard local anesthetic port-site infiltration. Nevertheless, the findings are consistent with controlled studies, supporting the external validity of the results. The modest sample size limited statistical precision: therefore, multivariable analysis was performed under an exploratory framework with selective variable inclusion to minimize overfitting and enhance robustness.

The lack of sensory testing prevented objective verification of block success, and substitution of tramadol for NSAIDs in a few cases may have introduced minor confounding, although analgesic regimens were otherwise standardized. Psychosocial factors such as anxiety, catastrophizing, and prior opioid exposure were not assessed, despite their known influence on postoperative pain [

20,

21,

22]. Despite these constraints, the use of prospective data collection, standardized pain assessments, and appropriate statistical adjustments strengthens the internal validity of the present findings.

The study’s strengths include its prospective design, standardized pain assessment, and inclusion of both uncomplicated and complicated gallstone disease, enhancing clinical applicability. The findings suggest that surgeon-performed, laparoscopic-guided subcostal TAP block is a safe, feasible, and reproducible adjunct to multimodal analgesia, particularly in settings with limited anesthesiology resources. Its early opioid-sparing effect supports potential integration into ERAS pathways and ongoing opioid-reduction strategies [

23].

Future research should involve multicenter randomized controlled trials comparing laparoscopic-guided TAP block with standard port-site infiltration. Based on current effect estimates, a sample size of approximately 80–100 patients per arm would provide 80% power to detect a 1-point difference in mean VAS pain score at an α level of 0.05. Incorporating cost-effectiveness analysis, patient-reported outcomes, and long-term follow-up will further establish the efficacy, scalability, and clinical value of this technique in minimally invasive surgery.

Conclusions

This study suggests that laparoscopic-guided subcostal TAP block may reduce early postoperative pain and opioid use in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, including those with gallstone-related complications. Higher ASA classification was associated with greater opioid requirements, underscoring the need for individualized, risk-adapted analgesic strategies. Despite the limited sample size, these findings support the feasibility and potential clinical utility of integrating surgeon-performed subcostal TAP block into ERAS pathways to enhance multimodal analgesia and postoperative recovery.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors

Ethical Statements

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Srinakharinwirot University (Ethics code: SWUEC-004/2566F). The original protocol planned a randomized comparison; however, due to limited patient recruitment, randomization was not performed, and the study was conducted instead as an observational analysis within the approved scope. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was retrospectively registered with the Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR20250314002) after study initiation, in accordance with transparency recommendations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the surgical staff at the Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Srinakharinwirot University, for their assistance in data acquisition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) to improve grammar and language clarity. After using this tool, the authors carefully reviewed, revised, and approved the content, and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

References

- Tullavardhana, T. Critical view of safety: a safe method to prevent bile duct injury from laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Med Health Sci. 2015; 22:49-57.

- Keir A, Rhodes L, Kayal A, Khan OA. Does a transversus abdominis plane (TAP) local anaesthetic block improve pain control in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy? A best evidence topic. Int J Surg. 2013; 11:792-4. [CrossRef]

- Tan M, Law LS, Gan TJ. Optimizing pain management to facilitate enhanced recovery after surgery pathways. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62(2):203-18. [CrossRef]

- Law LS, Lo EA, Gan TJ. Preoperative antiemetic and analgesic management. In: Gan TJ, Thacker JK, Miller TE, et al., editors. Enhanced recovery for major abdominopelvic surgery. West Islip (NY): Professional Communications, Inc.; 2016. p. 105-20.

- Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(3):292-8. [CrossRef]

- Kaye AD, Urman RD, Rappaport Y, Siddaiah H, Cornett EM, Belani K, et al. Multimodal analgesia as an essential part of enhanced recovery protocols in the ambulatory settings. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2019;35(Suppl 1): S40-5.

- Hebbard P, Fujiwara Y, Shibata Y, Royse C. Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35(4):616-7. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Wang L, Gao Y. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials concerning the efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block for pain control after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Front Surg. 2021; 8:700318. [CrossRef]

- Elamin G, Waters PS, Hamid H, O’Keeffe HM, Waldron RM, Duggan M, et al. Efficacy of a laparoscopically delivered transversus abdominis plane block technique during elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective, double-blind randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(2):335-44. [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman R, Saravanan R, Dhas M, Pushparani A. Comparison of laparoscopy-guided with ultrasound-guided subcostal transversus abdominis plane block in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective, randomised study. Indian J Anaesth. 2020;64(12):1012-7. [CrossRef]

- Campiglia L, Consales G, De Gaudio AR. Pre-emptive analgesia for postoperative pain control: a review. Clin Drug Investig. 2010;30 Suppl 2:15-26. [CrossRef]

- Simpson JC, Bao X, Agarwala A. Pain management in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32(2):121-8. [CrossRef]

- Cao L, Yang T, Hou Y, Yong S, Zhou N. Efficacy and safety of different preemptive analgesia measures in pain management after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Ther. 2024;13(4):1471-97. [CrossRef]

- Barazanchi AWH, MacFater WS, Rahiri JL, Tutone S, Hill AG, Joshi GP, et al. Evidence-based management of pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a PROSPECT review update. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121(4):787-803. [CrossRef]

- Cho HY, Hwang IE, Lee M, Kwon W, Kim WH, Lee HJ. Comparison of modified thoracoabdominal nerve block through perichondral approach and subcostal transversus abdominis plane block for pain management in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Korean J Pain. 2023;36(3):382-91. [CrossRef]

- Tolchard S, Davies R, Martindale S. Efficacy of the subcostal transversus abdominis plane block in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: comparison with conventional port-site infiltration. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012;28(3):339-43. [CrossRef]

- Ozciftci S, Sahiner Y, Sahiner IT, Akkaya T. Is right unilateral transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block successful in postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Int J Clin Pract. 2022; 2022:2668215. [CrossRef]

- Emile SH, Elfeki H, Elbahrawy K, Sakr A, Shalaby M. Ultrasound-guided versus laparoscopic-guided subcostal transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block versus no TAP block in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Int J Surg. 2022; 101:106639. [CrossRef]

- Boonyapalanant C, Woranisarakul V, Jitpraphai S, Chotikawanich E, Taweemonkongsap T, KC HB. The efficacy of inside-out transversus abdominis plane block vs local infiltration before wound closure in pain management after kidney transplantation: a double-blind, randomized trial. Siriraj Med J. 2022;74(4):233-8. [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs-Rocker A, Schulz K, Järvinen I, Lefering R, Simanski C, Neugebauer EA. Psychosocial predictors and correlates for chronic post-surgical pain: a systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(7):719-30. [CrossRef]

- Ip HY, Abrishami A, Peng PW, Wong J, Chung F. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2009;111(3):657-77. [CrossRef]

- Riddle DL, Wade JB, Jiranek WA, Kong X. Preoperative pain catastrophizing predicts pain outcome after knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(3):798-806. [CrossRef]

- Cao L, Yang T, Hou Y, Yong S, Zhou N. Efficacy and Safety of Different Preemptive Analgesia Measures in Pain Management after Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Ther. 2024 Dec;13(6):1471-1497. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).