Introduction

Postoperative pain is a significant factor affecting the recovery of surgical patients, leading to restricted movement, delayed oral intake, and an increased risk of chronic postoperative pain, which in turn prolongs ho spital stays and decreases quality of-life [

1]. Colorectal cancer is a common gastrointestinal malignancy world wide, and laparoscopic resection has become the primary treatment modality [

2]. Although laparoscopic-surgery causes less trauma compared to traditional open surgery, patients still experience significant somatic and visceral pain, particularly in the early postoperative period, which severely impacts recovery. With the widespread adoption of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (E RAS) protocols, effective perioperative pain management aimedat accelerating recovery has become a clinical priority [

3].

Opioid analgesics have long been the cornerstone of perioperative pain management, but their use is cons trained by several side effects, including respiratory d epression, nausea and vomiting, pruritus, gastrointestinal motility suppression, and immune suppression, wh ich may also promote tumor recurrence and metastas is. Therefore, reducing opioid usage has become an i mportant goal within the ERAS pathway [

4,

5]. Multimodal analgesia is widely recommended, with regional nerve blocks as a core component due to their ability to reduce opioid consumption and improve postoperative recovery.

Transversus Abdominis Plane Block (TAPB)-is a classic abdominal wall nerve block that effectively alleviates s omatic pain. Quadratus Lumborum Block (QLB) is believedto be superior to TAPB because local anesthetics spread along the thoracolumbar fascia to the paravertebral space, providing both somatic and visceral pain relief [

6,

7]. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have sugg hemodynamics. However, most studies to date have beensingle-center designs with small sample sizes, and there is a lack of multicenter evidence [

8]. Therefore, this study employs a two-center, prospective, randomized controlled trial design with propensity score matching (PSM) analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of QLB and TAPB in laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery, aiming to provide more robust clinical evidence.

Methods

Study Design and Ethics

This two-center, prospective, randomized controlled tri al was conducted with patients undergoing elective la paroscopic colorectal cancer surgery at Huaibei People' s Hospital (Center 1) and Xuzhou New Health Hospital (Center 2) from January 2022 to June 2024. The st udy protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of both centers (XXJKLL-202411-122-5), and all patients provided written informed consent. This study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant medical ethical guidelines.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (1) age 18-80 years, (2) ASA classification I-II, and (3) scheduled for elective laparoscopic sigmoid colon or rectal cancer resection. Exclusion criteria included: (1)allergy to local anesthetics or contraindications for peripheral nerveblocks, (2) long-term opioid or corticosteroid use, (3) BMI < 18 kg/ m² or>35 kg/m²,(4) severe heart, liver, or kidney dysfunction or neurological diseases, and (5) intraoperative conversion to open surgery or reoperation.

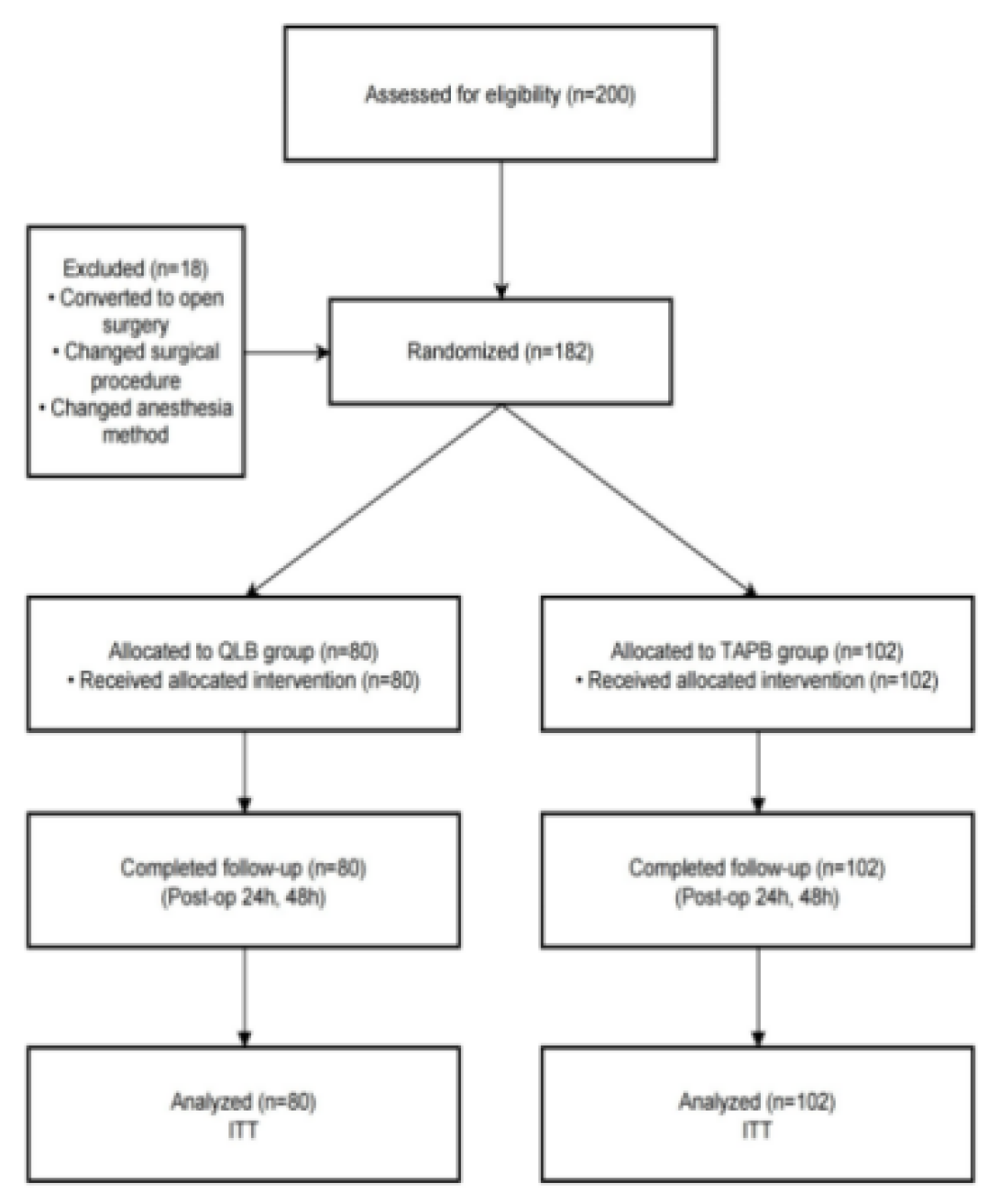

Randomization and PSM

A total of 200 patients were initially enrolled (115 fr om Center 1 and 85 from Center 2). After excluding those who did not meet the inclusion criteria, 182 patients were finally included (80 in the QLB group and 102 in the TAPB group). The study flow is shown in F igure 1. All patients signed a written informed consent. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were rand omly assigned to two groups based on computer-generated randomization. In the QLB group, lateral QLB was performed under ultrasound guidance with 40 mL of 0.375% ropivacaine, with 20 mL injected on each side. In the TAPB group, the same dose of ropivacaine was used for bilateralTAP blocks. Except for the anesthesiologist performing the blocks, the patients, o thermedical team members, data collectors, and post operative assessors were blinded to the group assignments.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of patient allocation and follow-up.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of patient allocation and follow-up.

Anesthesia Management

All patients rfeceived an intramuscular injection of 0.5 mg atropine 30 minutes before surgery to reduce gla ndular secretion and prevent cardiovascular adverse e vents. Upon entering the operating room, routine mo nitoring was performed, including electrocardiogram, n on-invasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and BIS m onitoring.

Anesthesia Induction:

Intravenous midazolam 0.04 mg/kg, etomidate 0.25 m g/kg, and sufentanil 0.5 µg/kgwere administered for i nduction. After thedisappearance of the eyelash reflex , rocuronium 0.6 mg/kg was given for endotracheal intubation [

9].

Anesthesia Maintenance:

Sevoflurane was used for maintenance to maintain BI S between 40 and 60, with continuous infusion of re mifentanil at a dose of 0.1–0.25 µg·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹, adjuste d according to mean arterial pressure (MAP). Intermit tent doses of rocuronium were added to maintain m uscle relaxation. Strict perioperative volume managem ent was followed, and in case of severe hypotension orhypertension (greater than ±30% from baseline), vas opressors or antihypertensive drugs were administered

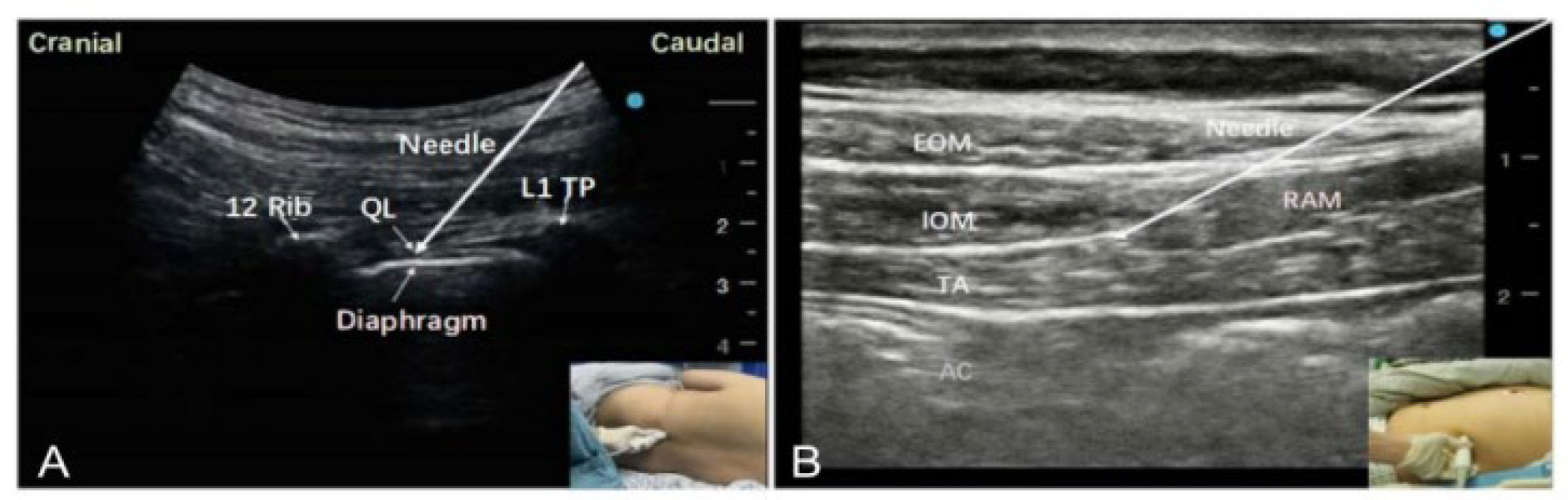

Nerve Block Procedures:

After anesthesia induction, the nerve blocks were per formed by experienced anesthesiologists. In the QLB group, patients were placed in the supine position, a nd the ultrasound probe was positioned at the iliac c rest level to visualize the external oblique, internal o blique, and transversus abdominis muscles. The probe was then moved posteriorly to visualize the quadratus lumborum muscle. A 21G needle was inserted in th e plane, and 20 mL of 0.375% ropivacaine was inject ed in front of the quadratus lumborum fascia on eac h side, for a total of 40 mL. Successful block was-ind icated by uniform spread of local anesthetic over the quadratus lumborum muscle surface, as shown in

Figure 2A. In the TAPB group, the probe was placed alo ng the midaxillary line between the iliac crest and th e 12th rib to visualize the three-layer muscle structure. The needle was inserted into the plane between t he internaloblique and transversus abdominis muscles, and 20 mL of 0.375% ropivacaine was injected on ea ch side, for a total of 40 mL. Successful block was in dicated by the local anesthetic spreading in a spindle shape over the surface of the transversus abdominis muscle, as shown in

Figure 2B.

Postoperative Analgesia:

After surgery, all patients received a sufentanil patien t-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump (2 µg/kg diluted to 100 mL, with a basal rate of 2 mL/h, on-demand bol us of2 mL, and a lockout time of 15 minutes). If nece ssary, intravenous flurbiprofen axetil50 mg was admini stered as rescue analgesia. If additional pain relief wa s needed (despite using the PCA device, when VAS s core ≥4), 50 mg of flurbiprofen axetil was administer ed over 30 minutes [

10].

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 25.0. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as m ean ± standard deviation and compared using indepe ndent t-tests. Non-normally distributed data were pre sented as median (Q1, Q3) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were presented as frequency (%), and comparisons were perfor med using chi-square tests or Fisher's exacttest. Prop ensity score matching (PSM)was performed to adjust for confounders,and standardized mean differences (S MD) wereused to assess balance [

11]. A P-value <0.05 w as considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Enrollment and Matching

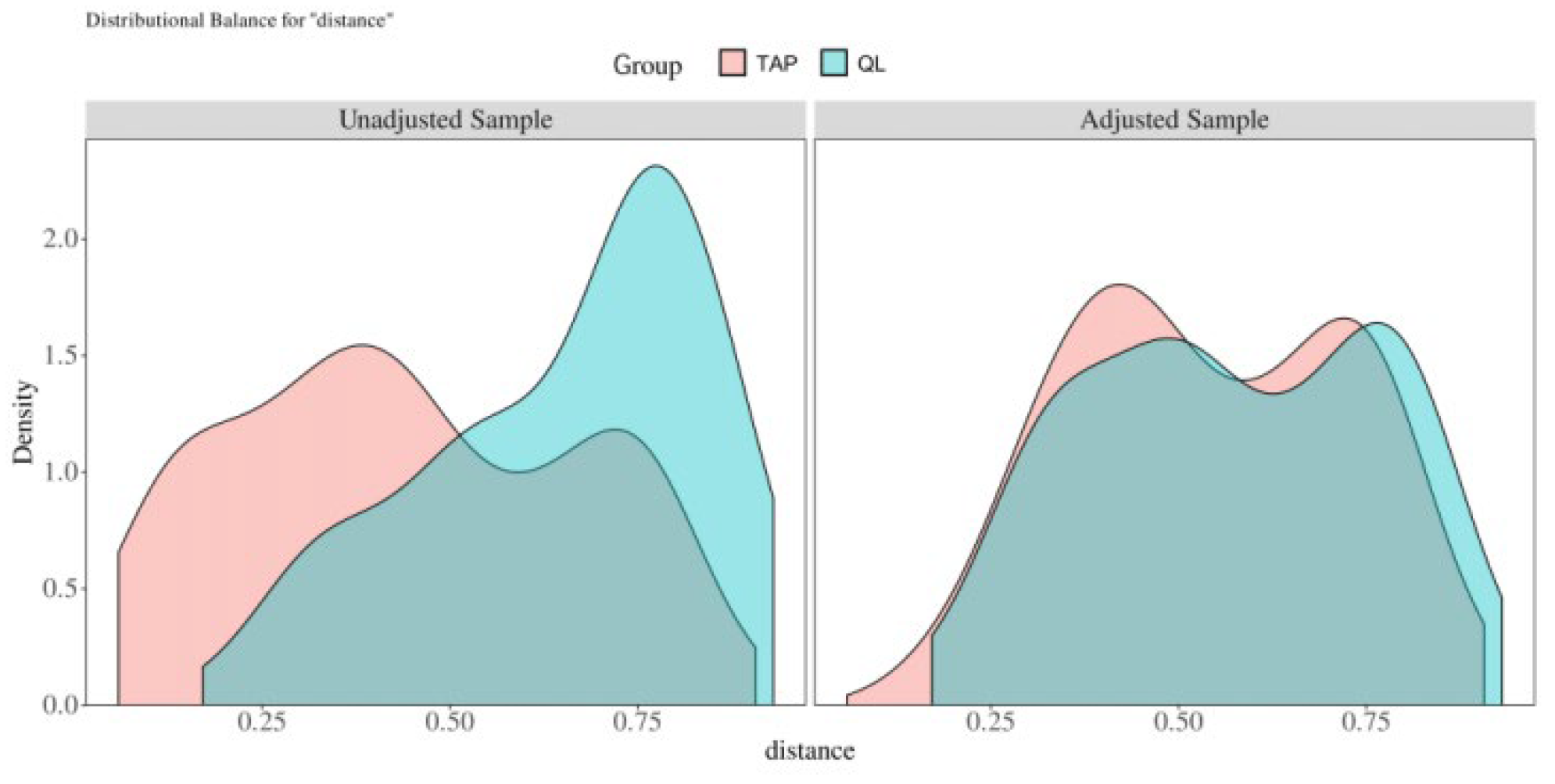

A total of 200 patients were initially screened, with 18 patients excluded due to conversion to open surg ery or changes in anesthesia methods, leaving 182 pa tients who completed randomization (QLB group:80, T APB group: 102). After propensity score matching (PS M), 114 patients (57 in the QLB group and 57 in the TAPB group)were included in the final analysis. As sh own in

Table 1, before matching, there were significa nt differences between the QLB group (n = 80) and TAPB group (n = 102) in several baseline variables. A ge, body mass index (BMI), and duration of surgery did not show significant differences between the two groups (t-values were 1.459, -0.210, and Z-value -0.27 5, with P-values of 0.146, 0.834, and 0.783, respectiv ely). However, there were significant differences in ge nder, and the proportion of patients with hypertensio n and diabetes. Specifically, the TAPB group had a si gnificantlyhigher proportion of female patients thanthe QLB group (χ² = 3.990, P = 0.046), and the incidence of hypertension and diabetes was also significantly hi gher in the TAPB group (χ² = 18.758, P < 0.001; χ² = 13.954, P < 0.001). After performing PSM,thedifferenc es between the QLB group (n= 57) and TAPB group ( n = 57) in all variables were balanced. There were no significant differences in age, BMI, surgery duration, gender, the incidence of hypertensionand diabetes, co ronary artery disease, or ASA classification (P > 0.05). The distribution of surgery type (rectal resection vs. s igmoid resection) also showed no significant differenc es (χ² = 0.576, P = 0.448). Allstandardized mean diffe rences (SMD) were< 0.1, indicating good balance bet ween the two groups (

Figure 3A) . The density distrib ution graph further shows that after matching, the t wo groups' propensity scores were highly overlapped (

Figure 3B), providing reliable grounds for subsequent analyses.

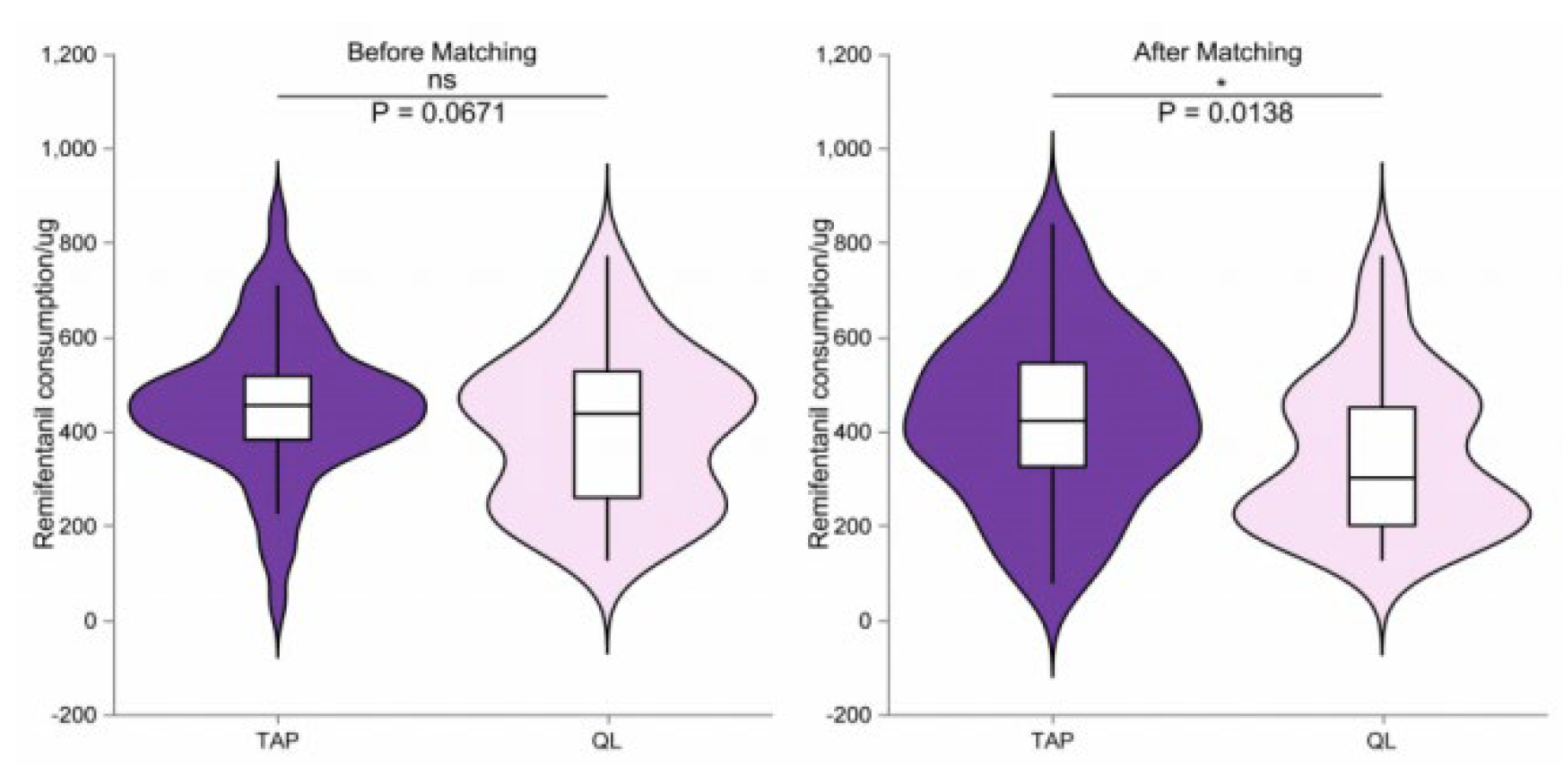

Comparison of Remifentanil Consumption

Figure 4 shows the remifentanil consumption in the QLB and TAPB groups before and after propensity sc ore matching. Before matching (A), there was no sign ificant difference in remifentanil consumption between the two groups (P = 0.0671). However, after matchin g (B), the QLB group used significantly less remifenta nil than the TAPB group (P = 0.0138), indicating thatt he QLB group required less opioid analgesia during s urgery. This difference is likely due to the effective p ain control providedby the QLB, leading to reduced o pioid demand.

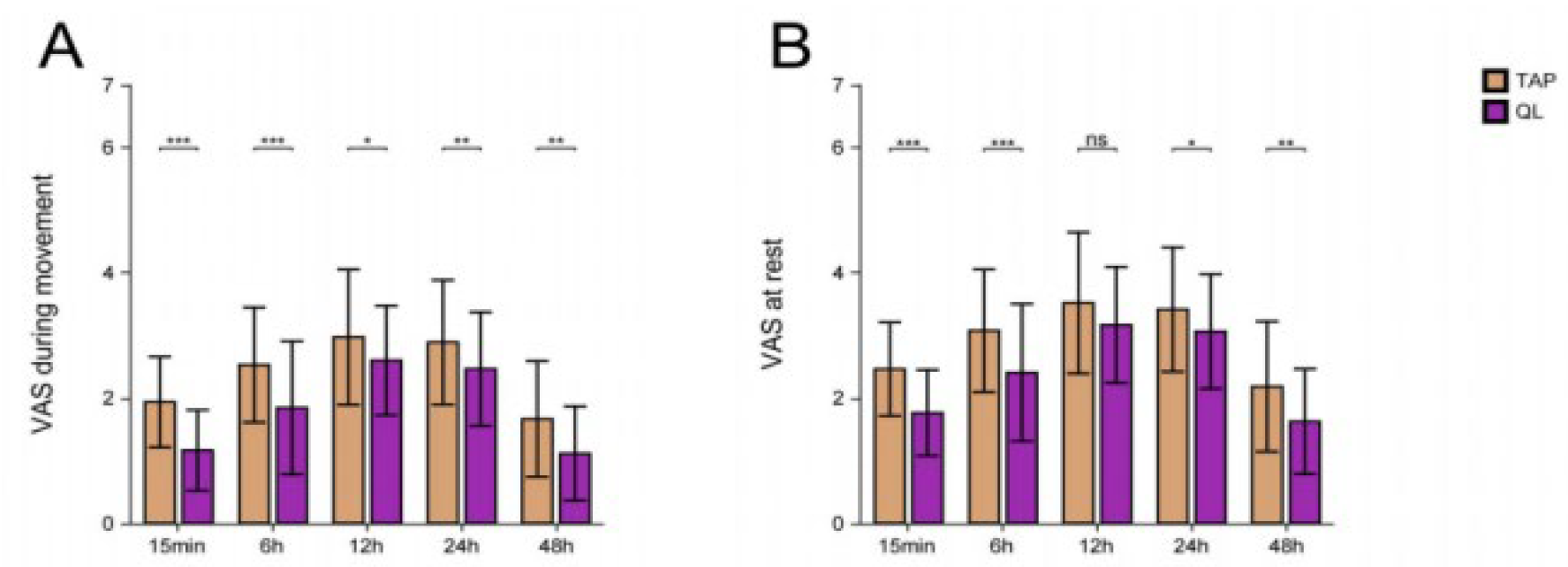

Postoperative Pain Intensity

Figure 5 presents the visual analog scale (VAS) scores for pain at various time points, both at rest (B) and during activity (A). Panel A shows the VAS scores duri ng activity, where the QLB group had significantly lo wer scores than the TAPB group at 15 minutes, 6 ho urs, and 12 hours post-surgery (***P < 0.001, *P < 0 .05). However,the differences between the groups we re smaller at 24 and 48 hours post-surgery. Panel B displays the VAS scores at rest, where the QLB group similarly reported significantly lower scores than the TAPB group at 15 minutes, 6 hours, and 12 hours po st-surgery (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01). By 24 and 48 h ours post-surgery, the difference was no longer signifi cant (ns indicates no significant difference). These res ults indicate that QLB provides more effective early p ostoperative pain relief, particularly during activity, co mpared to TAPB.

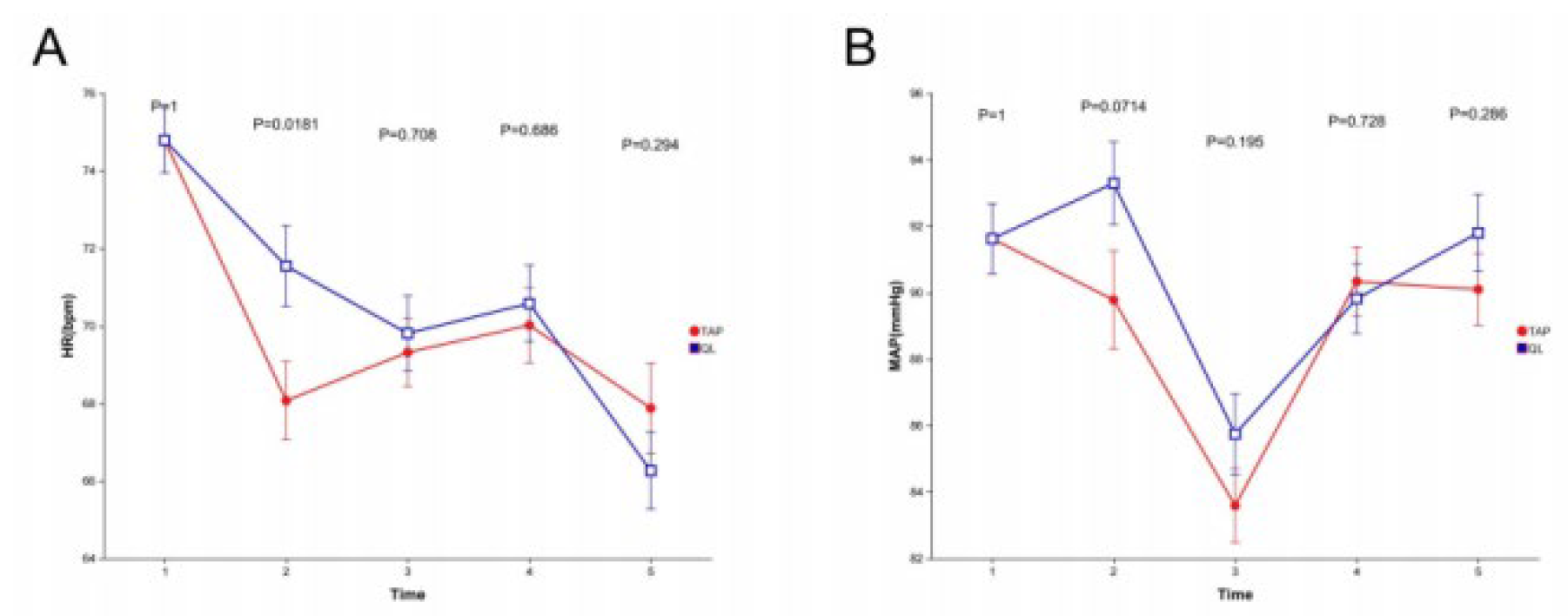

HR and MAP Changes

Figure 6 shows the changes in heart rate (HR) (A) and mean arterial pressure (MAP) (B) at different time points in the QLBand TAPB groups. Panel A shows the HR chang- es during surgery, where there wereno significant differ- ences between the groups at most time points (time points 2, 3, and 5) (P-values of 0.0181, 0.708, 0.686,and 0.294, respectively). However, at timepoint 2 (gas insuffla- tion), the HR in the QLB group was significantly lower than in the TAPB group (P = 0.0181). Panel B shows the changes in MAP, where there were also differences between the groups, although no significant differences were observed at time points 1, 3, 4, and 5 (P-values of 1, 0.195, 0.728, and 0.286, respectively). At time point 2 (gas insufflation), the MAP was lower in the QLB group compared to the TAPB group (P = 0.0714). These results suggest that QLB may help stabilize hemodynamics during surgery, particu- larly during gas insufflation, where theQLB group showed more stable heart rateand MAP levels than the TAPB group.

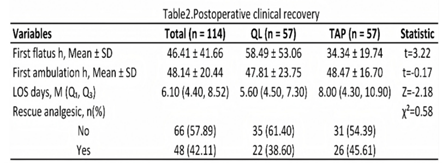

Postoperative Clinical Recovery

Table 2 shows postoperative recovery data for the 11 4 patients in the study. The first flatus time was sign ificantly longer inthe QLB group (58.49 ± 53.06 hours ) compared to the TAPB group (34.34 ± 19.74 hours) (t = 3.22, P = 0.002). However, the time to first am bulation showed no significant difference between the groups, with the QLB group ambulating at 47.81 ± 2 3.75 hours and the TAPB group at 48.47± 16.70 hour s (t = -0.17, P = 0.864). The length of hospital stay (LOS) was significantly shorter in the QLB group, with a median LOS of 5.60 days ( Q₁, Q₃: 4.50, 7.30days) compared to the TAPB group, whichhad a median LOS of 8.00 days (Q₁, Q₃: 4.30, 1 0.90 days) (Z = -2.18, P = 0.029).

The proportion of patients requiring rescue analgesia showed no significant difference, with 38.60% in the QLB group and 45.61% in the TAPB group (χ² = 0.58, P =0.448).

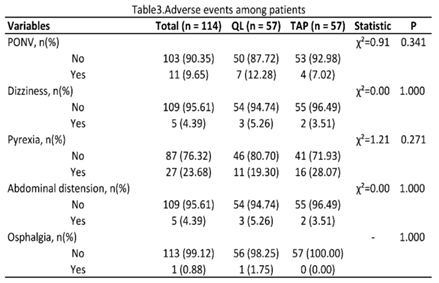

Postoperative Adverse Events

Table 3 shows the incidence of postoperative adverse events, including nausea and-vomiting (PONV), dizziness, fever, abdominal distension, and sore throat. The o verall incidence of PONV was 9.65%, with 12.28% of patients in the QLB group and 7.02% in the TAPB gr oup experiencing PONV,but this difference was not st atistically significant (χ² = 0.91, P = 0.341). The incide nce of dizziness was 5.26% in the QLB group and 3.5 1% in the TAPB group, with no significant difference (χ² = 0.00, P = 1.000). The incidence of fever was 19 .30% inthe QLB group and 28.07% in the TAPBgroup, but the difference was not significant (χ² = 1.21, P = 0.271). The incidence ofabdominal distension was 5.2 6% in the QLB group and 3.51% in the TAPB group, with no significant difference (χ² = 0.00, P= 1.000). T he incidence of sore throat was 1.75% in the QLB gr oup and 0% in theTAPB group, with no significant dif ference (P = 1.000).

Discussion

This study, based on a two-center, prospective, rando mized controlled trial (RCT) design with propensity sc ore matching (PSM), compared the analgesic effects a nd perioperative recovery outcomes of ultrasound-gui ded lateral quadratus lumborum block (QLB) and tran sversus abdominis plane block (TAPB) in laparoscopic colorectal cancersurgery. The results indicated that QL B reduced the intraoperative remifentanil consumption and provided better early postoperative pain relief th an TAPB. However, QLB was associated with a delaye d first flatus time, while significantly reducing the len gth of hospital stay. These findings suggest that QLB has potential clinical advantages within the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) pathway [

12,

13].

Regional nerve blocks have long been a core compon ent of multimodal analgesia, which effectively reduces opioid use and improves postoperative recovery. Bai et al.in a single-center RCT found that the QLBgroup used significantly less remifentanil than the TAPB and control groups,while there was no significant differenc e between the TAPB and control groups. Our study’s multicenter results are highly consistent with their fin dings and further validated this conclusion through PS M.

In terms of postoperative pain relief, research demo nstrated that both QLB and TAPB significantly reduce d pain within the first 6 hours post-surgery, with differencesmainly observed in the early postoperative per iod, diminishing after 24 hours [

14,

15]. Our study also sh owed that QLB significantly reduced VAS pain scores at 15 minutes and 6 hours post-surgery, compared to TAPB, with no significant differences at 24 and 48 ho urs post-surgery. This further supports the notion tha t QLB provides more effective early postoperative pai n relief, likely due to its mechanism of action, where the local anesthetic spreads to the paravertebral spac e,blocking the sympathetic nervous system and reduci ng visceral pain.

The innovative aspect of our study lies inthe finding that the QLB group had a significantly delayed first fl atus time, but a significantly shorter hospital stay [

16]. T his result differs somewhat from previous literature. Possible mechanisms include [

17,

18,

19]: (1) QLB’s broader ne rveblock effects on the sympathetic nervous system, potentially delayinggastrointestinal function recovery in the short term; and (2) QLB’s significant reduction in intraoperative opioid use, which helps avoid opioid-in duced gastrointestinal suppression, nausea, vomiting, a nd immune suppression, thus promoting overall recov ery.Some studies have indicated that excessive opioid usecan suppress fluid balance and cellular immunity, potentially promoting tumor metastasis and recurrence [

20,

21]. Therefore, despite the slight delay in gastrointe stinal recovery, the benefits of QLB in reducing opioi d use and enhancing postoperative recovery may be more significant inthe long term.

Moreover, despite the delayed first flatus time in the QLB group, it was associated with a significantly shor ter hospital stay compared to the TAPB group, sugge sting that QLB not only offers better pain reliefbut al so accelerates postoperative recovery [

22]. This reduction in opioid dependency, combined with better pain ma nagement, provides important insights for perioperativ emanagement in ERAS pathways [

23].

Several randomized controlled trials have compared t he effects of QLB and TAPB invarious surgeries, inclu ding gastrointestinal,cesarean, and hip surgeries [

24]. Bla nco et al. reported that QLB was superior to TAPB i n prolonging pain relief and reducing opioid use duri ngcesarean sections [

25]. Deng et al. and Huang et al. a lso demonstrated that QLB provided better pain control in laparoscopic colorectal surgery [

26,

27]. Our study co nfirms these conclusions and further extends the findings by using a multicenter design and PSM, enhancing the external validity and reliability of the results.

In particular, QLB in laparoscopic colorectal surgery provides effective pain control from the T7 to T12 dermatomes, which is essential for managing visceral pai n duringlaparoscopic procedures. Furthermore, QLBnot only provides somatic pain relief but also has the ad ded advantage of visceral pain control. Compared to anterior and posterior approaches, the lateral QLB approach has a lower incidence of lower limb muscle weakness and better avoids direct-injury to the abdominal cavity, abdominalorgans, and major blood vessels.

The results of this study indicate that QLB, as part o f multimodal analgesia, significantly reduces opioid us e, alleviates early postoperative pain, and shortens ho spital stays in laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery. This aligns with the core goals of the ERAS pathway. QLB is superior to TAPB-in terms of pain relief, opioid reduction, and recovery time, making it particularly suitable for high-risk patients, such as those intolerant to opioids or with cardiovascular risks.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the strengths of this study, including its two- center design and PSM, severallimitations remain. Firs t, the sample size was relatively small, which may le ad to type II errors for some secondary outcomes. Second, the study only compared lateralQLB with TAPB , and future research should explore the differences between variousQLB approaches (e.g., anterior, posterior, or intermuscular) and their effects on postoperati ve recovery. Third, the study did not assess long-term outcomes, such as the incidence of chronic pain o r cancer recurrence. With a relatively short follow-up period, future studies should focus on long-term follow-up to evaluate the impact of QLB on long-term prognosis and recurrence in cancer patients.

Conclusion

In this two-center, prospective, randomized controlled study, we compared the effectiveness of ultrasound-g uided quadratus lumborum block (QLB) with transvers us abdominis plane block (TAPB) in laparoscopiccolorectal cancer surgery. The results show that QLB signifi cantly reduces intraoperative opioid consumption, imp roves early postoperative pain relief, and shortens ho spital stays, despite a slight delay in gastrointestinal recovery. Both methods showed similar safety profiles in terms of hemodynamic stability and complication r ates, indicating that both are feasible and safe analge sic strategies. Overall, QLB offers more potential advantages in facilitating ERAS implementation compared to TAPB. This study’s multicenter design and propensity score matching methods strengthen the-reliability and external generalizability of the findings. Future res earch with larger sample sizes, multicenter designs, a nd long-term follow-up is needed to further validate the role of QLB in perioperative pain management an d recovery for cancer patients.

Authors’ contributions

Study conception and design: CFZ, ZW; Acquisition of data: XTM CFZ Analysis and interpretation of data: ZW, HY; Drafting of manuscript: CFZ, XMH. Critical revision: XMH ZW and revision of the manuscript after critical review: all uthors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Data is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This study was supported by Xuzhou Municipal Health Commission Scientific Research Project (XZWSJKKJ-2023-1522)

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the efforts of all medical staff and the patients for their participation in this study. Special thanks to Dr. Cong Liu for helping to polish our article.

References

- Kehl et, H.; Jensen, T.S.; Woolf, C.J. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006, 367, 1618–25. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, J.C.; Bao, X.; Agarwala, A. Pain management in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols. Cl in Colon Rectal Surg. 2019, 32, 121–8. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, R.L.; Wagle, N.S.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023, 73, 233–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017, 67, 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, R.; Shao, P.; Hu, J.; Li, H.; Wang, Y. Anterior Quadratus lumborum block at lateral Supra-Arcuate ligament vs lateral Quadratus lumborum block for postopera- tive analgesia after laparoscopic colorectal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2024, 238, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Akerman, M.; Pejčić, N.; Veličković, I. A review of the Quadratus lumborum block and ERAS. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018, 5, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Kupiec, A.; Zwierzchowski, J.; Kowal-Janicka, J.; et al. The analgesic efficiency of transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block after caesarean delivery. Ginekol Pol. 2018, 89, 421–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murouchi, T.; Iwasaki, S.; Yamakage, M. Quadratus lumborum block: analgesic effects and chronological ropivacaine concentrations after laparoscopic surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016, 41, 146–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S.H.; George, R.M.; Matos, J.R.; Wilson, D.A.; Johnson, W.J.; Woolf, S.K. Preopera- tive Quadratus lumborum block reduces opioid requirements in the immedi- ate postoperative period following hip arthroscopy: A randomized, blinded clinical trial. Arthroscopy. 2022, 38, 808–15. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, R.; Ansari, T.; Riad, W.; Shetty, N. Quadratus lumborum block versus trans-versus abdominis plane block for postoperative pain after Cesarean delivery: A randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016, 41, 757–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.; Qi, Y.; He, H.; Lou, J.; Pei, Q.; Mei, Y. Analgesic effect of the ultrasound-guided subcostal approach to transmuscular quadratus lumborum block in patients undergoing laparoscopic nephrectomy: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019, 19, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Li, S.; Weng, Q.; Long, J.; Wu, D. Opioid-free anesthesia with ultrasound-guided quadratus lumborum block in the supine position for lower abdomi- nal or pelvic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Song, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, X.; Li, C. Posteromedial quadratus lumborum block versus transversus abdominal plane block for postoperative analgesia following laparoscopic colorectal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J Cl in Anesth. 2020, 62, 109716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Long, X.; Li, M.; et al. Quadratus lumborum block versus transversus abdominis plane block for postoperative pain management after laparoscopic colorectal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Med (Baltim). 2019, 98, e18448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balocco, A.L.; López, A.M.; Kesteloot, C.; et al. Quadratus lumborum block: an imaging study of three approaches. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2021, 46, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, K.; Levins, K.J.; Buggy, D.J. Can anesthetic-analgesic technique during primary cancer surgery affect recurrence or metastasis. Can J Anaesth. 2016, 63, 184–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulianne, M.; Paquet, P.; Veil leux, R.; et al. Effects of quadratus lumborum block regional anesthesia on postoperative pain after colorectal resection: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2020, 34, 4157–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.; Luk, K.; Vang, D.; et al. Morphine stimulates cancer progression and mast cell activation and impairs survival in Transgenic mice with breast cancer. Br J Anaesth. 2014, 113, i4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Kong, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Erector spinae plane block versus quadratus lum- borum block for postoperative analgesia after laparoscopic nephrectomy: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Anesth. 2024, 96, 111466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, C.; Buggy, D.J. Opioids and tumour metastasis: does the choiceof the anesthetic-analgesic techniqueinfluence outcome after cancer surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2016, 29, 468–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, A.K.; Smith, C.M.; Rahmatullah, M.; et al. Opioid analgesia and opioid-induced adverse effects: a review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021, 14, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenk, E.S.; Lam, E.; Abulfathi, A.A.; et al. Population Pharmacokinetic and safety analysis of ropivacaine used for erector spinae plane blocks. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2023, 48, 454–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.K.; Lu, Z.K.; Deng, F.; et al. Comparison of three concentrations of ropi- vacaine in posterior quadratus lumborum block: A randomized clinical trial. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e28434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitman, M.; Fettiplace, M.R.; Weinberg, G.L.; Neal, J.M.; Barrington, M.J. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity: A narrative literature review and clinical update on prevention, diagnosis, and management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019, 144, 783–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbes, C.P.; Thompson, J.P. Pharmacokinetics of anaesthetic drugs at extremes of body weight. BJA Educ. 2018, 18, 364–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, C.C.; Wallisch, W.J.; Homanics, G.E.; Williams, J.P. Pathophysiological and neurochemical mechanisms of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014, 722, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, W.; Shahbaz, O.; Teskey, G.; et al. Mechanisms of nausea and vomiting: current knowledge and recent advances in intracellular emetic signaling systems. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).