1. Introduction

Multimodal analgesia has emerged as an effective strategy for postoperative pain management by combining multiple classes of systemic analgesic medications or various modalities [

1]. It has significantly advanced in recent years to reduce pain, minimize opioid consumption, prevent chronic pain, and improve quality of recovery [

2,

3,

4]. Additionally, regional anesthesia techniques, particularly interfascial plane blocks, play a crucial role in abdominopelvic surgeries as part of multimodal analgesia [

1,

5].

One such interfascial plane block is the quadratus lumborum block (QLB), which has recently gained attention as a promising innovation. Although QLB was initially introduced by Dr. Blanco, the anterior QLB approach has since become the most widely adopted technique.[

6,

7,

8] This approach involves injecting local anesthetics between the quadratus lumborum muscle and the psoas muscle, providing a wide range of sensory blockade and potentially managing visceral pain through sympathetic blockade, although its effectiveness depends on the extent of local anesthetic spread, which is often inconsistent in clinical practice [

9,

10].

In addition to multimodal analgesia, the importance of procedure-specific postoperative pain management has also been emphasized in recent years [

11]. As a result, numerous studies have been conducted to investigate and validate the efficacy of QLB across various surgical indications [

12]. For hysterectomy, procedure-specific pain management protocols have been established for both laparotomy and laparoscopic approaches [

13]. However, in laparoscopic surgery, the focus has primarily been on multiport laparoscopic hysterectomy [

13]. Recently, advances in minimally invasive surgery have led to the increasing adoption of single-port total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH), which differs significantly from the multiport approach in terms of surgical techniques, postoperative pain characteristics, complications, and recovery quality. Despite these differences, procedure-specific protocols tailored to single-port TLH remain underexplored, highlighting a critical gap in the current guidelines.

Given two key considerations—the growing importance of QLB as a crucial component of multimodal analgesia and the need for tailored pain management protocols for single-port TLH—this study aims to evaluate whether QLB can reduce opioid consumption within the first 24 hours postoperatively and improve postoperative pain management in patients undergoing single-port TLH.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This randomized, controlled, observer-blinded trial was conducted at Daejeon Saint Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, Republic of Korea. The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval (DIRB-00146_2-006) was obtained from the Catholic University of Korea Institutional Review Board, and the protocol was prospectively registered in the Clinical Trial Registry of Korea (KCT0002230). Written informed consent was secured from all participants prior to enrollment.

Eligible participants included patients aged 19 to 60 years with an American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) physical status classification of I to III, scheduled for elective total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH). Exclusion criteria included the presence of significant coagulopathy, infection at the injection site, allergy to local anesthetics, severe cardiopulmonary disease, body mass index (BMI) > 35 kg/m², neuropathies such as diabetic neuropathy, chronic opioid use, refusal of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), inability to understand the visual analog scale (VAS) or PCA usage, and patient preference to receive or avoid quadratus lumborum block (QLB).

2.2. Randomization

Participants were randomly assigned to either the QLB group (experimental) or the control group using a computer-generated random number table. Randomization information was sealed in opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes, which were opened immediately before the intervention by a team member not involved in block performance or outcome assessment.

2.3. Intraoperative Management

Upon arrival in the operating room, standard monitoring was initiated. General anesthesia was induced using propofol (1–2 mg/kg), rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg), and remifentanil. Anesthesia was maintained with desflurane (4–6 vol%) and remifentanil (0.01–0.05 mcg/kg/min), targeting a bispectral index (BIS) of 40–60. At the end of surgery, bilateral QLBs were performed in the experimental group. Neuromuscular blockade was reversed using pyridostigmine and glycopyrrolate, and extubation was conducted once the train-of-four ratio exceeded 95%. Patients were then transferred to the recovery room.

2.4. Surgical Technique

All surgeries were performed by one of two experienced gynecologic surgeons. A 1.5–2.0 cm vertical transumbilical incision was made, followed by rectus fasciotomy and peritoneal incision. A single-port system (Octoport™, Dalim, Seoul, Korea) was used, consisting of a retractor and a cap component with multiple channels for laparoscopic instruments and a scope. Carbon dioxide insufflation was applied to create pneumoperitoneum. A 5-mm rigid 0° or 10-mm 30° laparoscope was used as per surgeon preference. Specimens were extracted vaginally via manual morcellation, avoiding trocar-site pain. Vaginal cuff closure was performed laparoscopically using three extracorporeal figure-eight sutures with 0 Polysorb (Syneture, Mansfield, MA, USA).

2.5. Block Technique

QLBs were performed under aseptic conditions using real-time ultrasound guidance (WS80A, Samsung Medicine, Korea) by an expert with over five years of experience. In the lateral position, a 2–7 MHz curved ultrasound probe was placed along the midaxillary line to identify the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles, along with the transversus abdominis aponeurosis. The probe was moved posteriorly to visualize the quadratus lumborum, psoas major, and erector spinae muscles using the "shamrock sign." A 22-gauge, 90-mm Tuohy needle (Taechang Inc., Gongju, Korea) was inserted in a posterior-to-anterior direction. Needle placement was confirmed between the quadratus lumborum muscle and the psoas muscle using an injection of 0.5–1 mL of saline, followed by the administration of 0.375% ropivacaine with epinephrine (5 mcg/mL). The procedure was then repeated on the contralateral side.

2.6. Postoperative Management

Postoperative analgesia was managed according to our hospital’s Acute Pain Service protocol. Dexamethasone 5 mg was administered prior to the surgical incision, while intravenous fentanyl 1 mcg/kg, ketorolac 30 mg, paracetamol 1 g, and ramosetron 0.3 mg were given approximately 30 minutes before the conclusion of the surgery. In the recovery room, intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) was initiated using the Accumate1200 device (Woo Young Medical, Korea), delivering fentanyl in patient-demanded boluses of 0.5 mcg/kg with a 7-minute lockout interval and no basal infusion. Postoperative oral analgesics included zaltoprofen (80 mg) and celecoxib (2 00 mg) every 8 hours for three days. Rescue analgesia with tramadol (25 mg) was provided if VAS scores exceeded 4 despite PCA.

2.7. Outcomes

The primary outcome was cumulative fentanyl consumption within the first 24 hours postoperatively, recorded via PCA device logs. Tramadol usage for rescue analgesia was converted into fentanyl equivalents (25 mg tramadol = 25 mcg fentanyl) [

14,

15]. Secondary outcomes included VAS scores recorded at PACU, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 32, and 48 hours, time to first opioid demand, and the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). Complications such as vascular punctures during QLB were also documented.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Based on a pilot study where 24-hour fentanyl consumption was 246.3 ± 85.5 mcg, a clinical difference of 30% (73.89 mcg) was deemed significant. Considering a dropout rate of 10%, with an alpha level of 0.05 and power of 90%, we calculated a required sample size of 64 participants (32 per group).

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Normality of data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were compared using the unpaired t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate, and are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median [interquartile range (IQR)]. Categorical data were analyzed using Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

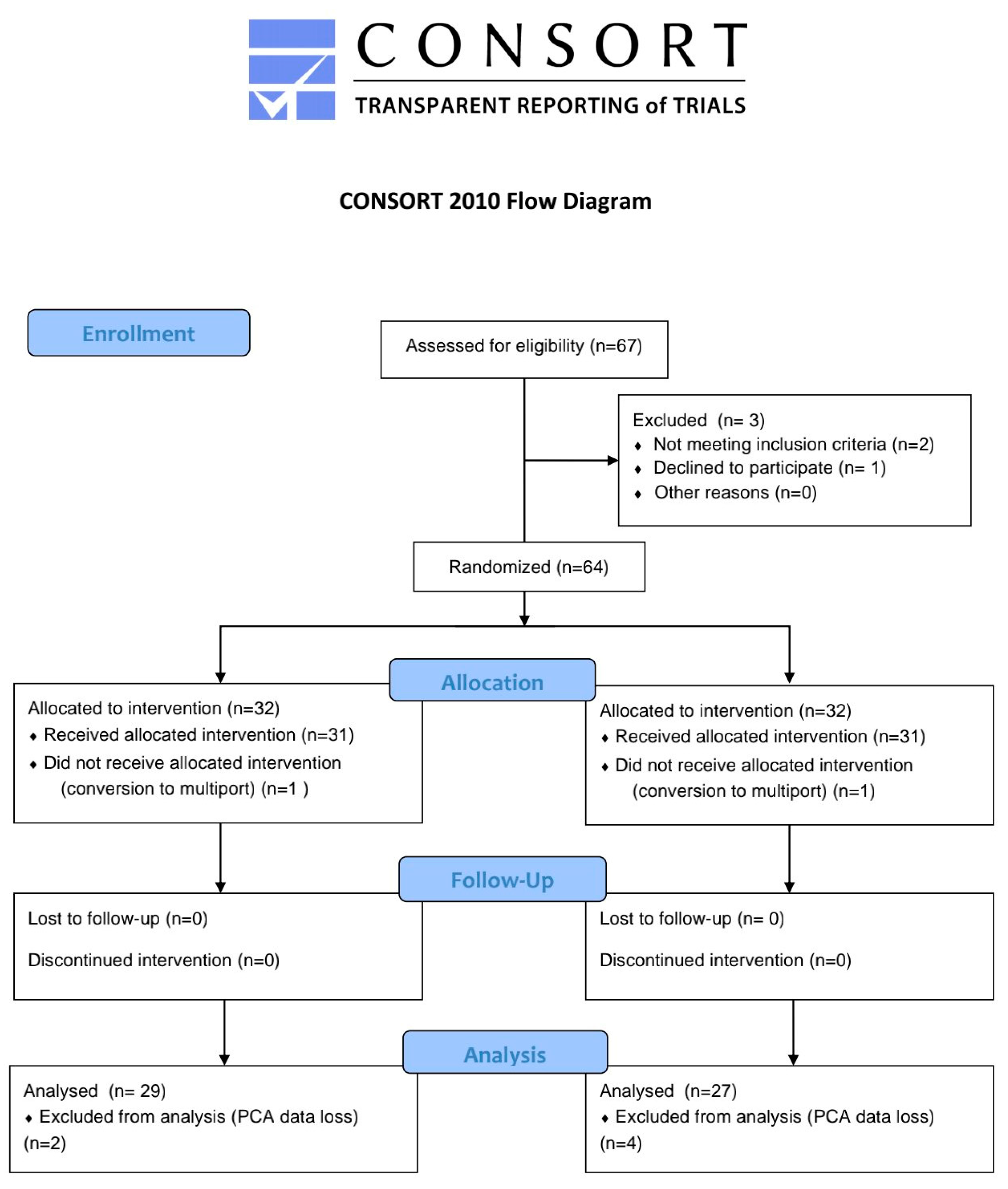

A total of 64 patients were enrolled in the study, with 32 patients in each group. However, 6 patients were excluded due to PCA data backup errors, and 2 patients were excluded after conversion to a three-port approach during surgery. Consequently, the final analysis included 27 patients in the QLB group and 29 patients in the control group (

Figure 1). Baseline demographic characteristics are presented in

Table 1. Except for height, there were no significant differences between the two groups.

Baseline demographic characteristics are presented in

Table 1. Except for height, there were no significant differences between the two groups.

The 24-hour cumulative fentanyl consumption was 470 [191.6, 648.1] mcg in the control group and 342.8 [220, 651] mcg in the QLB group, with no statistically significant difference between the groups (P = 0.714). Similarly, there were no significant differences in cumulative fentanyl consumption at 2h, 4h, 8h, 12h, 24h, 32h, and 48h including the PACU (

Table 2).

The time to first bolus on demand was comparable between the control group and the QLB group (16 [10–26.5] vs. 14 [10–26], P = 0.204). Postoperative VAS scores also showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups (

Table 3).

However, there was a significant difference in the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) between the groups. Despite no differences in PONV risk factors, PONV occurred in 7 patients (25.9%) in the QLB group compared to only 1 patient (3.4%) in the control group (P = 0.023).

There were no complications related to the QLB procedure itself. However, one patient in the QLB group experienced mild motor weakness, which was resolved without further issues. No other adverse events were reported.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of the quadratus lumborum block (QLB) in single-port total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH). The primary outcome, cumulative opioid consumption during the first 24 hours postoperatively, showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups. Additionally, there were no differences in opioid consumption, pain scores, or time to first bolus administration assessed from the recovery room up to 48 hours postoperatively.

Among the various approaches to QLB, anterior QLB typically provides a block of the ventral rami of the T8/9-L1/3 intercostal nerves. It also has the potential to control visceral pain due to the spread of local anesthetic into the thoracic paravertebral space though the lateral arcuate ligament [

10,

16,

17]. Despite this theoretical advantage, our study did not find a significant difference in analgesic outcomes between the QLB and control groups for single-port TLH.

Several studies support findings similar to ours. Hansen et al. [

18] investigated the analgesic efficacy of trocar site infiltration versus transmuscular QLB (TQLB) in 70 patients undergoing TLH with a four-port technique. They found no significant difference in the primary outcome, 12-hour opioid consumption (morphine-equivalent dose, 58.4 vs. 62.9 mg), or in other time intervals, pain scores, or time to first opioid administration. Similarly, She et al. [

19] compared QLB to placebo in 92 patients undergoing three-port TLH and reported no significant difference in cumulative sufentanil consumption (QLB: 0.08 [0.00 to 0.21] vs. placebo: 0.12 [0.03 to 0.23], P = 0.268).

One plausible explanation for these findings is the possibility that the spread of local anesthetic into the thoracic paravertebral space was insufficient or inconsistent during anterior QLB, which may have limited its ability to control visceral pain effectively. The spread of local anesthetic into the thoracic paravertebral space following QLB remains controversial. Flynn et al. [

20] performed thoracic paravertebral blocks in 10 specimens using 30 mL of methylene blue dye, demonstrating successful TPVS spread in 9 cases. However, they reported no dye spread into the space anterior to the quadratus lumborum muscle or around the psoas muscle. Similarly, Gadson et al. [

21] used contrast imaging in fresh cadavers, performing TPVB on one side and TQLB on the other, and found no spread from the TQL space to the TPVS. These findings question the proposed mechanism of QLB for reducing visceral pain, which assumes that the QL space and TPVS are connected via the lateral arcuate ligament of the diaphragm.

Another consideration is that pain after TLH may be predominantly visceral rather than somatic, contrary to initial assumptions. Choi et al. [

22] reported that visceral pain consistently exceeded somatic pain during the first 72 hours postoperatively. Visceral pain after TLH mainly originates from pelvic organs like the uterus and vagina, with contributions from both sympathetic (T12-L2 lumbar splanchnic nerves) and parasympathetic (S2-4 pelvic splanchnic nerves) fibers.[

23,

24] These fibers form uterovaginal and hypogastric plexuses. The sacral component of visceral pain resulting from vaginal incisions lies outside the coverage of QLB, potentially limiting its effectiveness.

While our findings align with these limitations, other studies have shown an opioid-sparing effect of QLB in TLH. For example, one study found that TQLB reduced 24-hour cumulative morphine consumption compared to subcostal TAP blocks [

25]. Another study by Jadon et al. [

26] reported reduced 24-hour fentanyl consumption (167 vs. 226 mcg, P < 0.0001) in the TQLB group compared to a sham block group. These results, however, may reflect the limited effectiveness of subcostal TAP blocks in addressing somatic pain from lower abdominal port incisions, while TQLB could partially address this somatic pain [

5,

27]. In contrast, our study focused on single-port TLH, where somatic pain is already minimized compared to multiport techniques. With minimal somatic pain and predominantly visceral pain, the impact of QLB on overall pain and opioid consumption appears negligible.

Our study has some limitations. We did not distinguish between somatic and visceral pain when assessing postoperative pain. Moreover, visceral pain characteristics, such as CO2-induced referred pain to the scapular area versus pelvic organ-related pain, were not separately evaluated. A more detailed pain assessment would have allowed better interpretation of our findings.

Despite its limitations, our study offers significant strengths. While procedure-specific protocols for multiport TLH are well-established, evidence for single-port TLH remains scarce. As single-port TLH becomes increasingly prevalent, our study represents one of the few prospective randomized trials addressing QLB in this context, providing valuable evidence for PROSPECT guidelines.

5. Conclusions

Bilateral TQLB did not reduce opioid consumption or pain scores in patients undergoing single-port TLH. These results suggest that TQLB offers no significant benefit as part of multimodal analgesia after single port TLH.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and S.L.; methodology, J.C. H.S., and Y.L.; formal analysis, S.B. H.S., and Y.L.; investigation, J.C. , Y.P., S.B., and Y.L.; data curation, J.C., Y.P., H.S., and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C., H.S., and S.B.; writing—review and editing, S.B., S.L., Y.L., H.S, Y.P., and J.C.; visualization, Y.P.; supervision, S.L., S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 52017A015400300).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Korea (DIRB-00146_2-006)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study areavailable from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) (No. 52017A015400300).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- O'Neill A, Lirk P. Multimodal Analgesia. Anesthesiol Clin. Sep 2022;40(3):455-468. [CrossRef]

- Jin F, Chung F. Multimodal analgesia for postoperative pain control. J Clin Anesth. Nov 2001;13(7):524-39. [CrossRef]

- Beverly A, Kaye AD, Ljungqvist O, Urman RD. Essential Elements of Multimodal Analgesia in Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Guidelines. Anesthesiol Clin. Jun 2017;35(2):e115-e143. [CrossRef]

- Chen YK, Boden KA, Schreiber KL. The role of regional anaesthesia and multimodal analgesia in the prevention of chronic postoperative pain: a narrative review. Anaesthesia. Jan 2021;76 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):8-17. [CrossRef]

- Chin KJ, McDonnell JG, Carvalho B, Sharkey A, Pawa A, Gadsden J. Essentials of Our Current Understanding: Abdominal Wall Blocks. Reg Anesth Pain Med. Mar/Apr 2017;42(2):133-183. [CrossRef]

- Blanco R. 271. Tap block under ultrasound guidance: the description of a “no pops” technique. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine. 2007;32(Suppl 1):130-130. [CrossRef]

- Blanco R, McDonnell J. Optimal point of injection: the quadratus lumborum type I and II blocks. Anesthesia. 2013;68:4.

- Børglum J, Moriggl B, Jensen K, et al. Ultrasound-guided transmuscular quadratus lumborum blockade. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2013;111(eLetters).

- Carline L, McLeod GA, Lamb C. A cadaver study comparing spread of dye and nerve involvement after three different quadratus lumborum blocks. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2016;117(3):387-394. [CrossRef]

- Elsharkawy H, El-Boghdadly K, Barrington M. Quadratus Lumborum Block: Anatomical Concepts, Mechanisms, and Techniques. Anesthesiology. Feb 2019;130(2):322-335. [CrossRef]

- Freys JC, Bigalke SM, Mertes M, Lobo DN, Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Freys SM. Perioperative pain management for appendicectomy: A systematic review and Procedure-specific Postoperative Pain Management recommendations. Eur J Anaesthesiol. Mar 1 2024;41(3):174-187. [CrossRef]

- Jin Z, Liu J, Li R, Gan TJ, He Y, Lin J. Single injection Quadratus Lumborum block for postoperative analgesia in adult surgical population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. Jun 2020;62:109715. [CrossRef]

- Lirk P, Thiry J, Bonnet MP, Joshi GP, Bonnet F. Pain management after laparoscopic hysterectomy: systematic review of literature and PROSPECT recommendations. Reg Anesth Pain Med. Apr 2019;44(4):425-436. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann KA. [Tramadol in acute pain]. Drugs. 1997;53 Suppl 2:25-33. Le tramadol dans les douleurs aiguës. [CrossRef]

- Pereira J, Lawlor P, Vigano A, Dorgan M, Bruera E. Equianalgesic dose ratios for opioids. a critical review and proposals for long-term dosing. J Pain Symptom Manage. Aug 2001;22(2):672-87. [CrossRef]

- She H, Jiang P, Zhu J, et al. Comparison of the analgesic effect of quadratus lumborum block and epidural block in open uterine surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Minerva Anestesiol. Apr 2021;87(4):414-422. [CrossRef]

- Bak H, Bang S, Yoo S, Kim S, Lee SY. Continuous quadratus lumborum block as part of multimodal analgesia after total hip arthroplasty: a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. Apr 2020;73(2):158-162. [CrossRef]

- Hansen C, Dam M, Nielsen MV, et al. Transmuscular quadratus lumborum block for total laparoscopic hysterectomy: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. Jan 2021;46(1):25-30. [CrossRef]

- She H, Qin Y, Peng W, et al. Anterior Quadratus Lumborum Block for Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin J Pain. Nov 1 2023;39(11):571-579. [CrossRef]

- Flynn DN, Rojas AF, Low AL, et al. The road not taken: An investigation of injectate spread between the thoracic paravertebral space and the quadratus lumborum. J Clin Anesth. Aug 2022;79:110697. [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Sadeghi N, Wahal C, Gadsden J, Grant SA. Quadratus Lumborum Spares Paravertebral Space in Fresh Cadaver Injection. Anesth Analg. Aug 2017;125(2):708-709. [CrossRef]

- Choi BJ, Choi SG, Ryeon O, Kwon W. A study of the analgesic efficacy of rectus sheath block in single-port total laparoscopic hysterectomy: a randomized controlled study. J Int Med Res. Oct 2022;50(10):3000605221133061. [CrossRef]

- Astruc A, Roux L, Robin F, et al. Advanced Insights into Human Uterine Innervation: Implications for Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain. J Clin Med. Mar 1 2024;13(5)doi:10.3390/jcm13051433.

- Aurore V, Röthlisberger R, Boemke N, et al. Anatomy of the female pelvic nerves: a macroscopic study of the hypogastric plexus and their relations and variations. J Anat. Sep 2020;237(3):487-494. [CrossRef]

- Huang L, Zheng L, Zhang J, et al. Transmuscular quadratus lumborum block versus oblique subcostal transversus abdominis plane block for analgesia in laparoscopic hysterectomy: a randomised single-blind trial. BMJ Open. Aug 10 2021;11(8):e043883. [CrossRef]

- Jadon A, Ahmad A, Sahoo RK, Sinha N, Chakraborty S, Bakshi A. Efficacy of transmuscular quadratus lumborum block in the multimodal regimen for postoperative analgesia after total laparoscopic hysterectomy: A prospective randomised double-blinded study. Indian J Anaesth. May 2021;65(5):362-368. [CrossRef]

- Hebbard P. Subcostal Transversus Abdominis Plane Block Under Ultrasound Guidance. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2008;106(2):674-675. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).