1. Introduction

In major abdominal surgery, multimodal analgesia is recommended to provide effective postoperative analgesia, which is one of the most important components of early accelerated recovery protocols [

1,

2]. For this purpose, neuraxial blocks, peripheral nerve blocks, local wound infiltration and intravenous (IV) analgesia can be used as multimodal analgesic methods. Multimodal analgesia may improve patient outcomes by reducing postoperative opioid use and associated adverse effects such as postoperative nausea, vomiting and ileus [

3]. Epidural analgesia remains as the gold standard and the most commonly used analgesic technique for postoperative analgesia in such surgeries [

2,

4]. However, in epidural analgesia, the use of local anesthetics may cause motor blockade and hypotension, whereas complications such as nausea, vomiting, respiratory depression and urinary retention may occur due to intravenous opioids, hence the choice of the most effective analgesia in these surgical procedures is still controversial and methods to reduce the use of intravenous opioids are being sought. Intrathecal opioids, one of the central neuraxial methods, may offer analgesia that is easier to administer, less costly and has lower failure rates than epidural analgesia [

5] Intrathecal opioid administration alone without local anesthetics prevents complications related to motor blockade, and reduces intravenous opioid consumption by creating a long duration of action with its low volume of distribution and slow diffusion effect [

6,

7]. Transversus abdominis plane blocks (TAPB) have gained popularity in recent years owing to the widespread use of ultrasonography, and have been shown to provide effective postoperative analgesia in abdominal surgery [

8,

9]. With such peripheral block applications, the risks of complications that may develop due to neuraxial blocks are also prevented. The most commonly used posterior TAPB provides effective analgesia mainly for subumbilical incisions (T10-L1 dermatomes), while subcostal TAPB is more effective for incisions above the umbilicus (T6-T10 dermatomes)[

10,

11]. Therefore, dual bilateral TAPB, i.e., four-quadrant TAPB, should be used in surgery involving the anterior abdominal wall.

Thus, we primarily planned to compare the effectiveness of postoperative analgesia in patients with epidural catheter failure in gynecologic cancer surgery or in patients who did not want epidural catheter placement in our clinic, on whom we performed intrathecal morphine or four-quadrant TAPB as a part of our routine analgesic protocol together with intravenous analgesia. Secondarily, we evaluated opioid demand and bolus dose, length of hospital stay, opioid-related side effects and complications during postoperative 24 hours.

2. Methods

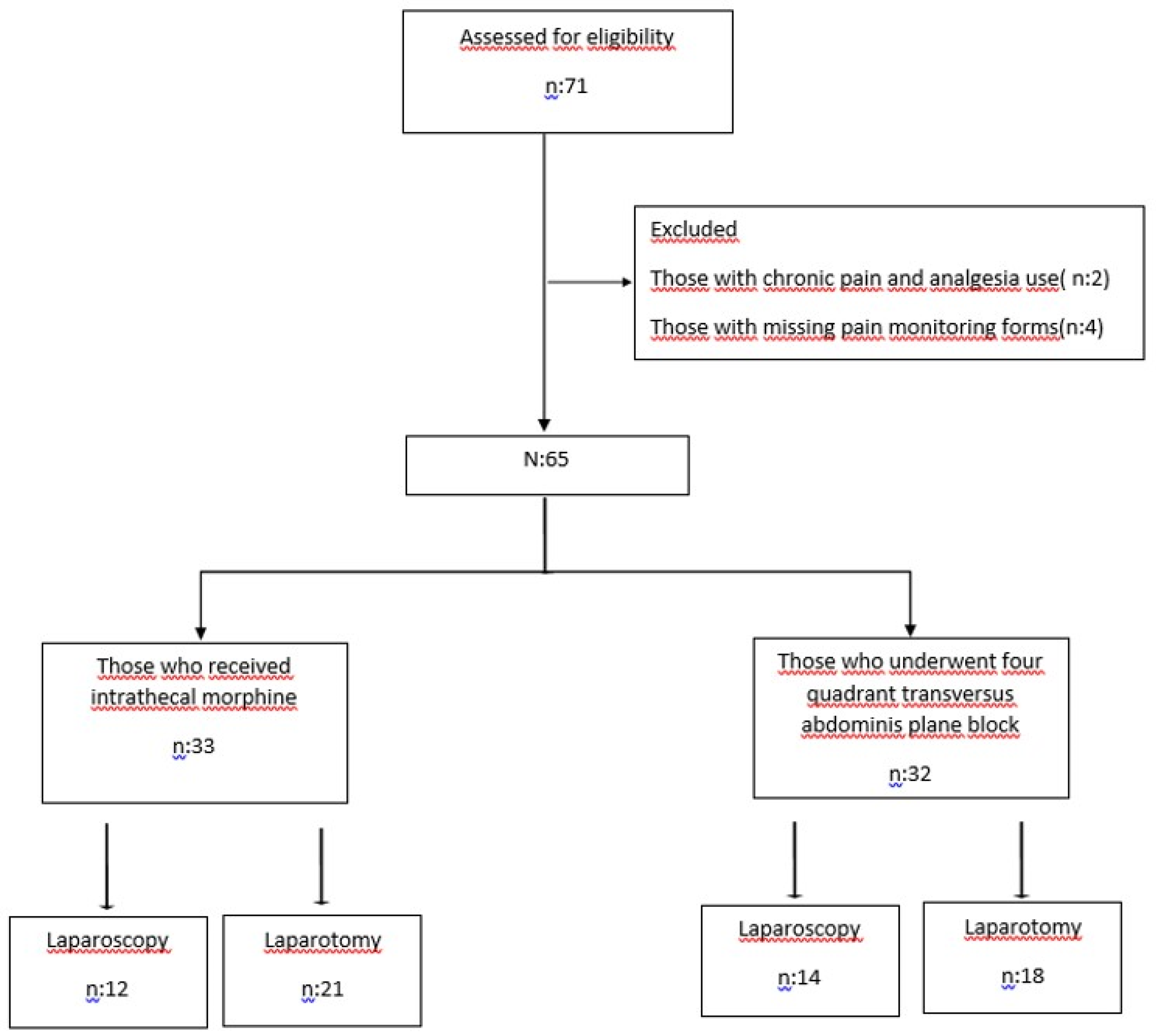

After ethics committee approval (decision no: 60, date: January 31, 2024), two analgesic methods in patients undergoing open or laparoscopic major gynecologic cancer surgery were retrospectively compared based on the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was recorded in the clinical trials register (NCT06382376). In this method, electronic patient record system and pain follow-up forms were used. The study included 71 patients over the age of 18, in ASA II and III, who underwent surgery for gynecologic cancer between June 1, 2023 and December 1, 2023, and to whom we applied intrathecal morphine (ITM) or four-quadrant transversus abdominis plane blocks (four-quadrant TAPB) through peripheral nerve blocks for postoperative analgesia. Patients who used analgesic drugs for chronic pain (2 patients) and those with missing pain follow-up forms (4 patients) were excluded (

Figure 1).

2.1. Anesthesia Management

Hemodynamic monitoring is provided to all patients in accordance with routine ASA standards. After routine induction of anesthesia in our clinic, patients are orotracheally intubated. Mechanical ventilation tidal volume is adjusted to ideal weight 6-8 ml, frequency 12/min, and end tidal carbondioxide pressure (etCO2) 35-45 mmHg. Depth of anesthesia is monitored by patient state index (PSI) (Masimo Corp., Irvine, CA, USA) to 25-50 and anesthesia maintenance is provided by intravenous (iv) remifentanil infusion and inhaled sevoflurane anesthesia. In fluid management, targeted fluid therapy is performed by advanced non-invasive hemodynamic monitoring (Masimo SET, Masimo Corp., Irvine, CA, USA).

Antiemetic management involves 8 mg iv dexamethasone after induction of anesthesia and 8 mg iv ondansetron at the end of the operation. Analgesic management involves intraoperative remifentanil infusion in addition to routine central or peripheral blocks and 1 g paracetamol, 100 mg tramadol and 400 mg ibuprofen at the end of surgery. Postoperatively, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is provided with IV morphine in addition to IV 75 mg diclofenac sodium every 12 hours and IV 1 g paracetamol every 8 hours. PCA dose is prepared to comprise 0.25 mg/ml morphine in 100 ml volume, 2 ml bolus, 20 min lockout time and maximum dose of 2 mg in 4 hours.

Patients who are hemodynamically stable are extubated and taken to the postoperative recovery unit. Patients without intensive care indication and with a modified Aldrete score of >9 are discharged to the ward. Patients are routinely visited in the ward or intensive care unit at regular intervals in accordance with our follow-up forms.

2.2. Our Perioperative Analgesic Method

2.2.1. Intrathecal Morphine Administration

Patients are informed about the procedure and its side effects as a result of which intrathecal morphine is administered to those who give their consent. Intrathecal morphine is administered before induction of anesthesia after standard hemodynamic monitoring. Patients are administered 3 mcg/kg intrathecal morphine for laparoscopic surgery and 5 mcg/kg intrathecal morphine for open surgery at the L3-4 level by providing sepsis-antisepsis conditions in the sitting position.

2.2.2. Four-Quadrant Transversus Abdominis Plane Block Application

Four-quadrant transversus abdominis plane blocks (four-quadrant TAPB) are applied before surgical incision in patients who are not suitable for epidural analgesia or intrathecal opioid analgesia following general anesthesia. Bilateral posterior TAPB and bilateral subcostal TAPB are performed by using in-plane technique with high frequency ultrasound probe (5–10 MHz, Sonosite, Inc., Bothell, WA, USA) under ultrasound guidance. For posterior TAPB, 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine is administered for one side. For subcostal TAPB, 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine is administered for one side in open cases and 10 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine in laparoscopic cases.

Demographic data of patients (age, body mass index (BMI)), ASA score, malignancy origin (ovary/endometrium/cervix), type of surgery (open or laparoscopic), operation time, 1-hour and 24-hour pain scores from postoperative pain follow-up forms, demand and bolus levels in 24 hours by using patient-controlled analgesia device, postoperative adverse effects (nausea, vomiting, pruritus, urinary retention, ileus, respiratory depression) and length of hospital stay were recorded. Nausea and vomiting were defined according to the postoperative antiemetic need, and pruritus was defined according to the use of 45.5 mg pheniramine hydrogen maleate. Presence of ileus, urinary retention and respiratory depression (need for medical intervention by medication or mechanical ventilation) was determined by free text evaluation of discharge summary.

Our primary clinical outcome was to evaluate the effect of the two analgesic methods on postoperative pain scores. Secondary clinical outcomes were to evaluate length of hospital stay, opioid demand and use, and complications.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using NCSS 11 (Number Cruncher Statistical System, 2017 Statistical Software). In this study, frequency and percentage values were given for the variables. Mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum values were given for continuous variables. The regular distribution test of continuous variables was performed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Chi-square analysis was used for the relationships between categorical variables. When appropriate, categorical variables were assessed with Fisher’s Exact test and Fisher-Freeman- Halton test. An independent sample t-test was used to compare two groups in continuous independent variables with normal distribution. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare two independent groups for the variables that did not meet the assumption of normal distribution. For independent variables that did not have a normal distribution, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the two groups. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 71 patients undergoing gynecologic oncological surgery were evaluated. Data of 65 patients who underwent ITM or four-quadrant TAPB were analyzed. 35 (53.8%), 28 (43.1%) and 2 (3.1%) patients were operated on for endometrial, ovarian and cervical cancer, respectively, 60% of whom were given laparotomy and 40% laparoscopy. The mean age of the patients was 52.9±11.8 years, BMI 29.4±5.5 kg/m2 and operation time 258.1±88.3 min.

When divided into two groups according to postoperative analgesia preferences, the ITM group included 33 patients and the four-quadrant TAPB group included 32 patients. Laparoscopic surgery was performed in 12 (36.4%) patients in the ITM group and 14 (43.8%) patients in the four-quadrant TAPB group. Demographic data (age, BMI), ASA clinical classifications, surgical diagnoses and procedures, length of hospital stay and intensive care hospitalization requirements were similar in both groups (

Table 1).

When all patients were divided according to laparoscopic and laparotomic surgical procedures, an analysis of the open cases revealed the mean age of the four-quadrant TAPB group to be higher than the ITM group (p<0.05). When the ITM and four-quadrant TAPB groups were analyzed separately in open and closed cases, BMI, operation times, surgical diagnoses, length of hospital stay and intensive care hospitalization rates were similar (

Table 2).

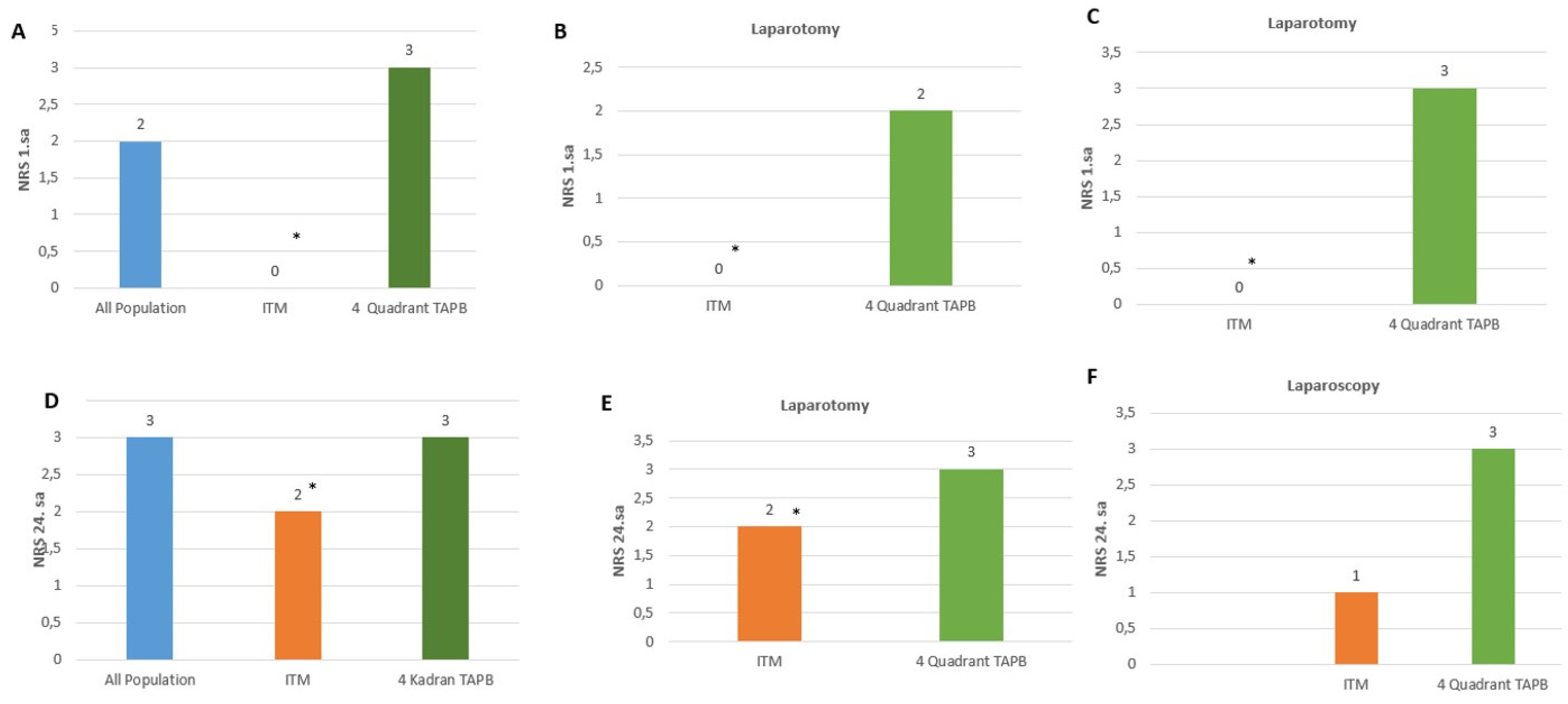

Figure 2 shows the 1- and 24-hour NRS values of the patients. The 1-h NRS values were lower in the ITM group compared to the four-quadrant TAPB group (p<0.05) (

Figure 2A). Upon an evaluation of the open and closed cases separately, it was observed that the NRS values were lower at a statistically significant rate in the ITM group compared to the four-quadrant TAPB group (

Figure 2B,2C).

The evaluation of 24-hour pain revealed that the NRS values were higher in the four-quadrant TAPB group compared to the ITM group (

Figure 2D). Upon an evaluation of the open and closed cases separately, the NRS values were found to be statistically significantly lower in the ITM group than in the four-quadrant TAPB group (

Figure 2E, 2F).

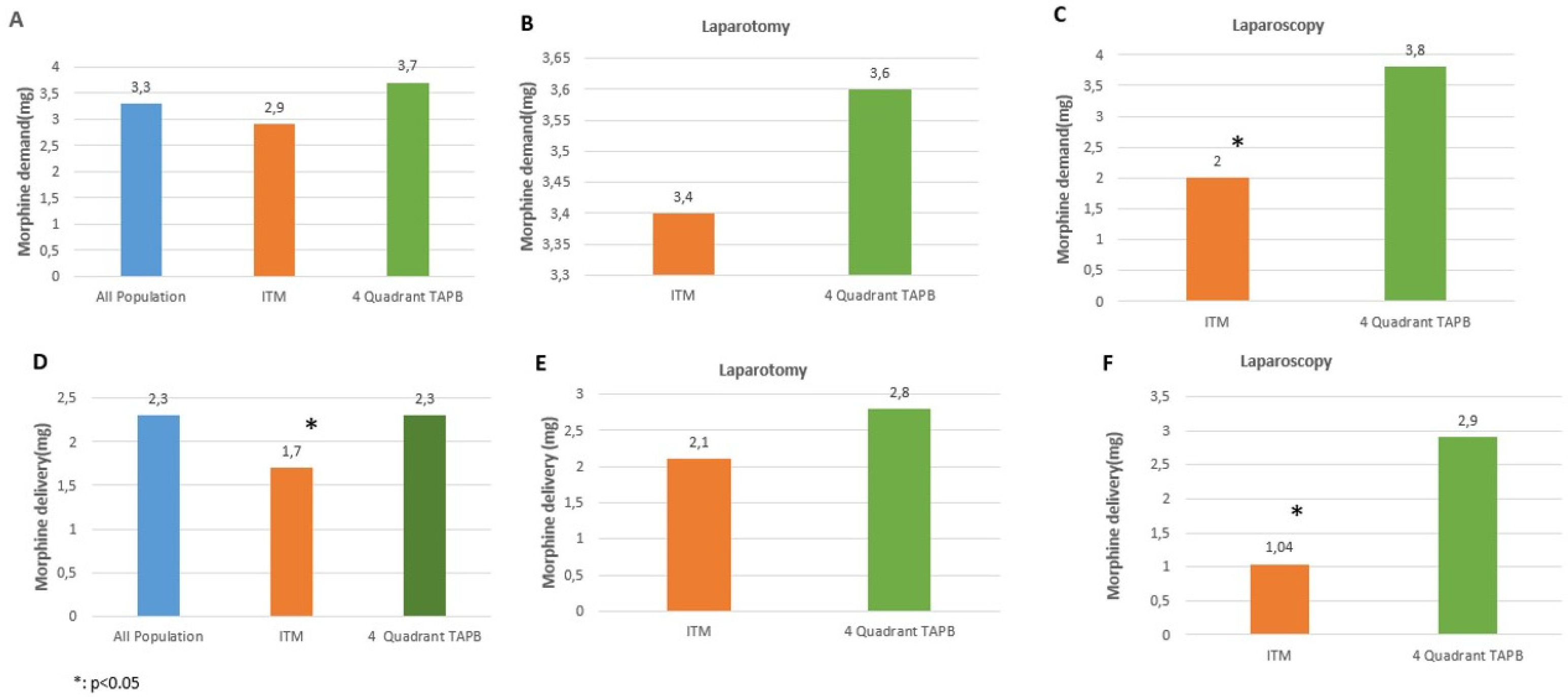

Figure 3 shows morphine demand and consumption levels of the patients through the PCA device in postoperative 24 hours. In terms of morphine demand, the respective levels were similar in the ITM and four-quadrant TAPB groups (

Figure 3A). In laparotomic cases, there was no statistically significant difference between the ITM and four-quadrant TAPB groups in terms of the morphine amounts demanded (

Figure 3B). In laparoscopic cases, the amount of morphine demanded was higher in the four-quadrant TAPB group (p<0.05) (

Figure 3C).

As for morphine consumption, the rates were lower in the ITM group compared to the four-quadrant TAPB group (p<0.05) (

Figure 3D). In laparotomic cases, there was no difference in blocks (

Figure 3E), whereas in laparoscopic cases, there was a statistically significant higher morphine consumption in the four-quadrant TAPB group (

Figure 3F).

Table 3 shows postoperative adverse effects and other complications. Nausea was observed in 52.3%, vomiting in 41.5%, pruritus in 10.8%, urinary retention in 4.6% and ileus in 1.5% of all patients. The ITM and four-quadrant TAPB groups were compared in terms of nausea, vomiting, pruritus, urinary retention, respiratory depression and ileus, which were among the adverse effects related to postoperative opioid use, and no difference was observed between the two groups. Apart from the aforementioned adverse effects, AKI was observed in 2 patients, anastomotic leakage in 1 patient and wound infection in 1 patient (p>0.05)(

Table 3).

When laparoscopic and laparotomic surgery were evaluated separately, it was observed that the adverse effects and other complications were similar in the ITM group and the four-quadrant TAPB group (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to retrospectively evaluate different regional analgesic techniques used for analgesia in patients operated for gynecologic cancer surgery. The results of the study showed that ITM administered for postoperative analgesia performed better than TAPB at 24 hours postoperatively and the rate of opioids used was lower with no difference in terms of adverse effects or complications.

Failure to achieve effective postoperative analgesia affects the comfort of patients and delays mobilization due to excessive intravenous opioid use and its adverse effects. This, in turn, increases the risk of morbidity and mortality. Since gynecologic cancer operation is major surgery, postoperative pain management has an important place in the respective ERAS protocols. The aim in providing optimum analgesia through ERAS protocols is to attain the most effective analgesia with the least adverse effects and the least complications. According to this protocol, epidural analgesia is still recommended for traditional pain control in major abdominal surgery, yet its use has decreased due to its side effects [

2]. However, the ideal analgesic technique in gynecologic cancer surgery remains uncertain. In this study, analgesia provided by single-dose intrathecal morphine administration and peripheral nerve blocks avoided the effects of central blocks such as motor blockade and catheter failure [

12,

13].

While transversus abdominis plane blocks are beneficial only for somatic pain, intrathecal morphine also blocks visceral pain by affecting both mu and kappa receptors [

14]. In addition, ITM administration delivers more effective analgesia compared to TAPB since it provides extensive dermatomal spread owing to homogeneous distribution of morphine in the cerebrospinal fluid, hence reduces opioid consumption [

15]. In a meta-analysis, intrathecal opioid has been shown to reduce intraoperative and postoperative opioid levels and postoperative pain scores [

16,

17]. It has been argued that the benefit of transversus abdominis plane blocks in multimodal analgesia in abdominal surgery is limited [

18,

19,

20]. In fact, it has been reported that transversus abdominis plane blocks in gynecologic cancer surgery compared to placebo group had no benefit in terms of postoperative pain and opioid use [

21]. In abdominal surgery, it has been reported that the four-quadrant trunk block through which subcostal and posterior TAPB are performed together is inadequate in analgesia because sufficient dermatomal spread cannot be achieved [

22]. However, there is also a group advocating transversus abdominis plane blocks as a multimodal analgesic method [

23,

24]. In fact, TAPB, one of the peripheral nerve blocks, has become more common with the use of ultrasonography in gynecologic cancer surgery in lieu of epidural analgesia through central blocks due to undesirable effects such as motor blockade, catheter failure and hypotension [

2]. Similar to our study, Michael et al. showed that intrathecal morphine reduced postoperative pain scores and opioid use in major abdominal surgery compared to peripheral nerve blocks [

25].

In the absence of effective pain management, acute pain becomes chronic and increases long-term opioid use. Therefore, although it is one of the cornerstones of perioperative analgesia management, ways to minimize opioid use are sought because of its high side effects [

26]. Particularly, severe side effects such as respiratory depression limit the use of intrathecal morphine [

27]. The effective dose range of intrathecal morphine in providing effective analgesia without causing respiratory depression is uncertain, and there is a possibility of respiratory depression at low doses. Therefore, there is no consensus about the optimal dose. In a study, 0.3 and 0.4 mg intrathecal morphine was shown to have a low risk of respiratory depression [

27]. In another meta-analysis, it was shown that 0.2 mg and 0.5 mg intrathecal morphine did not cause postoperative respiratory depression [

28]. Although concerns about delayed respiratory depression limit the widespread use of intrathecal morphine, it provides good postoperative analgesia [

29]. A meta-analysis by Fares et al. showed that the use of intrathecal morphine for postoperative analgesia in major abdominal surgery reduces both pain at rest and movement-evoked pain with low complication rates [

16]. In our study, it was observed that ITM was mostly preferred in the young patient group due to its side effect of respiratory depression, that low doses of intrathecal morphine were used and that no patient required mechanical ventilation.

The fact that only 24-hour postoperative pain of the patients was evaluated and the study was retrospective constitutes the limitation of this study, and it is considered that prospective studies with a larger sample group should be performed.

5. Conclusions

In cases where epidural analgesia is contraindicated, single-dose intrathecal morphine, which is easier to administer than four-quadrant TAPB, may be an alternative method for providing effective analgesia in abdominal surgery. Since there is no consensus on the optimum dose range for effective analgesia in intrathecal administration of morphine, we think that the intrathecal morphine doses in our study will be guiding for future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A., F.G.Ö.; Methodology, D.A., F.G.Ö.; Software, D.A.; Validation, D.A, Ş.Ö.; Formal Analysis, D.A., Ş.Ö.; Investigation, D.A, Ş.Ö.; Resources, D.A.; Data Curation, D.A, Ş.Ö.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, D.A, Ş.Ö. F.G.Ö; Writing—Review & Editing, D.A, Ş.Ö. F.G.Ö. ; Visualization D.A.; Supervision, D.A, Ş.Ö. F.G.Ö; Project Administration, D.A; Funding Acquisition, D.A.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Basaksehir Çam and Sakura City Hospital, decision no: 60, date: January 31, 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Since the study was retrospective, informed consent was not obtained.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hughes MJ, Ventham NT, McNally S, Harrison E, Wigmore S (2014) Analgesia after open abdominal surgery in the setting of enhanced recovery surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 149(12):1224–30. [CrossRef]

- G. Nelson, C. Fotopoulou, J. Taylor, G. Glaser, J. Bakkum-Gamez, L.A.Meyer, et al. (2023) Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) society guidelines for gynecologic oncology: addressing implementation challenges—2023 update. Gynecol. Oncol. 173:58–67. [CrossRef]

- Frauenknecht J, Kirkham KR, Jacot-Guillarmod A, Albrecht E (2019) Analgesic impact of intra-operative opioids vs. opioid-free anaesthesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia 74:651–662. [CrossRef]

- Wu CL, Cohen SR, Richman JM, Rowlingson AJ, Courpas GE, Cheung K et al. (2005) Efficacy of postoperative patient-controlled and continuous infusion epidural analgesia versus intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with opioids: a meta-analysis. Anesthesiology. 103:1079–88. [CrossRef]

- Mugabure Bujedo B( 2012) A clinical approach to neuraxial morphine forthe treatment of postoperative pain. Pain Res Treat.2012:612145. d OI: 10.1155/2012/612145.

- Ummenhofer WC, Arends RH, Shen DD, Bernards CM (2000) Comparative spinal distribution and clearance kinetics of intrathecally administered morphine, fentanyl, alfentanil, and sufentanil. Anesthesiology. 92 :739-53. [CrossRef]

- Levy BF, Scott MJ, Fawcett W., Fry C (2011) Randomized clinical trial of epidural, spinal or patient-controlled analgesia for patients undergoing laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 98(8) :1068–78. d OI: 10.1002/bjs.7545.

- Champaneria R, Shah L, Geoghegan J, Gupta JK, Daniels JP (2013) Analgesic effectiveness of transversus abdominis plane blocks after hysterectomy: a meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 166: 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Jouve P, Bazin JE, Petit A, Minville V, Gerard A, Buc E, et al. (2013) Epidural versus continuous preperitoneal analgesia during fast-track open colorectal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology 118(3):622-30. [CrossRef]

- Hebbard P 82008) Subcostal transversus abdominis plane block under ultrasound guidance. Anesthesia and Analgesia 106(2):674–5. [CrossRef]

- Borglum J, Jensen K, Christensen A, Hoegberg L, Johansen S, Lönnqvist PA, et al. (2012) Distribution patterns, dermatomal anesthesia, and ropivacaine serum concentrations after bilateral dual transversus abdominis plane block. RAPM. 37(3):294-301. [CrossRef]

- Groen JV, Khawar AAJ, Bauer PA, et al. (2019) Meta-analysis of epidural analgesia in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy. Open BJS. 3(5):559-71. [CrossRef]

- Pirie K, Myles PS, Riedel B (2020) A survey of neuraxial analgesic preferences in open and laparoscopic major abdominal surgery among anesthesiologists in Australia and New Zealand. Anesthesia Intensive Care. 48(4):314-7. [CrossRef]

- Carney J, Finnerty O, Rauf J, Bergin D, Laffey JG, Mc Donnell JG (2011) Studies on the spread of local anaesthetic solution in transversus abdominis plane blocks. Anaesthesia. 66:1023e1030. [CrossRef]

- J.P. Rathmell, T.R. Lair, B. Nauman (2005) The role of intrathecal drugs in the treatment of acute pain. Anesth Analg. 101 (5): S30-S43. [CrossRef]

- Meylan N, Elia N, Lysakowski C, Tramer MR (2009)Benefit and risk of intrathecal morphine without local anaesthetic in patients undergoing major surgery: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 102(2):156–67. [CrossRef]

- Koning, Mark V.; Klimek, Markus; Rijs, Koen; Stolker, Robert J.; Heesen, Michael A. (2020). Intrathecal hydrophilic opioids for abdominal surgery: a meta-analysis, meta-regression, and trial sequential analysis. Br J Anaesth. 125(3): 358-72. [CrossRef]

- Abdallah FW, Chan VW, Brull R (2012) Transversus abdominis plane block: a systematic review. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 37(2):193-209. [CrossRef]

- Charlton S, Cyna AM, Middleton P, Griffiths JD (2010) Perioperative transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks for analgesia after abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (12): CD007705. [CrossRef]

- Johns N, O’Neill S, Ventham NT, Barron F, Brady RR, Daniel T (2012) Clinical effectiveness of transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block in abdominal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 14(10):e635–42. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths JD, Middle JV, Barron FA, Grant SJ, Popham PA, Royse CF (2010) Transversus abdominis plane block does not provide additional benefit to multimodal analgesia in gynecological cancer surgery. Anesth Analg 111(3): 797-801. [CrossRef]

- Mongelli F, Marengo M, Bertoni MV, et al (2023)Laparoscopic-assisted transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block versus port-site infltration with local anesthetics in bariatric surgery: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Obes Surg. 33(11):3383-90. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. H. W.; Barrington, M. J.; Tran, T. M. N.; Wong, D.; Hebbard, P. D (2010). Comparison of Extent of Sensory Block following Posterior and Subcostal Approaches to Ultrasound-Guided Transversus Abdominis Plane Block. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, 38(3), 452–460. [CrossRef]

- Tran TM, Ivanusic JJ, Hebbard P, Barrington MJ (2009) Determination of spread of injectate after ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block: a cadaveric study. Br J Anaesth 102(1):123-7. [CrossRef]

- Boisen ML, McQuaid AJ, Esper SA, Holder M, Jennifer Z, Amer H. H, et al. (2019) Intrathecal Morphine Versus Nerve Blocks in an Enhanced Recovery Pathway for Pancreatic Surgery. Journal of Surgical Research, 244: 15–22. [CrossRef]

- Glare P, Aubrey KR, Myles PS (2019) Transition from acute to chronic pain after surgery. Lancet.393(10180):1537-46. [CrossRef]

- Gehling M, Tryba M (2009) Risks and side-effects of intrathecal morphine compined with spinal anaesthesia: A meta-analysis. Anaesthesia 64(6):643-51. [CrossRef]

- Khaled Mohamed Fares, Sahar Abdel-Baky Mohamed, Hala Saad Abdel-Ghaffar (2014) High Dose Intrathecal Morphine for Major Abdominal Cancer Surgery: A Prospective Double-Blind, Dose-Finding Clinical Study. Pain Physician 17(3):255-64.

- P. Kjolhede, O. Bergdahl, N. Borendal Wodlin, L (2019) NilssonEffect of intrathecal morphine and epidural analgesia on postoperative recovery after abdominal surgery for gynecologic malignancy: an open-label randomised trial.BMJ. 9(3): e024484. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).