Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

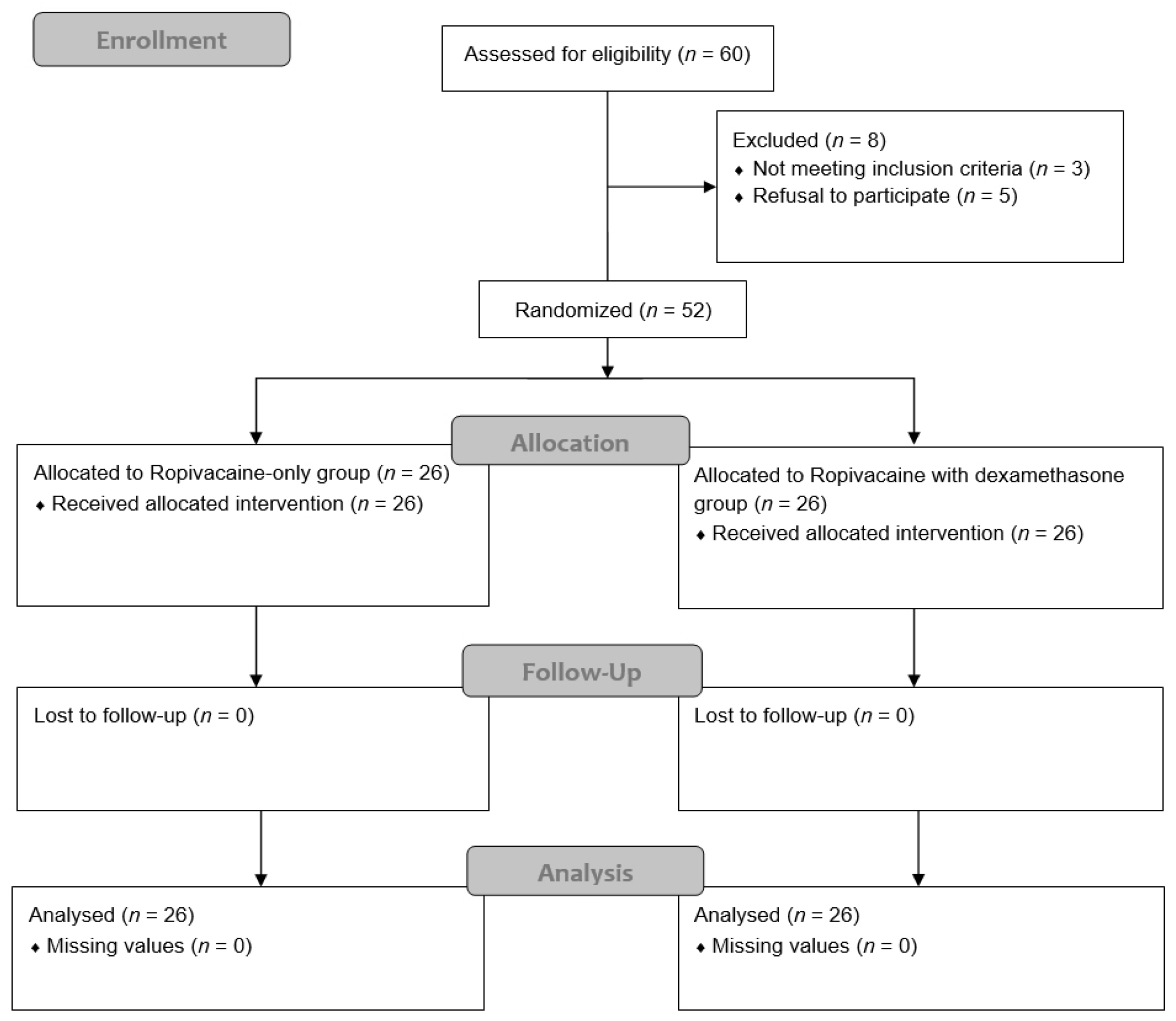

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Randomization

2.3. Anesthesia

2.4. Rectus Sheath Block Technique

2.5. Postoperative Pain Management

2.6. Outcome Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Primary Outcomes

3.2. Secondary Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NSAIDs | nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| PNB | peripheral nerve block |

| PONV | postoperative nausea and vomiting |

| RSB | rectus sheath block |

| TAP | transversus abdominis plane |

| PACU | post-anesthesia care unit |

| NRS | numeric rating scale |

| IV-PCA | intravenous patient-controlled analgesia |

References

- Howle, R.; Ng, S.C.; Wong, H.Y.; Onwochei, D.; Desai, N. Comparison of analgesic modalities for patients undergoing midline laparotomy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth 2022, 69, 140–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.R.; Baig, M.A.; Brito, V.; Bader, F.; Bergman, M.I.; Alfonso, A. Postoperative pulmonary complications after laparotomy. Respiration 2010, 80, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, D.; El-Sharkawy, A.M.; Psaltis, E.; Maxwell-Armstrong, C.A.; Lobo, D.N. Postoperative ileus: Recent developments in pathophysiology and management. Clin Nutr 2015, 34, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, R. Opioids and cancer recurrence. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2014, 8, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, G.L.; Greenberg, S. Effect of anaesthetic technique and other perioperative factors on cancer recurrence. Br J Anaesth 2010, 105, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, F.; Chung, F. Minimizing perioperative adverse events in the elderly. Br J Anaesth 2001, 87, 608–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.J.; Ventham, N.T.; McNally, S.; Harrison, E.; Wigmore, S. Analgesia after open abdominal surgery in the setting of enhanced recovery surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg 2014, 149, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, M.J.; Krishnan, S.; Chen, C.Y. Postoperative analgesia for shoulder surgery: a critical appraisal and review of current techniques. Anaesthesia 2010, 65, 608–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, F.W.; Halpern, S.H.; Aoyama, K.; Brull, R. Will the Real Benefits of Single-Shot Interscalene Block Please Stand Up? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Anesth Analg 2015, 120, 1114–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavand’homme, P. Rebound pain after regional anesthesia in the ambulatory patient. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2018, 31, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, G.S.; Bailey, J.G.; Sardinha, J.; Brousseau, P.; Uppal, V. Factors associated with rebound pain after peripheral nerve block for ambulatory surgery. Br J Anaesth 2021, 126, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swain, A.; Nag, D.S.; Sahu, S.; Samaddar, D.P. Adjuvants to local anesthetics: Current understanding and future trends. World J Clin Cases 2017, 5, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Rodseth, R.; McCartney, C.J. Effects of dexamethasone as a local anaesthetic adjuvant for brachial plexus block: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth 2014, 112, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.M.; Marret, E.; Bonnet, F. Combination of dexamethasone and local anaesthetic solution in peripheral nerve blocks: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2015, 32, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawanishi, R.; Yamamoto, K.; Tobetto, Y.; Nomura, K.; Kato, M.; Go, R.; Tsutsumi, Y.M.; Tanaka, K.; Takeda, Y. Perineural but not systemic low-dose dexamethasone prolongs the duration of interscalene block with ropivacaine: a prospective randomized trial. Local Reg Anesth 2014, 7, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakae, T.M.; Marchioro, P.; Schuelter-Trevisol, F.; Trevisol, D.J. Dexamethasone as a ropivacaine adjuvant for ultrasound-guided interscalene brachial plexus block: A randomized, double-blinded clinical trial. J Clin Anesth 2017, 38, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Xing, M.; Jiang, S.; Zou, W. Effect of Intravenous Dexamethasone on Postoperative Pain in Patients Undergoing Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain Physician 2022, 25, E169–E183. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.P.; Makkar, J.K.; Yadav, N.; Goudra, B.G.; Singh, P.M. The analgesic efficacy of intravenous dexamethasone for post-caesarean pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2022, 39, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, R.; Popping, D.M. Is epidural analgesia still a viable option for enhanced recovery after abdominal surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2018, 31, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popping, D.M.; Elia, N.; Van Aken, H.K.; Marret, E.; Schug, S.A.; Kranke, P.; Wenk, M.; Tramer, M.R. Impact of epidural analgesia on mortality and morbidity after surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg 2014, 259, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.G.; Morgan, C.W.; Christie, R.; Ke, J.X.C.; Kwofie, M.K.; Uppal, V. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks compared to thoracic epidurals or multimodal analgesia for midline laparotomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J Anesthesiol 2021, 74, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, G.; Sehmbi, H.; Retter, S.; Bailey, J.G.; Tablante, R.; Uppal, V. Comparative efficacy and safety of non-neuraxial analgesic techniques for midline laparotomy: a systematic review and frequentist network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Anaesth 2023, 131, 1053–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozen, W.M.; Tran, T.M.; Ashton, M.W.; Barrington, M.J.; Ivanusic, J.J.; Taylor, G.I. Refining the course of the thoracolumbar nerves: a new understanding of the innervation of the anterior abdominal wall. Clin Anat 2008, 21, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandeman, D.J.; Dilley, A.V. Ultrasound-guided rectus sheath block and catheter placement. ANZ J Surg 2008, 78, 621–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osaka, Y.; Kashiwagi, M.; Nagatsuka, Y.; Oosaku, M.; Hirose, C. [Ultrasound-guided rectus sheath block for upper abdominal surgery]. Masui 2010, 59, 1039–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, D.; Martinez, V. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia in patients after surgery: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2014, 112, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.H.; Lee, H.J.; Oh, H.W.; Lee, J.W.; Baik, H.J.; Kim, Y.J. Perineural dexamethasone reduces rebound pain after ropivacaine single injection interscalene block for arthroscopic shoulder surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2021, 46, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melesse, D.Y.; Chekol, W.B.; Tawuye, H.Y.; Denu, Z.A.; Agegnehu, A.F. Assessment of the analgesic effectiveness of rectus sheath block in patients who had emergency midline laparotomy: Prospective observational cohort study. International Journal of Surgery Open 2020, 24, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, H.M.; Abd Elmoneim, A.T.; El Moutaz, H. The Analgesic Efficiency of Ultrasound-Guided Rectus Sheath Analgesia Compared with Low Thoracic Epidural Analgesia After Elective Abdominal Surgery with a Midline Incision: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesth Pain Med 2017, 7, e14244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Kim, H.; Park, J. Analgesic effectiveness of rectus sheath block during open gastrectomy: A prospective double-blinded randomized controlled clinical trial. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98, e15159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbahrawy, K.; El-Deeb, A. Rectus sheath block for postoperative analgesia in patients with mesenteric vascular occlusion undergoing laparotomy: A randomized single-blinded study. Anesth Essays Res 2016, 10, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashandy, G.M.; Elkholy, A.H. Reducing postoperative opioid consumption by adding an ultrasound-guided rectus sheath block to multimodal analgesia for abdominal cancer surgery with midline incision. Anesth Pain Med 2014, 4, e18263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; An, R.; Zhou, J.; Yang, B. Clinical analgesic efficacy of dexamethasone as a local anesthetic adjuvant for transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block: A meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0198923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, E.; Kern, C.; Kirkham, K.R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of perineural dexamethasone for peripheral nerve blocks. Anaesthesia 2015, 70, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, K.J.; McDonnell, J.G.; Carvalho, B.; Sharkey, A.; Pawa, A.; Gadsden, J. Essentials of Our Current Understanding: Abdominal Wall Blocks. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2017, 42, 133–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, M.; Fukushima, T.; Shoji, K.; Momosaki, R.; Mio, Y. Preoperative versus postoperative ultrasound-guided rectus sheath block for acute postoperative pain relief after laparoscopy: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024, 103, e37597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moiniche, S.; Kehlet, H.; Dahl, J.B. A qualitative and quantitative systematic review of preemptive analgesia for postoperative pain relief: the role of timing of analgesia. Anesthesiology 2002, 96, 725–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Clarke, H.; Seltzer, Z. Review article: Preventive analgesia: quo vadimus? Anesth Analg 2011, 113, 1242–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, T.J.; Taylor, B.K. Analgesic treatment before incision compared with treatment after incision provides no improvement in postoperative pain relief. The Journal of Pain 2000, 1, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogatzki-Zahn, E.M.; Zahn, P.K. From preemptive to preventive analgesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2006, 19, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, T.J.; Kehlet, H. Preventive analgesia to reduce wound hyperalgesia and persistent postsurgical pain: not an easy path. Anesthesiology 2005, 103, 681–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S.D.; Armstrong, K.; Chin, K.J. Perineural entrapment of an interscalene stimulating catheter. Anaesth Intensive Care 2012, 40, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowens, C., Jr.; Briggs, E.R.; Malchow, R.J. Brachial plexus entrapment of interscalene nerve catheter after uncomplicated ultrasound-guided placement. Pain Med 2011, 12, 1117–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.S.; Matava, M.J.; Wright, R.W.; Brophy, R.H.; Smith, M.V. Interscalene brachial plexus block for arthroscopic shoulder surgery: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013, 95, 1318–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.S.; Lai, H.C.; Jhou, H.J.; Chan, W.H.; Chen, P.H. Rebound pain prevention after peripheral nerve block: A network meta-analysis comparing intravenous, perineural dexamethasone, and control. J Clin Anesth 2024, 99, 111657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pehora, C.; Pearson, A.M.; Kaushal, A.; Crawford, M.W.; Johnston, B. Dexamethasone as an adjuvant to peripheral nerve block. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 11, CD011770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, E.; Renard, Y.; Desai, N. Intravenous versus perineural dexamethasone to prolong analgesia after interscalene brachial plexus block: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Br J Anaesth 2024, 133, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishido, H.; Kikuchi, S.; Heckman, H.; Myers, R.R. Dexamethasone decreases blood flow in normal nerves and dorsal root ganglia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002, 27, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attardi, B.; Takimoto, K.; Gealy, R.; Severns, C.; Levitan, E.S. Glucocorticoid induced up-regulation of a pituitary K+ channel mRNA in vitro and in vivo. Recept Channels 1993, 1, 287–293. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, A.; Hao, J.; Sjolund, B. Local corticosteroid application blocks transmission in normal nociceptive C-fibres. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1990, 34, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, K.; Elkassabany, N.M.; Liu, J. Dexamethasone as adjuvant to bupivacaine prolongs the duration of thermal antinociception and prevents bupivacaine-induced rebound hyperalgesia via regional mechanism in a mouse sciatic nerve block model. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0123459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zufferey, P.J.; Chaux, R.; Lachaud, P.A.; Capdevila, X.; Lanoiselee, J.; Ollier, E. Dose-response relationships of intravenous and perineural dexamethasone as adjuvants to peripheral nerve blocks: a systematic review and model-based network meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2024, 132, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, T.J.; Belani, K.G.; Bergese, S.; Chung, F.; Diemunsch, P.; Habib, A.S.; Jin, Z.; Kovac, A.L.; Meyer, T.A.; Urman, R.D.; et al. Fourth Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Anesth Analg 2020, 131, 411–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ropivacaine-only group (n = 26) | Ropivacaine with dexamethasone group (n = 26) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 68.50 [8.50] | 67.50 [9.25] | 0.275 |

| Height (cm) | 167.00 [9.65] | 167.10 [8.98] | 0.498 |

| Weight (kg) | 66.66 ± 11.86 | 65.66 ± 10.17 | 0.745 |

| Sex (M/F) | 21 (81) / 5 (19) | 21 (81) / 5 (19) | 1.000 |

| Operation time (min) | 252.50 [61.25] | 225.00 [31.25] | 0.184 |

| Anesthesia time (min) | 287.50 [67.50] | 265.00 [33.75] | 0.152 |

| ASA (1/2/3) | 0 (0) / 23 (88) / 3 (12) | 3 (11) /21 (81) / 2 (8) | 0.193 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (27) | 9 (35) | 0.548 |

| Hypertension | 16 (62) | 13 (50) | 0.402 |

| Pulmonary disease | 1 (4) | 3 (12) | 0.298 |

| Intraoperative fentanyl (µg) | 100.00 [50.00] | 100.00 [50.00] | 0.627 |

| Ropivacaine-only group (n = 26) | Ropivacaine with dexamethasone group (n = 26) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total fentanyl dose (µg) | |||

| Postoperative 3 h | 101.70 [43.05] | 84.44 [33.72] | 0.164 |

| Postoperative 6 h | 179.20 [138.60] | 148.50 [100.03] | 0.059 |

| Postoperative 12 h | 294.95 [173.48] | 247.95 [131.98] | 0.041 |

| Postoperative 18 h | 420.35 [259.30] | 359.80 [140.50] | 0.022 |

| Postoperative 24 h | 521.50 [332.58] | 459.80 [175.42] | 0.032 |

| Postoperative 48 h | 913.70 [246.95] | 806.30 [300.45] | 0.024 |

| Numeric rating scale | |||

| Postoperative 3 h | 2.00 [2.00] | 2.00 [1.00] | 0.113 |

| Postoperative 6 h | 6.00 [2.25] | 4.50 [2.25] | 0.002 |

| Postoperative 12 h | 5.00 [2.00] | 3.00 [2.00] | 0.000 |

| Postoperative 18 h | 4.00 [2.00] | 3.00 [2.00] | 0.057 |

| Postoperative 24 h | 3.00 [1.50] | 2.50 [1.25] | 0.024 |

| Postoperative 48 h | 2.00 [2.25] | 1.00 [1.00] | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).