Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objectives: To assess the feasibility and effectiveness of a perioperative opioid-sparing anesthesia-analgesia (OSA-A) technique without regional nerve blocks compared to standard opi-oid-based technique (OBA-A) in open thoracotomies. Methods: This retrospective, propensi-ty-matched, case-control study was conducted at a university hospital from January 2017 to Feb-ruary 2021, including adult patients undergoing open thoracotomy for lung or pleura pathology. Sixty patients in the OSA-A group were matched with 40 in the OBA-A group. Outcomes included postoperative pain scores on days 0, 1, and 2; 24-hour postoperative morphine consumption; PACU and hospital length of stay; time to bowel movement; and rates of nausea and vomiting. Results: Of 120 eligible patients, 100 had complete records (60 OSA-A, 40 OBA-A). Demographics were similar, but ASA status scores were higher in the OBA-A group. The OSA-A group reported significantly lower pain levels at rest, during cough, and on movement on the first two postoperative days, shorter PACU stay, and required fewer opioids. They also had better gastrointestinal motility (p<0.0001) and lower rates of nausea and vomiting on postoperative days 1 and 2. A follow-up study with 68 patients (46 OSA-A, 22 OBA-A) assessing chronic pain prevalence found no signif-icant differences between the groups. Conclusions: OSA-A without regional nerve blocks for open thoracotomies is feasible and safe, improving postoperative pain management, reducing opioid consumption, shortening PACU stay, and enhancing early gastrointestinal recovery compared to OBA-A.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Anesthesia-Analgesia Management

| OBA-A Group | OSA-A Group | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Premedication Night before surgery |

Anxiolysis Bromazepam 1.5 mg orally (po) | Pregabalin 25-150 mg po Amitriptyline 10 mg po |

Pregabalin tailored to patients’ needs / status Low-dose Amitriptyline for its antinociceptive and anti-salivary actions, if not contraindicated due to patients’ comorbidities |

| Premedication Day of surgery |

Midazolam 0.05 mg/kg intramuscularly (im) |

Pregabalin 25-150 mg po Amitriptyline 10 mg po |

|

| Anesthesia Induction | intravenously (iv) iv Fentanyl 150-200 mcg |

iv Dexmedetomidine loading dose 1 mcg/kg administrated over 15 minutes | |

| iv Propofol 2-2.5 mg/kg | iv Midazolam 2-5 mg | ||

| iv Rocuronium 0.6 mg/kg (1.2 mg/kg if RSI) | iv Ketamine 0.5-1.0 mg/kg | ||

| Or | iv Propofol 1-2 mg/kg | ||

| iv Cis-Atracurium 0.2 mg/kg | iv Lidocaine 1mg/kg | ||

| *Surgical site infiltration prior to incision with Ropivacaine (10-15 ml Ropivacaine 0.75%) | iv Rocuronium 0.6 mg/kg (1.2 mg/kg if RSI) | ||

| iv Magnesium Sulphate 30-40 mg/kg as bolus over 15 minutes | |||

| iv Dexamethasone 8-16 mg | |||

| *Surgical site infiltration prior to incision with Ropivacaine (10-15 ml Ropivacaine 0.75%) | |||

| Prior to incision | iv Fentanyl 50-100mcg | iv Dexmedetomidine infusion 0.6-1.2 mcg/kg/h | |

| Or | iv Lidocaine infusion 1mg/kg/h | ||

| iv Remifentanil infusion 0.05-0.25 mcg/kg/h | iv Paracetamol 1gr | ||

| iv NSAID (Parecoxib 40 mg or Dexketoprofen 50 mg) | |||

| Anesthesia maintenance | Volatile anesthesia | Volatile anesthesia | |

| Intraoperative antinociception | iv Remifentanil infusion 0.05-0.25 mcg/kg/h | iv Lidocaine infusion 0.5-1mg/kg/h | |

| Or | iv Dexmedetomidine 0.4-1mcg/kg/h | ||

| iv boluses of Fentanyl 50-100 mcg as required | iv boluses of 20-30 mg of Ketamine as required | ||

| iv bolus of 2.5 g Magnesium sulphate | |||

| 20 minutes prior to surgical closure | iv NSAID if no contraindication (Parecoxib 40 mg or Dexketoprofen 50 mg) |

iv bolus of 20-30 mg of Ketamine | |

| iv Paracetamol 1 g | iv Tramadol 100 mg | ||

| iv Morphine 0.05-0.15 mg/kg | |||

| PACU | iv bolus of morphine 2 mg | iv Ketamine 30-50 mg | If patient’s pain score at rest ≥6 in the numerical rating scale score 0-10 |

| ± iv Magnesium sulphate 2.5 g | |||

| ± iv Midazolam 1-2 mg | |||

| iv Pethidine 20-30 mg | iv Pethidine 20-30 mg | If shivering | |

| iv Tramadol 100 mg | Rescue therapy | ||

| Surgical Ward 48 hours after surgery |

iv Paracetamol 1gr every 8 hours | iv Paracetamol 1gr every 8 hours | |

| iv PCA morphine morphine (solution 0.5 mg/ml) with an infusion rate 0.5-1mg/h and possibility of bolus 1 mg every 10 minutes, if no contraindication, under continuous monitoring with pulse oximetry | iv Tramadol (max daily dose 300 mg) | ||

| po Pregabalin 25-150 mg daily dose, given in titrated doses | |||

| Rescue therapy: im Pethidine 50-75mg |

| Total Daily Dose (IV) | Morphine Equivalent Dose (mg) |

|---|---|

| 1 mcg fentanyl iv | 0.066 mg morphine iv |

| 1 mg oxycodone iv | 1.5 mg morphine iv |

| 1 mg tramadol | 0.1 mg morphine iv |

| 1 mg pethidine iv | 0.13 mg morphine iv |

2.3. Study Outcomes

2.3.1. Pain and Opioid Consumption

2.3.2. Other Outcomes

- How would you assess your pain now, at this moment? (0-10)

- How severe was the worst pain during the past 4 weeks (0-10)

- How severe was the pain during the past 4 weeks on average? (0-10)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics

| Characteristic | OSA-A(x̅ ± SD) | OBA-A(x̅ ± SD) | P-Value | Statistical Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 62.55 ± 11.29 | 63.73 ± 12.55 | 0.3249 | Mann-Whitney U test | |

| Weight (kg) | 79.50 ± 15.33 | 77.43 ± 13.28 | 0.4864 | Unpaired two-tailed t test | |

| Height (m) | 1.698 ± 0.07095 | 1.678 ± 0.08057 | 0.1996 | Unpaired two-tailed t test | |

| BMI (kg *m-2) | 27.56 ± 5.050 | 27.40 ± 3.751 | 0.9511 | Mann-Whitney U test | |

| Sex | Male | 48 | 28 | 0.3394 | Fisher’s exact test two-sided |

| Female | 12 | 12 | |||

| ASA status | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.0208 | Fisher’s exact test two-sided |

| 2 | 39 | 16 | |||

| 3 | 21 | 22 | |||

| 4 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Type of surgery | Lobectomy | 39 | 23 | 0.3728 | Fisher’s exact test two-sided |

| Segmentectomy | 14 | 12 | |||

| Pneumonectomy | 3 | 0 | |||

| Other (biopsy, talc pleurodesis e.t.c.) | 4 | 5 | |||

| Depression | Yes | 7 | 7 | 0.5576 | Fisher’s exact test two-sided |

| No | 53 | 33 | |||

| Anxiety | Yes | 20 | 11 | 0.6599 | Fisher’s exact test two-sided |

| No | 40 | 29 | |||

| Alcohol Use Disorder | Yes | 6 | 1 | 0.2375 | Fisher’s exact test two-sided |

| No | 54 | 39 | |||

| Preoperative chronic pain medication use | Yes | 13 | 3 | 0.0930 | Fisher’s exact test two-sided |

| No | 47 | 37 | |||

| Preoperative chronic opioid use | Yes | 3 | 1 | 0.6479 | Fisher’s exact test two-sided |

| No | 57 | 39 | |||

| Preoperative Steroid use (6 months) | Yes | 5 | 0 | 0.0813 | Fisher’s exact test two-sided |

| No | 55 | 40 |

3.2. Primary Outcome

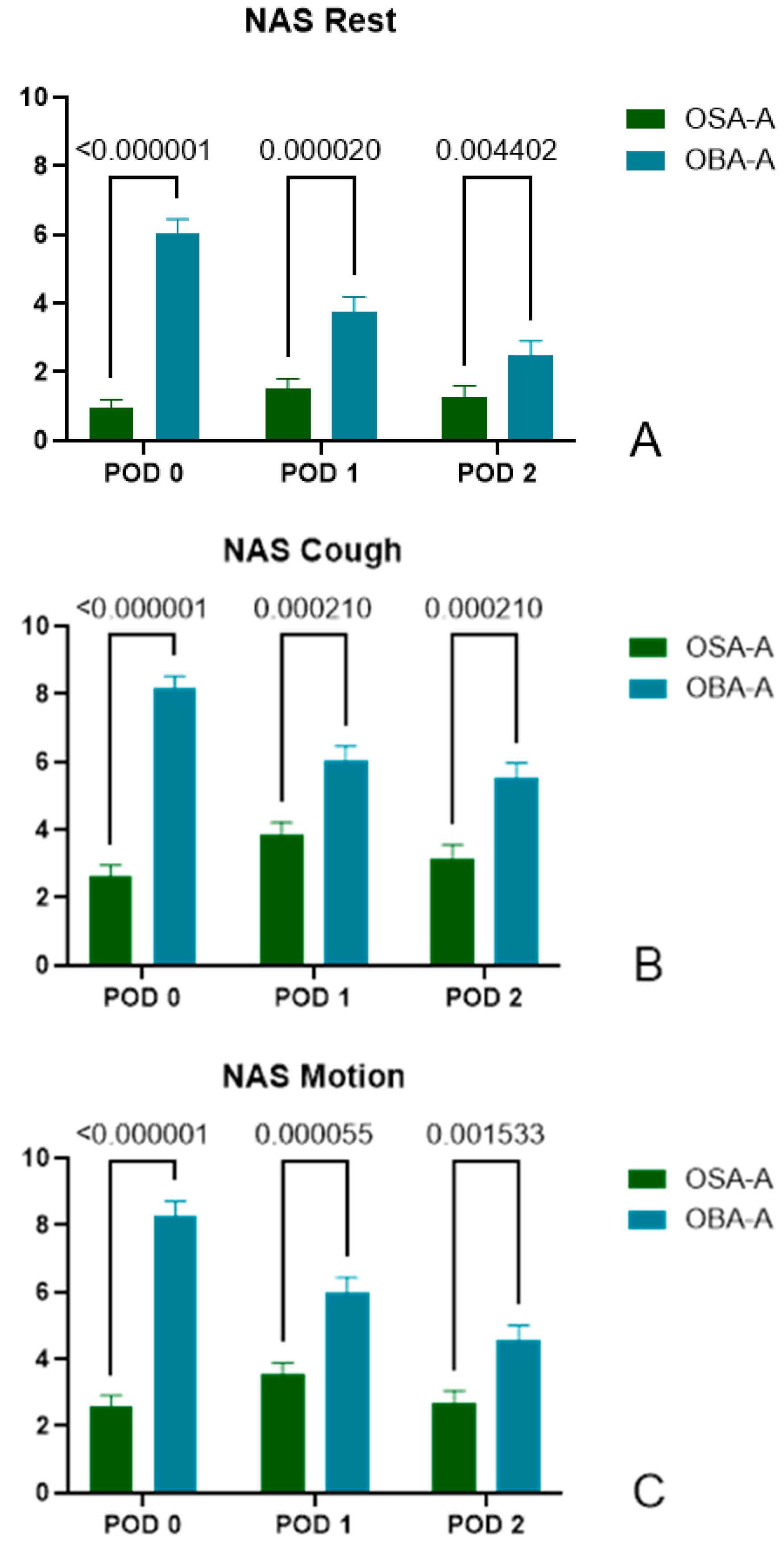

3.2.1. Pain Assessment

3.2.2. Pain Score at Rest

- POD0: (OSA-A) 0.95±1.92, n=60 vs (OBA-A) 6.05±2.56, n=40, p<0.000001

- POD1: (OSA-A) 1.53±2.12, n=57 vs (OBA-A) 3.78±2.66, n=40, p=0.000020

- POD2: (OSA-A) 1.28±2.34, n=54 vs (OBA-A) 2.47±2.57, n=34, p=0.004402

3.2.3. Pain Score During Cough

- POD0: (OSA-A) 2.62±2.67, n=60 vs (OBA-A) 8.18±2.14, n=39, p<0.000001

- POD1: (OSA-A) 3.84±2.83, n=57 vs (OBA-A) 6.03±2.78, n=40, p=0.000210

- POD2: (OSA-A) 3.15±2.99, n=54 vs (OBA-A) 5.51±2.65, n=35, p=0.000210

3.2.4. Pain Score During Motion

- POD0: (OSA-A) 2.58±2.49, n=60 vs (OBA-A) 8.29±2.65, n=38, p<0.000001

- POD1: (OSA-A) 3.54±2.61, n=57 vs (OBA-A) 5.98±2.92, n=40, p=0.000055

- POD2: (OSA-A) 2.69±2.70, n=54 vs (OBA-A) 4.54±2.76, n=35, p=0.001533

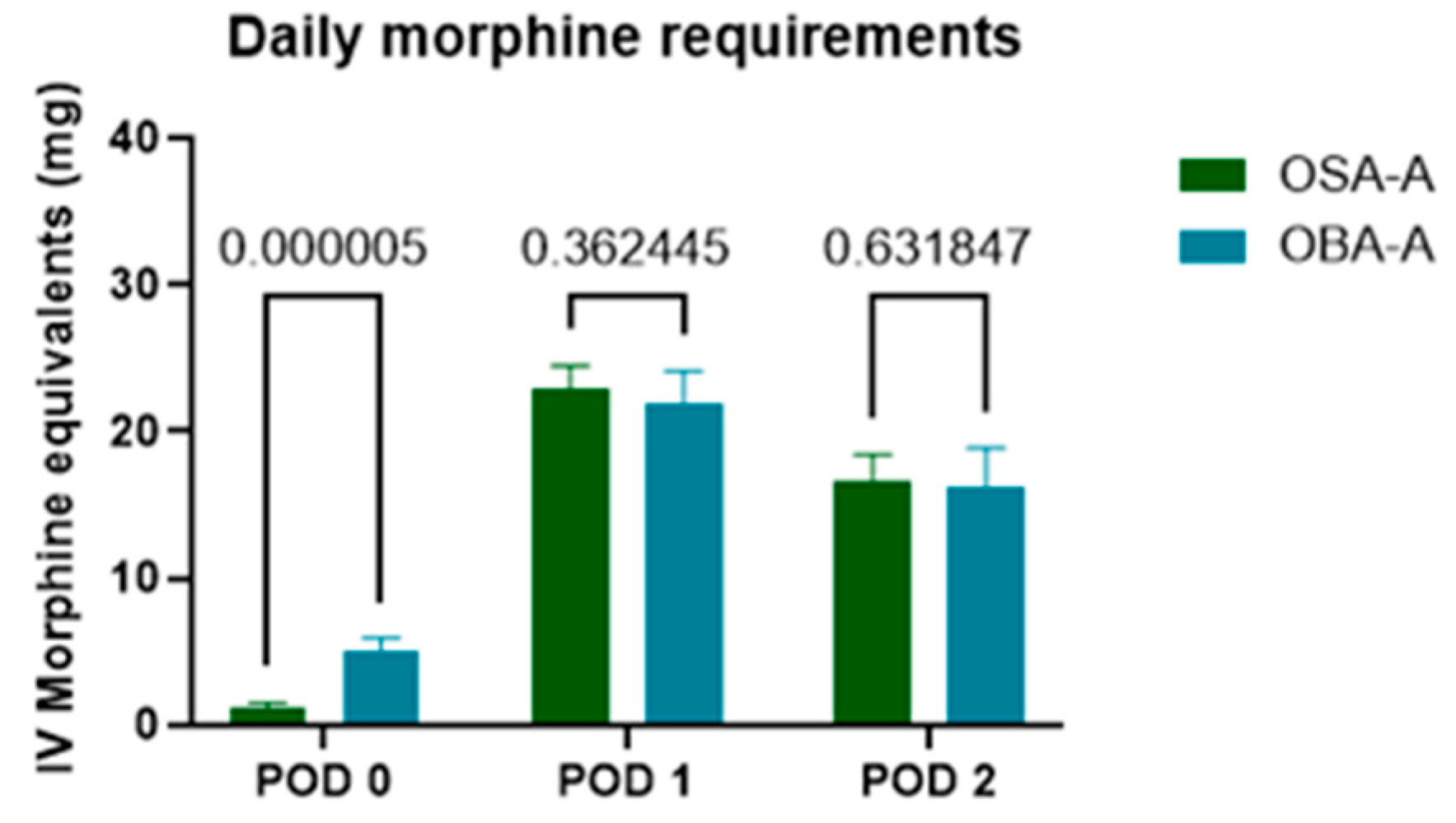

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

3.3.1. PACU and Hospital Length of Stay

| Secondary Outcome | OSA-A (x̅ ± SD) |

OBA-A (x̅ ± SD) |

P-value | Statistical test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of stay PACU (h) | 2.030 ± 1.022 | 3.125 ± 1.036 | <0.0001 | Mann-Whitney U test | |

| Length of stay Hospital (d) | 5.767 ± 3.451 | 5.725 ± 2.050 | 0.2669 | Mann-Whitney U test | |

| Analgesics Requested PACU (POD 0) |

Yes | 21 | 27 | 0.0021 | Fisher’s exact test |

| No | 39 | 13 | |||

| Analgesics Requested POD 1 | Yes | 3 | 2 | >0.9999 | Fisher’s exact test |

| No | 57 | 38 | |||

| Analgesics Requested POD 2 | Yes | 1 | 0 | >0.9999 | Fisher’s exact test |

| No | 59 | 40 | |||

| Morphine (mg) Equivalents Delivered | PACU | 1.177 ± 2.929 | 5.031 ± 5.705 | 0.000005 | Multiple Mann-Whitney U tests correcting for multiple comparisons by using the FDR method |

| POD1 | 22.863 ± 12.760 | 21.878 ± 14.288 | 0.362445 | ||

| POD2 | 16.542 ± 14.723 | 16.234 ± 16.661 | 0.631847 | ||

| Intestinal Mobilization POD 1 | Yes | 51 | 8 | <0.0001 | Fisher’s exact test |

| No | 9 | 32 | |||

| Intestinal Mobilization POD 2 | Yes | 58 | 22 | <0.0001 | Fisher’s exact test |

| No | 2 | 18 | |||

| Nausea & Vomiting POD 1 | Yes | 1 | 5 | 0.0363 | Fisher’s exact test |

| No | 59 | 35 | |||

| Nausea & Vomiting POD 2 | Yes | 0 | 4 | 0.0204 | Fisher’s exact test |

| No | 60 | 34 |

3.3.2. Rescue Analgesia and Morphine Consumption in PACU and on POD1 and POD2

3.3.3. Gastrointestinal Motility

3.3.4. Nausea-Vomiting

3.3.5. Chronic Pain

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSA-A | Opioid-Sparing Anesthesia-Analgesia |

| OBA-A | Opioid-Based Anesthesia-Analgesia |

| PACU | Post Anesthesia Care Unit |

| PTPS | Post-Thoracotomy Pain Syndrome |

| MED | Morphine Equivalent Dose |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiology |

| RSI | Rapid Sequence Induction |

| NSAID | Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug |

| PCA | Patient Controlled Analgesia |

| POD | Post-Operative Day |

| NRS | Numerical Rate Scale |

| ANOVA | ANalysis Of VAriance |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| VATS | Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery |

| OFA | Opioid-Free Anesthesia |

| OSA | Opioid-Sparing Anesthesia |

| OBA | Opioid-Based Anesthesia |

| PVB | ParaVertebral Block |

| SAPB | Serratus Anterior Plane Block |

| ESPB | Erector Spinae Plane Block |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| NMDA | N-Methyl-D-aspartic Acid |

| CPTP | chronic post-thoracotomy pain |

| ICD | International Classification of Disease |

References

- Schwarzova, K.; Whitman, G.; Cha, S. Developments in Postoperative Analgesia in Open and Minimally Invasive Thoracic Surgery Over the Past Decade. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2024, 36, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, M.; Oger, S.; Bedon-Carte, S.; Vielstadte, C.; Leo, F.; Zaouter, C.; Ouattara, A. Effect of Opioid-Free Anaesthesia on Postoperative Epidural Ropivacaine Requirement After Thoracic Surgery: A Retrospective Unmatched Case-Control Study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2019, 38, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesbah, A.; Yeung, J.; Gao, F. Pain after Thoracotomy. BJA Education. 2016, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, S.; Böhmer, A.B.; Poels, M.; Schieren, M.; Koryllos, A.; Wappler, F.; Joppich, R. Post-thoracotomy pain syndrome: Seldom severe, often neuropathic, treated unspecific, and insufficient. Pain Rep. 2020, 5, e810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayman, E.O.; Brennan, T.J. Incidence and severity of chronic pain at 3 and 6 months after thoracotomy: Meta-analysis. J Pain. 2014, 15, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, C.; Ørding, H.; Licht, P.B.; Toft, P. From acute to chronic pain after thoracic surgery: The significance of different components of the acute pain response. J Pain Res. 2018, 11, 1541–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, T. What Is the Best Pain Control after Thoracic Surgery? J Thorac Dis. 2018, 10, 1335–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ercole, F.; Arora, H.; Kumar, P.A. for Thoracic Surgery. Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018, 32, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.A.; Caplan, R.A.; Stephens, L.S.; et al. Postoperative opioid-induced respiratory depression: A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 2015, 122, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Nguyen, D.T.; Lichtenberg, Z.K.; Rizk, E.; Meisenbach, L.M.; Chihara, R.; Graviss, E.A.; Kim, M.P. Opioid use in thoracic surgery: A retrospective study on postoperative complications. J Thorac Dis. 2024, 16, 6827–6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, J.; Hwang, W. The Role of Anesthetic Management in Lung Cancer Recurrence and Metastasis: A Comprehensive Review. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauermann, E.; Ruppen, W.; Bandschapp, O. Different protocols used today to achieve total opioid-free general anesthesia without locoregional blocks. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2017, 31, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://esaic.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/conversion-tables-for-iv-and-oral-analgesics.pdf.

- Freynhagen, R.; Baron, R.; Gockel, U.; Tölle, T.R. painDETECT: A new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006, 22, 1911–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, J.D.W.; Cole, C.M.W.; Lo, W.; Ura, M. Postoperative Pain in Thoracic Surgical Patients: An Analysis of Factors Associated With Acute and Chronic Pain. Heart Lung Circ. 2021, 30, 1244–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S. Post-operative pulmonary complications after thoracotomy. Indian J Anaesth. 2015, 59, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patvardhan, C.; Ferrante, M. Opiate free anaesthesia and future of thoracic surgery anaesthesia. Journal of Visualized Surgery 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzova, K.; Whitman, G.; Cha, S. Developments in Postoperative Analgesia in Open and Minimally Invasive Thoracic Surgery Over the Past Decade. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2024, 36, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Barucco, G.; Licheri, M.; Valsecchi, G.; Zaraca, L.; Mucchetti, M.; Zangrillo, A.; Monaco, F. Opioid Free Anesthesia in Thoracic Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 6955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Nguyen, D.T.; Lichtenberg, Z.K.; Rizk, E.; Meisenbach, L.M.; Chihara, R.; Graviss, E.A.; Kim, M.P. Opioid use in thoracic surgery: A retrospective study on postoperative complications. J Thorac Dis. 2024, 16, 6827–6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hah, J.M.; Bateman, B.T.; Ratliff, J.; Curtin, C.; Sun, E. Chronic Opioid Use After Surgery: Implications for Perioperative Management in the Face of the Opioid Epidemic. Anesth Analg. 2017, 125, 1733–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltse Nicely, K.L.; Friend, R.; Robichaux, C.; Edwards, J.A.; Cimiotti, J.P.; Dupree Jones, K. Association Between Intra- and Postoperative Opioids in Opioid-Naïve Patients in Thoracic Surgery. Ann Thorac Surg Short Rep. 2024, 2, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chancellor, W.Z.; Mehaffey, J.H.; Desai, R.P.; Beller, J.; Balkrishnan, R.; Walters, D.M.; Martin, L.W. Prolonged Opioid Use Associated With Reduced Survival After Lung Cancer Resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021, 111, 1791–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornasari, D. Pharmacotherapy for Neuropathic Pain: A Review. Pain Ther. 2017, 6 Suppl. 1, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moisset, X. Neuropathic pain: Evidence based recommendations. Presse Med. 2024, 53, 104232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forget, P. Opioid-free anaesthesia. Why and how? A contextual analysis. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2019, 38, 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Guastella, V.; Mick, G.; Soriano, C.; Vallet, L.; Escande, G.; Dubray, C.; Eschalier, A. A prospective study of neuropathic pain induced by thoracotomy: Incidence, clinical description, and diagnosis. Pain. 2011, 152, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homma, T.; Doki, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; et al. Risk factors of neuropathic pain after thoracic surgery. J Thorac Dis 2018, 10, 2898–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humble, S.R.; Dalton, A.J.; Li, L. Interventions to reduce acute and chronic post-surgical pain. EJP 2015, 19, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colvin, L.A.; Bull, F.; Hales, T.G. Perioperative opioid analgesia-when is enough too much? A review of opioid-induced tolerance and hyperalgesia. Lancet. 2019, 393, 1558–1568. [Google Scholar]

- Devine, G.; Cheng, M.; Martinez, G.; Patvardhan, C.; Aresu, G.; Peryt, A.; Coonar, A.S.; Roscoe, A. Opioid-Free Anesthesia for Lung Cancer Resection: A Case-Control Study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020, 34, 3036–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brulotte, V.; Ruel, M.M.; Lafontaine, E.; Chouinard, P.; Girard, F. Impact of Pregabalin on the occurrence of postthoracotomy pain syndrome: A randomized trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015, 40, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabritius, M.L.; Geisler, A.; Petersen, P.L.; Nikolajsen, L.; Hansen, M.S.; Kontinen, V.; Hamunen, K.; Dahl, J.B.; Wetterslev, J.; Mathiesen, O. Gabapentin for post-operative pain management - a systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2016, 60, 1188–1208; Erratum in: Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2017, 61, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalşi, E.; Yakşi, O. Current treatment options for post-thoracotomy pain syndrome: A review. Curr Thorac Surg 2017, 2, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Homma, T.; Doki, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ojima, T.; Shimada, Y.; Kitamura, N.; Akemoto, Y.; Hida, Y.; Yoshimura, N. Efficacy of 50 mg pregabalin for prevention of postoperative neuropathic pain after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery and thoracotomy: A 3-month prospective randomized controlled trial. J Thorac Dis. 2019, 11, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsutani, N.; Kawamura, M. Successful management of postoperative pain with pregabalin after thoracotomy. Surg Today. 2014, 44, 712–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsutani, N.; Dejima, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Kawamura, M. Pregabalin reduces post-surgical pain after thoracotomy: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Surg Today. 2015, 45, 1411–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.C.; Byun, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Ahn, S. Effect of preoperative pregabalin as an adjunct to a multimodal analgesic regimen in video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017, 96, e8644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, H. The efficacy of pregabalin for pain control after thoracic surgery: A meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Surg 2024, 19, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouguelet-Lacoste, J.; La Colla, L.; Schilling, D.; Chelly, J.E. The use of intravenous infusion or single dose of low-dose ketamine for postoperative analgesia: A review of the current literature. Pain Med. 2015, 16, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaei, B.; Jafari, A.; Aghamohammadi, H.; et al. Opioid-sparing effect of preemptive bolus low-dose ketamine for moderate sedation in opioid abusers undergoing extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy: A randomized clinical trial. Anesth Analg 2013 116, 75–80.

- Moyse, D.W.; Kaye, A.D.; Diaz, J.H.; Qadri, M.Y.; Lindsay, D.; Pyati, S. Perioperative Ketamine Administration for Thoracotomy Pain. Pain Physician. 2017, 20, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmid, R.L.; Sandler, A.N.; Katz, J. Use and efficacy of low-dose ketamine in the management of acute postoperative pain: A review of current techniques and outcomes. Pain. 1999, 82, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srebro, D.; Vuckovic, S.; Milovanovic, A.; Kosutic, J.; Vujovic, K.S.; Prostran, M. Magnesium in Pain Research: State of the Art. Curr Med Chem. 2017, 24, 424–434. [Google Scholar]

- Vanstone, R.J.; Rockett, M. Use of atypical analgesics by intravenous infusion (IV) for acute pain: Evidence base for lidocaine, ketamine and magnesium. Anesthesia and Intensive Care Med 2016, 17, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.C.; Yang, S.H.; Liao, S.W.; Yu, C.H.; Liu, M.Y.; Chen, J.Y. Effects of perioperative magnesium on postoperative analgesia following thoracic surgery: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Magnes Res. 2024, 36, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salah Abdelgalil, A.; Shoukry, A.; Kamel, M.; Heikal, A.; Ahmed, N. Analgesic Potentials of Preoperative Oral Pregabalin, Intravenous Magnesium Sulfate, and their Combination in Acute Postthoracotomy Pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain 2019, 35, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Dexmedetomidine: Present and future directions. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2019, 72, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerink, M.A.S.; Struys, M.; Hannivoort, L.N.; Barends, C.R.M.; Absalom, A.R.; Colin, P. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Dexmedetomidine. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2017, 56, 893–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beloeil, H.; Garot, M.; Lebuffe, G.; Gerbaud, A.; Bila, J.; Cuvillon, P.; Dubout, E.; Oger, S.; Nadaud, J.; Becret, A.; et al. Balanced Opioid-free Anesthesia with Dexmedetomidine versus Balanced Anesthesia with Remifentanil for Major or Intermediate Noncardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology. 2021, 134, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; He, J.; Yu, N.; Jia, C.; Wang, S. Mechanisms of Dexmedetomidine in Neuropathic Pain. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wu, M.; Xu, J.; Wu, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, G.; Ma, D. Effects of dexmedetomidine on perioperative stress, inflammation, and immune function: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, K.; Li, D.; Applegate RL 2nd Lubarsky, D.A.; Ji, F.H.; Liu, H. Effect of Dexmedetomidine on Cardiac Surgery-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: A Meta-Analysis With Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020, 34, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, R.D.; Wehrman, J.; Irons, J.; Dieleman, J.; Scott, D.; Shehabi, Y. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of perioperative dexmedetomidine to reduce delirium and mortality after cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2021, 127, e168–e170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, G.E.; Zorrilla-Vaca, A.; Vaporciyan, A.; Mehran, R.; Lasala, J.D.; Williams, W.; Patel, C.; Woodward, T.; Kruse, B.; Joshi, G.; et al. Intraoperative Dexmedetomidine and Ketamine Infusions in an Enhanced Recovery After Thoracic Surgery Program: A Propensity Score Matched Analysis. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2022, 36, 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larue, A.; Jacquet-Lagreze, M.; Ruste, M.; Tronc, F.; Fellahi, J.L. Opioid-free anaesthesia for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: A retrospective cohort study with propensity score analysis. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2022, 41, 101089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, T.; Doi, R.; Matsumoto, K. Post-thoracotomy pain syndrome in the era of minimally invasive thoracic surgery. J Thorac Dis. 2024, 16, 3422–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerner, P. Postthoracotomy pain management problems. Anesthesiol Clin. 2008, 26, 355–367, vii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayman, E.O.; Brennan, T.J. Incidence and severity of chronic pain at 3 and 6 months after thoracotomy: Meta-analysis. J Pain 2014, 15, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersini, K.J.; Andreasen, J.J.; Birthe Dinesen, P.G.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Prevalence, characteristics and impact of the post-thoracotomy pain syndrome on quality of life: A cross-sectional study. J Pain Reli 2015, 4, 1000201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayman, E.O.; Parekh, K.R.; Keech, J.; Selte, A.; Brennan, T.J. A prospective study of chronic pain after thoracic surgery. Anesthesiology 2017, 126, 938–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampe, S.; Geismann, B.; Weinreich, G.; Stamatis, G.; Ebmeyer, U.; Gerbershagen, H.J. The influence of type of anesthesia, perioperative pain, and preoperative health status on chronic pain six months after thoracotomy—A prospective cohort study. Pain Med 2016, 18, pnw230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetmann, F.; Kongsgaard, U.E.; Sandvik, L.; Schou-Bredal, I. Prevalence and predictors of persistent post-surgical pain 12 months after thoracotomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2015, 59, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetmann, F.; Kongsgaard, U.E.; Sandvik, L.; Schou-Bredal, I. Post-thoracotomy pain syndrome and sensory disturbances following thoracotomy at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. J Pain Res 2017, 10, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayman, E.O.; Lennertz, R.; Brennan, T.J. Pain-related limitations in daily activities following thoracic surgery in a United States population. Pain Physician 2017, 20, E367–E378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perttunen, K.; Tasmuth, T.; Kalso, E. Chronic pain after thoracic surgery: A follow-up study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1999, 43, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schug, S.A.; Lavand’homme, P.; Barke, A.; Korwisi, B.; Rief, W.; Treede, R.D. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: Chronic postsurgical or posttraumatic pain. Pain 2019, 160, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Chen, D.; McNicol, E.; Sharma, L.; Varaday, G.; Sharma, A.; et al. Risk factors for persistent pain after breast and thoracic surgeries: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Pain 2022, 163, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compared with nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain is claimed to be the major cause of PPSP after breast and thoracic surgeries.

- Kehlet, H.; Jensen, T.S.; Woolf, C.J. Persistent postsurgical pain: Risk factors and prevention. Lancet 2006, 367, 1618–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).