Introduction

Currently, an increasing number of hospitals have implemented ERAS (Enhanced Recovery after Surgery) programs in numerous surgical processes with the goal of reducing patient functionality loss, thereby decreasing perioperative morbidity, expediting the recovery process, shortening hospital stays, and minimizing healthcare costs(1). During the development of these programs, the importance of anesthetic management in achieving the aforementioned outcomes has become evident, creating the need for a multidisciplinary approach and progressively expanding its application to a large number of procedures(1)(2). A crucial element in the success of these programs is the adequate control of perioperative pain to facilitate patient recovery. Therefore, analgesic techniques must be adapted to different surgical approaches and procedures, aiming to address pain in a multimodal manner. This is the objective of the PROSPECT (Procedure Specific Postoperative Pain Management) guidelines, which, based on evidence, aim to optimize pain treatment in various surgical processes(3)(4)(5)(6)(7)(8)(9)(10)(11). Currently, regional analgesic techniques are a cornerstone in the multimodal management of surgical patients(12)(13). Numerous regional techniques have been described to date, ranging from classic procedures like epidural analgesia to novel fascial blocks. The effectiveness and adverse effects of each technique, depending on the approach and patient characteristics, have been studied by many authors(7)(8)(12)(14)(15)(16)(17).

A classic regional technique, described and used long before the advent of fascial blocks, involves the administration of morphine in the intradural space. This is a simple technique with a low failure rate and few complications. The previously described regional techniques require a higher level of skill, training, and ultrasound equipment for their implementation(18). Morphine is a hydrophilic opioid whose use is currently widespread globally. There are multiple administration routes, including the intradural route, which has a good profile for the treatment of acute postoperative pain. The use of intradural hydrophilic opioids like morphine results in reduced clearance and, therefore, greater persistence of the drug in the cerebrospinal fluid, allowing it to bind to specific receptors located in the gray matter of the spinal cord, providing analgesia over a prolonged period. Additionally, the longer presence in this fluid allows for cephalic migration, which explains the development of side effects, some of which, though infrequent, are severe, such as delayed respiratory depression. This is currently the main reason limiting the use of this technique, as, according to ASA, ESRA, and ASRA guidelines, it requires close monitoring of these patients during the initial hours. The dose of intradural morphine used has been progressively reduced, demonstrating similar analgesic efficacy to higher doses but with a significant reduction in adverse effects(9)(19)(20)(21)(22)(23) .

In our hospital, the use of this regional technique is widespread, creating the need to evaluate, analyze, and share our experience in terms of efficacy and safety.

Material and Methods

After obtaining approval from the local Research Ethics Committee (Date: 02/22/2022, President: Jon Zabaleta Jiménez, Code: GON – MOR – 2021 – 11), we conducted a review of adult patients who underwent major surgery and were administered intrathecal morphine between January 2018 and December 2021. The study variables' data were collected retrospectively from the clinical history and the anesthetic record of each patient included in the study.

The following demographic data of the patients were collected: age (years), sex, weight (kilograms), height (meters), and BMI (kg/m2); respiratory comorbidities and smoking habits were also analyzed. Regarding the anesthetic technique used, the doses of intrathecal morphine administered and the presence of associated complications were recorded. The surgical procedure the patient underwent was also coded. Finally, data related to postoperative complications such as respiratory depression, need for respiratory support, presence of atelectasis, and nausea and vomiting were collected. Additionally, patients who required rescue intravenous morphine during the first 24 postoperative hours were noted.

The technique was performed in all cases with the patient monitored and under conscious sedation, using a 25-gauge needle in the interlaminar space between the second and third or third and fourth lumbar vertebrae (L3 and L4 or L2 and L3). The dose of intradural morphine administered was determined based on the responsible professional’s judgment. No specific weight and height criteria were used. Subsequently, patients underwent balanced general anesthesia to proceed with the surgery. The types of surgeries included in the review were as follows: a) general surgery: colorectal, esophagogastric, hepatic, and pancreatic surgery; urological surgery: cystectomy and nephrectomy; thoracic surgery: pulmonary resections such as lobectomies, segmentectomies, and atypical resections.

Objectives: The primary objective was to establish the safety of the technique in terms of the incidence of early and late respiratory depression, defined as bradypnea, with a respiratory rate of fewer than 10 breaths per minute, peripheral oxygen saturation below 90%, and/or signs of drowsiness or deep sedation. The incidence of atelectasis and the need for respiratory support were also analyzed, as well as the possible association of these complications with the presence of respiratory comorbidities, obesity, or smoking habits that may predispose to their development.

Secondary objectives were to record the consumption of rescue intravenous (IV) morphine in the first 24 postoperative hours, the incidence of nausea and vomiting (PONV), and the incidence of late postoperative complications (within 90 days after surgery) such as pneumonia, readmission rates, and reoperation rates. Hospital stays and mortality rates were also recorded.

Statistical Analysis: Data were described using the most appropriate statistics for the nature and scale of each variable: absolute and relative frequencies in percentages, and mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables, or median and interquartile range if data distribution recommended it. To measure the association between categorical variables, the parametric Chi-square test or its non-parametric equivalent, Fisher's exact test, was used when the parametric test was not applicable. For quantitative variables, normality was verified using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and the ANOVA test was used for comparing means for independent samples or its non-parametric equivalent (Kruskall-Wallis) when appropriate. A significance level of 0.05 was established. All analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package (version 29.0.0.0 (241)).

Literature Review: A literature search was conducted in the following databases: UpToDate, Medline, Embase, PubMed, and Tripdatabase. The English terms used in the search were: intrathecal morphine, intrathecal opioids, pain management for minimally invasive surgery, perioperative analgesia for minimally invasive surgery.

Results

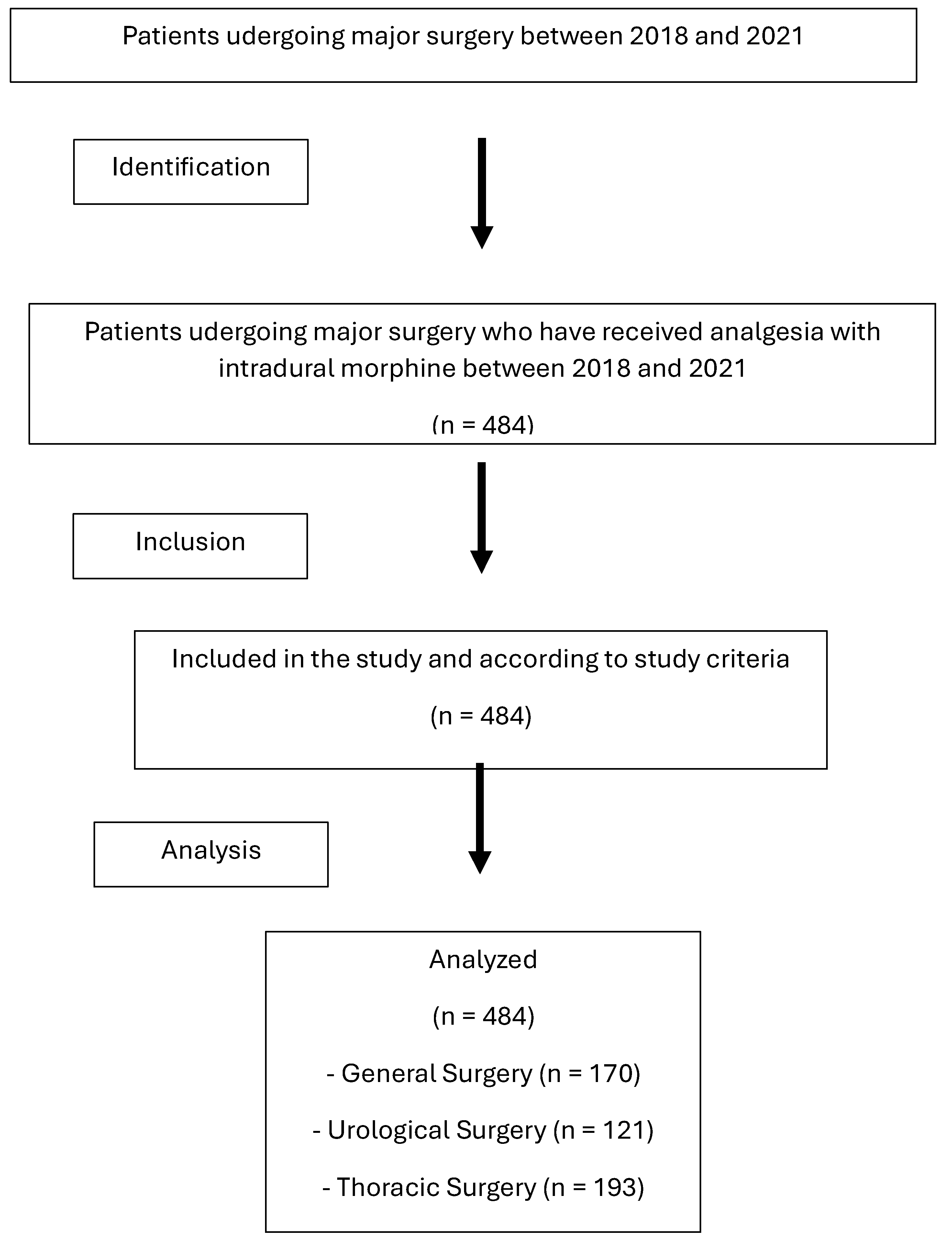

A total of 484 patients who underwent major surgery at Donostia University Hospital between January 2018 and December 2021 received intradural morphine as an analgesic technique (Fig. 1. Flow diagram).

Demographics: The patients had an average age of 65.99 years, mostly male (60.3%), with an average height of 166.75 cm and an average weight of 73.26 kg. 37% of the patients were overweight [body mass index (BMI) 25-30] and up to 20% were obese (BMI ≥ 30) (

Table 1).

Preoperative Data: Preoperative data related to conditions that could increase the risk of respiratory depression and postoperative pulmonary complications were collected. 17.36% of the patients were diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma and were receiving chronic bronchodilator treatment, 5.17% had sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (SAHS), and 1.4% had both conditions. 0.62% of the patients had interstitial lung diseases. There was also a high percentage of smokers (24.6%) and ex-smokers (25%). The data broken down by surgical specialties are shown in

Table 2.

Types of Surgeries: The different types of surgeries reviewed are shown in

Table 3.

Technique and Complications: In the cases reviewed in this study, no adverse incidents were recorded regarding the intradural puncture technique. In all cases, it was successfully performed without dosing errors related to morphine. The intradural morphine dose administered was based on the mentioned criteria, averaging 180.91 micrograms (mcg) (SD 38.039, with a maximum dose of 400 mcg and a minimum of 100 mcg), significantly higher in the thoracic surgery group (p<0.01).

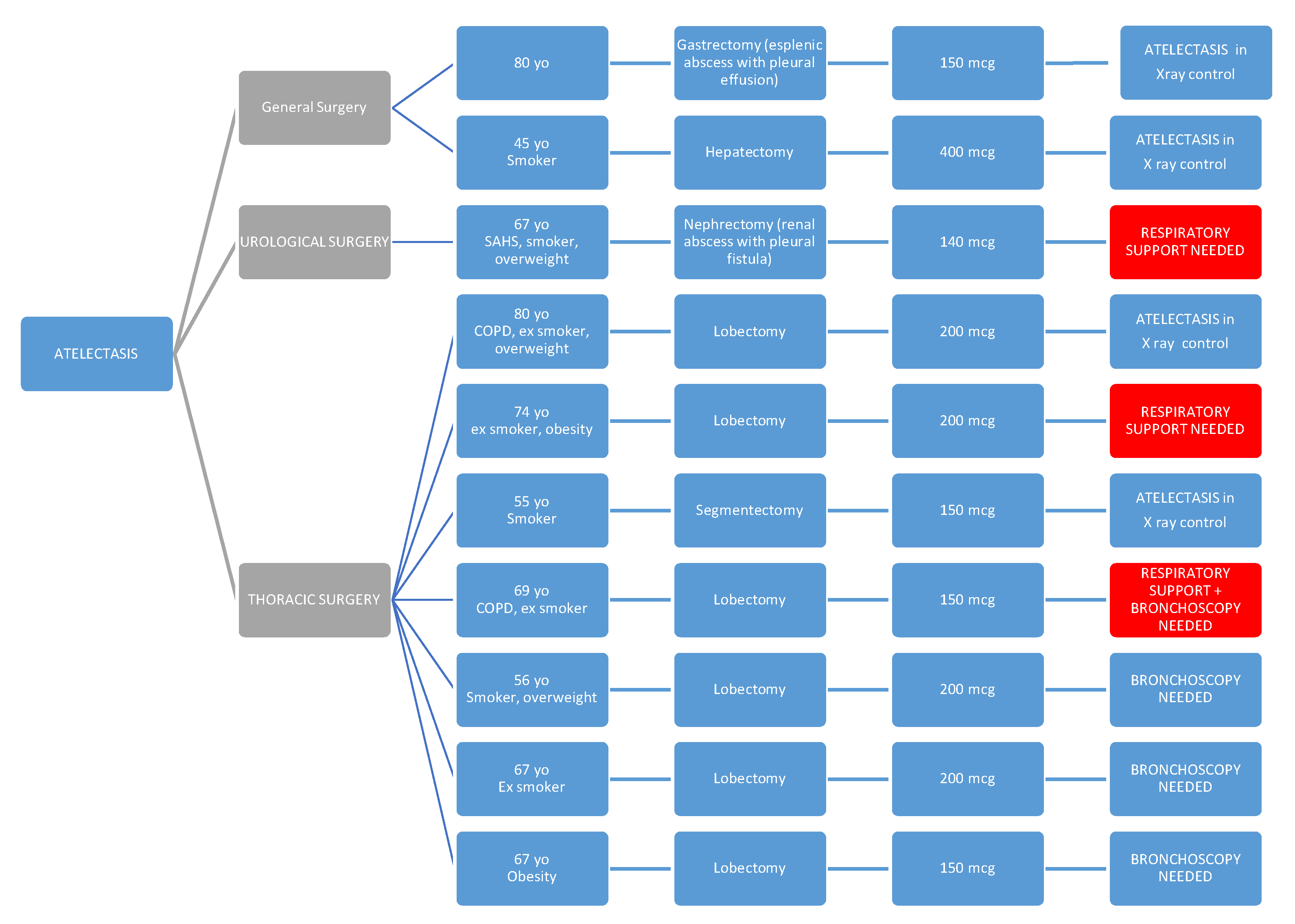

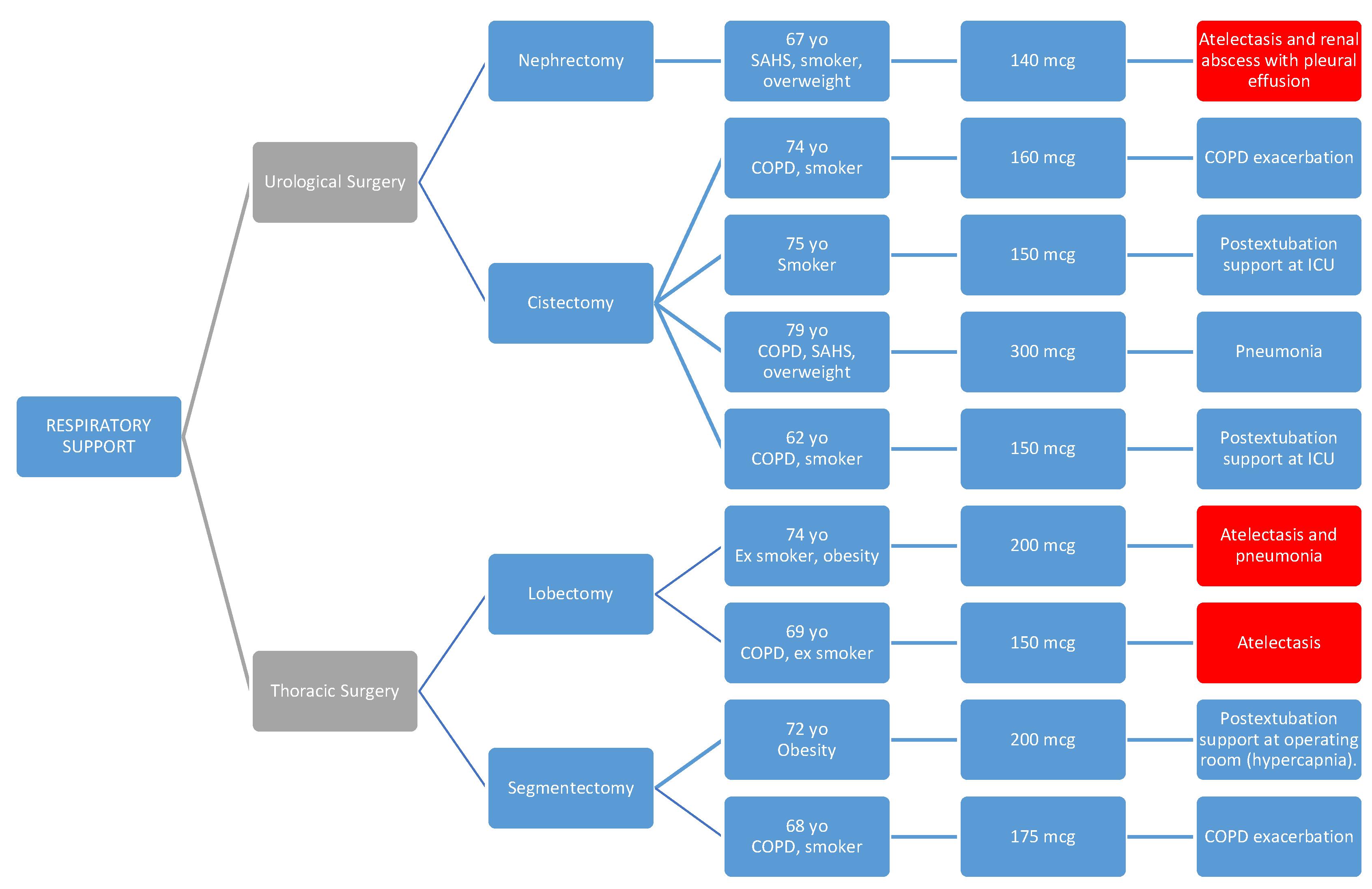

Primary Objectives: No cases of early or late respiratory depression were detected. Regarding respiratory complications, there were ten cases of atelectasis (2.07%) (2 in general surgery, 1 in urological surgery, and 7 in thoracic surgery), with no significant differences between surgical groups (p=0.21). Nine patients (1.86%) required respiratory support (0, 5, and 4 patients respectively in general, urological, and thoracic surgery), with these differences being statistically significant (p=0.02), this need being more frequent in patients undergoing urological or thoracic surgery (

Table 4).

Secondary Objectives: 51.03% (247 patients) required postoperative rescue with intravenous morphine, with an average dose of 6.98 mg (SD 4.984, minimum 1 mg, maximum 30 mg), significantly higher in thoracic surgery patients (p<0.01).

The observed incidence of PONV was 30.37%, with little difference between surgical specialties (32.35%, 28.93%, and 29.53% in general, urological, and thoracic surgery, respectively) (p=0.79). All cases were treated satisfactorily with standard antiemetics (ondansetron and droperidol) at usual doses. Continuing with the description of secondary objectives, the incidence of pneumonia was 3.72% with no differences between surgical groups (p=0.11). The average hospital stay was 9.72 days, longer for patients undergoing urological surgery (16.45 days) and shorter for general surgery (10.42 days) and thoracic surgery (4.88 days), with this difference being statistically significant (p<0.01). The readmission rate was 8.06% (p=0.01) and 4.34% of the patients had to be reoperated (p=0.01), with general surgery patients having the lowest incidence of both complications. Six patients died within 90 days post-surgery (1.24%). Four of them had undergone urological surgery, the specialty with the highest mortality incidence (3.31%) (p=0.03), and two were from the thoracic surgery group (

Table 5).

Discussion

Proper control of acute postoperative pain is one of the fundamental pillars of managing patients undergoing major surgery, both open and minimally invasive. With the progressive development of ERAS protocols in abdominal and thoracic surgery through less invasive procedures, the trend is to adjust our anesthetic practice, including regional techniques for pain control(18).

While the use of techniques such as epidural analgesia has been extensively studied in open surgery (e.g., laparotomy, thoracotomy, cystectomies)(24)(25)(26), there is less evidence on the management of acute postoperative pain in laparoscopic or minimally invasive surgery(27), whose prevalence is increasing compared to open surgery, which has been relegated to complex abdominal surgery as far as our data is concerned (as observed in

Table 3, both hepatobiliary surgery and cystectomy are performed via laparotomy in all cases, while open approach in thoracic surgery, for example, is reserved for complex cases requiring extensive pulmonary resections such as pneumonectomies or the presence of intraoperative complications).

Although there is evidence that the approach to pain in such surgeries should consist of a multimodal strategy, with regional techniques as the cornerstone(13), it remains to be determined which regional technique is preferred in these minimally invasive surgeries (e.g., laparoscopies, videothoracoscopies, robotic surgery). A recent study recommends intrathecal morphine as part of a multimodal analgesic strategy due to its opioid-sparing effect(28)(29)(18).

The role of epidural analgesia is declining due to its delay in ambulation and discharge home. ERAS Society guidelines no longer recommend epidural technique in open hepatic resection analgesia(30). Therefore, in the context of ERAS programs, this technique is being replaced by interfascial regional blocks or surgical site infiltration(4). Regarding intrathecal morphine, there are conflicting results in the literature. While some consider it as inappropriate as epidural analgesia(4), others view it as an effective, simple method with a low complication rate analgesia(31)(28)(32). It has been published that spinal analgesia is the best therapeutic option for postoperative analgesia and opioid reduction in the first 24 hours after colorectal surgery, compared to transverse abdominis plane block (TAP), surgical wound catheter, local anesthetic infiltration into incisions, epidural anesthesia, or IV PCA(29).

Likewise, given the opioid-sparing effect of rescue opioids in the postoperative period with the use of intrathecal morphine, reported by various authors in different types of surgeries(6)(28)(33)(34), it would also perfectly fit within the ERAS protocols, making it ideal for pain management in those patients at higher risk of respiratory depression due to the use of intravenous opioids(35)(22)(36)(30).

In our study, we observed that 51.03% of the patients (247) required intravenous morphine rescue in the postoperative period, with an average dose of 6.98 mg (SD 4.984 mg, minimum 1 mg, maximum 30 mg). We found that morphine requirements were significantly lower in the urological surgery group compared to both the general and thoracic surgery groups.

The analgesic efficacy having already been proven in other studies(13)(14)(15), our aim with this review was to highlight the efficacy of intrathecal morphine in different surgical specialties and also to assess the safety of the technique, especially regarding respiratory depression(5)(37)(38).

We did not observe any cases of early or late respiratory depression, which has also been reported by other authors using low doses of morphine similar to those used in our study(10). It is worth noting that the doses of intrathecal morphine administered were low (an average of 180.91 micrograms), which supports previously published findings that doses below 300 micrograms provide adequate analgesia without causing notable side effects(19)(39). Furthermore, this absence of respiratory depression in our study is particularly noteworthy, given that a significant percentage of the patients studied had medical history of respiratory issues and predisposing conditions to pulmonary complications, which are detailed in

Table 3.

It is worth noting that a large percentage of COPD patients, smokers, and former smokers underwent thoracic surgery (a predictable observation given the association between smoking, COPD, and lung cancer), with this difference being significant compared to urology and general surgery.Principio del formulario

Final del formulario

Thus, based on our results and those of other authors regarding the incidence of respiratory depression(1)(3)(16)(9)(19)(20)(29), it can be concluded that the risk with low doses of intrathecal morphine is not greater than that associated with systemic opioid administration analgesia. Therefore, the need for continuous extended monitoring would be unnecessary(1)(3)(16)(9)(19)(20)(29). Despite a significant difference in intrathecal morphine doses in the thoracic surgery group compared to the other two, this also does not translate into differences regarding the incidence of respiratory depression, as these are still low doses, as previously mentioned.

As above mentioned, we conducted a review of postoperative respiratory complications such as atelectasis and the need for respiratory support, as well as the presence or absence of preoperative predisposing factors that could increase this risk (such as COPD, OSA, other respiratory diseases, obesity, and smoking or former smoking status), and we present our findings in the following diagrams."

In diagram 1, we see the relationship of patients with atelectasis.

Patients who have required respiratory support are highlighted in red, and for this reason, they will also appear in the diagram shown below.

We want to emphasize that the observation of a higher rate of atelectasis (without this difference being statistically significant) among patients undergoing thoracic surgery may be explained both by the surgery itself and by the fact that in our center, a chest X-ray is routinely performed on all patients undergoing major lung resection, which is not done in other specialties. Therefore, in most cases, it may be an incidental finding, as few cases required bronchoscopy or respiratory support.

In diagram 2, we provide a more detailed reflection of the characteristics of patients who required respiratory support (significantly higher in urological and thoracic surgery).

Diagram 2.

Patients who are already shown in the previous diagram are highlighted in red again due to the presence of atelectasis being the reason for requiring respiratory support. * PACU: post-anesthesia care unit.

Diagram 2.

Patients who are already shown in the previous diagram are highlighted in red again due to the presence of atelectasis being the reason for requiring respiratory support. * PACU: post-anesthesia care unit.

In all cases, the respiratory issue was detected early and improved with the applied treatment, without requiring reintubation in any of the cases.

As seen in the diagrams, all of them presented one or more of the predisposing preoperative factors such as respiratory pathology (COPD, SAHS), obesity, or smoking habits(40)(41).

In 4 cases, high-flow oxygen therapy (HFOT) or non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) was used as a transition after orotracheal extubation, and this support could be withdrawn within a few hours.

Regarding the observed postoperative NVPO rate of 30.37%, it is also in line with what has been published in other series, which may partly be associated with the use of intradural morphine(9). In our experience, this complication was solved in all cases with standard antiemetics (ondansetron and droperidol), although it may be advisable in the future to better tailor the NVPO prevention protocol.

No differences were observed between specialties (p=0.79) (32.35% in general surgery; 28.39% in urological surgery; and 29.53% in thoracic surgery). Nor were differences observed between subspecialties.

Regarding the incidence of postoperative pneumonia, no significant differences were found between specialties.

The incidence of readmissions and reinterventions was significantly higher in patients undergoing urological surgery (where mortality was significantly higher) and thoracic surgery compared to those undergoing general surgery. However, hospital stay was longer in the urology and general surgery groups.

The surgical intervention with the highest complication rate was cystectomy, which in our center is performed via open approach (laparotomy) in all cases (during the reviewed period). Out of 95 patients undergoing this procedure, 25 experienced complications, most of them urinary tract infections, with 5 cases requiring readmission to Critical Care Units due to the severity of the pathology. 10 patients required urgent reintervention. 11 patients were readmitted after discharge, and 4 died within 90 days after the intervention. None of the cases involved respiratory complications, but rather complications derived from the surgical technique or the patient's underlying pathology. This rate does not differ from that described by other authors for this type of surgery(42).

Out of the patients undergoing lung lobectomies, 32 experienced complications, mostly due to persistent air leaks (11 patients) with consequent emphysema and pneumothorax, rates that do not differ from the literature(43). Out of these 11 patients, 7 needed surgical reintervention, and 2 required readmission to Critical Care Units.

Therefore, in patients who are candidates to receive intrathecal morphine as an analgesic technique, it is crucial to carry out a thorough preoperative assessment defining comorbidities and anticipating possible complications. Additionally, careful intraoperative management along with meticulous postoperative monitoring allows for proper recovery, minimizing the occurrence of complications, and enabling early detection in case they occur.

Study Limitations: This is an observational, single-center, retrospective study of a large sample of patients; among the limitations, it´s a retrospective study with data collection afterward stands out, which may imply information loss; furthermore, it would be interesting to compare this analgesic technique with intrathecal morphine with other analgesic techniques applicable to the ERAS program; therefore, it might be advisable to conduct a randomized, prospective, multicenter clinical trial in the future to obtain definitive conclusions on the safety and efficacy of intradural morphine administration in major surgery.

Conclusions

The administration of intrathecal morphine, at low doses as used in this study, for the relief of acute postoperative pain in major surgery including general and digestive surgery, urology, and thoracic surgery, can be considered a simple, safe, and reliable analgesic technique that would fit perfectly as part of the multimodal analgesic strategy in ERAS protocols for a variety of surgical procedures. With an evidence of more than 40 years with low-dose ITM, we can conclude that the risk of respiratory depression is not higher than with systemic opioids, and therefore, patients could continue their postoperative recovery in hospital rooms without the need for continuous monitoring for an extended period, which could be modified, after evaluation of its clinical safety in a clinical trial, in the guidelines of the most important societies such as ESAIC, ASA, EACTAIC, ESRA and ASRA.

References

- Feldheiser A, Aziz O, Baldini G, Cox BPBW, Fearon KCH, Feldman LS, et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) for gastrointestinal surgery, part 2: consensus statement for anaesthesia practice. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2016 Mar;60(3):289–334.

- Garutti I, Cabañero A, Vicente R, Sánchez D, Granell M, Fraile CA, et al. Recomendaciones de la Sociedad Española de Cirugía Torácica y de la Sección de Cardiotorácica y Cirugía Vascular de la Sociedad Española de Anestesiología, Reanimación y Terapéutica del Dolor, para los pacientes sometidos a cirugía pulmonar incluidos en un programa de recuperación intensificada. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2022 Apr 1;69(4):208–41.

- Lavand’homme PM, Kehlet H, Rawal N, Joshi GP, PROSPECT Working Group of the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy (ESRA). Pain management after total knee arthroplasty: PROcedure SPEcific Postoperative Pain ManagemenT recommendations. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2022 Sep 1;39(9):743–57.

- Joshi GP, Kehlet H. Postoperative pain management in the era of ERAS: An overview. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2019 Sep 1;33(3):259–67.

- DeSousa, KA. Intrathecal morphine for postoperative analgesia: Current trends. World J Anesthesiol. 2014;3(3):191.

- Meylan N, Elia N, Lysakowski C, Tramèr MR. Benefit and risk of intrathecal morphine without local anaesthetic in patients undergoing major surgery: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2009 Feb;102(2):156–67.

- Rawal, N. Current issues in postoperative pain management. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2016 Mar;33(3):160–71.

- Rawal, N. Epidural analgesia for postoperative pain: Improving outcomes or adding risks? Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2021 ;35(1):53–65. 1 May.

- Gonvers E, El-Boghdadly K, Grape S, Albrecht E. Efficacy and safety of intrathecal morphine for analgesia after lower joint arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis with meta-regression and trial sequential analysis. Anaesthesia. 2021 Dec;76(12):1648–58.

- Roofthooft E, Joshi GP, Rawal N, Van de Velde M, the PROSPECT Working Group* of the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy and supported by the Obstetric Anaesthetists’ Association. PROSPECT guideline for elective caesarean section: updated systematic review and procedure-specific postoperative pain management recommendations. Anaesthesia. 2021;76(5):665–80.

- Anger M, Valovska T, Beloeil H, Lirk P, Joshi GP, Van de Velde M, et al. PROSPECT guideline for total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and procedure-specific postoperative pain management recommendations. Anaesthesia. 2021 Aug;76(8):1082–97.

- Albrecht E, Chin KJ. Advances in regional anaesthesia and acute pain management: a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020 Jan;75 Suppl 1:e101–10.

- Feray S, Lubach J, Joshi GP, Bonnet F, Van de Velde M, the PROSPECT Working Group *of the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy. PROSPECT guidelines for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a systematic review and procedure-specific postoperative pain management recommendations. Anaesthesia. 2022;77(3):311–25.

- Hamilton C, Alfille P, Mountjoy J, Bao X. Regional anesthesia and acute perioperative pain management in thoracic surgery: a narrative review. J Thorac Dis. 2022 Jun;14(6):2276–96.

- Parra MF, Miranda LC, Sepulveda JO, Mocarquer BV, Campos FJ, Fernandez YM. Recuperación mejorada después de cirugía torácica. ERAS. Rev Cir [Internet]. 2019 Jul 11 [cited 2022 Dec 4];71(4). Available from: https://www.revistacirugia.cl/index.

- Chin KJ, McDonnell JG, Carvalho B, Sharkey A, Pawa A, Gadsden J. Essentials of Our Current Understanding: Abdominal Wall Blocks. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42(2):133–83.

- Marciniak D, Kelava M, Hargrave J. Fascial plane blocks in thoracic surgery: a new era or plain painful? Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2020 Feb;33(1):1–9.

- Rawal, N. Intrathecal opioids for the management of post-operative pain. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2023 Jun 1;37(2):123–32.

- Rathmell JP, Lair TR, Nauman B. The role of intrathecal drugs in the treatment of acute pain. Anesth Analg. 2005 Nov;101(5 Suppl):S30-43.

- Mugabure Bujedo, B. A clinical approach to neuraxial morphine for the treatment of postoperative pain. Pain Res Treat. 2012;2012:612145.

- Gehling M, Tryba M. Risks and side-effects of intrathecal morphine combined with spinal anaesthesia: a meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(6):643–51.

- Pirie K, Traer E, Finniss D, Myles PS, Riedel B. Current approaches to acute postoperative pain management after major abdominal surgery: a narrative review and future directions. Br J Anaesth. 2022 Sep;129(3):378–93.

- Sultan P, Gutierrez MC, Carvalho B. Neuraxial Morphine and Respiratory Depression: Finding the Right Balance. Drugs. 2011 Oct;71(14):1807–19.

- Yeung JHY, Gates S, Naidu BV, Wilson MJA, Gao Smith F. Paravertebral block versus thoracic epidural for patients undergoing thoracotomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Feb 21;2:CD009121.

- Patel J, Jones CN. Anaesthesia for Major Urological Surgery. Anesthesiol Clin. 2022 Mar;40(1):175–97.

- Moraca RJ, Sheldon DG, Thirlby RC. The Role of Epidural Anesthesia and Analgesia in Surgical Practice. Ann Surg. 2003 Nov;238(5):663–73.

- Levy BF, Tilney HS, Dowson HMP, Rockall TA. A systematic review of postoperative analgesia following laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis Off J Assoc Coloproctology G B Irel. 2010 Jan;12(1):5–15.

- Vijitpavan A, Kittikunakorn N, Komonhirun R. Comparison between intrathecal morphine and intravenous patient control analgesia for pain control after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: A pilot randomized controlled study. Koning MV, editor. PLOS ONE. 2022 Apr 6;17(4):e0266324.

- Xu W, Varghese C, Bissett IP, O’Grady G, Wells CI. Network meta-analysis of local and regional analgesia following colorectal resection. BJS Br J Surg. 2020;107(2):e109–22.

- Melloul E, Hübner M, Scott M, Snowden C, Prentis J, Dejong CHC, et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Liver Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations. World J Surg. 2016 Oct;40(10):2425–40.

- Kong SK, Onsiong SMK, Chiu WKY, Li MKW. Use of intrathecal morphine for postoperative pain relief after elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Anaesthesia. 2002 Dec;57(12):1168–73.

- Colibaseanu DT, Osagiede O, Merchea A, Ball CT, Bojaxhi E, Panchamia JK, et al. Randomized clinical trial of liposomal bupivacaine transverse abdominis plane block versus intrathecal analgesia in colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2019 May;106(6):692–9.

- Beaussier M, Weickmans H, Parc Y, Delpierre E, Camus Y, Funck-Brentano C, et al. Postoperative analgesia and recovery course after major colorectal surgery in elderly patients: a randomized comparison between intrathecal morphine and intravenous PCA morphine. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006 Dec;31(6):531–8.

- Andrieu G, Roth B, Ousmane L, Castaner M, Petillot P, Vallet B, et al. The efficacy of intrathecal morphine with or without clonidine for postoperative analgesia after radical prostatectomy. Anesth Analg. 2009 Jun;108(6):1954–7.

- Tang J, Churilov L, Tan CO, Hu R, Pearce B, Cosic L, et al. Intrathecal morphine is associated with reduction in postoperative opioid requirements and improvement in postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing open liver resection. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020 Aug 19;20(1):207.

- El-Boghdadly K, Jack JM, Heaney A, Black ND, Englesakis MF, Kehlet H, et al. Role of regional anesthesia and analgesia in enhanced recovery after colorectal surgery: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022 May;47(5):282–92.

- Giovannelli M, Bedforth N, Aitkenhead A. Survey of intrathecal opioid usage in the UK. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008 Feb;25(2):118–22.

- Koning MV, de Vlieger R, Teunissen AJW, Gan M, Ruijgrok EJ, de Graaff JC, et al. The effect of intrathecal bupivacaine/morphine on quality of recovery in robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: a randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia. 2020 May;75(5):599–608.

- Cohen, E. Intrathecal Morphine: The Forgotten Child. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2013 Jun;27(3):413–6.

- Admass BA, Ego BY, Tawye HY, Ahmed SA. Post-operative pulmonary complications after thoracic and upper abdominal procedures at referral hospitals in Amhara region, Ethiopia: a multi-center study. Front Surg [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 8];10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsurg.2023. 1177.

- Allou N, Bronchard R, Guglielminotti J, Dilly MP, Provenchere S, Lucet JC, et al. Risk Factors for Postoperative Pneumonia After Cardiac Surgery and Development of a Preoperative Risk Score*. Crit Care Med. 2014 May;42(5):1150.

- Zakaria AS, Santos F, Dragomir A, Tanguay S, Kassouf W, Aprikian AG. Postoperative mortality and complications after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer in Quebec: A population-based analysis during the years 2000–2009. Can Urol Assoc J. 2014;8(7–8):259–67.

- Petrella F, Spaggiari L. Prolonged air leak after pulmonary lobectomy. J Thorac Dis. 2019 Sep;11(Suppl 15):S1976–8.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).