1. Introduction

Competition is a significant stressor in sports (

Adi et al., 2024). Stressors trigger the release of stress hormones, such as cortisol, increasing the metabolic rate, dilating blood vessels, and elevating heart rate (

Chu et al., 2024;

Dalmeida & Masala, 2021;

Russell & Lightman, 2019) The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) regulates this heightened state and its activity can be measured via Heart Rate Variability (HRV;

Dalmeida & Masala, 2021;

Salai et al., 2016). Fluctuations in peak-to-peak heart-rate intervals (RR intervals) indicate the ability of the ANS to adjust to stressors, reflecting better health and. HRV has been associated with executive functioning as well (

Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). HRV signals can be analyzed in different ways. Time-domain analysis approaches are considered reliable procedures for short-term HRV-indicated stress assessment, even for short periods as short as two to five minutes (

Pereira et al., 2017). Root Mean Square of Successive Differences (RMSSD) and Standard Deviation of Normal-to-Normal intervals (SDNN) are the most frequently reported time-domain HRV metrics and tend to decrease under stress (

Immanuel et al., 2023;

Machetanz et al., 2021). On the other hand, frequency-domain HRV metrics, such as Low Frequency/High Frequency (LF/HF) ratio, also reflect ANS modulation in relatively longer recordings and are expected to increase during stress (

Dalmeida & Masala, 2021). However, its interpretation as a measure of ANS balance is still debated (

Hinde et al., 2021).

To reveal stress levels before competition,

Blásquez et al. (

2009) examined swimmers at pre-competition and pre-training stages. HRV metrics, such as RMSSD and LF/HF ratio, indicated significantly greater stress before competition compared to training. HRV results were consistent with the Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 (CSAI-2;

Martens et al., 1983) subscales, cognitive anxiety, somatic anxiety, and self-confidence. Similarly,

Souza et al. (

2019) found that the LF/HF ratio and somatic anxiety scores were significantly higher during competition across athletes from three different disciplines: canoeists, street runners, and jiu-jitsu fighters. These studies highlight typical findings of increased stress and anxiety before competition. Furthermore, excessive competitive stress not only impairs mental well-being but is also associated with a heightened risk of injury and decreased athletic output (

Adi et al., 2024;

Martens et al., 1990;

Patel et al., 2010). Taken together, findings emphasize the need for interventions to manage stress and anxiety before competition to perform at an individual’s best.

Elevated arousal, accompanied by anxiety, does not necessarily lead to catastrophic outcomes. According to the Multidimensional Anxiety Theory (

Martens et al., 1990), anxiety consists of multiple components with distinct effects on performance. Specifically, cognitive anxiety (e.g., negative thoughts, worries about performance) has a negative linear relationship with performance, while somatic anxiety (e.g., sweating, increased heart rate) follows an inverted-U-shaped relationship, suggesting that moderate arousal can facilitate performance. In contrast, self-confidence is proposed to have a positive linear association with performance. Therefore, in this study, a team hypnosis intervention was designed to improve psychophysiological regulation, pre-competition readiness, and physical performance in a youth team.

Hypnosis is a specific state of consciousness distinguished by highly focused attention and heightened responsiveness to suggestions (

Elkins et al., 2015). Its efficacy in performance enhancement has been demonstrated in various athletic settings. For example, basketball players, who received repeated individual and group hypnosis sessions, scored more after the onset of the intervention during an actual game season (

Schreiber, 1991). Expanding its use,

Hasyim et al. (

2023) associated a single hypnosis session with improvements in essential skills in volleyball, such as lower-pass, upper-pass, and service techniques. However, the study was limited in terms of ecological validity due to a lack of real-world assessment. Additionally, hypnosis has been linked to an increase in physical power (

Nieft et al., 2024). A single hypnosis session, designed to enhance physical power through a post-hypnotic anchor, increased handgrip strength one week after the intervention, although the effect was not immediate. The lack of an instantaneous effect may be due to the relaxing nature of hypnosis, which highlights the need for long-term examination of the intervention outcomes.

More recently,

Hoffmann et al. (

2024) have expanded the application of hypnosis to downhill mountain biking, aimed at improving pre-competition readiness and performance. After an audio-hypnosis intervention, elite downhill mountain bikers expressed significantly reduced race-related somatic anxiety and increased self-confidence. It also led to a significant decrease in the LF/HF ratio, indicating elevated vagal activity and boosted stress resilience. Contrary to the HRV outcomes, athletic performance did not show any improvement after the intervention. However, the baseline performance of the study participants was already significantly higher compared to the rest of the competitors. Notably, the study proved the feasibility of audio-based hypnosis intervention (

Hoffmann et al., 2024). Overall, this study suggests that hypnosis can strengthen pre-competition emotional regulation.

Despite this progress, several notable gaps remain. There is a lack of research during real competitions (

Li & Li, 2022;

Adi et al., 2024), and a few studies employ repeated-measures designs, which are essential for capturing dynamic changes in psychological states (

de Melo et al., 2022;

Lochbaum et al., 2022). The present study evaluates the effects of a tailored team hypnosis intervention on handball players' psychophysiological stress markers, psychological state before competition, and performance outcomes across the entire competitive season in a competitive team ball game. Based on prior evidence, we hypothesized:

1.The hypnosis intervention will improve HRV markers (RMSSD and SDNN) before competition, indicating greater parasympathetic activity and stress resilience.

2.The intervention will improve physical performance, measured by handgrip strength and total scores per game.

3.The intervention will increase self-confidence and reduce cognitive and somatic anxiety before competition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

To determine the required sample size, we conducted a power analysis (G*Power;

Faul et al., 2007), based on the previous studies by Dr. Barbara Schmidt (

Hoffmann et al., 2024; Schmidt et al., 2024a; Schmidt et al., 2024b). Assuming a medium to large expected effect size (

d = 0.7) with α = 0.05 and power = 0.95, the analysis indicated a sample size of 24 participants. The participants were female athletes from the Bad Schwartau girls' handball club in Germany, competing in either the National Youth League A (n = 12) or League B (n = 16). Study participation was voluntary. All team members, except two, participated in the study. A subset of athletes (n = 2) participated in both leagues. Of all participants, two joined the data collection only once. Considering the study design, their data were excluded from statistical analysis to achieve the within-person comparison. Since they were underage, all participants’ parents provided written informed consent before the data collection. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Jena University Hospital (protocol code: 2024-3579-BO-A; date of approval: 14.11.2024) and preregistered at the German Clinical Trials (project ID: DRKS00035735).

2.2. Experimental Design and Procedure

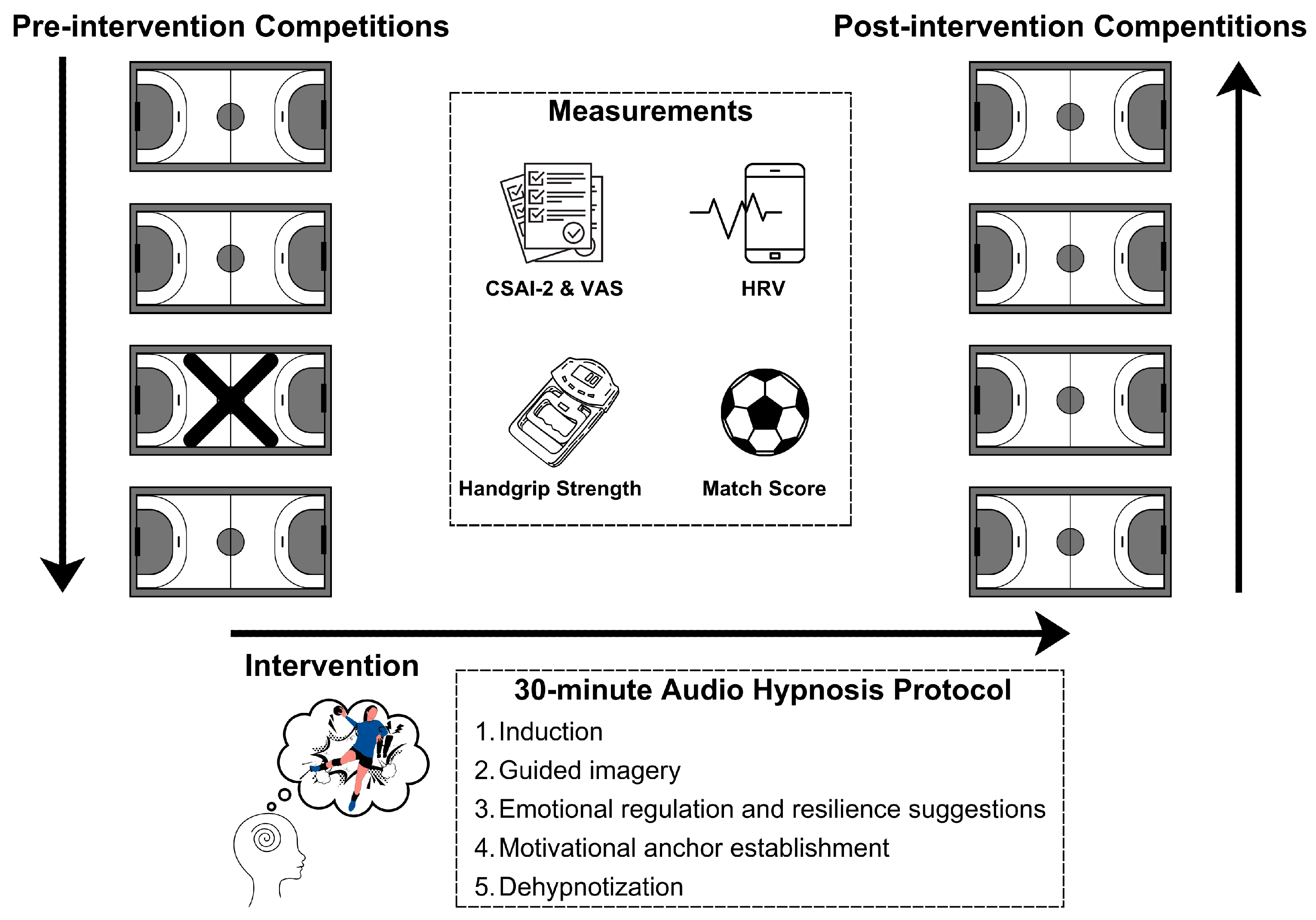

We employed a quasi-experimental pre-post design, with data collected during eight official league matches (see

Figure 1). These were divided equally between pre-intervention and post-intervention conditions (League A: one pre- and two post-intervention games; League B: two pre- and two post-intervention games). Seven of the matches were home games, and one was an away game. Measurements were consistently conducted at all home games except the first one. At home games, all data were collected in the same room during each home game to ensure consistency of conditions. The hypnosis intervention was introduced after four matches (three home and one away), and post-data from four home games were collected during the post-intervention phase.

Since it was not possible to collect more away-game data, the single away game was excluded from analysis due to significant procedural inconsistencies. At home games, data collection was the first structured activity upon player arrival at the sports facility in the morning. Also, measurements were conducted in a private training room, where all participants could sit comfortably. After the measurement, the players had enough time to complete their usual pre-game routines, such as taking a group walk, singing together, and warming up. In contrast, the away game began after a group travel by team bus. Upon arrival, questionnaire data and HRV were collected on the team's bus. Then, the pre-game handgrip strength and mid- and end-game questionnaires were administered in the locker room, which lacked the controlled testing environment available at home. Since only one away game was scheduled after the intervention, repeated measures could not be obtained. Given the differences in environment, measurement timing, and data quality, the away game data were excluded from statistical analysis.

Pre-game assessments began two and a half hours before the kickoff and lasted around 30 minutes in total. The sequence started with participants wearing chest strap heart-rate monitors. During the initial signal stabilization period, participants completed the pre-game self-report questionnaires, which were followed by one minute of seated rest. Then, a 5-minute recording was taken while participants were sitting calmly with open eyes. After the HRV recording, handgrip testing was applied one by one in a standard seated position.

At half-time and immediately after the game, athletes completed the mid- and end-game ratings altogether in the same locker room, which took approximately one minute in total. Feedback questions were later added to the end-game questionnaires after the intervention.

To introduce the intervention, athletes were given simultaneous online access to a 30-minute audio hypnosis session and instructed to listen to it at least once in a quiet and calm setting. That said, they were also free to repeat the session according to personal preference.

2.3. Intervention

Dr. Barbara Schmidt developed the specific hypnotic suggestions in collaboration with the women's handball team in Bad Schwartau to ensure they were tailored to the athletes' needs. She recorded a 30-minute audio session that the players were instructed to listen to individually in a quiet and undisturbed environment. The hypnosis induction followed the standardized procedure outlined in the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale (SHSS;

Weitzenhoffer & Hilgard, 1962), beginning with eye fixation, progressive relaxation, and eye closure, followed by deepening through slow breathing and a countdown from 1 to 10.

The core of the intervention consisted of sport-specific imagery and suggestions. The mental journey began in the locker room—a designated safe space—where players were guided to recharge mentally and physically. Upon putting on their jerseys, they were encouraged to visualize themselves accessing a sense of collective strength and "superpower," preparing to enter the game in an energized and focused state. The script included scenarios both on the field and on the bench, emphasizing situational awareness, automatic decision-making, and heightened concentration, described metaphorically as entering a time-lapse state with predictive clarity.

To support emotional regulation and resilience, the intervention incorporated strategies for dealing with setbacks, such as learning from mistakes and releasing them mentally. Players were also guided to imagine a protective shield that blocked external negativity and to view opponents as sources of inspiration and challenge. As an additional motivational anchor, the intervention included the use of a symbolic "Super Mario star," previously shown to enhance handgrip strength (

Nieft et al., 2024), which players could mentally activate to boost perceived energy and invincibility. The session concluded with a standardized dehypnotization procedure, including counting backwards from 10 to 1, and the suggestion of waking refreshed and energized, akin to the feeling after restful sleep.

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Objective Measures

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) was recorded using the Polar H10 chest straps (

Speer et al., 2020). Before each session, the chest straps were moistened with a damp cloth to ensure signal quality. Then, the devices were connected via Bluetooth to a Samsung smartphone (Model: S22), using the Polar Sensor Logger application (developed by Jukka Happonen, available via Google Play Store). This method enabled us to directly record RR intervals rather than raw heartbeat data. After system synchronization, participants underwent a one-minute resting phase, followed by a five-minute HRV recording with their eyes open, natural breathing, and minimal movement. As recommended by previous research for short-term recordings (

Hinde et al., 2021;

Laborde et al., 2018), the HRV parameters included RMSSD and SDNN. Artifact tolerance was set to a 20% threshold for preprocessing.

Immediately after HRV data collection, handgrip strength was measured using a hand dynamometer with an adjustable handle. One by one, participants remained seated with their arms positioned at their side, elbow bent at 90 degrees, and wrist held in a neutral position, as per standardized strength testing protocols (

Nieft et al., 2024). The correct posture and grip technique were demonstrated before testing. Grip strength was measured using the participant's dominant hand. Each athlete was instructed to squeeze the dynamometer as hard as possible for five seconds, and this procedure was repeated three times with 15-second rest intervals between trials. The results were recorded in kilograms.

Considering the availability of the individual data, the game performance metric included only the total goal count per game. Data were retrieved from the online database of the German Handball Federation (2025), which provides publicly accessible performance data for German handball league games.

2.4.2. Subjective Measures

Demographic and background information were collected through self-report questionnaires at the first game. Participants reported their age, the total number of years in handball, their weekly training hours, and the approximate number of games they played per year. They also indicated their current league participation and the highest league in which they had ever competed. Additionally, athletes provided information about their prior experience with mental training programs and any previous exposure to hypnosis-based techniques.

The CSAI-2 (

Cox et al., 2003) was administered before HRV and handgrip measurements to measure subjective cognitive anxiety, somatic anxiety, and self-confidence before competition. Alongside the CSAI-2, we gathered information on medication and caffeine use.

In addition to the pre-game measurements, perceived stress, performance satisfaction, and confidence were assessed using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) once at half-time and again immediately after the game. For half-time, athletes rated their momentary stress levels, satisfaction with performance, and confidence for the second half. For post-game assessments, they rated their current stress level, overall performance satisfaction, and overall confidence.

Following each post-intervention match, participants were asked to complete a brief feedback form to evaluate their experience with the hypnosis audio. They reported how many times they listened to the recording. Additionally, they rated, on a 5-point Likert scale, whether they believed it had a positive impact on their game performance, how well they were able to engage with the hypnosis, and whether it made them feel more confident before the game. In addition to scaled responses, athletes were invited to provide open-ended feedback about their experience with the intervention and the study procedure.

2.5. Data Analysis

All HRV data were processed using MATLAB (

The MathWorks, Inc., 2024) with the HRVTool toolbox (

Vollmer, 2019). HRV results were merged with the questionnaire data, and the resulting dataset was exported to RStudio for further analysis (Version 2024.09.1+394;

RStudio Team, 2024). Before the statistical modeling, all outcome variables were examined for normality and model assumptions. Consequently, Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMMs) were employed for all analyses (‘gamm’ function from ‘mgcv’ package; Wood, 2023), using a Gamma distribution with a log-link function (

Wood, 2017). The models were constructed to evaluate the effects of the intervention (pre vs. post) while accounting for repeated measures within subjects. A random intercept for each participant was included to model random effects.

To evaluate the statistical significance of the intervention effect, we conducted likelihood ratio tests using ANOVA to compare full and null models, as well as full models with and without covariates. Model fit was assessed using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and residual diagnostics. The significance level for all statistical tests was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Players of the two leagues differed in several demographic variables. Participants in League A were older (Mdn = 17.0, MAD = 0.0) than those in League B (Mdn = 15.0, MAD = 0.0), and players in League A reported more years of handball experience (Mdn = 11.0, MAD = 3.0) compared to League B players (Mdn = 9.0, MAD = 1.5). Contrary to the group differences, both groups reported similar weekly training hours (League A: M = 9.96, SD = 1.74; League B: M = 10.29, SD = 1.12) and played a similar number of games annually (League A: Mdn = 50.0, MAD = 7.4; League B: Mdn = 46.0, MAD = 8.9).

Lastly, concerning prior experience with psychological skills training, only one participant from League A reported experience with both hypnosis and mental training. All participants reported experience with mental training. While some participants had other personal experiences, all team members reported experience of a team mental training session to improve their game. None of the demographics, including league, medication, and caffeine use, moderated the outcomes.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics, medication, and caffeine use.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics, medication, and caffeine use.

| Variable |

League A (n = 12) |

League B (n = 16) |

p-value3

|

| Age1

|

17.0 (0.0) |

15.0 (0.0) |

<0.001*** |

| Years of experience1

|

11.0(3.0) |

9.0 (1.5) |

0.767 |

| Number of games per year1

|

50.0 (7.4) |

46.0 (8.9) |

0.167 |

| Training hours per week1

|

9.5 (0.7) |

10.0 (1.1) |

0.057 |

| Medication use2

|

6 (38%) |

9 (56%) |

- |

| Caffeine use2

|

3 (19%) |

2 (12%) |

- |

3.2. Model Comparisons

To examine whether the intervention significantly improved each outcome, we conducted likelihood ratio tests (LRTs) comparing GAMMs with and without the intervention term. Model fit improved significantly for RMSSD (χ²(1) = 11.24, p < .001) and SDNN (χ²(1) = 11.40, p < .001). However, no significant effects of the intervention were found for handgrip strength (χ²(1) = 2.60, p = .107) or goal performance (χ²(1) = –0.39, p = .530).

Regarding subjective psychological measures, significant model improvements were observed for all subscales of the CSAI-2: self-confidence (χ²(1) = 8.62, p < .001), somatic anxiety (χ²(1) = 10.16, p < .001), and cognitive anxiety (χ²(1) = 9.28, p < .001). In contrast, none of the VAS measures showed significant model improvement (see Appendix A.1 for all model diagnostics).

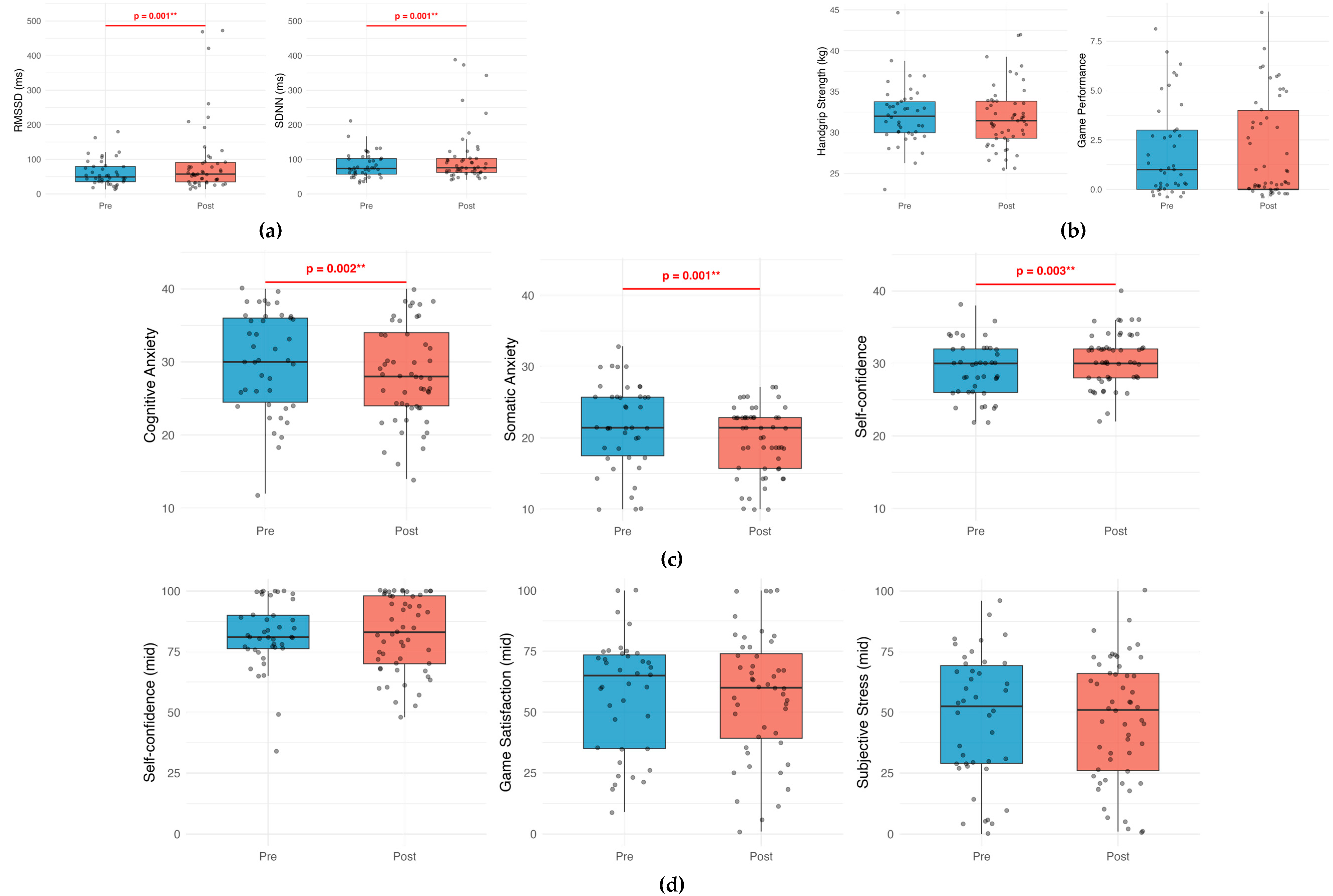

3.3. Primary Outcomes

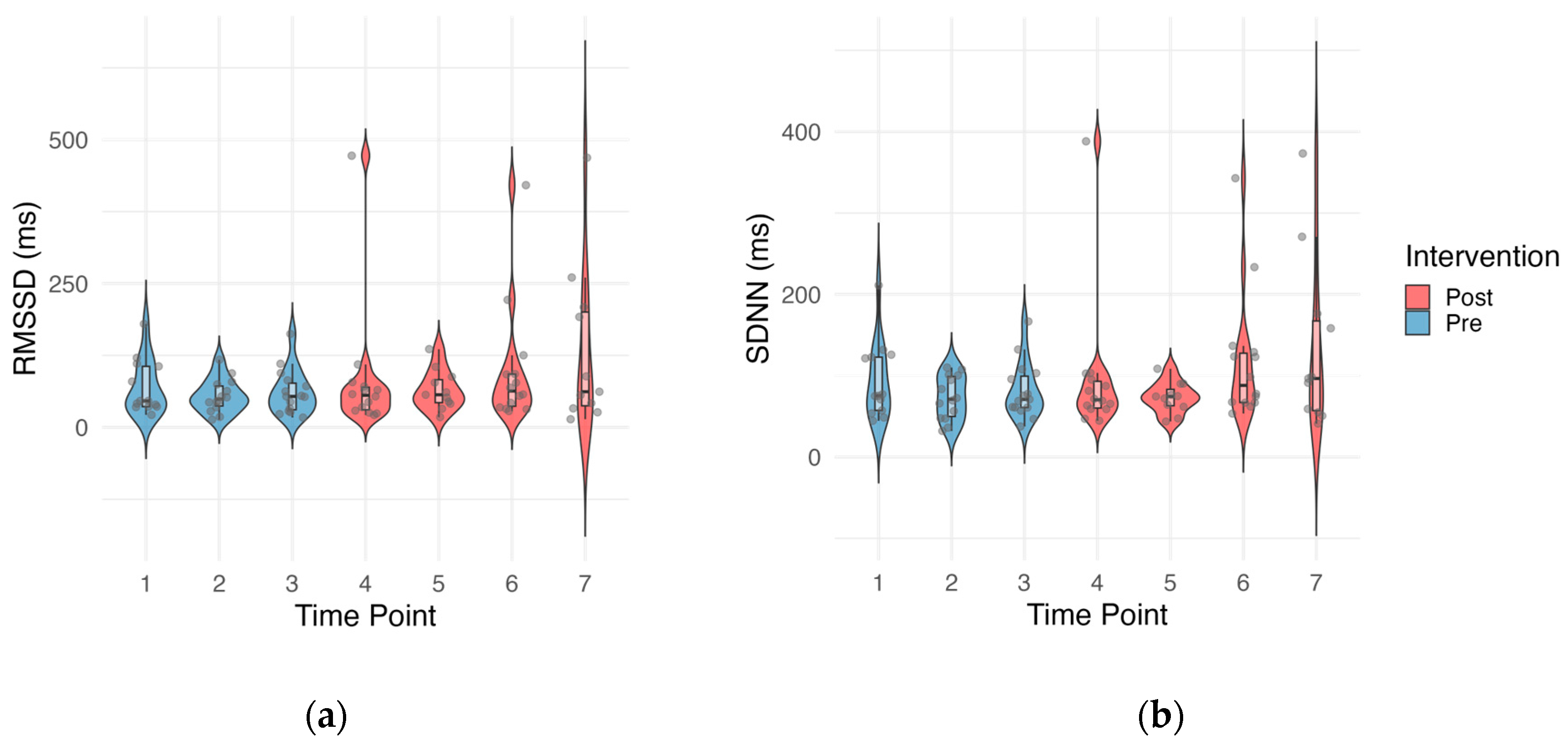

We observed a statistically significant effect of the intervention on all HRV metrics and CSAI-2 subscales. The cumulative results of all measures at pre- and post-intervention are presented in

Figure 2.

3.3.1. Objective Measures

A visual summary of the changes in HRV metrics is presented in

Figure 3. We observed significant improvements in both metrics, RMSSD and SDNN.

Regarding RMSSD, the fixed effect for intervention was positive and statistically significant (b = 0.29, SE = 0.12, t(63) = 2.31, p = .024, adjusted R² = 0.0193). Random effects revealed moderate between-subject variability (intercept SD = 0.54) and moderate within-subject variability (residual SD = 0.0.578).

For SDNN, the fixed effect for intervention was positive and statistically significant (b = 0.20, SE = 0.09, t(63) = 2.27, p = .027, adjusted R² = 0.0183). Random effects showed moderate between-subject variability (intercept SD = 0.339) and moderate within-subject variability (residual SD = 0.418).

No effect was found on physical performance. Handgrip performance analysis revealed that the intervention effect was not statistically significant (b = –0.020, SE = 0.012, t(66) = –1.64, p = .107, adjusted R² = –0.0123). The random effects analysis suggested small between-subject differences in baseline grip strength (intercept SD = 0.097), and small within-subject variation across competitions (residual SD = 0.057).

Game performance analysis showed that the intervention had no significant effect (b = 0.31, SE = 0.23, t(66) = 1.33, p = .188, adjusted R² = –0.0131). Both between-subject variability (intercept SD = 1.70) and within-subject variability (residual SD = 1.08) were relatively high.

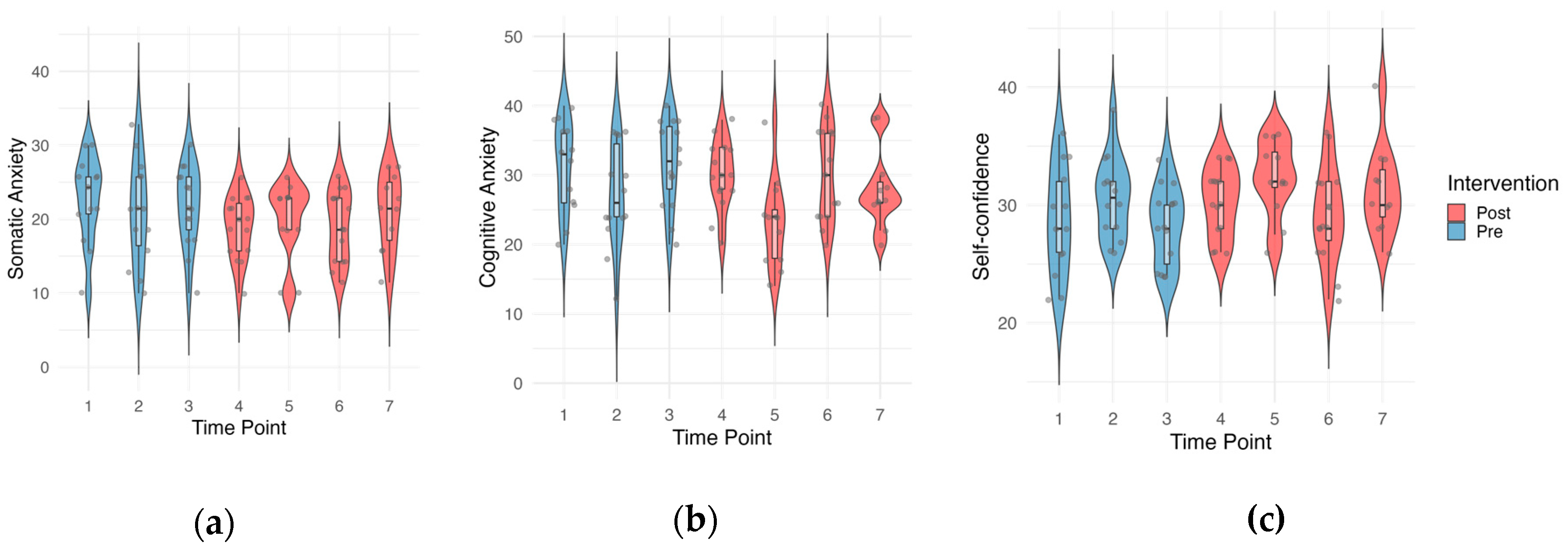

3.4.2. Subjective Measures

The CSAI-2 domains, self-confidence, somatic anxiety, and cognitive anxiety, were analyzed separately. The intervention led to significant improvement in all three domains. Changes in CSAI-2 subscales are depicted in

Figure 4.

For self-confidence, the fixed effect for intervention was positive and statistically significant (b = 0.055, SE = 0.017, t(66) = 3.30, p = .0016, adjusted R² = 0.0266). Random effects revealed low to moderate between-subject variability in baseline self-confidence (intercept SD = 0.095) and low within-subject fluctuations across competitions (residual SD = 0.078).

For somatic anxiety, the fixed effect for intervention was negative and statistically significant (b = –0.120, SE = 0.036, t(66) = –3.34, p = .0014; adjusted R² = 0.027). The random effects suggested moderate between-subject (intercept SD = 0.215) and moderate within-subject variation (residual SD = 0.169).

For cognitive anxiety, the fixed effect for intervention was negative and statistically significant (b = –0.081, SE = 0.026, t(66) = –3.13, p = .0026, adjusted R² = 0.0132). Random effects indicated moderate between-subject variability (intercept SD = 0.212) and moderate within-person variability across games (residual SD = 0.121).

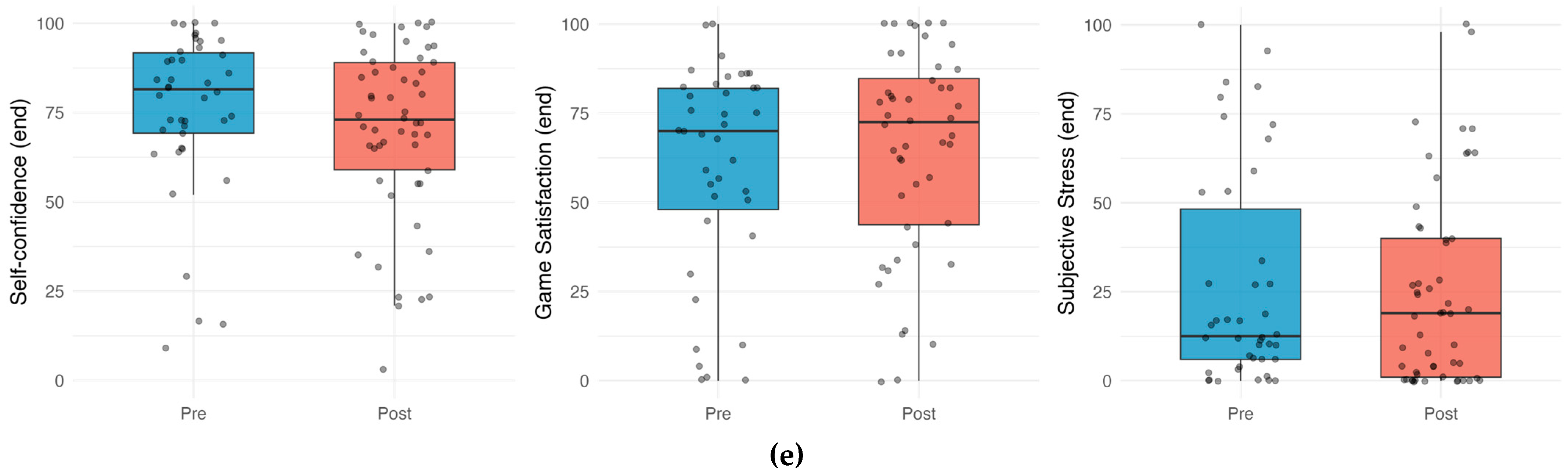

The VAS measures were analyzed separately for each construct, subjective stress, self-confidence, and game satisfaction, at half-time and the end of the game.

For half-time perceived stress, the effect of intervention was not statistically significant (b = 0.0012, SE = 0.1140, t(66) = 0.01, p = .9918, adjusted R² = –0.0108). The random intercept standard deviation was 0.424, and the residual SD was 0.538, indicating moderate variability both between and within participants. For end-game perceived stress, results were similarly non-significant (b = 0.020, SE = 0.222, t(66) = 0.088, p = .9298, adjusted R² = –0.0113). The random intercept SD was 0.621, and the residual SD was 1.052, showing higher individual baseline variability and within-subject fluctuation than in the half-time measure.

For half-time self-confidence, the effect of intervention was not statistically significant (b = –0.0002, SE = 0.0319, t(66) = –0.008, p = .9939, adjusted R² = –0.0108). Random intercept variability was moderate (SD = 0.112), with residual SD = 0.150. At the end-game, confidence scores also did not show any significant effect of intervention (b = –0.0735, SE = 0.0674, t(66) = –1.09, p = .2789, adjusted R² = 0.0022). The random intercept SD was effectively zero (0.0002), indicating no substantial between-subject baseline differences in end-game confidence, while the residual SD remained moderate (0.323).

For half-time game satisfaction, the effect of intervention was not significant (b = –0.0080, SE = 0.0917, t(60) = –0.087, p = .9307, adjusted R² = –0.0116). Random intercept variability was low (SD = 0.152), and residual SD = 0.417. For end-game satisfaction, again, no significant effect was observed (b = 0.0871, SE = 0.1016, t(60) = 0.86, p = .3945, adjusted R² = –0.0052). Between-participant variability remained low (SD = 0.107), while residual variability was moderate (SD = 0.464).

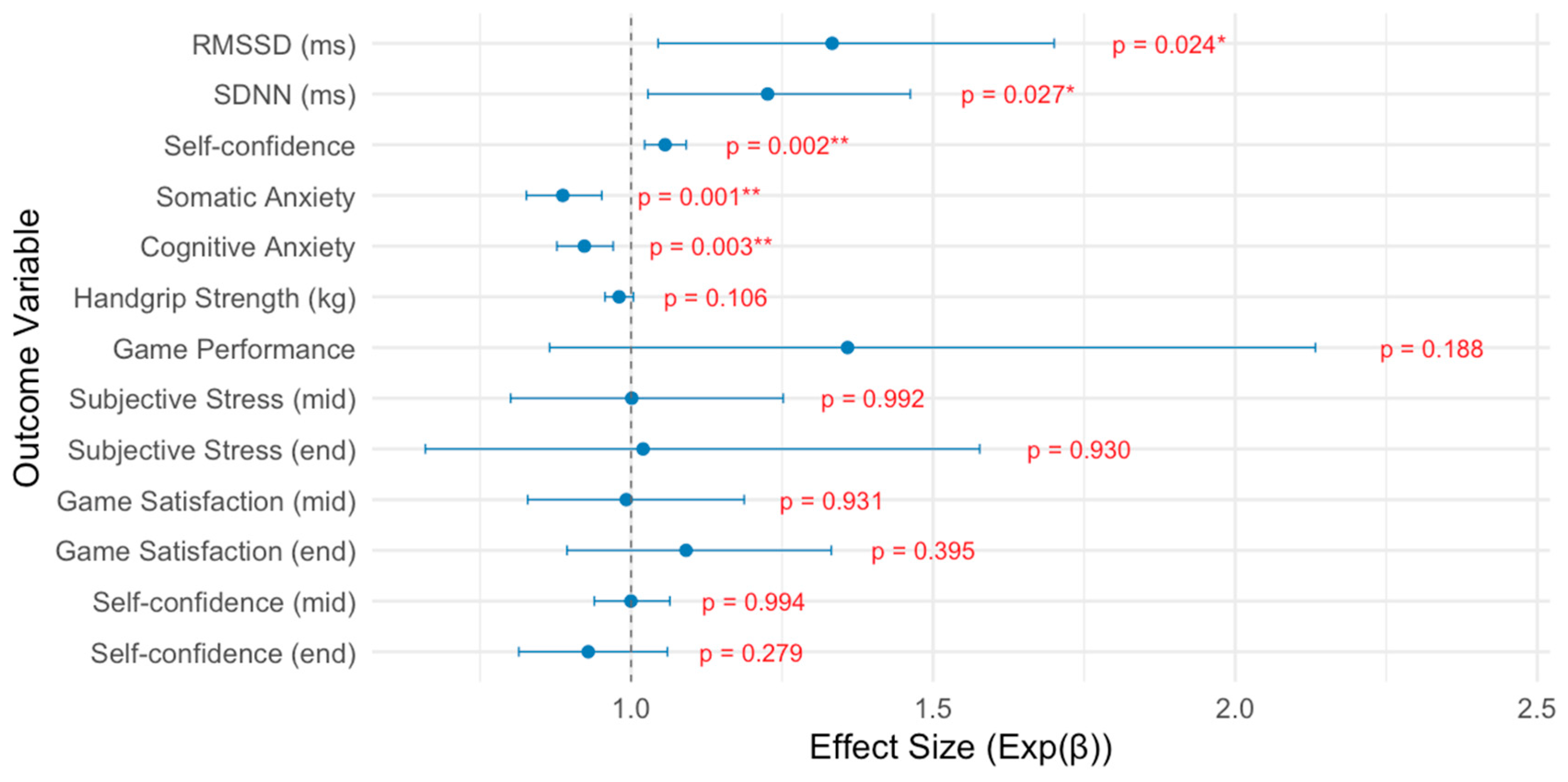

3.5. Effect Sizes

The intervention effects estimated by the Gamma-distributed GAMMs are expressed as exponentiated coefficients (Exp(

β)), which indicate multiplicative changes relative to the pre-intervention condition. For the physiological outcomes, RMSSD increased significantly with an Exp(

β) of 1.34 (p = .024), and a small-to-moderate effect size (r ≈ .28). SDNN likewise increased significantly (Exp(

β) = 1.22, p = .027, r ≈ .28). In contrast, handgrip strength showed, unexpectedly, a minor decline (Exp(

β) = 0.98, p = .106, r ≈ .20), and goal performance showed a non-significant increase (Exp(

β) = 1.36, p = .188, r ≈ .16). For the psychological outcomes (CSAI-2), self-confidence improved significantly (Exp(

β) = 1.06, p = .002), corresponding to a moderate effect size (r ≈ .38). Additionally, we found significant reductions in somatic anxiety (Exp(

β) = 0.89, p = .001, r ≈ .38) and cognitive anxiety (Exp(

β) = 0.92, p = .003, r ≈ .36). In contrast, the VAS results showed no meaningful intervention effects (

Figure 5). All model outcomes and variable correlations can be found in

Appendix B.

3.6. Game Outcome

According to the exploratory analyses, several VAS variables were affected by the result of the game. The effect of game outcome on half-time stress was statistically significant (b = –0.3447, SE = 0.1324, t(65) = –2.603, p = .0108, adjusted R² = –0.071). Between-participant variability was moderate (intercept SD = 0.513), and residual variability was moderate (residual SD = 0.526). For end-game stress, the fixed effect of game outcome was negative and statistically significant (b = –1.581, SE = 0.256, t(65) = –6.17, p < .001; adjusted R² = 0.149). The random effects suggested high between-subject variation (intercept SD = 1.574) and moderate within-subject variation (residual SD = 0.998).

Similarly, game outcome had a statistically significant effect on half-time confidence (b = 0.1475, SE = 0.0679, t(65) = 2.170, p = .0336, adjusted R² = 0.0012). Between-participant variability was low (SD = 0.204), and residual variability was moderate (SD = 0.274). For end-game confidence, the fixed effect of game outcome was positive and statistically significant (b = 0.435, SE = 0.076, t(65) = 5.75, p < .001; adjusted R² = 0.237). The random effects suggested low between-subject variation (intercept SD = 0.126) and moderate within-subject variation (residual SD = 0.318).

On the other hand, for half-time satisfaction, the fixed effect of game outcome was not statistically significant (b = 0.129, SE = 0.104, t(59) = 1.25, p = .2175; adjusted R² = –0.017). The random effects suggested low between-subject variation (intercept SD = 0.175) and moderate within-subject variation (residual SD = 0.422). For end-game satisfaction, the fixed effect of game outcome was not statistically significant (b = 0.210, SE = 0.111, t(59) = 1.90, p = .0619; adjusted R² = 0.021). The random effects suggested low between-subject variation (intercept SD = 0.129) and moderate within-subject variation (residual SD = 0.457).

3.7. Hypnosis Engagement

In the first post-measurement, all participants reported at least one instance of hypnosis engagement (League A: M = 2.42, SD = 1.16; League B: M = 2.00, SD = 1.00). Throughout the study, participants in League A listened to the audio recording more frequently (M = 5.45, SD = 3.47) than those in League B (M = 2.27, SD = 0.90). Even though the number of exposures differed significantly between teams (p = 0.022), it did not moderate the outcomes according to the exploratory analyses (all p-values > 0.5). Despite these differences in exposure frequency, both groups demonstrated similar average levels of hypnosis engagement (League A: M = 2.59, SD = 1.43; League B: M = 2.64, SD = 1.29).

3.8. Intervention Feedback

Participant feedback on the hypnosis intervention was collected at each post-measurement (e.g., positive effect of hypnosis on competitive performance and confidence before competition). On average, League A participants rated the intervention with 3.45 (SD = 1.44), while League B participants rated it with 3.27 (SD = 1.01) across both feedback domains. Qualitative responses revealed a range of experiences. Several participants reported feeling calmer before games and perceived the intervention as effective in enhancing confidence and reducing anxiety. In contrast, some participants mentioned that they fell asleep during the session or found the duration of the intervention too long, indicating varying levels of responsiveness.

4. Discussion

The study examined the psychophysiological effects of a team-tailored hypnosis intervention on young female handball athletes using a repeated-measures design during actual season games. Primary outcomes included HRV markers for stress assessment, handgrip strength, and goal count per game for physical performance, CSAI-2 for anxiety and self-confidence measurement, and VAS for momentary stress, satisfaction, and confidence assessment. Significant improvements in HRV markers RMSSD and SDNN were observed. Similarly, self-confidence was enhanced, while cognitive and somatic anxiety were reduced significantly. In contrast, handgrip strength, goal counts, and none of the VAS scales showed meaningful improvements. These findings partially support the hypotheses and underscore hypnosis as a promising intervention for improving psychological resilience in sports contexts. However, its effect on physical performance metrics was less evident.

A key feature of this study is that the hypnosis intervention was developed collaboratively for the entire team, yet each player was able to engage with it individually in their own setting. Even though only one tailored session was created and used repeatedly, the intervention still produced measurable improvements in psychophysiological regulation and psychological readiness. This underscores that a single, team-tailored intervention, even when individually applied, can be effective in enhancing athletes’ resilience and pre-competition readiness. However, it remains an open question how the outcomes might differ if the team were to engage with the hypnosis intervention collectively in a shared setting. While the individualized application of the team-tailored intervention already proved effective, experiencing the session together could potentially strengthen feelings of group cohesion, collective identity, and team flow.

Another notable strength of this study is its repeated-measures design, which allowed us to capture within-person changes over time rather than relying on single-timepoint comparisons. This approach was particularly helpful given that the data was collected during actual season games, where experimental control is limited compared to laboratory settings. Moreover, it enabled us to account for individual-level variability. As a result, this design enhanced both the ecological validity and statistical sensitivity of our findings.

While the results indicate positive effects of the audio-recorded hypnosis intervention on physiological regulation, anxiety, and self-confidence, the study was limited by the absence of randomization, lack of gender diversity, lack of including a control group, and the exclusion of individual differences in hypnotic suggestibility. Accordingly, these interpretations are preliminary and warrant further evaluation in future studies.

4.1. Psychophysiological State: HRV Improvements and Stress Regulation

The audio-hypnosis intervention led to significant improvements in both RMSSD and SDNN, two widely used time-domain markers of HRV (

Laborde et al., 2018). These findings provide the first physiological evidence that the hypnosis intervention enhanced athletes’ autonomic regulation before competition, which is critical for managing stress and maintaining focus in high-pressure environments.

While RMSSD is primarily driven by parasympathetic activity, SDNN is influenced by both sympathetic and parasympathetic inputs and serves as an overall indicator of autonomic balance (

Hinde et al., 2021;

Immanuel et al., 2023;

Machetanz et al., 2021). Increases in both metrics suggest a shift toward a more regulated and flexible autonomic state, which is associated with emotional resilience, improved cognitive control, and readiness for action (

Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017;

Laborde et al., 2018) These results support our first hypothesis and align with prior studies showing that HRV can be modulated through psychological interventions like hypnosis (

Hoffmann et al., 2024).

Interestingly, although the overall intervention effect on HRV was statistically significant, exploratory analyses showed that the number of times athletes listened to the hypnosis session did not significantly predict the degree of change. However, individual-level trends suggested that repeated exposure might still matter for certain participants. Some athletes showed progressive improvements across games, while others exhibited minimal or inconsistent change. This variability likely reflects individual differences in responsiveness to the intervention, which may be shaped by factors such as baseline levels, trait hypnotizability, or prior experience with mental training (

Elkins et al., 2015).

Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention was effective in improving autonomic markers of stress regulation at the group level, but its impact may vary depending on individual characteristics. Future research should explore these moderating factors more systematically, possibly through stratified designs or the inclusion of hypnotizability measures (SHSS;

Weitzenhoffer & Hilgard, 1962). Nonetheless, the observed increases in RMSSD and SDNN offer promising support for the use of sport-specific hypnosis as a tool for boosting psychophysiological readiness before competition in female athletes.

4.2. Physical Performance: Handgrip Strength and Goal Count

Contrary to our second hypothesis, the intervention did not significantly affect physical performance. In fact, a small decline in grip strength was observed over time, which may reflect potential carryover or fatigue effects due to the repeated-measures design. Nevertheless, the null finding on grip strength may simply reflect that the intervention targeted aspects, specifically emotional regulation, mental focus, and collective power during the game rather, not muscular strength. While prior research has shown that hypnosis can positively influence grip strength when it is the explicit focus of the intervention (

Nieft et al., 2024), this was not the case in our study. The “Super Mario” anchor, for example, was designed to be mentally activated for the game and associated with stretching, aiming to boost perceived energy and focus before the game. Therefore, expecting improvements in isolated handgrip strength may have been outside the intended scope of the intervention.

Moreover, goal performance, while an ecologically meaningful indicator for athletic output, was likely confounded by several uncontrolled variables that naturally increase over a competitive season, such as match difficulty, team dynamics, and opponent strength. Although the intervention included collective strength and group flow suggestions, these internal psychological changes may not directly translate to game statistics, especially given the multifactorial nature of goal performance. Thus, incorporating the game performance records of other teams or previous seasons as a control condition could offer a better approach in the future. Furthermore, the high between-subject variability further complicates the evaluation of the intervention effect. Therefore, these results suggest the need for more refined performance metrics and/or better-controlled experimental conditions in future research.

4.3. Psychological State: CSAI-2 and VAS

Significant improvements were observed across all three CSAI-2 subscales following the intervention, which supports our third hypothesis. Among the subscales, somatic anxiety showed the largest change, followed by cognitive anxiety and self-confidence. The baseline data revealed that cognitive anxiety levels were highest prior to the intervention, indicating substantial anticipatory worry and rumination prior to competition. The reduction in this domain suggests that the audio-hypnosis effectively targeted and reduced performance-related anxiety. Additionally, self-confidence improved significantly, proving the effect of the intervention on psychological pre-game measurements. These outcomes are favorable considering the Multidimensional Anxiety Theory (

Martens et al., 1990).

While CSAI-2 outcomes showed clear improvements, mid- and end-game VAS scores did not exhibit significant changes. Several factors may account for this discrepancy. First, responses on the VAS often clustered at the extremes, indicating limited scale sensitivity and possible ceiling or floor effects. To address the limitations of the VAS in future research, we recommend replacing or complementing it with structured assessment using 0-10 numeric rating scales. Second, the timing of the VAS administration might have introduced noise, as a relatively quiet and more controlled data collection phase was established prior to the competition, during which we measured HRV, CSAI-2, and handgrip strength. In contrast, the VAS was assessed during the game, a period characterized by numerous influencing factors that differentiate it from the pre-game measurements. This discrepancy may account for the significant results observed in the pre-game outcomes, while during-game measurements did not yield any significant results. Third, momentary stress perceptions and confidence in the game appeared to be more reactive to game outcomes than to pre-game preparation. Our exploratory analyses revealed that perceived stress levels and confidence at both half-time and end-game were significantly influenced by game results, with lower stress and higher confidence following positive outcomes. This pattern is unsurprising, given that negative outcomes are strongly associated with elevated stress and reduced confidence (

Berga et al., 2023;

La Fratta et al., 2021). In contrast, performance satisfaction outcomes were not affected by game outcome, suggesting a buffering effect of the intervention on individuals’ satisfaction with their performance. Overall, this indicates that audio-hypnosis contributed to emotional stability regardless of the external outcomes.

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

While our study demonstrates the potential of audio hypnosis to enhance competition readiness, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the lack of a control group prevents causal inference. Second, the exclusion of away-game data limits generalizability, particularly in unfamiliar settings. Third, although repeated-measures designs offer robustness, they can also carry potential carryover and fatigue effects (

Pabla et al., 2025). Finally, the sample consisted exclusively of female athletes from a single handball club, restricting the applicability of the findings to male teams or other team sports with different physical and psychological demands.

Future research should employ randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with active control conditions or groups, such as placebo relaxation or guided imagery, to better isolate the effect of the intervention. Additionally, stratifying participants by hypnotizability and collecting follow-up data on long-term effects could deepen our understanding of individual differences in response to such interventions. Lastly, including male athletes and other team sports could further expand the literature.

5. Conclusions

We provide first evidence that a sport-specific, team-tailored hypnosis intervention may significantly improve psychophysiological indicators of stress and enhance psychological readiness before competition in competitive youth athletes. While partly inconclusive, the overall findings support the feasibility and potential efficacy of integrating an audio-hypnosis into athletes’ mental preparation routines. The use of real-world game settings and repeated within-subject assessment marks a methodological advancement, boosting ecological validity. Yet, future studies should overcome present limitations by focusing on causality through RCTs with active control groups and exploring individual-level moderators such as motivation and responsiveness to hypnosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SY, SD and BS; methodology SY, SD and BS; data acquisition SY and BS; formal analysis SY; statistical analysis SY and BS; writing—original draft preparation SY; writing—review and editing SY, BS and SD; visualization SY; supervision SD and BS; project administration SY. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of JENA UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL (protocol code: 2024-3579-BO-A; date of approval 14.11.2024). The study was also preregistered at the German Clinical Trials Register under the project ID DRKS00035735.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects’ parents involved in the study since the participants were underaged.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Coach Olaf Schimpf for his cooperation during the data collection. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT-5 for the purposes of checking grammar, improving readability, and preparing the reference list. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANS |

Autonomic Nervous System |

| HRV |

Heart Rate Variability |

| RR intervals |

Peak-to-peak intervals of heart rate |

| RMSSD |

Root Mean Square of Successive Differences |

| SDNN |

Standard Deviation of Normal-to-Normal intervals |

| LF/HF ratio |

Low Frequency/High Frequency ratio |

| CSAI-2 |

Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 |

| VAS |

Visual Analog Scale |

| SHSS |

Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale |

| M |

Mean |

| MAD |

Median Absolute Deviation |

| GAMM |

Generalized Additive Models |

| AIC |

Akaike Information Criterion |

| LRT |

Likelihood Ratio Test |

| RTC |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

Appendix A

Chi-square statistics (χ²), Akaike Information Criterion (ΔAIC), and Bayesian Information Criterion (ΔBIC) from the likelihood ratio tests (LRTs), and corresponding p-values are reported here. Positive ΔAIC and ΔBIC values suggest improved model fit. Statistically significant effects are marked at **p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.005.

Table A.

Likelihood ratio test results comparing full and null models across outcome variables.

Table A.

Likelihood ratio test results comparing full and null models across outcome variables.

| Variable |

LogLik (Null) |

LogLik (Full) |

Δdf |

χ² |

ΔAIC |

ΔBIC |

p-value |

| RMSSD (HRV) |

-104.06 |

-98.44 |

1 |

11.24 |

9.24 |

6.72 |

<0.001*** |

| SDNN (HRV) |

-71.83 |

-66.13 |

1 |

11.40 |

9.40 |

6.88 |

<0.001*** |

| pNN50 (HRV) |

-102.53 |

-102.35 |

1 |

0.36 |

-1.64 |

-4.16 |

0.547 |

| Self-confidence |

78.46 |

82.77 |

1 |

8.62 |

6.62 |

4.06 |

0.003** |

| Somatic anxiety |

3.46 |

8.54 |

1 |

10.16 |

8.16 |

5.60 |

0.001** |

| Cognitive anxiety |

27.74 |

32.38 |

1 |

9.28 |

7.28 |

4.73 |

0.002** |

| Handgrip score |

102.73 |

104.02 |

1 |

2.60 |

0.60 |

-1.96 |

0.107 |

| Goal count |

-196.91 |

-197.11 |

1 |

-0.39 |

-2.39 |

-4.95 |

0.530 |

| Stress (mid-game) |

-51.96 |

-51.96 |

1 |

0.00 |

-2.00 |

-4.47 |

0.968 |

| Satisfaction (mid-game) |

30.54 |

30.54 |

1 |

0.00 |

-2.00 |

-4.55 |

0.986 |

| Confidence (mid-game) |

-27.52 |

-27.32 |

1 |

0.39 |

-1.61 |

-4.16 |

0.530 |

| Stress (end-game) |

-149.70 |

-149.77 |

1 |

-0.15 |

-2.15 |

-4.70 |

0.700 |

| Satisfaction (end-game) |

-57.68 |

-58.75 |

1 |

-2.13 |

-4.13 |

-6.60 |

0.144 |

| Confidence (end-game) |

-91.43 |

-91.42 |

1 |

0.01 |

-1.99 |

-4.55 |

0.929 |

Appendix B

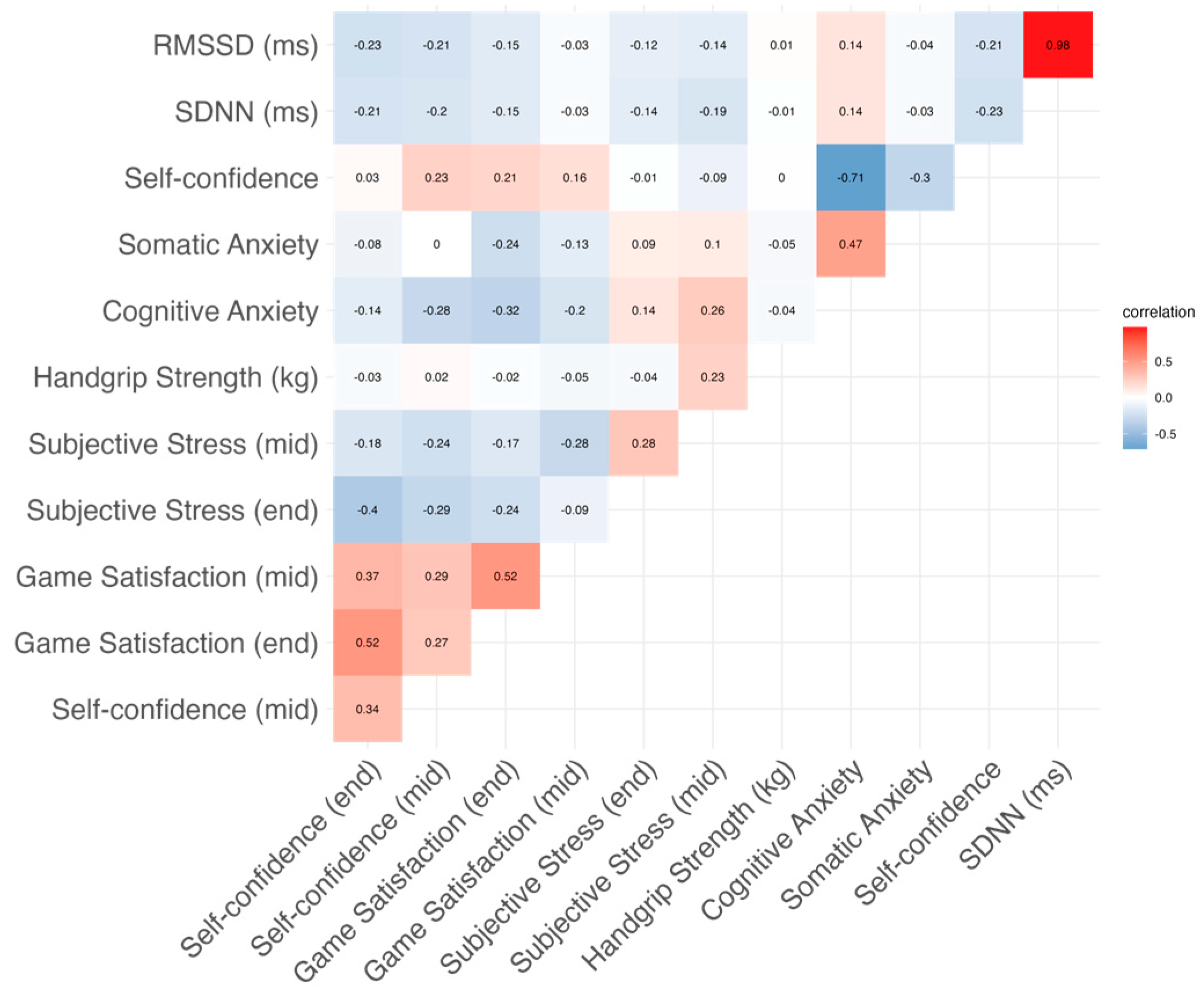

The results of the Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMMs) and the correlation matrix of all outcome variables are presented in

Appendix B.

Table B.

Results of Generalized Additive Mixed Models. Coefficients are presented on the log scale (Estimate) and as exponentiated values (Exp (Estimate)), interpretable as multiplicative effects. Model fit indices (AIC, LogLik) and corresponding p-values are reported.

Table B.

Results of Generalized Additive Mixed Models. Coefficients are presented on the log scale (Estimate) and as exponentiated values (Exp (Estimate)), interpretable as multiplicative effects. Model fit indices (AIC, LogLik) and corresponding p-values are reported.

| Variable |

Estimate |

Exp (Estimate) |

SE |

t value |

AIC |

LogLik |

p-value |

| RMSSD (HRV) |

0.287 |

1.333 |

0.124 |

2.31 |

204.88 |

-98.44 |

0.024* |

| SDNN (HRV) |

0.204 |

1.226 |

0.090 |

2.27 |

140.27 |

-66.13 |

0.027* |

| Self-confidence |

0.055 |

1.056 |

0.017 |

3.30 |

-157.54 |

82.77 |

0.002 |

| Somatic anxiety |

-0.120 |

0.887 |

0.036 |

-3.34 |

-9.08 |

8.54 |

0.001** |

| Cognitive anxiety |

-0.081 |

0.923 |

0.026 |

-3.13 |

-56.75 |

32.38 |

0.003** |

| Handgrip score |

-0.020 |

0.980 |

0.012 |

-1.64 |

-200.05 |

104.02 |

0.106 |

| Goal setting |

0.306 |

1.358 |

0.230 |

1.33 |

354.03 |

-173.01 |

0.188 |

| Stress (end-game) |

0.020 |

1.020 |

0.222 |

0.09 |

308.72 |

-150.36 |

0.930 |

| Confidence (end-game) |

0.087 |

1.091 |

0.102 |

0.86 |

125.49 |

-58.75 |

0.395 |

| Satisfaction (end-game) |

0.001 |

1.001 |

0.114 |

0.01 |

190.84 |

-91.42 |

0.992 |

| Stress (mid-game) |

-0.008 |

0.992 |

0.092 |

-0.09 |

111.92 |

-51.96 |

0.931 |

| Confidence (mid-game) |

0.000 |

1.000 |

0.032 |

-0.01 |

-53.08 |

30.54 |

0.994 |

| Satisfaction (mid-game) |

-0.074 |

0.929 |

0.067 |

-1.09 |

62.64 |

-27.32 |

0.279 |

Figure B.

Correlation matrix of all outcome variables.

Figure B.

Correlation matrix of all outcome variables.

References

- Adi, S., Aliriad, H., Wira Yudha Kusuma, D., Arbanisa, W., & Winoto, A. (2024). Athletes’ stress and anxiety before the match. Indonesian Journal of Physical Education and Sport Science, 4(1), 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Berga, D., Pereda, A., De Filippi, E., Nandi, A., Febrer, E., Reverte, M., & Russo, L. (2023). Measuring arousal and stress physiology on Esports, a League of Legends case study. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Blásquez, J. C., Rodas Font, G., & Capdevila Ortís, L. (2009). Heart-rate variability and precompetitive anxiety in swimmers. Psicothema, 21(4), 531–536.

- Chu, B., Marwaha, K., Sanvictores, T., Awosika, A. O., & Ayers, D. (2024). Physiology, stress reaction. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Cox, R. H., Martens, M. P., & Russell, W. D. (2003). Measuring anxiety in athletics: The revised Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 25(4), 519–533. [CrossRef]

- Dalmeida, K. M., & Masala, G. L. (2021). HRV features as viable physiological markers for stress detection using wearable devices. Sensors, 21(8), 2873. [CrossRef]

- de Melo, M. B., Daldegan-Bueno, D., Menezes Oliveira, M. G., & de Souza, A. L. (2022). Beyond ANOVA and MANOVA for repeated measures: Advantages of generalized estimated equations and generalized linear mixed models and its use in neuroscience research. European Journal of Neuroscience, 56(12), 6089–6098. [CrossRef]

- Elkins, G. R., Barabasz, A. F., Council, J. R., & Spiegel, D. (2015). Advancing research and practice: The revised APA Division 30 definition of hypnosis. The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 63(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [CrossRef]

- German Handball Federation. (2025). Available online: https://www.handball.net (accessed on 04 June 2025).

- Hasyim, A. H., Amirzan, Muhammad, Humaedi, & Sujarwo. (2023). The impact of sport hypnosis on volleyball athlete performance: An empirical study. Journal Sport Area, 8(3), 360–370. [CrossRef]

- Hinde, K., White, G., & Armstrong, N. (2021). Wearable devices suitable for monitoring twenty-four-hour heart rate variability in military populations. Sensors, 21(4), 1061. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, N., Strahler, J., & Schmidt, B. (2024). Starting in your mental pole position: Hypnosis helps elite downhill mountain bike athletes to reach their optimal racing mindset. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1334288. [CrossRef]

- Immanuel, S., Teferra, M. N., Baumert, M., & Bidargaddi, N. (2023). Heart rate variability for evaluating psychological stress changes in healthy adults: A scoping review. Neuropsychobiology, 82(4), 187–202. [CrossRef]

- La Fratta, I., Franceschelli, S., Speranza, L., Patruno, A., Michetti, C., D'Ercole, P., Ballerini, P., Grilli, A., & Pesce, M. (2021). Salivary oxytocin, cognitive anxiety and self-confidence in pre-competition athletes. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 16877. [CrossRef]

- Laborde, S., Mosley, E., & Thayer, J. F. (2018). Heart rate variability and cardiac vagal tone in psychophysiological research: Recommendations for experiment planning, data analysis, and data reporting. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 213. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Li, S. X. (2022). The application of hypnosis in sports. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 771162. [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M., Sherburn, M., Sisneros, C., Cooper, S., Lane, A. M., & Terry, P. C. (2022). Revisiting the self-confidence and sport performance relationship: A systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6381. [CrossRef]

- Machetanz, K., Berelidze, L., Guggenberger, R., & Gharabaghi, A. (2021). Brain–heart interaction during transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 15, 632697. [CrossRef]

- Martens, R., Burton, D., Vealey, R. S., Bump, L., & Smith, D. E. (1983). Competitive State Anxiety Inventory–2 (CSAI-2) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. [CrossRef]

- Martens, R., Vealey, R. S., & Burton, D. (1990). Competitive anxiety in sport. Human Kinetics.

- Nieft, U., Schlütz, M., & Schmidt, B. (2024). Increasing handgrip strength via post-hypnotic suggestions with lasting effects. Scientific Reports, 14, 23344. [CrossRef]

- Pabla, R. K., Graham, J. D., Watterworth, M. W. B., & La Delfa, N. J. (2025). Examining the independent and interactive carryover effects of cognitive and physical exertions on physical performance. Human Factors, 67(6), 560–577. [CrossRef]

- Patel, D. R., Omar, H., & Terry, M. (2010). Sport-related performance anxiety in young female athletes. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 23(6), 325–335. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T., Almeida, P. R., Cunha, J. P. S., & Aguiar, A. (2017). Heart rate variability metrics for fine-grained stress level assessment. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 148, 71–80. [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. (2024). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R (Version 2024.09.1+394) [Computer software]. Posit Software, PBC. http://www.posit.co/.

- Russell, G., & Lightman, S. (2019). The human stress response. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 15, 525–534. [CrossRef]

- Salai, M., Vassányi, I., & Kósa, I. (2016). Stress detection using low-cost heart rate sensors. Journal of Healthcare Engineering, 2016, 5136705. [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, E. H. (1991). Using hypnosis to improve performance of college basketball players. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 72(2), 536–538. [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F., & Ginsberg, J. P. (2017). An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 258. [CrossRef]

- Souza, R. A., Beltran, O. A. B., Zapata, D. M., Silva, E., Freitas, W. Z., Junior, R. V., da Silva, F. F., & Higino, W. P. (2019). Heart rate variability, salivary cortisol and competitive state anxiety responses during pre-competition and pre-training moments. Biology of Sport, 36(1), 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Speer, K. E., Semple, S., & Naumovski, N. (2020). Measuring heart rate variability using commercially available devices in healthy children: A validity and reliability study. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(1), 390–404. [CrossRef]

- The MathWorks, Inc. (2024). MATLAB (Version 2024a) [Computer software]. https://www.mathworks.com/.

- Vollmer, M. (2019, September). HRVTool: An open-source MATLAB toolbox for analyzing heart rate variability [Conference paper]. Computing in Cardiology (CinC), Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Weitzenhoffer, A. M., & Hilgard, E. R. (1962). Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale, Form C. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Wood, S. N. (2017). Generalized additive models: An introduction with R (2nd ed.). Chapman & Hall/CRC. [CrossRef]

- Wood, S. N. (2023). mgcv: Mixed GAM computation vehicle with automatic smoothness estimation (Version 1.9-0) [R package]. https://cran.r-project.org/package=mgcv.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).