1. Introduction

During last years, mindfulness has attracted growing interest in sports psychology, thanks to numerous studies demonstrating its effectiveness in increasing cognitive and regulatory abilities, improving sleep-wake rhythms, reducing stress, promoting psychological well-being, and enhancing athletic performance [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Mindfulness practices allow us to exercise what Gestalt refers to as the “continuum of awareness,” or the ability to be in deep contact with the experience unfolding in the present moment, facilitating the reduction of intrusive thoughts and automatic reactions, phenomena that are frequently associated with performance anxiety [

7,

8].

Similarly, the concept of flow has also been the subject of extensive attention in scientific and popular literature in the field of sports. In general, “flow” can be defined as “a state in which people are so immersed in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will pursue it even at great expense, for the sheer pleasure of doing so” [

9], p.4. Some authors have compared the state of flow to a state of grace. In Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

’s book, Good Business: Leadership, Flow, and the Making of Meaning, Ralph Shapey, a well-known contemporary composer, describes the state of musical grace as follows:

“The state of ecstasy is so profound that it takes over the feeling of no longer existing. I have experienced it many times. My hands seem detached from my body, and I have nothing to do with what is happening. I just sit and watch, in a state of amazement and wonder, as the music flows out of me. It is interesting to note that ecstasy is the result of our limited ability to concentrate. Our mind is unable to deal with too many stimuli at the same time. If we focus all our attention on a given task, such as climbing a mountain or writing music, we do not observe anything outside that narrow field of perception” [[

10], p.63]]. Currently, in sports, flow is defined as a state of deep immersion and involvement in a performance, in which the athlete experiences total concentration, a balance between challenge and skill, a sense of control, and a loss of perception of time [

9,

11]. Several studies have shown that flow is a key predictor of excellent performance, thanks to its link with optimal attentional and regulatory processes [

12,

13]. However, the most effective ways to enhance this experience remain an open area of research, subject of discussion that is still little considered and explored.

In this scenario, mindfulness appears to be a promising approach for facilitating the voluntary achievement of flow, as both conditions share characteristics related to attentional focus and psychophysiological arousal management [

14,

15]. Some preliminary studies suggest that interventions based on the principles of mindfulness can increase the frequency and intensity of flow experiences in athletes, while reducing anxiety and improving the quality of recovery and sleep-wake rhythms [

3,

16].

In light of these premises, this pilot study aims to evaluate the impact of a mindfulness-based protocol on flow state and other psychological and performance variables in a group of proballers, while also exploring the possible relationship between flow state and objective performance indicators.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a pilot study with the aim to evaluate the effectiveness of a weekly mindfulness protocol to improve sports performance and facilitate access to the Flow state during the playoffs in proballers. The protocol has involved 15 professional basketball players belonging to Serie A2 and Serie B teams during the last six weeks of the competitive season, randomly collected. The intervention consisted of a structured six-week mindfulness protocol. Each week, participants received an informed consensus and a guided audio track to listen to daily, lasting between 9 and 12 minutes. The tracks integrated body awareness, breathing, visualization, and grounding techniques, following a defined progression. The last two tracks guide athletes to achieve their flow state zone. The protocol was entirely digital, accessible via smartphone, and was supported by motivational reminders and weekly usage checks.

The assessment measures included:

- Flow State Scale-2 (FSS-2) to measure the subjective experience of flow. This tool of 36 item measures the subjective experience of flow through nine key dimensions, including challenge-ability balance, goal clarity, concentration, sense of control, and time transformation. [

17]

- Sport Anxiety Scale-2 (SAS-2) to measure performance anxiety. This tool of 15 items assesses sport performance anxiety on three factors: Cognitive Worry, Somatic Anxiety, and Concentration Disruption [

18].

- Mindfulness Inventory for Sport (MIS) consisting of 15 items and measures the degree of mindfulness applied to sport, divided into three dimensions: awareness, non-judgment, and refocusing [

19].

- RESTQ-Sport-36 for recovery quality and perceived stress. A tool of 36 ites designed to monitor the balance between perceived stress and recovery, using 12 scales related to stress and recovery factors [

20].

- Objective performance statistics (points, assists, rebounds, league rating) collected from official league data.

All psychological measures were administered in two stages: before the intervention (T0) and at the end (T5). Performance scores (points, assists, rebounds, league rating), the FFS-2, sleep data, and HRV were monitored weekly.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (v.27) and Python (v.3.10). Descriptive statistics were computed to summarize the sample characteristics, including means, standard deviations, and ranges for age and years of competitive activity, as well as frequency distributions for playing roles, league participation, and HRV device ownership. To assess changes over time, paired-sample t-tests were applied to compare scores between baseline (T0) and subsequent time points. Specifically, comparisons were made for each inventory used (FSS-2, SAS-2, MIS, and RESTQ-Sport-36) between T0 and T5. In addition, trend analyses and graphical representations (line plots) were used to illustrate score progression across six time points (T0–T5) for the FSS-2. To explore the relationship between psychological and performance variables, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated between athletes’ average Flow scores and performance metrics (points, assists, rebounds, and league evaluation). Correlations were interpreted according to Cohen’s guidelines. Furthermore, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted on four performance indicators (Points, Assists, Rebounds, League Evaluation) to derive a composite Performance Score. Finally, a simple linear regression was performed to evaluate the predictive role of Flow on overall performance. The regression model included the composite Performance Score as the dependent variable and the Flow score as the independent predictor. All assumptions for parametric tests (normality, homoscedasticity, linearity) were checked and met. Effect sizes and confidence intervals were computed where appropriate.

3. Results

The sample consists of 15 professional athletes, with an average age of 28 (SD = 6.05), between a range of 19 and 40 years. The average number of years of competitive activity is 13.07 (SD = 6.36), with a range from 2 to 23 years (

Table 1). The distribution of roles on the field is heterogeneous, including guards, forwards, centers, and point guards (

Figure 1). 66% percent of the athletes come from Serie A2 and the remaining 34% from Serie B. Only the 40% of the sample owns an HRV device.

The analysis of the average of the FSS-2 during the six weeks of the mindfulness protocol shows an upward trend. The initial average (T0) is 3.30 (SD = 0.58), while at T5 it reaches 4.62 (SD = 0.52), with a significant improvement (t = -4.27, p = 0.0037). The weekly trend graph shows a peak at T5, suggesting a cumulative effect of the intervention (

Figure 2). The

Table 2 presents the results of a paired-sample t-test comparing Flow State Scale (FSS) scores before the intervention (T0) and after five weeks of mindfulness training (T5). The analysis shows a statistically significant increase in FSS scores, indicating improved flow experiences following the intervention (t = -4.27, p = 0.0037). Descriptive statistics for all time points (T0–T5) are also reported, demonstrating a progressive upward trend across the six-week period. The

Table 3 reports the results of a paired-sample t-test comparing anxiety levels before the intervention (T0) and after two weeks of mindfulness training (T5). Both Somatic Anxiety and Total Anxiety showed a significant reduction from T0 (Mean = 1.13) to T5 (Mean = 0.00), with t = 8.50 and p < .000001 for both measures. This indicates a highly significant effect of the intervention in decreasing performance-related anxiety. The overall averages of the scores obtained by athletes at T0 and T5 on the MIS are as follows: T0 average (before the protocol): 3.58; T2 average (after the protocol): 3.40. The comparison of the MIS average scores obtained at T0 and T5 was not significant. The analysis of the subscales of the MIS, with a comparison of T0 vs T5 and a t-test for paired samples, did not report any significant results too. The RESTQ-Sport-36 also showed a slight improvement in some subscales, including “sleep quality” with an almost significant value (Mean T0=3.02; Mean T5= 2.71; T-Value= 2.084; p= 0.057), although this did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Paired Sample t-Test Results for Flow State Scale (FSS) Between T0 and T5.

Table 2.

Paired Sample t-Test Results for Flow State Scale (FSS) Between T0 and T5.

| Time |

Mean |

T |

p |

| T0 vs T5 |

T0 = 3.30, T5 = 4.62 |

-4.27 |

< 0.0037 |

| Time |

Mean FSS |

STD

FSS

|

| T0 |

3.30 |

0.57 |

| T1 |

3.73 |

0.72 |

| T2 |

3.55 |

0.55 |

| T3 |

4.00 |

0.85 |

| T4 |

3.87 |

0.99 |

| T5 |

4.62 |

0.51 |

Table 3.

Paired T-Test Results for Anxiety Measures (Sport Anxiety Scale – 2).

Table 3.

Paired T-Test Results for Anxiety Measures (Sport Anxiety Scale – 2).

| Measure |

Mean T0 |

Mean T5 |

T |

p |

| Somatic Anxiety |

1.13 |

0.00 |

8.50 |

< 0.000001 |

| Total Anxiety |

1.13 |

0.00 |

8.50 |

< 0.000001 |

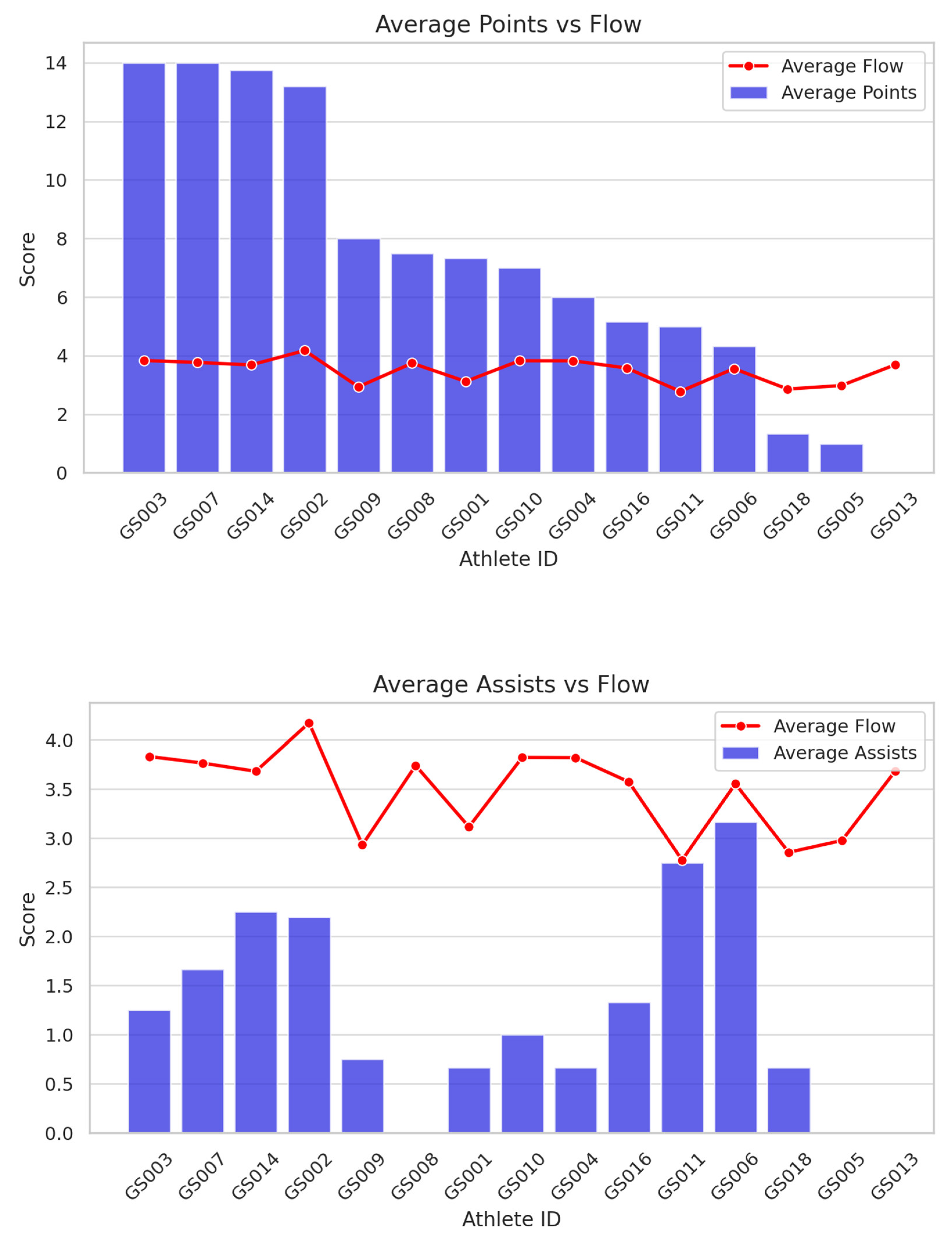

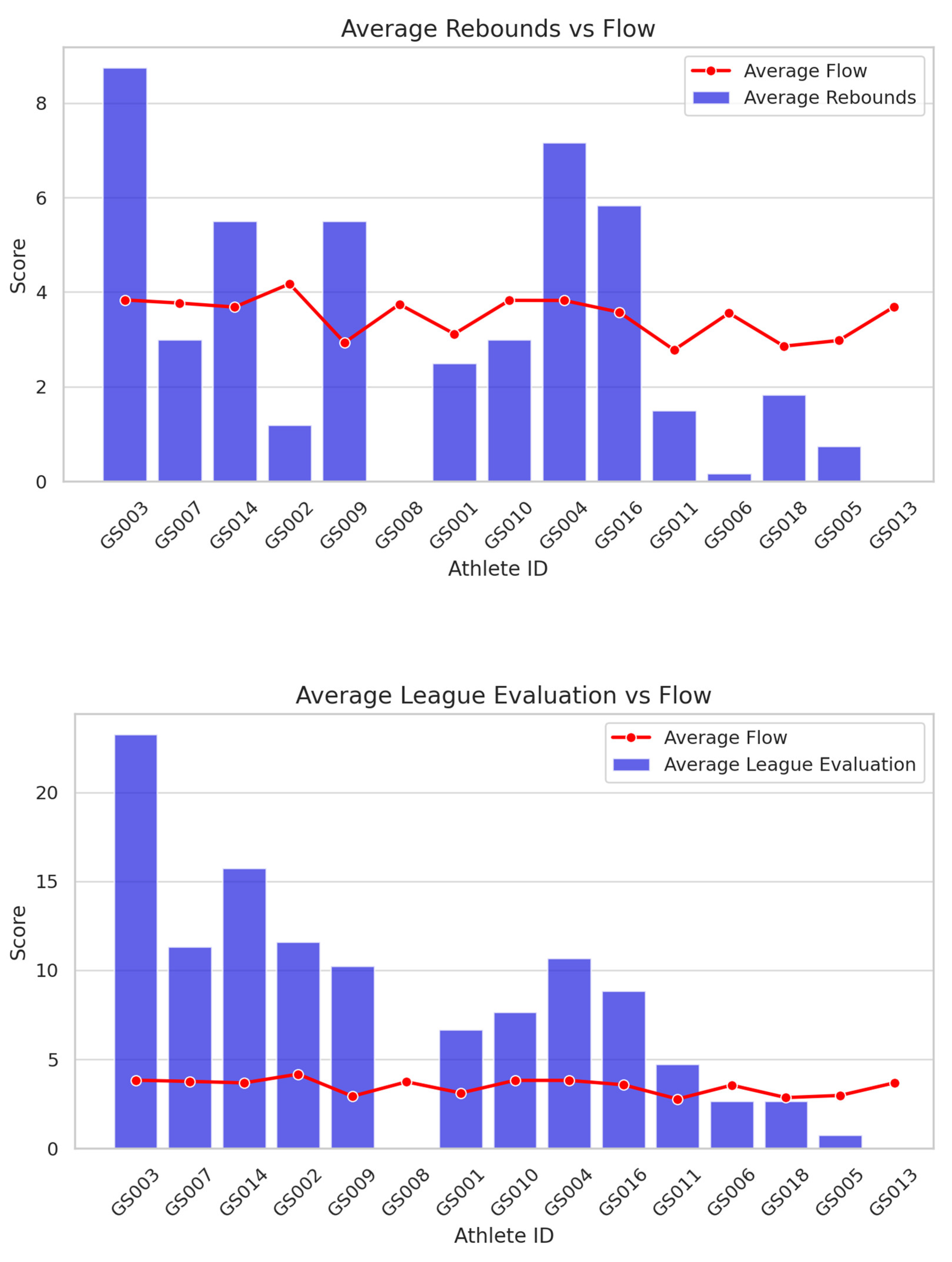

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed to examine the association between the athletes’ average Flow scores and their performance metrics (points, assists, rebounds, and league evaluation). The results showed (

Table 4):

Points: r = 0.65, indicating a strong positive correlation between Flow and points scored.

Assists: r = 0.26, indicating a moderate positive correlation between Flow and assists.

Rebounds: r = 0.32, suggesting a low-to-moderate positive correlation between Flow and rebounds.

League Evaluation: r = 0.59, indicating a strong positive correlation between Flow and the overall league performance index.

These findings suggest that higher Flow scores are associated with better overall performance, particularly in scoring points and achieving higher evaluation ratings. Assists also show a meaningful association, while the relationship with rebounds appears weaker, likely due to role-specific demands and less cognitive influence on this aspect of performance (

Figure 3).

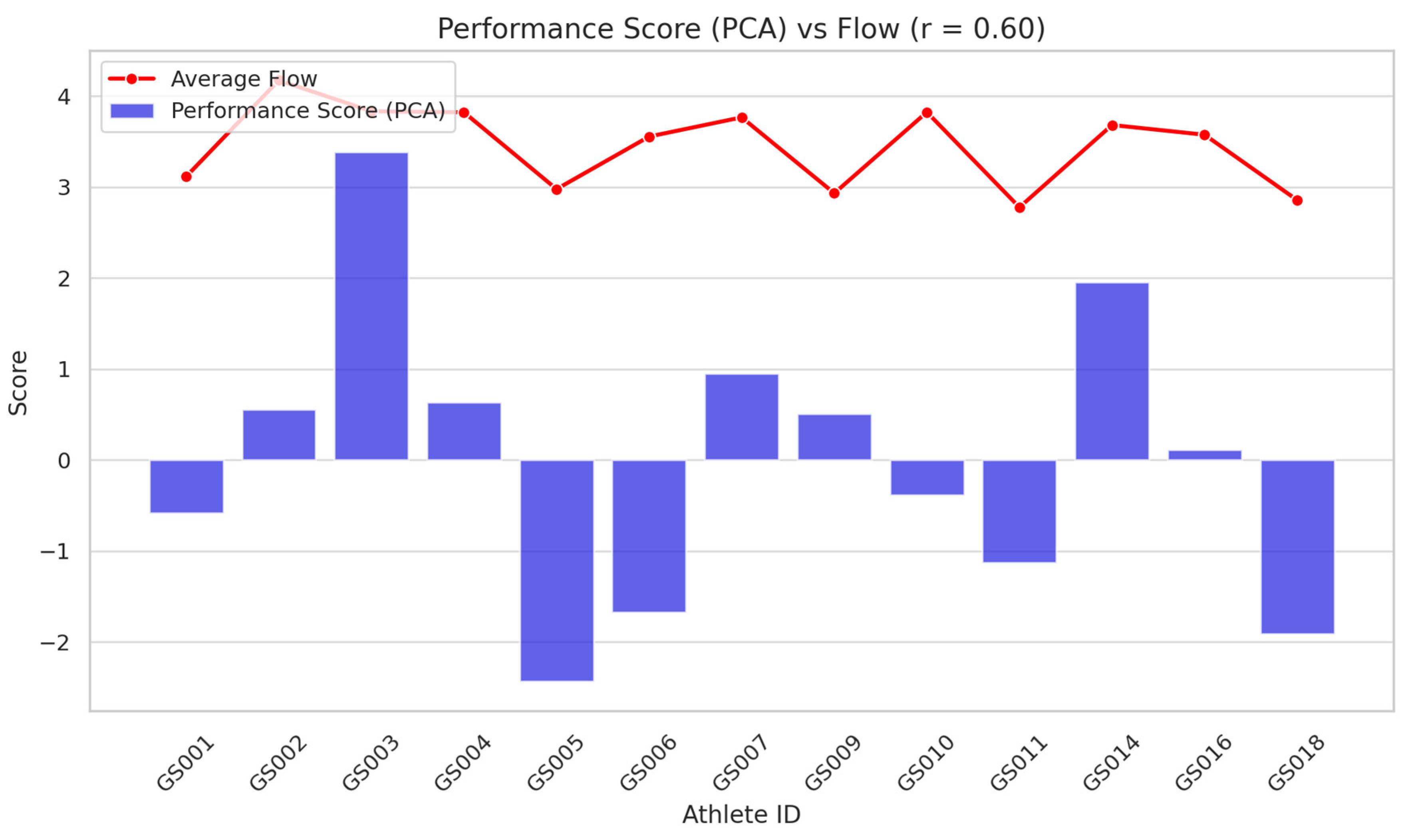

A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted on four key performance indicators: Points, Assists, Rebounds, and League Evaluation (

Table 5). The first principal component accounted for 60.1% of the total variance, which is considered adequate for constructing a composite performance index. This component was used as the Performance Score (PCA) for subsequent analyses.

A Pearson correlation analysis revealed a strong positive association between the Performance Score (PCA) and Flow (r = 0.60), indicating that athletes who reported higher levels of Flow also achieved better overall performance (

Table 5). This suggests that the subjective experience of Flow may play an important role in influencing objective game performance.

Figure 4 illustrates the relationship between Average Flow scores and the PCA-based Performance Score. The scatter plot shows a positive linear trend, confirmed by the regression line. The model indicates a strong positive association (β ≈ 0.85, R

2 ≈ 0.72), suggesting that higher Flow levels are associated with improved overall performance as captured by the composite PCA score.

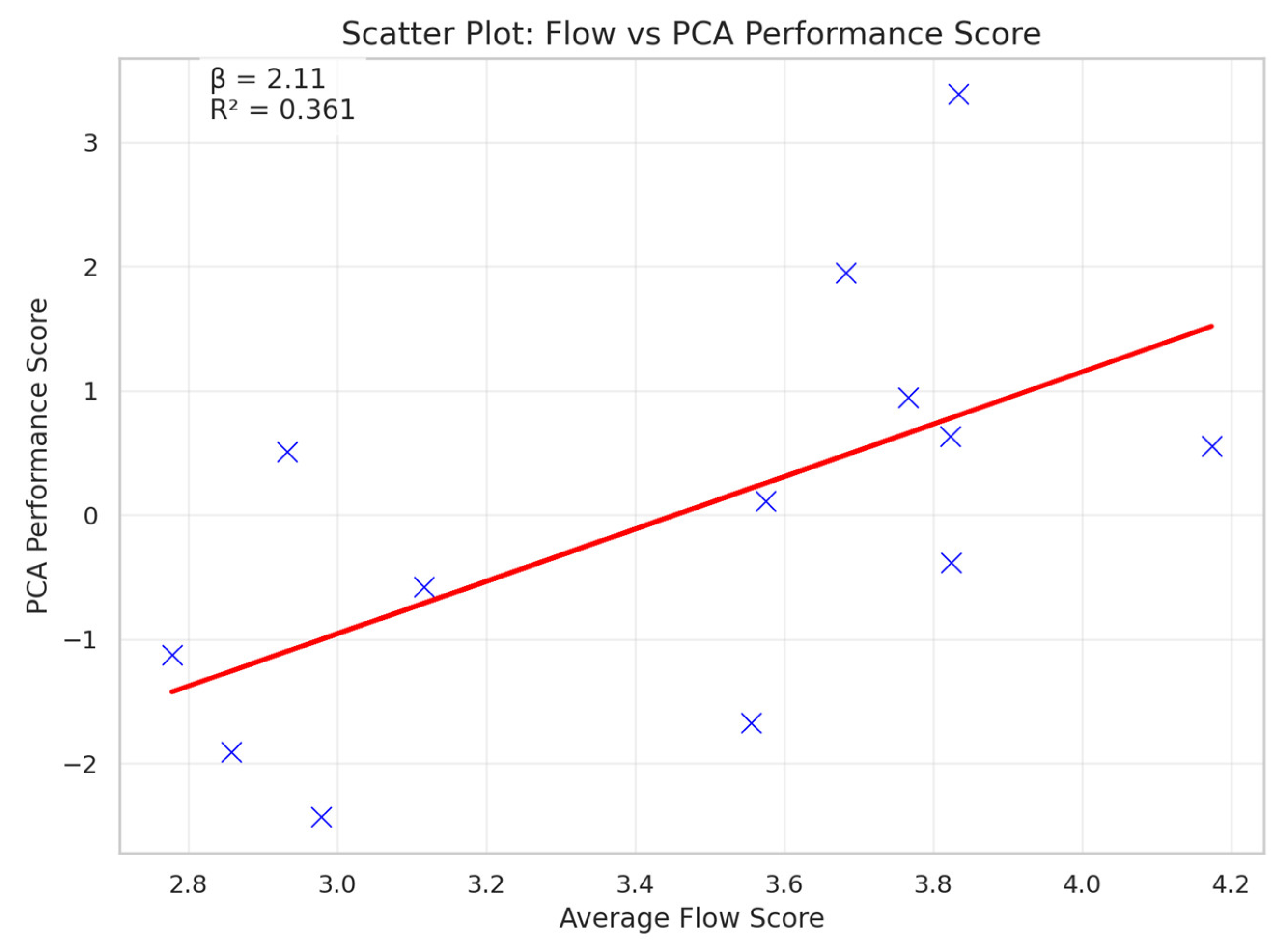

Also, a linear regression was performed to assess the association between Flow scores and PCA Performance Scores (points scored, rebounds, assists and League Evaluation) (

Table 6). The β coefficient was 2.11, with an R

2 of 0.361 and statistical significance p < .001. This indicates that approximately 36.1% of the variance in performance scores can be explained by the state of Flow, confirming the positive predictive effect of the Flow experience on athletic performance (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

The statistical analyses resulting from this pilot study, despite the limitations arising from the small sample size and the absence of a control sample, suggest a significant positive impact of the experimental protocol based on mindfulness on both the state of flow and anxiety levels of athletes.

In particular, the progressive increase in scores obtained in the questionnaire assessing subjective perception of access to Flow (FSS-2) during the six weeks of the protocol/mindfulness training, culminating in a statistically significant difference between T0 and T5, suggests that the protocol promoted a greater ability of athletes to enter a state of complete “contact” [

21] with the performance experience [

9,

11]. This finding is consistent with previous evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of mindfulness practices in promoting flow experiences in sports contexts [

22,

23].

At the same time, the significant reduction in both somatic anxiety and total anxiety, observed after just two weeks of intervention, confirms the potential of mindfulness techniques in reducing psychophysiological arousal and performance-related anxiety [

7,

8]. These results are extremely important, as the scientific community in this field is aware of the role played by anxiety as a factor interfering with sports performance, especially in disciplines where there is high competitive pressure [

24].

On the other hand, no significant changes were found in the average MIS scores and in the RESTQ-Sport-36 subscales. This suggests that the effectiveness of the protocol focused mainly on attentional and regulatory aspects related to flow, rather than on structural changes in perceived mindfulness skills or recovery quality. In this regard, it should be noted that flow is characterized by a high level of task focus associated with a significant reduction in internal and external distractions [

11]. The practice of mindfulness promotes precisely this latter condition, increasing the ability to maintain attention on the present moment and reducing attention dispersion, often related to intrusive thoughts or performance anxiety [

23,

26].

In addition to attentional aspects, flow also requires effective regulatory control, which allows athletes to modulate their physiological arousal levels and emotional responses according to the demands of the task. The techniques proposed in the protocol probably facilitated this process, allowing for better management of arousal and emotions during competition, thus promoting the maintenance of an optimal psychophysiological state for performance [

7,

22].

The fact that no significant changes emerged in the measures assessing predisposition to mindfulness (MIS), while flow showed a significant increase, suggests that the effectiveness of the protocol focused mainly on contextual and situational skills rather than stable traits. In other words, the intervention seems to have acted on attentional and regulatory processes directly involved in the optimal experience during competition, without significantly altering the general characteristics of awareness. The latter change would probably be desirable with stable and longer-term training, such as mental coaching or an extended intervention, which helps the athlete on a path of self-awareness and awareness of their personality functioning, their script, and their system of beliefs and decisions [

27,

28] during sports performance.

However, the almost significant trend observed in the RESTQ’s “sleep quality” subscale gives rise to the hypothesis that a longer intervention, or simply one with a larger sample size, could have led to more extensive improvements in psychophysical recovery [

29].

The most interesting finding certainly concerns the relationship between flow and performance. The positive correlations that emerged between the average flow scores and the performance indicators collected (points, assists, overall evaluation) confirm what has been reported in the literature on the link between states of optimal experience and performance in competitions [

11,

30]. The highest correlation with the overall evaluation score of the reference league (r = 0.74) suggests that flow not only affects individual technical skills, but also seems to have a significant impact on more integrated and complex aspects of performance, such as the ability to read the game and effective decision-making.

PCA analysis allowed us to synthesize performance variables into a single composite index, explaining over 60% of the variance and confirming the robustness of this approach for performance evaluation [

31]. Furthermore, linear regression showed that flow explains 36.1% of the variance in performance, highlighting the relevance of this psychological dimension as a predictor of competitive success. This result reinforces theories that optimizing attentional and motivational states is a determining factor for high-level performance [

32].

Overall, the data obtained are promising and confirm the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in improving key psychological variables for sports performance and suggest a central role for flow as a mediator between attentional processes and competitive results. This evidence supports the opportunity to integrate structured mental training programs into the preparation of professional athletes, in line with recent approaches to sports psychology [

25].

5. Conclusions

This exploratory study provides preliminary evidence on the effectiveness of a mindfulness-based protocol in increasing and promoting the experience of flow, significantly reducing anxiety levels in professional athletes. The results show a significant improvement in the state of flow and a marked decrease in performance anxiety after just the first few weeks of intervention, elements that are key factors for optimal performance. Although no significant changes were found in measures describing the degree of predisposition to mindfulness, the data suggest that the intervention acted on attentional and situational regulatory processes, influencing the quality of the experience during the competition rather than stable personality traits.

A particularly relevant aspect is the positive correlation found between flow and performance, confirmed by both correlation analysis and linear regression, which attributes a substantial predictive role to flow in terms of performance. This result reinforces the need for psychological interventions aimed at developing attentional-regulatory skills to promote states of optimal experience, with potential benefits for overall performance.

However, these data should be interpreted with caution due to methodological limitations, particularly the small sample size and the absence of a control group. Future studies should include larger samples, controlled experimental designs, and longer-term protocols in order to consolidate the results and further investigate the impact of mindfulness on psychophysical recovery variables and more stable awareness traits. Despite these limitations, the results offer promising indications for the integration of mindfulness-based mental training programs in the preparation of high-level athletes, in line with the most recent models of sports psychology.

Limitations and Future Prospects

Among the main limitations of the study are the absence of a control group, the limited sample size, and the subjective self-assessment of flow. Although our research design allowed for the possibility of obtaining objective measures of flow related to psychophysiological parameters, only 40% of the sample had a device for detecting these parameters, which prevented us from obtaining numerically valid measurements for comparison within and between subjects. We anticipate that future studies will include physiological measurements (HRV, EEG), post-intervention qualitative assessments, and larger samples. It would also be useful to compare different mindfulness approaches (MBCT, ACT, Yoga Nidra) to assess their comparative effectiveness in sports contexts.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Code for Research in Psychology of the Italian Association of Psychology (AIP), approved in 2015 and updated in July 2022 to comply with GDPR regulations (aipass.org). The study has been approved by the ethical committee of the University of Naples Vanvitelli (n.26/2025). All procedures adhered to ethical standards to protect participants, ensuring anonymity, data confidentiality, and obtaining informed consent.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request (dr.valeria.cioffi@gmail.com). Due to privacy and ethical considerations, the data are not publicly accessible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E. (2017). Mindfulness-based and acceptance-based interventions in sport and performance contexts. Current opinion in psychology, 16, 180-184. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, A., Palmer, C., Byrne, C., & Pryle, J. (2024). A visual phenomenology of mindfulness after COVID-19. Journal of Qualitative Research in Sports Studies, 18(1), 129-138.

- Röthlin, P., Horvath, S., Trösch, S., Holtforth, M. G., & Birrer, D. (2020). Differential and shared effects of psychological skills training and mindfulness training on performance-relevant psychological factors in sport: a randomized controlled trial. BMC psychology, 8(1), 80. [CrossRef]

- Jones, M. I. , et al. (2020). Mindfulness and performance in sport and exercise: An overview. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 1-21.

- Baltzell, A., & Akhtar, V. L. (2014). Mindfulness meditation training for sport (MMTS) intervention: Impact of MMTS with division I female athletes. The Journal of Happiness & Well-Being, 2(2), 160-173.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future.

- Josefsson T, Ivarsson A, Lindwall M, Gustafsson H, Stenling A, Böröy J, Mattsson E, Carnebratt J, Sevholt S, Falkevik E. (2017) Mindfulness Mechanisms in Sports: Mediating Effects of Rumination and Emotion Regulation on Sport-Specific Coping. Mindfulness (N Y). 2017;8(5):1354-1363. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gross, J. J., et al. (2016). Emotion regulation in sport: Current status and future directions. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 9(1), 45–69.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Csikzentmihaly, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience (Vol. 1990, p. 1). New York: Harper & Row.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2004). Good business: Leadership, flow, and the making of meaning. Penguin. In: Mumford, G. (2023). La mentalità vincente. I segreti per superare le sfide più grandi nello sport e nella vita. Giunti editore.

- Jackson, S. A., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). Flow in sports: The keys to optimal experiences and performances. Human Kinetics.

- Swann, C. , et al. (2017). A systematic review of the experience, occurrence, and controllability of flow states in elite sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 32, 41–51.

- Smith, B., et al. (2019). Flow state and performance in sport: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 43, 78–88. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, K. A., Glass, C. R., & Pineau, T. R. (2009). Mindful sport performance enhancement: A training manual for athletes. American Psychological Association.

- Kee, Y. H., & Wang, C. K. J. (2008). Relationships between mindfulness, flow dispositions and mental skills adoption: A cluster analytic approach. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 9(4), 393–411. [CrossRef]

- Baltzell, A., & Summers, J. (2018). The Power of Mindfulness in Sport: Finding Flow in Athletic Performance. Routledge.

- Jackson, S. A., & Eklund, R. C. (2004). The Flow Scales Manual. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Smith, R. E., Smoll, F. L., Cumming, S. P., & Grossbard, J. R. (2006). Measurement of multidimensional sport performance anxiety in children and adults: The Sport Anxiety Scale-2. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 28(4), 479–501. [CrossRef]

- Thienot, E., Jackson, B., Dimmock, J. A., Grove, J. R., Bernier, M., & Fournier, J. F. (2014). Development and preliminary validation of the Mindfulness Inventory for Sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 15(1), 72–80. [CrossRef]

- Kellmann, M., & Kallus, K. W. (2016). The Recovery-Stress Questionnaire for Athletes: User manual. Human Kinetics.

- Perls, F. , Hefferline, R. E., & Goodman, P. (1951). Gestalt Therapy Excitement and Growth in the Human and Personality.

- Kaufman, K. A. , Glass, C. R., & Pineau, T. R. (2009). Mindful sport performance enhancement: A training manual for athletes. American Psychological Association.

- Kee, Y. H., & Wang, C. K. J. (2008). Relationships between mindfulness, flow dispositions and mental skills adoption: A cluster analytic approach. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 9(4), 393–411.

- Martens, R., Vealey, R. S., & Burton, D. (1990). Competitive anxiety in sport. Human Kinetics.

- Birrer, D., Röthlin, P., & Morgan, G. (2012). Mindfulness to enhance athletic performance: Theoretical considerations and possible impact mechanisms. Mindfulness, 3(3), 235–246. [CrossRef]

- Röthlin, P. , Horvath, S., Birrer, D., & Grosse Holtforth, M. (2020). Psychological skills training and mindfulness-based interventions in sports: A meta-analytical review. Sports Psychology, 34(4), 361–386.Arrow, K. J., & Intriligator, M. D. (1982). Handbook of mathematical economics (Vol. 3). North-Holland.

- Woollams, S. , & Brown, M. (1978). Transactional analysis: A modern and comprehensive text of TA theory and practice. Huron Valley Institute Press.

- Berne, E. (2022). Transactional analysis in psychotherapy: A systematic individual and social psychiatry. Echo Point+ ORM.

- Fullagar, H. H., Vincent, G. E., McCullough, M., Halson, S., & Fowler, P. (2023). Sleep and sport performance. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology, 40(5), 408-416.

- Swann, C., Keegan, R., Piggott, D., & Crust, L. (2012). A systematic review of the experience, occurrence, and controllability of flow states in elite sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(6), 807–819.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Hodge, K., Lonsdale, C., & Jackson, S. A. (2009). Athlete engagement in elite sport: An exploratory investigation of antecedents and consequences. The Sport Psychologist, 23(2), 186–202.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).