1. Introduction

Drought is a natural hazard. Agricultural drought is caused by a convergence of factors: deficient precipitation (meteorological drought), insufficient moisture content in the soil, and decreased groundwater or water storage levels necessary to support irrigation (hydrological drought) [

1]. Global warming has led to an increased frequency and intensity of meteorological hazards, resulting in more frequent and severe agricultural droughts. This will lead to a significant reduction in agricultural production throughout. According to FAO [

1], the loss in agriculture due to drought is the highest compared with other hazards, accounting for over 60%, and crops are the most sensitive subsector, accounting for 49%.

Legumes (Fabaceae) hold the second position after cereals in food production. They can be considered one of the most promising components of the Climate Smart Agriculture concept. When cultivated in rotation with cereals, legumes contribute to preventing soil erosion, reducing soil pathogens, and improving the soil’s nutrient composition. Legumes are also sensitive to drought. Typically, they depend on rainfall and are susceptible to drought stress throughout their vegetative and reproductive growth phases. Regarding the common bean, yield loss was up to 60.8% with a 60 - 65% soil water deficit, followed by the green gram and cow pea, with losses 45.3 and 44.3%, respectively [

2]. In addition, the faba bean (

Vicia faba L.) showed decreases in the chlorophyll content, soluble sugars, ascorbate peroxidase, activity of catalase, and activity of peroxidase, as well as increases in the malondialdehyde and H

2O

2 accumulation at a 40% field capacity [

3]. The soybean cultivars also exhibited reductions in photosynthetic efficiency, stomatal conductance, and the transpiration rate [

4].

To mitigate such adverse effects, associations between plants and fungi, such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, plant growth-promoting fungi, dark septate endophytes (DSE), and other endophytic fungi, have become viewed as a promising biological approach. In particular, DSE colonization has been shown in some studies to alleviate drought stress by enhancing root morphology, boosting osmotic regulation capacity, and maintaining the cellular status under water-deficient conditions [

5,

6].

DSE represent a polyphyletic group of root-associated fungi, primarily belonging to the phylum Ascomycota, characterized by melanized, septate hyphae, and the formation of microsclerotia within host roots [

7,

8]. Over the past few decades, several genera have been frequently reported and studied regarding for their symbiotic roles with plants, including

Phialocephala,

Phialophora,

Leptodontidium, and

Periconia [

7,

9]. These fungi colonize roots both inter- and intracellularly but usually remain asymptomatic to the host [

10,

11]. Numerous DSE species have been shown to enhance plant nutrient acquisition (e.g., carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus) [

9,

12] and improve plant tolerance to drought and pathogens [

13]. Despite their morphological diversity, DSE taxa share a common ecological strategy: they form various biotrophic associations that enable them to persist across a wide range of environments, particularly under extreme conditions such as arid soils [

9]. Consequently, they play an important role in mediating plant adaptation to environmental stress.

The genus

Cercophora (Lasiosphaeriaceae, Sordariales) comprises ascomycetous fungi commonly isolated from soil, dung, and decaying plant materials [

14,

15,

16]. Traditionally,

Cercophora species have been regarded as saprobic fungi. Members of this genus are typically characterized by large, dark-colored ascomata with membranous to leathery walls and hyaline, cylindrical ascospores that develop a distinct, swollen, pigmented tip [

14]. However, recent molecular and culture-based studies reported the occurrence of

Cercophora species as root-associated or endophytic fungi [

17,

18]. Despite these findings, the functional potential of

Cercophora in symbiotic plant-fungus interactions has received limited attention. In particular, there is a lack of evidence on whether

Cercophora species can establish stable endophytic associations that promote host plant growth or improve stress tolerance. Therefore, investigating

Cercophora as a potential endophyte contributing to legume growth under drought stress could provide new insights into the hidden diversity and ecological functions of root endophytic fungi.

This study aimed to isolate and characterize Cercophora sp. isolates from legume roots grown in agricultural soils, and evaluate their potential to promote legume growth under drought stress. Specifically, the objectives were to:

(1) identify and describe the morphological and molecular characteristics of Cercophora sp. isolates and assess their drought tolerance

(2) evaluate their effects on the early vegetative growth of legumes

(3) determine whether inoculation with Cercophora sp. enhances plant physiological performance under drought conditions

By setting these objectives, this research provides new insights into the ecological and functional roles of Cercophora sp. as members of the endophytic fungal community.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungi Isolation

A baiting experiment was conducted using soil samples collected in July 2023 from conventional fields with seven different fertilizer histories at the Tsukuba Plant Innovation Research Center, Tsukuba City, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan. The treatments included no fertilizer (control), non-potassium (NK), non-nitrogen (NN), non-phosphorus (NP), a compound fertilizer containing nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK), compost (Com), and a combination of NPK and compost (NPKC).

Seeds of the mung bean (

Vigna radiata; Greenfield Project Organic Seeds, Japan) were surface-sterilized by immersion in 70% ethanol for 1 min, followed by 1% sodium hypochlorite for 8 min. The seeds were then rinsed three times with sterilized distilled water for 3 minutes each time, dried overnight, and placed on 1.5% water agar (WA; 15 g·L⁻¹ Bacto agar (Difco Laboratories)) in 9-mm Petri dishes. After three days, seedlings (one per pot) were transplanted into 90-mm-diameter pots containing 150 g of soil (three pots per treatment) and grown for one month under ambient conditions with temperatures ranging from 30 to 35°C, and optimal soil moisture, in August 2023. After one month, watering was withheld until the leaves wilted (approximately 4-5 days). The roots of mung bean plants from each replicate were surface-sterilized following the method of Narisawa et al. [

19]. They were washed under running tap water to remove soil particles and cut into approximately 1-cm segments. Twenty root segments were randomly selected from each plant, washed three times in 0.005% Tween 20 (J.T. Baker Chemical Co., Phillipsburg, NJ, USA) for 1 min each time, and rinsed three times with sterile distilled water (SDW) for 1 min each time. The root segments were air-dried overnight and plated on nutrient agar containing 25 g·L⁻¹ cornmeal (Infusion form; Difco Laboratories) and 15 g·L⁻¹ Bacto agar.

The plated roots were incubated at room temperature (approximately 24°C) for one week. Emerging mycelia from root fragments were transferred to 50-mm Petri dishes containing half-strength cornmeal malt yeast extract (½ CMMY; 25 g·L⁻¹ cornmeal, 15 g·L⁻¹ Bacto agar, 10 g·L⁻¹ malt extract (Difco Laboratories), 2 g·L⁻¹ yeast extract (Difco Laboratories)) agar to obtain pure colonies. The plates were incubated at 24°C for 3 weeks.

2.2. DNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Phylogenetic Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from fungal mycelia using PrepMan™ Ultra Sample Preparation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Warrington, UK). The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the nuclear ribosomal DNA was amplified and sequenced using the primer pair ITS1F/ITS4 [

20,

21]. PCR amplification was performed in a 50 µL reaction mixture (1 µL of genomic DNA (~100 ng), 1.5 µL of 0.2 µM of each primer, 10 µL of 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 25 µL of 2× PCR buffer for KOD X Neo, 1 µL of KOD FX Neo polymerase, and 10 µL of SDW). PCR was conducted in a Takara PCR Thermal Cycler Dice (Takara Bio Inc., model TP 600, Kusatsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 94°C for 4 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 35 s, 52°C for 55 s, and 72°C for 2 min; followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min for ITS. PCR products were purified using a mixture of 12 µL of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 4.8), 30 µL of 40% PEG, and 1.5 µL of 200 mM MgCl₂. Sequencing reactions were carried out in a 10 µL mixture (0.32 µL of 0.2 µM of each primer, 1.5 µL of 5× sequencing buffer, 0.5 µL of BigDye Terminator v3.1, 6.68 µL of SDW, and 1.0 µL of purified DNA). The cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 96°C for 2 min; 25 cycles of 96°C for 30 s, 50°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 3 min. Sequencing products were purified as previously described, resuspended in 20 µL of Hi-Di™ formamide (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA), and analyzed using a the BigDye Terminator v3.1 sequencing system.

The obtained sequences were edited with MEGA version 12. The resulting ITS sequences were compared with reference sequences in the NCBI database (

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) using the BLAST algorithm.

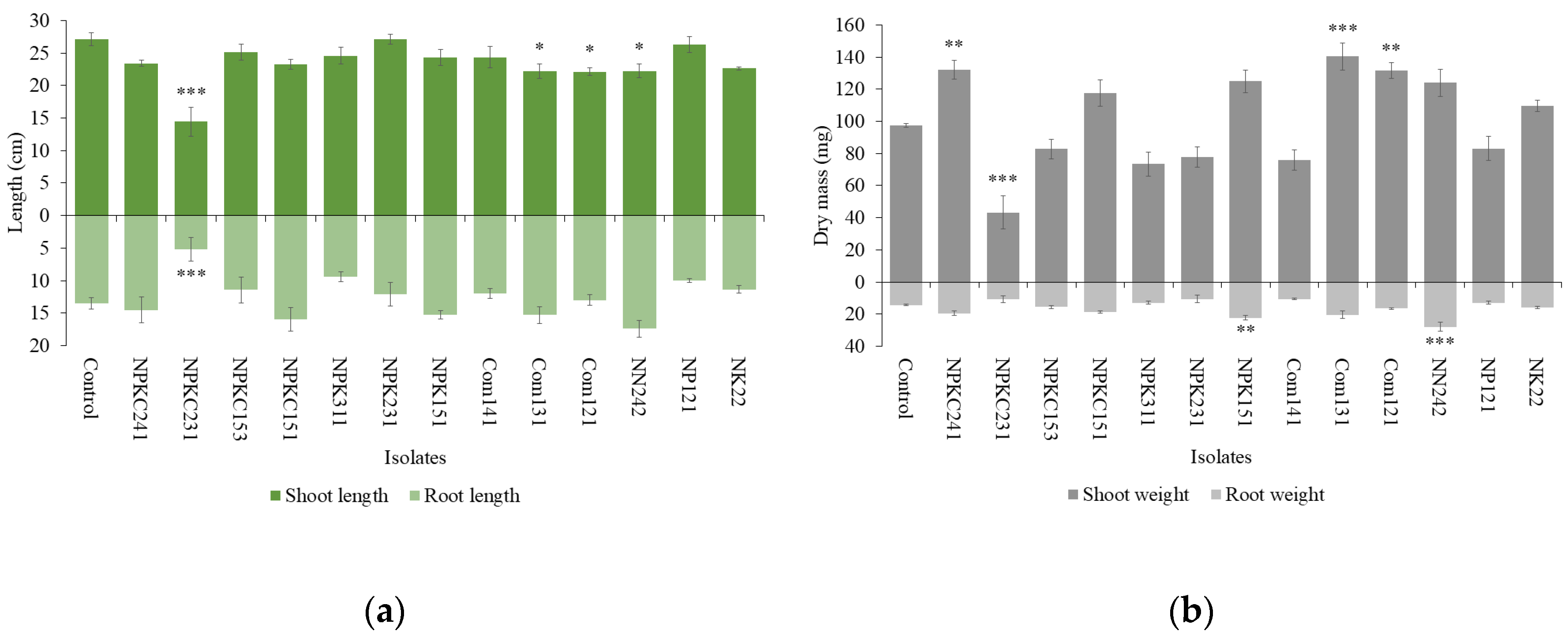

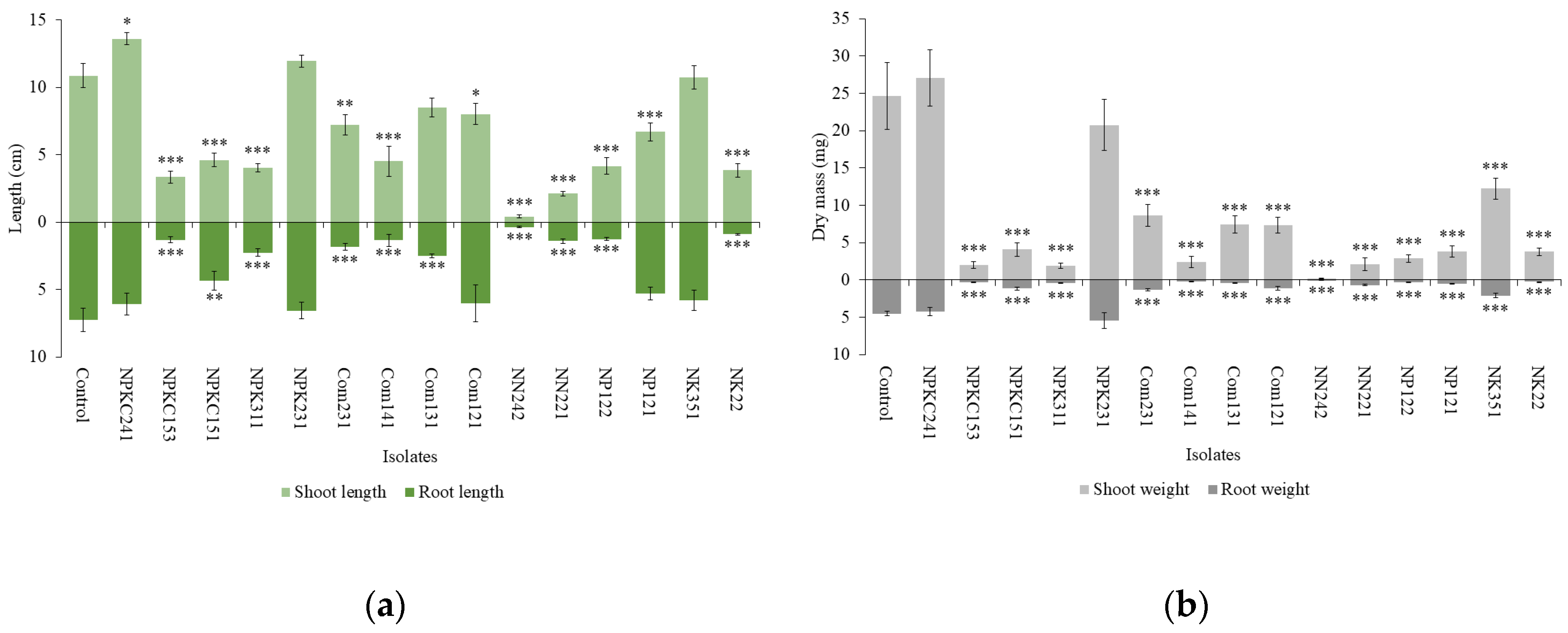

2.3. Preliminary Screening of Plant Growth Promotion

Total sixteen fungal isolates showing diverse morphologies were grown on inorganic oat meal agar (IOMA; 10 g·L⁻¹ oatmeal, 15 g·L⁻¹ Bacto agar, 1 g·L⁻¹ MgSO₄·7H₂O, 1.5 g·L⁻¹ KH₂PO₄, 1 g·L⁻¹ NaNO₃), and on ½ CMMY in 50-mm Petri dishes at room temperature.

Seeds of clover (Trifolium repens; Sakata Seed, Yokohama, Japan) were surface-sterilized by immersion in 70% ethanol for 1 min, followed by 1% sodium hypochlorite for 1 min. The seeds were then rinsed three times with SDW, dried overnight, and placed on WA in 90-mm Petri dishes. After two weeks, 3-day-old clover seedlings (two per plate) were transplanted onto each fungal colony grown on IOMA.

Seeds of the mung bean were surface-sterilized and dried, as described previously. The seeds were then placed individually on 50-mm Petri dishes containing Murashige and Skoog agar (MSA; 1 bag Murashige and Skoog plant salt mixture (Nippon Pharmaceutical Co., Japan), and 15 g·L⁻¹ Bacto agar). The plates were incubated at room temperature. After three days, the entire MSA block containing the germinated seedling was transferred onto a fungal colony grown on ½CMMY.

Clover seedlings and MSA blocks placed on non-inoculated media served as controls. All plates were placed in sterile culture pots (CB-1; As One, Osaka, Japan) and incubated in a clean room at room temperature under a 16-hour photoperiod for two weeks.

Plant symptoms were observed, and the length of shoots and roots were measured. The samples were oven-dried at 35°C until they reached a constant weight, and their dry mass was recorded for comparison with the control plants.

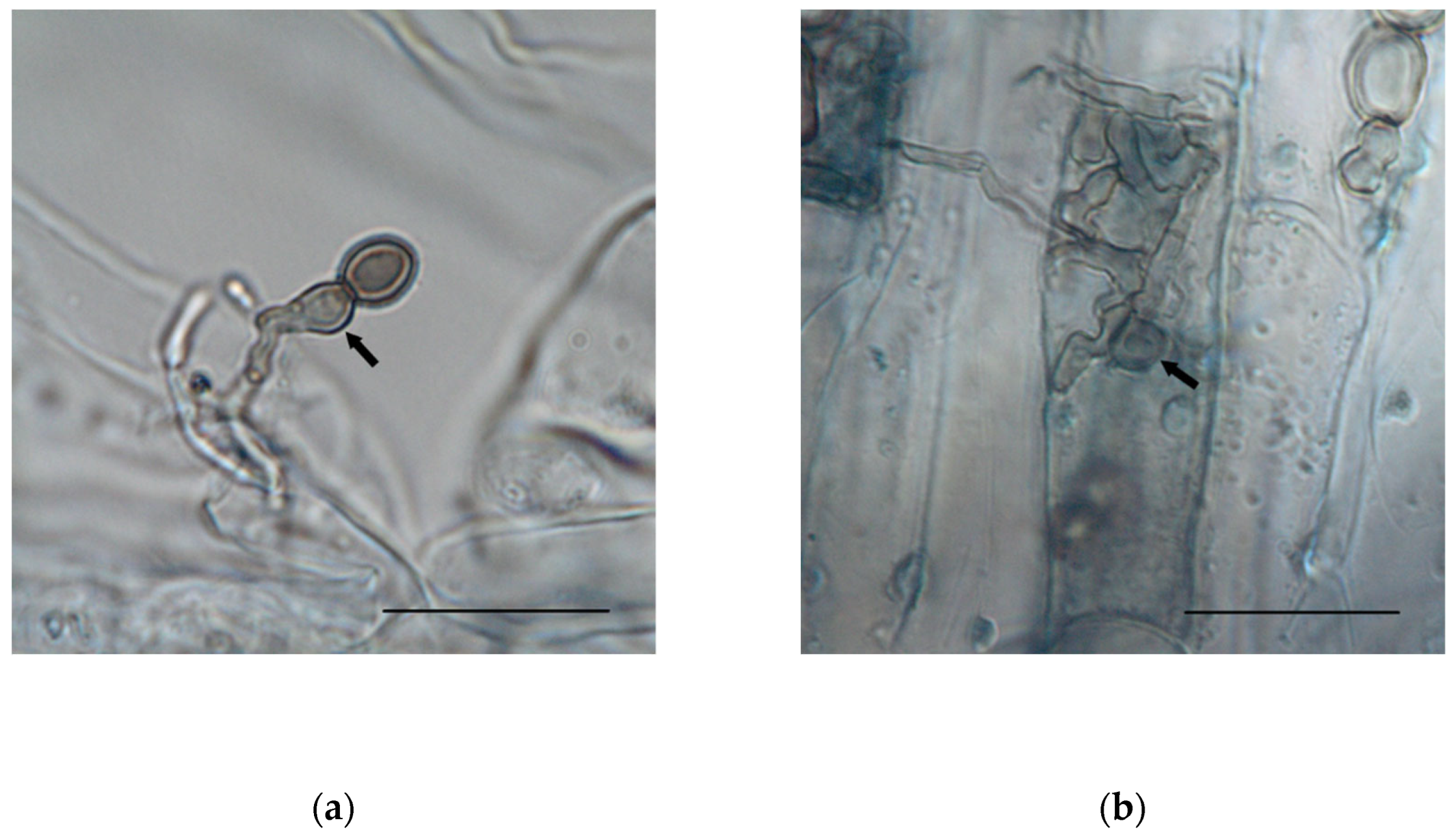

To verify the colonization of the mung bean roots by the fungal isolates, fresh root fragments from 2-week-old inoculated seedlings receiving each treatment were washed and cross-sectioned. The roots were then cleared in 10% (v/v) potassium hydroxide at 80°C for 20 min in a dry bath, acidified with 1 N hydrochloric acid at 80°C for 20 min, and subsequently stained with 0.005% cotton blue in 50% acetic acid at room temperature overnight. Observations were performed using a light microscope (BX51; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 100× magnification/1.30 oil-immersion objective.

2.4. Fungal Morphology

Microscopic morphological characteristics were examined for the identification of fungal isolates. Pure fungal cultures were grown at room temperature on 50-mm-diameter Petri dishes containing ½ CMMY. For optimal microscopic observation, slide cultures were prepared. Small agar blocks (approximately 3 × 3 mm) of IOMA and pure fungal colonies on ½ CMMY were sandwiched between two 18 × 18 mm cover glasses (Matsunami Glass Ind., Osaka, Japan) and placed on a 50-mm water agar (WA) plate to maintain humidity. After 2-4 weeks of incubation at room temperature, when the cultures had developed sufficiently, IOMA was carefully removed and the cover glasses were mounted on 76 × 26 mm microscope slides using Polyvinyl-Lactic-Glycerol mounting medium (PVLG; 16.6 g polyvinyl alcohol, 100 mL lactic acid (Wako Chemical Ind., Osaka, Japan), 10 mL glycerin (Wako Chemical Ind., Osaka, Japan), and 100 mL Milli-Q water). Mycelium and conidia were visualized using a light microscope equipped with a 100× magnification/1.30 oil-immersion objective.

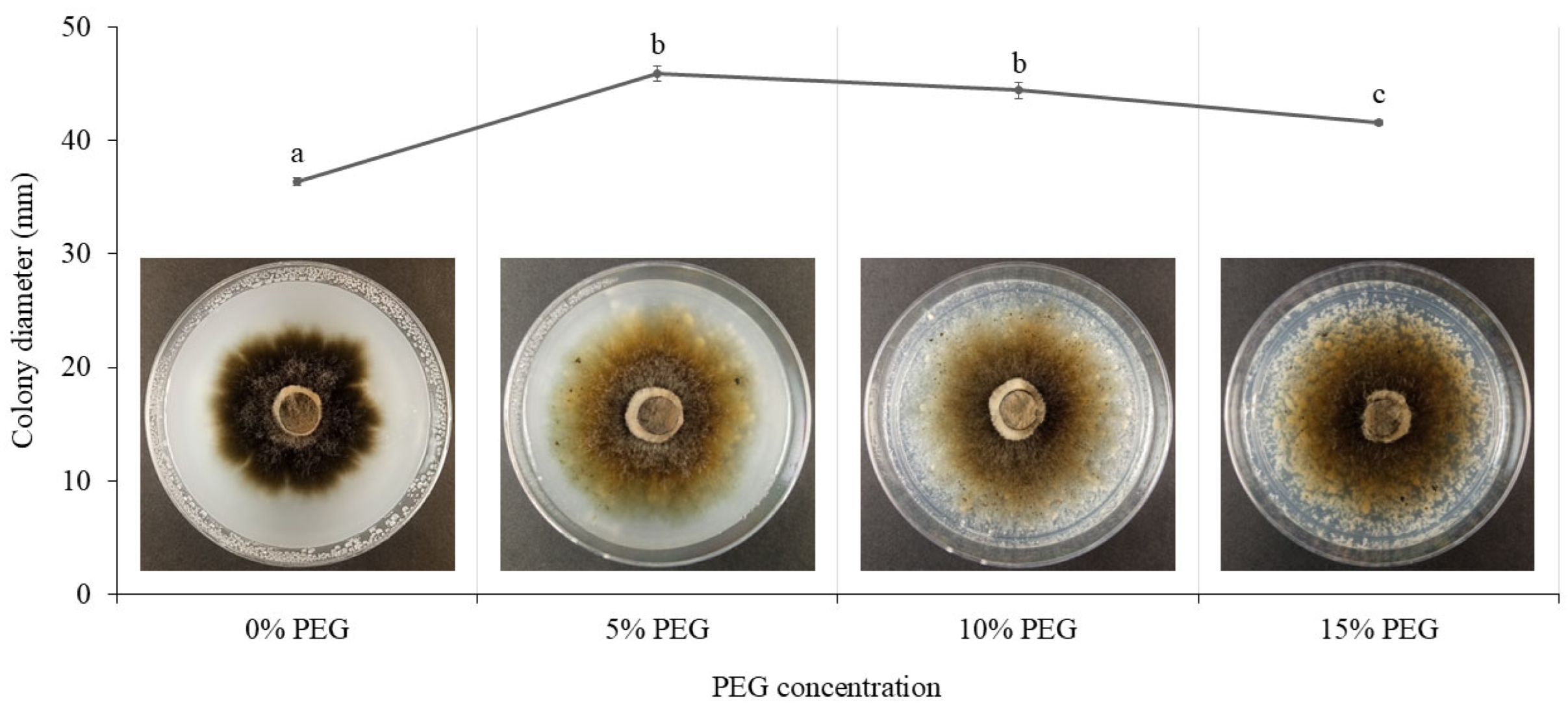

2.5. Screening of Fungal Tolerance to Drought

Pure fungal isolates cultured on ½CMMY medium were cut into 8-mm-diameter plugs using sterilized straws. The plugs were placed on IOMA medium plus four different concentrations (0, 5, 10, and 15%) of polyethylene glycol (PEG-8000; 0, 50, 100, and 150 g·L⁻¹, respectively), with three replicates for each isolate concentration for three weeks. Colony diameters were measured every seven days for three weeks.

2.6. Evaluation of Legume Vegetative Development in Soil under Drought Stress

Endophyte inoculum was prepared following the method of Innosensia et al. [

22]. A fully grown fungal isolate was cut into small pieces and transferred into a 250-mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 150 mL of 2% malt extract broth (3 g malt extract in 150 mL distilled water). The culture was incubated in a shaking incubator (Bio-Shaker BR-300LF; Taitec, Japan) at 25°C and 120 rpm for one month. After incubation, the fungal mycelia were harvested, homogenized with a sterile blender, and diluted with SDW to obtain a mycelial suspension. A total of 10 mL of each suspension was added to twice-sterilized (121°C, 30 min) endophyte substrate composed of 50 g wheat bran, 50 g rice bran, 150 g fermented leaves, and 170 mL distilled water. The inoculated substrates were incubated at room temperature for one month in sealed plastic bags.

Commercial organic seedling soil (Yuki Soil, Okayama, Japan) was sterilized twice by autoclaving at 121°C for 30 min before use. Each endophyte inoculum was mixed into the soil at 10% (w/w). The inoculated soil mixtures were transferred into 9-cm-diameter pots, and mung bean seedlings, prepared as described previously, were sown in each pot. The pots were placed in a growth chamber for four weeks under a temperature regime of 30°C during the day and 25°C at night, with a 16-h light and 8-h dark photoperiod. The control treatment consisted of twice-sterilized soil mixed with sterilized endophyte materials without fungal inoculation.

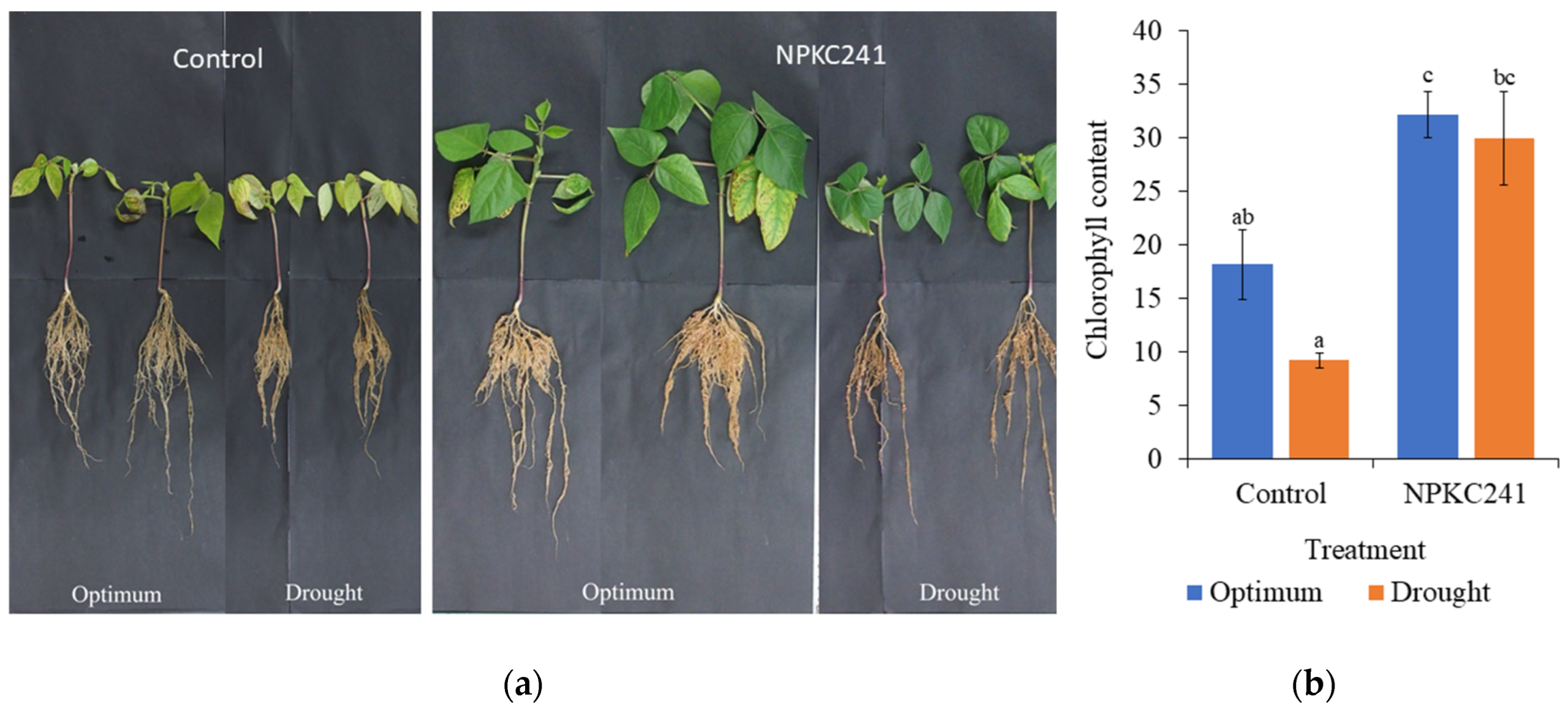

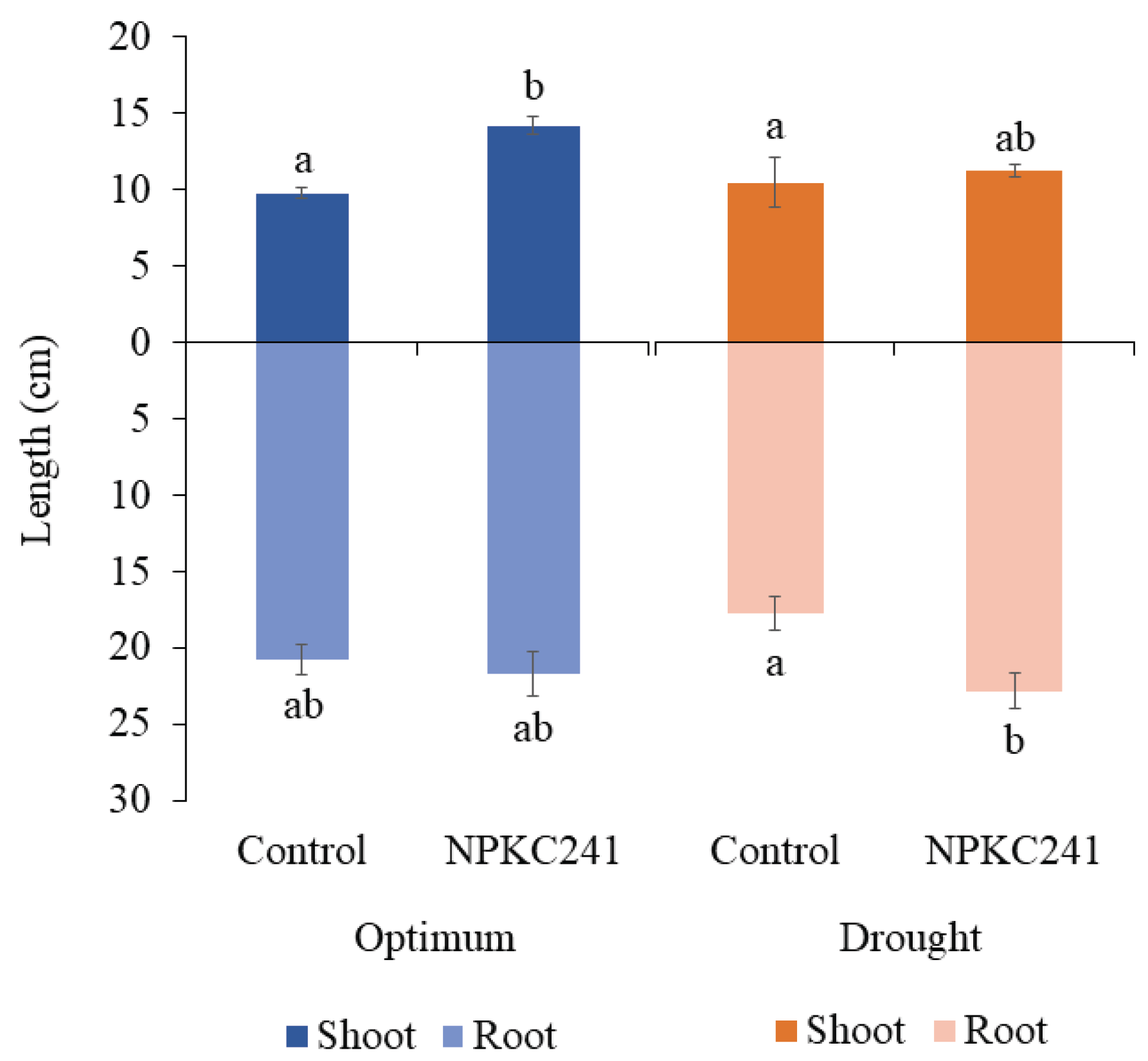

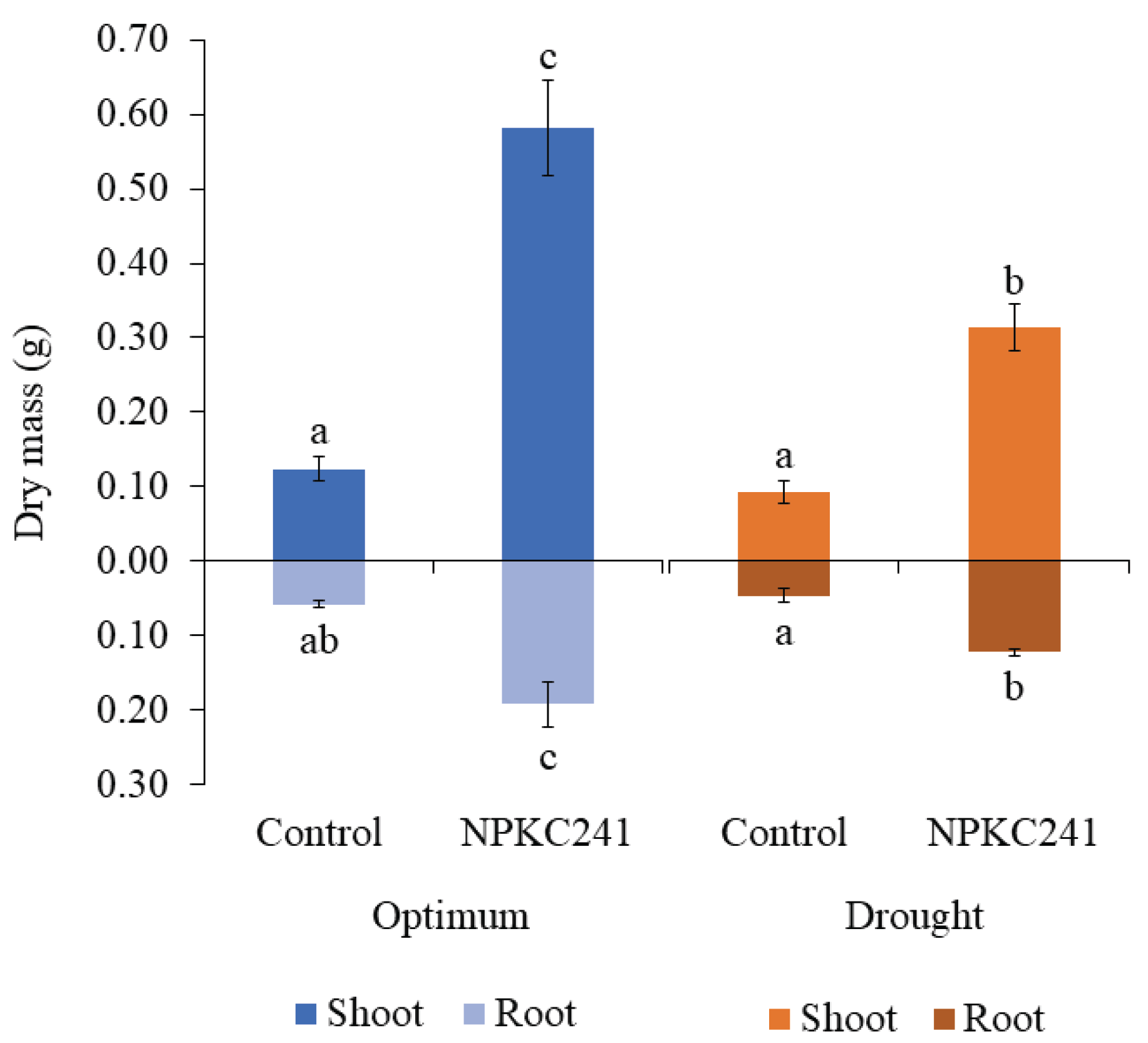

Each treatment, with five replicates, was tested under two conditions: optimal watering (60% soil water-holding capacity) and drought stress (30% soil water-holding capacity). After one month of incubation, plants were harvested, and growth parameters were recorded. Shoot dry mass and root dry mass were determined after oven-drying at 35°C until they reached a constant weight. The chlorophyll content of the first three trifoliate leaves was measured using a hand-held chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502; Minolta Camera Co., Osaka, Japan).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Raw data were compiled in Microsoft Excel. Statistical analyses were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test at a 5% significance level for the preliminary screening of plant growth promotion. Regarding the screening of fungal tolerance to drought, and the evaluation of legume vegetative development in soil under drought stress, statistical analyses were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test at a 5% significance level. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.0).

4. Discussion

A diverse assemblage of root-associated fungi was successfully isolated from mung bean roots grown in soils with six different fertilizer histories under artificial drought, except for the unfertilized soil, representing taxa from multiple orders within Ascomycota. Among the identified isolates, members of

Scolecobasidium,

Podospora,

Chaetothyriales, and

Entrophospora were predominant. These taxa are generally recognized as saprobic or facultatively endophytic fungi inhabiting soil, plant litter, and plant tissues [

23].

Interestingly,

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 was isolated from the mung bean root grown in soil amended with NPKC fertilizer. Its DNA sequence showed 100% sequence identity to

Cercophora sp. HQ631039.1. Members of this genus have typically been regarded as saprobic ascomycetes associated with soil, dung, or decaying plant litter [

15,

16]. However, the findings of Gehring et al. [

17] provide evidence that

Cercophora species may also occur as root-associated fungi. They isolated

Cercophora sp. from the root of pinyon pine (Pinus edulis E.), where it accounted for only 2% of the root-associated microbial community. The isolation of

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 from fertilized treatments suggests that nutrient-enriched conditions or the presence of organic amendments may enhance the occurrence or colonization potential of this taxon in plant roots. Its consistent recovery from the rhizosphere indicates a possible ecological shift from a purely saprobic toward a facultatively symbiotic lifestyle.

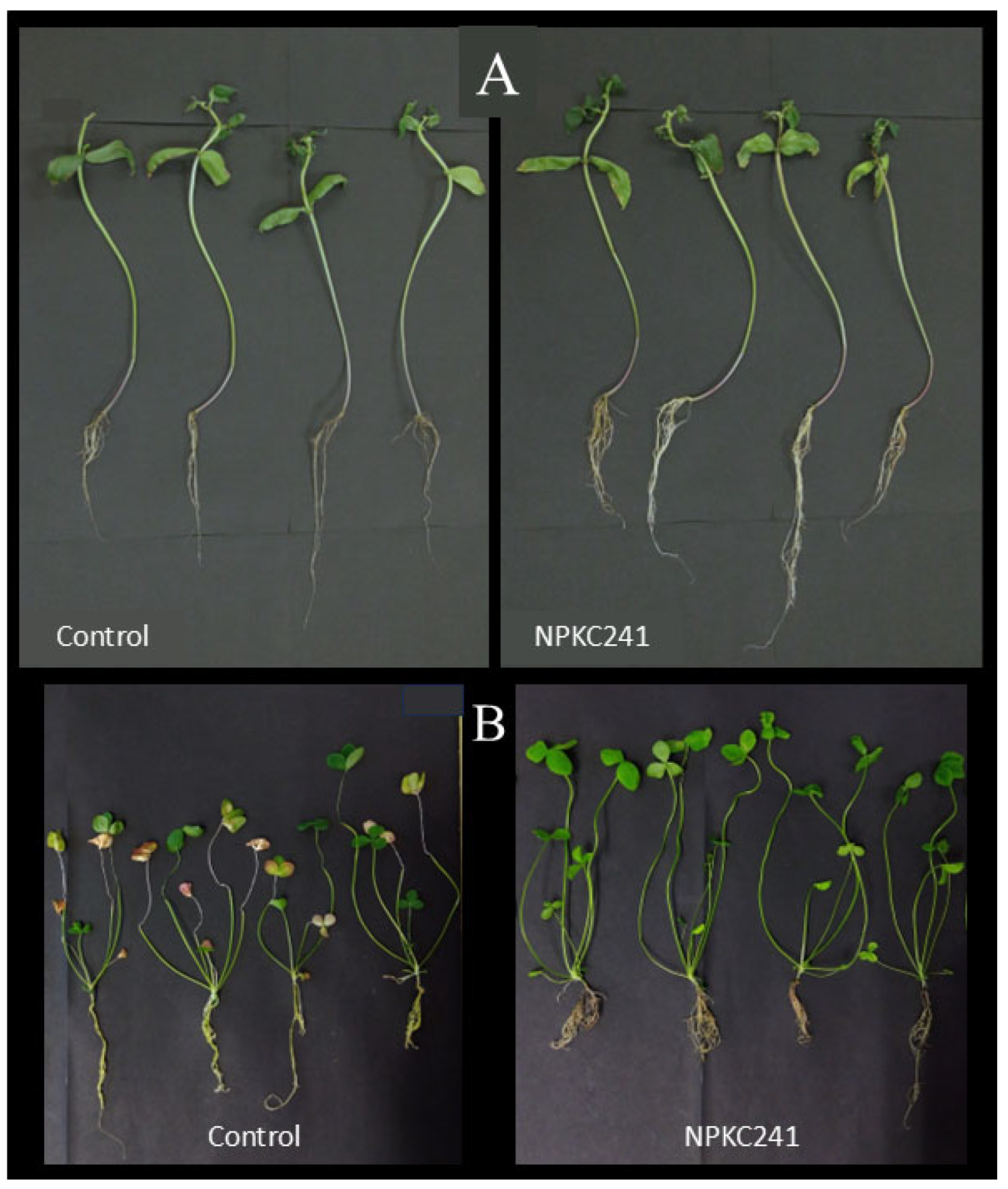

Moreover, 16 of the 29 fungal isolates were selected for preliminary potted screening experiments on the mung bean and clover plants. The screening demonstrated that several fungal isolates exhibited plant growth-promoting effects on the mung bean and clover. Among them,

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 consistently enhanced both shoot and root growth parameters in the two legumes tested. In the mung bean, plants inoculated with

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 showed greater root length and shoot and root mass values than the control, with a significant increase in the shoot dry mass. In clover, inoculation with

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 also significantly promoted shoot elongation compared with the control. These results suggest that certain root-associated fungi isolated from fertilized soils can positively influence early vegetative growth, possibly through improved nutrient uptake or the production of growth-promoting metabolites. Similar beneficial effects of DSE on host plant biomass accumulation were reported by Vergara et al. [

11], who demonstrated that DSE colonization enhances tomato acquisition of macronutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium) and micronutrients (iron, manganese, and zinc), particularly under organic nitrogen supply, thereby promoting plant growth. The observed increases in shoot and root mass and length following inoculation further indicate that these isolates may establish a compatible association with host roots. The consistent performance of

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 in the two different legume hosts suggests a broad symbiotic potential rather than host-specific interaction. Overall, these findings provide preliminary evidence that

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 may function as a beneficial root-associated fungus capable of enhancing legume growth. It was selected for further morphological characterization and inoculation experiments to evaluate its potential endophytic role in promoting plant growth under drought stress.

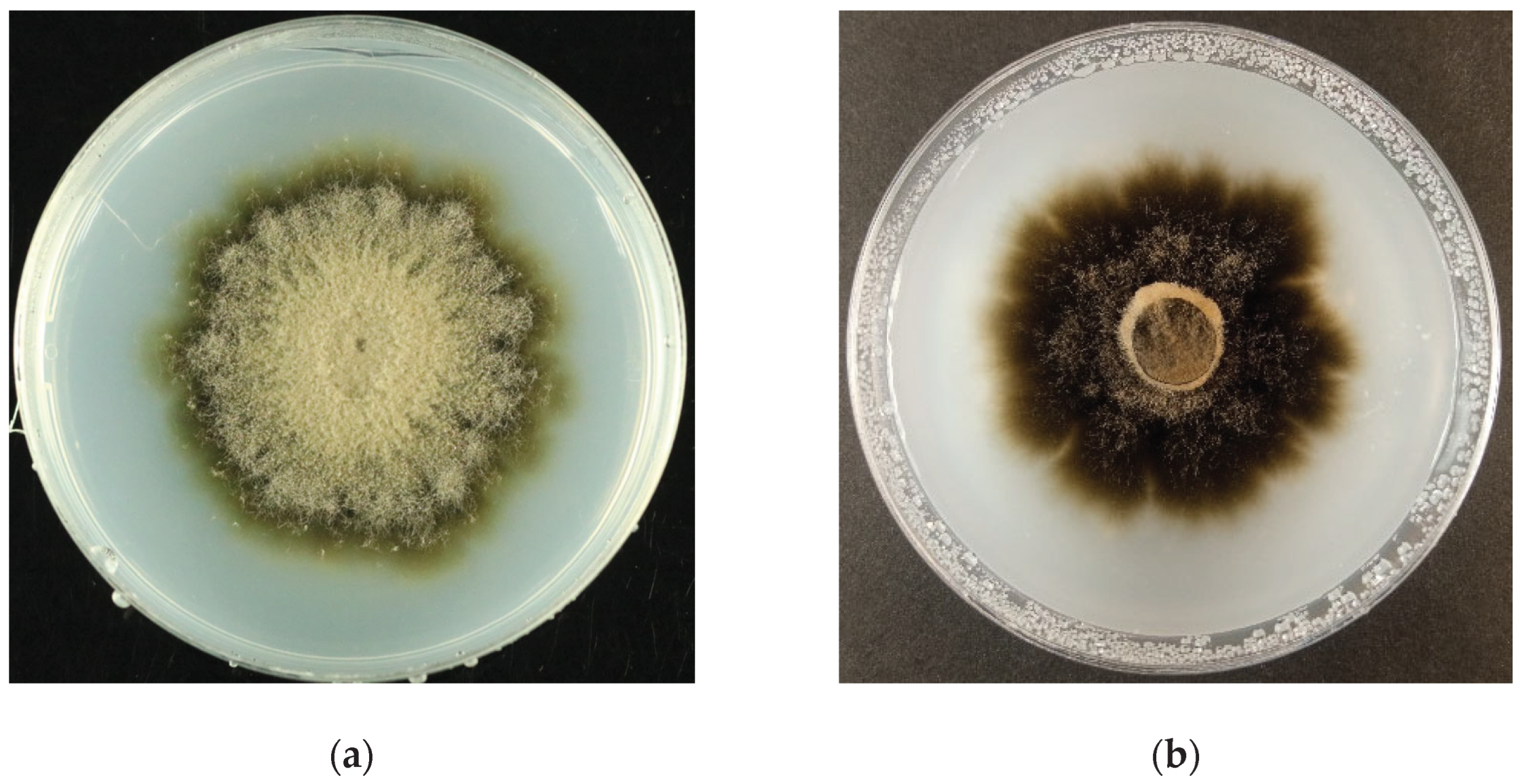

The present study demonstrated that

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 exhibited distinct morphological and physiological characteristics associated with DSE. The colony morphology varied across media, with dark, velvety pigmentation on IOMA and floccose brown aerial mycelia on ½CMMY, indicating phenotypic plasticity in response to the nutrient composition. The colony growth was slow, being 36.38 ± 0.35 mm after 21 days on IOMA at room temperature. Microscopic observation revealed septate, hyaline hyphae with melanized cell walls, and intercalary, oval conidiogenous cells producing blastic conidia-features typical of ascomycetous endophytes. These characteristics closely resemble those described for

Cercophora rugulosa,

C. striata, and

C. atropurpurea by Miller and Huhndorf [

14]. All three

Cercophora species possess typical ascomycetous hyphal structures characterized by pigmented, septate, and interwoven hyphae forming the perithecial wall or subiculum-features comparable to the dark, septate hyphae commonly observed in DSE.

C. rugulosa and

C. striata were also reported as slow-growing fungi, producing colonies of approximately 21-39 mm in diameter on nutrient-poor substrates (WA, corn meal agar, and oatmeal agar) after 21 days. Furthermore,

C. atropurpurea and

C. striata exhibit phialidic conidiation with conspicuous collarettes;

C. atropurpurea additionally produces large blastoconidia directly from hyphae, while

C. striata forms clustered phialides with short, flared necks and sclerotium-like structures. These asexual morphs closely resemble

Phialophora-type anamorphs, which are typical of many DSE lineages.

In a previous study,

Cercophora palmicola [

16], collected from decaying palm wood, produced hyphae that penetrated bark tissues without degrading host cell walls, indicating a non-destructive mode of colonization even on decomposing substrates. In the present research, the presence of microsclerotia structures within the root cortex of the mung bean without causing visible necrosis confirmed an endophytic rather than pathogenic association, consistent with previous reports on DSE promoting host plant [

7,

9]. These findings collectively support the notion that certain

Cercophora species, including

Cercophora sp. NPKC241, may adopt an endophytic or weakly saprobic lifestyle, maintaining structural integrity of host tissues while establishing stable associations similar to those described for DSE fungi.

The PEG-induced osmotic stress test further revealed that

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 tolerated moderate drought conditions, with colony growth stimulated at 5-10% PEG and only slightly inhibited at 15%. Such tolerance suggests that the fungus can maintain metabolic activity under conditions with a low water potential, a key trait promoting its survival in drought-affected soils. In addition, chitin and melanin, present in dark hyphae, may reinforce the cell wall structure and provide protection against various environmental stresses, including drought, heat, salinity, heavy metals, and radiation [

13,

24]. According to Gaber et al. [

24], the ability of root endophytes to tolerate stress is essential for establishing effective symbiotic relationships with plants under adverse conditions, suggesting that fungi adapted to harsh environments are more capable of enhancing plant tolerance to abiotic stress than those originating from non-stressed habitats. Similar adaptive responses have been documented in other DSE, such as

Periconia macrospinosa, which possesses melanized cell walls that confer protection against salinity [

25]. Overall, the morphological and physiological attributes of

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 indicate its potential role as a drought-tolerant endophyte capable of establishing mutualistic interactions with legumes under water-deficient conditions.

The inoculation of the mung bean plants with

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 markedly enhanced growth performance under both optimal and drought conditions, indicating its potential as a beneficial root-associated fungus. The significant increases in shoot and root dry mass, particularly the fivefold rise in shoot dry mass under optimal conditions, suggest that

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 may enhance nutrient uptake efficiency or modulate plant growth through the production of bioactive metabolites such as auxins and gibberellins, as reported for other DSE species. Similarly, the findings of Innosensia et al. [

22] demonstrated that two DSE:

Cladophialophora chaetospira SK51 and

Veronaeopsis simplex Y34, promoted soybean growth by increasing the number of fully expanded trifoliate leaves, nodules, and total biomass. Similar host growth enhancement was observed in studies of

Scolecobasidium humicola [

23] and

Periconia macrospinosa [

25], both of which are DSE taxa known to improve plant vigor under organic nitrogen source or stressful conditions.

Under drought stress,

Cercophora sp. NPKC241-treated plants maintained markedly higher shoot and root dry mass values compared with the control, despite an overall reduction relative to optimal conditions. This indicates that

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 inoculation enhanced drought tolerance, possibly by improving water-use efficiency or promoting root system development, thereby enabling plants to access deeper soil moisture. Similar drought-mitigation effects have been reported for DSE taxa such as

Cadophora sp., which alleviate the negative impacts of water limitation by promoting root elongation and osmotic adjustment [

26].

The maintenance of a high chlorophyll content in

Cercophora sp. NPKC241-treated plants under drought stress further supports the hypothesis that

Cercophora sp. enhances photosynthetic stability under water-limited conditions. In non-inoculated plants, the chlorophyll content declined by approximately half under drought, whereas inoculated plants retained nearly unchanged chlorophyll levels. This pattern suggests that

Cercophora sp. NPKC241 may help sustain the photosynthetic apparatus, either by mitigating oxidative stress or maintaining nutrient balance, as reported in other DSE-host systems [

27]. Preservation of the chlorophyll content is widely recognized as a key physiological indicator of drought resilience, reflecting the fungus’s role in reducing stress-induced senescence and maintaining the carbon-assimilating capacity.

Taken together, these results provide strong preliminary evidence that Cercophora sp. NPKC241 may function analogously to DSE, promoting both growth and drought tolerance in legumes. The combination of enhanced root development, mass accumulation, and sustained chlorophyll content suggests a multifunctional symbiotic relationship that benefits the host under fluctuating environmental conditions. Future studies focusing on physiological responses will be essential to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of this association, and confirm whether Cercophora sp. NPKC241 represents a novel endophytic lineage within the DSE functional group.