1. Introduction

Chrysanthemum morifolium, which belongs to the genus

Chrysanthemum, is one of the oldest ornamental and medicinal flowers, and is the second-largest cut flower in the world [

1]. It was first cultivated in China and is loved by people all over the world due to its attractive colors and shapes. In recent years, increasing demand for cut chrysanthemum has led to an increase in chrysanthemum cultivation areas, and monocropping is usually the most effective method for maximizing economic benefits. However, during long periods of cultivation, chrysanthemum in continuous cropping areas showed yellowing and wilting leaves, stunted growth, and sharp yield declines. As the cropping time increased, diseases raged, resulting in complete failure of harvest in some areas, which seriously affected the economic income of growers and caused huge economic losses [

2]. It is believed that soil microorganisms, specifically soil-borne pathogens, are a major cause of this decline in productivity [

3].

Rhizospheres represent dynamic soil regions that are regulated by intricate interactions between plants and organisms closely associated with roots. These regions are characterized by a high abundance of microorganisms, often referred to as the second genome of plants, which play a crucial role in promoting plant health and enhancing crop yield. These microorganisms significantly influence mineral element availability, carbon and nitrogen cycling, as well as the development of soil structure [

4,

5,

6]. The practice of long-term continuous cropping has been observed to have a profound impact on the structure of soil microbial communities, leading to the emergence of soil-borne diseases and a decline in crop yield. In typical soil conditions, certain native microorganisms possess the ability to suppress the growth of pathogens. However, in conducive soil environments, pathogens are able to rapidly invade and proliferate, consequently diminishing the presence of beneficial bacteria. Research conducted on the continuous cropping of

Rehmannia glutinosa has revealed significant alterations in the abundance of bacteria and fungi within the rhizosphere soil, disrupting the delicate equilibrium between beneficial and pathogenic microorganisms [

7].

The

Fusarium genus encompasses several economically significant plant pathogenic species that induce wilt disease in various plants [

8], including vegetables, grasses, fruit trees, and flowers. The majority of research efforts have predominantly concentrated on

F. oxysporum, the primary causative agent of fusarium wilt on a global scale [

9]. This fungal disease poses a substantial threat to crop production, inflicting severe economic losses, particularly in regions characterized by elevated temperatures and humidity levels. The growth of the plant infected with the pathogen in the early stage is comparatively sluggish in comparison to a healthy plant, as the disease symptoms begin to appear from the lower leaves. Subsequently, the leaves curl and yellow from the bottom to the top, ultimately resulting in the complete withering and demise of the entire plant. Additionally, other species within the

Fusarium genus, such as

F. solani,

F. incarnatum, and

F. falciforme [

10], have also been identified as pathogens for Chrysanthemum. Wilt disease in chrysanthemum has been reported globally, including in regions such as northern India, South Korea, Italy, the Netherlands, and Japan [

11]. The frequency of fusarium wilt also outbreaks in various chrysanthemum production areas in China, such as Zhejiang, Fujian, Hebei, and Nanjing, has progressively emerged as a primary constraint on the advancement of the local chrysanthemum industry.

In order to better study the soil microbial community structure, the advent of third generation sequencing technology in recent years, specifically PacBioSMRT sequencing, has a significant impact on the disciplines of genomics and microbiology [

12]. This technology has successfully addressed the limitations of conventional culture methods in identifying microorganisms that are challenging to cultivate or have become inactivated. By enabling a comprehensive exploration of the microflora’s composition in various environments, PacBio sequencing offers a novel and efficient approach to investigating microbial community structure, thereby facilitating substantial advancements in the field of microbial research. The study conducted by Pootakham et al. [

13] employed full-length ITS and 16S rRNA genes to categorize and examine the symbiotic algae family and bacterial communities present in Indo-Pacific corals located in the Gulf of Thailand. The findings indicated that environmental factors exerted an influence on both the composition of plant structures and the diversity of bacterial communities associated with corals. Furthermore, the study demonstrated the efficacy of PacBioSMAT sequencing in accurately classifying coral-related microbiota at the species level.

Limited research has been conducted on a comprehensive investigation into the factors that contribute to the occurrence of chrysanthemum continuous cropping wilt. Studies pertaining to pathogen infection in chrysanthemum often adopt a descriptive approach, primarily examining pathogen species within host populations, rather than delving into the underlying mechanisms that drive these interactions. So, our study was primarily to isolate and purify the pathogen that may be associated with Fusarium wilt from the rhizosphere soil in cultivar ‘Guangyu’. Additionally, examine the invasion pattern of the pathogen and assess the physiological response of chrysanthemum plants to stress induced by the pathogen. Finally, the PacBio platform was utilized to analyze complete 16S rRNA and ITS sequences to investigate the attributes of microbial communities in the rhizosphere of the soil from the local cut chrysanthemum that has been subjected to continuous cropping for a duration of 7 years, as well as the soil from the initial cropping. The aim of the aforementioned study is to offer a comprehensive comprehension of the potential mechanisms that underlie wilt disease in the ‘Guangyu’ cultivar. Consequently, these findings will contribute to the establishment of a vital theoretical basis for the sustainable advancement of diverse crop varieties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field investigation and Soil samples collection

The study conducted a field investigation on Fusarium wilt in a cut chrysanthemum planting base located in Xinxiang, Henan province, China (35°24′ N, 114°55′ E). The continuous cropping field and healthy field of chrysanthemum were divided into five districts, from which 20 chrysanthemum samples were randomly selected. The height and leaf width of each plant were measured. Furthermore, several chrysanthemum samples exhibiting severe disease symptoms were randomly selected from each district, and their root and stem characteristics were observed compared with those of healthy plants. Simultaneously, samples of rhizosphere soil were collected and analyzed from 7 years continuous cropping and a first-year cropping fields. A multi-point sampling method was employed to select five sampling points in each field, and the collected samples were subsequently merged. The samples were promptly placed into sterile bags, transported to the laboratory under low temperature conditions, and stored at -80 °C.

2.2. Isolation and identification of the pathogen

Using the dilution-plate method, the fungi were isolated from soil samples collected from a Fusarium wilt field. The strains were isolated and purified by singlespore isolation, which were then inoculated into PDA solid medium and incubated at a temperature of 30 ℃ for a period of 3-7 days [

14]. Once the hyphae were fully covered on a 90 mm plate, the colony morphology, color, texture, and growth rate were carefully observed and recorded. The purified fungi were subsequently cultured in PDA for 7 days, and the surface conidia were washed with aseptic water, filtered using 4 layers of lens paper, and finally, 20 μL of the filtered solution was placed under a light microscope (NikonHFX-IIA, Japan) to observe the morphology of the conidia.

The fungal genomic DNA was extracted from fresh fungal cultures following the methodology described by Al-Sadi et al. [

15]. The rDNA-ITS region was amplified using the universal primers ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) as outlined by White et al. [

16]. Subsequently, the amplified DNA fragments were purified and ligated into the pMD19-T vector. The resulting constructs were then submitted to Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai) for sequencing. The obtained sequencing results were compared and analyzed using Blast against the NCBI database (

http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using Clustal X v1.83 software [

17] and MEGA 4.0 [

18].

2.3. Pathogenicity test

The healthy chrysanthemum cultivar ‘Guangyu’ was selected from a chrysanthemum field, following three generations of consecutive cutting and transplanting in an indoor environment. The plants that remained asymptomatic were chosen as the inoculated hosts. The uppermost 10-15 cm of these plants were trimmed and immersed in rooting fluid for 30 min, before being transplanted into flowerpots (a diameter of 7 cm and a height of 10 cm) filled with sterile vermiculite. Subsequently, following a rooting period of 15-20 days, the plants were relocated to flowerpots containing sterile nutrient soil and vermiculite in a ratio of 2:1 (with a flowerpot diameter of 16 cm and height of 14 cm). Following an additional 1-2 weeks of cultivation under controlled conditions in a illuminating incubator (at a temperature of 30 °C, with a photoperiod of 14 h of light and 10 h of darkness), the treated plants were utilized as the subsequent experimental hosts.

To determine which specie of

Fusarium are responsible for inducing plant disease, the root-drenching method described by Getha et al. [

19] was employed. In the treatment group, each plant was subjected to a fungal spore suspension of 20 mL at a concentration of 10

6/mL. Conversely, the control group was treated with sterile water. The treated plants were then placed in the illuminating incubator and cultured at a temperature of 30 ℃, following a 14 h light and 10 h dark cycle. The plants were observed until the appearance of disease spots. Subsequently, diseased stem tissue was collected, and the pathogen was isolated and purified from the tissue. Finally, the isolated fungal specimen was compared with the inoculated pathogen to determine whether it was the causative agent of chrysanthemum wilt.

2.4. Observation of colonization process and disease assessment

The root-dipping method was employed to investigate the pathway of pathogen invasion. Initially, chrysanthemum seedlings were subjected to a 30 min wash under running water, followed by rinsing with aseptic water. Subsequently, they were immersed in 75% alcohol for a duration of 10-15 s and rinsed with sterile water three times. The roots were then incised using sterilized scissors. The treatment group was immersed in the prepared spore solution for 30 min, while the control group was immersed in aseptic water for the same time. The chrysanthemums were subsequently removed and transplanted into flowerpots containing sterilized soil. Following the watering process, the flowerpots were subsequently relocated to an incubator with specific conditions, including a temperature of 30 ℃, a photoperiod of 14 h, and a dark cycle of 10 h. The morbidity and mortality rates of chrysanthemums were then diligently monitored and documented every 10 days. The disease index (DI) was determined by carefully observing the progression of symptoms such as leaf yellowing, wilting, and plant demise. To establish a classification system for Fusarium wilt, a grading scale ranging from 0-4 was adopted, referring to Alkher et al. [

20]. Grade 0 signified the absence of symptoms in the leaf, grade 1 denoted the presence of a single leaf exhibiting yellowing or curling at the basal region <30%, grade 2 signified the yellowing, curling, or wilting of approximately 30% to 50% of the entire plant’s leaves, accompanied by a slight reduction in plant height, grade 3 indicated the yellowing, curling, or wilting of approximately 50% to 75% of the plant’s leaves, resulting in leaf abscission, grade 4 signified the 75% to 100% yellowing, curling, or wilting of all leaves on the plant, or the demise of the plant. The disease grade for each plant was documented at 10 and 20 days post-inoculation (dpi), and subsequently, the disease index was computed using the following formula: disease index = Σ (number of diseased leaves at each grade × the corresponding grade) / (total number of leaves examined × highest grade).

The root tissues of chrysanthemum were collected at specific time intervals (12 h, 5 day, 10 day, 15 day, 20 day) and subjected to a 30 min washing procedure with running water to thoroughly remove any soil adhered to the root surface. For each period, 20 fresh root segments were carefully selected and prepared for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) according to the method described by Boamah et al. [

21]. Simultaneously, the root samples were subjected to WGA-AF488&PI co-staining, and observed by laser confocal scanning microscopy (LCSM) to observe the colonization of pathogens in the root system [

22].

2.5. Plant cell wall degrading enzyme (CWDE) activity of pathogen

The enzymatic activity responsible for degrading the cell wall of plants by the pathogen was assessed using the 3, 5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method [

23], specifically measuring the activities of cellulase (CX), β-glucosidase (βG), pectin methylgalactuionase (PMG), polygalacturonase (PG), and xylanase.

2.6. Physiological response of plants after infection by pathogen

The concentrations of photosynthetic pigment including carotenoid and chlorophyll (chla, chlb), soluble sugar, and soluble protein in plants were quantified using spectrophotometry [

24], anthrone colorimetry [

25], and the Coomassie bright blue method [

26], respectively. The levels of ash content, potassium (K), phosphorus (P), and calcium (Ca) in leaves were measured using Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) [

27].

The content of H2O2 was determined as follows: 0.1 g of sample tissue was weighed, and subsequently mixed with 0.9 mL of normal saline. The resulting mixture was then subjected to quick-freezing and grinding in liquid nitrogen, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant obtained from this process was utilized for testing purposes and measured the absorbance at 405 nm. The activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD) and malondialdehyde (MDA) were determined using Kits (Grace Biotechnology, Suzhou, China) according to instructions. The activity of polyphenol oxidase (PPO), phenylalanine ammonialyase (PAL), and Chitinase (CHI) was determined using the Polyphenol Oxidase Kit, Phenylalanine Ammonialyase Kit, and Chitinase Kit (Nanjing JianCheng Bioengineering Institute, China) based on the manufacturer’s protocols.

The content of (Salicylic acid) SA and (Jasmonic acid) JA in the supernatant was measured using the Plant Jasmonic acid elisa kit and Plant Salicylic acid elisa Kit, respectively, following the provided instructions (Quanzhou Ruixin Biological Technology Co., LTD Quanzhou, China).

2.7. Soil DNA extraction and microbiome profiling

The soil samples from mixed continuous cropping were subjected to parallel sequencing and labeled as LZ1861a-a, LZ1861a-b, and LZ1861a-c, while the healthy soil samples were labeled as XT1861a-a, XT1861a-b, and XT1861a-c. The DNA extraction process for fungi and bacteria in each soil sample followed the standard protocol of the OMEGA DNA isolation kit (Omega, USA). The quality of the extracted DNA was assessed for degradation and contamination using 1% agarose gels. The purity of DNA was assessed using a NanoDrop™ One UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), with an OD260/280 ratio ranging from 1.8 to 2.0 and an OD260/230 ratio between 2.0-2.2. Subsequently, the DNA concentration was determined using a Qubit® 4.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, USA). Amplification of the full length of the 16s rRNA gene was achieved using the forward 27F primer (5′-GAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and reverse 1541R primer (5′-AAGGAGGTGATCCAGCCGCA-3′). The ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) primers were used to amplify the full length ITS rRNA gene. Following purification, the amplified product was submitted to Grandomics Co., Ltd. (Wuhan) for DNA sequencing using the PacBio RS II sequencer.

2.8. Bioinformatic analysis

The initial dataset was partitioned based on barcode information using SMRT Portal v2.3.0, resulting in the acquisition of high-quality CCS (Circular Consensus Sequencing) sequences. Subsequently, the split sequences underwent filtration to eliminate extraneous data, including fragments outside the length range of 1400-1600 bp, reads containing “N” bases, reads containing homopolymers exceeding 6 base pairs, and sequences with an average mass below 90. The resulting set of filtered high-quality data was subjected to removal using Usearch software (v10) and subsequently clustered using OTU (Operational Taxonomic Units) methodology. The representative sequences of OTU at a 97% similarity level were subjected to classification and analysis using the uclust algorithm. The species present in each sample were classified and quantified at various taxonomic levels, including boundary, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. The relative abundance of species at the gate and genus levels was visualized using R software. Bacterial and fungal communities were compared against the Silva (v138.1) and Unite (v8.2) databases, respectively. The α diversity, β diversity, and species differences among the samples were assessed using the Qiime software and R language.

2.9. Statistical analytical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using Excel 2016 and GraphPad Prism (v 8.0.2) for Windows. The data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean and assessed through two-way ANOVA of the three biological replicates, followed by the least significant difference test. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

This study primarily concentrated on the chrysanthemum cultivar “Guangyu,” which had experienced significant susceptibility to wilt disease as a result of prolonged consecutive cultivation. Initially, the research involved the isolation and identification of the Fusarium wilt pathogens, followed by the assessment of their pathogenicity and exploration of the infection pathway. Subsequently, the investigation delved into the physiological and biochemical responses of the infected chrysanthemum. Lastly, the study analyzed the changes in the microbial community composition within the soil subjected to continuous cultivation.

Various pathogens, including

F. incarnatum,

Dickeya chrysanthemi,

Rhizoctonia solani,

Erwinia chrysanthemi, and

F. oxysporum, have been identified as potential causes of wilt on Chrysanthemum [

28]. Through pathogenicity detection and verification, the results in this research demonstrated that

F. solani displayed pathogenicity, with pathogenic characteristics consistent with those observed in the natural field. Therefore, it was recognized as the primary pathogen accountable for chrysanthemum wilt in the ‘Guangyu’ cultivar. The strain’s capacity to produce cellulase, β-glucosidase, polygalacturonase, pectin methylgalacturonidase, and xylanase which facilitated fungal penetration of the plant cell wall. Furthermore, it was observed that the infection induced by this pathogen exerted a substantial inhibitory effect on the growth and metabolic activities of the afflicted plants. Soluble proteins and sugars had proven to be valuable indicators for evaluating the physiological metabolism of plant cells. The presence of pathogen infection could trigger the defense response in plants, resulting in the production of pathogenesis-related proteins. Sugars played a crucial role in the material and energy metabolism of plants, as an increase in soluble sugar levels facilitated the maintenance of cell osmotic pressure, augmentation of metabolic capabilities, and adaptation to stressful conditions. The findings of this study indicated that the infection of chrysanthemum by

F.solani resulted in a significant increase in the levels of soluble protein and soluble sugar in the leaves, which could play a crucial role in preserving the integrity of the plant cell membrane structure and enhancing the plant’s resistance against diseases. However, as the invasion prolonged, the plant’s autoimmune response became insufficient to counteract the pathogens, leading to a decline in its physiological indices and eventual death.

Pathogen-induced infection in plants could result in the occurrence of oxidative outbreak, characterized by the rapid and instantaneous generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

29]. The excessive accumulation of ROS triggered an oxidative stress response in plants, leading to detrimental effects on nucleic acids, proteins, lipids, and other macromolecules, ultimately disrupting cellular function [

30]. To counteract the oxidative damage caused by the excessive ROS accumulation, plants had developed various coping mechanisms. An effective approach to detoxification involved enhancing the activity of antioxidant enzymes in order to safeguard plants [

31]. Within plants, the key antioxidant enzymes including SOD, CAT, POD, which served as a strategy to combat pathogen invasion [

32]. SOD, functioning as the primary defense against oxidation, was a vital protective enzyme in plant tissues, primarily engaged in oxygen metabolism and contributing significantly to the investigation of plant disease resistance mechanisms [

33]. Previous research had demonstrated that disease-resistant varieties exhibited significantly higher SOD activity compared to susceptible varieties following infection by

F. trichothecioide [

34]. CAT, an essential protective enzyme in plant tissues, played a crucial role in breaking down the accumulated H

2O

2 resulting from plant metabolism, thereby reducing oxidative damage to cells. POD, apart from its role as a prominent component of the antioxidant enzyme system, it also played a crucial role in facilitating the synthesis of lignin, thereby promoting the process of lignification in affected tissues. Additionally, it acted as a catalyst for the production of phenols that possessed toxicity towards pathogens, effectively inhibiting their proliferation and expansion within the host organism. The antioxidant enzymes in plants consistently maintained a dynamic equilibrium with ROS, thereby regulating cellular levels of free radicals to a normal range. In this study, the activities of CAT and POD in the early stage of infection showed an upward trend, while the contents of ROS and free radicals did not change significantly, indicating that the outbreak of ROS activated the antioxidant system response in plants. With the prolonged duration of infection, the activities of CAT and POD exhibited a decline, while the concentration of H

2O

2 showed an accumulation, and the levels of MDA significantly increased. These observations indicated a substantial accumulation of ROS within plants, intensifying peroxidation and exacerbating cellular damage. This accumulation surpassed the regulatory limits of plant autoimmunity, leading to metabolic disturbances and disruption of normal physiological structure and function. Consequently, this process accelerates the senescence and demise of plant leaves.

During the course of pathogen infection, plants could also augment the activity of defense enzymes to mitigatie the accumulation of detrimental substances and bolstered own resistance [

35]. Notably, defense enzymes such as PAL, PPO and CHI [

36], were instrumental in the synthesis of lignin and phenolic compounds, which served as barriers against pathogen invasion and mitigated the toxic substances [

37,

38]. Additionally, these enzymes could directly contribute to enhance disease resistance by generating quinone substances that impeded the growth and expansion of fungal hyphae. PAL was a crucial enzyme in the phenylpropane metabolic pathway in plants, and its activity served as a dependable indicator for evaluating the disease resistance of host plants. PPO could reinforced plant disease resistance through its involvement in the synthesis of lignin precursors and the oxidation of phenolic substances in plants. CHI encoded a protein associated with disease progression, capable of degrading the cell wall of pathogen and playing a significant role in plant defense mechanisms. During the initial phases of the disease, plants exhibited an augmented resistance mechanism through the reinforcement of enzymatic activity of PAL, PPO and CHI to combat the pathogenic agents. Nevertheless, as the disease progressed, the continuous accumulation of toxins in plants became relentless. Consequently, the innate resistance of the plants proved inadequate to counterbalance the hazardous substances imposed by the pathogen, ultimately resulting in the withering and demise of the plants.

The phytohormones salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) were significant mediators of plant immunity against pathogens, with SA and JA signaling playing crucial roles in defending against both biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens [

39]. Recent investigations had shed light on the pivotal function of SA in impeding biotrophic infections, as they have unraveled the biosynthesis and signaling pathways linked to the modification of pathogen susceptibility [

40]. The results of our study suggested that pathogen infection may trigger the activation of the SA defense pathway. However, additional research was needed to determine the extent of the involvement of the JA pathway in the defense response against Fusarium wilt in chrysanthemum.

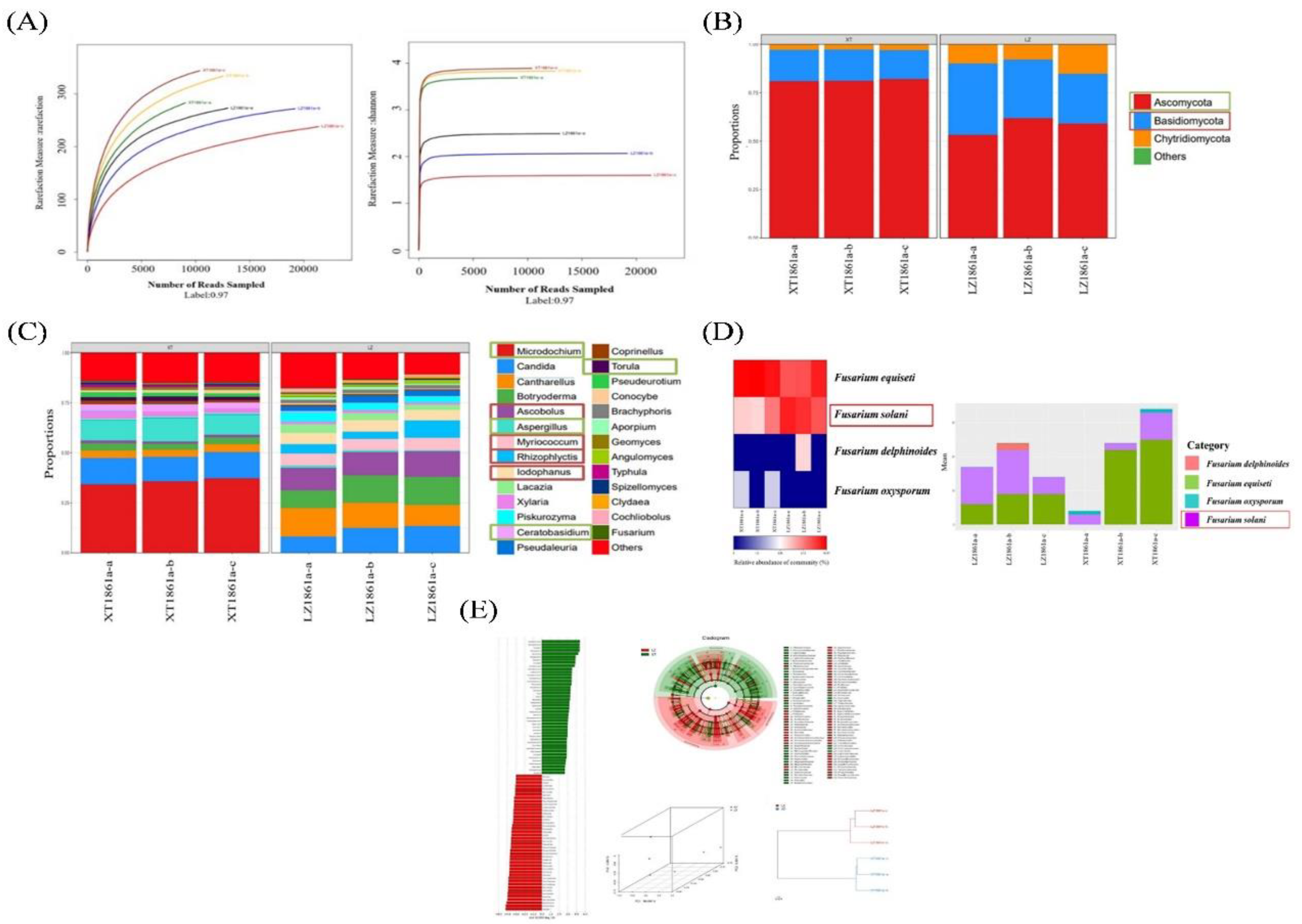

The soil environment was a multifaceted ecosystem, wherein the composition, diversity, and function of the soil microbial community were influenced by various factors such as climate, cultivation techniques, soil nutrient levels, introduction of foreign pathogens, and agricultural management practices. The soil microbial community played a crucial role in suppressing soil-borne diseases through mechanisms such as promoting the synthesis of plant hormones, competing with soil-borne pathogens for essential nutrients, engaging in direct competition with plants, or activating immune responses regulated by microorganisms. Consequently, the rhizosphere was widely recognized as the primary barrier against soil-borne pathogens. Furthermore, plants had the ability to develop defense mechanisms against soil-borne pathogens through the targeted stimulation of antagonistic microorganisms, resulting in a significant increase in the abundance of these antagonistic microorganisms. In this study, the prolonged cultivation of chrysanthemum over numerous years led to the microbial community structure towards an unfavorable environment for plant growth. Significant decrease was observed in the populations of beneficial bacteria,specifically Nitrosospira and Pirellula, as well as in the proportion of antagonistic microorganisms, such as Actinbacteria and Aspergillus. Conversely, a noteworthy increase was observed in the proportion of pathogen and saprophytic fungi, including species in Myriococcum, Rhizophlyctis, and Ascobolus. Moreover, a significant rise in the occurrence of F. solani, the causative agent of localized chrysanthemum wilt disease, was observed, surpassing a prevalence of 60%. Consequently, the soil microbial community underwent a gradual modification, adversely affecting plant growth and resulting in the emergence of soil-borne Fusarium wilt among the native chrysanthemum population. However, the specific molecular mechanisms governing the interaction between F. solani and chrysanthemum remain unexplored. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct further investigation on the interplay between pathogen and host, as it will augment our understanding of the fundamental molecular mechanisms implicated in pathogen infiltration.

Figure 1.

Chrysanthemum disease symptoms investigated in the field. (A) The Fusarium wilt field, (B) The diseased plants. (C) The statistical analysis of plant height and leaf width of both Fusarium wilt and healthy plants.

Figure 1.

Chrysanthemum disease symptoms investigated in the field. (A) The Fusarium wilt field, (B) The diseased plants. (C) The statistical analysis of plant height and leaf width of both Fusarium wilt and healthy plants.

Figure 2.

Morphological characteristics of Fusarium strains and identification. (A-D) The colony and light microscope images of the type A strain at a magnification of 400×. (E-H) The colony and light microscope images of the type B strain at a magnification of 400×. (I) A neighbour-joining tree was constructed based on ITS sequences of strain F. oxysporum (Fo) and F. solani (Fs).

Figure 2.

Morphological characteristics of Fusarium strains and identification. (A-D) The colony and light microscope images of the type A strain at a magnification of 400×. (E-H) The colony and light microscope images of the type B strain at a magnification of 400×. (I) A neighbour-joining tree was constructed based on ITS sequences of strain F. oxysporum (Fo) and F. solani (Fs).

Figure 3.

The pathogenicity test of Fo and Fs. (A-C) Symptoms of of each treatment group at 0 dpi. (D-F) Symptoms of each treatment group at 30 dpi.

Figure 3.

The pathogenicity test of Fo and Fs. (A-C) Symptoms of of each treatment group at 0 dpi. (D-F) Symptoms of each treatment group at 30 dpi.

Figure 4.

The activity of cell wall degrading enzymes produced by F. solani. Cellulase (CX), β-glucosidase (βG), Pectin methylgalactuionase (PMG), polygalacturonase (PG).

Figure 4.

The activity of cell wall degrading enzymes produced by F. solani. Cellulase (CX), β-glucosidase (βG), Pectin methylgalactuionase (PMG), polygalacturonase (PG).

Figure 5.

The pathogenic process of chrysanthemum following infection by F. solani. Control group (CK); Treatment group (Fs).

Figure 5.

The pathogenic process of chrysanthemum following infection by F. solani. Control group (CK); Treatment group (Fs).

Figure 6.

The invasion of chrysanthemum roots by F. solani under scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at magnifications ranging from 200-2.0 k×. (A, C, E, G, I) The roots of the control group were observed at 12 h, 1 d, 3 d, 5 d, and 10 d. (B, D, F, H, J, K, L) The roots of the pathogen infection group were observed at 12 h, 1 d, 3 d, 5 d, and 10 d.

Figure 6.

The invasion of chrysanthemum roots by F. solani under scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at magnifications ranging from 200-2.0 k×. (A, C, E, G, I) The roots of the control group were observed at 12 h, 1 d, 3 d, 5 d, and 10 d. (B, D, F, H, J, K, L) The roots of the pathogen infection group were observed at 12 h, 1 d, 3 d, 5 d, and 10 d.

Figure 7.

The process of F. solani infecting chrysanthemum roots under laser confocal scanning microscopy (LCSM) (400×). (A, E, I, M, Q) The roots of the control group at 12 h, 1 d, 3 d, 5 d and 10 d. (B-D, F-H, J-L, N-P and R-T) The roots of the pathogen infection group at 12 h, 1 d, 3 d, 5 d and 10 d.

Figure 7.

The process of F. solani infecting chrysanthemum roots under laser confocal scanning microscopy (LCSM) (400×). (A, E, I, M, Q) The roots of the control group at 12 h, 1 d, 3 d, 5 d and 10 d. (B-D, F-H, J-L, N-P and R-T) The roots of the pathogen infection group at 12 h, 1 d, 3 d, 5 d and 10 d.

Figure 8.

Physiological responses of chrysanthemum to F. solani inoculation (A) Plant growth and photosynthetic pigment changes on the 15 dpi of F. solani. (B) Changes of nutrient contents in plants after inoculation by F. solani, including protein, soluble sugar, and Ca, P, K content. (C) Changes of hydrogen peroxide and MDA content in plant leaves after F. solani inoculation. (D) Changes of antioxidant enzyme activity in leaves after inoculation including Catalase, Peroxidase and Superoxide dismutase. (E) Changes of leaf defense enzyme activity after inoculation, including Polyphenol oxidase, Phenylalanine ammonialyase and Chitinase. (F) Changes of JA and SA in leaves after F. solani inoculation.

Figure 8.

Physiological responses of chrysanthemum to F. solani inoculation (A) Plant growth and photosynthetic pigment changes on the 15 dpi of F. solani. (B) Changes of nutrient contents in plants after inoculation by F. solani, including protein, soluble sugar, and Ca, P, K content. (C) Changes of hydrogen peroxide and MDA content in plant leaves after F. solani inoculation. (D) Changes of antioxidant enzyme activity in leaves after inoculation including Catalase, Peroxidase and Superoxide dismutase. (E) Changes of leaf defense enzyme activity after inoculation, including Polyphenol oxidase, Phenylalanine ammonialyase and Chitinase. (F) Changes of JA and SA in leaves after F. solani inoculation.

Figure 9.

Analysis of soil bacterial microbial community structure. (A) Sample sparsity curve and Shannon index. (B) Relative abundance of bacterial at phylum level. (C) Relative abundance of bacteria at genus level. (D) Sample difference analysis, LEfSE analysis, PCoA principal coordinate analysis and Sample similarity tree.

Figure 9.

Analysis of soil bacterial microbial community structure. (A) Sample sparsity curve and Shannon index. (B) Relative abundance of bacterial at phylum level. (C) Relative abundance of bacteria at genus level. (D) Sample difference analysis, LEfSE analysis, PCoA principal coordinate analysis and Sample similarity tree.

Figure 10.

Analysis of soil fungal microbial community structure. (A) Sample sparsity curve and Shannon index. (B) Relative abundance of fungi at phylum level. (C) Relative abundance of fungi at genus level. (D) Relative abundance of Fusarium at species level. (E) Sample difference analysis, LEfSE analysis, PCoA principal coordinate analysis and Sample similarity tree.

Figure 10.

Analysis of soil fungal microbial community structure. (A) Sample sparsity curve and Shannon index. (B) Relative abundance of fungi at phylum level. (C) Relative abundance of fungi at genus level. (D) Relative abundance of Fusarium at species level. (E) Sample difference analysis, LEfSE analysis, PCoA principal coordinate analysis and Sample similarity tree.

Table 1.

Statistics of disease incidence and index in 10th, 20th days.

Table 1.

Statistics of disease incidence and index in 10th, 20th days.

| |

10 d |

20 d |

| Incidence (%) |

Index (%) |

Incidence (%) |

Index (%) |

| CK |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Fs |

53.85 |

42.31 |

92.30 |

65.38 |