1. Introduction

Morchella has gained increasing popularity due to its unique flavor and rich nutritional value. It is abundant in amino acids, polysaccharides, trace elements, and bioactive compounds and also exhibits anti-fatigue, antioxidant, antibacterial, antitumor, and immune-regulating properties [

1,

2,

3]. Although, the global commercial demand for Morchella continues to rise, wild harvests remain extremely limited. Despite over 130 years of domestication and cultivation history, significant breakthroughs in Morchella cultivation in China were not achieved until 2012. This led to a rapid expansion of cultivation areas to meet global demand [

4,

5,

6].

Currently, several Morchella species can be artificially cultivated. However, the primary cultivar remains the high-yielding and resilient

Morchella sextelata [

1,

7]. The cultivation method involves sowing spores directly into the soil and relying on exogenous nutrient bags for growth and development. This soil-covering system has become increasingly intensive and has begun to resemble other agricultural crops in terms of the emergence of continuous cropping obstacles. As the duration of consecutive planting increases and the scale of cultivation expands, the issue of impediments to continuous cropping has become more pronounced [

8,

9,

10].

The primary factors that impede the continuous cropping of Morchella are alterations in soil microbial community structure, deterioration of soil physicochemical properties, and accumulation of autotoxic substances [

9,

10]. Tan et al. reported a positive correlation between Morchella yield and soil microbial diversity and evenness. In nonfruiting soils, fungal communities were dominated by

Acremonium or

Mortierella, suggesting an essential link between Morchella fruiting body formation and soil microecology. Actinomycetes and other microbial groups in the substrate may also restrict the overproliferation of nitrogen-fixing microorganisms (e.g., cyanobacteria) during the fruiting stage in which accumulating lipids support fruiting body development [

11]. In other work,

Pseudomonas constituted up to 25.30% of the dominant bacterial community in the soil during the primordium differentiation stage [

12], and a study by Zhang et al. revealed that continuous cropping stimulates saprophytic fungal activity that leads to significant nutrient accumulation in the soil. This inhibits primordium formation and ultimately causes a sharp decline in Morchella yield, indicating a dynamic interplay between beneficial and pathogenic fungal taxa in the soil’s microbial community [

13]. Furthermore, Yu et al. identified key bacterial taxa involved in soil microbial genetic diversity, including nitrogen-fixing and nitrifying genera such as

Arthrobacter,

Bradyrhizobium,

Devosia,

Pseudarthrobacter,

Pseudomonas and

Nitrospira in high-yield soils [

5]. Comparative analysis of soils used for

Morchella sextelata cultivation over 0, 1, and 2 years has demonstrated that continuous cropping acidifies soil, increases pathogenic fungal populations, and reduces yield [

14].

To investigate the key microorganisms and metabolites associated with continuous cropping obstacles for Morchella, we analyzed soils from noncontinuous and 1-year continuous cropping systems. Microbial community changes were examined via microbiome analysis to identify critical microbial taxa, and metabolome profiling was employed to detect differential metabolites. We expect our results to enhance the understanding of how continuous cropping impacts soil ecosystems, provide a theoretical basis for elucidating the mechanisms that underpin the obstacles to the continuous cropping of Morchella, and help to identify effective solutions to improve cultivation productivity in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.1.1. Strains and Cultivation

Test strain: Morchella sextelata YMe151, preserved at the Edible Fungi Industry Technology Innovation Laboratory of Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

Continuous cropping cultivation: The continuous cropping method sued followed Chai Hongmei et al. Cultivation was conducted in a demonstration greenhouse at the Azizuo Edible Fungi Base. Soil with no prior Morchella cultivation served as the control (CN), and soil with one year of continuous Morchella cultivation was the treatment specimen (CC). Uniformly prepared spawn was broadcast-seeded onto soil beds. Approximately 7 days post-sowing, nutrient bags were placed when white conidia appeared on the soil surface. Soil temperature was maintained at 6–20°C, soil moisture at 20%–28%, and air relative humidity at 60%–80%.

2.1.2. Soil Sample Collection

All soil samples were collected during the Morchella harvest period in February, 2023. For the 0-year (CN) and 1-year (CC) treatments, soil samples were collected in 12 groups with three replicates each. Using the five-point sampling method, surface soil was removed, and soils from a depth of 3 cm within a 5 cm radius were collected to form 200 g composite samples. All samples were stored at 4°C for freshness and processed within 24 hours.

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Analysis of Soil Physicochemical Properties

Soil samples were air-dried and sieved prior to physicochemical analysis. pH was determined following the Determination of Soil pH (NY/T 1377-2007), and organic matter, total nitrogen, available phosphorus, exchangeable calcium, and magnesium were each analyzed according to the Soil Testing (NY/T 1121-2006). Available potassium was measured using Determination of Available and Slowly Available Potassium in Soil (NY/T 889-2004), and available zinc, manganese, and copper were quantified via Determination of Available Zinc, Manganese, Iron, and Copper in Soil — DTPA Extraction Method (NY/T 890-2004). Total porosity was assessed using the core method, and. Soil texture was determined per Determination of Forest Soil Particle Composition (Mechanical Composition) (LY/T 1225-1999). Finally, soil moisture was measured following Soil Moisture Determination (NY/T 52-1987).

2.2.2. High-Throughput Illumina Sequencing of Soil Microbes

Genomic DNA was extracted from soil samples using the Mag Pure Soil DNA LQ Kit, diluted to 1 ng·μl-1 with sterile water, and stored at -80°C. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification of microbial DNA was performed using barcode-tagged primers: 338F/806R for the 16S V4–V5 region and ITS1F/ITS2R for the ITS region. The PCR reaction mixture (30 μl) contained 15 μl of 2×Gflex PCR Buffer, 0.6 μl of Tks Gflex DNA Polymerase (1.25 U·μl-1), 1 μl of each primer (5 μM), 1 μl of gDNA (50 ng), and sterile water to adjust the total volume to 30 μl. The thermal cycling program included an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min; 26 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 20 s; followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were evaluated by electrophoresis, purified using the Qubit dsDNA Assay Kit (Life Technologies) with magnetic beads, and subjected to a second round of PCR amplification. After re-purification and quantification via Qubit, equal amounts of PCR products were pooled and sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform by Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology Co., Ltd.

2.2.3. Soil LC-MS Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis

Soil samples were supplemented with an alcohol-based extraction solution and subjected to cryogenic grinding under low-temperature conditions. Metabolites were extracted via low-temperature ultrasonication and solvent extraction. Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with Fourier transform mass spectrometry (UHPLC-Q Exactive HF-X system) was employed for analysis. Chromatographic separation utilized an ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm i.d., 1.8 µm; Waters, Milford, USA) in which the mobile phase consisted of the following: Phase A: 95% water and 5% acetonitrile (containing 0.1% formic acid); Phase B: 47.5% acetonitrile, 47.5% isopropanol, and 5% water (containing 0.1% formic acid). The injection volume was 3 μL, and the column temperature was maintained at 40°C. Metabolites were ionized via electrospray ionization (ESI), with mass spectra acquired in both positive and negative ion modes. Quality control (QC) samples prepared by pooling equal-volume aliquots from all extracts were analyzed to evaluate system stability. Chromatographically separated components were continuously introduced into the mass spectrometer for data acquisition.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data processing was performed using Microsoft Excel 2016. Testing for differences between treatment and control samples and principal component analysis (PCA) were conducted with SPSS 26.0. Correlation analysis and cluster heatmap visualization were implemented in RStudio. For microbial diversity analysis, Illumina MiSeq sequencing data were processed in FASTQ format. The raw data were trimmed using Cutadapt software, and quality control analyses, including filtering, denoising, and merging, were performed using DADA2 software. Based on the sequence data of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) and representative sequences, QIIME 2 software was used for database comparison and annotation. The 16S data were compared against the Silva database (version 138), and the ITS data were compared against the UNITE database. Additionally, statistical analysis was conducted to assess the distribution, α-diversity, and β-diversity of microbial communities.

Metabolomics analysis: Raw metabolomics data were processed using Progenesis QI v3.0 software (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA) for peak extraction, alignment, and identification, which ultimately yielded a data matrix that contained retention time, peak area, mass-to-charge ratio, and identification information. These data underwent feature peak library identification in which MS and MS/MS mass spectrometry information was matched with mainstream public metabolomics databases. Metabolites were identified based on their secondary mass spectrometry matching scores.

3. Results

3.1. Differences in Soil Physicochemical Properties

The results of the physicochemical analysis of soils with continuous cultivation of Morchella compared to noncontinuous cultivation are presented in

Table 1. Relative to the control, the pH and available potassium content decreased in the continuously cultivated soil. However, the contents of organic matter, hydrolyzed nitrogen, available phosphorus, total porosity, and soil moisture were higher. This suggests that continuous cultivation changes soil structure nutrient content.

3.2. Soil Microbial Diversity and Composition

To investigate whether soil microorganisms contribute to the obstacles to the continuous cultivation of Morchella, soil samples from noncontinuous cultivation areas were used as controls. Soil samples from areas with one year of continuous cultivation were collected, and DNA was extracted. Microbial community characteristics were determined using the HiSeq high-throughput sequencing method, where the numbers of raw sequences for bacterial and fungal amplifications were 489,751 and 620,410, respectively. After quality control and chimera filtering, 474,189 bacterial sequences and 587,768 fungal sequences were obtained. Following database comparison, 5,288 bacterial OTUs and 1,847 fungal OTUs were identified, with a sequence similarity of 97%.

The α-diversity of the microbial communities in different soil samples was analyzed using Shannon and Simpson diversity indices, which showed that for both bacteria and fungi, the α-diversity in the continuously cultivated soils was lower, although the differences compared to the control soil were not statistically significant (

Figure 1a,b,d,e). In terms of β-diversity based on unweighted_UniFrac distance, the Adonis test for inter-group differences indicated a clear separation between the microbial communities in continuously cultivated versus non continuously cultivated soils, but the differences between the two groups were again not statistically significant (

Figure 1c,f).

The top 10 bacterial phyla are depicted in

Figure 2a. Both continuously cultivated and noncontinuously cultivated soils were predominantly composed of Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, Chloroflexi, and Acidobacteriota, which accounted for approximately 80% of the total. The relative abundance of Actinobacteriota was slightly higher in continuously cultivated soils. Notably, continuously cultivated soils contained a significant amount of Cyanobacteria. At the genus level, the contents of Arthrobacter, Pseudomonas, and Streptomyces were significantly higher in continuously cultivated soils compared to control soils. Additionally, Tychonema was specifically present in continuously cultivated soils (

Figure 2b).

Regarding fungal taxonomic composition, the dominant phyla were Ascomycota, Mortierellomycota, and Basidiomycota. Compared to the control, the relative abundance of Ascomycota and Mortierellomycota was higher in continuously cultivated soils, but Basidiomycota and Rozellomycota were lower (

Figure 2c). At the genus level, the relative abundance of Mortierella, Cephalotrichum, and Myceliophthora were higher in continuously cultivated soils, whereas Saitozyma, Penicillium, Aspergillus, and Geminibasidium were lower (

Figure 2d).

3.3. Differential Analysis of Soil Microorganisms and Key Biological Biomarkers

To investigate the impact of continuous cultivation of Morchella on key biological biomarkers in the soil, we employed LEfSe analysis with an LDA threshold of 3. In noncontinuously cultivated soils,

Flavobacterium,

Ensifer, and

Neochlamydia were identified as key biomarkers for the bacterial community, and

Aspergillus,

Saitozyma, and

Geminibasidium were key biomarkers for the fungal community. In continuously cultivated soils,

Arthrobacter,

Tychonema, and

Pseudomonas were key biomarkers for the bacterial community, and

Myceliophthora,

Cephalotrichum, and

Trichoderma were key biomarkers for the fungal community (

Figure 3). Intergroup t-tests were conducted to determine significantly different microbial populations (P < 0.05), and these results showed that in the bacterial community,

Arthrobacter (P=0.0001),

Rhodanobacter (P=0.0045), and

Luteimonas (P=0.008) were significantly higher in continuously cultivated soils compared to the control group and that

Streptomyces (P=0.0164) and

Bacillus (P=0.0463) were significantly higher as well. In the fungal community,

Cephalotrichum (P=0.0032),

Myceliophthora (P=0.0055), and

Lophiotrema (P=0.0027) were significantly higher in continuously cultivated soils compared to the control group, as were

Trichoderma (P=0.0130) and

Coniochaeta (P=0.0172) (

Figure 4).

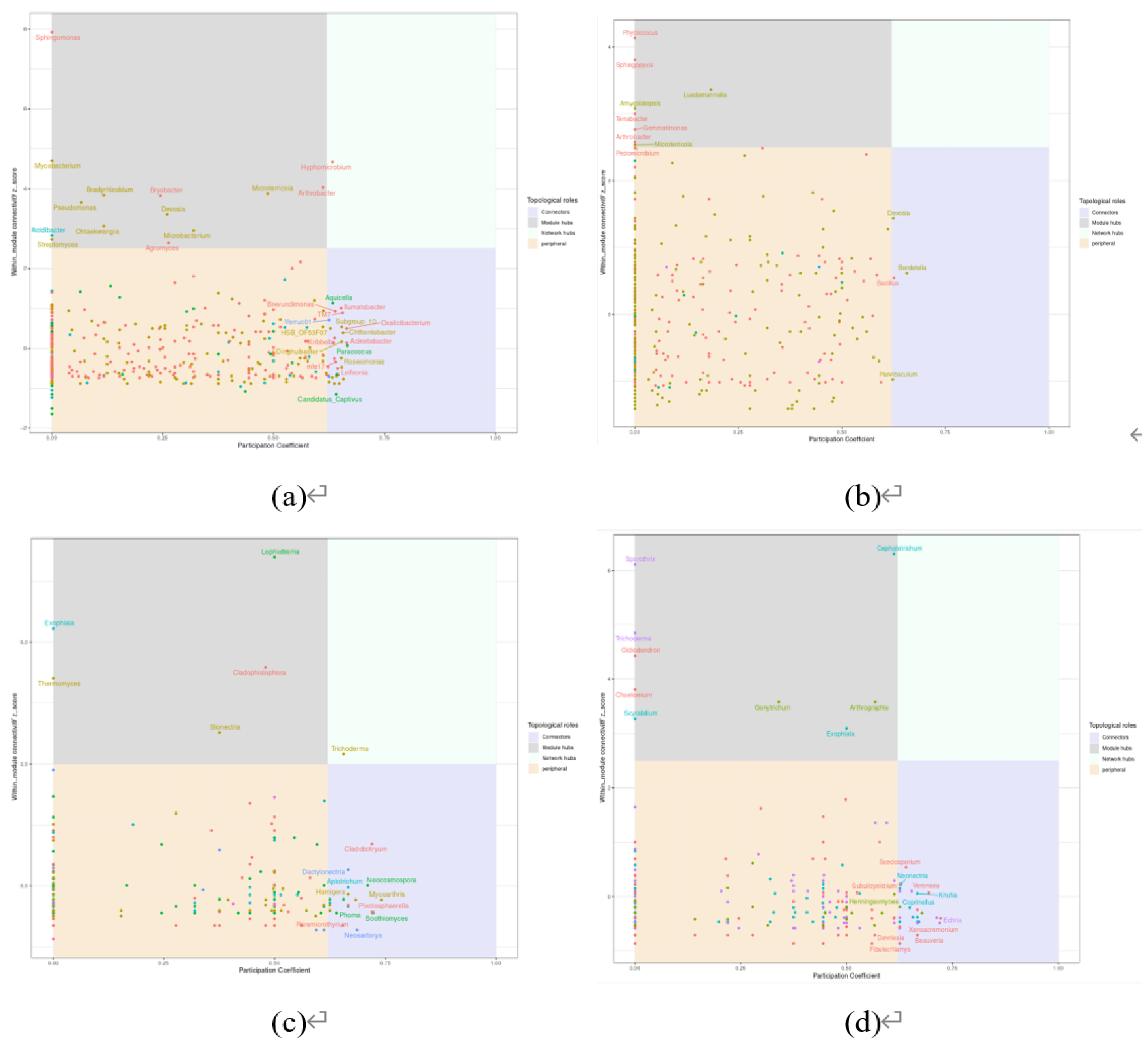

3.4. Soil Microbial Interactions

Co-occurrence network analysis was conducted at the genus level for all microorganisms in order to construct microbial networks for the NC (noncontinuous cultivation) and CC (continuous cultivation) samples. Overall, whether for bacteria or fungi, the complexity of microbial interactions in continuously cultivated soils was higher than in control soils. Moreover, the proportion of negative connections was also greater than that of positive connections, indicating that the microbial network patterns in soils planted with Morchella were primarily characterized by negative correlations, with competitive interactions being more dominant (

Figure 5). Microbial communities can be identified based on the modularity within modules (Zi) and between modules (Pi) in the network, which allows for the determination of key groups (

Figure 6). There were 13 key bacterial groups in continuously cultivated soils and 45 in noncontinuously cultivated soils. For fungi, there were 41 key groups in continuously cultivated soils and 27 in noncontinuously cultivated soils. This suggests that fungal communities may have a greater impact on the cultivation of Morchella.

Table 2.

The main properties of the co-occurrence network.

Table 2.

The main properties of the co-occurrence network.

| |

Node |

Positive edge |

Negative edge |

Average degree |

Modularity |

Average clustering coefficient |

Average path distance |

Hub nodes |

NC

bacteria

|

406 |

1751 |

2626 |

21.56 |

0.43 |

0.476 |

2.302 |

45 |

CC

bacteria

|

374 |

2216 |

2375 |

24.55 |

0.53 |

0.469 |

2.598 |

13 |

NC

fungi

|

216 |

247 |

338 |

5.42 |

0.42 |

0.188 |

3.161 |

27 |

CC

fungi

|

243 |

357 |

435 |

6.52 |

0.37 |

0.245 |

2.773 |

41 |

3.5. Construction of Generalist and Specialist Microbial Communities in the Soil

In the noncontinuously cultivated soils, a total of 4,377 bacterial OTUs were detected, among which five OTUs (OTU131, OTU2463, OTU3336, OTU4020, and OTU2668) were identified as generalist species. Twenty OTUs were identified as specialist species, including plant growth-promoting bacteria such as Ensifer and Gemmatimonas. The remaining 4,352 OTUs were classified as other bacterial groups. For fungi, 1,338 OTUs were detected, with 19 OTUs identified as generalist species and 12 OTUs identified as specialist species, including the pathogen Venturia. The remaining 1,307 OTUs were classified as other fungal groups.

In the continuously cultivated soils, a total of 4,164 bacterial OTUs were detected, among which nine OTUs were identified as generalist species, including beneficial bacteria such as Thermoactinomyces and Tumebacillus. Twenty-nine OTUs were identified as specialist species, including beneficial bacteria like Cellvibrio, Flavobacterium, Lysobacter, Pedobacter, and Rheinheimera, as well as potential pathogens such as Arthrobacter, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Serratia, and Streptomyces. The remaining 4,126 OTUs were classified as other bacterial groups. For fungi, 1,354 OTUs were detected, with 19 OTUs identified as generalist species, including pathogens such as Botrytis and Fusariella. Fourteen OTUs were identified as specialist species, including the pathogen Neonectria, and the remaining 1,321 OTUs were classified as other fungal groups.

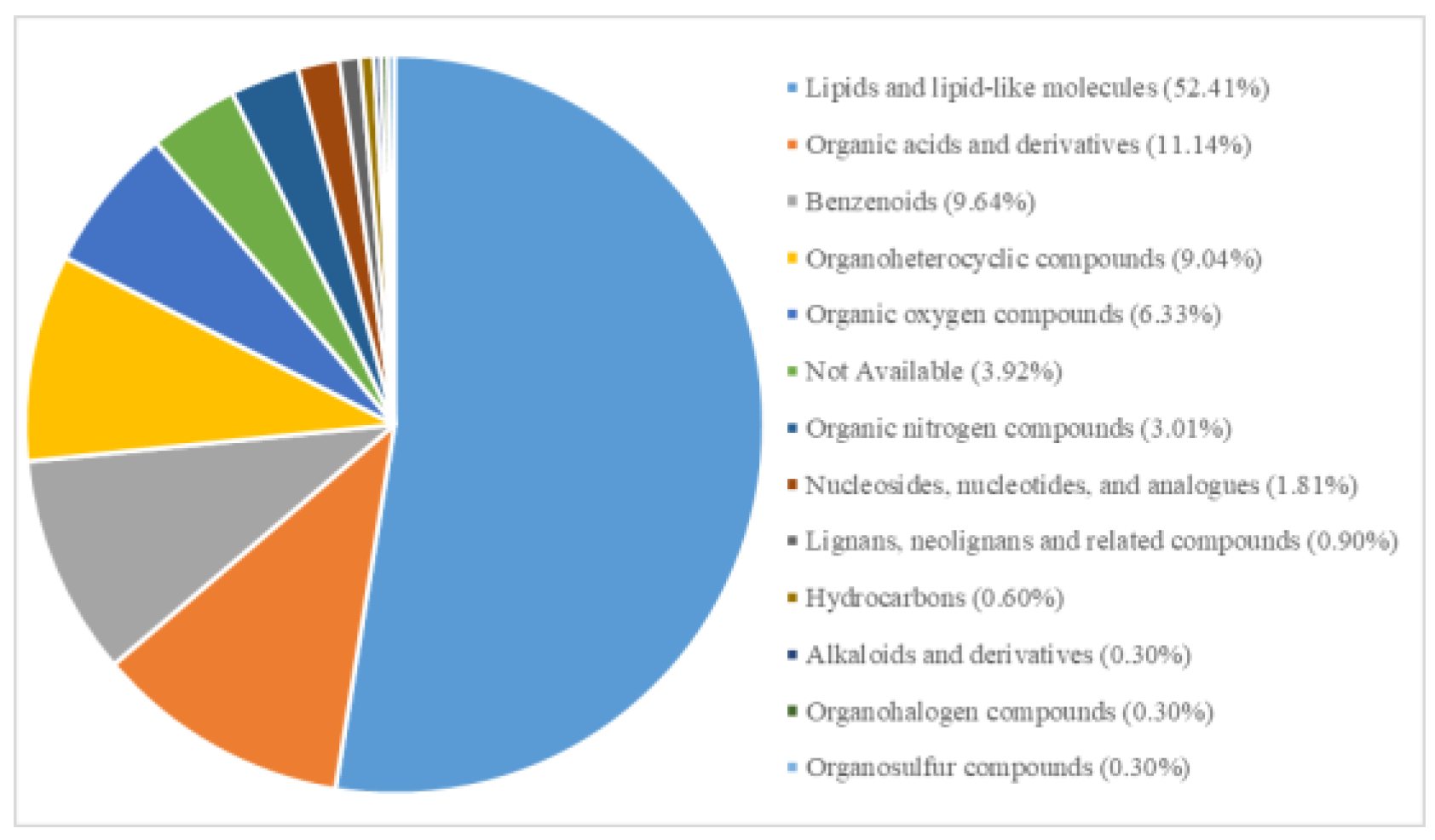

3.6. Metabolome Composition Analysis

To understand the impact of continuous cultivation on soil metabolites, we conducted metabolomics analysis on soils with and without continuous cultivation of Morchella. After filtering, imputation, normalization, and log transformation, a total of 368 metabolites were obtained. In positive and negative ion modes, 197 and 171 metabolites were identified, respectively. Among these, 332 metabolites were classified into 13 categories (

Figure 7). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) showed that the continuously cultivated and control soils were separated, with the control group having a larger confidence interval than the continuously cultivated group. This suggests that the continuously cultivated group may exhibit less variability in the metabolome (

Figure 8).

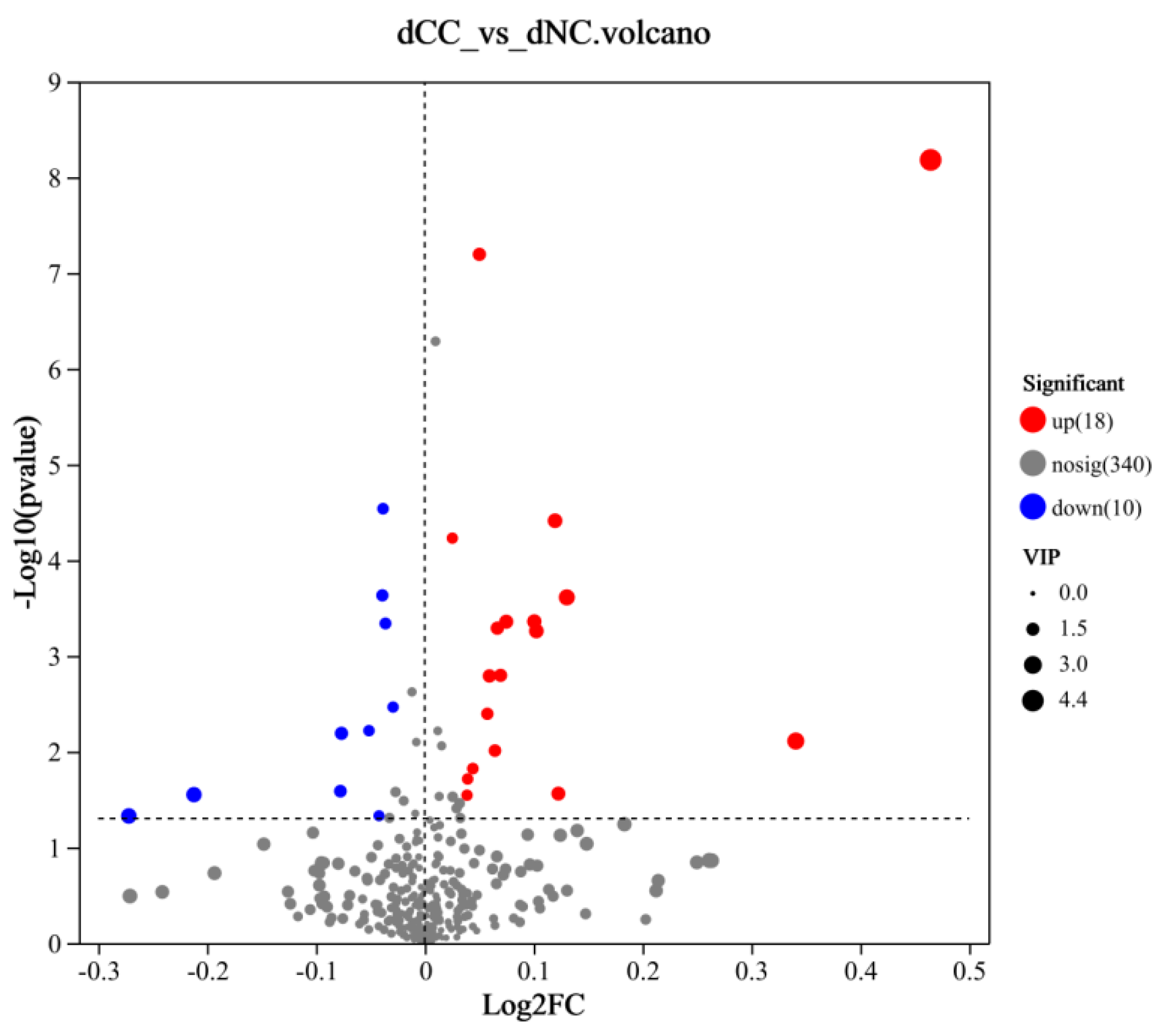

3.7. Analysis of Differentially Accumulated Metabolites

Differentially accumulated metabolites were screened using OPLS-DA analysis between groups. Metabolites with VIP ≥ 1, P ≤ 0.05 in t-tests, and fold change (FC) > 1 were selected as differentially accumulated metabolites. Twenty-eight significantly different metabolites were identified, among which 18 metabolites were upregulated in continuously cultivated soil samples (

Figure 9,

Table 1), and 10 metabolites were downregulated. The upregulated metabolites were primarily lipids and lipid-like molecules, but the most significantly upregulated metabolites were 2,4,5-Trichloro-6-Hydroxybenzene-1,3-Dicarbonitrile and 2,4-Dichloro-6-nitrophenol, both belonging to benzenoids. Benzenoids possess certain toxicity, have strong adsorption and mobility in soil, and can accumulate easily, all of which affects soil microorganisms and plant growth. The most significantly downregulated metabolites were organic acids and their derivatives. In summary, continuous cultivation may primarily alter the content of acidic substances and toxic benzenoids in the soil, thereby impacting the cultivation of Morchella.

3.8. KEGG Enrichment Analysis

To understand further the metabolic pathways in which the differentially accumulated metabolites in continuously cultivated soils participate compared to noncontinuously cultivated soils, we annotated these metabolites using the KEGG database. These results showed that three metabolites in continuously cultivated soils were significantly enriched in Linoleic acid metabolism. One metabolite each was significantly enriched in Aflatoxin biosynthesis, Parkinson’s disease, and Betalain biosynthesis. In noncontinuously cultivated soils, two metabolites were significantly enriched in Galactose metabolism, and one metabolite each was significantly enriched in Sphingolipid metabolism, Oxidative phosphorylation, and the Sphingolipid signaling pathway.

Figure 10.

KEGG enrichment pathways of differentially accumulated metabolites. The x-axis represents the enrichment ratio, calculated as num_in_study/num_in_pop, and the y-axis represents the KEGG pathways. The size of the bubbles in the figure indicates the number of compounds enriched in each pathway, and the color of the bubbles represents the significance of enrichment, with different colors corresponding to different p-values.

Figure 10.

KEGG enrichment pathways of differentially accumulated metabolites. The x-axis represents the enrichment ratio, calculated as num_in_study/num_in_pop, and the y-axis represents the KEGG pathways. The size of the bubbles in the figure indicates the number of compounds enriched in each pathway, and the color of the bubbles represents the significance of enrichment, with different colors corresponding to different p-values.

4. Discussion

Morchella is renowned as the „king of fungi” due to its rarity and unique flavor. However, its typical cultivation method, similar to other crops, can generate certain obstacles to continuous cultivation. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms that underlie these obstacles may help to stabilize Morchella yields, and as such in this study we employed microbione and metabolomics techniques to identify the most important microorganisms and metabolites that may present the largest obstacles to continuous cultivation.

From the perspective of soil physicochemical properties, Morchella cultivation leads to decreased soil pH and available potassium content and increases organic matter, hydrolyzed nitrogen, and available phosphorus. These changes are primarily driven by the interactions among Morchella, soil microorganisms, and organic matter decomposition. During growth, Morchella secretes various organic acids and consumes significant amounts of available potassium. The soil then becomes more suitable for herbaceous plant growth, resulting in increased organic matter content. Soil microorganisms decompose organic matter, consuming available potassium and producing acidic substances, which release large amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus. Enzymes secreted by Morchella can decompose soil organic matter, releasing hydrolyzed nitrogen and available phosphorus. Indeed, the content of available phosphorus often correlates positively with organic matter content, and increased organic matter leads to an abundance of phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria that facilitate the conversion of ineffective phosphorus to available phosphorus.

Continuous cropping obstacles involve changes in soil microbial community structure and typically result in increased pathogenic bacteria and decreased beneficial microorganisms. Previous studies have shown that continuous cropping affects the microbial community in the rhizosphere of Goji, with an increase in harmful plant pathogens such as

Pseudomonas,

Arthrobacter, and

Trichoderma over time [

15]. In continuous cropping models of ginseng and tomato,

Rhodanobacter often plays a dominant role [

16,

17]. Our present results indicate that compared to noncontinuous cultivation control soils, the α-diversity and β-diversity of microorganisms in continuously cultivated soils are not statistically different. However, the composition and differential analysis of bacterial communities in continuously cultivated soils, as well as LEfSe analysis, suggest that

Arthrobacter,

Tychonema,

Rhodanobacter,

Luteimonas, and

Streptomyces may play unique roles in continuous cropping soil. Reports have shown that in soils with low or no Morchella production, fungi such as

Gibberella,

Microidium,

Sarocladium, and

Streptomyces is more prevalent [

14]. We also also found that

Streptomyces was significantly more abundant in continuously cultivated soils compared to noncontinuously cultivated soils in the present study.

Compared to bacterial communities, fungal communities exhibited greater differences between treatment and control soils. In continuously cultivated soils,

Cephalotrichum,

Myceliophthora, and

Lophiotrema were significantly higher, and

Trichoderma and

Coniochaeta were also notably elevated. Conversely,

Geminibasidium and

Thermomyces were significantly lower, as was also reduced. Research on Morchella continuous cropping obstacles has shown that carbendazim treatment can decrease the relative abundance of the fungal pathogen

Phytophthora in continuously cultivated soils[

9], and studies on the intercropping of

Cinnamomum camphora and

Polygonatum multiflorum have demonstrated a significant increase in

Saitozyma abundance [

18]. Reports also indicate that fungi such as Penicillium, Trichoderma, Aspergillus, and Fusarium increase in abundance during continuous cultivation of Morchella, potentially becoming major pathogens that reduce the yield of

Morchella sextelata in particular[

8].

Penicillium,

Trichoderma,

Aspergillus,

Fusarium,

Botrytis,

Clonostachys,

Acremonium,

Mortierella and

Paecilomyces are pathogenic fungi often found in various types of edible fungi and plant production, and in soils with low or no Morchella production,

Gibberella,

Microidium,

Sarocladium, and

Streptomyces have been found to be prevalent [

14]. We also found that

Trichoderma and

Streptomyces were significantly elevated and dominant in continuously cultivated soils, suggesting they may be key microorganisms that contribute to obstacles to Morchella continuous cropping.

In addition, our metabolomics analysis of Morchella continuously cultivated soils identified 368 metabolites, primarily including lipids and lipid-like molecules, organic acids and their derivatives, benzenoid compounds, and organic heterocyclic compounds. This aligns with previous metabolomics results for Morchella that have indicated that the metabolites in cultivated soils are mainly derived from Morchella metabolism. Among these, 28 metabolites showed significant differences, with 18 being upregulated and 10 downregulated in continuously cultivated soils. Previous studies have found that phenolic acid extracts have a hindering effect on Morchella continuous cropping [

10], and our current results revealed that benzenoid compounds and aflatoxin B2 were relatively abundant in continuously cultivated soils and that urea was low. This may contribute to the hindrance of continuous cropping of Morchella.

Finally, we also found several important compounds that may contribute to impeding continuous Morchella cropping. For example, 2,4,5-Trichloro-6-Hydroxybenzene-1,3-Dicarbonitrile is a benzenoid compound with relatively low toxicity [

19], and 2,4-Dichloro-6-nitrophenol (DCNP) is an aromatic nitro derivative formed through the photo-nitration of 2,4-dichlorophenol (DCP), an environmental transformation intermediate of the herbicide propanil. DCNP exhibits genotoxicity that induces gene mutations and chromosomal aberrations [

20,

21,

22]. Furthermore, aflatoxins are compounds with a basic structure that contains a difuran and a coumarin (oxynaphthoquinone), and previous studies have shown that phenolic acids may play a crucial role in soil diseases that affect Morchella. Moreover, cinnamic acid, a phenolic compound, inhibits the growth of three species of cultivated Morchella (M. sextelata, M. eximia, and M. importuna) [

10,

23]. Cinnamic acid can cyclize to form coumarin under acidic conditions. Additionally, the presence of aflatoxin B2, which contains coumarin, in continuously cultivated soils suggests it may also exert toxic effects that hinder continuous cropping.

5. Conclusions

As Morchella cultivation becomes increasingly more feasible and therefore widespread, obstacles to its continuous cropping severely limit the output of the Morchella industry. This study, through microbiome and metabolome analysis, that changes in soil microbial community structure, increased abundance of fungal pathogens, and accumulation of toxic metabolites can each hinder continuous cropping. However, further research is needed to determine the sources, minimum effective doses, and threshold intensities of these toxic metabolites.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.X.Y. and G.T.T.; methodology, P.Y.; validation, P.Y., and N.T.; formal analysis, P.Y.; investigation, P.Y. and C.X.Y.; resources, G.T.T.; data curation, P.Y., N.T., W.M.C., and J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, P.Y.; writing—review and editing, P.Y., C.X.Y., and G.T.T.; visualization, W.M.C., and J.Z.; supervision, C.X.Y., and G.T.T.; project administration, C.X.Y., and G.T.T.; funding acquisition, C.X.Y., and G.T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “The Yunnan Provincial Joint Special Key Project of Agricultural Basic Research, grant number 202501BD070001-022” and “ The Yunnan Province Fumin County Prefabricated Vegetable Industry Science and Technology Special Mission”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, Q.; Ma, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, C. Artificial cultivation of true morels: current state, issues and perspectives. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2018, 38, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambyal, K.; Singh, R.V. A comprehensive review on Morchella importuna: cultivation aspects, phytochemistry, and other significant applications. Folia Microbiol 2021, 66, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunil, C.; Xu, B. Mycochemical profile and health-promoting effects of morel mushroom Morchella esculenta (L.) - A review. Food Res Int 2022, 159, 111571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F. History, present situation and prospect of artificial cultivation of morels. Edible Med. Mushrooms 2016, 24, 140–144. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.M.; Jayawardena, R.S.; Thongklang, N.; Lv, M.L.; Zhu, X.T.; Zhao, Q. Morel production associated with soil nitrogen-fixing and nitrifying microorganisms. J Fungi 2022, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; He, P.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Perez-Moreno, J.; Yu, F. Large-scale field cultivation of Morchella and relevance of basic knowledge for its steady production. J Fungi 2023, 9, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X. Review on species resources, resproductive modes and genetic diversity of black morels. J. Fungal Res. 2019, 17, 240–251. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Cai, Y.; Ma, X.; He, P. Evaluation system of cultivating suitability for the productive strains of Morchella mushrooms. J. Light Ind. 2022, 37, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Shao, G.; Zhou, T.; Fan, Q.; Yang, N.; Cui, M.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, R. Dazomet changes microbial communities and improves morel mushroom yield under continuous cropping. Front Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1200226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Chen, Z.; He, P.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W.; Cao, X. Allelopathic effects of phenolic acid extracts on Morchella mushrooms, pathogenic fungus, and soil-dominant fungus uncover the mechanism of morel continuous cropping obstacle. Arch Microbiol 2024, 206, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Liu, T.; Yu, Y.; Tang, J.; Jiang, L.; Martin, FM.; Peng, W. Morel production related to soil microbial diversity and evenness. Microbiol Spectr. 2021, 9, e0022921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Long, L.; Hu, Z.; Yu, X.; Liu, Q.; Bao, J.; Long, Z. Analyses of artificial morel soil bacterial community structure and mineral element contents in ascocarp and the cultivated soil. Can J Microbiol. 2019, 65, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Luo, D.; Mao, P.; Rosazlina, R.; Martin, F.; Xu, L. Decline in morel production upon continuous cropping is related to changes in soil mycobiome. J Fungi 2023, 9, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.Y.; Guo, H.B.; Bi, K.X.; Alekseevna, S.L.; Qi, X.J.; Yu, X.D. Determining why continuous cropping reduces the production of the morel Morchella sextelata. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 903983. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.Y.; Shen, C.; Zhang, J.H.; Wang, Y.D. Effects of continuous cropping on the physiochemical properties, pesticide residues, and microbial community in the root zone soil of Lycium barbarum. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2024, 45, 5578–5590. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Chen, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, P.; Bai, X.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, X. The comprehensive changes in soil properties are continuous cropping obstacles associated with American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) cultivation. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Yi, Z.; Qian, W.; Liu, H.; Jiang, X. Rotations improve the diversity of rhizosphere soil bacterial communities, enzyme activities and tomato yield. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0270944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Peng, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, H. The effect of Torreya grandis inter-cropping with Polygonatum sibiricum on soil microbial community. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1487619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Wang, G.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, K.; Li, S.; Jiang, J. Facilitation of bacterial adaptation to chlorothalonil-contaminated sites by horizontal transfer of the chlorothalonil hydrolytic dehalogenase gene. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011, 77, 4268–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, Z.C.; Nath, J.; Liu, X.; Ong, T.M. Induction of chromosomal aberrations by 2,4-dichloro-6-aminophenol in cultured V79 cells. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen 1996, 16, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, Z.C.; Ong, T.; Nath, J. In vitro studies on the genotoxicity of 2,4-dichloro-6-nitrophenol ammonium (DCNPA) and its major metabolite. Mutat Res. 1996, 368, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddigapu, P.R.; Minella, M.; Vione, D.; Maurino, V.; Minero, C. Modeling phototransformation reactions in surface water bodies: 2,4-dichloro-6-nitrophenol as a case study. Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Guan, Z.; Liu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, B.; Huang, L.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Han, M.; Gao, Z.; Saleem, M. Obstacles in continuous cropping: mechanisms and control measures. Adv Agron. 2023, 179, 205–256. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).