1. Introduction

Young of altricial birds are still dependent on parental cares for some time after fledging. This period, from first flight out of the nest until birds attain independence from their parents, is known as the post-fledging dependence period, which is shaped by several ecological drivers [

1] and represents the scenario of the parental-offspring conflict [

2]. For adults, the optimum length of the dependence period is that which maximizes their net lifetime reproductive success. For the offspring, however, the optimum length is that which maximizes their probability of surviving to reproductive age, even if it means a lower reproductive success for the parents [

3,

4,

5]. The development during this stage may affect subsequent survival probabilities and performance of young birds after the break-up of family ties [

6,

7,

8].

Different studies have focused on the proximal factors influencing the length of the dependence period which are related to both parental and offspring traits but also to environmental conditions, like timing of reproduction [

1,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Food availability has proved to be one of the main factors that determine the duration of the dependence as well as young decisions related to the independence onset [

1,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. According to resource competition hypothesis, siblings in better nutritional conditions will tend to monopolize resources and extend their stay in the parental territory, while subordinates will be forced to leave the territory earlier [

10,

11,

12,

13]. However, ontogeny hypotheses state that better nourished siblings can reach a better body condition which permits them to attain independence earlier than subordinates in a worse condition [

5,

15].

Avian hematology has been used in ornithological studies because it provides biological data about these animals, their biology, and the detection of possible pathological states. Determination of nutritional and physiological conditions can be very important in the understanding of ecological and behavioral issues. Hematological studies are doubtlessly very useful tools for different specialists, nevertheless, some precautions must be taken. Hematological values, including chemical components, are known to be influenced by many factors: physiological state, age, sex, nutritional condition, circadian rhythm, seasonal changes, plasma storing methods, and others [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. So when we try to study the influence of one of these factors, we must be sure that the others are controlled [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Despite the technology to analyze concentrations of blood constituents being widely available and well understood, studies of blood parameters in free-living raptors are in-creasing, but still rare [

23,

32,

33].

In this study, we analyzed the regulation of the length of the dependence period of juvenile Booted Eagles (Aquila pennata) by testing the influence of young nutritional conditions. In addition, we investigated potential correlations between hatching dates and biochemical blood parameters and body condition index (BCI). According to resource competition hypothesis, we expected longer dependence periods in nestlings with better nutritional conditions. Alternatively, under ontogeny hypothesis, we are expecting the opposite, i.e. nestlings in better nutritional conditions attaining independence earlier than subordinates in a worse condition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Species and Study Area

We studied a sample of Booted Eagles breeding in Doñana National Park, southwestern Spain (37°N, 6°30′W). The study area is about 230,000 ha and includes five main landscape types: 1) Eucalyptus

Eucaliptus spp. plantations, 2) scattered cork oak

Quercus suber with scrubland dominated by

Genista sp.,

Rosmarinus sp. and

Lentiscus sp., 3) forests of stone pines

Pinus pinea, 4) coastal sand dunes and 5) marshland. The Doñana National Park population showed density-dependent productivity across habitat heterogeneity, with higher quality territories closer to a nearby marsh border [

34,

35].

The Booted Eagle is a trans-Saharan migrant, arriving in Europe in early-March and leaving in late-September on average. Individuals display a strong philopatric behavior and low divorce rates since they usually return to the same territories that they occupied in previous years and typically breed with the same partner each year [

25,

35]. The female usually lays up to 4 eggs, which hatch after 37–40 days of incubation. The European population has been estimated at 3600–6900 pairs, most of them located in the Iberian Peninsula. Although the Booted Eagle is one of the most common birds of prey in the Mediterranean forests and woodland areas, many aspects of its biology and ecology are poorly known [

34]. In the Iberian Peninsula, Booted Eagles select areas with a mixture of woodlands and open lands, where they prey mainly on reptiles (ocellated lizard

Lacerta lepida), birds (feral pigeon

Columba livia, jay

Garrulus glandarius) and mammals (wild rabbit

Oryctolagus cunniculus) [

34]. In Europe, Booted Eagles usually nest in trees, using large platforms (built by them or by other raptor species), which are often used for many years [

35].

The Booted Eagle is a migratory, medium-size territorial raptor with marked reversed sexual dimorphism being the male the smallest sex (females around 22% heavier than males). In comparative raptor studies of siblicide and brood reduction, the Booted Eagle is considered to exhibit facultative fratricide. Pale and dark morphs occur with several intermediate plumages. In Doñana National Park, 13.8% were dark morph (own data). Juveniles are also polymorphic and very similar to adults.

2.2. Radio-Tagging and Post-Fledging Monitoring

During our study, we monitored 7 different territories, and we sexed 21 nestlings (6 in 1996, 9 in 1997 and 6 in 1999). Sample includes 9 females and 12 males. At 35-45 days old, 21 nestlings from 17 nests were equipped with battery-powered radio-transmitters (models TW-3, Biotrack Ltd., UK). Transmitters were fixed on the back of the nestlings by a harness [

36] and did not exceed a maximum of 2.5% of their body weight at fledging. Nestlings were also marked with a metal ring form the Spanish Environmental Department and a colored coded ring to be read from distance.

Observations started when young left the nest, which is defined as the time when the young was observed flying or perched on a place inaccessible from the nest, and conclude when young reached independence. Independence date was considered the first day that the young did not spent the night in the natal territory [

5]. ‘Natal’ territory was consider to be the area within a radius of 3.25 km from the nest or the hacking facilities respectively, in accordance to the mean inter-nest distance estimated for the species [

35]. During the post-fledgling period, each young was located at least every 2 days by visual contact or radio-telemetry (triangulation), using a receiver (models Stabo, GFT, Germany; and R1000, Communication Specialist Inc., USA) and a three-element Yagi directional antenna. Each nest was observed for a minimum of 6 complete days.

2.3. Blood Collection, And Body Measurements

Each spring, inside the studied area, all previously known territories were visited to record occupancy. Nest-sites were easily detected due to the conspicuous behavior of the birds. Once we suspected incubation started, we waited for 40 days (the incubation period) before climbing up to the nests to take blood samples for sexing chicks. Laying and hatching dates were estimated from the timing of nest visits and examinations of nest contents.

Total handling time of birds was less than 10 min. We measured forearm length (to the nearest mm) using a ruler. Body weight was recorded with a spring scale (to the nearest 10 g). All the measurements were taken by the same observed (M. Ferrer). The Body Condition Index (BCI) was calculated for all the nestlings’ eagles using the residuals of a regression of the cube root of mass (dependent variable) against the forearm length (independent variable) [

37]. The brachial vein of each bird was lanced with a hypodermic needle and 2 ml of blood was collected in a heparinized tube. Blood samples were taken in 35-45 days old nestlings. Blood was carefully placed into tubes containing lithium heparin to prevent coagulation, and avoiding formation of bubbles. Blood was centrifuged (10 min; 3000 rpm), and the plasma was stored at –80ºC until it was analyzed for amylase (AMY), cholesterol (CHO), creatinine (CRE), creatine kinase (CK), glucose (GLU), aspartate aminotransferase (DAT), alanine aminotransferase (AAT), total protein (PRO), urea (URE) and uric acid (UA), using a computer process-controlled multichannel Auto analyzer (Co-bas Integra 400, Roche Diagnostic). For analyses porpoise, we standardized hatching dates as difference in days between earliest record for all the years and each record. Blood samples were collected between 11:00 AM and 3:00 PM to avoid variations in blood parameters due to circadian rhythms [

23,

29].

The cellular fraction was used to sex the eagles. We used primers 2945F, cfR and 3224R to amplify the W chromosome gene following one of Ellegren´s recommendations [

38]. Analyses were carried out at Doñana Biological Station.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

We conducted Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMM) analyses to study relationship between hatching date, body condition index, and biochemical nutritional indicators. Because our study was conducted during multiple years containing nestlings potentially from the same parents, the quality of parents and/or territory, as well as the study years, might affect results. To avoid potential pseudo replication, we conducted a GLMM with length of dependence as a dependent variable and “Territory” and “Year” as random effects and “Sex”, “Relative hatching date”, “Urea”, ”Body index”, “Brood size” as fixed effects. The significance of fixed effects was assessed using Type III Wald F-tests with Satterthwaite approximation for denominator degrees of freedom.

We explored correlations among variables potentially related among them like blood-based and body index variables, with Spearman correlations. For analyses, if covariates included in the models were correlated with r > 0.70 with a Spearman correlation we did not include both parameters in the same model. That was the case with urea and uric acid (r = 0.88). We conducted a GLM with the rest of blood variables and length of dependence. We performed a multiple regression with standardized hatching dates as dependent variable and biochemistry parameters and body conditions index as independent variables. We used the STATISTICA 13.3 package (Statsoft Inc., Tulsa, USA). Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results

Young left the area of the nest, attaining independence, after a mean dependence of 41.23 ± 12.19 days (range 34-46 days, n = 21), when 94.90 ± 12.48 days old (range 77-114 days). Mean urea plasma level in nestlings was 35.85 ± 18.42 mg/dl (range 6.8-74.0 mg/dl, n = 21). Non-significant differences were found in duration of dependence period between broods with one or two chicks (one-chick 36.22 ± 8.9 days, range 29-43 days, n=9; two-chicks 45.00 ± 13.28 days, range 33-47 days, ANOVA, F=2.925, p=0.138) nor between sexes (males 40.6 ± 11.20 days; female 42.0 ± 14.08 days, ANOVA, F=0.061, p=0.875), being the longest dependent period the one for the two chicks-broods with two females (2-females 52.50 ± 12.50 days) and the shortest for the one-chick male (1-male 33.60 ± 8.9 days), but again non-significant.

3.1. The Regulation of the Dependence Period Length

Only blood urea levels was strongly related with the length of the dependence period (p=0.000164). We did not found any significant effect of hatching date or body index in the length of the dependence period. Neither brood size, sex nor territory or year showed significant effects on the length of the dependence period (

Table 1). The fact that neither “Territory” nor “Year” or “Sex” had any significant effect on the analysis does no support a potential pseudo replication. No blood related variables, but urea, showed significant relationship with the length of the dependence (

Table 2).

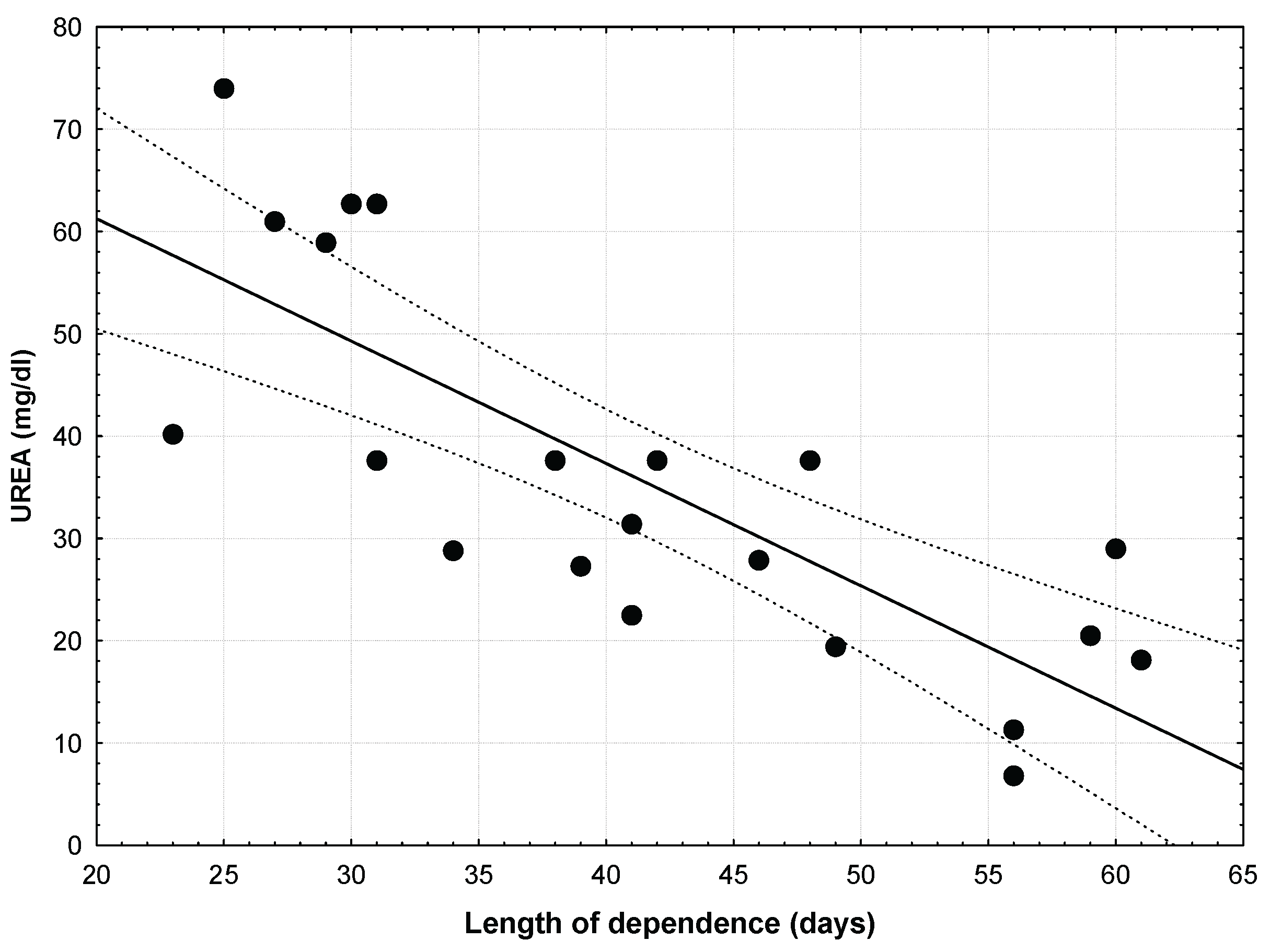

Considering only urea concentration in blood, 62% of the variance in the length of the post fledgling period was explained for urea level alone (

Figure 1), with better nourished young (lower urea levels) having longer period under parental cares (r = -0,7920; p = 0,00002; r2 = 0,6273).

Figure 1.

Considering only Urea concentration in blood, 62% of the variance in the length of the post fledgling period was explained for urea level alone, with better nourished young (lower urea levels) having longer period under parental cares (r = -0,7920; p = 0,00002; r2 = 0,6273).

Figure 1.

Considering only Urea concentration in blood, 62% of the variance in the length of the post fledgling period was explained for urea level alone, with better nourished young (lower urea levels) having longer period under parental cares (r = -0,7920; p = 0,00002; r2 = 0,6273).

3.1.1. First Phase of Dependence Period

We define the first phase of the dependence period as the time starting when chicks leaving the nest and ends with the first soaring flight. Young started to made soaring flight after a mean of 13.9 ± 6.08 days (range 2-25 days, n = 21) after their first flight, when 67.5 ± 5.79 days old (range 58-79 days). Non-significant differences were found in duration of the first phase of the dependence period between broods with one or two chicks (ANOVA, F=0.627, p=0.438) nor between sexes (ANOVA, F=0.276, p=0.605).

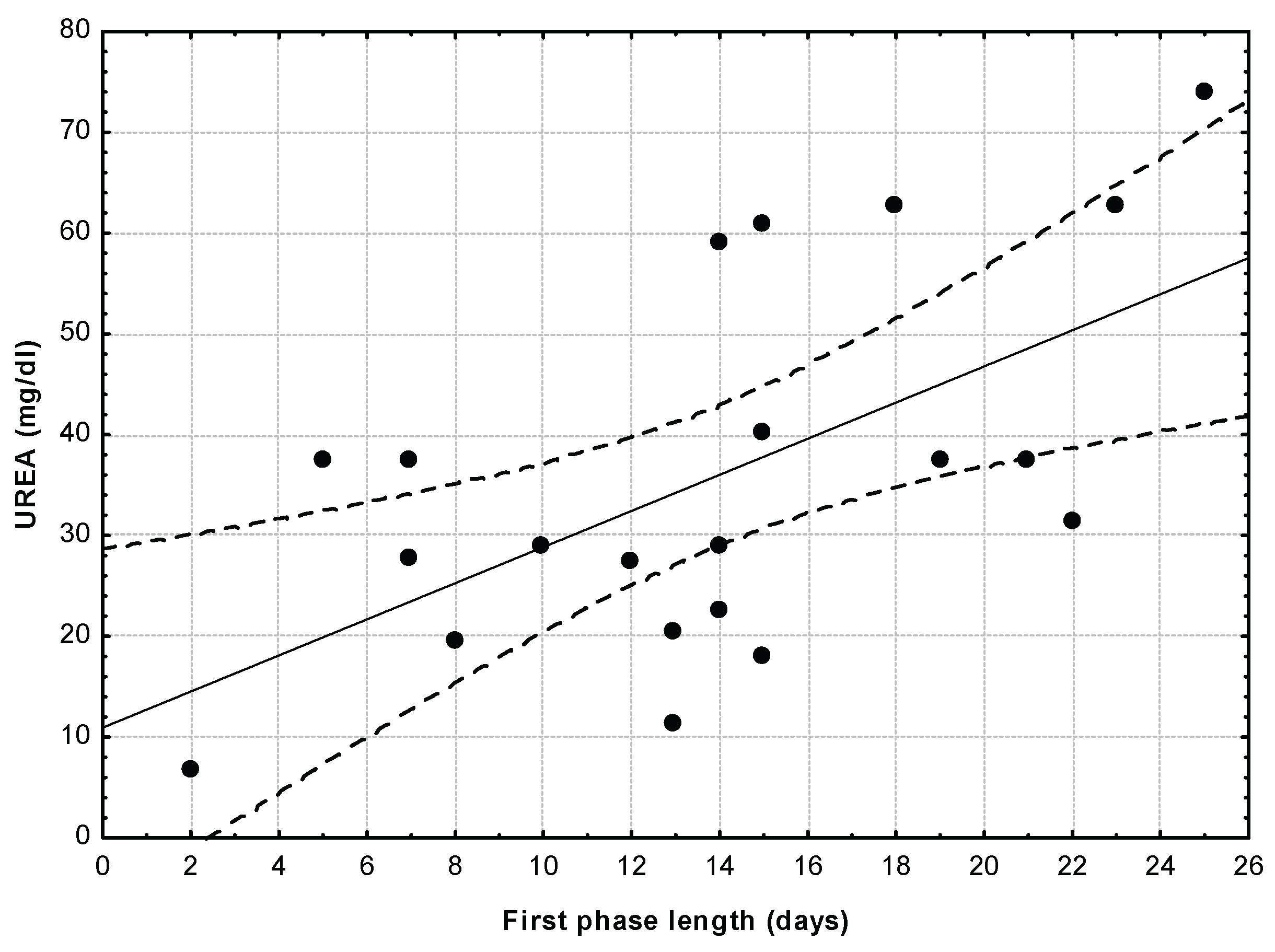

Urea blood levels of nestlings were significantly related to the length of the first phase of the dependence period, starting from the time when chicks leave the nest to the first soaring flight. (

Figure 2; r = 0.591; p = 0.0048; r2 = 0.3497), with those young eagles soaring earlier for the first time being those with better nutritional conditions.

Figure 2.

Also urea blood levels of nestlings were significantly related to the length of the first phase of the dependence period, starting from the time when chicks leave the nest to the first soaring flight. (r = 0.591; p = 0.0048; r2 = 0.3497), with those young eagles soaring earlier for the first time being those with better nutritional conditions.

Figure 2.

Also urea blood levels of nestlings were significantly related to the length of the first phase of the dependence period, starting from the time when chicks leave the nest to the first soaring flight. (r = 0.591; p = 0.0048; r2 = 0.3497), with those young eagles soaring earlier for the first time being those with better nutritional conditions.

3.1.2. Second Phase of Dependence Period

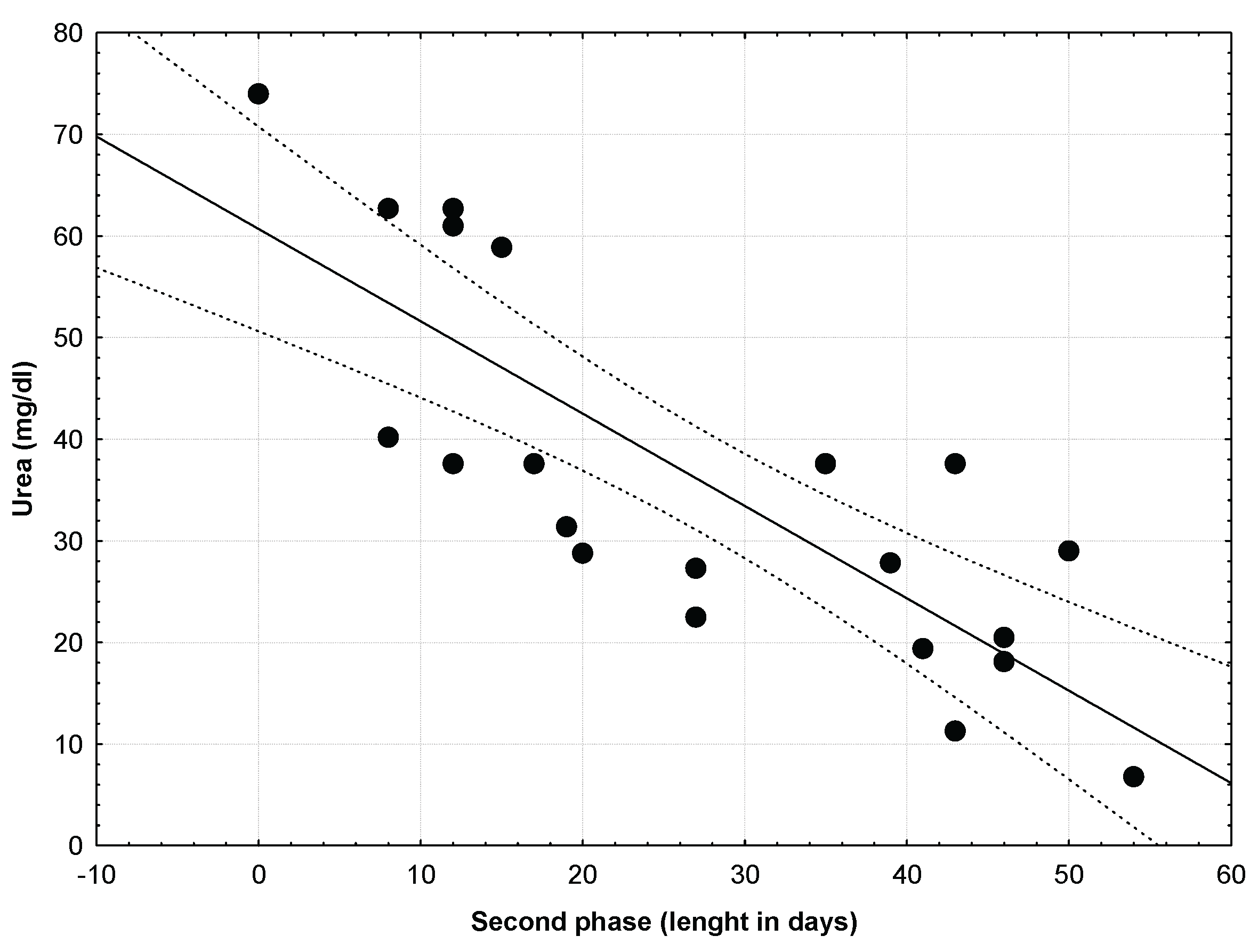

We define the second phase of the dependence period as the time from the first soaring flight to the date of independence. Young attained independence after a mean of 27.3 ± 16.39 days (range 1-54 days, n = 21) after their first soaring flight, when they were 94.90 ± 12.48 days old (range 577-114 days old). Non-significant differences were found in duration of the second phase of the dependence period between broods with one or two chicks (ANOVA, F=0.931, p=0.347) nor between sexes (ANOVA, F=0.423, p=0.523). Urea levels were significant and negatively related with the duration of this second phase (

Figure 3; r = -0.808; p = 0.00001; r2 = 0.653), with those young eagles attained independence later being those with better nutritional conditions.

Figure 3.

In the second phase of the dependence period (from the first soaring flight to the date of independence), also urea levels were significant and negatively related with the duration of this second phase (r = -0.808; p = 0.00001; r2 = 0.653), with those young eagles attained independence later being those with better nutritional conditions.

Figure 3.

In the second phase of the dependence period (from the first soaring flight to the date of independence), also urea levels were significant and negatively related with the duration of this second phase (r = -0.808; p = 0.00001; r2 = 0.653), with those young eagles attained independence later being those with better nutritional conditions.

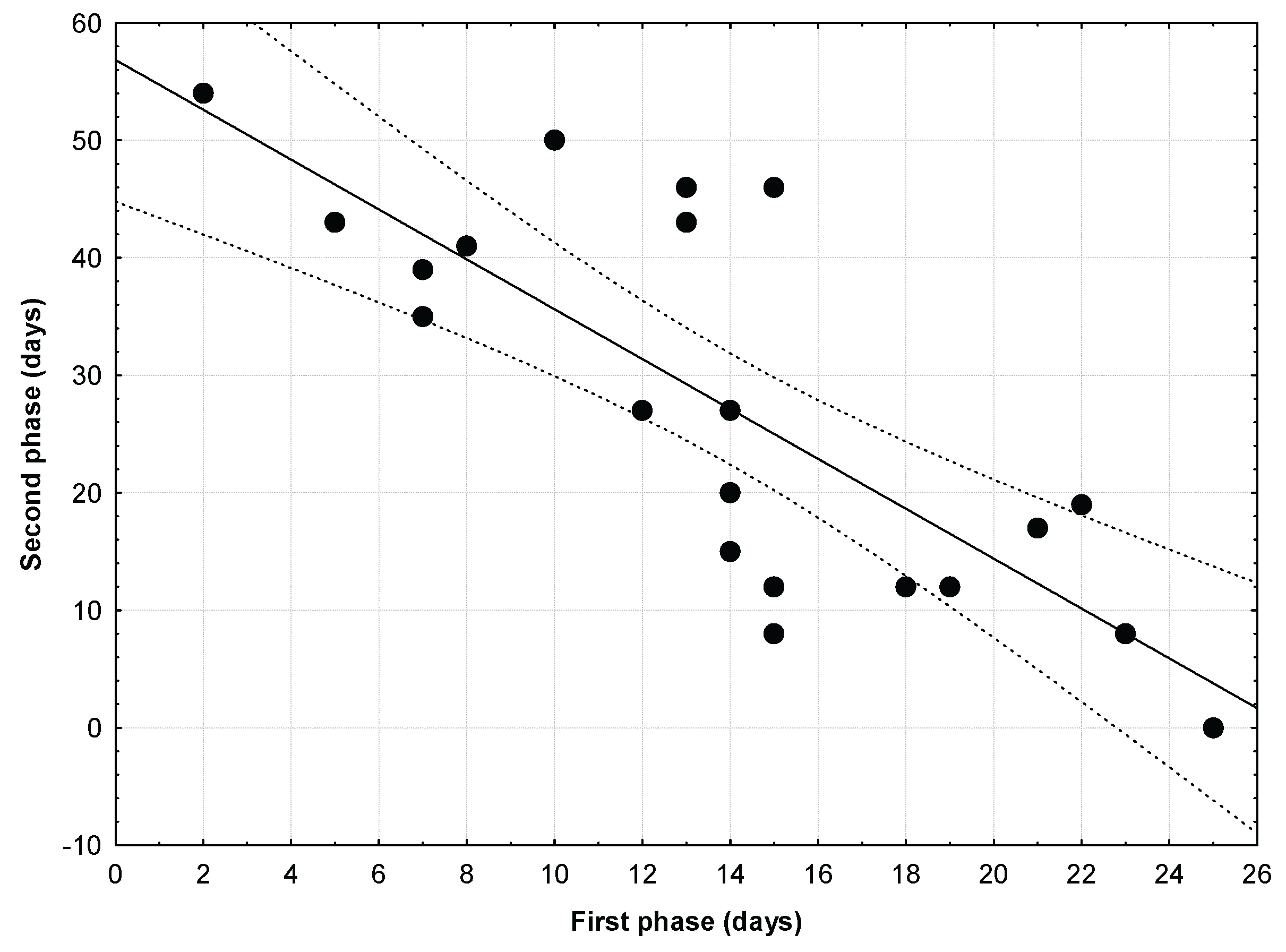

A highly significant and negative relationship between the length in days of the two phases of the dependent period (First phase: from the abandonment of the nest to the first soaring flight: mean = 13.9

+ 6.08; Second phase: from the first soaring flight to the date of independence: mean = 27.33

+ 16.39) was found (

Figure 4; r = .0.787; p = 0.00002; r2 = 0.619), with those young eagles soaring younger being those whose attained the independence latter (t-student for dependent samples t= -2.860, p=0.009).

Figure 4.

A highly significant and negative relationship between the length in days of the two phases of the dependent period (First phase: from the abandonment of the nest to the first soaring flight; Second phase: from the first soaring flight to the date of independence) was found (r = .0.787; p = 0.00002; r2 = 0.619), with those young eagles soaring younger being those whose attained the independence latter.

Figure 4.

A highly significant and negative relationship between the length in days of the two phases of the dependent period (First phase: from the abandonment of the nest to the first soaring flight; Second phase: from the first soaring flight to the date of independence) was found (r = .0.787; p = 0.00002; r2 = 0.619), with those young eagles soaring younger being those whose attained the independence latter.

3.2. Hatching Date and Nutritional Conditions

It has been frequently demonstrated differences between BCI and plasma biochemistry as indicators of nutritional condition [

10,

12,

17,

32,

33]. In

Table 2 results of multiple regression are shown, demonstrating that only urea concentration was correlated to hatching dates, showing worse condition for chicks that hatched later in the breeding season. Only urea was selected in a multivariate regression, showing a stronger correlation. Urea levels suggest that nestlings hatched later in the season will be in poorer nutritional condition.

4. Discussion

No blood related variables, but urea, showed significant relationship with the length of the dependence period, with better nourished young (lower urea levels) having longer period under parental cares. We did not found any significant effect of hatching date or body condition index in the length of the dependence period. Neither brood size, sex, year nor territory showed significant effects on the length of the dependence period.

Results obtained in this study support the view that the dependence period is in fact composed of two different phases controlled by different factors: 1) the first phase of the dependence period, starting from the time when chicks leave the nest to the first soaring flight, and 2) a second phase, from the first soaring flight to the date of independence.

Urea blood levels of nestlings were significantly and positively related to the length of the first phase, with those young eagles soaring earlier for the first time being those with better nutritional conditions. Also urea levels were significant but negatively related with the duration of the second phase, with those young eagles attained independence later being those with better nutritional conditions (lower urea levels). A highly significant and negative relationship between the lengths in days of the two phases of the dependent was found, with those young eagles soaring younger being those attaining the independence latter.

A wide variety of birds fast and exhibit a decrease in body mass during certain stages of their annual life cycles [

18,

41,

42]. Birds fast when food is scarce but also when it is plentiful if they are engaged in other important activities that compete with feeding, such as incubation, molting, and migration. In the wild, many avian species undergo intermittent periods of food deprivation. Fluctuations in food availability may impose fasting for more or less predictable periods of time. Fasting endurance may have an adaptive value. Despite the importance of fasting capacity in the life history of many species of birds, little is known about the metabolic responses to food deprivation. This contrasts with the large number of studies dealing with feeding ecology. Physiological responses to fasting have been studied in common eiders, domestic geese, herring gulls, chickens, common buzzards , king penguins, emperor penguins, and greater snow geese, among other species [

5,

6,

9,

10,

16,

43,

44].

Three phases have been described associated with changes in the relative rate of mass loss, and the nature and quantity of fuel oxidized in geese. During phase I in the fasting period, the daily rate of mass loss and the resting metabolic rate decrease progressively. Urea concentration in the blood also decrease during phase I, reflecting a progressive reduction of proteolysis, and a beta hydroxybutyrate concentration increase as a result of an increase in fat mobilization. Phase II is the longest period during which the rates of mass loss and metabolism remain low and fat becomes the main fuel. Urea concentration is low and ketone bodies concentration in blood increase during this period. This permits the conservation of body proteins, which have vital structural and regulator roles. Phase III correspond to a critical period where body proteins are metabolized and urea concentration increase dramatically. Beta-hydroxybutyrate levels in blood decrease and the rate of mass loss increases. Changes in certain blood parameters are indicative of the type of energy sources used during the three phases described for prolonged fasting. Beta-hydroxybutyrate is one of the ketone bodies produced after partial oxidation of the fatty acids resulting from triglyceride hydrolysis, so its concentration is related to the lipid catabolism [

46,

47,

48]. Urea concentration is an indicative of protein catabolism.

All the articles published by many authors show a continuous and lineal increase of nitrogenized residues that occurs as soon as the protein catabolism starts. The time a bird keeps in using up its fat reserves and the moment it starts using its own muscle tissues as an energy source basically varies according to the individual's initial condition and the species’ capacity for storing fat reserves. The emperor penguin, which shows an extreme example of fat storage capacity, can subsist for two months on its own fat reserves before beginning to use its own proteins. At the moment the protein catabolism is activated, the increase of urea levels in the blood is continuous and constant. In raptors, as already shown for several species, including the Spanish Imperial Eagle,

Aguila adalberti, the protein catabolism activation occurs very quickly given the characteristic poor fat storage capacity of this group, a very common feature in flying birds. Even in smaller Antarctic penguin, as with the Chinstrap Penguin, the protein catabolism activation starts on the 5 day of fasting [

39].

Urea levels in blood increase with fasting and decrease slowly with refeeding, therefore being good indicator of nutritional conditions in species of birds with poor fat reserves as raptors. Urea levels in blood have been used as index of body condition in raptors [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

29,

33,

35,

42]. Urea levels increase as a response to starvation and decrease after refeeding because proteins are actively mobilized as energy source, increasing the nitrogenous excretion components released into the blood [

39,

40]. Urea is not sensitive to recent ingest (in contrast to glucose concentration for example), and increase and decrease in blood con-centration are slow [

40]. All of the monitored wild nestlings survived to fledging. Sub-lethal effects of poor condition can still have profound impacts on individual fitness, especially as it relates to migration [

45]. Booted Eagles in Western Europe undertake a seasonal migration to over-winter in Africa. Migration is energetically demanding and juveniles that hatch later in the breeding season may be at a disadvantage if they depart with in poor nutritional condition.

Plasma urea concentration is and index of protein catabolism. Urea is a minor pathway for protein degradation in birds, but the activity of liver arginase (the enzyme on which urea production in birds depends) has increased after a prolonged fast, and also the rise of urea during protein catabolism may be explained by a greater arginine availability. The time a bird keeps in using up its fat reserves and the moment it starts using its own muscle tissues as an energy source basically varies according to the individual’s initial condition and the species’ capacity for storing fat reserves.

Summarizing, our results support the idea of nutritional conditions determining the length of dependence period. Thus, the dependence period consist of two separate phases, each representing roughly half of the total period, so variations occurring in either phase affects the overall length. Parental choice of weather to prolong or reduce the dependence period is limited to the stage when the young have already become skilled in flight. To stimulate independence in young eagles when they are still unable to make soaring flights makes no sense. So, the total length of the dependence period is determined, in addition to any parental decision, by the nutritional condition of the young, which determines the age when the first soaring flight occurs, and the total length of the dependence period. These results are in accordance with other studies in raptors [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

10,

11,

22,

23,

32,

33] showing the influence of nestlings nutritional conditions in the dependence period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F. and V.M.; methodology, M.F.; software, M.F.; validation, M.F., V.M., J. G.; formal analysis, M.F. JG.; investigation, M.F.;V.N.; resources, M.F.; data curation, V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.; writing—review and editing, V.M. and J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Ethics Approval Statement

Procedures used in this study comply with the current laws, guidelines and regulations for working on the Doñana National Park. Permits to work in the study area and to conduct the experiments were granted by the Andalusian Environmental Government, and all experimental protocols were approved. All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy, and legal or ethical reasons).

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to EBD-CSIC fieldworkers who have monitored Booted Eagle population in Doñana National Park for more 20 years and, especially to L. Garcia, J. Cuesta and E. Casado. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gallego-García, D.; Sarasola, J.H. Ecological drivers of variation in the extent of the post-fledging dependence period in the largest group of diurnal raptors. Ibis 2025, 167, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivers, R.L. 1972. Parental investment and sexual selection. Pages 136-179 -in D. Campbell, editor. Sexual selection and the descent of man. Aldine, Chicago, Illinois.

- Clutton-Brock, T.H. (1991). The evolution of parental care. Princeton, University Press, Princeton.

- Bustamante, J. Post-fledging dependence period and development of flight and hunting behaviour in the Red Kite Milvus milvus. Bird Study 1993, 40, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M. Regulation of the period of post-fledging dependence in the Spanish Imperial Eagle Aquila adalberti. Ibis 1992, 134, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M. Juvenile dispersal behaviour and natal philopatry of a long lived raptor, the Spanish Imperial Eagle Aquila adalberti. Ibis 1993, 135, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutullo, A.; Urios, V.; Ferrer, M.; Peñarrubia, S. G. Post-fledging behaviour in golden eagles Aquila chrysaetos: Onset of juvenile dispersal and progressive distancing from the nest. Ibis 2006, 148, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penteriani, V.; Delgado, M. M.; Maggio, C.; Aradis, A.; Sergio, F. Development of chicks and predispersal beaviour of young in the eagle owl Bubo bubo. Ibis 2004, 147, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, I. 1979. Population ecology of raptors. T. and A. D. Poyser.

- Muriel, R.; Ferrer, M.; Balbontín, J.; Cabrera, L.; Calabuig, C. P. Disentangling the effect of parental care, food supply, and offspring decisions on the duration of the post fledging period. Behav. Ecol. 2015, 26, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, B.E.; De Cornulier, T.; Bretagnolle, V. Parental investment and parent-offspring conflicts during the post-fledging period in Montagu’s Harrier. Animal Behaviour 2002, 63, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbontín, J.; Ferrer, M. Factors affecting the length of the post-fledging period in the Bonelli’s Eagle Hieraaetus fasciatus. Ardea 2005, 93, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, B.G., Jr. Dispersal in vertebrates. Ecology 1967, 48, 975–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naef-Daenzer, B.; Widmer, F.; Nuber, M. Differential postfledging survival of great and coal tits in relation to their condition and fledging date. Journal of Animal Ecology 2001, 70, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holekamp, K.E. Proximal causes of natal dispersal in Belding’s Ground Squirrel (Spermophilus beldingi). Ecological Monographs 1986, 56, 365–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Belliure, J.; Viñuela, J.; Martin, B. Parental physiological condition and reproductive success in chinstrap penguins (Pygoscelis antarctica). Polar Biology 2013, 36, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Morandini, V. Better nutritional condition changes the distribution of juvenile dispersal distances: An experiment with Spanish imperial eagles. Journal of Avian Biology 2017, 48, 1342–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandini, V.; Ferrer, M.; Perry, L.; Bechard, M. Sex determination by morphological measurements of young Rockhopper Penguins (Eudyptes chrysocome) during the crèche phase. Waterbirds 2018, 41, 434–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandini VFerrer, M. Physiological condition determines behavioral response of nestling Black-browed Albatrosses to a shy-bold continuum test. Ethology, Ecology and Evolution 2019, 31, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasch, J.; Musquera, S.; Palacios, L.; Jimenez, M.; Palomeque, J. Comparative haematology of some falconiforms. Condor 1976, 78, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbontin, J.; Ferrer, M. Plasma chemistry reference values in free- living Bonelli’s Eagle (Hieraaetus fasciatus) nestlings. J Raptor Res 2002, 36, 231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Balbontin, J.; Ferrer, M. Condition of large brood in Bonelli’s Eagle Hieraaetus fasciatus. Bird Study 2005, 52, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumbusch, R.; Morandini, V.; Urios, V.; Ferrer, M. Blood plasma biochemistry and the effects of age, sex, and captivity in Short toed Snake Eagles (Circaetus gallicus). J Ornithol 2021, 162, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman, W.W.; Stickle, J.E.; Giesy, J.P. Hematology and serum chemistries of nestling bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) in the lower peninsula of MI, USA. Chemosphere 2000, 41, 1575–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casado, E.; Balbontin, J.; Ferrer, M. Plasma chemistry in Booted Eagles (Hieraaetus pennatus) during breeding season. Comp Biochem Physiol A 2002, 131, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobado-Berrios, P.; Ferrer, M. Age-related changes of plasma alkaline phosphatase and inorganic phosphorus, and late ossification of the cranial roof in the Spanish imperial eagle (Aquila adalberti). Physiol Zool 1997, 70, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dujowich, M.; Mazet, J.K.; Zuba, J.R. Hematologic and biochemical reference intervals for captive California condors (Gymnogyps californianus). J Zoo Wildl Med 2005, 36, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.J.; Wilson, J.D.; Amar, A.; Douse, A.; MacLennan, A.; Ratcliffe, N.; Whitfield, D.P. Growth and demography of a re-introduced population of White-tailed Eagles Haliaeetus albicilla. Ibis 2009, 151, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M. Haematological studies in birds. Condor 1990, 92, 1085–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, F.J.; Celdrán, J.F.; Peinado, V.I.; Viscor, G.; Palomeque, J. Hematological values for four species of birds of prey. Condor 1992, 94, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo FJ (1995) Estudio Bioquímico y Enzimático del Plasma de Aves en Cautividad. Ph.D. thesis. University of Barcelona. 381 pp.

- Ferrer, M.; Evans, R.; Hedley, J.; Hollamby, S.; Meredith, A.; Morandini, V.; Selly, O.; Smith, C.; Whitfield, P. Plasma chemistry and hematology reference values in wild nestlings of White-tailed Sea Eagles (Haliaetus albicilla): Effects of age, sex and hatching date. Journal of Ornithology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Evans, R.; Hedley, J.; Hollamby, S.; Meredith, A.; Morandini, V.; Selly, O.; Smith, C.; Whitfield, P. Hacking Techniques Improve Health and Nutritional Status of Nestling White-tailed Eagles. Ecology and Evolution 2023, 13, e9776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, S.; Balbontin, J.; Ferrer, M. Nesting habitat selection by Booted Eagles Hieraeetus pennatus and implications for management. Journal of Applied Ecology 2000, 37, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado, E.; Seoane, S.S.; Lamelin, J.; Ferrer, M. The regulation of brood reduction in Booted Eagles Hieraaetus pennatus through habitat heterogeneity. Ibis 2008, 150, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenward, R.E. (2000). A manual for wildlife radio tagging. Academic press.

- Ferrer, M.; Morandini, V.; Perry, L.; Bechard, M. Factors affecting plasma chemistry values of the black-browed albatross Thalassarche melanophrys. Polar Biology 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.; Double, M.C.; Orr, K.; Dawson, R.J. A DNA test to sex most birds. Mol Ecol 1998, 7, 1071–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Alvarez, C.; Ferrer, M.; Viñuela, J.; Amat, J.A. Plasma chemistry of Chinstrap Penguin Pygoscelis antarctica during fasting periods: A case of poor adaptation to food deprivation? Polar Biol 2003, 26, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodriguez, T.; Ferrer, M.; Carrillo, J.C.; Castroviejo, J. Metabolic responses of Buteo buteo to long-term fasting and refeeding. Comp Biochem Physiol A 1987, 87, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De le Court, C.; Aguilera, E.; Recio, F. Plasma chemistry values of free-living White Spoonbills (Platalea leucorodia). Comp Biochem Physiol A 1995, 112, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumbusch, R.; Morandini, V.; Urios, V.; Ferrer, M. Blood plasma biochemistry and the effects of age, sex, and captivity in Short-toed Snake Eagles (Circaetus gallicus). Journal of Ornithology, 2021, 162, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.J. Mass/Length Residuals: Measures of body condition or generators of spurious results? Ecology 2001, 82, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labocha, M.K.; Hayes, J.P. Morphometric indices of body condition in birds: A review. J Ornithol 2012, 153, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, P.P.; Studds, C.E.; Wilson, S.; et al. Non-breeding season habitat quality mediates the strength of density-dependence for a migratory bird. Proc R Soc B 2015, 282, 20150624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriel, R.; Schmidt, D.; Calabuig, C.; Patino-Martinez, J.; Ferrer, M. Factors affecting plasma biochemistry parameters and physical condition of Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) nestlings. J Ornithol 2013, 154, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemonde, A. Urea production in chick liver slices. Can J Biochem Physiol 1959, 37, 1187–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griminger, P.; Scanes, C.G. (1986) In: Sturkie PD (ed) Avian physiology. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 326–344.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).