1. Introduction

Seahorses, like other small marine fish species, are an integral part of marine biodiversity and ecosystem function [

1]. As recognized flagship species [

2], their study and the resulting conclusions can be considered representative of their entire ecosystem, providing guidelines for the creation of conservation and management programs for those ecosystems. Seahorses are considered as such due to their unique life history, characterized by sparse distribution, low mobility, site fidelity, small home ranges, low fecundity, mate fidelity, and lengthy parental care for small broods. These traits may render them vulnerable to overfishing and environmental disruptions, including habitat damage and degradation [

1]. Additionally, seahorses inhabit shallow, coastal areas worldwide, where anthropogenic disturbances tend to be most frequent and severe [

3]. These constraints help explain why 2 seahorse species are listed as “Endangered,” 12 as “Vulnerable,” and 1 as “Near Threatened” on the 2024 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, with only 10 listed as “Least Concern” and 17 still as “Data Deficient.” This reflects substantial gaps in knowledge, even for a heavily exploited fish group like seahorses.

The only two European seahorse species,

Hippocampus guttulatus and

H.

hippocampus, which inhabit the ria Formosa (southern Portugal), are no different. The populations of these two species suffered a dramatic decrease (a 90% reduction in abundance from 2001 to 2009) due to unknown causes [

4]. Local anthropogenic disturbances were mentioned as causes for population decline and habitat degradation, but they do not fully explain the current situation. Later, a small population increase was observed [

5], but a massive decrease in the population was again observed between 2015 and 2021, bringing the abundance levels to values lower than those mentioned by [

4] (Palma, unpublished data). The causes for population decline were directly related to anthropogenic disturbances but do not fully explain it, and the effect of climate change must be regarded as an additional stressor. Combined, these drivers of change have a major impact on these seahorse populations, which, due to their sensitive life history, may become powerless to cope with these impacts. Therefore, well-designed conservation plans are urgently needed to preserve the biodiversity of this ecosystem.

Sensitivity to regional climatic conditions and anthropogenic disturbances interact to strongly affect habitat loss and fragmentation [

6], threatening biodiversity, decreasing dispersal rates, and increasing population mortality [

7]. Climate change negatively impacts inshore marine habitats and their fauna, including seahorses, through changes in temperature, ultraviolet radiation (UVR), rainfall patterns, community composition, the status of coastal habitats, and storm activity [

8]. These changes are likely to be more severe in enclosed waters, where local warming occurs [

9]. According to NOAA Daily Sea Surface Temperature Analysis data, over the past 30 years, there has been a significant increase in coastal sea surface temperatures (°C/decade) throughout most of the Iberian Peninsula and the North African Atlantic coast (avg=0.214°C). Despite the unpredictability of climate systems, forecasts indicate a global mean temperature rise of 2°C by 2100 [

10]. Heat waves, which currently last for 1–2 weeks along the Portuguese coast [

11], are expected to become more intense, more frequent, and of longer duration in warmer climate scenarios [

12].

The ria Formosa is a mesotidal, shallow coastal lagoon prone to extreme daily and seasonal temperature variations [

13] and UVR exposure [

14]. These conditions are expected to become more frequent and severe under the current climate change scenario. Previous data [

15] showed a direct relationship between seawater temperature and seahorse habitat use. In some surveyed locations, seahorse abundance decreased during high temperature peaks (25°C), whereas in locations with lower temperatures (20°C), the abundance remained more stable. It was also observed that in locations with equal habitat complexity, seahorse abundance was always lower at higher temperatures. This population shift coincided with the breeding season. Since temperature can influence gonad development and the survival of larvae, post-settlement juveniles, and adults in many species [

4], seahorses may be more susceptible to temperature fluctuations and unable to cope due to their life history and specific habitat requirements.

The present study aims to improve our knowledge on this issue by gathering information to define the temperature effects on the growth, reproduction, and survival of these species, as well as the fish metabolic response to different temperature scenarios.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Adult Growth and Reproduction

This trial lasted for seven months, starting two months prior (March) to the expected start of the breeding season and ending in September. At the beginning of the experiment, 64 adult F4 generation H. guttulatus (32 males, 32 females) were selected and stocked in each of 4 units of 250-liter white plastic flat-bottom rectangular tanks (one tank per treatment) at 16 animals (8 males, 8 females) per tank. The tanks were assembled in two semi-closed systems, with a constant water flow (≈50 l h-1) and moderate aeration. Temperature was controlled as follows: one tank system was connected to a chiller, and through different water inflows to the tanks the water temperature was controlled at 16±1.2°C and 20±1.5°C in each of the two tanks. In the second tank system, water was heated and controlled at 24±1.2°C and 28±1°C in each of the two tanks. Salinity was not controlled and followed the natural seasonal pattern. Tanks were illuminated from above with 2×36W fluorescent tubes, with an intensity of 600±25 lux at the water surface, and a photoperiod controlled by a timer. The photoperiod was adjusted every two weeks to match the natural photoperiod. Water quality parameters (ammonia, nitrates, and nitrites) were recorded twice a week and kept stable throughout the experiment; ammonia values were always below detectable levels, nitrate <0.3 mg l-1, and nitrite <1.25 mg l-1.

During the experiment, seahorses were fed ad libitum once daily at 10:00 a.m. with the same dietary treatment, composed of two live mysid species, Mesopodopsis slabberi and Diamysis lagunaris, in slightly different proportions depending on the season. As the prey were supplied live, seahorses could feed on demand, which justified the single daily feeding. Each day, uneaten food and feces were removed from the tanks by siphoning every morning before feeding. All adult fish were sampled for length and weight at the start and end of the trial. During the experiment, seahorses were allowed to mate and reproduce freely. When broods occurred, juvenile seahorses from each brood were gently collected from the broodstock tanks with a beaker and counted.

2.2. Juvenile Growth

When broods started to occur and consequent juvenile parturition took place, 180 juveniles from the same brood were collected and randomly assembled into the rearing tanks. The juvenile growth trial was conducted according to a completely randomized design, with three replicate tanks assigned per temperature. Fifteen juvenile

H.

guttulatus were stocked in each of three replicate 10-liter glass rectangular tanks at a density of 1.5 fish per liter. In each tank, the lateral and back walls were covered with black adhesive to improve prey detection [

16]. The front wall was left uncovered for any necessary observation. Husbandry conditions and the experimental design used in this experiment were the same as described by [

17], except for temperature control. Rearing tanks were assembled in semi-closed systems to allow temperature control for each set of three replicate tanks. Four different temperatures (the same tested for adult seahorses) were tested: 16±0.8°C, 20±0.8°C, 24±1°C, and 28±0.9°C. Salinity and dissolved oxygen were kept, respectively, at 37.2 ± 0.2‰ and 7.3 ± 0.2 mg/l. Tanks were illuminated from above with two 36 W fluorescent tubes, with a light intensity of 900 ± 40 lux at the water surface and a photoperiod controlled by a timer at 16L:8D (06:00-22:00 h). Seawater quality data (ammonia, nitrates, and nitrites) were recorded biweekly. Values remained stable throughout the experiment; ammonia values were always below detectable levels, nitrate <0.3 mg/l, and nitrite <1.25 mg/l.

The juvenile grow-out trial lasted for 56 days, from 0-56 days post-parturition (DPP), during which juvenile seahorses were fed ad libitum with live copepods (Oithona nana). Juveniles were sampled every 14 days until the end of the experiment (56 DPP). The data was used to calculate: 1) Weight gain (WG, mg d-1) = (Wf - Wi) / d, where Wf is the final seahorse wet weight (mg), Wi is the initial wet weight (mg), and d is the number of days; 2) Growth rate expressed as thermal-unit growth coefficient (TGC) per fish in each tank, TGC = [(Wf(1/3) − Wi(1/3)) / Σ(T × d)] × 100, where Wf, Wi, and d, are as described above, and T is the water temperature; and 3) Condition factor (CF) = (wet weight (g) / length (cm)³) × 100.

2.3. Respirometry - Experimental Procedures

Seahorse oxygen consumption was determined at two different life stages: juveniles with 1, 14, and 28 DPP, and adults (12 months old). Oxygen consumption was measured by flow-through respirometry following an adapted protocol defined by [

18]. In brief, before transfer to the respiratory chambers, fish were fed

ad libitum; mealtime started at 10:30 h, and fish fed for 45 minutes (group n=12). Measurements started immediately after transfer (11:00 h) and continued for 22 hours, with 8 hours in the light and 14 hours in the dark. To keep the stress level of the fish at a minimum, they were not disturbed during the respirometry measurements. The body weight of each individual was determined immediately after removal from the chamber. The flow-through respirometry system consisted of six individual metabolic chambers (2.3 L capacity). Each fish was individually placed in a metabolic chamber. Since housing in respirometry chambers may induce stress responses [

19,

20], measurements taken during the first 3 hours of the light period were discarded. The water inlet was always at oxygen saturation level, while the oxygen concentration at the outlet was measured by a polarographic microelectrode model 8–730 (Microelectrodes Inc., USA). Measurements were controlled by a PC using Oxilogger 2009 software.

The oxygen saturation level was maintained in the water reservoir, and a peristaltic pump (ISMATEC, model ISM920A, Switzerland) controlled the water flow in the chambers using Tygon® tubing (480-μm inner diameter). Each respirometry run consisted of sequential measurements from all the chambers. The magnetic valves controlled by the Oxilogger 2009 software determined in which chamber the oxygen consumption was being measured. At the start of each cycle, the oxygen dissolved in water was measured for 30 seconds to calibrate the software, followed by a 120-second washing step of seawater from the next chamber before starting the next measurement period (30 seconds). This step was always performed before and after the measurement in each chamber. Six oxygen consumption measurements were registered over a 30-second period (5 seconds each). A complete measurement cycle was done in 18 minutes, comprising the oxygen probe calibration, a washing step, dissolved oxygen measurement in the water chamber, another washing step, and so forth in each of the six chambers in sequence. The water temperature in the outlet water of each chamber was measured with a temperature probe, and oxygen calibration was performed each time a measurement run started.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0. Differences in juvenile seahorse length, wet weight, CF, TGC, and FCR were tested using nested ANOVA with post hoc Newman–Keuls (NK) multiple comparison test (P=0.05). For the respirometry analysis, data was expressed as mean ± SD of three runs of respirometry data, and statistical analysis was performed based on the average of the three runs per fish. A paired t-test was used to compare the oxygen consumption between the light and dark phases. Linear regression was used for curve adjustment, and the slopes of the regression equations were compared by analysis of covariance. Significance levels were set at P<0.05.

3. Results

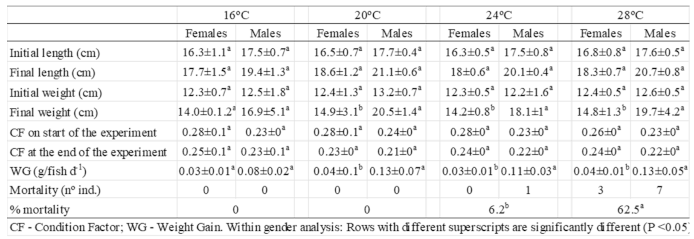

3.1. Adult Seahorse Growth and Breeding Performance

Throughout the experimental trial (seven-month period), adult seahorses increased in both length and weight (

Table 1). Growth parameters were proportionally higher in males than in females, irrespective of the rearing temperature. Significantly higher growth rates (p<0.05) were observed in fish reared at 20 and 24°C compared to those reared at 16 and 28°C, resulting in a higher WG for fish reared at the intermediate temperatures (

Table 1). Conversely, in all temperature treatments, both genders decreased their CF during the experiment.

Adult mortality varied significantly at the four tested temperatures. No mortality was observed at 16 and 20°C, but with increasing temperatures, the mortality rate increased from 6.2% (one fish) at 24°C to 62.5% (10 fish) at 28°C.

Regarding reproductive performance, no reproductive activity (including courtship behavior) was observed in seahorses kept at 16°C. At 28°C, only sporadic courtship behavior was observed, with no successful broods resulting from it. Conversely, seahorses kept at 20 and 24°C produced 20 and 16 successful broods, respectively (2.5 and 2 successful broods per couple). The number of juveniles per brood decreased significantly (p<0.05), from 410±133 at 20°C to 257±157 at 24°C.

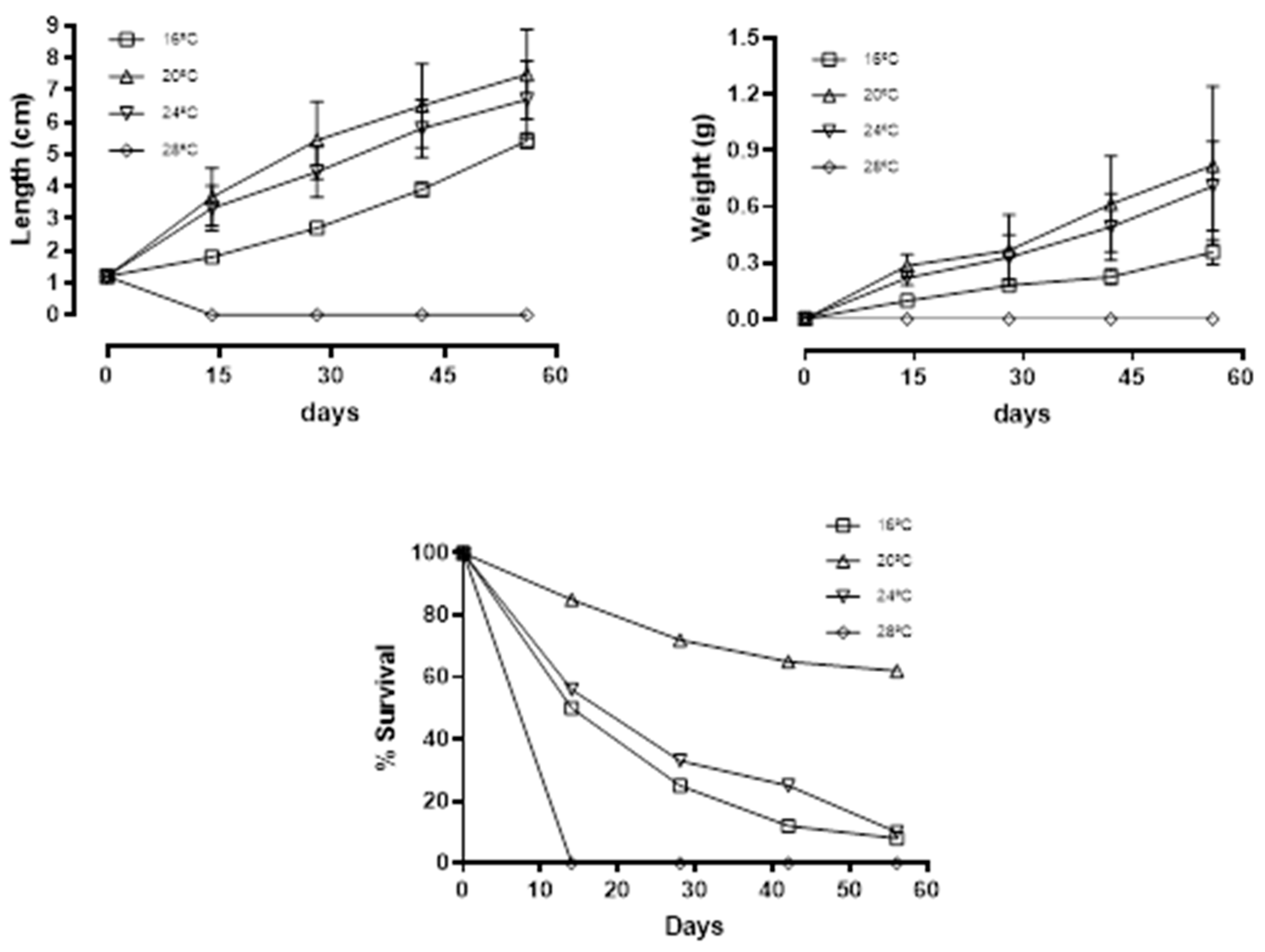

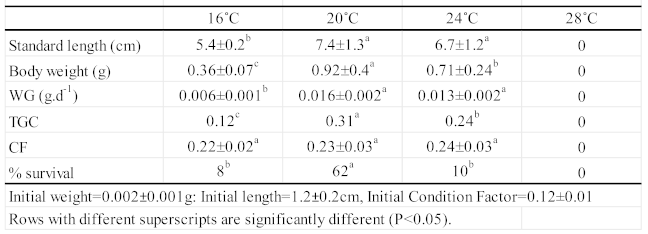

3.2. Juvenile Growth

Data on length, weight, mean Weight Gain (WG), Condition Factor (CF), Thermal-unit Growth Coefficient (TGC), and survival are reported in

Table 2. At the end of the experiment (56 DPP), significant differences (p<0.05) in growth were observed between juveniles reared at 20°C and 24°C compared to those reared at 16°C. However, no significant differences (p>0.05) were observed between juveniles reared at 20°C and 24°C (

Table 2). At 28°C, all fish died before the first sampling at 14 DPP. This differential in growth performance of fish reared at the intermediate temperatures was readily observed from the first sampling period (Fig. 1a, b) until the end of the experiment. CF was the only unaffected growth parameter throughout the experiment, as no significant differences in CF were found among juvenile

H.

guttulatus reared at each of the four temperatures (

Table 1). Survival ranged from 0% in fish reared at 28°C to 62% in fish reared at 20°C, with low intermediate values for fish reared at 16°C (8%) and 24°C (10%) (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

– Length increase, weight increase, and percent survival of juvenile H. guttulatus reared at four tested temperatures (16, 20, 24, and 28ºC).

Figure 1.

– Length increase, weight increase, and percent survival of juvenile H. guttulatus reared at four tested temperatures (16, 20, 24, and 28ºC).

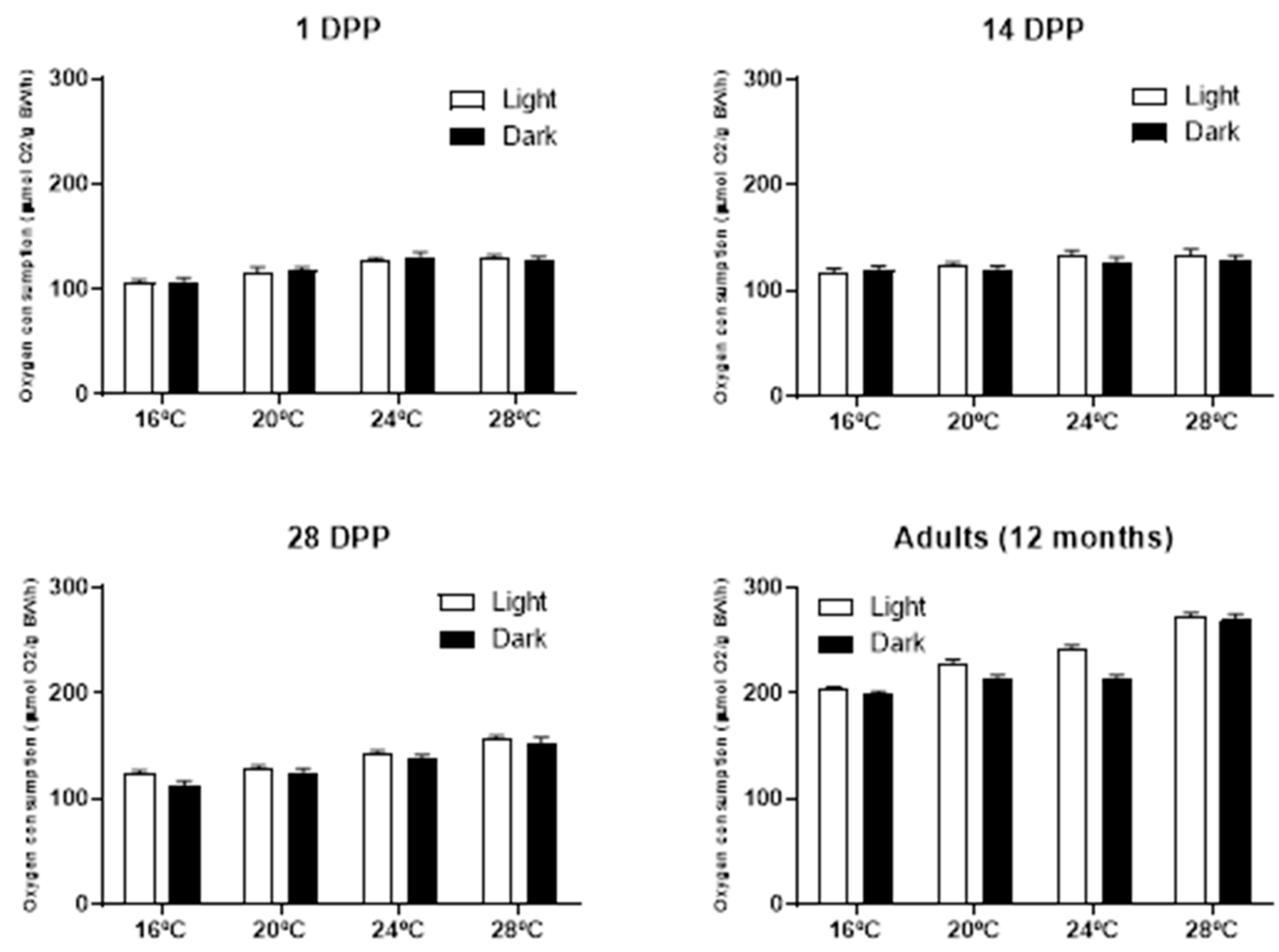

3.3. Respirometry Analysis

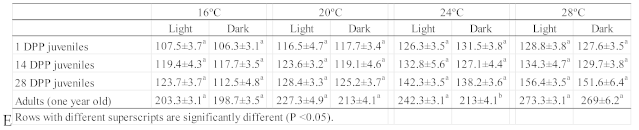

A distinct individual variation in oxygen consumption was observed after fish were moved to the respirometry chambers. Oxygen consumption values for each of tested seahorse groups are detailed in

Table 3. It was observed a constant increase in the oxygen consumption according to the seahorse age and temperature, 107.5±3.7 to 203.3±3.1 μmol O

2/g BW/h between 1 DPP juveniles and adults (year old) at 16°C and 128.8±3.8 to 273.3±3.1 μmol O

2/g BW/h between 1 DPP juveniles and adults (year old) at 28°C during the light period. Likewise, during the dark period a constant increase in the oxygen consumption according to the seahorse age and temperature, 106.3±3.1 to 198.7±3.5 μmol O

2/g BW/h between 1 DPP juveniles and adults (year old) at 16°C and 127.6±3.5 to 269±6.2 μmol O

2/g BW/h between 1 DPP juveniles and adults (year old) at 28°C was observed. No matter the tested temperature, adult seahorses (one year old) consumed almost two times more oxygen than the newly hatched juveniles.

Regardless of age and tested temperature, with exception of 1 DPP juveniles at 24ºC, the oxygen consumption was always higher, but not significantly different (p>0.05) between the light period vs the dark period (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

Fish thermal tolerance can be defined as heat and cold tolerance, which correspond to the highest summer water temperature and the coldest winter water temperature within their ranges [

21]. While species can withstand temporary cold and heat peaks, the prolonged occurrence of these extreme temperatures may cause significant changes in species' growth, reproduction, and survival. The fish thermal environment is thought to have a greater impact on their distribution, overall condition, and survival than any other aquatic habitat characteristic [

22]. Therefore, increasing air temperatures resulting from climate change are expected to increase water temperatures, altering the fish thermal environment with direct effects on their growth, reproduction, and survival, as well as that of their prey [23-25]. Rising temperatures up to certain limits may be favorable, for example, for aquaculture production by increasing the growth rate and reducing the maturation period of fish. However, when temperatures exceed the optimum limits for the species, it adversely affects the health of aquatic animals due to metabolic stress, increased susceptibility to diseases, proliferation of pathogens, and higher oxygen demand [

26].

In the present study, it was observed that temperature variation had a major impact on the reproduction, growth, and survival of both juvenile and adult long snout seahorses. For adult seahorses, male weight gain was significantly lower at 16ºC (the lowest temperature tested) compared to the three remaining temperatures. This result is not surprising, as it is a consequence of the fish's metabolic rate decrease due to the low temperature. However, this metabolic decrease did not result in any mortality in the tested fish. Conversely, the increased mortality observed at 28ºC is a clear negative effect caused by temperature and a strong indication that this species is unable to cope with prolonged heat periods. At 28°C, reproduction was impaired as no viable broods were produced. Overall, it was observed that when subjected to a prolonged heat period, the viability of the species is compromised due to the cessation of reproductive activity and, in most cases, death.

Transposing this evidence to natural circumstances implies that if this species’ populations find themselves trapped in prolonged heat periods, their resilience will be affected, leading to a potential reduction in abundance or even the species' disappearance within a short period of time. In the ria Formosa, according to [

13], water temperature varies from 12°C in winter to 27°C in summer. These temperature ranges are quite similar to those tested in this study, indicating that the effects of temperature on wild seahorse populations in the lagoon may already be occurring. In a climate change scenario, even a small increase in temperature will negatively impact the species' welfare and their ability to remain healthy and stable. Moreover, the ria Formosa lagoon is a highly dynamic system composed of shallow channels where water temperature is homogenized and tends to be similar at all depths preferred by this species (3-11 meters, personal observation), thus preventing seahorses from moving to find suitable thermal habitats. Therefore, as mentioned above, heat waves, which currently last for 1–2 weeks on the Portuguese coast [

11], will become more intense, more frequent, and longer-lasting in warmer climate scenarios [

12], leading to extended periods of heat waves with the potential negative impacts described here.

It was observed that fecundity starts to be impaired at 24°C, as the number of juveniles produced per brood was significantly lower (p<0.05) than at 20°C. Considering that even under normal circumstances, seahorse fecundity is much lower compared to other fish species, this constraint may cause an additional impact on the species' conservation. In this study, this result, combined with the fact that at 24°C, only 10% of the produced juveniles survived to the end of their second month of life, a figure much lower compared to the 62% survival rate at 20°C indicates significant thermal sensitivity. Concordantly, [

17] observed that juvenile

H.

guttulatus have their optimal growth rate at 21°C, and [

27] documented a significant increase in the metabolic rates of newborn juveniles and adult

H.

guttulatus with rising temperatures. According to the authors, the juvenile stages display greater thermal sensitivity and may face greater metabolic challenges with potential cascading consequences for their growth and survival compared to adults. This was confirmed in the present study, as juvenile survival was reduced to 10% at 24°C and resulted in 100% mortality at 28°C.

In this study, oxygen consumption was higher during the light phase compared to the dark phase, regardless of the temperature to which the fish were exposed. Since the fish were fed during the light phase, the increased oxygen consumption may be partly explained by the feeding stimulus, which helped to overcome the light-dark cycle. The higher metabolism in the light phase may be due to the metabolic processing of food, a finding similar to that of [

18], who observed a similar pattern for juvenile Senegalese sole (

Solea senegalensis). However, this increase in metabolic activity was also directly related to the temperature increase; irrespective of the feeding effect, oxygen consumption was amplified by temperature. As observed in the first part of the experiment, juvenile growth and survival and adult reproductive success and survival were severely impacted by temperature. In the second part, an overall increase in oxygen consumption was noted, indicating that the observed results are solely a consequence of temperature effects.

Fish sensitivity to cyclic high temperatures during the first life stages is not specific to seahorse species. [

28] reported that when mean water temperature was increased by just 0.6°C, there was a reduction in life history diversity of rainbow trout (

Oncorhynchus mykiss), and [

29] noted that high temperatures (31-35°C) decreased growth in juvenile Channel catfish (

Ictalurus punctatus) due to reduced food consumption, feed conversion, and increased activity levels. The prevalence of high-temperature periods above the species' optimal range can, therefore, imply a long-term negative effect that may impact the species beyond its coping point, impairing long-term population health.

In this study, it was observed that adult fish (one year old) had a 34.4% increase in oxygen consumption from 16°C to 28°C. Since male seahorses provide paternal care to their broods by maintaining the developing embryos in the brood pouch, oxygen requirement and consumption are even higher during the breeding season, which occurs during the spring-summer period when longer heat waves also happen. This constraint implies an additional physiological demand on the males and will potentially affect them and their resulting offspring in the same way observed in this study. Environmental factors do not play isolated roles in animal physiology; instead, they interact and combine, causing increased detrimental effects on species survival. For aquatic species, increased water temperatures lead to a decrease in dissolved oxygen, requiring additional physiological effort to maintain the necessary oxygen levels in their bodies. Seahorses are no exception. For pregnant males, who provide parental care to their broods, this constraint represents an additional physiological effort, as they need to supply oxygen to the developing embryos in their pouch. This long-term metabolic requirement may help explain the increased male mortality compared to females.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, both juvenile and adult H. guttulatus are affected by long-term exposure to increased temperatures, with direct implications for their growth, survival, and reproduction. Under natural conditions, this may represent a major constraint for the long-term conservation of this and other seahorse species in coastal areas similar to the Ria Formosa, and ultimately for local aquatic biodiversity as a whole. Mitigating the increase in water temperature in coastal areas involves a combination of local and global actions aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions, improving coastal management, and enhancing ecosystem resilience.

While global climate action policies are urgently needed, local mitigation actions must also be enforced to enhance coastal ecosystem resilience. These actions should include: a) the protection and restoration of seagrass meadows and algae beds, as these ecosystems can help absorb excess heat and provide cooling effects, b) the reduction of thermal pollution: to regulate industrial discharge and cooling processes to minimize the release of warm water into coastal areas, c) the pollution control to strengthen measures to reduce coastal pollution, which can exacerbate thermal stress on marine ecosystems, and d) the implementation of zoning regulations to control development and limit activities that contribute to water temperature increases. These local actions are essential to promote the long-term health and sustainability of marine ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.; methodology, J.P. and M.C.; formal analysis, J.P.; writing/original draft preparation, J.P.; review and editing, all authors; project administration, J.P.; funding acquisition, J.P. and F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the project HIPPOCAMPUS_RIA “Avaliação e implementação de conservação ecossistémica de cavalos-marinhos” (Fundo Ambiental) and received Portuguese national funds from FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology through projects UIDB/04326/2020, UIDP/04326/2020 and LA/P/0101/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

CCMAR facilities and the research are certified to house and conduct experiments with live animals (Group-C licenses from the Direção Geral de Alimentação e Veterinária, Ministério da Agricultura, Florestas e Desenvolvimento Rural, Portugal). The captive breeding program for H. guttulatus (Project HIPPOCAMPUS_RIA) was approved by ICNF – Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e das Florestas under the permit S-009617/2024. Under this approval, the study was performed in compliance with the Guidelines of the European Union Council (86/609/EU) and Portuguese legislation for the use of laboratory animals.

Data Availability Statement

The data used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge António Sykes and João Reis for their valuable contribution and assistance in the respirometry analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Foster, S.J.; Vincent, A.C.J. Life history and ecology of seahorses: implications for conservation and management. J. Fish Biol., 2004, 65, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, M.R.; Gladstone, W.; Jelbart, J. The effectiveness of seahorses and pipefish (Pisces: Syngnathidae) as a flagship group to evaluate the conservation value of estuarine seagrass beds. Aquat. Conserv.: Mar. Freshw. 2009, 19, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.M.; Lockyear, J.F.; McPherson, J.M.; Marsden, A.D.; Vincent, A.C.J. First field studies of an Endangered South African seahorse, Hippocampus capensis. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 2003, 67, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, I.R.; Vincent, A. Revisiting two sympatric European seahorse species: apparent decline in the absence of exploitation. Aquat. Conserv.: Mar. Freshw. 2012, 22, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, M.; Caldwell, I.R.; Koldewey, H.J.; Andrade, J.P.; Palma, J. Seahorse (Hippocampinae) population fluctuations in the Ria Formosa Lagoon, south Portugal. J. Fish Biol. 2015, 87, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, B.K.; Cushman, S.A.; Landguth, E.L.; Lucotch, J. Assessing multi-taxa sensitivity to the human footprint, habitat fragmentation and loss by exploring alternative scenarios of dispersal ability and population size: a simulation approach. Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 23, 2761–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allendorf, F.W.; Luikart, G.; Aitken, S.N. Conservation and the genetics of populations, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: London, UK; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, M.L.; Canziani, O.F.; Palutikof, J.P.; Linden, P.J.V.D.; Hanson, C.E. Technical summary. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. In Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Parry, M.L., Canziani, O.F., Palutikof, J.P., Linden, P.J.V.D., Hanson, C.E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK. 2007; pp. 23–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hiscock, K.; Southward, A.; Tittley, I.; Hawking, S. Effects of changing temperature on benthic marine life in Britain and Ireland. Aquat. Conserv.: Mar. Freshw. 2004, 14, 333–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenton, T.M.; Held, H.; Kriegler, E.; Hall, J.W.; Lucht, W.; Rahmstorf, S.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008, 105, 1786–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, P.M.A.; Coelho, F.E.S.; Tomé, A.R.; Valente, M.A. 2002. 20th Century Portuguese Climate and Climate Scenarios. In: Climate change in Portugal. Scenarios, Impacts and adaptation measures -SIAM Project; Santos, F.D., Forbes, K., Moita, R., Eds.; Gradiva, Lisboa, Portugal. pp 27–83.

- Solomon, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Chen, Z.; Marquis, M.; Averyt, K.B.; Tignor, M.; Miller, H.L. Contribution of working group I to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2007; p. 996.

- Newton, A.; Mudge, S.M. Temperature and salinity regimes in a shallow, mesotidal lagoon, the Ria Formosa, Portugal. Estuar. Coast. Shelf. Sci. 2003, 57, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, L.M. A incidência de radiação UV-B na Ria Formosa: Incidência e impactes biológicos. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, M. Trends in seahorse abundance in the Ria Formosa, South Portugal: recent scenarios and future prospects. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, C.M.C. Improving initial survival in cultured seahorses, Hippocampus abdominalis Leeson, 1827 (Teleostei: Syngnathidae). Aquaculture. 2000, 190, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, J.; Bureau, D.P.; Andrade. J.P. Effect of different Artemia enrichments and feeding protocol for rearing juvenile long snout seahorse, (Hippocampus guttulatus). Aquaculture. 2011, 318, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, M.F.; Martins, C.I.M.; Engrola, S.; Conceição, L.E.C. Daily oxygen consumption rhythms of Senegalese sole Solea senegalensis (Kaup, 1858) juveniles. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 2011, 407, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careau, V.; Thomas, D.; Humphries, M.M.; Réale, D. Energy metabolism and animal personality. Oikos. 2008, 117, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.I.M.; Castanheira, M.F.; Engrola, S.; Costas, B.; Conceição, L.E.C. Individual differences in metabolism predict coping styles in fish. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 130, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunday, J.M.; Bates, A.E.; Dulvy, N.K. Thermal tolerance and the global redistribution of animals. Nat. Clim. Change. 2012, 2, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootton, R.J. The ecology of teleost fishes, 2nd ed. Kluwer, Fish and Fisheries Series 24: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998.

- Woodward, G.; Perkins, D.M.; Brown, L.E. Climate change and freshwater ecosystems: impacts across multiple levels of organization. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2093–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershkovitz, Y.; Dahm, V.; Lorenz, A.W.; Hering, D. A multi-trait approach for the identification and protection of European freshwater species that are potentially vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 50, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, Y.; Letcher, B.H.; Hitt, N.P.; Boughton, D.A.; Wofford, J.E.B.; Zipkin, E. Seasonal weather patterns drive population vital rates and persistence in a stream fish. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 1856–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, D.; Pal, A.K.; Sahu, N.P.; Baruah, K.; Yengkokpam, S.; Das, T.; Manush, S.M. Thermal tolerance and metabolic activity of yellowtail catfish Pangasius pangasius (Hamilton) advanced fingerlings with emphasis on their culture potential. Aquaculture. 2006, 258, 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurélio, M.; Faleiro, F.; Lopes, V.M.; Pires, V.; Lopes, A.R.; Pimentel, M.S.; Repolho, T.; Baptista, M.; Narciso, L.; Rosa, R. Physiological and behavioral responses of temperate seahorses (Hippocampus guttulatus) to environmental warming. Mar. Biol. 2013, 160, 2663–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, J.R.; Connolly, P.J.; Romine, J.G.; Perry, R.W. Potential Effects of Changes in Temperature and Food Resources on Life History Trajectories of Juvenile Oncorhynchus mykiss. T. Am. Fish. Soc. 2013, 142, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.B.; Torrans, E.L.; Allen, P.J. Influences of Cyclic, High Temperatures on Juvenile Channel Catfish Growth and Feeding, N. Am. J. Aquac. 2013, 75, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).