Submitted:

02 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Source Organisms and Experimental Design

4.2. Energy Balance and Scope for Growth

4.3. Biochemical Analyses of Tissues

4.4. Oxidative Stress Indicators

4.5. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

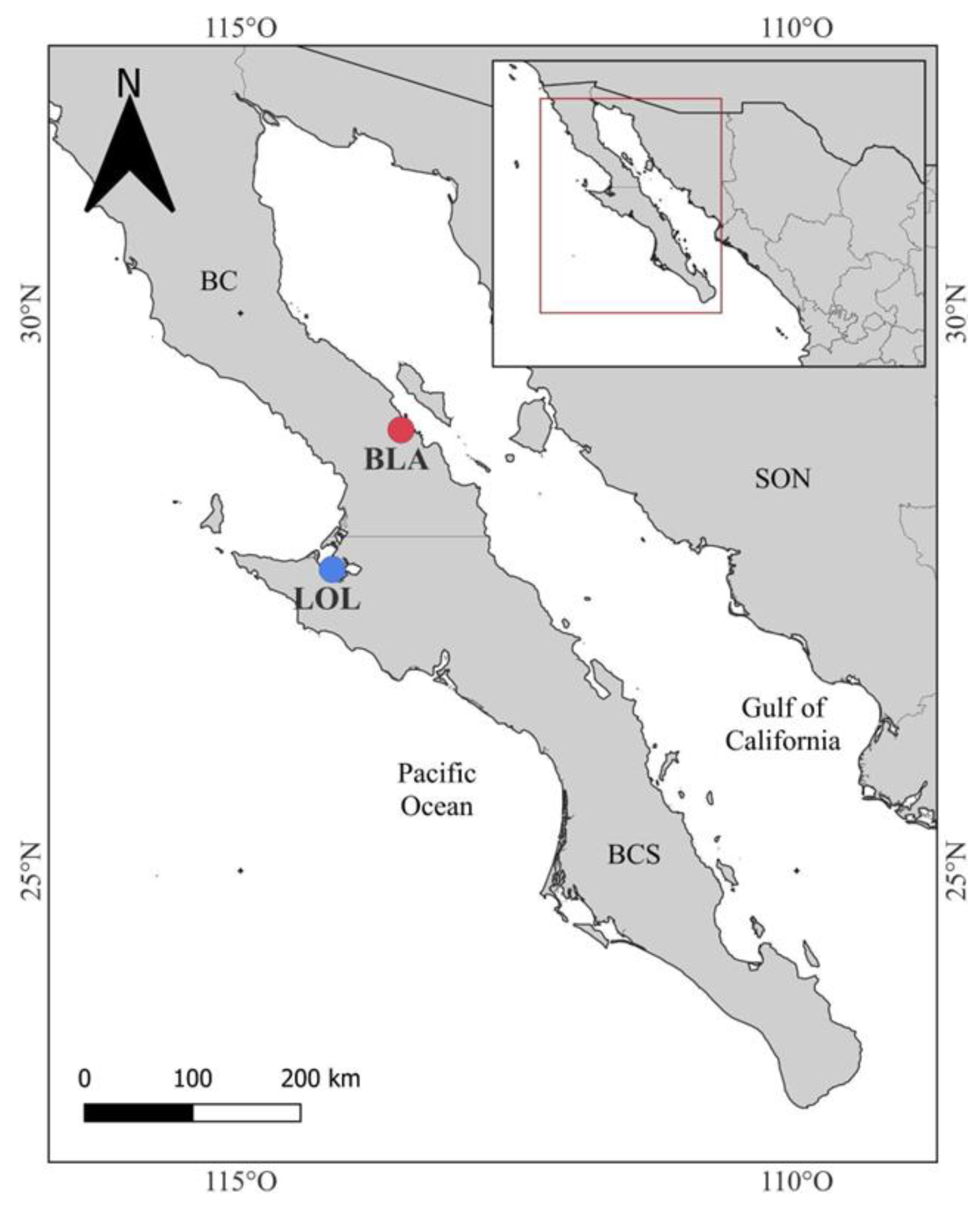

| BLA | Bahía de Los Ángeles |

| LOL | Laguna Ojo de liebre |

| SFG | Scope for growth |

| RR | Respiration rate |

| AR | Absorption rate |

| IR | Ingestion rate |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

References

- Jutfelt, F., Roche, D.G., Clark, T.D., Norin, T., Binning, S.A., Speers-Roesch, B., Sundin, J., 2019. Brain cooling marginally increases acute upper thermal tolerance in Atlantic cod. J. Exp. Biol. 222(19), jeb208249. [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. E., Burrows, M. T., Hobday, A. J., King, N. G., Moore, P. J., Sen Gupta, A., 2022. Biological impacts of marine heatwaves. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15 (1), 119145. [CrossRef]

- Cooley, S., Schoeman, D., Bopp, L., Boyd, P., Donner, S., Ghebrehiwet, D.Y., Ito, S.-I., Kiessling, W., Martinetto, P., Ojea, E., Racault, M.-F., Rost, B., Skern-Mauritzen, M., 2022. Oceans and Coastal Ecosystems and Their Services, in: Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., Okem, A., Rama, B. (Eds.), Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 379–550. [CrossRef]

- Masanja, F., Yang, K., Xu, Y., He, G., Liu, X., Xu, X., Zhao, L., 2023. Impacts of marine heat extremes on bivalves. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1159261. [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H. O., Farrell, A. P., 2008. Physiology and Climate Change. Science, 322(5902), 690–692. [CrossRef]

- Peck, L.S., Morley, S.A., Richard, J., Clark, M.S.,2014. Acclimation and thermal tolerance in Antarctic marine ectotherms. J. Exp. Biol., 217(1), 16-22. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.,Dam, H.G.,2021. Global patterns in copepod thermal tolerance. J. Plankton Res. 43(4),598-609. [CrossRef]

- Stillman, J. H., Somero, G. N., 2000. A comparative analysis of the upper thermal tolerance limits of eastern Pacific porcelain crabs, genus Petrolisthes: influences of latitude, vertical zonation, acclimation, and phylogeny. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 73(2), 200-208. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/epdf/10.1086/316738.

- Marshall, D.J., McQuaid, C.D., 2011. Warming reduces metabolic rate in marine snails: adaptation to fluctuating high temperatures challenges the metabolic theory of ecology. Proc. R. Soc. B 278(1703), 281–288. [CrossRef]

- Morash, A.J., Neufeld, C., MacCormack, T.J., & Currie, S.,2018. The importance of incorporating natural thermal variation when evaluating physiological performance in wild species. J. Exp. Biol., 221(14), jeb164673. [CrossRef]

- Niehaus, A.C., Angilletta Jr, M.J., Sears, M.W., Franklin, C.E., Wilson, R.S., 2012. Predicting the physiological performance of ectotherms in fluctuating thermal environments. J. Exp. Biol. 215(4), 694–701. [CrossRef]

- Vajedsamiei, J., Melzner, F., Raatz, M., Morón Lugo, S. C., & Pansch, C., 2021. Cyclic thermal fluctuations can be burden or relief for an ectotherm depending on fluctuation´s average and amplitude. Funct. Ecol., 35(11), 2483-2496. [CrossRef]

- Manenti, T., Sørensen, J.G., Moghadam, N.N., Loeschcke, V., 2014. Predictability rather than amplitude of temperature fluctuations determines stress resistance in a natural population of Drosophila simulans. Journal of evolutionary Biology, 27(10), 2113-2122. [CrossRef]

- Nancollas, S.J., Todgham, A.E., 2022. The influence of stochastic temperature fluctuations in shaping the physiological performance of the California mussel, Mytilus californianus. J. Exp. Biol., 225(14), jeb243729. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Verdugo, C.A., Koch, V., Félix-Pico, E., Beltran-Lugo, A.I., Cáceres-Martínez, C., Mazn-Suastegui, J.M., Robles-Mungaray, M., Caceres-Martínez, J., 2016. Scallop fisheries and aquaculture in Mexico. In: Developments in Aquaculture and Fisheries Science, Vol. 40, pp. 1111–1125. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Rupp G. S., Valdéz-Ramírez M. E., Lemeda-Fonseca M. (2011) Ecología y Biología pp.25-58. En: Maeda-Martínez A. N., Lodeiros-Seijo C. (Eds). Biología y cultivo de los moluscos pectínidos del género Nodipecten. Editorial Limusa, México.

- Petersen, J. L., Ibarra, A. M., & May, B., 2010. Nuclear and mtDNA lineage diversity in wild and cultured Pacific lion-paw scallop, Nodipecten subnodosus (Baja California Peninsula, Mexico). Marine biology, 157, 2751-2767. [CrossRef]

- Koch, V., Rengstorf, A., Taylor, M., Mazón-Suástegui, J.M., Sinsel, F., Wolff, M., 2015. Comparative growth and mortality of cultured Lion's Paw scallops (Nodipecten subnodosus) from Gulf of California and Pacific populations and their reciprocal transplants. Aquac. Res. 46(1), 185–201. [CrossRef]

- Purce, D.N., Donovan, D.A., Maeda-Martínez, A.N., Koch, V., 2020. Scope for growth of cultivated Pacific and Gulf of California populations of lion’s paw scallop Nodipecten subnodosus, and their reciprocal transplants. Latin Am. J. Aquat. Res. 48(4), 538–551. [CrossRef]

- Joachin-Mejia, N.G., 2022. Caracterización del hábitat térmico de la almeja mano de león (Nodipecten subnodosus) en el noroeste mexicano. [unpublished BSc dissertation]. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Ramírez-Arce, J. L., 2009. Evaluación de la ventaja productiva y grado de esterilidad en triploides de almeja mano de león Nodipecten subnodosus (Sowerby 1835) como una alternativa para el cultivo en el Parque Nacional Bahía de Loreto, Golfo de California. [unpublished MSc dissertation]. Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, México.

- Elliott JM, Davison W. 1975. Energy equivalents of oxygen consumption in animal energetics. Oecología 19: 195-201.

- Lora-Vilchis, M. C., Robles-Mungaray, M., Doktor, N., Voltolina, D., 2004. Food value of four microalgae for juveniles of the lion's paw scallop Lyropecten subnodosus (Sowerby, 1833). J. World Aquac. Soc. 35(2), 232–236. [CrossRef]

- Conover, R.J., 1966. Assimilation of organic matter by zooplankton. Limnology and Oceanography. 11: 338-345.

- Sorokin C., 1973. Dry weight, packed cell volume and optical density: In: Stein, J. (ed). Handbook of phycological methods. Culture methods and growth measurement. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York. Pp. 321-343.

- Solorzano L. 1969. Determination of ammonia in natural waters by the phenolhypochlorite method. Limnol. Oceanogr. 14:799-800.

- Bayne, B.L., Widdows, J., Thompson, R.J., 1976. Physiological integrations. In: Marine Mussels: Their Ecology and Physiology (Ed. B.L. Bayne), Cambridge University Press, pp. 261–291.

- Barnes, H., Blackstock J., 1973. Estimation of lipids in marine animals and tissues: detailed investigations of the sulphophosphovainillin method for total lipids. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 12,103-118. [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M., 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Bioch. 72,256-284.

- Suzuki, K., 2000. Measurement of Mn-SOD and Cu, Zn-SOD. In: Taniguchi, N., Gutteridge, J. (Eds.). Experimental protocols for reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Oxford University Press, U.K. pp. 91-95.

- Aebi, H., 1984. Catalase in vitro. In: Methods in enzymology, oxygen radicals in biological systems. Elsevier, New York, pp. 121-126. [CrossRef]

- Hermes-Lima, M., Storey, J.M. y Storey, K.B., 2001. Antioxidant defenses and animal adaptation to oxygen availability during environmental stress, in: Storey, K.B., Storey, J.M (Eds.) Cell and Molecular Responses to Stress, vol. 2. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands. pp. 263-287. [CrossRef]

- Flohé, L., Günzler, W.A,. 1984. [12] Assays of glutathione peroxidase. Methods enzymol. 105, 114-120. [CrossRef]

- Buege, J.A., Aust, S.D., 1978. [30] Microsomal lipid peroxidation. In Methods in enzymology, Vol. 52, Academic press pp. 302-310. [CrossRef]

- Persky, A.M., Green, P.S., Stubley, L., Howell, C.O., Zaulyanov, L., Brzaeau, G.A., Simpkins, J.W., 2000. Protective effect of estrogens against oxidative damage to heart and skeletal muscle. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine, 223: 59–66. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team, 2021. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Racotta, I., Joachin-Mejia, N., Sicard, M.T., Lluch-Cota, S.E. Aquaculture site selection for the lion´s paw scallop Nodipecten subnodosus, based on environmental temperature variability and organisms’ growth and ecophysiological performance. Aquacilture Reports, 2024. submitted.

- Cruz, P., Ramirez, J.L., Garcia, G.A., Ibarra, A.M., 1998. Genetic differences between two populations of catarina scallop (Argopecten ventricosus) for adaptations for growth and survival in a stressful environment. Aquaculture 166(3–4), 321–335. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, P., Rodríguez-Jaramillo, C., Ibarra, A.M., 1999. Environment and population origin effects on first sexual maturity of catarina scallop, Argopecten ventricosus (Sowerby II, 1842). Aquaculture 172(1), 105–115.

- Colinet, Hervé; Sinclair, Brent J; Vernon, Philippe; and Renault, David, "Insects in fluctuating thermal environments." (2015). Biology Publications. 67. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/biologypub/67.

- Bozinovic, F., Bastías, D. A., Boher, F., Clavijo-Baquet, S., Estay, S. A., & Angilletta Jr, M. J. (2011). The mean and variance of environmental temperature interact to determine physiological tolerance and fitness. Physiol. Biochem.l Zool. 84(6), 543-552. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/662551.

- Sicard-González, M.T. (2006). Efecto de la oscilación térmica en la fisiología de la almeja mano de león (Nodipecten subnodosus Sowerby, 1835) [unpublished doctoral dissertation] Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León.

- Palacios, E., Racotta, I.S., Kraffe, E., Marty, Y., Moal, J., Samain, J.F., 2005. Lipid composition of the giant lion's-paw scallop (Nodipecten subnodosus) in relation to gametogenesis: I. Fatty acids. Aquaculture 250(1–2), 270–282. [CrossRef]

- Palacios, E., Racotta, I.S., Arjona, O., Marty, Y., Le Coz, J.R., Moal, J., Samain, J.F., 2007. Lipid composition of the pacific lion-paw scallop, Nodipecten subnodosus, in relation to gametogenesis: 2. Lipid classes and sterols. Aquaculture 266(1–4), 266–273. [CrossRef]

- Pernet, F., Tremblay, R., Comeau, L.,Guderley, H., 2007. Temperature adaptation in two bivalve species from different thermal habitats: energetics and remodelling of membrane lipids. J. Exp. Biol. 210 (17), 2999–3014. [CrossRef]

- Artigaud, S., Richard, J., Thorne, M. A., Lavaud, R., Flye-Sainte-Marie, J., Jean, F., Pichereau, V. 2015. Deciphering the molecular adaptation of the king scallop (Pecten maximus) to heat stress using transcriptomics and proteomics. BMC genomics, 16, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Laudicella, V. A., Whitfield, P. D., Carboni, S., Doherty, M. K., Hughes, A. D., 2020. Application of lipidomics in bivalve aquaculture, a review. Reviews in Aquaculture, 12(2), 678-702. [CrossRef]

- Abele, D., Heise, K., Pörtner, H.O., Puntarulo, S., 2002. Temperature-dependence of mitochondrial function and production of reactive oxygen species in the intertidal mud clam Mya arenaria. J. Exp. Biol. 205(13), 1831–1841. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X., Yang, Z., Liu, Z., Wang, X., Yu, H., Peng, C., ... & Bao, Z. (2022). Metabonomic analysis provides new insights into the response of Zhikong scallop (Chlamys farreri) to heat stress by improving energy metabolism and antioxidant capacity. Antioxidants, 11(6), 1084. [CrossRef]

- Song, J. A., Lee, E., Choi, Y. U., Park, J. J. C., & Han, J., 2025. Influence of temperature changes on oxidative stress and antioxidant defense system in the bay scallop, Argopecten irradians. Comp. Biochem Physiol.Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 299, 111775. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. A., Henderson, S., Miller-Ezzy, P., Li, X. X., Qin, J. G., 2019. Immune response to temperature stress in three bivalve species: Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas, Mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis and mud cockle Katelysia rhytiphora. Fish shellfish Immunol. 86, 868-874. [CrossRef]

- Giraud-Billoud, M., Moreira, D. C., Minari, M., Andreyeva, A., Campos, É. G., Carvajalino-Fernández, J. M., ... & Hermes-Lima, M.,2024. Evidence supporting the ‘preparation for oxidative stress’(POS) strategy in animals in their natural environment. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 111626.

- Bonesteve, A., Lluch-Cota, S. E., Sicard, M. T., Racotta, I. S., Tripp-Valdez, M. A., Rojo-Arreola, L.,2025. HSP mRNA sequences and their expression under different thermal oscillation patterns and heat stress in two populations of Nodipecten subnodosus. Cell Stress Chaperones, 30(1), 33-47. [CrossRef]

- Salgado-García, R. L., Kraffe, E., Tripp-Valdez, M. A., Ramírez-Arce, J. L., Artigaud, S., Flye-Sainte-Marie, J., Racotta, I. S.,2023. Energy metabolism of juvenile scallops Nodipecten subnodosus under acute increased temperature and low oxygen availability. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol., 278, 111373. [CrossRef]

- Götze, S., Bock, C., Eymann, C., Lannig, G., Steffen, J. B. M., & Pörtner, H. O.,2020. Single and combined effects of the “Deadly trio” hypoxia, hypercapnia and warming on the cellular metabolism of the great scallop Pecten maximus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 243–244,110438. [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, I. M., Frederich, M., Bagwe, R., Lannig, G., Sukhotin, A. A., 2012. Energy homeostasis as an integrative tool for assessing limits of environmental stress tolerance in aquatic invertebrates. Marine environmental research, 79, 1-15.

- Bresollier. L., Salgado-García, R.L., Racotta, I., Kraffe, E., Sicard, M.T., Lluch-Cota, S.E. Tripp-Valdez, M.T. Contrasting cellular energy responses to regular and chaotic daily thermal oscillations in two populations of Nodipecten subnodosus scallops. J. Thermal Biol. 2025, submitted.

- Yoon, D. S., Byeon, E., Kim, D. H., Lee, M. C., Shin, K. H., Hagiwara, A., Lee, J. S., 2022. Effects of temperature and combinational exposures on lipid metabolism in aquatic invertebrates. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol., 262, 109449. [CrossRef]

- Röszer, T., 2014. The invertebrate midintestinal gland (“hepatopancreas”) is an evolutionary forerunner in the integration of immunity and metabolism. Cell Tissue Res. 358, 685–695. [CrossRef]

- Song, J. A., Choi, C. Y.,2021. Temporal changes in physiological responses of Bay Scallop: Performance of antioxidant mechanism in Argopecten irradians in response to sudden changes in habitat salinity. Antioxidants, 10(11), 1673. [CrossRef]

- Seebacher, F., White, C. R., Franklin, C. E., 2015. Physiological plasticity increases resilience of ectothermic animals to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 5(1), 61-66. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).