Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

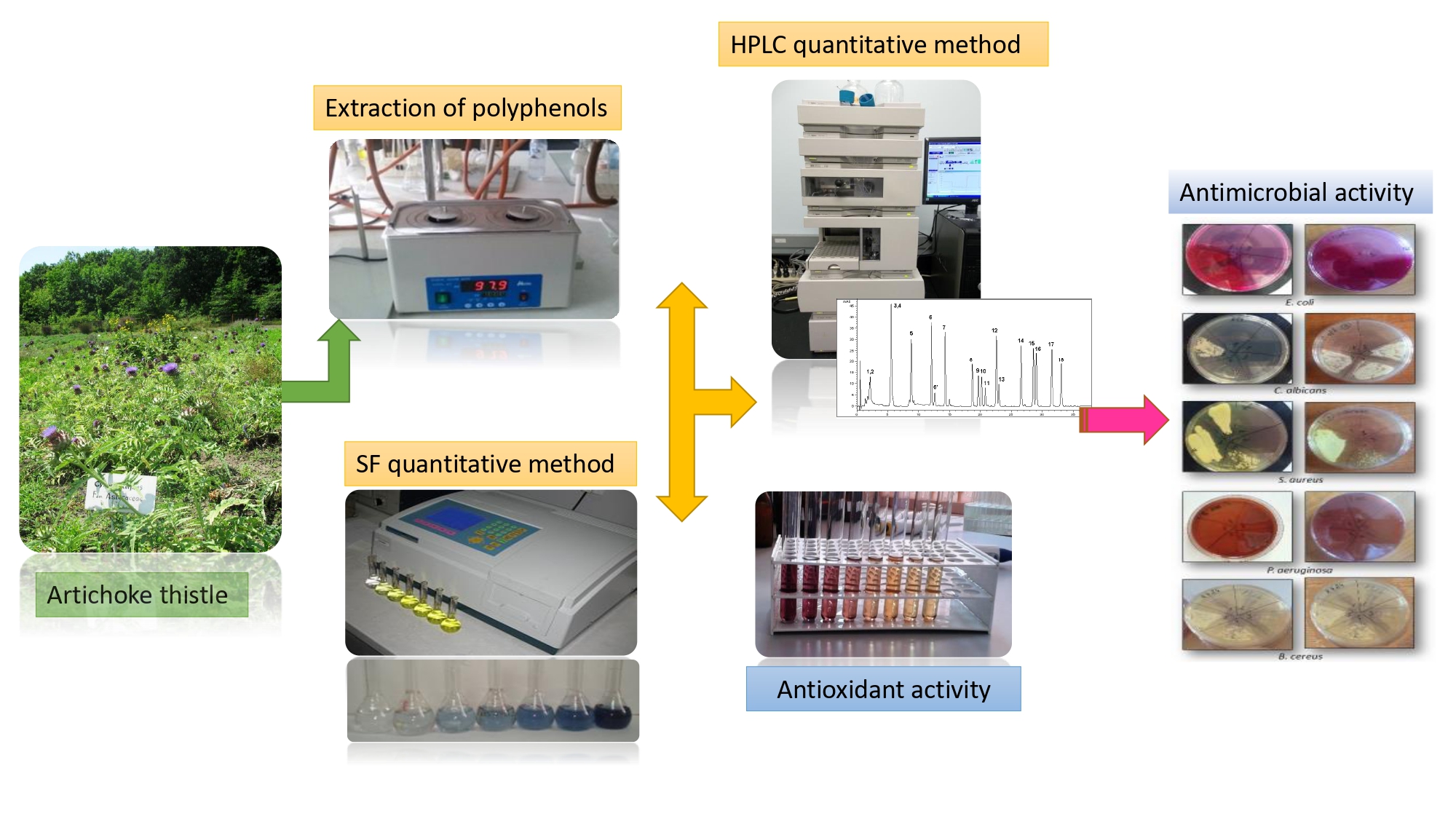

Artichoke, a medicinal plant with various therapeutical uses, is widely cultivated in many world geographical areas. The aim of this study was to establish the antimicrobial profile by means of comparative evaluation of the phytochemical constituents , antioxidant, anti-lipid peroxidation and antimicrobial activities of the basal and cauline leaves, as well as the by-products: stems, bracts, inflorescences from Cynara scolymus L. cultivated in the Republic of Moldova. Qualitative and quantitative characterization of the main phenolic compounds from ethanolic extracts was carried out by the HPLC-UV-MS method. The in vitro antioxidant activity was evaluated using DPPH˙, ABTS˙+, FRAP and NO˙ scavenging methods. Lipid lowering effect was establish with malonic dialdehyde complex and thiobarbituric acid. Antimicrobial properties were screened using diffusion method. The HPLC UV-MS analysis highlighted that green aerial parts of C. scolymus are characterized by the presence of five phenolic acids (kaempferol, gentisic, chlorogenic, p-coumaric, ferulic and caffeic) and four flavonoid heterosides and aglycones (isoquercitrin, quercitrin, luteolin and apigenin). Correlation between total polyphenolic content and antioxidant activity was found to be statistically significant (p<0.01). The extracts of C. scolymus aerial parts exhibited significant antibacterial and antifungal activities, (p<0.05) against all tested microorganisms, while no inhibitory effect for inflorescences was observed. Artichoke leaves and by-products may be considered important and promising sources of bioactive compounds for herbal medicinal products, functional foods and nutraceuticals, due to their antimicrobial properties.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Spectrophotometrical Assays for the quantification of Total Phenolic Compounds

2.2. HPLC-MS Analysis of the Extracts

2.3. Antioxidant properties of C. scolymus aerial parts extracts

2.4. Antimicrobial Activity of C. scolymus aerial parts extracts

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

4.2. Plant Materials

4.2. Extract Preparation

4.3. Total Phenolic Content Assessment

4.4. Total Flavonoid Content Assessment

4.5. Analyses using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

4.6. Antioxidant Activities

4.6.1. DPPH Assay

4.6.2. ABTS Assay

4.6.3. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Potential Assay

4.6.4. Nitric oxide reducing Assay

4.6.5. In vitro determination of the capacity to inhibit low-density lipoprotein oxidation

4.7. Antimicrobial Activity

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koma, P.L.; Matotoka, M.M.; Mazimba, O.; Masoko, P. Isolation and In Vitro Pharmacological Evaluation of Phytochemicals from Medicinal Plants Traditionally Used for Respiratory Infections in Limpopo Province. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 965. [CrossRef]

- Mirković, S.; Martinović, M.; Tadić, V.M.; Nešić, I.; Jovanović, A.S.; Žugić, A. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oils from Selected Pinus Species from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 677. [CrossRef]

- Matlala, M.P.; Matotoka, M.M.; Shekwa, W.; Masoko, P. Antioxidant: Antimycobacterial and Antibiofilm Activities of Acetone Extract and Subfraction Artemisia afra Jacq. ex Willd. Against Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1027. [CrossRef]

- Šovljanski, O.; Aćimović, M.; Tomić, A.; Lončar, B.; Miljković, A.; Čabarkapa, I.; Pezo, L. Antibacterial and Antifungal Potential of Helichrysum italicum (Roth) G. Don Essential Oil. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 722. [CrossRef]

- Kurćubić, V.S.; Đurović, V.; Stajić, S.B.; Dmitrić, M.; Živković, S.; Kurćubić, L.V.; Mašković, P.Z.; Mašković, J.; Mitić, M.; Živković, V.; et al. Multitarget Phytocomplex: Focus on Antibacterial Profiles of Grape Pomace and Sambucus ebulus L. Lyophilisates Against Extensively Drug-Resistant (XDR) Bacteria and In Vitro Antioxidative Power. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 980. [CrossRef]

- Alessandroni, L.; Bellabarba, L.; Corsetti, S.; Sagratini, G. Valorization of Cynara cardunculus L. var. scolymus Processing By-Products of Typical Landrace “Carciofo Di Montelupone” from Marche Region (Italy). Gastronomy 2024, 2, 129-140. [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, N., Cojocaru-Toma, M., Pompuș, I., Chiru, T., Ciobanu, C., Benea, A. Plante din colecția Centrului Științific de cultivare a Plantelor medicinale. Compendium. IP Univ. de stat de Medicină şi Farmacie Nicolae Testemiţanu, Chișinău: Print Caro, Moldova, 2019; pp. 29-30. ISBN 978-9975-56-660-5.

- Se˻kara, A.; Kalisz, A.; Gruszecki, R.; Grabowska, A.; Kunicki, E. Globe artichoke – a vegetable, herb and ornamental of value in central Europe. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2015, 90(4), 365–374. [CrossRef]

- Sałata, A.; Lombardo, S.; Pandino, G.; Mauromicale, G.; Buczkowska, H.; Nurzyńska-Wierdak, R. Biomass yield and polyphenol compounds profile in globe artichoke as affected by irrigation frequency and drying temperature. Industrial Crops and Products 2022, 176, 114375. ISSN 0926-6690. [CrossRef]

- Zagoskina, N.V.; Zubova, M.Y.; Nechaeva, T.L.; Kazantseva, V.V.; Goncharuk, E.A.; Katanskaya, V.M.; Baranova, E.N.; Aksenova, M.A. Polyphenols in Plants: Structure, Biosynthesis, Abiotic Stress Regulation, and Practical Applications (Review). International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 9, 24(18), 13874. [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, S.; Pandino, G.; Ierna, A.; Mauromicale, G. Variation of polyphenols in a germplasm collection of globe artichoke, Food Research International 2012, 46, 2, 544-551. ISSN 0963-9969. [CrossRef]

- Crews, T.E.; Carton, W.; Olsson, L. Is the future of agriculture perennial? Imperatives and opportunities to reinvent agriculture by shifting from annual monocultures to perennial polycultures. Global Sustainability 2018, 1, 11. [CrossRef]

- Vico, G.; Brunsell, N. Tradeoffs between water requirements and yield stability in annual vs. perennial crops. Advances in Water Resources 2018, 112, 189-202. ISSN 0309-1708. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Tian, Li, J.; Xiao, Z. Potential of Perennial Crop on Environmental Sustainability of Agriculture. Procedia Environmental Sciences 2011, 10, 1141-1147. ISSN 1878-0296, . [CrossRef]

- Gominho, J.; Dolores Curt, M.; Lourenço, A.; Fernández, J.; Pereira, H. Cynara cardunculus L. as a biomass and multi-purpose crop: A review of 30 years of research. Biomass and Bioenergy, 2018, 109, 257-275. ISSN 0961-9534. [CrossRef]

- Służały, P.; Paśko, P.; Galanty, A. Natural Products as Hepatoprotective Agents—A Comprehensive Review of Clinical Trials. Plants 2024, 13, 1985. [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, P.; Quizhpe, J.; Rosell, M.d.l.Á.; Peñalver, R.; Nieto, G. Bioactive Compounds, Health Benefits and Food Applications of Artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) and Artichoke By-Products: A Review. Journal of Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 4940. [CrossRef]

- Jalili, C.; Moradi, S.; Babaei, A.; Boozari, B.; Asbaghi, O.; Lazaridi, A.V.; Hojjati Kermani, M.A.; Miraghajani, M. Effects of Cynara scolymus L. on glycemic indices: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2020, 52, 102496, ISSN 0965-2299. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, R.; Moretto, G.; Pellicorio, V.; Papetti, A. Globe Artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) By-Products in Food Applications: Functional and Biological Properties. Foods 2024, 13, 1427. [CrossRef]

- Al Masalmeh, A.M.; Mallah, E.; Mansoor, K.; Abu-Qatouseh, L.; El-Hajji, F.D.; Idkaidek, N.; Al-Bashiti, I.; Issa, I.H.; Al Meslamani, A.Z.; Aws, S. Pharmacokinetic interaction of rosuvastatin with artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) leaf extract in rats. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 2023, 13(06), 179–192. [CrossRef]

- El Sohafy, S.M.; Shams Eldin, S.M.; Sallam, S.M.; Bakry, R.; Nassra, R.A.; Dawood, H.M Exploring the ethnopharmacological significance of Cynara scolymus bracts: Integrating metabolomics, in-Vitro cytotoxic studies and network pharmacology for liver and breast anticancer activity assessment. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2024, 334, 118583. ISSN 0378-8741. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.A.B.; Guerra, Â.R.; Guerreiro, O.; Santos, S.A.O.; Oliveira, H.; Freire, C.S.R.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Duarte, M.F. Antiproliferative Effects of Cynara cardunculus L. var. altilis (DC) Lipophilic Extracts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18, 63. [CrossRef]

- Mohaddese, M. Cynara scolymus (artichoke) and its efficacy in management of obesity. Bulletin of Faculty of Pharmacy Cairo University 2018, 56, 2, 115-120. ISSN 1110-0931. [CrossRef]

- Lattanzio, V.; Paul A. Kroon, Vito Linsalata, Angela Cardinali, Globe artichoke: A functional food and source of nutraceutical ingredients. Journal of Functional Foods 2009, 1, 2, 131-144. ISSN 1756-4646. [CrossRef]

- .

- Romanian Ministry of Health. Romanian Pharmacopoeia. 10th ed. Bucharest: Romanian. 1993; pp. 334–336.

- Zazzali, I.; Gabilondo, J.; Mallmann, L.P.; Rodrigues, E.; Perullini, M.; Santagapita, P.R. Overall evaluation of artichoke leftovers: Agricultural measurement and bioactive properties assessed after green and low-cost extraction methods. Food Bioscience 2021, 41, 100963. [CrossRef]

- El-Nashar, H.A.S.; Abbas, H.; Zewail, M.; Noureldin, M.H.; Ali, M.M.; Shamaa, M.M.; Khattab, M.A.; Ibrahim, N. Neuroprotective Effect of Artichoke-Based Nanoformulation in Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Model: Focus on Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Amyloidogenic Pathways. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1202. [CrossRef]

- Cioni, E.; Di Stasi, M.; Iacono, E.; Lai, M.; Quaranta, P.; Luminare, A.G.; Gambineri, F.; De Leo, M.; Pistello, M.; Braca, A. Enhancing antimicrobial and antiviral properties of Cynara scolymus L. waste through enzymatic pretreatment and lactic fermentation. Food Bioscience 2024, 57, 103441. ISSN 2212-4292. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Barros, L.; José Alves M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira I.C. Artichoke and milk thistle pills and syrups as sources of phenolic compounds with antimicrobial activity. Food Funct 2016, Jul 13;7(7):3083-90. PMID: 27273551. [CrossRef]

- Baran, A.; Keskin, C.; Baran, M.F.; Huseynova, I.; Khalilov, R.; Eftekhari, A.; Irtegun-Kandemir, S.; Kavak, D.E. Ecofriendly Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Ananas comosus Fruit Peels: Anticancer and Antimicrobial Activities. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry 2021, 30, 2058149. [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, O.; Abbak, M.; Demirbolat, G.M.; Birtekocak, F.; Aksel, M.; Pasa, S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Cynara scolymus leaf extracts: The characterization, anticancer potential with photodynamic therapy in MCF7 cells. PLoS ONE 2019, 14(6), e0216496. https:// doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216496.

- Balasubramanian, B.; Gangwar, J.; James, N.; Pappuswamy, M.; Anand, A.V.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Valan Arasu, M.; Liu, W.-C.; Sebastian, J.K. Green Synthesis of Bioinspired Nanoparticles Mediated from Plant Extracts of Asteraceae Family for Potential Biological Applications. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 543. [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, S.; Viana, J. Production of Silver Nanoparticles by Green Synthesis Using Artichoke (Cynara Scolymus L.) Aqueous Extract and Measurement of Their Electrical Conductivity. Advances in Natural Sciences: Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2018, 9 (4): 045002. [CrossRef]

- Khedr, A.I.M.; Farrag, A.F.S.; Nasr, A.M.; Swidan, S.A.; Nafie, M.S.; Abdel-Kader, M.S.; Goda, M.S.; Badr, J.M.; Abdelhameed, R.F.A. Comparative Estimation of the Cytotoxic Activity of Different Parts of Cynara scolymus L.: Crude Extracts versus Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles with Apoptotic Investigation. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2185. [CrossRef]

- Grabowska, A.; Caruso, G.; Mehrafarin, A.; Kalisz, A.; Gruszecki, R.; Kunicki, E.; Sękara, A. Application of modern agronomic and biotechnological strategies to valorise worldwide globe artichoke (Cynara cardunculus L.) potential - an analytical overview. Italian Journal of Agronomy 2018, 13, 4, 1252. ISSN 1125-4718. [CrossRef]

- Buzzanca, C.; Di Stefano, V.; D’Amico, A.; Gallina, A.; Grazia Melilli, M. A systematic review on Cynara cardunculus L.: bioactive compounds, nutritional properties and food-industry applications of a sustainable food. Natural Product Research 2024. ISSN 1478-6419. [CrossRef]

- Mandim, F.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Giannoulis, K.D.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Barros, L. Chemical Composition of Cynara cardunculus L. var. altilis Bracts Cultivated in Central Greece: The Impact of Harvesting Time. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1976. [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Z.; Subbiah, V.; Suleria, H.A.R. Extraction and characterization of phenolic compounds and their potential antioxidant activities. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29(54), 81112-81129. [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, C.; Diug, E.; Calalb, T.; Tomuta, I.; Achim, M. Optimisation of ultrasound-assisted extraction method of biologically active compounds from Cynara scolymus L. Curierul medical, 2015, 58, 2, 23-28. ISSN 1857-0666. [Google Scholar].

- Riadh, I.; Tlili, I.; R’him, T.; Rached, Z.; Arfaoui, K.; Pék, Z.; Lenucci, M. S.; Daood, H.; Helyes, L. Assessment of The Phenolic and Flavonoid Content in Certain Globe Artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) Cultivars Grown in Northern Tunisia. Turkish Journal of Agriculture - Food Science and Technology 2022, 10(6), 1125–1129. [CrossRef]

- Costea, L.; Chițescu, C.L.; Boscencu, R.; Ghica, M.; Lupuliasa, D.; Mihai, D.P.; Deculescu-Ioniță, T.; Duțu, L.E.; Popescu, M.L.; Luță, E.-A.; et al. The Polyphenolic Profile and Antioxidant Activity of Five Vegetal Extracts with Hepatoprotective Potential. Plants 2022, 11, 1680. [CrossRef]

- Vamanu, E.; Vamanu, A.; Niţă, S.; Colceriu, S. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Ethanol Extracts of Cynara Scolymus (Cynarae folium, Asteraceae Family). Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 2011; 10 (6). 777-783. [CrossRef]

- Sałata, A.; Nurzyńska-Wierdak, R.; Lombardo, S.; Pandino, G.; Mauromicale, G.; Ibáñez-Asensio, S.; Moreno-Ramón, H.; Kalisz, A. Polyphenol Profile, Antioxidant Activity and Yield of Cynara cardunculus altilis in Response to Nitrogen Fertilisation. Agronomy 2024, 14, 739. [CrossRef]

- Biel, W.; Witkowicz, R.; Piątkowska, E. et al. Proximate Composition, Minerals and Antioxidant Activity of Artichoke Leaf Extracts. Biological Trace Element Research 2020, 194, 589–595. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, C.H.; Duarte, M.P.; Andrade, M.A.; Mateus, A.R.; Vilarinho, F.; Fernando, A.L.; Silva, A.S. Exploring Cynara cardunculus L. by-products potential: Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Industrial Crops and Products 2024, 222, 1, 119559. ISSN 0926-6690. [CrossRef]

- Noriega-Rodríguez, D.; Soto-Maldonado, C.; Torres-Alarcón, C.; Pastrana-Castro, L.; Weinstein-Oppenheimer, C.; Zúñiga-Hansen, M.E. Valorization of Globe Artichoke (Cynara scolymus) Agro-Industrial Discards, Obtaining an Extract with a Selective Effect on Viability of Cancer Cell Lines. Processes 2020, 8, 715. [CrossRef]

- Pagano, I.; Piccinelli, A.L.; Celano, R.; Campone, L.; Gazzerro, P.; De Falco, E.; Rastrelli, L. Chemical profile and cellular antioxidant activity of artichoke by-products. Food & Function 2016, 7(12), 4841-4850. 10.1039/C6FO01443G.

- Lavecchia, R.; Maffei, G.; Paccassoni, F. et al. Artichoke Waste as a Source of Phenolic Antioxidants and Bioenergy. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 2975–2984. [CrossRef]

- Kayahan, S.; Saloglu, D. Comparison of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activities of Raw and Cooked Turkish Artichoke Cultivars. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2021, 5, 761145. [CrossRef]

- Mocelin, R.; Marcon, M.; Santo, G.D.; Zanatta, L.; Sachett, A.; Schönell, A.P.; Bevilaqua, F.; Giachini, M.; Chitolina, R.; Wildner, S.M.; Duarte, M.; Conterato, G.; Piato, A.L..; Gomes, D.; Roman Junior, W. Hypolipidemic and antiatherogenic effects of Cynara scolymus in cholesterol-fed rats. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 2016, 26, 2, 233-239. ISSN 0102-695X. [CrossRef]

- Zayed, A.; Serag, A.; Farag, M.A. Cynara cardunculus L.: Outgoing and potential trends of phytochemical, industrial, nutritive and medicinal merits. Journal of Functional Foods 2020, 69, 103937. ISSN 1756-4646. [CrossRef]

- Luca, S. V.; Kulinowski, L.; Ciobanu, C.; Zengin, G.; Czerwinska, M.E.; Granica, S.; Xiao, J.; Skalicka-Wozniak, K.; Trifan, A. Phytochemical and multi-biological characterization of two Cynara scolymus L. varieties: A glance into their potential large scale cultivation and valorization as bio-functional ingredients. Industrial Crops and Products 2022, 178. ISSN 0926-6690. [CrossRef]

- Samah, M.; El Sohafy, Safa M.; Shams Eldin, S. M.; Bakry, S.R.; Nassra, R.; Dawood, H. Exploring the ethnopharmacological significance of Cynara scolymus bracts: Integrating metabolomics, in-Vitro cytotoxic studies and network pharmacology for liver and breast anticancer activity assessment. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2024, 334, 118583. ISSN 0378-8741. [CrossRef]

- Magdy, A.; Mohamed, A.; Meshrf, W.; Marrez, A.D. In vitro antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer activities of globe artichoke (Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus L.) bracts and receptacles ethanolic extract. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2020, 29, 101774. ISSN 1878-8181. [CrossRef]

- Ben Salem, M.; Affes, H.; Athmouni, K.; Ksouda, K.; Dhouibi, R.; Sahnoun, Z.; Hammami, S.; Zeghal, K.M. Chemicals Compositions, Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Cynara scolymus Leaves Extracts, and Analysis of Major Bioactive Polyphenols by HPLC. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2017, 4951937. [CrossRef]

- Kollia, E.; Markaki, P.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Proestos, C. Antioxidant activity of Cynara scolymus L. and Cynara cardunculus L. extracts obtained by different extraction techniques. Natural Product Research 2017, 31(10), 1163-1167. [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, M.C.; Orellana Palacios, J.C.; Hesami, G.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Domínguez, R.; Moreno, A.; Hadidi, M. Spectrophotometric Methods for Measurement of Antioxidant Activity in Food and Pharmaceuticals. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2213. [CrossRef]

- Farnad, N.; Heidari, R.; Aslanipour, B. Phenolic composition and comparison of antioxidant activity of alcoholic extracts of Peppermint (Mentha piperita). Food Measure 2014, 8, 113–121. [CrossRef]

- Porro, C.; Benameur, T.; Cianciulli, A.; Vacca, M.; Chiarini, M.; De Angelis, M.; Panaro, M.A. Functional and Therapeutic Potential of Cynara scolymus in Health Benefits. Nutrients 2024, 16, 872. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, I.; Shahat, A.A.; Noman, O.M.; Milenkovic, D.; Amrani, S.; Harnafi, H. Effects of Cynara scolymus L. Bract Extract on Lipid Metabolism Disorders Through Modulation of HMG-CoA Reductase, Apo A-1, PCSK-9, p-AMPK, SREBP-2, and CYP2E1 Expression. Metabolites 2024, 14(12), 728. [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, W.; Ji, B.; Zhou, F.. Bioactivity of Dietary Polyphenols: The Role in LDL-C Lowering. Foods 2021, 10(11), 2666. [CrossRef]

- Mandim, F.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Giannoulis, K.D; Dias, M.I.; Fernandes, A.; Pinela, J.; Kostic, M.; Soković, M.; Barros, L.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I. Seasonal variation of bioactive properties and phenolic composition of Cynara cardunculus var. altilis, Food Research International 2020, 134, 109281. ISSN 0963-9969. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Shallan, M.A.; Meshrf, W.A.; Marrez, D.A. Phenolic Constituents, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Globe Artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) Aqueous Extracts. Tropical Journal of Natural Product Research 2021, 5(11), 1986-1994. doi.org/10.26538/tjnpr/v5i11.16.

- Alsubaiei, S.R.M.; Alfawaz, H.A.; Amina, M.; Al Musayeib, N.M.; El-Ansary, A.; Ahamad, S.R.; Noman, O.M.; Maini, J.A. Comparative Chemical Profiling and Biological Potential of Essential Oils of Petal, Choke, and Heart Parts of Cynara scolymus L. Head. Journal of Chemistry 2022, 2355004. [CrossRef]

- Shallan, M.A.; Ali, M.A.; Meshrf, W.A.; Marrez, D.A. In vitro antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer activities of globe artichoke (Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus L.) bracts and receptacles ethanolic extract. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2020, 29, 101774. [CrossRef]

- Scavo, A.; Pandino, G.; Restuccia, C.; Parafati, L.; Cirvilleri, G.; Mauromicale, G. Antimicrobial activity of cultivated cardoon (Cynara cardunculus L. var. altilis DC.) leaf extracts against bacterial species of agricultural and food interest. Industrial Crops and Products 2019, 129, 206-211. ISSN 0926-6690. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, H.; Lo R.; Lu, Y. Antimicrobial Activities of Cynara scolymus L. Leaf, Head, and Stem Extracts. Journal of Food Science 2005, 70, p. 45. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:96734013}.

- Mejri, F.; Baati, T.; Martins, A.; Selmi, S.; Serralheiro, M.L.; Falé, P.L.; Rauter, A.; Casabianca, H.; Hosni, K. Phytochemical analysis and in vitro and in vivo evaluation of biological activities of artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) floral stems: Towards the valorization of food by-products. Food Chemistry 2020, 333, 127506. [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods in Enzymology 1999, 299, 152–178. [CrossRef]

- Benedec, D.; Oniga, I.; Hanganu, D.; Tiperciuc, B.; Nistor, A.; Vlase, A.-M.; Vlase, L.; Pușcaș, C.; Duma, M.; Login, C.C.; et al. Stachys Species: Comparative Evaluation of Phenolic Profile and Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Potential. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1644. [CrossRef]

- Benedec, D.; Oniga, I.; Hanganu, D.; Vlase, A.-M.; Ielciu, I.; Crișan, G.; Fiţ, N.; Niculae, M.; Bab, T.; Pall, E.; et al. Revealing the Phenolic Composition and the Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Antiproliferative Activities of Two Euphrasia sp. Extracts. Plants 2024, 13, 1790. [CrossRef]

- Vlase, L.; Benedec, D.; Hanganu, D.; Damian, G.; Csillag, I.; Sevastre, B.; Mot, A.C.; Silaghi-Dumitrescu, R.; Tilea, I. Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities and Phenolic Profile for Hyssopus officinalis, Ocimum basilicum and Teucrium chamaedrys. Molecules 2014, 19, 5490-5507. [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.; Maestre, A.B.; Hernández-Ruiz, J.; Arnao, M.B. ABTS/TAC Methodology: Main Milestones and Recent Applications. Processes 2023, 11, 185. [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of "antioxidant power": the FRAP assay. Anal. Journal of Biochemistry 1996, 239 (1), 70-76. ISSN 0003-2697. [CrossRef]

- Abeyrathne, E.D.N.S.; Nam, K.; Ahn, D.U. Analytical Methods for Lipid Oxidation and Antioxidant Capacity in Food Systems. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1587. [CrossRef]

- Ghani, A.; Barril, C.; Bedgood, D.R.; Prenzler, P.D. Measurement of antioxidant activity with the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assay. Food Chemistry 2017, 230, 195-207. ISSN 0308-8146. [CrossRef]

- Janero, D.R. Malondialdehyde and thiobarbituric acid-reactivity as diagnostic indices of lipid peroxidation and peroxidative tissue injury. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 1990, 9(6), 515-40. [CrossRef]

- Popescu, L.; Cojocari, D.; Ghendov-Mosanu, A.; Lung, I.; Soran, M.-L.; Opriş, O.; Kacso, I.; Ciorîţă, A.; Balan, G.; Pintea, A.; et al. The Effect of Aromatic Plant Extracts Encapsulated in Alginate on the Bioactivity, Textural Characteristics and Shelf Life of Yogurt. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 893. [CrossRef]

- Macari, A.; Sturza, R.; Lung, I.; Soran, M.-L.; Opriş, O.; Balan, G.; Ghendov-Mosanu, A.; Vodnar, D.C.; Cojocari, D. Antimicrobial Effects of Basil, Summer Savory and Tarragon Lyophilized Extracts in Cold Storage Sausages. Molecules 2021, 26, 6678. [CrossRef]

- M100; Performance Standars for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 29th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2019.

| Samples | Yield (%) | TPC (mg/ g dw GAE ) | TFC (mg/ g dw RE ) |

| Basal leaves | 17.24 | 15.47 ± 0.86 | 7.47 ± 1.32 |

| Cauline leaves | 17.14 | 13.18 ± 0.73 | 5.84 ± 0.66 |

| Stems | 13.12 | 6.62 ± 0.39 | 1.95 ± 0.92 |

| Bracts | 14.96 | 2.56 ± 0.40 | 1.39 ± 0.37 |

| Inflorescenes | 3.88 | 0.94 ± 0.44 | 0.11 ± 0.08 |

| Polyphenolic Compounds | RT ± SD (min) |

[M-H]- exp. (m/z) |

Basal leaves (µg/ml) |

Cauline leaves (µg/ml) |

Stems (µg/ml) |

Bracts (µg/ml) |

Inflorescenes (µg/ml) |

| Gentisic acid | 2.15+ 0.07 | 179 | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | ND |

| Caffeic acid | 5.60+ 0.04 | 173 | 138.944±0.79 | 123.469± 0.654 | 11.031±0.253 | 4.202±1.085 | 0.190+0.216 |

| Myricetin | 21.13 + 0.06 | 179 | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | ND |

| Quercitrin | 23.00 + 0.13 | 447 | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | ND |

| Luteolin-7-O-glucoside | 29.10 + 0.19 | 285 | 74.981±0.184 | 24.411±0.356 | 2.289±0.332 | 1.897±0.036 | 0.673±0.077 |

| Kaempferol | 31.60 + 0.17 | 595 | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Apigenin | 33.10 + 0.15 | 269 | 13.791±0.723 | 23.179±1.73 | 2.201±0.22 | 3.991±0.2 | 4.740±0.24 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 5.62+ 0.05 | 353 | 515.93±8.966 | 485.74±9.097 | 115.07±6.679 | 3.98±0.301 | 12.25±0.488 |

| p-coumaric acid | 8.7+ 0.08 | 163 | 1.397±0.019 | 1.255±0.07 | 0,292±0,07 | 0,419±0,024 | ND |

| Ferulic acid | 12.2 + 0.10 | 193 | 1.495±0.028 | 0.789±0.028 | 0.313±0.04 | 0.749±0.035 | ND |

| Izoquercitrin | 19.60 + 0.10 | 463 | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | ND |

| Samples |

DPPH˙ IC50(µg/mL) |

ABTS˙+ IC50(µg/mL) |

FRAP (μM/gdw) |

NO˙ I % |

LDL oxidation I % |

| Basal leaves | 96.14±0.17 | 29.1±0.37 | 67.7±0.7 | 60.1±0.12 | 61.2±0.40 |

| Cauline leaves | 125.82±0.22 | 32.9±0.23 | 56.97±1.31 | 57.52±0.13 | 60.8±0.38 |

| Stems | 412.89±0.48 | 80.03±1.17 | 33.58±0.39 | 50.27±0.06 | 54.13±0.87 |

| Bracts | 2182.68±0.65 | 1446±1.55 | 22.45±0.32 | 50.18±0.003 | 57.82±0.39 |

| Inflorescences | 6960.92±0.21 | 1011.39±1.07 | N/E | 50.45±0.05 | N/E |

| Trolox | 12.08±0.03 | 2.55±0.08 | - | - | - |

| EDTA | - | - | 99.58±0.01 | - | - |

| Ascorbic acid | - | - | - | 85.7±0.05 | 58.2±0.01 |

| Test Strains | Zone of Inhibition, (mm) | MIC, (mg/mL) | MBC/MFC, (mg/mL) | ||||||||||||||||||

| BL | CL | ST | BC | IF | TC | MC | BL | CL | ST | BC | IF | TC | MC | BL | CL | ST | BC | IF | TC | MC | |

| B. cereus | 10.2 ± 0.20 |

9.3 ± 0.58 |

9.2 ± 0.7 |

8.1 ± 0.10 |

N/E | 21.0 ± 1.00 | N/A | 0.301 ±0.03 |

0.259 ±0.05 |

0.344 ±0.02 |

0.448 ±0.03 |

N/ E |

0.001±0.00 | N/A | 0.301 ±0.03 |

0.592 ±0.06 |

0.793 ±0.01 |

0.879 ±0.06 |

N/E | 0.001±0.00 | N/A |

| C. diphtheriae | 12.4 ± 0.47 |

11.1 ± 0.40 |

6.2± 0.20 | 7.2 ± 0.20 |

N/E | 22.0 ± 0.00 | N/A | 0.301 ±0.03 |

0.592 ±0.06 |

0.793 ±0.01 |

1.649 ±0.03 |

N/ E |

0.005±0.00 | N/A | 1.489 ±0.02 |

1.545 ±0.01 |

3.430 ±0.01 |

N/E | N/E | 0.016±0.00 | N/A |

| E. coli | 8.5 ± 0.30 |

7.3 ± 0.25 |

4.5 ± 0.18 |

5.7 ± 0.25 |

N/E | 18.0 ± 0.57 | N/A | 0.301 ±0,03 |

0.592 ±0.06 |

1.366 ±0.16 |

1.649 ±0.03 |

N/ E |

0.005±0.00 | N/A | 1,489 ±0.02 |

1,545 ±0.01 |

3,430 ±0.01 |

3,430 ±0.01 |

N/E | 0.005±0.00 | N/A |

|

E. faecalis |

9.6 ± 0.32 |

9.2 ± 0.20 |

5.7 ± 0.17 |

6.9 ± 0.10 |

N/E | 22.0 ± 0.00 | N/A | 0.762 ±0.02 | 0.592 ±0.06 |

1.366 ±0.16 |

1.649 ±0,03 |

N/ E |

0.005±0.00 | N/A | 1.489 ±0.02 |

1.545 ±0.01 |

3.430 ±0.01 |

N/E | N/E | 0.008±0.00 | N/A |

| P. aeruginosa | 6.2 ± 0.29 |

5.9 ± 0.20 |

4.1 ± 0.10 |

N/E | N/E | 24.0 ± 1.12 | N/A | 1.489 ±0.02 |

1.545 ±0.01 |

1.366 ±0.16 |

N/E | N/ E |

0.005±0.00 | N/A | 3.505 ±0.01 |

3.642 ±0.04 |

3.430 ±0.01 |

N/E | N/E | 0.012±0.00 | N/A |

| S. aureus | 10.7 ± 0.30 |

10.2 ± 0.29 |

8.6 ± 0.21 |

7.5 ± 0.10 |

N/E | 19.0 ± 1.22 | N/A | 0.301 ±0.03 |

0.592 ±0.06 |

0.793 ±0.01 |

0.448 ±0.03 |

N/ E |

0.001±0.00 | N/A | 0.762 ±0.02 |

1.545 ±0.01 |

3.430 ±0.01 |

1.649 ±0.03 |

N/E | 0.001±0.00 | N/A |

| C. albicans | 8.1 ± 0.10 |

7.7 ± 0.12 |

7.2 ± 0.12 |

6.2 ± 0.25 |

N/E | N/A | 22.0 ± 0.00 | 1.466 ±0.02 |

1.532 ±0.01 |

3.435 ±0.01 |

1.635 ±0.03 |

N/ E |

N/A | 0.012±0.00 |

3.517 ±0.01 |

3.624 ±0.04 |

3.435 ±0.01 |

N/E | N/E | N/A | 0.016±0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).